ABSTRACT

This article contributes from a sociology of knowledge perspective to the ongoing sociological debate about statistics produced by international organisations taking the Global Estimates of Forced Labour published by the International Labour Organization (ILO) as a case of international quantification. We ask: what stages of negotiation were involved in the transformation of a legal category into a statistical category of forced labour oriented towards political action? The analysis combines the historical reconstruction of the political and organisational processes behind the production of the estimates with the study of the measurement framework of forced labour. The qualitative case study is based on semi-structured expert interviews and ILO documents. Our results highlight the processes by which a legal category was made practicable for statistical work and thereby point to the specific arrangements and connections between law, statistics, and policy within international organisations. As we argue, the estimates have provided consistency to a fragile social construct that originated in the imperial context of the interwar period, and that was turned into a ‘visible’ social and global phenomenon of the twenty-first century.

Introduction

In 2005, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated the number of cases of forced labour worldwide for the first time at 12.3 million. The estimates were updated in 2012 to 20.9 million cases and in 2017 to 25 million (ILO, Citation2005a, Citation2012b, Citation2017). The quantitative gap between these figures raises sociological questions concerning the construction of the framework of measurement. Sociological research on the construction of statistics, especially in an international context, has expanded in recent years to cover more and more fields (see Mennicken & Espeland, Citation2019). However, in-depth analyses of the conditions of production of figures by international organisations, the concrete operations involved, as well as the institutional configurations in which they are embedded, are still scarce (see however Cussó, Citation2016; Wobbe & Renard, Citation2017). The present article contributes to this ongoing debate by We use a sociology of knowledge perspective by the ILO as a case in point of international quantification. Our goals and contributions are twofold: first, we reconstruct the genesis of the statistical category and explore the interface between statistical and legal expertise within the ILO. Second, by providing insights into the knowledge instruments involved in the reorientation of ILO campaigns against forced labour after 2000, we aim to demonstrate the specific role played by statistics in international organisations and their political action today.

Forms of work marked by violence, coercion, and dependencyFootnote1 have been summed up and legally codified by the ILO since 1930 under the category ‘forced labour’ (ILO Convention No. 29 (1930); ILO Convention No. 105 (1957); Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention). In this paper, we use the term forced labour to refer to the ILO’s legal or statistical category, but we refrain from employing it as a sociological category of analysis. In the context of the reorientation of the ILO at the end of the 1990s, campaigns against forced labour were supported by statistical expertise and the production of estimates. This article investigates 1) the specific quality of the statistical category, beyond and complementary to the legal category, and 2) to what extent the estimates were embedded in a broader political strategy against forced labour. What stages of negotiation were involved in the transformation of a legal category into a statistical category of forced labour oriented towards political action? Our findings highlight the processes by which a legal category was made practicable for statistical work and thereby point to the specific arrangements and connections between law, statistics, and policy within international organisations. We show how, on the one hand, the statistical category emerged, sui generis, in its own right, shaped by ILO statisticians, and how, on the other hand, it remained as close as possible to the legal definition. As we argue, the estimates have provided consistency to a fragile social construct that originated in the imperial context of the interwar period, and that was turned into a ‘visible’ social and global phenomenon of the twenty-first century. Examining this process reveals collectively shared (gendered) patterns of interpretation about what work is and what forced labour.

In the first part, we develop a conceptual framework and research design inspired by the historical sociology of knowledge in order to analyse the production of statistics by international organisations. Our methodological approach and data for the case study are presented thereafter. In the following section, we outline the organisation of legal and statistical expertise at the ILO and illustrate its specific temporality in the case of forced labour. We then turn to the findings of our study, by first reconstructing the genealogy of the Global Estimates and the historical as well as political impulses behind it. Subsequently, we analyse the concrete steps in the construction of a framework of measurement, including the lessons learned from qualitative studies, the construction of a statistical definition, the selection of indicators, and the standardisation of procedures of data collection. Using the concrete classification processes in the cases of forced begging and forced marriage as examples, we trace how statisticians shaped the framework of forced labour quantification by negotiating both statistical standards of classification and legal norms. The article ends with a discussion of the main results and concluding remarks on the heuristic value of statistical categories.

Conceptual framework and research design

Exploring the connections between legal and statistical knowledge

We use a sociology of knowledge perspective to address the practices involved in the production of international statistics. In particular, we draw on studies dedicated to statistics as a knowledge technology of classification, objectification and hierarchisation for the construction of political problems (see Antonelli, Citation2016), with a special focus on the policy domain of work (Berrebi-Hoffman et al., Citation2019; Vanderstraeten, Citation2006; Wobbe, Citation2012; Zimmermann, Citation2001). One aspect that has not yet been sufficiently explored by sociological research is the articulation between legal and statistical expertise in international organisations. Law and statistics are often analysed as two parallel, yet separate knowledge technologies of modern organisations (see Wobbe et al., Citation2017). This is as much the case in international organisations as it is in national bureaucracies. Legal and statistical knowledge are the products of different, partially autonomous social fields and professional expertise that follow their own logic, have their own rules of legitimacy, and speak their own languages. According to Pierre Bourdieu, the legal field is characterised by ‘a confrontation among actors possessing a technical competence (…) which consists essentially in the socially recognized capacity to interpret a corpus of texts sanctifying a correct or legitimized vision of the social world’ (Bourdieu, Citation1987, p. 817, emphasis in original). By contrast, the competences involved in statistical expertise imply the translation of qualitative and isolated phenomena into a numeric language that is easily transposable and readable in other social spheres. Whereas legal expertise draws its legitimacy both from ‘the positive logic of science and the normative logic of morality’, therefore ‘compelling universal acceptance’ (Bourdieu, Citation1987, p. 818), official statistics claim to be objective and neutral on the basis of an original combination between administrative and scientific logics (Desrosières, Citation1998, p. 71). What distinguishes numbers from other kinds of media is their permeability, combinability, and malleability (Heintz, Citation2007, p. 79). As a result, statistical and legal knowledge not only differ in their means and resources to achieve authority. The categories produced by both types of expertise also vary in their degree of circulation, normativity, and sanction in case of non-conformity. While legal statements must require interpretation by legal experts to be understood by lay people (Bourdieu, Citation1987), numbers are deemed immediately accessible to a wider audience.

Our goal in this article is not to challenge the separation and particularities of legal vs. statistical knowledge. Rather, we aim to explore their possible connections, especially the way in which statisticians draw on legal experts and their authority to interpret the law in order to build statistical frameworks of categorisation and measurement. Statistical classification implies the rigorous selection of criteria to allow clear-cut distinctions between phenomena prior to their measurement. According to Desrosières (Citation2001), these classification decisions build on previous or emerging ‘conventions of equivalence’ – firstly between heterogeneous, individual instances, and secondly between a case and the general category. These conventions may originate in law or be the result of statisticians’ work (Desrosières, Citation2001, p. 116). We understand ‘conventions’ in a sociological sense as patterns of interpretation and orientation for action that are based on the codification and solidification of a social consensus (on the concept of convention in the French pragmatist school of social sciences, see Diaz-Bone & Thévenot, Citation2010). The standardisation of classifications, definitions, methods, and instruments is not deterministic but negotiated among diverse socio-political actors who may follow different conventions and thus act on the basis of diverging interpretative schemes (Antonelli, Citation2016, p. 361). ILO statisticians had to deal with legal and statistical conventions of equivalence in order to produce the estimates of forced labour.

