ABSTRACT

It is often claimed that Nordic welfare states are characterized by universalism – however, such claims ignore the persistent duality of social service provision in these states between the central state and municipalities, the lowest political-administrative level. This paper investigates the Swedish welfare state, by looking at the rescaling of welfare services from national to municipal level and its (negative) effects on both municipalities and service users. The aim is to expand the understanding of austerity measures and their local impact by analyzing the transformation processes of responsibilities between national and municipal institutions in the Swedish welfare system based on rescaling and policy layering. Two cases of rescaling are analyzed through public reports and statistics: transfer from national sickness insurance to municipal social assistance, and personal assistance for people with disabilities. The two cases illustrate the vulnerability of Swedish municipalities, in cases of national austerity measures, as the municipalities have the ‘ultimate responsibility' for marginalized groups such as unemployed people and people with disabilities. Given the differences between municipalities, in terms of factors such as size and economic situation, and the extensive discretion of municipalities in determining services, rescaling to municipalities increases inequalities between people living in Sweden based on municipal residence.

Introduction

It is often claimed that Nordic welfare states are characterized by universalism – however, such claims ignore the persistent duality of social service provision in these states. Commonly, the idea of universalism relies on Esping-Andersen’s (Citation1990) work on welfare regimes and the division of labour between state, market, and family, as well as on the work of subsequent scholars following this stream of research (e.g. Powell, Yörük, and Bargu Citation2019). Although this conceptualization is powerful, in its combination of simplicity and analytic precision, it has a major flaw; namely, it does not consider the vertical division of responsibilities between state actors, i.e. what political-administrative levels are responsible for specific forms of support. Esping-Andersen claimed not only that Nordic welfare states rely on public support, but that they offered universal support, i.e. one form of support available for all citizens. This universal support is to be secured by strong national institutions including accessible protection for low-income workers. While it is true that Nordic countries are characterized by extensive national institutions, it is also true that they have uniquely strong autonomy at the municipal level, i.e. the lowest political-administrative level. Nordic municipalities are not least responsible for providing social services, including social assistance (i.e. basic financial security) to people with little or no labour market attachment, and caring for marginalized groups such as people with disabilities. These responsibilities date back several centuries and have shown themselves to be resistant to attempts to nationalize them (Brauer Citation2022; Ladner et al. Citation2019).

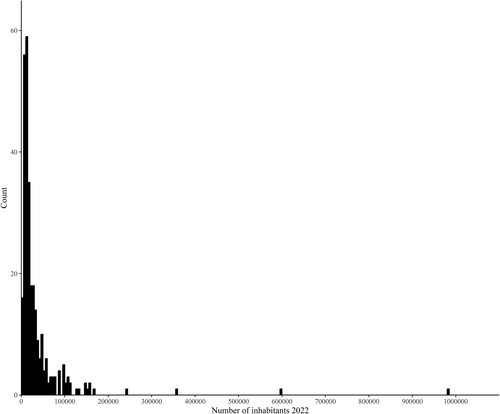

This paper investigates Sweden, a country that shares its Nordic neighbours’ combination of extensive national institutions and strong municipal autonomy. Despite its sticky reputation of being a universal welfare state (cf. Cox Citation2004), the division of responsibilities between national and municipal levels is a recurrent topic of discussion among policy makers in Sweden. This concerns not least the responsibility for social policies such as financial support and care. It is tempting for both central and local governments to pursue cost-shifting, i.e. for local authorities to push costs onto the central government and vice versa (Bonoli and Trein Citation2016). However, the possibility for cost-shifting is not equally distributed, as municipalities bear the ultimate responsibility (Sw. yttersta ansvaret) for people with social problems in Sweden, which means that the municipalities must assist people who are (or used to be) entitled to support from national authorities but are now denied such support (SFS Citation2001:453, 2 c. 1 §). This legal construction means that austerity measures on the national level, such as increased restrictions on sickness insurance, administered by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency and funded by the national budget, increase the pressure on municipalities to provide for people affected by the austerity measures. This paper reviews two cases where two cost-shifting processes occurred, from national to municipal level, and how it affected both municipalities and the people receiving support. The first case concerns the relation between sickness insurance (publicly funded economic provision for sick-listed people with little or no work ability administrated and funded nationally), and social assistance (means-tested and residual economic provision administrated and funded by the municipalities). The second case concerns personal assistance for people with significant and long-term functional disabilities; a service administered and funded both on national and municipal levels. These cases are significant for understanding quiet austerity in the Nordic context, as they rely on rescaling from national to local authorities which decreases the emphasis on universalism in the Nordic welfare states and opens up greater sub-national differences – differences that must be seen in the light of the uneven geographies of municipalities (cf. Brauer Citation2022). Apart from having strong local autonomy, Swedish municipalities are characterized by size differences, in terms of both population and the scale of their economic and social situations. A total of 19 out of 290 municipalities have 100,000 thousand inhabitants or more. Given economies of scale, these municipalities are likely to have lower costs per capita for the administration of social services than the many small municipalities, not least the 202 municipalities (70 per cent) with less than 30 000 inhabitants. Both larger and smaller municipalities have tried to lower costs by inter-municipal collaboration. However, such collaborations are unusual in the welfare sector (Erlingsson and Folkesson Citation2022). There are attempts at the national level to counteract the unequal resources of municipalities through equalizing systems (Högström and Lidén Citation2023), however, these do not fully redress the inequalities that exist between municipalities (Swedish National Audit Office Citation2019). Taken together, national austerity measures within financial support and care pose challenges for Swedish municipalities – challenges whose impact differs given the differences in the size and the economic and social situations of municipalities. The aim is to expand the understanding of austerity measures and their local impact by analyzing the transformation processes of responsibilities between national and municipal institutions in the Swedish welfare system based on rescaling and policy layering. The two empirical cases are investigated by analyzing reports, public data, and previous research.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. This introduction is followed by the theoretical frame, which combines geography of scale and especially the concept of rescaling (Jessop, Brenner, and Jones Citation2008) with historical institutional theory about policy layering (Mahoney and Thelen Citation2010). Thereafter, the analytical approach is introduced along with the context and selected cases, presentation of methods and data, after which the findings are presented. This is followed by a concluding discussion.

