Abstract

This article situates the multiple formations of pedagogical hubs that Two-Spirit, Queer, and Trans (2S/Q/T) Indigenous educators co-constitute with the Land of the Spirit Waters (central and south Texas, United States). Through these pedagogical hubs, 2S/Q/T Indigenous educators are re-constituting a Queer Indigenous cosmology bonded intimately with their relationships with the Land, ceremony, community, and other 2S/Q/T people. Guided by these relationalities, they come together to teach, create, and sustain 2S/Q/T Indigenous subjectivities, as, within specific Indigenous communities, gender and sexuality can often be seen in rigid and impenetrable ways. One of these pedagogical hubs is a Queer and youth-led Danza Mexica (Aztec dancing) group in Austin, Texas. In learning with the Land, I co-theorize with the concept of the recharge zone, an area in which Water runoff accumulates within a particular region, fills the aquifer below, and later emerges as springs that give life to the area. I argue that 2S/Q/T Indigenous people are mirroring these geological processes because their acts of gathering, much like a recharge zone, give life to a region marked by cis-heteropatriarchy and the enduring remnants of settler sexualities. Thus, the process of (re)charging Queer Indigenous zones presents multiple registers of epistemology and learning with the Land and demonstrates how 2S/Q/T Indigenous people co-create and fortify dreams, stories, experiences, and futures that have always already been Queer.

The narrative arc of these stories of two-spirit people is really about journeying along a circular path. It is our nature to be whole and to be together. We are born into a circle of family, community, living creatures, and the Land. Our encounters with racism, homophobia, and sexism may disturb our balance, and we sometimes lose our place in the circle. For those of us who lose our place, our traditions, history, memories, and collective experience of this world will still guide us. Two-spirit identity is about circling back to where we belong, reclaiming, reinventing, and redefining our beginnings, our roots, our communities, our support systems, and our collective and individual selves. We “come-in.” (A. Wilson, Citation2008, pp. 197–198)

Introduction as Protocol

My family comes from a small rancho (rural village or town) of about 1200 people by the name of La Luz at the foot of a cerro (hill) in southern Guanajuato, Mexico, the ancestral Lands of the Chichimecatl Guamares and the P’urhépecha people. The valley that forms much of my rancho, the nearby ranchos, and the pueblo (town) de Salvatierra is called Guatzindeo, which closely translates to “the place of beautiful vegetation” (Gobierno de México, Citation2019, para. 1). My family no longer holds established ties with an Indigenous community from Mexico, given the complex history of colonialism, mestizaje, and Mexican hegemony (Cotera & Saldaña-Portillo, Citation2014; Saldaña-Portillo, Citation2016). However, what I do know is that my family has lived at the foot of this cerro for centuries. The Land has taken care of so many of our generations, and the relationship we have with our homelands is sacred, real, and intergenerational. As descendants of Indigenous people, our stories are important to weave together because we are part of community (Montes, Citation2022; S. Wilson, Citation2008) and because our stories hold our theories of the world (Brayboy, Citation2005).

I now honor the Lands where the ancestral Waters run deep beneath the surface and stretch wide across the horizon. The Land where I write today has many place names, and I introduce one of those place names in the Coahuiltecan language, Tza Wan Pupako, or what is colonially known as Austin, Texas (Indigenous Cultures Institute, Citation2022). The Waterways that give life to this region are called Yana Wana, the Water’s spirit, and the name for mother earth is Tap Tai. I would like to further center the Carrizo and Comecrudo, Coahuiltecan, Caddo, Tonkawa, Comanche, Lipan Apache, Alabama-Coushatta, Kickapoo, Tigua Pueblo, and all other Indigenous people who are from and/or have become part of what is colonially referred to as central Texas. This type of work calls for a process that centers the relationality and sustainability of kinships between us as Two-Spirit, Queer, and Trans (2S/Q/T) educators and our spirits, our ancestors, the Land, the Waters that nourish us, and the generations who will soon follow. Therefore, I move to center our experiences and co-create Queer Indigenous futures that can be and have always been.

Queer Theory and Indigenous Education

Critical Queer inquiry and theories have garnered considerable traction within education over the last two decades and have generated imperative dimensions of curriculum theorizing, pedagogy, and educational methodologies more broadly. Queering environmental education (Gough et al., Citation2003), disrupting heteronormativity in curriculum theory (Sumara & Davis, Citation1999), and engaging in Queer activism as anti-oppressive pedagogy (Kumashiro, Citation2002) have all provided critical and generative nuances to education research. However, not much scholarship has deliberately bridged Indigenous and decolonizing studies with Queer educational research aside from more recent work (de Finney et al., Citation2019; Moreno, 2019; L. T. Smith et al., Citation2019; A. Wilson, Citation2008). These disciplines do not seamlessly meld together and are often conflicting, but it is precisely this intersection that offers generative possibilities for curriculum studies, pedagogy, and education. This intersection brings forth a critique of Queer education studies by underscoring how settler colonialism is often left under-analyzed and can often reinscribe notions of (Queer) settler emplacement (Tuck & Yang, Citation2012) and settler homonationalism (Morgensen, Citation2011). As Scott Lauria Morgensen (Citation2011) has stated, “when modern sexuality queers white settlers, their effort to reclaim a place within settler society produces white and non-Native queer politics for recognition by the state” (p. 1). Thus, scholars have taken up the task of Queering Indigenous education to further complicate and nuance the complexities between Indigenous and decolonizing studies, Queer theory, and education (A. Wilson, Citation2008, Citation2018b; Spillet, Citation2021).

Queering Indigenous studies has been explained explicitly by Opaskwayak Cree Nation Two-Spirit scholar Alex Wilson as “opening up discussion of and challenging the ways in which some within the field of Indigenous studies have reinforced and entrenched binaries and hierarchies related to gender and sexuality” (A. Wilson, Citation2018b, p. 139). Indigenous scholars are now discussing the nexus of critical Queer studies, Indigenous education, and Land-based education to further imagine the possibilities of Queer Land relations, primarily in relation to pedagogy, curriculum, and education broadly (Spillet, Citation2021; A. Wilson et al., Citation2021). What are, then, the possibilities of Queer Land education in different Indigenous contexts? At the intersection of this inquiry lies the heart of this project: (re)storying Queer Land education within Indigenous Texas. Alongside the Land of the Spirit WatersFootnote1, the following question guides this work: How are Two-Spirit, Queer, and Trans Indigenous educators (re)storying their Land relations in central Texas by creating Queer Indigenous hubs that center Land-based pedagogies and curriculum?

This article emerged from my co-collaborative dissertation research, for which I intentionally spent a year with 2S/Q/T Indigenous educators in Tza Wan Pupako between 2021 and 2022. Although the article primarily draws on instances from 2021–2022, the relationships that inform this article have existed since 2016 and, as such, being in relation to Land, community, and Queer Indigenous kinships have been continuous processes for me and the educators with whom I have co-theorized. As we formed our web of Queer Indigenous relations, I began to take notice of how we were being guided by Land and informed by our commitment to (re)learning and (re)storying our ancestral practices. Many of us, including myself, had unfortunately experienced gender-based violence and homo/transphobia within educational spaces and even our own Indigenous communities. However, what emerged from our conversations was the necessity to gather as 2S/Q/T Indigenous people to fortify our Queer Indigenous kinships and to further heal the enduring marks cisheteropatriarchy and settler colonialism have left on our broader Indigenous community.

