Abstract

Over the last decade, 35mm slide libraries that were used to support art history teaching in higher education in Europe and North America have been widely dismantled and dispersed. This article examines the cultural values that have been illuminated by debates about their decline and disposal, and the contexts and practices for their afterlife. Drawing on auto-ethnographic research, interviews with former slide librarians and surviving slide library material, the article pays special attention to one case study, formerly held at the University of Brighton, UK, to trace the slide library’s establishment and demise, examine the cultural labour of its production and maintenance, and evaluate its particularities and idiosyncrasies. Through this, the article outlines the values and meanings that were established and contested during the slide library’s working life and its 2011 dismantling, and considers how these have been repositioned in the intervening years. The slide library’s devaluation contrasts sharply with slides’ recent revaluation in scholarly interests in photographic materialities and media archaeologies, in the retro marketplace and in contemporary art practice. Together, these reflections and frameworks provide fresh perspectives on dismantled slide libraries and their remains.

In 2010, at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, nominees for the lucrative £30,000 annual Deutsche Börse Photography Prize included the artist Zoe Leonard.Footnote1 Specifically, Leonard was nominated for her 1998–2009 photographic series Analogue, which plots, via 412 colour prints displayed in rectangular grids, local independent ‘mom and pop’ shop fronts in Manhattan’s Lower East Side in Leonard’s home city of New York. Charting a disappearing street culture overpowered by big money and chain stores, as well as a photographic process threatened by digital technologies, Analogue was shot with a Rolleiflex camera. It captured taken-for-granted visual forms and materials at a moment of critical social and cultural change.Footnote2 Across her many decades of artistic practice, Leonard has created imaginative work with and about vernacular image cultures, from tourist postcards to snapshot archives. Her projects frequently use large-scale bodies of ephemeral visual material to explore singularity and multiplicity, sameness and difference, loss and change.

Also in 2010, fifty miles away, the University of Brighton was consulting its staff on what to do with its analogue slide library, comprising some 650,000 individual items, assembled to support teaching in art and design history. Both the collection and its small team of slide librarians and assistants had served what was originally called Complementary Studies in the institution since its inception.Footnote3 Leonard’s works, reproduced in the form of slides, were included in the University of Brighton slide library as part of its section marked ‘Photography’. When the slide library was dismantled in 2011, I took the entire photography section, among others, comprising approximately twenty thousand slides. For a decade since, these 35mm slides, still mounted in their plastic sleeves, have been stuffed, out of order, into two filing cabinets in my office. There may not seem much connection between a high-profile New York artist, the subject of a 2018 Whitney Museum retrospective exhibition and the 2020 winner of a Guggenheim prize, and the humble and unwanted slides of a provincial British educational institution. Leonard’s culturally celebrated photography and the culturally devalued 35mm pedagogic slide library, however, have a surprising amount in common and, I argue, along with the work of other contemporary practitioners whose work scrutinises visual image cultures, offer a productive point of departure for thinking about cultural values in image systems.

Cultural values – by which I mean, at base, what cultural products are wanted and unwanted – can sometimes be hard to articulate as the choices that inform these decisions often remain implicit. Anthropologist David Graeber has observed that cultural values move beyond individual desires; they are, rather, ‘the criteria by which people judge which desires they consider legitimate and worthwhile and which they do not’.Footnote4 Cultural values are not necessarily transferable to economic value, although that which is highly praised culturally may also be that which is highly prized financially, especially in the art world. Cultural values underpin hierarchical categories of taste, even as these are highly mobile and subject to a range of historic and geographical contingencies, as many eminent scholars who have examined the borders between the cherished and the despised, and between treasure and trash, have extensively noted.Footnote5 Visual culture not only materialises these values but offers systems for evaluating how they operate in visual media.

Artistic practice that makes visual culture its subject matter offers particularly pertinent ways of thinking through image values, especially when it visualises the overlooked. I have previously argued that contemporary artists’ use of slide libraries as a medium in the last decade – a new phenomenon that is a direct by-product of widespread deaccessioning in art historical departments across Europe and North America – can offer creative ways of thinking about image systems and scales.Footnote6 The artists, for example, who dump disordered slides en masse on gallery floors – such as Philipp Goldbach – or make icons of individual slides picked out of institutional dustbins – such as Annie MacDonell – or photograph the apparatus and structures through which slides were once organised and projected – as Susan Dobson does – can help us to see the distinctive forms of a visual culture that was once taken for granted as the dominant disciplinary media for apprehending art in academic lectures.

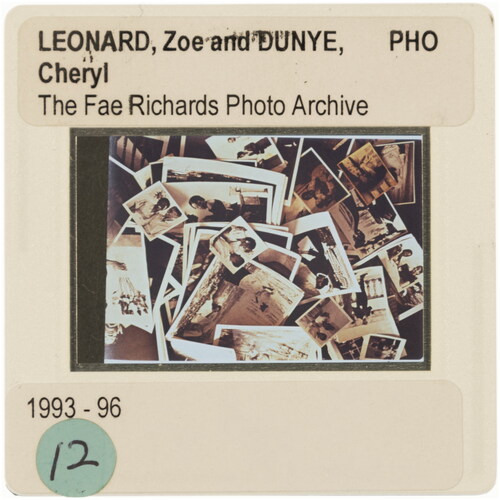

Although Leonard is not among the artists who has made work directly using 35mm pedagogic slides, her artistic attention to visual systems of value provides a means for thinking through attitudes to the marginal and the ephemeral in subject and in form more broadly. Whether examining cultural absences in relation to sexuality and ethnicity – for example, in the construction of a photographic archive for fictional black lesbian film star Fae Richards – or showing the complex cultural meanings inscribed in the seemingly banal, such as for thousand views of Niagara Falls in the form of used tourist postcards for You See I Am Here After All, she considers, in her own words, ‘how history is ordered and who gets the last word—what gets saved, what gets collected, how it gets presented, what disappears, and what gets lost in that process’.Footnote7 While Leonard is rightly celebrated for paying attention to, as art historian Huey Copeland has put it, ‘hegemonic modes of seeing and our ways of narrating them’,Footnote8 the materials she engages with, and the outcomes she produces, are closely related to other visual materials and labour practices that are culturally denigrated or occluded. As such, Leonard’s artistic practice provides a pertinent reflection on the contradictory values that are embodied in visual systems, and on a local level, these are relations in which her work is implicated. As her analogue work was venerated in one location, its reproduction was disposed of in another.

In this article, I examine the decline, disposal and afterlife of slide libraries in Europe and the USA, with particular reference to one large-scale case study at the University of Brighton on the south coast of England. Drawing on my own auto-ethnographic experience, interviews with former Brighton slide librarians, sector-wide debates and analysis of surviving slide library material, I trace one slide library’s establishment and demise, examine the cultural labour of its production and maintenance, and evaluate its particularities and idiosyncrasies. Through this, I consider the cultural values and meanings that were established and contested during the slide library’s working life and its 2011 dismantling, and how these have been subsequently repositioned in the intervening years. The slide library’s devaluation, at the point of its deaccession, contrasts sharply with slides’ recent revaluation in three locations: scholarly interests in photographic materialities and media archaeologies; the retro marketplace; and contemporary art practice. Together, these closer and wider reflections provide new materialist perspectives on dismantled slide libraries and their remains, as peopled, situated and tangible traces of past places, times and pedagogic structures.

