ABSTRACT

Rapid increases in apartment construction have ignited concerns about design quality. Lower income populations could be disproportionately impacted by poor design as they are more likely to live in apartments and have fewer resources to mitigate design problems. We examined whether there was a socioeconomic gradient in contemporary apartment design by measuring the implementation of quantifiable policy-specific requirements in buildings (n = 172) sampled from relatively low, mid, and high socioeconomic neighbourhoods within Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth. Findings suggest the presence (or absence) of detailed policy instruments interacts with local market conditions to impact apartment design quality.

摘要

公寓建设的快速发展引发了人们对设计质量的担忧。低收入人群可能会出现问题。我们从悉尼、墨尔本和珀斯社会经济水平相对较低、中等和较高的社区抽取样本,通过测量建筑物(n = 172)中可量化特定政策要求的实施情况,研究了当代公寓设计中是否存在社会经济梯度。研究结果表明,详细政策手段的存在(或缺失)与当地市场条件相互作用,影响公寓设计质量。

1. Introduction

To sustainably accommodate growing urban populations, cities around the world have adopted compact city planning policies that encourage increased densification (Giles-Corti et al. Citation2022a). Globally, the construction of apartment developments has proliferated, although the proportion of apartments differs markedly by country (Seo Citation2016, Eurostat Citation2021, Shin et al. Citation2023). In Australia, new apartment housing is essential to transform traditionally low-density cities into more compact, liveable, sustainable communities. There has been a rapid expansion in apartment development over the past decade (Shoory Citation2016), with approvals for attached dwellings surpassing detached housing for the first time in 2015 (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2020a). In Sydney and Melbourne, apartments now account for 22% and 12% of all occupied housing, respectively (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2022a, Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2022b). While these rates are lower than other global cities (Eurostat Citation2021), the influx of apartments represents a fundamental change for a population more accustomed to detached suburban housing (Kelly et al. Citation2011). Indeed, the proliferation of new apartment buildings is not without controversy, with government agencies and academics voicing unease about the quality of new apartments, and potential impacts of poor design on residents (City of Melbourne Citation2013, Nethercote and Horne Citation2016, The State of Victoria Department of Environment Land Water & Planning Citation2021).

In response, several Australian state and local government planning departments introduced apartment design policies to raise the design quality of residential apartments (Foster et al. Citation2020). These mirror international efforts to use policy instruments to shape the development of sustainable, affordable, and healthy apartment housing (Department of Housing Planning and Local Government Citation2018, City of Vancouver Citation2020, Mayor of London Citation2020). In Australia, the policy response was led by New South Wales (NSW), where the state government established a comprehensive apartment design policy and accompanying design guide in 2002 to improve the quality of residential apartments. Since its legislation, it is generally acknowledged that State Environmental Planning Policy 65 (SEPP65) has raised apartment design quality in NSW (Mould Citation2011, Moore et al. Citation2015). This successful policy intervention has influenced other states, with Victoria (VIC) and Western Australia (WA) introducing similar wide-ranging apartment design policies in 2017 and 2019, respectively (Foster et al. Citation2020). All three policies are structured with series of overarching objectives that apartment buildings must achieve, combined with design requirements (or standards) and general guidance to help deliver the objectives.

If implemented as intended, minimum standards should help prevent poor design outcomes, particularly among more affordable buildings where profit margins are typically lower (Mould Citation2011). In Victoria, policymakers acknowledge that the absence of detailed apartment planning guidance “led to a proliferation of buildings with windowless, tiny bedrooms and unhealthy spaces” (The State of Victoria Department of Environment Land Water & Planning Citation2021, p. 4). Indeed, the President of the Victorian Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects highlighted that “minimum metric standards are really about weeding out the worst of the worst” (Cheng Citation2016). Yet within the development industry, opinions on minimum standards vary. What some regard as an essential mechanism to ensure more affordable apartments deliver appropriate quality and amenity, others condemn for reducing housing affordability or stifling design innovation (Mould Citation2011, Moore et al. Citation2015, Cheng Citation2016). However, in NSW the SEPP65 intervention is thought to have improved design quality – including at the bottom end of the market – with relatively minimal impacts on affordability (Clare and Clare Citation2014, Moore et al. Citation2015).

