Abstract

Recently, cities across Europe have experienced rising prices for land, construction and increasing housing costs. The question of how companies providing social housing mediate housing policies in light of increasing market challenges has been widely neglected. The article takes the case of Vienna to explore how limited-profit housing associations – the current main providers of social housing – navigate market changes. Following Bourdieu, the article employs a field approach to map the power relations governing the field of social housing construction and explore their influence on strategies for capital accumulation. Drawing on multiple correspondence analysis and qualitative interviews, the article shows that the city’s introduction of competitive tenders for building plots strengthened cultural and social capital over economic capital within the field. It provides an in-depth analysis of the market effects of housing policy instruments by locating their structuring effects in relational market configurations rather than solely focusing on housing market outcomes.

1. Introduction

During the last decade cities all over Europe have experienced a growing financialization of housing, resulting in rising prices for land, construction and increasing housing costs (Gabor & Kohl, Citation2022). This has put many local governments under pressure to act (Kadi et al., Citation2021). While social housing research tends to focus on the policy level, investigating shifts in the provision and regulation of (social) housing, the question of how the companies providing social housing mediate housing policies in light of increasing market challenges have been widely neglected. The article takes the case of Vienna and explores how the main providers of social housing today – limited-profit housing associations (LPHAs) – are dealing with recent challenges. LPHAs access land and financing for new construction both via the market and the municipality. However, this established structure has been confounded. Current market prices are not compatible with public funding requirements, which limit the eligible costs for land acquisition. Yet, public funding is an indispensable part of LPHAs’ financial resources. At the same time, the scarcity of suitable land for publicly subsidized housing has made more LPHAs dependent on governmental land distribution policies. Before the 1990s, land was distributed according to political affiliations and size of associations. In 1995, the city introduced a competitive tenure procedure (Bauträgerwettbewerb, eng. ‘developer competition, DC’) with the aim of objectifying the distribution, as well as to increase the quality of buildings (Amann, Citation1999). Recently, more LPHAs have entered DCs to compete for land and funding, which, as a result, diminishes their individual chances of success.

Contrary to other European cities, investors only more recently discovered Vienna, resulting in a boom in construction, driving prices for land, construction, and housing upward. Therefore, it is a prime example to explore how the city, known for its ‘far-reaching state interventions’ (Kadi et al., Citation2021, 2) in housing and success in providing affordable housing to large parts of the population (Amann & Mundt, Citation2005), shapes market configurations and outcomes via its policy instruments. Due to its unique housing regime Vienna seems a promising case for studying the entanglement of private markets, social housing construction and local government actions (Marquardt & Glaser, Citation2020).

Housing in Vienna, especially its system of social housing, has been subject to extensive research. Studies have dealt with housing policies (Kadi et al., Citation2021), the institutional framework (Lévy-Vroelant & Reinprecht, Citation2014) or housing conditions (Kadi, Citation2015). These approaches, however, tend to generalize about the social housing sector and fail to address power relations between different agents involved. More specifically, current debates lack a nuanced picture of the companies responsible for producing social housing and the different strategies they apply in navigating recent market challenges and policy reforms. Against this background, the paper applies a field perspective (Bourdieu, Citation2005) to grasp the relational configurations of LPHAs and how they deal with increasing competition in the access for land. We seek to demonstrate the relevance of DCs (and therefore the importance of the city government) in structuring the logic of the field, the relations of actors and the prevalent capital forms. Employing a mixed-methods approach, which combines multiple correspondence analysis with qualitative interviews the paper examines a) the dominant capital forms that govern the field of social housing construction and how they are distributed within the field. It then explores b) how strategies for dealing with increasing competition and scarcity of land are structured by respective field position. This approach allows us to discover the power relations structuring the market and explain differing strategies regarding capital accumulation.

The article first gives a brief overview of the main characteristics of the social housing market in Vienna (2) and then depicts the concept of field analysis and its relevance for analyzing markets (3). After laying out the methodological aspects of the study (4), the paper presents four distinct field positions as defined by the relative weight of economic, cultural, and social capital and related strategies (5). Concluding with an overall discussion of the findings (6), the article highlights that power relations between market actors depend not only on financial assets, but also on innovative cultural capital, which is enforced by the introduction of DCs. In this regard, the study makes an important contribution to existing research on social housing as it advances our understanding of market configurations and the way these are shaped by (local) state intervention.

2. Social Rental Housing Market in Vienna

Vienna has a long history of affordable housing policies dating back to the 1920s when the ruling Socialist Party launched extensive housing programs, providing large parts of the working population with affordable and quality housing. Up to this day, the provision of affordable housing is a key agenda of the city (STEP 2025, 2025, Citation2014). Following Kemeny’s differentiation of social housing systems, Austria can be characterized as having a unitary market (Kemeny et al., Citation2001; Mundt & Amann, Citation2010). Contrary to ‘dual rental markets,’ where a sealed-off social housing sector targets only low-income households, in unitary rental markets, the non-profit rental sector is in direct competition with the private rental market. In Austria, the social housing sector plays a crucial role in the provision of overall housing. The social rental market comprises two segments: a) municipal rental housing (Gemeindewohnungen) and b) limited-profit rental housing managed by so-called limited-profit housing associations (LPHAs, Gemeinnützige Wohnbauträger) (Mundt, Citation2018).Footnote1 High income limits make almost 80 percent of the population eligible for limited-profit housing (Tsenkova, Citation2014). Since the city has refrained from further construction activity in 2004, the construction of social housing is predominantly left to LPHAs.Footnote2 This development significantly restructured the relationship between those two segments. The share of municipal housing decreased by 5.4 percent between 1991 and 2018 (from 37.4 to 29.0 percent), whereas LPHAs gained ground and increased their stock by 9.3 percent (from 16.2 to 27.8 percent) (Litschauer & Friesenecker, Citation2021).

