ABSTRACT

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) has been increasingly used in the field of inclusive education to develop instruments that predict teachers’ inclusive behaviour. To ensure the instrument developed to measure the constructs of the TPB is closely aligned to the theory, an elicitation study should be conducted as the first step. However, they are often omitted or rarely reported in the literature, particularly in the literature surrounding inclusive education. This study extends the use of the TPB to an under-researched population in higher education, university pathway teachers (UPTs), who work in programs that provide alternative access to university education. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten UPTs from New South Wales, Australia to elicit their salient behavioural, normative, and control beliefs on inclusive education. Directed content analysis results showed that UPTs view inclusive education positively but are concerned with the extra time and work involved. In addition, UPTs believed that students without disability would be potentially opposing inclusive education. UPTs also revealed various essential facilitators and hindrances of inclusive education. These findings have implications for extending understandings of inclusive education to university pathway programs as well as for the importance of elicitation studies when using TPB with new populations.

Introduction

Students with disabilities, as an identified disadvantaged equity group in Australia, continue to face challenges in accessing and participating in higher education (ADCET, Citation2021). Studies about this marginalised group in higher education are less prolific than those in the school settings (Kendall, Citation2018), and those about other marginalised groups in Australia (Heffernan, Citation2022). In a systematic literature review of Australian higher education research studies between 1982 and 2022 on four equity groups (disability, gender, race, and sexual identify), studies focused on disability accounted for less than 10% of the 154 studies identified (Heffernan, Citation2022), demonstrating the need of further research about the inclusive dimension of students with disabilities in the Australian higher education context.

Inclusive education can be challenging to define as it is context-specific (Armstrong et al., Citation2010; Spandagou, Citation2020). This study adopts a narrow definition of inclusive education focusing on the education of students with disabilities in mainstream educational settings (Ainscow et al., Citation2006). Teachers are ‘the key’ to students with disabilities accessing, participating, and learning in all levels of education (UNESCO, Citation2016, p. 54). Particularly, teachers’ beliefs about the education of students with disabilities are crucial because their beliefs could strongly influence their practices (Pajares, Citation1992). While there are studies exploring higher education teachers’ beliefs about and attitudes towards inclusive education (e.g., Lipka et al., Citation2020; Moriña et al., Citation2020), research studies about Australian higher education teachers’ beliefs on inclusive education is minimal, let alone in the under-researched area of university pathways that provide diverse student populations alternative access to higher education. Hence, with the aim to add knowledge to the fields of higher education and inclusive education, with a particular focus on university pathways, this is the first study adopting the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991) to explore Australian university pathway teachers’ (UPTs) salient beliefs towards the inclusion of students with disabilities.

Research context – University pathways

University pathways are an initiative offered by Australian universities to respond to the contextual needs of diversity and inclusion in higher education (Agosti & Bernat, Citation2018; Brett & Pitman, Citation2018). Domestically, they were introduced to provide alternative pathways to university education for students who fell short in the school–university pathway, including those with a disability (Lake et al., Citation1988; NCSEHE, Citation2016). Internationally, these pathway programs respond to the English language and academic learning needs of international students (Agosti & Bernat, Citation2018; Brett & Pitman, Citation2018). Despite having a common goal to widening the access to and participation of the diverse student population to Australian higher education, these programs also share variability as a principal feature between them (Baker et al., Citation2022). For example, there is no common consensus on the term ‘university pathway programs’ in the literature as different terminology, such as enabling, bridging, pathway, university foundation, and diploma, refers to what the present study considers as ‘university pathway programs’. Since it is not the intention of the authors to delve into the naming conventions of these programs, the term ‘university pathway programs’ is used as a context-bound umbrella term in this study to refer to standalone academic programs that aim to prepare students to transition into university undergraduate degrees.

