Abstract

Ningbo in the southeastern Chinese province of Zhejiang emerged as a city during the Tang dynasty (618–907), and was known at that time as Mingzhou. On the question where the administrative, political and economic center of the Ningbo region was located between 738 and 821 the various source materials either remain silent or tell very different stories. In this study I re-visit and discuss the three main theories using textual analysis combined with archaeological evidence. On the basis of textual and recent archaeological evidence this study argues that today’s location of Ningbo at Sanjiangkou was the political, economic and cultural center of Eastern Zhejiang over 400 years earlier than previously thought. This clearly demonstrates the geographical and economic importance of the location at Sanjiangkou and the political stability of the region from the end of the Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420).

Ningbo in the southeastern Chinese province of Zhejiang emerged as a city during the Tang dynasty and was known at that time as Mingzhou 明州.Footnote1 Its port came to play a decisive role in the Maritime Silk Road and for the economy of the region in the ages to follow, but the origin of Mingzhou is somehow shrouded in the mist of the past. This is the more remarkable as, in contrast to most other regions in China, local gazetteers (fangzhi 方志 or difangzhi 地方志) on the Ningbo region are extant from as early as 1169. The historical sources all agree that the year 738 marked the establishment of the prefecture of Mingzhou in the Ningbo region and that in 821 the prefectural seat, also called Mingzhou, was set up at Sanjiangkou 三江口, the city center of Ningbo today. On the decisive question where the administrative, political and economic center of Mingzhou was located between 738 and 821, on the other hand, the various sources either remain silent or tell very different stories.

In this paper, I follow up these stories in order to dispel some of the mist and to shed new light on the historical development of Ningbo before 821. I will re-visit and discuss the three main theories that are based on different interpretations of local gazetteers as main primary source materials, but also consult sources of the traditional type such as standard histories (zhengshi 正史) and digests of government institutions (huiyao 會要). I will then compare the textual evidence of each of the three theories with recent archaeological evidence provided in Chinese archaeological excavation reports.

This study provides insights into the challenges, problems and opportunities of studying Chinese local history using local gazetteers. It shows that textual research combined with archaeological evidence can contribute greatly to tackle questions that on the basis of primary text materials alone are difficult to answer. The study further shows that according to textual and recent archaeological evidence the administrative center of Eastern Zhejiang at Sanjiangkou is over 400 years older than previously thought. Sanjiangkou was not only the location of the seat of the prefecture of Mingzhou (Ningbo) right from the beginning in 738 but also the political, economic and cultural center of the Ningbo region already from the end of the Eastern Jin dynasty. This clearly demonstrates the geographical and economic importance of the location at Sanjiangkou and the political stability of the region from the end of the Eastern Jin.

1. Introduction

By way of a more detailed introduction to the study I shall now outline the geographical features and the historical development of the Ningbo region. Ningbo is situated to the south of the Yangzi delta, in the eastern part of Zhejiang in the middle of China’s east coast. To the north the Ningbo region borders on the Hangzhou bay and to the east its Zhoushan archipelago is surrounded by the waters of the East China Sea. The regional landscape is dominated by mountains and hills. The mountain range of the Siming 四明 mountains marks the western and the foothills of the Tiantai 天台 mountain range the southern boundaries of the Ningbo territory. The two large rivers of the region, the Fenghua River 奉化江 and the Yuyao River 餘姚江, both originate from the Siming mountains, flow down the Ningbo plain, converge at the present location of Ningbo at Sanjiangkou (literally “three-river mouth”) and flow into the East China Sea as Yong River 甬江.

Sanjiangkou, today at the conjunction of the three city districts of Haishu 海曙, Jiangbei 江北 and Yinzhou 鄞州 of the modern city of Ningbo, was an ideal location for trade. The Yuyao River connected Sanjiangkou to North China via the Grand Canal at Hangzhou, the Fenghua river was an inland connection to the South, and the Yongjiang River running through the Baoshan mountains provided convenient access to the East China Sea. Sanjiangkou became an internationally important port on the Maritime Silk Road also for the reason that it was well connected to its hinterland via the extensive inland water transportation network.

At the beginning of the Sui dynasty (589–618) the three districts of Yinxian 鄞縣, Maoxian 鄮縣 and Gouzhang 句章縣 became merged and were renamed as the major district Gouzhang. At the same time, the district Yuyao 餘姚縣 also came under the jurisdiction of the newly established major Gouzhang district. The names of places can change very often during the course of Chinese history and the same name might refer to different geographical locations or administrative units. To avoid confusion, in this study I refer to the Gouzhang district that was established in 589 as “major” Gouzhang district because it was completely different in size from the previous Gouzhang district and had, in fact, the administrative territory of a prefecture.Footnote2

The Ningbo region was under the administration of the major Gouzhang district until 621 when the major Gouzhang district, excluding Yuyao district which became Yaozhou 姚州, was renamed into Yinzhou prefecture. This was the first time in history that a prefecture was established in the Ningbo region and Sanjiangkou became the administrative seat of the newly established Yinzhou prefecture. But already in 625, Yinzhou ceased to exist as a prefecture and its administrative territory, as large as that of three individual districts, came under the administration of Maoxian district, which was subordinated to Yuezhou prefecture 越州.Footnote3 To avoid confusion, I again call this newly established district “major” Maoxian district as it was completely different and much larger than both the former and the latter Maoxian district. The major Maoxian district was abolished in 738 when in its place Mingzhou prefecture was set up.Footnote4 The reasons for the failure of the Ningbo region to maintain the status of a prefecture are manifold. However, it seems that at the beginning of the Tang dynasty the Ningbo Plain was not yet sufficiently developed which was mainly due to an unsustainable supply with freshwater, an essential prerequisite for a growing urban population and agricultural production. The Fenghua, Yuyao and Yong rivers were all exposed to the sea tide and as a result their water was of brackish nature. Frequent flooding and a limited availability of freshwater were a major obstacle to the urban and agricultural development of Ningbo and the surrounding area.Footnote5

The year 738 marked a turning point in the history of the Ningbo region because in this year it permanently achieved the status of a prefecture in its own right and was no longer administered by Yuezhou prefecture.Footnote6 The newly established prefecture Mingzhou was named after the mountain range of the Siming mountains at its western border.Footnote7 Mingzhou prefecture had four districts under its administration: The district Cixi 慈溪 in the north was on the territory of the pre-589 Gouzhang district and Fenghua district 奉化縣 was the new name for the former Yinxian district in the southwest of the Ningbo region.Footnote8 Wengshan district 翁山縣 was on the territory of modern Zhoushan island and as before the pre-589 district Maoxian in the west was the fourth district.

The historical and geographical sources remain silent, are sometimes vague or in some instances even contradictory when it comes to the question of the location of the administrative seat of Mingzhou prefecture after its establishment in 738. Due to rich and unequivocal textual evidence there are no doubts about the relocation of the prefectural seat of Mingzhou to Sanjiangkou in 821. It is mentioned in the gazetteers written during different dynasties and also in sources like one of the official histories of the Tang dynasty the Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書, the Tang Huiyao 唐會要, a collection of essential documents and regulations of the Tang dynasty or the Taiping huanyu ji 太平寰宇記, a comprehensive geography written during the late tenth century.Footnote9 It is beyond the scope of this study to discuss in detail the complex relations of imitation, quotation and correction between the different historical primary source materials. Suffice it to say that early geographical sources like the Taiping huanyu ji are particularly significant for this study because the first three local gazetteers of the Mingzhou region have been lost and some of the contents might be quoted and preserved in these sources.Footnote10

On the question where the administrative seat of Mingzhou was located between 738 and 821 the opinions of the historical sources are widely divided. There are three different main theories about the location of the prefectural seat during this time based on divergent interpretation of the source materials at hand. In this paper I discuss these three different theories and juxtapose them with recent archaeological evidence provided in Chinese archaeological excavation reports.

