Abstract

Increasing food prices have implications for basic subsistence, have a strong price visibility and symbolic value, and are characterized by high volatility and inelasticity of demand. Research thus assumes that food price is an important trigger for unrest. Yet, whether food is an especially potent driver for people’s willingness to engage in collective action, or whether it concerns grievances about general inflation, is unknown. Does food have a greater effect on the willingness to participate in unrest? The paper investigates the relative importance of food in mobilization potential by using unique data from a survey experiment in Johannesburg, South Africa. The experiment collects information on how price increases in food, fuel, and electricity affects respondents’ willingness to engage in unrest. The results show a higher willingness to engage in collective action when presented with increasing living expenses, regardless of whether it is food, fuel or electricity, compared to stable prices. We also consider the level of risk exposure to price hikes, and find that those who report going hungry in the last year have a higher willingness to engage in unrest than those who do not. Thus, food access influences the willingness to partake in unrest during price hikes, also for commodities seemingly unrelated to food. This suggests that for those who are most affected by a price hike it is less important what type of commodity it is. The question is whether it introduces further strain on an already hard-stretched budget.

Los precios en aumento de los productos de alimentación tienen implicaciones sobre la subsistencia básica. Además, estos precios en aumento también tienen una fuerte visibilidad en materia de precio y un valor simbólico, y se caracterizan por una alta volatilidad e inelasticidad de la demanda. Por lo tanto, la investigación asume que el precio de los alimentos es un desencadenante importante de agitación social. Sin embargo, no sabemos si el precio de los alimentos es una causa lo suficientemente relevante para que las personas decidan participar en acciones colectivas, o si estas acciones están más relacionadas con quejas sobre la inflación general. ¿Tienen los precios de los alimentos un mayor efecto sobre la disposición de la población a participar en disturbios sociales? Este artículo investiga este asunto utilizando datos únicos de un experimento de encuesta en Johannesburgo, Sudáfrica. Este experimento recoge información sobre cómo los aumentos de precios de los alimentos, del combustible y de la electricidad influyen sobre la voluntad de los encuestados a participar en disturbios sociales. Los resultados muestran una mayor disposición a participar en acciones colectivas cuando existe un aumento de los costes de vida, pero este efecto no es más fuerte para el precio de los alimentos en comparación con otros productos básicos. También tenemos en cuenta el nivel de exposición al riesgo de las subidas de precios, y descubrimos que quienes declaran haber pasado hambre en el último año tienen una mayor disposición a participar en disturbios sociales que los que no lo hacen. Por lo tanto, el acceso a los alimentos tiene potencial en materia de movilización, no solo debido a los precios, sino también en términos de cómo influye en la disposición a participar en disturbios sociales durante los aumentos de precios. Esto también ocurre para productos básicos aparentemente no relacionados con los alimentos. Esto sugiere que para aquellas personas que se ven más afectadas por un aumento de precios, el tipo de producto no resulta tan importante. La pregunta que nos hacemos es si esto crea más presión sobre una situación que ya es vulnerable y sobre un presupuesto muy ajustado.

La hausse des prix de l’alimentation entraîne des conséquences pour les moyens de subsistance de base. Ces prix sont particulièrement visibles et leur valeur symbolique, mais ils se caractérisent également par une volatilité élevée et un manque d’élasticité de la demande. Aussi la recherche présuppose-t-elle que le prix de l’alimentation constitue un facteur déclencheur important d’agitation urbaine. Pourtant, nous ne savons pas avec certitude si l’alimentation, à elle seule, pousse effectivement les gens à l’action collective, ou s’il s’agit davantage d’un mécontentement quant à l’inflation générale. L’alimentation incite-t-elle davantage à l’action ? Cet article s’intéresse à cette question à l’aide de données uniques issues d’une expérience de sondage à Johannesburg, en Afrique du Sud. L’expérience recueille des informations sur l’effet de l’augmentation des prix de la nourriture, du carburant et de l’électricité sur le désir du participant de se joindre à l’agitation. D’après les résultats, ce désir augmente quand le coût de la vie augmente, mais l’effet ne se renforce pas pour le prix de la nourriture, comparé à d’autres marchandises. En prenant aussi en compte le niveau d’exposition au risque de hausse des prix, nous observons que les personnes signalant avoir souffert de la faim durant l’année passée sont plus enclines à participer à l’agitation sociale que les autres. Ainsi, l’accès à la nourriture possède un potentiel de mobilisation vis-à-vis de son prix, mais aussi parce qu’il a une incidence sur la volonté de prendre part à l’agitation lors des hausses de prix, et même pour des marchandises qui n’auraient aucun rapport avec la nourriture. Aussi, pour les personnes les plus affectées par les hausses de prix, le type de marchandise aurait une importance moindre. Une questions apparaît alors : ces situations de vulnérabilité et d’insuffisance budgétaire ne s’en trouvent-elles pas aggravées ?

Introduction

Extant academic literature suggests a positive association between higher food prices and unrest.Footnote1 Studies of food and contentious action increased in the wake of the food price spikes in 2007–2008 and 2010–2011 and the corresponding unrest that followed (Bellemare Citation2015; Bush and Martiniello Citation2017; Sneyd, Legwegoh, and Fraser Citation2013). The interest in and importance of understanding the societal impacts of increasing living expenses has only further been strengthened after the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Concerns about high inflation has swept across the globe where countries grapple with a cost of living crisis, and increasing prices of commodities such as energy, food and fertilizer prices has corresponded with protests in a wide range of countries in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East (Marsh, Rudolfsen and Aas Rustad Citation2022; Hossain and Hallock Citation2022).

The role of food prices is often pointed to as a particularly relevant phenomenon in the relative deprivation–conflict nexus (e.g. Gurr Citation1970; Hendrix and Haggard Citation2015). This is because food is assumed to have specific features that separates it from other commodities, related to the importance of food for basic subsistence, its price visibility, symbolism, and volatility and inelasticity of demand (Weinberg and Bakker Citation2015). Yet, while previous research points to food as one of the most fundamental aspect in the relative deprivation–conflict link, the question of whether food is a more important commodity compared to other living expenses in motivating participation in unrest remains so far unexplored. This article seeks to shed light on this question: Is the cost of food an especially compelling driver for people’s willingness to engage in unrest compared to other commodities that make up a substantial share of the household budget?

To address this question, the study uses an individual-level approach by asking consumers about their willingness to engage in unrest following an increase in the price of food, fuel and electricity respectively. In the real world, the prices of these items often shift in tandem. As we seek to identify the importance of one commodity price hike over another, and since the outbreak of unrest may also influence the price of food and other items, we need a research design that can account for endogeneity and allow us to distinguish between cause and effect (Raleigh, Choi and Kniveton Citation2015). The study therefore makes use of a vignette experiment where we randomly assign respondents to treatment and control conditions consisting of fictional news stories of coming price hikes and subsequently map consumer reactions. We study how information about different commodity prices affects the stated willingness to engage in unrest.

We use data from a survey experiment conducted in Johannesburg, South Africa, and the case is particularly well suited to study the phenomenon of interest for several reasons. Johannesburg has experienced a relatively high number of both peaceful and violent events, especially since the mid 2000s (Hart Citation2013; Paret Citation2017; Tournadre Citation2018). Also, as in South Africa in general, Johannesburg exhibits widespread poverty, inequality and food insecurity (Chatterjee, Czajka and Gethin Citation2021; Rudolph et al. Citation2012; Statistics South Africa Citation2019). In addition, the phenomenon of interest is in a context of urban consumers, with corresponding population density and heterogeneity that may provide mobilization potential (Verpoorten et al. Citation2013). At the same time, the case exhibits significant variation with regards to both unrest activity and socioeconomic status.

