ABSTRACT

This systematic literature review investigated school counselling needs in East and Southeast Asia based on 109 studies from 14 countries published since 2011. School counselling needs were categorised using an international taxonomy (Morshed & Carey, Citation2020, Development of a taxonomy of policy levers to promote high quality school-based counseling. Journal of School-Based Counseling Policy and Evaluation, 2(2), 95–101). We found similarities and differences between the countries and nine main needs characterising the region. These include the need for (1) up-to-date training, (2) country specificmodels of school counselling practices stating school counsellors’ roles and responsibilities, and (3) overcoming societal-level barriers such as stigma towards mental health. We recommend context-sensitive steps to policymakers seeking to improve school counselling services.

School counselling needs across East and Southeast Asia present certain similarities such as the need to provide school counsellors with up-to-date, relevant training, and the need for the school counselling profession to be guided by a specific school counselling model.

The Taxonomy of Policy Levers to Promote High Quality School-Based Counselling is a useful tool to identify specific levers to improve school counselling services.

New levers are suggested focusing on providing up-to-date training and regular supervision to school counsellors, aligning school counselling policy with the school environment and taking initiatives to overcome societal level barriers such as stigma towards mental health.

Highlights

Sustainable Development Goals:

Introduction and background

Students around the globe face challenges such as changing job markets leading to increased academic competition (Hohenshil et al., Citation2015), crises such as natural disasters or the COVID-19 pandemic (Loades et al., Citation2020), as well as emerging mental health disorders such as media addiction (Kok & Low, Citation2017). School counsellors can play an important role in the development and well-being of students in the face of these challenges. According to the American School Counsellor Association (ASCA), which provided the first definition and framework of school counselling services, school counsellors are accredited educators who improve student outcomes for all students by implementing a comprehensive school counselling programme to provide academic and career advice and promote social-emotional competencies (ASCA, Citation2012). A scoping review of the implementation of state-funded school counselling in 90 countries found that the school counselling profession is firmly established in 62 countries, is spreading worldwide, and is rapidly evolving (Harris, Citation2013). While there is increasing international evidence for the advantages of school counselling services (Harris, Citation2013, Citation2014), such as long-term academic and social-emotional benefits for students (Carey et al., Citation2017), few studies have specifically investigated school counselling needs in East and Southeast Asia.

School counselling in East and Southeast Asia

Although much research is available investigating school counselling in North America and Europe, little is known about how this profession is faring in societies in East and Southeast Asia, two regions representing most of the world’s children and youth, and where school counselling has recently found footing (Calabrese & Dorji, Citation2014). Past research comparing how school counselling is practiced around the world has revealed differences between Asia and the West. For instance, Kok (Citation2013) conducted an interview study with 11 school counsellors in Singapore and found that the school counsellor role is more multifaceted and flexible than in the West, and characterised by multiple approaches such as one-to-one counselling, group work, implementing a class curriculum, and consulting with parents and outside agencies in the community such as psychiatric services.

Research investigating school counselling services in East and Southeast Asia is further necessary because this region is experiencing rapid changes. These include rapid economic growth resulting in a fast-changing career landscape (such as the rise of information technology in what used to be agriculture-based societies), increasing youth unemployment, and more complex mental health challenges such as substance and media dependency (OECD, Citation2004; Patwa et al., Citation2019).

In addition, the available research on school counselling services in East and Southeast Asia predominately underlines the importance of further investigation. This includes research showing how school counselling services address the emotional needs of students in Singapore (Yeo & Lee, Citation2014), initiate positive changes in schools in Japan by for instance facilitating rewarding learning experiences for students (Chan et al., Citation2015), and even cost–benefit advantages of school counselling services in South Korea (Ministry of Education, Citation2010). To conclude, a review of school counselling in East and Southeast Asia is warranted to better understand this profession in this part of the world and to formulate recommendations that could increase its potential.

The present study

The present study aimed to conduct the first systematic literature review of school counselling services in East and Southeast Asia. More specifically, the present study sought to determine the most prevalent school counselling needs in both regions. To this end, a systematic literature review was carried out guided by the Taxonomy of Policy Levers to Promote High Quality School-Based Counselling (Aluede et al., Citation2020; Morshed & Carey, Citation2020) (henceforth, the Taxonomy of Policy Levers). Policies are understood as all forms of government orders that guide resources from the national (government) to local (school decision-maker) level and are specifically meant to strive to improve students’ well-being. Examples of school counselling policy include licensing requirements, mandating a student-to-school counsellor ratio, or implementing best practices around confidentiality (Carey et al., Citation2017). Perhaps the most widely recognised policy guide is the American School Counsellor Association (ASCA) school counselling model, which recommends, for instance, a specific student-to-school counsellor ratio of 250:1 (ASCA, Citation2012). School counselling policies can shape school counsellors’ working conditions, and policy analysis can help to determine compliance, namely fidelity of policy implementation, identify gaps, and evaluate the effectiveness of policies to ensure they are aligned with the needs of schools and students (Savitz-Romer et al., Citation2024; Savitz-Romer & Nicola, Citation2022). In response to the lack of international school counselling policy research and to support effective school counselling practice globally, the Taxonomy of Policy Levers (Aluede et al., Citation2020; Morshed & Carey, Citation2020) was developed, consisting of a comprehensive list of government policies, or levers, based on the analysis of international school counselling policy research. It consists of 25 policy levers grouped under eight policy foci: (A) school counsellors’ initial competence, (B) continuing competence, (C) effective school counselling practices, (D) planning and evaluation of school counselling, (E) distinct school counsellor roles, (F) hiring of school counsellors, (G) the continual improvement of the school counselling system, and (H) enhancing the capacity of educational leaders to support the implementation of high quality school-based counselling services. One example is lever C1, “Advocating for best practices” under focus C “Promoting the use of effective school counselling practices”.