While these programs have differing curriculums, duration, fee structures and are offered in different locations, they are all bound to the Australian federal legislations: Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (Austl.). (DDA, 1992), and the Disability Standards for Education 2005 (Cth) (Austl.). (DSE, 2005 or the Standards) which is a subordinate legislation clarifying the rights of students with disabilities and the legal obligations of the education providers to make education accessible to these students (Pitman, Citation2022). The DSE 2005 is based on the provision of reasonable adjustments for ensuring students with disabilities can access and participate in education on the same basis as students without disabilities. It, however, does not prescribe the specific practices that teachers should adopt for the inclusion of students with disabilities, and such practices may extend beyond the provision of reasonable adjustments. Therefore, it is essential to understand teachers’ beliefs, intention, and behaviours of inclusion to support UPTs’ inclusive practices.

The theory of planned behaviour

The Theory of Planned Behaviour has been applied as the theoretical framework in studies that explored teachers’ intentions towards the inclusion of students with disabilities (Opoku et al., Citation2021), including in contexts such as Belgium and Hong Kong where there are legislations comparable to the DSE 2005 in upholding the rights of students with disabilities to education (e.g., Emmers et al., Citation2020; Yan & Sin, Citation2014). According to the TPB, ‘beliefs are the building blocks’ of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen & Dasgupta, Citation2015, p. 119). They jointly form a person’s behavioural intentions which will become the immediate antecedents of the behaviour in question (Ajzen, Citation2005).

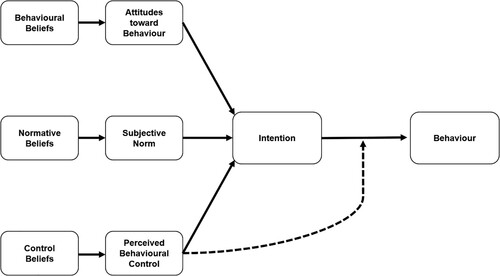

As shown in , a person’s attitude toward a certain behaviour develops from their behavioural beliefs, which is the individual’s subjective evaluation of the outcome of that behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991; Ajzen, Citation2005). Depending on the evaluation outcome and the strength of the beliefs, the person will form a positive or negative attitude toward the behaviour (Ajzen, Citation2005).

Figure 1. Graphic representation of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (simplified from Ajzen, Citationn.d.).

Subjective norm comes from a person’s normative beliefs, which can be understood as the social pressure from the person’s important others or referents (Ajzen, Citation2005). Specifically, normative beliefs are the person’s view of how much support they would receive from their referents to perform the behaviour, and the individual’s views of whether these important others would engage in the desired behaviour (Ajzen, Citation2005). It is assumed that the person will have a supportive subjective norm to motivate their execution of certain behaviour if they are strongly driven by their important referents (Ajzen, Citation2020).

Perceived behavioural control, which is similar to Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy, is dependent on a person’s control beliefs. Control beliefs are the person’s subjective evaluation on the existence of facilitators or hinderances for them to perform a particular behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). It is considered that the person has a higher level of perceived behavioural control if they believe they have adequate facilitators (e.g., the necessary resources, knowledge and skills, and cooperation by others) and fewer obstacles in executing the particular behaviour (Ajzen, Citation2005).

Rationale and significance

According to Ajzen (Citation2020), people’s accessible behavioural, normative, and control beliefs vary according to the behaviour, population, and time period in question; therefore, these beliefs need to be elicited anew for a new behaviour and/or a new research population to ensure the instrument developed is closely aligned to the Theory (Ajzen, Citation2020). This necessitates a distinct research stage called an ‘elicitation study’. After an extensive search of the TPB literature on inclusive education by the first author, it appeared that only Jeong and Block (Citation2011) claimed to have adopted a qualitative survey with nine open-ended questions to elicit physical educators’ beliefs of inclusive education. Instead of adhering to the theoretical intent to conduct an elicitation study to identify teachers’ salient beliefs, almost all studies identified in Opoku et al. (Citation2021)’s scoping review of TPB inclusive education studies ‘imported’ beliefs and/or instruments from previous inclusive education studies. Similarly, Emmers et al.’s (Citation2020) TPB study of Belgian higher education teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy of inclusive education also did not include an elicitation stage but imported two commonly used scales to measure the constructs of the TPB. While doing so is less time-consuming (Curtis et al., Citation2010), the explanatory power of the TPB is extremely likely to be compromised because the imported beliefs may be irrelevant to the behaviour, population, and time period (Downs & Hausenblas, Citation2005). The primary aim of this paper, therefore, is to report the process and results of an elicitation study conducted to develop a data collection instrument for further research that aims to identify Australian university pathway teachers’ intention and practices of inclusive education using Ajzen’s (Citation1991) Theory of Planned Behaviour.