Theoretical frame: state rescaling and policy layering

The paper merges two theoretical strands: political-geographical contributions on state rescaling (Jessop, Brenner, and Jones Citation2008) and historical institutional literature concerned with policy layering (Mahoney and Thelen Citation2010). The former refers to the vertical differentiation of territories into tiers of political-administrative bodies, for instance in the Swedish case, into municipality, region, state, and European Union. Through tradition and previous policies, political issues are assigned to one or several levels. Rescaling occurs when existing divisions are challenged and reassigned. In a European context, the rescaling of trade policy from the nation to the European Union is an obvious example. Rescaling does not only concern the administrative division of tasks; it also has the potential to shift problem definitions, as political-administrative units are given new roles. A well-known example is Brenner’s (Citation2004a) analysis of the rearticulation of urban governance during the post-Fordist period. As responsibilities were rescaled from state to urban areas, the latter experienced pressure to enhance economic competition through workfare measures, place-making campaigns, and local industrial policies. There are also reasons to consider Jessop’s notion of the Schumpeterian Workfare Postnational Regime, i.e. a ‘shift from the primacy of the national scale to a postnational framework in which no scale is predominant’ (Citation1999, 355). From this perspective, rescaling can be understood against the background of more fundamental lines of development since the oil crises during the 1970s and onwards, including commodification and marketization – processes of re-imagination where public services become market goods and citizens become customers (see also Brenner [Citation2004b] and Peck [Citation2002]). These complex sets of processes, described and disentangled by Jessop, Brenner, and Peck, situate the rescaling processes, analyzed in this paper, in the gradient weakening of the national welfare state.

It must be stressed that rescaling is presented here as an outcome that could come from different processes – processes that can be grounded in either consensus or conflict. The use of the term ‘assigned' in the previous paragraph might give the impression that rescaling occurs through consensus and structured planning between (collective) agents that agree on the need to rescale. While such situations might occur, there are good reasons to believe that conflicts often precede and follow rescaling, as changes of the status quo are rarely pareto-optimal for involved actors. Furthermore, as will be demonstrated in this paper, rescaling can be the subject of recurring renegotiation, which speaks in favour of also viewing rescaling from a conflict-oriented perspective.

Layering is one of four types of mechanisms that explain a gradual change of formal institutions suggested by Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2010), see for a description of all four mechanisms. Layering occurs when new rules are introduced, rules that modify how previous policies play out. Hence, despite appearing to be intact, existing institutions will behave differently. Mahoney and Thelen argue that layering takes place when policy makers intend to change institutions but lack the power to make more fundamental configurations. Instead, they ‘work within the existing system by adding new rules on top of or alongside old ones' (Mahoney and Thelen Citation2010, 17). As will be discussed more thoroughly in the analysis, this conception of policy change is fruitful for understanding divisions between Swedish national and municipal authorities, as the institutional core of the studied case has remained intact. Still, by imposing additional rules, the amendments have severely impacted the marginalized groups that were affected by them.

Table 1. Types of Gradual Change (Mahoney and Thelen Citation2010, 16).

The theorization of institutional change can be viewed in the light of a reorientation within historical institutionalism, where several early works relied on the argument of path dependency and increasing return. The argument is that institutions tend to be reproduced, as it is costly to change institutional paths. Hence institutions tend to resist change (Mahoney Citation2000; Pierson Citation2000). While this argument remains both relevant and acknowledged (e.g. Pierson Citation2015), it has tended to overshadow the fact that the institutions do change – if often gradually (Streeck and Thelen Citation2005). But as the description of layering shows, the basic claim of path dependency, that it is costly to change path, is relevant to understanding institutional change. It is the persistency of current institutions, rather than more encompassing institutional change, that generates the need to pursue layering. Thus, the mechanism of layering extends the argument of path dependency by showing that policy makers must adapt to existing paths to achieve institutional change.

Analytical approach

This section describes the analytical approach and introduces the studied context, that is, the Swedish welfare state and the division of responsibilities between the central government and municipalities.

The multi-level governance of Swedish social policy

Sweden has three political-administrative levels, state, region, and municipality. This paper focuses on the first and third levels. The second level, the 21 regions (until 2019 labelled counties), is responsible for health services and regional development. Although the regions are not the subject of the paper, it is worth mentioning that they are of historical importance in the second case, as responsibilities were rescaled from the region/counties to the municipalities during the end of the twentieth century. Returning to the levels of study, we will begin with the municipalities.

