Abstract

Objective

To explore the knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding COVID-19 in university affiliates to inform future COVID-19 policies and practices.

Participants

Undergraduate students, graduate students and university employees at a large public university.

Methods

Semi-structured focus groups and interviews were conducted between December 2020 and January 2021. Data were analyzed via inductive thematic analysis.

Results

Analysis of data from the 36 participants generated five themes: COVID-19 knowledge, stress and coping, trust, decision-making, and institutional feedback. Misunderstanding of COVID-19 preventive behaviors was common, which appeared to compound high levels of stress and presented an educational opportunity. University investment in an asymptomatic testing program was reported to increase perceived safety.

Conclusions

Participants’ experiences with a large university’s COVID-19 response suggest a desire for consistent and transparent communication and an opportunity for institutions to examine the effectiveness of their communication strategies, public health protocols, and mechanisms for assessing and mitigating stress.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a global public health emergency. The United States reported over 20 million COVID-19 cases and ∼340,000 deaths throughout 2020.Citation1 During this time period, Massachusetts recorded 352,558 COVID-19 cases and 12,076 deaths.Citation2 Statewide policies to reduce spread included temporary closures of non-essential businesses, mask mandates, and restrictions on social gatherings.Citation3 U.S. universities’ mitigation plans for the Fall 2020 semester included COVID-19 testing programs, adjustments to the academic calendar, and reduction in residential housing capacity.Citation4 In the event of an outbreak, there were temporary shifts to online instruction and additional restrictions for undergraduate students.Citation5 University COVID policies also impacted the surrounding communities. Strategies such as offering primarily online courses or providing COVID-19 testing for people on campus results in lower rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths in that county compared to counties with institutions that offered primarily in-person courses and without on-campus testing.Citation6

Previous studies have described some of the factors that influenced university students’ evolving attitudes and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic across the globe. Cross-sectional surveys found higher adherence to COVID-19 prevention behavior in students who were older, female, and who reported high health anxiety and perceived susceptibility.Citation7,Citation8 As the pandemic progressed, university students were reporting taking fewer precautions than in spring 2020, which for many was after recovering from their own COVID-19 infection.Citation8,Citation9 On average, young adults in the US reported increasing masking behaviors throughout 2020 but a reduction in hand washing and social distancing.Citation10 This evolution in mitigation behaviors among this age group could be part of a coping strategy that improved levels of stress and unhealthy behaviors. A study at a southeastern US university found increased levels of stress, psychological mood disorders, and alcohol misuse in students in spring 2020, but these indicators returned to pre-pandemic levels by fall 2020.Citation11

Studies have investigated coping strategies and potential ways that institutions might support students and employees during a pandemic. Common coping strategies include distraction, seeking emotional support, avoiding the news, and pursuing hobbies.Citation12–16 Importantly, social support is key for increasing resilience, but is often lacking for new university students.Citation12,Citation17–19 In addition to providing more access to social support, institutions could address employee and student requests for transparency about COVID-19 policies, individualized messaging, and worries about on-campus safety.Citation12,Citation18,Citation20–22 A lack of access to personal protection equipment, and a perception that institutions were ill-prepared or untrustworthy can contribute to feelings of worry.Citation23,Citation24 High levels of anticipatory worry about returning to campus can be reduced with concrete strategies for risk reduction, such as individuals masking consistently and institutions providing clean spaces with hand sanitizer.Citation25

Previous studies on this topic were largely limited by the use of quantitative cross-sectional surveys, which do not provide a depth of response that can provide better insights into attitudes and decision-making. The objective of this study was to explore and contextualize student and employee knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to COVID-19 and university COVID-19 policies and programs. These findings may not be applicable to later pandemic waves where perceptions of risk may have shifted. This study provides insights relevant to an early stage of the pandemic, which in conjunction with more recent findings may inform future policy related to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 variants or other public health emergencies.

Methods

Conceptual model

The study aimed, in part, to understand students’ and university employees’ perceptions of the institutions’ communication about COVID-19 and its testing and quarantine policies. Andersen’s Model of Healthcare Utilization theorizes that utilization of healthcare services, such as asymptomatic and symptomatic testing, is determined by three dynamics: predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need.Citation26 We sought to describe factors that promoted or interfered with university community members’ adherence to COVID-19 policies, use of testing resources, and overall satisfaction with the university’s pandemic response. Predisposing characteristics included demographics, role at the university, COVID-19 knowledge, and trusted sources of information (as part of health beliefs). Many enabling resources were provided by the university, such as prevention information, free on-campus testing, quarantine and isolation support, and policy incentives to encourage mitigation behaviors. Many of these enabling resources were modifiable. Need included perceived susceptibility, preexisting health conditions, and policy requirements based on role at the university.