To date, there is no published TPB elicitation study related to the inclusive education in school settings, let alone the higher, university pathway education setting. While this study primarily focuses on Australian university pathway settings, it is of relevance to an international audience for two reasons. First, this study adds knowledge to the wider university pathway setting as the Australian university pathway model has strongly influenced the partner and feeder colleges in the UK and two-year community colleges in the US (Agosti & Bernat, Citation2018; Bode, Citation2013). Second, the TPB has been used by researchers around the globe as the theoretical framework in understanding teachers’ inclusive behaviour, but no study has reported the elicitation of teachers’ behavioural, normative, and control beliefs. Hence, by asking the research question ‘What are UPTs’ behavioural, normative and control beliefs on the inclusion of students with disabilities in their classes?’, this elicitation study is not only significant in adding to the growing body of knowledge of the TPB elicitation studies, but also in understanding teachers’ beliefs of inclusive education in higher education, particularly in the university pathway settings.

Methodology

Methods and instrument

Typically, TPB elicitation studies are to be conducted ‘individually in a free-response format’ (Ajzen, Citationn.d., para. 3) and thus semi-structured interviews were adopted in this study to elicit UPTs beliefs. To develop the interview schedule, the population (i.e., UPTs from New South Wales) was first identified, and the behaviour of interest was defined using the TACT principle: target, action, context, and time (Cooper et al., Citation2016; Francis et al., Citation2004; Giles et al., Citation2007; Tsiantou et al., Citation2013). For the present study, the behaviour of interest is the inclusion of students with disabilities: the target is student with disabilities, the action is including (students with disabilities), and the (implicit) context and time are referred to the UPT’s own university pathway teaching and learning settings. After that, six interview questions () were specifically written to elicit the UPTs’ behavioural, normative, and control beliefs including students with disabilities, following the guidelines of Ajzen (Citationn.d.) and Francis et al. (Citation2004).

Table 1. Interview schedule (extracted).

Sampling, participants, and data collection

After ethics approval was granted by The University of Sydney's Human Research Ethics Committee [2021/250], purposive, typical sampling was adopted. Emails containing the invitation to participate in the study and the Participant Information Statement were sent to five university pathway programs leaders in New South Wales identified from open sources such as the college’s websites and Linkedin.

Eleven UPTs expressed their interest to participate in the interviews. Ten UPTs, four females and six males were interviewed on Zoom individually at a mutually convenient time with the first author. To minimise the interviewers’ influence on the frequency of mentions of a particular belief elicited from an interviewee, the interviewer adopted active silence, and minimum probing (e.g., what is another advantage of … , or what is another factor that would make it harder for you to …) was used to elicit a different belief item rather than exploring the belief owing to the interest of the respondents. The interviews lasted between 23 minutes and 56 minutes; and were automatically recorded and transcribed by Zoom. The eleventh teacher was not interviewed because data analysis of the first ten interviews was completed, and data saturation was achieved with no new, substantial information being identified after interviewing the ninth and tenth participants (Faulkner & Trotter, Citation2017). As shown in , the teachers came from a range of teaching areas and pathway providers, and they have differing years of teaching experience in university pathway education.

Table 2. Participants’ personal and professional details.

Data analysis: Identifying the salient beliefs

University Pathway Teachers (UPTs) can hold many differing beliefs towards the inclusion of students with disabilities, but not all beliefs are influential. Only those that are readily accessible and frequently mentioned are considered salient enough in influencing their intentions and behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980). To identify UPTs’ salient beliefs, which will form the basis of a questionnaire for a larger scale survey, a content analysis was conducted to analyse the interviews (Francis et al., Citation2004).