Few studies investigating school counselling services have sought to translate empirical findings into policy levers. In one mixed-method study of how 56 school counsellors in Hong Kong perceive their roles and professional identity, it was found that school counsellors reported feeling unable to adequately address students’ issues because of a lack of role clarity, feeling marginalised within the school setting, not receiving the necessary support from school leaders, feeling targeted by stigma towards counselling and having few opportunities to improve their skills (Harrison et al., Citation2022). The authors of the study conclude that these results highlight the need to address seven levers of the Taxonomy of Policy Levers (i.e. A1, C1, C2, D1, E1, E2, and F6). As such, the Taxonomy of Policy Levers is a valuable tool for investigating school counselling policy needs and was, therefore, used to guide this review.

Methodology

Procedure

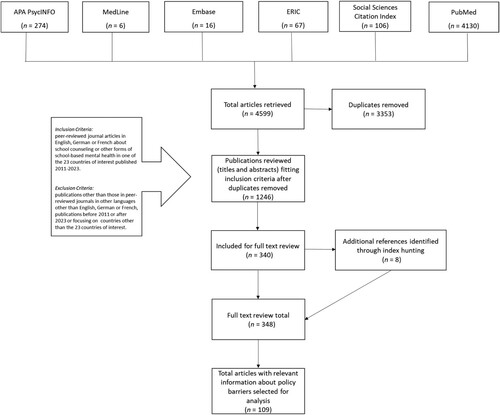

This systematic literature review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method (Moher et al., Citation2010). A literature search was carried out in June 2023. To cover a wide range of articles that were published recently, the review sought to investigate studies published in the last ten years. It was initially intended to investigate research from 2011 to 2021, but this was extended another two years to 2023 due to the emerging literature on school counselling services during the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, different key terms related to school counselling and other school-based mental health services were used in the search, including school psychology, in the last 12 years, namely between 2011 and 2023. Keyword searches were run in English, German, and French within the databases PsycInfo, MedLine, Embase, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), ProQuest Social Sciences, and PubMed. Furthermore, to cover a wide geographical area with little available research, the literature search included 23 countries and geographic regions in East and Southeast Asia from Pakistan to Japan, more specifically, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Tibet, and Vietnam. The exact search query can be found in Table A in the Appendices.

This search yielded 4599 records, of which 3353 duplicates were removed, resulting in 1246 records. These records were then uploaded to Rayyan QCRI, a free, systematic review web tool to screen and select references according to specific inclusion criteria (https://www.rayyan.ai/). Inclusion criteria included whether the study was published between 2011 and 2023, from or about one of the 23 countries and geographic regions of interest, whether it was published in English, French, or German, and whether it mentioned school counselling or other school-based mental health services such as “school-based counselling” or “school psychology” or other search terms related to school counselling (Table A, Appendices). For example, a study about students’ perceptions of school-based child and family counselling in Macao, China (Van Schalkwyk, Citation2014) was included in the review whereas a study about sexual health information provided by school nurses in Taiwan or a study about school guidance counselling services in Nigeria were not included. References with and without peer review were considered.

A trained research assistant (RA) independently reviewed a subsample of 100 references (29.41%) to assess agreement. The aim of involving a second coder to assess coding reliability was to ascertain which title and abstract were seen as relevant to the review by both raters. The RA was trained by the primary investigator (PI) [JL] to use Rayyan QCRI by being explained the inclusion and exclusion criteria central to the study and by practicing coding 50 references. Next, both the RA and PI went over these 50 references to check for agreements and disagreements, before the RA proceeded with the official coding task of a subsample of 100 references. When both raters’ ratings (i.e. whether to include or exclude studies from the full-text review) of this subsample were compared, an inter-rater agreement of 92% was found, which was deemed satisfactory. All disagreements were discussed and resolved.

Based upon the title and abstract screening, the PI included 340 references that met the inclusion criteria for full-text review, including eight additional references identified through index hunting. All were published in English, and no references were found in German or French. Next, the 348 studies were uploaded to MAXQDA, a software programme for qualitative data analysis, and the PI carried out a full-text review. MAXQDA was used as it is an easy-to-use software to efficiently code texts and visualise qualitative data using colours and counts. Moreover, it can be used by multiple users and has a function specifically to determine inter-coder reliability. MAXQDA was used to code all 109 studies, distinguish patterns, and draw conclusions about the coded exerts such as commonalities between the exerts that suggest specific themes. This allowed for a list of themes specific to the studies to be developed, including the number of times each study mentioned each theme and an easy-to-access repertoire of the excerpts relevant to each theme.

To assess coding reliability using the Taxonomy of Policy Levers (Aluede et al., Citation2020; Morshed & Carey, Citation2020), a trained RA independently reviewed a subsample of 15 (13.76%) studies. The RA was trained by the PI to use MAXQDA to code 15 studies specifically for the qualitative analysis central to the study by being shown the code book and three already coded studies. The RA then coded three practice studies themselves before going over these codes together with the PI to check for agreements and disagreements, namely which foci and levers were extracted by both raters. They then proceeded with the coding of 15 studies. In the end, the inter-rater agreement was 33.4%. This divergence was discussed in depth, during which it was concluded that the main reason for such differences was due to the PI’s in-depth familiarity of the international school counselling literature. All individual coding disagreements were then discussed and resolved so that, in the end, both raters agreed on the coding.

In the end, 109 studies were selected during the full-text review for data extraction as they were found to mention specific needs, which were in turn categorised using the Taxonomy of Policy Levers (Aluede et al., Citation2020; Morshed & Carey, Citation2020). The exact data extraction process of these 109 full-text studies is described below.

A flow chart of the search and reference selection processes is presented in .

Data extraction using the taxonomy of policy levers

The Taxonomy of Policy Levers (Aluede et al., Citation2020; Morshed & Carey, Citation2020) was used for the data extraction of all 109 articles. For the data extraction process, all full-text references were analysed for specific needs, which were categorised using the Taxonomy of Policy Levers. The process was deductive at first, namely all identified needs were coded according to the Taxonomy of Policy Levers. However, it was found that not all needs mentioned in the 109 full-text references could be categorised under a specific lever or foci of the Taxonomy of Policy Levers, so new ones were suggested, and an inductive approach was employed. Furthermore, some levers under specific foci were collapsed together as it was not possible to categorise each need under a specific lever.