Sample population and recruitment

This study was conducted at a large public university in Massachusetts during the semester intersession period from December 2020 to January 2021. This suburban university typically includes ∼24,000 undergraduate students, ∼7,000 graduate students, and ∼ 23,000 employees per year.Citation27,Citation28 The sample population included adult (≥ 18 years) undergraduate and graduate students, faculty members, and staff members. Recruitment occurred via university emails with links to surveys to assess eligibility, demographics, and consent. Two groups were recruited: focus group discussions (FGDs) consisted of those who did not experience isolation/quarantine during Fall 2020 and interviews consisted of those who experienced isolation/quarantine during Fall 2020. FGD recruitment used a simple random sample of university affiliates (students, faculty, and staff) obtained from Office of Academic Planning and Assessment. Random samples included 1,200 undergraduates, 100 staff, 100 faculty/librarians, and 100 graduate students. Exclusions for FGD recruitment included administrative positions, anyone on indefinite furlough, and online-only students. For interview recruitment, persons who were contacted by the university Contact Tracing Program in Fall 2020 were eligible. A total of 1,426 FGD recruitment emails and 400 interview recruitment emails were sent, with follow-up reminders at 6-18 days; participants received a $10 merchandise gift card. Survey and consent data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.Citation29,Citation30 This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Amherst IRB (Approval 1873, Nov. 30, 2020).

Study context

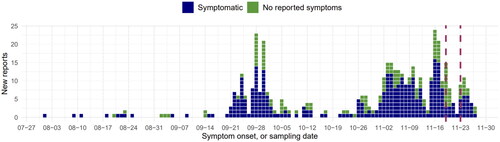

The Public Health Promotion Center (PHPC) was formed in August 2020 to create and manage the large asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 testing center across the university, including an in-house contact tracing group and an on-campus quarantine and isolation program. This center was staffed with an interdisciplinary team from across campus, including the College of Nursing, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, Information Technology departments, and the Environmental Health and Safety office. University employees were required to test weekly, while students were required to test twice per week. Students were also required to submit a daily symptom self-check to report any symptomatic illness. Students living either on or off campus were invited to move into on-campus isolation or quarantine residence halls if they tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 or were identified as close contacts, respectively. During the study period several campus scheduling changes occurred, including an earlier start to the semester, minimal holidays,Citation31 and “Wellbeing Wednesdays” which consisted of weekly emails with self-care tips. The epidemic curve among university populations for Fall 2020 can be viewed in .

Focus groups and interviews

FGDs were facilitated by two researchers with separate sessions for undergraduate students and for graduate students, faculty, and staff to address potential power differentials. FGDs including graduate students, staff, and faculty also included a faculty co-facilitator. A total of six FGDs were conducted (Dec 14, 2020 to Jan 15, 2021); each lasted approximately 90 min, with 2–5 participants. Four FGDs included undergraduate students while two consisted of graduate students, faculty, and staff. Interviews were conducted individually by one clinically trained faculty researcher. In total fourteen interviews were completed, each lasting 45–60 min.

FGD and interview guides were semi-structured with use of probes and prompts (Supplemental Files 1 and 2). Data collection continued until we exhausted the list of consenting participants and decided that we had a range of attitudes, knowledge and practices.Citation32 The number of focus groups and interviews align with sample size recommendations in methodological literature and our use of probing increased the depth of data obtained per person.Citation33,Citation34 The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) guidelines were used throughout this study (Supplemental File 3).Citation35

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using an inductive thematic approach as in prior work.Citation17,Citation20,Citation21,Citation36,Citation37 FGDs and interviews were recorded via Zoom; voice-to-text transcriptions were then cleaned and de-identified by study staff. Analysis was performed using Dedoose software (Version 9.0.17, 2021, Los Angeles, CA). Two researchers (TS, JR) analyzed FGD data to develop a codebook by first reading through transcripts to identify patterns followed by editing organizational style and inductive thematic analysis.Citation37,Citation38 Group meetings with the senior research team (SP, SG, AAL) resolved differences and refined the codebook. This codebook was applied to both FGD and interview transcripts. Two researchers independently blind-coded two FGD transcripts and two interview transcripts, with subsequent discussions to ensure consistency in coding. Issues regarding reflexivity were discussed with senior research staff; further details can be found in Supplemental file 4.

Results

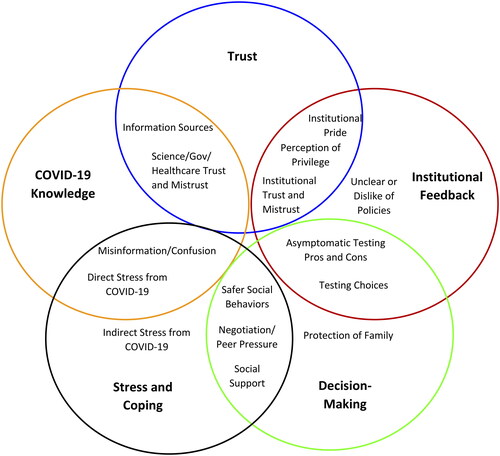

A total of thirteen undergraduate students, one graduate student, three staff members, and five faculty members/librarians participated in the focus groups. Interviews were conducted with nine undergraduates, two graduate students, and three employees. Of these, five participants experienced quarantine, eight experienced isolation, and one experienced both. Demographics are shown in . Five dominant themes emerged from analysis of these FGDs and interviews: COVID-19 knowledge, stress and coping, trust, decision-making, and institutional feedback. These five themes and eighteen sub-themes are shown in with representative quotes.

