ABSTRACT

The establishment of Saorstát Éireann (the Irish Free State) in 1922 did not herald a fundamental overhaul of the administrative machinery inherited from Whitehall and Dublin Castle. Path dependent continuities in legislation and executive orders underpinned the new dispensation. At the same time, a process of evolutionary change, which we call ‘administrative greening’, was underway. Drawing on data in the Irish State Administration Database (ISAD), and building on our analysis in Biggins, J., MacCarthaigh, M., & Scott, C. (2024). Priming the state: Continuity and junctures in the foundation of the Irish administration. Irish Political Studies, we explore these dynamics of both continuity and change in the formative years of the new state’s public administration. In so doing, we attest to patterns of normative production and reproduction, illustrated with reference to a number of legislative and administrative examples.

Introduction

We have written elsewhere about the influences of ‘historical institutionalism’, ‘path dependence’ and ‘critical junctures’ in the emergence of the Irish public administration (Biggins et al., Citation2024). There we identified complex paths of both continuity and change across key political and legal moments in a phased ‘critical juncture’, spanning the 1919 revolutionary Dáil Éireann regime; the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, known as the Anglo-Irish Treaty 1921 (hereafter ‘the Treaty’); and the 1922 constitutional settlement. Here we explore the legislative and administrative ripple effects of these antecedent normative events through the lens of path dependence, whereby:

[I]nstitutional configurations often inhibit actors’ attempts to transform structures in response to environmental pressures. Because prevailing institutions set the limits for individual action, research on path dependency suggests, they determine what subsequent changes are possible. While institutions are dynamic, then, their evolution does not necessarily mirror actors’ preferences. (Cortell & Peterson, Citation1999, p. 180)

Drawing on data from the Irish State Administration Database (ISAD, www.isad.ie, Hardiman et al., Citation2021) we show how the nature and pace of greening diverged across policy sectors and at different moments in time. The sometimes-overlooked role of law, in the form of constitutional and legislative dynamics, in both perpetuating and reassembling administrative norms is an important plank in our analysis. Legislative and administrative greening varied in tempo across sectors. This was contingent, we suggest, on the degree to which pre-independence legislation and administrative bodies already populated a policy space. A multifarious greening process is evident in the range of political responses to the inherited administration and some policy areas underwent ‘bounded change’ (Pierson, Citation2000, p. 265).

In some spheres, pre-existing legislation and administrative bodies survived without undergoing immediate significant change. Other sectors saw bridging legislation and the establishment of transitional or specific-purpose administrative bodies, some very short-lived. These were either replaced by new bodies performing equivalent functions or were absorbed into government departments. Others were departmentally absorbed without having undergone transition. Meanwhile, a number of new legislative programmes and administrative bodies emerged into relatively uncrowded (or ‘greened’) policy space, in pursuit of fledgling economic and social policy priorities.

Our period of reference is the early years of the state spanning from 1922 to before the adoption of Bunreacht na hÉireann (Constitution of Ireland) in 1937. This includes part of a timescale we have previously branded the ‘Emergence’ period (MacCarthaigh, Biggins, & Hardiman, Citation2023, p. 103−104). The focus here is on administrative dynamics and their political dimensions.

Constitutional continuities

As highlighted by us elsewhere, trends of legislative and administrative continuity, as well as the seeds of change, were apparent during the ‘Provisional Government’ period ahead of the entry into force of the Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann) on 6 December 1922 (Biggins et al., Citation2024, p. XXX). Throughout 1922, the Provisional Government, and its Ministers, issued executive notices and decrees which, in some respects, were new policy departures and, in other respects, very much promoted the administrative status quo.

For instance, by the end of October 1922 the Provisional Government had shuttered the parallel courts system (Casey, Citation1970, p. 340), known as the ‘Dáil Courts’, thereby removing a significant challenge to the established (‘Crown’) courts inherited by the Provisional Government from the British. Elsewhere, though, indigenous greening objectives were pursued with vigour. On 1 February 1922, the Minister for Education issued regulations requiring that the Irish language be taught, or used as a medium for teaching, for at least one hour each day in national (primary) schools (Iris Oifigiúil, Citation10 March, Citation1922).

The subsequent Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann) Act, 1922 (hereafter ‘the 1922 Constitution’) was a significant vector of normative continuity with the pre-1922 British administrative regime. However, it also teased the possibility of future change. Article 73 of the 1922 Constitution specified:

Subject to this Constitution and to the extent to which they are not inconsistent therewith, the laws in force in the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) at the date of the coming into operation of this Constitution shall continue to be of full force and effect until the same or any of them shall have been repealed or amended by enactment of the Oireachtas.

