Abstract

The global tour of Edward Steichen’s 1955 photographic exhibition The Family of Man, sponsored by the United States Information Agency (USIA), has long been viewed as the defining moment for the medium’s engagement in US Cold War diplomacy and propaganda. Yet the attention garnered by this single exhibition has served to obscure an extensive programme of photographic diplomacy developed by the USIA during the late 1950s and early 1960s, and largely overlooked by photographic scholarship. One strand of this programme was shaped by the twin concerns of racial conflict at home and decolonisation in Africa and Asia. As the US government cultivated audiences in the newly independent nations of the emerging Third World, it became clear that it would need to adapt its message. Racial integration became a pervasive theme in the agency’s photographic output as it sought to picture America for its international audiences and visually refute accusations that the USA was an inherently racist society. In contrast to studies of US propaganda output of the early 1950s, which have suggested a limited repertoire for the representation of African Americans, the photographic records for this period provide evidence that the USIA paid close attention to the micro-politics of racial interaction and endeavoured to create a richer and more complete set of representations. Seen in the context of the time, the carefully choreographed portrayals of interracial interaction that emerge from the USIA archives are remarkable, if always highly partial and selective.

The United States Information Agency (USIA) was established in 1953 as the information and propaganda arm of the US government. Following the terms of the Information and Educational Exchange (Smith-Mundt) Act of 1948, the USIA was tasked with supporting US foreign policy objectives and fostering ‘mutual understanding’ between peoples. Its remit included the production of radio, film, television and print media, alongside supporting educational exchanges and running overseas libraries and cultural centres. The agency is best known to historians of photography for sponsoring the global tour of Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man (1955). Yet the modernist spectacle of Steichen’s exhibition has drawn attention away from other aspects of the USIA’s extensive engagement with the medium.Footnote1 The agency was responsible for the production of a vast range of photographic output, circulated across the world in the form of picture stories, pamphlets, posters, illustrated magazines and exhibitions, as well as photographs intended for placement in local press, in some cases distributed as ready-to-use plastic plates. Significantly, the agency’s output was prohibited from being distributed within the USA, a factor that may help explain the lack of attention it has received in scholarship on postwar photography. The aim of this article is to address one strand of this photographic output as it developed through the late 1950s and 1960s: the effort to picture a racially integrated America for global audiences, and specifically those in newly independent African nations.

The postwar period saw significant growth in the use of photography in print media for African readers, mirroring that for African American readers in the USA. In addition to the regular appearance of photographs in an expanding number of newspapers on the continent, there was what Ruth Bush and Claire Ducournau refer to as a ‘boom in magazine culture in the period of the independences’; the medium of photography was central to this expansion.Footnote2 In the USA, John H. Johnson founded the Johnson Publishing Company in 1942, launching Negro Digest that year, followed in 1945 by Ebony and then in 1951 by the weekly news magazine Jet. In South Africa, Zonk! African People’s Pictorial was founded in 1949, and Drum in 1951.Footnote3 The latter reflected the urban African scene in Johannesburg and borrowed heavily from American culture in its features and stories on crime, sport, jazz, fashion and politics, whilst nurturing an emerging generation of black South African writers and photographers. Moreover, Drum had pan-African ambitions and went on to have several editions for different regions of the continent, which ‘became fixtures in west African and east African societies’.Footnote4 In West Africa, Bingo magazine, founded in 1953, was, like Drum, expressive of an African modernity and carried a comparable popular mix of content.Footnote5 It would become the most widely circulated magazine of its type in Francophone Africa. Many of these publications were supported by private capital, as was the case with Drum, owned by Jim Bailey, son of Abe Bailey who had made his wealth in the South African mining industry; and Bingo, which had the financial backing of Charles de Breteuil, a French aristocrat who owned a string of publications across Africa.Footnote6 Other magazines were sponsored by new African states. Horoya, for example, was founded in Guinea in 1961 and controlled by the governing political party.Footnote7 International actors, too, were part of the picture, among them countries from the Eastern Bloc who provided training for African journalists and photographers, and leant support to local publications as well as producing their own output for the continent; and the USIA, whose visual media programme for Africa expanded across the continent as many countries achieved independence from colonial rule.Footnote8

In the context of the rapid decolonisation of Africa from the late 1950s – seventeen African states achieved independence in 1960 alone – the USIA saw the media landscape of the continent as an important arena in which to intervene. At stake were two things. First, the image of US democracy in the international imagination and, of specific interest here, in the imagination of emerging African nations, during a period when those who sought to manage this image had to contend with the rise of the civil rights movement and ongoing racial injustice at home. Second, the imagination of African futures in the minds of the continent’s new elites. The two overlapped, not least because of the parallels that were often drawn between the racism of US society and the colonialism from which most African nations were achieving liberation. As Tsitsi Jaji argues, magazines such as Bingo offered a form of participation in ‘the emergent transnational black cultural sensibility of the years spanning the dawn of independence and new national projects’ and ‘projected a form of black internationalism in print’.Footnote9 The international and transnational dimensions of these publications can be seen as much in their production as in acts of reading, with material frequently exchanged between publications and repurposed for new audiences. Bingo, for example, would re-publish material from Ebony. The USIA sought to place visual and textual content in as many media outlets as it could and produced several of its own newspapers and magazines for African readers, primarily the urban educated classes. Before launching its own picture magazine – Topic – for sub-Saharan Africa in 1965, the USIA had initial discussions with Johnson Publishing about their plans for an African edition of Ebony. Once launched, Topic would frequently carry articles modelled on, and in some cases directly repurposed from, US magazines such as Ebony and Life. The agency sought to counter Soviet and Chinese media operations on the continent, which regularly impugned the USA as an inherently racist society, and to present to its peoples an American vision of the future, aiming to dissuade them from communist alternatives. The central focus of attention in this article is the construction of the USA as a harmonious and racially integrated society in USIA photographic output, and how it evolved during this period as the agency deepened its engagement with African audiences. Yet it is important to keep in mind this wider media landscape within which the agency was only one actor among many and wherein its output was positioned, not least by its African consumers.

An African Looks at the American Negro (), a USIA pamphlet produced in 1956, can be viewed as an early attempt by the agency to grapple with the image of America as seen through African eyes. It was published in several editions and circulated via a network of field posts, overseas offices that were the centre of the agency’s operations and responsible for the distribution of photographs, pamphlets, posters and exhibitions, among other activities. There were significant print runs for Southeast Asia – Karachi (thirty thousand copies), New Delhi (forty thousand copies) – and Africa – Addis Ababa (one thousand copies), Lagos (twelve thousand copies) and Nairobi (ten thousand copies) – with smaller numbers distributed elsewhere across the Near and Far East regions.Footnote10 The agency had picked up a story from the Christian Science Monitor on the visit of Isaka Okwirry, a district officer from Kakamega in Kenya who had toured the USA in 1955 as part of a US government-sponsored leadership programme. This was a signal that the agency was beginning to make a deliberate effort to turn its attention away from European audiences, which had preoccupied its predecessors in the immediate postwar period, and towards those in Africa and Asia.

Figure 1 Unknown photographer, An African Looks at the American Negro (cover), 1956. Master File Copies of Pamphlets and Leaflets, 1953–84, Box 2, Record Group 306. Photograph reproduced courtesy of Black Star Publishing Co. [Declassified Authority: NND30995]

![Figure 1 Unknown photographer, An African Looks at the American Negro (cover), 1956. Master File Copies of Pamphlets and Leaflets, 1953–84, Box 2, Record Group 306. Photograph reproduced courtesy of Black Star Publishing Co. [Declassified Authority: NND30995]](/cms/asset/f22fa3b7-6f54-4218-b1f8-67105dbf6416/thph_a_2323310_f0001_b.jpg)

In fact, the content of the pamphlet displays no special interest in Okwirry, who simply served as a device to frame a narrative of integration and progress for African Americans, his blackness an unstated guarantee of the authenticity of the portrayal for its African and Asian readers. ‘I have seen that in America the Negro is a free man’, the pamphlet quotes Okwirry. An African Looks replayed a visual repertoire that was familiar territory for the agency in its earlier output for European audiences, reproducing photographs of racial integration in education, employment, politics, culture, sport and the military, and promoting US democracy as the solution to the problem of racial injustice. The cover photograph – an intimate image of an African American couple and their young child – raises a more interesting set of questions, however.Footnote11 Laura Belmonte and Melinda Schwenk-Borrell both argue that family portraits were rare in USIA output of the period, where African Americans were typically shown in public or work settings.Footnote12 The argument here, in contrast, is that this image signposts a new direction in USIA photographic coverage. Notwithstanding the fact that such an image may have been unusual for the mid-1950s, familial and interracial intimacy would come increasingly to the fore as the agency turned to producing material for distribution to the decolonising world.Footnote13