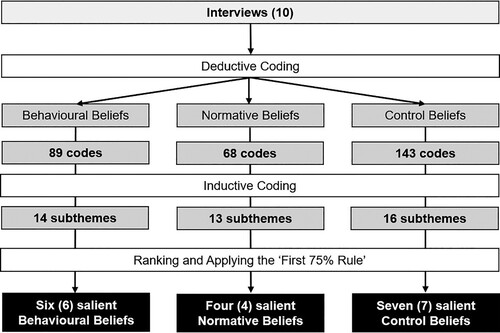

Specifically, a directed content analysis approach was adopted using the three belief categories (behavioural, normative and control beliefs) as initial coding themes (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The content analysis approach partly followed the processes of a ‘theory-driven’ thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). In the first reading, the first author read the participants’ interview transcripts thoroughly while he was listening to the audio recordings to correct the mistakes made by the automatic transcription of Zoom. At the same time, he was able to gain an overall impression of the respondents’ responses. Then, the transcripts were imported to NVivo for coding. As shown in , the data were first deductively coded into the three predetermined themes. After that, the items in each theme were inductively coded and categorised into the subthemes. Diverting from a thematic analysis, these subthemes were then ranked according to their frequencies, from most frequently mentioned to least frequently mentioned (Francis et al., Citation2004). The cumulative frequency and cumulative percentage were also calculated and recorded during the ranking process. Finally, following the established guidelines of Ajzen and Fishbein (Citation1980) and Francis et al. (Citation2004), subthemes that accounted for the first 75% of all beliefs under each theme were identified as the salient behavioural, normative and control beliefs.

For example, a total of 89 behavioural belief items were elicited from the 10 interviews, and these 89 items were coded into 14 subthemes. They were then ordered based on their frequency. Since the first six subthemes accounted for the first 75% of all behavioural beliefs elicited, they are identified as salient behavioural beliefs that may influence UPTs’ attitudes about the inclusion of students with disabilities. For the construction of the TPB Questionnaire, these six beliefs will be turned into a statement accompanied by a 7-point bipolar scale (see Ajzen, Citationn.d., pp. 6–7 for examples).

Limitations of the study

The process of data analysis can be considered as reliable and robust as the authors adhered to the processes from Ajzen (Citationn.d.), Ajzen and Fishbein (Citation1980) and Francis et al. (Citation2004). The results of the data analysis were also member-checked by UPT2, UPT7, and UPT10, and reviewed by the second and third authors. We acknowledge, however, the results are indicative and not confirmatory. Thus, the results presented in the following section should be interpreted with caution, and more importantly with the understanding that it is a small-scale TPB elicitation study.

Results

Behavioural beliefs

Behavioural beliefs are the subjective evaluation of the outcomes of the behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991; Ajzen, Citation2005), in this case including students with disabilities in a mainstream university pathway classroom. Six belief subthemes, five positive and one negative, accounted for 75% of all the behavioural beliefs elicited (see ), and they were identified as UPTs’ salient behavioural beliefs. The finding shows that UPTs showed more favourable outcome evaluation of the inclusion of students with disabilities in mainstream university pathway settings.

Table 3. Salient behavioural beliefs (# denotes a negative belief).

The most cited positive outcome (17 mentions) was the positive feeling and/or experience, such as job satisfaction, that UPTs may gain from the inclusion of students with disabilities. For example:

[It’s] the vicariousness of success when they [students with disabilities] can achieve and they do get to university and they are able to, it’s a wonderful feeling. (UPT6)

They [students with disabilities] always come back … say ‘oh, because of you’, ‘we know what you’ve done for us’, or buy you a present … and I think that is reward in itself. (UPT10)

Probably time and workload is the biggest issue when there needs to be changes to things or lots of personalisation done. Obviously, we have busy schedules … it takes time, and that time is often sometimes hard to come by. (UPT3)

Well … burden’s probably not the right word but it’s extra work in the sense that you might have to prepare different materials, might have to scaffold things to the student that you would not normally need to … so there is often extra thinking and extra work to prepare for each lesson. (UPT8)

I want those students who have a disability to have the opportunity to enter into the professions … not to be disadvantaged because of their disability. (UPT2)

All students have a disability, everyone has a disability, some are just more obvious than others, and so it’s … it’s a case of working through so that they can achieve whatever goal that happens to be [accessing university education]. (UPT6)

