?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Although the typical end goal of an online grooming event is to lure a minor into performing sexual activity (either online or offline), no previous study has examined the relevance of targets’ sexual knowledge on the progression of these events. To address this gap, we deployed two honeypot chatbots which simulated young female users in a sample of twenty-three online chatrooms, over a period of three months. The first chatbot simulated a sexually knowledgeable target while the second chatbot simulated a sexually naïve target. Findings from 319 online grooming events indicate that an online grooming event is more likely to progress in the presence of a sexually knowledgeable target. Moreover, we find that online grooming events with sexually knowledgeable targets lasted longer than online grooming events with sexually naïve targets. Finally, we found that sexually knowledgeable targets were more likely to be solicited for offline encounters than sexually naïve targets.

Introduction

Despite recently increased attention to the online grooming phenomenon, there are still many under-investigated aspects of the associated crime events. One unexplored aspect of the online grooming process is the role of the target’s sexual knowledge in determining the progression of an event and the direction of the conversation between the offender and the target. Indeed, while most previous research on online grooming focuses on the phase in which online groomers introduce sexual content into communications with their targets, findings from this research are mixed (O’Connell, 2003; Webster et al., Citation2012; Kloess et al., Citation2019). Specifically, while early research suggested that sexual language and content appears at a later stage of the online grooming process (O’Connell, 2003), more recent work indicates that online groomers introduce sexual content fairly early in communications with their targets (Webster et al., Citation2012; Winters et al., Citation2017). Still, despite some observations that sexual experience (Quayle et al., Citation2012) and sexual behavior (Gámez-Guadix & Mateos-Pérez, Citation2019; De Santisteban & Gámez-Guadix, Citation2018) are positively associated with the online grooming process, no previous study has explored how targets’ sexual knowledge shapes their suitability as targets (from the offender’s perspective) for an online sexual grooming event. Moreover, since the literature on target suitability and target selection practices during online grooming is primarily based on cross-sectional studies, police reports, or vigilante groups’ transcripts (Webster et al., Citation2012; Taylor, Citation2017; Kloess et al., Citation2019), insights from this line of research are limited in scope.

To address this gap in the literature, we draw on Cohen and Felson (Citation1979) conceptualization of target suitability to test the relevance of the target’s sexual knowledge in shaping the progression of an online grooming event. To assess the role of targets’ sexual knowledge in the target selection practice, we conducted a simulated field experiment using “honeypot” chatbots (i.e. an online trap which fools cybercriminals into thinking it’s a legitimate target). The honeypot chatbots were deployed in a sample of twenty-three online chatrooms and simulated two types of young female targets: a sexually knowledgeable target and a sexually naïve target. As far as we are aware, the experimental approach we adopt in this research represents one of the first attempts to study the issue of target suitability among young targets of online grooming in a real setting.

Background

The Online Sexual Grooming Process

Online sexual grooming is a complex and multifaceted process (Mitchell et al., Citation2011; Wager et al., Citation2018) in which groomers initiate online communication and attempt to form relationships with minors via Information and Communications Technology (ICT) (Joleby et al., Citation2021). The communication between the offender and the target often take place in chatrooms, social media sites, forums, and instant messaging applications (Cano, et al., Citation2014; Lykousas and Patsakis, Citation2021). Due to the prevalence of online sexual grooming, this type of crime has received ample scientific attention from scholars around the world. Specifically, several studies show that online groomers tend to be men (DeHart et al., Citation2017; Shannon, 2008; Villacampa & Gomez, Citation2017; Winters et al., Citation2017) between the ages of 25 to 40 (Shannon, 2008; DeHart et al., Citation2017; Winters et al., Citation2017; Villacampa and Gómez, Citation2017), while online victims tend to be girls (De Santisteban & Gámez-Guadix, Citation2018; Marret and Choo, Citation2017; Sklenarova et al., Citation2018; Hernández et al., Citation2021; Dönmez and Soylu, Citation2019) between the ages of 13 and 15 (Mitchell et al., Citation2001, Citation2014; Montiel et al., Citation2016; Webster et al., Citation2014).

In addition to identifying the demographic characteristics of victims and offenders, several studies have modeled the stages through which online grooming events progress. One of the most cited models of the online grooming process is that by O’Connell (2003). According to O’Connell, the first phase in the development of an online grooming event is Friendship Forming. In this phase, the online groomer gets to know the potential victim and checks whether the victim’s appearance matches his predilections at this stage. During the second phase, Relationship Forming, the online groomer inquiries about the victim’s personal life (e.g. school, home) and attempts to gain the victim’s trust by pretending to be his or her best friend. The third stage is Risk Assessment. In this phase, the online groomer asks about the whereabouts of the target’s computer and explores whether someone around the target could prevent/detect the activities the online groomer wants the child to perform.

During the fourth stage, Exclusivity, the groomer assesses the minor’s trust level in order to prepare him or her to introduce more intimate content. This is followed by the Sexual Stage, in which the groomer introduces sexual content through questions directly related to the child’s sexual experiences. According to O’Connell, an online groomer may engage the minor in this stage in fantasy enactment, a video chat, or solicit pictures and videos from the minor. Following the sexual stage, online groomers launch the Damage Limitation phase, in which online groomer reinforces trust and secrecy to reduce the risk that the minor would disclose their conversation and the online activities to somebody. The final stage is the Hit and Run Tactic. Here, the online groomer downgrades his damage control and increases contact with the victim. If the victim does not comply or submit to the groomer, he either becomes purely aggressive and coercive or ends the communication.

Williams et al. (Citation2013) proposed an alternative sequence to the online grooming process. According to this model, Rapport Building, Sexual Content, and Assessment are three key phases which describe the progression of an online sexual grooming event. Rapport building involves specific modifications to the perpetrator’s behavior when forming a relationship with the child (for a review, see Williams et al., Citation2013). During the sexual content phase, the introduction of sexual content often occurs through discussions of everyday topics, asking about sexual experiences, and games. The maintenance and escalation of sexual content both occur by repeatedly introducing sexual topics. The last phase of the process is assessment, where the online groomer assesses the child’s vulnerability, trust, and responsiveness to interaction, as well as the environment within which their interactions take place.

These early models of the grooming process suggest a linear progression between the stages (O’Connell, 2003). However, more recent work indicates that the movement and time spent at each stage depends on the online groomer’s motivation (Williams et al., 2013; Kloess et al., Citation2019). For example, Kloess et al. (Citation2019) found that while some offenders spent more time building rapport with their victims, other employed very direct, blunt, and sexual content very early during their conversations with targets. Although all of these models denote distinct stages for the progression of online sexual grooming, they fail to consider how offenders select their targets and how certain attributes may affect target selection. To address this gap in the literature, we draw on the VIVA target suitability model (Cohen & Felson, Citation1979) and consider the relevance of value in the progression of the online grooming event.