The need for that Article is rather obvious. If, on the passing of the Constitution the existing laws were to lapse we would find ourselves in rather a bad way … pending the setting up of the first Parliament of the Saorstát. (Houses of the Oireachtas, Dáil Éireann debate, Tuesday, 10 October 1922, vo1. 1, no. 20)

… I think we may well, for our own edification read the words ‘laws in force’ as the laws we have seen in force, not merely the British laws but the Irish laws … (Thomas Johnson, Houses of the Oireachtas, Dáil Éireann debate, Tuesday, 10 October 1922, vol. 1, no. 20)

As matters would transpire, it proved challenging to discern the true nature and extent of Dáil law-making prior to the Treaty and the 1922 Constitution. Mohr (Citation2020) highlights that a number of efforts were made in the 1920s and 1930s to catalogue and publish an authoritative list of Dáil decrees, ultimately to no avail (pp. 15–16). This blunted the potential influence of pre-December 1922 Irish (Dáil) decrees on the legal regime of the emergent state (Mohr, Citation2023, p. 21). Later on, ambiguities also surfaced as to whether prior British ‘imperial legislation’, superior to the domestic laws of the British dominions, had been carried into the Irish legal order (Mohr, Citation2008, pp. 33–34).

Normative continuity via the 1922 Constitution was reinforced by a preservation of the pre-existing official (i.e. ‘Crown’, not ‘Dáil’) courts system until new courts had been established (Article 75). During parliamentary debates on the draft constitution, George Gavan Duffy, a member of the Treaty delegation, protested that ‘something should go in there to put [the Dáil Courts] on the same footing as this Article puts the English law courts on’. The Minister for Home Affairs bluntly confirmed the ‘obvious’ reason for not doing so. It would be unacceptable to the British authorities, who had never recognised the pre-independence Dáil and its courts system, having maintained that position through the Treaty and constitutional negotiations (Houses of the Oireachtas, Dáil Éireann debate, 10 October 1922, vol. 1, no. 20).

Meanwhile, Article 74 of the 1922 Constitution clarified that taxes and duties remained payable for the current financial year and ‘any preceding year’. The Minister for Local Government, Ernest Blythe, rationalised this provision under the rubrics of both stability and future incremental change. He emphasised that it would ‘not bind us to continue these arrangements’ but would also ensure the new state’s finances were not ‘knock[ed] to bits’ before ‘alternative arrangements’ were made (Houses of the Oireachtas, Dáil Éireann debate, 10 October 1922, vol. 1, no. 20). Another consequential transitory provision for the public administration was Article 77, which ensured that any existing officer of the Provisional Government (except those on loan from the British) became an officer of Saorstát Éireann, while Article 78 confirmed that any officer who had been transferred by the British Government continued to benefit from the protections of the Treaty. Furthermore, Article 80 asserted an unbroken lineage between British and Saorstát Éireann government departments with respect to departmental property, assets, rights and liabilities.

Legislative greening

The system for drafting legislation in the new state was, on the advice of the British, modelled along British lines. A notable feature of this system was the referral of proposed legislation to the Ministry/Department of Finance (known as ‘treasury control’) for consent before submission to the cabinet for approval. Despite these strictures, it has been estimated that some 324 statutes were enacted between 1922 and 1929, which included a large volume of foundational legislation – a significant feat given a very limited number of parliamentary drafting personnel (Mohr, Citation2023, pp. 32–34).

After the coming into force of the 1922 Constitution on 6 December 1922, the first legislative priority of the Oireachtas (Parliament) was the Adaptation of Enactments Act, 1922 (‘the Adaptation Act’).Footnote1 The Adaptation Act was necessitated by the inheritance of a substantial legislative and public administrative apparatus, coupled with the creation of new offices under the 1922 Constitution. It was, therefore, vital to ensure that statutory, executive and contractual references were reoriented from British authorities to those of Saorstát Éireann. Otherwise, there was a significant legal and financial risk that powers exercised in the name of Saorstát Éireann, or its access to funds, would be ineffective or otherwise challenged. When introducing the Adaptation Bill to the Dáil (now the lower house of parliament) on 13 December 1922, the President of the Executive Council (‘the President’)Footnote2 characterised it as an ‘emergency’ measure of ‘real and special urgency’ aimed at ensuring ‘no breach of continuity’. He starkly explained:

If a Bill of this character were not introduced we should have no means of operating upon the Exchequer for the purpose of drawing money to pay wages and salaries from day to day, for paying old age pensions, or, indeed, for paying any of the charges incidental to the work of the Government.

The Adaptation Act gave a special place to provisions relating to public finances, with section 1 providing that all statutory references to the UK Consolidated Fund should in future be interpreted as references to ‘The Central Fund of Saorstát Eireann’, enabling the new state to store and to spend tax and other state revenues. Out of necessity, the Adaptation Act provided for maximal continuity to facilitate the collection and holdings of public monies, as well as their disbursement and audit, within the arrangements of the new state. The Adaptation Act also contained an important provisionFootnote4 enabling the government to establish boards of commissioners to perform functions previously exercised by administrative bodies in Ireland. This administrative bridging mechanism buttressed both an orderly transition and incremental greening in certain policy areas (per below). In one sense, the adaptation legislation operated to preserve the bulk of the legal-administrative status quo. But, in another sense, it commenced a gradual process of legislative and administrative evolution over the coming years.