The following changes were made to the Taxonomy of Policy Levers for the analysis. We found recurring mentions of the need for relevant training (stated in 54 references), the need for regular supervision (stated in 27 references), the need for specific guidelines on stakeholder collaboration (stated in 41 references), the need to train and hire more school counsellors (stated in 27 references), and the need to motivate and retain school counsellors (stated in 8 references). These themes, which were not in the original Taxonomy of Policy Levers, were added. More specifically, (1) a new lever “A4: Provide training relevant to current needs of students” was added to the focus “A. Assuring the initial competence of school-based counsellors”; (2) a new lever “B4: Provide regular supervision” was added to the focus “B. Assuring the continuing competence of school counsellors”; (3) a new lever “D2. Developing a model of stakeholder collaboration” was added to the focus “D. Ensuring that school counselling activities are planned organised, and evaluated well in schools”; (4) new levers “F9. Need to train and/or hire more school counsellors” and “F10. Motivation and retention” were added to the focus F.

In addition, 37 references discussed stigma around mental health as a significant barrier to students seeking school counselling services, and 26 references raised the issue of inconsistencies between the aim of school counselling services and the school environments they are meant to serve, indicating misalignment of school counselling policies. These issues were added as two new foci. More specifically, a new focus “I. Initiatives to overcome societal level barriers” with three levers “I1. Need to overcome stigma towards mental health and school counselling”, “I2. Need for more awareness of mental health and counselling such as through campaigns”, and “I3. Need to overcome cultural barriers such as inappropriateness of sharing issues with adults outside the family”, and a new focus “J. Policy alignment”. These were added as their own separate foci rather than new levers under any of the other foci as they were not deemed to be categorizable under any of the existing foci.

Conversely, some levers were collapsed together because it was not possible to clearly differentiate between them during analysis. Both levers under the focus “G. Ensuring that the country’s school counselling system continuously improves” were collapsed together and the focus “F1. Suggesting that schools have counsellors” were collapsed together with “F2. Mandating that schools have counsellors” and “F6. Funding school counselling positions in schools” was collapsed with “F7. Hiring school counsellors and placing them in schools” because the analysis did not allow to sufficiently differentiate between funding and hiring policies.

Table 1. Overview of 109 studies reviewed that included information about school counselling policy barriers and needs (n = number of studies).

Results

The 109 studies in the analysis originated from 14 of the 23 countries and geographic regions included in the literature search. These were Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Countries and geographic regions from which no eligible studies were found include Afghanistan, Cambodia, Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Thailand, and Tibet. The 109 studies kept for analysis consisted of various research methods, including general descriptions, survey studies, interview studies, programme implementation studies, reviews, and theses on school-based mental health staff such as school counsellors, school psychologists, school guidance and vocational counsellors, teacher counsellors, social workers, and clinical psychologists. An overview of the studies’ general characteristics can be found in .

Indonesia (n = 16; 14.7%) had the most references about their school counselling systems, followed by India (n = 14; 12.8%). Most (n = 83; 76.1%) of the references referred explicitly to school counselling services rather than other professions, such as school psychologists or teacher counsellors. Of the 109 references, 50 (45.9%) were peer-reviewed studies, 38 (34.9%) were qualitative studies, 27 (24.8%) were general descriptive country case studies of school counselling services in a specific country, and 26 (23.9%) were quantitative studies. The rest were books or book chapters (8; 7.3%), reviews (3; 2.8%) or theses (2; 1.8%). The most peer-reviewed studies (n = 7; 7.1%) were from or about Hong Kong, and the most studies that were not peer-reviewed were from or about Indonesia (n = 12; 12.1%). An analysis of findings by year was not feasible as there was an unequal and irregular distribution of references ranging from two (1.8%) publications (2011 and 2016) to 15 (13.8%) (2022).

The levers identified in each study and changes made to the Taxonomy of Policy Levers marked in bold can be found in . A list of all 109 references and their identified levers and foci can be found in Table B, and a table of needs identified in each country and geographic region in Table C of the Appendices.

Table 2. Taxonomy of Policy Levers (Aluede et al., Citation2020; Morshed & Carey, Citation2020). Additional levers and levers collapsed together indicated in bold (n = number of studies mentioning the foci or lever)

The most often mentioned levers and foci were (1) “A4: Provide training relevant to current needs of students” (n = 54; 49.5%), (2) “D1. Developing or adopting a model for school counselling practice” (n = 53; 48.6%), (3) “I. Initiatives to overcome societal level barriers” (n = 46; 42.2%), (4) “E2. Developing or adopting a role statement for school-based counsellors” (n = 45; 41.3%), (5) “D2. Developing a model of stakeholder collaboration” (n = 41; 37.6%), (6) “A1. Licensing/certifying school-based counsellors” (n = 35; 32.1%), (7) “A2. Accrediting school counsellor training programmes (n = 31; 28.4%)”, (8) “B4. Providing regular supervision” (n = 27; 24.7%), and (9) “J. Policy alignment” (n = 26; 23.9%).

These levers and foci are presented below along with examples from the 109 studies.

1. Providing relevant and up-to-date initial and continuous training

Fifty-four studies (49.5%) mentioned the need to provide training specific to students’ current needs, such as problematic media usage or substance abuse. This was not a specific lever in the original Taxonomy of Policy Levers, so it was added as “A4. Providing initial and regular training relevant to current needs of students”. Examples from the review results include:

There needs to be new changes brought in to address challenges like internet addiction […] and alcohol problems […] which is rising in India. With the increasing number of global concerns arising in India, the curriculum might need a thorough enhancement to be able to keep up with the rising demands (Thomas & Dey, Citation2020, p. 24)

Furthermore, this need was mentioned the most from or about India (n = 9; 8.3%), Malaysia (n = 8; 7.3%) and Indonesia (n = 7; 6.4%). Studies published from or about India mentioned mostly the need for training on stakeholder collaboration such as with teachers and parents:

The present study calls for the inclusion of further counsellor training in handling obstacles in the academic syllabus of school counsellors. This could help them in gaining adequate knowledge on the importance of inclusion of parents, ways to approach them, the process of inclusion, and managing the obstacles in the counsellor process (Vaishnavi & Kumar, Citation2018, p. 364).