LPHAs are special organizational and legal constructs regulated by the Limited-Profit Housing Act (WGG). The majority of the currently registered LPHAs in Vienna were founded in the interwar period (33%) or shortly after the Second World War (55%). However, they differ substantially regarding their forms of organization, resources, and market activity (see Appendix 1). Following Mundt and Amann (Citation2010, 38), key characteristics are: first, the audit through an umbrella organization and supervision through local governments. Second, the cost coverage principle, which means that rents (and selling prices) cover only incurred construction and land acquisition costs.Footnote3 In combination with rent caps set by subsidy schemes, this guarantees lower rents compared to the private housing market. The third characteristic is a clearly demarcated business area limited to housing construction and related activities. The fourth is an obligation to build. Fifth, revenues and profits must be reinvested in purchasing land or construction and refurbishment activity, and distribution of annual surplus to shareholders or owners cannot succeed 3.5% of companies’ capital stock.

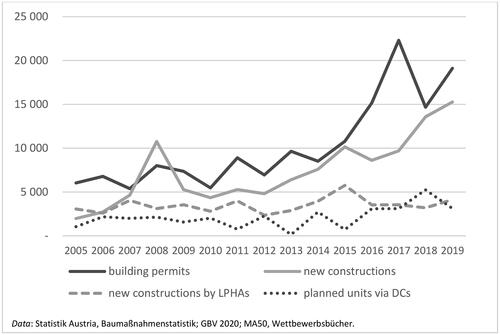

LPHAs access land and financial capital for new constructions either via the market or via the municipality. The city of Vienna predominantly supports social housing via ‘object-side subsidies’ (Amann & Mundt, Citation2005), which means that it subsidizes the construction side of housing by providing land and public loans with low interest. In this regard, the municipality and LPHAs form a symbiotic relationship. LPHAs have access to secure financing, which makes them less dependent on the volatile capital market and equity reserves. Although subsidies do not cover all costs, for most LPHAs they are an indispensable part of financing.Footnote4 The city, on the other hand, can thus provide its population with affordable housing as public subsidies ensure a steady level of construction. Concurrently, it can also shape housing production through regulations attached to these subsidies. For instance by limiting the price for which land can be purchased (currently 188 Euro/m2 of gross overground floor area). Rocketing prices for building plots have made it difficult to find suitable offers on the private market. Since 2015, average costs for building plots have increased from 608€to 912€per m2 in Vienna (Statistik Austria, Citation2019).Footnote5 Moreover, competition from the profit sector has increased more recently. Before 2010, commercial developers only played a marginal role, leaving LPHAs as the main developers in Vienna. Since then, they expanded their construction volume significantly and became a serious competitor for building plots (see ), hence, increasing prices and further intensifying land scarcity.

Figure 1. Housing construction in Vienna, 2005–2019.

Data: Statistik Austria, Baumaßnahmenstatistik; GBV 2020; MA50, Wettbewerbsbücher.

Under current circumstances, LPHAs cannot acquire building plots in the market if they want to take advantage of housing subsidies. Unless they own land (re-)dedicated for construction, the only possibility to gain access to construction opportunities is via so-called ‘developer competitions’ (DC). These tenders are organized by wohnfonds_wien [Housing Fund Vienna], which buys and develops land that is later sold or leased to developers for the construction of (social) housing.Footnote6 DCs were introduced in 1995 as a tool to secure the provision of high-quality subsidized housing whilst ensuring affordability for residents. Both LPHAs and commercial developers can compete for building plots owned by the city of Vienna or private landlords that are reserved for subsidized housing. However, LPHAs account for three quarters of all participants. Competitors submit housing projects which are then assessed by a multi-disciplinary jury. The projects that meet requirements regarding economy, architecture, ecology, and social sustainability the best are awarded with building plots at a fixed price and housing subsidies. Approximately 3,000 housing units are awarded via this DC instrument every year.Footnote7

3. Picturing the Social Housing Market as Field

Housing is a rather complex social phenomenon and has therefore been addressed in multidisciplinary fields (Aalbers, Citation2018; Clapham, Citation2018; Ruonavaara, Citation2018). It has been on the agenda of economists and more recently also claimed as an important part of the political economy, addressing the relevance of housing for capital accumulation (Aalbers & Christophers, Citation2014). Moreover, there is a large field of social policy analysis, dealing with housing governance arrangements or policy interventions on housing processes and outcomes (Kemeny, Citation2006; Whitehead, Citation2020). This paper employs a field approach to examine the social housing market in Vienna. With its focus on objective power relations between (market) actors, field theory provides a useful tool to view housing-as-practice and thereby integrate the research views of housing-as-market and housing-as-policy. Picturing (specific) markets as social fields is well established in current debates of economic sociology ( Schmidt-Wellenburg and Lebaron, Citation2018; Beckert, Citation2010; Swartz, Citation2019 ). However, the field approach has not been widely applied for studying (social) housing construction so far.Footnote8