Not long after the Adaptation Act, on 21 December 1922 the Expiring Laws Continuance Act, 1922 was enacted by the Oireachtas.Footnote5 This had the effect of temporarily continuing a number of pre-existing British statutes then verging on expiry, or having already expired, under their own terms. The subject-matter of these conserved statutes was quite broad, traversing areas such as employment, commercial matters, alcohol licensing, transport, housing, immigration and protection of animal species. Introducing this legislation, the Minister for Home Affairs assured the Dáil that there was ‘nothing controversial’ within the British legislation being continued. His contributions were imbued with themes of stability and continuity, particularly his comment that:

their disappearance would cause dislocation and in some cases actual hardship, and there seems no alternative but to come to the Dáil and invite members to rush to the rescue of these 26 expiring statutes. (Houses of the Oireachtas, Dáil Éireann debate, 18 December 1922, vol. 2, no. 8)

Parliamentary controversy was occasioned in 1924 when the government proposed that some of these British-origin statutes, rather than being renewed annually, should be permanently placed on the Irish statute book. One parliamentary contribution urged the government to itself design new legislation in specific areas and not ‘smuggle through’ prior statutes in this manner. The initial response of the Minister for Finance, Ernest Blythe, who was moving the legislation on that occasion, was revealing, in that he could see nothing ‘wrong in making permanent Acts of this nature, some of which have been enforced since 1864, 1865 and so on’ (Houses of the Oireachtas, Dáil Éireann debate, 18 November 1924, vol. 9, no. 12). These exchanges perhaps underscore that, even where institutions and norms have been locked in, ‘stability – far from being automatic – may have to be sustained politically’ (Thelen, Citation1999, p. 396).

Ultimately, under parliamentary pressure, the government resiled from making existing statutes relating to motor cars and wireless telegraphy regulation permanent. This then placed a stronger onus on the government to initiate fresh legislation which, in the case of wireless telegraphy, emerged within two years.Footnote6 As new Irish legislation incrementally greened policy spaces formerly occupied by British statutes, the volume of these annual renewals diminished in subsequent decades. Nonetheless, by the mid-1930s there was still a material amount of British legislation being rolled over.Footnote7 And the full extent of inherited legislation did not perhaps become apparent until revisions of the statute book were undertaken in later decades.Footnote8 In fact, elements of this legacy legislation, though formally carried over in 1922, were already obsolete at the foundation of the state. For example, Osborough identifies a provision of judicial legislation which, although carried onto the Saorstát Éireann statute book, would have been impossible to apply in practice, due to certain institutional reforms introduced at the end of the nineteenth century (Citation1995, p. P).

The first two years of the state witnessed a number of legislative measures embodying both continuity and evolution in court structures.Footnote9 The hands of the government had been somewhat tied by the constitutional commitment to the British (Crown) courts system pending the foundation of new courts. However, with a number of Crown judicial personnel discharged by the Provisional Government and the Dáil Courts shuttered (Kotsonouris, Citation1994, p. 109), a transitional measure for the holding of ‘District Courts’ was enacted in 1923.Footnote10 A final break with the Dáil Courts came in the same year when legislation was passed to wind them up.Footnote11 The subsequent Courts of Justice Acts were undoubtedly crucial pieces of legislation revamping the Irish courts system.Footnote12 Importantly, however, the common law norms underpinning the state and its public administration, grounded in a pre-independence British heritage, went undisturbed by this initiative.

As Hardiman and Scott (Citation2010) illustrate, state-building got underway through the 1920s and 1930s, particularly along regulatory, moral and developmental lines. In part, this was to fill gaps left after the transfer of administrative functions in 1922,Footnote13 not least in the areas of policing and security. A new force, initially known as the ‘Civic Guards’ and later An Garda Síochána (‘Guardians of the Peace’), was established. Its founding legislation repealed and replaced a swathe of prior policing statutes.Footnote14 Aside from immediate security priorities in the shadow of civil war, moral regulation was also a concern for the new state. Legislation relating to the censorship of filmsFootnote15 was enacted within the first year of the state’s foundation, with censorship of publications legislation following later in 1929.Footnote16 Gambling activities also attracted legislative intervention in the early years of the state.Footnote17 Hardiman and Scott (Citation2010) highlight that, while such initiatives were motivated by Catholic moral values:

these values were in fact widely subscribed to … The Catholic Church did not need to exercise influence to have legislation congruent with its preferences enacted … there was virtually no organized alternative body of opinion to resist these values. (pp. 184–185)