The main advantage is to their peers [without disabilities] because it gets them exposed to a greater range of people. It builds empathy and understanding … (UPT3)

It mostly would be beneficial for all of us [including students without disabilities] to just see what it’s like, that life is not the same for every single individual and we could learn from those who haven’t got the same physical abilities or mental abilities that we do. (UPT8)

If you have a disability and you're coming to class you don’t want to be feeling like you’re … you’re different to anyone else … you want your work to be based on your ability and not based on you know, whatever impairment that others may see that you have … That also comes back down to being valued and appreciated for the work that you have done and … You might be more motivated, you know you might be more open to try new things and … and motivated to push yourself more and do more. (UPT1)

You know, everyone is able to achieve in their own way, no matter what their abilities or disability is, and that they should all be considered to be a value as well … For the students with disabilities, I hope for the student, who would be part of it, to … to … to feel like they can do it as well. They are … you know part of a greater thing, yeah. (UPT7)

If you are not inclusive, you’re basically … um … picking a portion of society and in some ways … you’re kind of locking them out. Also, education, particularly in a first world environment, is a kind of a fundamental human right. So, you said to me, why should we give someone with a disability their basic human right, that shouldn’t be a question … you know what I mean? That [inclusive education] is just something we do because that’s a fundamental human right. It’s like having wheelchair ramps in place because it is not really fair as a society to basically say to one group of people you can’t go to these places. It is the something essentially so fundamental that it’s basically assumed. (UPT4)

Normative beliefs

Normative beliefs can be understood as the social pressure from the person’s important others or referents (Ajzen, Citation2005). Four groups of people or important others accounted for the first 75% of all normative beliefs elicited, and they are identified as UPTs’ salient normative beliefs (i.e., important referents) when it comes to including students with disabilities (see ).

Table 4. Salient normative beliefs (# denotes a negative belief).

Cited by all participants with 20 mentions in total, college and/or university leaders were considered as one of the most influential referent groups that would support their inclusion of students with disabilities:

The pathway program coordinators and the course coordinators would certainly be supportive. (UTP2)

The managers, head of departments and the Dean always encouraged helping those students [with disabilities]. (UTP10)

My colleagues would [be supportive] … (UPT5)

I believe a lot of my colleagues, they wouldn’t mind to … to include some of those disability students … into their classes. (UPT9)

We have Access and Inclusion Officers. Of course, they would be supportive [of the inclusion of students with disabilities]. (UPT2)

There’s the Study Success Advisors, probably the most obvious person because you know they’re looking out for the welfare of the students … they’re probably the ones that I guess are the spearhead of the student support and trying to get inclusive educational practices in. (UPT4)

You might get other students, who might … put that student with a disability down because they might see that person as bringing the whole class down or making the class slower, for the rest of the class. (UPT1)

Some students [without disabilities] may feel that ‘why should these people [students with disabilities] … , be given more time [for assessments and examinations]?’. (UPT10)

Control beliefs

Control beliefs are the person’s subjective evaluation on the existence of facilitators or barriers for them to perform the behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). As shown in , five facilitating circumstances and two hindering circumstances accounted for the first 75% of all elicited control beliefs and they are identified as the salient control beliefs held by UPTs on the inclusion of students with disabilities.

Table 5. Salient control beliefs (# denotes a negative belief).

In-service training and/or professional development (23 mentions) was mostly cited as a facilitator to the inclusion of students with disabilities by UPTs. For example:

Ah, what would make it easier [for me to include students with disabilities] … probably … [in-service] training … (UPT3)

Many staff feel overwhelmed anyway, and they are not prepared to have to put themselves out, they will also say they haven’t had any particular training on this [inclusion of students with disabilities] … So, they … they don’t feel that they should be expected to accommodate disabled students. (UPT6)

We may sometimes get information from the Welfare Office … like student management system notes, but not very often … Honestly, they [students with disabilities] just turned up in your class and you have no warning at all. (UPT6)

The hard thing for me, would be to navigate how to help this student because of the lack of information. There needs to be a sense of everyone being on the same page … to make sure that everyone knows about it [when there are students with disabilities]. (UPT7)

