?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Insecure housing—particularly for low-income groups—constitutes a critical and enduring social problem. While Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) initiatives show promise as a solution to mitigate this issue, research assessing their impact remains limited. This paper makes three contributions to the empirical PSH literature: it develops a novel framework to measure the success of PSH tenancy outcomes; it expands the evidence-base to consider the role of tenancy issues and provider-initiated tenancy-sustainment supports; and it provides new evidence on a single-site PSH initiative in Queensland (Australia)—Brisbane Common Ground (BCG). We use 10 years’ worth of administrative data on all 417 tenancies—both concluded and ongoing—taking place since the onset of BCG in July 2012 and up to November 2022. Our main analyses combine descriptive statistics, event-history analyses, and logistic regression models. Results reveal significant heterogeneity in the probability of experiencing positive PSH tenancies across socio-demographic groups, the intervening role of tenancy issues, and the partially protective role of provider tenancy-sustainment initiatives. The results, however, vary depending on the lens through which PSH tenancy outcomes are viewed. These findings stress the need for targeted PSH strategies that better cater for the complex needs of specific subgroups of tenants.

Introduction

Insecure housing, particularly for low-income groups, constitutes a critical and enduring social problem in developed nations. While homelessness has declined slightly in some OECD countries, there have been remarkable increases in many others (OECD, Citation2021)—a situation often exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Pawson et al., Citation2021). In Australia, where the present study is based, the number of people experiencing homelessness between 2018 and 2022 grew at double the rate of the national population (Pawson et al., Citation2022).

Since the 1990s, Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) has gained momentum as a viable approach to combat homelessness among people with demonstrable housing, health, and social care needs. Broadly, PSH refers to interventions that combine affordable housing assistance and voluntary support services to address the housing needs of people who are homeless (National Alliance to End Homelessness [NAEH], Citation2023). PSH models strive to provide housing that is permanent (as opposed to fixed term); affordable (e.g. through either social stock or subsidized lease arrangements); and of good quality (Rog et al., Citation2014). Further, PSH integrates tenancy services, support services, and case management tailored to each tenant’s support needs (Rog et al., Citation2014). Different varieties of PSH have a long tradition in some countries—such as the US, and have more recently been introduced in others—such as Australia and parts of Europe. In addition, it has been argued that the Housing First approach to PSH has existed for an extended period of time in the UK, although not always explicitly identified by that name (Johnsen & Teixeira, Citation2012).

The growing adoption of PSH has been accompanied by emerging academic scholarship aimed at assessing its functioning and effectiveness. The findings of these studies broadly indicate that the model generally ‘works’. For example, studies conducted largely in the US have shown that PSH can foster housing stability and result in decreased healthcare utilization, improved quality of life, and enhanced community functioning (Aubry et al., Citation2015; Padgett et al., Citation2016; Twis & Petrovich, Citation2023). Despite this growing body of evidence, a number of questions remain unanswered or only partially answered.

In this study, we make three contributions to the available evidence. First, existing studies examining factors that predict successful PSH outcomes have almost exclusively focused on the personal characteristics of individual tenants—for example, their age, gender, ethnicity, substance use, and prior history of homelessness (see e.g. Collins et al., Citation2013; Gabrielian et al., Citation2016; Hsu et al., Citation2021). To our knowledge, this body of work has not examined more proximal factors that may also drive tenancy outcomes. The present study provides novel evidence on two such factors: (i) issues that emerge during tenancies and (ii) provider efforts to redress challenges experienced by tenants. In doing so, our analyses provide useful insights for the development of policies and practices that housing and support providers can engage in to improve tenant experiences and foster tenant retention.

Second, chiefly due to data availability, existing studies have often resorted to analyzing indirect or partial measures of ‘success’ in relation to PSH tenancies. As Tiderington (Citation2021) puts it, ‘studies on exits from homeless services rarely distinguish between types of departure’ (p.9). Similarly, Matheson et al. (Citation2023) note how ‘[o]f the limited literature on exits from housing assistance, researchers have focused primarily on two outcomes: duration of housing assistance and factors associated with exit’ (p.283) and that ‘little in the published literature focuses on positive or negative exits’ (p.284). Indeed, many studies simply equate a tenancy exit with an unsuccessful outcome and tenancy retention with a successful outcome (see e.g. Collins et al., Citation2013; Tsemberis et al., Citation2012; Twis & Petrovich, Citation2023). However, as noted in recent scholarship (see e.g. Byrne & Tsai, Citation2022; Taylor & Johnson, Citation2021; Matheson et al., Citation2023; Petrakos et al., Citation2023), improving our understanding of PSH tenancy outcomes requires careful consideration of the circumstances in which people leave PSH, not just the fact that they leave. For example, Byrne & Tsai (Citation2022) distinguish between ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ exits from supportive housing for veterans. Exits were considered positive when veterans achieved their goals, no longer needed the program, or ceasing being eligible. Conversely, exits were considered negative when veterans were unhappy with their housing, failed to comply with case management, or were evicted. In a similar vein, Matheson et al. (Citation2023) and Petrakos et al. (Citation2023) classified tenancy exits as ‘positive’, ‘neutral’ or ‘negative’. Positive exits were associated with self-sufficiency and included reasons such as moving to non-subsidized rentals or homeownership. In contrast, negative exits were linked to eviction, lease violations, criminal activity, or abandonment of property. In this paper, we build on this emerging literature and develop a framework to better conceptualize and operationalize successful and unsuccessful PSH tenancy outcomes. The proposed framework goes beyond tenancy retention/exit by incorporating information pertaining to the circumstances surrounding tenancies and tenancy exits.

Our empirical analyses are based on administrative data covering the 2012–2022 period and capturing all historical tenancies both concluded and ongoing (n = 417) in Brisbane Common Ground (BCG), an Australian model of single-site PSH based on Housing First principles. These unique data are analyzed using a mixture of descriptive statistics, event-history analyses, and logistic regression models. The results demonstrate that tenancy outcomes are contingent on tenants’ characteristics, with women and people who were not formerly homeless being comparatively more likely to experience successful outcomes. Arrears and behaviour issues during tenancy were important factors leading to negative tenancy outcomes, whereas provider tenancy-sustainment initiatives fostered some positive outcomes. Importantly though, these patterns differed across measures of tenancy success. These findings hold lessons for policy and practice. Among others, they stress the need for targeted PSH strategies that better cater for the complex needs of certain subgroups of tenants and increased provider tenancy-sustainment initiatives.

Factors contributing to Permanent Supportive Housing tenancy outcomes

The majority of empirical studies examining factors associated with PSH tenancy sustainment have focused on the role of individual or personal characteristics. These include common demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and race/ethnicity, as well as prior experiences of homelessness (e.g. Collins et al., Citation2013), physical and mental health issues (including substance use) (e.g. Cusack & Montgomery, Citation2017; Taylor & Johnson, Citation2021), and income sources (e.g. Gabrielian et al., Citation2016). Overall, this literature has established that substance use, psychiatric disorders, and a prior history of homelessness are factors associated with a greater likelihood of exiting a PSH tenancy (Grove et al., Citation2022; Twis & Petrovich, Citation2023). These tenant experiences are argued to negatively affect the sustainability of PSH tenancies through behaviours incompatible with tenancy rules and regulations and the inability to cover rent. However, very few quantitative studies have directly assessed the role of these more proximal or ‘downstream’ issues on tenancy outcomes. Closest to this, two studies have reported that involuntary tenancy exits from PSH can be precipitated by non-payment of rent, anti-social or criminal behaviour, and lack of compliance with tenancy conditions (Bernet et al., Citation2015; Wong et al., Citation2006). These issues, however, are well recognized in qualitative studies exploring the perspectives of PSH tenants, especially the manner in which conflict among residents drives negative tenant experiences (Parsell et al., Citation2015). Better understanding which tenancy issues lead to unsuccessful PSH outcomes constitutes an important endeavour, as this information directly points to specific types of support needed to foster successful tenancies.