In aggregate, this state-building activity drove legislative (and administrative) greening in a broad range of areas. However, the pace and complexion of path dependence and greening varied across policy zones. In some realms, such as agriculture, new technical legislation colonised virgin policy space, not obviously or explicitly addressed in detail by preserved British statutes.Footnote30 These could be conceived as new policy paths, or ‘branchings’ (Pierson, Citation2000, p. 252). Elsewhere, Irish legislative initiatives had to negotiate pre-existing British statutes, including by partially or fully repealing them. These complexities were particularly noticeable, for instance, in post-1922 legislation governing land purchases by tenant farmers and smallholders, given that such schemes traced their origins to British statutes prior to the foundation of the state.Footnote31

In other realms, new legislation both disapplied aspects of previous British legislation and also explicitly adapted useful powers or definitions found there. By way of illustration, the Fisheries Act, 1924 substituted new penalties for fishing offences in place of those found in pre-existing statutes.Footnote32 But it simultaneously assigned certain powers to the police and enforcement officers also derived from pre-existing legislation. This legislative rebalancing perhaps epitomises ‘institutional layering’ where ‘an institution is changed incrementally as additional rules or structures are added on top of what already exists’ (Boas, Citation2007, p. 47). Alternatively, it could be perceived from the standpoint of ‘bricolage’, which entails ‘the rearrangement of elements that are already at hand, but it may also entail the blending in of new elements that have diffused from elsewhere’ (Carstensen, Citation2011, p. 154).

Administrative greening

Winston Churchill and Michael Collins had agreed in April 1922 that some administrative functions would be temporarily ‘reserved’ by the British for practical, strategic and financial reasons. Indeed, many of these had originally been scheduled for reservation under the Government of Ireland Act, 1920,Footnote33 which was later superseded in Saorstát Éireann by the 1922 Constitution. The reserved bodies included the Land Commission, Registry of Deeds, Commissioners of Irish Lights and the Post Office Savings Bank (McColgan, Citation1983, pp. 100–104). Article 79 of the 1922 Constitution clarified that the transfer of these functions was deferred to 31 March 1923 at the latest. While these administrative aberrations were mostly resolved by April 1923, residues of British authority lingered at the edges. Due to an administrative quirk, the Office of Arms (the genealogical and heraldic authority) was not formally transferred until 1943 (Hood, Citation2002).

The bulk of existing civil and public servants from Dublin Castle had been transferred to the Provisional Government and, ultimately, to Saorstát Éireann. They were joined by London recruits (some on loan) including, notably, from the UK Treasury, who played a key role in institutionalising Whitehall norms in the Irish administration (Mohr, Citation2023, pp. 32–33). A relatively small number of personnel from the prior revolutionary Dáil administration and others who had been dismissed by the British for disloyalty in 1916 also transferred (Maguire, Citation2008, p. 135; Coakley & Gallagher, Citation2018, p. 19). In addition, the Treaty had facilitated settlements for officers ‘discharged’ by the Provisional Government, those who retired by virtue of the change in government and those who sought a different assignment, e.g. to Northern Ireland.Footnote34 While a number of senior officers were discharged (particularly in the legal and judicial spheres) or opted to retire, 99 per cent of the civil service in 1922 comprised personnel who had been recruited under the old regime (Coakley & Gallagher, Citation2018, p. 20). Accordingly, the mix of personnel of the new civil and public service heavily, though not entirely, mirrored the old.

When viewed from a normative standpoint, Chubb (Citation1992, p. 219) notes that senior civil service advisers:

steeped in the British tradition, saw no need for changes in administrative structures or practices. They looked for and got much friendly cooperation and avuncular advice from the Treasury, the very centre of British bureaucratic traditions.

That said, the 1924 Act did strengthen the government’s executive authority to dissolve certain boards of commissioners and other statutory bodies, transfer their powers and duties etc. to ministers of the government and to wind up their affairs.Footnote36 This was a subtle but important device for administrative greening. The new state was here asserting a sovereign right to dispense with administrative bodies which had either been held over from before the foundation of the state, or had been succeeded by temporary bodies established under the Adaptation Act. These administrative dissolution and transfer powers under the 1924 Act were activated on a number of occasions throughout the 1920s and 1930s and were mechanisms of administrative greening. This trend perhaps speaks to Greener’s (Citation2005) point that, during a period of reproduction of a prior institution or policy:

it seems unlikely that anything greater than preservation of the status quo is possible - a situation more in line with constant than increasing returns … there is a cost involved in keeping things the same. (p. 69)

there were, during the British administration, quite a multiplicity of Boards and Statutory bodies, and during the last two years it has not been possible to survey the whole field and to see how better we may construct the Government machine. (Houses of the Oireachtas, Dáil Éireann debate, 16 November 1923, vol. 5, no. 13)

