Abstract

In this paper the authors suggest that the Global Internal Audit Standards (the IIA’s Standards) issued in January 2024 resemble the placing of old wine in new bottles, insofar as they represent a missed opportunity to truly transform rules-driven Standards into principles-based Standards. This co-authored essay provides two perspectives on the revised Standards: although written independently, and originating from different premises, they both arrive at similar conclusions in favor of principles-based Standards. The authors suggest that the prescriptiveness of the IIA’s Standards continues to petrify individual judgment and critical reasoning, narrowing intellectual and moral horizons in modern internal auditing. By following rules, the focus of internal auditors is misguided toward form over substance, encouraging a checklist-based mind-set that diminishes moral agency. The authors therefore advocate principles-based Standards because they tend to encourage the internal auditor to apply abstract concepts to concrete examples. The authors see unexploited potential inherent in the encouragement of individual judgment, especially when entering the pioneering zone of the pragmatic implementation of the IIA’s Standards – a zone characterized by complexity, chaos, ambiguity, and trade-offs, in which internal auditors are compelled to address WHAT IF types of question. Although the two authors converge in their overall conclusion, they offer alternative reasons for their views, and differing (though perhaps not entirely irreconcilable) suggestions for the future. Lenz draws our attention, in our VUCA and BANI world, and in the age of artificial intelligence, to rethink what it means to be human, and to rethink the skills that make internal auditors strong, influential, and effective. He presents the Trust Triangle that places authenticity as an anchor term to the discourse. Effective internal auditors must have strong human skills: he therefore suggests a model with five competence blocks of the most important skills of the effective internal auditor. There is no need for humans who behave like robots. The refined leitmotif of “The Gardener of Governance: Our nature is Nurture” is suggested as purposeful for internal auditing. O’Regan proposes a future focus on the rigorous application of traditional logic to internal auditing. He suggests that such an emphasis on logic might offset the socially-constructed, slippery, and ever-changing knowledge base of internal auditing, thereby facilitating the development of principles-based standard-setting.

INTRODUCTION

We acknowledge the huge effort undertaken by the global standard setter, the IIA Inc. in the United States, in overhauling its 2017 professional Standards. The IIA’s issuance in January 2024 of the IIA’s Standards, which will come into force in January 2025, was part of a broader revamping of the IIA’s International Professional Practices Framework (IPPF), a process referred to as the “IPPF evolution project” (IIA, Citation2024a, p. 6) that began in 2021. At that time, the IPPF included, in addition to the then-in-force International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing, a statement of the core principles of internal auditing; a definition of internal auditing; and a code of ethics. The IIA’s Standards of 2024 are to be combined with Topical Requirements and Global Guidance to form an updated IPPF. The level of transparency and openness in the standard-setting process are perhaps unparalled in the context of professional standard-setting, and the IIA is to be strongly commended for its rigorously transparent consultation process. We applaud the IIA and the many contributing stakeholders, most of them volunteers, for their admirable efforts in undertaking the project.

Prior to the issuance in 2023 of an exposure draft for public comment, the IIA’s IPPF Oversight Council issued a Framework for Setting Internal Audit Standards in the Public Interest (IPPF Oversight Council, Citation2022). This Framework established the parameters and tone for the subsequent work undertaken by the International Internal Audit Standards board (IAASB), the architect of the details of the revised Standards, under the guidance of the IIA and its IPPF Oversight Council. Initial consultations involved significant stakeholders, including large institutions (e.g., the European Commission and the U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board) and the large consulting and advisory firms (in IIA terminology, its “principal partners”). The subsequent period of public consultation, which included a survey in 22 languages (IIA, Citation2024b, p. 9) and invitations for individualized comments, resulted in almost 19,000 comments that required analysis and assessment.

In the words of the IIA’s current President and Chief Executive Officer, the IIA undertook “more than two years of research, outreach, and fine-tuning” after the realization that “our existing Standards, while robust, were struggling to keep pace with the ever-evolving nature of business and the accelerating pace of change” and, moreover, the changes went “beyond mere adaptation – it necessitated a bold and visionary reimagining of the Standards” (Pugliese, Citation2024). Major aspects of the changes have included a transition from “attribute” and “performance” Standards, with 52 of the IIA’s Standards arranged under 15 guiding principles, within five domains (although the first domain consists of only a purpose statement and covers no principles or Standards).

The IIA has emphasized the transparency of the consultation process, issuing on 9 January 2024 a 50-page document, Report on the Standard-setting and Public Comment Processes for the Global Internal Audit Standards (IIA, Citation2024b) alongside the revised Standards themselves. This transparency is a positive thing, and the document explains how the public commentary was addressed, covering matters ranging from the prescriptiveness of some of the IIA’s Standards’ language to performance measures for internal auditing. Nonetheless, the focus of the IIA’s analysis (IIA, Citation2024b) perhaps drifts too far in the direction of the process for revising the IIA’s Standards, to the detriment of the product of the revised Standards. It thereby elevates the means of the Standards-setting process over its ends.

In this paper we seek to foster further discussions in the internal audit profession. We provide two critical perspectives on the revised Standards, both advocating a greater extent of principles in future Standards. Since creating is much harder than judging, we share our suggestions for future directions of the Standards of the internal audit profession. We do not expect everybody to agree with the content of this paper. But we would be delighted for professional peers to read the article and ponder.

In the FIRST section of this article, Lenz identifies three main threads. 1) He starts with a leading question, the overarching theme, which is: What is the role of Internal Auditors in the Corporate Governance Ecosystem? In other words, what is it that Internal Audit (IA) can contribute to prevent governance failure? 2) Since he views the very core of IA as a Human-To-Human business, he suggests strengthening and focusing the human skills of internal auditors as the recommended future path when seeking to heighten the relevance, impact, and the effectiveness of IA. In doing so, he proposes a model of the major traits, the five most important competence blocks of the effective internal auditor, as he views it. In the age of artificial intelligence, Lenz suggests, human beings need to focus on what human beings can do better than robots. Hence, he focuses on the essence of what it means to be human when performing internal auditing work. He introduces authenticity as anchor term to the discourse. 3) He argues that prescriptive guidance and checklists do not help when entering the pioneering zone (Lenz & Hoos, Citation2023). He suggests fundamentally revising the Standards of the IA profession next time round. He argues that de facto principles-based Standards would be the more promising path when seeking to nurture IA as a stronger force in the Corporate Governance Ecosystem.

In the SECOND section of this co-authored essay, O’Regan considers the interpretive challenges and perplexities inherent in all professional Standards. Taking an approach of philosophical hermeneutics, in the tradition of Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Truth and Method (Gadamer, Citation2004), he looks at definitions and understandings of professional Standards, and he investigates the extent to which written Standards might capture social reality in areas like applied knowledge (i.e., expertise) and the promotion of the public good. He suggests that prescriptive Standards, such as the IIA’s Standards, tend to struggle both in capturing expertise and in promoting the public good. He also suggests that the knowledge base of IA is rather slippery, complicating the Standards-setting process, but that this slipperiness can be offset by methodological rigor in the use of traditional logic in IA.

The paper ends with the authors’ shared conclusion that the IIA’s revised Standards are a missed opportunity to truly transform rules-driven into principles-based Standards. Both authors offer remedies, of differing yet perhaps not irreconcilable natures, to the problem.

FIRST SECTION

Onto the FIRST section of this paper. Briefly, Lenz’s three main threads in the first section are:

What is the role of Internal Auditors in the Corporate Governance Ecosystem?

Effective Internal Auditors “must-have” strong human skills, including authenticity

To heighten effectiveness, the professional Standards must become principles-based

First things first. From a meta-perspective I suggest further consideration be given to the role and responsibility of IA in the corporate governance mosaic. As a leading question, I recommend more fully understanding the distinct features, the assets that IA can bring to the table. I am positive that there is plenty of unexploited potential for internal auditors typically on deck all the time - they breath the air of the organization they serve, they know how the company ticks, they know “who is running the firm and how is accountability ensured” (Korine, Citation2020, p. 11),Footnote1 they know how decisions are made. Given the continuing governance failures the different corporate ecosystem actors must question their roles and mode of cooperation.