The notion that the design quality of apartments could be compromised in less desirable locations is consistent with studies on housing quality and socioeconomic disadvantage. There is considerable evidence within Australia and internationally of a socioeconomic gradient in housing, whereby lower income populations live in poorer quality housing (Howden-Chapman et al. Citation2012, World Health Organization Citation2018, Bentley and Baker Citation2022) and that housing quality is worse in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Kearns Citation2003). This could inequitably impact lower income populations who have less volition over the construction, design and locality of their housing (Howden-Chapman et al. Citation2012). For example, a large multi-city European study found those in the lowest income quintile were exposed to worse housing conditions, including both perceived housing problems (e.g. damp and mould, cold housing, overcrowding, noise exposure) and objectively measured exposures (e.g. inadequate waterproofing, water supply issues, single glazed windows) (Braubach et al. Citation2009). Australian research identifies similar patterns, with lower income populations exposed to more housing problems (Daniel et al. Citation2019). While the evidence largely focuses on housing condition and problems, which can be exacerbated by design flaws (World Health Organization Citation2018), few studies investigate socioeconomic disparities in the design of housing, distinguish between different housing typologies, or focus on apartments specifically.

The design quality of apartments is especially pertinent for lower income residents, as a higher proportion of low-income households live in apartments versus other housing types (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2016). These households can be disproportionally impacted by the challenges inherent to apartment living, including the closer physical proximity between neighbours, shared communal and circulation spaces, and the need to co-ordinate and co-operate with neighbours to manage building upkeep and maintenance (Easthope et al. Citation2017). According to Easthope et al. (Citation2017), key design issues that can impact low-income apartment residents include visual and acoustic privacy, sunlight access, natural ventilation, storage, provision of communal facilities (including amenities for children), and building security and accessibility (Easthope et al. Citation2017). While these design problems can impact the experience of all apartment residents, regardless of income (Kleeman et al. Citation2022), lower income groups can lack the resources to shield themselves from the negative impacts of poor design (e.g. increased costs of air-conditioning for heating or cooling) (Howden-Chapman et al. Citation2012). Indeed, lower income populations living in apartments are more susceptible to fuel poverty (Poruschi and Ambrey Citation2018). Furthermore, as demographic changes and housing unaffordability increase multigenerational and share house living, the spatial layout of contemporary apartments can negatively impact living conditions (Yang et al. Citation2022). Notably, most of the design issues raised by Easthope et al. (Citation2017) are addressed in the new generation of Australian state apartment design policies (Foster et al. Citation2020), and while these policies cannot impact apartments that predate their legislation (Easthope et al. Citation2017), they could ensure new apartments – built since the policies were enacted – are delivering the minimum requirements that target these design problems.

However, the apartment design policies in Australia are performance based (Foster et al. Citation2020), meaning the policy objectives can be delivered through design innovation rather than meeting the minimum requirements (Mould Citation2011). Building approval processes require the submission of a development application to the appropriate authority (e.g. local or state government department), where it is assessed against the relevant planning policies, land-use regulations, and public submissions (Shoory Citation2016). Depending on the jurisdiction and scale of the development, this phase often includes expert advice from a design review panel. Based on the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) in the UK, these panels of multi-disciplinary built environment professionals provide independent reviews of proponents’ submissions (Moore et al. Citation2015). Design review is key to bridging the quantitative standards that are included in design policies, with a more nuanced understanding of the building performance and site constraints (Moore et al. Citation2015). While design review is considered advice only, the panel recommendations must be given due regard by the administering authority (WA Planning Commission Citation2019) and developers, architects and local authorities generally value the expert review and advice provided (Moore et al. Citation2015). Nonetheless, the final constructed development or “as-built” building can sometimes differ from the “as-designed” building (Shergold and Weir Citation2018, Easthope et al. Citation2023). Numerous factors contribute to this, including: (1) the use of design-and-construct contracts where the builder assumes responsibility for the project and may change aspects of the design and construction to “find efficiencies” or improvise when the documentation is incomplete; (2) the privatised building certification system where surveyors have a commercial relationship with builders; (3) the erosion of capacity and expertise within local government building authorities; and (4) lack of regulatory oversight (Shergold and Weir Citation2018, Easthope et al. Citation2023). Recent reports reiterate the need for systemic change to ensure the constructed apartment buildings are faithful to the original approved design (Shergold and Weir Citation2018, Easthope et al. Citation2023)