Sweden is divided into 290 municipalities that, comparatively speaking, possess high fiscal autonomy and are responsible for numerous services ranging from infrastructure, such as water and sewage, to social services (Ladner et al. Citation2019). Swedish municipalities also have a monopoly on physical planning within their borders, which gives them extensive discretion in questions such as urban policies (Lidström and Hertting Citation2022). Their responsibility for social services, which is examined in this paper, is governed by the Social Services Act (SFS Citation2001, 453), a framework law that gives municipalities discretion in providing services to ensure that inhabitants have decent living conditions. A feature of the Social Services Act that is central to this paper is the ultimate responsibility of the municipality (Sw. kommunens yttersta ansvar). This responsibility stated in the first paragraph of the second chapter, stipulates that if marginalized people do not have decent living conditions, the municipality is obligated to provide such conditions.

The Social Services Act regulates most social services, the exception being some services for people with severe disabilities that are delivered through the Act Concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments (SFS Citation1993, 387). This was introduced in 1993 and represented a radical departure from the framework construction of the Social Services Act, as the new law was rights-based. As such, the law leaves less room for authorities to refuse services because of insufficient resources or on similar grounds (Hollander Citation1995). The law stipulates ten clearly defined services and three target groups:

1. Persons with intellectual disabilities and people with autism or conditions similar to autism.

2. Persons with significant and permanent intellectual functional disabilities following brain damage as an adult.

3. Persons, who as a result of other serious and permanent functional disabilities, which are clearly not the result of normal ageing, have considerable difficulties in everyday life and great need of support or service

(SFS Citation1993, 387; 1 §, translation by County of Stockholm Citation2014)

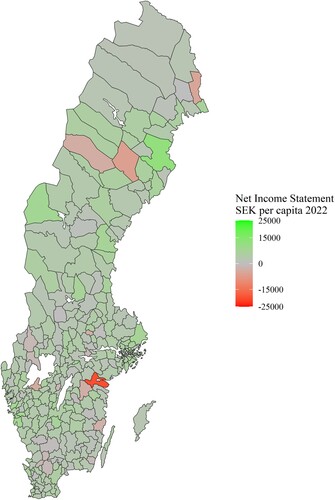

It is important to highlight that Swedish municipalities vary in area, population size, and people density, with the smallest one having approximately 2400 inhabitants and Stockholm, Sweden’s capital and largest municipality, having just below a million (in 2022, the median was 16 282 inhabitants and the mean 36 281 inhabitants – see ). Going beyond the size of the area and population, there are other important differences between municipalities. This includes economic activity, where some municipalities struggle with the effects of deindustrialization while others thrive through service production or tourism. These differences, in turn, relate to geographical factors, including distances to metropolitan areas but also natural resources. Together, these differences mean that while all municipalities face challenges in making ends meet, these challenges vary widely (Brauer Citation2021). There are government attempts to reduce intra-municipal differences in costs for social measures. Regarding questions about unemployment and social assistance, a national economic equalization system redistributes financial resources from richer to poorer municipalities, with the government supplementing the municipal contributions (SFS Citation2004, 881). Similarly, there is an equalization system to even out the costs of services that are delivered based on the Act Concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments (SFS Citation2008, 776). While these systems ease some of the pressure of municipalities experiencing economic stagnation, they do not fully reduce municipal inequalities which is obvious when looking at which plots the Net Income Statement, i.e. the balance between the financial revenues and financial expenditures of all municipalities, for 2022 (see also Swedish National Audit Office [Citation2019] for a discussion concerning the current equalization system).

Turning to the responsibilities of the central state, regarding the first of the two cases examined in the paper, the state is responsible for sickness insurance (for temporary illness) and disability pensions (for permanent illness) both of which are administered by the Social Insurance Agency. Because sickness insurance is insurance-based, people need to have prior labour market attachment in Sweden to qualify for it. People without labour market attachment can be approved for disability pensions, but because the benefits level is based on prior income, it is often inadequate to enable recipients to be self-sufficient, in which case they must rely on supplementary social assistance from the municipality. Continuing to the second case, the central state administers and funds personal assistance for people who receive more than 20 h of assistance per week. Assistance for people receiving 20 or fewer hours is administered by the municipalities (SOU Citation2023, 9). Hence, the same programme, personal assistance, is governed on two political-administrative levels. This will be discussed more extensively in the next part of the paper.

Methods and data

Data for the analysis has been collected from reports and documents published by the government and authorities, public data published by Statistics Sweden and the National Board of Health and Welfare, as well as previous research. Data has been chosen to represent different perspectives, including the government, through propositions, the involved agencies, municipalities, and independent revisions made by the Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. The importance of including different perspectives lies in the risk of uncritically accepting a single narrative emphasized by a single actor which would be problematic in terms of validity. This argument also motivates the use of public data and previous research. Again, the ambition has been to view the studied cases from different perspectives. Data sources have been combined and analyzed based on the theoretical framework. The cases were selected due to their ability to exemplify recent attempts to rescale the Swedish welfare state. This means of selection can best be explained as purposive sampling, as it was guided by the aim of choosing information-rich cases (Patton Citation2002).

Findings

Case 1. National sickness insurance and municipal social assistance

The first case concerns the consequences of a series of austerity measures in the national sickness insurance that began in 2008 when the conservative-liberal Alliance government was in power. The government made the level of financial compensation less generous. They also added more restrictions related to assessing work ability. After 180 days, the Social Insurance Agency was to assess whether the applicant could become self-sufficient through employment elsewhere in the ordinary labour market. If so, the applicant was to be denied continued sickness insurance. This change was grounded in a clearer distinction between being sick and being unable to work. The Alliance government emphasized the importance of focusing on the latter, arguing that the main issue was not whether people were sick but whether they could work. Lastly, the government also added a rule that has been referred to as a ‘closing bracket', which required that after 914 days of approved sickness insurance, recipients were to be de-insured and had to enter a work-introduction programme administered by the Public Employment Services, which is a national authority (Proposition Citation2007/08:136).