The results show that respondents are more willing to engage in collective action when presented with increasing living expenses compared to stable prices, regardless of whether it is food, fuel or electricity. We also assess the level of vulnerability to price hikes for the individual, and find that those who report going hungry in the last year are more willing to engage in unrest over commodity price hikes than those who do not. Thus, food has mobilization potential not only due to its price, but also in terms of how food insecurity influences the willingness to partake in unrest during price hikes, also for commodities seemingly unrelated to food. This suggests that for those who are most affected by a price hike it is less important what type of commodity it is. The question is whether it introduces further strain on an already vulnerable situation and hard-stretched budget.

We contribute to the literature on food and unrest in several ways. First, while the literature on food price and collective action is growing rapidly, previous studies have relied primarily on aggregated data. Filling this gap in the literature, the study utilizes individual-level data to assess the importance of increased cost of living for mobilization potential. Second, to our knowledge, this study is also the first to map reactions to different commodity price hikes, comparing food, fuel and electricity in an experimental design to assess the willingness to engage in unrest depending on variation in the source of increased living expenses. Finally, the paper contributes to the literature on relative deprivation and social conflict by accounting for not only reactions to increasing prices, but also the individual’s vulnerability to it. While previous studies have largely used aggregate food prices as a proxy for relative deprivation for the individual, we measure risk exposure directly by accounting for food insecurity. Thus, the study seeks to grapple and understand the relative importance of food in collective action. While increasing living costs can have adverse impacts on urban consumers, we have little understanding of how the underlying vulnerability to such a shock impact mobilization potential. Some strands in the literature point to the importance of food because of its fundamental nature, others suggest that food functions as the last straw that ignites unrest due to general inflation. Our study suggests that it is both, where higher cost of living increases the willingness to engage in unrest, but this willingness is contingent on the vulnerability to price hikes.

In the following sections, we briefly present an overview of the existing literature. We then outline the theoretical framework and hypotheses, before introducing the research design and analysis. Subsequently, we discuss some of the threats to inference given the research design and external validity, before making some concluding remarks.

Increasing Cost of Living and Social Unrest

The body of research on the role of food in precipitating unrest is vast and have long historical roots (see e.g. Abbs Citation2020, Berazneva and Lee Citation2013, Bienen and Gersovitz Citation1986, Brinkman and Hendrix Citation2011, Bush Citation2010, De Winne and Peersman Citation2021; Hendrix and Brinkman Citation2013, Hertel Citation2014, Heslin Citation2021, Jones, Mattiacci and Braumoeller Citation2017, Koren and Bagozzi Citation2016, Popkin Citation1979, Rudé Citation1964, Scott Citation1976, Tilly Citation1971, Citation1983, Thompson Citation1971, Walton Citation1994, Weinberg and Bakker Citation2015), and there is an emerging consensus in the field that increasing food prices lead to unrest, especially in urban areas (Demarest Citation2014; Rudolfsen Citation2020). Recent quantitative studies, using both local (Raleigh, Choi and Kniveton Citation2015; Smith Citation2014) and global (Bellemare Citation2015; Hendrix and Haggard Citation2015; Sternberg Citation2012) food prices, have found that higher food prices increase the risk of unrest. Arezki and Brückner (Citation2014), for example, point to the widening gap between rich and poor when prices increase. This inter-temporal change in relative deprivation subsequently increased the risk of conflict. In the same vein, Smith (Citation2014) proposes that consumer grievances could increase unrest if the elite captures increased revenue, and the effect of rising prices on unrest is driven by consumer grievance over increased economic pressure. Economic grievances increase due to higher costs as a larger share of the household budget is spent on increasingly costly living expenses.

Relevant work in this context is also studies exploring the link between energy prices and protest. While the literature on electricity prices and unrest is, to our knowledge, scantFootnote2, there has been an uptick in the number of studies focusing on fuel prices and various forms of social unrest in recent years (see e.g. Agbonifo Citation2023; Dube and Vargas Citation2013; Ishak and Farzanegan Citation2022; Jetten, Mols and Selvanathan Citation2020; Natalini, Bravo and Newman Citation2020). For example, Vadlamannati and de Soysa (Citation2020) find that both high oil prices in oil-importing countries and low oil prices i oil-producing countries lead to protest, conditional on the level of foreign exchange reserves. In addition, investigating 41 countries between 2005 and 2018, McCulloch et al. (Citation2022) find that domestic fuel price shocks are a key driver of riots. They also find that countries with large fuel subsidies are more at risk of fuel riots when this policy becomes unsustainable to uphold due to fiscal concerns. In a meta study including a review of 350 studies, Blair, Christensen and Rudkin (Citation2021) find that higher oil prices is positively associated with conflict.

Based on previous research, there is overall agreement in the literature that increasing living expenses (especially in the form of food and fuel prices) is positively associated with social unrest. However, we know much less about their relative importance in mobilization potential based on consumer preferences. In the following, we therefore outline two propositions on the motivation to partake in unrest based on increasing living expenses, and whether the increasing cost of food would be an especially potent driver in this regard.

Why Food Prices May be Especially Aggrieving

The link between higher living costs and social upheaval tends to be explained through relative deprivation, a central theory in conflict research (Gurr Citation1970). Relative deprivation is the experienced gap between a person’s desired and actual situation, defined in terms of perceived entitlements. Relative deprivation increases with the loss of entitlements when living expenses rise. Feelings of deprivation could occur by a person’s assessment of deteriorating welfare, or by interpersonal or inter-group comparisons.

Studies often point to food as something especially aggrieving, where feelings of relative deprivation should become particularly salient in the case of food price hikes. This is because food has well-known features that separate it from other commodities, such as the necessity of food purchase for basic subsistence, its price visibility, symbolism, and the volatility and inelasticity of demand. The first and most fundamental proposition for why food price would be an especially likely mechanism through which grievances lead to conflict is the necessity of purchasing food for basic subsistence: “The argument would seem particularly plausible for food, which is the most basic of all necessities and the one most likely to embody explicit or implicit political entitlements” (Hendrix and Haggard Citation2015, 145). According to Gurr, relative deprivation is most likely to occur over issues that people believe they are rightfully entitled, where it is likely that food would be one such entitlement. Thus, food prices would have a particular effect on the welfare of poor individuals who are net purchasers of food (see e.g. D’Souza and Jolliffe (Citation2012)).Footnote3 Food purchase as an essential human necessity suggests that rising food prices lead to rising food insecurity and a reduction in the opportunity cost of violent unrest. This argument is based on the special nature of food as necessary for human survival compared to other commodities or costs of living. In the words of (Bush Citation2010, 119): “Food is a commodity and its use value, unlike those of most other commodities, provides for the maintenance and reproduction of life itself.” Grievance-induced unrest would therefore seem particularly plausible for food (Pinstrup-Andersen and Shimokawa Citation2008).

Second, food price could be an especially compelling driver for unrest due to the visibility of increasing food prices for the consumer. While aggregate economic trends and smaller changes in the GDP may be difficult for individuals to track and make calculations about in order to identify potential grievances, food prices are much easier to observe as consumers make choices based on their own finances, rather than aggregate economic trends. Food is a good purchased regularly and is therefore according to Weinberg and Bakker (Citation2015) the best available indicator of an individual’s economic well-being. It provides a direct assessment of scarcity and is therefore both more easily and more frequently observed.

Third, food has a symbolic value as a threat to subsistence. For example, according to Simmons (Citation2016), the threat to affordable access to water and tortilla in Mexico heightened solidarity within and between communities, where the threat to subsistence goods were not only material threats but also threats to community. The threat to subsistence helps bridge cleavages between social groups and facilitate widespread mobilization. Similarly, according to (Abbs Citation2020, 285), the cross-cutting nature of increasing cost of food sets it apart from other types of issues. Food price shocks provide an opportunity for movements to mobilize across intra-ethnic divides due to food prices being a unique and symbolic issue, where “[…] food price spikes generate superordinate goals that unify normally divided groups.” Also, Hossain and Scott-Villiers (Citation2017) write that food riots signal that the state is unable to meet the most basic condition of the social contract, which creates pressure on the state to address the most fundamental of failings.