In addition, we argue that the PSH literature has not sufficiently empirically assessed the role of provider-initiated tenancy-sustainment efforts. Since PSH attracts individuals with high vulnerability profiles and complex needs, providers often have formal and informal strategies aimed at supporting tenancy retention through service integration, tenant-centred service provision, and specialized professional positions (Biederman et al., Citation2023). In the case of BCG, these strategies take the form of Sustaining Tenancy Plans (STPs). STPs are joint plans involving the housing provider (BCG), a support services provider (Micah Projects) and, optimally, the tenant. For example, a tenant may present with issues related to rental arrears; in response BCG may agree with Micah Projects and the tenant to undergo financial counselling and/or to establish an automatic rent-deduction process. These plans are not sanctioning or legal documents, but rather an agreed list of tangible actions to be pursued towards resolving any anticipated or existing issue that may put a tenancy at risk. Importantly, STPs are put into motion by BCG staff not only when tenants have already exhibited issues jeopardizing their tenancies, but also pro-actively when tenants enter BCG with complex backgrounds and characteristics (e.g. recent and/or long-term experiences of rough sleeping or a history of psychiatric disorders). How provider initiatives, such as STPs, actually influence PSH tenancy outcomes, however, remains an open question. In the empirical component of this study, we offer novel evidence by incorporating them into the analysis.

Rethinking ‘success’ in Permanent Supportive Housing tenancy outcomes

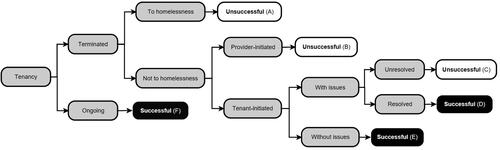

As part of this study, we propose a novel framework to characterize the success of PSH tenancies, moving beyond the straightforward equation of tenancy retention with tenancy success (Collins et al., Citation2013; Tsemberis et al., Citation2012) and combining elements of recent studies in the field (Byrne & Tsai, Citation2022; Petrakos et al., Citation2023). The proposed framework, illustrated in , is outlined within this section. We adhere to understandings of PSH as an initiative aiming to help individuals achieve autonomy, self-sufficiency and independence and prevent future homelessness through the provision of permanent affordable housing and targeted supports (Padgett et al., Citation2016; Rog et al., Citation2014). Given the centrality of ‘permanency’ as a factor underpinning PSH, we align with previous studies in that tenancy retention should always be seen as a successful outcome in the context of PSH. Research shows that a majority of PSH tenants—and, in some initiatives, all tenants—enter PSH from a situation of homelessness (including housing instability); have a history or homelessness; and/or are at risk of becoming homeless (Parsell et al., Citation2015). Even when tenant experiences are not optimal, PSH can objectively be considered an improvement over these counterfactuals. Hence, akin to standard definitions in earlier studies, our framework retains a characterization of tenancy retention as evidencing a successful PSH tenancy outcome.

However, following recent work in this space (Matheson et al., Citation2023; Petrakos et al., Citation2023; Taylor & Johnson, Citation2021), our framework stresses the need to add nuance to the assumption that a tenancy exit constitutes an unsuccessful PSH tenancy outcome. Instead, we posit that evaluating whether a terminated PSH tenancy was successful or not requires careful consideration of the circumstances surrounding the tenancy exit. A critical factor here is the exit destination—that is, where individuals move to after the end of a PSH tenancy. When PSH tenants leave to a situation of homelessness, we argue that PSH did not meet its aims of preventing future episodes of homelessness (Aubry et al., Citation2020). Arguably, these tenants were housed and received allied services for a period of time, and this is indeed a positive reality. Yet the ultimate outcome of individuals leaving into homelessness goes counter to PSH’s commitment to permanently end individuals’ housing insecurity. Therefore, in our framework, any PSH tenancy terminations leading to a situation of homelessness are seen as unsuccessful tenancy outcomes.

Yet, within our framework, not all terminated PSH tenancies where tenants did not exit into homelessness are deemed to be successful (see also Matheson et al., Citation2023; Petrakos et al., Citation2023). Rather, under these circumstances, we posit that it is important to consider tenants’ agency and autonomy in decisions regarding their housing—as reflected by whether tenancy exits are tenant-initiated or provider-initiated. We propose that PSH can be successful not just when it manages to retain tenants, but also when it enables them to move into different housing conditions that better meet their changing needs and aspirations. Indeed, qualitative research with tenants supports the proposition that—also from their viewpoints—sustaining a tenancy is a success. Furthermore, some PSH tenants perceive the permanency of their tenancies as creating the practical conditions for them to eventually aspire to exit PSH and enter homeownership (Parsell & Marston, Citation2016). Specifically, it was the stability of PSH that enabled people to imagine what other housing and life changes were possible (Parsell & Marston, Citation2016). This is consistent with PSH’s aim of supporting individual autonomy, self-sufficiency and independence (Padgett et al., Citation2016). PSH tenants’ life-course circumstances may change, leading to different housing needs. Indeed, although referred to as ‘permanent’, some PSH initiatives in countries such as Canada are deliberately time limited, with the intervention aimed at improving tenants’ skills so that they can eventually access housing in the market (Stadler & Collins, Citation2021). Under our proposed framework, individuals who transfer from PSH onto other suitable housing arrangements will be generally considered as having had successful PSH tenancies. There are, however, exceptions. Qualitative studies engaging the perspectives of PSH tenants have noted that, even when tenants appear to leave PSH out of their own volition, they sometimes do so because of tenancy-related issues and disputes with housing providers. Indeed, in the absence of a formal court order, tenants may be ‘pushed out’ of their housing because of conflict with their landlord and not even perceive their situation as an eviction (Desmond & Shollenberger, Citation2015). For these reasons, we propose that PSH tenancies with tenant-initiated exits should not be characterized as successful tenancies where: (i) there is evidence of tenancy issues, and (ii) these issues remained unresolved at the time of tenancy termination. Rather, we posit that these situations point to PSH’s failure to address the—often complex—needs of tenants and reflect ‘preventable’ exits, as well as failing to elicit genuine tenant autonomy. Therefore, these tenancies are characterized as ‘unsuccessful’ tenancies within our proposed framework.

Permanent supporting housing in Australia and the Common Ground model

Building on housing models in the field of mental health, where people accessed housing on the basis of diagnoses (Bruce et al., Citation2012), Australia started experimenting with broader PSH models as a response to homelessness in the first decade of the 2000s. Initially, PSH was put forward as part of a national agenda to draw on evidence to achieve measurable reductions in homelessness, especially for people sleeping rough (Australian Government, Citation2008). The subsequent implementation of PSH in Australia, including initiatives such as J2SI and Street to Home, borrowed heavily from the Housing First model (Johnson et al., Citation2014). Housing First emerged in the US in the early 1990s from a political alliance of social-justice advocates, housing providers, and social scientists, and represents a turning point in housing policy (Rosenheck, Citation2021). The model challenges assumptions that people with a history of homelessness and mental illness must be ‘housing ready’ before they can be housed (Padgett, et al., Citation2016). That is, Housing First rejects the notion that homeless individuals must address their behavioural, physical, and mental-health issues prior to being allocated housing. Instead, supports for addressing these issues are offered together with housing. The rapid spread of Housing First and various PSH models beyond the US required adaption to local contexts and engendered diversity in program design and delivery (Padgett et al., Citation2016).

In addition to the Housing First approach, with links to Sam Tsemberis, Australian PSH initiatives have been strongly influenced by the Common Ground model (Parsell et al., Citation2014). While the Common Ground model draws on many Housing First principles, it varies from traditional Housing First models by offering single-site housing with services located in the building where tenants live. BCG, the PSH initiative from which we draw our data, constitutes one of the first Australian single-site PSH initiatives, welcoming its first tenants in July 2012 and reaching capacity just five months later. BCG follows a single-site PSH model, with tenants being housed within a building containing 146 apartments near the Brisbane CBD. Consistent with the Housing First tradition, BCG integrates tenancy services with community, social, and health care services, alongside on-site security, and concierge services.