2. Source Materials

In China “local history” is closely associated with local gazetteers. Local gazetteers were intended to serve the practical purpose of supplying incoming officials with a guide to the locality, especially its administrative profile and geography. These gazetteers of districts, prefectures and other local administrative divisions were often compiled by the members of the local elite working under the sponsorship of a local official. The Chinese fangzhi are one of the most important and unique sources for the study of Chinese history, especially local history, since they contain copious information on local places, including their geography, place names, administration, economy, culture, dialects, officials and local elites and their publications which no other sources have. The Qing historian and philosopher Zhang Xuecheng 章學誠 (1738–1801) was the first to discuss fangzhi as an important branch of historical writing on a par with the national or dynastic histories.Footnote11

Originally the central government required local officials to send in basic information on their localities (fang 方) which was then used as basis for empire-wide maps and gazetteers. From the Eastern Han onwards (25–220), these predecessors of the local gazetteers were called Tujing 圖經 (Maps and Records). The Qiandao Siming tujing 乾道四明圖經 written in 1169 was lost but fortunately the complete content can be recovered from another source contained in the collections of the oldest private library in China, the Tianyige Museum in Ningbo.Footnote12 No more than 30 of just over 1,000 local gazetteers compiled during the Song dynasty survived. Three of these 30 surviving Song gazetteers, the Qiandao Siming tujing, the Baoqing Siming zhi 寶慶四明志 completed in 1227 and the Kaiqing Siming xuzhi 開慶四明續志 from 1259, are from the Ningbo region. Only 11 from 60 local gazetteers compiled during the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) are still extant. Two out of the eleven, the Yanyou Siming zhi 延祐四明志 from the Yanyou 延祐 era (1314–1320) and the Zhizheng Siming Xuzhi 至正四明續志 from the Zhizheng 至正 era (1341–1367), are both from the Ningbo region. In terms of primary source materials the Ningbo region provides a unique opportunity to study local history because, in contrast to other regions in China, many of the local gazetteers from the Song dynasty onwards survived. For his study on Ningbo’s neighboring prefecture of Wuzhou 婺州, known from the Ming as Jinhua prefecture 金華府, for example, Peter Bol, with one exception of a prefectural gazetteer from 1480, had mainly sixteenth century gazetteers available to him.Footnote13

In addition to the historical and geographical primary source materials I make use of secondary literature such as archaeological reports. With the exception of an English article written by Yoshinobu Shiba back in 1977 all source materials are in Chinese. Whereas in the Chinese sources the problem of the location of the administrative seat of Mingzhou prefecture after its establishment in 738 is discussed down to every nut, bolt and screw on the basis of textual and archaeological evidence and opinions are widely divided, Shiba mentions the issue only in passing. He takes it for granted that the seat of Mingzhou in 738 was already located at the present location at Sanjiangkou without providing any textual evidence.Footnote14

3. The Three Main Theories on the Location of the Prefectural Seat of Mingzhou After 738

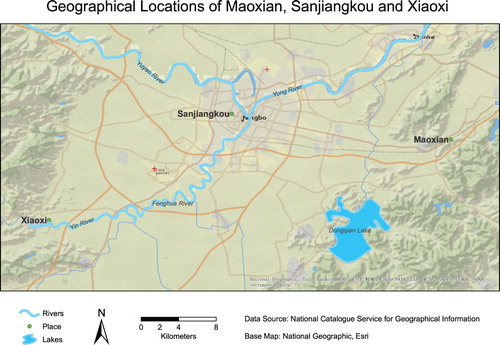

The three main theories claim that according to their interpretation of the historical and geographical primary source materials the prefectural seat of Mingzhou in 738 was established at (1) the market town of Xiaoxi 小溪鎮 (2) the old district seat of Maoxian district and (3) Sanjiangkou, the present location of Ningbo.

Source: Map created by Elsie Zhou, University of Nottingham Ningbo China: Library, Research and Learning Resources.

3.1. The “Xiaoxi” Theory

According to the “Xiaoxi” theory, the market town of Xiaoxi located at the modern town of Yinjiang 鄞江鎮 became the district seat of Gouzhang after its relocation in 400 CE and also the administrative seat of Mao district from 625 onwards. In 738 Xiaoxi became the location of the first prefectural seat of Mingzhou and it continued to be the administrative seat of Maoxian district. In 771 the administration of Maoxian district moved to Sanjiangkou, the location of today’s city of Ningbo. Finally, in 821 the prefectural seat moved to Sanjiangkou and the Maoxian district seat was moved back to Xiaoxi instead.

This theory is the most recent one and has the most supporters; most of the local gazetteers since the Ming dynasty advocate this theory.Footnote15 According to “A General History of Ningbo”, the most recent comprehensive history of Ningbo, at the beginning of the Sui dynasty (589–618) the political and economic center of the Ningbo region was at Xiaoxi, the administrative seat of the district of Gouzhang.Footnote16 The exhibition on Ningbo local history in the Ningbo Municipal Museum also faithfully follows this theory.

According to this theory, Xiaoxi was located at the modern town of Yinjiang in the city district Haishu of Ningbo, direct line about 20 km southwest from modern Ningbo in the Ningbo plain at the foothills of the Siming mountains in the valley of the river Yinjiang 鄞江. The Yinjiang River, a tributary of the Fenghua River, had its origin in this mountain range and running through Xiaoxi on its way along the Ningbo plain it ensured a stable supply of water.Footnote17 Due to the abundant supply of water, Xiaoxi had turned into an important crop-growing area in the Ningbo basin and it was particularly suitable for growing mulberries for sericulture.

3.1.1.Textual Evidence for the “Xiaoxi” Theory

According to “A General History of Ningbo,” Sanjiangkou continued to be the location of the administrative seat after 625,Footnote18 although a Qing period Ningbo prefectural gazetteer claims that Maoxian district moved its administrative seat back to its former location between Maoshan Mountain 鄮山 and Eyuwang Mountain 阿育王山.Footnote19 For the modern Ningbo gazetteer, however, there is no doubt that in 738 the prefectural seat of Mingzhou and the administrative seat of Maoxian district were at Xiaoxi.Footnote20 The administrative center of the region had been at Xiaoxi since around 400 CE and with a short intermezzo from 621 to 625, stayed there until 771:

771年 (大歷六年) 廢翁山入鄮縣,鄮縣治由小溪徙三江口,即前鄞州治 … 821年 (長慶元年), 州治與縣治互易。明州刺史韓蔡以州治小溪地形卑隘,向浙江東道觀察使薛戎請准,徙州治於鄮縣縣治所在地三江口,至是州治一直未變。同時遷鄮縣治於小溪 … 909年 … 改鄮縣為鄞縣 … 縣治再次移至三江口於州治同設。Footnote21

In 771, Wengshan district was abolished and its administrative territory integrated into Maoxian district. The administrative seat of Maoxian was moved from Xiaoxi to Sanjiangkou, the location of the former prefectural seat of Yinzhou … In 821 the administrative seats of Mingzhou and Maoxian exchanged their locations. Because of the low-lying and confined geographical position of the prefectural seat at Xiaoxi the prefect of Mingzhou Han Cha petitioned to Xue Rong, the Surveillance Commissioner of Eastern Zhejiang circuit to move the prefectural seat to the location of the district seat of Maoxian at Sanjiangkou. The petition was approved [by the court] and the prefectural seat remained to be at Sanjiangkou from this time onwards. At the same time the district seat of Maoxian was relocated back to Xiaoxi … In 909 … Maoxian district was renamed into Yinxian district … and the district seat was once again moved to Sanjiangkou, the same location as the prefectural seat [of Mingzhou].

Discussions about the location of the administrative seat of Mingzhou between 738 and 821 already started during the Southern Song period (1127–1279) and have never ceased since then. In the preface to the Baoqing Siming Zhi, the second oldest gazetteer of the Ningbo region written in 1227, the challenges of recording the history of Mingzhou prefecture are described as followsFootnote27:

自明置州,至是四百三十二年,而城治之遷徙,縣邑之沿革,人未有知其的者。唐刺史韓察實移州城,石刻尚存,於時且未之見,他豈暇詳。甚哉作者之難,固有俟乎述於後者也。

It is [only] 432 years since Mingzhou prefecture was established and [yet] there is no one who knows about the location of the prefectural seat and the historical development of the local administration anymore. The stone inscription that recorded the relocation of the prefectural seat by the prefect Han Cha during the Tang dynasty still exists but it does not specify the events of that time. How could such events not be engraved in the stele? We [the authors] found the compilation of this book an extremely challenging task and therefore it still remains a task to be accomplished by later scholars.