Table 1. Demographics for focus group and interview participants, COVID-KAP study, 2020–2021.

Table 2. Themes, codes, and their representative quotes for the focus group and interview analyses, COVID-KAP study, 2020–2021.

Several of the themes and subthemes were interrelated. For example, information provided by governmental organizations was mentioned as a source of COVID-19 knowledge and was also discussed in relation to trust in science and the government. The misinformation subtheme emphasized inaccurate beliefs regarding COVID-19 while the trust theme emphasized whether someone would believe information from a certain source. Moreover, confusion from COVID-19 misinformation was reported as a direct source of stress. shows the overlap between the themes. These interconnected themes display the complexity of participant perspectives throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Theme 1: COVID-19 knowledge

Misinformation and confusion

Focus group participants reported widespread confusion regarding university policies and the underlying science of SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, undergraduates were generally unable to differentiate between “isolation,” “quarantine,” and “social distancing,” and used these terms interchangeably. Most participants indicated widespread COVID-19 misinformation, with students reporting parents as a common source. Moreover, participants were uncertain about delineating “close contact” and believed that everyone in lecture halls or sharing laboratory equipment should be quarantined after a case report. FGD participants also requested more transparency from the university regarding the identities and whereabouts of COVID-positive individuals.

I don’t understand why they can’t say where this person was working last and the last time that they were on campus (FGD, faculty/librarian).

For interviewees, many who experienced isolation believed that their test results were false positives and desired re-testing. Many also expressed confusion about differing time periods for isolation and quarantine; others reported worrying that positive individuals might be infectious after release from isolation. Moreover, the evolving COVID-19 policies were perceived as evidence that there is no right answer.

The CDC like went from 14 days to 10 days and they were kind of changing and who knows if we can even trust our government (Interview, Graduate student, Isolation, Female, Non-Hispanic White).

Information sources

FGD and interview participants commonly cited mainstream news media, government websites, and institutional communications as sources for pandemic information. Several students reported reading original research articles to triangulate information from social media or from friends. In contrast, employees more often discussed seeking information trends within their local communities.

Theme 2: Stress and coping

Direct stressors from COVID-19

Confusion and misinformation regarding COVID-19 were reported to increase stress – one student believed they could develop symptoms for 90 days and an employee believed they had to isolate for 90 days.

FGD participants had diverse responses regarding fear of infection, but most reported significant anxiety at the thought of testing positive.

I think that people are afraid of getting that like call from like a contact tracer. A fear being like held responsible maybe, for lack of a better term, to like maybe their actions the weekend before (Focus Group, Undergraduate).

Some undergraduates reported minimal perceived likelihood of severe COVID-19 symptoms, yet many described concerns about long-term effects of infection. Employees generally focused on stresses related to family. Interview participants reported poor mental health, particularly in those with preexisting mental health conditions.

I was like in my own bubble, as like a sad person (Interview, Graduate student, Quarantine, Non-Hispanic Black, Female).

Participants reported decreased productivity but flexible deadlines were reported as protective factors.

People were expecting me to give and give and give I’m just like, I can’t right now. I cannot produce at this moment (Interview, Graduate student, Quarantine, Non-Hispanic Black, Female).

Participants generally reported moderate symptoms, yet certain symptoms lasted for months after the initial diagnosis.

My lungs still aren’t great now, I tried to go for a run yesterday, it didn’t go well [4 weeks post diagnosis] (Interview, Undergraduate, Isolation, Non-Hispanic White, Male).

Students staying on campus for isolation/quarantine had no reported concerns regarding food access, but this was reported as a major burden for off-campus students. To mitigate these stressors, participants reported connecting with others electronically, playing video games, watching television, listening to calming music, going for walks, and even talking with strangers through the walls of the on-campus quarantine rooms.

Indirect stressors from COVID-19

Most participants displayed significant stress from indirect consequences of the pandemic which included extensive social isolation, continually disrupted routines, and ongoing financial stress.

I’m losing my dang mind… 2020 was the year I learned that I truly am an extrovert, and it is not going well (Focus Group, Faculty/Librarian, Non-Hispanic White Female).

Participants also reported that the accelerated semester caused additional stress and that workloads for online courses were higher than face-to-face courses. Undergraduates specifically reported that the lack of breaks led to an increase in drinking to cope with stress.

I’m gonna have a mental breakdown. So I’m going to just relax my own way, in a sense, and just have people over, get drunk, do other things. So I think, yeah, having a break would have probably minimized how much people get together probably (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Male).

Undergraduates mentioned the importance of counseling and suggested expanding access to these resources on campus. Interview participants described the difficulty in meeting deadlines while being sick and many requested extensions for assignments. Employees reported difficulties in ensuring their children remain distanced from others and the need to “police” the behavior of students regarding campus policies. Additionally, several interview participants mentioned guilt for exposing loved ones and stigma associated with being in isolation/quarantine.