From the mid-1950s, the USIA felt impelled to communicate a sanguine and upbeat message about racial progress to non-Western audiences as they began to express criticisms of the racial situation in the USA on the international stage. An African Looks represented a starting point for its visual programme for the Global South. In 1954, the positive narrative that the agency wished to present had been given a degree of credibility by the Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. As a consequence, the producers of An African Looks did not feel it necessary to make more than relatively minor concessions to its African and Asian audiences. It followed a pattern used in earlier pamphlets and many smaller features and photo-stories circulated in the early to mid-1950s, celebrating African American success and emphasising steady progress towards equality. In response to incidents that portrayed US society in a negative light circulating through multiple news agencies across the world, a set of recommendations published in late 1954 offered the following guidance: ‘It is unwise to focus attention on bad conditions unless this helps maintain credibility in a major way […] A lynching should be reported without comment, but the following week there should be a general report of US progress in race relations’.Footnote14 As officials saw it, the aim was to put ‘the Negro problem’ in context, enabling them to ‘focus on advantages of democratic capitalism’.Footnote15

The strategy adopted by the USIA, in other words, was intended to overwrite or obscure images of racial violence and injustice in the international imagination with those of African American progress. In this task it was evidently in competition with other actors. As Leigh Raiford points out, the lynching photographs that had a popular commercial appeal amongst white segregationist audiences in the early part of the twentieth century became from mid-century an important focus of ‘critical black memory’, used by African American activists and campaigners.Footnote16 A photograph of the 1935 double lynching of Dooley Morton and Bert Moore in Columbus, Mississippi, for example, appeared as the frontispiece to ‘We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government Against the Negro People’, a petition presented by the Civil Rights Congress to the United Nations in 1951 and intended to indict the US government under the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The value of the image to communist propagandists was noted by then US Secretary of State Dean Acheson.Footnote17 Not only were such images ‘key referent[s]’ for civil rights activists ‘to re-narrate history, to memorialize past racial violence and terror, and also to mobilize against it and what it stands for in their own historical moment’ – the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, for example, used a photograph of the same lynching on a 1965 poster – but also, significantly for the USIA, the Soviet Union was quick to recirculate visual and textual accounts of lynchings to condemn US society in the eyes of the world, and not least in newly independent Africa.Footnote18

Had the future unfolded in the benign manner visualised in the USIA’s early pamphlets and photo-stories then they may have sufficed to convince the world of the US model of progress. In reality, however, the abstract pronouncements of the Supreme Court and USIA’s carefully constructed image of African American advancement would soon come into direct confrontation with the structural inequalities and entrenched racism of US society. The crisis at Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957, the same year as Ghanaian independence, made it clear that the ease and confidence with which the USIA had presented the story of African American progress could no longer hold.

The events of September 1957, when nine African American students were prevented from entering Little Rock Central High School by the Arkansas National Guard, provided images that reverberated around the world. The incident quickly became a national crisis, with damaging consequences for the US image abroad and perceived risks to its foreign policy agenda.Footnote19 The stand-off, supported by many white residents who opposed desegregation, only ended when President Eisenhower was persuaded to intervene. The iconic photographs of the students entering the school surrounded by US federal paratroopers may have gained credit for the US government among some international audiences, but they were hardly the images of integration that the USIA wished to present. US information officers overseas responded by claiming that the white protestors who directed abuse and violence at the students did not represent the majority of US citizens, and countered international media coverage of the disturbances at Little Rock with positive, if often anodyne, images of racial integration distributed for display at United States Information Service (USIS) centres and circulation to press outlets.Footnote20 But this was a moment of uncertainty for the agency’s message.

The events at Little Rock would echo through the USIA’s visual programme over the decade that followed, as the agency recognised it had to take a more proactive approach to its coverage of civil rights and racial integration. The shape this coverage took was, at least in part, a response to its mission in Africa. To project its message across a rapidly decolonising continent, the agency would be forced to deepen and extend its engagement with the representation of race in the USA, as well as giving more careful consideration to its African audiences.

* * *

As racial injustice pushed up the agenda of US policymakers and became a prominent international issue, the USIA began to expand its photographic coverage. Debates within the agency during the early to mid-1950s, along with various working groups and reports, underpinned the emergence of integration as thematic priority. Alongside the overarching and globally distributed visual statements represented by pamphlets such as An African Looks, and individual African American success stories in the domains of culture, sport and public life, the agency started to build a collection of photographs and picture stories – photo-essays, prepared with text and captions – intended for smaller-scale distribution through overseas field posts and customisation by local or regional publications.Footnote21 A couple of examples, both drawn from the USIA picture story files, serve to illustrate the approach that was beginning to take shape at this moment.

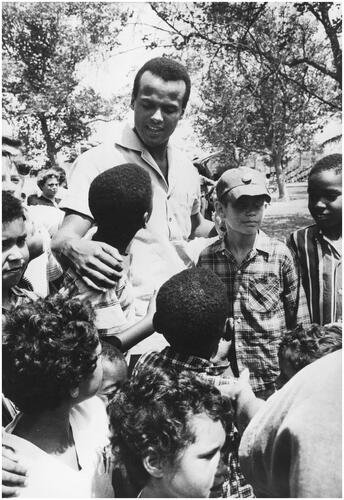

‘Vocal Lesson by Belafonte’ was a short picture story based around the visit of the actor and singer Harry Belafonte to Friendship Day Camp, near Los Angeles, a summer camp intended to foster mutual understanding between children of diverse cultural and racial backgrounds.Footnote22 It was distributed to Public Affairs Officers at all USIS posts in Europe, Central and Southern America, the Far East and the Near East in December 1957, just a few weeks after the Little Rock crisis.Footnote23 The choice to work with Belafonte was significant. Born in New York to parents of West Indian and Jewish heritage, the light-skinned Belafonte was acutely sensitive to racial distinctions. His political consciousness was shaped in the early 1940s during his time in the US Navy, which enforced a Jim Crow policy of racial segregation. In the later 1940s, living in Harlem, Belafonte was drawn to the anti-fascist politics and the collective ethos of the American Negro Theater and its commitment to address contemporary black life with an integrity absent from the mainstream.Footnote24 Belafonte would carry the political convictions shaped during this period with him throughout his life, whilst at the same navigating the complexities his left-wing associations created for his career as a performer. In many respects, his background might appear to make him unsuited to the USIA’s propaganda purposes. Yet, in other ways, he was ideal for addressing indirectly the growing racial crisis. The inspiration he professed to take from Steichen’s The Family of Man, for example, might be viewed as one measure of his philosophical and aesthetic fit with USIA photography.Footnote25 And his biography and associations could always be edited to avoid controversy.

There was no explicit reference to race or civil rights in the story itself, nor any reference to Belafonte’s own political commitments, but it was self-evidently meant to present the USA as both culturally and racially diverse and harmonious. The notes for the Public Affairs Officer referred to the story as ‘an example of Democracy in action’, a much-used phrase that invoked the USIA’s preferred model of gradual and consensual social change. Belafonte was described as ‘a dedicated student of American work chants, spirituals and folk songs’, but the elisions in the brief biography that accompanied the picture story are equally significant. There was no mention of Belafonte’s politics, nor his close association with figures who had been impugned during the McCarthy period – he had a close relationship with the singer, actor and activist Paul Robeson, whose passport had been revoked several years before in reaction to his support for the Soviet Union. Belafonte was one of several African American performers that the USIA felt added credibility to their message on race and civil rights, and with whom they could work. And Belafonte was prepared to work with the USIA, even if at times he found himself subject to criticism from those he regarded as being on the same side. In March 1956, he had featured in one of the USIA ‘youth packets’, monthly packages of news stories, feature articles and photographs with a specific focus on youth distributed to field posts across the globe; he performed at the 1958 Brussels Fair as part of the US cultural programme; and later that year, whilst on a European tour, he condemned the events in Little Rock at a press conference organised at the US Embassy in Rome.Footnote26

The short text narrated the story of Belafonte’s life and his engagement with folk music, first in Jamaica and then in the USA. The photographs emphasise the youthful enthusiasm and racial diversity of the children at the camp as well as the intensity of Belafonte’s musical delivery, accompanied by Mexican guitarist Hector Acosta.Footnote27 In the opening image, Belafonte is shown surrounded by ‘admiring youngsters’ greeting him on his arrival; on one side of him stands an African American boy, with Belafonte’s arm placed on his shoulder, and on the other side stands a white boy (). The archive file does not include any shooting or editing notes, but one can be confident that this symmetry was carefully chosen. Other photographs show the children joining in ‘songs about railroad workers, coal-miners, farmers and even mischievous donkeys’, and listening intently and responding, as Belafonte ‘told them stories about his own childhood and they told him about their lives and what they hoped to do when they grew up’. The selection presented a diversity of children, white, African American and Asian American.Footnote28 The framing of the story around Belafonte’s engagement with the children mitigates against any accusation that the USIA focused too narrowly on individual African American success, a familiar criticism within the agency at the time, whilst retaining the recognition attached to the singer’s name. Equally, the story enabled the USIA to benefit by association with Belafonte’s public position on civil rights.