The field perspective was introduced by Bourdieu, who developed a specific understanding of the social world as a ‘multi-dimensional space of positions’ (Bourdieu, Citation1985, 724), where agents are distributed according to the overall possession and configuration of economic, cultural, social and symbolic capital. Fields are therefore ‘structured spaces of dominant and subordinate positions based on types and amounts of capital’ (Swartz, Citation1997, 122). Within the field, agents do not only compete over access to capital but also over legitimate meanings which structure agents’ perception of themselves and others (Bourdieu, Citation2005; Diaz-Bone, Citation2012). The strategies agents develop and apply in these competitive struggles – and the constraints and possibilities they face – are connected to their position within the field. Thus, we can observe a certain homology between field positions and ‘position-takings’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, 99). As Bourdieu has shown in his study on the field of housing production (2005) or the field of publishers (2008), dominant agents try to influence ‘the rules of the game’ (Bourdieu, Citation2005, 195) in a way that secures their capital stock and reproduces their field position. Dominated agents, on the other hand, either accept the state of capital distribution or actively challenge dominant actors.

The market of social housing producers is characterized by idiosyncrasies that create a unique logic of practices and meanings – the doxa of the field – which marks it as ‘relatively autonomous social microcosms’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, 97) that can be described as field. First, it is subject to a specific set of legal regulations that structure the conditions for capital accumulation (e.g. cost-coverage-principle, restriction on the appropriation of profits), internal organization of companies (e.g. external supervision of business activities) but also construction (if LPHAs make use of building subsidies). Moreover, agents in the field share a specific morality related to their purpose of providing (affordable) housing for broad parts of the population and in that being an important supplement to the (private) housing market. LPHAs share a resentment towards commercial providers that use housing primarily as means for speculation and increasing profits (GBV, Citation2016). This morality is inscribed into what might be called LPHAs organizational habitus.

The strength of a field approach is its relational perspective that enables researchers ‘to seek out underlying and invisible relations that shape action’ (Swartz, Citation1997, 197). Rather than solely focusing on existing social networks, the concept of fields enables us to discover objective power relations as well as ‘potential (material and symbolic) conflicts’ governing the field (Lebaron, Citation2018, 293). Moreover, the ‘surplus’ of field theory lies in its ability to explore the interrelationship of different social forces that shape economic practices such as ‘social networks, institutions and cognitive frames’ (Beckert, Citation2010, 605). In the following section we will elaborate how policy instruments shape relevant resources in social housing construction in Vienna and investigate how capital is distributed among market actors. Different market positions are identified and relate to specific company strategies. In doing so we can give a nuanced account of how housing policies shape underlying power relations and related accumulation strategies.

4. Methodology

To map the field of social housing construction in Vienna, a mixed-method approach was applied, combining multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) with qualitative interviews. Similar to Bourdieu’s study of the French publishing field (2008), we used interviews for selection of variables as well as interpretation of MCA results. The quantitative sample consisted of 45 out of 60 limited-profit housing associations based in Vienna. We excluded LPHAs that neither constructed housing in the past few years, nor participated in DCs and those, who only provide allotment gardening or student residences. A data set was collected from various sources, which included fiscal and organizational information on the companies as well as information on DCs (for details see Appendix 1). Additionally, semi-structured interviews with representatives of 15 LPHAs were carried out between 2020 and 2021 using video conferencing platforms due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The interviews covered issues such as recent challenges, municipal policies, DCs, organizational structure and practices in housing construction. We used thematic coding as suggested by Uwe Flick (Citation2014) which combines elements of thematic analysis and grounded theory. It was developed for comparing perspectives on a social phenomenon and proved suitable for the objective of this study (ibid, 423ff.).

Our analysis followed the steps outlined by Bourdieu (Citation2005, Citation2008), which have also been laid out in greater detail by Diaz-Bone (Citation2012, 107). First, we selected indicators that captured the structure of power relations within the field. Building on Bourdieu’s understanding, that relevant forms of capital in the field under study must be developed empirically, the analysis of the interviews and an in-depth analysis of the industry guided the selection of variables. Since (social) housing construction requires not only economic capital, but also knowhow (cultural capital) as well as collaborations (social capital), it seemed necessary to operationalize all these different aspects of housing construction. Thereby a purely economic perspective can be counter-balanced and the role of the (local) state in shaping the social housing construction market via DCs can be considered explicitly. We identified three aspects of social housing construction: (1) housing market, (2) DCs, and (3) LPHAs-status. Under each heading we subsumed different variables, with a total of 10 active variables. With the variables of ‘housing stock’, ‘undeveloped property’ and ‘new constructions’, the first heading covers relevant resources in housing construction. The second grouping takes into account the policy instrument of DCs and includes ‘participations’, ‘wins’, ‘success rate’, and ‘awards’. Finally, the third group captures the peculiarities of social housing in Vienna including ‘legal status’, ‘activity’ and ‘control’. In total, these active variables depict relevant assets (economic, cultural, social, and symbolic capital) in the field. In addition to active variables, supplementary variables were included (see Appendices 2 and 3 for details).

