ABSTRACT

Within higher education research, the topic of choosing has mainly concerned young peoples’ choices of whether or not to enter higher education and their choice of study programme. However, a study programme is often not a fixed package. Nevertheless, choices within higher education has received comparably little attention. This study unpacks second-year students’ experiences of choosing, and it explores how they navigate these choices. Drawing on empirical material from ethnographic fieldwork at three bachelor programmes, we found that students experience both opportunities and constraints in navigating higher education choices. Inspired by Ingold (2015; 2016) we suggest a theoretical perspective on choice as wayfaring. We found, that navigating through higher education contains both ambiguities and challenges for students, who learn as they go along, discover new paths and thus change direction as they move through the landscape of higher education. We argue that making choices in this sense is an integral part of being a student and an inherent part of what it means to study.

Introduction

I think it’s a general thing at university, this about that all of a sudden you have to make some choices yourself […] Now you are kind of the tailor, stitching your own study together (Anna, second-year chemistry student)

The decision concerning what to do after the bachelor’s degree has become particularly relevant in Europe following the Bologna process and the 3 + 2 structure (EHEA Citation2018). In some countries, like the UK, students already had to choose what to do after bachelor completion, but in other countries, like Denmark and Germany, the structure introduced a new decision point (Ulriksen Citation2023).

This paper adds to the understanding of second-year students’ experiences and to the literature on students’ choices after entering university. We explore students’ experiences of choosing during their bachelor programmes, and how students navigate between individual priorities and the institutional framework.

Higher education choices

A vast amount of research has examined young peoples’ educational choices, drawing on different disciplinary and regional traditions, but mostly focusing on the choice of undergraduate programmes (Nielsen Citation2021) or majors (Pinxten et al. Citation2015). Some research has looked for general traits in the choice process, but according to Bergerson (Citation2009) research increasingly studies particular groups or aspects of choice, with research on equity being particularly prominent. Drawing on Bourdieu, qualitative studies have pointed out that students’ possession of economic and cultural capital affects their decision process and eventual choice (Bathmaker et al. Citation2016; Reay, David, and Ball Citation2005), just as social capital plays a role (Greenbank Citation2009).

It is a consistent finding that family background, gender (Adamuti-Trache and Andres Citation2008), geography (Mangan et al. Citation2010), teachers and schools (Bathmaker et al. Citation2016) plays a profound role when choosing whether to enter university, and choosing which university. Friends and peers can serve as positive inspirations, but may also discourage particular study paths (O’Sullivan, Robson, and Winters Citation2019).

Building on social-psychological perspectives, a line of enquiry highlights that young people’s choice of education is not simply a question of what to become, but whom to become (Bøe et al. Citation2011). This has led to an increased focus on choice as a process of identity negotiation (Holmegaard, Ulriksen, and Madsen Citation2014), including a weighing of interests (Vulperhorst, van der Rijst, and Akkerman Citation2020) and future horizons (Harrison Citation2018). Processes that continue, even after students have entered university (Holmegaard, Madsen, and Ulriksen Citation2014) .

A substantial amount of research has studied the transition into higher education (Coertjens et al. Citation2017), especially into first year. A particular focus has been on students developing learner autonomy, understood as students’ ability to ‘determine their own learning goals, to manage aspects of their own learning, and to engage in a very personal way with the learning process’ (Scott et al. Citation2015, 946). Although a few studies consider choice of courses as a way of exercising autonomy (Clifford Citation1999), the studies mainly focus on the day-to-day study activities (Macaskill and Taylor Citation2010).

Another line of enquiry focusses on students’ non-completion. Reviews have found that there is no single cause or factor leading to a student leaving their study. Qvortrup and Lykkegaard (Citation2022) point at factors related to the study environment and highlight the social, academic and teaching systems as particularly important. Studies of non-completion predominantly focus on the first year, however students continue reflecting about their initial choice and may choose to leave at later points (Willcoxson, Cotter, and Joy Citation2011).

Still, second year has been sparsely researched (Milsom et al. Citation2015). Milsom et al. (Citation2015) write that second-year students seem to adopt a more performance-oriented approach, just as the workload and the increased complexity surprise them. Yorke (Citation2015) describes what has been called the ‘second-year blues’ in the UK and the ‘sophomore slump’ in the US, referring to a drop in performance and satisfaction from the first to second year, but Whittle (Citation2018) calls for further research exploring the extent of the slump in the UK. In all events, students may experience challenging epistemic transitions from first to second year (Conana, Solomons, and Marshall Citation2022). Thus, there are reasons to consider choice during second year.