According to the Baoqing Siming Zhi, during Tang times Xiaoxi was called Guangxi 光溪鎮 and located 40 li or around 22.5 km from Sanjiangkou. During the Song period it changed its name into Xiaoxi and belonged to a township called Gouzhang 句章鄉.Footnote28 The Yuanfeng Jiuyu Zhi does not provide a distance but mentions it as market town of Yinxian district, the name for Maoxian district from 909 onwards.Footnote29 In contrast, the Qiandao Siming Tujing locates the township of Gouzhang 60 li or about 34 km to the south of Sanjiangkou, yet according to the Ming gazetteer of Ningbo this also refers to Xiaoxi, the modern town of Yinjiang.Footnote30 The modern gazetteer of Ningbo city agrees with the distance mentioned in the Baoqing Siming zhi and locates Xiaoxi at today’s town of Yingjiang 鄞江鎮 of the district Yinzhou of Ningbo city about 20 km southwest of Sanjiangkou. According to this gazetteer from 1995, the first location of Xiaoxi was less than one kilometer to the east of modern Yinjiang at a place called Guchengfan 古城畈. Later on it moved to the foot of Fenghuang Mountain 鳳凰山, the location of a brewery today and finally to somewhere close to the modern village of Xuanci 懸慈村.Footnote31 The last location was apparently first mentioned in the Yongzheng gazeetter of Ningbo prefecture, and the Siming Tuoshan Tujing by the late Qing scholar Yao Xie 姚燮 confirms the location of Xiaoxi at Xuanzi 懸鎡, which is modern Xuanci 懸慈.Footnote32 The Jingzhilu 敬止錄 written by Gao Yutai 高宇泰 during the late Ming period (1368–1644) mentions yet another possible location of Xiaoxi in modern Yinjiang at a place called Gaoshangzhai 高尚宅.Footnote33 The philosopher and historian Huang Zongxi 黃宗羲 (1610–1695) on the other hand locates Xiaoxi yet at another location at a mountain called Shijiushan 石臼山.Footnote34 There is still a temple called Shijiu temple 石臼廟 which is about 18.5 km southwest of Sanjiangkou.

A detailed description of an inspection tour in 1047 of the famous Song period official Wang Anshi 王安石 (1021–1086), who in his young years served as magistrate of Yinxian district, indicates that the location of Xiaoxi of that time could not have been at the modern town of Yinjiang.Footnote35 The description there rather agrees with the location at Shijiushan 石臼山 mentioned much later by the Ming/Qing scholar Huang Zongxi. The textual evidence seems rather to indicate that the town of Xiaoxi had not been located at modern Yinjiang but at a location around 3–4 km to the east of Yinjiang, closer to Sanjiangkou.

3.1.2. Archaeological Evidence for the “Xiaoxi” Theory

Because of the prominence of the “Xiaoxi” theory, extensive and systematic excavation work was undertaken in Yinjiang and the surrounding area. The large-scale project started in 2011 and lasted for more than three years.Footnote36 Archaelogical excavations atFootnote37:

Fenghuang mountain 鳳凰山 only revealed remains of private kilns from the Ming and Qing periods onwards that were used by the local populace. Archaeologists did not find any remains that would indicate a previous city or administrative seat. However, they had to admit that excavations could only be conducted in a very limited way due to building development in recent years.

Gaoshangzhai 高尚宅 did not have to deal with such obstructions as it is an area mainly under agricultural cultivation. Objects found were also mainly from the Ming and Qing periods but none from the Tang or earlier periods. No archaeological evidence was found that would point to this place as possible location for Maoxian district or the prefectural seat during Sui and Tang times.

Xuanci village 懸慈村 also did not produce any evidence that would suggest the location of a former administrative seat.

Guchengfan 古城畈 showed that it can also be ruled out as the location of the prefectural seat of Mingzhou because the archaeologist team found no archaeological evidence from the Tang period or before.

The “Xiaoxi” theory hinges entirely on the assumption that Gouzhang was relocated to a place called “Xiaoxi,” but Xiaoxi is only one of the possible locations of the relocated Gouzhang. In addition, the actual location of “Xiaoxi” is a most controversially debated topic. So far there is no definite textual and archaeological evidence that shows that Xiaoxi was the location of Gouzhang after around 400 CE and that is was located at modern Yinjiang or at places like Guchengfan 古城畈, Xuanci 懸慈, or other places that belonged to Yinjiang.

The relocation of the administrative seat of Gouzhang has not only been debated in the local gazetteers but in recent years, these changes in local administration as described by the Ming, Qing, and contemporary Ningbo gazetteers have been challenged by Chinese historians and archaeologists. In his investigation into the historical source materials, the Chinese historian Chen Danzheng 陳丹正 arrives at the conclusion that the Gouzhang district seat was not relocated at the end of the Eastern Jin around 400 CE at all. He also argues that the market town of Xiaoxi at the modern town of Yinjiang has never been the location of an administrative seat of a county or prefecture.Footnote38 However, according to local Ningbo archaeologists, new archaeological evidence found at the former location of Gouzhang indicates that the old seat of Gouzhang must have been relocated around 400 CE, yet so far the archaeological evidence is insufficient to suggest the exact location to where it was relocated.Footnote39 All the same, from the archaeological findings at Yinjiang the archaeologists concluded that Xiaoxi, that is modern Yinjiang, can be ruled out as possible location for Gouzhang.Footnote40 Based on the archaeological evidence excavated during recent years in the Ningbo region and on the evidence in the source materials, local archaeologists suggest that instead of moving to Xiaoxi, there is a high probability that at the end of the Eastern Jin the seat of Gouzhang was moved to the present location of Ningbo, to a location close to present Ximenkou 西門口 in Haishu district of Ningbo city.Footnote41

I also agree that the geographical position of Xiaoxi seems to be too remote to be the political and economic center of this region. Firstly, because water-borne transport was highly inconvenient, but also because the Siming mountains in the hinterland limited space for development and limited access to goods and materials.Footnote42

3.2. The “Old Maoxian District Seat”

According to the “Old Maoxian district seat” theory, the administrative seat of Mingzhou, after its establishment as a prefecture in 738, was set up at the original location of the Maoxian district seat. Maoxian district had been established during the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) and had its district seat between Maoshan Mountain and Eyuwang Mountain which was about 17 km to the east of Sanjiangkou, the city center of modern Ningbo.Footnote43 In 738 the district seat of Maoxian and the prefectural seat of Mingzhou were both located at this original location of Maoxian district in close distance of each other (鄮為附郭縣). In 771 the administrative seat of Maoxian district, the prefectural seat of Mingzhou, or both of them were relocated to a location in the vicinity of today’s Ningbo city at Sanjiangkou. In 821 the administrative seats of Mingzhou and Maoxian district exchanged their locations. Mingzhou moved to the administrative seat of Maoxian district and Maoxian district moved to the former location of Mingzhou’s prefectural seat.