The University of Brighton Slide Library: Foundation and Maintenance

The discipline of art history has long depended on photographs for its illustrative material, and the didactic slideshow as a core accompaniment to lecture instruction dates to the nineteenth century.Footnote9 Throughout the different phases of the institution’s history – as Brighton School of Art when established in 1859, redesignated as Brighton Polytechnic in 1970 and, finally, since 1992 as University of Brighton – slides have served art teaching.Footnote10 The dismantled library of 35mm transparencies that is the focus for this article has a range of institutional antecedents but its specific origin can be traced to the 1970s, when the collection was developed and cared for by staff from the library Learning Resources alongside Complementary Studies staff who then delivered history and theory teaching for students on practical degree courses in art, design and architecture; and, since the 1980s, for history of art and design degrees in their own right. Latterly the collection was developed and managed by professional librarians, such as Monica Brewis. Brewis was employed by the University of Brighton from 1981 to 2012; she focused on slide library management from the early 1990s, alongside other subject specialist staff, such as Slide Library Assistant Belinda Greenhalgh, a trained painter and art teacher.

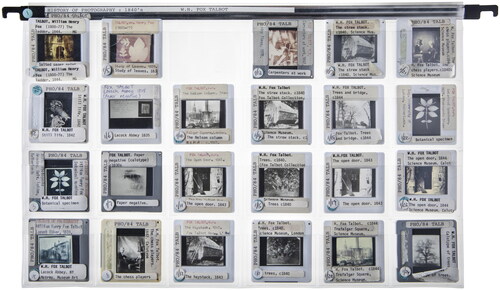

In interviews conducted in 2013 and 2018, Brewis and Greenhalgh provided detailed summaries of how the slide library was created and maintained.Footnote11 This included the production of images on the library premises, using a large-scale and high-specification Leica camera designed for scientific imaging, mounted on a copy stand. This camera was used to photograph images of artworks, usually from monographic art publications, although sometimes local artists and craftspeople loaned their own images from which copies were made. Films were sent away to specialist laboratories for processing into 35mm glass slides, which were then remounted, labelled and filed according to the library’s house style for cataloguing and storage. Additional slides were sometimes bought in from gallery exhibitions or from national art institutions who provided specific sets for sale. The choices about the subjects for the collection were made mostly by the slide librarians, but academics also requested specific materials according to their research and teaching interests as well as their knowledge of contemporary exhibitions and emerging trends, sometimes bringing in images from their travels. Academic staff, mostly art and design historians, used the slides to illustrate lectures, while students borrowed slides to support their assessed audiovisual presentations. The loan service was busy – in a typical day in 1977, for example, more than four hundred slides were loaned – and the slide library expanded annually, with a peak in the first decade of the twenty-first century, when it grew – bolstered by other donated slide collections – from 160,000 slides in 2001 to an estimated 650,000 in 2009.Footnote12

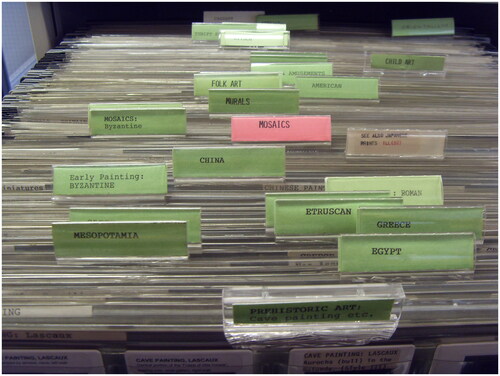

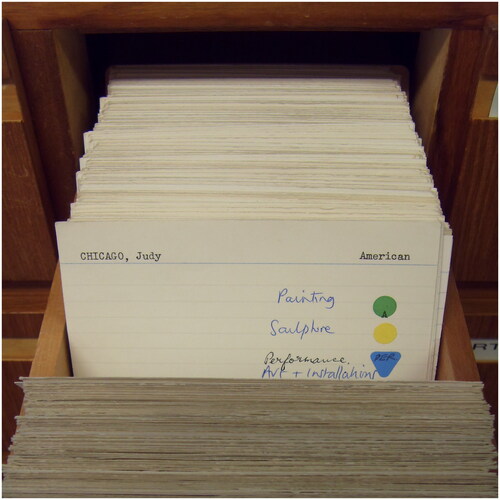

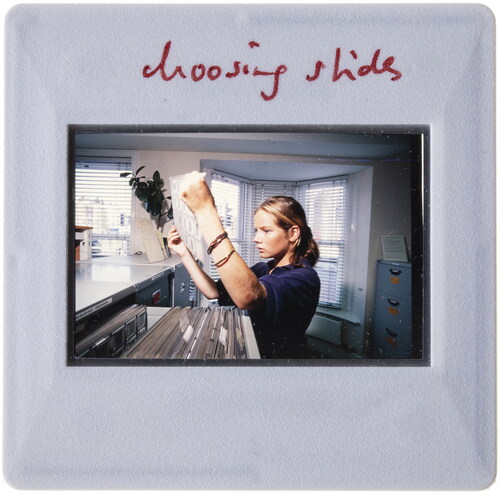

As well as producing new material, slide library staff maintained the collection. This involved cleaning, repairing and replacing dirty or damaged slides; creating labels to include artist names, media, dates and record numbers; and the major daily task of returning loaned slides to their correct plastic hanging sleeves and filing cabinet locations (). Library staff also designed and revised the slide classification schemes. There was no single set schema for how slide libraries should be organised, so Brighton librarians devised their own tiered model of organising slides first by medium, then by country and then by period, each demarcated by shaped and coloured stickers and an index card search system that corresponded with filing cabinet drawers (). These categories were redesigned over time to meet changing social and cultural expectations, including the political revision of national boundaries, at the dissolution of the Soviet Union for example, and changing practices in segregating collections, such as ‘women artists’ and ‘black artists’, once separate identity sections that were later integrated into the whole (). As Brewis and Greenhalgh recalled, there was ‘quite a lot of crossing out’ over the decades as needs and preferences shifted. Slide library staff, too, oversaw the consultation process that ultimately dismantled the collection. The last slide was produced by the library in 2009; the consultation about the slides’ future began in the same year.

Figure 1. History of Photography slide sheet with 35mm slides, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Richard Boll, 2019.

The University of Brighton Slide Library: Decline and Fall

At the start of Brewis’s professional life, slide libraries were convenient and functional. A 1980 book, for example, produced as part of the series ‘Outlines of Modern Librarianship’ by Hilary Evans, indicated the value of the slide to professionals in information management:

The 35mm transparency is the librarian’s dream come true – a small, lightweight item, easily protected despite its inherent vulnerability, and easily captioned, especially if stored in one of the many ready-made wallets or files now available. Enormous numbers can be stored in a tiny corner of a room, requiring no specialised furniture – a standard A4 filing cabinet will meet the requirement perfectly. All that is needed is to devise a classification and numbering system, provide a lightbox to enable viewers to see what they are looking at, and you are in business.Footnote13

Over 2009–11, Brighton academics – including myself – made impassioned arguments for retaining the slide library. Those in favour of keeping the slides contended that they contained the historiography of the discipline, but Information Services responded that they were not an archive; that the material is itself a historical system of visual technology, to which Information Services countered that they were not a museum; and, finally, that the photographs were, in several cases, unique. This final point had some purchase. Brewis proposed a small pilot project whereby academics would identify unique slide material which might be transferred to form the basis for a local digital collection, but no one came forward for the task. Many felt an emotional investment in the sources that they had helped build and which they had utilised daily for many years, but not enough to take on additional work. The academics surveyed in 2009, it transpired, were increasingly using the expanding online image databases to source their lecture images or were covertly making their own photographs with digital cameras to populate slideshows in PowerPoint.