We argue that, because of their differences in terms of accessibility to a non-expert audience, the transformation of a legal into a statistical category served the ILO’s renewed strategy to combat forced labour after 2000. As numbers are easily transposable and seem easily understandable in contexts of communication that are not their context of emergence, statistical constructs like the estimates are designed to be shared with other fields of knowledge and action, ‘to be used as an instrument of proof’ (Desrosières, Citation1999, p. 127). Statistics have been ‘a privileged tool for translating semantic entities with still uncertain contours into categories for political action’ (Zimmermann, Citation2001, p. 16, own translation). Because it is thought to represent a pre-existing and exterior reality, quantification supports political programmes and allows ‘making decisions without seeming to decide’ (Porter, Citation1995, p. 8).

Moreover, as a political knowledge technology, statistics make ‘the social’ visible and available for political intervention (Köhler, Citation2008, pp. 75–76), and in the same movement, make the social operations and political standpoints behind statistical knowledge invisible. However, making certain things visible implies that other aspects have been excluded for the sake of international comparability. We will demonstrate how the estimates have been designed to draw public attention to the prevalence of forced labour in today’s global world.

Towards a historical sociology of international quantification

In relation to our first objective, a second goal of this article is to contribute to an emerging and ongoing sociological debate about statistics produced by international organisations (see e.g. Wobbe & Renard, Citation2017), and especially their role in international political campaigns. Roser Cussó’s work (Citation2016, Citation2020) has paved the way for a historical sociology of international quantification and calls for ‘more detailed analysis of the institutional particularities of quantification’ with regard to international intergovernmental organisations (IO) (Cussó, Citation2020, p. 55). Cussó identifies three distinctive elements of international quantification, in contrast to quantification by national producers: 1) the ‘standardization of international statistical methods and categories’; 2) ‘intergovernmental cooperation and technical assistance’; and 3) the ‘collection and publication of internationally comparable data by IO’ (Cussó, Citation2020, p. 2).

Building on the aforementioned historical-sociological approaches to knowledge and international quantification, our analytical framework combines the historical reconstruction of the political context and organisational processes that prompted the production of estimates with the sociological study of classification, the construction of an international measurement framework, and the encoding of specific cases as instances of forced labour. We aim to identify legal sources of origin, actors involved, the purpose of the inquiry, the definition of the phenomenal field, the source of the data and methodologies (Antonelli, Citation2016, pp. 362–364). The ‘opportunities of use’ (Antonelli, Citation2016, p. 364) of the estimates on the global and national level require further research and are not part of our analysis. We intend both to situate the production of estimates within broader political, organisational, and social processes, and to reconstruct the specific and contingent chain of events within the ILO as a producer of statistics. We also pay attention to the actors involved and their expertise and situate them within the specific institutional context of the ILO. ILO statisticians not only act within their logic of expertise and shared conventions but are also bound by the ‘consensual ethical objectives’ of the organisations’ mission (Cussó, Citation2016, p. 60). This constitutes a crucial difference compared to the claimed neutrality of civil servants in national administrations. Since its creation, ILO’s official mission has been the promotion of social justice as a means of building peace and improving labour and living conditions by setting social and labour standards (see Wobbe, Citation2020, p. 148). As we will see, the statisticians’ professional ethos combined with the organisations’ ethical objectives impacted classification decisions and the orientation of the estimates.

Methodology and data

With regard to methodological strategies, only few studies on quantification rely on ethnographic methods like direct observation of practices or interviews with statisticians (see however Boersma, Citation2020; Petzke, Citation2021). We conducted a qualitative, historical-sociological case study based on semi-structured expert interviews with current and former ILO staff. The interviewees were either members of the Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour (SAP-FL), of the FUNDAMENTALS Department, or of ILO programmes against forced labour in specific countries. Most of them held or still hold leading positions and were thus key actors in shaping the direction of their organisational structure as well as decision-makers in the construction of the statistical category of forced labour. They were involved in the negotiation processes around the operationalisation of the legal category into a measurement tool and took part in the implementation on the national level. Their personal profiles embody the specific intersection between professional expertise and the ‘ethical’ programme of the ILO: they combine an academic background in economy, mathematics and/or statistics with social activism, e.g. against child labour or in anti-slavery NGOs. As other international experts and staff members of international organisations, they

hold a strategic position, at the intersection between practitioners, policy-oriented researchers and academics. Not only are they experts in their field of intervention, but they are also experts in bridging different professional fields and in navigating between various institutional languages and configurations. (Louis & Maertens, Citation2021, p. 30)

The historical and institutional setting of the estimates: the ILO as a space of legal and statistical expertise

Since its creation in 1919, the ILO has contributed to the legal codification of international labour standards in the form of conventions and recommendations. Legal expertise was soon accompanied by the creation of administrative structures for scientific inquiries and the collection of international statistics in the framework of the ILO’s secretariat, the International Labour Office. Today, legal, economic and statistical expertise cohabit in the Office. The cooperation of labour lawyers and labour statisticians under the banner of social justice characterises this organisation.

The organisational logics of legal and statistical expertise at the ILO

The legal logic at the ILO consists of (1) standard-setting through translating political struggles into legal instruments of labour conventions, protocols (both binding for the member states after ratification), or recommendations, and (2) monitoring the implementation of international labour standards. The structure responsible for the discussion and adoption of standards is the International Labour Conference (ILC), the parliament of the ILO, in which governments, employers and workers are represented according to the tripartite organisation. The Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR), created in 1926, is in charge of observing the degree of compliance of national legislations and practices with ILO standards. The Committee drafts reports as well as direct requests to governments identifying implementation gaps or cases in which labour rights and principles are disregarded. However, it has no direct power to impose sanctions.

In addition to establishing and monitoring international labour standards, the ILO has been dedicated since its foundation to compiling internationally comparable statistics and establishing international classifications. Article 10 of the ILO constitution (part of the Treaty of Versailles, 1919) includes the ‘collection and distribution of information’ as a core mission of the organisation. The International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) started in 1923 as a forum of exchange and standard-setting for labour statisticians worldwide. Similarly to the ILC, the ICLS is a space of practiced tripartism involving representatives of governments – predominantly from labour ministries and national statistical offices – trade unions and employers’ organisations in the negotiations and decision-making processes. The encounters of ILO-internal and member states' expertise as well as external stakeholders’ expertise (e.g. regional or transnational NGOs and other interest groups) in this space are significant moments in which conventions of equivalence might be validated, re-institutionalised or challenged. The drafts, resolutions and guidelines concerning the standards of measurement set at ICLS meetings result from negotiation processes and consensus building to determine the social and political perception to be attributed to phenomena in the world of work. Therefore, ‘what was originally intended to facilitate the debate [international standards of classification] becomes an object of discussion in its own right’ (Piguet, Citation2018, p. 43, own translation). The classification schemes and definitions are used to develop national statistics (ILO, Citation1985, Art. 2) and, at the same time, form the basis for generating internationally comparable statistics (see Wobbe, Citation2020).

The particular temporalities of legal and statistical expertise on forced labour

In the field of work and labour market policies, statistical categorisation mostly precedes or is contemporary to legal codification (for the German national context, see Renard, Citation2019a; Zimmermann, Citation2015). At the international level, standards of statistical classification of industries, professions, accidents at work, strikes, labour and living conditions were already discussed and partly set by the ICLS in the interwar period (Kévonian, Citation2008, p. 98; Piguet, Citation2018, Citation2022). These discussions however implicitly focused on industrial work in metropolitan or independent countries. By contrast, the discussions that led to the adoption of Convention No. 29 against forced labour principally concerned work in colonised territories (Wobbe et al., Citation2023). The legal codification preceded the statistical categorisation that took place only in the 2000s. We assume that this particular temporality is linked to the colonial connotation of forced labour and its allocation to a specific field of action in the interwar period.