Guided by Queer Land education (A. Wilson et al., Citation2021), I use the term (re)charging Queer Indigenous zones to describe the process of 2S/Q/T Indigenous people gathering at sites of recharge and giving life back to the Land, community, and our ancestors. I co-theorize with the recharge zone, a hydrogeological process that happens in central/southwest Texas and is responsible for creating the springs that the Miakan-Garza Band of Coahuiltecans continue to have spiritual kinship with. The recharge zone is not just a hydrogeological process; it is also a formation of social relations that entails the complexities of Queer mobilities, sacred epistemologies, and Land-based kinships. In their introduction, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Eve Tuck, and K. Wayne Yang (2019) included a conversation between Erin Marie Konsmo and Winona LaDuke that further situates Water, Land, and gender as sources of abundant relations. As Konsmo stated,

How do we think about water and gender? Often these things are segmented and isolated in building social movements, but they overflow. How can water help us approach gender differently? Water brings us together. If we could rally together for trans youth like we do for water, what would that look like? … Water is self-determining. You’re not going to go to the lake in August (a hot month) and tell it to be an ice cube. If we love water in all the various forms that it takes, then we can love our family in all the complex ways they exist. (L. T. Smith et al., Citation2019, p. 3)

Pedagogical Hubs

It is through this love of Water and Land that 2S/Q/T Indigenous people are mobilizing, overflowing, inundating, and proliferating through space, time, and place. The way that 2S/Q/T Indigenous people are gathering is deeply pedagogical because Land and Water encourage the act of gathering as a curricular manifestation. These acts of physical and spiritual gathering for 2S/Q/T Indigenous people, I propose, are pedagogical hubs—spaces of learning, epistemological depth, and cultural significance. In witnessing my co-theorists gathering into pedagogical hubs, we/they created sites of recharge that invited in other 2S/Q/T Indigenous people. In more than one way, my co-theorists and I are mirroring processes such as the recharge zone because our acts of gathering give life to a region marked by cisheteropatriarchy and the enduring remnants of settler sexualities in the region. Thus, (re)charging Queer Indigenous zones creates multiple registers of epistemology with Land and demonstrates how 2S/Q/T Indigenous people co-create and fortify dreams, stories, experiences, and futures that have always already been Queer.

The principal pedagogical hub that I will discuss is Danza Ollinyolotl, an informal Danza Mexica (Aztec Dance) group, of which I am an active community member. Within our “informal” practices, which have taken place in parks, dance studios, and people’s homes, we as a group purposefully undo and break away from binary views of engaging with Danza. By intentionally transgressing against “traditions” rooted in the gender binary (Spillett, Citation2021), we create a site of recharge that actively restores/restorys Queer Indigeneity because it is through the Land that we are gathering as 2S/Q/T Indigenous people (A. Wilson et al., Citation2021). The Land is instructing our internal Waterways to gather, create, transform, and give back because the Land does not see gender binaries yet encapsulates all the genders that can possibly exist. As Danza Ollinyollotl overflowed into our ceremonies, our practices, and our larger community circles, it became evident that our acts of recharge for/with the Land were mobilized through Queer love, joy, and abundance; as we rippled our way outwards, we (re)emerged like life-giving springs. Therefore, the concept of (re)charging Queer Indigenous zones speaks to the multiple registers of learning with the Land and further situates this process of gathering within Queer Indigenous subjectivities.

As we journey downstream, I describe the theoretical orientations this project incorporates. In this project, a Queer Land education theory (A. Wilson, Citation2018b; A. Wilson et al., Citation2021; Spillett, Citation2021) and the gathering theory of pedagogical hubs (Ramirez, Citation2007) work in tandem to recharge Queer Indigenous zones, while being guided storywork methodology (Archibald, Citation2008). Afterward, I describe the hydrogeological process of the recharge zone and center the ancestral significance of the springs that is often silenced in this process, which ultimately amplifies 2S/Q/T Indigenous Land kinships. Lastly, I showcase stories of 2S/Q/T Indigenous educators (re)charging Indigenous zones by emplacing Queer relationalities within their/our Land-based relationships through the pedagogical hub of Danza Ollinyolotl. As I made my way down/upstream with my 2S/Q/T Indigenous community, our Waters took us to many ceremonies from Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico to El Paso, Texas, United States where our unapologetic and unruly rivers crossed paths with other Indigenous circles. It was then, during moments of mobility, when our Queer medicine was most evident. I offer closing commentary on the importance of (re)charging Queer Indigenous zones within the context of Tza Wan Pupako and the necessity of envisioning, co-creating, and giving life to Queer Indigenous futurities.

Co-Creating Pedagogical Hubs for Queer Indigenous Land Education

The first theoretical framework that amplifies this research is Queer(ing) Land education (Spillet, Citation2021; A. Wilson, Citation2018b; A. Wilson et al., Citation2021) which puts the theory of Land education (Simpson, Citation2014; Tuck et al., Citation2014) into conversation with scholarship on gender, sexuality, and kinships. Secondly, I deploy Renya Ramirez’s (Citation2007) theory of the hub to further discuss how 2S/Q/T Indigenous educators are gathering to create sites of transformational learning. Together, these two theories are circular in nature: Queer Land education proposes the Queer epistemologies embedded within Land-based pedagogies (Simpson, Citation2014), and the hub describes the process by which the educators gather.

As Tuck et al. (Citation2014) have explained, Land educationFootnote2 “puts Indigenous epistemological and ontological accounts of Land at the center, including Indigenous understandings of Land, Indigenous language in relation to Land, and Indigenous critiques of settler colonialism” (p. 13). Land education provides an epistemic territory where critical Queer studies, Native and Indigenous studies, and education studies can re-emerge to Queer Land education (Spillett, Citation2021; A. Wilson, Citation2018b; A. Wilson et al., Citation2021). Queer(ing) Land education disrupts the gender-based essentialisms embedded within environmental discourses by attending to non-binary approaches to human and more-than-human worlds while centering Indigenous gender and sexual diversity within pedagogy, curriculum, and educational praxis (A. Wilson et al., Citation2021). When you are learning from the Land and Waters of where you are, the hierarchies of gender and sexuality begin to dissipate because the Land is not reflective of hierarchies, and it is both engendered and genderless (A. Wilson, Citation2018b). I also pay close attention to (re)storying relations with Land, which Jeff Corntassel et al. (Citation2009) have described as a “process for Indigenous peoples [that] entails questioning the imposition of colonial histories in our communities” (p. 139); (re)storying relations with Land also creates or sustains stories that are not defined by settler colonialism or settler heteropatriarchy. Thus, a Queer(ing) Land education is also an anticolonial educational project dedicated to uplifting Indigenous knowledges of gender and sexuality while interrogating heteronormativity and homonormativity as settler colonial projects (Driskill, Citation2010; Driskill et al., Citation2011; A. Smith, Citation2010).