Figure 2 Unknown photographer, ‘Belafonte being greeted by a group of admiring youngsters upon his arrival at the Friendship Day Camp near Los Angeles, California’. ‘Vocal Lesson by Belafonte’, 1957. USIA ‘Picture Story’ Photographs, 1955–84, Record Group 306. 306-ST-435-57-24373.

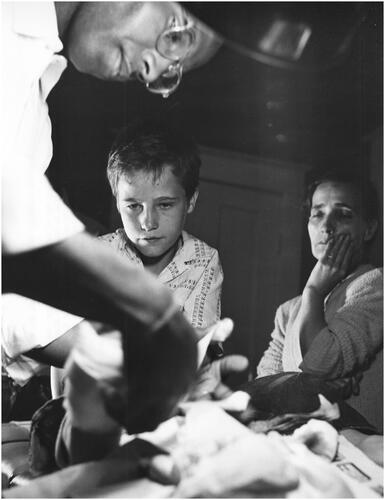

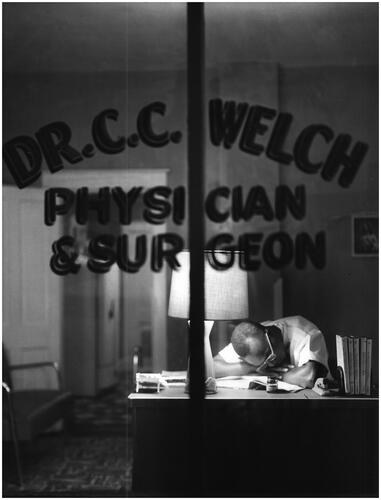

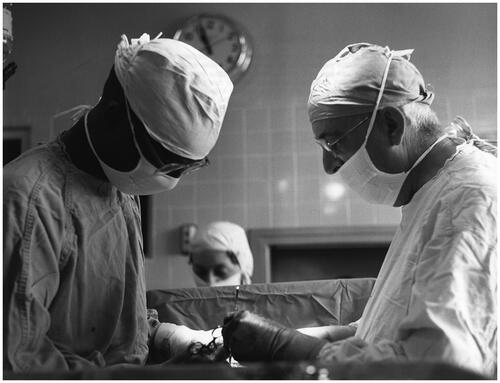

A second picture story illustrates further the shift towards the production of photographic narratives on the lives of ‘ordinary’ African Americans. ‘A Doctor Makes His Rounds’, produced in February 1958, tells the story of Dr Cornelius Calvin Welch, a 32-year-old doctor from Hannibal, Missouri.Footnote29 The theme of the small-town doctor was not new to the US information programme, although this appears to be the first time the protagonist was an African American.Footnote30 It seems likely, too, that the photographer tasked with this assignment was aware of W. Eugene Smith’s celebrated photo-essay ‘The Country Doctor’, produced for Life magazine in 1948; or even his later photo-essay ‘Nurse Midwife’, about an African American woman from South Carolina, published in Life in 1951. Although the USIA story has neither the depth nor intensity that Smith brought to his photography, several of the images suggest that the photographer was influenced by Smith’s photographic style. The strongest image of the sequence is a tightly-framed shot of Dr Welch treating a young white boy who has a cut to his foot – ‘the physician sutured the wound and bandages it, as the mother looks on’ (). This same triad – doctor, child-patient, mother – appears in Smith’s ‘Country Doctor’ series, and the proximity to the action was a mark of his style. Similarly, where Smith sought to convey the arduous life of the country doctor in an image of him laid asleep on an operating table, Dr Welch was captured through the window of his surgery at night, asleep at his desk ().

Figure 3 Unknown photographer, ‘A boy who cut his foot on a nail is treated by Dr Welch. After administering an injection of anti-tetanus serum, the physician sutured the wound and bandages it, as the mother looks on’. ‘A Doctor Makes His Rounds’, 1958. USIA ‘Picture Story’ Photographs, 1955–84, Record Group 306. 306-ST-460-58-24398.

Figure 4 Unknown photographer, ‘The life of a young doctor is arduous. Here, after a long and tiring day, Dr Welch naps at his office desk’. ‘A Doctor Makes His Rounds’, 1958. USIA ‘Picture Story’ Photographs, 1955–84, Record Group 306. 306-ST-460-57-24393.

This picture story was more than a humanist paean to its central character, however. It was intended to convey a precise message about racial equality and integration. As with Belafonte, the integration theme was carried implicitly through the visual narrative rather than stated directly in the text. Neither the racial identity of the doctor nor his patients are mentioned in the short text or captions. The notes for the Public Affairs Officer, however, were more candid, describing the subject as a ‘Negro’ doctor and referencing the fact that he had ‘both white and Negro patients’. The protagonist’s standing in the community was reinforced in the short text accompanying the photographs, which referenced his service in the US Air Force during the Second World War and the status of his siblings: a law student, a post office employee and a schoolteacher. The reader was meant to understand that his record of achievement and public service was not exceptional for an African American. The photographs picture the doctor in a variety of work settings, establishing his status and the equality and naturalness of his interactions with patients and work colleagues. The fifth image in the sequence shows Dr Welch with another (white) surgeon delivering a child by caesarean section; the absolute symmetry of the composition, heads precisely level on either side of the frame, signifies their equal standing (). Another similarly framed image shows Dr Welch in conversation with the head nurse at the hospital. The caption states that they are discussing medical charts, although the photograph suggests a more relaxed moment of conversation between the black male doctor and the white nurse, moderating to some degree the purely professional nature of the relationship – the soft lighting gives an almost romantic feel to the image. Several images show the doctor with his patients, both white and black. In one, the doctor stands over an older white woman holding her fractured wrist in his hand in order to assess how well it was healing. Those making the selection for the picture story would have been fully aware of the interracial character of this gesture of care and its symbolic significance.

Figure 5 Unknown photographer, ‘Dr Welch (left), with the assistance of another surgeon, delivers a child by Caesarean section’. ‘A Doctor Makes His Rounds’, 1958. USIA ‘Picture Story’ Photographs, 1955–84, Record Group 306. 306-ST-460-58-24397.

At the same time as it was developing these picture stories, the USIA was working out its long-term response to the events at Little Rock. One year on from the crisis, the agency was better prepared to face the challenge of a new academic year that promised to generate further coverage of desegregation in schools in the national press of many countries to which its message was directed. In the intervening months, several photo-essays had been produced charting the progress towards integrated schooling across several Southern states, and in August 1958 the agency issued a substantial package of photographs and text to all USIS offices under the title ‘“We Affirm Our Intention” – Desegregation 1958’.Footnote31 The material in the package had a modular structure that would enable individual field posts to adapt the content to suit local circumstances and opportunities.

‘We Affirm Our Intention’ – the title came from the Washington, DC, Board of Education’s 1954 Statement of Policy – was intended to communicate three central ideas to its audience. First, that the implementation of the Supreme Court decision of 1954 represented the will of the majority of US citizens. Second, that there was ‘sufficient evidence’ to identify what was described as an ‘incipient alteration’ in the social structure of the American South, demonstrating ‘an earnest beginning toward elimination of racial segregation’. Third, that ‘through the orderly and democratic processes of law’ the will of the majority would ultimately be successful. In both words and photographs, the package contained much that was familiar. Nevertheless, in explicitly addressing these extended photo-essays to the anticipated struggles of the coming school year, the USIA acknowledged a need to deal head-on with an issue that was continuing to garner unfavourable headlines overseas.Footnote32 The covering memo cited Arlington, Charlottesville, Newport News and Norfolk as cities expected to be in the news when schools opened in September, following desegregation orders. It was now patently clear that the problem would not submit so easily to the more general and implicit approach that had characterised earlier periods. The plea for patience and understanding on behalf of segregationist Southern states faced with ‘a revolution in the entire, long-established social pattern’ was nothing new of course, although it did fit well with the USIA strategy of locating the problem of racism in the South and presenting the federal government as the promoter of civil rights.