2. Implementing a school counselling model

Fifty-three studies (48.6%) mentioned the need to develop and implement a school counselling model: “D1. Developing or adopting a model for school counselling practice”. This lever was in the original Taxonomy of Policy Levers and referred to developing a school counselling model and promoting its implementation through training and evaluation (Morshed & Carey, Citation2020). Examples from the review results include:

most schools in the region are either not using any model of counselling or importing and adapting a model such as the ASCA National Model. This is problematic because, without clear frameworks delineating their roles, counsellors may experience role confusion [Vietnam] (Harrison, Citation2022, p. 545).

Furthermore, this need was mentioned the most by research from or about India (n = 9; 8.3%), Malaysia (n = 6; 5.5%) and Vietnam (n = 6; 5.5%). More specifically, research from these countries expressed the need for a model of school counselling that is comprehensive and suited to the local context and culture:

However, in India, there are no standardised models or bodies that inform the practice of school counselling. Although currently there is a policy that suggests that all schools have school counselling, it does not articulate how they should function or how the school counselling programme needs to be implemented. Therefore there is an urgent need to clarify the roles and expectations from a school counsellor in India” [India] (Thomas et al., Citation2017, p. 315).

3. Initiatives to overcome societal-level barriers

Forty-six studies (42.2%) mentioned the need for initiatives to overcome societal-level barriers. This aspect was not a specific lever or focus on the original Taxonomy of Policy Levers, so it was included as an additional focus: “I. Initiatives to overcome societal level barriers”. This was, in turn, split into three different levers “I1. Need to overcome stigma towards mental health and school counselling”, “I2. Need for more awareness of mental health and counselling such as through campaigns” and “I3. Need to overcome cultural barriers such as inappropriateness of sharing issues with adults outside the family”. Examples from the review results include:

To counteract this conception, psycho-education to minimise such stigmatisation and to normalise help-seeking from school counsellors should commence as the students start their secondary education. Regardless of culture and age, stigmatisation appears to be a contributing factor towards the formation of negative attitude towards school counselling [Singapore] (Hafiz & Chong, Citation2023, p. 8).

The most often mentioned lever under this focus was “I1. Need to overcome stigma towards mental health and school counselling” which was mentioned the most by research from or about Malaysia (n = 7; 6.4%) and India (n = 6; 11%). These studies mentioned mostly the issue that counselling is perceived as only necessary for those with serious problems and the problematic cultural barrier in which issues are discussed only within the family and not with adults beyond the family circle:

Many Indian parents believe that in order to seek help from a professional such as a counsellor or a psychologist one must have severe mental health issues and such professionals are not to be approached for small problems” [India] (Akos et al., Citation2014, p. 173);

Shame and face-saving reactions within the patriarchal family structure result in the school students’ reluctance to disclose their personal problems to outsiders, for it might reflect negatively on the family system” [Malaysia] (Kok & Low, Citation2017, p. 282).

4. Clear roles

Forty-five studies (49.1%) mentioned the need to clearly define school counsellors’ roles which falls under the lever “E2. Developing or adopting a role statement for school-based counsellors”. Examples from the review results include:

In the absence of a specific job description, counsellors were sometimes required to fill in for duties that were not assigned to any other particular staff member such as monitoring detention and discipline” [Sri Lanka] (Jayawardena & Gamage, Citation2022, p. 29).

Furthermore, this need was mentioned the most by research from or about India (n = 7; 6.4%) resulting in the school counsellors being made to do work that shouldn’t be the responsibility of the school counsellor:

Studies conducted in India have highlighted several challenges that school counsellors face. There exists immense role confusion and misconceptions among stakeholders regarding a school counsellor’s role (Kakar & Oberoi, Citation2016; Thomas & Dey, Citation2020). The role confusion is evident as many administrators expect counsellors to be involved in non-counselling administrative tasks, such as liaison between the administration and teachers, handling parents’ concerns, invigilation duties, maintaining student records, acting as substitutes, and assisting in other routine tasks” [India] (Sadana & Kumar, Citation2023, p. 2).

5. Improved stakeholder collaboration

Forty-one studies (37.6%) mentioned the need to improve collaboration with school staff, families, outside agencies, and the community. This was not a specific lever in the original Taxonomy of Policy Levers, and so it was added as “D2. Developing a model of stakeholder collaboration”. Examples from the review results include:

All of the 82 counsellors acknowledged that, in order to provide effective school counselling services, collaboration among all the stakeholders from the educational and local community needs to improve. To enhance the provision of public school counselling services in Malaysia, the researchers propose a partnership model between the different stakeholders” [Malaysia] (Low et al., Citation2013, p. 195).

Furthermore, this need was mentioned the most by research from or about Singapore (n = 7; 6.4%), more specifically the need for a better planned collaboration model, often in order to improve stakeholder collaboration:

Therefore, for school counselling to be effective, a collaborative model among all parties the family, the teachers and the community will be needed. Schools need to establish some workflows so that a multi-disciplinary collaboration among all parties involved might be effective [Singapore] (Kok, Citation2013, p. 540).

6. Licensing and 7. Accrediting of school counsellor training

Thirty-five studies (32.1%) mentioned the need for licensing (“A1. Licensing/certifying school-based counsellors”) and 31 studies (28.4%) for accreditation (“A2. Accrediting school counsellor training programs”) of school counsellor training. Examples from the review results include:

Establishing a certification or licensure process in school psychology in Taiwan is also recommended, such as the development of a unified licensure examination at the national level by professional associations and legislators, to ensure that training and services are provided [Taiwan] (Fan et al., Citation2021, p. 8).