To contextualize how Danza Ollinyolotl gather, I deploy the concept of the hub as an organizing theory (Ramirez, Citation2007). The hub, as Ramirez (Citation2007) has argued, is a geographical and visual concept that suggests:

how landless Native Americans maintain a sense of connection to their tribal homelands and urban spaces through participation in cultural circuits and maintenance of social networks, as well as shared activity with other Native Americans in the city and on the reservation. (p. 3)

Queer(ing) Land Education

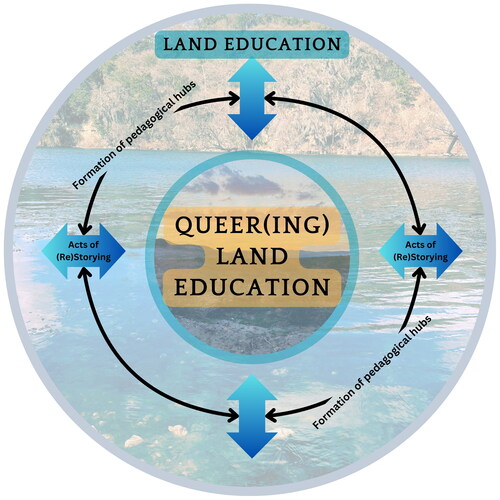

I see Queer(ing) Land education as a guiding theory, while I see the hub as a gathering theory. In other words, Queer(ing) Land education is the underlying theory of learning, pedagogy, and curriculum, and it is through the gathering theory of the hub that these sites of learning become possible. So, this work is as much about how we come to share stories, memories, and experiences as the process itself of gathering with other 2S/Q/T Indigenous educators. illustrates Land education as the theoretical foundation that encapsulates the entirety of the framework. In , the black arrows signify the formation of pedagogical hubs, an ongoing and multidirectional process through acts of (re)storying. The background where the model says “Land Education” is a picture of ajehuac yana, signaling the foundational epistemologies that ground and orient our specific Land Education. Whereas the inner circle, titled “Queer(ing) Land Education,” has a background of the desert in El Paso, signaling how the teachings from the Waters and Lands have flowed to multiple localities, engendering an already Queer Indigenous subjectivity. (Re)storying is a crucial component because it is in these moments of restor(y)ation (Muñoz, Citation2018) that my co-theorists actively uproot and destabilize binary views of gender and sexuality and thus do not let their relationships to Land, community, and ancestors be defined by settler colonialism and cisheteropatriarchy (Corntassel et al., Citation2009). These acts of (re)storying culminate into pedagogical hubs guided by an ethic of Land education; they create Queer(ing) Land education, the pulsating Waters at the center of this diagram.

Queer(ing) Land education creates multiple pedagogical and curricular moments that are attuned to a diversity of gendered and sexual ways of existing while being epistemologically embedded within Land-based knowledges. By understanding that the hub-making process is integral to a theory of Queer(ing) Land education, these pedagogical formations suggest that 2S/Q/T Indigenous educators are re-remembering ancestral practices, negotiating relations with diaspora and transnationalism, and re-kinning their relations with Land (de Finney et al., Citation2019). Lastly, Ramirez (Citation2007) has offered a situated consciousness within the hub that she has called a Native diaspora. The Native diaspora includes “the subjective experience of feeling connected to tribe, to urban spaces, and to Native peoples within the diaspora, as well as other Indigenous cultural and national formations” (p. 11). This Native diasporic consciousness is essential within the hub and especially in hub-making within a Queer(ing) Land education because it emphasizes the importance of Indigenous people’s relations to homelands and their diasporic conditions (which means being in honorable relation with the Indigenous Land where one is living). I argue that through moments of (re)storying our relationships with Land, my co-theorists and I transform the spaces (both physically and spiritually) where we gather into pedagogical hubs. This in turn serves to fortify a Queer Indigenous subjectivity that has always already been a part of our community and Land-based knowledges, a recharge of Queer Indigenous zones.

Storywork with Queer Indigenous Stories

Queer(ing) Land education draws on Indigenous storywork methodology (Archibald, Citation2008; Archibald & Parent, Citation2019) as stories are key to the pedagogical formations that ripple through these pages. How does Land want me to take care of these stories? What do Land and community suggest I do as I weave together the beautiful tapestry of stories shared? As Jo-ann Archibald (Citation2008; Archibald & Parent, Citation2019) has suggested, storywork is both a powerful methodology and a humbling process. Indigenous stories require precise listening and often defy concepts of singularity, hierarchy, and linear timelines. As such, Indigenous stories hold our relationships and therefore are both context and community relationality (S. Wilson, Citation2008). But stories are also dangerous as Archibald (Citation2008) has shared from Cherokee storyteller Thomas King (Citation2003). That is why (re)storying (Corntassel et al., Citation2009) is a vital process to this project; it not only destabilizes dangerous stories, but it also restores the relationship between my co-theorists and Land, community, and ancestors. The stories that I share are not meant to be encapsulated within “clear” timelines or demonstrate linear storytelling, because we think and share in circularity and in spiral formations. In the following section, I introduce the recharge zone while also troubling how the process that occurs in this area does not embody the spiritual teachings, stories, and knowledge of the Coahuiltecan people and Tza Wan Pupako.

The Spirit Waters of the Edwards Aquifer

The Edwards Aquifer is an environmentally sensitive karst aquifer located as far north as Austin, Texas, and it extends to areas in central/west Texas such as Brackettville (The Edwards Aquifer Website, Citation2022). Aquifers act as intricate networks of Water storage underneath the earth and are instrumental in providing Water to the immediate area. The Edwards Aquifer begins its journey in the contributing zone where rain run-off Water seeps into the Water table below and later emerges as streams and springs. As the Water makes its way east, it encounters what is known as the recharge zone, the region that is marked by exposed limestone and where Water enters through crevices, cracks, caves, sinkholes, and other porous formations. Due to this porosity, the Water percolates into the artesian zone, the interconnected network of limestone formations ranging from small pores to large caverns and moves eastward. Due to the heightened pressure within the artesian zone, Water is often forced back up to the surface as springs and free-flowing wellsFootnote3. The springs that emerge because of the artesian zone pressure have been and are imperative for life in central/southwest Texas.

For example, San Antonio, Texas is one of the cities that largely relies on the Edwards Aquifer (i.e., for drinking Water, irrigation) and, up until 2000, relied entirely on the aquifer to sustain the city’s needs (Richter et al., Citation2013). Due to raising concerns of aquifer depletion, San Antonio took drastic measures to reduce Water usage by creating a permit system that leased aquifer usage to farmers and began tapping into other aquifers nearby such as the Carrizo aquifer, ultimately reducing the city’s Water usage by almost 50% (Richter et al., Citation2013). The information provided by environmental scientists, hydrogeologists, and Water engineers is imperative in our times of environmental precarity. Nonetheless, absent from the conversation is the relationality that Indigenous people have had, and continue to have, with those Waterways.

The Springs and The Spirit Waters

Due to the pressurizing effects of the artesian zone, there are many springs throughout the region, four of which are sacred to the Coahuiltecan people: Tza wan pupako (Barton Springs in Austin), ajehuac yana (Spring Lake in San Marcos), saxōp wan pupako (Comal Springs in New Braunfels), and yana wana/yanaguana (the Blue Hole headwaters of the San Antonio River) (Indigenous Cultures Institute, Citation2022). The Miakan-Garza Band of Coahuiltecans in San Marcos, Texas recognizes these springs as sacred sites because of their historical, ceremonial, and spiritual importance. According to the creation story shared by the Miakan-Garza Band, the Coahuiltecan people emerged as physical bodies from the spirit world through ajehuac yana. Adrian Chavana (Citation2019) has described how Yanaguana has been for the last 11,000 years, and continues to be, the lifeblood of the area; Chavana has also highlighted the importance of how these sacred Waters are deeply embedded within the spiritual geographies of the Coahuiltecan people. The creation story shared by the Miakan-Garza Band of Texas is a constant reminder of the ethical, spiritual, and community commitments that are embedded within the relationship of the sacred springs (Nxumalo & Montes, Citation2023; Nxumalo & Villanueva, Citation2019).