The package contained four extended photo-essays: the title story ‘We Affirm Our Intention’, on the school system in Washington, DC; ‘How Segregation Patterns are Changing in One Southern State’, focused on North Carolina; ‘Desegregation in Reverse’, a story on West Virginia State College, a formerly African American college now admitting white students; and ‘The Measure of Progress’, reporting on Clinton High School in Tennessee, which had been the site of a tense and at times violent struggle. Ironically, the lead story made use of the iconic Little Rock photograph of federal paratroopers escorting students up the school steps as a symbol of US government commitment at the same time as the accompanying memo informed Public Affairs Officers that Little Rock itself did not feature in the coverage of progress, since desegregation there had been suspended following a district court ruling earlier that year. There was irony, too, in the choice of Clinton High School. The narrative of the piece sought to project both the guiding influence of federal authorities – one photograph shows the County Attorney reading to an assembled hall of students the Federal Court injunction ‘forbidding anyone to interfere with the desegregation of the school’ – and white students’ commitment to integration. The claim that ‘there have been no further incidents’ proved to be overoptimistic, however. Just a few weeks after the package would have arrived in overseas posts, the school was the subject of a bomb attack by white supremacists opposed to desegregation, showing the risks for the USIA in placing such cases at the centre of its coverage.Footnote33

Among the images included in the package were the agency’s customary depictions of integrated school classrooms and libraries, and formal photographs of mixed groups, including sports teams, military training corps and graduating cohorts. The lead story included a portrait of six female classmates – three white, three black – at their graduation from Roosevelt Public High School. To affirm the personal commitment to integrated schooling at the highest levels of government, the caption noted that the white student third from the left was the daughter of the then US Secretary of Agriculture. The school enrolment is ‘65% Negro and 35% white’, the reader was told. More significantly, the selection gave greater attention to interracial interactions outside formal classroom settings than had hitherto been typical. A female African American student is shown chatting casually with her white colleagues on the steps of their dormitory at Warren Wilson Junior College, Swannanoa, North Carolina; at the same college, a group of students are shown having an ‘informal get-together’ at the Dean’s house; and a group of female students at West Virginia State College are seen together chatting and smiling whilst they set their watches by the college sundial. Even the photographs of sports, a favourite USIA theme in relation to race, emphasised the close physical interaction of black and white students; as, for example, in an image of a water polo game at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill in which an African American student leaps out of the water above his white opponent. ‘Desegregation in Reverse’, a photo-essay that overconfidently tried to normalise integration by presenting it as a process that operated in both directions, made the point directly in its master caption: ‘At the college white and negro students live together in the dormitories, serve together as student leaders, participate together in athletics, and join the same social fraternities and sororities’. One further image underlines this new emphasis. The photograph shows two African American students and a white colleague at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill casually sharing a coffee standing at the counter of the campus coffee shop (). Although it would be a few years before lunch-counter protests came to the fore in the coverage of civil rights and desegregation struggles, the inclusion of this image more than most suggests that the USIA was beginning to deepen its photographic engagement with the theme of ‘racial etiquette’.Footnote34 As it sought to project its message overseas, the agency was beginning to find itself confronted with a much wider visual repertoire of images critical of racial injustice in US society than the symbolic image of lynching which its coverage sought to refute. As photographs of struggles against school segregation and Jim Crow laws circulated internationally, they became of necessity something with which the USIA had to engage. Photographs showing formal handshakes between African Americans and their white counterparts might have sufficed to provide ‘visual evidence of implied social equality’ through much of the 1950s, as Schwenk-Borrell argues, but this was no longer the case.Footnote35 The micro-politics of racial interactions and their visual representation became an increasingly self-conscious dimension of USIA photography as it sought to imagine an integrated US society for its international audiences.

Figure 6 Unknown photographer, ‘Three University Students at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, chat between classes in a campus coffee shop’. ‘How Segregation Patterns are Changing in One Southern State’, August 1958. Office of the Assistant Director for Africa, Country Files, 1953–61, Box 11, Record Group 306. [Declassified Authority: NND48600]

![Figure 6 Unknown photographer, ‘Three University Students at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, chat between classes in a campus coffee shop’. ‘How Segregation Patterns are Changing in One Southern State’, August 1958. Office of the Assistant Director for Africa, Country Files, 1953–61, Box 11, Record Group 306. [Declassified Authority: NND48600]](/cms/asset/eb8d4ef6-c550-4b88-bea7-2faa6db52c43/thph_a_2323310_f0006_b.jpg)

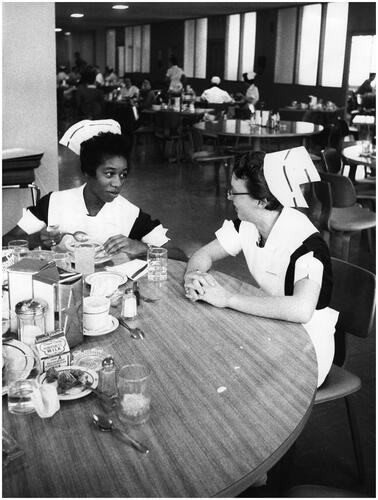

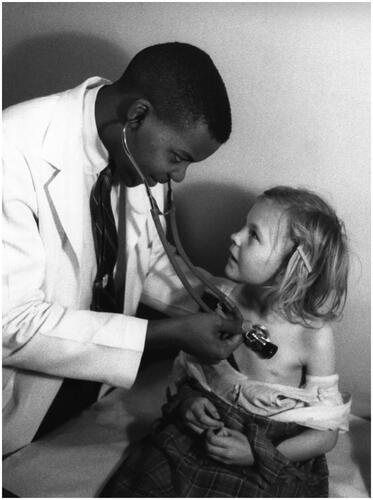

Further evidence of this emphasis can be found in another photo-essay from 1958, on the Southern State Medical School, located in Little Rock, Arkansas.Footnote36 Although not included in the aforementioned package, the story was plainly a means of talking about the Little Rock crisis to international audiences, without dealing specifically with Little Rock Central High School. Here, integration was explicitly acknowledged as a central theme. The photo-essay tells the story of the medical school, ‘where Negro and white students have been working side by side in classrooms, laboratories, hospital, clinic and other facilities for the last nine years’. It is striking that all but one of the eight photographs depict scenes of close interracial interaction, often informal and unrelated to the specific role of a medical student. The opening image, for example, shows a white student lighting the cigarette of his African American colleague during a break, an act of equality and friendship. Another image shows a black student nurse at a table eating her lunch in the cafeteria, seated beside a white colleague (). Here, however, the empty space in front of the white nurse, on an otherwise cluttered table, creates a dissonant note, an element of photographic contingency that disturbs the careful staging typical of the agency’s approach.Footnote37 This sense is reinforced if one enlarges the image, when it is possible to see a woman in the background with her head turned to watch the unfolding performance. In the course of their work, a black female student and a white female student are shown together injecting a parakeet egg with tumorous tissue as part of a cancer research programme. Notably, the black student stands over observing her white colleague. Also, in the final image of the sequence, a black student applies his stethoscope to the chest of a young white girl who looks up at him with an expression of trust on her face, symbolic of doctor–patient relations and hierarchies (). The overall impression created by the picture story is of an attempt to displace the images of racial conflict and violence associated with the town of Little Rock by visualising an imagined future of better healthcare and racial harmony.

Figure 7 Bern Keating, ‘Student nurses, medical trainees and other members of the hospital staff usually eat in the Center’s cafeteria to save time and money’. ‘Southern State Medical School: Arkansas University Starts Tenth Year of Integrated Medical Training’, 1958. USIA ‘Picture Story’ Photographs, 1955–84, Record Group 306. 306-ST-468-58-4200.

Figure 8 Bern Keating, ‘A senior student specializing in paediatrics examines a small patient in the clinic’. ‘Southern State Medical School: Arkansas University Starts Tenth Year of Integrated Medical Training’, 1958. USIA ‘Picture Story’ Photographs, 1955–84, Record Group 306. 306-ST-468-58-4225.

Little Rock had begun to acquire a symbolic place in USIA coverage of racial integration, and this would not be the last time the agency commissioned photographs to be made in the city.Footnote38 For the moment, however, I want to turn attention to the photographic treatment of racial integration that began to take shape in its wake and in the context of the agency’s deepening engagement in Africa.

* * *

As the decade ended, the perception within the US government was that not only were incidents of racial discrimination damaging its image abroad, but that their impact was especially keenly felt in the emerging nations of Africa and Asia. A report by the Department of State in early 1959, produced at the behest of the Civil Rights Commission, concluded that the ‘net effect of racial discrimination in the United States on public opinion abroad is definitely adverse to our interests’, and particularly so in Africa and Asia, ‘where a sense of self-identification is involved […] linked with the presence or recent memory of white colonialism and domination’.Footnote39 The report cited a resolution condemning racial segregation adopted by the first Conference of Independent Africa States in Accra in 1958, describing it as ‘typical of the continuing concern with this question’. Furthermore, it noted that the Soviet Union was intent on using the racial situation in the USA as part of a strategy to appeal to African and Asian delegates at the United Nations, pointing out to them that ‘in the country in which the United Nations was meeting, “people of their color are being persecuted”’. More positive, from the US perspective, was the fact that despite what was described as the ‘sensationalistic exploitation’ of individual incidents, it nevertheless detected amongst its African and Asian audiences a growing awareness of progress in race relations, and an ‘appreciation of the problems involved and the efforts being made to solve them’. This latter point sounded rather like an endorsement of the information strategy then being pursued at the USIA.