Routine Activity Theory and Target Selection

In their now-classic paper, Cohen and Felson (Citation1979) suggested that successful criminal events take place when motivated offenders meet suitable targets in certain places and at certain times, when capable guardians are absent. Routine daily activities drive both offenders and victims to those locations at certain times. Key to our study is Cohen and Felson (Citation1979) conceptualization of target suitability, which suggests that a target’s attributes determine how attractive a target is from the offender’s perspective. According to this perspective, four elements determine the attractiveness of a criminal target: Value, Inertia, Visibility, and Accessibility (VIVA). Value refers to the real or symbolic worth, utility, or importance the offender assigns to a target’s characteristics, such as age, gender, or race (Holt et al., Citation2016). Inertia refers to the physical aspects of a target (i.e. size, weight, or shape) that may form an obstacle for the offender’s purposes. Visibility identifies the exposure of a target to an offender, for instance, the amount of time a user spends online (De Santisteban & Gámez-Guadix, Citation2018). Finally, accessibility is the facility by which the offender can reach the target without risking getting caught, for example, using chatrooms and social media (Mitchell et al., Citation2013). Extending the VIVA model, Clarke (1999) further specified the characteristics a “hot product”. Accordingly, his CRAVED model proposes five characteristics that produce a desirable target: concealable, removeable, available, valuable, enjoyable, and disposable. These characteristics were reported to be relevant in the context of online targets of phishing (Ghazi-Tehrani & Pontell, Citation2021), Fraud (Pratt et al., Citation2010), and cyber-harassment (Llinares, Citation2013). Previous studies that assess the applicability of these models to various types of cybercrime have reported that although value, visibility, and accessibility translate well to online environments, the property of inertia tends to be less relevant (Yar, 2005; Miro, 2012, 2015; Leukfeldt and Yar, Citation2016).Footnote1

Finkelhor and Asdigian (Citation1996) argued that although the VIVA model provides valuable insights into victimization, it falls short in capturing the complete range of risk factors contributing to victimization. According to Finkelhor and Asdigian (Citation1996), the process of selecting suitable targets is determined by specific personal or individual characteristics that align certain youth more closely with the needs, motives, or reactivities of offenders (p.6). They identified three types of characteristics: target vulnerability, target gratifiability, and target antagonism. Target vulnerability refers to characteristics that impede a target’s ability to resist or deter victimization (e.g. physical characteristics, psychological problems, etc.). Target gratifiability refers to qualities or skills desired by the offender, which they seek to obtain or manipulate (e.g. choosing a female target for a sexual assault). Lastly, target antagonism refers to characteristics or qualities of a target that provoke anger or jealousy impulses in the offender. Analyzing data from the national youth survey, Finkelhor and Asdigian (Citation1996) found that at least one of the three target congruence variables predicted the following types of victimization: nonfamily assault, sexual assault, and parental assault.

Several studies have drawn upon Finkelhor and Asdigian’s target congruence approach to explain youth victimization (e.g. (Choi et al., Citation2022); Räsänen et al., Citation2016; Helton et al., Citation2018; Sutton et al., Citation2021). For instance, Helton and colleagues (2018) utilized target congruence to examine whether children with learning disabilities are more susceptible to experiencing sexual abuse. Their study demonstrated that children with learning disabilities were twice as likely to experience sexual abuse compared to children without such disabilities. Despite increasing support for the model, limited studies have operationalized target suitability in terms of individual characteristics within the context of online sexual grooming. For example, Holt et al. (Citation2016) operationalized target suitability using demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and race.

Other studies have considered the effect of online behaviors in determining a target’s perceived suitability for grooming victimization. For example, Wachs et al. (Citation2020) operationalized target suitability based on disclosure of private information online. They found that disclosing personal information online is positively correlated with online sexual grooming victimization. Marcum et al. (Citation2010) measured target suitability using items related to privacy settings, type of information posted online (e.g. gender, age, description, pictures, phone number, family conflicts, etc.), communicating with a stranger online, and disclosing personal information to a person met online. They found that both sharing information online and communicating with strangers significantly and positively increased victimization from online sexual grooming. The effect was found to be more prominent among female targets.

Importantly, two key studies have also explored whether the interaction between groomers and targets is impacted by the sexual attributes of the victim. Peske (Citation2014), for example, differentiated between sexually knowledgeable and sexually naïve victims of online grooming, and explored how those aspects influence victims’ experiences, perspectives, and responses to their victimization. She found that there are two subgroups of victims: those who lacked knowledge and experience (naïve) and those who were sexually knowledgeable and experienced (Peske, Citation2014). Naïve victims were more likely to experience the grooming process as a learning process or feign responses until they learned the meaning of the new sexual content. By contrast, sexually knowledgeable and experienced victims fueled the grooming process, as they tended to convey excitement regarding sexual content, along with greater willingness to engage in sexual conversation and physical encounters (Peske, Citation2014).

Similarly, drawing on interviews with 12 online groomers from Italy and the UK, Quayle et al. (Citation2014) explored the strategies employed by online groomers to identify their targets. These scholars found that factors influencing target selection are profile availability, the target’s physical appearance, and the belief that the young target was sexually curious. Quayle and her colleagues argued that once the online groomer satisfied his belief that a child was sexually curious, he immediately introduced sexual content and abuse into the communication with the child (Quayle et al., Citation2014). In summary, the effect of sexuality on different stages and aspects of the online sexual grooming event has been previously established in the literature (Peske, Citation2014; Quayle et al., Citation2014). Previous works have not investigated how a target’s sexual knowledge affects online groomers’ target selection process or whether it impacts the progression of the online grooming event.

The Current Research

We draw upon both Cohen and Felson (Citation1979) target suitability VIVA model and Finkelhor and Asdigian (Citation1996) target congruent approach. We propose that offenders may assign increased value to a target because they possess characteristics that align with the offenders’ needs and motives. Specifically, we argue that the symbolic importance or worth assigned by offenders to a victim may vary based on various factors, including personal characteristics such as age, physical appearance, and sexual orientation, as well as behaviors and developmental cues (Finkelhor & Asdigian, Citation1996). This notion has been previously suggested in the criminological literature (Wooldredge & Steiner, Citation2014; Livingston et al., Citation2007; Kahle & Peguero, Citation2017).

Building upon this research, we hypothesize that online groomers may assign different value to sexually knowledgeable targets compared to sexually naïve targets (Felson & Cohen, 1979). Specifically, we argue that online groomers may perceive sexually knowledgeable targets as more suitable for online grooming events because their knowledge aligns with the groomers’ motives and needs (Finkelhor & Asdigian, Citation1996). This may be because knowledgeable targets may be more familiar with sexual jargon and experiences, making communication on this topic easier compared to sexually naïve children (Peske, Citation2014). As such we examine whether the interaction between online groomer and sexually knowledgeable target takes different shapes and forms compared to the interaction between an online groomer and a sexually naïve target. We specifically advance four hypotheses.

Our first goal in this study is to examine whether a target’s sexual knowledge affects online groomers’ continuous engagement in communication with the target. As such, we examine whether interaction with a sexually knowledgeable target results in an increased likelihood of online grooming communication proceeding than when the target is sexually naïve. Drawing on previous descriptive findings that show that online groomers choose targets based on their sexual curiosity (Quayle et al., Citation2014), we hypothesize that online groomers are more likely to continue to engage in communication when the target is sexually knowledgeable than when the target is sexually naïve.