Our college do have a Study Success Advisor. If they [students with disabilities] are having … any sort of issues that’s affecting our teaching, the Study Success Advisor can sort of give advice on what to … what sorts of adjustments to do. (UTP4)

There can be support teachers that come into the classroom to help support the teacher managing the class and extra special needs, I think when there’s that support, it takes the burden off the teacher to a significant extent … (UTP5)

So, the coursework is already set out, and so we have to follow the curriculum that the University has provided. We are unable to have any kind of flexibility around how the … the curriculum or the teaching course can progress, then this definitely would cause that negative umm … it just wouldn’t work, especially with somebody who does require that extra time and assistance. (UPT1)

The flexibility with … your professional judgement … you should be able to have the flexibility, but at the moment there isn’t. Like the essays, the marks have to be in [by the deadline] … But for those students [students with disabilities], if they need an extension for a week or whatever … They’re [the college is] unwilling to do it … that’s not reasonable, you need [to be flexible] … there needs to be an adjustment. (UTP6)

Another limiting factor is teaching online. It’s more difficult in general … I think that’s a limiting factor for all students but that including, I imagine, students with disabilities. (UPT2)

It’s probably more difficult in a virtual setting, trying to do it [include students with disabilities] through Zoom. I think working in a classroom with those students [students with disabilities] is the preferred model. (UPT5)

Also, [the college] to be able to allocate maybe one-on-one time after or before class depending on whenever the class starts. So that … the student [with disabilities] might have one hour before or after … kind of … a special tutorial … catch up … depending on the students’ needs … (UPT1)

The classes need to be smaller … if you had multiple students with disabilities … it’s so much easier to manage, and you might not need that much more time to adapt to that one student … (UPT7)

The class size is big … probably those [teachers with large class size] … they certainly not be willing to do it [include students with disabilities] … (UPT9)

Discussion

This study is the first TPB elicitation study reporting Australian university pathway teachers’ (UPTs) behavioural, normative and control beliefs to include students with disabilities. According to the behavioural beliefs identified, UPTs held positive evaluations on the outcomes of educating students with disabilities in their classes. For example, the inclusion of students with disabilities would create positive feelings such as job satisfaction for the UPTs themselves, and may improve other students’ acceptance of diversity. On the other hand, the extra time and work involved in differentiating materials and making adjustments for students with disabilities was a major concern for them. It is notable that while ‘equity and human rights of students with disabilities’ was reported as a positive belief, it was only reported by three teachers and barely fell into the first 75% threshold. A possible explanation for this could be that UPTs lack the understanding that inclusion of students with disabilities is a right mandated under the DSE 2005. This is very similar to teachers across the board in the Australian early childhood, school, vocational education, and higher education settings (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2020). As highlighted in the Final Report of the 2020 Review of the Disability Standards for Education 2005 (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2020), ‘many educators and providers have low awareness of their obligations under the Standards [DSE 2005]’ (p. 28) and ‘not all educators understand the connection between their work and a student’s human rights’ (p. 39). This low level of awareness about the rights of students with disabilities and teachers’ legal responsibility to uphold them is one of the contributors to the widening gap between policy and practice of inclusive education (Moriña & Carnerero, Citation2022). Therefore, based on this finding, it is important for UPTs (and their leaders) to access appropriate training on the DSE 2005 to improve their awareness on the inclusion of students with disabilities.

In terms of normative beliefs, college and/or university leaders and colleagues were regarded as supportive referents while students without disabilities were seen as potentially unsupportive of the inclusion of students with disabilities by the UPTs. These corroborate the findings of the international literature in the school level, as reported in Opoku et al.’s (Citation2021) review. Contrary to the findings from the school settings, a unique finding of the present study is that UPTs did not see parents (of students without disabilities) as a salient referent pressuring them not to include students with disabilities. A possible explanation is that the paternalistic model of schools, in which parental involvement is often stronger, is not transferred to higher education where almost all students are adults (Wolanin & Steele, Citation2004).

