ABSTRACT

This article examines how politicians’ perceptions of media coverage are influenced by their emergence as winners or losers of political battles. Based on a survey of 3,378 Norwegian councillors regarding municipal mergers, we found that although all councillors tended to perceive their opponents’ perspectives on the merger as dominating the public debate, this tendency was significantly stronger among those who had lost council votes regarding mergers. In contrast, the winners saw the debate as more inclusive and comprehensive. We discuss whether these tendencies are expressions of attribution biases that allow politicians to maintain their original beliefs.

Introduction

Research has repeatedly shown that people tend to believe that the media favours opponents’ views over their own – a phenomenon known as hostile media bias (Coe et al. Citation2008; A. C. Gunther et al. Citation2001; Vallone, Lee Ross, and Lepper Citation1985). For example, in the context of municipal mergers, those who view mergers primarily as an economic issue generally assume that the media downplays the importance of the economy and emphasises other aspects of mergers, such as local identities or jobs.

Hostile media bias is generally considered a situational response and tends to be more pronounced among partisans and individuals who are strongly committed to an issue. Furthermore, it is amplified when media coverage is believed to have a broad audience (Feldman Citation2017; A. C. Gunther and Liebhart Citation2006; A. Gunther, Nicole Miller, and Liebhart Citation2009; Perloff Citation2015). In this study, we aimed to investigate hostile media bias by exploring the effects of being on the winning or losing side of a political conflict.

Different activations of hostile media bias can influence the way public debate is perceived. For example, the belief that a particular issue is poorly represented can trigger feelings of marginalisation and alienation among debaters and their supporters and persistent differences in winners’ and losers’ assessments of debates may challenge general perceptions of the fairness and inclusivity of political debates. Therefore, in this study, we explored the uncharted territory of the differential activation of political winners’ and losers’ perceptions of hostile media bias. Our analysis focused on politicians, a group of people who are considered particularly susceptible to the hostile media effect due to their partisan orientations, their strong commitments to certain issues, and the importance they attach to the role of the media in shaping public opinion. To investigate the activation of hostile media bias among political winners and losers, we analysed the problem representations perceived by local councillors in the debate about the municipal merger reform in Norway. Local representatives voted on this nationally initiated reform in 2017, and it came into force in 2020. Throughout this period, the proposed reform was extensively covered by both the local and national media (Folkestad et al. Citation2019). Since most local politicians adopted strong positions in favour of or against the merger of their municipalities, the reform process produced clear winners and losers. We examined the differences in politicians’ views on mergers and their perceptions of the media focus by analysing variations in problem representation. Problem representation is understood here as the representation of a central issue in a merger debate. First, we identified the problem representations of the mergers through in-depth interviews with a sample of municipality officials. Then, using a nationwide survey distributed to all municipal councillors in Norway, we analysed how widespread the different problem representations were and how they were perceived in local public debates. We found that both winners and losers (particularly losers) tended to perceive their opponents’ problem representations as dominant. We also found that the winners, rather than the losers, perceived all problem representations to be more comprehensively covered. Herein, we discuss whether hostile media bias and the tendency to perceive media coverage as comprehensive are situational responses that allow politicians to maintain their original beliefs and worldviews.

Problem representation and hostile media bias among winners and losers

Political actors give political issues a certain form through the way they talk about them. Bacchi (Citation2009) called this shaping ‘problem representation’, i.e., statements about an issue that convey a certain understanding of that issue. To make room for particular political solutions, competing political elites often emphasise different problem representations of the same issue. Problem representations typically highlight some aspects of an issue while excluding others, and these inclusions and exclusions encourage people to think about issues in certain ways (Borah Citation2011, 248; Dennis and Druckman Citation2007, 106; Shah et al. Citation2002, 343; Slothuus Citation2008, 3). Problem representations thus encourage specific definitions and interpretations of political issues, encouraging people to form certain opinions about those issues (Dennis and Druckman Citation2007, 106; A. C. Gunther and Schmitt Citation2004). For example, the issue of municipal mergers can be presented as concerning local identity, the quality of public services, or the economy, among other things. Each problem representation delineates a set of relevant solutions and renders other solutions irrelevant. If a lack of skilled labour or the inefficiency of small-scale public services is presented as a problem, merging with a neighbouring municipality may seem like a good idea. If local identity is pictured as being under threat, it may seem more sensible to remain separate and unmerged. Therefore, different representations of a problem compete for priority and the resulting opportunity to define policy measures.

To determine the extent of perceived media bias, we measured the discrepancy between politicians’ individual problem representations and the dominant problem representations they believed prevailed in public debate. Individual problem representation refers to the aspects of an issue that an individual citizen – or, in our case, a councillor – considers to be particularly important. In contrast, dominant problem representation refers to the aspect of an issue that the same person perceives as dominant in the wider public debate.