Furthermore, both needs were mentioned the most by research from or about India (A1, n = 8; 7.3%; and A2, n = 7;6.4%), more specifically expressing a lack of licencing and or accreditation:

without coherent and recognized programs, counselors are still struggling to establish their professional identity. With no accredited degree granting programs in school counseling currently being offered by any higher education institutions in India, school counseling licensing requirements do not exist [India] (Akos et al., Citation2014, p. 174).

8. Provide supervision

Twenty-seven (24.7%) studies mentioned the need for systemic supervision or at least some form of mentoring by a trained senior school counsellor. This was not a specific lever in the original Taxonomy of Policy Levers, so it was added as “B4. Provide regular supervision”. Examples from the review results include:

Counsellors feel isolated by nature of their training and work, and reported that supervision was able to reduce those feelings of isolation. […] They are also able to build networks of support across different schools. Supervision is essentially a source of support and help for them [Singapore] (Tan, Citation2019, p. 441).

Furthermore, this lever was mentioned the most by research from or about Hong Kong (n = 4; 3.7%) and South Korea (n = 4; 3.7%), mostly expressing that this important support is limited or non-existent:

They are generally managed by individuals with little experience in or understanding of counselling: They may not receive adequate professional development or supervision, another barrier to a strong professional identity (DeKruyf et al., Citation2013), and are unable to use their training and skills to good effect [Hong Kong] (Harrison, Citation2023, p. 144).

Environmental support can be provided through supervision that directs novice school counselling to be aware of the complex emotions that are being aroused during counselling” [South Korea] (Hong et al., Citation2023, p. 342).

9. Policy alignment

Twenty-six studies (23.9%) mentioned the need for school counselling policies to align with school policies, such as LGBTQI + rights, confidentiality, academic competitiveness, and discipline. That is why an additional focus, namely “J. Policy alignment”, is suggested. Examples from the review results include:

School counsellors reported that the management of cyberbullying frustrated them as there were no clear policies. Suppose the bullying definition also encompasses cyberbullying with policies on bullying adapted to include cyberbullying actions. In that case, school counsellors may be more empowered to manage and resolve such cases [Malaysia] (Chan et al., Citation2020, p. 9).

Furthermore, this focus was mentioned the most by research from or about India (n = 5; 4.6%):

There are various domains of child development, whereas to a large, extent policies have primarily focused on a child’s aca-demic and vocational development. While this is essential in the school context, if one subscribes to the holistic development of the child, then a broader focus from vocational counselling alone toward a more comprehensive and integrated program may be necessary [India] (Thomas et al., Citation2017, p. 324).

Other levers

Additional levers were added, namely “F9. Need to train and/or hire more school counsellors” (n = 27; 24.8%) and “F10. Motivation and retention” (n = 8; 7.3%). The suggested lever F9 refers to the expressed need for more school counsellors in general to help students with their issues. These include the need for more school counsellors specifically in schools in rural areas as opposed to schools in urban areas (Pham & Akos, Citation2020) or at specific school levels such as primary schools (Harris, Citation2013). The suggested lever F10 refers to issues of professional motivation and retention, namely making sure the school counselling profession is attractive enough to encourage students to pursue this career, such as by providing a competitive salary, and to avoid school counsellors leaving the profession because of low job satisfaction. All other foci and levers were mentioned in one to 15 of the 109 reviewed studies or not at all. The reason could be that the school counselling profession is still relatively new in East and Southeast Asia. Harris (Citation2014), in their report on school counselling worldwide, found evidence of the implementation of school counselling services, such as studies and government documents, available for China since 2002, Hong Kong since 2003, Indonesia since 2003, Japan since 2005, Malaysia since 2010, Singapore since 2003 and Vietnam since 2008 while no information was available for other countries in the region. As a result, more research and policy development is needed to address structural questions in detail, such as around funding, leadership, best practices, or continuous improvement of school counselling services through relicensing, monitoring, and evaluation.

Discussion

Using a systematic literature review, it was possible to categorise school counselling needs mentioned in 109 studies from 14 East and Southeast Asian countries and geographic regions into different policy foci and levers of the Taxonomy of Policy Levers (Aluede et al., Citation2020; Morshed & Carey, Citation2020). As a result, nine prevalent needs were identified including the need to provide up to date training that is licensed and/or accredited, the need to apply a model for school counselling practice with specific school counselling roles and specific stakeholder collaboration methods, the need to overcome stigma towards mental health and school counselling, the need for regular supervision, and the need for policy alignment.

The countries and geographic regions investigated in this analysis can be further categorised into three groups: (1) countries and geographic regions where school counselling has been considerably investigated and for which data are already available for specific school counselling needs: China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, Singapore and Philippines and Vietnam; (2) countries and geographic regions where literature on school counselling is emerging but for which little data are available on specific school counselling needs: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Japan, Sri Lanka, and Taiwan; (3) countries and geographic regions for which no research on school counselling could be identified in this review: Afghanistan, Cambodia, Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Thailand, and Tibet. This grouping can be useful for practitioners and researchers as it allows to determine which countries and geographic regions need to encourage initiatives to begin publishing research on school counselling services (group 3), which countries and geographic regions may benefit from increasing their initiatives to start providing practical implications (group 2), and, finally, which countries and geographic regions already have data available about school counselling needs which should be leveraged to address these needs and monitor their progression (group 1).

The results of this study can further be discussed in relation to the Taxonomy of Policy Levers to Promote High Quality School-Based Counselling (Aluede et al., Citation2020; Morshed & Carey, Citation2020). It shows on one hand the usefulness of the taxonomy for carrying out such a review to unearth specific needs as well as proposing some minor changes to it, including adding levers on the need for training and supervision and foci on the need to overcome stigma.