3.2.1. Textual Evidence for the “Old Maoxian District Seat” Theory

This theory is mainly based on the interpretation of a passage in the oldest surviving local gazetteers of the Ningbo region, the Qiandao Siming Tujing written in 1169Footnote44:

高祖武德四年始析句章縣為鄞州。八年廢鄞州為鄮縣,隸越州。明皇開元二十六年採訪使齊澣始復奏請為州,以境內有四明山,故號州為明 … 舊治鄮縣,今阿育王山之西,鄮山之東,城郭遺址猶存。代宗大歷六年三月,海寇袁晁作亂於翁山,而鄮縣久弗能復,乃移治鄞,鄞東取鄮山財三十里 … 穆宗長慶元年,浙東觀察使薛戎上書,明州北臨鄞江,地形卑隘,請移郡於鄮縣置,其元郡城近南高處卻安縣。從之,而移否莫得而知。

In 621 [major] Gouzhang district was restructured and named into Yinzhou prefecture.Footnote45 In 625 Yinzhou prefecture was abolished and [major] Maoxian district, under the administration of Yuezhou prefecture, was set up instead. In 738 the Circuit Intendant Qi Huan petitioned to the court to have once again a prefecture established. The prefecture was named Mingzhou after the Siming mountains in its territory … Formerly [this region] had been administered by Maoxian district which had its administrative seat in the west of Eyuwang Mountain and in the east of Maoshan mountain. The ruins of the city walls are still there. In 771 the pirate Yuan Chao started a rebellion in Wengshan district (modern Zhoushan island) and for a long time it could not be subdued in Maoxian district. For this reason the administrative seat was moved to Yinxian, which was only 30 li (around 17 km) to the west of Maoshan mountain … In 821, Xue Rong, the Surveillance Commissioner of Eastern Zhejiang circuit petitioned in a memorial to move the prefectural seat to the location of the district seat of Maoxian district [at Sanjiangkou] because of the inferior geographical position of the narrow river valley of the Yinjiang river. He also petitioned to relocate the administrative seat of Maoxian district to an elevated location in the south of the former prefectural seat; however, it remains unknown whether the district seat was moved or not.

州治鄮縣在阿育王山之西,鄮山之東。自鄞州廢為鄮縣,乃在今州治非古鄮治矣。

[The first administrative seat of Maoxian district was set up] in the west of Eyuwang mountain and the east of Maoshan mountain. When Yinzhou prefecture was abolished and Maoxian district set up instead, the administrative seat continued to be at the present prefectural seat [at Sanjiangkou] and was not relocated to the old seat of Maoxian district.

Considering these circumstances, the first part of the sentence of the passage above (州治鄮縣) poses a problem for translation. To translate it as “the prefectural seat of Mingzhou at the old district seat of Maoxian” would be contradictory. I translated it as “the first administrative seat of Maoxian district was set up … ” because it seems from the context of the Qiandao Siming Tujing and the Baoqing Siming zhi the first character appears to be written wrongly. A similar passage in the Baoqing Siming zhi reads as followsFootnote50:

鄞縣東三十里,阿育王山之西,鄮山之東,有古鄮城初鄮縣治也。

The old city of Maoxian, the original location of the administrative seat of Maoxian district, is 17 km to the east of Yinxian district, in the west of Eyuwang mountain and in the east of Maoshan mountain.

舊治鄮縣,今阿育王山之西,鄮山之東,城郭遺址猶存。

Formerly [this region] had been administered by Maoxian district which had its administrative seat in the west of Eyuwang mountain and in the east of Maoshan mountain. The ruins of the city walls are still there.

According to the Baoqing Siming zhi, the seat of Maoxian district was not moved back to the old location in 625,Footnote52

According to the Baoqing Siming zhi and the Yuanhe Junxian Tuzhi from 813, the administrative seat of Mingzhou and Maoxian district were in close proximity of each other at a location in the vicinity of Sanjiangkou,Footnote53

In the context of the Baoqing Siming Zhi and the Qiandao Siming Tujing the phrase “州治鄮縣” is contradictory,

I conclude that 州治鄮縣 might have been miswritten and should be written 初治鄮縣. To have miswritten characters is quite common in the local gazetteers and to write it in this way would be consistent with 舊治鄮縣 as well as 有古鄮城初鄮縣治也 cited above.Footnote54

The Qiandao Siming Tujing and some other local gazetteers claim that because of the rebellion of Yuan Chao袁晁 in the Ningbo region in 771, the administrative seat of Maoxian district and/or the prefectural seat of Mingzhou moved from their former location between Eyuwang mountain and Maoshan mountain, around 17 km to the east of modern Ningbo, to Sanjiangkou, the present location of Ningbo.Footnote55 This apparently is an incorrect judgement, because according to the Xin Tangshu and the Zizhi tongjian the nearly 200,000 men-strong peasant rebel army of Yuan Chao had wreaked havoc in the Ningbo region already in 762 before the imperial troops could finally put down the rebellion in the following year.Footnote56 This implies that the rebellion of Yuan Chao could not have been the immediate reason for a relocation of the administrative seats because in 771 the rebellion was already over for almost ten years. The Qianlong Yinxian zhi from the Qing period also point-blank contradicts the description in the Qiandao Siming tujing.Footnote57 One might hypothesize that because of the lesson learnt from the rebellion of Yuan Chao, the administrative seat was moved closer to the sea to Sanjiangkou in 771 to be better prepared for and to defend against possible future dangers from the sea. However, the Yuanhe Junxian tuzhi from 813, the earliest extant geographical work covering the whole empire, and other early geographical works like the Taiping huanyu Ji and the Yuanfeng jiuyu zhi do not mention a relocation of the prefecture of Mingzhou or Maoxian district in 771. The official histories of the Jiu Tangshu and the Xin Tangshu also make no mention of such an event.Footnote58 On the contrary, most of these sources mention the relocation of Mingzhou in 821. This point, in conjunction with the fact that the Baoqing Siming zhi written only 60 years after the Qiandao Siming tujing contradicts this first extant gazetter of the Ningbo region, makes the theory of relocation in 771 even more questionable.

The Baoqing Siming zhi cites an old gazetteer who claims that in 771 the prefectural seat of Mingzhou was moved to a location at the former Sun Lake 日湖. During Song times (960–1279) the Sun Lake was described as being located in a district of the “outer city” 羅城 of Mingzhou called Xiaojiangli 小江里, two li or just over 1 km to the south of the Song prefectural seat of Mingzhou. Again, the Baoqing Siming Zhi doubts this assertion because of insufficient textual evidence (未之考也).Footnote59 The Baoqing Siming does not mention which old gazetteer it is referring to and as mentioned above I could not find any evidence for this assertion in older gazetteers and geographical works, such as the Yuanhe Junxian Tuzhi. The third treatise on geography in juan 40 of the Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 describes the changes in local administrative in the Ningbo region as follows:Footnote60

鄮漢縣,屬會稽郡。至隋廢。武德四年,置鄞州。八年,州廢為鄮縣,屬越州。開元二十六年,於縣置明州。

The district Maoxian, established during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), was under the administration of Kuaiji commandery. Maoxian district was abolished at the beginning of the Sui dynasty (589–618). In 621 Yinzhou prefecture was established. In 625 Yinzhou prefecture was abolished and Maoxian district, which was set up in its place, was put under the administration of Yuezhou prefecture. In 738 the prefecture of Mingzhou was established to replace Maoxian district.

Both interpretations are valid and consistent with the historical development in the Ningbo region but seen from the context I prefer the latter interpretation and translation. They, however, cannot be regarded as evidence for the “Old Maoxian district seat” theory because the decisive question here is rather where the administrative seat of Maoxian district was located at in 738.

So far the textual evidence for the “Old Maoxian district seat” theory is rather unsubstantial and not persuasive, but on the other hand textual evidence seems rather to point at a location at Sanjiangkou as the seat of Maoxian district in 738. The relocation of the ancestral temple of Maoxian district to a location at Sanjiangkou in 699 is another piece of evidence that contradicts the “Old Maoxian district seat” theory and substantiates the claim of the Baoqing Siming Zhi that the seat of Maoxian district was not moved back to the old location in 625 but stayed at Sanjiangkou.Footnote61 According to this gazetteer, the Baolang temple (鮑郎廟), also known as Lingying temple, was located 2.5 li or 1.4 km to the south of the “inner city,” the prefectural seat of Mingzhou.Footnote62