Overall, BCG caters to two groups of tenants: people on low incomes and people who have experienced homelessness, including chronic homelessness and rough sleeping. This approach is intended to create a ‘social mix’ leading to a vibrant, diverse, and interconnected community. At first sight, the two cohorts differ in the reason for their BCG tenancy allocation: one due to homelessness and the other due to an acute need for affordable housing. In practice, however, the cohorts share more similarities than differences in their circumstances and alternatives within the broader housing market. Indeed, both groups comprise individuals who are structurally disadvantaged in the local housing market, which is characterized by extremely long waits for social housing (Parsell, Citation2023) and private-rent increases of 23% for units and 33% for houses between 2020 and 2023 (Pawson et al., Citation2023). Therefore, a rigid and complex housing market means that homelessness and/or housing instability are likely counterfactuals for individuals in both BCG cohorts. This reality supports our identification of PSH retention as a positive outcome, an argument that others have made before us in relation to similar cohorts in other countries (see e.g. Livingstone & Herman, Citation2017; Matheson et al., Citation2023; and Tiderington, Citation2021).

An initial evaluation of BCG documented high rates of tenancy sustainment and general improvements in health and healthcare access after 12 months of tenancy entry. However, no changes in substance use or education, training or labour-market participation were observed. Overall, BCG yielded a cost-offset to government of approximately $13,000 per tenant in the first year of their tenancy (Parsell et al., Citation2017). The success of individual BCG tenancies and how this may differ by tenants’ demographic characteristics and tenancy experiences, as well as provider tenancy-sustainment initiatives, however, remain to be examined. This constitutes a key aim of the present study.

Materials and methods

Dataset

This project received approval by the Ethics Committee at The University of Queensland (2022/HE001420). The analyses make use of administrative data collated and provided by BCG as part of a broader research project. The data contain information on all 417 BCG tenancies since the initiative’s inception in 2012 (the first tenancies began on 12 July 2012) up until 1 November 2022. Across tenancies, the data include information on: (i) the start and end date (if applicable) for each tenancy; (ii) tenants’ socio-demographic characteristics at tenancy entry and pre-tenancy housing circumstances; (iii) tenants’ experiences and challenges during their tenancy; (iv) interventions made by BCG to sustain tenancies; and (v) the exit circumstances of those whose tenancies ended.

Outcome variables

We consider two different outcome variables to characterize tenancy outcomes. The first outcome variable is a simple duration measure that emulates those used in many previous PSH research (see e.g. Lipton et al., Citation2000; Collins et al., Citation2013; Grove et al., Citation2022) and captures tenancy exits. As noted, previous studies often equate any exit from PSH with an unsuccessful tenancy outcome. For individuals who left their tenancies, this simple duration measure counts the number of days elapsed since tenancy entry. For those individuals who had not left their tenancies by the end of the observation period (i.e. 1 November 2022), the measure is set to missing due to right censoring. Since we model these data using event-history analysis (details below), observations falling into the latter scenario are treated as a being censored, with those tenants contributing to the models up to the end of the observation window. Overall, 65.7% of BCG tenants were observed to conclude their tenancies, with the mean tenancy duration (conditional on tenancy exit) being 836 days (median = 612; standard deviation = 742 days; minimum: 39 days; maximum: 3659 days) (). Therefore, only 34.3% of tenants appear to have experienced a positive tenancy outcome using this proxy measure.

Table 1. Sample composition.

The second outcome variable is a novel and more complex measure that builds on recent studies (Byrne & Tsai, Citation2022; Matheson et al., Citation2023; Petrakos et al., Citation2023). It adds granularity by factoring in tenancy circumstances (i.e. the presence of tenancy issues and provider responses to those issues) and exit pathways (i.e. the tenants’ subsequent living arrangements). We argue that this alternative measure better captures the success of tenancies, given PSH’s stated aims discussed before. The following variables were used in the derivation of this outcome variable: (i) whether the tenancy was observed to end (yes, no); (ii) whether the tenant exited to homelessness (yes, no); (iii) whether the tenancy exit was initiated by the tenant (yes, no); and (iv) whether there were unresolved issues at the time of tenancy exit (yes, no).Footnote1 Combining the values of these variables, we identified six mutually exclusive and exhaustive scenarios representing different variations of successful versus unsuccessful tenancy outcomes. These scenarios were then combined into a binary outcome variable. Successful tenancy outcomes were deemed to occur in three scenarios: tenancy sustainment (34.3% of all tenancies); tenant-initiated exits without recorded issues, except for tenants who exited to homelessness (33.3% of all tenancies); and tenant-initiated exits with resolved issues, except for tenants who exited to homelessness (7.2% of all tenancies). Meanwhile, unsuccessful tenancy outcomes were deemed to occur under three scenarios: exits to homelessness (6.7% of all tenancies); provider-initiated exits (not to homelessness) (14.4% of all tenancies); and tenant-initiated exits (not to homelessness) with unresolved issues (4.0% of all tenancies). Using this indicator, 74.8% of tenants appear to have experienced a successful tenancy outcome ().

Considering the overlap between the two outcome variables offers interesting and important insights. Only 40.5% of tenants are defined as having a successful tenancy in both measures at the same time. Of the remaining 59.5%, 25.2% have a successful outcome only in the simple duration measure (exited vs. remained), whereas 34.3% have a successful outcome only in our novel measure incorporating the additional considerations. The modest overlap between these two ways of defining and operationalizing the success of PSH tenancies serves to reinforce our aim of comparing the predictors of successful tenancies across measures.

Analytic strategy

We fit two different sets of models, each adapting to the properties of a given outcome variable. Similar to Taylor and Johnson (Citation2021), these take the form of: (i) event-history models for the simple, duration outcome variable and (ii) logistic regression models for the more nuanced outcome variable that takes into account tenancy circumstances.

Event-history analysis

To analyze the simple duration outcome variable, we begin by estimating Kaplan–Meier survival functions, overall and for tenants with different characteristics (Box-Steffensmeier & Jones, Citation2004). These depict the raw survival rate for each day elapsed since tenancy entry—that is, the proportion of tenants who remain housed in BCG out of the total pool of individuals who started a tenancy. In doing so, Kaplan–Meier survival functions help visualize the pace at which different types of individuals leave their tenancies.

We then fit multivariable event-history models adjusted for a range of explanatory variables. Specifically, we use semi-parametric Cox regression models. These models estimate how multiple factors influence the occurrence of an event and are fit-for-purpose to analyze outcomes with a duration format (Box-Steffensmeier & Jones, Citation2004): they account for the fact that individuals leave their tenancies at different time points and hence stop contributing to estimation, while also allowing for right censoring (in our case, this means failing to observe the end of all tenancies). In practice, these specifications model whether an exit occurs on a given day (yes, no) conditional on individuals having survived up to that time point. Formally, the Cox regression models that we fit take the following form:

(1)

(1)

where subscripts i and t stand for individual and time, respectively; h0(t) represents the baseline hazard function of tenancy termination; X is a vector of explanatory variables; and β is a vector of estimated model coefficients. We express the coefficients as hazard ratios (HRs), which give the expected change in the odds of experiencing the hazard (i.e. tenancy termination) associated with a one-unit increase in the explanatory variables. Therefore, in these models, HRs greater than one denote unsuccessful tenancy outcomes.

Logistic regression

The more nuanced outcome variable incorporating additional information on tenancy circumstances is not a duration variable, but rather a traditional (cross-sectional) binary variable. Therefore, we model this outcome using logistic regression, as follows:

(2)

(2)

Here, Y is a binary outcome where one denotes a successful tenancy outcome and zero denotes an unsuccessful tenancy outcome; α is grand intercept; and X and β are as described in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . We express the results of these models using odds ratios (OR). ORs give the expected change in the odds of the outcome variable taking the value one (i.e. tenants experiencing a successful tenancy outcome) associated with a one-unit increase in the explanatory variables. Therefore, in these models, ORs greater than one indicate successful tenancy outcomes. To aid interpretation of effect magnitude, we also translate the model results into predictive probabilities (marginal effects) and present these visually.