What is the Role of Internal Auditors in the Corporate Governance Ecosystem?

There is an extensive list of governance failures, mentioning prominent cases like Enron, WorldCom and Lehman Brothers in the USA, Parmalat in Italy or FlowTex and Wirecard in Germany. There are many others. There will be further corporate disasters because of governance failure unless we fundamentally change our governance mosaic.

Accountancy Europe (Citation2023) views collective learning as the most effective means to reinforce the corporate sector’s resilience by mitigating the risk of corporate incidents. The discussion paper proposes, as an example solution, to set up a “Corporate Resilience Network.” I support that endeavor. I focus thereby on the part of IA, also in this paper.

Over 10 years ago, Lenz (Citation2013) stated that “IA has not generally been seen to have a significant role in the financial crisis, neither as part of the problem nor as part of the solution”, and “IA is still searching for an identity and a unique selling proposition (USP) in order to play a more important role in the governance debate.” In 2024, over 10 years later, that observation, that judgment is still valid - unfortunately. For example, Drašček (Citation2024), not yet seeing a convincing purpose of IA asks fundamental questions, including “What is Internal Audit uniquely good at?” and “How does Internal Audit create value?”. The search for identity continues. Time is ripe to change for the better.

I am positive that IA can do better, IA can do more to prevent governance failure. Corporate governance failures typically do not happen from one day to another. Corporate governance failure “develop over time, often over a number of years” (Korine, Citation2020, p. 99). I view internal auditors as potentially highly performant to help preventing governance failure. Internal auditors can be the ones duly listening, with audire (Latin) the name and origin of the profession, asking the right questions in good time, thereby ideally sensing the emerging exposure early while problems are small. Admittedly, there is no absolute guarantee. Never. It is like a garden, “corporate governance is never ‘done’” (Korine, Citation2020, p. 99). “Governance Needs Gardening” (Lenz & Chesshire, Citation2023).

Drašček (Citation2024) as synonym for the void waiting to be filled is in search of the purpose of IA. I have a suggestion. I see value in the mantra, the suggested leitmotif for internal auditors, here refined as “The Gardener of Governance: Our nature is Nurture” (Lenz & Jeppesen, Citation2022).Footnote2 I suggest viewing internal auditors as gardeners, nurturing/strengthening the governance ecosystem, helping to better deal with a complex coordination challenge, be a connector, interpreter, translator, be a hinge, and nurture the foundation of organizations, its mind-set, the ABC of organizational change: Attitude, Behavior, and Culture. I believe that viewing internal auditors as gardeners in the governance ecosystem could be a promising path, deserving further consideration in practice and academic research.

Korine (Citation2020, p. 99) rightfully demands “stakeholders need to have a dynamic view of corporate governance.” I see the future of the IA profession in the “pioneering zone” (Lenz & Hoos, Citation2023), dealing with complex and chaotic subject matters. The VUCAFootnote3 and BANIFootnote4 world we live in is fast-paced and fast-changing. That perspective is shared by PwC’s (Citation2023) global study of IA, also referencing pioneering as the future arena for internal auditors to add value and have influence. I would challenge PwC, though: I do not believe there is such a thing as an “objective viewpoint” (PwC, Citation2023, p. 10). Either it is a viewpoint, hence subjective in nature, or it is objective, “verifiable reality” (O’Regan, Citationforthcoming). It cannot be both. PwC (Citation2023) has a valid point: In the world we live in, it is the pioneering zone that matters. We are all in that pioneering zone now, on unknown, unchartered territory. Hence, in the age of artificial intelligence, Burkhardt (Citation2018, p. 165) rightfully suggests humans to “Shift from Exploiting the Familiar to Exploring the Unknown”.

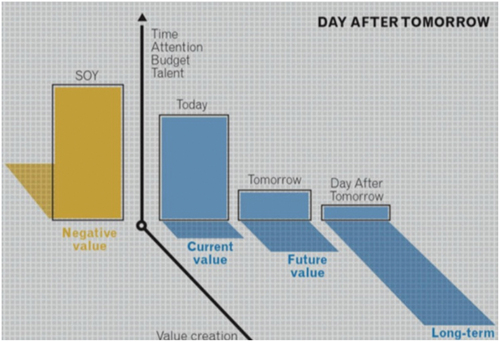

Organizations are often overwhelmed with what Hinssen (Citation2017, p. 58) calls “SOY”,Footnote5 i.e., legacy issues that create negative energy. In such situations, the allocation of resources is misplaced. There is too much emphasis on dealing with the past. Present challenges and future ambitions do not get the attention they deserve. The focus should shift toward the tasks of “Today” and, more importantly, toward the value creation in the future, the “Tomorrow”, the future value, and the “Day After Tomorrow”, the long-term value ().

Diagram 1. Day After Tomorrow (Hinssen, Citation2017).

Hinssen (Citation2017, p. 163) cites Chairman Lee from Samsung stating that “Business is perpetual crisis. Pioneers meet every crisis head-on, and they triumph over it. Again and again”. Hinssen (Citation2017, p. 213) references “Political Myopia”, “Corporate Myopia”, and “learned helplessness”, especially in large organizations to stress the difficulties when changing (the mind-set of) people and organizations.

IA can help sorting the “SOY”. IA can help overcoming “Myopia”. IA can help dealing better with “learned helplessness”. IA can be instrumental when providing transparency about WHAT IS (Assurance) and giving guidance about what to do, thereby addressing SO WHAT (Advisory) type of questions. More importantly, internal auditors can and should (more often) step up and render value when dealing with future value (Tomorrow) and long-term value creation (Day After Tomorrow). That is unknown territory for all stakeholders. That is the pioneering zone.

There is a lot of truth in Hinssen’s illustration and thinking (Citation2017). Legacy systems, processes, and people can be a burden, costing time and energy, without creating value. The CEO at Bayer AG,Footnote6 Bill Anderson, not only wants to modernize Bayer AG, he wants to revolutionize it, he wants to streamline the corporate bureaucracy and reintroduce independent thinking among middle managers (Financial Times, Citation2023). This is a prominent example of the corporate world unmasking the “illusion of control, deeply hardwired in our thinking” (Burkhardt, Citation2018, p. 72). Independent, original thinking is vital especially when companies enter the pioneering zone, dealing with complex and chaotic circumstances. We are all in the pioneering zone when launching new products, introducing new software, hiring new people, acquiring, and integrating companies and so forth. Pioneering is the new normal, to say so, in the dynamic and fast-paced world of VUCA and BANI we live in.

This is also relevant for the future of internal auditing. We do need more independent and original thinking when aspiring to add value in the pioneering zone. Since the days of COVID-19, we are de facto all in the pioneering zone.Footnote7 Since COVID-19, all internal auditors need to start doing (more) remote-auditing, for example. In the crisis of COVID-19, building on the auditors’ social capital became mission critical. Relationship equity has become key and a prerequisite for internal audit to be part of the solution (and not the problem). High flexibility is indispensable. In the days of COVID-19, it was a smart move for internal auditors to ask senior management and the board, “How best can internal audit help the organization during the crisis”? That conversation may lead to fresh perspectives and a new focus on the activities. Internal auditors might assume roles beyond their traditional core remit, depending on the specific organizational context. Lenz and Hoos (Citation2023) reference in their ABC article ESG as an example, suggesting internal audit to widen its repertoire, add “Building” (B) to the traditional roles of rendering Assurance (A) and Consulting (C) type of services. In the webinar with 2,000 registered participants on 30 January 2024Footnote8 about “Rethinking Internal Audit: Governance Needs Gardening” I also reference designing an Internal Control System and leading a Global Working Capital Initiative as real-life examples from my practice as Chief Internal Auditor.

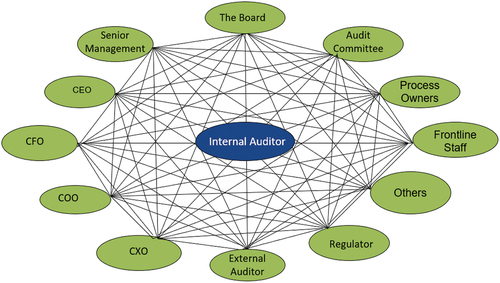

I regard shared goals, shared knowledge, mutual respect, and effective communication (frequent, timely, accurate, and problem-solving minded) as key ingredients of a successful value-adding internal audit function. These are the elements of Jody Hoffer Gittell’s Relational Coordination TheoryFootnote9 (also referenced and applied to the context of IA by Lenz, Citation2013). In 2024, over ten years on, time is ripe for further research exploring the power of that theory in the corporate governance ecosystem.Footnote10 I picture the internal auditing process as a complex coordination challenge ().