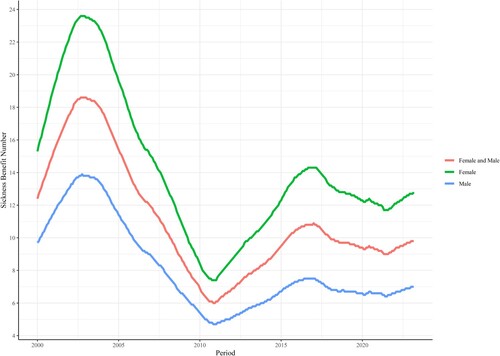

The introduction of the closing bracket was heavily criticized by oppositional parties, media, and the public. In 2016, it was removed by a government led by the Social-Democratic party and the Green party (which came into office in 2014). The preceding year, the same government had also made the benefits levels more generous again (Proposition 2015/16:1 Citationn.d.). While it might seem that the new government made sickness insurance more generous, they also signalled that the use of sickness insurance had to be reduced. This intention was put into practice through the enhanced governmental direction of the Social Insurance Agency, with a shift in focus from trust to accountability and reduction of sickness insurance spending. In comparison with previous attempts to reduce such spending, the government set a much more distinct goal: to reduce the sickness benefit numberFootnote1 (Sw. sjukpenningtalet) to 9.0 per cent.Footnote2 In two reports, the Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate (Citation2018a; Citation2018b) showed how this shift in focus influenced the agency, both among managers and social insurance officers. The latter began emphasizing whether applicants qualified for insurance and downplaying measures to coordinate rehabilitation. Or, to cite one of the reports: ‘Today, the work as an officer is more about administering than coordinating sickness insurance' (Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate Citation2018a, 16). Many physicians expressed critique against the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, not least in terms of poor rule of law and the Social Insurance Officer’s lack of competence as well as lack of trust in the assessments made by physicians (Swedish Social Insurance Agency Citation2015). In sum, both the liberal-conservative government and the Social-Democratic/Green-party government introduced new sets of rules that changed the provision of sickness insurance. The reforms of 2007 are especially conspicuous when looking at the sickness benefit numbers presented in .

How did these austerity measures affect the municipalities and how did the municipalities respond? While most applicants for sickness benefits who were affected by the austerity measures were eventually able to return to sickness insurance, a non-negligible proportion had to apply for social assistance. In a study of people who were denied sickness insurance after 914 days during the third quarter of 2010, 8.6 per cent received social assistance for at least six months (Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate Citation2013). Other reports estimate similar numbers, i.e. around 10 per cent (Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions Citation2011; Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate Citation2022). Still, there is a reported lack of research that looks at these figures more systematically on a national level (Vingård Citation2015). The increased pressure on municipalities triggered responses, both by municipalities directly and by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, an organization that represents municipalities.Footnote3 Because municipal activation programmes target work-capable persons, reports pointed to difficulties among municipalities in supporting sick-listed people who were denied sickness insurance (as they lacked the capability to work). The municipalities argued that the sick-listed people excluded from sickness insurance deviated from the target population for activation programmes, because sick-listed people require more extensive and inter-professional support that includes health services, which is a regional responsibility (Municipality of Stockholm Citation2020a; Citation2020b; Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions Citation2011).

Besides affecting the municipalities, the austerity measures also generated pressure on the people who were denied sick insurance. It is important to note the differences between sickness insurance and social assistance in the Swedish context. Benefit levels for social assistance are not based on prior earnings, as is the case for sickness insurance. Hence, sick-listed people with recent labour market attachment are likely to experience severe income loss if transferred from sickness insurance to social assistance. Apart from being disadvantageous in terms of compensation levels, social assistance is less favourable than sickness insurance due to the municipalities’ discretion in assessing support needs and making support conditional. Social assistance can be conditioned upon selling assets, including a house or condominium as well as a car (SOSFS Citation2013, 1). Social assistance is intended for short-term dependency, which is explained by the historical background of universalism. After World War II, social assistance recipiency rates decreased because employment was high and there was ready access to unemployment and sickness benefits (Korpi Citation1975). From this perspective, it made sense to give municipalities the freedom to place high demands on social assistance recipients to become self-sufficient (as access to employment opportunities and social insurance were good). But in the twenty-first century, and for people who have been sick-listed for at least three years, as was the case for people who were excluded from sickness insurance, the municipal requirements are much more problematic. Recipients are potentially forced into greater insecurity as well as poverty traps, for instance by having to rent an apartment and sell their car, making them less mobile. The extent to which such conditionality was used for the group of people who were denied sickness insurance is unknown in quantitative terms. Still, there are examples of how the shift from sickness insurance to social assistance affected individuals. Niklas Altermark (Citation2020) cites a statement from a social media campaign: ‘My first application for social assistance was rejected based on the claim that I had additional assets such as car, land, house, etc., that I had to dispose of before I could be considered eligible for social assistance' (Altermark Citation2020, 113f. Translated by the author of this paper). The quotation does not describe an isolated incident, but rather an institutionalized gap between the conditions for receiving sickness insurance and receiving social assistance, again, given the discretion of municipalities to require social assistance recipients to dispose of assets in accordance with the first paragraph of the fourth chapter in the Social Service Act (SFS Citation2001, 453).