The findings of this investigation are comparable with findings from similar research. First, these findings provide the first step towards country comparisons of school counselling needs which could be consolidated by further research in which school counsellors from each country are directly asked about their attitudes towards the different levers of the Taxonomy of Policy Levers, allowing for a more direct comparison between countries and regions, such as was done with 56 school counsellors in Hong Kong by Harrison et al. (Citation2022). This study also builds on previous research on school counselling in general including the scoping review of the implementation of state-funded school counselling in 90 countries by Harris (Citation2013). More specifically the results of this study provide a different perspective on how to review school counselling services cross-nationally, namely investigating school counselling service needs, which provide information to practitioners and policymakers. To consolidate these findings in a way such as to inform practitioners and policymakers, we suggest a hypothetical roadmap of specific steps.

Roadmap toward context-sensitive school counselling models in East and Southeast Asia

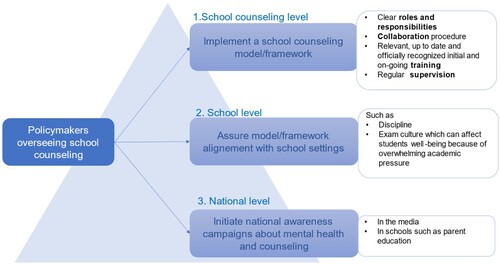

The results of this study suggest several steps policymakers in East and Southeast Asia looking to implement or improve school counselling services should consider. The following roadmap is a suggestion based on the most prevalent needs identified by the review and is open to discussion and feedback.

Based on the results of the review, as an immediate first step, policymakers must design and implement a school counselling model. The design of such a model must be informed by empirical evidence of the de facto roles and responsibilities of school counsellors in the respective context. Such crucial work is underway, for instance, in Bhutan (citation withheld for peer review) where a recent study found that school counsellors’ views differed from the views of teachers and principals concerning whether they should be responsible for administrative duties, indicating that school counsellors’ roles and responsibilities need to be more clearly defined and communicated. Such research provides an important evidence base for designing or refining context-sensitive school counselling models. Further, the school counselling model must define collaboration procedures with stakeholders, such as regular consultation meetings with school principals and procedures for making referrals to mental health service providers. This model should also specify the training school counsellors must receive, both initially and continuously, which should reflect students’ needs and be recognised, through licensure and/or accreditation, to guarantee the profession's effectiveness and credibility. This model should also guarantee the provision of systematic supervision and should undergo monitoring and regular reviews and be adapted according to changing needs, such as the increasing multicultural composition of classrooms (e.g. in South Korea; Lee & Yang, Citation2017).

As a second step, measures should be taken to assure policy alignment, namely that policies reflect the actual needs on the ground, such as marginalised and minoritized students’ rights or the school’s priorities placed on academic exams, and that these are implemented accordingly.

Finally, measures should be taken nationally to destigmatize mental health so that school counselling services are better accepted and students are encouraged to seek help, such as through media campaigns or organising regular school counselling information events with parents. A diagram of this roadmap is presented in .

It is further suggested that this roadmap can help researchers, practitioners and policymakers to identify which next steps to consider when looking to improve school counselling services in their specific country or geographic region. The review revealed, for instance, that school counselling services in India should consider further steps at each level of the roadmap. These include the need for up-to-date and relevant training, the need to implement a school counselling model, and the need for more clear roles and responsibilities at level 1, the need to align school counselling services with other school policies at level 2, and the need to overcome societal barriers about mental health and counselling at level 3. The review also revealed that school counselling services in Singapore should consider further steps at level 1 of the framework to improve stakeholder collaboration. School counselling in Malaysia should consider the need for up-to date and relevant training and the need to implement a school counselling model, both at level 1, and the need to overcome societal barriers to mental health services and counselling, at level 3.

Strengths and limitations

A notable strength of this study is its emphasis on 23 countries and geographic regions that are generally under-represented in school-based mental health research. It further used a broad definition of school counselling to include different definitions of school-based mental health services. This review can serve as a base from which future school counselling research can be undertaken. In addition, it can help policymakers to better understand and improve their school counselling needs.

However, there are several limitations. First, the scope of the study was restricted by the investigator’s language skills, so a limited range of literature was included, namely studies published in English, French, or German. Second, cultural aspects of the study may have been misrepresented due to a lack of knowledge and understanding of the local characteristics of the profession. Because of their background, the authors may have had specific prejudices they were unaware of, although they made every effort to be aware of their own biases and Westernised experiences. They tried not to overgeneralise the results but to recognise the differences between and within all countries and geographic regions included in the analysis. Third, this review did not include grey literature because of its broad geographic scope. Instead, a wide range of references were analysed, including studies that were not peer-reviewed. Thus, literature such as specific reports and briefs might have been missed that were not indexed in the electronic databases used in this study.

Future directions

The results of the present study provide suggestions on how to implement effective school counselling services. Future studies could investigate how needs differ between schools, countries, or regions, such as how provinces of a country differ in their implementation of a school counselling model.

Furthermore, the results of the present study provide a starting point for comparative research as it revealed, for instance, the significant need for relevant and up-to-date training, the need for a school counselling model and the need to overcome stigma in India and Malaysia, as well as the need for improved stakeholder collaboration in Singapore. This would be important as such differences may reflect the presence or absence of existing policies in these regions. For instance, India does not have a structured school counselling system including a specific model and role description (Choudhury & Choudhury, Citation2023) which was why this was found in the review to be a prevalent need in India. In contrast, this was not found to be a prevalent need in South Korea, where WEE (We + Education + Emotion) have been implemented, counselling offices where school counsellors offer mental health services for children and adolescents (Lee & Yang, Citation2017). The WEE project oversees Korea’s school counselling services by monitoring services and offering training to school counsellors seeking to develop their skills and is funded by the Ministry of Education.