In the second step, MCA was applied, which makes the dominant power structures within the field visible by exploring the ‘inter-relations between many variables and categories in a data table and, simultaneously, reveal the proximities and distances between statistical individuals’ (Schmidt-Wellenburg and Lebaron, Citation2018, 26). We used a ‘specific MCA’, which allows to treat some modalities of active variables as passive modalities of active questions without destroying the symmetry properties of the method (Blasius & Schmitz, Citation2014; Le Roux & Rouanet, Citation2010). This allows ignoring these modalities for the determination of distances and preserves the properties of MCA. The passive modalities include ‘no participation’ in the variables of ‘wins’ and ‘success rate’, and the modality of ‘no wins’ in the variable of ‘awards’. For all analyses, we applied the R package soc.mca. Based on the 10 active variables and the 45 cases, the results of the specific MCA were produced (for the numeric results, see Appendix 3).

The third step encompassed the interpretation and analysis of these finding by identifying field positions, which was supplemented by qualitative interviews to enhance data richness and improve validity. Fourth, the field structure was interpreted considering emerging challenges of land scarcity that lead to new field dynamics and make the adaption of strategies for land acquisition necessary. The next section outlines the main findings.

5. The Field of Social Housing Construction in Vienna

To discern market configurations of social housing construction in Vienna and to understand how housing policies and DCs in particular shape strategies of LPHAs, the relevant assets and their distribution were examined. We first elaborate how different forms of capital are distributed among LPHAs, and thereby structure the field of social housing construction based on results of the MCA. We subsequently identify separate field positions and discuss related strategies of capital accumulation drawing on data from the interviews.

5.1. Dominant Capital Forms

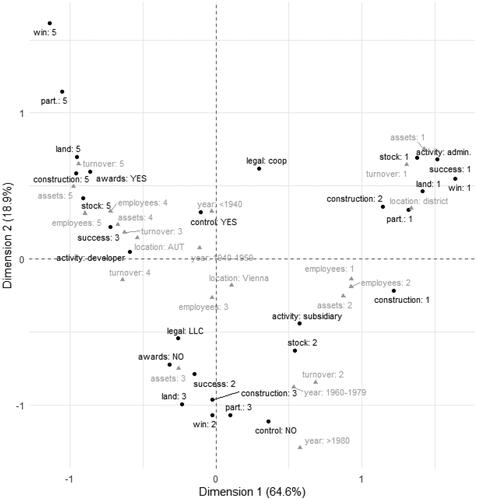

visualizes the MCA results, showing the distribution of modalities of active variables with a high contribution (as black dots) and allows to interpret how resources are distributed within the field of social housing construction (for numeric results, see Appendix 3). In addition, supplementary variables (grey triangles) are included to strengthen the interpretation of field positions although they do not contribute to the structure of the field.

Figure 2. Attributes structuring the field of social housing construction.

Note: Only modalities of active variables with a high contribution are displayed. Active variables as a black dot, supplementary variables as a grey triangle.

The field is predominantly structured along axis 1, which captures 64.6% of total variance, while axis 2 accounts for 18.9%.Footnote9 Hence, the first dimension accounts for most of the variation between LPHAs. In more detail, modalities of variables that represent the extremes have an above-average contribution on the first axis, with the ones indicating low capital (1) located on the right, and modalities indicating high capital (5) on the left (). The first dimension can be interpreted as depicting the volume of capital, and therefore indicates that the field is predominantly structured along size. The second dimension mainly separates attributes reflecting a medium size (on the lower end) from those reflecting high amounts (upper end of the plane). Moreover, the variables of ‘legal status’ and ‘control’ contribute highly to axis 2. While the former separates cooperatives on the top from limited liability companies at the bottom, the latter separates independent companies at the top from ones owned by other LPHAs at the bottom. This can be interpreted as reflecting the relative importance of corporate networks, or social capital, at the bottom of the plane.

Despite these features, the graph shows an arch (or Guttman) effect for most variables, where modalities are perfectly sequenced and many have a linear relationship. Although it could be argued that axis 2 is therefore an artefact, we follow Hjellbrekke (Citation2019) in arguing that this still is a substantial insight, as it shows that different forms of capital have a similar pattern. However, he recommends focusing on the ‘global plane, and not the individual axes’ when interpreting results (Hjellbrekke, Citation2019, 96). The fact that there is no apparent opposition between economic and cultural capital indicates that the economic logic that frames the market is structured in a similar way as the artistic logic introduced by the policy instrument of DCs. Following these findings, the next section will analyze the market configuration by interpreting field positions, or relations of power and opposition, in more detail.

5.2. Field Positions and Capital Configurations of LPHAs

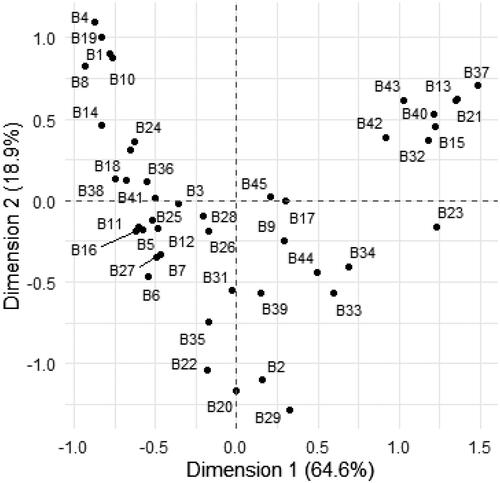

Moving from the space of properties (), that characterizes the overall field structure, to the space of individual LPHAs (), the aim is to identify different field positions (i.e. proximity of companies) by examining which properties they share. Based on principle component analysis is a two dimensional representation of the modalities of individual companies. The distance between individuals in the point cloud is small if they are associated with the same modalities. The similarities and oppositions within the field allow us to detect four field positions and examine what distinguishes the dominant positions from others.