How can we understand the case of sickness insurance based on the theoretical frame of this paper? In a foreword to a report published by the Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate, the general director interprets the consequences in a way that is impressively similar to the definition of layering: ‘ … they have affected how Social Assistance Officers apply the regulatory framework of the sickness insurance – despite the fact that the regulatory framework has not undergone any significant changes during the period' (Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate Citation2018a, 9, translated by the author of this paper). Both the liberal-conservative Alliance government and the Social Democratic/Green government added new regulatory mechanisms ‘on top' of the existing institutions. The responsibility for sick-listed people was partially rescaled from the central government to municipalities when it came to both financial support and rehabilitation. Regarding financial support, the rescaling from sickness insurance to social assistance brought a greater risk of poverty traps, because of the possibility for municipalities to make social assistance conditional. Looking at rehabilitation, we have seen that municipalities lack the professional and organizational capacity to support sick-listed people as health services are a regional responsibility. Taken together, the institutional layering through rescaling had severe effects both on municipalities and on the recipients who were denied sickness insurance.

Case 2. Personal assistance for people with significant and long-term functional disabilities

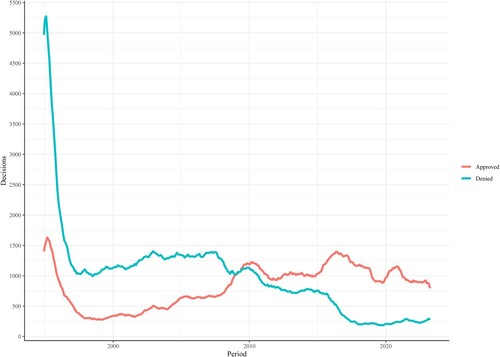

The next case concerns personal assistance for people with significant and long-term functional disabilities. As previously described, this type of support is regulated by the Act Concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments (SFS Citation1993, 387, henceforth referred to as LSS, the abbreviation in Swedish). The law was passed by parliament in 1994 and guaranteed a specific set of services for the target group. Among these, personal assistance has been the most controversial, mainly for two reasons. The first, which will not be discussed extensively here, is the use of private service providers. Disability advocacy organizations were successful in promoting the possibility for service users to choose a service provider and even to act as the employer of his or her personal assistants. This has been controversial due to media exposure of abuse of the system, where service users, parents and/or companies have committed fraud. Further, the involvement of for-profit providers has been criticized as it enhances the commodification of care, whereas relationships between care users and care staff become a commercial transaction (Ungerson Citation1999). The other cause of controversy is the increasing costs of personal assistance. When the bill was proposed, the estimated cost per year was approximately 2.8 billionFootnote4 SEK (Proposition Citation1992/03:159), while in 2020 the cost was 27 billion SEK and the number of services users had doubled in relation to the expected number in 1994 (from 7 000 to almost 13 900 according to Directive Citation2021, 76). It is against this background that we must view the second case in this paper. There have been repeated political attempts to reduce public spending on personal assistance. However, strong disability advocacy organizations have often been successful in preventing changes in the regulatory framework. But in 2015 an unexpected change occurred as the number of service users began to decline. In 2015, there were 16,000 service users, while in 2019 the corresponding figure was 14,000. The approval rate of applications fell from 42 per cent in 2014–2017 per cent in 2019 for people between 0 and 19 years of age, while the corresponding figures for people above 19 years of age were 35 per cent in 2014, and 15 per cent in 2019. The Social Insurance Agency (Citation2020) explains the decrease through a combination of precedent-setting legal cases in 2015, changes in legislation, and regulation of the assessments made by the agency. Hence, while part of the change can be explained by changes in legal praxis, it is important to recognize the active role of the government in reducing the number of approved applications.

It must be noted that the number of users of personal assistance services can decline in two ways. First, people who have been approved for personal assistance may be re-assessed and denied future services. Secondly, fewer first-time applicants may be denied services to begin with, which over time reduces the number of service users. Starting with the first way, until 2018 the Social Insurance Agency was required to assess service users’ need for personal assistance biannually. The Agency reported (Citation2020) that one explanation for the decreasing number of service users in 2017 was a backlog of cases that had not been assessed. Because these backlog cases were assessed after the above-mentioned precedent-setting legal cases, a greater proportion of service users were denied renewed personal assistance. Again, what has been described so far concerns service users who had already been deemed eligible for personal assistance but were denied continued services in a biannual assessment. While this group has shrunk, because the biannual assessments were discontinued in 2018, one must also consider first-time applicants who were denied services due to the changes in legal praxis. If we look at first-time applicants, , it is obvious that the long-term trend is decreasing.

Recalling the dual responsibility for personal assistance, with municipalities administering services for people with less than 20 h of assistance per week, it is not surprising that the municipal costs for LSS services increased. As the National Social Insurance Agency became more restrictive in approving personal assistance, the municipal burden of assisting these people increased (National Board of Health and Welfare Citation2023). However, this is not the full picture. One must also consider people who received services based on the Social Services Act, as they had been denied personal assistance either entirely, or above 20 h per week (cf. SOU Citation2023, 9). When considering this issue, it is important to recall the regulatory differences between LSS and the Social Services Act. While LSS stipulates that service users ought to have ‘good living conditions’ (Sw. goda levnadsvillkor), the Social Services Act refers to ‘decent living conditions' (Sw. skälig levnadsnivå). This is far from just a matter of legal jargon, as it impacts the quality of services. ‘Good living conditions’ means that the service user must be able to lead a life similar to that of people without a disability (SFS Citation1993, 387, 5 §). The clearest illustration of this is the right to personal assistance, as service users are typically not institutionalized and do not have to share care workers with other service users. In comparison, the Social Services Act is much less ambitious. It does not include a catalogue of services. Instead, because it is a regulatory framework, it is up to municipalities to choose what services to provide for people with disabilities to enable them to have ‘decent living conditions’. This means there is a greater risk of inequalities in the level of services between service users living in different municipalities. The Independent Living Institute, a Swedish NGO, argues that there is an emerging ‘re-institutionalisation’, i.e. a development (or degression according to the authors) where people with disabilities are co-located into communal housing forms to decrease spending on more service-intensive and personalized care services such as personal assistance (Karlsson and Bolling Citation2022).