Increasing food prices may be distinctive as a driver of unrest compared to other costs of living for two additional reasons. First, food prices are generally more volatile than other commodities. This volatility may create acute hardships during times of particularly sharp increases in ways that more predictably steady increases in other costs of living would not. For example, the cost of housing is generally much more stable than the cost of food. While the cost of housing is often the largest single expenditure, a family’s rent or loan payment is often set for months or years in advance of when the expense will be incurred. While an increase in the cost of housing can have a significant impact on a household’s budget, it is generally predictable in advance and, therefore, more easily adapted to. Food prices, however, can change daily, monthly or weekly, which can place unforeseen stress on household budgets (Tadesse et al. Citation2014). One commodity that may exhibit similar levels of volatility to food is the cost of fuel, particularly petrol or gasoline for transportation. The cost of fuel, however, is distinct from food in another important way: rising food prices tend to have a more substantial impact on the welfare of the poor than rising fuel prices (Chaudhry and Chaudhry Citation2008; Yu Citation2014).Footnote4

The inelasticity of demand for food means that increases in food prices do not affect all consumers equally. Engel’s law states that as income increases, the proportion of household income that is spent on food decreases. Conversely, poor households tend to spend a higher proportion of household income on food purchases. Consequently, the economic hardship created by rising food prices may lead to a higher degree of perceived relative deprivation among poor households. Weinberg and Bakker (Citation2015) note the disproportionate impact of food price increases on poor consumers, where the effect of price fluctuations on individual consumers is unambiguously unique due to the high proportion of expenditure on food and its nonsubstitutability, distinguishing food from any other commodity. If food prices are an especially compelling motivation for unrest because of their unique effect on consumers, we would expect to see a higher willingness to engage in collective action when faced with rising food prices. To test this, we formulate our first hypothesis:

H1: Individuals will be more willing to engage in collective action when presented with the prospect of increasing food prices than when presented with the prospect of increases in the cost of fuel or electricity rates.

Why Food Prices May Not Be Especially Aggrieving

So far we’ve argued for why food prices may be an especially potent driver for urban unrest. However, there are also arguments for why food prices would not be especially compelling for unrest participation. Rather, it could be that higher inflation and increasing living cost in general after price hikes is linked to unrest participation.

Importantly, several contributions in the literature emphasize that food price-related unrest often is triggered by underlying grievances in society. This means that expressing grievances about the price of food can serve as a pretext for addressing other fundamental social issues, where food can function as a mobilization tool for political entrepreneurs such as opposition elites and other non-state stakeholders to address wider socioeconomic issues (Rudolfsen Citation2021). For example, in her work on Bangladesh and India, Heslin (Citation2021) emphasizes that many food riots are not, in fact, directly caused by the issue of food. Rather, the outbreak of food riots is contingent on the local context, where the presence of existing actors who use decreased food access to address existing grievances shape the occurrence of riots. Thus, the issue of food can help mobilize collective action around a range of grievances. Also, Bush and Martiniello (Citation2017) argue that food riots are part of larger political and economic crises. Looking at Uganda, Burkina Faso, Tunisia and Egypt, they claim that the unrest was inseparably linked to a political and economic struggle against state authorities. Also, (van Weezel Citation2016, 3) emphasizes that food-related protests are likely part of a larger struggle against issues such as inequality and political oppression: “As such, food price spikes provide a political trigger, often signaling other underlying factors of dissatisfaction, for the population to resort to violence.” Thus, we might see a correlation between food price and unrest not because of food prices’ unique effect on the willingness to engage in unrest, but simply because food prices fluctuate more often than other expenses and therefore more frequently presents itself as a circumstance where mobilization is possible. Food price shocks may provide a window of opportunity for mobilization towards causes that in principle can extend far beyond the availability of affordable food (McCarthy and Zald Citation1977).

More substantially, increasing food prices and unrest may be linked, not necessarily because food is the most fundamental element in the relative deprivation explanation, but because food price hikes represent a more general strain on the household budget, which subsequently increases grievances. While the relative deprivation argument seems very relevant to the issue of food, the explanation also applies to other expenses that cause a sudden increase in the cost of living. For example, the widespread unrest in Iran in November 2019 erupted after a surprise increase in the price of fuel, quickly escalating into the deadliest unrest since the 1979 Islamic revolution with more than 1500 dead (Fassihi and Gladstone Citation2019; Reuters Citation2019). Since 2000, there has been social upheaval over the cost of fuel and electricity in most parts of the world, such as India (Majumdar and Chakraborty Citation2020), Nigeria (Obiezu Citation2020), Zimbabwe (Marima Citation2019), Spain (Keeley Citation2008), Haiti (Associated Press Citation2018) and France (BBC News Citation2018). While these are highly different places with a variety of socioeconomic and political challenges, the protesters have the same dissatisfaction in trying to manage a hard-stretched budget. The resulting unrest could either be directed against the government, or the perceived source of the hardship, especially in authoritarian regimes where people have no other recourse to a change in leadership (Brancati Citation2014). This suggests that the mechanism linking increasing food prices to the willingness to engage in unrest is not necessarily due to the unique nature of food as a commodity. Rather, increasing living costs in general are a trigger for socioeconomic grievances and subsequent social upheaval. This leads us to our second hypothesis:

H2: Individuals will be more willing to engage in collective action when presented with the prospect of increasing commodity prices, regardless of category.

Vulnerability to Commodity Price Hikes

To better understand the role of commodity price hikes for the willingness to participate in unrest, we also need to account for the level of vulnerability to a price hike, considering the level of susceptibility increasing commodity prices has on the individual. There are many different types of coping strategies that individuals may take to deal with the impact of a price hike, such as seeking substitutes, altering consumption patterns, rationing, and the like (FAO Citation2021). However, it is unlikely that all consumers would have the coping mechanisms needed to cushion a price shock, and the risk exposure to price hikes is not homogeneous. People prioritize what they spend money on and as expenditures increase, people cut the least valued items first, leaving food and water as the last items cut (Maslow Citation1943; Sen Citation1982). Even small increases in consumer prices can have severe consequences for people who already spend a considerable share of their money on food. Therefore, consumers more sensitive to price changes might present a motivational force to engage in unrest due to limited coping mechanisms to put pressure on state authorities to intervene (Ivanic, Martin and Zaman Citation2012; Simmons Citation2016; Weinberg and Bakker Citation2015).

We proxy vulnerability to price hikes by comparing those who report experiencing hunger in the last year with those who report experiencing no hunger to account for that the impact of higher prices might vary between individuals. Indeed, based on previous literature it is assumed that food is relevant for mobilization potential because of its fundamental nature for basic subsistence. Thus, we also assess whether the willingness to engage in unrest is higher when this fundamental need is threatened, looking into whether risk exposure influences the willingness to engage in collective action due to increasing prices. We would expect those who are more heavily impacted by a price hike to be more willing to engage in collective action.

We calculated the mean percentage of household income spent on food, electricity and fuel by income quantile in South Africa in Table A2 in the Supplementary Appendix, showing that the share of household spending is substantially higher for food compared to other living expenses for poorer households. The question is then whether the source of the price spike matters, as long as it threatens a hard-stretched budget. For example, assessing the impact of the food, fuel and financial crisis in 2008–2011, Heltberg et al. (Citation2013) find that the varying price hikes led to significant hardships, especially among the poor with limited coping response and resilience. We therefore assess the level of vulnerability to price shocks in predicting unrest participation. Lack of access to food may contribute to unrest participation as a more chronic grievance, rather than a specific food price shock that triggered participation. Thus, we formulate our third hypothesis:

H3: Individuals reporting higher levels of risk exposure will be more willing to engage in collective action when presented with the prospect of increasing commodity prices.