3.2.2. Archaeological Evidence for the “Old Maoxian District Seat” Theory

The General History of Ningbo and the modern gazetteer of Ningbo city assert that the geographical location of the old district seat of Maoxian district must have been in the vicinity of the King Asoka Temple 阿育王寺 in the area of today’s Tong’ao village 同嶴村 and Baozhuang township 寶幢鄉 in Wuxiang town 五鄉鎮, in the Yinzhou district of Ningbo city.Footnote63 This assertion is most probably based on archaeological evidence that points at modern Wuxiang town as center of the old Maoxian district. Tombs from the Eastern Han to the Eastern Jin dynasties (25–420 CE) were found at Shayan village 沙堰村 of the township of Baozhuang 寶幢鄉, at a place called Caigoutang 蔡溝塘 in the town of Dongwu 東吳鎮 and Meixulongshan 梅墟龍山. Judging by the burial objects found during the first excavation in 1984 in the well-preserved tombs M3 and M7 at Shayan village, the tombs at this site date back to the period between the Eastern Han to the Western Jin (25–316 CE). The tomb M3 from the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220) contained a funerary urn, also called “soul jar” 魂瓶, which had figures molded after the people of the tribes of the Western Regions of the overland Silk Road attached to it.Footnote64 In 2006 local archaeological teams found five tombs from the Western Jin dynasty (265–316) in the same area at Caigoutang in the township of Dongwu.Footnote65 Two years later, in 2008, 3 tombs dated back to the Eastern Jin (317–420) were excavated there at the site of Meixulongshan.Footnote66 The archaeological findings are mainly from pre-Tang times and although they suggest that the old Maoxian district seat was in this location they do not suggest that it was still the administrative seat of Maoxian district let alone the prefectural seat of Mingzhou during the Tang dynasty. According to the available excavation reports, only one Tang dynasty tomb from 876 CE was found in this area. The other tomb found at this site and other 8 tombs unearthed in 2013 at Fenghuangshan 鳳凰山 site at the same location are all from the Jin Dynasty or earlier.Footnote67 The discovery of so far around 100 tombs was often accidental, mainly due to construction work and not done in a systematic way. Although excavation work has not finished yet, at the moment there is no archaeological evidence, such as remains of city walls, that would indicate that Mingzhou prefecture and Maoxian district had their administrative seats in this area during the Tang period.

3.3. The “Sanjiangkou” Theory

According to the “Sanjiangkou” theory the prefectural seat of Mingzhou, right from its establishment as prefecture in 738, was located somewhere in the vicinity of today’s Ningbo city at Sanjiangkou. The district seat of Maoxian and the prefectural seat were at the same location and in close distance of each other. In 821 the administrative seats of Mingzhou and Maoxian district exchanged their locations. Mingzhou moved to the administrative seat of Maoxian district and Maoxian district moved to the former location of Mingzhou’s prefectural seat.

3.3.1. Textual Evidence for the “Sanjiangkou” Theory

A passage in the Baoqing Simingzhi 寶慶四明志 strongly supports the “Sanjiangkou” theoryFootnote68:

當時縣治乃今州治,非古鄮治矣 縣南有鮑郎廟,記云:唐聖歷二年縣令柳惠古徙祠於縣,是知初置鄞州已治此,繼廢州為鄮縣,不複在鄮山之東也 開元二十六年即鄮縣置明州,鄮為附郭縣。長慶元年刺史韓察請於朝以縣治為州治,而於舊州城近南高處置縣。

At that time [625 CE] the administrative seat [of the major Maoxian district] was at the location of today’s prefectural seat [at Sanjiangkou] and not at the old seat of Maoxian district. The Baolang temple in the south of [today’s] district seat has the following inscription: In 699 the district magistrate Liu Huigu relocated the ancestral temple to the district seat. We know that when Yinzhou prefecture was established [in 621] the administrative seat was already at Sanjiangkou. When Yinzhou was abolished and the [major] Maoxian district established instead [in 625], the administrative seat was not set up again at Maoshan mountain in the east. In 738 the [major] Maoxian district was abolished and Mingzhou prefecture was established instead, the [minor] Maoxian district as a district of Mingzhou prefecture had its administrative seat within the boundaries of the capital of Mingzhou prefecture. In 821 the prefect Han Cha petitioned to the court to have the prefectural seat set up at the location of the administrative seat of Maoxian district and to have the Maoxian district seat moved to an elevated location in the vicinity of the former prefectural seat.

In 821 the administrative seats of Mingzhou and Maoxian district exchanged their locations. The seat of Mingzhou prefecture moved to the “inner city” 子城 and its prefect Han Cha 韓察 built a wall around it which was around 1,320 meters (420 zhang 丈) in circumference.Footnote73 The still-standing Haishu Tower 海曙樓, commonly known as the drum tower, which is located in today’s Haishu city district of Ningbo, marked the south gate of the inner city. At the same time, the district seat of Maoxian was relocated to the former location of Mingzhou’s prefectural seat, a place in close vicinity and to the south of the “inner city.”

Taking a closer look at the description of events in the Baoqing Simingzhi, however, there seems to be one minor inconsistency. According to the gazetteer of Ningbo prefecture of the Ming dynasty the district magistrate Liu Huigu served as magistrate of Maoxian district during the Dali 大歷 era between 766 and 779 and not around the year 699.Footnote74 The gazetteer of Yinxian district from the Xiangfeng period of the Qing dynasty again mentions the date 699 but refers to the Baoqing Siming zhi as source.Footnote75 Because there is no biography of this official in the gazetteers it is difficult to verify which one is the correct date. In the Baoqing Siming zhi, the description of the Lingying temple 靈應廟, another name by which the Baolang temple was known, also gives the year 699 as the date when the temple was moved to the present location of Ningbo at Sanjiangkou.Footnote76

The Yuanhe junxian tuzhi agrees that the administrative seats of Maoxian district and Mingzhou prefecture were located at the same place in close vicinity to each other.Footnote77 In sharp contrast to the “Xiaoxi” theory this primary source locates the old city of Gouzhang, not at Xiaoxi, modern Yinjiang, but as one li or about 565 meters to the west of the prefectural seat of Mingzhou at Sanjiangkou.Footnote78 Given the textual evidence from the Yuanhe junxian tuzhi and the Baoqing Siming zhi, it does not seem appropriate to locate both administrative seats at very different locations as some proponents of the “Xiaoxi” as well as the “Old Maoxian district seat” theories do. The Yuanhe junxian tuzhi also claims that from 625 onwards Maoxian district had its administrative seat at this location, which also used to be the administrative seat of Yinzhou prefecture.Footnote79

The Yuanhe junxian tuzhi from 813 is particularly relevant and even authoritative when it comes to the question of the location of the prefectural seat of Mingzhou before 821. Its author, Li Jifu 李吉甫 (758–814), was chief administrator (長史) of Mingzhou between 792 and 794.Footnote80 For this reason he was very familiar with the local history of Mingzhou and its historical geography. Li Jifu describes the location of Mingzhou as followsFootnote81:

句章古城,在州西一里。

鄮縣,上,郭下。大海,在縣東七十里。

奉化縣,上。北至州六十里。

慈溪縣,上。東南至州七十里。

The old city of Gouzhang is one li to the west of the prefectural seat [of Mingzhou].

The large district Maoxian is located within the “outer city” of Mingzhou. The sea is 70 li to the east of the district seat.

The large district Fenghua is located 60 li to the south of the prefectural seat [of Mingzhou].

The large district Cixi is located 70 li to the northwest of the prefectural seat [of Mingzhou].

Li Jifu finished writing the Yuanhe junxian tuzhi in 813, and therefore the prefectural seat of Mingzhou had not moved to the “inner city” yet, this only happened in 821. But what actually was the exact location of Mingzhou in 813? The Taiping huanyu ji written after the Yuanhe junxian tuzhi in the late tenth century and after the relocation of the prefectural seat of Mingzhou to the “inner city” in 821 provides the exact same data for the location of Mingzhou as the Yuanhe junxian tuzhi.Footnote84 This provides another striking argument against the “Old Maoxian District” and “Xiaoxi” theories. The location of the prefectural seat of Mingzhou in 813 was apparently already at Sanjiangkou and only changed slightly in 821. If the prefectural seat would have moved to Sanjiangkou from the original district seat of Maoxian at Maoshan Mountain or from Xiaoxi, the modern town of Yinjiang the data for the location of Mingzhou in the Taiping huanyu ji would certainly have been very different from the data provided in the Yuanhe junxian tuzhi.