In the late 1920s, the category of forced labour was modelled by selected international experts and shaped by international discussions at the ILC, leading to the adoption of Convention No. 29 in 1930 (Wobbe et al., Citation2023). Legal expertise and colonial knowledge on so-called ‘native workers’ were mobilised by the ILO to define the category of forced labour in this period. In the interwar period, colonial knowledge had little basis in statistics but was imbued with what George Steinmetz has called ‘ethnographic capital’, i.e. a colonial knowledge ‘that claim(s) to represent the culture or character of a community defined variously as an ethnic group, race, nation, community, or people’ (Steinmetz, Citation2007, p. xiii). Following the practices in colonial empires that distinguished statistical enumeration, methods, and classification for the colonies and for the metropole (cf. Renard, Citation2019b, Citation2021), the observation of work in metropolitan and colonised territories at the ILO was separated, taking place in different arenas and on the basis of different kinds of expertise.

Convention No. 29 crystallised a certain consensus obtained during the sessions of the expert committees and at the ILC and was shaped by the imperial context of the time. According to the Convention, forced labour describes ‘all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily’ (ILO, Citation1930, Article 2(1)). The processes of categorising forced labour were historically embedded in gendered and colonial relations of conflict and power. Women’s activities in colonised territories were seen through a gendered lens and excluded from the field of reference of forced labour (Wobbe et al., Citation2023, p.184). Even if the perspective on forced labour inherited from the imperial context has been challenged on different occasions in the twentieth century (first during the Cold War and decolonisation and later in the 1990s; see Maul, Citation2007; Wobbe, Citation2020), Convention No. 29 and its definition of forced labour are still in force today.

In 1998, the ILO initiated a new approach and new means of action by connecting labour rights with universal human rights (see Wobbe & Renard, Citation2019). The Declaration of Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, adopted in 1998, established the elimination of forced or compulsory labour and the abolition of child labour as part of four fundamental principles and rights at work that are binding for all member states ‘even if they have not ratified the Conventions in question’ (ILO, Citation1998, p. 7). Within the framework of so-called ‘follow-up’ reports and projects to the Declaration, the ILO has been providing ‘technical assistance’ as well as financial resources to member states and its constituents (employers’ and workers’ organisations) in order to promote and implement the four principles globally (ILO, Citation1999a, p. 5). It was in this specific institutional setting that the Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour (SAP-FL), was created by the Governing Body of the ILO in 2001.

In contrast to the interwar period, the renewed interest in forced labour since 2000 was supported by investment in the production of statistics. The fact that the ILO turned to quantification as a further strategic tool in its campaign against forced labour, 70 years after the adoption of the Convention, reveals a need for clarification and plasticity.

Findings

The global estimates as an instrument of proof for political campaigns against forced labour

In the early 2000s, new instruments for producing knowledge and expertise on forced labour were introduced. Both internal and external impulses pushed for the production of estimates. Contrary to interwar discussions, the renewed discourse on forced labour was embedded in the broader international framework of human rights that had prevailed since the 1990s (Wobbe & Renard, Citation2019). Against the background of the expansion of globalised markets and international mobility of labour power – structured by economic deregulation and restrictive immigration policies – an increasing number of voices from civil society as well as governmental sources pointed to the negative socio-economic impacts of globalisation. The ILO embraced these interpretations and started to criticise the ‘underside of globalisation’ (Interview with former SAP-FL Director). In 2001, the Director-General’s Global Report ‘Stopping forced labour’ (ILO, Citation2001) highlighted both the persistent problems and the ‘changing face of forced labour’ (Plant & O’Reilly, Citation2003, p. 74).

We started drawing distinctions between traditional forms of forced labour and modern forms of forced labour. (Interview with former SAP-FL Director)

This political reorientation was accompanied by the allocation of resources towards the development of new ‘instruments of proof’. One objective of the SAP-FL was to assess the prevalence of forced labour in the world and to show that it was by no means a marginal phenomenon in order to mobilise governmental action (Wobbe, Citation2021). This impulse was based on the assumption that it is possible to research and depict forced labour as a social problem, if not exactly, then at least approximately, no matter how difficult data production might be (ILO, Citation2012a). Since 1930, the CEACR had regularly called governments out for their detrimental practices and their lack of implementation of conventions regarding forced labour. However, it was deemed easy for governments to deny the veracity of such accusations, since those were not based on any official numbers (Interview with former SAP-FL Director). Repeatedly, the CEACR pointed out the problem of missing data on forced labour in its reports, which was explained by ‘the fact that the exaction of forced labour is usually illicit, occurring in the underground economy and escaping national statistics as well as traditional household or labour force surveys’ (ILO, Citation2005a, p. iii.).

In this context, the Office aimed to establish that forced labour was a persistent and significant issue on a global scale, justifying political attention and action:

The number was less important. The idea was that it will attract people when you give a number. (Interview with independent consultant, former ILO statistician)

Moreover, the impetus to create a new political campaign based on new tools of knowledge is to be understood against the background of two related issues rooted in transnational social movements – human trafficking and child labour. Whereas forced labour and trafficking had been discussed and legally coded separately in the ILO and League of Nations in the interwar period (Wobbe et al., Citation2023), the ILO broadened its framework of reference in the 2000s in order to explicitly include human trafficking (ILO, Citation2001; Plant & O’Reilly, Citation2003). Human trafficking for sexual exploitation was a dominant object of international concern in the late 1990s that led to the adoption of the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime in 2000 and further Protocols (Limoncelli, Citation2017). The ILO supported the introduction of international legal instruments on the issue of trafficking, but at the same time contested the dominant focus on sexual exploitation (ILO, Citation1999b, p. 10). The ILO was concerned with the eclipsing effect the discussion around sex trafficking, distinct from labour abuses, might have on campaigns against forced labour (interview with former SAP-FL Director) (for sociological and historical accounts of transnational anti-trafficking movements, see Laite, Citation2017; Limoncelli, Citation2010). Consequently, data generation by national statistical offices concentrated to a great extent exclusively on sexual exploitation (ILO, Citation2006, p. 4). The SAP-FL research on trafficking was meant to ‘redress the balance in popular perceptions’ (Plant & O’Reilly, Citation2003, p. 79) and to highlight violations of labour rights. The ILO needed a statistical instrument of proof to demonstrate the relevance of the issue. For the purpose of countering the claims that exploitation in the sex sector constitutes the largest part of forced labour, ILO statisticians classified and presented the data in two distinct categories: forced labour exploitation and forced sexual exploitation. The distinction allowed the statisticians to compare the prevalence in both categories separately and to assess ‘Forced commercial sexual exploitation represents 11 per cent of all cases, and the overwhelming majority share – 64 per cent – […] for the purpose of economic exploitation’ (ILO, Citation2005b, p. 12). However, the separation of labour and sexual exploitation in the estimates for the aim of demonstration has a side effect, since it still conveys the idea that coercive practices in sex industries must be addressed separately from labour violations.

The second top issue of concern in the late 1990s was child labour, which, in contrast to human trafficking addressed by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, represented an ILO flagship area of action (along with the United Nations Children’s Fund – UNICEF). Drawing on the long history of in-house expertise in that area, the same ILO statisticians who conducted the first estimates on child labour on a global scale in 1996 (ILO, Citation1996) were also involved in the quantification of forced labour in the early 2000s. In the interplay with social movements who pushed for political measures, the statistics on child labour in international debates fostered the adoption of Convention No. 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labour in 1999.Footnote2 However, due to conceptual and methodological challenges, forced child labour was not surveyed in the 1990s (Anker et al., Citation2002, p. 17). The new forced labour surveys therefore had to include this issue. In 2013, the overlaps between both fields of expertise became even more manifest when the SAP-FL was merged with the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC). Today, those statisticians who work on the global estimates of forced labour are also responsible for the topic of child labour.