South Africa

We investigate the motivational role of food prices compared to other household expenses using South Africa as an empirical case. Since the mid 2000s, there has been a substantial increase in the number of unrest events in South Africa, usually referred to as “service delivery protests,” and concern mainly the perceived failure of the government to provide basic services (De Juan and Wegner Citation2019; Lodge and Mottiar Citation2016). Despite the African National Congress (ANC) government’s investments in services, they have been unable to overthrow the structural inequalities from the apartheid era and establish inclusive citizenship for its population (Alexander Citation2010; Beresford Citation2016; Booysen Citation2007; Dawson and Sinwell Citation2012; Desai Citation2002; Royeppen Citation2016; World Bank Citation2018).

Prior to 1990, political protest played a significant role in the overthrow of the apartheid regime and the transition to democracy. Unrest, therefore, tend to be viewed as a legitimate tool to achieve political aims (Alexander et al. Citation2018; Ballard, Habib and Valodia Citation2006; Bedasso and Obikili Citation2016; Friedman Citation2012; von Holdt Citation2013; Welsh Citation2000). Most collective action is peaceful, and engaging demonstrations and strikes is entrenched in the South African Constitution (Lancaster Citation2016). However, violent collective action has increasingly been seen as a tactic successful in achieving political outcomes (Bohler-Muller et al. Citation2017). Community protests represent both a continuation of the social movements on the apartheid era and a new form of resistance: “The recent wave of community protests resembles the earlier wave of social movements in that it is rooted in the country’s poverty-stricken townships and informal settlements”(Paret Citation2017, 9).

While these service delivery protests tend to be fragmented and concern immediate grievances among community members, the claim making on behalf of the state is at its core about wider issues relating to socioeconomic rights and exclusion (Brown Citation2015; Duncan Citation2016). In Johannesburg, these unrest events mainly occur in working class areas referred to as townships (Bond Citation2012), that traditionally have been ANC strongholds where the party still enjoys relatively high levels of support. Thus, unrest in the area is usually not understood or framed as an attempt to remove the ANC, but rather part of a wider repertoire of action to get attention and redress from the ruling party. Indeed, these events tend to erupt after several attempts by the community to engage with the local government (Dawson Citation2014; Runciman Citation2017).

We believe South Africa is a particularly interesting context in which to study the roles of both food and unrest, and focus on apartheid-era black and colored townships in Soweto, south west of central Johannesburg, and the black township of Alexandra, north of central Johannesburg. The chosen case of Alexandra and Soweto is suitable for several reasons. As in South Africa in general, there is widespread poverty and unemployment in both townships (Seekings and Natrass Citation2015). According to Statistics South Africa, almost 20% of South African households had inadequate access to food in 2017 (Statistics South Africa Citation2019), and more than 60% of households that experienced hunger in 2017 were found in urban areas (Statistics South Africa Citation2019). Thus, the survey does not focus on the elite or better-paid segments in society. That being said, Soweto is a large and diverse township with different levels of wealth that should not be oversimplified. The residents in Soweto are better off than other South Africans on several indicators, although the unemployment rate is higher: “The township is neither homogeneously squalid nor generally rich” (Ceruti Citation2013, 55). The township of Alexandra, on the other hand, being the oldest township and one of the poorest areas in South Africa, is known for its over-crowded informal housing and widespread poverty (Bonner and Nieftagodien Citation2008). Meanwhile, as with Soweto, Alexandra is also known for its political engagement, using tactics such as demonstrations and boycotts to raise awareness about specific issues. Thus, Alexandra tends to be central in the emergence of social movements (Curry Citation2012). However, while the townships experience frequent unrest, there is large variation in the type of tactics and repertoires chosen to engage with authorities. The citizens make use of a variety of different strategies to engage in politics, either through institutionalized and legal formal channels, or outside the scope of conventional politics, and political engagement in the townships is certainly not reduced to spontaneous eruptions of violence (Booysen Citation2007; Oldfield and Stokke Citation2006). Thus, the case represents significant variation in both food access and unrest participation.

For the purpose of the study we have chosen what we believe is a most likely case, where the priors suggest that the case is likely to fit the theory (Levy Citation2008). In other words, if there is an additional effect of food prices on the willingness to participate in unrest, the characteristics should imply that we are more likely to uncover such an effect here, as Johannesburg is marked by characteristics including widespread unemployment, relatively poor households and high levels of inequality in an urban setting. Previous research suggests that these characteristics are often present when food price hikes lead to unrest. The approach would therefore also consider whether food price spikes leading to unrest would be especially likely when other socioeconomic grievances are present. This provides an opportunity to study the effect of food prices on individual level willingness to engage in unrest.

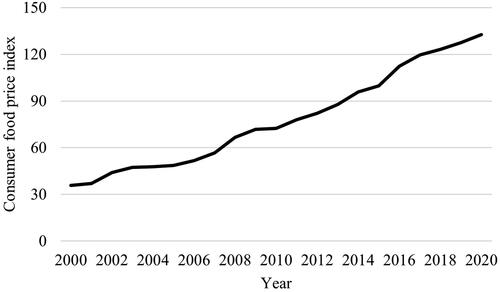

shows that food prices have steadily increased in South Africa in the last decade, and has had a higher increase compared to the global trend, seen in Figure A1 in the Supplementary Appendix. With this steadily rising trend, it is likely that poor consumers are facing an increasingly challenging situation to manage expenses.

Figure 1. Food price index, South Africa: 2000–2020. Data from FAOSTAT (2015 = 100) (FAOSTAT Citation2021).

Research Design

The analysis makes use of a survey experiment to investigate whether the price of food has a unique effect on individuals’ willingness to participate in unrest. Survey experiments have many advantages, such as strong internal validity in that they clearly distinguish between cause and effect by randomly assigning respondents to treatment and control conditions (see e.g. Gibson Citation2008). This is especially important given that food price and conflict is characterized by an endogenous relationship (Raleigh, Choi and Kniveton Citation2015). The random assignment of the vignettes should ensure that the treatment and control groups are comparable (Angrist and Pischke Citation2015). Equally important, as we would like to isolate the effect of one commodity price increase over another, it is challenging to make use of a research design using observational data in the traditional sense. Vignettes, however, provide a useful way to elicit respondent preferences, which are crucial given our research question. Such vignettes facilitate the simulation of real-world scenarios while controlling the amount and type of information provided, making it possible to distinguish between different scenarios that might otherwise be overlapping (Kinder and Palfrey Citation1993). The experiment has been designed to maximize ecological validity, by modeling situations that is highly familiar to the participants. Hence, although the stories are fictional, they resemble what the participants experience in their natural settings, which is likely to elicit realistic responses.

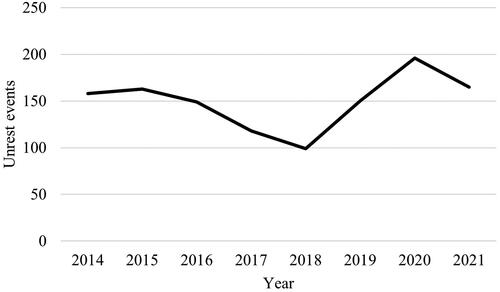

We conducted the interviews in June and July in 2017, and shows the trend of unrest events in recent years in the province of Gauteng, where Johannesburg is located. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data project (ACLED), there were 118 unrest events in Gauteng municipality in 2017 (ACLED Citation2021). We can see from the figure that unrest levels were relatively lower in 2017, before increasing again after 2018. Events that occurred around the time of the survey were violent demonstrations in Alexandra reported in early July, where residents blockaded parts of the highway with burning tires and rocks. There were also instances of unrest during the summer in Soweto. For example, in Lenasia South community members covered the road with rocks and tires in July. In May there were protests that turned violent in Eldorado park, and the Dobsonville municipal office was set on fire in late June during unrest over service delivery. Also, in Diepkloof protesters were blocking roads and burning tires in several instances in May. While unrest events are relatively frequent in the area, to our knowledge there were no major violent events at the time that would significantly influence the survey responses.

Figure 2. Unrest events in Gauteng: 2014–2021. Data from Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). Unrest events include demonstrations, including protesters (peaceful) and rioters (violent) (Raleigh and Dowd Citation2015).