Explanatory variables

Across both sets of models, we use three types of explanatory variables. First, we consider the tenants’ socio-demographic traits at tenancy entry. Specifically, our models include variables capturing tenants’ age group (up to 24 years, 25–49 years, 50 years or older); self-reported gender (man, woman); self-reported ethno-cultural group (Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, non-English-speaking background, neither); provider-recorded pre-tenancy living arrangements (formerly homeless, not formerly homeless); and entry cohort (year 2012, years 2013/2015, years 2016/2017, years 2019/2022). These variables are similar to those deployed in earlier studies in the field (see e.g. Grove et al., Citation2022; Hsu et al., Citation2021; Taylor & Johnson, Citation2021).

Second, we consider provider-recorded instances of three type of tenancy challenges. These included whether tenants experienced issues related to arrears (e.g. being unable to pay rent or to pay rent on time), unit condition (e.g. issues related to cleanliness or damage caused to the unit), or tenant behaviour (e.g. anti-social or aggressive behaviour toward staff and other residents). Each of these variables takes the value one when such issues were reportedly experienced, and the value zero otherwise. The data were provided in this format by BCG and therefore reflect their administrative recording of tenancy experiences. To our knowledge, only two earlier studies to date have been able to partially examine how tenancy issues affected PSH tenancy durations or success (Bernet et al., Citation2015; Wong et al., Citation2006).

Third, we consider provider efforts to address perceived tenancy challenges through STPs. As explained before, STPs represent provider-initiated support interventions to solve problems that may place PSH tenancies at risk. As such, they represent malleable factors that can be altered by policy and practice. Considering the explanatory power of these variables constitutes an important contribution of the present study, as no other research modelling PSH tenancies has considered the role of provider tenancy-sustainment initiatives. In our analyses, we capture the presence of an STP though a binary (yes, no) variable.

For both sets of models, we first fit a base model (Model 1) that includes the base explanatory variables (i.e. socio-demographic factors and circumstances at tenancy entry) to examine their partial associations with the outcome variables. Model 2 adds more proximal variables capturing the experience of different tenancy issues and receipt of an STP, both to ascertain their independent influence on the outcomes and to gauge how their inclusion changes the parameters on the base variables. The latter is informative as to whether experiencing different tenancy issues and tenancy-sustainment initiatives can explain the associations between individuals’ attributes and their tenancy outcomes.

Results

Sample composition

presents descriptive statistics (means) on the analytic variables. A majority of tenants (61.2%) were aged 25–49 years at tenancy entry, whereas 19.9% were 24 years of age or younger and 18.9% were aged 50 years or older. Concerning gender, a slightly greater share of tenants identified as women (51.8%) than men (48.2%). Ethno-cultural diversity amongst BCG tenants was apparent from the data, with 14.9% coming from a Non-English-Speaking Background (NESB) and a further 13.7% identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (A&TSI). Most tenants (53.5%) were homeless at the point of tenancy entry. The most tenancy issues experienced by BCG tenants were behaviour issues (experienced by 27.1% of the sample), followed by unit-condition issues (13.7%) and arrears issues (17.7%). In over a third of tenancies, 36.2% specifically, tenants were supported through an STP.

Predictors of tenancy outcomes: socio-demographic factors

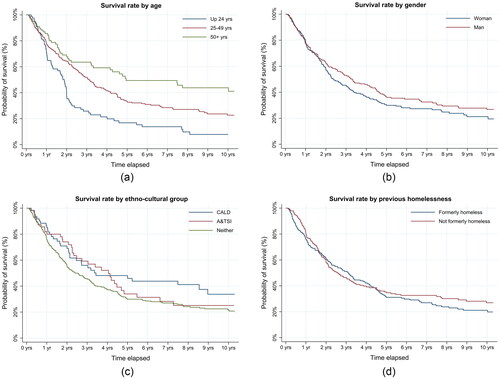

We begin the analysis of the standard duration-based measure of PSH tenancy retention by presenting the Kaplan Meier survival curves for tenants’ socio-demographic traits (see ). These reveal that individuals who are older and identify as men are more like to remain housed in BCG than those who are younger and identify as women. For example, at 5 years from the beginning of the tenancy, the percentage of individuals who remained housed at BCG was 17% for those aged under 24 years, 33% for those aged 25–49 years, and 49% for those aged over 50 years Similarly, at 3 years from the beginning of the tenancy, the percentage of women who maintained their tenancies was 44%, compared to 53% of men. Results are more mixed for ethno-cultural group and previous homelessness, although it appears that ethnic-majority and formerly homeless tenants experience comparatively shorter tenancies overall. The relative contribution of these factors was then assessed simultaneously through event-history models (). In these models, only the age differences were statistically significant, with individuals aged 25–49 years (HR = 0.56, p < 0.05) and 50+ years (HR = 0.38, p < 0.05) being less likely to exit than individuals aged below 25 years. The HRs on all other variables were statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Figure 2. (a) Kaplan Meier survival curve, survival rates by age. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. (b) Kaplan Meier survival curve, survival rates by gender. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. (c) Kaplan Meier survival curve, survival rates by ethno-cultural group. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. (d) Kaplan Meier survival curve, survival rates by previous homelessness. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022.

Table 2. Results from event-history models of tenancy exits, hazard ratios.

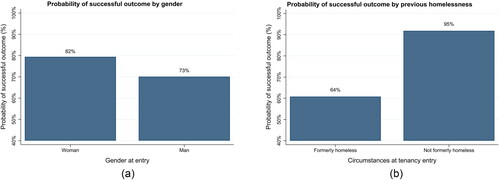

To analyze the factors associated with our proposed measure of PSH tenancy success, we use logistic regression models. Their results are presented in . All else being equal, the odds of a successful outcome were significantly higher for women compared to men (HR = 1.86, p < 0.05) and significantly lower for tenants coming from homelessness compared to those coming from another housing situation (HR = 0.12, p < 0.05). For all other variables, no statistically significant associations were observed. The magnitude of the two statistically significant associations can be appreciated by inspecting the predicted probabilities shown in . Holding the values of the covariates constant, the gender difference in predicted successful outcomes seems modest in magnitude: 82% for women and 73% for men. In contrast, disparities by previous homelessness are vast. Of those entering BCG from homelessness, only 64% experienced a successful tenancy outcome, compared to 95% of those entering from other housing arrangements.

Figure 3. (a) Predicted probabilities from marginal effects, by gender. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. Based on Model 1 in . (b) Predicted probabilities from marginal effects, by previous homelessness. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. Based on Model 1 in .

Table 3. Results from logistic regression models of successful tenancy outcomes, odds ratios.

Overall, we observe clear discrepancies in the factors that predict the standard duration variable in the event-history models (age) and those that predict our proposed measure of tenancy outcomes (gender and prior housing arrangements). This suggests that these measures are indeed capturing different and non-equivalent sides of PSH tenancy processes.