Another question that should be addressed in future research is the position, or “embeddedness” (Harrison, Citation2019, p. 480) of the school counsellor within the school, namely whether they should be central, well integrated, and active within the school system, such as employing teacher-counsellors, or whether they should be located more on the periphery, maintaining a certain distance from other school staff. While the latter option may seem important for maintaining confidentiality, school counsellors positioned on the fringes of the school system run the risk of them being seen as outsiders and experiencing feelings of isolation (Van Schalkwyk, Citation2014). This question is often raised in studies investigating the “Whole-School Approach”, an idea of a collaborative approach to school counselling involving the participation of teachers, school management, and other members of the community but which is overseen by the school counsellor (Aluede et al., Citation2007).

Finally, similar reviews to the one in the present study should be carried out in other regions of the world, such as the African or European continent, to see how these results compare worldwide and to further inform global school counselling research.

Conclusions

Policies are about translating “should” into reality (Carey et al., Citation2017). They should reflect local values directed towards child and youth mental health and direct funding and other resources towards areas of need to uphold these values (Young & Lambie, Citation2007). This systematic literature review represents an inaugural effort to understand school counselling needs in a part of the world that is not well-represented in the literature, namely in East and Southeast Asia. Aided by the Taxonomy of Policy Levers to Promote High Quality School-Based Counselling (Aluede et al., Citation2020; Morshed & Carey, Citation2020), the results of the review revealed the nine most prevalent school counselling needs, which could help researchers, policymakers, and school counsellors to better understand and improve this profession as well as provide impetus for further research on the subject. First steps should be taken to meet school counsellors needs by (1) implementing a school counselling model including specific roles and responsibilities, collaboration procedures, systematic supervision requirements, and a designated, accredited training course allowing school counsellors to be prepared on the most up-to-date information about issues affecting students, (2) by aligning this model with school policies, and (3) by designating initiatives to overcome societal-level barriers towards mental health services. Considering these steps is crucial as school counsellors in East and Southeast Asia will likely have an increasingly important role in the future.

Ethics statement

In accordance with the British Journal of Guidance & Counselling’s policy and ethical obligations as a researcher, all authors report no financial, institutional or other competing interests that may affect the research reported in the enclosed paper.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (106 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [SH], upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Julie Larran

Julie Larran, M.Sc. is a Ph.D. student at the Free University of Berlin since 2019. She has studied in France, England and Germany and has worked in the USA. Her research interests lie in school based mental health but also mental health and well-being policies, cross-cultural psychology, migration and autism. Her Ph.D. work investigates school counselling services in the Kingdom of Bhutan from an ecological systems theory perspective.

Sascha Hein

Sascha Hein, Ph.D., is a Professor in the Department of Education and Psychology at the Free University of Berlin, Germany. He received his Ph.D. in Educational Science from Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany. He completed a three-year post-doctoral training at the Yale Child Study Centre before his position as faculty in the Measurement, Quantitative Methods, and Learning Sciences programme at the University of Houston. Over the past decade, his research has focused on early childhood development and education in humanitarian contexts. He is also leading research on the education and mental health of individuals from marginalised and minoritized communities, such as refugee families and individuals involved in the juvenile justice system.

References

- * = the reference was a study found and analyzed in the literature review process.

- *Akos, P., Jain, S., & Gurjar, S. (2014). School counseling in India. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 4(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.18401/2014.4.2.8

- Aluede, O., Brady, B., Jin, Y. Y., Morshed, M. M., & Carey, J. C. (2020). Development of the taxonomy of policy levers to promote high quality school-based counseling: An initial test of its utility and comprehensiveness. Journal of School-Based Counseling Policy and Evaluation, 2(2), 102–112. https://doi.org/10.25774/a23t-2245

- Aluede, O., Imonikhe, J., & Afen-Akpaida, J. (2007). Towards a conceptual basis for understanding developmental guidance and counselling model. Education, 128(2), 189–201.

- ASCA. (2012). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs. https://schoolcounselor.org/About-School-Counseling/ASCA-National-Model-for-School-Counseling-Programs

- Calabrese, J. D., & Dorji, C. (2014). Traditional and modern understandings of mental illness in Bhutan: Preserving the benefits of each to support Gross National Happiness. Journal of Bhutan Studies, 30 (Summer 2014), 1–29.

- Carey, J. C., Harris, B., Lee, S. M., & Aluede, O. (2017). International handbook for policy research on school-based counseling. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58179-8

- *Chan, M. C. R., Kurihara, S., Yukiko, E., & Yamasaki, A. (2015). Training of school guidance and counselling workers in Japan: Concerns and challenge s for future development. Journal of Learning Science, 8, 67–79. https://doi.org/10.15027/36764

- *Chan, N. N., Ahrumugam, P., Scheithauer, H., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., & Ooi, P. B. (2020). A hermeneutic phenomenological study of students' and school counsellors' “lived experiences” of cyberbullying and bullying. Computers & Education, 146, 103755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103755

- *Chen, K. S., & Kok, J. K. (2017). Barriers to seeking school counselling: Malaysian Chinese school students’ perspectives. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 27(2), 222–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2015.21

- *Choudhury, T., & Choudhury, R. (2023). Digital experiences of children and adolescents in India: New challenges for school counsellors. Psychology in the Schools, 60(4), 1094–1106. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22821

- DeKruyf, L., Auger, R. W., & Trice-Black, S. (2013). The role of school counselors in meeting students’ mental health needs: Examining issues of professional identity. Professional School Counseling, 16(5). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001600502

- *Dem, K., & Busch, R. (2018). Complexities of a Bhutanese school counselling community: A critical narrative insight. Australian Community Psychologist, 29(1), 54–71.