Figure 3. The field of social housing construction in Vienna.

Note: Additionally, interviews were conducted with B1-B15.

On the top right of the graph lie the ‘custodians’, who are deprived of almost all forms of capital, which confines their activities to predominantly managing their existing stock. The overall low volume of capital distinguishes the ‘custodians’ from both big and middle-sized companies. As shows, companies in this group show the lowest level of housing stock, which is also reflected in low turnover rates (supplementary variable). Moreover, this group is associated with having no land reserves (land: 1). Custodians are not only small in economic terms but also in organizational size, as the supplementary variable of employees indicates. Participation in DCs in very low and none of them have been successful (part.: 1; success: 1). Moreover, LPHAs in this group show little to no construction activity. The ‘custodians’ are associated with the legal status of cooperatives, and the supplementary variable suggests that they were founded before WWII. Furthermore, their activity is limited to individual districts in Vienna. Therefore, ‘custodians’ can be characterized as long-established but small companies with hardly any resources, which deprives them of opportunities to change their field position.

In the top left corner, a group of companies stand out from the others. Their dominant position stem not only from economic capital, but more importantly from extensive amounts of cultural capital relevant in DCs (‘innovators’).Footnote10 They are not the biggest LPHAs in the field when it comes to existing housing stock or turnover. However, their extensive amount of cultural and symbolic capital regarding DCs as well as their sufficient supply with economic capital sets the ‘innovators’ apart from others. Although their success rates are comparable to those of others, they exceed all others when it comes to participating and winning in DCs (part.: 5; win: 5). The availability of economic capital allows for the high number of costly submissions. Combined with their ability to innovate housing construction and develop new ideas regarding ecological and social sustainability (see 5.3) this makes them exceptionally successful (which is also reflected in high levels of construction activity). Moreover, they have also attracted much of the field’s symbolic capital, as this field position is associated with the modality of receiving awards. Interestingly, the ‘innovators’ correspond to being organized as cooperatives (dimension 2). The ‘innovators’ can be considered incumbents in the artistic and technical aspects of housing construction as they own skills and expertise linked to the particular format of DC.

LPHAs, who would be considered market leaders in the economic sense, are located slightly below, separate from the innovators (‘enduring big’). This position corresponds to high land reserves and a big housing stock. The same is true for supplementary variables like turnover, and total assets. Moreover, they show high levels of construction activity. In this economic regard, they are better positioned than most of the ‘innovators’. However, they participate less in DCs, which draws them closer to the center of the plane and suggests that they have only accumulated a limited amount of cultural capital relevant to DCs. If the importance of DCs and related capital forms were neglected, these LPHAs would be dominating the field. Their idiosyncratic position in the analysis results from the fact that, in addition to the economic market logic, an artistic logic also characterizes the field of social housing construction, which is strengthened via DCs. Despite their high volume of (economic) capital, their relative lack of cultural capital brings them closer to middle-sized companies in the field. Nevertheless, the ‘enduring big’ can be considered incumbents in the economic logic of the market.

At the bottom of the graph, rest LPHAs with a medium-sized capital stock dominated by social capital (‘collaborators’). This fourth field position is characterized by a small-to-medium housing stock, moderate housing construction performance, and a medium amount of undeveloped land. Regarding cultural capital, there is reasonable involvement in DCs, however, their participation rates are lower than those of the ‘enduring big’. A high relative share of social capital counterbalances the midsize volume of economic and cultural capital: The variables of legal status and activity indicate that LPHAs in this group are either subsidiaries or joint ventures of other LPHAs, or part of a corporate network. As the year of foundation shows, companies have been (re-)established comparably recent. Half of this cluster belongs to one single corporate network, with the parent company being positioned closer to the incumbents in the field. Most companies in this network have no administrative employees but average construction activities (construction:3) and moderate participations in DCs (part: 3), indicating that economic and cultural capital is pooled within the network while LPHAs remain formally independent. Hence, the corporate network allows middle-sized companies to continue their activity despite a lack in economic and cultural capital.

The next section explores how the field position structures LPHAs’ strategies for capital accumulation with regard to gaining access to land and funding in order to continue building activity.

5.3. Capital Accumulation Strategies in Times of Land Scarcity

As outlined above, there are two sources for building plots: the private land market and city-owned land. Regarding the latter, LPHAs must win the competitive tenure procedure of the DC. Regarding the former, rising prices on the private market for building plots pose a problem because making use of public subsidies for construction limits the eligible costs for purchasing land. As current market prices are way beyond this limit, acquisition of suitable land for subsidized social housing has become impossible, as all interviewees agree, ‘to get a plot of land on the free market at the moment, to build purely subsidized, is virtually impossible in Vienna’ (B10). In a similar vein, one interviewee explains, ‘currently we cannot buy a single property in Vienna, which is dedicated at conditions suitable for housing subsidies’ (B8). Another interviewee highlights, ‘land prices are now so high that we can no longer really create non-profit housing, i.e. affordable housing in the sense of the term’ (B3). Depending on the overall position in the field and the respective capital configuration, LPHAs can draw on different strategies to secure further capital accumulation in times of increasing competition and scarcity of land.