Predictors of tenancy outcomes: tenancy issues and tenancy-sustainment initiatives

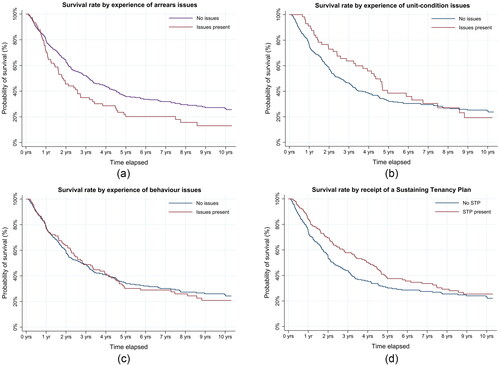

We now turn our attention to two sets of factors likely affecting PSH tenancy outcomes that have received less attention in the literature: issues experienced during tenancies and housing-provider responses to those issues. To illustrate the bivariate associations between these factors and tenancy duration, presents Kaplan Meier survival functions. The graphs suggest that, consistent with expectations, tenants who have arrears issues experience shorter tenancies. At 5 years since tenancy entry, only 20% of those experiencing arrears issues remained housed, compared to 36% of those who had not experienced such issues. Somewhat surprisingly, the survival rates do not seem to vary across tenants with and without experiences of behaviour issues. And even more counterintuitively, those who experienced unit-condition issues seemed less prone to exit compared to those who had not experienced such issues (for example, survival rates 3 years on were 64 and 46%, respectively). It is possible that unit-condition issues tend to emerge at only the late stages of longer tenancies, or that this pattern is an artifact of failing to control for the demographic traits of those tenants who experience and do not experience unit-condition issues—which is addressed in the multivariable models.

Figure 4. (a) Kaplan Meier survival curve, survival rates by experience of arrears issues. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. (b) Kaplan Meier survival curve, survival rates by experience of unit-condition issues. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. (c) Kaplan Meier survival curve, survival rates by experience of behaviour issues. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. (d) Kaplan Meier survival curve, survival rates by receipt of a Sustaining Tenancy Plan. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022.

The results of multivariable event-history analyses are presented in Model 2 within . Focusing on the added variables, we observe that—as expected—experiencing arrears (HR = 1.91, p < 0.05) or behaviour (HR = 1.91, p < 0.05) issues leads to shorter tenancies. Reassuringly, in the presence of the covariates, the counterintuitive result for unit-condition issues no longer stands (p > 0.05). Importantly, receipt of an STP seems to be an important factor preventing early tenancy exits, as indicated by a HR of 0.36 (p < 0.05). Of note, the coefficients on the base variables do not change markedly between Models 1 and 2. This suggests that the associations between the socio-demographic factors and tenancy durations do not occur due to differential experience of tenancy challenges.

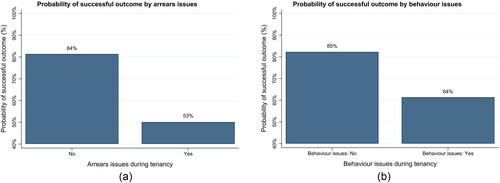

We now turn our attention to the binary measure of tenancy success that incorporates information on tenancy circumstances. The multivariable logistic regression results presented in Model 2 in indicate that arrears (OR = 0.11, p < 0.05) and behaviour (OR = 0.11, p < 0.05) issues act as important deterrents to successful tenancy outcomes, ceteris paribus. The marginal effects presented in point to sizeable effect magnitudes. The probability of a successful tenancy outcome amongst tenants experiencing arrears issues is 53%, compared to 84% for other tenants. For behaviour issues, the analogous figures are 64 and 85%. Meanwhile, neither unit-condition issues nor STPs exert a statistically significant influence on the outcome (p > 0.05). The results for the STP variable contrast with those observed in the event-history analyses, indicating that STPs may be an effective way to lengthen tenancies, yet cannot prevent other types of unsuccessful tenancy outcomes. Interestingly, when comparing the results of Models 1 and 2 in , we observe a reduction and loss of statistical significance in the OR for the ‘woman’ dummy variable (from 1.86, p < 0.05 in Model 1 to 1.49, p > 0.05 in Model 2). This suggests that women’s greater propensity for successful tenancies than men occurs because they experience fewer tenancy challenges or receive greater tenancy-sustainment initiatives.Footnote2

Figure 5. (a) Predicted probabilities from marginal effects, by experience of arrears issues. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. Based on Model 2 in . (b) Predicted probabilities from marginal effects, by experience of behaviour issues. Notes: Administrative data collated by Brisbane Common Ground, July 2012 – November 2022. Based on Model 2 in .

Additional analyses and robustness checks

To confirm the robustness of our results to different methodological decisions and generate additional insights, we implemented a number of sensitivity analyses. In this section, we discuss the results of these analyses.

First, we present summary statistics for a range of alternative indicators of PSH tenancy success. These indicators include the individual factors that were incorporated into our composite measure of PSH tenancy outcomes. Because some earlier studies have focused exclusively on exits (see e.g. Byrne & Tsai, Citation2022; Gabrielian et al., Citation2016), we also present statistics for the subsample of concluded BCG tenancies (n = 274). The results, presented in Supplementary Appendix Table A1, demonstrate substantial variability in success rates depending on which approach is taken. The top panel of Supplementary Table A1 shows results for measures using the full sample of PSH tenancies (n = 417). As previously noted, 34.3% of tenancies qualify as ‘successful’ when success is equated to retention, compared to 74.8% in our more nuanced measure.

The lower panel of Supplementary Table A1 shows results for measures pertaining to the subsample of concluded tenancies. Here, the percentage of successful tenancies is 79.9% when success is defined as exits being tenant-initiated; 88.8% when it is defined as exits not leading to a recorded situation of homelessness; 55.5% when defined as the absence of issues during the tenancy; and 69% when defined as the absence of unresolved issues. Excluding ongoing tenancies from our composite measure sets the success rate at 61.7%. We read this variability in results as underscoring the importance of combining multiple markers of success when devising a holistic measure of PSH outcomes.

Second, we re-estimated our main regression models using a version of our measure of PSH tenancy outcomes that separates ongoing tenancies from positive exits. This recognizes that (i) some perspectives do not consider retention to be an unambiguously positive outcome, and (ii) the factors predicting retention may differ from those predicting positive exits. Because the resulting measure has three discrete categories, we model it using multinomial logistic regression. The results of these models are expressed as relative risk ratios (RRRs), with ‘negative exits’ being used as the baseline category. As shown in Supplementary Table A1, using this measure, 25.2% of the tenancies were classified as negative exits, 40.5% as positive exits, and 34.3% as retention. The multinomial logit regression results are presented in Supplementary Table A2, with some interesting patterns emerging. For example, tenants aged 50+ years are more likely to be retained than to experience negative exits compared to tenants aged 24 years and under (Model 1: RRR = 3.2, p < 0.05), but less likely to experience positive compared to negative exits (Model 2: RRR = 0.26, p < 0.05). Critically, the negative effects of being formerly homeless and experiencing arrears, unit-condition, and behaviour issues are similar when comparing negative to positive exits and negative exits to retention. This pattern of results confirms that such factors are relevant to policy initiatives aimed at either fostering positive PSH exits or increasing retention in PSH.

Third, a preponderance of short tenancies could upward-bias the success rate depicted by any measure of PSH outcomes where ‘retention’ is readily interpreted as ‘success’. To explore whether this constituted an issue in our analyses of BCG, we derived an alternative version of our proposed measure of PSH tenancy outcomes that excluded recent, ongoing tenancies (defined as tenancies shorter than 365 days). Using this measure, the sample size was reduced by 21 tenancies (∼5% of the total), yet the success rate remains comparable, at 73.6% (Supplementary Table A1). Reassuringly, when we re-estimated our main logistic regression models using this new measure (Supplementary Table A3), the results remained remarkably similar to those presented within the main body of the text.

Finally, the factors predicting PSH tenancy outcomes might differ between the two cohorts included within the BCG initiative—that is, formerly homeless and low-income tenants. Indeed, formerly homeless individuals are likely to embody greater vulnerabilities than their low-income neighbours. To explore these propositions, we re-estimated our main models for these two groups separately (Supplementary Table A4). Although some coefficients lose statistical significance due to the smaller cell sizes in these models, the results generally portray a picture of consistency. Most parameters (ORs) point in the same direction and/or have a similar magnitude in the models for the formerly-homeless (n = 223) and low-income (n = 194) cohorts. As an exception, the positive effect of being female on the odds of experiencing a positive PSH tenancy is visible for the low-income group (Model 1: OR = 4.29, p < 0.05) but not for the formerly-homeless group (Model 1: OR = 1.60, p > 0.05). Despite this, none of the equivalent pairs of parameters in the two models were statistically significantly different from each other, as denoted by Wald tests.