With the creation of the SAP-FL and its surveys, the ILO initiated a new political campaign with different, extended means (technical assistance and data generation), and reinforced its role as an international actor who – as the patron of Conventions No. 29 and 105 – holds the authority and expertise for the international community to address forced labour, including human trafficking. The ILO expanded its technical expertise and ensured the allocation of financial resources for further projects. Moreover, with the broadening of the framework of reference for forced labour to include social arrangements of work thereafter labelled as ‘modern’ forced labour, the interpretations of the category shifted.

From a legal to a statistical category

The ICLS first discussed the measurement of forced labour at its 17th conference in 2003 (ILO, Citation2003). The conference requested a global estimate of ‘forced labourers’ and to ‘define more easily observable criteria that might be used as direct or indirect indicators of the existence of a forced labour situation’ (ILO, Citation2003, pp. 26–27). Even though the legal definition needed to be adapted to a statistical logic, the criteria identified in the interwar period during the legal process of codification continue to persist to a considerable extent to this day.

Knowledge objects like forced labour that are not ‘physically given and directly observable’ (Mayntz, Citation2007, p. 7) represent a cognitive challenge for data producers (in the ILO’s own words: ‘Hard to see, harder to count’ (ILO, Citation2012a)). What series of cognitive and technical operations were necessary to translate a legal category into a framework of measurement? The construction of a framework of measurement for forced labour followed a path from law to statistics via qualitative studies. The steps included: 1) operationalising the criteria contained in legal instruments and reports for scientific observation, 2) conducting qualitative case studies in selected regions and sectors to obtain an up-to-date overview of the phenomenon, 3) finding a general definition and selecting indicators for further measurement and aggregation at the global level, 4) harmonising and standardising procedures for the replication of surveys in different regional and national contexts. At every stage, decisions were made with regard to equivalence and non-equivalence between individual cases.

First, after consulting legal expertise at the ILO, the definition of forced labour contained in Convention No. 29 was confirmed as a legal point of reference. Based on the Convention and observations of the CEACR, the ILO statisticians agreed to cover the two core elements of forced labour according to Convention No. 29 – involuntariness and menace of penalty. Even though a change in current manifestations of forced labour was depicted compared to the past, the criteria defined in 1930 were reaffirmed as still valid for addressing contemporary instances of forced labour today: ‘Over these almost 100 years, the phenomenon has changed but the criteria for assessing it has not changed.’ (Interview with independent consultant, former ILO statistician).

In order to develop statistical instruments (operational definition, questionnaire, indicators), the statisticians could rely on legal experts from the ILO Legal Department, who are understood by one interviewee as interpreters:

Every year there are committees of experts and they make reports. […] It’s not very clear, because it’s language, it’s not data […]. So, we have to interpret the language. And sometimes we use the experts themselves to interpret the language. The Legal Department of ILO helps us in Statistics to understand these legal statements. (Interview with independent consultant, former ILO statistician)

Second, from 2001 to 2004, the SAP-FL carried out qualitative studies on forced labour in member states that agreed to cooperate. This process of ‘exploratory research’ was called ‘rapid assessment’ (ILO, Citation2003, p. 28). The aim was to gain scientific knowledge beyond the legal reports (interview with ILO staff member). With this information on cases across regions, countries and sectors, the objective was to create a statistical measurement tool that would be appropriate for different national contexts. This step was central for the further development of survey methodologies (including questionnaires) as it allowed the selection of criteria to distinguish a case of forced labour from other social phenomena – thereby creating a convention of equivalence. However, the first estimates of forced labour published in 2005 were not yet based on survey data, but on the extrapolation of cases found in secondary sources like police reports, national criminal statistics, NGO reports and journalistic articles (ILO, Citation2005a; interview with independent consultant, former ILO statistician). The cases were selected by research assistants at the ILO on the basis of a preliminary list of indicators:

We gave them a protocol of what we mean by forced labour and what we mean by a case of forced labour which is quantitative. That means, they have to look at these reports and identify a case of forced labour. (Independent consultant, former ILO statistician)

Third, after this first experience, the SAP-FL ran pilot statistical surveys in cooperation with national statistical offices between 2008 and 2011 in order to test and refine the survey methodology on selected target groups. The resulting data was included in the second global estimate (20.9 million), supplementing the data generated from secondary sources (ILO, Citation2012b). Additionally, the knowledge gained formed the basis for preliminary survey guidelines to estimate forced labour of adults and children which included an operational definition of forced labour as well as a list of criteria to identify forced labour ‘to ensure consistency’ (ILO, Citation2014a, p. 6). The operational definition of forced labour for statistical purposes was based on the legal definition in Convention No. 29:

Forced labour of adults is defined, for the purpose of these guidelines, as work for which a person has not offered him or herself voluntarily (concept of ‘involuntariness’) and which is performed under the menace of any penalty (concept of ‘coercion’) applied by an employer or a third party to the worker. The coercion may take place during the worker’s recruitment process to force him or her to accept the job or, once the person is working, to force him/her to do tasks which were not part of what was agreed at the time of recruitment or to prevent him/her from leaving the job. (ILO, Citation2012a, p. 13)

Besides the first operational definition, the further production of global estimates was based on the selection of indicators. Indicators are used to order a vast amount of data on complex and highly abstract social phenomena (Merry, Citation2016, p. 10, 12; see also Davis et al., Citation2012). They are tools of simplification that enable comparison between individual cases or units of analysis. Indicators require conceptualisation: statisticians need to formulate clear assumptions with regard to the relation between the statistical construct and the reality observed. Indicators are thus structured approximations: when using indicators, statisticians assume that some qualitative phenomenon (like forced labour) cannot be seen directly and that only traces can be collected for the sake of measurement. The indicators of forced labour were derived from indicators of trafficking for labour and sexual exploitation which were produced with the Delphi method (for the history of this methodology see Dayé, Citation2020) in 2009 by the ILO in collaboration with the European Commission (ILO, Citation2009). They were based on ‘theoretical and practical experience’ of the SAP-FL (ILO, Citation2012c, p. 2) and included: Abuse of vulnerability; Deception; Restriction of movement; Isolation; Physical and sexual violence; Intimidation and threats; Retention of identity documents; Withholding of wages; Debt bondage; Abusive working and living conditions; Excessive overtime. On the basis of this list, national criteria of forced labour were deduced in workshops with selected stakeholders for the implementation in national surveys.

Fourth, in 2013, the 19th ICLS adopted a resolution recommending the establishment of a working group on statistics of forced labour with a mandate to develop a harmonised standard procedure for surveys taken at the national level that will deliver the data for the global estimates (ILO, Citation2013a). At this stage of international quantification, the comparability of data needed to be secured by ‘methodological decisions in the international arena including ICLS’ (Cussó, Citation2020, p. 4). The working group held six meetings between 2015 and 2016 on specific topics of forced labour of children, bonded labour, forced commercial sexual exploitation, and trafficking for forced labour (ILO, Citation2018c, p. 4). This took place in the framework of the ILO’s Data Initiative on Modern Slavery. The introduction of the term ‘modern slavery’ in 2015 broadened the scope of the estimates beyond the sole issue of forced labour and was described in our interviews as a political decision in order to comply with the terminology and framing of the Walk Free Foundation. The NGO was not only the main donor for the third edition of the estimates, but also collected and provided data on modern slavery in 2017 (ILO, Citation2017). Therefore, the Office had to bring diverse phenomena under the ‘chapeau of “modern slavery”’ in order to build a new framework of observation (ILO, Citation2015a, p. 3).Footnote3