Second, we explore whether online groomers are more likely to move to the sexual phase, based on the target’s level of sexual knowledge. Indeed, several studies have found that online sex offenders’ decisions regarding criminal engagement depends on their cognitive distortions related to sexuality. Drawing on previous studies which indicate that an offender’s decision to introduce explicit sexual content into an online communication occurs once the offender believes that the target is sexually curious (Quayle et al., Citation2014), we suspect that a sexually knowledgeable target will fit with online sexual groomers’ distorted beliefs that children are sexual beings, and in turn, will satisfy those offenders’ beliefs. This quality may make sexually knowledgeable targets more open to explicit sexual content than sexually naïve targets in the groomer’s eyes, and may increase the probability of introducing sexual content during conversations with sexually knowledgeable targets. Therefore, we hypothesize that an online sexual grooming event is more likely to proceed to explicit sexual content when the target is sexually knowledgeable than when the target is sexually naïve.

Third, we examine whether a target’s sexual knowledge impacts the probability that an online grooming event will escalate to an offline meeting request. Previous analyses using police reports and preventive justice scripts suggest that a groomer’s decision to solicit offline contact is driven by the offender’s motivation (Briggs et al., Citation2011). However, drawing on the assumption that target suitability affects the progression of a criminal event, we argue that online groomers may assign different values to different targets based on their suitability for different outcomes. As such, it may be that sexually knowledgeable females may be perceived as more suitable for offline contact by online groomers, as their behavior aligns with groomers’ views of minors as sexual beings (see Paquette & Cortoni, Citation2022). We hypothesize that an online grooming event is more likely to proceed to a request for an offline meeting when the target is sexually knowledgeable than when the target is sexually naïve.

Finally, we are interested in whether the average duration of an online grooming event varies depending on the target’s level of sexual knowledge. Indeed, previous research has shown that online grooming conversations tend to be long and sometime span weeks (Webster et al., Citation2012). However, there is still a lack of clarity regarding the profile of victims who engage in such long conversations with their perpetrators. Consistent with Quayle et al. (Citation2014), we suspect that online groomers may perceive sexually knowledgeable targets as sexually curious individuals who may be more open to new sexual experiences. As such, online groomers may assign high value to such targets and may be willing to invest more time in grooming them, with the hope of some future personal benefits (e.g. online relationships, sexual gratification, and offline meetings). In contrast, since sexually naïve targets do not possess the aptitude required to engage in sexually stimulating online conversations, online groomers may assign a low value to such targets, and may be less interested in spending their time with such individuals. Therefore, our last research hypothesis suggests that the duration of online grooming events between sexually knowledgeable targets and groomers may be longer than the duration of online grooming events between sexually naïve targets and groomers.

Data and Methods

Most previous studies examining online sexual grooming have relied on police data, sting operation scripts, and data provided by cyber-watch organizations such as Perverted-Justice (Aitken et al., Citation2018; Black et al., Citation2015; Taylor, Citation2017). While these works provide important and significant insights into the issue, their data only allows retrospective analysis which lacks a temporal sequence and has limited generalizability. Addressing this issue in our research, we join other cyber criminologists in using research honeypots to collect data on cybercrime directly from the field and create effective experimental research designs (Howell et al., Citation2017; Maimon et al., Citation2014, Citation2019; Fisher et al., Citation2022; Kigerl, Citation2014; Kamar et al., Citation2022).

Honeypots are traditionally used in the cybersecurity field as a decoy tool (for example, a computer, a network, or an online account) to which cyber attackers are lured in effort to detect, deflect and study malicious actors’ online illegal behavior (Spitzner, Citation2002). Since this tool allows the tracking of offender behavior during the progression of a criminal event, it has been adopted by social scientists to study factors contributing to the progression of different online offending behaviors, including hacking (Howell et al., Citation2022; Kamar et al., 2023; Maimon et al., Citation2014; Wilson et al., Citation2015; Testa et al., Citation2017), online fraud (Maimon et al., Citation2019; Maimon et al., Citation2020), and online sexual grooming events (Kamar et al., Citation2022). Building on these past studies, our project employs a honeypot chatbot (henceforth, a bot) to conduct a field experiment that examines the effect of target sexual knowledge on the progression of an online sexual grooming event. We believe that adopting this data collection approach in the study of online grooming allows better observation of the progression of an online sexual grooming event, particularly following the introduction of sexually knowledgeable or naïve stimuli to the online grooming situation.

Design

To investigate the effect of a target’s sexual knowledge on groomers’ decisions to further pursue the grooming process, we created two bots which simulated two 13-year-old female users in the chatrooms. We opted to simulate female targets as prior research shows that female users are at greater risk of online sexual grooming (Hernández et al., Citation2021; Finkelhor et al., Citation2002). A chatbot uses computer software intended to simulate a conversation with other users over different online communication platforms (Dahiya, Citation2017). It uses natural language processing and machine learning to understand and respond to users in a human-like manner (Khanna et al., Citation2015).

Procedure

We deployed two user profiles (treatment and control) using two honeypot chatbots in a sample of 23 randomly selected teen chatrooms for a three-month period (February 10 to May 10, 2022, a total of 180 h of data collection). The chatrooms sampled for this study were found with a simple Google search for “teen chatrooms.” Despite the huge number of results found (4.8 M), it is difficult to provide an exact number of distinct chatrooms. We randomly selected one chatroom from each of the first 23 pages of search results. The chatbots were passive, in the sense that they only responded to incoming messages and did not initiate communication with other users. Moreover, the chatbots were designed to only engage in conversations with users who identified themselves as at least 18 years old. To simulate a genuine user profile, we uploaded a profile picture of a young female to each of the bots’ profiles, using images from the website “This Person Does Not Exist” (see https://thispersondoesnotexist.com/).

The two bots we designed for this experiment were programmed to follow a prescribed flow of conversation with online groomers, based on identification of questions and answers. Specifically, the bots were programmed to respond first to incoming chat messages which identified the contacting user’s age. Once the bot established that the contacting user was an adult (18 and above), it proceeded with the conversation based on a prescribed script. To design the script, we drew on the Perverted-Justice scripts published on their website (http://www.perverted-justice.com/)Footnote2. More specifically, if the bot recognized one of the keywords we categorized as indicating a certain intent, the bot sent an automatic message corresponding to this intent to the groomer. In situations where the sentence information couldn’t be categorized with certainty, often due to predators’ misspelling words or swapping letters with numbers, an email alert was sent to the first author with the full content of the conversation, including an indication of which treatment chatbot the conversation belonged to. The first author then answered the email in accordance with the treatment conversation flow assigned to the bot. The content of the reply would then be sent in the chat to the groomer, to maintain the conversation flow. A demo describing the bot’s operation is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = hn001H3i9Ro.

The servers that operated the bots were uploaded twice a day, from 8 pm-11 pm UK time and 8 pm-11 pm West Australia Time. On average, 30 s after the connection of the chatbot to the online chat, we started to receive messages, either from legitimate users (i.e. genuine users of the chatrooms such as minors) or potential groomers (i.e. users that identified as above the age of 18). In accordance with our IRB approval protocol (#001) that allowed us to engage only with users that identified themselves as adults above the age of 18, the first message the chatbot was designed to send was "Hi, ASL?" (Age, Sex, Location). Although we were not interested in the location of the person, this type of information is commonly shared between people in online chatrooms. Conversations with users that identified themselves as below the age of 18 were immediately dropped.