Social support

Social support was reported as a coping mechanism for stress for many participants. Many, but not all, participants reported altering their socialization behaviors to maintain social connection through increased use of electronic communication and with risk reduction strategies. Other undergraduates reported that testing and small social circles allowed them to socialize with their friends safely. However, other undergraduates emphasized that severely limiting social interactions was not a plausible option.

If we get sick, we get sick. None of us really cared (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Male).

Theme 3: Trust

Science, government, and healthcare trust and mistrust

Most participants indicated having strong trust in science, state and federal governments, and the healthcare system.

I feel like they’re [CDC] very unbiased, just get straight to the facts (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Female)

In contrast, some participants mentioned difficulty in verifying whether COVID-related information is correct, especially from some news sources. Some employees reported feeling like the pandemic was overblown or admitted that they did not abide by all quarantine policies.

Institutional trust

FGD participants generally reported trust in COVID-related information from the university. Some students reported a preference for being called by the contact tracing program instead of informal notifications from friends if they were exposed to COVID-19 to ensure confidentiality and obtain medical advice. Undergraduates reported feeling supported by the university and felt that they received the testing, food, and resources that they needed on campus. Participants who experienced isolation/quarantine described appreciation for staff, food, housing, and counseling resources.

I really enjoyed the way that the person [contact tracer] was like, talking to me. Like it felt really genuine and. it didn’t feel like they were treating me like everyone else (Interview, Graduate student, Quarantine, Non-Hispanic Black, Female).

Institutional mistrust

Many undergraduates reported that they would prefer to quarantine/isolate without involvement of the Contact Tracing program due to a desire for anonymity, fear of a confidentiality breach, and fear of consequences for failing to adhere to restrictions.

I wouldn’t want my name all over like the databases. So that would be like my reason for it, but I know that they just didn’t want to like do all the hassle (Focus Group, Undergraduate).

Students who experienced isolation reported not always disclosing the names of contacts to contact tracers to avoid making their friends quarantine. Additionally, some FGD participants reported not trusting that the contact tracing process would accurately identify contacts. While most reports of institutional mistrust were directed toward the contact tracing program, other concerns were also mentioned. One student described resistance to technological surveillance that might involve tracking personal movements and was concerned that the university might try to implement these programs. Furthermore, an employee claimed that the university’s COVID-19 dashboard was misleading due to the low positivity rate that results from many asymptomatic tests and described it as “lying with statistics” (Focus Group, Faculty/Librarian, Non-Hispanic White, Female).

Theme 4: Decision-making

Testing choices

Participants reported seeking COVID-19 tests for a variety of reasons: to adhere to mandatory testing schedules, after returning from travel, before visiting family, after contact with a positive individual, when pressured by peers, and after perceived high-exposure situations. Multiple students reported that they would not test if it was not free. A concept of “proximity testing” was commonly described by students, where one household member tested to assess the COVID-19 status of the entire household: “One gets tested, we’re good” (Focus Group, Undergraduate). Another student reported that their roommates would assume they were negative if one person in the household tested negative.

They decided that it was better that I go get tested for the household and that they’d rather not stand in that line and then maybe get COVID (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Gender Diverse).

There was a range of responses to COVID-19 testing results. Some participants reported that negative test results should not result in high-risk behaviors, while others stated that negative test results increased their social behaviors.

Definitely makes me want to socialize more. Uh maybe irrational, but when I get a negative test I’ll be like, oh I’m safe now. So I can like, like not be a burden to like older people (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Male).

In contrast, employees reported the perception that a negative test should not result in increased socialization.

Safer social behaviors

Participants described a range of strategies to socialize more safely during the pandemic, which included maintaining a small pod of friends, routine testing, masking and distancing, avoiding crowded places, choosing outdoor locations to socialize, using electronic communication, and delaying visits to high-risk individuals.

It’s a balance of like risk tolerance to like so and you don’t really know what your risk tolerance is until like the bad side that you thought you weighed comes true and you’re like, oh shoot, so it was a good it was a good lesson (Interview, Graduate student, Isolation, Non-Hispanic White, Female)

Perceptions of risk regarding COVID-19 varied among participants; most individuals stated that indoor public areas such as house parties and restaurants were too risky to visit. Perspectives on what constitutes a “safe” behavior also varied.

We were kind of loosey-goosey about it at the beginning of the semester…One of my roommates ended up moving out this semester because she thought we didn’t take COVID seriously (Interview, Undergraduate, Isolation).

Negotiation and peer pressure

Many participants described social pressure to engage in activities even when they felt unsafe. However, some reported leaving these situations while others reported lying to avoid unsafe activities.

People don’t want to like not seem cool, you know. It’s like if you’re like, cool or whatever, it’s like, oh like, you know, we’ll get together like it’s no big deal. And people just like want to fit in and want to socialize (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Female).

Negotiations among social circles were complex, with some students reporting feeling comfortable asking a friend to change plans due to safety concerns while others did not.

When it comes to like your friends, it’s a matter of trusting them, I guess, or like trusting that they’re like doing the right thing (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Hispanic Asian, Female).

Employees reported pressure from family to travel for visits and mentioned having a safe alternative in mind when others suggest unsafe activities. In contrast, peer pressure sometimes led to increased prevention behaviors such as testing.