Looking at the case in terms of the theoretical framework, the combination of precedent-setting legal cases, changes in legislation, and the changed praxis of the Social Insurance Agency is an example of layering, as existing institutions remain formally intact but lead to new outcomes, with municipalities facing increasing costs as the national administration imposes increasing restrictions. Thus, the division of responsibilities was partially rescaled from the national to municipal level, which increased the pressure on municipal budgets and administration. Furthermore, these rescaling processes increased the risk of inequalities between people with disabilities based on place of residence, as municipalities are likely to differ in terms of needs assessments and quality of services.

Discussion

The introduction of this paper started from the common image of Sweden as a universal welfare state; an assumption often associated with its Nordic neighbours as well (cf. Esping-Andersen Citation1990). While it remains true that Swedish people mainly rely on public support, rather than family and/or occupational welfare, the idea that Sweden offers genuinely universal support is highly questionable, as has been illustrated by the two cases presented in this paper. As was argued in the introduction, the idea of universalism must not only be assessed in relation to whether people receive public support but also with regard to the political-administrative level at which this support is provided. Already in 1987, Marklund and Svallfors (Citation1987) acknowledged the emerging dualization as an increasing proportion of the population relied on social assistance rather than unemployment benefits. A similar pattern was discussed in 1997 by Salonen (Citation1997), who argued that the central government passed the buck to the municipalities when imposing austerity measures on unemployment benefits (and thereby forcing people to apply for municipal social assistance). This paper adds to the previous literature by illustrating the persistence of this pattern within financial support caused by austerity measures within sickness insurance. It further exemplifies dualization in areas outside of financial support, in this case, care for people with disabilities. In both cases, a consequence of rescaling is increased reliance on municipal administration and funding. Again, it is important to stress that the two cases are not merely administrative reforms or adjustments. Rather, they are symptoms of the demise of national institutions stemming from attempts to hollow out the welfare state. Peck (Citation2002) describes how rescaling becomes a driver in cutbacks as local actors become involved in policy-making and ‘local innovation' to tackle increasing costs. In both cases investigated in this paper, the rescaling resulted in increasing numbers of sick-listed people and people with disabilities becoming subject to the 290 different municipal administrations. These municipalities are subject to budget constraints and have incentives to ration services, which was illustrated in both cases as sick-listed individuals were forced to dispose of assets such as cars, and people with disabilities were re-institutionalized by having personal assistance replaced with less service-intensive care (cf. Brenner Citation2004b; Jessop Citation1999; Peck Citation2002).

From a geographic perspective, the rescaling from the central state to municipalities in Sweden is questionable, given the difference in the economic and social situations between municipalities, which in turn generates inter-municipal inequalities in terms of service provision. The strong autonomy of Swedish municipalities, and their extensive responsibility for providing services, make inequalities based on place of residence unavoidable. The question then becomes: In what types of social policies should we accept such inequalities? The selection of the two cases studied in this paper, sickness insurance and personal assistance, came about through the idea of rights-based support (Brauer Citation2022; Hollander Citation1995). The gradual institutional change that has been demonstrated in these two cases shows that such ideas can easily be subjected to austerity measures despite the lofty expectations regarding human rights.

Another geographical aspect of these cases concerns mobility. As responsibilities are rescaled from the state to municipalities, service users in both cases become reliant on the assessments made by their local municipal administrations. This means that if a service user wants to move to another municipality, he or she is not guaranteed equal-quality services in the new municipality which is likely to generate lock-in effects as inhabitants choose to stay within their municipality based on the fear of being denied services. Such risks do not arise when people receive services from the national systems, as their centralized assessments are not tied to their place of residence.

On a final note, it must be stressed that the institutional change described in the two cases is not unidirectional in the sense that rescaling always occurs from the national to municipal level. In fact, the Sickness Benefit Number has increased in the last couple of years which is visualized in . Looking at the second case, there is a governmental circular submission for comment to nationalize personal assistance which would decrease the costs for municipalities (SOU Citation2023, 9). There are also ways for municipalities to pursue ‘upward cost-shifting', i.e. to move costs to the central state. For instance, municipalities have ‘transposed' costs for social assistance to subsidized employment funded by the central government (Brauer Citation2022). Taken together these cases should be a warning against a unidirectional view of rescaling in the Swedish context. However, the reliance on municipalities as the ultimate responsible makes municipalities vulnerable to austerity measures imposed by the central government – austerity measures that can be announced on short notice as illustrated in the two cases described in this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The sickness benefit number is the aggregated number of benefit days (including both sickness insurance and rehabilitation grants) divided by number of insured people in the age range 16–64 years.

2 It must be stressed that sickness benefit number had been affected even more after reforms made by the Alliance Government which is visualized in . The difference however, is that the Social-Democratic/Green-party government used the sickness benefit number as an explicit yardstick in the governance of the social insurance agency.