Housing is widely acknowledged as a social determinant of health (World Health Organization Citation2018). There is compelling evidence that lower socioeconomic groups experience poorer health (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Citation2022), live in poorer quality housing (Daniel et al. Citation2019), and that poor housing quality and condition negatively influence mental and physical health outcomes (World Health Organization Citation2018). Similarly, substandard apartment design can produce homes with inadequate sunlight, natural ventilation, acoustic and visual privacy, thermal comfort and space, with implications for residents physical and mental health (Foster et al. Citation2020, Foster et al. Citation2022b). Given the propensity of lower income populations to live in apartments, any deficit in the uptake of minimum design requirements in buildings in disadvantaged neighbourhoods has the potential to further aggravate health inequalities.

This study tests whether there is a socioeconomic gradient in the design of contemporary Australian apartment buildings developed for the private housing market. Previous Australian research has established that more comprehensive design policy guidance was associated with the increased implementation of minimum requirements (Allouf et al. Citation2020, Foster et al. Citation2022a), however there has been no empirical evaluation of whether the design quality of contemporary apartments differs by neighbourhood disadvantage. We hypothesised that the presence of a more comprehensive apartment design policy at the time buildings were approved and built would protect apartments in relatively disadvantaged areas and minimise area-level differences in apartment design quality. We sampled buildings in three cities that were developed under different levels of policy guidance to compare the implementation of policy-derived design requirements between: (1) apartment buildings located in the lower socioeconomic neighbourhoods of Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth (i.e. between or inter-city differences); and (2) apartment buildings developed in relatively low, mid, and high socioeconomic neighbourhoods within each city (i.e. within or intra-city differences). In this study, the implementation of policy-derived requirements was used to represent the design quality of apartment buildings.

2. Methods

2.1. Building Selection

Developments (n = 113) were randomly selected from each city. To be eligible, buildings needed at least 40 apartments, three or more storeys, a construction date between 2006 and 2016, and that the endorsed architectural or development plans be available. The date range limited buildings in Sydney to those developed under SEPP65, whereas the buildings in Melbourne and Perth pre-dated the legislation of their respective state policies – the Better Apartment Design Standard (BADS) in Victoria (legislated 2017); and State Planning Policy 7.3 (SPP7.3) in Western Australia (legislated 2019). As SEPP65 applies to residential buildings with three or more storeys, the height criteria ensured the Sydney building sample matched the policy settings. BADS and SPP7.3 have no height limits, but the three-storey minimum was applied for consistency across the cities. The 40-apartment minimum was imposed because, as part of the broader study, residents were invited to complete a survey. This required buildings of sufficient scale so that the number of households approached to participate, together with the expected response rate, would achieve the desired sample size (Foster et al. Citation2019). The selection process also ensured buildings were located in neighbourhoods with different levels of disadvantage based on the ABS Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD) rankings (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2013). Using the IRSD decile rankings for Statistical Areas Level 1 (i.e. an area with an average population of about 400 people), buildings were stratified into low (deciles 8–10), mid (deciles 5–7) and high (deciles 1–4) neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage. The study is described elsewhere (Foster et al. Citation2019).

2.2. Measurement of the Implementation of Design Requirements

Quantifiable requirements relating to design objectives that could plausibly impact health and wellbeing were extracted from the apartment design policies and guidelines in NSW (i.e. SEPP65 and the Apartment Design Guide), Victoria (i.e. BADS) and WA (i.e. SPP7.3) (Foster et al. Citation2020). Requirements related to: (1) daylight and solar access; (2) natural ventilation; (3) acoustic privacy; (4) outlook and visual privacy; (5) indoor space; (6) private open space; (7) communal open space; (8) circulation spaces; (9) bicycle and car parking; and (10) apartment mix.