The establishment of an Africa Office at the USIA in 1960, accompanied by an increased budget and a rapidly expanding number of field posts on the continent, led inevitably to a growing demand for coverage that was better targeted at African audiences. The programme that the USIA developed to fulfil its new role in Africa was multifaceted but, given the prominence of racial integration and civil rights, it is unsurprising that it was accorded an important place. Despite the attention the USIA had given to the issue since Little Rock, however, it would soon be clear that from the perspective of the Africa operation there was more to be done. The archive contains relatively few programmatic statements concerning photographic production for Africa, so it is necessary to track the expansion and retuning of the agency’s output to meet the demands of African field posts through photographs and picture stories and their accompanying documentation. Nevertheless, there were a few occasions when officers set out their thoughts more systematically. One such example was composed by Carroll Foster, Public Affairs Officer for USIS Monrovia in Liberia, and sent to USIA Washington in March 1962.Footnote40 It appears to have been accorded some significance on its arrival as it was marked for distribution to all of the internal divisions of the USIA as well as the Department of State, the National Security Agency, the Central Intelligence Agency and the Office of the Secretary of Defense. Foster’s critique of USIA coverage was twofold: it was too impersonal and too general. The premise was that audiences outside Western Europe had at best a ‘severely limited’ knowledge of African Americans. To date, Foster contended, the USIA had provided little material that went ‘beyond a mere nebulous concept based on familiarity with a few outstanding individuals and situations’, and certainly nothing that offered ‘a working insight into the daily lives and aspirations’ of the majority of African Americans. In its efforts to present an overarching narrative of African American progress since slavery, and to emphasise the commitment of white citizens to the elimination of inequality, the agency had neglected to answer a more fundamental question: ‘Who is the Negro American?’ The existing output was criticised for relying too heavily on the statistical description of African American social advancement or exceptional individuals – ‘Endless feature stories about the less than one percent who are pronounced successes’. Staff in Washington may have felt, with some justification, that this latter observation was not new, and that the agency had made deliberate efforts to move away from this approach. Nevertheless, the conviction with which Foster outlined the failure of existing output to ‘make emotionally understandable the changes in human beings that measure true progress’ made for a compelling statement. Existing coverage, it was claimed, could not ‘explain or explore the motivations of a child of a Negro field hand who becomes a teacher’, or ‘the struggles of an individual family, and the surrounding circumstances which made possible their slow educational rise from illiteracy to primary, secondary and college education in as many generations’. Nor did it convey, ‘the innumerable small personal commitments to democratic ideals which make the national actions against racism possible’, or ‘the subtle changes in attitude that can occur in the classroom or military service which reverse many patterns of thought held for decades’. Giving the argument greater weight was the assertion that it was based on an extensive analysis of material dating back to 1958, including six films and ten booklets, along with numerous newspaper and magazine pieces and agency releases.

An over-riding ‘national sensitivity’ on the issue of race had resulted in the agency treating the issue with ‘too much delicacy’, it was claimed. In response, Foster proposed that the agency reorient its coverage to provide an ‘intimate and particular portrayal’ of the African American middle class, its ‘most logically representative segment’ and reflective of ‘the present and the immediate future’. The proposal called for ‘an intimate and detailed look at the actual lives of many average individuals’, enabling ‘a people to tell their own story in its most basic terms’: ‘to show closely, as present material has almost never done, the individual Negro as he actually is; pursuing varied occupations, engaged in community activities, fighting the hourly battle against inequality, educating his children, at worship, at play, participating in the arts, and just being the average man about the house’. Foster may have been pushing at an open door. If the USIA did not entirely eschew the use of prominent figures, statistics or the extended narrative, nevertheless, over the next few years there was considerably more attention paid to the experience of ‘ordinary’ African Americans and a more personal and intimate quality to their portrayal. This was a marked difference from the visual coverage that had been typical in the 1950s, and although it cannot be exclusively attributed to the perceived needs of audiences in Africa, the evidence suggests it was an important factor.Footnote41

It seems unlikely that Foster’s was a lone voice. In February of the following year, Edward Roberts, Assistant Director for Africa, felt sufficiently concerned about the material available for circulation across the continent that he wrote to USIA Deputy Director Donald Wilson.Footnote42 His central complaint was ‘the failure of Agency output to pay enough attention to the task of projecting an integrated American society’. The memo referred to the fact that ‘top officials’, among them the Attorney General, a post then held by Robert F. Kennedy, had stated that ‘racial issues are of primary importance overseas’, and that consequently ‘no serious effort […] on any theme or campaign should fail to take this task into account’. According to Roberts, this was not being done, as had been demonstrated on several occasions, including when, for the first time, he managed to get some of the agency’s stock posters printed with African language text – ‘one on churches of America and another on American agriculture’ – in ‘neither … was there a single non-white face’. He emphasised that he was not referring to the ‘encouraging flow of materials on the progress of American Negroes which is of direct interest to the African posts’, but rather ‘a failure to project world-wide, in a constant “soft sell” manner, the basic idea of an integrated society in which non-whites are playing an increasing role’. Roberts was keen that this should not be seen as an Africa-only issue and wanted to avoid accusations that he represented a ‘partisan viewpoint’.

Whether or not the aforementioned represented critical interventions in internal agency debates, coverage that followed in the middle years of the decade reflected the concerns they expressed. One can find photographs in the archive of virtually all the subjects outlined in Foster’s description. Not only is it clear that a desire to represent the USA as a racially integrated society permeated USIA photography, but it is also evident that many of the picture stories illustrating the theme of integration were the result of specific requests from the Washington-based Africa branch, or in some cases individual African field posts overseas.Footnote43 If the magnitude of the racial challenges facing US society seemed justification enough for their coverage, nonetheless the visual record created by the US government was shaped, at least in part, to represent the domestic situation for audiences in Africa. It is instructive to look at some examples that illustrate the direction coverage took as the decade unfolded.

A picture story from 1963 – ‘First Negro Astronaut Candidate’ – illustrates this shift, bringing the theme of racial integration into coverage of the space programme, which had become a central focus of Cold War propaganda since the Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957.Footnote44 In the early 1960s, as NASA began to send men into space, staff at the USIA recognised the propaganda value of having an African American as part of the space programme. The agency had already begun to produce coverage of space exploration for African audiences when its director Edward Murrow raised the issue of a black astronaut directly with President Kennedy, initially without success. In 1962, frustrated by the lack of a receptive audience at NASA, the agency hired two black lecturers to tour schools and universities on the continent giving presentations on the space programme.Footnote45 The USIA continued to push the idea enthusiastically and agency staff sought to supply Murrow with evidence to support the case. In August 1962, Acting Assistant Director for Africa, Lawrence Hall, addressed a memo to Murrow with the subject line ‘Racial Discrimination – Astronaut’. ‘Should you have the opportunity to re-open the case for a Negro astronaut’, he wrote, ‘you might wish to mention that on July 31 this lack in our space program was pointed up in a Radio Moscow broadcast in Hausa beamed to Africa’.Footnote46 In parallel, the agency was pressing for the Air Force to play a similar role by ‘assigning to its Africa flights an adequate complement of Negro officers as pilots, navigators and other crew members’, arguing that this ‘would be particularly effective […] on flights that touch down in areas of maximum exposure to African observers’, with the potential to ‘make vividly convincing in flesh and blood a point we’re trying to make in disembodied words and pictures’, a comment that reveals a performative conception underlying its visual programme on racial integration.Footnote47 It was patently obvious, however, that the symbolism of a black astronaut would be of a different order.

The agency’s prayers were answered in 1963 when Captain Edward J. Dwight, Jr was announced as one of a cohort of sixteen candidates entering the Aerospace Pilot programme at Edwards Air Force Base, California, completion of which would open the possibility of his selection for space flight. Unsurprisingly, Dwight’s acceptance onto the programme attracted considerable coverage in the mainstream media as well as being a bonus for the USIA. He was soon being widely celebrated in African American publications such as Ebony and Jet, as well as Life, raising expectations that he would be joining the likes of John Glenn in orbit. Although Dwight would never make it into space, the agency had its story. A readily available template existed in the coverage of the Mercury Seven – the first astronaut group – published in Life magazine. In 1959, sanctioned and overseen by NASA, the astronauts and their wives had signed a contract with Life for a series of exclusive profiles.Footnote48 Over several years, the features created an intimate portrayal of the astronauts and their ‘all-American’ families, presenting them to the US public as ‘patriotic symbols’; or, seen from a more critical perspective, as ‘bland good guys’ – ‘deodorized, plasticized, and homogenized’.Footnote49 Agency staff would have been familiar with the way in which this first astronaut cohort had been represented in print. Dwight was to be accorded similar treatment, albeit on a smaller scale.