The writing was on the wall. By the start of the twenty-first century, slide film processors were increasingly hard to find, and the manufacturers of slide projection equipment, not least Kodak, were going out of business. Parts could not be replaced, and in 2009 Brighton’s copy stand camera was given away. Only 611 slides were issued in the whole of 2010; by 2011, a mere 255. During 2010, the collection was moved out of its once-central library position. In the summer of 2011, it was disposed of as a whole. The original licensing agreements meant that, technically, the material could only be used for teaching at the University of Brighton, and therefore repurposing was technically not possible. Officially the glass slides needed to be ground to dust rather than passed on. No one found this outcome acceptable and unofficial arrangements were consequently made for academics to take the slides they felt they might be able to use in teaching or research. After this, the sculptor Mary Goody, with her partner Xavier Ribas, Lecturer in Photography, packed up the hundreds of thousands of remainders into banana boxes and stored them in Goody’s studio at Brighton’s Phoenix Gallery (). Brewis, Goody and I all took photographs of the slide library and its apparatus in situ in 2011.

The Bigger Picture: Declining Slide Libraries in Wider Practice

The dismantling process outlined was one replicated, to a greater or lesser extent, in institutions with similar collections across Europe and North America in the years around 2010. In some instances, campaigns to preserve 35mm slide libraries as institutional archives achieved some success, but this was relatively uncommon.Footnote15 A survey of 112 slide collections in the USA, for example, undertaken by the Visual Resources Association (VRA), showed that only 24% remained intact by 2014. The process at Brighton, where the largest body of disposed slides was donated to artists, was shared by nearly half (47%) of the institutions surveyed by the VRA.Footnote16

The eight authors of the VRA survey, collectively styling themselves the ‘Slide and Transitional Media Task Force’, produced 2014 ‘Guidelines for the Evaluation, Retention and Deaccessioning of 35mm Slide Collections in Educational and Cultural Institutions’. These came too late for the University of Brighton collection, but its reflections remain useful as a series of claims to be tested about what is worth retaining and what should be dumped. The latter category included discoloured, scratched, faded, dirty, mouldy and out-of-focus slides. Those involved in ‘weeding’ exercises were advised to note the ‘primary concern’ of the slide’s source. One featuring ‘original photography’, they noted, ‘should be considered with more deliberation than one that was photographed from a book’.Footnote17 The pedagogic slide’s ‘ultimate value’, however, was described as:

1) the film that was in the photographer’s camera when out in the field, 2) the difficult-to-find didactic images that were photographed out of a book to explain the context of a work of art or the design processes of architectural monuments, 3) the reflection of the institution’s curricular choices over time, or 4) a record of a campus’ or region’s history.Footnote18

From circa 2009 to circa 2014, then, international discussions about the future of pedagogic 35mm slide libraries peaked in intensity as plans to break them up, digitise them or replace them sped into action. There had been prior discussions anticipating the death of the form, however, on both sides of the Atlantic, including from artistic perspectives. In Artforum International in 2004, Pamela M. Lee considered ‘the twilight of the slide projector’ at the point when Eastman Kodak ceased production. She noted ‘its ubiquity in both studio and art-historical pedagogy’, and argued that it had ‘played more than a supporting role in the visual arts from its inception, however much its use has been obscured by the more spectacular machinations of the art world’.Footnote20

A 2005 exhibition, SlideShow, displayed at Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland, among other US locations, examined the use of projected images in contemporary art and reflected on their changing status. As slides were once the means of ‘preserving and projecting history’, curator Darsie Alexander reflected in the accompanying catalogue, it was pertinent that contemporary artists are using them as a medium to reflect on their own historical status.Footnote21 As photographic historian Martha Langford observed, in her 2015 consideration of contemporary artists’ engagement with slide projectors, Alexander’s survey took place while the expired medium’s body was still warm.Footnote22 Yet Langford’s question, posed in the title of her article, ‘When the Carousel Stops Turning … What Shall we Say about the Slide Show?’, indicated that there were still further answers needed; the matter was not resolved then. My argument here is that there is more still to be said in our changing times.

Five years before SlideShow, art historian Robert S. Nelson, in a 2000 article for Critical Inquiry, speculated on the future of the form as he predicted ‘what is commonplace today is about to be digitalized into oblivion’.Footnote23 For Nelson, this was not simply a matter of a change of medium. He argued that slide lectures, ‘like the photographic technology that made them possible, have had a profound impact on art history; indeed, for many who have passed through university classes, art history is the illustrated lecture’.Footnote24 With the demise of the pedagogical slide, he wondered whether the discipline itself was at risk. Stood on the brink of technological change, Nelson worried:

Where will the art historian stand in cyberspace, and what codes, disciplinary, performative, or otherwise, will control the content and guarantee the reliability of art presentations? Will not the new ability to seamlessly merge text, image, and sound dissolve distinctions between written and oral, past and present, primary and secondary, and art criticism […]?Footnote25

The Bigger Picture: Declining Slide Libraries in Wider Cultural Contexts

At the close of the University of Brighton slide library, I seized what I could from the collection and Goody took the rest. In 2018, however, Goody returned her hundreds of thousands of slides to the university, unable to take on their artistic reinterpretation as her circumstances changed; their institutional fate is again uncertain. My own twenty thousand or so slides remain barely touched. The urgency to preserve at a moment of crisis has now passed, yet in the years since the library’s closure, the culture of slides has shifted in three key contexts. What they are now is not what they once were.

The first shifting context is that the 35mm slide and the slideshow have become increasingly adopted as subject matter and medium in post-digital art practice, meaning art that critiques digital culture, especially its closed structures, its scripted systems and its apparent pristine perfection.Footnote27 This continues the artistic tendency of ‘archival impulse’ identified by Hal Foster in 2004, and, indeed, continues some of the earlier conceptual art interests in information systems and institutional structures since the 1960s and 1970s. Arguably, however, the archival impulse offers distinctive new dimensions in a highly networked, always-on digital economy, as noted by art historian Claire Bishop. The contemporary art and exhibitions that Bishop scrutinises typically present large bodies of unsynthesised data to reflect on complex contexts and information systems; she characterises their most conspicuous signifiers as outmoded information technologies, including slide projectors.Footnote28

While the projected image has been a form with artistic appeal for some time, as documented in surveys by Alexander, Lee and Langford, both slide and slide projector produce a changed set of meanings now their technology has become obsolete and post-digital aesthetics have consolidated.Footnote29 I have characterised these contemporary art practices as metapictorial, as art about art or slides about slides.Footnote30 For those who produce it, such as artist Philipp Goldbach, it is also art about categories of cultural knowledge; the ‘internal conflict about the value of the obsolete teaching material’, which took place when he took possession of the deaccessioned slides of University of Cologne’s Institute of Art History, gave him his subject.Footnote31 Additionally, artist and archivist Jane Birkin characterises contemporary artists’ attraction to the slide projector’s ‘whirr and click as the cog moves and the slide moves on’ as ‘a corrective to newer media solutions for showing images’; she also sees it as a mourning for the mechanical in a digital age.Footnote32

This provides a second shifting context: the retro marketplace. While a taste for so-called vintage or nostalgic collectibles, including cult and outmoded technologies, has been rising among the young and affluent in Europe and North America since at least the 1990s, such practices – and their studies – have grown and consolidated over the last decade.Footnote33 There is, indeed, a local character to these growing commercial cultures, as demonstrated by the tongue-in-cheek Hipster Index of 2018, which quantified 446 cities against a measure of how many record shops, vintage boutiques, vegan restaurants, coffee shops and tattoo parlours they possess per 100,000 residents. Brighton achieved top ranking above Lisbon, Portland and Helsinki.Footnote34 Secondhand emporia abound in the city and local junk shop dealers tell me that slides and associated technologies, especially from the 1960s and 1970s, are increasingly abundant as a result of end-of-life house clearances. They sell cheaply and very regularly alongside analogue photographs and parallel residual media, such as vinyl records. The overlap with artistic practice, previously cited, is notable; many consumers are students purchasing materials for art projects. Many are young – typically they are teenagers or in their early twenties, born in the twenty-first century.Footnote35 Slides, to these born-digital consumers, are exotic technologies from another time, invested retrospectively with an aura of error and authenticity with which perfectible digital culture cannot compete.Footnote36

The third shifting context is the development of an increasingly sophisticated body of literature over several overlapping territories in the last decade, including on the materiality of the photograph and visual media more broadly, especially through the work of Elizabeth Edwards; on the photographic archive and picture library, for example through the work of Costanza Caraffa; and on media archaeology as an emergent field, as exemplified in the work of Jussi Parikka.Footnote37 While it is beyond the capacity of this article to map this scholarship comprehensively, it is notable that increasingly sophisticated frameworks now exist for making visible and legible previously overlooked photographic categories, systems and networks; for thinking haptically with the visual; for considering historical media as material culture; and for dealing theoretically and methodologically with photographs in vast quantities. These new directions have emerged in direct response to digital culture’s seeming immateriality. Despite expectations to the contrary, new practices do not simply replace the old but instead provide fresh post-digital frameworks with which to understand historical forms. These concepts and structures inform my interpretations of their remains.