As “there is nothing so practical as a good theory”,Footnote11 I view Jody Hoffer Gittell‘s Relational Coordination Theory (RCT) as particularly relevant and helpful when aspiring to nurture and strengthen the corporate governance ecosystem. I encourage further (qualitative) research, thereby also challenging the metaphor, “The Gardener of Governance: Our nature is Nurture” (Lenz & Jeppesen, Citation2022).Footnote12

Effective Internal Auditors Must Have Strong Human Skills, Including Authenticity

Drašček (Citation2024) rightfully asks “How does Internal Audit create value?” and “What is Internal Audit uniquely good at?” To address these valid questions I draw our attention, given the VUCA and BANI world we live in, and being in the age of artificial intelligence, to “rethink what it means to be human, rethink the skills that make us strong” and “shift from following logic to living with chaos”, referencing Burkhardt (Citation2018, p. 16, 175).

Many professional peers appreciate the Gardener metaphor. The amazing traction of the metaphor by practitioners is encouraging.Footnote13 The Gardener metaphor suggest the effective internal auditor to be respectful toward planet and people, to nurture/strengthen things, and to humbly work indirectly, not being the Chief Executive Officer (CEO). No metaphor works for everyone and every context. Taking the origin of the Latin word audire, there is consensus that internal auditors must be good at listening. Internal Auditors are not super-men, not super-women. There is consensus about that, too, I like to believe. There are often, though, long lists of attributes which go in the direction of internal auditors as “super-heroes”, unfortunately. I wonder what the ordinary internal auditor can realistically do and what to focus on. The leading question I want to get a good grip on is: “What makes IA distinct from other actors in the governance arena?”

Many professional peers might first advocate “objectivity” and “independence.” I am taking a different stance. I suggest a different perspective. I advocate a more realistic positioning, as I view it, which could help to further increase credibility in the eyes of key stakeholders. When reflecting on these legacy attributes of what traditionally characterizes internal audit, I suggest de-emphasizing both attributes, “independence” and “objectivity”. In my eyes, both traditional values are aspirational, and when aspiring to prevent governance failure (Korine, Citation2020) I regard the traditional traits of “objectivity” and “independence” of little value. Hence, I challenge both here.

Let me start with “objectivity.” Objectivity per se is worth striving at, I agree. When things are simple, there is objectivity, “verifiable reality” (O’Regan, Citationforthcoming), for example: “1 plus 1, equals 2”. Also, when things get complicated, for example engineering a Ferrari, there is objectivity, there is an exact plan and model how to build that vehicle. There is, however, no objectivity in the pioneering zone (Lenz & Hoos, Citation2023). There is no single truth when things get complex or chaotic. Here, there is no one right answer, there are pieces to the puzzle, the complete picture is typically fuzzy, there are alternative paths to consider, there are trade-offs. What I call “WHAT IF type of questions” can then be helpful here. Internal auditors like viewing themselves as truth finder, but: “Truth only comes in two”,Footnote14 it takes more than one perspective to get a good grip on what is truly happening in the pioneering zone, and what the root causes of issues are. “Reality is a constant battle”, as Burkhardt (Citation2018, p. 47) puts it nicely, “by sharing what we know, we put our part of this reality on the table and others validate what we know or they reject it.” In my view, after 30+ years of international experience in global organizations as senior financial leader in CFO type of roles and Chief Internal Auditor since 2007, I recommend this humble approach to my professional peers in the world of internal auditing. In doing so, I suggest de-emphasizing “objectivity” as a core asset of internal auditors for there is no single truth in the pioneering zone. There cannot be complete objectivity, anyway, for everybody views the world with his/her pair of eyes. Education, experience, values, inner beliefs, and motivation have an impact.

Let me turn to “independence.” Also, independence per se is worth striving at, I agree. However, “there can be no such thing as complete independence” either, I fully concur with Chambers (Citation1992). So, I wonder, why bringing something to the fore that is not achievable? I acknowledge the value of the theoretical argument of the “principal-agent-theory,” owners/shareholders and management are different bodies with (potentially) diverging interests. Internal audit can play a role safeguarding the interests of the owner, and of the public. I agree with that. However, I wonder and challenge the reader with my following question: who really believes that internal auditors are more independent than, say the compliance officer, the general counsel, or external auditors? You have rightfully guessed my stance: I have no evidence supporting the perspective that internal auditors are more independent than those other actors in the governance mosaic.

I suggest pursuing a different path. I argue that there are more distinct traits of the internal auditor, true unique selling propositions, internal auditors can be superior given their role and position. Inspired by Frei and Morriss (Citation2020, p. 115), I understand, “Leadership really isn’t about you. It’s about empowering other people as a result of your presence, and about making sure that the impact of your leadership continues into your absence.” I view internal auditors as “Gardeners”, their nature is nurturing, strengthening, also mentoring. Helped by the Gardener metaphor, I point to the particular importance of human skills, some say soft skills, however I prefer calling these human skills, for they are far from being soft. Hence, I recommend positioning IA fundamentally in the Human-To-Human business. Internal auditors are not robots. Neither are their peers or clients. With the rapidly growing relevance and influence of artificial intelligence (AI), “now is the time to rethink what it means to be human” suggests Burkhardt (Citation2018, p. 16). He continues alerting, “In a digital, globalized world, however, the need for humans who behave like robots is decreasing rapidly” (Burkhardt, Citation2018, p. 122).

To succeed in the age of artificial intelligence, human beings need to focus on what human beings can do better than robots. Thereby, humans need to exploit the technology available, the technology should not exploit human beings. I suggest a model with five competence blocks which I regard as distinct characteristics of the modern, the effective internal auditor, becoming a value driver (Eulerich & Lenz, Citation2020) in the pioneering zone.

Human workplaces of the future demand these top five competences, says the World Economic Forum (Citation2023)Footnote15: 1 Analytical thinking, 2 Creative thinking, 3 AI and big data, 4 Leadership, and 5 Curiosity and lifelong learning. I build on that when suggesting my model of the top five competence blocks the effective internal auditor will need to excel in the future. To become a genuinely empowering internal audit leader, I introduce the “Trust Triangle” (Frei & Morriss, Citation2020) as pinnacle of my pyramid of competences ().

I view trust as the key to success and impact. “Being trusted” is the foundation (Lenz & Chesshire, Citation2023). “People tend to trust you when they think they’re interacting with the real you, when they have faith in your judgement and competence, and when they believe you care about them,” summarize Frei and Morriss (Citation2020, p. 114). Chambers (Citation2017) has coined the term “Trusted Advisor”. Jacka (Citation2019) defines the leading paradigm of internal auditors as “A trusted advisor is one of the first people you turn to when you have a decision to make, need feedback, or just need an honest appraisal of a situation. It is someone with whom you can freely share information; someone who can help you analyze the current situation; someone who will be honest; and someone who will provide valuable, critical, and constructive advice in times of need.“Footnote16

The Trust Triangle (Frei & Morriss, Citation2020) has the components of logic, empathy, and authenticity. Logic represents analytical and critical thinking, reasoning and judgment are sound. Empathy is the key to people’s heart, a promising path more fully understanding the underlying root causes. Without empathy the dialogue between the client and the internal auditor typically remains transactional, questions and answers, a question triggering a response type of conversation. Without a sincere human-to-human connection all brilliance of the internal auditor might easily be futile. With empathy, the dialogue can become transformational, enabling lasting impact and change. When the internal auditor genuinely cares about the client and his success, when there is a heart-to-heart connection, to say so, this may open the gate to unknown territory, to discuss the real issues, the root causes, thereby regularly going far beyond the imagination of the internal auditor when starting the engagement. With the Trust Triangle (Frei & Morriss, Citation2020) I introduce Authenticity as new anchor term to the discourse of the effective internal auditor, right on top of my competence pyramid, as the pinnacle of the value driving internal auditor (Eulerich & Lenz, Citation2020), as I view it. The term stresses the need that clients experience “the real you.” That REAL YOU is not about objectivity, it is about YOU, it is about who you are as a person, it is about subjectivity, how you make sense of the world around you. In the age of artificial intelligence, to say it with Burkhardt (Citation2018, p. 144) humans should “Shift from Being Normal to Being Unique”. Thereby, and that has not changed: “The real challenge is to identify a really good question” (Burkhardt, Citation2018, p. 73).