Educational choices can be seen as personal, but also embedded in social relations. They are, as Bergerson (Citation2009) points out, ‘neither linear nor uniform for all students’ (114). This paper adds to this research by focusing on choice in higher education rather than the choice of higher education.

We do so, by examining the way students deal with choices during their bachelor studies. The paper builds on empirical work, but our purpose is to present a new theoretical perspective on students’ choices in order to expand the way we perceive and conceptualise educational choices more broadly. Although we are convinced that social background, ethnicity and gender are important for the opportunities, resources and limitations students have for engaging in these choice processes, we have not explored them in this particular study.

The present study

This study is part of a larger research project exploring students’ reflections and concerns regarding what to do after completing a bachelor’s degree. However, during the empirical work it became clear that during the bachelor’s degree, students had to make numerous other choices. We therefore studied these choices as well, and how the students related to them.

Based on the empirical material, we propose a theorisation of choice as wayfaring. It offers an analytical gaze that adds to the perception of choice as a process of negotiation and as identity work by directing attention to the entanglement, non-linearity and movement inherent in these choices.

In his seminal work, Ingold (Citation2015; Citation2016) argues that life can be understood through the way we inhabit the world, and that we do so through our journeying through it. Inherent in our way of being in the world is thus movement. Ingold describes this as wayfaring. He argues that in modernity a fragmentation has occurred, that has transformed our understanding of, among other things, places and travel. Modernity has, inter alia, been characterised by structural differentiation and cultural rationalisation (Rosa Citation2013). Processes are divided into manageable units for optimisation, stressing that the end goal counts rather than the process of getting there (Rosa Citation2013).

In a higher-education context, examples of this are the emphasis on employability as the purpose of studying (Henderson, Stevenson, and Bathmaker Citation2019) and the focus on increasing students’ pace through their studies (Ulriksen and Nejrup Citation2020).

Following Ingold, in modernity the dominant approach has shifted from perceiving life as wayfaring towards seeing life as an assembly of different points, what Ingold describes as transportation. The distinction between these two kinds of movement, is how they relate to the journey itself and the destinations reached. What characterises transportation is that the sole purpose is to reach the destination. Upon arrival, the traveller explores the place before continuing towards the next destination. This kind of movement is one that presupposes an overview of the map and a pre-planned itinerary. For the wayfarer, the way, rather than the destination, constitutes the purpose of the movement. There may be stops along the way, but to the wayfarer these destinations are not endpoints. Where transportation has a beginning and an end, the path of the wayfarer takes form along the way as it is walked (Ingold Citation2015, 133).

We use the concepts of transportation and wayfaring to examine students’ experiences of choosing in higher education and to contrast these with the institutional perspective on choice. The concept opens up our understanding by directing our attention to choice as movement over time, through a landscape with a more or less pre-defined content and thus itinerary.

Research design

We followed second-year students from three different bachelor programmes at a Danish research-intensive university (chemistry, computer science and natural resources). The programmes differed in size with 87 students at chemistry, 90 at natural resources and 242 students at computer science by the time of enrolment.

By the time of the fieldwork, the organisation of the three programmes had several similarities. The first year at each programme consisted of mandatory courses. By the end of the first year, the students should choose a specialisation within their programme. Chemistry students, for instance, could choose between medical chemistry, general chemistry, or chemistry teaching. Within each specialisation there would be specific mandatory courses.

In addition to the mandatory courses, the second and third year included a combination of restricted elective and free elective courses. Restricted electives are courses where students should choose one or two courses from a list of specified courses, all within their disciplinary field. For example, they would have to choose two courses from a list of ten. Free electives are courses where students could choose any course they liked including courses beyond the discipline of their bachelor programme e.g. from other departments, faculties or universities.

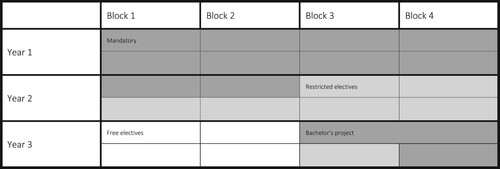

At this university, the academic year was divided into four blocks of nine weeks each. The box-diagram () shows the general principle of the structure of the three programmes with three years of four blocks with typically two courses in each block. The distribution of mandatory, restricted electives and electives are indicated with dark grey, light grey and white, respectively. The four elective courses in block 1 and 2 at third year offer the students the opportunity to study a semester abroad, the so-called mobility window.

This structure left students with a range of choices they needed to combine in meaningful ways: which specialisation to take, which restricted and free elective courses to take, whether to study abroad and which topic to choose for the bachelor project.

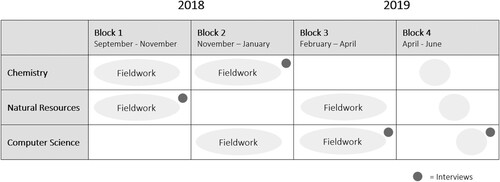

The first author carried out ethnographic fieldwork (O’Reilly Citation2012) with the three cohorts of students throughout their second year. This longitudinal design allowed us to follow the students’ choice processes as these developed and changed over time. At second year, the initial transition process had been completed, but the students were still in a process of finding out which aspects of the discipline they wished to pursue through elective courses and specialisations and possibly further into their master’s programme.

During the fieldwork, the first author attended two courses at each programme, participating in lectures, classes, and lab exercises alongside the students. She furthermore engaged in extracurricular activities such as information meetings, excursions and social events. Through the fieldwork, she learned about the norms and expectations at the programmes, just as her participation gave rise to informal conversations with students about their programmes and possible choices. The intention was not to map all the possible choices and paths, but rather to provide insights into the complexities of the students’ lived experiences as these unfolded in practice (O’Reilly Citation2012) ().

The first author further invited eight students from each programme to participate in open-ended, semi-structured interviews (O’Reilly Citation2012). The eight students were selected based on variation in gender, their chosen specialisations and preliminary insights from the fieldwork concerning their choice processes. In order to learn in-depth about students’ different choice perspectives, our selection of participants was information oriented, focussing on variation (Flyvbjerg Citation2006). The interviews addressed the various choices the students should make, their experiences of being second-year students, their perceptions of the field of study and future possibilities. See Nielsen (Citation2021) for an in-depth account of the methodology, including considerations on researcher positionality.

The empirical material consists of the transcribed interviews and ethnographic fieldnotes, which were coded in a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) in three stages. First to detect overall themes and then to narrow down and refine these themes and sub-themes.

During the fieldwork, it stood out that students’ choices indeed took shape as ongoing processes, but also that these were weaved together in various and entangled ways. In our analysis, we initially coded for the different kinds of choices that the second-year students encountered. However, the different choices interweaved, making it impossible to order them into separate categories. The empirical material thus called for an analytical perspective allowing us to unfold the process of students’ choices without reducing them to single events. The empirical material thus serves as a starting point for our theoretical development (Flyvbjerg Citation2006; O’Reilly Citation2012) on choice processes in higher education.

Analysis

A crosscutting theme in the data was the interwoven nature of students’ choices on the practical level of choosing courses and on a larger scale of fitting courses, specialisation and future master’s programme into a study plan the students could see themselves in.

An example was a conversation between the student Martin and the first author. While waiting for a social event to begin, they talked about possible master’s programmes, specialisations and elective courses. Martin explained that it could be quite complicated. He missed some tool helping students to get an overview of the relation between the different choices:

There should be a huge flowchart, he said, where you can then make a cross, okay I choose this specialization, and then I will have these options. Then I choose this, and then the next ones. He showed me with his hands how the flowchart would open up new parts once one choice was made. Martin explains that he found out what to choose by moving backwards. He knew where he wanted to end up, and then he could kind of move backwards and find out what he should choose (Fieldnote).

In the following, we analyse the students’ experiences of choosing during higher education.

The course puzzle

Several times the students used the metaphor of a puzzle for choosing in higher education. The metaphor referred to the practical challenge of finding and deciding on elective courses, and it related to the way the courses were organised.

At the Faculty of Science, the week was divided into so-called schedule groups and each course was allocated a particular group. Courses in schedule group A would, e.g. have classes on Tuesday morning and all Thursday, while courses in schedule group B would have classes Monday morning, Tuesday afternoon and Friday morning. When choosing elective courses, the students therefore both needed to find out in which of the four blocks each course was offered and to make sure that the courses were not placed in the same schedule group.

For the free elective courses, a common experience among the students was feeling quite overwhelmed by the many possibilities. Carly, for example, explained that it felt impossible to get an overall view of the different courses, because the possibilities seemed endless.

For the restricted electives, many students experienced the opposite. Students would get a list of courses from which they should choose two or three. Students said this gave them an initial impression of being free to choose, followed by the realisation that many of the courses would be located in the same schedule group, making the actual choice quite limited. Students thus had to fit several pieces together concerning schedule groups and blocks. In an interview, Carly talked about choosing courses for block four:

I think it’s quite difficult to put together which courses I want to follow in block four. Because you have to sit and think ‘well okay, if I then … I could also take that course in block two. Then, if there are two other courses that I would really like to have in block two, then I probably shouldn’t plan to have this course in block two’. It is like a complete puzzle to figure out (Carly, chemistry).

The metaphor of the puzzle relates to the programme consisting of separate courses that the students needed to combine. The puzzle arises as students try to assemble these separate pieces into a picture, making the pieces fit together. Looking at the box-diagram () it seems like an easy task to make the puzzle. It gives the impression that there is a structure to follow, and that students only need to take specific courses in a specific order and at specific times and then fill out the empty boxes with a specialisation and electives.

There seems to be a discrepancy between the students’ experiences of choices as entangled and the neat idea of a study programme depicted in the box-diagram. This difference between an ordered plan and the experienced entanglement can be explored through the difference between what Tim Ingold (Citation2016) describes as a network and a meshwork.

A network is the connection of points with straight lines from point to point, joining these up to a connected map. In this analogy, the ordered diagram of a study programme constitutes such a network. The students’ experience of choices as interwoven, on the other hand, constitutes a meshwork. This, Ingold describes as the entanglement of lines, woven through movement. Where the network is constituted through its joints, the meshwork is constituted through the entanglement.

Perceiving students’ choices as a meshwork would be to say, that the students’ study paths are not formed by the collection of separate choices of courses. Rather they are formed by what the students do to weave them into a study path, how they try to connect them and how they experience the courses as entangled. Thus, the picture that the pieces of the puzzle will make up does not exist beforehand. It emerges in the students’ moving through the programme. This, however, can be a frustrating experience if the students assume that there is a picture beforehand.

Constructing the right picture

Each choice offered students different possibilities and closed off others. Each course had to fit into the plan practically (blocks and schedule groups), but they also had to fit together as a study plan that allowed students to move in a desired direction.

Students who, e.g. wished to study a semester abroad had to start planning early on, because the application process was long. Anna, for example, had to decide this already by the end of her first year. This had forced her to think more about the entire programme and think through which courses she had to choose before going abroad, which to take during the stay and which when coming back. She described this as a big decision: ‘Then it was not just a question of thinking one block ahead. Then it was a question of thinking 18 months ahead’. This was particularly difficult, because it forced her to make choices that had implications for her entire study and what she wanted to do with her degree, at a point when she was unsure about it: ‘I didn’t know that, and I still don’t know a hundred percent’.

Some students had clear ideas about what they wished, but our longitudinal design revealed that the vast majority of the students we followed, changed ideas along the way as they learned about the discipline, new courses, other students’ experiences, possibilities at the departments and future careers. Some students also changed because their initial idea was made difficult by the structure and not recognised as legitimate within the culture (Nielsen and Madsen Citation2023).

We can understand these changes and difficulties with laying a larger puzzle by looking at students as wayfarers, walking through the landscape, discovering it as they move along. The picture of the puzzle is constructed while moving through the programme and cannot be detached from the student. When Anna found it challenging trying to lay the larger puzzle at the end of first year, it was because it required her to define the endpoint, that is, to change her journey into transportation.

Similarly, the box-diagram and the formal organisation of the programmes presumes that the students should engage in transportation. However, the students become wayfarers instead, both because of the lack of transparency and because they discover new things along the way – intriguing things, things they wish to avoid, different possible futures.

When finding out which pieces to choose and how to construct a desirable, larger picture, the students drew on the resources available to them, particularly fellow students, senior students, and university staff. Following Ingold (Citation2015), these resources can be seen as trails and paths in the landscape that the wayfarer can follow if paying close attention. These paths were passed on as oral narratives, but how available such narratives were to the students depended on the culture of the programmes and the access to other students or staff.

At the study programmes of computer science and chemistry, there were strong communities across year-groups, and bachelor and master’s students were located in the same campus area. For students in natural resources there were no designated master’s programme, and students would therefore spread out to a number of different programmes when finishing their bachelor degree. This made it more difficult to find previous students’ paths through the bachelor’s programme, and the natural resource students would have to make the paths on their own.

For students in chemistry and computer science it could be challenging if they wished to follow less travelled paths. Emma wished to find a way to combine her interests in computer science with her interests in the humanities and social sciences. She wished to use the skills she learned to solve socio-scientific issues and maybe work in the public sector. This desired path differed from her peers in computer science, and she could not find it reflected in the ways the teachers talked about the discipline. Emma used the metaphor of treading paths, and described hers as crooked with no linear ways to follow:

I can’t really find any footprints on the path. I have to create it – kind of walk through the field and build a path along the way. But I just hope that it leads to something nice, because then it’s a good thing that you did it after all (Emma, computer science).

The not so fixed points

The box-diagram could not serve as a map students could follow. This showed in some students’ concerns about making the right choices in order to be admitted into specific master’s programmes. Danish students completing a bachelor’s degree have a statutory right to enrol at particular master’s programmes that are defined as the natural continuation of the bachelor programme. However, some master’s programmes did not reserve access to students from designated bachelor programmes, and if these programmes had a restricted intake, there would be a selection of applicants.

This was the case for the master’s programme in climate change, that some of the natural resource students hoped to enter. During the annual information day about master’s programmes at the university, the first author and some of the students attended the presentation of this programme. At the presentation, they were told that students needed to hold a relevant bachelor’s degree to apply, and would be evaluated based on the number of ‘climate change related study elements’ they had completed. The following conversation with two students shows their efforts to navigate and make their choices fit together.

We join the line for free coffee while we talk about the presentation. A discussion about the so-called ‘climate change related study elements’ soon arises. Tania is considering applying for the programme and wonders how they assess courses relatedness. Would it be good for her, to choose elective courses with ‘climate change’ in the title, or how should she make sure that the courses are considered ‘related’? As we get our coffees and move away, Tania quickly decides to return to the auditorium, hoping that someone will still be there to answer questions. Upon returning, she explains that they do not decide based on the name of the course (Fieldnote).

The many choices in higher education allow students some freedom in designing a personalised study path, but these also imply that students can find and combine pieces for the picture they wish to construct, and that they can navigate hazy rules that the structure presents as clear. For doing that, they need to draw on experiences of other students and make their own paths.

Navigating the landscape

For making the puzzle, the students had to be able to navigate the formal rules and regulations, but also understand that some things were negotiable and changeable. Most of the students were not initially aware of this, but found out as they tried to arrange the pieces of their study plans, like Nora:

Last block Nora only took one course because her schedule was too crammed. She says that it’s something she didn’t consider until second year. Oh well, you can do half time. Why rush through the study? Why is that frowned upon? If one would like to do half time and take time to immerse oneself and digest (Fieldnote).

When changing pace and using the opportunities, the students also refrained from the transportation indicated by the route of the box-diagram. They changed the route through the landscape, but at the same time, the landscape of the study programmes was entangled with other parts of the students’ lives. The students navigated different landscapes at the same time, transforming them into a desired kinds of paths.

Discussion

Choice

Our study explored bachelor students’ choices during higher education. The students were presented with maps of their study programmes in the form of box-diagrams that presented an image of transparency, overview and progression, and the assumption that students can and will merely follow the fixed paths. The diagrams lure us into assuming that students can navigate towards a pre-set destination without changing direction and that choices embedded in the structure are straightforward to make.

Our empirical findings do not corroborate these assumptions. Instead, we found that the students experienced the choices they were to make as entangled and ambiguous. On the one hand the choices presented the students with opportunities offering the possibility of combining and pursuing particular interests. On the other, the choices were opaque. It was difficult for the students to get an overview of the possibilities, and peers became important resources in finding information about different ways of navigating the study requirements. Further, when seeking information, some students received vague answers, that they had to interpret themselves, as Tania experienced. Choices were also opaque in a temporal perspective, as choices made by the end of the first year could have bearing on later opportunities, but it was not always clear how the many small choices during the blocks would affect opportunities in the larger picture.

Furthermore, the puzzle of finding out which courses could be taken at the same time and which were blocked because of the schedule groups, limited what appeared to be open opportunities for choosing. In parallel to Abrahams (Citation2018), some bachelor students were prevented from pursuing their interests because of the structure of the programme and what was considered legitimate in the culture at the programme (Nielsen and Madsen Citation2023).

Similar to studies of choice when entering university, we found that friends, peers and older students were important resources, particularly when the students wished to do other things than what they were expected to do and where they needed to find the cracks in the system. However, peers could also limit what was considered appropriate.

Family background was less visible in the empirical material. Still, there is reason to believe that the students’ background has a profound impact on their navigating the study programmes, and on how well they can make use of the cracks (Bathmaker et al. Citation2016), but it calls for further research.

Wayfaring

Higher-education policies have a strong focus on completion, employability and on getting students through their studies in the fastest possible way (Nielsen and Sarauw Citation2017). There is an emphasis on education as transportation, on getting students from one point to the next (i.e. passing an exam) as efficient as possible, rather than on the way to get there (i.e. the learning process). This emphasis on time is particularly strong in the Danish context (Brooks et al. Citation2021), but similar challenges are also arising in other countries (Henderson, Stevenson, and Bathmaker Citation2019).

Seeing studying as transportation is questionable in relation to the idea of students as learners who should engage with the disciplines and through that, also develop independence, critical sense, and curiosity. Wayfaring is a kind of movement that is more coherent with the idea of studying because it means exploring the landscape with an awareness of the paths and footprints made by other wanderers.

Thus: perceiving studying as wayfaring means emphasising the learning process, the inquiry and exploration, and the development in being a student. Perceiving it as transportation means focusing on getting to the endpoint along the predefined route map as soon as possible without detours, and thus a focus on achievement rather than learning.

Choices and wayfaring

Choices and changes in higher education are part of being a student. If we ignore this, we overlook essential parts of what makes educational choices meaningful and challenging for students. Students are compelled to make choices because of the study structures, e.g. the electives and restrictive electives. At the same time, students make choices because they have ideas and interests they wish to pursue, and these may change because students learn and develop as they move through the higher education landscape. Therefore, students have to be autonomous route planners as well as learners.

The assumption inherent in the idea of studying as transportation implies that students will not have doubts concerning their path or choices as they move through the study programme, or that they will put aside such doubts to pursue the original route plan. This assumption is questionable. Looking at studying as wayfaring makes it clear why choice of higher education must be perceived as an ongoing process and why students’ transitions into university should not be seen as something with an endpoint (Gale and Parker Citation2014).

Hence, while the students’ experiences of choosing as difficult and entangled have been studied before, we argue that the entanglement is partly due to lack of transparency, partly to the students wishing to change pace to pursue interests and immerse themselves (Nielsen and Ulriksen Citation2021). Therefore, we do not argue for disentanglement, but for seeing choosing as wayfaring, which requires other kinds of support.

The response should not be to set the students free of all requirements and framing. Rather, one could say that we should allow students to be wayfarers, let them move and explore and learn and change along the way. We should omit the idea of studying as transportation. At the same time, the institutions should ensure that there are footprints and paths for the students to follow, that there is access to peers and teachers with experience and support. The students wished to be wayfarers, but they were worried about getting lost along the way. This is not least important, because the students will enter the study programmes with different access to resources to help them interpret and navigate the landscape. If we do not consider this, wayfaring will become for the privileged, while the less privileged can be transported through a route of exams.

Conclusion

Studying in higher education involves numerous choices concerning both the here and now of studying and the larger picture of fitting a specialisation, courses and a potential master’s programme together. In making these choices, students experience opportunities as well as constraints. Contrary to the clear and neat structure of study programmes presented in study plans, students experience these choices as entangled, confusing and ambiguous.