Their overall lack in both economic and cultural capital poses obstacles for the ‘custodians’ in gaining access to building plots. First, they are the ones most affected by rising prices on the market because of their limited financial and land resources. Additionally, their deprivation of capital also creates a barrier for entering DCs as prerequisites for participation are rather high. Interviewees estimate overall costs for the preparation of the submission to amount between ‘35.000 and 100.00 Euro’ (B14), which make these tenders a high-risk investment that many of the custodians are not willing or able to take. Additionally, they lack administrative resources but also procedural knowhow, which are a key for success, as different respondents stress. ‘There are no formal entry barriers, but the procedure got so complicated, that you will not be able to win your first time. That’s for sure’ (B5). ‘It is so complicated that it has become almost insider knowledge how to fill in the forms, how to do calculations, […], someone doing this for the first time will despair’ (B8). Moreover, DCs predominantly consist of large development projects, which require considerable organizational capacities (both during construction and afterwards for maintenance and administration) which ‘custodians’ clearly lack. It is because of these exclusionary mechanisms that none of the ‘custodians’ were successful so far. Some custodians address these difficulties by constructing housing projects without public funding on a very small scale from time to time. ‘I have now bought a plot of land, […] and I want to build twenty-seven [privately financed] flats there, with that, I would fulfil my building obligation’ (B13). Others use social capital to become partners of larger LPHAs (B16, B32).

The main strategy for ’innovators’ to get access to land is via DCs. Although their land reserves are comparable to the ‘enduring big,’ they seem to be unable to capitalize on them, which makes winning in a DC vital for maintaining their construction activity. As one respondent emphasizes, ‘we have in the balance sheet, it is not a secret, around forty or fifty million that are stashed away somewhere as land, but that is actually agricultural land’, which is why, ‘90 percent we live on DC’ (B10). ‘Innovators’ have managed to accumulate relevant cultural capital over the past several years, which makes them successful competitors in DCs. This includes formal and informal knowledge regarding the tender procedure (formal cultural capital), the ability to compile a successful team of architects, technicians, sociologists etc. (social capital), as well as the ability to develop innovative ideas regarding (social) sustainability (innovative cultural capital). The latter includes making use of new construction materials, implementing concepts for saving resources during construction, developing shared mobility concepts and fostering social cohesion amongst tenants (e.g. communal areas, participation). Their position is also acknowledged symbolically, as they regularly receive awards by the City of Vienna, which rewards them with a fixed position in one of the DCs. Hence, ‘innovators’ managed to capitalize on the introduction of DCs, which allows them to transform cultural, social, and symbolic capital into economic capital. This enabled some companies to improve their overall field position: ‘Until the 90 s, the company was actually a relatively small, “dozy” company, and the then managing director started to participate in DCs […] We roughly doubled in size during this phase not solely because of the competitions, but to a very large extent. And we went from being a sleepy, insignificant company to one of the most innovative in Vienna’ (B1). However, whereas in the early days competition was limited because only a few LPHAs participated in the tenders, today ‘competition has become fierce’ (B8). High land prices on the private market have driven more LPHAs to entering DCs, increasing the pressure also for ‘innovators’.

On the contrary, the ‘enduring big’ can rely on economic capital that they accumulated over decades of building activity. Their large land reserves make them less affected by current market prices and less dependent on land redistribution by the city. ‘This situation is not new, rising land prices have always existed’ (B11). Furthermore, participating in DCs is seen as more important for adding to the companies’ symbolic capital rather than gaining access to land, as the next quote shows: ‘Thankfully, in sum we are in a position, where this [DC] is not quite so important for us, because we have the opportunity to participate in some development areas in the city, where we foreseeably will generate enough sales. But, I guess, for sure it is also part of the reputation of a developer in Vienna to be visible in the DC’ (B5).

The ‘collaborators’ follow a strategy of transforming social capital into cultural capital, which is necessary for economic capital accumulation. This is accomplished in two distinct ways: First, companies establish long-term connections with other LPHAs either via corporate networks or by becoming their subsidiaries. Resources both for managing existing housing stock as well as developing new construction projects are shared within the network. One respondent who’s company is part of a larger network describes this constellation as ‘management association’, which allows for ‘high efficiency’. Especially when it comes to DCs ‘we don’t have to gather the experience for each company ourselves, but we can gather it from project to project and then use it everywhere’ (B7_2). Subsidiaries that are in effect only managers of existing housing stock have access to new construction and can build on the economic and cultural capital of their parent company. In turn, the parent company can enter DCs more often through these subsidiaries and achieve economies of scale by managing a larger housing stock. ‘So, we jointly agree which company is to be served with a competition, so to speak. And often it is the case that multiple participations are possible’ (B7_1). The second strategy builds on occasional collaborations in DC. ‘These constellations are of course not among strangers. They are people I have known for many years, then we say, well, let’s do something together again. […] I can contribute a lot when it comes to the development and organization of a project, while the partner has a very efficient construction department’ (B2). Social capital in the form of informal contacts is used to gain access to the cultural and economic capital of bigger and more experienced companies and, therefore, allows ‘collaborators’ to maintain a limited building activity.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

The paper set out to explore the power relations governing the field of social housing construction in Vienna and related strategies for capital accumulation. In light of rising prices for building plots on the private market and an increasing competition with private developers, LPHAs face the challenge to acquire land that meets the limits of eligible purchase costs for subsidized social housing construction. Results reveal homologies between field positions and strategies as underlying capital configurations enable or limit companies’ possibilities. This allows us to understand how challenges translate into problems for some actors, while others can strengthen their position. Larger companies with extensive amounts of economic capital draw on their land reserves and are less affected by either market prices or a decreasing probability of success in DCs. However, their lack of experience in DCs could make their position more vulnerable in the future. The ‘innovators’ benefit from the extensive amount of cultural capital they have accumulated over the years, yet, they also have to continuously raise their stakes. Collaborators secure competitiveness predominantly via social capital, however, for some this means losing the status as an independent company. The smaller cooperatives are increasingly excluded from construction as they are deprived of all forms of capital currently necessary to successfully compete for building plots.