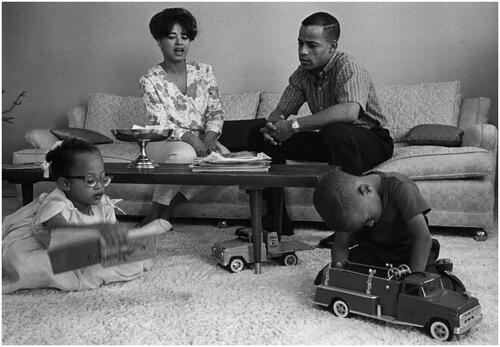

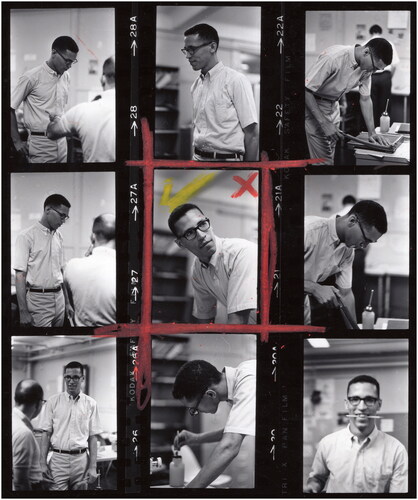

The picture story on Dwight was commissioned from photojournalist Don Cravens, best known for his photographs of the Montgomery Bus Boycott of the mid-1950s, an indication perhaps that the USIA sought to draw on a cohort of photographers with greater insight into African American life in the USA. It was relatively short, consisting of just five photographs and fewer than three hundred words. Although clearly of relevance to African posts, this was not a specific Africa branch request; the story was marked for distribution to all regions. The text provided a short personal portrait, noting that Dwight had grown up near Kansas City airport, where his dream of becoming a pilot was born. The biographical narrative then relayed his success in sport, as a track athlete and in the boxing ring, and education, graduating with a degree in aeronautics from Arizona State University, before becoming a pilot and subsequently instructor at Williams Air Force Base, Arizona. The piece concluded by informing the reader that he ‘is married to his childhood sweetheart and is the father of two children’. The photographs show Dwight at the base undertaking a training flight, discussing a mission with two of his white colleagues, studying in class and seated in a flight simulator. But it is the final image in the sequence that is most significant, picturing him at home in his living room ‘spend[ing] a quiet evening with his family’ (). The photograph file contains several contact sheets, including a complete roll of film devoted to the living room scene, and further photographs of Dwight and his son Eddie assembling a model jet plane. The portrayal of Dwight at home as a busy father and loving husband, which was echoed in an Ebony profile published in July 1963, points to an important transformation in the treatment the USIA gave to African American figures. Although the agency would continue to select public figures and notable successes to illustrate African American advancement and entry into previously white-dominated fields, the personal narrative and human dimensions would be a central feature of future coverage.

Figure 9 Don Cravens, ‘In the living room of his home at Edwards Air Force Base, California, Edward Dwight spends a quiet evening with his family. From left to right, daughter, Tina, seven years old; his wife, Sue; Captain Dwight; and son, Eddie, five, who wants to grow up to be a pilot’. ‘First Negro Astronaut Candidate’, 1963. USIA ‘Picture Story’ Photographs, 1955–84, Record Group 306. 306-ST-797-63-2940.

The profile of Dwight frames two central concerns that would shape USIA photography over the next few years as it developed its coverage of black America for export to Africa: a deepening attention to the choreography of racial interaction; and the humanising of African American figures. This is evident in a swathe of photographs and picture stories that emerged during the middle years of the decade as the agency expanded its coverage of racial integration.

* * *

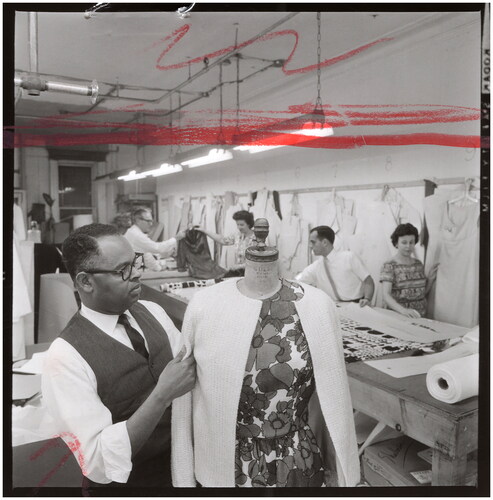

In the 1950s, at least as far as African American culture was concerned, US cultural diplomacy was dominated by jazz, presented as a folk cultural form ‘that springs directly from the American soil’, and gospel, primarily in the figure of Mahalia Jackson.Footnote50 By the 1960s, however, the USIA was keen to portray African American involvement across a much wider cultural field. At the same time as the profile of Dwight was being produced in California, for instance, USIA staff photographer Joseph Pinto was assigned to photograph New York fashion designer Wesley Tann, to illustrate a feature planned for African distribution.Footnote51 The shooting script specified a photograph of the designer ‘at a long work table with two or three of his workers (white and Negro) with bright print fabrics spread over the table’, along with another of Tann on his own ‘fitting a partially made dress (of light material) on a dummy figure’. If the latter image was intended ‘to illustrate his designs in process of being made and the completed product ready for sale’, the former signified the harmonious integration of the workplace and the naturalness of the black designer’s oversight and leadership (). The brief requested details of Tann’s ‘personal background’, the number of black and white workers at the firm and the size of the US fashion industry, ‘an estimate, if possible, on the number of Negro designers or a quote from a fashion source on “an increasing number of Negroes, etc.”’. In respect of Tann, the caption information described him as ‘a farm boy’ from North Carolina who had become a ‘national figure as a dress designer and manufacturer’. Far from being a one-off, this assignment was part of a trend that would see the production of photographs and picture stories on numerous African American artists, cartoonists, writers, actors and playwrights, photographers and classical musicians. In 1963, the artist Charles White was the focus of a picture story prepared for African audiences, albeit he was described as a ‘gifted Negro artist’, a phrase that sounds both patronising and contains primitivist overtones.Footnote52 The text emphasised his life narrative, moving to the South Side of Chicago from Mississippi as a child, and suggested that ‘his stock of ideas still grow out of his early roots’. There is not space here for a more detailed analysis of USIA coverage of black art, but it is worth noting that the framing of White’s profile suggests the agency was at this point still struggling to find a voice with which to speak to its African audiences that was different from speaking to white Europeans. Later material, on the other hand, did at least begin to convey a sense of speaking to African readers who were serious about black art and literature.Footnote53 As Jaji points out, this was a period when ‘the cultural field became an increasingly important locus for global black consciousness’.Footnote54 The point was not lost on the USIA, who were increasingly conscious of the need for a more sophisticated approach to African reading and viewing publics taking shape across the continent, even if their initial efforts may have been somewhat inept.Footnote55

Figure 10 Joseph Pinto, ‘Wesley Tann, New York Designer at Work’, 29 May 1963. Staff and Stringer Photographs, 1949–69, Record Group 306. 306-SS-14-759.

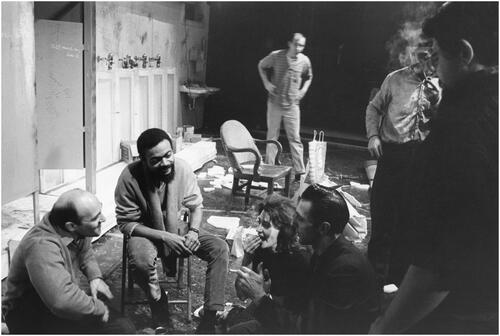

As its coverage evolved, the USIA did not limit itself to figures who had a benign view of American democracy and its capacity for racial justice. LeRoi Jones was photographed in December 1964, whilst rehearsing The Slave and The Toilet at St Mark’s Playhouse in New York, both plays that explored racial tension and violence in US society.Footnote56 A photograph of the rehearsal was used as part of a short photo-essay on the first African American president of the Actors’ Equity Association, Frederick O’Neal ().Footnote57 Intriguingly, the text of the piece sets up a tension by juxtaposing a quote from James Baldwin, who was also pictured – ‘A whole army of people from whom one has never heard, most of them black, are finding their voices and changing our consciousness’ – with one from an unnamed ‘Negro actor’ talking about Jones – ‘He’s still doing “Negro” plays aimed at a white audience. When he can write for both races, he’ll be our great writer’. Through the decade, picture requests for African dissemination generated coverage of African American engagement across both popular and high cultural forms, from the cartoonist Morris Turner, creator of Wee Pals, a comic strip with an integrated cast of characters first published in the Chicago Defender, to Henry Lewis, identified as the first African American to lead a major US orchestra when he became head of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra in June 1968.Footnote58 The latter was scheduled for inclusion in the July edition of a widely distributed African poster series ‘Pictures in the News’.