The Smaller Picture: Scrutinising What Remains

Framed by the aforementioned debates and the questions they raise, and using their measures as criteria, how does the University of Brighton slide library look over a decade after its decline? The following section closes in on three groups of slides now in my possession to provide three sets of answers.

One: Windows on the Library

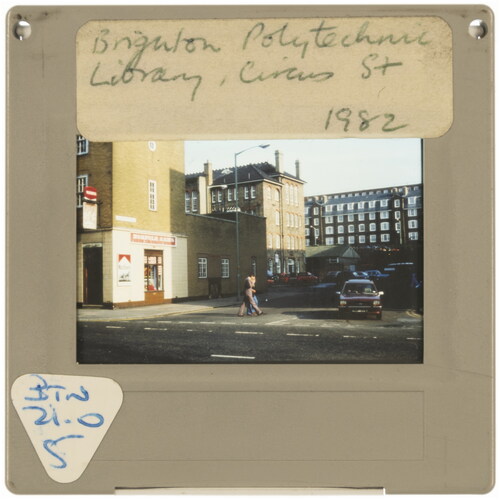

The first group of slides, creating a direct echo of Leonard’s Analogue project, document changing shop fronts and street scenes in Brighton. Hastily filling crates of slide folders at the closure of the library, I particularly looked for images that might show, in a metapictorial sense, the history of slides themselves, including those visualised in histories of photography. Outside of photography per se, however, sections of the collection depicting histories of Brighton included slides of the inside and outside of the university library. These showed both the slide library and the buildings in which it was housed (). One example, taken in 1982 of Circus Street, shows the former library building, now demolished and the site of a large-scale multimillion pound urban rebuild, described in 2021, in the developers’ own words, as ‘an innovation quarter and a powerhouse for regeneration’ in the city centre ().Footnote38 The slide scene includes a maroon Ford Fiesta car waiting at a junction, two crossing figures dressed in flared trousers, the Norfolk Arms pub – now Brewdog – complete with Marlboro cigarette advertising, as well as the Victorian brick buildings of the former library and the 1930s Milner Flats to the rear. The slide is uncredited to its maker, but former librarians told me that they used to take cameras loaded with slide film to record the changing city environment and to furnish the slide library with up-to-date material.Footnote39 Unlike copies of illustrations in art books or slides produced by museums of their collections, these slide views of Brighton are original productions. They are, according to the VRA Task Force, ‘the film that was in the photographer’s camera when out in the field’: their first category of significance. The status of the slide photographer is, under VRA criteria, a central matter for evaluation; they suggest Ansel Adams as an example of a practitioner whose work should be kept in any cull. They are not concerned with photographs by library employees. Yet slide librarians produced material that is otherwise unavailable of places that cease to exist, meeting the VRA’s first principle: ‘Keep anything that is not available someplace else’. The guidelines also note: ‘images of local history […] are especially important to keep’.Footnote40

Figure 5. ‘Choosing Slides’, undated 35mm slide, photographer and model unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Richard Boll, 2019.

Figure 6. ‘Brighton Polytechnic Library, Circus Street, 1982’, 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

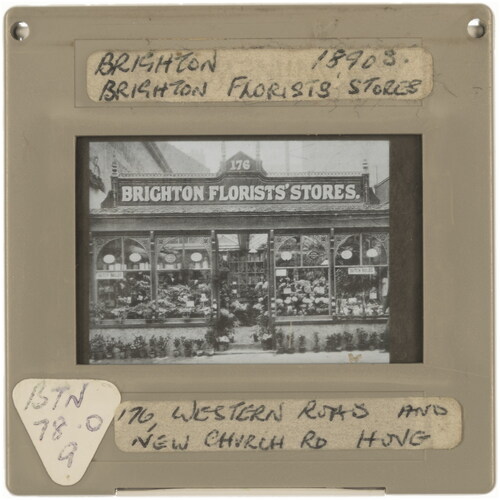

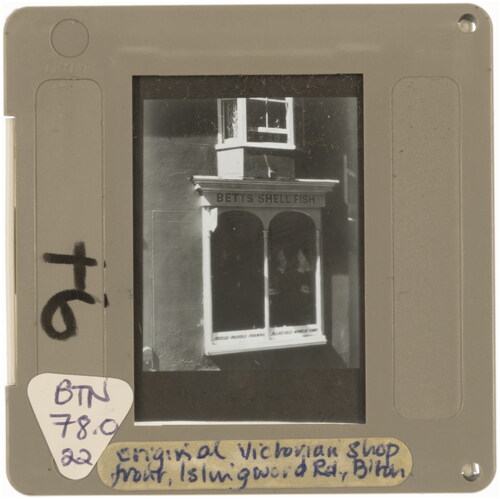

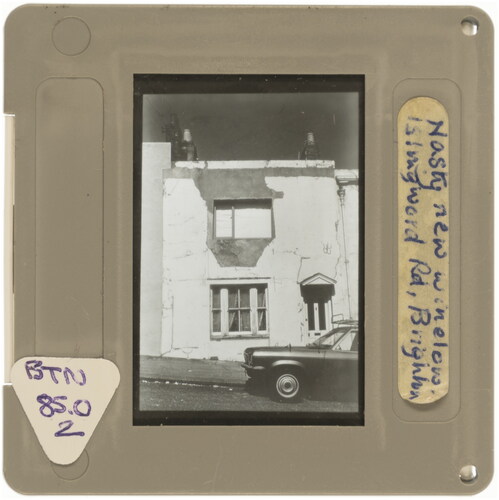

To update existing slide holdings of 1890–1900 photographs of shop fronts and services, from florists to furniture shops, anonymous but comparable to the work of Eugene Atget in Paris (), Brighton slide librarians toured the town in the 1970s–90s in search of the enduring and the changing, which they photographed in contrast.Footnote41 An undated pair of monochrome slides, taken in Islingword Road in the Hanover region of Brighton, for example, documents an ‘Original Victorian shop front’, Betts Shell Fish (), and an ‘Ugly new shop front’ (), an unnamed launderette, according to their handwritten labels. A related pair of slides, classified under ‘Brighton and Hove: Windows’, records local change in domestic housing. The first, depicting a two-up–two-down Victorian terraced house in a poor condition with bare render and cracked plaster, is labelled ‘Nasty new windows, Islingword Road’ (). The second, showing a three-storey Victorian terraced town house near Brighton railway station, with air vents replacing windows, is labelled ‘Mutilated house, No. 3 Over Street’ ().