Frei and Morriss (Citation2020, p. 118) propose “A quick test: How different is your professional persona from the one that shows up around family and friends? If there’s a sharp difference, what are you getting in return for masking or minimizing certain parts of yourself? What’s the payoff?” I invite internal auditors to reflect on their personality on and off the job. Are there big differences? Is that in sync? I view authenticity as the core pillar when building trust. I alert to challenges what authenticity is concerned when the human being and his/her role as internal auditors are not in sync. Authenticity is about the REAL YOU when performing internal audit work, too. That perspective is diametrically different from aspiring “objectivity” or an “objective viewpoint” (PwC, Citation2023, p. 10).Footnote17

While the three building blocks of the Trust Triangle (Frei & Morriss, Citation2020) are crucial, there is more the effective internal auditor needs to excel at in my understanding. I suggest a model with five building blocks. My short-list of all must-haves. None of the skills should be left out ().

I view Collaboration, Communication, and Kindness as prerequisites. “Treat People With Kindness” is a song-title from Harry Styles.Footnote18 I regard kindness as fundamental. We internal auditors do not know what our clients go through in life. Hence, whatever message there is to convey, however delicate the topic might be, we are humans interacting with humans. Kindness is mandatory, non-negotiable. We live in an interconnected world. We can only make sense of the world around us when successfully interacting with people. There is no single truth when things get complex and chaotic, that is, in the pioneering zone. Collaboration and communication are indispensable skills of the effective internal auditor.

The effective internal auditor is no “know-it-all”, no “Jack of All Trades Master of None”, s/he is rather a “learn-it-all”. Curiosity, Lifelong Leaning are part of the modus operandi, the way of working. Effective internal auditors enjoy entering unknown territory, being pioneers. The effective internal auditor is keen on learning. I position IA as enablers of learning and change referencing Scharmer (Citation2009), helping to overcome the four barriers to learning and change: NOT to see what we do, NOT to recognize what we see, NOT to say what we think, and NOT to do what we say.

Curiosity and lifelong learning include mastering technology. That is of utmost importance for internal auditors because Eulerich et al. (Citation2023) state that “accountants, auditors, and tax preparers as having a 100 percent exposure to significant automation.” Eulerich et al. (Citation2023) demonstrate that ChatGPT passes professional exams with flying colors, including the exam of the CIA, the Certified Internal Auditor. Moreover, Emett et al. (Citation2023) report “that Uniper, an international energy company, is using ChatGPT in the internal audit function, testing its use in audit preparation, fieldwork, and audit reporting. Initial reports suggest efficiency gains ranging from 50 to 80 percent.” This raises fundamental questions about how the robot (machine) and internal auditors will work together in the future. My plea is that effective internal auditors must have strong human skills, must be people-orientated. Moreover, I concur with Alexander Ruehle’s (CEO at https://www.zapliance.de) viewpoint that “people-orientation is and will stay the most important skill. … People-orientation without data and technology base will not suffice anymore.”Footnote19 Hence, IA must benefit from Computer-Assisted-Auditing-Techniques, including analyzing big data and unearthing patterns in the digital traces in Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems, increasingly helped by artificial intelligence, too. In 2017, I might have been early with the claim (Lenz, Citation2017), a few years on, in 2024 it is a fact: Time is Ripe to Revolutionize Internal Auditing.

In the world of VUCA, the days of Jack-of-All-Trades (Know-it-all) in internal audit are counted. My mini-typology of internal auditors (Lenz & Hoos, Citation2023) distinguishes three different types: Type 1: Standing on the sidelines; Type 2: Swimming in a calm pool; and Type 3: Surfing the wild ocean. To gain relevance, the internal audit profession needs more type 3 auditors, more pioneers, and innovators. In the world of VUCA, checklists no longer help.

Courage, Standing Tall (when it matters), and Integrity are must-have attributes. As a younger auditor I erroneously viewed internal auditors as having no fear, having no favor. With more experience under my belt, I maintain the latter, I correct the former. I have fears. Human beings have fears. Mark Twain puts it beautifully: “Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear – not absence of fear.”Footnote20 There are “moments of truth” (Lenz, Citation2013) in an auditor’s life. In such moments, internal auditors need to be courageous, stand tall, and say what needs to be said. That requires integrity, doing and saying the right thing when it matters most. In doing so, internal auditors can nurture psychological safety (Edmondson, Citation2019), foster a speak-up culture. Internal audit operates in the political space. There are toxic workplaces. Demonstrating courage, standing tall when it matters, can have career limiting consequences in toxic organizations. As Edmondson (Citation2019, p. 190) puts it: “The hard part isn‘t knowing what the right thing to do is. The hard part is doing it.“

In the corporate world many internal auditors operate in, Business Acumen is indispensable. The effective internal auditor understands the business s/he is working in. To be effective, internal auditors must be able to put his/her perspective into the given context to distinguish the relevant from the irrelevant. IA serves internal purposes. IA is contextually bound (Lenz, Citation2013).

On 30 January 2024, I kicked-off two identical polls on LinkedIn, being interested in learning the perspectives of my professional community. Both polls were open to answer for two weeks. As the effective internal audit leader needs many and increasingly more competences and characteristics, I was asking: “If you had to pick THE one most important competence/characteristic, what would you choose? The options provided are in alphabetical order. Please comment on your rationale, if you wish, and/or suggest (more important) missing options.” As options to choose from I offered the three components of the Trust Triangle, complemented by Business Acumen ().

Table 1 Polls on LinkedIn about most important competences of internal auditors.

Notably, Business Acumen was ranked on pole-position when running polls on LinkedIn, in both cases, the open poll (136 votes) where anyone in my network with 11,000+ followers could respond, and the poll in the official subgroup on LinkedIn of The IIA (476 votes). Interestingly, Authenticity, a fresh term in the discourse about competences of internal auditors has enjoyed much traction and was the runner-up in the poll with professional peers in internal auditing.

The list is not exhaustive. There is more. The list of desirable traits is endless. Those five building blocks are what I regard as must-haves of the effective internal auditor. There are as many other views out there as there are professionals.Footnote21 Whatever the perspective may be, I recommend limiting the set of skills and attributes to a handful or so, only. Otherwise, the set of criteria becomes too much like a super-man, super-woman profile, which gets unrealistic. With this I would like to trigger a debate in the professional community about the Top 5 competences of the effective internal auditor. I recommend the professional standard setter, The IIA in the US, to reflect on the most important human skills of the effective internal auditor and consider that (more) adequately in the curriculum of the CIA program, and the normative guidance, the Standards, too.

To Heighten Effectiveness, The Professional Standards Must Become Principles Based

The IIA Standards are a “normative force” (Lenz & Hahn, Citation2015): “The stronger the normative force of the IIA, the more effective the IAF [Internal Audit Function] may demonstrate itself to be by conforming to the IIA’s good practice principles.” Conformance with the IIA Standards per se says de facto little (nothing) about the performance of internal auditing, its effectiveness and value provided.

The Global Internal Audit Standards (IIA, Citation2024a) take up 120 pages. In the fast-paced world of VUCA and BANI I view such de facto highly prescriptive, and compliance minded Standards of questionable value. The -as I view it- wordy new Global Internal Audit Standards (IIA, Citation2024a) cause stress for many Internal Audit Functions, as my network signals me. Unnecessary stress, I argue, for there is de facto not so much news versus the prior version of the Standards (IIA, Citation2017). The wordy text might suggest otherwise for many professional peers.