Figure 11 Unknown photographer, ‘LeRoi Jones, important new talent in the American Theater, shares a lunch break with the producing staff on the stage of this play, The Toilet. His writing is often shocking, brutal, nightmarish and obscene’, 1964. ‘Other “Firsts” in New York Theater World’, Photo Bulletin, 1964–73, Box 1, Record Group 306. 306-N-65-387.

After 1965, when the USIA launched Topic, an illustrated magazine for sub-Saharan Africa, coverage of African American culture became a regular feature, with profiles of African American actors, writers, musicians and artists, such as James Baldwin, Diana Sands and Gordon Parks, presented alongside African counterparts, including South African exiles Miriam Makeba and Ezekiel Mphalele.Footnote59 The photographer Gordon Parks was an important figure for the agency; viewed as a cultural success story, he was profiled on more than one occasion in agency publications. His sophisticated photographic record of black America, which appeared on the pages of Life magazine, will almost certainly have informed an understanding of the African American experience and how it might be pictured for international audiences among agency staff, even if they inevitably faced political constraints. The USIA also promoted African American photographers specifically for African audiences. An exhibition of the work of Gordon Parks, Adger Cowans and Richard Saunders was organised in conjunction with Magnum’s Dennis Stock for the first Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres in Dakar in 1966. USIS Dakar described the exhibition as of considerable interest to ‘the leading Africans with whom we are dealing in our program’. Its positive reception generated requests for additional versions to be made available for touring, following the model of The Family of Man.Footnote60

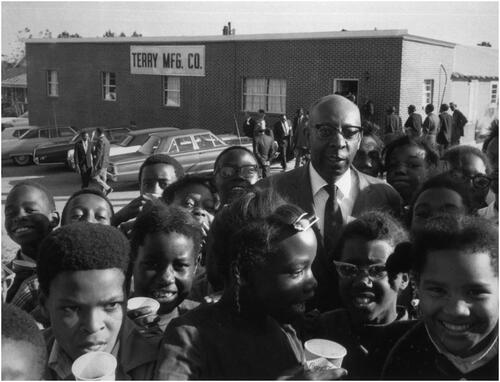

Equally, the USIA extended its coverage of African American advancement within the US economy. An Africa branch request from 1965 prompted an assignment to photograph Henry Green Parks, Jr, founder of the successful Parks Sausage Company, at a packing facility in Beltsville, Maryland. In one image, the light-skinned Parks is shown in discussion with a darker-skinned black colleague standing in front of stacked boxes of sausages, the latter’s presence a concession perhaps to demands for the visibility of dark-skinned African Americans in agency output.Footnote61 Demonstrating that black business success was possible in the South as well as the North, a later four-page photo-essay profiled Jesse A. Terry, a garment manufacturer from Roanoke, Alabama.Footnote62 The narrative credited Terry with reviving a depressed local economy and enabling ‘a new life for many citizens once welfare recipients’. The photographs show him as guest of honour at a celebratory lunch, possibly the first such occasion ‘at which a black man was so honored by an all-white Chamber of Commerce in the rural South’, the narrator speculated. Outside the factory, Terry was pictured being ‘mobbed by youngsters who toast the town’s benefactor with soft drinks in paper cups’, presenting a positive image of African American youth and community in the context of the later 1960s ().

Figure 12 Unknown photographer, ‘Outside the plant, Terry is mobbed by youngsters who toast the town’s benefactor with soft drinks in paper cups’, 1969. ‘A Party of Praise for A Small Town’s Big Man’, Photo Bulletin, 1964–73, Box 2, Record Group 306. 306-N-69-3495.

Neither did the USIA focus exclusively on business leaders. In what could almost be a direct response to Carroll Foster’s plea for coverage of middle-class African Americans, including the ‘average man about the house’, a 1968 assignment specified photographs ‘to cover at-home and at-work activities of a Negro family in Washington’.Footnote63 The request came from USIS Pretoria for use as a small feature in an unspecified daily newspaper. Selected for the story were Leroy Copeland of the Internal Revenue Service and his wife Ethel Copeland who worked at the Department of Agriculture, described as a ‘pretty typical’ Washington family; government employees, homeowners and married with children. The caption noted that the couple went to the same high school and met on a church outing; and that the husband had studied at a business college in Washington. The photographs document the couple in the course of their work, including the husband’s second job at a funeral parlour, and in domestic settings, cooking, cutting the children’s hair and helping them with homework. The shooting script specified two scenes of Mrs Copeland at work: a medium or long shot of her working at her desk ‘showing her white colleagues in near background’; and a close-up of her ‘bringing some material to her supervisor’. Significantly, the latter image was not included in the final selection. The photographer had taken several frames including the supervisor positioned standing above the seated Mrs Copeland. In his analysis of this assignment, Natanson speculates that this exclusion may have been because ‘the proximity of the two in the pictures was judged too close for South African standards’ or that ‘images of a white supervisor standing over a black employee’ ran counter to the emphasis on equality that was key to USIA treatment of interracial interaction. The latter explanation seems more likely.Footnote64

The expansion of coverage in new directions did not come at the expense of more familiar themes of democratic representation and school integration, however. The USIA regularly produced picture stories on African Americans advancing within local democratic structures, which sought to normalise the idea of integration as a gradual process with goodwill on all sides. ‘Town Councilman, Small Town, USA’ is a typical example: an extended portrait of Wilmer Porter in the town of Dumfries, Virginia, an African American car mechanic whose ‘reputation as a businessman and good neighbour’ underpinned his successful election to the town council, by a largely white electorate ().Footnote65 The photographs show him at home, at work, around town and in council meetings, unfailingly at ease with his fellow citizens, white and black. Notably, the issue of integrated lunch counters was picked up in the narrative: ‘Mr Porter won even more respect when he and his wife, an attractive schoolteacher, asked the manager of the local drugstore to end his policy of not serving Negroes at the lunch counter’. In an effort to situate the central character’s experience within a generational narrative of progress, the story included a framed portrait of Porter’s formerly enslaved great grandmother, who had taught ‘many whites’ to read. As with the coverage of black arts and culture, in the middle years of the decade one can discern the emergence of a more serious effort at documenting genuine black political power. To its African audiences, this may have been a more meaningful alternative to set against the homely, and no doubt for many unconvincing, image of racial integration in small town America exemplified by the earlier story, which itself harked back to postwar photo-essays on American democracy, albeit now with prominent African American characters.Footnote66 Or preferable to the more idiosyncratic stories that came to the agency’s attention through the mainstream media, such as one on the white Mayor Arthur J. Holland of Trenton, New Jersey whose commitment to racial integration led him to move into a majority black neighbourhood of the city.Footnote67 For the USIA, the latter offered an irresistible reprise of its ‘desegregation in reverse’ theme.

Figure 13 Unknown photographer, ‘Ask anyone in Dumfries, Virginia, where to find the best autobody repair service and he will send you to Wilmer Porter, owner-manager of Porter Bros. Although Mr Porter is a Negro, he is so respected by his fellow-citizens – both white and Negro – that they elected him to the Town Council’. ‘Town Councilman, Small Town, USA’, 1964. USIA ‘Picture Story’ Photographs, 1955–84, Record Group 306. 306-ST-863-64-411.

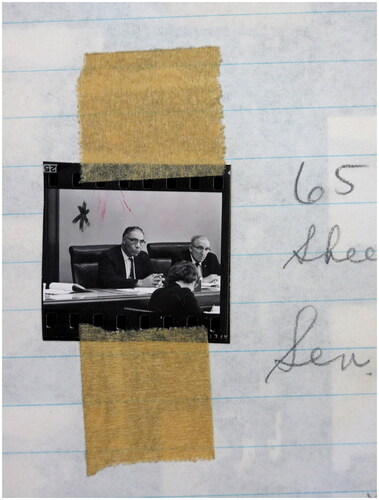

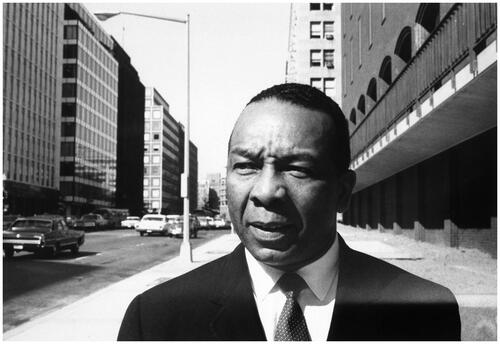

In 1965, the USIA prepared a series of six single photograph profiles of African American politicians ‘illustrating the role of the Negro in elective office in the United States’ for distribution to all African posts, as well as wider circulation as part of a regular civil rights packet. Among the figures profiled was Edward R. Danner, Nebraska State Senator, a former union official in the meat packing industry and chair of the Labor Committee.Footnote68 The photograph selected to accompany the profile presented Danner in a committee meeting (). The image conveys a tone of seriousness, showing him looking out from his position as chair, projecting a sense of authority. The older white male figure sat beside Danner appears physically smaller, a fact reinforced by the angle of the shot; and in the foreground one can see the back of a woman diligently noting down the proceedings, further underlining the authority and importance of Danner’s words. The same year, the agency prepared a photo-essay to show that the ‘progress of racial integration in the United States is possibly nowhere more apparent than at high levels of the government’.Footnote69 Among those depicted were Adam Clayton Powell speaking to a crowd in Harlem and Thurgood Marshall shown being embraced by President Jomo Kenyatta on a visit to Kenya, as well as African Americans who held ambassadorial positions in Dahomey (now Benin) and Senegal. In more extended profiles, the USIA presented figures such as Senator Edward Brooke; Walter Washington, Mayor of Washington, DC (); Carl Stokes, Mayor of Cleveland; and Thurgood Marshall, at the time Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court.Footnote70 In addition to picturing Marshall outside the Supreme Court after the 1954 ruling, and again in 1958 after appealing the delay in its implementation at Little Rock, and with his ‘Hawaiian-born’ wife and children, the 1967 profile reused the image of him with Kenyatta. Although, as Mary Dudziak points out, Marshall’s engagement with Kenya in the years immediately before and after independence may be largely absent from historical accounts that emphasise his impact within the USA, it is evident nonetheless that his potential to appeal to audiences in newly independent African nations was appreciated by the USIA.Footnote71