The method for measuring requirements and calculating policy implementation is described elsewhere (Hooper et al. Citation2022). Briefly, the plans and elevations for each building were assessed by architecturally qualified research assistants to extract source data. Methods included visual inspection of layouts, measuring dimensions from scaled pdfs, measuring building separation and setbacks in Nearmap (Nearmap Citation2021), and sun path modelling with Rhinoceros with a Ladybug plugin (Ladybug Tools Citation2021). Source data were extracted for all residential apartments (n = 10,553) and residential floors (n = 1094) within the buildings. These data were used to calculate policy implementation measures. In total, 96 policy-specific design requirements, derived from SEPP65, SPP7.3 and BADS, were created (Table S1).

A simple scoring system quantified the implementation of the policy requirements for each building (n = 172) from the 113 apartment complexes. Buildings were scored based on their implementation of all measured policy requirements, regardless of whether the requirement applied in the respective city’s design policy. Each requirement was assigned a score ranging from zero (i.e. indicating the requirement was not met) to one (i.e. indicating the requirement was met). For example, SEPP65 (NSW) and SPP7.3 (WA) stipulated that main bedrooms have a minimum area of 10m2, so if all (100%) apartments in the building met this standard, the building was allocated a point. Some policy thresholds were lower, and this was reflected in the scoring. For instance, both SEPP65 (NSW) and SPP7.3 (WA) stipulated that ≥70% of apartments in a building receive ≥2 h of direct sunlight between 9am and 3pm at mid-winter. Hours of solar exposure for all individual apartments was measured and if ≥70% of the apartments in a building met the standard, it was allocated a point. Partial points were allocated for requirements where the wording was more lenient, no threshold or standard was indicated, or optimal ranges were provided within the requirement. For example, requirements recommended different dwelling types be provided throughout the building, so buildings were allocated graded points depending on the number of apartment types in the building (i.e. 1 type = 0 points, 2 types = 0.5 points; 3 types = 0.75 points; 4 + types = 1 point).

Points were summed to create a building score for the ten design objectives and a total implementation score. Then, the level of implementation (for each objective and overall) was computed as the percentage of the maximum policy implementation score attainable for the measured design requirements. The total possible score for each building varied depending on the design of the apartment building. Accordingly, only apartments and buildings with multiple bedrooms, single aspects, cross-through apartments, courtyards, and “snorkel” bedrooms were assessed against the specific design requirements for those features. When computing scores, requirements were counted in multiple design objective scores but were only counted once in the total policy implementation score. Due to differences in design and scale, the buildings within each complex were scored separately. As communal open space and parking were usually shared by all buildings in a complex; the policy implementation scores for these requirements were assigned to all buildings in the development. The scoring system was intended as a simple quantification of design quality, where increased implementation of policy-derived requirements was used as a proxy for quality.

This study also examined a subset of individual apartment design measures that underpinned the policy implementation scores. Measures included: (1) number of bedrooms; (2) percentage of habitable rooms in the apartment with an external window; (3) hours of direct sunlight to the main apartment aspect; (4) courtyard area; (5) balcony area; (6) number of parking bays; (7) main bedroom area; (8) one-bedroom apartment area; (9) depth of open plan living area; (10) width of open living area; (11) proportion of apartments with a northerly aspect; and (12) proportion of apartments with a dual aspect. These variables were included because, while the development industry might meet the minimum requirements, area level differences could be apparent when exploring measures with more variability. For example, apartments in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods could meet the minimum space standards (e.g. 50m2 for a one-bedroom apartment in NSW), but on average, one-bedroom apartments in disadvantaged areas could still be smaller than those in more advantaged neighbourhoods.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Means and standard errors were calculated for all apartments/buildings within neighbourhoods of low, mid and high socioeconomic disadvantage in each city. Values were derived from multi-level models conducted in STATA that account for the hierarchical structure of the data (Stata Corporation Citation2016). The first set of models examined differences between the building-level policy implementation scores (i.e. total implementation and the ten design objective scores) by neighbourhood disadvantage using a three-level hierarchical structure (i.e. buildings nested in complexes nested in neighbourhoods). The second set of models examined a selection of apartment-level design measures (e.g. number of bedrooms, balcony area) and whether they differed by neighbourhood disadvantage using a four-level hierarchical data structure (i.e. apartments nested within buildings nested within complexes nested within neighbourhoods). Additional models with the full sample (i.e. Sydney, Melbourne and Perth) extended the second set of models by including city as a fixed effect. Mixed effects linear regression was used for continuous variables and logistic regression for dichotomous building measures.