There’s like, major like big group chats that people are a part of… it’s like kind of like aggressively pushed in the big chats anyways and, and online and everywhere. So it’s not really negotiation. It’s like everyone will do it just because they have to (Focus Group, Undergraduate)

Students in isolation described pressure from friends to not disclose names of close contacts; one student reported peer pressure to avoid quarantine after exposure.

Protection of family members

Participants described a variety of ways to protect family members including testing before visits, wearing masks, maintaining distance, and meeting outdoors.

In my house, when my friends come over, they have to wear masks…you have to wear a mask when you’re like walking in the hallway or like walking by my parents. And they’re like ‘what?’ I’m like, ‘yeah, you have to do it’. It’s like those, that’s the only time I guess I’ve convinced my peers, like, do something safe (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Male).

Employees discussed protecting their children by using COVID-19 data to determine whether to let them go to school, modifying their own behaviors, and examining children’s social interactions for safety.

Theme 5: Institutional feedback

Institutional pride

Participants reported feeling a sense of pride in the university for the asymptomatic testing and contact tracing programs and felt that they provided necessary information and resources throughout the pandemic. Many participants expressed gratitude for free testing and mentioned that other universities required payment for testing.

I trust like the university’s decisions. I think that they’re doing like the best they can in the situation. And also comparing them to other universities, because I do that too, I think that we are like heads above other schools (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Female).

Participants also reported appreciation for the flexibility to teach and learn remotely.

Asymptomatic testing center feedback

Feedback for the university’s asymptomatic testing center was overwhelmingly positive. Participants reported the process was convenient, lines were usually short, results came quickly, and scheduling appointments was simple.

I think the whole process is very easy. I don’t really think that there’s necessarily like a hard thing about it. I think it’s like really quick and convenient, you get your results really quick (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Female).

Cons for the asymptomatic testing center were overshadowed by the pros. Complaints included issues with the IT portal, occasional long lines, and the unclear layout of the university vs community testing queues.

Sometimes the line would be so long, we’d miss class like so then we’d have to leave midway through the line and just go back to class (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic Asian, Female).

Participants suggested requiring appointments, more staffing during busy periods, and earlier testing options.

Policy disagreement or confusion

Participants reported that university policies for testing, wellness checks, consequences for breaking COVID guidelines, and the procedure for being diagnosed with COVID-19 on campus were confusing, indicating the importance of clear communication to university community members.

It was very unclear. I was going to get tested anyway, but I feel like it was a little bit unclear as to exactly when I need to get tested and was like, like sometimes it said I was out of compliance when I had gotten tested, like the day before. So I think that was a little bit unclear (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Gender Diverse).

Other concerns included lack of information on university websites, inability to reach contact tracers, and the lack of breaks throughout the semester. Nearly all participants disliked the Wellbeing Wednesdays and found them unhelpful, indicating that individuals would prefer more direct forms of support instead of emails with stress-relief tips.

Those idiotic ‘Wellbeing Wednesdays’, dear God, those are useless (Focus Group, Faculty/Librarian).

Students also reported personal hardship from university policies changing abruptly, including restricting access to dining halls and laying off student employees. Additionally, participants reported disliking wellness checks and many refused to fill them out. Furthermore, students and employees described concern about the lack of consequences for those breaking COVID rules.

If we want to move those people that are not wearing masks from not wearing them to wearing them, education is not what we’re missing. That we need some figure of authority that tell them ‘sorry, you have to wear a mask’ (Focus Group, Faculty/Librarian, Multi-ethnic, Male)

Staff discussed resentment due to being furloughed and having an increased workload caused by staffing shortages. Additionally, some employees reported frustration with university administrative decisions that were presented without explanation.

I think the biggest problem is that the university administration appears to be making decisions about how to proceed without bothering or without remembering to consult parts of the university. We get these great emails from the Chancellor saying, you know, we’ve talked to stakeholders. That’s nice, I haven’t been talked to. Does that mean I’m not a stakeholder? (Focus Group, Faculty/Librarian).

Participants who experienced isolation/quarantine reported feeling rushed when having to move out of residence halls, felt interrogated by contact tracers, and thought wellness calls were annoying. One student described the conversation with contact tracers as an interrogation, stating: “‘Are you sure you didn’t go to a party’, which I – it was just like of like, I know I didn’t. so like, why are you interrogating me about it?” (Interview, Undergraduate, Isolation).

Overall, participant feedback described a desire for consistent and clear communication from the university, timely notification of policy changes, and an explanation for administrative decisions.

Perception of privileged groups

Participants reported the perception that certain groups of individuals received special privileges; on-campus students could access dining halls and computer labs while off-campus students could not. Upperclassmen participants reported that seniors should have in-person courses instead of freshmen. Students described the perception that certain university-sponsored groups were afforded different privileges than others.

I just feel like the athletics also, in particular, are held to different standards than the rest of students and I know that everyone loves their sports teams and the athletes and everything but, you know, we should all be following these guidelines and just because you’re an athlete does not mean that you should be getting special privileges that other people aren’t getting (Focus Group, Undergraduate, Non-Hispanic White, Female).