Figure 14 Unknown photographer, ‘Edward Danner Negro Member of Nebraska State Assembly’, 25 February 1965. Photographs from Staff and Stringer Photographic Assignments Relating to US Political Events and Social, Cultural and Economic Life, 1964–79, Record Group 306. 306-SSA-8-4459.

Figure 15 Unknown photographer, ‘Washington is seen here in his self-proclaimed role of “walking mayor”. He wants to learn people’s reactions at first hand’, 1967. ‘A City and its Mayor Both Named Washington’, USIA Photo Bulletin, 1964–73, Box 1, Record Group 306. 306-N-67-3304.

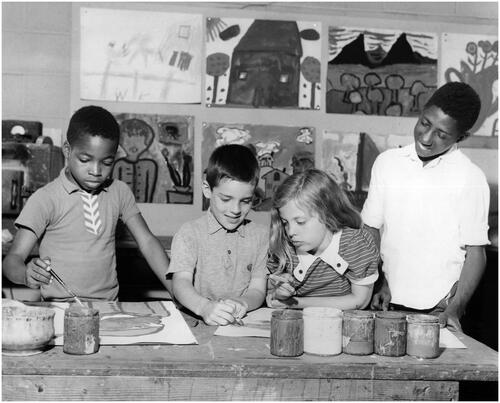

The USIA continued, too, to generate new material on school and youth integration. Examples include a picture story on a voluntary school desegregation programme in Bel Air, Los Angeles, where parents had provided funding for the transportation necessary to overcome the de facto racial segregation by residence; another on an African American editor of a student newspaper at Georgia Tech in Atlanta (); and a set of photographs, requested by the Africa branch, from the Karamu Center, an integrated arts and education centre established in Cleveland, Ohio in 1915.Footnote72 The latter included a photograph of two black boys, a white boy and a white girl absorbed in art-making, which accorded well with the agency’s requirements (), alongside another of a Nigerian visitor presenting a gift to the founders. A later assignment in this vein provides an insight into the movement of picture requests from African field posts to Washington. Prompted by the visit of welterweight boxing champion Curtis Cokes to South Africa in 1968, USIS Pretoria proposed a photo-story be produced on Cokes’ youth club in Dallas, and another on Cokes’ with his family.Footnote73 The memo described the coverage of Cokes’ visit to Johannesburg in the non-white, English-language press as ‘phenomenal’; and stressed that he ‘has acted as an unofficial ambassador for America by creating a tremendous amount of good will among people of all races in South Africa’. The youth club ‘into which he has poured a considerable amount of his winnings’, it stated, had captured ‘the public’s imagination’. During his trip, Cokes called at USIS offices and was ‘photographed signing the Robert Kennedy condolence book’ at the Consulate General, an image that appeared in the black newspaper The World. USIS field officers discussed the proposed photo-essays with Cokes and he agreed to collaborate with the agency once back in the USA. The USIS office planned to place the story on the youth club in Drum magazine and the one on his family in Woman’s World, a supplement to The World. Both publications had a predominantly urban black African readership. In the process of turning the request into a photographic assignment, USIA Washington merged the two stories into a single feature. This was probably in part a matter of convenience, reflecting the modular approach to visual output distributed to field posts – the assignment sheet indicated that they intended to ‘adapt [the feature] for across-the-board distribution in Africa’. More striking, however, is that whilst the memo from Pretoria made no mention of a requirement for racially integrated images, these were an important feature of the instructions for the photographer. For the USIA, the story was not about Cokes as such but, rather, a story about an ‘integrated youth project initiated by [a] Negro American athlete’. Accordingly, the assignment sheet pointed out that the ‘Photos, of course, should show integrated nature of youth club membership and teaching staff’; the ‘of course’ underlining that USIA photographers and editors hardly any longer needed to be reminded.

Figure 16 Unknown photographer, ‘Negro Editor at Georgia Tech’, May 1965. Photographs from Staff and Stringer Photographic Assignments Relating to US Political Events and Social, Cultural and Economic Life, 1964–79, Record Group 306. 306-SSA-44-8019.

Figure 17 Unknown photographer, ‘The Art Department is one of the most popular divisions of Karamu House. Here, the youngsters discover meaning for themselves and in their surroundings’. ‘Karumu Inter-Racial Center’, 17 June 1964. Staff and Stringer Photographs, 1949–69, Record Group 306. 306-SS-52-3371. Reproduced courtesy of Karamu House.

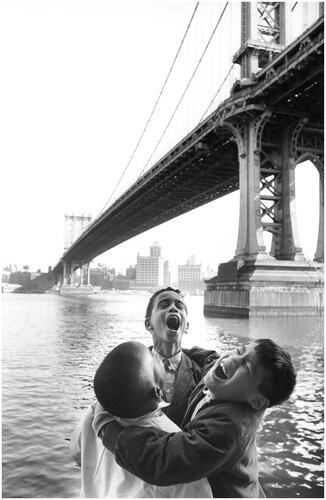

One of the more photographically interesting picture stories on school integration produced during this period portrayed a group of children who attended the same public school in New York, described in the note to Public Affairs Officers as ‘well-integrated’, and ‘a good example of urban renewal, and a happy constructive community life’.Footnote74 The visual narrative tells the story of three ‘inseparable friends’ – Julio, Fred and Douglas – whose parents were Puerto Rican, African American and Chinese, respectively, living in Two Bridges, an immigrant district on the Lower East Side. The boys are shown playing beneath the Manhattan Bridge, at school and in various locations across the neighbourhood (). The title of the picture story – ‘We Three’ – has echoes of the universalism of The Family Man, with its refrain of ‘we two form a multitude’, yet at the same time it breaks with that formula. As Marianne Hirsch points out, in Steichen’s exhibition, with only one exception, the couples are ‘heterosexual and of the same race or ethnicity’.Footnote75 Unsurprisingly, mixed-race couples were not part of the USIA’s visual repertoire, but the insistence on visualising interracial interaction nevertheless marked a departure from the photographic model that had been so influential within the agency.Footnote76

Figure 18 Unknown photographer, ‘Familiar sights to the three boys as they play along the docks of the East River are the Manhattan Bridge and the Brooklyn waterfront shown in the background’. ‘We Three’, 1964. USIA ‘Picture Story’ Photographs, 1955–84, Record Group 306. 306-ST-837-64-356.

Only a small proportion of the archived photograph files contain shooting scripts, but those that were retained reveal sustained and detailed attention to the racial choreography of individual scenes. In February 1967, for example, Ellen Kemper, then picture editor of Topic, requested photographs to illustrate a feature on the phenomenon of the American teenager for its African readers.Footnote77 The article did not have an overt racial dimension, but the notes for the photographer reveal its importance in the ‘symbolic pictures’ that were to accompany the story. To illustrate the point that many teenagers work, staff photographer Yuki King was assigned to make photographs of boys working at the tills and bagging shopping at a supermarket. The Safeway store in Naylor Road, Washington, was identified as employing both black and white teenagers, and King was despatched with the following instructions: ‘the photographer should shoot down the line of checkout counters, showing a row of kids at work. Please ensure that the youngest and most attractive are in the foreground, and that at least two Negroes appear in the foreground’. The photograph that was eventually published framed a black boy and behind him a white boy together forming the centre of the composition.

What comes across from this and many other examples is the sheer pervasiveness of racial integration within the agency’s visual imagination and photographic practices by the later years of the decade. If, in the late 1950s, the USIA was ‘grasping for any positive pro-integration materials it could find to bolster the nation’s image’, within a few years it had created a substantial collection of its own.Footnote78

* * *