ABSTRACT

Governments around the world acted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic through lockdowns and border closures that had specific impacts on temporary residents (migrants, asylum seekers and refugees). In Australia, there were differential responses across states and territories, and a critical distinction made at Federal government level between permanent residents and citizens as compared to temporary migrants. The result has been the continued Othering of certain groups of Australians of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds as well as migrants and refugees on the basis of racial characteristics and visa status. This paper will consider the period where arguably multicultural policies were ‘on hold’ by investigating the timeline leading up to major policy decisions and the immediate and longer-term after-effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arguably the way in which multicultural communities were treated has shown the superficial nature of multicultural policies in Australia and the lack of more solid foundations in support of what now demographically constitutes a majority of the country's population. Drawing on secondary data analysis, the paper will outline the distance these actions have put between political leaders and multicultural communities, and queries the implications for a sustained commitment to multicultural policies in an era of temporary migration.

Introduction

The official government response to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2 and hereafter COVID-19) in Australia comprised a raft of health, security and immigration-related policy decisions. The latter included closing Australia's borders, limiting flight arrivals into the country between March 2020 and November 2021, and making determinations about the ongoing status of people resident in the country on a temporary basis. These decisions were complemented by determinations at state and local levels to also close internal state and territory borders, implement enforceable curfews and movement restrictions that extended to spaces of residence such as apartment blocks (Phillips Citation2020). Temporary migrants and groups such as students and backpackers were quickly cast aside in discussions about citizens and permanent resident who were most in need of Australian government assistance. In a familiar trope, the image of a queue was evoked in matters pertaining to immigration when the then Prime Minister Scott Morrison from the Liberal-National Coalition government laid bare his intentions when he declared.

[A]s much as it's lovely to have visitors to Australia in good times, at times like this, if you are a visitor in this country, it is time … to make your way home. Australia must focus on its citizens and its residents to ensure that we can maximise the economic supports that we have. (ABC News, 3 April Citation2020)

As public concern moved towards issues such as COVID-19 testing, vaccinations and hospitalisation rates there were very few, if any, voices advocating for the rights of migrants – many of whom contributed to the health sector as employees. There was scant reference made to future needs for migrants after the pandemic and even these were highly politicised with some politicians such as the former (Labour) Opposition spokesperson for Immigration Kristina Keneally calling for borders to remain closed (Phillips Citation2020, px). Since then the Australian Labor party government elected in 2022 has renewed a focus on migration with enquiries established on the migration system and Australia's multicultural frameworks, calls for revised migration quotas and other measures such as mobility agreements with the Government of India and increasing the working holiday visa age for some nationalities to up to thirty five years of age (Department of Home Affairs Citation2023).

At a local level during COVID-19, many migrants of Asian origin reported being targeted during the pandemic (Kamp et al. Citation2023) and areas of high migrant concentration such as south-western Sydney were found to have been disproportionately subjected to lockdowns, curfews and fines for breaches of emergency measures (Ore Citation2023). In the state of Victoria, evidence has shown that African and Middle Eastern communities were over-represented in COVID-19 fines with police accused of racial profiling (Briggs and Yusuf, Citation27 June Citation2023). Additionally the Victorian ombudsman found that a decision to lock down Melbourne public housing towers which comprised residents of diverse ethnicities including migrants and refugees breached human rights obligations (Robinson et al. Citation2021). More widely an Australia-wide study of 6100 international students, temporary visa holders including Working Holiday Makers, Temporary Graduate visa holders, Temporary Skill Shortage visa holders, refugees and people seeking asylum highlighted experiences of dire hardship, racism and feelings of exclusion and abandonment during the COVID-19 pandemic (Berg and Farbenblum Citation2020). As this article will show the reactions of some peak representative groups and political leaders tended to reinforce the widely held belief that exceptional times justified extreme measures. Arguably commitments to access, equity, inclusion and diversity were, along with multiculturalism more broadly, put on hold. Similar responses can be found in other contexts around the world that match the ‘exclusionary trends and perceptions of others’ during the pandemic emergency (Triandafyllidou Citation2023: 2). As Triandafyllidou goes on to observe, in contexts like Australia where people co-exist with multiple immigration statuses, the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have been to call into question who is an insider or outsider in a way that established notions of multiculturalism and citizenship could not accommodate. For Triandafyllidou this has emerged from a growing attention to the ways in which the nation interacts with ‘others’ through the lens of both multicultural citizenship and immigration. As Teo queries, ‘if we accept culture as an objective good, all individuals, regardless of their citizenship status, should have access to protections and cultural accommodations’ (Citation2021, 170). The ways in which policy decisions were made for temporary residents in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia as discussed in this paper highlight the potential limitations of established notions of multiculturalism that tend focus on people staying for longer periods in the country such as permanent residents and citizens.