The article contributes to current debates in two ways. First, this study makes a valuable contribution to the empirical application of field theory by offering insights into the dynamics between the market and the state when it comes to social housing construction. By elaborating what the key resources or capital forms for social housing construction are and investigating how they are distributed, the findings show that DCs are a highly relevant policy instrument that influences market principles and power configuration. Although economic capital remains the pivotal currency, DCs strengthen capital linked to technological and social innovation as well as social networks in the competition for land and funding. Although we presently see a rather diverse market, our study also suggests that against the backdrop of current developments (scarcity of land, high prices) DCs might contribute to capital concentration within the field in the long run. Smaller companies are increasingly excluded from market participation and are forced to either focus on managing their existing stock (‘custodians’) or become subsidiaries of larger LPHAs (‘collaborators’). To preserve the heterogeneity of the social housing market, the City of Vienna needs to adapt its instruments to give smaller developers the opportunity to continue their construction activities.

Second, the results of the study indicate that field theory is a promising approach for housing studies that should be developed further in future research. As we have shown, it allows for an in-depth analysis of market effects of housing policy instruments by locating them in relational market configurations rather than solely focusing on housing market outcomes. Field theory facilitates the critical analysis of both market actors’ practices and struggles and how these generate particular forms of market configurations that often remain uncontested in current housing research. It enables to explain why and how social housing developers in Vienna provide affordable and innovative high-quality housing. However, the precise mechanisms of the relationship between individual companies and the local government, especially regarding how dominant agents try to exert influence to strengthen their field position, remain to be elucidated and could be usefully explored in further research.

From a housing policy perspective, results point towards increasing difficulties to provide affordable housing in Vienna. Whilst the city’s redistribution of building plots continues to be an important resource for affordable housing, rocketing prices on the private market make it difficult for LPHAs to acquire building plots suitable for subsidized housing. Growing competition and shrieking chances for success in DCs require companies to seek other opportunities to reinvest profits and secure capital accumulation – contributing to an increase in privately financed dwellings. Although the cost-coverage principle applies in both cases, rents are higher in privately financed housing, which deepens concerns about deteriorating housing affordability. The example of Vienna stresses the necessity of considering the interdependence of different (public and private) actors when developing policies targeting the affordability crisis in housing. Additionally, while the importance of public land distribution for the provision of affordable housing is apparent, the study highlights the importance of considering implicit market effects of distributive (housing) policies.

Geolocation Information

The study was conducted in Vienna (Austria).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our colleagues from the research group SPACE (Claudius Gräbner, Stephan Pühringer, Georg Wolfmayr, Ana Rogojanu, Matthias Aistleitner, Susanna Azevedo, Theresa Hager, Raphaela Kohout, Sarah Kumnig, Laura Porak and Johanna Rath) for valuable comments on earlier drafts of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Despite rents being comparable between the two segments, limited-profit housing requires down payments, which are returned to tenants when they move out (deducted by 1 percent per year), posing an access barrier for low-income households.

2 The city recently relaunched its building activities, but only a very limited number of units are built.

3 This also includes management/maintenance costs as well as financing costs (Pittini et al Citation2021).

4 Public loans usually account for one quarter to half of the financing costs (GBV Citation2016, 91).

6 In 2019, wohnfonds_wien owned 3.2 million m2 of land, which amounts to 2.2% of the area dedicated as building land (Gutheil-Knopp-Kirchwald & Getzner, Citation2012).

8 An exception is Metzger’s (Citation2021) analysis of social housing in Hamburg, Germany, which elaborates the structural relationships of social positions in the field of social housing and highlights the relevance of different capital forms for cooperatives in Hamburg.

9 The third dimension only accounts for 6.6%, which means that the multi-dimensional space can be interpreted as a two-dimensional without losing much explanatory strength (82% of total variance).

10 Although innovation does not only grow out of participating in DCs, the term seems suitable for this group since being successful in DCs requires constant innovation regarding architecture, housing techniques, environmental issues, and social aspects.

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2018). What kind of theory for what kind of housing research? Housing, Theory and Society, 35(2), 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2017.1366934

- Aalbers, M. B., & Christophers, B. (2014). Centring housing in political economy. Housing, Theory and Society, 31(4), 373–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2014.947082

- Amann, W. (1999). Kompetenzverlagerungen im Wohnungswesen. Vienna: Forschungsgesellschaft für Wohnen, Bauen und Planen.

- Amann, W., & Mundt, A. (2005). The Austrian system of social housing finance. Working Paper, Institute for Real Estate, Construction and Housing Ltd.

- Beckert, J. (2010). How do fields change? The interrelations of institutions, networks, and cognition in the dynamics of markets. Organization Studies, 31(5), 605–627. ‘ https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840610372184

- Blasius, J., & Schmitz, A. (2014). Empirical construction of bourdieu’s social space. In J. Blasius & M. Greenacre (Ed.), Visualization and verbalization of data (pp. 205–222). CRC Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1985). The social space and the genesis of groups. Theory and Society, 14(6), 723–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00174048

- Bourdieu, P. (2005). The social structures of the economy. Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2008). A conservative revolution in publishing. Translation Studies, 1(2), 123–153. ‘ https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700802113465

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Polity Press.