Such commitments can be interpreted on the White Shaman Panel, rock art located in Comstock, Texas which, according to Mario Garza, Gary Perez, and other archeology and history consultants, depicts the creation story of the Coahuiltecan people (Garza, Citationn.d.). The White Shaman Panel illustrates the journey of the original people as spirits in the underworld, their emergence at ajehuac yana as physical beings, and the instructions of the all night Paxē (peyote) ceremonies. These Paxē ceremonies are imperative to many Indigenous communities, especially for the Miakan-Garza Band of Texas, and the panel is interpreted to be ancestral instructions delineating what people must do to be in rightful and honorable relationship with the earth, the Waters, Paxē, and the ancestors. Through intergenerational stories, the Miakan-Garza Band powerfully demonstrates the interconnectedness between ancient teachings and knowledge, as well as the connection with the sacred essence of the Spirit Waters in the Austin–San Antonio region. What our Elders ultimately suggest is that living in relation to these Waterways is a deeply spiritual, curricular, and pedagogical act. Without this understanding, Water is seen as a commodity, immaterial, and a natural resource that must be managed and controlled, ultimately devoid of spiritual and communal interdependence (Chiblow, Citation2019; Middleton-Manning et al., Citation2018). As Fikile Nxumalo and Marleen Villanueva (Citation2020) have shared,

We speak of water as a living being, a spirit that thinks, hears, has life and gives life. For generations, our elders have told us what many are now beginning to see: water listens to what we say and think. She listens and holds memory. She understands. (p. 70)

To understand this article, it is imperative to consider the embodied, spiritual, affective, and communal way that Land and Waters are understood and are further emplaced with 2S/Q/T Indigenous people. Following the creation story of the Miakan-Garza Band, and re-interpreting the recharge zone, 2S/Q/T Indigenous people in central/south Texas demonstrate how they/we move together, gather at sites of recharge, navigate porous formations, and emerge and give life to the region. 2S/Q/T Indigenous people gather together through the intimately bonded calls of their internal Waters, and in doing so, they disrupt the remnants of settler sexualities and the marks left by cisheteropatriarchy. Recharging the area, a process that has been ongoing since time immemorial, is also about emerging as 2S/Q/T Indigenous people in the way that the Water has always instructed. We arise and “come in” as necessary components of the communal fabric (A. Wilson, Citation2008). This process of (re)charging Queer Indigenous zones ultimately describes our spiritual and communal commitments to the Waters that have instructed our malleability, the Land’s provision of geographies of emergence, and the springs from which creation has always already included the Queer Indigenous self.

(Re)Charging Queer Indigenous Zones

Danza Ollinyolotl

To begin, journey with me alongside the rivers where Queer Waters eventually will meet once again. I arrived in Austin, Texas in 2016, guided by tides of intuition, knowing no one yet feeling as if familiarity would meet me there. Once there, I met the Indigenous community who would eventually be my spiritual family. This was also during the height of the Standing Rock Movement, or #NoDAPLFootnote4, and the Elders of the Miakan-Garza Band of Coahuiltecans entrusted us with carrying the ancestral Spirit Water Yana Wana to our relatives further north after one of our community members had a dream of merging the Waters of Texas with an unknown river. We listened to this message and realized the Waters were urging us to mobilize and so we listened intently and made our way. There we met the newly established International Indigenous Youth Council and thus our Water memory began to ripple out in meaning. We realized that our embodied Waters had taken us upstream to envision a confluence, a meeting of multiple bodies of Water. The group members who journeyed to Standing Rock, many of whom are Two-Spirit and Queer, decided that upon our return we had a responsibility to share the message that we received. From there, we began to dream of not only what could be, but that which must be. As the springs have taught us, we began to emerge with force, and through our surge, transform the landscape to strengthen our relations.

In the picture below, you are witnessing a gathering of Indigenous Danzante Mexicas (Aztec Dancers), many of whom are 2S/Q/T, celebrating the winter solstice in late December 2020. These gatherings happen frequently as part of the Danza group called Danza Ollinyolotl, which can be most closely translated to “the movement of the heart.” Danza Ollinyolotl has been a particularly powerful and transformative space for many 2S/Q/T Indigenous people in the local Austin and larger central Texas area because it is one of the few Danza groups in Texas that fully embraces and centers 2S/Q/T Indigenous people. The main instructor, Ollin, is a Two-Spirit and non-binary Indigenous danzante; they have been dancing since they were 14, and they are also a dance major at the university that they attend. Alongside other 2S/Q/T Indigenous people and those who are active supporters and allies of 2SLGBTQI + people, we created Danza Ollinyolotl in 2018. The naming of the group is also imperative to note, as the final name was a combination of Ollin’s Nahuatl name as well as a different member’s name, Tepeyolotl. Through discussion, the name Ollinyolotl emerged. As such, the name signals the importance of creating with community ().

Even though the group initially practiced at the university that many of us attended, it is a mobile and community-oriented space that encourages people from the Austin and neighboring communities to participate. As noted, Danza Ollinyolotl is an informal Danza Mexica group; the group is not considered a formal calpulli, loosely translated to “longhouse,” which is contemporarily used to signify a formalized Danza Mexica group (Colín, Citation2014). Although Danza Ollinyolotl actively practices and gathers, the group would not be considered a calpulli since this formal recognition requires certain ceremonial and spiritual agreements, practices, and guidance. Although “informal,” the gathering of the danzantes who are in Danza Ollinyolotl, the community that has been built, and the active choice to center 2S/Q/T Indigenous people has created a robust and transformative site of learning. I call this type of gathering a pedagogical hub because of how relational and transformative learning occurs in co-curricular ways. Guided by commitments to the Land, community, ancestors, and ceremony, 2S/Q/T Indigenous people demonstrate the curricular-building capacities that actively foreground a Queer Indigenous cosmology and transgress against the coloniality of the gender binary (A. Wilson et al., Citation2021). Put differently, Danza Ollinyolotl has established a pedagogical hub where learning, knowledge, and community are co-constituted through commitments to Land, ceremony, and centering Queer Indigenous voices.

Beyond Identity and Emplacing Queer Indigeneity

I began with our journey to the Oceti Sakowin Camp in Standing Rock, North Dakota, United States because our community believes the call to protect and defend the Lands and Waters with our Lakota and Dakota relatives ushered in a period in which we recognized the heightened importance of defending and protecting our sacred Lands and Waters. Importantly, our intensifying relationship with Yana Wana guided us towards acts of restor(y)ation (Muñoz, Citation2018) in which fluidity translated to robust understandings of self that are often not legible through English and western concepts. As Joanne Barker (Citation2019) has shared, Water is not created but is consistently shaped and morphed; these transformations are present in many Indigenous teachings that relate to relationality, reciprocity, memory, stories, and self. For example, Ollin shared:

I’m really grateful for my relationship with Yanawana, with movements, with a lot of teachers that I’ve had who facilitate a space of a nonlinear spectrum, or, not even a spectrum, a circle. Once I understood that I don’t have to be something or someone, and all I have to do is be me authentically, that makes more sense than trying to claim any kind of identity or anything because I only use or put on these identities so that someone else can understand me or understand me [in] their perspectives. I think that’s something that I’ve tried to understand.