Drawing on a thematic analysis of grey literature, press releases, NGO reports and analysis of media content between 2020 and 2021, this article will show how the pandemic tested the limits of multiculturalism, through the actions and representations of migrant and refugee groups during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. It will focus on the Othering of certain groups of Australians of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds as well as migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on the basis of racial characteristics, visa status as well as geographic location and show how this is a continuation of long-existing patterns rather than an exceptional difference experienced during COVID-19. This article will also seek to investigate the reasons for this by drawing on criticisms of multicultural policy in Australia and literature on pandemic nationalisms (Triandafyllidou Citation2023). More broadly it highlights the limitations of multiculturalism in its current iteration in Australia and queries the values of stated commitments to access and equity if they are not upheld during periods of crisis.

Background – Multicultural Policies in Australia

Too often discussions about migrant settlement in Australia begin with the White Australia policy as evidence of the exclusionary and racist nature of immigration in Australia (see, e.g. Jayasuriya 2012 cited in Galligan et al. Citation2014). Yet Australia's Indigenous people, who were forcibly displaced from their lands and denied traditional ownership, were also subject to a violent form of ‘settler sovereignty’ from British settlement in 1788 that enacted British law alongside racist practices and denial of fundamental rights to Indigenous Australians (Ford Citation2010). Without conflating what are different experiences, the techniques used by what Hage terms ‘White National managers’ in the policy domains of migration and the treatment of Indigenous Australians have similar elements of exclusion and denial underpinned by racist ideologies (Hage Citation2012; see also Irving Citation1997). It is therefore critical to not see the White Australia policy as a starting point, but instead a continuation of restrictive policies that were put in place to uphold the myth of Australia as British (Protestant) and White (Jupp Citation1995). While a discussion about the race power built into the Australian constitution is beyond the scope of this article it is arguably the most powerful example of the way in which colour and race was framed in early British settlement (Galligan et al., Citation2014).

Turning to early migration policies, the Commonwealth Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 set about controlling entry to Australia and the racial characteristics of migrants. Now more commonly referred to as the White Australia policy, this Act envisaged Australia as a white nation where people were permitted entry on the basis of a dictation test in any European language, with the choice of language being decided by the immigration officer. The need to populate the country after World War Two brought what Tavan termed the ‘slow death of White Australia’ through increases in European migration especially from countries such as Italy and Greece and the establishment of a Department of Immigration and the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) (Tavan Citation2005). Additionally Australia was engaging within the Asian region and so former assimilationist models were increasingly relaxed until such time as a multicultural model was adopted drawing in migrants from Asia, the Middle East and Latin America under the Whitlam Australian Labor Party government which officially ended the White Australia policy in 1973, introduced multiculturalism and established responsible government agencies such as the Community Relations Commission (Jupp Citation1995). This forms what Castles terms a ‘complex legal, institutional and administrative framework which regulates immigration and settlement’ and included specific visa categories based on economic, family or humanitarian attributes (Citation1992, 552). First used in a 1972 speech by the then Minister for Immigration, Mr Al Grassby, multiculturalism came to be understand as cultural pluralism although it has over time included elements of social cohesion (Boese and Phillips Citation2011, 190). There are wider debates about multiculturalism as compared to interculturalism which are beyond the scope of this paper but highlight that multiculturalism itself is a contested concept (Meer and Modood Citation2012).

Multiculturalism was at this earliest iteration both a response to the new reality of a much more ethnically diverse Australia and an indication of the need to reorient attention to the social, economic and cultural benefits of newcomers that moved away from assimilationist models of integration. As Castles notes a similar situation was faced by other countries who had supported large-scale immigration and now needed to find ways to manage this diversity with some turning to more assimilationist approaches and others, including Australia, adopting an ‘ethnocultural pluralistic’ vision of society (Citation1997, 9). A raft of measures were introduced in Australia exemplifying this approach including setting up the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS), grants to ethno-specific organisations and an extension of Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) were initiated in the mid-1970s and since this time multiculturalism has become the ‘new normal’ for migration policies in Australia. At a practical level, today multiculturalism incorporates policies, programs and the acknowledgement and in some cases funding of special interest groups such as the Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Council (FECCA) and multiple advisory groups. However, as this paper will demonstrate through a focus on the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, the reality of multiculturalism has had a much bumpier journey.