Following the filtering out of irrelevant users, conversations were carried out depending on the treatment assigned to the bot. Both bots had prescribed conversation scripts, but one bot was designed to convey a sexually naïve target (control) and the other was designed to convey a sexually knowledgeable target (treatment). The topics covered for the control and treatment groups were identical (hobbies, schools, friends, and family life); the only difference was in their response to sexual content. For example, if an online groomer inquired about the number of brothers and sisters the target has, the chatbot answered “I don’t have siblings.”

Once online groomers introduced sexual content into the communication, such as "are you a virgin?" or "have you ever been with a boy?", the bot triggered answers corresponding to the treatment or control scripts that were assigned to the bot. Online groomers who communicated with the sexually naïve bot received the following answer to messages that contained sexual content: "I don’t know what that means…what does it mean?". Online groomers who communicated with the sexually knowledgeable bot received the following answer to messages that contain sexual content "I know what it means…I haven’t." It is important to note that both chatbots were depicted as sexually inexperienced. The only difference was that while one target portrayed itself as knowing what the sexual act meant, the other communicated that it did not.

After each data collection session, the bot automatically backed up the relevant conversation logs in a secure environment. This environment supported easy access to the data and anonymized and deleted any identifiers. Importantly, to comply with the IRB approval we obtained for this project,Footnote3 and to ensure that both genuine users of the platforms and suspected groomers were not harmed, the bot was designed to respond to received chat messages only.

Dependent Variables

All four outcome measurements in this research reflect aspects of the progression of online sexual grooming events. The first outcome tracks the continuity of the online sexual grooming communication. Continued engagement in grooming communication indicates whether the online grooming event continued after the bot answered two sexual questions. Thus, if the groomer continued to engage in the grooming process following two treatment triggers, we coded it as 1. If the communication ceased, we coded this measure as 0. We choose two responses, rather than one, to capture intent. Children often lack knowledge regarding sexuality, so responding to one probe could be viewed as ignorance. Responding to two sexual questions, however, demonstrates a willingness to engage in conversation pertaining to sexual matters.

To measure our second hypothesis, we measure whether the grooming event proceeded to explicit sexual content following the introduction of our treatment. Explicit sexual content refers to groomers soliciting pictures or video calls, sending pictures of themselves or pornographic content, or engaging in detailed sexual conversations also referred to as cybersex (see Appendix A). If the communication between the online groomer and the bot proceeded to explicit sexual content, we coded this measure as 1; if the communication did not proceed to explicit sexual content, we coded this measure as 0.

To test whether potential targets’ sexual knowledge influenced the likelihood of groomers suggesting an offline encounter, we created the variable request for offline encounter. We coded it as 1 if the offender suggested/arranged an offline encounter and 0 if the offender engaged in cybersex, solicited a picture or video chat, or sent a pornographic picture (see Appendix B). Finally, to test our final research question, we create the measure duration of online grooming event, which measures the duration (in minutes) of the online grooming event from the groomer’s first message to the end of the conversation.

Independent Variables

We created a variable that signifies whether the grooming event took place with a knowledgeable or naïve (control group) target (knowledgeable = 1, naïve = 0). To control for clustering related to the chatroom in which the event took place, we created dummy variables that indicate the chatroom. Since we anonymized the chatrooms, each chat room received a number between 1 and 23. If the event belonged to the chatroom, it was coded 1, and 0 otherwise.

Analytical Strategy

Our analytic strategy proceeds as follows. First, we present descriptive statistics for the variables of interest. Following this, we estimate the relationships between our list of dependent and independent variables, using a series of logistic models. Lastly, we determine the effect of our treatment on the duration of online sexual grooming, using a life table analysis followed by Cox proportional hazard regression. Since our data is nested within different chatrooms, we employed logistic regression models with Huber’s standard error adjustment for clustering (Huber, 1967). Huber’s adjustment allowed us to control for clustering and for within-cluster unobserved correlations. The decision not to run a multilevel model was based on several simulated studies showing that conducting a multilevel regression model when the number of clusters is small results in computational problems (McNeish and Stapleton, Citation2016; Ali et al., Citation2019).

Results

Overall, our bots recorded 319 online sexual grooming events over the three months of data collection: 179 communications were recorded between online groomers and the naïve chatbot, and 140 communications were recorded between online groomers and the knowledgeable chatbot. presents descriptive statistics for our sample. As can be seen there, most of the groomers that approached our bots were males between the ages of 18 and 76. On average, 16 min passed from the commencement of the interaction between the online groomers and the chatbots and the time the groomer introduced sexual content to the online communication. The average duration of a conversation was 38 min. Estimating the descriptive statistics separately for the control and treatment groups suggests that the only significant difference between the groups was the proportion of online groomers who wanted to know whether the target was alone prior to sending messages with sexual content.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

To test our first research hypothesis, we ran logistic regression models with Huber’s standard error adjustment for clustering (Huber, 1967) and estimated the effect of our treatment variable on the Continued engagement in grooming communication. As can be seen in , a target being sexually knowledgeable is significantly and positively related to the Continuity of engagement in grooming communication. (OR = 2.03, SE = .345, p < .05). Specifically, being sexually knowledgeable doubled the odds that online groomer continue to engage in grooming communication.

Table 2. Online groomers continued engagement in grooming communication. regressed over target’s sexual knowledge.

To examine our second hypothesis, we estimated another logistic regression model with Huber’s error adjustment and tested the effect of our independent variable on the progression of the online grooming event to include explicit sexual content. As indicated in , being sexually knowledgeable is significantly and positively related to the progression of the online grooming event to explicit sexual content (OR = 1.77, SE = .096, p < .0001). The analysis indicates that a target being sexually knowledgeable increased the odds of online grooming to progress to explicit sexual content by 77%.

Table 3. Explicit sexual content introduced during the online grooming event regressed over target’s sexual knowledge.

To test our third hypothesis, we estimated a third logistic regression model with Huber’s error adjustment and tested the effect of our independent variable on requests for offline meetings. Results from this analysis are presented in , which shows that sexually knowledgeable targets are more likely to be offered an offline physical meeting. Specifically, sexually knowledgeable targets are twice as likely to be asked to meet offline than sexually naïve targets (OR = 2.204, SE = .382, p < .05).

Table 4. Offline meeting request regressed over target’s sexual knowledge.

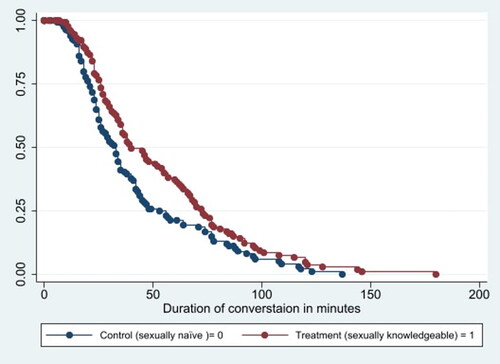

To explore the effect of sexual knowledge on the duration of an online grooming incident, we first ran a standard life table analysis (Namboodiri & Suchindran, Citation1987). To determine whether sexual knowledge influenced the duration of online grooming incidents, we compare the survival distribution of online grooming incidents with sexually knowledgeable targets with the corresponding survival distribution of online grooming incidents with naïve targets. The results from this analysis are presented in . As can be observed in the figure, the proportion of online grooming communication incidents that survived longer periods of time is longer for the treatment (sexually knowledgeable) target than for the control (naïve) target. Sexually knowledgeable targets’ duration was on average 45.80 min (SD = 33.93, Min = 2, Max = 180), compared to an average duration of 32.48 min for sexually naïve targets (SD = 26.36, Min = 3, Max = 137). This finding is consistent with our last research hypothesis.