3 It should be noted that they are also an employers’ organization, i.e. a social partner involved in collective bargaining within the public sector. Hence, they had a stake in the outcome, both from the perspective of reducing cost-shifting (from sickness insurance to social assistance) and as an employer of sick-listed people employed by municipalities and regions.

4 Adjusted for inflation based on calculation tools provided by Statistics Sweden. The original approximation was 1.6 billion SEK

References

- Altermark, Niklas. 2020. Avslagsmaskinen: byråkrati och avhumanisering i svensk sjukförsäkring [The Rejection Machine: Bureaucracy and De-humanisation in Swedish Sickness Insurance]. Stockholm: Verbal förlag.

- Bonoli, Giuliano, and Philipp Trein. 2016. “Cost-Shifting in Multitiered Welfare States: Responding to Rising Welfare Caseloads in Germany and Switzerland.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 46 (4): 596–622. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjw022.

- Brauer, John. 2021. “Labour Market Policies on a Sub-national Level.” SN Social Sciences 1 (154): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00163-0.

- Brauer, J. 2022. “Labour Market Policies: Structure and Content, Space and Time.” PhD Diss., Örebro University.

- Brenner, Neil. 2004a. “Urban Governance and the Production of New State Spaces in Western Europe, 1960-2000.” Review of International Political Economy 11 (3): 447–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969229042000282864.

- Brenner, Neil. 2004b. New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- County of Stockholm. 2014. LSS – The Law Regulating Support and Service to Persons with Certain Functional Disabilities – in Brief. Stockholm: County of Stockholm.

- Cox, Robert H. 2004. “The Path-Dependency of an Idea: Why Scandinavian Welfare States Remain Distinct.” Social Policy & Administration 38 (2): 204–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2004.00386.x.

- Directive 2021:76. Statlig huvudmannaskap för personlig assistans [National responsibility over personal assistance].

- Erlingsson, Gissur, and Anders. Folkesson. 2022. “Mellankommunal samverkan – är det värt det? En explorativ ansats” [Inter-municipal Collaboration – Is It Worth It? An Explorative Approach].” Statsvetenskaplig tidskrift 124 (2): 493–509.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity.

- Högström, John, and Gustav Lidén. 2023. “Do Party Politics Still Matter? Examining the Effect of Parties, Governments and Government Changes on the Local Tax Rate in Sweden.” European Political Science Review 15: 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000388.

- Hollander, Anna. 1995. Rättighetslag i teori & praxis [Law of Rights in Theory and Practice]. Uppsala: Iustus förlag.

- Jessop, Bob. 1999. “The Changing Governance of Welfare: Recent Trends in its Primary Functions, Scale, and Modes of Coordination.” Social Policy & Administration 33 (4): 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00157.

- Jessop, Bob, Neil Brenner, and Martin Jones. 2008. “Theorizing Sociospatial Relations.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26: 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1068/d9107.

- Karlsson, Riitta-Leena, and Jamie Bolling. 2022. Freedom to Choose with Whom, Where, and How You Want to Live – Deinstitutionalisation (DI) in Sweden. Stockholm: Independent Living Institute.

- Korpi, Walter. 1975. “Poverty, Social Assistance and Social Policy in Post-war Sweden.” Acta Sociologica 18 (2-3): 120–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169937501800203.

- Ladner, Andreas, Nicolas Keuffer, Harald Baldersheim, Nikos Hlepas, Pawel Swianiewicz, Kristof Steyvers, and Carmen Navarro. 2019. Patterns of Local Autonomy in Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lidström, Anders, and Nils Hertting. 2022. “Limited, Fragmented and Powerless: National Urban Policies in Sweden.” In A Modern Guide to National Urban Policies in Europe, edited by Karsten Zimmerman, and Valeria Fedeli, 268–283. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mahoney, James. 2000. “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology.” Theory and Society 29 (4): 507–548. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007113830879.

- Mahoney, James, and Kathleen Thelen. 2010. “A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change.” In Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power, edited by James Mahoney, and Kathleen. Thelen, 1–37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Marklund, Staffan, and Stefan. Svallfors. 1987. Dual Welfare: Segmentation and Work Enforcement in the Swedish Welfare System. Umeå: Research Reports from the Department of Sociology.

- Municipality of Stockholm. 2020a. Tidigt stöd inom ekonomiskt bistånd och missbruk. Effektiva tidiga insatser inom socialtjänsten – Rapport 1 [Early Support Within Social Assistance and Addiction. Efficient Early Interventions Within Social Services – Report 1]. Stockholm: Municipality of Stockholm.

- Municipality of Stockholm. 2020b. Tidigt stöd för att minska långvarigt behov av försörjningsstöd [Early Support to Decrease Long-Term Need of Social Assistance. Efficient Early Interventions Within Social Services – Report 2]. Stockholm: Municipality of Stockholm.

- National Board of Health and Welfare. 2023. Insatser och stöd till personer med Funktionsnedsättning. Lägesrapport 2023. [Programmes and Support for People with Disabilities. A Description of the Situation 2023]. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare.

- Patton, Michael Q. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. London: Sage Publications.

- Peck, Jamie. 2002. “Political Economies of Scale: Fast Policy, Interscalar Relations, and Neoliberal Workfare.” Economic Geography 78 (3): 331–360. https://doi.org/10.2307/4140813.

- Pierson, Paul. 2000. “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics.” American Political Science Review 94 (2): 251–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586011.