The scholarship of Ghassan Hage has most acutely problematised the challenges of multiculturalism in a country such as Australia (Citation2023). This includes, as was detailed earlier, racist practices and dispossession of Indigenous Australians through structural violence embodied in the constitution. There is also the decades long system of mandatory detention of asylum seekers and turnback of boats as well as offshore detention and incarceration that breaches Australia's international human rights commitments (Phillips and Gottardo Citation2023). Reconciling a commitment to multiculturalism in a dominant ‘White’ culture and grappling with its state-sponsored nature leads to, what Hage describes as, an ‘intolerance’ of those who go beyond imagined limits of a national identity (Citation2023). Yet in the case of groups of migrants who were deemed intolerable during COVID-19 and were advised to return back to their countries of origin, their intolerable nature of being permanent residents or temporary visa holders was, this paper will demonstrate, a creation of White national managers who determine an ever-increasingly complex array of visa categories and legislation. Even in its most docile form, multiculturalism relates to commitments to access and equity that include accessible service provision irrespective of culture, language and religion; a responsibility of government departments at all levels to offer services to all including through adapting services and incorporating cultural diversity principles into policy and program design, implementation and service delivery (Access and Equity Inquiry Panel Citation2012). Access and Equity commitments are overseen by the Department of Home Affairs with reporting to the Australian Multicultural Council, however, there are no penalties for non-compliance. The experience for people from diverse backgrounds during COVID-19 calls into question both these stated commitments to access and equity as well as the overarching value of multiculturalism. The next section sets out attributes of different groups resident in Australia at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and is followed by a discussion of the methodological approach employed in this paper.

Locating Australia’s Diverse Populations

As a country of immigration Australia relies heavily on temporary and permanent migration to boost population and meet gaps in the labour market with a consequent emphasis on pathways to citizenship to ensure immigration serves a political imperative (Galligan et al. Citation2014; Wright and Clibborn Citation2020; Boese Citation2023). In recent years, temporary migration has outstripped permanent migration categories with around three-quarter of a million migrants arriving annually on visas for international students, working holiday makers, seasonal workers and temporary skilled (employer sponsored) migrants (Wright and Clibborn Citation2020; Collins Citation2017: 71). This compares to around 200,000 permanent migrants (skilled migrants and family members) and 10,000 entrants under the humanitarian program comprising refugees and asylum seekers as well as people on temporary or safe haven humanitarian visas. While this extraordinary shift is both a numerical increase and change away from permanent residence that has been shaped by public discussions about the need for skills, and meeting skill shortages, there is growing evidence about the risks associated with employer driven schemes and the impact on community dynamics especially at a local level (see, e.g. O'Brien and Phillips Citation2015; Boese and Macdonald Citation2017; Wright et al. Citation2016; Boese and Phillips Citation2017; Boese and Robertson Citation2017). For instance Boese and Phillips find that conditional belonging due to temporary visa status has potential impacts for migrant attraction and retention as well as long-term settlement in Australia and that overarching regulatory constraints for temporary migrants hinder local efforts to build trust with migrants (Citation2017). They go on to note that temporary migrants are constrained by legal and policy restrictions but may gain a sense of belonging due to their economic contributions to local communities and to Australia more broadly especially when they are supporting local employers in regional towns where they are filling skills shortages.

As was discussed earlier, the ethnic, religious, linguistic and cultural diversity of migrants has continued to grow and this feature has shaped federal and state government multicultural policies and access and equity commitments. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data shows an increase in the number of people born overseas to 27.6 per cent of the population in 2021with India now the second-highest country of birth after England and followed by China, New Zealand and Philippines (ABS Citation2022). The five main languages other than English spoken at home are Mandarin, Arabic, Vietnamese, Cantonese and Punjabi. The category culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) has come to be associated with migrant and refugee communities most especially for policy considerations. However as Maturi and Munro note the singular nature of this category can obscure a focus on intersectionality and as they show

the category of CALD is a discursive mechanism that allows the tokenistic inclusion of diversity while disappearing inequalities. Moreover, the culture in CALD obscures different forms and experiences of inclusion and exclusion, preventing intersectionality from having transformative effects. (Citation2023, 146)

Methodology

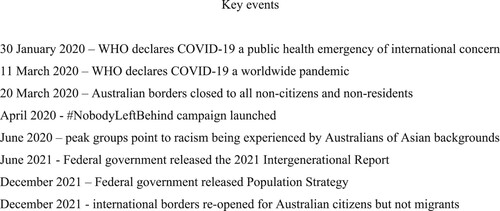

This article draws on a desk-based review of data that was selected for portrayals of asylum seekers, migrants and refugees during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic (see ). A scoping of newspaper articles was conducted given that it is well understood the ways in which media coverage informs public policy agendas and stereotypes especially in the domain of migration (Cengiz and Eklund Karlsson Citation2021). Grey literature incorporating press releases and NGO reports (including annual reports) from organisations that support migrants and refugees or have a stated mission focused on multiculturalism was also included noting that many were produced in reaction to policy announcements and were also trying to shape public reactions most notably to draw attention to the plight of migrants and refugees amidst a crowded news cycle (McLaughlin and Neal Citation2004). Media releases from Federal Ministers for Immigration were also part of the scope for this article. All data collected was within the date parameters of between March 2020 when international border restrictions were implemented and December 2021 when international borders re-opened for Australian citizens but not migrants.