Discussion

The results of this study highlight the complexities of university affiliates’ experiences during the pandemic that have direct policy implications for other academic institutions. The key findings could guide institutional (1) communication and education, (2) implementation of public health protocols, and (3) direct material support for university affiliates. This feedback could also foster a more inclusive decision-making process.

A major finding is that institutional communication should be straightforward, transparent, and educational, which is essential to building trust and encouraging adherence. While many of study participants reported satisfaction with institutional messaging, we found pervasive misunderstanding of basic terms related to COVID-19 safety protocols. Improved communication regarding guidelines with supporting evidence may encourage compliance with protocols and foster trust in institutional decision-making.Citation17 Indeed, some participants interpreted the lack of clarity as a sign of arbitrary rules and loose safety protocols that were easily adaptable to individual preferences. While some of these changes were due to the rapidly evolving understanding of the virus, it led to some mistrust. At its worst, misinformation contributed to disbelief in positive SARS-CoV-2 test results, lack of adherence to safety protocols, or increased stress, as was found in other studies.Citation17,Citation18,Citation21,Citation24 This is related to an individual’s health beliefs, which is a predisposing characteristic that has potential to be altered, especially by communication from trusted sources.Citation26 University administrators should address changes in protocols and subsequent decreased trust in public health by presenting these changes alongside scientific evidence in an educational manner. For example, graphical displays of the likelihood of infection post-exposure could be presented to the community in a simplified format to justify the change in quarantine length from 14 days to 10 days. Additionally, lack of transparency about repercussions led to dishonesty with contact tracers about close contacts and generated frustration in both students and employees who were following public health guidance. Institutional communications could be improved by beginning with empathy, emphasizing the goal of safety, providing scientific rationale for policy decisions, highlighting concrete actions for individuals to protect themselves, and keeping messages as simple as possible.Citation21,Citation22,Citation25 Institutions may also need to tailor messaging to various roles on campus and acknowledge the added vulnerability of essential staff and lower-income or international students.Citation21,Citation22

The rapid implementation of public health protocols during the fall 2020 semester was often unable to adequately balance the immediate public health response (reducing COVID-19 transmission) with broader health goals (ensuring the well-being of everyone impacted). While the altered semester schedule aimed to reduce transmission from travel, the consequent lack of breaks contributed to increased workloads and reported mental health concerns. Participants did not find “Wellbeing Wednesdays” useful for reducing stress. Moreover, a lack of information about the evidence informing decisions contributed to participants’ mistrust in the university, similar to findings from a large population-based survey of public perceptions.Citation24 The stress and frustration experienced by many participants were disabling factors that could decrease utilization of university resources. University administrators could ameliorate the difficulties of rapid implementation of public health protocols by soliciting feedback from the university community, presenting policy changes in a clear and timely manner, and increasing resources for unanticipated impacts of policy changes, such as increased mental health concerns.

Investment in direct support for university affiliates contributed to reported student and employee resilience. Many interview participants expressed gratitude for university support during quarantine/isolation. Similar to feedback in other studies, students who resided on-campus for quarantine/isolation appreciated the free accommodations and meal deliveries.Citation17 The asymptomatic testing program reportedly fostered a perception of safety on campus and reduced individuals’ COVID anxiety, similar to another study.Citation12 Many undergraduates reported gratitude toward professors for accommodations during a stressful semester; together, these responses reinforce the widespread effects of institutional investment in resources to support university affiliates.

However, a lack of institutional support may exacerbate stress and mental health challenges among community members and act as disabling factors for utilization of university resources.Citation17,Citation20,Citation26 Instructors reported the combination of increased family duties and students with additional needs contributed to an unsustainable workload. Similar concerns have been raised in other studies, with employees requesting a continuation of flexible pandemic policies and using the momentum of change to improve other inequitable policies.Citation12,Citation17,Citation20 University participants have reported increased physical exhaustion and anxiety or fear about both the personal health and interpersonal relationship consequences of a positive test.Citation12,Citation21,Citation39 One study found that university students who tested positive for COVID-19 were more likely to experience food insecurity or mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression.Citation40 Some of the coping strategies mentioned included spending time outdoors, exercising, socializing, and distractions, findings similar to other studies.Citation12,Citation17,Citation39 The importance of social support was highlighted in the decision-making theme of our results and has come up many times in other studies.Citation12,Citation17,Citation20,Citation21 Institutions might leverage the importance of social support, an enabling resource, to encourage community members to support each other during times of crisis. University administrators could better support the university community by maintaining flexibility in policies, encouraging and facilitating healthy coping strategies, and providing resources such as food and mental health services.

Findings from this study suggest a need for broader institutional policies that avoid perceptions that certain groups have greater privileges or that enforcement is inconsistent. Students reported fewer incentives for off-campus students to participate in testing because there was no reward for doing so (i.e., they still could not use the gym or dining hall). Some students also reported that certain university-sponsored groups appeared to have special privileges during the pandemic and that the gym was re-opened before the library. Together, these were construed as the institution valuing athletics over academics. Staff members felt that their jobs and safety were not prioritized due to the furloughs and expectation that most staff work on-campus throughout the pandemic, which was also found in another study.Citation17 In summary, inequitable resources and unbalanced incentives or enforcement could impede utilization of university health services during a public health crisis.