- Clapham, D. (2018). Housing theory, housing research and housing policy. Housing, Theory and Society, 35(2), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2017.1366937

- Diaz-Bone, R. (2012). Ökonomische Felder und Konventionen. Perspektiven für die transdisziplinäre Analyse der Wirtschaft. In S. Bernhard & C. Schmidt-Wellenburg (Eds.), Feldanalyse als Forschungsprogramm 1 (pp. 99–119). Springer VS.

- Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research (5th ed.). SAGE.

- Gabor, D., & Kohl, S. (2022). ‘My home is an asset class’. The financialization of housing in Europe. http://extranet.greens-efa-service.eu/public/media/file/1/7461

- Gutheil-Knopp-Kirchwald, G., & Getzner, M. (2012). Analyse der Angebots- und Preisentwicklung von Wohnbauland und Zinshäusern in Wien. TU Wien.

- Hjellbrekke, J. (2019). Multiple correspondence analysis for the social sciences. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kadi, J. (2015). Recommodifying housing in formerly “red” Vienna? Housing, Theory and Society, 32(3), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2015.1024885

- Kadi, J., Vollmer, L., & Stein, S. (2021). Post-neoliberal housing policy? Disentangling recent reforms in New York, Berlin and Vienna. European Urban and Regional Studies, 28(4), 353–374. ‘ https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764211003626

- Kemeny, J. (2006). Corporatism and housing regimes. Housing, Theory and Society, 23(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090500375423

- Kemeny, J., Andersen, H. T., Matznetter, W., & Thalman, P. (2001). Non-retrenchment reasons for state withdrawl: developing the social rental market in four countries. Working Paper 40, Institute for Housing and Urban Research.

- Le Roux, B., & Rouanet, H. (2010). Multiple correspondence analysis. SAGE.

- Lebaron, F. (2018). Pierre Bourdieu, geometric data analysis and the analysis of economic spaces and fields. Forum for Social Economics, 47(3–4), 288–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2015.1043928

- Lévy-Vroelant, C., & Reinprecht, C. (2014). Housing the poor in Paris and Vienna: The changing understanding of the ‘social’. In K. Scanlon, C. Whitehead, & M. F. Arrigoitia (Eds.), Social housing in Europe (pp. 297–313). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Litschauer, K., & Friesenecker, M. (2021). Affordable housing for all? Challenging the legacy of Red Vienna. In Y. Kazepov & R. Verwiebe (Eds.) Vienna. Still a just city? (pp. 53–67). Routledge.

- Marquardt, S., & Glaser, D. (2020). How much state and how much market? comparing social housing in Berlin and Vienna. German Politics, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2020.1771696

- Metzger, J. (2021). Genossenschaften und die Wohnungsfrage: Konflikte im Feld der Sozialen Wohnungswirtschaft. Westfälisches Dampfboot.

- Mundt, A. (2018). Privileged but challenged: The state of social housing in Austria in 2018. Critical Housing Analysis, 5(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2018.5.1.408

- Mundt, A., & Amann, W. (2010). Indicators of an integrated rental market in Austria. Housing Finance International, 35–44.

- Österreichischer Verband gemeinnützig Bauvereinigungen (2016). (ed) 70 Jahre Österreichischer Verband Gemeinnütziger Bauvereinigungen Revisionsverband. GBV.

- Pittini, A., Turnbull, D., & Yordanova, D. (2021). Cost-based Social rental housing in Europe. The cases of Austria, Denmark, and Finland. Housing Europe (online report). https://www.housingeurope.eu/resource-1651/cost-based-social-rental-housing-in-europe

- Ruonavaara, H. (2018). Theory of housing, from housing, about housing. Housing, Theory and Society, 35(2), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2017.1347103

- Schmidt-Wellenburg, C., & Lebaron, F. (2018). There is no such thing as “the economy”. economic phenomena analysed from a field-theoretical perspective. Historical Social Research, 43(3), 7–38.

- Statistik Austria. (2019). Wohnen. Zahlen, Daten und Indikatoren der Wohnstatistik. Statistik Austria.

- STEP 2025. (2014). Urban development plan Vienna STEP 2025. Municipal Department 18 (MA 18).

- Swartz, D. (1997). Culture & power. The sociology of Pierre Bourdieu. University of Chicago Press.

- Swartz, D. (2019). Bourdieu’s concept of field in the Anlgo-Saxon literature. In J. Blasius, F. Lebaron, B. Le Roux, & A. Schmitz (Eds.), Empirical investigations of social space (pp. 177–194). Springer.

- Tsenkova, S. (2014). Krisenfestigkeit der sozialen Wohnungssektoren in Wien und Amsterdam. In W. Amann, H. Pernsteiner, & C. Struber (Eds.), Wohnbau in Österreich in europäischer Perspektive. Festschrift für Prof. Dr. Klaus Lugger für sein Lebenswerk (pp. 95–104). Manz.

- Whitehead, C. (2020). How housing systems are changing and why: A critique of Kemeny’s theory of housing regimes; Mark Stephens: A commentary. Housing, Theory and Society, 37(5), 573–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2020.1816574