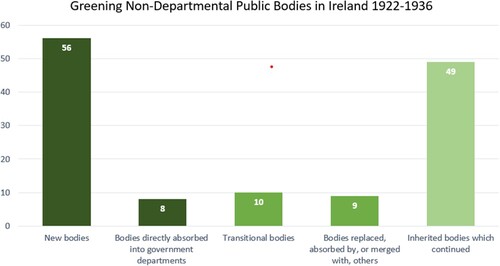

Between the transfer of functions in 1922 and the mid-1930s, similar to the legislative trends considered above, the pace of administrative greening varied across sectors and policy areas. The majority of administrative bodies initially transferred to Saorstát Éireann without legal incident. Indeed, many remained intact in their pre-independence forms (). Examples include the Commissioners of Charitable Donations and Bequests for Ireland, the Geological Survey and the Public Record Office which continue on in 2024, with or without modification of their form. This category also included a significant range of cultural and educational institutions, such as the National Library of Ireland and the main universities. While their lines of political accountability were refurbished in 1922, the essential nature and mandates of these bodies did not markedly shift in the early decades of the state. Some, such as the College of Science and the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction (founded 1900), were absorbed by government departments or other entities through the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote37

A few continued bodies were, at first, resistant to administrative greening for reasons to do with their specific legal forms and/or geographical scope of activity prior to the creation of Saorstát Éireann. ‘Royal chartered bodies’ posed peculiar legal challenges for the new state, as their founding documents (royal charters) were temporally anchored in discontinued royal prerogative powers and relied on the authority of defunct officers of the British administration in Ireland. Some also had an all-island dimension. This necessitated a tailored legislative intervention in the form of the Adaptation of Charters Act, 1926.Footnote38 As elaborated by one of us elsewhere (Biggins, Citation2023), this legislation enabled the government to transition royal chartered bodies to the sovereign and legal ‘time zone’ of the new state. For the most part, though, inherited administrative bodies were not subject to radical restructuring or legislative reform, instead undergoing an incremental process of greening, including through staff attrition and gradual reconciliation to the new political dispensation. This group of bodies continued to form the spine of Irish public administration for decades to come.

The Comptroller and Auditor General was a slightly different case. Amongst the most critical longstanding UK agencies operating in 1922, it had been established through the merger of two mediaeval offices under the terms of the Exchequer and Audit Department Acts, 1866.Footnote39 The new combined office was responsible both for authorising and auditing public expenditure. The 1922 Constitution provided for the appointment of a Comptroller and Auditor General (Article 62), with constitutional protections for the office holder. This prioritisation of finance had been foreshadowed in the extensive arrangements made for collecting and disbursing public funds by the 1919 (First) Dáil. However, the constitutional provision establishing the Comptroller and Auditor General was insufficiently detailed to provide a firm basis for action.

So the first agency established under legislation in the new state was the Department (subsequently Office) of the Comptroller and Auditor General, under the terms of the Comptroller and Auditor General Act, 1923 (Scott & MacCarthaigh, Citation2023).Footnote40 The Act provides for the appointment, tenure, salary and pension of the Comptroller and Auditor General and the appointment of staff. It also carries forward duties to control all disbursements and to audit all accounts of moneys administered by or under the authority of the Oireachtas. Interestingly, from a normative standpoint, much of the relevant law was to be the UK Exchequer and Audit Department Acts, 1866 and 1921. These arrangements remained substantially in place for more than seventy years. As such, the constitutional provision and legislation provided for utmost continuity in overseeing the public finances. Whilst path dependency may partly explain the inertia, the new government and its legal team could also be credited with the realisation that unless they prioritised confidence and security in the public finances they would stand little chance of achieving other goals for the new state.

A further category of bodies presented transitional challenges in terms of geographical scope. Examples include the National Education Board for Ireland,Footnote41 the General Nursing Council for IrelandFootnote42 and the Commissioners of Inland Revenue.Footnote43 These bodies’ original regulatory mandates were oriented to Ireland or the United Kingdom as a whole, territorial frames which had shifted upon the foundation of Saorstát Éireann and the partition of Ireland. In these situations, the government issued executive orders under the Adaptation Act (1922), establishing replacement bodies to perform equivalent functions in Saorstát Éireann. Once established, the survival rate and remits of these bodies varied considerably. A few, such as the Revenue Commissioners, enjoyed a broad mandate and thrived long afterwards.

A very small number of other bodies stemmed from commitments directly or indirectly relating to the Treaty settlement, particularly the Boundary Commission and the Dáil Éireann Courts Winding-Up Commission. Others were merely paper entities or transitional legal devices, such as the Saorstát Éireann Forestry Commissioners (1927), which seemingly existed for one day before being folded into the Department of Lands and Agriculture.Footnote44 Others again were conferred with very specific or isolated mandates extracted from pre-1922 legislation. This was evident in the case of the Light Railway Commission, set up in 1923 to perform an advisory function to the Minister for Industry and Commerce with respect to trams, exercising a power located in British legislation of 1920.Footnote45