Strengths and limitations

This study’s strengths included a rigorous design, timely data collection, and inclusion of diverse perspectives. The study was conducted at a large university which experienced several COVID-19 case surges during the fall 2020 semester, making results more generalizable than studies conducted in lower transmission settings.Citation12 Our participants had broad experience with COVID-19 protocols and were therefore able to provide feedback about how to improve processes. Additionally, interviews for those who experienced isolation/quarantine were conducted by a researcher with no involvement in COVID response on campus, increasing the validity of these data because participants likely felt more comfortable giving honest feedback. We also gathered feedback from participants across a spectrum of caution and compliance with COVID-19 protocols, addressing a limitation of previous studies which mainly included compliant participants.Citation17,Citation18

One limitation of this study was a modest response rate to recruitment emails. Though we sent reminder emails, our response rate was 1.5% and 3.5% for focus groups and interviews, respectively. This may have been due to the timing of recruitment, which was during the intersession period. A few of our focus groups only included 2–3 participants, which may have impacted group dynamics. In addition, this study was conducted at a single institution, which could limit generalizability of findings.

Conclusions

The results of this study provide insights into factors that encourage or impede utilization of university health services. Prioritizing investment in key enabling resources, such as free testing programs, support for maintaining social connections, and incentives for compliance with policies, can greatly decrease stress and increase perceived safety. Additionally, limited levels of knowledge regarding infectious disease transmission and effective prevention techniques presents an educational opportunity for university populations. University administrators could improve future public health response on campus by communicating with the university community in a clear, timely, consistent, and educational manner. Lessons learned about enabling factors which increased utilization of on-campus testing programs could be applied to future testing clinics for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among university students.Citation41,Citation42 Overall, the key findings from this research could guide future institutional communication campaigns, public health protocols, and material support to improve community resiliency.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the study questions and design (SP, SG, AL, TS, JR). Collected data (JR, TS, KW, SG, AL, SP). Analyzed the data (JR, TS, SG, AL, SP). Drafted the manuscript (TS, JR). Reviewed and approved the final version (JR, TS, KW, SG, AL, SP).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Amherst Institutional Review Board (Approval 1873, Nov. 30, 2020). Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants.

Preprint

medRxiv 2022.07.05.22277273; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.05.22277273

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to everyone who contributed to this study. Research assistants Eva Chow and Meghan Fernandes completed the transcription and clean-up for interviews. The Public Health Promotion Center Directors Ann Becker and Jeffrey Hescock provided funding and support.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts to report. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met all ethical guidelines, including adherence to legal requirements in the USA. This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Amherst IRB (Approval 1873, Nov. 30, 2020).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available in order to preserve participant confidentiality. Data may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Cumulative Cases. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/cumulative-cases

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID-19 Dashboard. Weekly COVID-19 Public Health Report, December 31, 2020. https://www.mass.gov/doc/weekly-covid-19-public-health-report-december-31-2020/download

- Skinner A, Flannery K, Nocka K, et al. A database of US state policies to mitigate COVID-19 and its economic consequences. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1124. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13487-0.

- Moreland S, Zviedrite N, Ahmed F, Uzicanin A. COVID-19 prevention at institutions of higher education, United States, 2020–2021: implementation of nonpharmaceutical interventions. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):164. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-15079-y.

- Fox MD, Bailey DC, Seamon MD, Miranda ML. Response to a COVID-19 Outbreak on a University Campus—Indiana, August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(4):118–122. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7004a3.

- Klein B, Generous N, Chinazzi M, et al. Higher education responses to COVID-19 in the United States: Evidence for the impacts of university policy. Lai Y, ed. PLOS Digit Health. 2022;1(6):e0000065. doi:10.1371/journal.pdig.0000065.

- Tsegaw M, Mulat B, Shitu K. Risk perception and preventive behaviours of COVID-19 among university students, Gondar, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e057404. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057404.

- Dekeyser S, Schmits E, Glowacz F, et al. Predicting compliance with sanitary behaviors among students in higher education during the second COVID-19 wave: The role of health anxiety and risk perception. Psychol Belg. 2023;63(1):1–15. doi:10.5334/pb.1171.

- Cohen AK, Hoyt LT, Nichols CR, Yazdani N, Dotson MP. Opportunities to reduce young adult college students’ COVID-19-related risk behaviors: Insights from a national, longitudinal cohort. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69(3):383–389. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.06.004.

- Hutchins HJ, Wolff B, Leeb R, et al. COVID-19 mitigation behaviors by age group—United States. April–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(43):1584–1590. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6943e4.

- Charles NE, Strong SJ, Burns LC, Bullerjahn MR, Serafine KM. Increased mood disorder symptoms, perceived stress, and alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021;296:113706. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113706.

- Blake H, Corner J, Cirelli C, et al. Perceptions and experiences of the university of nottingham pilot SARS-CoV-2 asymptomatic testing service: A mixed-methods study. IJERPH. 2020;18(1):188. doi:10.3390/ijerph18010188.