We surveyed a total of 608 respondents from Soweto and Alexandra between the ages of 18 and 65.Footnote5 The respondents were first asked survey questions on previous unrest participation, political attitudes and community affiliations and lived poverty and food security, and the vignette experiment came at the end of the survey. We applied a multistage sampling design to ensure representation of the demographics in the target areas, and the Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) included Alexandra, and Bram Fischerville, central east, central west, Devland, Diepkloof, Eldorado Park, Meadowlands, Orlando and Protea Glen in Soweto. The secondary sampling units (SSUs) were randomly selected based on census enumeration areas, which were assigned to two teams of fieldworkers, consisting of one team leader and four enumerators per team. The two teams started at a predetermined intersection nearest to each center point based on the random sampling of enumeration areas. The interviewers alternated between male and female respondents and applied a three-house interval pattern to select households. The surveys were conducted using Android tables through Google Forms.

We presented each respondent with a randomly selected, hypothetical video news item concerning living expenses. The experimental conditions included three treatments, and one control. The treatments differ with respect to the type of living expense that is projected to increase in the coming month. In the first vignette (“control”), the respondent is provided with information that living expenses will be stable in the following month. The second treatment (“fuel prices”) provides information about expected fuel price increases in the coming month, while the third (“food prices”) and fourth (“electricity prices”) treatments provide information about expected food and electricity price increases, respectively. The respondents were shown video clips of a person reading hypothetical news stories.Footnote6 To reduce bias in presenting different videos, the same person read out the four different vignettes, where the text only differed in the type of commodity that was presented.Footnote7 shows a comparison of the different treatment groups by age, income, lived poverty index and union membership.

Table 1. Treatment group comparison.

After the participants saw the vignettes, they were asked to answer which of the following actions they would be most likely to take:

Attend a local Ward Committee meeting to express concern

Engage in a labor strike demanding higher wages

Attend a demonstration march to Johannesburg City Hall

Shut down traffic on local roads to draw attention to your situation

Do nothing

We present a range of different tactics to the respondent to better tease out the preferred response to a given price hike. As it is not necessarily the case that unrest related to food only manifests itself through violence, we wanted to include a range of possible outcomes, from conventional peaceful channels to more contentious behavior. Also, while a specific tactic such as going on strike may be relevant for respondents with a steady income, this is not a viable option for someone who is unemployed. More specifically, these actions were given as options because they are common actions that South African citizens take to express grievances. First, local Ward Committee meetings are the most local level of government interaction. Municipal Ward Representatives hold regular meetings to hear from their constituents. Second, engaging in labor strike to demand higher wages is a possible route for employed respondents to take in order to tackle higher prices. Both attending a labor strike and a Ward meeting are not expressions of unrest, but they are nevertheless forms of collective action. Next, a demonstration march to Johannesburg City Hall is a peaceful and legal method of collective action that citizens might take if they feel that their grievances are not being heard through institutionalized political channels. Finally, blocking roads with rubbish or burning tires has become a common method for citizens in lower income areas to draw attention to issues that are not being addressed.

A dependent variable that measures a person’s willingness to engage in unrest, and not their actual participation, is agnostic about the costs and constraints of such participation. Certainly, respondents who are willing to engage in contentious action may not act upon their stated response (see e.g. von Uexkull, d’Errico and Jackson Citation2020). However, previous studies suggest that there is a link between attitudes and behavior concerning an object, and that “[…] factors that lead to participation in violent behaviors are also likely to affect the formation of attitudes towards violent behavior” (Rustad Citation2016, 109). For example, Linke, Schutte and Buhaug (Citation2015) find a positive relationship between people’s attitudes toward violence and an increase in the incidence of violence. While the survey experiment is not able to capture actual participation of unrest as a result of increased living expenses, we can test the first part of the causal chain that captures the mobilization potential for unrest through increased prices. We aim to capture grievances by asking about the respondents’ willingness to participate in different types of collective action, and this perceived grievance is a necessary precondition for engaging in unrest.

Another aspect of the survey is that the respondents are faced with scenarios of higher prices, not lived experiences of the same. It is different to feel the consequences of higher prices directly, compared to being presented with a hypothetical situation. If the mechanism from food price to unrest, for example, involves a psycho-social reaction to hunger through aggression it cannot be recreated in hypothetical scenarios. However, it is likely that the respondent has experience with price hikes and the corresponding consequences from the past and is therefore able to relate to the vignette and its possible impact.Footnote8 Given the challenges with conducting surveys with sensitive issues such as direct participation, this study offers an important contribution regarding how grievances and willingness for unrest participation form mobilization potential. Also, we would arguably nonetheless be able to capture whether food is seen as something especially important by the respondent.

Finally, while a survey vignette experiment facilitates comparison of different household expenditures, asking about individuals’ preferences regarding participation in various forms of unrest necessitates being mindful of ethical aspects (Eck Citation2011). Although the vignettes cannot capture emotions as a mechanism directly, the vignettes may trigger an emotional response. To reduce the risk of emotional stress, the vignettes resemble news reports that occur in South African media outlets. Also, the enumerators all had previous training and experience with implementing surveys at the University of Johannesburg, and were trained and supervised before the data collection effort began to minimize potential risks and to ensure the respondents’ informed consent and anonymity. The respondents were informed that they were not required to take part in the interview, that participation was completely voluntary, that they had the right to decline to answer any particular question(s), that no identifying information was gathered, and that they could end the survey at any time. Table A1 in the Supplementary Appendix displays summary statistics.

Results

The responses regarding most likely action by treatment group are presented in . A tabular analysis indicates that the treatment condition and response are not statistically independent (x2-statistic = 37.56; p = 0.000). Thus, a given treatment influences the probability of a given response. Because we presented the respondents with a menu of possible reactions, we use a multinomial logit regression to compare the willingness to engage in each type of activity when “treated” with an increase in prices of fuel, food, or electricity respectively, compared to the baseline control, stable prices.

Table 2. Response by treatment group.

presents the results of the analysis. Model 1 includes only the treatment conditions as categorical explanatory variables. Because assignment to treatment is randomized, control variables for respondent characteristics are unnecessary and would not provide any additional insight into willingness to engage in unrest. However, as it is important to consider the possibility that the results could be influenced by how the experiment was administered, Model 2 includes the enumerator as a control variable. The results are reported as exponentiated coefficients and should be interpreted as relative risk ratios (RRR). An RRR of over 1 indicates that respondents are more likely to be willing to take the stated action over the baseline treatment condition of stable prices and an RRR below 1 indicates a less likely response. Thus, for a unit change in the predictor variable, from stable prices to a price increase, the relative risk ratio of the willingness to take action over doing nothing is expected to change by a factor of the given parameter estimate while other variables in the model are held constant. This means that we contrast outcomes (different price hikes) with a common reference point (stable prices), and the effects (relative change in predicted probability) is always in relation to the reference category. For example, in M1 a respondent presented with fuel price increase is 80.8% more likely to be willing to attend a Ward meeting than a respondent presented with stable prices.

Table 3. Multinomial logit regression.

Overall, the results indicate that respondents presented with any of the treatment conditions, either fuel, food or electricity price increases, are more likely to be willing to attend a demonstration march and to shut down traffic than those presented with the control condition, stable prices. Also, we see that individuals consider attending a Ward Committee meeting to be the most appropriate response to an increase in electricity rates. Rosenthal (Citation2010) points to the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee as an organization addressing grievances related to electricity in a local context in Johannesburg. Resistance against the state-owned power utility Eskom is widespread in the townships due to blackouts caused by failures on electricity networks, but also deliberate power cuts from the company in areas because of non-payment of electricity bills (Deklerk Citation2021; Ngqakamba Citation2019). Notably, in South Africa, municipalities set the rates electricity distributors may charge for electricity, but municipalities have no control over fuel prices, which are set at the national level, or food prices, which are controlled by the government. This finding indicates that respondents are making strategic decisions about the action most likely to achieve a desired outcome. Additionally, individuals facing fuel price increases seem to be most likely to attend a demonstration march.