3.3.2. Archaeological Evidence for the “Sanjiangkou” Theory

In 1995 local archaeologists started an excavation project at the eastern pagoda of the Tang-period Guoning temple 國寧寺 in Ningbo and unearthed many objects from the Eastern Han and Jin periods like pan tiles, celadon stoneware jars with four lugs, celadon oil lamps, celadon bowls, and other objects. This archaeological site is located only about 210 meters to the west of the south gate of the Tang period “inner city” of Ningbo, today’s drum tower. The archaeological evidence shows that before the city of Mingzhou was founded during Tang times, the area of Ximenkou of Ningbo city was already densely populated and advanced architectural structures had already been built there.Footnote85 Based on these archaeological findings and more evidence excavated during the last years in the area of Ningbo and on the evidence in the source materials, local archaeologists suggest that instead of moving to Xiaoxi, there is a high probability that at the end of the Eastern Jin the seat of Gouzhang was moved to the present location of Ningbo, to a location close to present Ximenkou 西門口 in Haishu district of Ningbo city.Footnote86

Apart from the archaeological evidence, the area outside the former west gate of the outer city wall of the Tang period Ningbo (Ximenkou 西門口) was allegedly also the location where Liu Laozhi 劉牢之 had built a defensive wall during the rebellion of Sun En 孫恩 around 400 CE. This wall was called “bamboo wall” 筱牆 by the local people and served the purpose of defending Sanjiangkou against bandits and pirates.Footnote87 On the basis of these events, this area of Ningbo is still called Xiaoqiangxiang 筱牆巷, probably one of the oldest place names of modern Ningbo city. As this place already had a wall it obviously appears to be an ideal location for relocating Gouzhang after its destruction during the rebellion of Sun En.

4. Conclusion

The Ningbo region provides a unique opportunity to study local history because primary source materials, in particular local gazetteers are extant from as early as 1169. Yet instead or rather because of this rich coverage in first-hand literature, discrepancies and inconsistencies emerged between the local gazetteers from the different dynasties. One of the most intensely discussed issues in the local history of Ningbo is the location of the prefectural seat of Mingzhou between 738 and 821. It will remain a mystery why this decisive change in the local administration of the Ningbo region was not recorded in detail. The discussion of this problem already started during the Southern Song period (1127–1279) and has never ceased since then and the theories have become even more complex and contradictory. This study shows that the Song/Yuan gazetteers promote the “Sanjiangkou” or “Old Maoxian District” theories whereas the Ming/Qing gazetteers follow the “Xiaoxi” theory. This is an astonishing result because in the gazetteers written before the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) there is no textual evidence at all that would support the “Xiaoxi” theory.

By investigating in detail the three main theories and by analyzing the textual evidence for these theories this paper reveals the complexity of the problem and it shows that an approach that combines textual and archaeological evidence can be instrumental for tackling the problem at hand. The most prominent of the three theories, the “Xiaoxi” theory, is the most recent one and has the most supporters. The most comprehensive history of Ningbo from 2009 and the exhibition on Ningbo local history in the Ningbo Municipal Museum advocate the “Xiaoxi” theory.Footnote88 An analysis of the textual and archaeological evidence for the “Xiaoxi” theory, however, shows that Xiaoxi, i.e. modern Yinjiang, can be ruled out as possible location for the relocated Gouzhang around 400 and for Mingzhou in 738.

This study also shows that the textual and the archaeological evidence favors the “Sanjiangkou” theory. On the basis of the rich evidence available so far it seems highly probable that Gouzhang was relocated to the present location of Sanjiangkou already around 400 CE after its destruction during the rebellion of Sun En. This would mean that all the changes in location of the administrative seats of Mingzhou and Maoxian district took place within the Sanjiangkou area, or in other words in the area of the old city center of modern Ningbo. The evidence suggests that the administrative center of Eastern Zhejiang at Sanjiangkou is over 400 years older than previously thought. Evidently Sanjiangkou was not only the location of the seat of the prefecture of Mingzhou (Ningbo) right from the beginning in 738, but also the political, economic and cultural center of the Ningbo region already from the end of the Eastern Jin dynasty.

The establishment of Sanjiangkou as administrative seat of Mingzhou prefecture marked the beginning of a new era and can be regarded as the official beginning of Mingzhou port. The relocation to the coastal floodplain greatly enhanced the risk of flooding but this was somehow mitigated by the fact that the proximity to the coast provided plenty of opportunities for trade. Sanjiangkou was an ideal geographical location for inland and coastal trade. The Yuyao River connected Sanjiangkou to the Grand Canal and to Yangzhou, Luoyang and Chang’an as well as the commercial centers of Northern China. The Fenghua river was an inland connection to the South and connected Sanjiangkou to its hinterland. This inland trade via the extensive inland water transportation network contributed greatly to the economic development of Ningbo. The location at Sanjiangkou with the short and convenient access to the East China Sea was of strategic importance because the biggest threat for the political stability of the Ningbo region was seen as coming from the ocean. More importantly, it allowed Ningbo to turn into a prosperous and vital port city at the eastern end of the Maritime Silk Road, and although the name of the internationally important port city changed several times from the Tang dynasty up until today, it was not relocated again.

List of Abbreviations of Primary Sources:

| BSZ | = | Baoqing Siming zhi 寶慶四明志 |

| JNFZ | = | Jiaqing Ningbo fu zhi 嘉慶寧波府志 |

| JTS | = | Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 |

| KNFZ | = | Kangxi Ningbo fu zhi 康熙寧波府志 |

| MNFZ | = | Mingdai Ningbo fu zhi 明代寧波府志 |

| NBSZ | = | Ningbo shi zhi 寧波市志 |

| QNFZ | = | Qingdai Ningbo fu zhi 清代寧波府志 |

| QST | = | Qiandao Siming tujing 乾道四明圖經 |

| QYZ | = | Qianlong Yinxian zhi 乾隆鄞縣志 |

| SYSL | = | Song Yuan Siming liuzhi 宋元四明六志 |

| XTS | = | Xin Tangshu 新唐書 |

| YJT | = | Yuanhe junxian tuzhi 元和郡縣圖志 |

| YNFZ | = | Yongzheng Ningbo fu zhi 雍正寧波府志 |

| YSZX | = | Yinzhou Shanshui Zhi xuanji 鄞州山水志選辑 |

Notes on Contributor

Dr. Thomas Hirzel is a historian and a linguist who joined the School of International Communications at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China (UNNC) in September 2020 as Assistant Professor in Digital Humanities and Chinese Studies. He also holds the roles of Associate Director of the Digital Heritage Centre at UNNC and of Research Lead of the Institute of Asia and Pacific Studies Research Priority Area in Ningbo Studies. Thomas is a China scholar with an expertise in the analysis of Chinese primary sources and archival research. His research interests are: The Socio-Economic and Cultural History of Ningbo and the Lower Yangzi Region, Maritime History, Chinese Cultural Heritage and Digital Humanities, Chinese Art History, and Translation and Intercultural Communication in Chinese GLAMs.

Notes

1 I am indebted to two anonymous readers for their helpful comments.

2 Some Chinese historians do the same and call it “Da Gouzhang district” 大句章縣 to distinguish it from the pre-589 Gouzhang district. To call it “Large Gouzhang district” would be misleading as it was one of seven categories to classify districts indicated by the prefix (shang 上). Charles O. Hucker, A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China (Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc., 1985, reprint 1995), 240 (entry 2492).

3 Kangxi Ningbo fu zhi 康熙寧波府志 (hereafter KNFZ), Li Tingji 李廷機, 1683, juan 1, in Qingdai Ningbo fu zhi 清代寧波府志 (QNFZ), Ningbo Shi difangzhi bianzuan weiyuanhui 寧波市地方志编纂委員會 (Ningbo: Ningbo chubanshe, 2011), 1:124; Qiandao Siming Tujing 乾道四明圖經 (hereafter QST), eds. Zhang Jin 張津 et al., completed in 1169, juan 1, in Song Yuan Siming liuzhi 宋元四明六志 (hereafter SYSL), Ningbo Shi difangzhi bianzuan weiyuanhui 寧波市地方志編篡委員會 (Ningbo: Ningbo chubanshe, 2011), 1:35; Jiaqing Ningbo fu zhi 嘉慶寧波府志 (JNFZ), ed. Zhang Shiche 張時徹, 1560, juan 1, in Mingdai Ningbo fu zhi 明代寧波府志 (MNFZ), Ningbo Shi difangzhi bianzuan weiyuanhui 寧波市地方志编纂委員會 (Ningbo: Ningbo chubanshe, 2011), 1:94.