The working group was commissioned with the development of draft guidelines concerning standardised operational definitions, questionnaire design and sampling methods (ILO, Citation2015b, p. 1). In the discussions between in-house and the external expertsFootnote4 invited to participate, both legal and statistical expertise were mobilised in order to reach a consensus regarding the statistical definition. During the first meeting, the primary issue of formulating an operational definition of forced labour was discussed against the background of Convention No. 29 and the related topics of human trafficking and child labour (ILO, Citation2015b). The discussion on the definition shows that the estimates were designed as a political instrument. Experts were asked ‘what would be the most useful approach (to definitions) in terms of generating the most effective policy responses?’ (ILO, Citation2015b, p. 2). The minutes of the discussion state that opinions were ‘divided’ on this aspect (ILO, Citation2015b, p. 2). ‘Close’ alignment with the legal category – focusing on the two criteria of involuntariness and menace of penalty – was desirable:

What we tried to convey in the working group […] was […] how to have […] the statistical definition that is closest to the ILO Convention, to the legal framework. And how to translate the legal framework in the statistics. Of course, this has also always been the idea but now, I mean, it’s more ‘loyal’ to the Convention. (Interview with ILO statistician)

A person is classified as being in forced labour if engaged during a specified reference period in any work that is both under the threat of menace of a penalty and involuntary. Both conditions must exist for this to be statistically regarded as forced labour. (ILO, Citation2018a, p. 2)

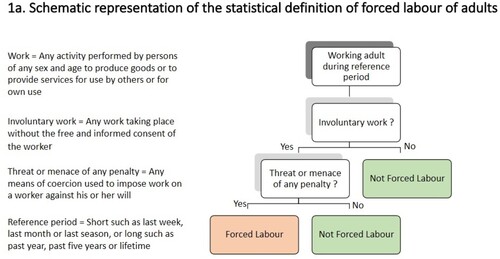

The schema shows the operative steps required in order to decide whether a case should be coded as forced labour or not. Based on the two criteria (involuntariness and menace of penalty) and the temporal dimension, survey questions were developed to assess the presence or absence of coercion with respect to recruitment, the work itself, and the possibility of leaving the employer (ILO, Citation2018c).

What the guidelines suggest – now, it’s how we have been trying to implement it – is really to try to identify ‘involuntary work’ and then we try usually to have these rescue questions. […] So, ‘Would you have accepted?’ or something like ‘If you knew the conditions were these’ or ‘Did you agree’ […] we usually would ask, still to capture involuntary work, and this idea of free, informed consent. Or we would ask, ‘Okay, did you agree to that?’, they say ‘Yes’, then we would not characterise ‘involuntary work’ generally. If they say ‘No’, then we would ask about coercion. (Interview with ILO statistician)

Figure 1. Schematic representation of forced labour proposed by the International Labour Office (FUNDAMENTALS) at the 20th ICLS in 2018. Copyright © International Labour Organization, Citation2018c, p. 8.

Forced begging and forced marriage: two examples of classification at the interface between statistical standards and legal instruments

In the definition of a measurement framework, the ILO statisticians had little room for manoeuvre, bound as they were between the legal instruments, on the one hand, and ICLS standards on the other:

The definitions are statistical in nature, rather than legal. While they work from legal definitions as a starting point, they are required to go beyond legal definitions to create a definition which is measurable. (ILO, Citation2018b, p. 16)

How did the definition of work influence the measurement framework of forced labour? Debates on what constitutes work have taken place at the ICLS since its first session in 1923. At the ICLS in 2013, the concept of work was broken down into ‘mutually exclusive’ sub-classifications for ‘separate measurement’ (ILO, Citation2013a, p. 49). The ICLS distinguished five different forms of work ‘on the basis of the intended destination of the production (for own final use; or for use by others, i.e. other economic units) and the nature of the transaction’ (ILO, Citation2013a, p. 3): Own use production work; Employment work; Volunteer work; Unpaid trainee work; Other work activities. This focus on production is also confirmed in our interviews:

And in ILO standard, which is international standard, work is any activity which generates production of goods and services. So, work is a very broad concept but it has a limit. (Interview with independent consultant, former ILO statistician)

Qualitative studies had identified forced begging as a problematic phenomenon in connection with child labour (ILO, Citation2013c, pp. 4–10). However, until then, begging had not been considered work according to ICLS standards. The SAP-FL experts argued that in the case of forced begging, a value for third parties was generated, and that it should therefore be considered and measured as an occurrence of forced labour. This interpretation is based on the understanding of the third party as an entity mediated via the market.

[W]e found out that many, especially children, are put in a forced situation of begging by some perpetrator. So, even though it’s not work for the definition of employment/unemployment in the national statistics, but it is an issue for forced labour. So, this is one exception and we put in the ILO guidelines that the concept of work may be extended to certain activities like begging, stealing, where they are not properly part of work and employment, but they are important for forced labour measurements. […] We have taken a flexible approach regarding the boundary of work and the boundary of employment, but by being flexible, we mean extending it, but in a clear way. (Interview with independent consultant, former ILO statistician)

A less flexible approach was applied to forced marriage, though. The estimates published in 2017 used the umbrella term ‘modern slavery’, including ‘forced labour’ on the one hand and ‘forced marriage’ on the other (ILO, Citation2017). Possible connections or overlaps between the two categories are not differentiated in the figures. Even though the official publication points out that ‘domestic servitude’ and ‘sexual exploitation’ can occur in forced marriage (ILO, Citation2017, p. 43), according to several interviews, the measurement tools seem not to consider such occurrences:

There could be for example an abusive marital relationship, which would be the case if it’s forced, in general. But to which extent is this to impose work on someone is a legal discussion that is beyond […] my statistical ability. I mean, I think, then we would have to consult other experts. (Interview with ILO statistician)

Moreover, another interviewee argues that since no contractual employment relationship can be observed in forced marriage, the measurement of labour in forced marriage is ‘very difficult’ (independent consultant, former ILO statistician). Thus, because they do not fit within the statistical framework of observation, various activities, especially household-related and unpaid activities performed by women, are left unaddressed. In the survey guidelines to estimate forced labour in 2012, it was moreover stated that ‘for practical reasons, the vocabulary used in these guidelines, particularly in the indicators and model questions, usually refers to an employer-employee relationship.’ (ILO, Citation2012a, p. 14). This example illustrates that unpaid sex and domestic work are not explicitly included as such in the definition and measurement framework of forced labour. Thus, gendered perceptions of work influence statistical conventions about work, and are latent in classification decisions of whether to recognise labour aspects in forced marriage or not. However, recently, the legal and social scientists Şişli and Limoncelli (Citation2019) have called for the recognition by the ILO of forced marriage of children as the worst form of child labour in the framework of Convention No. 182, therefore accounting for the interplay between (unpaid) work and (involuntary) marriage.

Our examples reveal that the quantitative measurement of forced labour is implicitly based on a ‘contractual’ employment relationship as a concept of work. This interpretation and codification of work shapes the lens through which forced labour is statistically observed. During the interviews, questions about concrete examples have exposed underlying selection processes for defining and thereby quantifying phenomena as forced labour. According to ILO statisticians, workers can only be coerced by another person; a formalised relation must exist that can be interpreted as equivalent to an employer-employee relationship; and the activities must be directed towards the generation of profits for economic markets. In the case of forced begging, the statisticians are able to construct a relation to the market – in the case of forced marriage, legal-normative boundaries prevent such a stretch. Our results show how implicit, but collectively shared gendered conceptions of work limit the field of vision of the ILO. These findings are in line with Cussó’s observations that ‘micro-decisions made by officials remain crucial’ (Cussó, Citation2016, p. 6), and that they are grounded in broader, social patterns of interpretation and knowledge about work and gender.