- Pierson, Paul. 2015. “Power and Path Dependence.” In Advances in Comparative-Historical Analysis, edited by J. Mahoney, and K. Thelen, 123–146. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Powell, Martin, Erdem Yörük, and Ali Bargu. 2019. “Thirty Years of the Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism: A Review of Reviews.” Social Policy & Administration 54 (1): 60–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12510.

- Proposition 1992/93:159. Regeringens proposition 1992/03:159 om stöd och service till vissa funktionshindrade [Governmental Proposition 1992/03:159 Concerning Support and Services for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments].

- Proposition 2007/08:136. En reformerad sjukskrivningsprocess för ökad återgång i arbete [A reformed sick leave process to increase return-to-work].

- Proposition 2015/16:1. n.d. Budgetpropositionen för 2016. Förslag till statens budget för 2016, finansplan och skattefrågor [Budget Bill. Proposal of public budget for 2016, budget statement and questions related to taxes].

- Salonen, Tapio. 1997. Övervältringar från socialförsäkringar till socialbidrag [Passing the Buck from Social Insurance to Social Assistance]. Lund: Lunds Universitet. Research Reports in Social Work, 8.

- SFS 1993:387. Lag om stöd och service till vissa funktionshindrade [Act Concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments]. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-1993387-om-stod-och-service-till-vissa_sfs-1993-387.

- SFS 2001:453. Socialtjänstlag [Social Services Act].” https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/socialtjanstlag-2001453_sfs-2001-453.

- SFS 2004:881. Förordning om kommunalekonomisk utjämning [Decree Concerning Equalisation of costs between municipalities]. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/_sfs-2004-881.

- SFS 2008:776. Förordning om utjämning av kostnader för stöd och service till vissa funktionshindrade [Decree Concerning Equalisation of Cost for Support and Services for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments]. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/forordning-2008776-om-utjamning-av-kostnader_sfs-2008-776.

- Social Insurance Agency. 2020. Svar på regeringsuppdrag. Rapport – Analys av minskat antal mottagare av assistansersättning. [Response to the Government’s Request – Analysis of Reduced Number of Recipients of Assistance Benefits]. Stockholm: Social Insurance Agency, report 001381-2020.

- SOSFS 2013:1. “Socialstyrelsens allmänna råd om ekonomiskt bistånd [General Recommendations Concerning Social Assistance delivered by the National Board of Health and Welfare].” https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/kunskapsstod-och-regler/regler-och-riktlinjer/foreskrifter-och-allmanna-rad/konsoliderade-foreskrifter/20131-om-ekonomiskt-bistand/.

- SOU 2023:9. Ett statligt huvudmannaskap för personlig assistans [A national responsibility for personal assistance].

- Streeck, Wolfgang, and K. Thelen. 2005. “Introduction: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies.” In Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies, edited by W. Streeck, and Kathleen Thelen, 1–30. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. 2011. Gör rätt från dag ett. Ekonomiskt bistånd till långvarigt sjuka bidragsmottagare och personer utförsäkrade från Försäkringskassan [Do Right from Day One. Economic Assistance for Chronically ill Recipients and People de-insured by the Social Insurance Agency]. Stockholm: Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions.

- Swedish National Audit Office. 2019. The Municipal Financial Equalisation System – A Need for More Equalisation and Better Management. Stockholm: Swedish National Audit Office, Report summary, report number RIR 2019:29.

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency. 2015. Läkares upplevelser av kontakter med Försäkringskassan – med fokus på förtroende [Physician’s Experiences of Being in Contact with the Swedish Social Insurance Agency – Focusing on Trust]. Stockholm: Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Social Insurance Report 2015:9.

- Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. 2013. Utvärdering av externa Förvaltningstjänster i premiepensionen. Vilka är de och vad händer efteråt?[Evaluation of External Administrative Services for Contributory Pensions. What Are They, and What Happens Afterwards?]. Stockholm: Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. Report 2013:6.

- Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. 2018a. Förändrad styrning av och i Försäkringskassan. En analys av hur regeringens mål om ett sjukpenningtal på 9,0 dagar påverkar handläggningen av sjukpenning. [Changed Management of and Within the Social Insurance Agency. An Analysis of How the Government’s Target of a Sickness Benefit Number of 9.0 Days Influences the Processing of Sickness Insurance]. Stockholm: Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. Report 2018:16.

- Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. 2018b. Regeringens mål om ett sjukpenningtal på 9,0 dagar. En redovisning av hur regeringen styr Försäkringskassan och hur myndigheten arbetar för att bidra till att målet uppnås. [The Government Target of a Sickness Benefit Number of 9.0 Days. An Overview of How the Authority Works to Contribute to Meeting the Target]. Stockholm: Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. Report 2018:17.

- Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. 2022. Avskaffandet av den bortre tidsgränsen En analys av effekterna på långtidssjukskrivnas ekonomiska situation och användning av sjukförsäkringen [Removal of the Closing Bracket. An Analysis of the Effects on Economic Situation and Usage of Sickness Insurance of Long-Term Sick-Listed]. Stockholm: Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. Report 2022:5.

- Ungerson, Clare. 1999. “Personal Assistants and Disabled People: An Examination of a Hybrid Form of Work and Care.” Work, Employment and Society 13 (4): 583–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500179922118132.

- Vingård, Eva. 2015. Psykisk ohälsa, arbetsliv och sjukfrånvaro [Mental Ill Health, Working Life, and Sick Leave]. Stockholm: Forte.