Figure 7. ‘Brighton Florists’ Stores’, 1890s, 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

Figure 8. ‘Original Victorian Shop Front, Islingword Road, B’ton’, undated 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

Figure 9. ‘Ugly New Shop Front, Islingword Road, Brighton’, undated 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

Figure 10. ‘Nasty New Windows, Islingword Road, Brighton’, undated 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

Figure 11. ‘Mutilated house, No. 3 Over St, Brighton’, undated 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

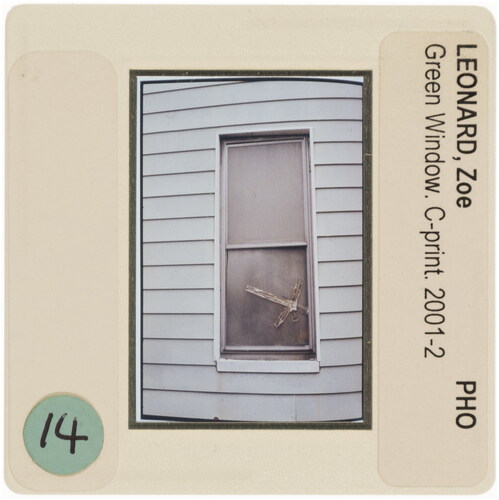

These slides are not neutral documents for social history but emotionally invested photographic interventions by slide librarians acting as cultural producers and commentators on regeneration and conservation matters. Their visual similarity to slides in the collection’s photography section, specifically Zoe Leonard’s early 2000s photographic series of urban bricked-up windows and smashed panes repaired with sticky tape, is striking. Slide reproductions of Leonard’s C-prints and gelatine silver prints were carefully labelled with date and medium, with their titles, ‘Green Window’ and ‘Wall’, and, not least, the artist’s name. Brighton slide librarians’ photographic work is anonymous and unlikely to be exhibited on the walls of any elite art gallery, and yet they should be more highly prized, in the criteria provided by the VRA Task Force; they are originals rather than copies ().

Figure 12. ‘Leonard, Zoe. Green Window. C-Print. 2001–2’, undated 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

Figure 13. ‘Leonard, Zoe. Wall. Silver gelatine print. 2002’, undated 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

What constitutes an original in photography is always contested in a medium usually associated with reproduction and multiplicity. ‘Photographs are but one link in a potentially endless chain of reduplication’, as Craig Owens has put it; ‘themselves duplicates (of both their objects and, in a sense, their negatives), they are also subject to further duplication’.Footnote42 Nonetheless, slides produced directly from slide film have some claim to originality. In their ‘posthumous assessment’ of the slide library, published in 2009, art historians Beth Harris and Steven Zucker argued that all slides, even those that duplicate other images, hold a ‘quasi unique’ status. They observed:

Paradoxically, even in the age of mechanical reproduction, the slide maintained a degree of residual authenticity. After all, despite its raison d’etre as a reproduction, each slide is, in some important ways, unique. The mounts might be plastic, wood or glass, the labels printed on a laser printer, or typed […] The age of the slide was apparent from these mounts and the color degradation of the image itself (unless it was black and white). In the form of the slide, the reproduced image meets the beholder only ‘halfway,’ to use Walter Benjamin’s term. In other words, it is a subsidiary yet unique object that itself exists in one place at one time.Footnote43

Two: Acts of Visibility

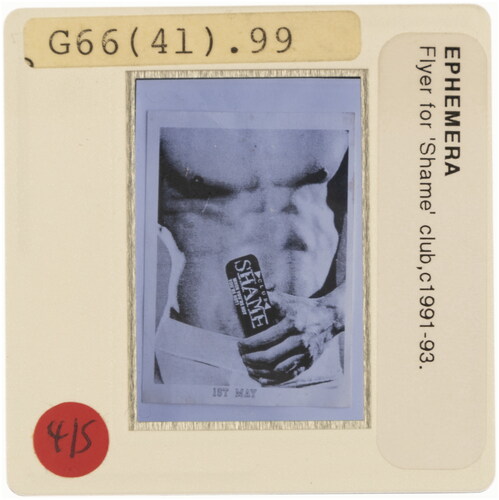

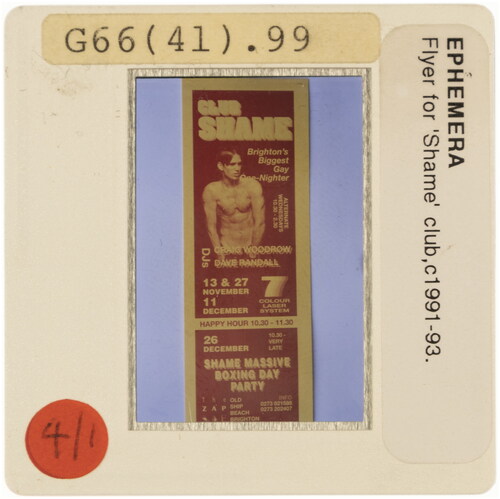

A second body of material from the Brighton slide library that offers a case study of shifting cultural values is a collection of twenty-five 1991–93 nightclub flyers from the Club Shame events held at the Zap Club, Kings Road Arches, Brighton. Against the VRA criteria, these slides should be valued as they provide both ‘a record of a region’s history’ and a ‘reflection of the institution’s curricular choices over time’; they could also inhabit their ‘difficult-to-find’ image category. Photographed to support the visual culture teaching of Paul Jobling, former Professor in the History of Art and Design department, from his private collection, they are as much a history of a life lived as they are of the department and the town ( and ).

Figure 14. ‘Flyer for “Shame” club, c1991–3’, undated 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

Figure 15. ‘Flyer for “Shame” club, c1991–3’, undated 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

Club Shame, established in 1989, described itself as a ‘sexy gay dance club’ and was held weekly on Wednesday nights at a Brighton beach front venue, the Zap Club, until 1994. It consciously endeavoured to break nightlife norms for gay men and their allies. Its founder, Paul Kemp, described the club’s ethos as ‘in your face and unapologetic. The name Shame indicated a new trend towards gay people reclaiming negative stereotypes and turning them around to their advantage’.Footnote44 Brighton’s status as the UK’s gay capital was growing in the same years, and clubs such as Shame were a key part of the new mentality and provided blueprints for gay visibility in the new decade.Footnote45 They consolidated local communities but also reached further; most literally, special buses were provided to transport Club Shame clubbers from the capital.

Club Shame’s aesthetic, communicated through its striking promotional leaflets, was a bricolage of pop culture references to highly sexualised masculinity. The flyers’ rough-and-ready collage style juxtaposed visual references from historic and contemporary illustration and magazine photography, from Tom of Finland to Herb Ritts. As Kemp stated in 2012, in interview with Visual Culture scholar and queer Brighton DJ, Kate Wildblood, ‘We didn’t have the luxury of slick computer graphics back then so we literally cut up photographs, which gave everything a nice, hard, edgy and underground feel’. With wit and dynamism, Shame’s flyers built bold new multilayered representations of hypersexualised heroes for its participants. As Wildblood has persuasively argued, Shame’s visual messages resisted dominant representations of weak, diseased gay male bodies in the AIDS era.Footnote46

In the context of the University of Brighton slide library, these images created a valuable record of a collection otherwise unavailable for consultation; even today, although there are Facebook pages dedicated to the memory of the club, and a broader culture of collecting British gay histories – see, for example, the dedicated endeavours of Bishopsgate Institute, London – the Club Shame flyers depicted in the slides are not publicly accessible in any archive and remain rarities. As ephemeral material designed only to promote passing events and then to become redundant, their one-night-only qualities make them more susceptible than other material to disposal and erasure. In the early 1990s, in addition, marginalised groups more rarely featured in cultures of record. To create another link to a Zoe Leonard slide in the collection, it is notable that the artist had to falsify a public photographic archive of the fictional black lesbian heroine at the centre of Cheryl Dunye’s 1996 film The Watermelon Woman. There were no public historical resources that could be drawn upon; Leonard had to imagine her own ().