Overall, the results of the sensitivity analyses presented in this section add confidence to our approach and method, while also revealing interesting nuances.

Discussion

This paper has proposed a novel framework for understanding the success of PSH tenancy outcomes and argued for the need to better understand the role of tenancy issues and provider tenancy-sustainment initiatives in fostering successful tenancies. Using 10 years of data from BCG, we subsequently examined how socio-demographic factors, tenancy issues, and one type of provider tenancy-sustainment initiatives (STPs) influenced both tenancy retention and tenancy success.

Similar to previous studies, our findings indicate that certain socio-demographic factors play a role in determining the success and longevity of PSH tenancies. Consistent with Twis and Petrovich (Citation2023), we found that entering a PSH tenancy from a state of homelessness severely diminishes the probability of experiencing a successful tenancy outcome, as well as increasing the odds of prompt exits. The estimated effect of being formerly homeless remained after controlling for the experience of tenancy issues and engagement in provider tenancy-sustainment initiatives. This suggests that the reasons why formerly homeless individuals experience negative tenancy outcomes lay elsewhere. Putative mechanisms proposed in other research include ongoing substance use, low levels of engagement in meaningful activity, and low levels of community integration (Marshall et al., Citation2020; Raphael-Greenfield & Gutman, Citation2015; Somers et al., Citation2015). We also observed gender differences in the probability of PSH tenancy success, although not in the timing of exits. Specifically, consistent with the findings of Grove and colleagues (Citation2022), women were more likely than men to experience successful PSH tenancies. This pattern, however, was ‘explained away’ by the inclusion of variables capturing tenancy issues, indicating that women’s tenancies are comparatively more successful due to experiencing fewer tenancy-related issues. Finally, younger PSH tenants (<25 years) exhibited faster, but not less successful, exits. This finding is consistent with earlier studies noting that older age is often associated with longer tenancies (Lipton et al., Citation2000; Grove et al., Citation2022). It is possible that younger tenants have more housing options outside of PSH (e.g. moving with family), or experience fewer barriers to attaining secure housing (e.g. fewer health issues and greater employment chances).

Very little research has considered the role of more proximal factors—including tenancy issues—in influencing the success of PSH tenancy outcomes, which constitutes one of the contributions of this study. We were able to identify the independent contributions of arrears, unit-condition, and behaviour issues. Of these, only arrears and behaviour issues seemed to make a difference, both leading to shorter and less-often successful PSH tenancies. These results are consistent with the findings of Wong et al. (Citation2006), as well as the broader literature on tenancy sustainment, which has identified rent arrears, nuisance, and improper use of housing as primary drivers of eviction (Holl et al., Citation2015). Therefore, the presence—or anticipated presence—of these issues constitutes an important avenue for potential intervention. The results on arrears issues are consistent with one of the premises of the ‘Pathways to Housing’ Housing First approach, whereby the housing provider accesses the state housing subsidy directly, thus negating any potential for a tenant to fall into arrears (Padgett et al., Citation2016). The results on behaviour issues may reflect the independent contributions of mental-health issues and psychiatric disorders identified in previous studies (Grove et al., Citation2022). This finding thus points to the need to increase the supports offered to PSH tenants to adapt their behaviours to align with tenancy rules and regulations—including mental-health treatment and behavioural therapy. In this regard, our study also innovated by empirically assessing how STPs—provider initiatives aimed at resolving manifested or anticipated tenancy issues—made a difference to the length and success of PSH tenancies.

Our results offered mixed evidence about the impact of STPs: while these unambiguously led to longer tenancies, they did not seem to be statistically significantly associated with the likelihood of successful tenancies. On the one hand, this finding can be taken in a positive light, as longer tenancies mean less time for some PHS tenants in a situation of homelessness, including rough sleeping. On the other hand, this finding also points to a failure for PSH to meet its fundamental aim of ending the cycle of housing insecurity. Overall, the mixed results give pause for considering how tenancy-sustainment tools can be made more efficacious. There are different options to consider. A possible avenue for exploration is the involvement of tenant-consumer representatives in the revision and improvement of tenancy-sustainment strategies, such that tenants are afforded greater opportunity to determine the nature of the support they receive. More paternalistic approaches to tenancy support, where some tenant autonomy is (temporarily) removed and interventionist support is mandatory could be tested (Watts et al., Citation2018).

To compare the performance of our proposed framework to measure PSH tenancy success, all analyses were conducted twice, comparing the results using this new outcome measure to a simple measure equating tenancy retention to tenancy success. While just over a third of tenancies (34%) would be considered successful using a simple retention-based measure, as many as three-quarters (75%) were considered successful using our proposed framework. Indeed, the overlap between these two measures was modest (41% of cases). Furthermore, some factors were predictive of tenancy retention but not tenancy success (e.g. age and STPs), or predicted tenancy success but not tenancy retention (e.g. gender). Altogether, these results suggest that our measure of tenancy success performs differently to standard measures of tenancy retention. When considering a wider range of possible operationalizations of tenancy success in the additional analyses, a large degree of variability was also apparent. To the extent that our proposed framework successfully captures aspects beyond retention that contribute to the success—or lack thereof—of PSH tenancies, we conclude that tenancy retention is but an imperfect proxy of tenancy success.

As explained before, our measure of PSH tenancy success incorporates greater nuance than previous operationalizations of this concept. It is nevertheless worth noting that, deliberately, this nuance was exclusively achieved by distinguishing ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ tenancy exits based on their circumstances. Recognizing the centrality of ‘permanency’ in PSH and anticipating a counterfactual of homelessness—broadly defined—for PSH tenants in Australia, we viewed PSH tenancy retention as being always indicative of a successful outcome. This is consistent with both the stated aims of the BCG initiative and the measures used in earlier PSH studies. As Leickly and Townley (Citation2021, p.1788) argue, long-term housing retention is ‘deeply important for all people and enables a resident to develop place attachment and a sense of community’. However, future research may explore whether there is value in re-thinking this assumption. For example, Moving On initiatives (MOI) in the US (Tiderington, Citation2021) underscore the importance of enhancing tenants’ capabilities to eventually ‘climb up the housing ladder’, which would in turn lead to reducing the significant gap in demand for and supply of PSH placements. Notwithstanding, this approach of ‘fixing’ tenants and encouraging them to leave has been challenged for its ‘paternalistic assumptions’, which are at odds with the ‘self-determination’ and ‘housing as a right’ elements of the model (Lofstrand & Juhila, Citation2012). Indeed, evaluative studies focused on Moving On programmes identify ‘after-care service provision’ and ‘financial assistance’ as the greatest challenges facing former PSH tenants post-exit (Tiderington et al., Citation2022). As noted earlier, the dynamics of the Australian and Brisbane housing markets pose significant barriers for BCG tenants to achieve affordable housing in either the social or private sectors (Parsell, Citation2023; Pawson et al., Citation2023). Tenants may wish to exit PSH, but in practice they have few viable and affordable alternatives (Anglicare Australia, Citation2023).