Another key example was in the sphere of railway regulation. It was noted in the Oireachtas on 14 February 1923 (Houses of the Oireachtas, Seanad Éireann debate, 14 February 1923, vol. 1, no. 11) that the UK Railway and Canal Commission had ceased to have authority in the new state. Given the measures contained within the Adaptation Act, it is not clear why this was thought to be the case. We may surmise that the continuation of norms set by the Westminster Parliament in London was one thing, but any ongoing direct regulatory authority exercised by a body outside the state was deemed unacceptable. The matter was urgent because the UK Commission had been the approvals body for certain land transactions.Footnote46 The minister, Blythe, noted:

it is proposed to set up a Commission for the purpose of this particular business, to be called the Railway and Canal Commission (Extension of Time) Order, 1923. The Commission will consist of the Secretary of the Department of Local Government and the Secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs. They will do the work in this regard that has been done heretofore by the Railway and Canal Commissioners. I think the Order is a rather formal one. It is simply to set up a stop-gap body to do certain work which was done by the Commission, which has ceased to operate in Saorstát Eireann, until such time as permanent provision is made. (Houses of the Oireachtas, Seanad Éireann debate, 14 February 1923, vol. 1, no. 11)

It is also notable that, in establishing replacement or transitional bodies, the government was often inclined to reduce the number of decision-makers below that which applied at the equivalent pre-independence body. This might be partly explained by their reduced mandates and/or geographical (i.e. twenty-six county) scope, though it is perhaps also possible that straitened fiscal conditions in the 1920s influenced the approach. In any event, the establishment of replacement and transitional bodies was another manifestation of ‘institutional layering’ (Boas, Citation2007, p. 47). In these cases, underlying legislative frameworks already existed but it was necessary to constitute (new) Irish bodies to exercise the statutory functions. This strategy might also amount to pragmatic ‘bricolage’ (Carstensen, Citation2011) or simply ‘muddling through’ (Lindblom, Citation1959).

Meanwhile, a select number of policy areas initially experienced administrative inertia, followed by an absorption into Saorstát Éireann government departments or a replacement by new bodies established later. An intermediate transitional body was not instituted in these cases, thus it can be deduced that administrative greening, even if delayed, was rendered complete upon departmental absorption or replacement. Examples include the Electricity Commissioners (1924)Footnote48 and the General Prisons Board for Ireland (1928).Footnote49

Finally, and strikingly, a substantial number of new administrative bodies emerged into already-green policy space, particularly in the late 1920s and 1930s. Similar to our findings in relation to legislative greening, the trend is especially noticeable in the realms of natural resources, domestic infrastructure, industry and agriculture. This administrative pattern is also congruent with government economic policy during the 1920s, which promoted export-led agriculture heavily oriented to the British market (Daly, Citation1992, p. 17). Officialdom in the 1920s saw this as a comparative advantage, though it gave way in the early 1930s following the onset of the Great Depression, a change of government and a more protectionist economic orientation (Ó Gráda & O’Rourke, Citation2022, p. 345). In most cases, these new public bodies and their founding legislation were not substantially entangled with pre-existing administrative and legislative frameworks, potentially representing new institutional paths or branchings. Examples include the Dairy Produce Consultative Council (1925), the Live Stock Consultative Council (1925), the Agricultural Credit Corporation (1927), the Electricity Supply Board (1927), the Mining Board (1931) and the Turf Development Board (1934).

Figure 1. Greening non-departmental bodies in Ireland 1922–1936.

Source: Irish State Administration Database (www.isad.ie).

Conclusions

Following on from Biggins et al. (Citation2024), we have explored here the mechanisms of structural and normative reproduction, as well as evolution or what we term ‘greening’ in the fledgling Irish administration. In mapping complex processes of greening, we have exemplified how ‘bounded change’ (Pierson, Citation2000, p. 265) was realised in different arenas, contingent on the degree to which pre-independence legislation and administrative bodies already populated a policy space. The administrative structures and behaviours that survived through the independence period reflected closely the Whitehall administrative style, and remained characteristic of it for the following half-century, often including mimetic adoption of modernisation reforms.

This greening of legislation and the administration was not, in all sectors, a systematically planned affair. Much activity was reactive and transitional. Still, there was a political consciousness, evident in parliamentary debates, of not being seen to entirely replicate British structures and norms indefinitely. While grappling with existing institutions, the state also managed to enact a swathe of legislation and establish a considerable number of new administrative bodies to perform a broad range of functions in the economy and society. This early statement of policy intent cannot be overlooked, and it was on this foundation that the Irish administrative state began its development over the next century.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

John Biggins

John Biggins is a practising Barrister, Research Assistant at UCD College of Social Sciences and Law and Lecturer at Maynooth University School of Law & Criminology. John's research traverses regulatory governance, public administration and legal history. John is particularly interested in the dynamics of legal transition in the early years of the Irish State.

Muiris MacCarthaigh

Muiris MacCarthaigh is Professor of Politics and Public Policy and Head of the Department of Politics and International Relations at Queen’s University Belfast. His research engages with a variety of debates within and between political science, public sector governance and public policy. His is particularly interested in the role played by administrative systems in translating political preferences into policy outcomes.