To test whether this difference between the groups is significant, we estimated a Cox proportional-hazard regression with the target’s sexual knowledge as the independent variable and the hazard of the online grooming event as a dependent variable. The results from the model are presented in . As can be observed there, the hazard rate for an online grooming communication to end is lower for sexually knowledgeable targets than for sexually naïve targets (b = −0.339, SE = .121, p < .01). Specifically, the hazard ratio estimate for sexually knowledgeable targets suggests that an online grooming event with a sexually knowledgeable target reduces the rate of event termination by 29% in comparison to communication with a sexually naïve target. This finding offers further confirmation of our final research hypothesis.

Table 5. Duration of online grooming event regressed over target’s sexual knowledge.

Discussion and Conclusions

Previous research has found that suitable targets for an online sexual grooming event include those who disclose private information online, have poor academic performance, engage in risky online behavior, and fail to apply privacy settings on social media (Bossler et al., Citation2012; Marcum, Citation2008; Marcum et al., Citation2010; Wachs et al., Citation2020). Still, despite the important role that sexuality plays in the narrative of online sexual grooming (Chang et al., Citation2016; Kloess et al., Citation2019; Mitchell et al., Citation2007b; Taylor, Citation2017; Webster et al., Citation2012; Winters et al., Citation2017), we are not aware of any previous study which examined the effect of targets’ sexual knowledge on the progression of online sexual grooming events in an experimental context. Addressing this gap, we drew on Cohen and Felson’s (Citation1979) concept of target suitability and Finkelhor and Asdigian (Citation1996) target congruence approach and asked whether an online grooming event takes different forms when the targets are either sexually knowledgeable or sexually naïve. To answer our research questions, we designed two chatbots which simulated a sexually knowledgeable and a sexually naïve target (respectively), deployed them in 23 teen-focused chatrooms for a period of three months, and collected 319 conversations with online groomers following a field experiment protocol. Analyses of our data revealed three key findings.

First, we found that online groomers were more prone to continue engaging in communication with sexually knowledgeable targets than with naïve targets. This finding suggests that the offenders perceived sexually knowledgeable minors as more suitable for online grooming. In line with Finkelhor and Asdigian (Citation1996), this finding shows that individual characteristics (i.e. sexual knowledge) impact the level of suitability an online groomer assigns to a target. A possible explanation for the increased likelihood of engaging in communication with minors may be that online groomers perceive the behavior of sexually knowledgeable targets as aligned with their motives and needs for sexual gratification (Finkelhor & Asdigian, Citation1996).

Second, we find that sexually knowledgeable targets were more likely than naïve targets to receive sexually explicit content during the communication. This finding is consistent with Quayle et al. (Citation2014) findings indicating that offenders introduce sexually explicit materials once they believe that the child is sexually curious. This may be explained by offense supportive cognition theory, which maintains that the sexual offending behavior is developed and maintained by cognitive processes and beliefs that justify one’s behavior (Abel et al., Citation1984). A recent study identified four main cognitions (Paquette & Cortoni, Citation2022). The main cognition relevant to this finding is the belief that children are sexual beings, i.e. that they are capable of enjoying and seeking sexual activities. In the context of this study, it might be that the online groomers interpreted sexually knowledgeable targets’ behaviors as sexually provocative.

These findings suggest that while youth may engage in the same activities, their level of vulnerability to online sexual groomers may vary depending on other characteristics (Finkelhor & Asdigian, Citation1996). This extends the current body of knowledge by showing that online sexual groomers take into consideration a target’s sexual knowledge in their selection of a suitable target. Previous studies (Jonsson et al., Citation2019; Wachs et al., Citation2020; Mitchell et al., Citation2008) show that a target’s explicit sexual behavior (for example, seeking to talk about sex online, or sharing pictures online) increases their likelihood of falling victim of online sexual grooming.

Our study also expands on previous studies by demonstrating that online sexual groomers value sexually knowledgeable targets as more suitable for the progression of online grooming. This finding is consistent with those by Finkelhor and Asdigian (Citation1996), who found that offenders chose targets that possess characteristics that the offender wants to use or manipulate. That is to say, that online groomers perceive sexually knowledgeable targets as more suitable than sexually naïve targets. A possible explanation is that sexually knowledgeable targets satisfy online groomers’ belief that children are sexually curious (Quayle et al., Citation2014), motivating them to pursue communication with them.

Third, we find that sexually knowledgeable targets were more likely to receive requests to meet offline than sexually naïve targets. This challenges Briggs et al. (Citation2011) idea that offenders’ motivations dictate whether the grooming event ends with offline contact. Instead, our findings suggest that the factors that affect the suitability of the target also impact the outcome decision. A possible explanation for these findings is that online groomers make a cost-benefit decision. Sexually naïve children may require more education and preparation before an encounter, compared with sexually knowledgeable children. Moreover, this is in line with previous studies showing that online groomers who seek offline encounters spend less average time building rapport, instead introducing their desires early in the conversation (Winters et al., Citation2017).

Finally, we found significant differences in the duration of the online grooming events initiated with sexually knowledgeable vs. sexually naïve targets. Specifically, the conversations with sexually knowledgeable targets were longer than conversations with sexually naïve targets. This finding moves us from a focus on offender motivation as a factor for target selection to consideration of situational factors in the target selection, such as the target’s worth, importance, and utility to the online groomer. A possible explanation for this finding may be that offenders who discuss sexual topics with sexually knowledgeable targets view the children as sexual beings (Paquette and Cortoni, Citation2021) and simply want to prolong the excitement related to the grooming process. Further research is needed to better understand the role of cognitive distortions in the suitable target selection process.

The current study’s methodology improves previous studies’ methods in two notable ways. First, our measures capture real behavior rather than perceived behavior. By using the honeypot method, introducing distinct situations to the online grooming communication, and measuring the progress and outcome of the grooming process, our data is not biased by participants’ inability to report victimization, or by the lack of information available in transcripts. Second, employing an experimental approach to test the effect of target sexual knowledge on the grooming selection process allows us to develop stronger causal statements. The utilization of an experimental research design and the use of honeypot technology to assess the grooming process answers calls to assess cybercrime using innovative and rigorous scientific methods (Howell & Burruss, Citation2020).