Despite the contributions and novel findings offered by this study, there are data-driven limitations that should be borne in mind when interpreting the results. These limitations point to plausible avenues for future research. The administrative BCG data on which our analyses were based was comparatively large, long running, and incorporated relevant information often missing from other studies (e.g. information on tenancy issues and provider responses). However, it also lacked data on important domains (e.g. tenants’ health or substance use). If these missing factors are correlated with—and causally posterior to—those included in the models (e.g. prior history of homelessness or behaviour issues during the tenancy), it is possible that the estimated coefficients on the latter could change. Our inability to account for some missing factors would nevertheless not affect the overall success rates observed for PSH tenancies. In addition, the BCG dataset did not contain detailed information on the timing of events (e.g. the onset of tenancy issues or the development of STPs). Therefore, it was not possible for us to determine whether issues emerged early or late into a tenancy, or whether such issues were addressed in a timely manner. These are important aspects that would help contextualize the experiences and outcomes of BCG tenants, and which could be the focus of future research. Further, the administrative nature of the data means that certain variables (e.g. the experience of tenancy issues) were derived from the perspectives of housing providers. Data collected from PSH tenants would offer an additional and important perspective and may not necessarily coincide with the provider records at hand. Two recommendations thus stem from these data-driven limitations: (i) tenancy providers wishing to have their initiatives robustly evaluated through empirical evidence are encouraged to collect data that include information on these aspects; and (ii) future studies should aim to replicate our analyses using a wider set of variables capturing tenants’ circumstances (including the timing of events) and tenant-reported information on tenancy issues. Finally, it is important to remember that BCG is an example of a single-site PSH programme. Whether or not our findings extend to scattered-site PSH programmes remains an open question—one that should be addressed in future research

Despite these limitations, our findings hold important lessons for policy development and future research practice. Conceptually, our study draws attention to the importance of incorporating tenancy circumstances into theoretical models of PSH tenancy success. Future empirical studies may wish to adopt our proposed framework to operationalize PSH tenancy outcomes, moving away from measures that offer a partial view of success. Refined versions of the framework may be possible, and revisiting key findings in the PSH literature using these may yield new insights.

Concerning the development of interventions aimed at fostering positive PSH tenancy outcomes, our results stress the need to consider heterogeneity in tenant characteristics. Tenants who identify as male, for example, may require additional supports to achieve positive outcomes, including help dealing with issues that emerge during a tenancy. In this regard, our findings identify arrears and behaviour issues as important barriers to tenancy retention and success, overall, pointing to areas where supports to tenants should be enhanced. While STPs showed promise in lengthening tenancies, in and of themselves, they seemed insufficient to foster successful outcomes for those leaving PSH. Research aimed at identifying ways to enhance provider tenancy-sustainment interventions to better support tenants to achieve positive transitions out of PSH is urgently required.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (474.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of Common Ground Queensland towards the collection of the administrative data used in this study and their support and the support of Micah Projects in explaining their content and properties.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Francisco Perales

Francisco (Paco) Perales is an Adjunct Associate Professor of Sociology at The University of Queensland. His research uses longitudinal and life-course approaches and quantitative methods to enhance our understanding of social stratification in contemporary societies. Paco’s recent work has concentrated on identifying the drivers of socio-economic inequalities by socio-economic background, gender, and sexual orientation within Australian society. His work has recently been published in outlets such as Demography, Social Forces, Journal of Marriage and Family, Population and Development Review and Social Science & Medicine.

Cameron Parsell

Cameron Parsell is a Professor of Social Science at The University of Queensland. His work examines multiple forms of exclusion and social harms. Cameron’s research focuses on the nature and experience of poverty, homelessness, and domestic and family violence. He is interested in understanding what societies do to respond to these problems, and what societies ought to do differently to address them. His recent work has been published in outlets such as Social Problems, Housing Studies, American Journal of Sociology, and The Sociological Review. Twitter: @cameronparsell

Christine Ablaza

Christine Ablaza is a Research Fellow at The University of Queensland. Her research leverages advanced quantitative methods to understand and address the causes and consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage, particularly in relation to labour markets, housing, and the intersection of these two spaces. She has also worked extensively with international organisations, government, and not-for-profit organisations to formulate policies and implement changes to support the most vulnerable individuals.

Ella Kuskoff

Ella Kuskoff is a Research Fellow at The University of Queensland. Her research focuses on qualitative analyses of inequality and disadvantage. In particular, she is interested in social and policy responses to inequality and disadvantage, and how they may be changed to more effectively address social issues. Her particular areas of interest include domestic violence, gender, and homelessness. Ella’s recent work has been published in journals such as Sociology, Violence Against Women, and Social Policy and Society.

Stefanie Plage

Stefanie Plage is a Research Fellow at the Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course at the School of Social Science, UQ. Her expertise is in qualitative research methods, including the use of participant produced photography. She employs these methods to contribute to the sociology of emotions, and the sociology of health and illness. She completed her PhD at the Centre for Social Research in Health at The University of New South Wales. Currently, her research seeks to understand and improve the interactions of people experiencing social disadvantage with the social and health care systems. Twitter: @SPQueensland.

Rose Stambe

Rose-Marie Stambe is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Queensland and specialises in qualitative research methods, particularly ethnography. Her research focuses on how policy, institutional practices, and systems influence the experiences of marginalised individuals and the potential for transformative change. Rose examines issues such as unemployment, homelessness, charity provision, and just transitions. Through her work, she aims to understand the intricate connections between these factors and the lived realities of marginalised populations. Her research has been published in British Journal of Social Work, Social Policy & Society and Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Twitter: @RStambe.

Notes

1 This information was collated from BCG’s administrative records. Exiting to homelessness is defined as tenants being recorded as experiencing the following living arrangements after tenancy exit: ‘homelessness’, ‘caravan park’, ‘boarding house’, ‘private boarding house’ and ‘crisis accommodation’. Living arrangements not classified as homelessness included, amongst others, ‘social housing’, ‘private housing’, ‘supported accommodation’, ‘institutional care’ and ‘living with family’. Tenant-initiated exits were identified in the data as those preceded by tenants declaring their intention to leave (e.g., through a ‘F13 - Notice of Intention to Leave’ form). All other exits were considered to be provider-initiated tenancies (e.g., those involving the provider requiring the tenant to leave through a ‘F12 - Notice to Leave’ form). To ascertain whether a tenant was experiencing unresolved issues at the time of exit, we combined information on whether the tenant experienced arrears, unit-condition, or behaviour issues over the course of the tenancy (see ‘Explanatory variables’ section) and whether a flag for ‘issues resolved’ existed within the administrative records.

2 Separate analyses introducing the variables in Model 2 one at a time further suggest that all three types of issues contribute to reducing the size and/or significance of the coefficient on the ‘Woman’ variable.

References

- Anglicare Australia. (2023) Rental affordability snapshot, National Report 2023, Ainslie, ACT.

- Aubry, T., Tsemberis, S., Adair, C. E., Veldhuizen, S., Streiner, D., Latimer, E., Sareen, J., Patterson, M., McGarvey, K., Kopp, B., Hume, C. & Goering, P. (2015) One-year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of housing first with ACT in five Canadian cities, Psychiatric Services, 66, pp. 463–469.

- Aubry, T., Bloch, G., Brcic, V., Saad, A., Magwood, O., Abdalla, T., Alkhateeb, Q., Xie, E., Mathew, C., Hannigan, T., Costello, C., Thavorn, K., Stergiopoulos, V., Tugwell, P. & Pottie, K. (2020) Effectiveness of permanent supportive housing and income assistance interventions for homeless individuals in high-income countries: A systematic review, The Lancet-Public Health, 5, pp. e342–e360.

- Australian Government (2008) The Road Home: A National Approach to Reducing Homelessness (Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs).

- Bernet, A., Warren, C. & Adams, S. (2015) Using a community-based participatory research approach to evaluate resident predictors of involuntary exit from permanent supportive housing, Evaluation and Program Planning, 49, pp. 63–69.

- Biederman, D., Silberberg, M. & Carmody, E. (2023) Promising practices for providing effective tenancy support services: A qualitative case study situated in the southeastern United States, Housing Studies, pp. 1–20.

- Box-Steffensmeier, J. M. & Jones, B. S. (2004) Event History Modeling: A Guide for Social Scientists (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Bruce, J., McDermott, S., Ramia, I., Buller, J. & Fisher, K. (2012) Evaluation of the Housing and Accommodation Support Initiative (HASI) (Sydney, New South Wales: University of New South Wales).

- Byrne, T. & Tsai, J. (2022) Actuarial prediction versus clinical prediction of exits from a national supported housing program, The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 92, pp. 217–223.