Figure 16. ‘Leonard, Zoe and Dunye, Cheryl The Fae Richards Photo Archive 1993–6’, undated 35mm slide, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photography by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

Their position in a university slide library provided Club Shame flyers with some consecration and – temporary – preservation status. Their institutional location also created a record of pedagogic practices, especially in relation to Brighton’s longstanding specialism in design history and the contribution of Jobling in particular.Footnote47 The photographed flyers’ signs of use – their dogeared corners, stains and folds – provide another level of information as they are both indexes and icons of the experiences they promoted and thus, even as duplicated objects, they tell singularised stories; they were part of the events they record. Their status as originals in the VRA evaluation criteria is complicated by the fact that they are copy material (slides), of photocopied material (flyers), that was itself the product of intertextual copy and paste (collage). Their duplicate visual form overlays other duplicate visual forms; to borrow gay style slang, they are perhaps best described as clones.Footnote48

Three: Makers’ Marks

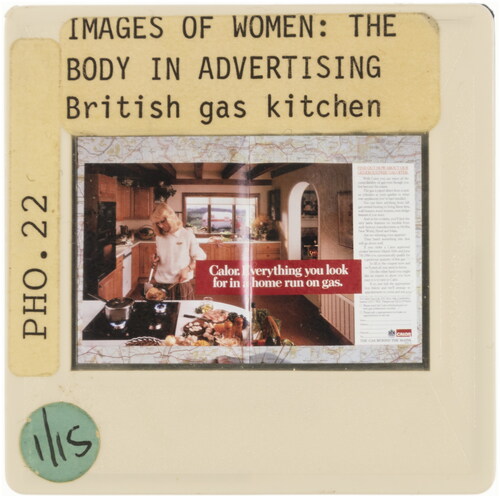

A final focal point from the University of Brighton collection counters one of the VRA criteria for evaluating slides. I have argued elsewhere that the deteriorated, faded and cracked slide – that which fits within the VRA’s core list of slide material to be eliminated at first cull – can nonetheless provide revelatory cultural information about the slide as a form.Footnote49 The VRA states that original photography should be considered more valuable than slides photographed from books, but this can be contested in certain cases. Specifically, I am thinking about slides in the Brighton collection from the mid-1980s that populate a sheet entitled ‘Images of Women’. Compiled by librarians from illustrated colour magazines in the mid-1980s, the dozen or so images show representations of women in advertising and editorial photography as a means of capturing contemporaneous perspectives on gender. In most cases the edges and gutters of the printed pages are visible in the slide. In one case, a librarian’s finger appears as it keeps the magazine in place on the copy stand ().

Figure 17. ‘Images of Women: The Body in Advertising. British Gas Kitchen’, undated 35mm slide, ca. 1985, photographer unknown, former University of Brighton slide library, collection of Annebella Pollen. Photograph by Rachel Maloney, 2021.

The advertisement, for the gas supplier Calor, incorporated a photograph of a young woman preparing a meal in an open-plan kitchen–living room to show gas hobs and a gas fire simultaneously, to invoke comfort and convenience, as well as to infer domestic norms and aspirations. The slide, however, shows the advertisement and more: it reveals its magazine position as a double-page spread with a central fold; it reveals the technologies of production as the photographic flash is reflected on the glossy paper; and, most significantly from my perspective, it reveals the shadow of the photographer and their finger in the frame. For a slide librarian, the result must have served its function as an illustration as it entered the collection in the mid-1980s and remained there until 2011, but it also would have been perceived to contain failings by some slide librarians’ standards.

As Brewis recalled, in 2021, decontextualisation was the ambition. ‘When we searched, selected and photographed an image’, she explained, ‘we tried to erase any feature that might reveal any source we had used (i.e. book or journal); we would therefore hide text with masking tape and try to avoid double page spreads’. As she noted, however, ‘sometimes that was impossible’.Footnote50 The mechanics of the production process was not meant to be seen; the slide’s structure was rendered invisible. To borrow the language of the format, information was meant to be transparent. Brewis reflected on the librarians’ thought process: ‘This was our part in the fiction that the 35mm slide viewed in the lecture theatre was just one stage removed from actually perceiving the original work in situ’. The image as a stand-in for the real thing, had, however, an amusing counter-effect when the library was burgled. Thieves prized open a locked filing cabinet in the collection marked ‘jewellery’ only to find slides of jewels rather than jewels themselves.Footnote51

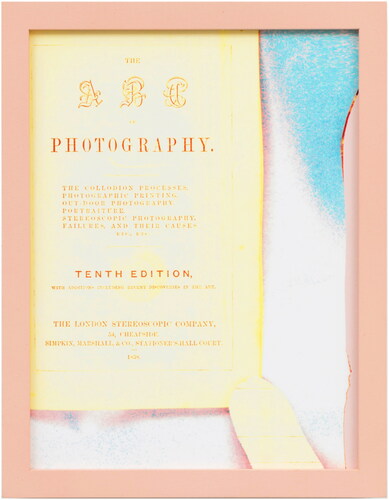

Canadian artist Annie MacDonell has exhibited, as artwork, selected sequences of pedagogic slides thrown away by academic institutions.Footnote52 Her choices reveal the folds, edges and shiny paper print finishes of their sources; in deaccessioning, they would have been the first to be culled. What such errors reveal, however, are the hidden labour practices that lie behind such image productions. For all their transparency, slides occlude certain stories. The finger and the shadow in the Brighton example reveal the maker’s mark. Its accidental presence is a prompt to remember that every slide needed work to produce it and every slide library needed employees to maintain it. Contemporary artists who make work about disembodied and dematerialised digital culture have also looked out for these moments – the glitches in the system – to reveal that friction-free image supply is a capitalist fantasy that serves the privileged few and erases unequal others.

Andrew Norman Wilson, for example, in his ongoing series ScanOps (2012–present), searches the pages of the vast digitisation programme that is Google Books to find the places where the fault lines show. The speed at which the photographers must arrange each book, turn its pages and operate the camera inevitably leads to mistakes; these include the accidental snapping of the labourers’ hands. For Wilson, a former Google employee sacked for his investigations of internal company processes, the photographs reveal the reliance of the corporation on the lowest paid employees with the most limited rights as image workers; the labourers are often women and people of colour. The information economy’s exploitative practices are conveniently concealed when digital images appear as if by magic from clouds and ether.Footnote53 The circumstances of contemporary Google scanning operations are different to historic slide library practices, but a productive comparison can be staged; in both instances, a materialist as well as a material reading of photography is needed ().

Figure 18. Andrew Norman Wilson, ScanOps (The ABC of Photography), 2012–present. Courtesy the artist and Document Gallery, Chicago, IL.

Art historian Ben Burbridge has observed in 2020’s Photography after Capitalism that works such as Wilson’s illuminate the often-covert operations between photography and labour. ‘The fact that attention remains focused on the representational content of photographs and not the technical, political and economic infrastructures that sustain the photographic image’, Burbridge complained of current photographic scholarship, ‘helps to mask photography’s direct and material relationships to neoliberal economics’. Artists who instead engage with digital image systems demonstrate the political imagination required to expose and challenge concealed power structures.Footnote54 A finger in the frame may be a modest intervention but the error nonetheless disrupts the disembodied fantasy; this applies as much to slides in the mid-1980s as it does to Google Books in the 2020s. In art, too, it matters whose finger is in the frame: some cultural producers are deemed important enough to be credited as artists while others remain anonymous as mechanical camera copy stand operators.

Conclusion: New Mediations of Old Media

The fallibility of the 35mm pedagogic art history slide – its inconvenience, its capacity to break and get dirty, and its lumpen materiality – was what prompted academic institutions to dispose of them in favour of a slick digital alternative that seemed easier, more convenient and higher quality. The savings in terms of space and staff added to their attraction. There is no doubt that 35mm slides are limited in their functionality, that their equipment was and is prone to breaking, and that collections were idiosyncratic in scope and organisation. Nonetheless, many of these characteristics are now particularities that are sought out in slides. For the scholars who analyse them, the artists who make work about them and the young people who buy them, slides as outmoded technologies contain medium-specific material and materialist qualities; their problems may be merits. Their conditions and values are made most visible at the moment of their passing.

As historical photographs persisting in the present day, the meanings of slides are remediated in each new place and time. Slide librarians tried to erase their own presence to offer an unmediated slide viewing experience. ‘The projected image’ was, as a result, as Nelson described it in 2000, ‘a simulacrum of the art object, an entity that in some way is that object itself’.Footnote55 The slide’s power as a stand-in gave it potency and rhetorical force in the illustrated lecture – so long as edges and fingers did not show. Set adrift from these pedagogical contexts, in new locations and new times, the slide is imbued with a status that it did not hold as a mere medium of information; its objecthood has become enhanced, even fetishised. The slide is now an object to be looked at rather than through. It is, to adapt Nelson’s claim, less a simulacrum of the art object and more of an art object itself.

If slides are now objects to be looked at rather than images to look through, what kinds of objects are the slides from the University of Brighton collection? They are intensely situated and peopled. For all their apparent neutrality and transparency, they are full of particularities and presences, including the tastes and interests of those who collected their contents and took their images, both academics and library staff. They reveal the streets they walked and the clubs they attended, even if their names were not recorded and only shadows and glimpses remain. Archivist Joan M. Schwartz has defined duplicates as ‘multiple original photographic documents, based on the same image, but made at various times, for diverse purposes and different audiences’.Footnote56 The absolute values of uniqueness and originality are complicated in the form of slides, which may be street photographs on slide film – views of changing Brighton – or copies of copies of copies in collaged ephemera. Brighton slides, even if dismissed as duplicates, depict places and practices now gone. They offer tangible traces of teaching and research, and their support services, each with their own agendas, whose handwriting and crossings out, commentaries and controversies are often still visible.

To apply the Florence Declaration for the preservation of analogue photography archives, as ‘objects endowed with materiality that exist in time and place’, slides gain meaning from when and how they are apprehended.Footnote57 Brighton slides had one set of meanings when they were in use as a pedagogic service; they gained another at the point of dismantling. More than a decade on, their cultural value has shifted again. This article does not propose solutions for what should be done with pedagogic slide libraries; in most cases, that ship has sailed. Guidelines and recommendations for their preservation and dismantling have been produced by task forces and as collective declarations. For slide libraries now dispersed, these evaluation structures can only be postmortem measures of what remains. New literatures, such as media archaeology, offer new perspectives on reading the past through the digital present. Self-reflexive analogue art practice in a digital age, and especially post-digital art practice, can visualise where new media breaks down and exposes its own condition. New generations of secondhand consumers, too, apply new interpretations as they move the images to new contexts. To understand slide library remains in the round, however, requires a material and a materialist reading of the cultural labour that produced its objects and made them meaningful.

The author wishes to thank photographer Rachel Maloney and the Centre for Design History at the University of Brighton, UK for their support in the production of illustrations.

Notes

1 – The Deutsche Börse Photography Prize, established in 2005 in partnership with The Photographers’ Gallery, London, ‘is awarded annually to a living artist of any nationality who has made the most significant contribution, either through an exhibition or publication, to the medium of photography in Europe in the previous year’. In 2010, the nominees were Zoe Leonard, Anna Fox, Donovan Wylie and Sophie Ristelhueber (the winner). Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation, ‘Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2010’, 〈https://www.deutscheboersephotographyfoundation.org/en/support/photography-prize/2010.php〉.

2 – Zoe Leonard, born in 1961 in New York, is a widely acclaimed artist working mostly in photography and sculpture. Analogue has appeared in various iterations, including as a publication and as an exhibition at various sites including New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2015. Zoe Leonard, Analogue (Columbus: Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio State University, 2007).

3 – British education institutions providing degree-level art and design teaching were subject to governmental restructures in the 1960s and 1970s, leading to a requirement for fifteen per cent of content in art history and ‘complementary studies’, elements also termed ‘contextual studies’ and ‘critical studies’ in different institutions; see Art Education: Documents and Policies 1768–1975, ed. by Clive Ashwin (London: Society for Research into Higher Education, 1975); and Critical Studies in Art and Design Education, ed. by Robert Hickman (Bristol: Intellect, 2008). For a discussion on how they relate to University of Brighton, see Annebella Pollen, ‘My Position in the Design World: Locating Subjectivity in the Design Curriculum’, Design and Culture, 7, no. 1 (March 2015), 85–105.

4 – David Graeber, Towards an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of our Dreams (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002), 3.

5 – For the core conceptual structures that inform my thinking on cultural value and its application to visual and material culture, see Michael Thompson, Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979); Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds (Oakland: University of California Press, 1982); and Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: The Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984).

6 – Annebella Pollen, ‘Photography’s Mise en Abyme: Metapictures of Scale in Repurposed Slide Libraries’, in Photography Off the Scale: Technologies and Theories of the Mass Image, ed. by Tomáš Dvořák and Jussi Parikka (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 113–39.

7 – Zoe Leonard quoted in Huey Copeland, ‘Photography, the Archive, and the Question of Feminist Form: A Conversation with Zoe Leonard’, Camera Obscura, 28, no. 2 (83) (2013), 177–89 (186); Zoe Leonard and Cheryl Dunye, The Fae Richards Photo Archive (New York: Artspace, 1997); and Zoe Leonard, You See I am Here After All (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010).

8 – Copeland, ‘Photography, the Archive’, 177.

9 – For histories of the uses of slides in art history education, see Costanza Caraffa, ‘From “Photo Libraries” to “Photo Archives”: On the Epistemological Potential of Art-Historical Photo Collections’, in Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History, ed. by Costanza Caraffa (Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2011), 11–44; Jennifer F. Eisenhauer, ‘Next Slide Please: The Magical, Scientific, and Corporate Discourses of Visual Projection Technologies’, Studies in Art Education, 47, no. 3 (2006),198–214; and Robert S. Nelson, ‘The Slide Lecture, or the Work of Art History in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Critical Inquiry, 26, no. 3 (Spring 2000), 414–34.

10 – For the history of Brighton School of Art, see Jonathan M. Woodham, ‘Brighton School of Art: The Victorian Age to the Twentieth Century’, 〈http://arts.brighton.ac.uk/arts/alumni-and-associates/the-history-of-arts-education-in-brighton/brighton-school-of-art–-the-victorian-age-to-the-twentieth-century〉.

11 – The firsthand information about the history and maintenance of the slide library is drawn from Mary Goody, interview with Monica Brewis, retired slide librarian, and Belinda Greenhalgh, former slide library assistant, University of Brighton, 2013; Annebella Pollen, interview with Monica Brewis, 2018; and Annebella Pollen, email correspondence with Monica Brewis, March 2021.

12 – The slide library was boosted, for example, by the extensive donation of slides from the former Lewis Cohen Centre for Urban Studies at University of Brighton, which operated in the 1980s and 1990s and was dedicated to the study and preservation of Brighton’s historic built environment.

13 – Hilary Evans, Picture Librarianship (London: Clive Bingley, 1980), 183.

14 – Monica Brewis, email to the Faculty of Arts, University of Brighton, 21 May 2009.

15 – Useful summaries of the arguments and practices at this time include Jenny Godfrey, ‘Dodo, Lame Duck or Phoenix? How Should we Consider the Slide Library?’, Art Libraries Journal, 29, no. 3 (2014), 28–33; and Jenny Godfrey, ‘Dodo, Lame Duck or Phoenix, Part 2? Can or Should we Preserve a Slide Library for Research?’, Art Libraries Journal, 29, no. 3 (2014), 12–20.

16 – Visual Resources Association Slide and Transitional Media Task Force, ‘Tell Us Where Your Slides Are, Summary of Survey Results’, 2014, 〈https://www.vraweb.org/slide-and-transitional-media〉.

17 – Visual Resources Association Slide and Transitional Media Task Force, ‘Guidelines for the Evaluation, Retention, and Deaccessioning of 35mm Slide Collections in Educational and Cultural Institutions’, September 2014, 2, 〈https://www.vraweb.org/slide-and-transitional-media〉.

18 – Ibid., 1.

19 – Costanza Caraffa, ‘Florence Declaration – Recommendations for the Preservation of Analogue Photo Archives’, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, 2009, 〈https://www.khi.fi.it/en/photothek/florence-declaration.php〉.

20 – Pamela M. Lee, ‘Split Decision’, Artforum International, 43, no. 3 (November 2004), 47–48.

21 – Darsie Alexander, ‘SlideShow’, in SlideShow: Projected Images in Contemporary Art, ed. Darsie Alexander (London: Tate Publishing, 2005), 3–32 (32).

22 – Martha Langford, ‘When the Carousel Stops Turning … What Shall we Say about the Slide Show?’, Intermédialités / Intermediality 24–25 (Autumn 2014–Spring 2015), para. 2, 〈https://doi.org/10.7202/1034158ar〉.

23 – Nelson, ‘Slide Lecture’, 414.

24 – Ibid., 415.

25 – Ibid., 434.

26 – I borrow the term residual media from Residual Media, ed. Charles R. Acland (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); and the term zombie media from Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parikka, ‘Zombie Media: Circuit Bending Media Archaeology into an Art Method’, Leonardo, 45, no. 5 (2012), 424–30.

27 – Recent accounts of post-digital art practice using slide projectors are provided by Jane Birkin, Archive, Photography and the Language of Administration (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020).

28 – Claire Bishop made these points with these examples in her 2019 keynote lecture for the Association of Art History at University of Brighton: ‘Information Overload: Research-Based Art and the Politics of Attention’. The arguments underpin her forthcoming book. Claire Bishop, Disordered Attention: How We View Art and Performance Today (London: Verso, 2024).

29 – The phenomenon of the post-digital has been defined usefully by Florian Cramer as ‘either a contemporary disenchantment with digital information systems and media gadgets, or a period in which our fascination with these systems and gadgets has become historical’. Florian Cramer, ‘What is “Post-digital”?’, in Postdigital Aesthetics: Art, Computation and Design, ed. by David M. Berry and Michael Dieter (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 13–26 (13).

30 – Pollen, ‘Photography’s Mise en Abyme’.

31 – Katharina Täschner, ‘Increasing the Image Noise: Conversation with Philipp Goldbach’, L’Image et Son Double / The Twofold Image, Centre Pompidou (Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou / Spector Books, 2021), 159–62 (159).

32 – Birkin, Archive, Photography, 77.

33 – The literature on retro cultures and nostalgic consumption is now significant; recent analyses across media forms include Media and Nostalgia: Yearning for the Past, Present and Future, ed. by Katharina Niemeyer (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); Heike Jenss, Fashioning Memory: Vintage Style and Youth Culture (London: Bloomsbury, 2015); and Jean Hogarty, Popular Music and Retro Culture in the Digital Era (London: Routledge, 2017).

34 – The 2018 Hipster Index is a tongue-in-cheek data analysis compiled by commercial removal company MoveHub, 〈https://www.movehub.com/blog/the-hipster-index/〉.

35 – Annebella Pollen, interview with Paul Gillman, dealer and cashier since the 1990s at Snoopers’ Paradise, Brighton, a large-scale consortium of more than eighty antique and bric-a-brac traders, August 2021.

36 – The aesthetic and cultural values of technological faults and errors have been discussed extensively in relation to both residual media and new media. For the former, see for example Dominik Schrey, ‘Analogue Nostalgia and the Aesthetics of Digital Remediation’ in Media and Nostalgia, ed. by Niemeyer, 25–74; and for the latter, see Rosa Menkman, ‘Glitch Studies Manifesto’, in Video Vortex Reader II: Moving Images Beyond YouTube, ed. by Geert Lovink and Rachel Somers-Miles (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011), 336–47.

37 – See for example Elizabeth Edwards, ‘Thoughts on the “Non-Collections” of the Archival Ecosystem’, in Photo-Objects: On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives, ed. by Julia Bärnighausen, Costanza Caraffa, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider and Petra Wodtke (Florence: Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge, Studies 12, 2019), 67–82; see also Photo Archives, ed. by Caraffa; and Jussi Parikka, What Is Media Archaeology? (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012).

38 – Circus Street Brighton, developers’ website, 〈https://circusstreetbrighton.com〉.

39 – Pollen, interview with Brewis, 2018.

40 – Visual Resources Association, ‘Guidelines’, 1.

41 – Slide production was undertaken by Brighton slide librarians and by other documentarians of the local built environment, such as members of the Lewis Cohen Centre for Urban Studies. Given that the slide library incorporated several different sources of slides, it is not possible to pinpoint precisely who took and who labelled the photographs discussed.

42 – Craig Owens, ‘Photography “en abyme”’, October, 5 (Summer 1978), 73–88 (85).

43 – Beth Harris and Steven Zucker, ‘The Slide Library: A Posthumous Assessment for our Digital Future’, in Teaching Art History with New Technologies: Reflections and Case Studies, ed. by Kelly Donahue-Wallace, Laetitia La Follette and Andrea Pappas (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), 33–41 (35).

44 – Paul Kemp, ‘Club Shame’, in Zap: Twenty-five Years of Innovation, ed. by Max Crisfield (Brighton: Zap Art / Queenspark Books, 2007), 78–80 (78).

45 – According to the Office of National Statistics, the 2011 census data (the last published) showed that Brighton had the largest gay population in the UK at between eleven and fifteen pre cent of the population.

46 – With thanks to Kate Wildblood for sharing their 2013 BA Visual Culture dissertation. Kate Wildblood, ‘Strike a Pose, There’s Something to It: Imagery in Gay Clubbing 1989–2013’ (unpublished thesis, University of Brighton, 2013).

47 – University of Brighton has been at the forefront of the discipline of design history in Britain since the 1970s and has operated a formally funded Centre for Design History since 2017. Paul Jobling taught at Brighton from the 1990s to 2018.

48 – Clone is a gay male fashion style, originating in the USA, which evokes the working dress of historic US working-class men.

49 – Pollen, ‘Photography’s Mise en Abyme’.

50 – Pollen, email correspondence with Brewis.

51 – Ibid.

52 – Sara Knelman and Annie MacDonell, ‘On Images of Images of Images’, in Photography Reframed: New Visions in Contemporary Photographic Culture, ed. by Ben Burbridge and Annebella Pollen (London: Routledge, 2018), unpaginated colour section.

53 – Nina Lager Vestberg, ‘“There Is No Cloud”: Toward a Materialist Ecology of Post-Photography’, Captures, 1, no. 1 (September 2016), 〈revuecaptures.org/node/448〉.

54 – Ben Burbridge, Photography after Capitalism (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2020), 167.

55 – Nelson, ‘Slide Lecture’, 418.

56 – Joan M. Schwartz, ‘We Make our Tools, and our Tools Make Us: Lessons from Photographs for the Practice, Politics, and Poetics of Diplomatics’, Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists, 40 (October 1995), 40–74 (46).

57 – Caraffa, ‘Florence Declaration’, 1.