- *Dizon, M. A. A. D., & Chavez, M. L. L. (2022). Circumstances to contribution: A phenomenological study on school counseling site supervision in the Philippines. Philippine Social Science Journal, 5(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.52006/main.v5i2.497

- *Fan, C. H., Juang, Y. T., Hsing, C. P., Yang, N. J., & Wu, I. C. (2021). The development of school psychology in Taiwan: Status Quo and future directions. Contemporary School Psychology, 25(3), 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-020-00324-7

- *Hafiz, M., & Chong, W. H. (2023). An elicitation study to identify students’ salient beliefs towards school counselling. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 33(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2022.6

- Harris, B. (2013). Scoping report: International school-based counselling. https://www.bacp.co.uk/media/2050/counselling-minded-international-school-based-counsellingharris.pdf

- Harris, B. (2014). Journal of counselling in the Asia-pacific region: Locating school counseling in the Asian-pacific region in a global context. Brief reflections on a scoping review of school counseling internationally. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 4, 217–245. https://doi.org/10.18401/2014.4.2.11

- *Harrison, M. G. (2019). Relationship in context: Processes in school-based counselling in Hong Kong. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19(4), 474–483. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12234

- *Harrison, M. G. (2022). The professional identity of school counsellors in East and Southeast Asia. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(3), 543–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12546

- *Harrison, M. G. (2023). School counselling in Hong Kong: A profession in need of an identity. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 45(1), 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-022-09498-6

- *Harrison, M. G., Wai, F., & Cheung, J. K. (2022). The experiences of school counsellors in Hong Kong: implications for policy innovation. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 50(6), 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2022.2164758

- Hohenshil, T. H., Amundson, N. E., & Niles, S. G. (2015). Counseling around the world: An international handbook. John Wiley & Sons.

- *Hong, S., Lee, T., Ko, H., Kang, J., Jang, G. E., & Lee, S. M. (2023). Novice school counselors’ countertransference management on emotional exhaustion: The role of daily emotional processes. Journal of Counseling & Development, 101(3), 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12475

- *Jayawardena, H. K. H., & Gamage, G. P. (2022). Exploring challenges in mental health service provisions for school-going adolescents in Sri Lanka. School Psychology International, 43(1), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343211043062

- Jorm, A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 67(3), 231. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025957

- Kagstrom, A., Juríková, L., Pešout, O., Šimsa, B., & Winkler, P. (2023). Applying a theory of change approach to develop and pilot a universal mental health literacy curriculum for adolescents. Mental Health Science, 1(2), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/mhs2.19

- *Kakar, V., & Oberoi, N. (2016). Counseling in Indian schools: Checkmating the past. International Journal of Education and Management Studies, 6(3), 357–364.

- Kim, B. S., Ng, G. F., & Ahn, A. J. (2009). Client adherence to Asian cultural values, common factors in counseling, and session outcome with Asian American clients at a university counseling center. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00560.x

- *Kok, J. K. (2013). The role of the school counsellor in the Singapore secondary school system. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 41(5), 530–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2013.773286

- *Kok, J. K., & Low, S. K. (2017). Proposing a collaborative approach for school counseling. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 5(4), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2016.1234986

- *Lee, S. M., & Yang, N. (2017). School-based counseling policy, policy research, and implications: Findings from South Korea. International Handbook for Policy Research on School-Based Counseling, 305–314.

- Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

- Low, S. K., Kok, J. K., & Lee, M. N. (2013). A holistic approach to school-based counselling and guidance services in Malaysia. School Psychology International, 34(2), 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034312453398

- Ministry of Education. (2010). Research report on job and outcome analyses of school counselor.

- Miserentino, J., & Hannon, M. D. (2022). Supervision in schools: A developmental approach. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 16(1), 3.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery, 8(5), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

- Morshed, M. M., & Carey, J. (2020). Development of a taxonomy of policy levers to promote high quality school-based counseling. Journal of School-Based Counseling Policy and Evaluation, 2(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.25774/9scb-j720

- OECD. (2004). Career guidance and public policy: Bridging the gap.

- *Patwa, S. S., Peverly, S. T., Maykel, C., & Kapoor, V. (2019). Roles for school psychologists in the challenging Indian education landscape. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 7(2), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2019.1570886

- *Pham, A. K., & Akos, P. (2020). Professional school counseling in Vietnam public schools. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 10(2), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.18401/2020.10.2.6

- *Sadana, A., & Kumar, A. (2023). Exploring novice Indian school counsellors’ experiences collaborating with teachers and administrators. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 33(2), 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2021.13

- Savitz-Romer, M., & Nicola, T. P. (2022). An ecological examination of school counseling equity. The Urban Review, 54(2), 207–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-021-00618-x

- Savitz-Romer, M., Nicola, T. P., Rowan-Kenyon, H. T., & Carroll, S. (2024). A landscape analysis of state-level school counseling policy: Perspectives from state officials. Educational Policy, 38(2), 421–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048231163803

- *Tan, S. Y. (2019). Clinical group supervision experiences of Singapore school counsellors. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 47(4), 432–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1371275

- *Thomas, E., & Dey, A. M. (2020). Role of school counselors and the factors that affect their practice in India. Journal of School-Based Counseling Policy and Evaluation, 2(1), 22–28.

- *Thomas, E., George, T. S., & Jain, S. (2017). Public policy, policy research, and school counseling in India. International Handbook for Policy Research on School-Based Counseling, 315–326.

- *Vaishnavi, J., & Kumar, A. (2018). Parental involvement in school counseling services: Challenges and experience of counselor. Psychological Studies, 63(4), 359–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-018-0463-9

- *Van Schalkwyk, G. J. (2014). Perceptions of school-based child and family counseling in Macao (SAR). Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 4(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.18401/2014.4.2.6

- *Wong, L. P., & Yuen, M. (2019). Career guidance and counseling in secondary schools in Hong Kong: A historical overview. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.18401/2019.9.1.1

- Yeo, L. S., & Lee, B.-O. (2014). School-based counselling in Singapore. Journal of Asian Pacific Counselling, 4(2), 69–79.

- *Yi, H. J., Shin, Y.-J., Min, Y., Jeong, J., Jung, J., & Kang, Y. (2023). Perception and experience of sexual and gender minority Korean youth in school counseling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 45(2), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-022-09490-0

- Young, M. E., & Lambie, G. W. (2007). Wellness in school and mental health systems: Organizational influences. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 46(1), 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00028.x