Colin Scott

Colin Scott was appointed Professor EU Regulation and Governance at UCD Sutherland School of Law in 2006 and currently serves as Registrar, Deputy President and Vice-President for Academic Affairs. His main research focus is on fragmentation and accountability in regulatory governance. He previously held academic appointments at the University of Warwick, the London School of Economics, the Australian National University and the College of Europe Bruges and has served as Dean of Law, Dean of Social Sciences and Vice President for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion at UCD. He is a member of the National Economic and Social Council and of the Irish Research Council.

Notes

1 No. 2 of 1922.

2 Equivalent to a Prime Minister.

3 Adaptation of Enactments Act 1931 (No. 34 of 1931).

4 Section 7 of the Adaptation of Enactments Act 1922 (No. 2 of 1922).

5 No. 5 of 1922.

6 Wireless Telegraphy Act 1926 (No. 45 of 1926).

7 E.g. see Expiring Laws Act 1936 (No. 49 of 1936).

8 E.g. Statute Law Revision (Pre-Union Irish Statutes) Act 1962 (No. 29 of 1962).

9 E.g. County Courts (Amendment) Act 1923 (No. 45 of 1923); Enforcement of Law (Occasional Powers) Act 1923 (No. 4 of 1923); Court Officers (Temporary Appointments) Act 1924 (No. 2 of 1924).

10 District Justices (Temporary Provisions) Act 1923 (No. 6 of 1923).

11 Dáil Eireann Courts (Winding-Up) Act 1923 (No. 36 of 1923).

12 Courts of Justice Acts 1924-1936.

13 Provisional Government (Transfer of Functions) Order 1922, Belfast Gazette (7 April 1922) p. 379 (the ‘Transfer Order’). Partially replicated in Iris Oifigiúil (4 April 1922), ‘Public Notice No. 6’, p. 167 (the ‘Transfer Order’).

14 See schedules to Garda Síochána (Temporary Provisions) Act 1923 (No. 37 of 1923) and Garda Síochána Act 1924 (No. 25 of 1924).

15 Censorship of Films Act 1923 (No. 23 of 1923).

16 Censorship of Publications Act 1929 (No. 21 of 1929).

17 E.g. Gaming Act 1923 (No. 50 of 1923); Betting Act 1926 (No. 38 of 1926); Betting Act 1931 (No. 27 of 1931).

18 E.g. Agricultural Credit Act 1927 (No. 24 of 1927); Agricultural Produce (Fresh Meat) Act 1931 (No. 10 of 1930); Milk and Dairies Act 1935 (No. 22 of 1935).

19 E.g. Arterial Drainage Act 1925 (No. 33 of 1925); Mines and Minerals Act 1931 (No. 54 of 1931).

20 E.g. Beet Sugar (Subsidy) Act 1925 (No. 37 of 1925); Control of Manufacturers Act 1932 (No. 21 of 1932).

21 E.g. Currency Act 1927 (No. 32 of 1927).

22 E.g. Shannon Electricity Act 1925 (No. 26 of 1925).

23 Housing Acts 1925-1934.

24 E.g. Fisheries Act 1925 (No. 32 of 1925); Sea Fisheries Act 1931 (No. 4 of 1931).

25 E.g. Wild Birds Protection Act 1930 (No. 16 of 1930); Oil in Navigable Waters Act 1926 (No. 5 of 1926).

26 E.g. Unemployment Assistance Act 1933 (No. 46 of 1933).

27 Widows and Orphans Pensions Act 1935 (No. 29 of 1935).

28 E.g. Public Charitable Hospitals (Temporary Provisions) Act 1930 (No. 12 of 1930); Public Hospitals Act 1933 (No. 18 of 1933).

29 Medical Practitioners Act 1927 (No. 25 of 1927).

30 E.g. Live Stock Breeding Act 1925 (No. 3 of 1925).

31 E.g. see second schedule to the Land Act 1923 (No. 42 of 1923).

32 Section 9 of the Fisheries Act 1924 (No. 6 of 1924).

33 Section 9, 10 & 11 Geo. 5., ch. 67.

34 Article 7 of the Transfer Order above n. 13.

35 No. 16 of 1924.

36 Sections 9 and 10 of the 1924 Act.

37 The College of Science was folded into University College Dublin in 1926, while the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction was divvied up between the Departments of Fisheries, Lands, Agriculture and Industry and Commerce under S.I. No. 5/1927, S.I. No. 101/1927 and the Agriculture Act 1931 (No. 8 of 1931).

38 No. 6 of 1926.

39 29 & 30 Vict., ch. 39.