4 Baoqing Siming zhi 寶慶四明志 (hereafter BSZ), ed. Hu Ju 胡榘, completed in 1227, juan 1, in SYSL, 2:25; JNFZ juan 1, in MNFZ 1:93, 105, 113, and 115; KNFZ juan 1, in QNFZ 1:114, 124, 129, and 131.

5 Y.-T. Tang et al., “Aligning Ancient and Modern Approaches to Sustainable Urban Water Management in China: Ningbo as a ‘Blue-Green City’ in the ‘Sponge City’ Campaign,” Journal of Flood Risk Management 11/4 (2018): e12451.

6 JNFZ juan 1, in MNFZ 1:94ff., 105, 113, and 115; KNFZ juan 1, in QNFZ 1:115 and 125; and QST juan 1, in SYSL 1:35.

7 Although it briefly changed its name into Yuyao commandery 餘姚郡 in 742. JNFZ juan 1, in MNFZ 1, 94 and 100; QST juan 1, in SYSL 1:35; Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 (hereafter JTS), Liu Xu 劉昫 (887–946) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1975, reprint 2019), 40.1590; in 758 it was again named Mingzhou (JTS 40.1590) and QST juan 1, in SYSL 1:35. KNFZ juan 1, in QNFZ 1:126 and JNFZ juan 1, in MNFZ 1:94 provide 756 as date for the change in name and KNFZ juan 1, in QNFZ 1:115 and JNFZ juan 1, in MNFZ 1:100 provide it as 757.

8 JNFZ juan 1, in MNFZ 1:105 and 113ff.

9 JTS 16.486; Tang huiyao 唐會要, comp. Wang Pu 王溥 (922–982) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1960, reprint 2017), 71.1273; Taiping huanyu ji 太平寰宇記, ed. Yue Shi 樂史 (930–1007), late tenth century, exact date unknown (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2016), 98.1959.

10 Gong Liefei 龚烈沸, Ningbo gujin fangzhi luyao 寧波古今方志錄要 (Ningbo: Ningbo chubanshe, 2001), 3.

11 Endymion Wilkinson, Chinese History: A New Manual (Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Press, 2013, 3rd edition), 211.

12 Gong, Ningbo gujin fangzhi luyao, 4.

13 Peter K. Bol, “The Rise of Local History: History, Geography, and Culture in Southern Song and Yuan Wuzhou,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 61 (2001): 38.

14 Yoshinobu Shiba, “Ningpo and Its Hinterland,” in The City in Late Imperial China, ed. William G. Skinner (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1977), 392.

15 Xu Chao 許超 et al., “Tangdai Mingzhou chuzhi diwang kaobian” 唐代明州初治地望考, Dongnan wenhua 2016.1: 93.

16 Although Fu Xuancong 傅璇琮, ed., Ningbo tongshi 寧波通史 (Ningbo: Ningbo chubanshe, 2009), 1:188 claims that Gouzhang district moved its administrative seat from Chengshan to Xiaoxi only in 589, local gazetteers show (for example KNFZ juan 1, in QNFZ 1:113 and 131) that this had already happened before 420 CE.

17 In the local gazetteers Yinjiang river often refers to this tributary of the Fenghua River, but it can also refer to the Yong River (JNFZ juan 5, in MNFZ 1:530) or the Fenghua River (QST juan 2, in SYSL 1:64).

18 Fu, Ningbo tongshi, 1:189.

19 KNFZ juan 1, in QNFZ 1:124 and 129.

20 Ningbo shi zhi 寧波市志 (hereafter NBSZ), ed. Yu Fuhai 俞福海 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1995), 1:4ff.; Qianlong Yinxian zhi 乾隆鄞縣志 (hereafter QYZ), Qian Daxin 錢大昕, compiled 1785, 1.25.

21 NBSZ 1:44.

22 JNFZ juan 16, in MNFZ 3:1438ff.; KNFZ juan 1, in QNFZ 1:113 and 131; YNFZ juan 2, in QNFZ 5:3624; NBSZ 1:3.

23 Dushi Fangyu Jiyao Yutu Yaolan 讀史方輿紀要與圖要覽, Gu Zuyu 顧祖禹, 1831 edition, 7 vols., 130 juan plus four supplementary juan of maps, digitized and published online by Bayrische Staatsbibliothek Muenchen. Stable Link: https://ostasien.digitale-sammlungen.de/search?q=%E8%AE%80%E5%8F%B2%E6%96%B9%E8%BC%BF%E7%B4%80%E8%A6%81&searchType=free, [last accessed 26 October 2020], vol. 6, 92.35; Mingzhou Xinian lu 明州繫年錄 digitized and published online by Harvard-Yenching Library Chinese Local Gazetteers Digitization Project. Stable Link: https://listview.lib.harvard.edu/lists/drs-462474752, [last accessed 26 October 2020], 1.13.

24 NBSZ 1.44.

25 According to recent archaeological excavations the exact location of the old city of Gouzhang was at the modern village of Wangjiaba 王家壩村 in the town of Cicheng 慈城鎮 that belongs to the Jiangbei district of Ningbo city 寧波市江北區. See Wang Jiehua 王結華, “Cong Gouzhang dao Mingzhou – Ningbo zaoqi gang cheng fazhan de kaoguxue guancha 從句章到明州—寧波早期港城發展的考古學觀察,” in Lishi shiye xia de gang cheng hudong: shoujie ‘Gang tong tianxia’ guoji gangkou wenhua luntan wenji 歷史視野下的港城互动:首届’港通天下’國際港口文化論壇文集, eds. Ningbo Zhongguo gangkou bowuguan 寧波中國港口博物館 et al. (Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, 2018), 89.

26 Ibid.

27 BSZ preface, in SYSL 2:3.

28 BSZ juan 12 and 13, in SYSL 3:625 and 687. During the Song period, one li had a length of 565.2 m. The definition of the li 里 as a length measure varied throughout Chinese history but after 624 until 1929 it was generally defined as 360 bu 步 with one bu equaling 5 chi 尺, with one chi amounting to 31.4 cm during the Song period, one li had a length of 565.2 m. See Wilkinson, Chinese History: A New Manual, 554ff. (Box 81 and Table 103).

29 Yuanfeng Jiuyu Zhi 元豐九域志, Wang Cun 王存, presented 1080, published 1085 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1984, reprint 2019), 1:214.

30 QST juan 2 in SYSL 1:61; JNFZ juan 19, in MNFZ 3:1439.

31 NBSZ 1:44.

32 Yongzheng Ningbo fu zhi 雍正寧波府志 (hereafter YNFZ), Cao Bingren 曹秉仁 et al., 1731, juan 2, in QNFZ 5:3624; Siming Tuoshan tujing 四明它山图经, Yao Xie 姚燮 (1805–1864), in Yinzhou Shanshui Zhi xuanji 鄞州山水志选辑 (hereafter YSZX), Ningbo Shi Yinzhou Qu difangzhi bianzuan weiyuanhui 寧波市鄞州區地方志編纂委員會 (Ningbo: Ningbo chubanshe, 2009), 1:131.

33 Xu Chao 許超 et al., “Zhejiang Sheng Ningbo Yinjiang gucheng kaogu de zhuyao shouhuo yu chubu renshi” 浙江省寧波鄞江古城考古的主要收穫與初步認識, Nanfang wenwu 南方文物 2015.4: 59.

34 Simingshan Zhi 四明山志, ed. Huang Zongxi 黄宗羲 (1610–1695), juan 1, in YSZX 2:17.

35 QST juan 10, in SYSL 1:359.

36 Xu et al., “Tangdai Mingzhou chuzhi diwang kaobian”, 94.

37 Ibid.; Xu et al., “Zhejiang Sheng Ningbo Yinjiang gucheng kaogu de zhuyao shouhuo yu chubu renshi”, 56ff.

38 Chen Danzheng 陳丹正, “Sui Tang shiqi Ningbo diqu zhou xian chengzhi yange san ti” 隋唐時期寧波地區州縣城址沿革三題, Zhongguo lishi dili luncong 23.2 (2008): 108.