Table 1. Data sources.

The content analysis of major Australian newspapers was carried out through a keyword search with the Factiva and ProQuest databases using search terms ‘COVID-19’, ‘migrants’, ‘refugees’, ‘multicultural*’ and ‘migration’ for articles published between the same dates from March 2020 to December 2021. This method has been employed in other studies of public representation of issues related to migrant and refugee groups and the news worthiness of issues about particular ethnic groups (see, e.g. Nolan et al Citation2016). It also builds on recent research that considers media reporting on COVID-19 (Georgeou et al. Citation2023) and the ways in which COVID-19 highlighted structural barriers faced by migrants and refugees in Australia (Couch et al. Citation2021; Robinson et al. Citation2021; O’Mara et al. Citation2022) and other countries around the world (Zapata and Prieto Rosas Citation2020). The initial search yielded 2430 articles which were scanned for keywords noted above. After duplications or articles that were simply headlines with repetitions this number was further refined to 184 documents. The material was collated in a chronological order mirroring the timeframe of events (see ) with categories informed by the author's understanding and interpretation related to the treatment of migrants and refugees and themes of ongoing commitments to multiculturalism and access and equity which informs the public policy implications discussed in this paper.

Anatomy of a Retreat from Multiculturalism

This section highlights the way in which actors in the immigration portfolio responded to the COVID-19 pandemic discussed alongside the media analysis conducted for this article. It takes a chronological approach to follow how decisions were made and policies adjusted over the height of the pandemic (see ). While there were many health stakeholders who generated advice relevant to migrants and refugees, this is beyond the scope of this article and has not been included in the analysis and therefore the sample focuses on the organisations set out in . Following the announcement on 30 January 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO) of a public health emergency of international concern, the Australian government made multiple travel advice decisions leading to the action to close Australia's borders to all non-citizens and non-residents from 20 March 2020 with only Australian citizens, residents and immediate family members permitted to travel to Australia (Campbell and Vines Citation2021). The Acting Minister for Immigration encapsulated the division between certain groups of migrants and refugees when he stated that ‘Australians and permanent residents must be the Government's number one focus’ (Coleman March 2020). Temporary residents including people seeking asylum on bridging visas, refugees, temporary migrant workers and international students were not eligible for support packages given to permanent residents or citizens who lost jobs or were unable to work, known as Job Keeper although they could withdraw funds from superannuation balances.

The concerning and significant gaps created by this decision for temporary migrants and asylum seekers resulted in the launch of a #NobodyLeftBehind campaign signed by 186 organisations that spelled out:

We are experiencing an unprecedented global crisis that affects us all. The Morrison government has responded decisively yet it has left behind almost 1.1 million temporary visa holders including hundreds of thousands of people seeking asylum and refugees. When people can't buy food, can't pay their rent, can't buy critical medicines, they can't stay safe. That puts them and their families as well as the broader community at risk. We can leave nobody behind. (Refugee Council of Australia, 9 May 2020)Footnote1)

This campaign was the focus of media releases from other groups such as the Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia (FECCA) calling attention to the unfairness of this measure from both health and social support perspectives but there was little evidence in this analysis of their media releases being picked up in the mainstream media (FECCA 8 April 2020; RCOA, 2 April 2020). A few months later there were references made by peak groups about the racism being experienced by in particular Australians of Asian backgrounds (FECCA 11 June 2020) and CALD health service provision (FECCA 3 August 2020). The Refugee Council of Australia also raised concerns about the situation of people in immigration detention who faced overcrowded conditions. Footnote2