Discussion of the results

Our aim was to analyse the transformation of a legal category into a statistical category of forced labour oriented towards political action by reconstructing the stages of negotiation. We thereby contribute from a sociology of knowledge perspective to sociological debates about statistics produced by international organisations and emphasise particularities and connections between legal and statistical knowledge. We understand the production of the global estimates of forced labour as a historically and politically embedded process of international quantification which includes standardisation, cross-country cooperation and technical assistance as well as the publication of comparable data (Cussó, Citation2020, p. 2).

Reconstructing the genesis of the statistical category as a first step of our investigation, we found that the production of estimates was driven by internal impulses as well as by external actors in the field (other international organisations as well as NGOs and member states). In the context of civil society calling for action against human trafficking and child labour, the scope of forced labour was broadened in a political reorientation to integrate these issues. The ILO had to open up new fields of knowledge in the area of forced labour to facilitate political mobilisation. The process of quantification itself mobilised socio-political actors and prompted negotiations about the problematic framework of forced labour in the international arena. Here, ILO statisticians had a decisive role: they were not only guided by their professional ethos, but also integrated in the ILO’s ethical objective of social justice. This becomes apparent as the estimates were conceived in order to make a complex social phenomenon visible and comprehensible.

This is directly related to our second objective, namely, to demonstrate the specific role played by statistics in international organisations and their political action. We have argued that the production of global estimates transformed the legal construct of forced labour into a tangible category enabling political action through visibility. By creating figures and disseminating images able to attract public attention and raise awareness for labour rights violations among social actors, forced labour emerged as a contemporary social phenomenon and global public problem. The indicators constitute a solid set of conventions able to represent the fragile consensus obtained in 1930 on the categorisation of forced labour, and to transport this consensus into the twenty-first century. Moreover, the selection of indicators for the sake of statistical categorisation enabled the identification of labour situations and specific criteria that were also available for campaigns at the national and local level, e.g. conducted by trade unions.

With regard to concrete practices of statistical codification in international organisations, our results show the close reference to law and its normative imprints. The ILO’s standard-setting in international labour conventions creates the legal codification of labour and represents legal normative determinations, which in turn represent the framework for classification standards. This temporality is a distinctive feature of the category of forced labour. Both fields of knowledge, legal and statistical, are highly specialised areas in which the expertise of the actors is based on systematised practical knowledge. In the case of the estimates of forced labour, we have shown that the reference fields and conventions of equivalence differ and had to be negotiated by the statisticians. The legal definition was adapted to a statistical logic, with the criteria identified in the interwar period during the legal codification process being confirmed in the negotiations.

The statisticians involved in the production of the global estimates literally had to translate a legal convention (Convention No. 29) into statistical conventions of equivalence. During the process of operationalising the legal concept of forced labour into a statistical category, ILO statisticians substantiated the boundaries between forced labour and other kinds of labour, as well as between work and non-work. Our examples have revealed the gender dimension of the categorisation. The statistical decisions followed collectively shared patterns of interpretation about what constitutes work and what forced labour. However, not only conscious classification decisions lead to gender bias and invisibility. Unconscious exclusions and omissions (regarding marriage, for example) that are related to existing conventions of equivalence and patterns of interpretation may also create blind spots. ILO statisticians managed to handle these conventions in order to construct a framework of observation that is in line with both the legal category of forced labour and the ILO statistical standards of classification.

Did the statistical categorisation process induce a redefinition of forced labour? We observe both continuities and changes with regard to the interwar period. The interwar legal terminology and definition were reaffirmed by statistical expertise and engraved in the measurement tools by highlighting the two criteria of involuntariness and menace of penalty. Though these criteria remained stable over time, today’s ILO campaigns to abolish forced labour tackle different social realities, regions and working conditions than in earlier phases. Discussions of continuities and change appear in the debates of the ILO itself when describing forms of forced labour as ‘modern’ and discussing the validity or necessity of evaluating the legal instruments of the interwar period. Here we see the repercussions that the statistical instruments not only have on political campaigns, but also on legal categorisation. At the ILC 2012, during the general discussion on fundamental principles and rights at work, various participants referred to the recently published estimates to argue for a re-evaluation of the existing legal instruments to combat forced labour (e.g. the Worker Vice-Chairperson, see ILO, Citation2012d, p. 44). In 2014, the negotiations that took place during a Tripartite Meeting of Experts on Forced Labour and Trafficking for Labour Exploitation resulted in the adoption of a new legal instrument, which, once again, reaffirmed the legal definition from Convention No. 29 (ILO, Citation2014b) – at the legal level this time.

Conclusion & outlook: the heuristic value of a statistical construct

Our results have shown that the forced labour category has been negotiated in the interaction between legal and statistical expertise. The fragile social construct that originated in the imperial context of the interwar period obtained consistency with the standardisation of indicators and the classification decisions at the statistical level. This process brought to the fore a specific concept of forced labour which was formed and informed by various expertise and which ‘reflect[s] the social and cultural worlds of the actors and organizations that create them and the regimes of power within which they are formed’ (Merry, Citation2016, p. 4). The ‘seduction’ of the global estimates therefore lies in their ability to materialise a social construct and to transport it into other contexts of communication for political purposes.

But there is more: the magic of statistics lies not only in the number, as a tool for political mobilisation, but also in the category itself. On several occasions, our interview partners highlighted what we can call the heuristic value of the category. As part of a ‘technical assistance’ strategy, the ILO trains mediating actors (statisticians and officials in national offices, labour inspectors, but also civil society, trade unions, social workers, journalists), thereby bringing the category to the people, so to speak. This has an impact on the way people in contact with those mediating individuals (for example through their participation in a survey or their consultation with trade unions) come to see themselves or their relatives. Thus, the production of global estimates is by no way a goal in itself. After defining a framework of observation, the ILO was able to propose its visions to member states and stakeholders in a depoliticised way (for depoliticisation strategies in international organisations, see Louis & Maertens, Citation2021). It serves as a reference point for social actors to comprehend and address forced labour at the meso and micro levels. As Nicola Phillips puts it: ‘Evidently, “what is counted” as forced labour therefore shapes the resulting estimates of its incidence, and has very real consequences for human beings’ (Phillips, Citation2018, p. 50).

Here the logics of labour law and statistics have to make room for everyday categories of self-description (Hacking, Citation1996). This raises the question of how surveyed persons classify themselves. On the basis of which concept of work do they present themselves as working persons in surveys of labour conditions? Are the ILO’s instruments sensitive to this issue and therefore able to capture coercion-based situations if the person does not understand herself as a worker? This will be the task of further research to empirically observe the power of the statistical category at the micro level.

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of the collective project ‘Forced Labour as a Shifting Global Category: Classification, Comparison and Meanings of Work in the International Labour Organization (ILO), 1919-2017’ (FU Berlin, PIs: Marianne Braig and Theresa Wobbe) and we would like to thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for its generous funding (DFG Grant No. 413607635). The authors wish to thank Marianne Braig and Theresa Wobbe for their comments at various stages of the writing process, as well as Annick Lacroix, Baptiste Mollard and Laure Piguet for their critical perspective and thought-provoking suggestions. We are extremely grateful to our interviewees who took some of their precious time to answer our questions. Thanks also to Theresa Feißt, Mariana Pérez Garcia and Raffaela Pfaff for their valued advice and their work during the compilation of data and material, as well as to Kathrin Bennett for proofreading. Nicola Schalkowski wishes to thank the participants in the workshops of the network ‘Worlds of Related Coercions in Work’ for the interesting discussions (Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, 23–27 May 2022).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicola Schalkowski

Nicola Schalkowski is a sociologist and PhD candidate at Freie Universität Berlin. She currently works as a researcher and lecturer at the Institute for Latin American Studies in the DFG project ‘Forced Labour as a Shifting Global Category: Classification, Comparison and Meanings of Work in the International Labour Organization (ILO), 1919–2017’. Her research in the fields of sociology of knowledge, gender and feminist labour studies focuses on (un)paid domestic work and categorisations of work.