39 Wang, “Cong Gouzhang dao Mingzhou – Ningbo zaoqi gang cheng fazhan de kaoguxue guancha” 89; Xu et al., “Tangdai Mingzhou chuzhi diwang kaobian,” 94.

40 Wang Jiehua 王結華 et al., “Gouzhang gucheng ruogan wenti zhi tantao” 句章古城若干問題 之探討, Dongnan wenhua 2013.2: 98.

41 Xu et al., “Tangdai Mingzhou chuzhi diwang kaobian,” 95.

42 Fu, Ningbo tongshi, 1:188.

43 JTS 40.1590; The Song gazetteer below mentions a distance of 30 li.

44 QST juan 1, in SYSL 1:35.

45 In 589 the territory of the three former districts of Yinxian, Maoxian and Gouzhang were merged into one large district named Gouzhang district. In addition, the district of Yuyao was also integrated into the large Gouzhang district. In 621 Yuyao district was renamed into Yaozhou prefecture 姚州 and the large Gouzhang district (now consisting of the former districts Yinxian, Maoxian and Gouzhang) was named into Yinzhou prefecture (JNFZ juan 1, in MNFZ 1:94, 105, 113 and 115; KNFZ juan 1, in QNFZ 1:124 and 129).

46 See for example: QST juan 2, in SYSL 1:64. This example from the Qiandao Siming Tujing could indicate that in this gazetteer Yingjiang river generally refers to the Fenghua river.

47 See for example: JNFZ juan 5, in MNFZ 1:530.

48 BSZ juan 1, in SYSL 2:33.

49 BSZ juan 12, in SYSL 3:610ff.

50 BSZ juan 12, in SYSL 3:610.

51 QST juan 1, in SYSL 1:35.

52 BSZ juan 1, in SYSL 2:33.

53 BSZ juan 12, in SYSL 3:610f; Yuanhe junxian tuzhi 元和郡縣圖志 (hereafter YJT), ed. Li Jifu 李吉甫 (758–814), completed in 813 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1983), vol. 2, 26.629: 鄮縣上,郭下.

54 I am grateful to an anonymous reader for pointing out to me that the Siku quanshu edition of the Baoqing Siming zhi reads differently from the edition published by Ningbo chubanshe and in Song Yuan fangzhi congkan 宋元方志叢刊 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1990). The text in the Siku quanshu says 州治鄮縣,古鄮縣在阿育王山之西,鄮山之東, which supports my reading that what is located to “the west of Eyuwang mountain” is the old seat of Maoxian district and not the current administrative seat of Maoxian.

55 QST juan 1, in SYSL 1:35; JNFZ juan 1, in MNFZ 1:95.

56 Xin Tangshu 新唐書 (hereafter XTS), eds. Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007–1072) and Song Qi 宋祁 (998–1061), completed in 1060 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1975, reprint 2019), 136.4589ff.; Zizhi Tongjian 資治通鑑, Sima Guang 司馬光 (1019–1086) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1956, reprint 2018), 222.7261.

57 QYZ 1:25.

58 See also Xu et al., “Tangdai Mingzhou chuzhi diwang kaobian,” 93.

59 BSZ juan 1, in SYSL 2:33ff.

60 JTS 40.1590.

61 BSZ juan 12, in SYSL 3:610ff.

62 BSZ juan 11, in SYSL 3:558.

63 NBSZ 1:44; Fu, Ningbo tongshi, 68.

64 Shi Zuqing 施祖青, “Yinxian Baozhuang Xiang Shayan Cun ji zuo Dong Han Jin mu” 鄞縣寶幢鄉沙堰村幾座東漢,晉墓, Dongnan wenhua 1993.2: 85ff.

65 Zhejiang Ningbo Shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Zhejiang Ningbo Shi Yinzhou Qu wenguanban 浙江寧波市文物考古研究所; 浙江寧波市鄞州區文管辦, “Zhejiang Ningbo Shi Yinzhou Qu Caigoutang Jin mu fajue jianbao” 浙江寧波鄞州蔡沟塘晉墓發掘簡報, Nanfang wenwu 2013.3: 32.

66 Zhejiang Ningbo Shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 浙江寧波市文物考古研究所, “Zhejiang Ningbo Meixulongshan Dong Jin jinian muqun de fajue” 浙江寧波梅墟龍山東晉紀年墓群的發掘, Nanfang wenwu 2011.4: 47.

67 Zhejiang Ningbo Shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Zhejiang Ningbo Shi Beilun Qu bowuguan 浙江寧波市文物考古研究所; 浙江寧波市北仑區博物館, “Zhejiang Ningbo Shi Beilun xiaogang Yaoshu Dong Wu Tangdai jinian muzang” 浙江寧波北仑小港姚墅東吴,唐代紀年墓葬, Nanfang wenwu 2012.3: 60 and Zhejiang Ningbo Shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Zhejiang Ningbo Shi Beilun Qu bowuguan 浙江寧波市文物考古研究所; 浙江寧波市北仑區博物館, “Zhejiang Ningbo Beilun Fenghuangshan liang Jin jinian muzang fajue jianbao” 浙江寧波北侖鳳凰山兩晉紀年墓葬发掘簡報, Nanfang wenwu 2013.3: 36.

68 BSZ juan 12, in SYSL 3:610ff.

69 See also: Chenghua Ningbofu Jianyao Zhi成化寧波府簡要志, eds. Huang Runyu 黃潤玉 and Huang Pu 黃溥, juan 1, in MNFZ 8:86.

70 BSZ juan 1, in SYSL 2:33.

71 BSZ juan 11, in SYSL 3:558.

72 BSZ juan 1, in SYSL 2:33.

73 BSZ juan 3, in SYSL 2:141. 1 zhang 丈 (pole) equals 10 chi (foot) With one chi amounting to 31.4 cm during the Song period, one zhang had a length of 3.14 m. Accordingly the city wall of the “inner city” had a circumference of around 1,320 m. See Wilkinson, Chinese History: A New Manual, 555ff. (Tables 102 and 103).

74 JNFZ juan 2, in MNFZ 1:162.

75 Xuanfeng Yinxian Zhi 咸豐鄞縣志 (Ningbo: Ningbo chubanshe, 2018), juan 10: 230; BSZ juan 12, in SYSL 3:613.

76 QST juan 1, in SYSL 1:42; BSZ juan 11, in SYSL 3:558ff.

77 YJT 26.629: 鄮縣,上,郭下.

78 YJT 26.629: 句章古城,在州西一里。州 here refers to Mingzhou.

79 Ibid.: 武德八年再置,仍移理句章成,後屬明州. In 625 the district of Maoxian was re-established and the administrative seat set up at the [former seat of Yinzhou] at the city of Gouzhang which later was administered by Mingzhou.

80 JTS 148.3992f; XTS 146.4738. For the translation of the title 長史 see Hucker, A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China,112 (entry 185).

81 YJT 26.629ff.

82 BSZ juan 12, in SYSL 3:610.

83 YJT 26.629: 武德八年再置,仍移理句章成,後屬明州. In 625 the district of Maoxian was re-established and the administrative seat set up at the [former seat of Yinzhou] at the city of Gouzhang which later was administered by Mingzhou.

84 Taiping huanyu ji, 98.1961.

85 Ningbo Shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo寧波市文物考古研究所, “Zhejiang Ningbo Tang Guoning Si dong ta yizhi fajue baogao” 浙江寧波唐國寧寺東塔遺址發掘報告, Kaogu xuebao 1995.1: 81–120.

86 Wang Jiehua et al., “Gouzhang gucheng ruogan wenti zhi tantao,” 99.

87 QST juan 1, in SYSL 1:39; YNFZ juan 2, in QNFZ 5:3618.

88 Fu, Ningbo tongshi.