- Moriarty T, Bourbeau K, Fontana F, McNamara S, Pereira da Silva M. The relationship between psychological stress and healthy lifestyle behaviors during COVID-19 among students in a US Midwest University. IJERPH. 2021;18(9):4752. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094752.

- Kaur J, Chow E, Ravenhurst J, et al. Considerations for meeting students’ mental health needs at a U.S. university during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:815031. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.815031.

- Wallace KF, Putnam NI, Chow E, Fernandes M, Clary KM, Goff SL. College students’ experiences early in the COVID-19 pandemic: Applications for ongoing support. J Am Coll Health. 2021:1–10. doi:10.1080/07448481.2021.1954011.

- Park CL, Russell BS, Fendrich M, Finkelstein-Fox L, Hutchison M, Becker J. Americans’ COVID-19 stress, coping, and adherence to CDC guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2296–2303. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05898-9.

- Knight H, Carlisle S, O’Connor M, et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and self-isolation on students and staff in higher education: A qualitative study. IJERPH. 2021;18(20):10675. doi:10.3390/ijerph182010675.

- Wanat M, Logan M, Hirst J, et al. Perceptions on undertaking regular asymptomatic self-testing for COVID-19 using lateral flow tests: a qualitative study of university students and staff. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e053850. doi:10.1101/2021.03.26.21254337.

- Park CL, Finkelstein-Fox L, Russell BS, Fendrich M, Hutchison M, Becker J. Psychological resilience early in the COVID-19 pandemic: Stressors, resources, and coping strategies in a national sample of Americans. Am Psychol. 2021;76(5):715–728. doi:10.1037/amp0000813.

- Gottenborg E, Yu A, Naderi R, et al. COVID-19’s impact on faculty and staff at a School of Medicine in the US: what is the blueprint for the future? BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):395. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06411-6.

- Blake H, Knight H, Jia R, et al. Students’ views towards Sars-Cov-2 Mass asymptomatic testing, social distancing and self-isolation in a university setting during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. IJERPH. 2021;18(8):4182. doi:10.3390/ijerph18084182.

- Mackert M, Table B, Yang J, et al. Applying best practices from health communication to support a university’s response to COVID-19. Health Commun. 2020;35(14):1750–1753. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1839204.

- Lincango-Naranjo E, Espinoza-Suarez N, Solis-Pazmino P, et al. Paradigms about the COVID-19 pandemic: knowledge, attitudes and practices from medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):128. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02559-1.

- Enria L, Waterlow N, Rogers NT, et al. Trust and transparency in times of crisis: Results from an online survey during the first wave (April 2020) of the COVID-19 epidemic in the UK. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0239247. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239247.

- Pandit N, Monda S, Campbell K. Anticipatory worry and returning to campus during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Health. 2022:1–7. doi:10.1080/07448481.2022.2057803.

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1. doi:10.2307/2137284.

- Factsheets and Data Tables | University Analytics and Institutional Research | UMass Amherst. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.umass.edu/uair/data/factsheets-data-tables

- About – Quick Facts | University of Massachusetts. UMass System. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.massachusetts.edu/about/quick-facts

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208.

- Revised Academic Calendar for Fall 2020 | UMass Amherst Spring 2022. UMass Amherst Spring 2022: UMass Amherst. Accessed February 18, 2022. https://www.umass.edu/coronavirus/news/revised-academic-calendar-fall-2020

- Nelson J. Using conceptual depth criteria: addressing the challenge of reaching saturation in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2017;17(5):554–570. doi:10.1177/1468794116679873.

- Weller SC, Vickers B, Bernard HR, et al. Open-ended interview questions and saturation. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198606. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198606.

- Nascimento LdC, Souza T d, Oliveira IdS, Moraes J d, Aguiar R d, Silva L d Theoretical saturation in qualitative research: an experience report in interview with schoolchildren. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71(1):228–233. doi:10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0616.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Mowbray F, Woodland L, Smith LE, Amlôt R, Rubin GJ. Is my cough a cold or covid? A qualitative study of COVID-19 symptom recognition and attitudes toward testing in the UK. Front Public Health. 2021;9:716421. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.716421.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Crabtree B, Miller W. Doing Qualitative Research (Research Methods for Primary Care). 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA & London, UK: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1999.

- Frontiers | Considerations for Meeting Students’ Mental Health Needs at a U.S. University During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study | Public Health. Accessed February 18, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.815031/full

- Self-reported COVID-19 infection and implications for mental health and food insecurity among American college students | PNAS. Accessed February 18, 2022. https://www.pnas.org/content/119/7/e2111787119

- Cassidy C, Bishop A, Steenbeek A, Langille D, Martin-Misener R, Curran J. Barriers and enablers to sexual health service use among university students: a qualitative descriptive study using the theoretical domains framework and COM-B model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):581. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3379-0.

- Wombacher K, Dai M, Matig JJ, Harrington NG. Using the integrative model of behavioral prediction to understand college students’ STI testing beliefs, intentions, and behaviors. J Am Coll Health. 2018;66(7):674–682. doi:10.1080/07448481.2018.1454928.