Léa Renard

Léa Renard is a postdoctoral researcher in sociology at Heidelberg University. Her research interests lie in the historical sociology of knowledge production, especially statistical categorization of work and migration.

Notes

1 For historical, anthropological and political economic accounts of forced or coerced labour, see LeBaron & Phillips, Citation2019; Phillips, Citation2013; Reckinger, Citation2018; Stanziani, Citation2020; Tiquet, Citation2019; Van Der Linden & Rodriguez Garcia, Citation2016.

2 According to Convention No. 182, Art. 3, the ‘worst forms of child labour’ comprise: ‘all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict’ (ILO, Citation1999c, Art. 3 (a)).

3 The ILO stated: ‘As the concepts of forced labour, human trafficking and slavery are closely related the ILO data initiative has been designed as a multi-stakeholder process involving all relevant organisations to agree on definitions for statistical purposes.’ (ILO, Citation2015a, p. 3).

4 Invited participants included actors from NGOs as well as governmental institutions with practical knowledge of conducting surveys or estimating forced labour and slavery at different levels (ILO, Citation2015b, p. 1).

References

- Antonelli, F. (2016.). Ambivalence of official statistics: Some theoretical-methodological notes. International Review of Sociology, 26(3), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2016.1244924

- Berrebi-Hoffman, I., Giraud, O., Renard, L., & Wobbe, T. (Eds.). (2019). Categories in Context. Gender and Work in France and Germany, 1900-Present. Berghahn Books.

- Boersma, S. (2020). Narrating society: Enacting ‘immigrant’ characters through negotiating, naturalization, and forgetting. Global Perspectives, 1(1), 12623. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2020.12623

- Bourdieu, P. (1987). The force of law: Towards a sociology of the juridical field. The Hastings Law Journal, 38(5), 805–853.

- Cussó, R. (2016). From statistics to international quantification: A dialogue with Alain Desrosières. In I. Bruno, F. Jany-Catrice, & B. Touchelay (Eds.), The Social Sciences of Quantification (pp. 55–65). Springer International Publishing.

- Cussó, R. (2020). Should ILO statistical activity be viewed as “international quantification”? Interwar production of, and cooperation on, labour data. Working papers D&S, 2020/4.

- Davis, K. E., Kingsbury, B., & Merry, S. E. (2012). Indicators as a technology of global governance. Law & Society Review, 46(1), 71–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2012.00473.x

- Dayé, C. (2020). Experts, social scientists, and techniques of prognosis in cold war america. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Desrosières, A. (1998). L’administrateur et le savant. Les métamorphoses du métier de statisticien. Courrier des statistiques, 87–88 (December 1998), 71–80. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bc6p06z99sp/f1.pdf

- Desrosières, A. (1999). The politics of large numbers. Harvard University Press.

- Desrosières, A. (2001). Entre réalisme métrologique et conventions d’équivalence: les ambiguïtés de la sociologie quantitative. Genèses, 43(2), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.3917/gen.043.0112

- Diaz-Bone, R., & Thévenot, L. (2010). Die Soziologie der Konventionen: Die Theorie der Konventionen als ein zentraler Bestandteil der neuen französischen Sozialwissenschaften. Trivium, 5, https://doi.org/10.4000/trivium.3557

- Hacking, I. (1996). The looping effects of human kinds. In D. Sperber, D. Premack, & A. J. Premack (Eds.), Causal cognition (pp. 351–383). Oxford University Press.

- Heintz, B. (2007). Zahlen, Wissen, Objektivität: Wissenschaftssoziologische Perspektiven. In A. Mennicken & H. Vollmer (Eds.), Zahlenwerk (pp. 65–85). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Kévonian, D. (2008). La légitimation par l’expertise: le Bureau international du travail et la statistique internationale. Les cahiers Irice, 2(2), 81–106.

- Köhler, B. (2008). Amtliche Statistik, Sichtbarkeit und die Herstellung von Verfügbarkeit. Berliner Journal für Soziologie, 18(1), 73–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11609-008-0005-8

- Kuckartz, U. (2012). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. Juventa.

- Laite, J. (2017). Between Scylla and Charybdis: Women’s labour migration and sex trafficking in the early twentieth century. International Review of Social History, 62(1), 37–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002085901600064X

- LeBaron, G., & Phillips, N. (2019). States and the political economy of unfree labour. New Political Economy, 24(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1420642

- Limoncelli, S. A. (2010). The politics of trafficking: The first international movement to combat the sexual exploitation of women. Stanford University Press.

- Limoncelli, S. A. (2017). The global development of contemporary anti-human trafficking advocacy. International Sociology, 32(6), 814–834. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580917729986

- Louis, M., & Maertens, L. (2021). Why international organizations hate politics. Depoliticizing the world. Routledge.

- Maul, D. R. (2007). The International Labour Organization and the struggle against forced labour from 1919 to the present. Labor History, 48(4), 477–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/00236560701580275

- Mayntz, R. (2007). Zählen – Messen – Entscheiden: Wissen im politischen Prozess [MPIfG Discussion Paper 17/12]. Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies. https://hdl.handle.net/11858/00-001M-0000-002D-9A21-5.

- Mennicken, A., & Espeland, W. N. (2019). What's New with Numbers? Sociological Approaches to the Study of Quantification. Annual Review of Sociology, 45(1), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041343

- Merry, S. E. (2016). The seductions of quantification: Measuring human rights, gender violence, and sex trafficking. University of Chicago Press.

- Petzke, M. (2021). Die Moral des Vermessens: Bewertungsüberschüsse in der statistischen Beobachtung von Integrationsfortschritten der Migrantenbevölkerung in Deutschland. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 73(S1), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-021-00749-9

- Phillips, N. (2013). Unfree labour and adverse incorporation in the global economy: Comparative perspectives on Brazil and India. Economy and Society, 42(2), 171–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2012.718630

- Phillips, N. (2018). The Politics of numbers: Beyond methodological challenges in research on forced labour. In G. LeBaron (Ed.), Researching forced labour in the global economy: Methodological challenges and advances (pp. 44–59). Oxford University Press.

- Piguet, L. (2018). La justice sociale par les statistiques? Le cas des accidents d’attelage des wagons de chemins de fer (1923-1931). Le Mouvement Social, 263(2), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.3917/lms.263.0031

- Piguet, L. (2022). Grèves et grévistes dans les statistiques internationales. L’art compilatoire du Bureau international du travail (1920-1939). In F. Cardoni, A. Conchon, M. Margairaz, & B. Touchelay (Eds.), Chiffres privés, chiffres publics xviie-xxie siècle: Entre hybridations et conflits (pp. 145–158). Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Porter, T. M. (1995). Trust in numbers. The pursuit of objectivity in science and public life. Princeton University Press.

- Reckinger, G. (2018). Bittere Orangen: Ein neues Gesicht der Sklaverei in Europa. Peter Hammer Verlag.

- Renard, L. (2019a). The grey zones between work and non-work: Statistical and social placing of ‘family workers’ in Germany (1880–2010). In I. Berrebi-Hoffmann, O. Giraud, L. Renard, & T. Wobbe (Eds.), Categories in context. Gender and work in France and Germany, 1900-present (pp. 40–59). Berghahn Books.

- Renard, L. (2019b). Socio-histoire de l’observation statistique de l’altérité. Principes de classification coloniale, nationale et migratoire en France et en Allemagne (1880-2010) [Doctoral dissertation]. Université Grenoble Alpes & Universität Potsdam.