Differences in perceptions of media content have been attributed, among other things, to hostile media bias (or hostile media phenomenon/effect/perception). This refers to individuals’ tendency to perceive media coverage as biased against their own positions and favouring their opponents’ (Feldman Citation2017; Perloff Citation2015; Vallone, Lee Ross, and Lepper Citation1985), prompting both sides of a political issue to interpret the same media item as negatively slanted against them. Hostile media bias has been shown to be more pronounced among partisans and those deeply engaged with a particular issue (Perloff Citation2015), and it tends to be more pronounced in highly politicised conflicts with conspicuously different factions (Perloff Citation2017). Furthermore, whether and how hostile media bias is activated depends on the audience that people have in mind when evaluating the impact of information. When people believe a media message is broadcast to – and can influence – a wide audience, the message is interpreted as more slanted towards their opponents’ views than if the media message is believed to have a limited reach. The tendency to assume that others are more influenced by media messages than oneself makes people view widely disseminated messages in a more critical light (A. Gunther, Nicole Miller, and Liebhart Citation2009; A. C. Gunther and Schmitt Citation2004; Perloff Citation2015), and this is especially true when the attitudes of other citizens are important to them (Hansen and Kim Citation2011; Matthes Citation2013). Hostile media bias is therefore likely to be activated when people care about the public being affected by a news story and are invested in the topic under discussion. Consequently, partisans or people whose social identities are affected by a debate are particularly susceptible to interpreting media messages as hostile (Feldman Citation2011; Hansen and Kim Citation2011; Hartmann and Tanis Citation2013; Perloff Citation2015). These tendencies make politicians likely targets of hostile media bias. We therefore expected all councillors to perceive the media as favouring their opponents’ problem representations over their own and formulated our first hypothesis as follows:

H1:

Elected representatives perceive their opponents’ problem representations as dominant.

Political debates followed by a vote inevitably result in winners and losers. Assuming that hostile media bias is a situational bias, activated differently depending on the circumstances, it is plausible that being either a winner or a loser may influence its manifestation. Attribution bias can guide our expectations about how hostile media bias will manifest differently in the winners and losers of a political battle. Attribution bias implies that negative events are more often attributed to the influence of external agents than to positive and neutral events (Morewedge Citation2009, 536). The benefit of attributing negative events, such as lost votes, to an external agent is that losers can explain their losses without compromising their beliefs or the validity of their arguments. For example, if politicians wanting to merge with a neighbouring municipality lose a referendum, they can argue that people have been misled by the media. Attributing their loss to external factors, such as hostile media, allows losers to posit explanations that mitigate self-blame and help maintain their self-esteem (Taylor and Brown Citation1988). Attribution theory further predicts that the winners of a political battle cannot enhance their self-esteem if they attribute their victory to external factors. Instead, their self-esteem increases if they attribute their success to their own actions. Thus, while a loss is likely to be attributed to external factors, a victory is likely to be attributed to the actions of the victor (Esaiasson, Arnesen, and Werner Citation2023). Politicians who win council elections regarding a merger or gain popular support through a referendum are unlikely to attribute their victories to favourable media coverage, but rather to the inherent ‘truthfulness’ of their cause, the strength of their arguments, or their debating skills. In line with attribution theory, we expected hostile media bias to be more prevalent among groups that wished to blame their losses on an external actor; that is, we expected those councillors who lost the merger elections to be more inclined to attribute their losses to hostile or distorted media coverage than those who won. More specifically, we expected losers to have a strong tendency to perceive their opponents’ problem representations as dominant. Therefore, we formulated our second hypothesis as follows:

H2:

The tendency to perceive opponents’ problem representations as dominant is greater for losers than for winners.

To test these hypotheses, we compared elected municipal councillors’ individual and dominant problem representations regarding municipal mergers in Norway. If politicians perceived their opponents’ problem representations as more extensively covered than their own, this would indicate the activation of hostile media bias. Before discussing how we measured problem representation, we provide a brief overview of the recent Norwegian municipal mergers and reform.

Institutional context: Norwegian merger reform as a case study

Between 2014 and 2017, local councils in Norway had to decide on the future of their municipalities. The national government initiated a semi-voluntary merger reform, instructing all municipalities to examine the possibility of merging with one or more neighbouring municipalities and to vote on whether they wanted to merge. The stated aim of the reform was to create larger and stronger municipalities that could provide ‘better welfare services, more sustainable local development and more autonomous local government’ (Regjeringen Citation2016). The merging process involved three steps. In the first step, citizens were consulted. When adjusting their territorial boundaries, municipal councils in Norway are legally obliged to consult with their local citizens (Local Government Boundaries Act No. 10). Slightly over half of the municipalities did this by holding consultative referendums (Folkestad et al. Citation2019), while the remaining municipalities conducted population surveys or held public meetings. Since citizens were asked to vote or express their opinions on future mergers, many public debates at the local level resembled election campaigns, and the reform evoked strong emotions and massive political engagement. The debates that preceded the voting on the mergers in the municipalities therefore had the characteristics of political contests or battles (Folkestad et al. Citation2019).