- Collins, S. E., Malone, D. K. & Clifasefi, S. L. (2013) Housing retention in single-site housing first for chronically homeless individuals with severe alcohol problems, American Journal of Public Health, 103(Suppl 2), pp. S269–S274.

- Cusack, M. & Montgomery, A. E. (2017) The role of eviction in veterans’ homelessness recidivism, Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 26, pp. 58–64.

- Desmond, M. & Shollenberger, T. (2015) Forced displacement from rental housing: Prevalence and neighborhood consequences, Demography, 52, pp. 1751–1772.

- Gabrielian, S., Burns, A. V., Nanda, N., Hellemann, G., Kane, V. & Young, A. S. (2016) Factors associated with premature exits from supported housing, Psychiatric Services, 67, pp. 86–93.

- Grove, L. R., Berkowitz, S. A., Cuddeback, G., Pink, G. H., Stearns, S. C. & Domino, M. E. (2022) Permanent supportive housing tenure among a heterogeneous population of adults with disabilities, Population Health Management, 25, pp. 227–234.

- Holl, M., van den Dries, L. & Wolf, J. (2015) Interventions to prevent tenant evictions: A systematic review, Health & Social Care in the Community, 24, pp. 532–546.

- Hsu, H. T., Hill, C., Holguin, M., Petry, L., McElfresh, D., Vayanos, P., Morton, M. & Rice, E. (2021) Correlates of housing sustainability among youth placed into permanent supportive housing and rapid re-housing: A survival analysis, The Journal of Adolescent Health, 69, pp. 629–635.

- Johnsen, S. & Teixeira, L. (2012) ‘Doing it already?’: Stakeholder perceptions of housing first in the UK, International Journal of Housing Policy, 12, pp. 183–203.

- Johnson, G., Kuehnle, D., Parkinson, S., Sesa, S. & Tseng, Y. (2014) Resolving Long-Term Homelessness: A Randomised Controlled Trial Examining the 36 Month Costs, Benefits and Social Outcomes from the Journey to Social Inclusion Pilot Program St Kilda (Victoria: Sacred Heart Mission).

- Leickly, E. & Townley, G. (2021) Exploring factors related to supportive housing tenure and stability for people with serious mental illness, Journal of Community Psychology, 49, pp. 1787–1805.

- Lipton, F. R., Siegel, C., Hannigan, A., Samuels, J. & Baker, S. (2000) Tenure in supportive housing for homeless persons with severe mental illness, Psychiatric Services, 51, pp. 479–486.

- Livingstone, K. R. & Herman, D. B. (2017) Moving on from permanent supportive housing: Facilitating factors and barriers among people with histories of homelessness, Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 98, pp. 103–111.

- Lofstrand, C. & Juhila, K. (2012) The discourse of consumer choice in the pathways housing first model, European Journal of Homelessness, 6, pp. 47–68.

- Marshall, C. A., Keogh-Lim, D., Koop, M., Barbic, S. & Gewurtz, R. (2020) Meaningful activity and boredom in the transition from homelessness: Two narratives, Revue Canadienne D’ergotherapie [Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy], 87, pp. 253–264.

- Matheson, A., Colombara, D., Pennucci, A., Shannon, T., Chan, A., Suter, M. & Laurent, A. (2023) Seeing the big picture with multisector data: Factors associated with exiting from federal housing assistance by exit type, Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 25, pp. 281–307.

- National Alliance to End Homelessness [NAEH]. (2023) Permanent Supportive Housing. Available at https://endhomelessness.org/ending-homelessness/solutions/permanent-supportive-housing/ (accessed 13 June 2023).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2021) HC3-1 homeless population. Available at https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC3-1-Homeless-population.pdf (accessed 7 May 2023).

- Padgett, D. K., Henwood, B. F. & Tsemberis, S. J. (2016) Housing First: Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Parsell, C. (2023) Homelessness: A Critical Introduction (Cambridge: Polity Press).

- Parsell, C., Fitzpatrick, S. & Busch-Geertsema, V. (2014) Common ground in Australia: An object lesson in evidence hierarchies and policy transfer, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 69–87.

- Parsell, C., Petersen, M. & Moutou, O. (2015) Single-site supportive housing: Tenant perspectives, Housing Studies, 30, pp. 1189–1209.

- Parsell, C. & Marston, G. (2016) Supportive housing: Justified paternalism?, Housing, Theory and Society, 33, pp. 195–216.

- Parsell, C., Petersen, M. & Culhane, D. (2017) Cost offsets of supportive housing: Evidence for social work, The British Journal of Social Work, 47, pp. 1534–1553.

- Pawson, H., Martin, C., Thompson, S. & Aminpour, F. (2021) COVID-19: Rental Housing and Homelessness Policy Impacts Report No. 12 (Sydney, New South Wales: ACOSS/UNSW Poverty and Inequality Partnership).

- Pawson, H., Clarke, A., Parsell, C. & Hartley, C. (2022) Australian Homelessness Monitor 2022 (Melbourne: Launch Housing).

- Pawson, H., Clarke, A., Moore, J., van den Nouwelant, R. & Ng, M. (2023) A Blueprint to Tackle Queensland’s Housing Crisis (Sydney, New South Wales: UNSW).

- Petrakos, N., Liu, Z., Hu, H., Keating, T., Colombara, D., Laurent, A., Chan, A., Pennucci, A. & Matheson, A. (2023) Associations between exit type from federal housing assistance and subsequent homelessness, Housing Policy Debate, pp. 1–19.

- Raphael-Greenfield, E. I. & Gutman, S. A. (2015) Understanding the lived experience of formerly homeless adults as they transition to supportive housing, Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 31, pp. 35–49.

- Rog, D. J., Marshall, T., Dougherty, R. H., George, P., Daniels, A. S., Ghose, S. S. & Delphin-Rittmon, M. E. (2014) Permanent supportive housing: Assessing the evidence, Psychiatric Services, 65, pp. 287–294.

- Rosenheck, R. (2021) Medicalizing homelessness: Mistaken identity, adaptation to conservative times, or revival of social medicine, Medical Care, 59, pp. S106–S109.

- Somers, J. M., Moniruzzaman, A. & Palepu, A. (2015) Changes in daily substance use among people experiencing homelessness and mental illness: 24-Month out-comes following randomization to housing first or usual care, Addiction 110, pp. 1605–1614.

- Stadler, S. & Collins, D. (2021) Assessing housing first programs from a right to housing perspective, Housing Studies, 38, pp. 1719–1739.

- Taylor, S. & Johnson, G. (2021) Examining tenancy duration and exit patterns in a single-site, mixed-tenure permanent supportive housing setting, Housing and Society, 50, pp. 182–205.

- Tiderington, E. (2021) “I achieved being an adult”: A qualitative exploration of voluntary transitions from permanent supportive housing, Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 48, pp. 9–22.

- Tiderington, E., Goodwin, J. M., Reyes, L. & Herman, D. (2022) Services needed and received when moving on from permanent supportive housing, Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 31, pp. 45–54.

- Tsemberis, S., Kent, D. & Respress, C. (2012) Housing stability and recovery among chronically homeless persons with co-occuring disorders in Washington, DC, American Journal of Public Health, 102, pp. 13–16.

- Twis, M. & Petrovich, J. C. (2023) Race and retention in permanent supportive housing: A secondary analysis of housing outcomes, Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 33, pp. 80–93.

- Watts, B., Fitzpatrick, S. & Johnsen, S. (2018) Controlling homeless people: Power, interventionalism, and legitimacy, Journal of Social Policy, 47, pp. 235–252.

- Wong, Y. L. I., Hadley, T. R., Culhane, D. P., Poulin, S. R., Davis, M. R., Cirksey, B. A. & Brown, J. L. (2006) Predicting Staying in or Leaving Permanent Supportive Housing that Serves Homeless People with Serious Mental Illness (Final Report) (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania).