ABSTRACT

The seminal spending review (SR) theoretical framework by Catalano & Erbacci [2018. A theoretical framework for spending review policies at a time of widespread recession. OECD Journal on Budgeting 17(2), 9–24] draws on the cutback management and related academic literature to articulate the first theory for explaining the ability of medium-term SRs conducted after the global financial crisis of 2008 to effect targeted savings. This literature is however dominated by advanced economies with sophisticated public financial management systems. Comparatively little attention, however, has been paid to theoretical perspectives on developing countries, like South Africa. This article applies this theoretical framework by Catalano and Erbacci to the South African SR initiative in order to interrogate its theoretical and empirical relevance. Proposals are made for enhancing the operationalisation of the organisational and process dimensions of C&E’s theoretical framework to lay a foundation for future empirical research and its policy implications for South Africans SRs are explored.

1. IntroductionFootnote1

Spending reviews (SRs) have been introduced as part of broader public finance management (PFM) reforms in many advanced economies such as Canada in 1994, Australia in 1995, the United Kingdom in 1998 and Italy in 2012 (Van Nispen, Citation2016), often under conditions of fiscal austerity. South Africa (SA) is one of few developing countries that has institutionalised SRs (Engela, Citation2023).

In SA, SRs commenced initially with broad objectives aimed at improving the effectiveness and efficiency of government spending, led by the Government Technical Advice Centre (GTAC). Between 2013 and 2023, more than 220 spending reviews have been undertaken, which have contributed ‘to the adjustment of programmes’, and identification of ‘instances where policy goals are underfunded and where savings might be achieved’ (GTAC, Citation2021:nd). Many of these SR reports and their associated costing models are published on the GTAC website https://www.gtac.gov.za/pepa/, along with practice guidelines, training materials and conference proceedings, creating a body of practitioner knowledge. In response to constraints around institutional maturity, political oversight, the quality and availability of data, and most crucially, the skills deficits of officials, a standardised, modularised six-step methodology was developed, comprising in-depth institutional and policy evaluation, detailed expenditure analysis and cost modelling (Engela, Citation2023).

The politico-administrative context in SA has engendered a review process largely focussed on improving shortcomings in programme design and implementation undermining public spending efficiency and developmental impact (Allen & Clifton, Citation2023). The SR process – unlike many other global counterparts – has not to date been driven by top-down savings targets (Engela, Citation2023). This has been partly attributed to the limited range of SR topics and budget coverage relative to the level of savings required (Allen & Clifton, Citation2023). However, due to intensified structural fiscal consolidation pressures and the need for fiscal space for new spending priorities, the 2024 National Treasury guidelines envisage significant expenditure baseline reductions over the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) period and require national and provincial government departments to conduct SRs to scrutinise their baselines to identify efficiency gains and savings. These SRs should ‘cover a significant proportion of the department’s budgets such that the resultant efficiency gains have a material impact on the department’s overall baseline (National Treasury, Citation2023:3). It would be enormously useful for the second fiscal consolidation driven phase of SA’s SR initiative to draw, where relevant, on the incipient body of SR theory to explain the circumstances under which SRs have successfully achieved their objectives and identify key success factors in changing the actual practice of government budgeting to realise comprehensive savings.

While there is a growing body of practitioner-oriented knowledge (Doherty & Sayegh, Citation2022), academic research on the dimensions defining SRs and the factors influencing their performance remains sparse (Agasisti et al., Citation2015). A seminal theoretical framework for medium-term SRs by Catalano & Erbacci (Citation2018) draws on the cutback management and related academic literature to explain savings outcomes of SRs initiated after the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008, and their performance in decreasing public expenditure. C&E acknowledge as a limitation the paucity of empirical evidence validating the results of the literature on which they base their theoretical framework, and highlight the need for detailed empirical research, including qualitative case studies, to test the different elements of their theory and its ramifications for SR design. Theempirical application requires ascertaining whether their theory is applicable to a particular case (such as SA), and if so, whether the relevant constructs and associated observable variables can be practically operationalised – an endeavour to which this article seeks to contribute.

Theory can be defined as ‘an explained set of relationships’ (Wacker, Citation2008:6) and as ‘a collection of assertions, both verbal and symbolic, that identifies what variables [constructs] are important for what reasons, specifies how they are interrelated and why, and identifies the conditions under which they should be related or not related’ (Campbell, Citation1990:64). In practice, the notion of theory is often confused with related concepts such as conceptual frameworks, models, paradigms, philosophies and methodologies (Zongozzi, Citation2020). This article uses the terms theory and theoretical framework interchangeably.

The literature on which C&E draw is dominated by advanced economies with fairly sophisticated PFM systems, with comparatively little attention paid to SRs in developing countries. Yet should developing country governments such as SA choose to emulate advanced economy counterparts in adopting and adapting SRs, the factors underpinning the success or otherwise of SRs, and how these dynamics and SR outcomes might vary in developing country contexts, should clearly be understood.

Drawing on the extensive international experience and the theory building norms derived from contemporary philosophy of science literature, this article analyses the relevance of C&E’s theoretical framework, its assumptions and boundary conditions for SRs in SA. The first section reviews different types of SRs and critical factors for their design and successful implementation. The second and third sections explore the importance of theory building for the PFM discipline and how C&E’s framework could be operationalised in the South African context. This frames the subsequent analysis of the implications of the C&E framework for South African SRs. The article concludes by exploring policy insights flowing from C&E’s framework for the design and implementation of future SRs in SA.

2. Spending reviews: An evolving concept

The United Kingdom Public Expenditure Survey in the 1960s and the Australian Portfolio Management and Budget Reform programmes in the 1980s are precursors to the contemporary SR. Since the 2008 GFC, the prevalence of SRs in advanced economies has increased, with 31 out of 37 OECD countries conducting SRs, of which 65% do annual reviews and 35% do so periodically (OECD, Citation2021). There have also been a few instances of SR institutionalisation in developing countries such as Indonesia (Kristiantoro & Basuki, Citation2018, Ruslandi, Citation2020) and SA.

The academic literature however lacks consensus on what the term entails (Hawkesworth & Klepsvik, Citation2013; Catalano & Erbacci, Citation2018). This ambiguity arises partially from the multidisciplinary nature of the SR concept, which straddles the fields of performance budgeting, PFM reform, cutback management, organisational change and policy evaluation (Catalano & Erbacci, Citation2018). The concept has also evolved over time and in response to different contexts with methodologies, institutional configurations and roles of the various institutional stakeholders varying markedly.

In delimiting the explanandum of their theoretical framework (i.e. the phenomenon under investigation), C&E adopt the OECD’s definition of a SR as a type of ‘evaluation, commissioned ex ante, with the objective to identify and extract non-linear savings through the budget process’ (OECD, Citation2011:3). This definition is consonant with Hawkesworth & Klepsvik’s perspective of SRs as ‘assessments of the strategic orientation of programmes and/or the efficiency of spending, and are broadly used to reduce and/or (re)allocated budgetary expenditures’ (Citation2013:107), Robinson’s view of SRs as the formulation and implementation of savings measures based on a systematic supervision of the expenditure budget baseline (Citation2014:3), and Vandierendonck’s characterisation of SRs as ‘coordinated and in-depth analysis of baseline expenditures with the prime objective to detect efficiency savings and opportunities for cutting low priority or ineffective expenditures, for example by examining consequences of alternative funding levels’ (Citation2014:13). The generation of quantified savings opportunities and alternative funding levels differentiates the SR from a policy evaluation or its earlier analytical predecessor, the Public Expenditure Review (PER), a budget analysis tool with a broader remit employed since the 1980s to enhance programme effectiveness and value for money (World Bank, Citation1998).

C&E’s SR definition emphasises the ex ante (i.e. prospective) nature of SRs since they are undertaken before spending on programmes takes places, rather than afterwards (ex post), as is generally the case in policy evaluations or performance auditing (Vandierendonck, Citation2014). The term non-linear refers to targeted savings from specific programmes rather than uniform, across-the-board cuts in spending. Many SRs set specific budgetary savings targets (Robinson, Citation2014), but this has not historically been the case in SA. Given the more comprehensive coverage required by the National Treasury regulations for the 2024 MTEF discussed above, this may change in the future.

C&E distinguish between medium-term and long-term SRs, the former relating to savings for fiscal consolidation and the latter to change the composition of public expenditure. They restrict the boundary conditions of their theory (i.e. the parameters defining the scope and applicability of their theoretical framework) exclusively to medium-term SRs after the 2008 GFC ‘explicitly implemented to address problems of fiscal consolidation at a time of widespread recession’ (Catalano & Erbacci, Citation2018:13). They contend that this specification obviates ‘a possible misunderstanding (the use of spending reviews merely to direct spending on new priorities – as it was in many cases before the financial crisis)’ and centres their research ‘on the adoption of SRs as strategy of cutback management to address problems of fiscal consolidation’ (Catalano & Erbacci, Citation2018:10). C&E accordingly excludes from their literature review all SRs not specifically focussed on fiscal consolidation or where the SR is merely an analytical vehicle and not the prime focus of study.

Their focus on medium term rather than long-term SRs would seem to suggest that the savings identified should be realised, and hence measurable, within three to five years, but C&E do not attach explicit timeframes to their definition of medium-term SRs. It is also not completely clear from their definition whether it applies only to institutionalised and repeated annual or periodic SR exercises over the medium term, or also includes ad hoc once-off budget review exercises such as SRs in Italy and Spain which were once-off interventions to conform to the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact (Van Nispen, Citation2016). Clarifying these boundary conditions would facilitate the identification of SRs falling within the domain of C&E’s theory and preempt misapplication beyond its intended scope.

C&E’s definition clarifies that the recommendations of SRs are actioned during the routine budget process of government. While budget processes around the world tend to focus mainly on new spending proposals, often bogged down by incrementalist inertia (Robinson, Citation2014), SRs – by contrast – redirect attention to the baseline (i.e. budget proposals for existing policies and programmes). In SA, the link between SR recommendations and the budget process has historically been more tenuous. Because of skills and time constraints in the National Treasury, the responsibility for conducting SRs was located in GTAC, largely executed by specialist consultants following the standardised methodology, and overseen by project oversight committees consisting mainly of officials from the National Treasury and the relevant line department (Engela, Citation2023).

Because the OECD definition adopted by C&E characterises SRs as systematic analyses of budget baselines to yield potential savings that can be used to reduce or reallocate public expenditure, Van Nispen (Citation2016) argues that similar budget review exercises which propose additional or new spending fall outside the definition of an SR, and are in fact PERs, for example the Australian and Irish initiatives. In the same vein, Robinson (Citation2014) avers that what were termed as SRs in the UK before 2006 paid scant attention to the interrogation of baselines to generate savings rather than allocating incremental expenditure increases, and while they were nominally called SRs, in fact fell outside the definition of an SR as defined by C&E.

The analytical waters in recent years have been muddied by the expansion of SRs over time to incorporate broader objectives. Bova et al., for instance, are emphatic that SRs ‘are not tools to cut the budget’ despite the ‘stigma’ (Citation2020:51) attached to these during the aftermath of the 2008 GFC. They argue that SRs have evolved to incorporate objectives such as spending reprioritisation or identification of efficiency savings. On the other hand, PERs have also began to pursue fiscal consolidation, e.g. a Kenyan PER which explicitly identified and quantified potential savings in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic (World Bank, Citation2020).

While some SRs in SA have been explicitly savings oriented, most fall outside the SR definition employed by C&E, being in essence PERs, as defined earlier. Nonetheless, there are factors that may impel them to evolve into comprehensive savings-oriented SRs. Intensified pressures for fiscal consolidation in the aftermath of a decade of state capture from 2010 to 2020, the devastating economic and fiscal impact of the coronavirus pandemic and sluggish economic growth since may increasingly place demands on South African SRs to achieve targeted public expenditure cuts to contain debt and to free up fiscal space for new spending priorities, rather than across-the-board cuts occasioned by an expenditure ceiling, which has been the practice of the National Treasury hitherto. While the first generation of SRs in SA in the main were not congruent with the definitions and boundary conditions of C&E’s theory, the second generation SRs appear to align more closely (Engela, Citation2023).

From a theory building perspective, precise definitions and constructs enable the accurate identification of model cases i.e. instances which are without doubt examples of the phenomenon under study and to which a theory would apply (Zongozzi, Citation2020). As argued below, while C&E’s definition and boundary conditions are compelling from a nascent theory building perspective, clarification would assist interpretation and empirical operationalisation of their framework.

3. Theory building in PFM

The centrality of theory in applying the scientific method has led academic commentators to contend that ‘research findings presented outside the context of a particular theory or combination of theories is meaningless’ (Zongozzi, Citation2020:2). Across many social sciences, however, there is little consensus about what constitutes a theory and the characteristics of a good theory (Wacker, Citation2008; Zongozzi, Citation2020) – and PFM is no exception. An International Working Group on Managing Public Finances (IWGMPF) observed that the PFM discipline ‘finds itself without a strong theoretical or empirical anchor for its practical recommendations’ (NYU Wagner, Citation2020:17), having instead been driven by strong normative PFM conventions and frameworks relating to the operational performance of PFM processes, a common professional language and frame of reference, international standards and professional associations in certain PFM subgroups (such public sector accounting, auditing, internal audit). They posit that the dominance of PFM practitioner consensus, rather than theory or empirical evidence, has resulted in a self-referential, disciplinary ‘closed’ system.

The IWGMPF advocate that PFM conventions should meet the criterion of rationality in the sense of being based on ‘accepted theory or other logic’ (NYU Wagner, Citation2020:45), supporting a more ‘open’ system where knowledge and learning outside of the PFM system also shape PFM conventions. Building the theoretical and the empirical evidence foundations for PFM conventions and PFM processes (such as SRs) would therefore be of interest to academics and PFM practitioners alike.

The PFM discipline and its practices still however tend to be primarily shaped by powerful normative conventions encapsulating tacit learning and fairly narrowly defined objectives (NYU Wagner, Citation2020). In developing countries reliant on foreign assistance, these conventions are often reinforced by international developmental agencies and donors. Despite the more recent movement towards more context-specific problem-solving adaptive reform approaches (Andrews, Citation2013), the dynamics of isomorphism render a generalisable theory-based approach to SRs relevant, especially in developing counties. Isomorphism refers to ‘the pressure to imitate organisational characteristics from one organisational setting to another’ (Andrews, Citation2008, 381). Drawing on new institutional theory, Kristiantoro & Basuki (Citation2018), for example, identify three factors promoting isomorphism in the institutionalisation of Indonesian SRs after 2012: external pressures from legal compliance requirements and the influence of the OECD (coercive isomorphism), organisations’ inclination to attempt to emulate similar successful organisations where the goals of the organisations are not clearly defined (mimetic isomorphism) and internal stakeholders’ desire to adopt good practices to improve performance and professionalism, often encouraged by consultants or specialists (normative isomorphism).

The IWGMPF distinguish the broader concept of ‘managing public finance’ (as encompassing the substance of fiscal policy goals, objectives and outcomes) from PFM which has a narrow purview ‘delimited as the institutional arrangements that support public finance goals’ (NYU Wagner, Citation2020:10). While public finance policy goals and outcomes are amenable to theorisation, the question may be raised as to the extent to which PFM with its focus on on practices, conventions, rules and procedures would lend itself to theory building. While certain elements of PFM may be not be amenable to theorisation, this is not the case for SRs for fiscal consolidation as defined by C&E. Theory building requires the synthesis of three principal attributes, against which C&E’s theoretical framework can be assessed:

A collection of constructs and variables explaining a relatively general set of phenomena under study;

Their interrelationships expressed as propositions which explain and/or predict the characteristics and behaviour of these phenomena, and

The psychological, economic, and social dynamics which frame the identification of these factors and the postulated causal relationships (George & Jones, Citation2000).

As the phenomena to be explained or predicted within certain boundary conditions (the explanans), savings realised by SRs can be measured. The underlying factors and conditions accounting for the savings realised and the relationships between them can also be specified, measured and tested.

Theoretical constructs are high level, intangible abstractions developed to elucidate the phenomenon of interest, but most often cannot be directly measured (e.g. political will, trust, resistance to change). Variables are the observable proxies which are operationalised in empirical research, assessed and in some cases measured, from which empirical referents for the construct can be derived and whose presence demonstrate the occurrence of the underlying construct itself (Zongozzi, Citation2020). Selection of measures based on unclear or ambiguous definitions can result in contradictory empirical testing results. Similarly, the domain of the theory informs the selection of sampled cases to test the theory empirically. If the theory’s domain is vague then the sample may not be representative of that underlying theoretical domain and hence biased (Wacker, Citation2008).

Early stages of theory building generate models in which the attributes of phenomena across various categories correlate with the outcomes of interest. As empirical studies clarify the contradictions and confusion inherent in descriptive theory, normative theory emerges, based on propositions of causality (Carlile & Christensen, Citation2004). As discussed below, C&E’s theoretical framework, still in the embryonic states of theory formulation, complies with the first two attributes of a theory, but only partially with the third, since it does not yet postulate causality.

It is important to note that theories provide explanations or predictions relative to specific contexts and therefore may only be generalisable to similar context (Zongozzi, Citation2020). Whereas C&E delimit the applicability of their constructs (countries undertaking SRs with the intention to generate savings) in a particular time period (post the GFC in 2008–9), the issue of where their theory is applicable is not explicitly addressed. While they acknowledge the importance of social factors, C&E are less explicit about the economic and psychological boundary conditions which demarcate their theoretical domain (discussed further in the section below).

Extending C&E’s theoretical framework to SRs for reprioritisation or PERs would be challenging since savings resulting from SR-induced reprioritisation or PERs might be harder to measure in practice since public money is fungible, the reprioritisation may take place over a longer timeframe and other exogenous factors may also intervene, such as changing political priorities. Since SRs for reprioritisation and PERs may take place at any phase of the business cycle, not just during recession as specified by C&E, this relaxation of boundary conditions complicates the identification of relevant cases for empirical testing. Moreover, the urgency with which savings need to be identified may not play such a pivotal role as in the case of fiscal consolidation.

Like other forms of public policy evaluation, SR theory building faces the challenge of attributing causality between the SR and the savings achieved, and of the ‘counterfactual’ which refers to the inherently unobservable situation which would have prevailed anyway without the SR, or if some alternative intervention had been implemented (Vandierendonck, Citation2014). Van Nispen concedes that the evidence causally linking the recommendations of SRs with ‘smart’ cuts (i.e. evidenced-based targeted cuts rather than across the board cuts) is lacking (Citation2016:494). SRs are often implemented as part of broader PFM reforms (such as performance budgeting, MTEFs and government-wide monitoring and evaluation systems) which complicates causality attribution since they all aim to improve public spending performance by aligning funding decisions more closely with government policy priorities (allocative efficiency) and enhancing the development impact of public expenditure levels (technical or operational efficiency) (Vandierendonck, Citation2014).

4. Assessment of the C&E theoretical framework

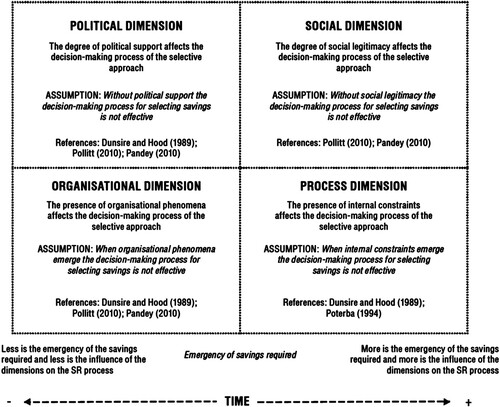

The phenomenon under study in C&E’s novel framework is the ability of the SR to generate targeted savings and selective cuts. C&E assert that four dimensions (political, social, organisational and process) and one dynamic element (time) condition the performance of SRs aimed at realising savings, summarised in ().

Figure 1. Theoretical framework for the spending review (Catalano & Erbacci Citation2018:18).

These five constructs are underpinned by associated hypotheses linking those constructs to the effectiveness of SRs:

The degree of political support affects the SR’s ability to generate targeted cuts. The greater the political commitment, the greater the SR decision-makers’ latitude to take far reaching, politically unpalatable decisions. An observable variable to operationalise this construct could be the degree of participation by the Office of the President or Prime Minister in the SR process.

The degree of social legitimacy affects the SR decision-making process. Without strong social legitimacy, SR decision-makers may not have the power to take unpopular decisions like selective cuts.

Certain organisational phenomena can render the SR process ineffectual, such as divergent objectives and rationalities of the leadership, resistance to change, bureaucratic barriers to the implementation of SR recommendations across ministries and agencies, and isomorphism which relapses into a recidivist expenditure orientation rather than a performance or outcomes orientation (e.g. the Italian SR case discussed below).

Internal constraints within the organisation(s) targeted for the SR such as regulatory and operational problems can affect the SR decision-making process. C&E, as discussed below, do not provide more detail on what these regulatory or operational problems might be.

Time relates to the urgency of the savings required, which may affect each of the other dimensions of the framework simultaneously. The less time available for a SR and the greater the urgency of the savings required, the greater the challenge of managing the other four dimensions.

C&E suggest that detailed empirical research on the inter-relationship among the four dimensions and the dynamic time variable is required to refine and validate their emergent theoretical framework.

While some abstract concept constructs (such as definitions) and theory relationship constructs are well defined in the C&E’s framework, others are less so. The political support, social legitimacy and time dimensions are fairly self-evident. However, the difference between the organisational and the internal constraint dimensions is not very clear. Instead of a rigorous definition of the organisational phenomena comprising their third dimension, C&E instead provide examples. This makes the classification of constructs such as administrative culture, and variables such as the availability, quality or asymmetry of information difficult to categorise and to systematically test the relationships among them.

A crucial set of variables for SRs for identifying different levels of savings and modelling their service delivery impact and distributional outcomes is the availability, timeliness, completeness and quality of performance information. It is unclear whether information would relate to C&E’s process dimension (as a constraint) or the organisational dimension (in the sense of its relationship to other performance budgeting PFM reforms and use in the medium-term budget process). Similarly, there is some ambiguity within C&E’s framework in locating the capacity and skills to implement SRs (of officials as well as foreign and local consultants and advisors). Clarification of how key variables such as information and capacity relate to C&E’s five dimensions would assist researchers seeking to test their theoretical framework empirically.

The ‘organisational dimension’ could be re-cast as the ‘institutional dimension’ with the unit of analysis specified as the SR process itself, with accompanying governance and institutional arrangements. The process dimension could be more aptly renamed as ‘internal constraint dimension’ and refer expressly to the constraints on SR implementation and savings realisation in the organisational unit(s) which are the focus of the SR. Issues relating to the political and administrative leadership of the SR process and the relationship with line departments could then be subsumed under the organisational dimension, whereas factors pertaining to skills, institutional capability, performance information and regulatory constraints would fall within the reconfigured internal constraint dimension.

Observable proxy variables (such as public opinion surveys) would need to be identified to operationalise C&E’s social legitimacy construct. Regrettably, these are not publicly available in SA on a regular basis. However, content analysis of social and mainstream media and submissions to Parliament by civil society during budget hearings could be used to capture public sentiment in relation to SRs and their recommendations. An alternative proxy indicator could be the proportion of seats in Parliament held by the governing party or the proportion of parliamentary votes in favour of budget appropriations effecting SR recommendations. In the South African context, changes in the term structure of government bond yields, the deviation of actual from projected deficit to GDP ratios announced in the MTEF, or changes in credit rating outlooks may also serve as reasonable proxies for the urgency of savings to be realised.

Although C&E acknowledge the importance of context, the impact of initial conditions is not well integrated into their theory – for instance difference in context between developing and advanced economies, nor is the link between SRs and other PFM reforms accounted for. Features of PFM systems supportive of SRs include sound annual budget processes, medium-term budget frameworks and methodologies for costing and accounting for savings. Doherty & Sayegh (Citation2022) contend that SRs can still be effective in countries with less mature PFM systems and capacity where these features may be absent, provided that the SR design takes this into account, for example through concentrating on the largest expenditure items, the greatest deviations from spending plans, or by adopting only specific elements of an SR (such as high level cross country benchmarking based on external information sources).

As noted earlier, causality among some of the relationship constructs at this early stage of theory building are still not clearly defined (for example, the relationship between social legitimacy and SR savings outcomes) and therefore the theoretical framework remains at this stage largely descriptive and explanatory rather than causal and predictive. Nonetheless, C&E’s theoretical framework generates a number of compelling policy recommendations for the design of SRs and are fertile areas of future research: using stakeholder engagement to bolster social legitimacy of SR recommendations, conducting regulatory reviews in parallel to the SR to alleviate internal organisational process constraints, proactively managing organisational phenomena such as internal and external resistance through change management practices, building relationships with senior political echelons such as the Prime Minister, Presidency and Ministry of Finance, and application of SRs rather than linear cuts when time and urgency constraints permit.

C&E’s theory, while explicitly acknowledging the role of politics in framing savings decisions, still adheres to the tacit assumption of largely rational, evidence-based, formal government decision-making, which has long been contested both in practice and in the academic literature harking back to Herbert Simon (Citation1955). In practice, other factors beyond evidence-based analysis may also profoundly influence the savings realised by SRs, and should be taken into account in theory building, especially where the informal institutions conditioning individual, organisational and stakeholder behaviours and practices are decoupled from formal ones.

In reflecting the tenuous link between evaluation practice in Canada and cabinet decisions, Dobell & Zussman – based on their personal experience of ad hoc and systematic SRs – assert that comprehensive, well considered cuts to the expenditure budget as a package are sometimes undermined by tight timeframes and political dynamics:

Decisions about cuts will likely be made arbitrarily, based on perceptions and beliefs – probably those of one strong individual enjoying the confidence and backing of the of the prime minister – about programme merits but, more importantly, also about the appropriateness of the activity as a responsibility of the federal government of the day. Again, perhaps the most one can hope (counterfactually?) is that an ongoing culture of respect for evidence and interest in outcomes will have shaped the opinions and perspective of that central individual in a way that promotes a broad public interest rather than ideologically-driven motivated reasoning pressing towards ever-smaller government’ (Citation2018:383–4).

This would constitute a form of ‘institutional decoupling’ where there is an institutional reconfiguration of outward form, but not of function, underlying institutional logic or informal administrative culture (Andrews, Citation2013). Institutional decoupling can manifest as a result of isomorphic pressures discussed earlier. Institutional logics refer to ‘the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality’ (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation1999:820).

Institutional logics can influence individual and organisational behaviours and hence their performance outcomes, with multiple, often contradictory logics competing for dominance (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation1999), for example the tensions between the rational, performance-oriented logic underpinning SRs and other related PFM reforms and prevailing logics which are incrementally focussed on expenditure and inputs (Andrews, Citation2013). For example, in the case study of the Italian SR in 2012, the formal legal basis of SRs did not find expression in the concrete day-to-day spending decisions: ‘ … the actual management of expenditure, in terms of operational efficiency and suitability of allocation, remain on a different and mutually non-communicating plane with respect to the complex procedural frameworks set up to achieve the final objective of rationalising and curbing expenditure’ (Goretti & Rizzuto, Citation2013:194). C&E also suggest that the Italian SR in 2012 tended to relapse to an expenditure orientation rather than a focus on performance and outcomes, suggesting institutional inertia which makes it difficult for SRs to displace the existing dominant institutional logics (Citation2018:19). The analysis of isomorphic pressures and institutional decoupling could yield important insights into the conditions under which SRs are likely to achieve or fall short of their objectives.

Key individuals may be ideologically biased rather than evidence-informed, and others might put their individual self-interest first in pursuit of fraudulent and corrupt gains and state capture. This is exacerbated in environments with few controls, few consequences for infractions and information asymmetry among organs of state, such as in SA during the state capture era. The scale, embeddedness and systemic nature of state capture in SA during the tenure of former President Zuma from 2009 to 2019 has been characterised by academic commentators as a creation of an informal parallel ‘shadow state’ that subverted the formal, constitutional state and parasitically extracted public resources to benefit an interlocking network of corrupt individuals with the support of former President Zuma and a cohort of other public sector officials (Swilling et al., Citation2017:3). In recent years, fiscal institutions themselves have been weakened, with heightened evidence of ‘institutional decoupling’: the MTEF – despite publicly stated commitments to the contrary – has repeated failed to force trade-offs or constrain bottom-up public sector wage bill pressures, and large spending priorities such as fee-free higher education have bypassed the intergovernmental budget process (Ajam, Citation2021). The Nugent Commission laid bare the attenuation of the capability of the South African Revenue Service by state capture even before the COVID-19-induced tax collapse (Nugent, Citation2018). This compromised the stability of the fiscal framework at the national level which spilled over to provincial and municipal governments. Unless the formal and informal institutional logics undermining the integrity of complementary fiscal institutions in SA are reversed and bolstered by political will, SRs’ ability to make meaningful targeted cuts in South African public spending – despite announcements of such intent in the 2023 MTBPS – will be severely limited.

Better integrating the new institutional theory literature into C&E’s theoretical framework (particularly in its political and organisational dimensions) could explicitly address the institutional decoupling of informal from formal PFM institutions (including SR instruments). Furthermore, incorporating constructs relating to institutional logics under informational constraints and asymmetry can provide theoretical scaffolding for the systematic analysis of the relationships among key SR stakeholders such as the Ministry of Finance, line ministries and the Office of the Prime Minister/President, which are crucial for SR outcomes. In the literature there is frequently an assumption that line ministries may have more SR relevant information than the Ministry of Finance, for instance. This may not necessarily hold true for developing countries like SA where line departments typically have greater capacity to collect and record data, but the Treasury or central budget office may have greater capacity for data analysis and modelling.

5. Implications for South African spending reviews

Shortcomings in other elements of South African PFM reform have reduced the potential impact of SRs thus far. Some of these relate to the internal constraints in C&E’s process dimension: failure to fully implement an integrated financial management system since 2005, insignificant systemic improvement in cost and management accounting systems and usage, and a persistent lack of capacity in national and provincial line departments and treasuries. Organisational dimension factors impacting on the efficacy of SRs include a supine Parliament demonstrably unable to exercise effective fiscal oversight (Ajam, Citation2020). Most notable has been the political dimension: the lack of political and managerial will to eliminate or reconfigure non-performing programmes.

As a policy implication flowing from their theoretical framework, C&E assert that SR governance structures should have ‘a strong relationship with the higher political hierarchies, such as the Prime Minister or the Minister of Finance’ (Citation2018:20) to ensure sufficient political support. This suggests that the evolution of South African SRs from more technically oriented, National Treasury-led exercises to comprehensive savings focussed reviews aimed at fiscal consolidation may well require more active support from the Presidency in SR governance structures.

C&E also suggest that regulatory reviews in parallel to SRs may alleviate some of the internal constraints (in the process dimension) limiting the scope of SRs and emphasise the need for change management strategies to address resistance to change. Both these insights would be important considerations for the next generation of SRs.

C&E’s social dimension highlights the importance of SR stakeholder engagements and public consultations. If targeted cuts of the required magnitude are to be achieved, much greater interaction with the South African Parliament and civil society will be required during the budget process in regard to SR savings recommendations which are likely to be contentious.

6. Concluding remarks

Further empirical research will be needed for validating C&E’s theoretical framework. To this end, their framework will need to be clarified in places so that its five constituent dimensions can be operationalised in terms of observable variables. This paper offers some suggestions on how this may be accomplished, which could facilitate empirical testing in SA and elsewhere. Despite its embryonic state, C&E’s framework appears to yield relevant policy implications on the design and implementation of the next generation of South African SRs. This article’s recommendations on the operationalisation of C&E’s theoretical framework also lays the basis for further empirical research on the second generation of SRs in SA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 I would like to thank Richard Allen, Mehleli Mpofu, Ronette Engela and Conrad Barberton for their insightful comments on previous drafts as well as the three anonymous peer reviewers.

References

- Agasisti, T, Arena, M, Catalano, G & Erbacci, A, 2015. Defining spending reviews: a proposal for a taxonomy, with applications to Italy and the UK. Public Money & Management 35(6), 423–30. doi:10.1080/09540962.2015.1083688

- Ajam, T, 2020. Future-proofing the state against corruption and capture: the performance of the parliamentary service in supporting effective legislative oversight in South Africa. Administratio Publica 28(2), 21–41.

- Ajam, T, 2021. Public finance and fiscal policy in South Africa. In A Oqubay, F Tregenna & I Valodia (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the South African economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 935–55.

- Allen, R & Clifton, R, 2023. From zero-base budgeting to spending review – achievements and challenges. Development Southern Africa, 1–17. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2023.2226164

- Andrews, M, 2008. The good governance agenda: beyond indicators without theory. Oxford Development Studies 36(4), 379–407. doi:10.1080/13600810802455120

- Andrews, M, 2013. The limits of institutional reform in development. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Bova, E, Ercoli, R & Vanden Bosch, X, 2020. Spending reviews: some insights from practitioners. European Commission Discussion Paper 135. https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/economic-and-financial-affairs-publications_en. Accessed 2 June 2022.

- Campbell, JP, 1990. The role of theory in industrial and organizational psychology. In MD Dunnette & LM Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. 2nd ed., Vol. 1. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA, 39–73.

- Carlile, P & Christensen, CM, 2004. The cycles of theory building in management research. Harvard Business School Working Paper. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/05-057.pdf. Accessed 18 August 2022.

- Catalano, G & Erbacci, A, 2018. A theoretical framework for spending review policies at a time of widespread recession. OECD Journal on Budgeting 17(2), 9–24.

- Dobell, R & Zussman, D, 2018. Sunshine, scrutiny and spending review in Canada, Trudeau to Trudeau: From programme evaluation and policy to commitment and results. Canadian Journal of Programme Evaluation 32(3), 371–93. doi:10.3138/cjpe.43184

- Doherty, L & Sayegh, A, 2022. How to design and institutionalize spending reviews. The International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Fiscal-Affairs-Department-How-To-Notes/Issues/2022/09/20/How-to-Design-and-Institutionalize-Spending-Reviews-523364. Accessed 20 November 2023.

- Engela, R, 2023. The development of a spending review methodology in a developing country context. Development Southern Africa, 1–17. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2023.2249022

- George, J & Jones, G, 2000. The role of time in theory and theory building. Journal of Management 26(4), 657–84.

- Goretti, C & Rizzuto, L, 2013. The spending review: use and abuse of a term. Italian Politics 28(1), 188–206.

- GTAC, 2021. About us. Retrieved from Government Technical Advisory Centre website: https://www.gtac.gov.za/pepa/about-us. Accessed 31 October 2022.

- Hawkesworth, I & Klepsvik, K, 2013. Budget levers strategic agility and the use of performance budgeting in 2011/12. OECD Journal on Budgeting 13(1), 105–40.

- Kristiantoro, H & Basuki, Z, 2018. The institutionalization of spending review in budgeting system in Indonesia. Jurnal Akuntansi dan Investasi 19(1), 36–53. doi:10.18196/jai.190190

- National Treasury, 2023. 2024 Medium Term Expenditure Framework technical guidelines. https://www.treasury.gov.za/publications/guidelines/MTEF%202024%20Guidelines.pdf. Accessed 22 March 2024.

- Nugent, R, 2018. Commission of Inquiry into Tax Administration at SARS Final Report. SARS Commission: http://www.inqcomm.co.za/Docs/media/SARS%20Commission%20Final%20Report.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2022.

- NYU Wagner, 2020. Advice, money, results: Rethinking international support for managing public finance, report by an International Working Group. New York University Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. https://wagner.nyu.edu/advice-money-results/about. Accessed 20 November 2023.

- OECD, 2011. Typology and implementation of spending reviews. OECD Senior Budget Officials Meeting on Performance and Results, GOV/PGC/SBO(2011)9. https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote = GOV/PGC/SBO(2011)9&docLanguage = En. Accessed 31 May 2022.

- OECD, 2021. Spending reviews. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi:10.1787/1c258f55-en.

- Robinson, M, 2014. Spending reviews. OECD Journal on Budgeting 2013/2, 1–37. doi:10.1787/budget-13-5jz14bz8p2hd

- Ruslandi B, 2020. Model of spending review integration: taking budget decision in Ministry of Health. International Journal of Governmental Studies and Humanities 3(1). http://ejournal.ipdn.ac.id/index.php/ijgsh. Accessed 30 July 2023.

- Simon, HA, 1955. A behavioural model of rational choice. Quarterly Journal of Economics LXIX, 99–118.

- Swilling, M, Bhorat, H, Buthelezi, M, Chipkin, I, Duma, S, Mondi, L & Friedenstein, H, 2017. Betrayal of the promise: how South Africa is being stolen. State Capture Project. https://pari.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Betrayal-of-the-Promise-25052017.pdf. Accessed 10 September 2022.

- Thornton, PH & Ocasio, W, 1999. Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations. American Journal of Sociology 105(3), 801–43. doi:10.1086/210361

- Vandierendonck, C, 2014. Public spending review: design, conduct, implementation. European Commission Economic Paper 4525. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/. Accessed 28 May 2022.

- Van Nispen, FK, 2016. Policy analysis in time of austerity: a cross-national comparison of spending reviews. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis 18(5), 479–501. doi:10.1080/13876988.2015.1005929

- Wacker, JG, 2008. A conceptual understanding of requirements for theory-building research: guidelines for scientific theory building. Journal of Supply Chain Management 44(3), 5–15.

- Wildavsky, AB, 1984. The politics of the budget process, 4th ed. Little Brown, Boston.

- World Bank, 1998. The impact of public expenditure reviews: An evaluation, Report No. 18573. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- World Bank, 2020. Kenya public expenditure review: Options for fiscal consolidation. World Bank Open Knowledge. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34052. Accessed 12 May 2022.

- Zongozzi, JN, 2020. A concept analysis of theory in South African open distance and e-learning research. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 1–15. doi:10.1080/02680513.2020.1743172