In the second step, councillors voted on mergers in their local councils. Most councillors voted in line with their citizen’s preferences, regardless of their own original positions. In the third step, in June 2017, the national parliament decided that 119 municipalities should merge, reducing the total number from 428 to 356. According to the Norwegian Constitution, parliament has the power to overrule the decisions of municipal councils. Consequently, 11 of the 47 mergers ratified by parliament involved at least one municipality in which the council had voted against the merger. These 11 cases were labelled ‘forced mergers’ by the media and opponents. All mergers were implemented in January 2020.

Public debates on the mergers were encouraged in the local and regional media, on social media, and in physical meetings, including council meetings and public gatherings. Almost all Norwegian municipalities are served by local or regional newspapers, and these are by far the most important sources of political information and the primary arenas for public debate (Høst Citation2021; Karlsen and Steen-Johnsen Citation2021). The regional divisions of the public broadcasting company NRK are also important sources of political information. Although social media is becoming increasingly influential, in 2018, when the survey was conducted, only a small proportion of citizens, mostly young people, stated that social media was their main source of political information (Karlsen and Steen-Johnsen Citation2021). There are notable differences in the quality and extent of political coverage in the local press (Høst Citation2019). Although, in most municipalities, the merger process received considerable media attention, especially in municipalities served only by regional newspapers, coverage may have been limited. It is important to note that the local media landscape in Norway is not polarised (Bastiansen Citation2014), suggesting that both citizens and politicians are likely to engage in the same debates. Moreover, editorial guidelines mandate balanced coverage of any given topic, theoretically ensuring that different perspectives on a topic are presented in an impartial, equal, and balanced manner. However, the realisation of this journalistic standard often focuses more on presenting opposing viewpoints than on comprehensively exploring all facets of a topic (Wahl-Jorgensen et al. Citation2017). Consequently, media platforms may foster debates that emphasise one or two perspectives on a topic, neglecting other significant viewpoints, and if councillors feel that their problem representations are inadequately reflected in the media debate, this may be true. Nonetheless, it is crucial to note that councillors are expected not only to follow these debates but also to actively participate in them, whether indirectly through editorial content or directly through opinion pieces or interviews (Winsvold Citation2013). This involvement gives them opportunities to influence the range of problem representations in public debate.

Previous studies on merger reforms have shown that the main arguments put forward in public debates are remarkably similar in different countries: proponents of reform focus on economies of scale, increased regional competitiveness, and better welfare services, while opponents emphasise the unique histories of municipalities, identities, local democracy, and autonomy (Drew, Grant, and Campbell Citation2016; Jakobsen and Kjær Citation2016; Jakola Citation2018; Swianiewicz Citation2010, Citation2018; Terlouw Citation2016, Citation2018; Verhoeven and Duyvendak Citation2016). Drew, Razin, and Andrews (Citation2019) showed that those in favour of mergers argue positively that mergers will ensure good things, such as a better economy or more jobs, and negatively that mergers are necessary to avoid a bleak future. For their part, opponents of mergers primarily use negative arguments, the most common of which are arguments that mergers will have terrible side effects and result in exactly the opposite of what the proponents predicted.

Nevertheless, the question of issue ownership in merger debates is not necessarily clear-cut. Jakola (Citation2018), for example, revealed that the predominantly pro-reform issue of public service provision has also been used in counter-reform arguments claiming that service delivery is adversely affected by the greater geographical distances within large municipalities. Similarly, although the concept of local democracy is generally invoked to argue against mergers, it can also be argued, in line with Dahl and Tufte (Citation1973), that larger government bodies can assume greater responsibilities and thus encourage stronger citizen participation in local politics. This perspective suggests that mergers strengthen rather than weaken local democracy (Swianiewicz Citation2010). According to this reasoning, the Norwegian merger reform was touted by the national government as a ‘democracy reform’.

Materials and methods

To capture the relevant local problem representations, we conducted interviews with a sample of 29 participants from 11 municipalities in different parts of Norway. In six of the municipalities, the council had voted in favour of the merger, whereas the other five had voted in favour of remaining independent. The interviewees included journalists from the local media, heads of administration, and elected councillors and mayors who had actively taken positions in favour of or against the mergers of their municipalities. The interviews were conducted in autumn 2016, immediately after the municipal councils voted on the mergers, but before the national parliament made its final decision. Interviewees were asked which issues dominated the local public debates about municipal mergers in their municipalities. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analysed in two steps. First, we read them exploratively, creating a new category for each issue mentioned. Subsequently, we coded all the interviews according to the occurrence of the mentioned issues. The issues that emerged as important corresponded with the issues mentioned in the literature on municipal mergers (Drew, Grant, and Campbell Citation2016; Jakobsen and Kjær Citation2016; Jakola Citation2018; Swianiewicz Citation2010, Citation2018; Terlouw Citation2018; Verhoeven and Duyvendak Citation2016). The most frequently mentioned issue was public services (mentioned by 27 of 29 interviewees), followed by identity or sense of belonging (26/29), local democracy (17/29), municipal economy (16/29) and local jobs (10/29) (see Appendix A for an overview). All issues involved arguments in favour of or against a merger. The category ‘identity/sense of belonging’ contained, for example, the idea that local identities would be lost in mergers (anti), but also the idea that the merging municipalities would lead to common regional identities (pro). In the ‘public services’ category, interviewees referred to the need for larger service units (pro) but also to fears that mergers would be used to cut local services (anti).

The five most frequently occurring issues were used as response categories in two survey questions about individual and dominant problem representations in the merger debate. These questions were asked in a nationwide survey in autumn 2018, which was sent to all elected Norwegian councillors with a known email address (9,196 out of 10,500). We received 3,378 responses, which corresponded to a response rate of 40% of those who received the questionnaire and 37% of all Norwegian local councillors. Mayors and male councillors were slightly overrepresented in the sample, but we identified no other systematic bias.

To measure ‘individual problem representation’, councillors were asked to indicate which of the five issues – public services, identity, local democracy, municipal economy, or local jobs – was most important to them when deciding on a merger.Footnote1 shows that ‘local services’ was considered the most important issue by most councillors, followed by ‘local democracy’.

Table 1. Individual problem representations among councillors (percentage).

To measure dominant problem representation, the councillors were asked to assess how much attention the same five issues received in the public debate on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘very little attention’ = 1 to ‘great attention’ = 5.Footnote2 shows that no single issue was perceived as completely dominant.

The prevalence of hostile media bias was assessed by comparing politicians’ own problem representations with what they perceived to be the dominant representations. We assumed that politicians within the same municipality would, overall, be exposed to the same media coverage. Therefore, any discrepancies in the perceived dominant problem representations were likely to indicate interpretative bias. We expected that hostile media bias would manifest when politicians perceived the problem representations of their opponents as more prominently featured than their own.

The categorisation of a councillor as a ‘winner’ or ‘loser’ in the municipal merger debate depended on the outcome of the merger process. Two groups were coded as ‘losers’: councillors who were against the merger but whose municipality eventually merged (labelled ‘anti-losers’) and councillors who were in favour of the merger but whose municipality remained unmerged (labelled ‘pro-losers’). The remaining two categories, where there were matches between councillors’ own preferences and the outcomes, were coded as ‘winners’. Attitudes towards the mergers were measured by asking councillors for their opinions on the mergers at the time of council voting. shows the distribution of councillors according to their positions on the mergers and whether they were on the winning or losing sides.

Table 2. Perceived dominant problem representation: percentages of councillors who believed that various issues received great attention in the public debates.

As the table shows, the ‘anti-winners’ – those who were against mergers in municipalities that did not merge – represented the largest group (38% of respondents). The ‘pro-winners’ were the 23% who supported and experienced mergers in their municipalities. Overall, 61% of the sample were ‘winners’ and 39% were ‘losers’. Among the ‘losers’, 31% were ‘pro-losers’ in favour of mergers but whose municipalities did not merge, and 8% were ‘anti-losers’ who were against mergers but whose municipalities merged.

Two limitations of the data should be mentioned. First, the survey data regarding perceptions of dominant problem representations may have been subject to recall bias. The data were collected after the debate had calmed down (i.e., more than a year after the councils voted); therefore, it is likely that councillors’ memories of the debates were distorted simply because of the time that had passed. Moreover, it is possible that councillors tended to remember the debates in terms of the outcomes (i.e., they remembered the arguments in favour of the outcome better). However, even if councillors’ memories may be distorted, elapsed time and outcome is an evenly distributed source of noise, potentially clouding the memories of all respondents and therefore should not affect the difference between winners and losers. Based on our data, we cannot determine whether or how the passage of time strengthened or weakened the bias in the two groups of winners and losers.

Second, although we detected media bias by assessing differences in perceptions within each municipality, we had no objective measure of the prevalence of different issues in local debates. Therefore, we cannot say conclusively which respondents had distorted images of media coverage or how distorted those images were. However, analysing the media coverage across all local and regional media suggested that all politicians had distorted pictures of which issues dominated the debates. Using the Norwegian ‘Atekst’ database, which contains media articles from nearly all Norwegian newspapers, we identified the proportion of articles in the large mass of regional and local newspapers that simultaneously referred to ‘municipal merger’ and one of the five problem representations. As shown in , the actual coverage of the whole country differed greatly from the coverage perceived by politicians, as shown in .

Table 3. Distribution of winners and losers.

Both before the voting (2014–2017) and in the following year, when the survey was conducted (2018), local jobs and the local economy were reported on far more extensively than the other topics (see ). The overall gap between actual and perceived coverage indicated that politicians had distorted perceptions of media coverage.

Table 4. Regional and local coverage of dominant problem representations: number of news items (absolute numbers and percentages in last row; N = 18,738).

Results

To determine whether a generalised hostile media bias existed among councillors (H1) and whether its activation differed between winners and losers (H2), we compared each councillor’s individual representation of the problem with what they perceived to be the dominant representation in the local public debate.

We begin by analysing the relationship between individual problem representations and attitudes towards municipal mergers. The relationship is shown in .

Figure 1. The relationship between individual problem representations and attitudes towards municipal merger.

illustrates the different importance councillors assigned to the issues, depending on their attitudes towards the municipal mergers. For those in favour of mergers (the proponents), local services were the most important issue, followed by the local economy. For those against merger (the opponents), local democracy was most important. However, although there were clearly some ‘no’ issues (local democracy and local identity) and ‘yes’ issues (local economy and local services), a significant proportion of the anti-merger councillors considered local services to be the most important issue.

The dataset had a natural two-level structure, with individual councillors nested within municipalities, which allowed us to conduct a multilevel regression analysis. To determine whether councillors tended to perceive their own or their opponents’ problem representations as dominant (H1) and whether congruence between individual and perceived problem representations was greater for those who won their elections (H2), we conducted a series of multilevel regression analyses with ‘perceived problem representation’ as the dependent variable. Perceived problem representation was captured by asking how much attention each of the five issues received in local debates about municipal mergers. We treated each of these issues as a dependent variable, rated from ‘very little attention’ = 1 to ‘great attention’ = 5. To analyse the distribution of responses, we considered councillors’ top issues (as shown in and ), their opinions on the mergers (pro or anti), and whether they were on the winning or losing side. We used two models for each dependent variable: one model without an interaction effect between attitude and winning and one model with this interaction effect. The interaction between attitude (pro/anti) and outcome (merge/not merge) allowed us to test whether the different groups of councillors perceived the debate differently depending on the relationship between attitude and outcome. In other words, the interaction allowed us to analyse the impact of being ‘genuine’ losers and winners in this political conflict. In line with the suggestions of Thomas et al. (Citation2006) and Mitchell (Citation2012), we calculated the marginal effects of the interaction coefficients. The results are shown in and .

Table 5. Multilevel regression results: relationships between perceptions of the debates, attitudes towards mergers, and most important issues among winners and losers.

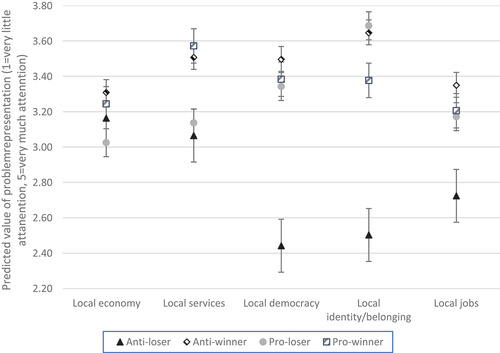

Figure 2. Perceptions of issue dominance according to attitude to merger and merger outcome (pro/anti*winning/losing).

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) showed that between 2% and 8% of the variance could be ascribed to the municipal level (see also Appendix B for empty models). This could mean that how the councillors considered the public debate was weakly connected to the actual content of the local public debate, or it could mean that there was little variation between municipalities because, for example, the local public debates in general reflected the national debate. In short, the characteristics and viewpoints of the councillors themselves, and not characteristics of the municipalities (e.g., the content of the local public debate), are most important when analysing debate perceptions.Footnote3

The findings indicate that proponents of the merger perceived that local democracy and local identity – key issues for the opposition – were emphasised in the public debate; that is, those who voted ‘yes’ believed that the arguments against the merger (‘no’ issues) were more prominent, while those opposed to the merger did not perceive their concerns as receiving equivalent prominence. This partially corroborates H1, suggesting that hostile media bias was indeed present among councillors, curiously centred on ‘no’ issues.

The variables used to measure which issues were most important to the councillors yielded few significant results. Those who thought that local identity was the most important issue believed that the local economy was a less prominent issue in the local debate. Councillors who considered local jobs to be the most important issue tended to think that local jobs were important in the local debate.

When the interaction effect between pro/anti*winners/losers was included, some interesting results emerged regarding perceptions of the issues of local democracy, identity, and jobs. The results suggest that the anti-losers were the ‘odd ones out’ in this group of councillors. Compared to the other groups, the anti-losers were likely to feel that the issues of democracy, identity, and jobs were less prominent in local debates. This is best illustrated by the marginal effects for each group, which showed the predicted value of perceived problem representation on a scale of 1–5 for the dependent variables ().

shows that the difference between the anti-losers and the other three groups of councillors on both the local democracy and local identity questions is more than one scale point on a scale of 1–5. On the issue of local jobs, the differences between the anti-losers and the other councillors were small, but still significantly different.Footnote4 The winners (and to some extent, the pro-losers) tended to evaluate all issues comparably emphasised, with the exception that more pro-losers than pro-winners believed that local identity (which was an anti-issue) played an important role. However, the sizes of the differences were not on par with those of the anti-losers. Except for the issue of local identity, the winners perceived all issues as more prominently featured in the local debate than did the losers. This observation suggests that more winners than losers perceived the debate as inclusive and diverse.

In the final part of this analysis, we will further investigate whether the congruence between the councillors’ own problem representations and their perceptions of the dominant problem representation depended on whether they were on the winning or losing sides of the local councils’ decisions. We constructed a dummy variable to capture the congruence between one’s own problem representation and the perception of the dominant representation. If a councillor believed that the local economy was strongly or very strongly emphasised in the local debate, and that same councillor also claimed that the economy was the most important issue regarding the merger question, this was coded as a ‘match’. If, on the other hand, the councillor felt that there was little emphasis on the local economy (including an either/or option) and that the local economy was the most important issue, this was coded as a ‘mismatch’. shows the predicted probabilities for matches between own and perceived problem representations (see Appendix D for the regression table).

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of congruence between own problem representation and perception of local debate according to attitude to municipal merger and being on winning or losing side of a council decision.

shows that there was less congruence between own problem representation and perceived dominant problem representation among losers, especially among anti-losers.

To summarise, the survey results partially supported our hypothesis that councillors perceived issues consistent with their own problem representation as less prominent in public debates, but they perceived their opponents’ issues as more prominent (H1). This suggests that hostile media bias was present among all councillors. Those in favour of the merger felt that the arguments against the merger were more dominant, whereas those against the merger felt that the arguments in favour of the merger were more dominant. However, apart from the issue of local employment, there was no correspondence between politicians’ individual problem representations and their perceptions of local public debates. Furthermore, we found a greater mismatch between politicians’ own problem representations and their perceived dominant problem representations among losers and especially among anti-losers (partially supporting H2), as well as an indication that more winners than losers perceived the debate as more balanced.

Concluding discussion

The analysis showed that local councillors in Norway had different ideas regarding municipal merger reform: although most merger supporters saw the merger primarily as a public service issue, opponents saw it mainly as a question of local democracy. In other words, proponents and opponents did not agree on problem representation. In line with H1, councillors from both sides of the debate tended to believe that the opposing side’s arguments were better represented than their own. Pro-merger councillors perceived the issues on the ‘no’ side of the debate – local democracy and sense of belonging – to have dominated the public debate; conversely, anti-merger councillors, for whom these issues were important, perceived them as under-represented. The general belief that the media favoured opponents’ problem representations over politicians’ own indicates that hostile media bias was activated throughout. Moreover, councillors who lost merger elections in the council were even more inclined to view the media as biased in their disfavour than those who won. In line with our assumptions (H2), the discrepancy between own problem representation and perceived dominant problem representation was even larger among losers. The discrepancy was particularly pronounced among the anti-losers (i.e., those who opposed mergers in the municipalities that were ultimately merged).

Unexpectedly, our results showed that, in contrast to the losers, the winners perceived all issues as having received more extensive attention in the public debate. More winners than losers perceived the public debate as comprehensive and inclusive, supporting the assumption that attribution bias was present. Both winners and losers benefitted from perceiving the media as hostile: for the losers, hostile media explained their defeats; for the winners, it made their victories even more convincing. Nevertheless, the impulse to attribute their results to external factors was probably stronger for losers. Conversely, it was probably advantageous for winners to view media debates as thorough and comprehensive because it supported their beliefs that they won fairly. In a perceived fair media environment where all viewpoints were adequately represented, they could attribute their victories to the superiority of their arguments and the soundness of their perspectives, convincing the public of the merits of their proposals. Thus, our data suggest that people tend to interpret media coverage in ways that reinforce their beliefs and seek narratives that justify the outcomes of political processes while preserving their sense of self-esteem. Losers who attribute their failures to hostile media may maintain the belief that their solutions would have been adopted under fairer conditions; winners who perceive the media as inclusive and impartial may attribute their victories to the strength of their own arguments. This supports the assumption that media bias – whether it manifests as hostile media bias or a perceived all-inclusive debate – is mobilised when it confirms one’s own views and beliefs.

The pronounced presence of hostile media bias among anti-losers emphasises the situational nature of media perceptions. For a local politician who had campaigned against a merger, the local council’s vote in favour of a merger was a definitive defeat, taking the preferred option of maintaining the status quo off the table. An anti-loser was confronted with the reality of a decision that ran directly counter to his or her position, with no way of changing the outcome. A politician in favour of a merger faced defeat if the council voted against the merger. However, unlike the opponents of the merger, those in favour of the merger could take comfort in the fact that other opportunities might arise to promote mergers in the foreseeable future, thus mitigating perceived media hostility. Therefore, media confirmation bias appears to be inextricably linked to the future political opportunities available to those who judge the media. This suggests that media perceptions depend not only on whether one’s side has won or lost, but also on the long-term political implications of defeat. The less definitive and hopeful the post-vote political landscape appears, the less likely it is that the media will be perceived as hostile. This nuance adds to our understanding of how the political context and prospects influence individuals’ interpretations of media coverage.

The study has some limitations that provide opportunities for further studies on the relationship between being on the winning or losing side of a debate and how the debate is perceived. First, while the observation that winners and losers perceived debates differently strongly suggests the presence of some form of bias, we could not measure the extent of that bias to determine whether winners or losers were most affected by it. Therefore, we do not know whether both groups viewed the debates in biased terms or whether one group’s perspective was closer to the reality of the coverage. To determine which group was most affected by the bias, we would need to measure the prevalence of the different problem representations in local debates. Second, our interpretations of the results rest on the assumption that politicians within the same municipality were exposed to the same media debates. However, this assumption requires further investigation to confirm the validity of our results. Third, the assumption that hostile media bias is particularly activated among losers due to their need to attribute their losses to external factors is based on a theoretical argument and has not been empirically tested. It is plausible, and indeed likely, that other cognitive processes were at work, contributing to different levels of hostile media bias activation between winners and losers. The exact dynamics that determine winners’ and losers’ evaluations of media coverage and the factors that contribute to these perceptions need to be further explored. Future studies could contribute to a more detailed understanding of the cognitive and situational factors that underpin and possibly clarify the media evaluation processes of winners and losers of political debates. Another interesting avenue for future research would be to investigate whether politicians’ own media involvement and perceptions of their own media influence trigger or dampen hostile media bias.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2024.2332634

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The wording in the questionnaire was: ‘Which of these issues did you emphasise when the question of merger was decided? (Chose one issue only)’.

2. The wording in the questionnaire was: ‘When you consider the merger debate in your municipality, how much attention would you say the following topics received?’.

3. See Appendix C for a more detailed table that also includes variables at the municipality level. None of the aggregate variables yielded significant results, except some results that related to the mayor’s party affiliation and a slight tendency for councillors from poor municipalities to believe that local jobs dominated the debate more than other issues.

4. We also performed an analysis controlling for social background and municipality characteristics. The inclusion of background and local context did not alter the findings in Table 3. However, some additional findings should be mentioned (see Appendix C for more detailed results). First, the results indicated that more female than male councillors tended to view all topics as prominent, but it is not clear from the evidence why this was so. The relationship between gender and perceptions of public debates should be a topic for further research. Second, councillors from the leading pro party (Conservatives – the party that led the government-initiated reform), perceived that their main arguments on public services and the economy had not been emphasised but that the no-issue of local democracy attracted extensive attention.

References

- Bacchi, C. 2009. Analyzing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be?. Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education.

- Bastiansen, H. G. 2014. “Fra konflikt til konsensus? Partipressens fall [From Conflict to Consensus. The Fall of the Party Press].” Pressehistorisk Tidsskrift 21 (21): 16–44.

- Borah, P. 2011. “Conceptual Issues in Framing Theory: A Systematic Examination of a Decade’s Literature.” Journal of Communication 61 (2): 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01539.x.

- Coe, K., D. Tewksbury, B. J. Bond, K. L. Drogos, R. W. Porter, A. Yahn, and Y. Zhang. 2008. “Hostile News: Partisan Use and Perceptions of Cable News Programming.” Journal of Communication 58 (2): 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00381.x.

- Dahl, R. A., and E. R. Tufte. 1973. Size and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dennis, C., and J. N. Druckman. 2007. “Framing Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054.

- Drew, J., B. Grant, and N. Campbell. 2016. “Progressive and Reactionary Rhetoric in the Municipal Reform Debate in New South Wales, Australia.” Australian Journal of Political Science 51 (2): 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2016.1154926.

- Drew, J., E. Razin, and R. Andrews. 2019. “Rhetoric in Municipal Amalgamations: A Comparative Analysis.” Local Government Studies 45 (5): 748–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1530657.

- Esaiasson, P., S. Arnesen, and H. Werner. 2023. “How to Be Gracious About Political Loss—The Importance of Good Loser Messages in Policy Controversies.” Comparative Political Studies 56 (5): 599–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140221109433.

- Feldman, L. 2011. “Partisan Differences in Opinionated News Perceptions: A Test of the Hostile Media Effect.” Political Behavior 33 (3): 407–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9139-4.

- Feldman, L. 2017. “The Hostile Media Effect.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication, edited by K. Kenski and K. H. Jamieson, 549–564. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Folkestad, B., J. E. Klausen, J. Saglie, and S. B. Segaard. 2019. “When Do Consultative Referendums Improve Democracy? Evidence from Local Referendums in Norway.” International Political Science Review 42 (2): 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512119881810.

- Gunther, A. C., C. T. Christen, J. L. Liebhart, and S. Chih-Yun Chia. 2001. “Congenial Public, Contrary Press, and Biased Estimates of the Climate of Opinion.” Public Opinion Quarterly 65 (3): 295–320. https://doi.org/10.1086/322846.

- Gunther, A. C., and J. L. Liebhart. 2006. “Broad Reach or Biased Source? Decomposing the Hostile Media Effect.” Journal of Communication 56 (3): 449–466.

- Gunther, A., C. Nicole Miller, and J. L. Liebhart. 2009. “Assimilation and Contrast in a Test of the Hostile Media Effect.” Communication Research 36 (6): 747–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650209346804.

- Gunther, A. C., and K. Schmitt. 2004. “Mapping Boundaries of the Hostile Media Effect.” Journal of Communication 54 (1): 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02613.x.

- Hansen, G., and H. Kim. 2011. “Is the Media Biased Against Me? A Meta-Analysis of the Hostile Media Effect Research.” Communication Research Reports 28 (2): 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2011.565280.

- Hartmann, T., and M. Tanis. 2013. “Examining the Hostile Media Effect As an Intergroup Phenomenon: The Role of Ingroup Identification and Status.” Journal of Communication 63 (3): 535–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12031.

- Høst, S. 2019. “Hvite Flekker, Medieskygger og Støtten Til Lokalavisene [White Spots, Media Shadows and Support for Local Newspapers]. Meld. St. 17 (2018–2019).”

- Høst, S. 2021. “Avisåret 2020: Papiraviser og betalte nettaviser.” [The Newspaper Year 2020: Paper and Web Editions]. Høgskulen i Volda 108/2021.

- Jakobsen, M., and U. Kjær. 2016. “Political Representation and Geographical Bias in Amalgamated Local Governments.” Local Government Studies 42 (2): 208–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2015.1127225.

- Jakola, F. 2018. “Local Responses to State-Led Municipal Reform in the Finnish-Swedish Border Region: Conflicting Development Discourses, Culture and Institutions.” Fennia - International Journal of Geography 196 (2): 137–153. https://doi.org/10.11143/fennia.69890.

- Karlsen, R., and K. Steen-Johnsen. 2021. “Nyheter, Sosiale Nettverk Og Lokalpolitisk Orientering I lokalvalgkamp” [News, Social Networks and Political Orientation in Local Elections.” In Lokalvalget 2019: Nye Kommuner - Nye Valg? [The 2019 Local Election: New Municipalities – New Elections?], edited by J. Saglie, S. B. Segaard, and D. A. Christensen, 117–142. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Matthes, J. 2013. “The Affective Underpinnings of Hostile Media Perceptions: Exploring the Distinct Effects of Affective and Cognitive Involvement.” Communication Research 40 (3): 360–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211420255.

- Mitchell, M. N. 2012. Interpreting and Visualizing Regression Models Using Stata. Vol. 558. Texas: Stata Press.

- Morewedge, C. K. 2009. “Negativity Bias in Attribution of External Agency.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 138 (4): 535–545. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016796.

- Perloff, R. M. 2015. “A Three-Decade Retrospective on the Hostile Media Effect.” Mass Communication & Society 18 (6): 701–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1051234.

- Perloff, R. M. 2017. A Three-Decade Retrospective on the Hostile Media Effect. London: Routledge.

- Regjeringen. 2016. Fakta om kommunereformen [Facts About the Municipal Reform]. Regjeringen.

- Shah, D. V., M. D. Watts, D. Domke, and D. P. Fan. 2002. “News Framing and Cueing of Issue Regimes.” Public Opinion Quarterly 66 (3): 339–370. https://doi.org/10.1086/341396.

- Slothuus, R. 2008. “More Than Weighting Cognitive Importance: A Dual-Process Model of Issue Framing Effects.” Political Psychology 29 (1): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00610.x.

- Swianiewicz, P. 2010. ”If territorial fragmentation is a problem, is amalgamation a solution? An East European perspective.” Local Government Studies 36 (2): 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930903560547.

- Swianiewicz, P. 2018. “If Territorial Fragmentation is a Problem, is Amalgamation a Solution? – Ten Years Later.” Local Government Studies 44 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1403903.

- Taylor, S. E., and J. D. Brown. 1988. “Illusion and Well-Being: : A Social Psychological Perspective on Mental Health.” Psychological Bulletin 103 (2): 193–210.

- Terlouw, K. 2016. “Territorial Changes and Changing Identities: How Spatial Identities Are Used in the Up-Scaling of Local Government in the Netherlands.” Local Government Studies 42 (6): 938–957. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2016.1186652.

- Terlouw, K. 2018. “Transforming Identity Discourses to Promote Local Interests During Municipal Amalgamations.” Geo Journal 83 (3): 525–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-017-9785-8.

- Thomas, B., W. R. Clark, and M. Golder. 2006. “Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses.” Political Analysis 14 (1): 63–82.

- Vallone, R., P. Lee Ross, and M. R. Lepper. 1985. “The Hostile Media Phenomenon: Biased Perception and Perceptions of Media Bias in Coverage of the Beirut Massacre.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49 (3): 577–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.3.577.

- Verhoeven, I., and J.Willem Duyvendak. 2016. “Enter Emotions. Appealing to Anxiety and Anger in a Process of Municipal Amalgamation.” Critical Policy Studies 10 (4): 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2015.1032990.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K., M. Berry, I. Garcia-Blanco, L. Bennett, and J. Cable. 2017. “Rethinking Balance and Impartiality in Journalism? How the BBC Attempted and Failed to Change the Paradigm.” Journalism 18 (7): 781–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916648094.

- Winsvold, M. 2013. Lokal digital offentlighet [The Local Digital Public Sphere]. No. 384. Series of Dissertations Submitted to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Oslo.