- Renard, L. (2021). Vergleichsverbot? Bevölkerungsstatistiken und die Frage der Vergleichbarkeit in den deutschen Kolonien (1885-1914). Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 73(Suppl 1), 169–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-021-00745-z

- Şişli, Z., & Limoncelli, S. A. (2019). Child brides or child labor in a worst form? Labor and Society, 22(2), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/wusa.12407

- Stanziani, A. (2020). Les métamorphoses du travail contraint. Une histoire globale XVIIIe-XIXe siècles. Presses de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques.

- Steinmetz, G. (2007). The devil’s handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa. University of Chicago Press.

- Tiquet, R. (2019). Travail forcé et mobilisation de la main-d’œuvre au Sénégal: années 1920-1960. Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Van Der Linden, M., & Rodriguez Garcia, M. (2016). On coerced labour: Work and compulsion after chattel slavery. Brill.

- Vanderstraeten, R. (2006). Soziale Beobachtungsraster: Eine wissenssoziologische Analyse statistischer Klassifikationsschemata. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 35(3), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2006-0302

- Wobbe, T. (2012). Making up people: Berufsstatistische Klassifikation, geschlechtliche Kategorisierung und wirtschaftliche Inklusion um 1900 in Deutschland. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 41(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2012-0105

- Wobbe, T. (2020). Hard to see, harder to count’ Klassifizierung und Vergleichbarkeit der globalen Kategorie ‘Zwangsarbeit’ in der International Labour Organization während der 1920er und 2000er Jahre. In H. Bennani, M. Bühler, S. Cramer, & A. Glauser (Eds.), Global beobachten und vergleichen. Soziologische Analysen zur Weltgesellschaft (pp. 141–242). Campus.

- Wobbe, T. (2021). Die Differenz Haushalt vs. Markt als latentes Beobachtungsschema. Vergleichsverfahren der inter/nationalen Statistik (1882–1990). Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 73(S1), 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-021-00746-y

- Wobbe, T., & Renard, L. (2017). The category of ‘family workers’ in International Labour Organization statistics (1930s–1980s): A contribution to the study of globalized gendered boundaries between household and market. Journal of Global History, 12(3), 340–360. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022817000183

- Wobbe, T., & Renard, L. (2019). Der Deutungswandel der Zwangsarbeit in der International Labour Organization (ILO): Eine vergleichstheoretische Perspektive. In N. Burzan (Ed.), Komplexe Dynamiken globaler und lokaler Entwicklungen. Verhandlungen des 39. Kongresses der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie in Göttingen 2018. https://publikationen.soziologie.de/index.php/kongressband_2018/article/view/1132.

- Wobbe, T., Renard, L., & Müller, K. (2017). Nationale und globale Deutungsmodelle des Geschlechts im arbeitsstatistischen sowie arbeitsrechtlichen Klassifikationssystem: Ein vergleichstheoretischer Beitrag (1882-1992). Soziale Welt, 68(1), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.5771/0038-6073-2017-1-63

- Wobbe, T., Renard, L., Schalkowski, N., & Braig, M. (2023). Deutungsmodelle von Arbeit im Spiegel kolonialer und geschlechtlicher Dimensionen. Kategorisierungsprozesse von “Zwangsarbeit” während der Zwischenkriegszeit. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 52(2), 172–190. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2023-2014

- Zimmermann, B. (2001). La constitution du chômage en Allemagne: entre professions et territoires. Maison des sciences de l’homme.

- Zimmermann, B. (2015). Socio-histoire and public-policy rescaling issues: Learning from unemployment policies in Germany (1870-1927). In S. Börner & M. Eigmüller (Eds.), European integration, processes of change and the national experience (pp. 121–146). Palgrave Macmillan.

Sources

- Anker, R., Chernyshev, I., Egger, P., Mehran, F., & Ritter, J. (2002). Measuring decent work with statistical indicators: Working Paper No. 2 (wcms_079089). International Labour Organization.

- ILO. (1930). Convention concerning forced or compulsory labour (No. 29), adopted in Geneva at the 14th ILC Session, 28 June 1930 (entered into force 1 May 1932).

- ILO. (1985). Convention concerning labour statistics (No. 160), adopted in Geneva at the 71st ILC session, 25 June 1985 (entered into force 24 April 1988).

- ILO. (1996). Child labour today: Facts and figures. World of work, 16 (June/July), 12–17.

- ILO. (1998). Declaration of fundamental principles and rights at work (wcms_716594).

- ILO. (1999a). Report of the director-general: Decent work. Eighty-seventh session of the International Labour Conference. https://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc87/rep-i.htm.

- ILO. (1999b). Note by the International Labour Organization on the additional legal instrument against trafficking in women and children. Ad Hoc committee on the elaboration of a convention against transnational organized crime, fourth session Vienna, 28 June-9 July 1999. (Al AC.254/CRP .14).

- ILO. (1999c). Convention concerning the prohibition and immediate action for the elimination of the worst forms of child labour (No. 182), adopted in Geneva at the 87th ILC session, 17 June 1999 (entered into force 19 November 2000).

- ILO. (1999d). Migrant workers. Report of the committee of experts on the application of conventions and recommendations (REP31B9.E99).

- ILO. (2001). Report of the director-general: Stopping forced labour, global report under the follow-up to the ILO declaration on fundamental principles and rights at work (wcms_publ_9221119483).

- ILO. (2003). Report of the conference. Seventeenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS/17/2003/4).

- ILO. (2005a). ILO minimum estimate of forced labour in the world (wcms_081913).

- ILO. (2005b). Report of the director-general: A global alliance against forced labour, global report under the follow-up to the ILO declaration on fundamental principles and rights at work 2005, report I(B). Ninety-third Session of the International Labour Conference.

- ILO. (2006). Technical consultation on forced labour indicators, data collection and national estimates: Summary report (wcms_081981).

- ILO. (2009). Operational indicators of trafficking in human beings (wcms_105023).

- ILO. (2012a). Hard to see, harder to count: Survey guidelines to estimate forced labour of adults and children (wcms_182096).

- ILO. (2012b). ILO global estimate of forced labour: Results and methodology (wcms_182004). International Labour Organization.

- ILO. (2012c). ILO indicators of forced labour (wcms_203832).

- ILO. (2012d). Provisional record. One hundred first Session of the International Labour Conference (ILC101-PR15-2012-06-0189-1-En.docx).

- ILO. (2013a). Report of the conference: Report III. Nineteenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS/19/2013/3).

- ILO. (2013b). Tripartite meeting of experts on forced labour and trafficking for labour exploitation. Conclusions adopted by the meeting (TMELE/2013/6).

- ILO. (2013c). Forced labour and human trafficking: Room document 3. Nineteenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (wcms_222037).

- ILO. (2014a). Profits and poverty: The economics of forced labour (wcms_24339).

- ILO. (2014b). Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention, 1930, adopted in Geneva at the 103d ILC session, 11 June 2014 (entered into force 9 November 2016).

- ILO. (2015a). ILO data initiative on modern slavery. Better data for better policies. Special action programme to combat forced labour. Fundamental principles and rights at work branch.

- ILO. (2015b). ILO expert workshop on measuring modern slavery Geneva, 27-28 April 2015.

- ILO. (2017). Global estimates of modern slavery: Forced labour and forced marriage (wcms_575479). International Labour Organization and Walk Free Foundation.

- ILO. (2018a). Guidelines concerning the measurement of forced labour. Twentieth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS/20/2018/Guidelines).

- ILO. (2018b). Report of the conference: Twentieth International Conference of Labour Statisticians, Report III (ICLS/20/2018/3).

- ILO. (2018c). Room document 14 measurement of forced labour. Twentieth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS/20/2018/Room document 14). ILO FUNDAMENTALS.

- Plant, R., & O’Reilly, C. (2003). Perspectives: The ILO special action programme to combat forced labour. International Labour Review, 142(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2003.tb00253.x