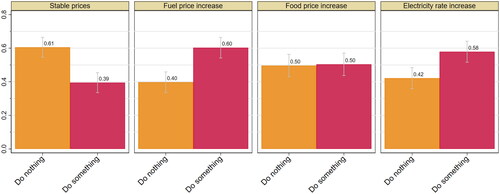

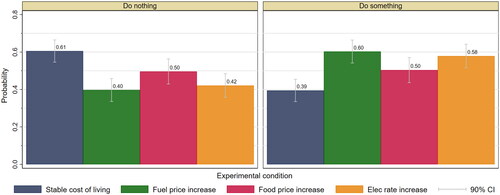

To ease interpretation, we present an aggregated panel where we collapse the categories in the dependent variable into Do something versus Do nothing and display the results graphically. shows the predicted margins from the multinomial logistic regression model by treatment, while shows predicted margins by response. These graphs were generated based on the results from model 3 in Table A3 in the Supplementary Appendix.Footnote9 We can see from that the effect of both fuel and electricity price rate increase is significantly different from doing nothing, while there is no such effect concerning food prices. Also, in the predicted margins by response shows that the model predicts a higher probability in the willingness to engage in some form of response when prices increase, but the effect is not more profound for the price of food.

The results indicate that individuals are more willing to engage in unrest activity when faced with increasing prices compared to stable prices, regardless of whether it is electricity, fuel or food.Footnote10 We do not find evidence that food price is an especially potent driver for respondents’ willingness to engage in unrest. Thus, H2 is confirmed, H1 is not.Footnote11

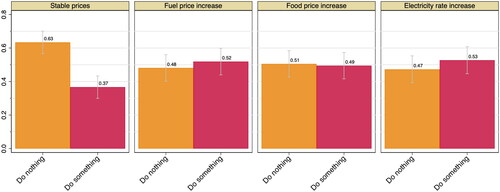

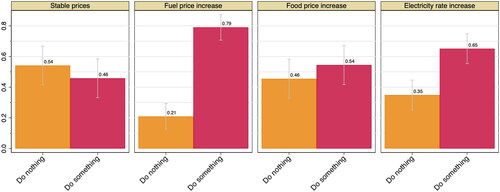

Finally, to test H3 we consider the level of risk exposure by comparing those who would be more heavily impacted by increasing prices to those who would not. Food access may be relevant for mobilization potential when a fundamental need is threatened, where experienced food insecurity influences the willingness to engage in collective action due to increasing commodity prices regardless of source. To account for risk exposure, we asked the respondents “In the last 12 months, since July of last year, were you ever hungry but didn’t eat because you couldn’t afford enough food?” includes respondents who report not going hungry (N = 389), and includes respondents who report going hungry (N = 177).Footnote12 We can see from that the effect of both fuel, food and electricity price is not significantly different from doing nothing for those who report experiencing no hunger in the last year. In contrast, looking at those that do report experiencing hunger in the last year in , both the effect of fuel and electricity is significantly different from doing nothing. Thus, price shock vulnerability may function as an contributing factor in the willingness to participate in unrest. For example, the widespread unrest in South Africa during the summer of 2021 erupted because of the jailing of Jacob Zuma. At the same time, the instability also led to unrest and looting “[…] by desperate people with little or no connection to Zupta, to secure food and basic necessities” (Reddy Citation2021, 2). Thus, while ignited by political developments, food insecurity played an important role for why many were motivated to join the unrest. Also, while positive, the effect of food price is not significantly different from doing nothing. There may be several reasons for this.

First, the group of people setting the prices for fuel and electricity is smaller and therefore may be more susceptible to collective pressures and more easily targeted in the South African context. For example, the South African Federation Trade Union organized a demonstration in August 2022 over the rising cost of living. Eskom had then applied for an increase in electricity prices during rising inflation (Africanews Citation2022). The demonstration targeted rising cost of living in general, but Eskom was pointed out as one of the sources of grievances in that campaign. Rising cost of living may influence levels of food insecurity, and food insecure individuals engage in mobilization over rising costs that are not restricted to food price.

Second, the results suggest that a hike in prices can have a significant impact on the household economy, regardless of whether it is the cost of food, fuel, or electricity (Heltberg et al. Citation2013). The implication is that rising food prices could lead to unrest, but so could increasing costs of living from any source. The importance of food in mobilization potential is seemingly not because of its price, but because the lack of secure access to food influence the willingness to partake in unrest in general. What the issue vulnerable individuals choose to mobilize over may vary, where the role of organizational ties in a given context is likely important (Rudolfsen Citation2023). For example, the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee has been central in mobilizing against electricity price hikes in Johannesburg in the past. Civil society organizations in the area and the degree of presence of government agencies to address specific issues may influence patterns of mobilization potential on the individual level. Depending on the local context, price hikes can function as a mobilization tool for political entrepreneurs such as opposition elites and other non-state stakeholders to address wider socioeconomic issues (Heslin Citation2021).

The analysis has sought to assess the relative importance of food in collective action. We find that higher cost of living increases the willingness to engage in unrest. We also find that respondents experiencing hunger have a higher willingness to engage in unrest over price hikes regardless of source, affecting the willingness to engage in unrest over increased cost of living in general.

Discussion

Can these results be applied elsewhere, or is this finding limited to the South African context? Certainly, South Africa has an exceptional history. The legacy of apartheid is still present, and South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world, where poverty and hunger is widespread (Chatterjee, Czajka and Gethin Citation2021; World Bank Citation2018). Also, as protest played a central part in the ending of apartheid, it has come to be seen as a legitimate channel to achieve political goals. However, we believe that the findings presented here are of value in other contexts as well. For example, the global commodity price spikes in 2007–08 corresponded with unrest in around 50 countries, and the latest price spike in 2011 contributed to a wave of unrest in a variety of countries, such as Egypt, Mexico, Kenya and Bangladesh (Abbott and Borot de Battisti Citation2011; Brinkman and Hendrix Citation2011). Also, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 exacerbated supply shortages in global energy and food markets. These in turn led to price increases and food and energy insecurity for millions of people, and protests over food and fuel occurred in a wide range of countries which include, among others, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Venezuela, Peru, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Sudan, Mauritius, Tunisia, Morocco, Turkey, and Pakistan (Marsh, Rudolfsen and Aas Rustad Citation2022; Abay et al. Citation2023).

Rising commodity prices have varying impacts in different countries, depending on trade regimes, price controls and domestic market structures. However, “[w]hile these pass-through effects vary considerably, it is clear that higher inflation has become a major socio-political issue and has led to social unrest across all continents” (Wodon and Zaman Citation2008, 4). Volatility in prices of commodities such as food and fuel are not unique to the South African context, nor is the use of unconventional political channels to raise issues and draw attention to grievances. The results therefore are likely to have relevance beyond the townships in Johannesburg, especially to other urban areas in middle-income countries that experience a high degree of socioeconomic inequality and widespread unemployment. However, to be able to assess the scope of the findings, it is necessary to investigate the relationship beyond the South African context.

With regards to the design, experiments are constructs that to a larger or lesser extent resemble reality, and there is a trade-off in terms of validity. While the random assignment of respondents to treatment and control facilitates causal inference and renders a high degree of internal validity, external validity may be a concern if the treatment does not in reality resemble the relevant phenomenon in question (Barabas and Jerit Citation2010). We argue that by constructing vignettes based on news reports, we present the respondents with something that is familiar, as media sources and politicians inform the South African public about price increases on different commodities frequently. The experiment has been designed to maximize ecological validity, by modeling situations that is highly familiar to the participants. Hence, although the stories are fictional, they resemble what the participants experience in their natural settings, which is likely to elicit realistic responses.