When reflecting on “What is really, new about the new Standards? What is the updated content that matters most in the recently published Global Internal Audit Standards?” I note three significant changes, in addition to the new structure and the new name (IIA, Citation2024a):

The PURPOSE of internal audit has been revised, more words, now twenty-eight words if counted properly (with risk-based as one word). It now says: “Internal auditing strengthens the organization’s ability to create, protect, and sustain value by providing the board and management with independent, risk-based, and objective assurance, advice, insight, and foresight.” I doubt that more words make it more convincing and impactful. Drašček (Citation2024) rightfully suggests further research, clarifying the purpose of internal auditing.

Domain IV (Managing the Internal Audit Function), Standard 9.2 Internal Audit Strategy, it says: “The chief audit executive must develop and implement a strategy for the internal audit function that supports the strategic objectives and success of the organization and aligns with the expectations of the board, senior management, and other key stakeholders.” This is a new mandatory requirement. Chief Internal Auditors will have to formalize their internal audit strategy, that is, “a plan of action designed to achieve a long-term or overall objective”, as the standard puts it, and evidence alignment with key stakeholders. The future will tell how relevant and impactful such strategy can be in the fast-paced and fast-changing world of VUCA and BANI.

TOPICAL REQUIREMENTS (yet to come at the time of drafting our article) are an integral part of the mandatory Global Internal Audit Standards (Citation2024a).

These are my top three. Moreover, there are some added terms, including courage and professional skepticism, for example, terms I value. I included courage into my competence model.

The topical requirements as mandatory components of the Standards are tricky territory. First, because our fast paced and fast changing world of VUCA, BANI, and permacrises might not allow to remain “topical” easily. Also, when going down that path, the IIA competes here with many other standard setters, possibly more competent and more current on their specialty turf, for example, cyber security. When establishing a profession (Abbott, Citation1988) there must be competition and turf battle, here, however, I question whether making such topical requirements mandatory is a smart move. I acknowledge the motivation, the intent of the IIA to heighten the overall quality of internal audit services rendered that way, especially helping lower performing internal audit functions to deliver better value. I fear though, the IIA is on soft ground when issuing topical requirements as part of the mandatory requirements. At the end of the day, this might easily water the value proposition and hurt the professional claim of the IIA profession even further. I see the risk of over-promising and under-delivering. Topical requirements might be easily outdated rapidly. Moreover, some professional peers, including me, might easily perceive forthcoming topical requirements as sort of “straight-jackets”, baggage to say so, in the way of rendering value adding, possibly agile, internal audit services. I might be mistaken. I hope so. The future will tell.

When taking a critical stance, the many words used demand lengthy reading, and create a need for gap analyses, transitioning work, training programs and so forth, all enablers for enhanced revenue of the professional standard setter and all the associated parties, consultancy firms, etc. I see all sorts of business proposals mushrooming, “helping” internal auditors to transition from complying with IPPF 2017 to complying with the 2024 Standards. When thereby thinking especially of the many small IAFs, there is easily much time wasted, I fear. At this point, I wish to state that I have no commercial interests. I do not offer paid consultancy services or else. I am purely content driven.

In fact, whether we like it or not, there is nothing as constant as change. Going forward, I encourage the professional standard setter to consider alternative approaches. I suggest benefitting more from the power of competition. More precisely, when the next revision comes on the agenda, I recommend inviting various groups of people in parallel for searching alternative paths to strengthen the normative power of the Standards. Artificial intelligence might then be well equipped to make a proposal, too. I expect such competition to trigger innovation. I encourage the professional standard setter to invite competing groups of people working on creative and alternative ways of updating the Standards. That competition might help finding innovative solutions, best tailored to the needs of the professional community.

As always, there are different views in the community. And, that is a good thing, that is healthy. High consensus can be misleading. At this point in time, it is reasonable to get on with the standard. It is now what it is.

To conclude, and with the ambitions in the pioneering zone on my mind as the arena where I suggest the relevant, impactful, and effective internal audit function to operate in, and to increasingly make contributions in such complex and chaotic contexts, also in the eyes of key stakeholders, I see value in principles-based professional Standards.

Let’s see how the new IIA standards work out in practice. “Only practice contains all theory” (Kappler, Citation1988). There is nothing as constant as change.Footnote22

On to part 2.

SECOND SECTION

In the second section of this co-authored essay O’Regan will consider the conceptual foundations and interpretative purposes of professional Standards in general, before evaluating the extent to which the IIA’s Standards might relate to notions of knowledge and expertise in IA, and to the principles of professional altruism and the public good.

PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS, EXPERTISE, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD

Before embarking on any type of analysis, it is worthwhile defining one’s terms. For my purposes in this paper, I shall define a profession as “an occupation characterized by a high level of expertise and a commitment to serving the public interest”, and a professional standard as either “a rule or guideline” that nurtures professional practices (O’Regan, Citationforthcoming). Despite the ostensible simplicity of these definitions, they carry profound implications, and both definitions contain two elements – respectively expertise/altruism and rules/principles - that might be challenging to balance in day-to-day implementation.

For any profession, technical expertise and an altruistic commitment to the public interest are necessary but probably insufficient characteristics. Sociologists (e.g., Abbott, Citation1988, pp. 35–113; Kultgen, Citation1988, p. 60; and Macdonald, Citation1995, passim) have identified as many as 20 traits of a profession, including stringent certification requirements and the use of legislation and other legal instruments to monopolize markets. My focus in this paper will be narrower than the typical scope of the sociological literature, as I shall restrict my discussion to the co-existence of technical expertise and altruism in professional activity. (I shall set aside the question of whether the IIA’s brand of internal auditing qualifies as a profession in the absence of monopolistic control of the internal auditing market.)

The significance to a profession of the co-existence of the traits of technical expertise and altruism is difficult to exaggerate. Altruism is inadequate without technical expertise: one would surely decline an offer of pro bono dental services from an individual who admits to having no formal dental training. Similarly, technical expertise is inadequate without altruism: one might grudgingly acknowledge the detail-focused proficiency of a bank note counterfeiter, but withhold approval because this type of expertise is undermined by the absence of an ethos of public service. I therefore conclude that neither the generous, uneducated fool nor the “professional criminal” is truly a professional in the sense understood in this paper. A professional’s expertise must be intertwined with a commitment to the public good. A profession with serious deficiencies in either expertise or altruism would fall short of the mark of an authentic profession in the public’s eyes.

IA, naturally, is no exception to the necessity of these two traits. When Flint suggested that the authority of auditors’ opinions rests on the public’s “confidence in the technical competence, reliability and integrity of the auditors” (Flint, Citation1988, pp. 45–46), he highlighted our dual themes of reliable technical competence and altruistic integrity. I shall explore further these two necessary traits of a profession and how they might relate to the IIA’s Standards.

Knowledge and Expertise in The IIA’s Standards

Professional expertise invokes the notions that (1) the expertise derives from a largely abstract body of knowledge, (2) the possessor of the abstract knowledge is capable of applying that knowledge in practice, and (3) professional knowledge is cumulative: it is not merely a matter of mastering a fixed body of knowledge at a single point in time, but rather of mastering a foundation of knowledge upon which further experience and learning accumulate. It is in the second and third of these attributes, where knowledge overlaps with expertise, that professional Standards play a significant part. Standards do not usually deal with abstract bodies of knowledge, but rather with the pragmatic application of bodies of accumulated expertise to everyday situations.

In evaluating the professional Standards for IA one encounters, at the outset, a not negligible problem: in contrast to other specialties of auditing, the knowledge base of IA is elusive. For example, the knowledge base of external auditing is grounded in accounting, with an emphasis on double-entry bookkeeping; the accounting equation of assets = liabilities + capital; and the abstraction of accounting information into financial statements. Election auditing is grounded in the mechanics of the political franchise. Royalty auditing is based on the dissemination (e.g., through sales) of the underlying units of intellectual property. And underpinning environmental auditing are the “firm” sciences relevant to the sustainability of the natural world, including biology, oceanography, and zoology. Internal auditing has no such solid knowledge base – there is, therefore, no simple “scientific” solution to the problem of developing adequate Standards for IA. To a greater extent than other categories of auditing, IA is an overtly social construct. The elusiveness of IA’s knowledge basis implies that the IIA’s standard-setting process is likely to spend significant time balancing opinions rather than gathering facts, and that the standard-setting process will therefore necessarily involve extensive dialogs on compromises and trade-offs. The IIA’s remarkable transparency in its revision of its Standards suggests that transparency has been a means of meeting the challenges of IA’s socially-constructed and often contested foundations.