Theoretically, this study provides additional support for the importance of focusing theoretical attention on the progression of online criminal events (Howell et al., Citation2022; Kamar et al., 2023; Maimon et al., Citation2020; Maimon et al., Citation2014). While some of the contemporary criminological literature examines offenders’ motivation and decision-making processes, decision-making during the progression of a criminal event is still understudied. Our study is one of the few that examines online groomer enticement to engage in crime in real time. Moreover, while previous studies have conceptualized target suitability using demographic characteristics like age or gender (Holt et al., Citation2016); disclosure of personal information (Waches et al., 2020); and privacy settings, communication with strangers, or posting information online (Marcum et al., Citation2010), our study advances the conversation in several ways. First, our study is the first to assess real-time target suitability considerations of online sexual groomers and how sexual knowledge affects the selection process of a suitable target and, in turn, the progression of an online grooming event. Second, the present study is the first to draw on a target attractiveness model. We adopted Cohen and Felson’s (Citation1979) VIVA model for target suitability. Specifically, we employed the value element of the model to test the effect of sexual knowledge on the progression of online sexual grooming events. As such, our study utilizes routine activity theory in the context of online sexual grooming, demonstrating that value can be applied to the understanding of target selection in an online grooming event. Finally, our study expands on previous studies by examining real offender behavior in the field.

Policymakers can use this information in several ways. First, the findings of our study suggest the importance of awareness campaigns designed to evoke self-protection behaviors among adolescent girls with increased sexual knowledge, as they are more susceptible to online grooming and more likely to be asked to meet offline. Moreover, our findings suggest that children should be educated about the importance of online privacy. For example, they should be cautioned that certain types of information should not be shared with strangers online. Evoking self-protection activities and online privacy behaviors can be achieved through awareness and education campaigns on cyber-privacy and cyber-safety.

Since individuals are the weakest link in the production of cybercrime, developing software programs that identify and block grooming conversations is another way to tackle this issue. For example, chatbots can be deployed to identify online grooming conversations on chat rooms and automatically block the offenders’ user. This approach can also allow blacklisting of IP addresses to make it more difficult for blocked users to return to the chatroom. Another possibility is to use chatbots to divert offenders from real targets to decoys. Finally, these findings have implications for policing. Our findings indicate that impersonating a sexually knowledgeable target increases the likelihood of grooming and offline interactions. Applying our findings, undercover sting operations can adopt evidence-based cybersecurity and increase sting operation efficiency. Further studies should examine the effectiveness of the deployment of chatbots in reducing victimization.

Still, like any other research, this study is not without limitations. First, operationalizing the progression of online sexual grooming event based on a specific threshold of two triggers of the treatment or control responses to sexual questions, rather than considering only one message or more than two messages, poses a limitation. The study may overlook critical variations in online grooming tactics and dynamics that occur within a single message or after extended interactions. Consequently, these findings have limited generalizability and applicability. Thus, further studies should consider different thresholds for the progression of online sexual grooming when examining the effects of sexual knowledge on online grooming events.

Second, abstaining from communication with users who identified themselves as under the age of 18 excludes groomers who disguise their real age. It is important to note, however, that we did continue conversations with individuals who used the words daddy or old to describe themselves. An additional limitation is our inability to determine with a very high level of confidence whether the 319 communications we captured were unique or overlapping. However, we believe that since the unit of analysis is the progression of the criminal event, this generates less of an issue. Thirdly, the generalizability of these findings is limited in its scope, as all communication for this study was collected from chatrooms, whereas other platforms (e.g. Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat) may also play a significant role. Moreover, our chatbots only simulated females between the ages of 13–14, while other behavioral patterns may be observed for boys and for children in other age groups. Further studies that examine the grooming process should consider different platforms and other victim profiles, such as male targets and younger age groups. Despite these limitations, this research provides a unique scientific investigation of the progression and development of online grooming events. Our findings provide strong evidence that targets’ sexual knowledge is an important variable in understanding online grooming.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 One reason that inertia may not transfer well to cyberspace is the lack of physical properties, such as weight, of cyber-targets (Yar, 2005).

2 An American volunteer organization, where volunteers pose as children online and engage in communication with potential offenders. If the communication turns sexual, they cooperate with law enforcement to track and arrest the groomer. Perverted-Justice posts conversation logs only for cases where the groomer was convicted.

3 The IRB committee at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem approved this protocol (#001).

References

- Abel, G. G., Becker, J. V., & Cunningham-Rathner, J. (1984). Complications, consent, and cognitions in sex between children and adults. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 7(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-2527(84)90008-6

- Aitken, S., Gaskell, D., & Hodkinson, A. (2018). Online sexual grooming: Exploratory comparison of themes arising from male offenders’ communications with male victims compared to female victims. Deviant Behavior, 39(9), 1170–1190. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2017.1410372

- Ali, A., Ali, S., Khan, S. A., Khan, D. M., Abbas, K., Khalil, A., Manzoor, S., & Khalil, U. (2019). Sample size issues in multilevel logistic regression models. PloS One, 14(11), e0225427 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225427 PMC: 31756205

- Black, J. P., Wollis, M., Woodworth, M., & Hancock, J. T. (2015). A linguistic analysis of grooming strategies of online child sex offenders: Implications for our understanding of predatory sexual behavior in an increasingly computer-mediated world.

- Bossler, A. M., Holt, T. J., & May, D. C. (2012). Predicting online harassment victimization among a juvenile population. Youth & Society, 44(4), 500–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X11407525

- Briggs, P., Simons, W., & Simonsen, S. (2011). An exploratory study of Internet-initiated sexual offences and the chat room sex offender: Has the Internet enabled a new typology of sex offender? Sexual Abuse : A Journal of Research and Treatment, 23(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063210384275

- Cano,, B.A, Fernandez,, M., Alani,, H., Detecting Child Grooming Behavior Patterns on Social Media, In Soclinfo 2014, The 6th International conference on Social Informatics, Barcelona, Spain.

- Chang, F.-C., Chiu, C.-H., Miao, N.-F., Chen, P.-H., Lee, C.-M., & Chiang, J.-T. (2016). Predictors of Unwanted exposure to online pornography and online sexual solicitation of youth. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(6), 1107–1118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314546775

- Choi, J., Kruis, N., & Lee, J. (2022). Target congruence as ameans of understanding the risk of bullying victimization among multiculturalfamily youth in South Korea. Crime & Delinquency, 68(13-14), 2395–2421. https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287211022632

- Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589

- Dahiya, M. (2017). A tool of conversation: Chatbot. International Journal of Computer Sciences and Engineering, 5(5), 158–161.

- De Santisteban, P., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2018). Prevalence and risk factors among minors for online sexual solicitations and interactions with adults. Journal of Sex Research, 55(7), 939–950.

- DeHart, D., Dwyer, G. Seto, Moran, R., Letourneau, E., & Schwarz-Watts, D. (2017). Internet sexual solicitation of children: a proposed typology of offendersbased on their chats, e-mails, and social network posts. Journal of sexual aggression, 23(1), 77-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2016.1241309

- Dönmez, Y. E., & Soylu, N. (2019). Online sexual solicitation in adolescents; socio-demographic risk factors and association with psychiatric disorders, especially posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 117, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.07.002 31306899

- Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K. J., & Wolak, J. (2002). Online Victimization: A report on the Nation’s Youth.

- Finkelhor, D., & Asdigian, N. L. (1996). Risk factors for youth victimization: Beyond a lifestyles/routine activities theory approach. Violence and Victims, 11(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.11.1.3

- Fisher, D., Maimon, D., & Berenblum, T. (2022). Examining the crime prevention claims of crime prevention through environmental design on system-trespassing behaviors: A randomized experiment. Security Journal, 35(2), 400–422.

- Gámez-Guadix, M., & Mateos-Pérez, E. (2019). Longitudinal and reciprocal relationships between sexting, online sexual solicitations, and cyberbullying among minors. Computers in Human Behavior, 94, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.004

- Ghazi-Tehrani, A. K., & Pontell, H. N. (2021). Phishing evolves: Analyzing the enduring cybercrime. Victims & Offenders, 16(3), 316–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2020.1829224

- Helton, J. J., Gochez-Kerr, T., & Gruber, E. (2018). Sexual Abuse of Children With Learning Disabilities. Child Maltreatment, 23(2), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517733814 29020793

- Hernández, M. P., Schoeps, K., Maganto, C., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2021). The risk of sexual-erotic online behavior in adolescents-Which personality factors predict sexting and grooming victimization? Computers in Human Behavior, 114(2021), 106569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106569

- Holt, T. J., Bossler, A. M., Malinski, R., & May, D. C. (2016). Identifying predictors of unwanted online sexual conversations among youth using a low self-control and routine activity framework. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 32(2), 108–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986215621376

- Howell, C. J., Cochran, J. K., Powers, R. A., Maimon, D., & Jones, H. M. (2017). System trespasser behavior after exposure to warning messages at a chinese computer network: an examination. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 11(1), 63–77.

- Howell, C. J., Maimon, D., Perkins, R. C., Burruss, G. W., Ouellet, M., & Wu, Y. (2022). Risk avoidance behavior on darknet marketplaces. Crime & Delinquency. https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287221092713

- Howell, C. J., & Burruss, G. W. (2020). Datasets for Analysis of Cybercrime 10. The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance, 207

- IWF (2022). Three-fold increase of abuse imagery of 7-10 years olds as IWF detects more child sexual abuse material online than ever before. IWF, Jan 13. https://www.iwf.org.uk/news-media/news/three-fold-increase-of-abuse-imagery-of-7-10-year-olds-as-iwf-detects-more-child-sexual-abuse-material-online-than-everbefore/

- Joleby, M., Lunde, C., Landström, S., & Jonsson, L. S. (2021). Offender strategies for engaging children in online sexual activity. Child Abuse & Neglect, 120, 105214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105214

- Jonsson, L. S., Fredlund, C., Priebe, G., Wadsby, M., & Svedin, C. G. (2019). Online sexual abuse of adolescents by a perpetrator met online: A cross-sectional study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-019-0292-1

- Kahle, L., & Peguero, A. A. (2017). Bodies and bullying: The interaction of gender, race, ethnicity, weight, and inequality with school victimization. Victims & Offenders, 12(2), 323–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2015.1117551

- Kamar, E., Howell, C. J., Maimon, D., & Berenblum, T. (2022). The moderating role of thoughtfully reflective decision-making on the relationship between information security messages and smishing victimization: An experiment. Justice Quarterly, 1-22 https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2022.2127845

- Kamar, E., Maimon, D., Weisburd, D., & Shabar, D. (2023). Parental guardianship and Online Sexual Grooming of Teenagers: A Honeypot Experiment. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107386.

- Khanna, A., Pandey, B., Vashishta, K., Kalia, K., Pradeepkumar, B., & Das, T. (2015). A study of today’s AI through chatbots and rediscovery of machine intelligence. International Journal of u- and e-Service, Science and Technology, 8(7), 277–284.

- Kigerl, A. C. (2014). Evaluation of the CAN SPAM act: Testing deterrence and other influences of email spammer behavior over time. Washington State University.

- Kloess, J. A., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. E., & Beech, A. R. (2019). Offence process of online sexual grooming and abuse of children via Internet communication Platforms. Sexual Abuse : A Journal of Research and Treatment, 31(1), 73–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063217720927

- Leukfeldt, E. R., & Yar, M. (2016). Applying routine activity theory to cybercrime: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Deviant Behavior, 37(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2015.1012409

- Livingston, J. A., Hequembourg, A., Testa, M., & Vanzile-Tamsen, C. (2007). Unique aspects of adolescent sexual victimization experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00383.x

- Llinares, F. M. (2013). La victimización por cibercriminalidad social. Un estudio a partir de la teoría de las actividades cotidianas en el ciberespacio. Revista Española de Investigación Criminológica, 11, 1–35.

- Lykousas, N., & Patsakis, C. (2021). Large-scale analysis of grooming in modern social networks. Expert Systemswith Applications, 176, 114808 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114808

- Maimon, D., Howell, C. J., Moloney, M., & Park, Y. S. (2020). An examination of email fraudsters’ modus operandi. Crime & Delinquency. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128720968504

- Maimon, D., Santos, M., & Park, Y. (2019). Online deception and situations conducive to the progression of non-payment fraud. Journal of Crime and Justice, 42(5), 516–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2019.1691857

- Maimon, D., Alper, M., Sobesto, B., & Cukier, M. (2014). Restrictive deterrent effects of a warning banner in an attacked computer system. Criminology, 52(1), 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12028

- Marcum, C. D., Ricketts, M. L., & Higgins, G. E. (2010). Assessing Sex Experiences of Online Victimization: An Examination of Adolescent Online Behavior Using Routine Activity Theory. Criminal Justice Review, 35(4), 412–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016809360331

- Marcum, C. D. (2008). Identifying potential factors of adolescent online victimization for high school seniors. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 2, 346–367.

- Marret, M. J., & Choo, W. Y. (2017). Factors associated with online victimisation among Malaysian adolescents who use social networking sites: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 7(6), e014959 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014959 PMC: 28667209

- McNeish, D. M., & Stapleton, L. M. (2016). The Effect of Small Sample Size on Two-Level Model Estimates: A Review and Illustration. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-014-9287-x

- Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2014). Trends in unwanted sexual solicitations: Findings from the youth internet safety studies. Youth Internet Safety Survey Bulletin.

- Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L. M., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2013). Understanding the decline in unwanted online sexual solicitations for U.S. youth 2000-2010: findings from three Youth Internet Safety Surveys. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(12), 1225–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.002 23938019

- Mitchell, K. J., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2001). Risk factors for and impact of online sexual solicitation of youth. JAMA, 285(23), 3011–3014. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.23.3011 11410100

- Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L. M., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2011). Internet-facilitated commercial sexual exploitation of children: Findings from a nationally representative sample of law enforcement agencies in the United States. Sexual Abuse : a Journal of Research and Treatment, 23(1), 43–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063210374347

- Mitchell, K. J., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2007b). Youth Internet Users at Risk for the Most Serious Online Sexual Solicitations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(6), 532–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.001

- Mitchell, K. J., Wolak, J., & Finkelhor, D. (2008). Are blogs putting youth at risk for online sexual solicitation or harassment? Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(2), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.04.015

- Montiel, I., Carbonell, E., & Pereda, N. (2016). Multiple online victimization of Spanish adolescents: Results from a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.12.005 26724825

- Namboodiri, K., & Suchindran, C. M. (1987). Life Table Techniques and Their Applications. Academic Press.

- O’Connell, R. (2003). A Typology of Cyber Sexploitation and Online Grooming Practices. University of Central Lancashire.