Media reporting in the timeframe in scope for this article was found to largely be stories on migration levels including discussing potential post-pandemic immigration levels and human-interest stories of migrants separated from children (see, e.g. Fitzsimmons, 26 December Citation2021, ‘'Foxed at every turn': The people who still can't come to Australia’ and Campbell, 23 December Citation2021, ‘Should we turn the migration tap on?). There was some mention in media reports analysed for this paper of racism, linked to the release of a Scanlon Foundation Research Institute report on social cohesion (see for instance Lunn, 30 November Citation2021, ‘Sharp rise in racism concerns’). Other news reports made reference to a political issue of ‘token multiculturalism’ emerging from the decision of the Federal Labor party, then an opposition party, to pre-select a high profile former Premier of New South Wales who is a white woman to a highly diverse seat in metropolitan Sydney over a potential locally based candidate from a diverse cultural background (see for instance Curtis, 18 September Citation2021, ‘Diversity debacle: How to make Parliament look like Australia’ and Harris, 14 September Citation2021, ‘Embracing diversity could be Albanese's key to the Lodge’). Regarding the slowdown in population growth caused by the changes in international migration, media interviews with politicians raised the economic impacts on specific sectors like construction,Footnote3 as well as the resulting experience of negative net overseas migration which was unique in Australia at the time. In June 2021, the Federal government released the 2021 Intergenerational Report followed by its Population Strategy in December 2021 that also saw continued media references to population levels linked to migration.

As discussions moved in late 2021 towards reopening borders, government media releases demonstrated the continued the way in which temporary residents were seen through a limited and limiting lens of economic benefits to the Australia economy. Take for instance the comments from Former Acting Minister Alan Tudge who welcomed borders reopening because ‘we've got a lot of fruit to pick’ Footnote4 and in November 2021 former Minister Alex Hawke made a determination that allowed international students to exceed the cap on working hours to assist supermarkets.Footnote5 Media reports also referred to the potential skilled and unskilled labour that would return to the country when ‘internationals’, as one paper referred to migrants made their return to the country (Gould, 14 December Citation2021, ‘Nation on track to open for migrants). A November 2021 Australian Financial Review opinion piece from an industry leader maintained a familiar focus on the economic benefits of migration but also stated that ‘the public certainly enjoys [the] fruits [of migration] – the jobs, prosperity, vitality and multiculturalism’ (Morrison, 30 November Citation2021, ‘We must switch back on the population growth engine’). This was a rare reference to attributes brought by migrants outside of skills and economic benefits to the country. When international borders re-opened for Australian citizens but not migrants it signals an end of the focus for period for this paper. The next section of this paper analyses the findings from this media analysis and considers the wider implications for multiculturalism in Australia.

Implications for a Multicultural Australia

If we focus on the things that actually enable communities to succeed and individuals to succeed, then multiculturalism and social cohesion is the by-product of that. So long as we identify things that might get in the way for particular communities or disadvantage them in terms of their participation.Footnote6

Scott Morrison, former Australian Prime Minister

The data outlined in the previous section illustrates two striking aspects. First that at a moment of national emergency situated within a global pandemic, temporary migrants of all categories were immediately divided from permanent residents and citizens and told they were not the priority of the Australian government and in some instances not deserving of social assistance packages designed to help people in need during COVID-19 who may have lost jobs. For example in April Citation2020, the Minister for Immigration David Coleman outlined:

There are 2.17 million people presently in Australia on a temporary visa. All were welcomed to Australia on a temporary basis for different reasons […] They are an important part of our economy and society. For example, there are over 8,000 skilled medical professionals on temporary visas supporting our health system right now. While citizens, permanent residents and many New Zealanders have access to unconditional work rights and government payments (including the new JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments), temporary visa holders do not. There has always been an expectation that temporary visa holders are able to support themselves while in Australia. […] Temporary visa holders who are unable to support themselves […]. For these individuals it's time to go home, and they should make arrangements as quickly as possible. […] Temporary visa holders are extremely valuable to the Australian economy and way of life, but the reality is that many Australians will find themselves out of work due to the dual health and economic crisis we're currently facing, and these Australians and permanent residents must be the Government's number one focus.

(Coleman, 4 April Citation2020)

Second the attributes associated with migrants in mainstream media discussions and at a federal political level were almost solely centred around economic benefits with the Minister above specifically calling out the economic and social benefits of temporary migrants. The decision to ask temporary migrants to leave Australia was inconsistent with other countries that did not close their borders to migrants or initiate deportations or repatriations (see, e.g. De Nardi and Phillips Citation2021, see also Triandafyllidou Citation2023). This reflects Triandafyllidou's assertion that in countries with people with multiple immigration statuses ‘it became soon clear that decisions had to be made and boundaries (re)drawn about who belongs and is entitled to rights of entry, stay and welfare, and who does not’ which has significant implications for their belonging and notions of what she terms ‘effective membership’ (Citation2023, 7). She goes on to suggest that countries which decided to extend stay permits, support regularisation or offer automatic visa renewals saw migrants as part of the national imaginary, to use Hage's term, who shared a similar experience to nationals of those countries. This was clearly not the case in Australia where temporary migrants were explicitly told they were not the governments priority and were excluded at multiple levels and some CALD communities faced racist attacks.