The reader might at this point counter that the IIA’s “common body of knowledge” (CBOK) is a credible body of abstract knowledge. The latest version of the IIA’s CBOK commenced in 2015 with practitioner and stakeholder surveys, and it remains, at the time of this writing, an ongoing project that has generated a suite of reports, mainly summarizing the opinions of practitioners and stakeholders. The CBOK does not therefore derive from abstract reasoning but instead from a consensus or preponderance of opinions relating to generalizations of existing practices. It is difficult not to conclude that the knowledge base of IA is a rather insecure and fragmented agglomeration of elements taken from management theory, accounting, information technology, legal topics, bureaucratic proceduralism, fraud awareness, corporate governance mechanisms, and risk assessment, bound together by logical assessments of the evidential material encountered in auditing. Owing to the eclecticism of such a broad knowledge base, it is little wonder that Michael Power described IA as a “ragbag of tasks and routines in search of a unifying role or idea” (Power, Citation2000, p. 18).

The elusive epistemology of IA does not, however, imply that the IIA’s Standards have no systematic foundations. A body of knowledge for an activity like IA is not merely an accumulation of concepts or an inventory of theories, whether socially constructed or otherwise: a formal structure with logical, orderly patterning is required to give it coherence. By analogy, a pile of bricks does not make a house—the arrangement of the bricks in logical and systematic patterns is needed to construct a house. It is therefore the primary purpose of the IIA’s Standards to provide a coherent, logical arrangement of the raw materials of the CBOK’s building blocks of knowledge, so as to create a credible, and socially acceptable framework for IA. This task, the latest iteration of which has resulted in the IIA’s Standards of January 2024, entails making decisions on deep perplexities inherent in IA. Does IA embody objective knowledge? Is it an activity founded on applied logic? Is it an amalgamation of empirical beliefs and time-tested practices? Is it a means of pursuing a “professionalization project” for internal auditing (as suggested in O’Regan, Citation2001)? IA is a complex mixture of some or all of these interpretations and, whether implicitly or explicitly, such considerations have underwritten the IIA’s Standards-setting process. As I have suggested, in comparison with many current auditing specialties IA has the most slippery and unsettled knowledge base, which lends itself to a wide variety of interpretations. The elasticity of the IIA’s CBOK and Standards accommodates a wide range of opinions, perhaps explaining, at least in part, why public commentary on the exposure draft of the IIA’s Standards sometimes involved, in 2023, intensely emotional and idiosyncratic polemics. I conclude that only principles-based standards can satisfactorily capture and convey IA’s rather elusive knowledge base, because the slipperiness of IA’s foundations lends itself to multiplicities of interpretation that prescriptive rules cannot satisfy.

A final reflection on the complexities of the capturing of knowledge in professional standards before I move on to consider questions of serving the public good. One might identify three broad categories of professional knowledge. We may possess knowledge of something (e.g., “her knowledge of the IIA’s Standards is thorough”); we may possess knowledge of how to do something (e.g., “she knows how to implement the IIA’s Standards”); and we may possess knowledge that something is the way it is (e.g., “she knows that the inventory most at risk from shrinkage is stored in the overspill warehouse down at the docks”). All these categories of knowledge are relevant to IA. The first two categories (knowledge of something and how to do something) address, respectively, theoretical and practical knowledge. The third category (knowledge that something is the way it is) is knowledge at a far more complex level – it derives from and transcends the first two categories of knowledge to form high-level expertise, in which professional opinions wrestle with both facts and value judgments. Expertise of this nature, with wide applications to specific circumstances, is extremely difficult to capture in written Standards (O’Regan, Citation2017). Professional Standards generally address the second and third categories of knowledge. The process of standard-setting therefore grapples with highly complex aspects of expertise, and it is no surprise that the outcomes of standards-setting processes are frequently contested. On that note, I turn to understandings of morality and judgment in professional Standards.

The IIA’s Standards and the Public Good

The second necessary trait of a profession is an altruistic commitment to the public good. The IIA has made clear its intention for its Standards to serve the public interest, as indicated in the title of the IIA’s IPPF Oversight Council’s Framework for Setting Internal Audit Standards in the Public Interest (IPPF Oversight Council, Citation2022, emphasis added). In the month following issuance of the IIA’s Standards, a senior IIA official confirmed that the IIA’s Standards “need to serve the public interest” (Seeuws, Citation2024, p. 33).

Professional Standards have the advantage of encouraging consistency in professional activities, and reliability in professional decision-making. But four disadvantages of prescriptive professional Standards have been identified (in Myddelton, Citation2004, pp. 96–109), as follows: (1) the stifling of professional judgment, (2) the discouragement of competition in ideas, (3) the legitimization of bad practices, and (4) a misleading of the public by unduly raising expectations of professional performance. It is the first of these criticisms that concerns me here, perhaps allied to a degree to the third criticism.

In evaluating the capability of the IIA’s Standards to serve the public interest, I return to my definition of professional Standards in the introduction to this paper, in which I suggested the alternatives of a “rule” or “guideline” approach. I might rephrase this as a choice between rules-based or principles-based Standards, and this differentiation reaches to the roots of my enquiries. The shortcomings of “cookbook” professional rules are widely acknowledged. Rules provide only a limited number of “recipes”, insufficient to cover every possible combination of circumstances. An awareness of the dampening effect of prescriptive rules on individual judgment and critical thinking in auditing has a long history. The Dutch auditing theorist Theodore Limpberg Jr. (1879–1961) expressed in the early 20th century the view that (financial) auditing “ought to be characterised by the application of intellectual effort and expert insight … rather than by thoughtless reliance on established routine” (quoted in Camfferman & Zeff, Citation1994, pp. 123–124).

In my view, recent IIA Standards, prior to the issuance of the IIA’s Standards in January 2024, have been tilted far more toward rules than principles. The prescriptiveness of the IIA’s Standards has petrified individual judgment and critical reasoning, thereby narrowing intellectual and moral horizons in IA. Principles-based Standards tend to encourage the internal auditor to apply universal interpretations to particular cases or, in other words, to apply abstract concepts to concrete examples. By following rules, in contrast, the focus of internal auditors has been on process over substance, inculcating a checklist-based mind-set in which moral agency is diminished. Under these circumstances, individual judgment has been downplayed in recent years, and a collective conformity has descended on IA like a heavy shroud. Power has suggested that “[d]espite being widely and commonly criticized, box-ticking approaches [associated with rules-based auditing Standards] persist because they correspond to a particular climate of auditability which pervades risk governance” (Power, Citation2007, p. 164).

The prescriptiveness of IA Standards has not had a positive influence on promoting the public good. To deploy their expertise in the service of the public interest, internal auditors are required to exercise moral agency, which has been defined as acting “in a manner that expresses concern for moral values as final ends” (Garofalo & Geuras, Citation2006, p. 3). In this sense, morality is intrinsic, not instrumental, and it is not a means to an end but an end in itself. Moral agency therefore implies both the ability and the opportunity to rationally arrive at moral decisions, and to face accountability for those decisions. For internal auditors, there is no equivalent of the physicians’ Hippocratic Oath and its explicit exhortation of what has become the principle of primum non nocere (“above all, do no harm”). Internal auditing nonetheless demands moral agency and individual judgment from its practitioners. For example, an internal auditor may feel a strong sense of loyalty to her employer, and this loyalty may on occasion come into conflict with a duty to serve the public interest. Should this internal auditor blow the whistle on institutional wrongdoing, thereby flagging it to the wider community, or should she merely report it internally, for discreet, in-house handling? The internal auditor’s dual responsibilities are in conflict in such a situation. In facing a sliding scale of judgments between such extremes of possible conduct, the internal auditor’s thoughts are pushed to levels of nuanced enquiry that no rules-based Standards can satisfy.