Inspired by Ingold (Citation2015; Citation2016), we suggest that these experiences can be analysed using the concepts of transportation and wayfaring. Where higher-education studies is often presented as having clear paths to be followed in a pre-defined manner like in transportation, we found that students construct their itinerary as they move through higher education, drawing on new experiences and the resources made available to them. They move through higher education as wayfarers through a landscape, learning as they go along, discovering new paths. Choices are integrated parts of being a student, and indeed of the very idea of what it means to study.

Our findings call for further research on students’ choices in higher education, and how different students have different opportunities, resources and limitations when navigating the landscapes of higher-education choices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahams, Jessie. 2018. “Option Blocks That Block Options: Exploring Inequalities in GCSE and A Level Options in England.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39 (8): 1143–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1483821.

- Adamuti-Trache, Maria, and Lesley Andres. 2008. “Embarking on and Persisting in Scientific Fields of Study: Cultural Capital, Gender, and Curriculum along the Science Pipeline.” International Journal of Science Education 30 (12): 1557–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690701324208.

- Bathmaker, Ann-Marie, Nicola Ingram, Jessica Abrahams, Tony Hoare, Richard Waller, and Harriet Bradley. 2016. Higher Education, Social Class and Social Mobility: The Degree Generation. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bergerson, Amy. 2009. “College Choice and Access to College: Moving Policy, Research, and Practice to the 21st Century ” ASHE Higher Education Report 35 (4): 1–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/aehe.3504.

- Bøe, Maria Vetleseter, Ellen Karoline Henriksen, Terry Lyons, and Camilla Schreiner. 2011. “Participation in Science and Technology: Young People’s Achievement-related Choices in Late-modern Societies.” Studies in Science Education 47 (1): 37–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2011.549621.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brooks, Rachel, Jessie Abrahams, Achala Gupta, Sazana Jayadeva, and Predrag Lažetić. 2021. “Higher Education Timescapes: Temporal Understandings of Students and Learning.” Sociology 55 (5): 995–1014. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038521996979.

- Clifford, Valerie A. 1999. “The Development of Autonomous Learners in a University Setting.” Higher Education Research & Development 18 (1): 115–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180109.

- Coertjens, Liesje, Taiga Brahm, Caroline Trautwein, and Sari Lindblom-Ylänne. 2017. “‘Students’ Transition into Higher Education from an International Perspective.” Higher Education 73 (3): 357–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0092-y.

- Conana, Honjiswa, Deon Solomons, and Delia Marshall. 2022. “Supporting the Transition from First to Second-Year Mathematics Using Legitimation Code Theory.” In Enhancing Science Education, edited by Margaret Blackie, Hanelie Adendorff, and Marnel Mouton, 206–223. London: Routledge.

- EHEA. 2018. “Ministerial Conference Bologna 1999, European Higher Education Area and Bologna Process”. 2018. http://www.ehea.info/cid100210/ministerial-conference-bologna-1999.html.

- Flyvbjerg, Bent. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Gale, Trevor, and Stephen Parker. 2014. “Navigating Change: A Typology of Student Transition in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (5): 734–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.721351.

- Greenbank, Paul. 2009. “Re-Evaluating the Role of Social Capital in the Career Decision-Making Behaviour of Working-Class Students.” Research in Post-Compulsory Education 14 (2): 157–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596740902921463.

- Harrison, Neil. 2018. “Using the Lens of “Possible Selves” to Explore Access to Higher Education: A New Conceptual Model for Practice, Policy, and Research.” Social Sciences 7 (10): 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100209.

- Henderson, Holly, Jacqueline Stevenson, and Ann-Marie Bathmaker. 2019. Possible Selves and Higher Education. New Interdisciplinary Insights. First ed. New York: Routledge.

- Holmegaard, Henriette Tolstrup, Lene Møller Madsen, and Lars Ulriksen. 2014. “A journey of negotiation and belonging: understanding students’ transitions to science and engineering in higher education.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 9 (3): 755–786. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-013-9542-3.

- Holmegaard, Henriette Tolstrup, Lars M. Ulriksen, and Lene Møller Madsen. 2014b. “The Process of Choosing What to Study: A Longitudinal Study of Upper Secondary Students’ Identity Work When Choosing Higher Education.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 58 (1): 21–40.

- Ingold, Tim. 2015. “The Life of Lines, January, 1–172. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315727240.

- Ingold, Tim. 2016. Lines: A Brief History. London: Routledge.