As was noted earlier, access and equity refers to commitments at all levels of public institutions to provide services to all communities equally. This is reinforced through policies on multiculturalism which is overseen by a Federal Minister with some states and territories having appointed Ministers for Multiculturalism. The data outlined above shows that gaps emerged during COVID-19 whereby groups of temporary migrants were denied social assistance and were left to fend for themselves, others such as people in immigration detention remained confined with potentially greater health risks and others still faced further distress due to racist attacks targeting them due to their cultural and ethnic origins or in some jurisdictions being disproportionately fined by the police for breaches of public health orders. In order to try and address some of these concerns the Migration Council of Australia released a My-Aus COVID-19 mobile phone app and in December 2020 the Federal Department of Health and Aged Care established a CALD Communities COVID-19 Health Advisory Group which is now the Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities Health Advisory Group.Footnote7 The exclusionary nature of decisions made towards temporary migrants outlined here aligns with other scholarship in this domain which has found that the exclusion of temporary migrants from other forms of social assistance produces a form of ‘conditional belonging’ (Boese and Phillips Citation2017). As noted earlier conditional belonging has potential impacts for migrant attraction and retention as well as long-term settlement in Australia and overarching regulatory constraints for temporary migrants hinder local efforts to build trust with migrants. The further disregard for temporary migrants in Australia shown during COVID-19 detailed here and documented by others (Berg and Farbenblum Citation2020; see also other contributions in this special issue) was coupled with an emphasis in some media representations of migrants solely as economic assets who are valued for work, advised to return home during a pandemic and then called back because ‘there is a lot of fruit to pick’. Returning to a theme noted by Teo earlier, if protections afforded to all diverse communities in ‘good’ times do not apply to temporary migrants during a crisis this calls into question the application of multiculturalism as a policy for all migrants and refugees irrespective of their temporary or permanent residence.

In other contexts groups such as Ethiopian migrant domestic workers in the Middle East have been rendered ‘cheap and disposable’ during periods of economic downturn and have found themselves highly vulnerable under conditions of being contracted to employers resulting in their being forced to work without legal status in the Middle East or return back to countries of origin (Fernandez Citation2010). Similarly in Australia temporary migrants who were laid off due to COVID-19 were told to leave the country if they could not secure a new sponsor showing little regard for the links they might had made in Australia or any ambitions to secure permanent status which would be interrupted. Footnote8 Despite multiple and sustained efforts by community groups to advocate for temporary migrants during COVID-19, in many instances their vulnerabilities were amplified suggesting the structural barriers faced by CALD communities.

Conclusion – the Fig Leaf of Multiculturalism

The COVID-19 period offers a recent and unique perspective into what happens in a country of sustained and significantly high rates of permanent and temporary immigration during a period of national and global emergency. Unlike many other countries around the world, in Australia temporary migrants were excluded, made second-tier residents through legal arrangements linked to their visa status and were encouraged to return to their country of origin or support themselves off savings and superannuation. Despite attempts by community organisations to draw attention to their plight, media interest remained at the level of human interest (e.g. adult migrant parents separated from children) and wider debates about post-pandemic immigration levels and population policies. What has been shown here is a cause for concern for both multicultural policy and stated commitments to access and equity principles. First this analysis illustrates that at the first instance of a national and global crisis, there was a demonstrable retreat from multiculturalism with divisions made on the basis of immigration status, diverse communities racially vilified and certain ethnic groups racially profiled by the police and subjected to additional lockdown measures on the basis of their residential location. Second the events during COVID-19 call into question the efficacy of access and equity principles if temporary migrants were deliberately excluded from emergency measures. Finally, as the statement from the then-prime minister noted above lays bare, multiculturalism as a policy is a mere by-product of the governments ultimate aim of economic participation for migrants. Overall, Australia's exclusionary reactions to the pandemic put it at odds with many other multicultural nations around the world which instead chose this moment as a time to consider the shared fate of all persons resident in a country. The question arises as to how Australia can re-conceptualise its commitment to multiculturalism not just in good times but also in challenging and difficult moments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

References

- Access and Equity Inquiry Panel. 2012. Access and Equity for a Multicultural Australia: Inquiry into the Responsiveness of Australian Government Services to Australia s Culturally & Linguistically Diverse Population.

- Adusei-Asante, K., and Adibi, H., 2018. The 'Culturally and Linguistically Diverse '(CALD) Label: a Critique Using African Migrants as Exemplar. Australasian Review of African Studies, 39 (2), 74–94.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/cultural-diversity-australia.