Further in our story sharing, Ollin mentioned that “through Yana Wana I’ve been able to—I mean literally understand everything and anything.” Their statement highlights the importance of the Spirit Waters, Yana Wana, and the relationship Ollin has built with them, which constitutes knowledge and meaning making. As Dorothy Christian and Rita Wong (Citation2017) have written:

When we tell the stories of ourselves, we are also telling the story of the specific waters that move through us at a particular moment, albeit more often than not unconsciously … when we tell a story of water, we are also telling stories of ourselves, our societies. (p. 7)

Engendering Queer Land-Relations

The purpose of Danza Ollinyolotl extends beyond practicing towards a communally bounded act of refiguring presences (Nxumalo, Citation2016) that actively foregrounds and centers the re-kinning aspect of Queer Indigenous subjectivities (de Finney et al., Citation2019). Take, for example, the following story from my ethnographic witnessing after one of our practices:

We were gathering to practice Danza in mid-October as there were ceremonies that were quickly approaching that were important such as Dia de los Muertos (day of the dead). Ollin was already present at the park where we practice, setting up the altar, and preparing the drum by leaving it under the sun. We are about to begin and as we always do, we open up to the four directions where those who are holding the elements (fire, air, etc.) are asked to assist in acknowledging the directions. One of the non-binary danzantes asks if they can drum, and so we begin our practice. At the end, like we always do, we gather around in a circle to express ourselves. Ollin leads us and introduces themselves, the pronouns they use, and their words. Everyone follows by sharing their pronouns, with many expressing their gratitude for being able to come to a space like this every week. One such danzante after we closed mentions “this is what I have been searching for … I only wished I would’ve found it sooner.”

Danza Ollinyolotl, thus, is a site of recharge; it is a spiritual and physical place where Waters meet and, through their confluence, navigate the porosity of systems and create a depth of curricular co-creation. Danza Ollinyolotl serves as a place in which acts of restor(y)ation, such as non-binary people re-connecting with the drum, coalesce into a pedagogical hub that is guided by our relationships with the Land, Waters, community, and ancestors. Ultimately, strengthening a Queer Land education that explicitly ruptures the settler and colonial gender binary is a movement towards Queer Indigenous futurities.

Anticolonial Queer Praxis

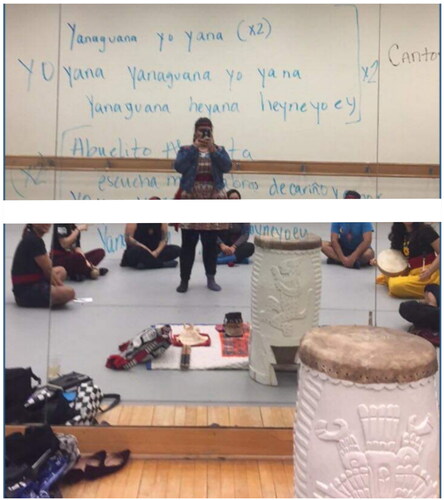

Community members who do not identify as 2S/Q/T also demonstrate strong support and allyship in Danza Ollinyolotl. As Sarah Hunt and Cindy Holmes (2015) have suggested, friendship is a generative site for enacting allyship through a decolonial Queer praxis within our everyday practices. When discussing a Queer Land education, some may believe that this only relates to those who are indeed Two-Spirit, Queer, and/or Trans. However, a Queer Land education, at its core, centers how “queering becomes part of ongoing pedagogy and [provides] both students and faculty a way to question and undo colonial gender and sexuality constructs, while simultaneously strengthening the bond to land [emphasis added]” (A. Wilson et al., Citation2021, p. 228). Therefore, by strengthening our bonds to Land, we simultaneously disrupt colonial gender and sexual binaries and nourish our relations with all of our kin. shows a community member, who does not specifically identify as 2S/Q/T, teaching and facilitating a song-sharing session.

Figure 4. Flier for Danza del Jaguar created by Familia Kauyumari with the translation of the message at the bottom being “Time to honor the spirits of the Earth.”

The figure depicts a non-2SLGBTQI + community member engaging the group in a Coahuiltecan song that speaks to learning from and with the sacred Waters, Yana Wana. The song, like many medicine songs, has traveled elsewhere and eventually made its way to us, in this space of 2S/Q/T porosity. The song includes the lyrics:

Yanaguana yo yana

Yo yana yanaguana yo yana

Yanaguana heyana heyneyoey

Abuelito, Abuelita

Escucha mis palabras de cariño y amor

Yo yana yanaguana yo yana

Yanaguana heyana heyneyoey

Water does not exist solely for use by human beings. All of life has access rights to the use of water and its gifts. Exploiting the water to human ends will ultimately mean breaking relationships with other parts of Creation: the animals, the land, plants, the birds, land, and sky … the water is a birthright and a source of sustenance for our people. Each of us, therefore, has a great responsibility to protect and care for it. (p. 96)

Curricular Mobilities and Down/Upstream Epistemologies

“What does water want me to know?” asked Alannah Young Leon and Denise Marie Nadeau (2018). This question positions Water as embodying memory and knowledge, instead of simply thinking of it as an immaterial natural resource. Water memory is powerful. As Leon and Nadeau (Citation2018) further shared, “I begin to move like water, I embody the water through various movements, the same water that has been here for billions of years, circulating and flowing into many forms of water, clouds, ice, mists, and torrential rains” (p. 121). Water’s constant mobility is inherently woven into the fabric of Water epistemologies. Thus, we learn that one must be adaptable and open to multiple streams of consciousness. Danza Ollinyolotl and our community at large are guided by these ancestral knowledges of respecting and building kin with Water. This is because, as our Elder Maria Rochas has shared before, “All of the waters are connected. If we poison our sacred spring here, it poisons the river, which poisons the ocean, which poisons our relations across the sea. That is why we have to protect our sacred springs” (Nxumalo & Montes, Citation2021, para. 1). As 2S/Q/T Indigenous people gather through their confluence/ing of Waters, their Waters also urge them to go elsewhere and follow their intuitive flow. Thus, knowledge moves in multidirectional and cyclical ways, where curricular mobilities map the different down/upstream epistemologies present through Land and Water teachings (Muñoz, Citation2018; Yazzie & Baldy, Citation2018). In the year of ethnographic witnessing, I had the privilege of journeying with 2S/Q/T Indigenous curricular mobilities; through this process, we took the knowledge, teachings, and curriculum that we co-constituted to different contexts, places, and Lands.

Flowing Curricular Mobilities

One such place is the annual Danza del Jaguar (dance of the jaguar) put on by Familia Kauyumari in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico. This annual ceremony takes place at the heart of the Huasteca mountain range located about an hour outside of the city of Monterrey during the summer solstice. The inception of this specific ceremony was gifted to the Elder of this Indigenous community in a vision to honor the relatives and spirits of the mountain, one of which is the jaguar. Calpullis all over Mexico and the United States come to this ceremony, with each calpulli bringing their pantli or banner with an insignia that represents their Danza community. This all-night peyote and Danza ceremony, in many ways, was a gathering of Indigenous communities, guided by their relationships to Land, ancestors, and community ().

Although our group is not necessarily a calpulli, we went to this ceremony as the group Danza Ollinyolotl but representing calpulli Mitotiliztli Yaoyollohtli from Dallas, Texas. Five members of Danza Ollinyolotl, all of us 2S/Q/T, journeyed together to Monterrey, Nuevo León. Although Ollin and I had been to this particular mountain for different ceremonies, we had not been to Danza del Jaguar; the other community members shared that this was their first time praying with this particular ancestor mountain. Ollin, Yana (another danzante), and I shared with the other community members what traditional protocols were in place with this Indigenous circle. For example, we shared that “traditionally” in this circle, “women” wear skirts that extend past their knees, and “men” wear pants. However, because we were a group of 2S/Q/T peoples, we told our 2S/Q/T relatives that although this is how this particular community sees attire, they should wear what is aligned with them in spirit (Simpson, Citation2017; A. Wilson, Citation2018a). At the end of the day, Land, ancestors, and spirits see our essence as relations, as essential to our community, and that is why we were called to this particular ceremony. All of us wore what felt right, and we danced the whole night with the Land, the ancestor mountain, the jaguar, and our relations in the circle.

During the ceremony, Ollin was given segunda palabra, which translates to second word. In Danza ceremonies, being given a palabra is both a huge honor and great responsibility as those who are given them are seen as the ones who are guiding the ceremony. All of us from Danza Ollinyolotl were honored and proud to have a non-binary Two-Spirit Indigenous person serving as one of the guides for the ceremony because it signaled the importance of 2S/Q/T subjectivities. During the ceremony we were asked to offer a Danza, and as a group we offered a dance/prayer called paloma (dove), which was one of the Danzas we had been teaching each other over the years. Like la paloma that flies to greater heights and soars through gusts of wind, so did we. After the ceremony had concluded, someone from a different calpulli approached us and told us “Gracias por compartir sus danzas, estuvieron muy bonitas. Me encantó como las danzaron” (Thank you for sharing your dances, they were very beautiful. I loved how you all danced them) ().

Although other calpullis have been around for decades, we as Danza Ollinyolotl have created a spiritually and epistemologically powerful space that we carry to other ceremonial spaces. For example, we knew that our extended community, Familia Kauyumari, sees gender expression in “traditional” ways. However, our intentional relationship with the Elders and each other fostered moments of rupturability in which the gender binary was submerged and, in its place, a (re)storyed gender and sexual expansivity surfaced. Put simply, “tradition,” as it relates to gender expression, became less enforced because we as a group firmly disrupted the gender binary; our disruption encouraged the ceremony at large to envision gender and sexuality as always already malleable. Through and with our dedicated commitment to Land, the Waters that guided us there, and each other, we enacted the very essence of a recharge zone: giving life to the already Queer(ed) Land.

Gathering Past the Recharge Zone

Another example was during our annual Sundance ceremony which is hosted by our Elders from El Paso, Texas in Hueco Tanks State Park. Starfire attends this Sundance ceremony, and they recounted an experience back in 2019 when the “women” and “men” (referring to cis women and men) were separated before entering a sweat lodge ceremony. However, as Starfire is non-binary, and knowing that there were also two Trans sisters in our group, this became a moment when our 2S/Q/T kin networks created moments of rupture, or better yet, of restor(y)ation. As Starfire recalled:

I do remember whenever [our two Trans sisters] were at Sundance and we had the line de mujeres, and I was close to the front and I thought about it and I looked back and I looked at them and I went back. I think I was the second in line and I left. I asked them, “What are y’all going to do?” They were just like, “We’re just going to stay in the back and play it safe.” I’m like, “No, y’all should go.” Then everybody was, “Yes, y’all should go.” I told them y’all go in front of me and I’ll be behind y’all. I was like if they say anything … I’m like, actually this is how it’s supposed to be. Las mujeres are in front of me. I don’t want to be in the mujeres or in the men but I’m going to be the last one in the mujeres and close that gap. They didn’t say anything. Yes, they never said anything, but I was ready to fight.

The calpulli leader from Mitotiliztli Yaoyollohtli in Dallas, Texas is also a spiritual leader for this Sundance ceremony, and many of the people in Danza Ollinyolotl attend this specific Sundance ceremony every year. Although I will not get into specifics of the ceremony itself, it is important to note that Ollin and Yana were among the people who were participating in the ceremony, referred to as Sundancers, and others like Meztli, Starfire, and myself were there as supporting community members. Along with other Danza Ollinyolotl members, we road tripped from Austin, Texas to El Paso, Texas for the Sundance ceremony in July 2021.

Curricular mobilities in fact mirror the way in which Water runs through this region. As I mentioned before, recharge happens in the area due to the Water that comes from the contributing zone that is further out in west and southwest Texas. As reflections of the Land, and as circular Water memories dictate, we go back to places of ceremony, prayer, and creation because we are engaging in acts of contribution. Martuwarra RiverOfLife (Citation2022), a piece that voices River and is River as socio-culturally located within Indigenous contexts, suggested that “Kin is an undivided, non-binary world of interrelationship, such that speaking with and as River on the basis of cultural knowledge and authority, observation and recognition is normal” (p. 11). In this respect, we also speak as place and through Land (Bawak Country et al., 2016; Styres, 2018), and we do so because we realize that although there is much work to be done regarding gender and sexuality in our community, the Land itself welcomes us back year after year. The Water’s circularity guides us back, but it is through our intentional acts of (re)charge that we become aligned with the call that the Land and Waters are giving us. As Shawn Wilson (Citation2008) has reminded us “rather than viewing ourselves as being in relationship with other people or things, we are the relationship that we hold and are a part of” (p. 80). Through this understanding, (re)charging Queer Indigenous zones translates to multiple registers of relationship and kin-making with the Land of the Spirit Waters and the Queer Indigenous futurities that must exist within our communities.

Queer kinships are sometimes contentious within spaces saturated with cisheteropatriachy and can create environments that are complicated, murky, filled with debris, and sometimes uncontrollable. What I mean by this is that despite our Queer kin-making, 2S/Q/T Indigenous people are regularly caught in the middle of the clash between “tradition” and Indigenous genders unbound by the binary. Much like many rivers, streams, and lakes, our communities have been polluted and invaded by colonial logics, and thus we are in moments of reclaiming and taking back our bodies (Driskill, Citation2004; Martuwarra RiverOfLife, Citation2022). As Spillet (Citation2021) has articulated

if not critically analyzed and interrupted, Western configurations—specifically those tied to gender and sexual identities—may be falsely presented as “traditional teachings” … When colonial tendencies are perpetuated through “traditional teachings”, it very dangerously pushes our relations, whose identities are more expansive than gender binary, outside the protection of our kinship systems. (p. 15)

So in actuality, 2S/Q/T Indigenous people are desperately needed in Indigenous communities because we are spiritual and physical proof that a world beyond the binary exists and has always existed. The curricular mobilities that I share here are also the medicines of 2S/Q/T Indigenous people guided by the Spirit Waters (Driskill et al., Citation2011) and also speak to the process of restor(y)ation and “coming in” to our Indigenous communities (A. Wilson, Citation2008). Although we are sometimes outside of the immediate kinship systems because of “tradition,” we actively foreground acts of re-kinning (de Finney et al., Citation2019) with Land, ancestors, creation, and each other as ways to re-remember our gender-diverse systems of relationality. As curricular mobilities encourage us to move through transfigurations for the Queer Indigenous futures that await us, our down/upstream epistemologies remind us that community and family are also where one makes them.

Conclusion

In this article, we have journeyed together as the Waters have instructed. The recharge zone is an epistemological and ontological process by which 2S/Q/T Indigenous people in central Texas create streams of consciousness and knowledge. The recharge zone is necessary because it is through the acts of recharge that occur there that life-giving springs emerge. With Land polluted by cisheteropatriarchy, gender violence, settler sexualities, and toxic gender binaries, our acts of recharge are indeed moves towards (re)storying the Land where gender freedom has always already existed. Danza Ollinyolotl is a site of recharge because it began long before we gathered as an informal group and will continue far beyond what we can possibly fathom.