One might expect the IIA to honor its commitment to serve the public interest by cultivating spaces in which the moral agency of its members can flourish, through principles-based Standards that encourage personal responsibility and promote sound judgment. The elaboration of principles-based Standards would enhance IA’s virtuous nature. The recent IIA’s Standards therefore presented an opportunity to move toward a principles-based approach, thereby to reverse the increasingly mechanistic style of IA that has prevailed in recent years, and to reorient IA more strongly toward concepts of virtue and public service. I therefore anticipated that the IIA’s recent Standards would move away from the amoral, clockwork approach encapsulated in the rules-based Standards of the IIA’s recent past, toward a more pronounced engagement of moral agency through the promotion of professional principles. I shall evaluate this aspect of the IIA’s Standards in the following paragraphs.

The IIA’s Standards, Rules, and Principles

I have suggested that the deployment of IA expertise in the service of the public good has been hampered in recent years by the failure of the rules-oriented IIA’s Standards to cultivate the flourishing of their members’ moral agency. The IIA’s Standards of 2024 have been described as “principles-based” and my preliminary assessment is that the grouping of the revised Global Internal Audit Standards under 15 principles is a step in the right direction. However, it is misleading or disingenuous to claim that the revised Standards are now principles-based. Certainly, it is good to organize the revised Standards by principles, but the Standards are now arranged by principles rather than arranged into principles. The principles in the IIA’s Standards serve primarily as classificatory headings, and the majority of the text consists, as in the past, of a bloated inventory of rules and requirements. My anticipation of a more extensive change of emphasis from rules to principles remains unfulfilled. To this extent, one may argue that the IIA’s revised Standards resemble old wine poured into new bottles.

Virtue is not a fussy, old fashioned, classical Greek or even Victorian construct, but a living part of what makes professional activity contribute to the human good. Virtues are “character-traits which we need to live humanly flourishing lives” (Oakley & Cocking, Citation2001, p. 18), and they are central to a wise deployment of moral agency in IA. Professional virtue entails the transcendence of written rules of behavior. The de-personalization of virtue arising from rules-based Standards detracts from the exercise of moral agency, and it is perhaps one of the greatest threats to the standing of IA. I consider the IIA’s revised Standards to represent a missed opportunity in terms of promoting virtue in IA, and advocate a future revision of the IIA’s Standards to achieve a preponderance of principles over rules.

I suggest two approaches to future IA standard-setting. First, as the IIA’s CBOK is conceptually anterior to the IIA’s professional Standards, there might be value in reimagining the CBOK, moving it away from an aggregation of surveys and opinions toward a precise, abstract conceptual model, from which principles may be extracted to form the nucleus of future Standards. The current, fuzzy connections between the CBOK and the IIA’s Standards constitute a gap that encourages the conflict of opinions and understandings at the heart of IA. Second, the IIA might emphasize the importance of traditional logic as an enduring, consistent methodological tool to evaluate audit evidence, to compensate for IA’s slippery and elusive conceptual base.

CONCLUSION

Two individuals with experience of chairing the International Internal Audit Standards Board (IAASB) have stated that the aim of the IIA’s Standards has been “to make the guiding principles and Standards more simply structured with greater clarity and alignment of their elements” (Mouri & Peppers, Citation2024, p. 29). This aim has clearly been met, through a rigorous Standards-setting process of unprecedented transparency. We consider the IIA’s Standards, issued in January 2024, to be an enhancement over the IIA’s previous Standards. The IIA’s Standards have been restructured and rearranged into more logical patterns. However, although the grouping under 15 principles of the 52 individual Standards has been a step in the right direction, the IIA’s Standards have not, as a whole, been revised into principles, but rather arranged by principles.

In our view, the IIA has missed an opportunity to transform its Standards into a radically creative, principles-based framework. The IIA’s technocratically-focused and committee-sieved revision of its Standards has therefore deferred, rather than answered, the core questions of how to encourage a strong foundation for IA expertise and how to promote moral agency in IA. We may have to wait for a future generation of internal auditors to establish professional Standards comprehensively comprised of principles. Otherwise IA runs the risk of becoming an activity of skilled technicians rather than the domain of accomplished professionals.

The authors derived their arguments independently, and it is instructive that, starting from different premises (e.g., in their approaches to the role of logic in IA) they both arrived at the conclusion that principles-based Standards will benefit the profession’s long-term ability to fulfil its mission. Although both authors arrived at the same conclusion they offer alternative suggestions for the future of IA.

Lenz draws our attention, in the age of artificial intelligence, to “rethink what it means to be human, rethink the skills that make us strong” and “shift from following logic to living with chaos”, referencing Burkhardt (Citation2018, p. 16,. 175). He introduces the Trust Triangle (Frei & Morriss, Citation2020) that places authenticity as anchor term to the discourse. Effective internal auditors must have strong human skills: he therefore suggests his model with five competence blocks of the most important skills of the effective internal auditor. There is no need for humans who behave like robots. The refined leitmotif of “The Gardener of Governance: Our nature is Nurture” is suggested as purpose for internal auditing (building on Lenz & Jeppesen, Citation2022). With the words of Burkhardt (Citation2018, p. 165), Lenz encourages the IIA profession to “Shift from Exploiting the Familiar to Exploring the Unknown”. He sees potential when encouraging individual judgment especially when entering the pioneering zone, characterized by complex and chaotic circumstances. In our VUCA and BANI world, checklists and prescriptive guidance no longer help. Time to think. Time to re-think! Lenz wonders what robots and what human beings (including internal auditors) will do next. Lenz recommends internal auditors to be authentic, showing the REAL YOU. Lenz wants internal auditors to stand tall when it matters. Or saying it with Burkhardt (Citation2018, p. 122): “We need to shift from ‘doing our job’ to ‘making a difference’”. He believes that positive, principles-based normative guidance can support that pursuit much better than the prescriptive Standards of today.

O’Regan suggests that the IIA considers a reimagination of its CBOK, moving it away from a loosely structured aggregation of surveys and opinion-gathering toward a precise, abstract conceptual model, from which principles may be extracted to form the nucleus of future Standards. In addition, an emphasis on the enduring value of logic as the conceptual glue that binds IA together might mitigate some of the slippery and vague aspects of the knowledge base of IA.

“To better understand the plurality in practice, we need to study the practice” (Lenz, Citation2013, p. 286). We would be delighted if our joint article is an encouragement for constructive discussion in the professional community and a starting point for future scholarly studies.

Acknowledgments

Rainer and David thank Dan Swanson, the Managing Editor of EDPACS, for the opportunity. We thank Alexander Ruehle, CEO at zapliance, for funding OPEN ACCESS.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rainer Lenz

Dr Rainer Lenz is a financial and corporate audit executive with 30+ years of international experience in global organizations. He has a PhD in Economics and Management Science from the Louvain School of Management in Belgium. Dr Lenz has earned several awards for his thought leadership, including the 2023 Bradford Cadmus Memorial Award from the Global Institute of Internal Auditors. He has a teaching assignment about Governance & Internal Auditing in the master program at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz (Germany). He can be reached at [email protected].

David J. O’Regan

Dr David J. O’Regan’s auditing experience spans the private, public, and academic sectors over three decades. He commenced his career in the United Kingdom with Price Waterhouse, a forerunner firm to today’s PricewaterhouseCoopers, and subsequently worked in industry before heading the internal audit function at Oxford University Press. He then entered public service in the United Nations system, initially at the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons in The Hague, Netherlands. From 2009 he has served as Auditor General to the Pan American Health Organization in Washington D.C. He earned a doctorate in accounting and finance from the University of Liverpool and is a Fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales. He has two books forthcoming – The Auditor’s Companion: Concepts and Terms from A to Z (Georgetown University Press) and The Closing of the Auditor’s Mind? (CRC Press).

Notes

1. According to Korine (Citation2020) (11),“When governance breaks down it is because of too much power concentration or not enough accountability or both.”

2. The term “Gardener of Governance” stems from Lenz and Jeppesen (Citation2022). The refined wording “The Gardener of Governance: Our nature is Nurture” (September 2023) benefits from contributions by Kathleen Carroll (Brand Positioning Expert) https://drrainerlenz.wordpress.com/2023/09/07/gardeners-of-governance-its-our-nature-to-nurture/.

3. VUCA stands for: Volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity, Wikipedia, accessed online, 12 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VUCA.

4. Is BANI the new VUCA? Agile work in the 21st century, accessed online, 12 February 2024, https://www.leaders21.com/en/blog/is-bani-the-new-vuca-agile-work-in-the-21st-century/; BANI stands for Brittle, Anxious, Non-linear, and Incomprehensible.

5. SOY stands for “Shit of Yesterday” (Hinssen, Citation2017, p. 58).

6. Financial Times (Citation2023), “With 101,000 employees and €50.7bn in revenue, Bayer is one of Europe’s largest corporate juggernauts, owning 354 consolidated companies in 83 countries.”

7. Building on Lenz’s blog from May 2020: https://drrainerlenz.wordpress.com/2020/05/08/we-are-all-in-the-pioneeringzone-now/.

8. Recording via YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aF3wnnP0i64, and Lenz’ blog about the event from 12 January 2024: https://drrainerlenz.wordpress.com/2024/01/12/cpe-webinar-rethinking-internal-audit-governance-needs-gardening-30-january-2024/.

9. Accessed online 04 February 2024, https://rcanalytic.com/rctheory/.

10. Lenz’ blog from 15 September 2023, after initial discussion with Professor Jody Hoffer Gittell, https://drrainerlenz.wordpress.com/2023/09/15/internal-audit-as-gardeners-in-the-governance-ecosystem-gittell-lenz-2023/.

11. Lewin, K. (Citation1945). The research center for group dynamics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Sociometry, 8, 126–135, cited in Van De Ven, A. H. (1989). Nothing is quite so practical as a good theory. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 486–489.

12. The idea stems from Lenz and Jeppesen, (Citation2022). The refined wording “The Gardener of Governance: Our nature is Nurture” (September 2023) benefits from contributions by Kathleen Carroll (Brand Positioning Expert) https://drrainerlenz.wordpress.com/2023/09/07/gardeners-of-governance-its-our-nature-to-nurture/.

13. There are (will be) 25+ translations of that publication, originally written in English https://drrainerlenz.wordpress.com/2023/01/01/translations-of-lenz-jeppesen-2022-the-gardener-of-governance-paper/. The Lenz and Jeppesen, (Citation2022) article is with 27,000 reads (accessed online on 04 February 2024) by far the most read publication of all time at EDPACS. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showMostReadArticles?journalCode=uedp20.

14. Arendt (Citation2015), German book title “Wahrheit gibt es nur zu Zweien“, Reprint 2020.

15. World Economic Forum Citation2023: Accessed online 04 February 2024 https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/.

16. Blog from 16 April 2019, accessed online, 12 February 2024, https://internalauditor.theiia.org/en/voices/20192/trying-to-define-trusted-advisor/.

17. PwC (Citation2023, p. 10) says “The ability to connect the dots and spot misalignment can often require an objective viewpoint.” We find that term misleading. There is no such thing like an “objective viewpoint.” We recommend internal auditors to become authentic. That is a pillar of the “Trust Triangle” (Frei & Morriss, Citation2020).

18. More about Harry Styles, please see on Wikipedia, for example https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Styles Accessed online on 04 February 2024.

19. Blog on LinkedIn, 11 February 2023 https://lnkd.in/e8eT3F3u.

20. Accessed online on 04 February 2024 https://www.quotespedia.org/authors/m/mark-twain/courage-is-resistance-to-fear-mastery-of-fear-not-absence-of-fear-mark-twain/.

21. For example, Herve Gloaguen (former Chief Internal Auditor at Allianz SE) regards humbleness, curiosity, and diplomacy as great soft skills for auditors (in a blog on LinkedIn on 12 January 2024). Garyn and McCafferty (Citation2023) suggest the following “Seven Characteristics of Internal Audit Leaders of the Future”: 1 Ability to Think Strategically, 2 Technology Acumen, 3 A Contortionist’s Flexibility, 4 Remote Communication Skills, 5 Prescience, 6 Ability to Build Bridges, and 7 Executive Know How.

22. According to Heraclitus “You can’t step into the same river twice”, Wikipedia, accessed online on 14 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heraclitus.

REFERENCES

- Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. The University of Chicago Press.

- Accountancy Europe. (2023, February). Multi-stakeholder analysis of corporate failures, building resilience in the corporate reporting ecosystem. Discussion paper.

- Arendt, H. (2015). Wahrheit gibt es zu zu Zweien. Reprint 2020. Piper.

- Burkhardt, C. (2018). Don’t be a robot. Midas Management.

- Camfferman, K., & Zeff, Stephen A. (Ed.). (1994). Twentieth-Century accounting thinkers. Routledge.

- Chambers, A. (1992). Effective internal audits. How to plan and implement. Pitman.

- Chambers, R. (2017). Trusted advisors: Key attributes of outstanding internal auditors. Internal Audit Foundation.

- Drašček, M. (2024). The theory of internal audit – The purpose driven internal audit, EDPACS. EDPACS, 1–10. Published online: 06 February. https://doi.org/10.1080/07366981.2024.2314798

- Edmondson, A. C. (2019). The fearless organization. Wiley.

- Emett, S. A., Eulerich, M., Lipinski, E., Prien, N., & Wood, D. A. (2023, July 18). Leveraging ChatGPT for enhancing the internal audit process – A real-world example from a large multinational company. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4514238

- Eulerich, M., & Lenz, R. (2020). Defining, measuring and communicating the value of internal audit. Internal Audit Foundation.

- Eulerich, M., Sanatizadeh, A., Vakilzadeh, H., & Wood, D. A. (2023, November 17). Is it all hype? ChatGPT’s performance and disruptive potential in the accounting and auditing industries. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4452175 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4452175

- Financial Times. (2023). New Bayer chief plans a radically different style to cut bureaucracy. Blog. Retrieved February 12, 2024, from https://www.ft.com/content/1d0112ad-b523-4b78-aaa3-586b1f05ccb6

- Flint, D. (1988). Philosophy and principles of auditing: An introduction. Macmillan.

- Frei, F., & Morriss, A. (2020, May–June). Begin with trust. Harvard Business Review.

- Gadamer, H.-G. (2004). Truth and method (rev. ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. [First published in 1960 in German, as Wahrheit und Methode.].

- Garofalo, C., & Geuras, D. (2006). Common ground, common future: Moral agency in public administration, professions, and citizenship. CRC Press.

- Garyn, H., & McCafferty, J. (2023, November 13). Seven characteristics of internal audit leaders of the future. Internal Audit, 360. https://internalaudit360.com/seven-characteristics-of-internal-audit-leaders-of-the-future/

- Hinssen, P. (2017). The day after tomorrow. https://nexworks

- IIA. (2017). International standards for the professional practice of internal auditing. IIA

- IIA. (2024a). Global internal auditing standards. IIA.

- IIA. (2024b). Report on the standard-setting and public comment processes for the global internal audit standards. IIA.

- IPPF Oversight Council. (2022). Framework for setting internal audit standards in the public interest. IIA.

- Jacka, M. (2019). Trying to define trusted advisor, blog, April 16, a publication of TheIIA.Org. https://internalauditor.theiia.org/en/voices/20192/trying-to-define-trusted-advisor/

- Kappler, E. (1988, März). Nur die Praxis enthält die ganze Theorie. Interview in: Perspektiven, Heft 12, 36–40.

- Korine, H. (2020). Preventing corporate governance failure. Haupt Verlag.

- Kultgen, J. (1988). Ethics and professionalism. Pennsylvania University Press.

- Lenz, R. (2013, 01). Insights into the effectiveness of internal audit: A multi-method and multi-perspective study [ Doctoral Thesis, Université catholique de Louvain - Louvain School of Management Research Institute].

- Lenz, R. (2017). Time is ripe to revolutionize the audit. EDPACS, 56(4), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/07366981.2017.1380479

- Lenz, R., & Chesshire, J. (2023). Rethinking internal audit: Governance needs gardening. EDPACS, 68(3), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07366981.2023.2255432

- Lenz, R., & Hahn, U. (2015). A synthesis of empirical internal audit effectiveness literature pointing to new research opportunities. Managerial Auditing Journal, 30(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-08-2014-1072