Another potential threat to inference is that the experimental condition exaggerates the stimuli of the treatment by introducing an atypical manipulation that rarely occurs in a natural setting (Kinder and Palfrey Citation1993). Although the concern that the clean environment in which the treatment is given could introduce a positive bias in the results, an arguably bigger concern for our study is the threat of contamination of the experimental setting by prior exposure. Meaning that, in the likely event that the respondents have been exposed to news items about price hikes in the past, this may produce an overly conservative estimate. However, the experiment strives to simulate events that are likely to occur in the real word: “[…] either there is a likelihood of contamination from real-world experience or the survey experiment explores a nonexistent or politically irrelevant phenomenon” (Gaines, Kuklinski and Quirk Citation2007, 12). Therefore, the estimates may have a negative bias, which comes at the cost of studying phenomena that have real-world relevance.

Also, we aimed to include commodities that are relevant for the consumer (e.g. expenses they are likely to spend money on), as we sought to capture the relative importance of food compared to other expenses that make up a large share of the household budget. However, in the current research design the treatments may be too thematically similar in how consumers weigh the impact of a price shock for each commodity to be able to pick up differences in effects. The somewhat differing levels of specificity in the vignettes may also influence our findings. Whereas fuel and electricity are specific commodities, staple prices might be perceived as more abstract by not referring to a specific commodity. However, while it can be challenging to assess how respondents perceive the different vignettes, we found it more coherent to refer to staple food in general than to choose a specific food commodity that might not be relevant for a given respondent. In addition, the presented commodity scenarios are unlikely to occur only in isolation, where commodities such as food and fuel can impact each other and rise simultaneously, and increasing prices of both has led to protests in the past (McCulloch et al. Citation2022). For example, higher fuel prices can negatively affect economic status by increasing cooking, heating and transportation costs that in turn increases prices of other basic commodities, including food (Boyd-Swan and Herbst Citation2012).

To assess whether these factors influence the results would require knowledge on the extent of previous news exposure by the respondents and the effect of a potential exaggeration of the treatment in a survey context, both of which are impossible to assess. As the pool of respondents remains and we only change the type of commodity, we are nonetheless able to consider and compare the relative impact of the different commodities on the willingness to engage in unrest, regardless if there is general upward or downward bias in the sample. While experiments can be more challenging to generalize from, we avoid spurious correlation as the random sampling allows us to estimate the average causal effect of the treatment in the population. However, it is still important to be explicit and keep these potential biases in mind when conducting a survey experiment. An avenue for future research would be to compare basic necessities with other commodities not defined as such, as well as measuring directly how basic commodities may influence each other and out a strain on the affordability on other basic commodities.

Conclusion

This article has sought to investigate the role of food as a driver of unrest relative to other living expenses using a survey experiment conducted in the areas of Soweto and Alexandra in Johannesburg, South Africa. The results suggest that individuals are more willing to engage in unrest activity when presented with the prospect of increasing commodity prices, regardless of whether it concerned food, fuel, or electricity, than when presented with the prospect of stable prices. Also, the findings presented here suggests that those with a higher risk exposure to price hikes have a higher willingness to engage in unrest over commodity price hikes than those who do not. This indicates that food prices are not more likely to cause unrest compared to other commodities, while vulnerability to price hikes, however, predicts higher willingness to engage in unrest regardless of shock. Seemingly, for those who are most affected by a price hike it is less important which commodity it is, what matters is whether it introduces further strain on an already hard-stretched budget.

Governments, international organizations and policy agencies are increasingly paying attention to the consequences of higher inflation and increasing food insecurity in an urbanized setting, where a growing urban population spend a substantial share of their household budget on food. Also, it is evident that individual-level vulnerability to price hikes increases the willingness to engage in unrest. Therefore, the societal impacts that may result from the mounting challenges of increasing urbanization and impact of rising living costs must be taken seriously and directly addressed in policy making, also in terms of its impact on social instability. This implies proactive and targeted policies that aim to stabilize and reduce prices of basic commodities. While governments are faced with difficult trade-offs in tackling higher prices and inflation pressures, this study emphasizes the need for tailored safety nets and subsidies that explicitly target the poor.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (311.8 KB)Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We understand unrest as an overarching term for various forms of coordinated action involving multiple individuals, and focus here on such collective efforts occurring in urban areas. We use collective action and unrest interchangeably throughout the article. The action can be more or less legitimate, organized, legal and violent (Opp Citation2009; Tilly Citation1978). While we probe different types of collective action, we argue for similarities in the underlying process that might generate contentious action (McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly Citation2001). The different forms of actions included here are attending ward meetings to raise concern, demonstrations, strikes, and shutting down traffic. Armed conflict is not included in this definition. While the term unrest may have negative normative associations with it, we pass no judgment on collective action as a reaction to increasing costs. Unrest is a well-established term in the literature, and we use it here to encompass a variety of possible responses to increased household spending.

2 There has been a significant number of protests related to electricity prices in recent years, including a wide range of countries such as Bulgaria, Italy, Sri Lanka and Lebanon (Hossain and Hallock Citation2022). More research on this topic is therefore in high demand.

3 Certainly, the overall impact of increasing food prices depends on whether the individual or household is net producer or consumer. The income of farm households, often the poorest income group in developing countries, may increase due to higher food prices. However, studies have found that the overall impact of food prices on poverty is generally adverse as poor people tend to be net consumers of food and thereby hurt by higher food prices. This is especially true for urban households, which is the focus of this paper (see e.g. Cohen and Garrett Citation2010; Ivanic, Martin and Zaman Citation2012).

4 It should be noted that rising fuel commodity prices do have a spillover effect on food commodity prices (Baffes Citation2007). This article, however, focuses on the direct effect of rising consumer prices on urban purchasers.

5 The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at [large US public University], protocol number 2014-10-0093.

6 The respondents were informed after the interview that the news stories were fictional.

7 The scenarios presented in the vignettes are reported in the Supplementary Appendix.

8 See e.g. Figure 1 for an overview of the increasing food price levels in South Africa between 2000 and 2020.

9 Figure A3 in the Supplementary Appendix shows the predicted margins for all five outcomes by treatment, and figure A4 shows the predicted margins by response, generated based on the results from model 2 in Table 3.

10 As two positive and significant coefficients may still be statistically distinguishable from another even if their confidence intervals overlap, we also formally test whether the predictors for fuel, food and electricity are statistically different from one another for the collapsed outcome category (Do something/Do nothing), as well as each outcome separately in model 6–10 in Table A4 in the Supplementary Appendix.

11 We also conducted regression models with additional controls, including gender, age, level of education and whether the respondent discusses politics, rendering similar results (see models M11 and M12 in Table A5 in the Supplementary Appendix.

12 The graphs were generated based on the results from models 4 and 5 in Table A3 in the Supplementary Appendix.

References

- Abay, Kibrom A., Clemens Breisinger, Joseph Glauber, Sikandra Kurdi, David Laborde, and Khalid Siddi. 2023. “The Russia-Ukraine War: Implications for Global and Regional Food Security and Potential Policy Responses.” Global Food Security 36: 100675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2023.100675

- Abbott, Philip, and Adeline Borot de Battisti. 2011. “Recent Global Food Price Shocks: Causes, Consequences and Lessons for African Governments and Donors.” Journal of African Economies 20 (Supplement 1): i12–i62. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejr007

- Abbs, Luke. 2020. “The Hunger Games: Food Prices, Ethnic Cleavages and Nonviolent Unrest in Africa.” Journal of Peace Research 57 (2): 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319866487

- Africanews. 2022. South Africa: Trade unions protest rising cost of living, record-high fuel prices. Rédaction Africanews. https://www.africanews.com/2022/08/24/south-africa-trade-unions-protest-rising-cost-of-living-record-highfuel-prices.

- Agbonifo, John. 2023. “Fuel Subsidy Protests in Nigeria: The Promise and Mirage of Empowerment.” The Extractive Industries and Society 16: 101333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2023.101333

- Alexander, Peter. 2010. “Rebellion of the Poor: South Africa’s Service Delivery Protests – A Preliminary Analysis.” Review of African Political Economy 37 (123): 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056241003637870

- Alexander, Peter, Carin Runciman, Trevor Ngwane, Boikanyo Moloto, Kgothatso Mokgele, and Nicole van Staden. 2018. “South Africa’s Community Protests 2005–2017.” South African Crime Quarterly 63 (63): 27–42. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2018/i63a3057

- Angrist, Joshua D., and Joern-Steffen Pischke. 2015. Mastering Metrics: The Path from Cause to Effect. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Arezki, Rabah, and Markus Brückner. 2014. “Effects of International Food Price Shocks on Political Institutions in Low-Income Countries: Evidence from an International Food Net-Export Price Index.” World Development 61 (September): 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.04.009

- Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). 2021. ACLED Dashboard. Accessed 22 February 2024. https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard/F9EE8D3DEE7F6F60FB4E950553E62CA3.

- Associated Press. 2018. “Haiti Suspends Fuel Price Hike After Protesters Riot.” July 18. https://apnews.com/article/66c3359313074a36a55c306c28f47fc6.

- Baffes, John. 2007. “Oil Spills on Other Commodities.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4333. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/7319/wps4333.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Ballard, Richard, Adam Habib, and Imraan Valodia. 2006. Voices of Protest: Social Movements in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

- Barabas, Jason, and Jennifer Jerit. 2010. “Are Survey Experiments Externally Valid?” American Political Science Review 104 (2): 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000092

- BBC News. 2018. “France Fuel Unrest: ‘Shame’ on Violent Protesters, Says Macron.” 25 November. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-46331783.

- Bedasso, Biniam E., and Nonso Obikili. 2016. “A Dream Deferred: The Microfoundations of Direct Political Action in Pre- and Post-Democratisation South Africa.” The Journal of Development Studies 52 (1): 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1036041

- Bellemare, Marc F. 2015. “Rising Food Prices, Food Price Volatility, and Social Unrest.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 97 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aau038

- Beresford, Alexander. 2016. South Africa’s Political Crisis: Unfinished Liberation and Fractured Class Struggles. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Berazneva, Julia, and David R. Lee. 2013. “Explaining the African Food Riots of 2007–2008: An Empirical Analysis.” Food Policy. 39 (April): 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.12.007

- Bienen, Henry, and Mark Gersovitz. 1986. “Consumer Subsidy Cuts, Violence, and Political Stability.” Comparative Politics 19 (1): 25–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/421779

- Blair, Graeme, Darin Christensen, and Aaron Rudkin. 2021. “Do Commodity Price Shocks Cause Armed Conflict? A Meta-Analysis of Natural Experiments.” American Political Science Review 115 (2): 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000957

- Bohler-Muller, Narnia, Benjamin James Roberts, Jare Struwig, Steven Lawrence Gordon, Thobeka Radebe, and Peter Alexander. 2017. “Minding the Protest: Attitudes towards Different Forms of Protest Action in Contemporary South Africa.” South African Crime Quarterly 62 (62): 81–92. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2017/i62a3041

- Bond, Patrick. 2012. “South African People Power since the Mid-1980s: Two Steps Forward, One Back.” Third World Quarterly 33 (2): 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2012.666011

- Bonner, Philip, and Noor Nieftagodien. 2008. Alexandra: A History. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Booysen, Susan. 2007. “With the Ballot and the Brick: The Politics of Attaining Service Delivery.” Progress in Development Studies 7 (1): 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499340600700103

- Boyd-Swan, Casey, and Chris M. Herbst. 2012. “Pain at the Pump: Gasoline Prices and Subjective Well-Being.” Journal of Urban Economics 72 (2–3): 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2012.05.002

- Brancati, Dawn. 2014. “Explaining the Emergence of Pro-Democracy Protests Worldwide.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (11): 1503–1530. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512603

- Brinkman, Henk-Jan, and Cullen Hendrix. 2011. “Food Insecurity and Violent Conflict: Causes, Consequences, and Addressing the Challenges.” World Food Programme, Occasional Paper 24. https://ucanr.edu/blogs/food2025/blogfiles/14415.pdf.

- Brown, Julian. 2015. South Africa’s Insurgent Citizens: On Dissident and the Possibility of Politics. London: Zed Books.

- Bush, Ray. 2010. “Food Riots: Poverty, Power and Protest.” Journal of Agrarian Change 10 (1): 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2009.00253.x

- Bush, Ray, and Giuliano Martiniello. 2017. “Food Riots and Protest: Agrarian Modernization and Structural Crises.” World Development 91: 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.10.017

- Ceruti, Claire. 2013. “Contemporary Soweto: Dimensions of Stratification.” In Class in Soweto, edited by Peter Alexander, Claire Ceruti, Keke Motseke, Mosa Phadi and Kim Wale. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

- Chatterjee, Arop, Léo Czajka, and Amory Gethin. 2021. “Wealth Inequality in South Africa, 1993–2017.” The World Bank Economic Review 36 (1): 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhab012

- Chaudhry, Azam Amjad, and Chaudhry Theresa Thompson. 2008. “The Effects of Rising Food and Fuel Costs in Pakistan.” The Lahore Journal of Economics Special Edition: 117–138. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1510063

- Cohen, Marc J., and James L. Garrett. 2010. “The Food Price Crisis and Urban Food (in)Security.” Environment and Urbanization 22 (2): 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247810380375

- Curry, Dawne Y. 2012. Apartheid on a Black Isle: Removal and Resistance in Alexandra, South Africa. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Davies, Nick. 2015. “Marikana Massacre: The Untold Story of the Strike Leader Who Died for Workers’ Rights.” The Guardian, 19 May. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/19/marikana-massacre-untold-story-strike-leader-died-workers-rights.

- Dawson, Hanna J. 2014. “Patronage From Below: Political Unrest in an Informal Settlement in South Africa.” African Affairs 113 (453): 518–539. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adu056

- Dawson, Marcelle C., and Luke Sinwell. 2012. Contesting Transformation: Popular Resistance in Twenty-First Century South Africa. London: Pluto Press.

- De Juan, Alexander, and Eva Wegner. 2019. “Social Inequality, State-Centered Grievances, and Protest: Evidence from South Africa.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 63 (1): 31–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002717723136

- Deklerk, Aphiwe. 2021. “Government Condemns Violent Soweto Protests over Electricity.” Sowetian Live, June 10. https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2021-06-10-government-condemns-violent-soweto-protests-over-electricity/.

- Demarest, Leila. 2014. “Food Price Rise and Political Instability: Problematizing a Complex Relationship.” The European Journal of Development Research 27 (5): 650–671. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2014.52

- Desai, Ashwin. 2002. We Are the Poors: Community Struggles in Post-Apartheid South Africa. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- D’Souza, Anna, and Dean Jolliffe. 2012. “Rising Food Prices and Coping Strategies: Household-Level Evidence from Afghanistan.” Journal of Development Studies 48 (2): 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2011.635422

- De Winne, Jasmien, and Gert Peersman. 2021. “The Impact of Food Prices on Conflict Revisited.” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 39 (2): 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2019.1684301

- Dube, Oeindrila, and Juan F. Vargas. 2013. “Commodity Price Shocks and Civil Conflict: Evidence from Colombia.” The Review of Economic Studies 80 (4): 1384–1421. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdt009

- Duncan, Jane. 2016. Protest Nation: The Right to Protest in South Africa. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

- Eck, Kristine. 2011. “Survey Research in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies.” In Understanding Peace Research: Methods and Challenges, edited by Kristine Höglund and Magnus Öberg. New York: Routledge.

- FAO. 2021. “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World.” Accessed August 9, 2021. http://www.fao.org/3/cb4474en/cb4474en.pdf.

- FAO 2008. “An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Insecurity.” Accessed February 26, 2021. http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/al936e/al936e00.pdf.

- FAOSTAT. 2021. “Consumer Price Indices.” Accessed October 10, 21. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/CP.