- Berg, L., and Farbenblum, B. 2020. As If We Weren't Humans: The Abandonment of Temporary Migrants in Australia During COVID-19. Available at SSRN 3709527.

- Boese, M., 2023. Migrant and Refugee Retention in Regional Australia at the Intersection of Structure and Agency. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 24 (6), 1145–1166. doi:10.1007/s12134-023-01022-y.

- Boese, M., and Macdonald, K., 2017. Restricted Entitlements for Skilled Temporary Migrants: the Limits of Migrant Consent. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43 (9), 1472–1489. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2016.1237869.

- Boese, M. and Phillips, M., 2011. Multiculturalism and Social Inclusion in Australia. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 32 (2), 189–197. doi:10.1080/07256868.2011.547176.

- Boese, M., and Phillips, M., 2017. ‘Half of Myself Belongs to This Town’: Conditional Belongings of Temporary Migrants in Regional Australia. Migration Mobility and Displacement, 3 (1), 51–69. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/mmd/article/view/17073.

- Boese, M., and Robertson, S., 2017. Introduction: Place, Politics and the Social: Understanding Temporariness in Contemporary Australian Migration. Migration, Mobility, & Displacement, 3 (1), 1–7.

- Briggs and Yusuf. 2023, 27 June. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-06-27/COVID-pandemic-victoria-police-fines-african-middle-eastern/102523060.

- Campbell, R., 2021, 23 December. Should We Turn the Migration Tap on?. The Age.

- Campbell, K., and Vines, E. 2021. COVID-19: a Chronology of Australian Government Announcements (up until 30 June 2020). Parliamentary Library Research Paper Series.

- Castles, S., 1992. The Australian Model of Immigration and Multiculturalism: Is It Applicable to Europe?. International Migration Review, 26 (2), 549–567. doi:10.1177/019791839202600219.

- Castles, S., 1997. Multicultural citizenship: A response to the dilemma of globalisation and national identity?1. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 18 (1), 5–22. doi:10.1080/07256868.1997.9963438.

- Cengiz, P.-M. and Eklund Karlsson, L., 2021. Portrayal of Immigrants in Danish Media—A Qualitative Content Analysis. Societies, 11 (2), 45. doi:10.3390/soc11020045.

- Coleman, D. 2020, 4 April. Coronavirus and Temporary Visa Holders. https://minister.homeaffairs.gov.au/davidcoleman/pages/coronavirus-and-temporary-visa-holders.aspx.

- Collins, J., 2017. Australia’s New Guest Workers: Opportunity or Exploitation? In: Marotta, and Boese, eds. Critical Reflections on Migration,‘Race’ and Multiculturalism: Australia in a Global Context. London: Routledge, 71–87.

- Couch, J., Liddy, N., and McDougall, J., 2021. ‘Our Voices Aren’t in Lockdown’—Refugee Young People, Challenges, and Innovation During COVID-19. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 4 (3), 239–259. doi:10.1007/s43151-021-00043-7.

- Curtis, K., 2021, 18 September. Diversity Debacle: How to Make Parliament Look Like Australia. The Age.

- De Nardi, S., and Phillips, M., 2021. The Plight of Racialised Minorities During a Pandemic: Migrants and Refugees in Italy and Australia. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 41 (1), 98–111.

- Department of Home Affairs. 2023. New Working Holiday (Subclass 417) Visa Arrangements for UK Passport Holders. Available from https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/what-we-do/whm-program/latest-news/arrangements-uk-passport-holders#:~:text=Increased%20eligible%20age%20range%20for,18%20to%2035%20years%20inclusive. Accessed 23 January 2024.

- Fernandez, B., 2010. Cheap and Disposable? The Impact of the Global Economic Crisis on the Migration of Ethiopian Women Domestic Workers to the Gulf. Gender & Development, 18 (2), 249–262. doi:10.1080/13552074.2010.491335.

- Fitzsimmons, C., 2021, 26 December. 'Foxed at Every Turn': The People Who Still Can't Come to Australia. Sunday Age.

- Ford, L., 2010. Settler sovereignty: Jurisdiction and indigenous people in America and Australia, 1788–1836 (Vol. 166). Harvard University Press.

- Galligan, B., Boese, M. and Phillips, M., 2014. Becoming Australian : Migration, settlement, citizenship. Melbourne University Press.

- Georgeou, N., et al., 2023. COVID-19 Stigma, Australia and Slow Violence: An Analysis of 21 Months of COVID News Reporting. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 58 (4), 787–804. doi:10.1002/ajs4.273.

- Gibson, J., and Moran, A. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-03/coronavirus-pm-tells-international-students-time-to-go-to-home/12119568.