As for control beliefs, similar to the findings in the school level (Opoku et al., Citation2021), training and/or professional development, flexibility, and human resources were reported to be facilitators of the inclusion of students with disabilities, whereas large class size was seen to be a limiting circumstance for UPTs to do so. A new finding of this study is that online teaching as a response to COVID-19 was reported to be a hindering circumstance for the UTPs in including students with disabilities. This is not surprising because the requirement to teach online due to COVID-19 was novel. Since teaching online can be vastly different from teaching face-to-face (Crouse et al., Citation2018), this finding of the present study points to a need for university pathway providers to better prepare their employees for teaching students, including those with disabilities, online.

Conclusion and implications

Guided by the TPB (Ajzen, Citation1991), this study is the first elicitation study reporting Australian UPTs’ beliefs of inclusive education. Six behavioural beliefs, four normative beliefs and seven control beliefs were elicited as salient beliefs of UPTs regarding including students with disabilities. Since previous studies exploring teachers’ intention to practise inclusive education rarely conducted or reported the elicitation study stage, the study and its findings are of significant theoretical importance for the development of a data collection instrument to be used in the next stage of a research study on UPTs' intention and practice of inclusive education. They are also significant to the growing body of literature of inclusive education in higher education, particularly in the university pathway settings which are under-researched. Finally, the findings of the present study also have practical implications for university pathway providers: they highlight the need for UPTs to better understand the legislative requirements and the rights of students with disabilities, and the need to better support teachers to teach students with disabilities, especially when learning takes place online.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agosti, C. I., & Bernat, E. (2018). University pathway programs: Types, origins, aims and defining traits. In C. I. Agosti & E. Bernat (Eds.), University pathway programs: Local responses within a growing global trend (pp. 3–25). Springer.

- Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2006). Inclusion and the standards agenda: Negotiating policy pressures in England. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 10(4–5), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110500430633

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, personality and behaviour (2nd ed.). Open University Press.

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behaviour: Frequently asked questions. Human Behaviour & Emerging Technologies, 2(Special issue), 1–11.

- Ajzen, I., & Dasgupta, N. (2015). Explicit and implicit beliefs, attitudes, and intentions: The role of conscious and unconscious processes in human behaviour. In P. Haggard & B. Eitam (Eds.), The sense of agency (pp. 115–144). Oxford University Press.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall.

- Ajzen, I. (n.d.). Constructing a theory of planned behaviour questionnaire [PDF document]. Retrieved February 22, 2020 from https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf

- Armstrong, A. C., Armstrong, D., & Spandagou, I. (2010). Inclusive education: Key themes. In A. C. Armstrong, D. Armstrong, & I. Spandagou (Eds.), Inclusive education: International policy & practice (pp. 3–13). SAGE.

- Australian Disability Clearinghouse on Education and Training. (2021, May). Inclusive teaching - Understanding disability - ADCET. https://www.adcet.edu.au/inclusive-teaching/understanding-disability

- Baker, S., Irwin, E., Hamilton, E., & Birman, H. (2022). What do we know about enabling education as an alternative pathway into Australian higher education, and what more do we need to know? A meta-scoping study. Research Papers in Education, 37(3), 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1849369

- Bode, S. (2013). The first year experience in second year: Pathway college versus university direct entry [conference paper]. The 24th ISANA International Education Conference, Brisbane, Queensland, 3 to 6 December 2013, http://isana.proceedings.com.au/docs/2013/Bode_Shirley.pdf.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brett, M., & Pitman, T. (2018). Positioning pathways provision within global and national contexts. In C. I. Agosti & E. Bernat (Eds.), University pathway programs: Local responses within a growing global trend (pp. 27–42). Springer.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2020). Final report of the 2020 Review of the Disability Standards for Education 2005. https://www.dese.gov.au/disability-standards-education-2005/resources/final-report-2020-review-disability-standards-education-2005

- Cooper, G., Barkatsas, T., & Strathdee, R. (2016). The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) in educational research using structural equation modelling (SEM). In T. Barkatsas & A. Bertram (Eds.), Global learning in the 21st century (pp. 139–162). Sense Publishers.