40 No. 1 of 1923.

41 S.I. No. 10/1923

42 S.I. No. 8/1923.

43 S.I. No. 2/1923.

44 S.I. No. 68/1927; S.I. No. 69/1927.

45 S.I. No. 6/1923.

46 Under the Defence of the Realm (Acquisition of Land) Act 1916, 6 and 7 Geo 5, c. 63.

47 No. 29 of 1924.

48 S.I. No. 7/1924.

49 S.I. No. 79/1928.

References

- Biggins, J. (2023). Inheriting the royals: Royal chartered bodies in Ireland after 1922. UCD Geary Institute for Public Policy Working Paper (WP2023/03).

- Biggins, J., MacCarthaigh, M., & Scott, C. (2024). Priming the state: Continuity and junctures in the foundation of the Irish administration. Irish Political Studies.

- Boas, T. C. (2007). Conceptualizing continuity and change: The composite-standard model of path dependence. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 19(1), 33–54. doi:10.1177/0951629807071016

- Carstensen, M. B. (2011). Paradigm man vs. The bricoleur: Bricolage as an alternative vision of agency in ideational change. European Political Science Review, 3(1), 147–167. doi:10.1017/S1755773910000342

- Casey, J. (1970). Republican Courts in Ireland 1919-1922. Irish Jurist, 5(2), 321–342.

- Chubb, B. (1992). The government and politics of Ireland (3rd ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Coakley, J., & Gallagher, M. (2018). Politics in the republic of Ireland (6th ed.). Oxford and New York: Routledge.

- Collier, R. B., & Collier, D. (1991). Critical junctures and historical legacies. In Shaping the political arena: Critical junctures, the labor movement and regime dynamics in Latin America (pp. 27–39). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cortell, A. P., & Peterson, S. (1999). Altered states: Explaining domestic institutional change. British Journal of Political Science, 29(1), 177–203. doi:10.1017/S0007123499000083

- Daly, M. E. (1992). Industrial development and Irish national identity, 1922–1939. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

- Daly, M. E. (1997). The buffer state: The historical roots of the department of the environment. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration.

- Greener, I. (2005). The potential of path dependence in political studies. Politics, 25(1), 62–72. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9256.2005.00230.x

- Hardiman, N., MacCarthaigh, M., & Scott, C. (2021). The Irish state administration database. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://www.isad.ie.

- Hardiman, N., & Scott, C. (2010). Governance as polity: An institutional approach to the evolution of state functions in Ireland. Public Administration, 88(1), 170–189. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01794.x

- Hood, S. (2002). Royal roots, republican inheritance: The survival of the office of arms. Cork: Woodfield Press.

- Houses of the Oireachtas. Debates. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from https://www.oireachtas.ie/debates/.

- Iris Oifigiúil. (1922). Irish Provisional Government Public Notice No. 4. March.

- Kotsonouris, M. (1994). Retreat from revolution: The Dáil courts, 1920–24. Kildare: Irish Academic Press.

- Lindblom, C. E. (1959). The science of “muddling through”. Public Administration Review, 19(2), 79–88. doi:10.2307/973677

- MacCarthaigh, M., Biggins, J., & Hardiman, N. (2023). Public policy accumulation in Ireland: The changing profile of ministerial departments 1922–2022. Irish Political Studies, 38(1), 92–119. doi:10.1080/07907184.2023.2167350

- Maguire, M. (2008). The civil service and the revolution in Ireland, 1912–38. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

- McBride, L. W. (1991). The greening of Dublin castle: The transformation of bureaucratic and judicial personnel in Ireland 1892-1922. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press.

- McColgan, J. (1983). British policy and the Irish administration 1920-22. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Mohr, T. (2008). The colonial laws validity act and the Irish free state. Irish Jurist, 43, 21–44.

- Mohr, T. (2020). The strange fate of the Dáil decrees of revolutionary Ireland, 1919-22. Statute Law Review, 20(20), 1–18.

- Mohr, T. (2023). The ‘provisional period’ in Irish legal and political history, 1921–1922. UCD Working Papers in Law, Criminology and Socio-Legal Studies, Research Paper No. 11/2023.

- Ó Gráda, C., & O’Rourke, K. H. (2022). The Irish economy during the century after partition. Economic History Review, 75, 336–370. doi:10.1111/ehr.13106

- Osborough, W. N. (1995). The Irish statutes, revised edition: Edward II to the union. Dublin: The Round Hall Press.

- Peters, B. G., Pierre, J., & King, D. S. (2005). The politics of path dependency: Political conflict in historical institutionalism. The Journal of Politics, 67(4), 1275–1300. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00360.x

- Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence and the study of politics. The American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251–267. doi:10.2307/2586011

- Scott, C. (2021). The politics of regulation in Ireland. In D. in Farrell & N. Hardiman (Eds.), Oxford handbook of Irish politics (pp. 647–667). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scott, C., & MacCarthaigh, M. (2023). Ireland’s first state agency: A century of change in the range and scope of functions of the office of the comptroller and auditor-general. Administration, 71(4), 5–23. doi:10.2478/admin-2023-0023

- Thelen, K. (1999). Historical institutionalism in comparative politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 2, 369–404. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.369