Generative educational and community-based scholarship has emerged within the Canadian context on 2S/Q/T Indigenous experiences (de Finney et al., Citation2019; Fast et al., Citation2021; Laing, Citation2021; Spillett, Citation2021; A. Wilson et al., Citation2021). Much of the literature that helps root this project is dedicated to these scholars, while I simultaneously know that there is bountiful knowledge, learning, and ways of being that are immersed within Tza Wan Pupako and the Lands of the Spirit Waters. “(Re)charging Queer Indigenous Zones” is a curricular undertaking guided by Queer(ing) Land education. This embodied, living, and malleable curriculum is etched into the porous formations of the Land and is revealed by 2S/Q/T Indigenous epistemologies. Settler colonialism has attempted to destroy the gender and sexual expansivity within our communities, but my co-theorists and I are reminders of that which could not and will never happen. This is also an invitation for Queer scholarship to engage thoughtfully and respectfully with Indigenous and decolonial literature, while encouraging Indigenous studies in education to take up a Two-Spirit and Queer critique and doubleweave an otherwise (Driskill et al., Citation2011; A. Wilson, Citation2018b). As Hunt and Holmes (Citation2015) have suggested:

A decolonial queer praxis requires that we engage in the complexities of re-orienting ourselves away from White supremacist logics and systems and toward more respectful and accountable ways of being in relation to one another and the lands we live on, while not appropriating Indigenous knowledge. (p. 168)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pablo Montes

Dr. Pablo Montes is a descendant of the Chichimeca Guamares and P’urépecha people from the valley of Huatzindeo (Salvatierra, Guanajuato, Mexico), specifically from a small rancho called La Luz at the foot of the Culiacán mountain. They are an Assistant Professor of Curriculum Studies at Texas Christian University and received their Ph.D. in Cultural Studies in Education from the University of Texas at Austin. Their main research interests are at the intersection of queer settler colonialism, Indigeneity, and Land education. Their current project emphasizes the transformational learning spaces that Two-Spirit, Queer, and Trans Indigenous educators create alongside their Indigenous community, with Land, and other Queer Indigenous people.

Notes

1 Land of the Spirit Waters is inspired by Adrian Chavana’s (Citation2019) early work and also his completed dissertation “Reclaiming Tribal Identity in the Land of the Spirit Waters: The Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan Nation” (2023). As Chavana mentioned, Yanaguana (alternate spelling for Yana Wana) closely translates to Spirit Waters in Coahuilteco (Pakawa/Tejano), also commonly known as the San Antonio River. Additionally, Yana Wana/Yanaguana can refer to the Spirit Waters that are interconnected throughout central and south Texas. Therefore, when I refer to the Land of the Spirit Waters, I mean the interconnected region of the four sacred springs in the Austin–San Antonio corridor. However, it is important to note that this is not shared understanding across all Indigenous communities in this region and that I am drawing my description from the Elders who have taught me. For historical insight into Indigenous identity in central and south Texas, refer to Chavana (Citation2023).

2 Land education is often written as Land-based education, and both are appropriate ways to delineate knowledge, learning, and relations derived from/with/through Land. I deploy “Land education” moreso as a way to highlight how Land as education is always already embedded and does not necessarily need the description of being “based” to assert its importance.

3 For a diagram of the process that occurs in the recharge zone, please see Texas Hill Country Water Resources (Citation2013).

4 #NoDAPL, No Dakota Access Pipeline, or the Standing Rock Movement is considered to be the largest Indigenous protest movement in the 21st century. The movement centered around the protection of Land and Waters against an oil pipeline that was in process of being built in North Dakota. For a more robust account of this movement, refer to the book Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (Estes, Citation2019).

References

- Ansloos, J., Zantingh, D., Ward, K., McCormick, S., & Bloom Siriwattakanon, C. (2021). Radical care and decolonial futures: Conversations on identity, health, and spirituality with Indigenous queer, trans, and two-spirit youth. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 12(3), 74–103. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs123-4202120340

- Archibald, J. (2008). An Indigenous storywork methodology. In J. G. Knowles & A. L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 371–385). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226545

- Archibald, J., & Parent, A. (2019). Hands back, hands forward for Indigenous storywork as methodology. In S. Windchief & T. San Pedro (Eds.), Applying Indigenous research methods: Storying with peoples and communities (pp. 3–20). Routledge.

- Arvin, M., Tuck, E., & Morrill, A. (2013). Decolonizing feminism: Challenging connections between settler colonialism and heteropatriarchy. Feminist Formations, 25(1), 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/ff.2013.0006

- Barker, J. (2019). Confluence: Water as an analytic of Indigenous feminisms. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 43(3), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.17953/aicrj.43.3.barker

- Bawaka Country, Wright, S., Suchet-Pearson, S., Lloyd, K., Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr-Stubbs, M., Ganambarr, B., & Maymuru, D. (2015). Working with and learning from Country: Decentring human author-ity. Cultural Geographies, 22(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474014539248

- Bédard, R. E. M.-K. (2017). Keepers of the Water: Nishnaabe-kwewag speaking for the Water. In D. Christian & R. Wong (Eds.), Downstream: Reimagining Water (pp. 89–106). Wilfred Laurier University Press.

- Boj Lopez, F. (2017). Mobile archives of Indigeneity: Building La Comunidad Ixim through organizing in the Maya diaspora. Latino Studies, 15(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-017-0056-0

- Brayboy, B. M. J. (2005). Toward a tribal critical race theory in education. The Urban Review, 37(5), 425–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-005-0018-y

- Chavana, A. (2019). Reclaiming tribal identity in the Land of the Spirit Waters: The Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan Nation. NACCS 2019 Proceedings Complete, 5, 21–40.

- Chavana, A. (2023). Reclaiming tribal identity in the Land of the Spirit Waters: The Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan Nation [Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota]. University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy. https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/258711

- Chiblow, S. (2019). Anishinabek women’s Nibi Giikendaaswin (Water Knowledge). Water, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/w11020209

- Christian, D., & Wong, R. (Eds.). (2017). Downstream: Reimagining Water. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Colín, E. (2014). Indigenous education through dance and ceremony: A Mexica palimpsest. Springer.

- Corntassel, J., Chaw-win-is, & T’lakwadzi. (2009). Indigenous storytelling, truth-telling, and community approaches to reconciliation. ESC: English Studies in Canada, 35(1), 137–159. https://doi.org/10.1353/esc.0.0163

- Cotera, M. E., & Saldaña-Portillo, M. J. (2014). Indigenous but not Indian?: Chicana/os and the politics of Indigeneity. In R. Warrior (Ed.), The world of Indigenous North America (pp. 549–568). Routledge.

- de Finney, S., Sam, S.-R., Adams, C., Andrew, K., McLeod, K., Lewis, A., Lewis, G., Louis, M., & Haiyupis, P. (2019). Rekinning our kinscapes: Renegade Indigenous stewarding against gender genocide. Girlhood Studies, 12(3), 80–98. https://doi.org/10.3167/ghs.2019.120308

- Driskill, Q. L. (2004). Stolen from our bodies: First Nations Two-Spirits/Queers and the journey to a sovereign erotic. Studies in American Indian Literatures, 16(2), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/ail.2004.0020

- Driskill, Q. L. (2010). Doubleweaving Two-Spirit critiques: Building alliances between Native and Queer studies. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 16(1–2), 69–92. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2009-013

- Driskill, Q. L., Finley, C., Gilley, B. J., & Morgensen, S. L. (Eds.). (2011). Queer Indigenous studies: Critical interventions in theory, politics, and literature. University of Arizona Press.

- The Edwards Aquifer Website. (2022). Introduction to the Edwards Aquifer. https://www.edwardsaquifer.net/intro.html

- Estes, N. (2019). Our history is the future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the long tradition of Indigenous resistance. Verso Books.

- Fast, E., Lefebvre, M., Reid, C., Deer, B. W., Swiftwolfe, D., Clark, M., Boldo, V., Mackie, J., & Mackie, R. (2021). Restoring our roots: Land-based community by and for Indigenous youth. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 16(2), 120–138. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v16i2.33932

- Garza, M. (n.d.). White Shaman Panel: The Coahuiltecan Creation journey. Indigenous Cultures Institute. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from https://ymlp.com/zf3MyO

- Gobierno de México. (2019, July). Salvatierra, Guanajuato. Secretaría de Turismo. https://www.gob.mx/sectur/articulos/salvatierra-guanajuato

- Gough, N., Gough, A., Appelbaum, P., Appelbaum, S., Doll, M. A., & Sellers, W. (2003). Tales from Camp Wilde: Queer(y)ing environmental education research. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 8(1), 44–66. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/237

- Hunt, S. (2018). Embodying self-determination: Beyond the gender binary. In M. Greenwood, S. De Leeuw, & N. M. Lindsay (Eds.), Determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health (2nd ed., pp. 22–39). Canadian Scholars.

- Hunt, S., & Holmes, C. (2015). Everyday decolonization: Living a decolonizing Queer politics. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 19(2), 154–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2015.970975

- Indigenous Cultures Institute. (2022). Sacred sites. https://indigenouscultures.org/sacred-sites/

- King, T. (2003). The truth about stories: A Native narrative. House of Anansi Press.

- Konsmo, E. M., & Recollet, K. (2019). Afterword: Meeting the Land(s) where they are: A conversation between Erin Marie Konsmo (Métis) and Karyn Recollet (Urban Cree). In L. T. Smith, E. Tuck, & K. W. Yang (Eds.), Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education: Mapping the long view (pp. 238–251). Routledge.

- Kumashiro, K. K. (2002). Troubling education: “Queer” activism and anti-oppressive pedagogy. Psychology Press.

- Laing, M. (2021). Urban Indigenous youth reframing Two-Spirit. Routledge.

- Leon, A. Y., & Nadeau, D. (2018). Embodying Indigenous Resurgence. In S. Batacharya & Y.-L. R. Wong (Eds.), Sharing breath: Embodied learning and decolonization (pp. 55–82). AU Press.

- Martuwarra RiverOfLife, Unamen Shipu Romaine River, Poelina, A., Wooltorton, S., Guimond, L., & Sioui Durand, G. (2022). Hearing, voicing and healing: Rivers as culturally located and connected. River Research and Applications, 38(3), 422–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3843

- Middleton-Manning, B. R., Gali, M. S., & Houck, D. (2018). Holding the headwaters: Northern California Indian resistance to state and corporate Water development. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society, 7(1), 174–198. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/30411/23019

- Montes, P. (2022). Picking blue dawns: Community epistemologies, dreams, and (re)storying Indigenous autoethnography. Texas Education Review, 10(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.26153/tsw/41909

- Morgensen, S. L. (2011). Spaces between us: Queer settler colonialism and Indigenous decolonization. University of Minnesota Press.

- Muñoz, M. (2018). River as lifeblood, River as border: The irreconcilable discrepancies of colonial occupation from/with/on/of the frontera. In L. T. Smith, E. Tuck, & K. W. Yang (Eds.), Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education: Mapping the long view (pp. 62–81). Routledge.

- Nxumalo, F. (2016). Towards “refiguring presences” as an anti-colonial orientation to research in early childhood studies. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(5), 640–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1139212

- Nxumalo, F., & Montes, P. (2021). Pedagogical commitments for climate justice education. Connected Science Learning, 3(5). https://doi.org/10.1080/24758779.2021.12318704

- Nxumalo, F., & Montes, P. (2023). Encountering creative climate change pedagogies: Cartographic interruptions. Research in Education, 117(1), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/00345237231207493

- Nxumalo, F., & Villanueva, M. (2019). Decolonial Water stories: Affective pedagogies with young children. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 7(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.58295/2375-3668.1390

- Nxumalo, F., & Villanueva, M. T. (2020). Listening to Water: Situated dialogues between Black, Indigenous and BlackIndigenous feminisms. In C. A. Taylor, C. Hughes, & J. B. Ulmer (Eds.), Transdisciplinary feminist research: Innovations in theory, method and practice (pp. 59–75). Routledge.

- Ramirez, R. K. (2007). Native hubs: Culture, community, and belonging in Silicon Valley and beyond. Duke University Press.

- Richter, B. D., Abell, D., Bacha, E., Brauman, K., Calos, S., Cohn, A., Disla, C., Friedlander O’Brien, S., Hodges, D., Kaiser, S., Loughran, M., Mestre, C., Reardon, M., & Siegfried, E. (2013). Tapped out: How can cities secure their Water future? Water Policy, 15(3), 335–363. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2013.105

- Saldaña-Portillo, M. J. (2016). Indian given: Racial geographies across Mexico and the United States. Duke University Press.

- Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 1–25. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/22170

- Simpson, L. B. (2017). As we have always done: Indigenous freedom through radical resistance. University of Minnesota Press.

- Smith, A. (2010). Queer theory and Native studies: The heteronormativity of settler colonialism. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 16(1–2), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2009-012

- Smith, L. T., Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2019). Introduction. In L. T. Smith, E. Tuck, & K. W. Yang (Eds.), Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education: Mapping the long view (pp. 1–23). Routledge.

- Spillett, T. (2021). Gender, Land, and place: Considering gender within Land-based and place-based learning. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature & Culture, 15(1), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1558/jsrnc.39094

- Sumara, D., & Davis, B. (1999). Interrupting heteronormativity: Toward a Queer curriculum theory. Curriculum Inquiry, 29(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/0362-6784.00121

- Texas Hill Country Water Resources. (2013). Edwards hydrologic geology: Edwards aquifer system of central Texas. https://txhillcountrywater.wp.txstate.edu/groundwater/edwards-hydrologic-geology/

- Tuck, E., McKenzie, M., & McCoy, K. (2014). Land education: Indigenous, post-colonial, and decolonizing perspectives on place and environmental education research, Environmental Education Research, 20(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.877708

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630

- Wesley, S. (2014). Twin-Spirited woman: Sts'iyóye smestíyexw slhá:li. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1(3), 338–351. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2685624

- Wilson, A. (2008). N′tacimowin inna nah′: Our coming in stories. Canadian Woman Studies/Les cahiers de la femme, 26(3–4), 193–199. https://cws.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/cws/article/view/22131

- Wilson, A. (2018a). Skirting the issues: Indigenous myths, misses, and misogyny. In K. Anderson, M. Campbell, & C. Belcourt (Eds.), Keetsahnak: Our missing and murdered Indigenous sisters (pp. 161–174). The University of Alberta Press.

- Wilson, A. (with Laing, M). (2018b). Queering Indigenous education. In L. T. Smith, E. Tuck, & K. W. Yang (Eds.), Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education: Mapping the long view (pp. 131–145). Routledge.

- Wilson, A., Murray, J., Loutitt, S., & Scott, R. N. S. (2021). Queering Indigenous land-based education. In J. Russell (Ed.), Queer ecopedagogies: Explorations in nature, sexuality, and education (pp. 219–231). Springer.

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.

- Yazzie, M., & Baldy, C. R. (2018). Introduction: Indigenous peoples and the politics of Water. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 7(1), 1–18. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/30378