- Gould, C., 2021, 14 December. Nation on Track to Open for Migrants. Daily Telegraph.

- Hage, G., 2012. White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society. Routledge.

- Hage, G., 2023. The Racial Politics of Australian Multiculturalism. Sweatshop.

- Harris, R., 2021, 14 September. ‘Embracing Diversity Could be Albanese's Key to The Lodge’. The Age.

- Irving, H., 1997. To Constitute a Nation – A Cultural History of Australia’s Constitution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jupp, J., 1995. From 'White Australia' to 'Part of Asia': Recent Shifts in Australian Immigration Policy towards the Region. International Migration Review, 29 (1), 207–228. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2547002.

- Kamp, A., et al., 2023. Asian Australian’s Experiences and Reporting of Racism During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 1–21. doi:10.1080/07256868.2023.2290676.

- Lunn, S., 2021, 30 November. Sharp Rise in Racism Concerns. The Australian.

- Maturi, J., and Munro, J., 2023. How the ‘Culture’ in ‘Culturally and Linguistically Diverse’ Inhibits Intersectionality in Australia: A Study of Domestic Violence Policy and Services. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 44 (2), 143–159. doi:10.1080/07256868.2022.2102598.

- Mclaughlin, E. and Neal, S., 2004. Misrepresenting the multicultural nation. Policy Studies, 25 (3), 155–174. doi:10.1080/0144287012000277462.

- Meer, N., and Modood, T., 2012. How does Interculturalism Contrast with Multiculturalism? Journal of Intercultural Studies, 33 (2), 175–196. doi:10.1080/07256868.2011.618266.

- Morrison, K., 2021, 30 November. We Must Switch Back on the Population Growth Engine. AFR Online.

- Nolan, D., et al., 2016. “Media and the Politics of Belonging: Sudanese Australians, Letters to the Editor and the New Integrationism.”. Patterns of Prejudice, 50 (3), 253–275.

- O'Brien, P., and Phillips, M., 2015. Health Care Justice for Temporary Migrant Workers on 457 Visas in Australia: A Case Study of Internationally Qualified Nurses. Journal of Law and Medicine, 22 (3), 550–567.

- O’Mara, B., Monani, D., and Carey, G., 2022. Telehealth, COVID-19 and Refugees and Migrants in Australia: Policy and Related Barriers and Opportunities for More Inclusive Health and Technology Systems. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 11 (10), 2368.

- Ore, A. 2023, 4 July. ‘It’s the First Thing That They Look at’: Claims of Racial Profiling Levelled at Victoria Police after Covid Fines Report. Guardian Australia. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/jul/04/racial-profiling-victoria-police-covid-fines-report

- Phillips, M., 2020. Responding to migrant workers: The case of Australia. In: N. Georgeou and C. Hawksley, eds. State responses to COVID-19: A global snapshot at 1 June 2020. Western Sydney University. https://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:56288.

- Phillips, M., and Gottardo, C., 2023. Deconstructing the Myth of the Need for Immigration Detention. In: J. Ravulo, K. Olcoń, T. Dune, A. Workman, and P. Liamputtong, eds. Handbook of Critical Whiteness: Deconstructing Dominant Discourses Across Disciplines. Springer Nature Singapore, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1612-0_49-1

- Robinson, K., Briskman, L., and Mayar, R., 2021. Disrupting Human Rights: A Social Work Response to the Lockdown of Social Housing Residents. British Journal of Social Work, 51 (5), 1700–1719. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcab115.

- Tavan, G., 2005. Long, Slow Death of White Australia. The Sydney Papers, 17 (3/4), 135–139. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.085673809058369.

- Teo, T.-A., 2021. Multiculturalism Beyond Citizenship: The Inclusion of Non-citizens. Ethnicities, 21 (1), 165–191. doi:10.1177/1468796820984939.

- Triandafyllidou, A., 2023. Pandemic Nationalisms. Ethnicities, 23 (4), 616–633. doi:10.1177/14687968221149744.

- Wright, C.F., and Clibborn, S., 2020. A Guest-Worker State? The Declining Power and Agency of Migrant Labour in Australia. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 31 (1), 34–58. doi:10.1177/1035304619897670.

- Wright, C.F., Groutsis, D., and van den Broek, D., 2016. Employer-Sponsored Temporary Labour Migration Schemes in Australia, Canada and Sweden: Enhancing Efficiency, Compromising Fairness? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43 (11), 1–19. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2016.1251834.

- Zapata, G.P., and Prieto Rosas, V., 2020. Structural and Contingent Inequalities: the Impact of COVID-19 on Migrant and Refugee Populations in South America. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 39, 16–22.