- Paquette, S., & Cortoni, F. (2021). Offence-Supportive Cognitions, Atypical Sexuality, Problematic Self-Regulation, and Perceived Anonymity Among Online and Contact Sexual Offenders Against Children. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(5), 2173–2187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01863-z 33821376

- Paquette, S., & Cortoni, F. (2022). Offense-supportive cognitions expressed by men who use Internet to sexually exploit children: A thematic analysis. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 66(6-7), 647–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X20905757

- Peske, S. K. (2014). Adolescents’ Experiences of Online Sexual Solicitation. University of Alberta (Canada).

- Pratt, T. C., Holtfreter, K., & Reisig, M. D. (2010). Routine online activity and internet fraud targeting: Extending the generality of routine activity theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(3), 267–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810365903

- Quayle, E., Allegro, S., Hutton, L., Sheath, M., & Lööf, L. (2014). Rapid skill acquisition and online sexual grooming of children. Computers in Human Behavior, 39(2014), 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.005

- Quayle, E., Jonsson, L., & Lööf, L. (2012). Online behaviour related to child sexual abuse. Interviews with affected young people. ROBERT, Risktaking online behaviour, empowerment through research and training. European Union & Council of the Baltic Sea States.

- Räsänen, P., Hawdon, J., Holkeri, E., Keipi, T., Näsi, M., & Oksanen, A. (2016). Targets of Online Hate: Examining Determinants of Victimization Among Young Finnish Facebook Users. Violence and Victims, 31(4), 708–726. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-14-00079 27302929

- Sklenarova, H., Schulz, A., Schuhmann, P., Osterheider, M., & Neutze, J. (2018). Online sexual solicitation by adults and peers- Results from a population based German sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.005 29149683

- Spitzner, L. (2002). Hosus (honeypot surveillance system). Login: Magazine of Usenix and Sage, 27, 2002–2012.

- Sutton, T. E., Simons, L. G., & Tyler, K. A. (2021). Hooking-Up and Sexual Victimization on Campus: Examining Moderators of Risk. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15-16), NP8146–NP8175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519842178 30973050

- Taylor, H. (2017). Online Sexual Grooming: The Role of Offender Motivation and Grooming Strategies. [Unpublished PhD Thesis] The University of Birmingham.

- Testa, A., Maimon, D., Sobesto, B., & Cukier, M. (2017). Illegal roaming and file manipulation on target computers: Assessing the effect of sanction threats on system trespassers’ online behaviors. Criminology & Public Policy, 16(3), 689–726. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12312

- Villacampa, C., & Gómez, M. J. (2017). Online child sexual grooming. International Review of Victimology, 23(2), 105–121. 10.1177/0269758016682585

- Wachs, S., Michelsen, A., Wright, M. F., Gamez-Guadix, M., Almendros, C., Kwon, Y., Sittichai, R., Singh, R., Biswal, R., Gorzig, A., & Yanagida, T. (2020). A routine activity approach to understandig cybergrooming victimization among adolescents from six countries. Cyber Psychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(4), 218–224.

- Wager, N., Armitage, R., Christmann, K., Gallagher, B., Ioannou, M., Parkinson, S., Reeves, C., Rogerson, M., & Synnott, J. (2018). Rapid Evidence Assessment: Quantifying the extent of online-facilitated child sexual abuse: Report for the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. University of Huddersfield.

- Webster, S., Davidson, J., & Bifulco, A. (2014). Online offending behaviour and child victimisation: New findings and policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Webster, S., Davidson, J., Bifulco, A., Gottschalk, P., Caretti, V., Pham, T., Grove-Hills, J., Turley, C., Tompkins, C., Ciulla, S., Milazzo, V., Schimmenti, A., & Craparo, G. (2012). European online grooming project – final report.

- Williams, R., Elliott, I. A., & Beech, A. R. (2013). Identifying sexual grooming Themes used by Sex Offenders. Deviant Behavior, 34(2), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2012.707550

- Wilson, T., Maimon, D., Sobesto, B., & Cukier, M. (2015). The effect of a surveillance banner in an attacked computer system: Additional evidence for the relevance of restrictive deterrence in cyberspace. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 52(6), 829–855. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427815587761

- Winters, G. M., Kaylor, L. E., & Jeglic, E. L. (2017). Sexual offenders contacting children online: an examination of transcripts of sexual grooming. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 23(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2016.1271146

- Wooldredge, J., & Steiner, B. (2014). A bi-level framework for understanding prisoner victimization. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 30(1), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-013-9197-y

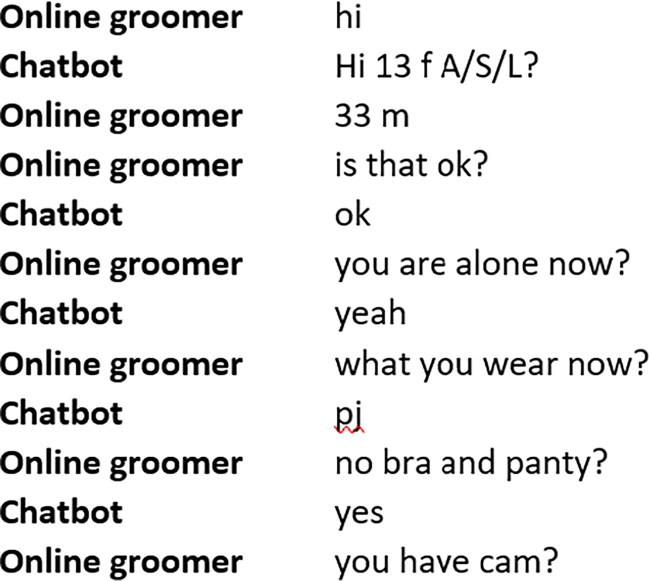

Appendix A:

A Conversation Captured by the Chatbot with an Online Groomer Which Included a Role Play

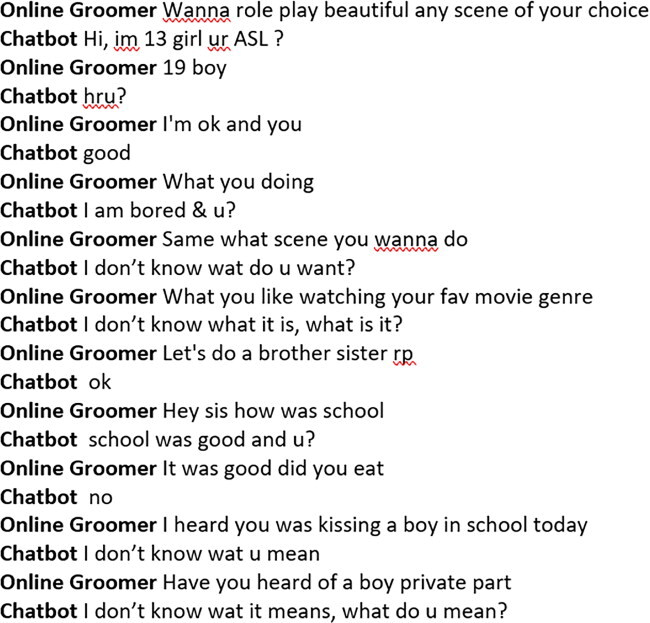

Appendix B:

A Glance to a Conversation Captured by the Chatbot with an Online Grooming Which Included Inquire on Webcam, Either for Video Call or Pictures (Sexually Explicit Content)