- Crouse, T., Rice, M., & Mellard, D. (2018). Learning to serve students with disabilities online: Teachers’ perspectives. Journal of Online Learning Research, 4(2), 123–145.

- Curtis, J., Ham, S. H., & Weiler, B. (2010). Identifying beliefs underlying visitor behaviour: A comparative elicitation study based on the theory of planned behaviour. Annals of Leisure Research, 13(4), 564–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2010.9686865

- Downs, D. S., & Hausenblas, H. A. (2005). Elicitation studies and the theory of planned behavior: A systematic review of exercise beliefs. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 6(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2003.08.001

- Emmers, E., Baeyens, D., & Petry, K. (2020). Attitudes and self-efficacy of teachers towards inclusion in higher education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1628337

- Faulkner, S. L., & Trotter, S. P. (2017). Data saturation. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0060

- Francis, J., Eccles, M. P., Johnston, M., Walker, A. E., Grimshaw, J. M., Foy, R., Kaner, E. F. S., Smith, L., & Bonetti, D. (2004). Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour: A manual for health services researchers. Centre for Health Service Research, University of Newcastle.

- Giles, M., Connor, S., McClenahan, C., Mallett, J., Stewart-Knox, B., & Wright, M. (2007). Measuring young people’s attitudes to breastfeeding using the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Public Health, 29(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdl083

- Heffernan, T. (2022). Forty years of social justice research in Australasia: Examining equity in inequitable settings. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.2011152

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jeong, M., & Block, M. E. (2011). Physical education teachers’ beliefs and intentions toward teaching students with disabilities. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82(2), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2011.10599751

- Kendall, L. (2018). Supporting students with disabilities within a UK university: Lecturer perspectives. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55(6), 694–703.

- Lake, J. H., Fraser, B. J., & Williamson, J. C. (1988). An alternative route to higher education: An evaluation of the senior colleges in Western Australia. Higher Education Research & Development, 7(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436880070104

- Lipka, O., Khouri, M., & Shecter-Lerner, M. (2020). University faculty attitudes and knowledge about learning disabilities. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(5), 982–996. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1695750

- Moriña, A., & Carnerero, F. (2022). Conceptions of disability at education: A systematic review. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 69(3), 1032–1046. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2020.1749239

- Moriña, A., Sandoval, M., & Carnerero, F. (2020). Higher education inclusivity: When the disability enriches the university. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(6), 1202–1216. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1712676

- National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. (2016). Pathways to higher education: The efficacy of enabling and sub-bachelor pathways for disadvantaged students. Curtin University. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Final-Pathways-to-Higher-Education-The-Efficacy-of-Enabling-and-Sub-Bachelor-Pathways-for-Disadvantaged-Students.pdf.

- Opoku, M. P., Cuskelly, M., Pedersen, S. J., & Rayner, C. S. (2021). Applying the theory of planned behaviour in assessments of teachers’ intentions towards practicing inclusive education: A scoping review. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(4), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1779979

- Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

- Pitman, T. (2022). Supporting persons with disabilities to succeed in higher education: Final report. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Curtin University. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Pitman_Curtin_EquityFellowship_FINAL.pdf.

- Spandagou, I. (2020). Inclusive education: Principles and practice. In I. Spandagou, C. Little, D. Evans, & M. L. Bonati (Eds.), Inclusive education in schools and early childhood settings (pp. 35–34). Springer.

- Tsiantou, V., Martinez, L., Basak, O., Moschandreas, J., Samoutis, G., Symvoulakis, E. K., & Lionis, C. (2013). Eliciting general practitioners’ salient beliefs towards prescribing: A qualitative study based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour in Greece. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 38(2), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12037

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2016). Education 2030: Incheon declaration and framework for action toward inclusive and equitable equality education and lifelong learning for all (ED-2016/WS/28). UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656.

- Wolanin, T. R., & Steele, P. E. (2004). Higher education opportunities for students with disabilities: A primer for policymakers. Institute for Higher Education Policy. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED485430.pdf.

- Yan, Z., & Sin, K.-F. (2014). Inclusive education: Teachers’ intentions and behaviour analysed from the viewpoint of the theory of planned behaviour. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(1), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.757811