- Macaskill, Ann, and Elissa Taylor. 2010. “The Development of a Brief Measure of Learner Autonomy in University Students.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (3): 351–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903502703.

- Mangan, Jean, Amanda Hughes, Peter Davies, and Kim Slack. 2010. “Fair Access, Achievement and Geography: Explaining the Association between Social Class and Students’ Choice of University.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (3): 335–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903131610.

- Milsom, Clare, Martyn Stewart, Mantz Yorke, and Elena Zautseva. 2015. Stepping up to the Second Year at University. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315735771-10.

- Nielsen, Katia Bill. 2021. Science Students’ Choices in Higher Education: The Construction of Desirable and Legitimate Paths and Futures. Doctoral thesis. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen.

- Nielsen, Katia Bill, and Lene Møller Madsen. 2023. “Choosing (Not) to Be a Chemistry Teacher: Students’ Negotiations of Science Identities at a Research-Intensive University.” European Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041231157919.

- Nielsen, Gritt, and Laura Louise Sarauw. 2017. “How the European Bologna Process Is Influencing Students’ Time of Study.” In Death of the Public University? Uncertain Futures for Higher Education in the Knowledge Economy, edited by Chris Shore and Susan Wright, 17. New York: Berghahn Books, Incorporated.

- Nielsen, Katia Bill, and Lars Ulriksen. 2021. “Following Rhythms and Changing Pace–Students’ Strategies in Relation to Time in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 0 (0): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1940926.

- O’Reilly, Karen. 2012. Ethnographic Methods. Abingdon: Routledge.

- O’Sullivan, K., J. Robson, and N. Winters. 2019. ““I Feel like I Have a Disadvantage”: How Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Students Make the Decision to Study at a Prestigious University.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (9): 1676–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1460591.

- Pinxten, Maarten, Bieke De Fraine, Wim Van Den Noortgate, Jan Van Damme, Tinneke Boonen, and Gudrun Vanlaar. 2015. ““I Choose so I Am”: A Logistic Analysis of Major Selection in University and Successful Completion of the First Year.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (10): 1919–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.914904.

- Qvortrup, Ane, and Eva Lykkegaard. 2022. “Study Environment Factors Associated with Retention in Higher Education.” Higher Education Pedagogies 7 (1): 37–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2022.2072361.

- Reay, Diane, Miriam E. David, and Stephen J. Ball. 2005. Degrees of Choice: Class, Race, Gender and Higher Education. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books.

- Rosa, Hartmut. 2013. Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Scott, G. W., J. Furnell, C. M. Murphy, and R. Goulder. 2015. “Teacher and Student Perceptions of the Development of Learner Autonomy; a Case Study in the Biological Sciences.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (6): 945–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.842216.

- Tobbell, Jane, and Victoria L. O’Donnell. 2013. “Transition to Postgraduate Study: Postgraduate Ecological Systems and Identity.” Cambridge Journal of Education 43 (1): 123–38.

- Ulriksen, Lars. 2023. “Students’ Choices and Paths in the Bologna Degree Structure: An Introduction to the Special Issue.” European Educational Research Journal 22 (2): 135–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041211022201.

- Ulriksen, Lars, and Christoffer Nejrup. 2020. “Balancing Time – University Students’ Study Practices and Policy Perceptions of Time.” Sociological Research Online 26(1): 166–184 https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780420957036.

- Vulperhorst, Jonne Pieter, Roeland Matthijs van der Rijst, and Sanne Floor Akkerman. 2020. “Dynamics in Higher Education Choice: Weighing One’s Multiple Interests in Light of Available Programmes.” Higher Education 79: 1001–1021https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00452-x.

- Whittle, Sue R. 2018. “The Second-Year Slump – Now You See It, Now You Don’t: Using DREEM-S to Monitor Changes in Student Perception of Their Educational Environment.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 42 (1): 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2016.1206854.

- Willcoxson, Lesley, Julie Cotter, and Sally Joy. 2011. “Beyond the First-year Experience: The Impact on Attrition of Student Experiences throughout Undergraduate Degree Studies in Six Diverse Universities.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (3): 331–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903581533.

- Yorke, Mantz.. 2015. “Why study the second year?.” In Stepping up to the Second Year at University, edited by Clare Milsom, Martyn Stewart, Mantz Yorke, and Elena Zautseva. Abingdon: Routledge.