3. Results

There was an even representation of buildings from low, mid and high disadvantage areas (). About a third of the buildings from more disadvantaged neighbourhoods were >15 km from the Central Business District (CBD), whereas over half of the buildings from low disadvantage neighbourhoods were located within 5 km of the city centre. More of the buildings were in Perth (40%), and this was reflected in the breakdown by neighbourhood disadvantage (i.e. a higher proportion of the buildings in low, mid and high disadvantage areas were from Perth). Buildings in more disadvantaged areas tended to be smaller (i.e. fewer apartments and floors per building) but had more buildings in the apartment complex.

Table 1. Overview of apartment building sample.

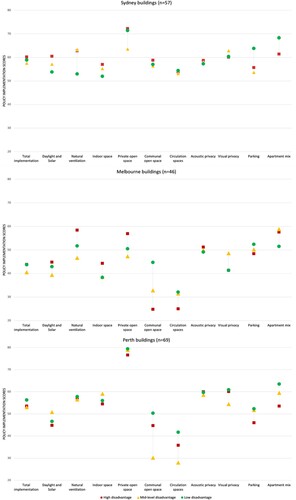

presents the mean policy implementation scores, stratified by city and neighbourhood disadvantage. Some differences were apparent when comparing the implementation scores between the cities. In Sydney, where the buildings were developed under a more comprehensive policy, total implementation for buildings in relatively disadvantaged neighbourhoods was higher than buildings in disadvantaged areas in Melbourne and Perth (i.e. Sydney: 60.2%; Melbourne 43.8%; Perth 53.5%). This pattern, whereby buildings in disadvantaged areas in Sydney scored relatively well, extended across most design objective sub-scores, except for private open space and acoustic privacy, where buildings in more disadvantaged areas in Perth scored higher than those in Sydney.

Figure 1. Building-level policy implementation scores for Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth by neighbourhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage.

When building scores were compared within each city, there was little evidence to suggest the implementation of minimum standards was worse in disadvantaged areas in Sydney and Melbourne. Indeed, the mean implementation scores for many of the design objectives were highest for buildings in disadvantaged areas in these cities (e.g. buildings in more disadvantaged areas in Sydney scored higher than buildings in mid and low disadvantage areas for total implementation, daylight and solar, indoor space, private open space, communal space and acoustic privacy). However, the pattern was different in Perth, where buildings in advantaged areas scored highest across all the design objectives except daylight and solar, indoor space, and acoustic privacy. While patterns differed, there were few significant differences in the implementation scores by area disadvantage. Compared to buildings in the most disadvantaged neighbourhoods, communal open space implementation was significantly poorer in buildings from mid-level disadvantage neighbourhoods in Perth (p < 0.05), and higher in buildings in the least disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Melbourne (albeit non-significant at p = 0.055) (see Table S2 for means and standard errors).

Additional analyses examined whether design quality was poorer in buildings in disadvantaged neighbourhoods by focusing on a subset of individual apartment design measures (e.g. courtyard area, hours of sunlight) (). Again, there was little evidence that the design quality of apartments was worse in more disadvantaged areas of Sydney and Melbourne. In Sydney, on average, apartments in disadvantaged neighbourhoods scored highest (or equal highest) on all bar one of the measures, and in Melbourne, apartments in disadvantaged areas scored highest on over half the measures tested. The pattern for Perth was different, with apartments in disadvantaged areas performing worst on most measures – on average, these apartments had smaller internal areas and private outdoor spaces, fewer parking spaces, and a lower proportion of apartments had a northerly or dual aspect.

Table 2. Apartment-level design measures for Sydney, Melbourne and Perth by neighbourhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage.

4. Discussion

This study investigated whether there was a socioeconomic gradient in the design of contemporary apartments in Australia by examining neighbourhood-level differences in: (1) the percentage of policy-derived minimum design requirements implemented in buildings; and (2) a selection of individual design attributes implemented in apartments. The findings were somewhat consistent across both approaches – apartments in more disadvantaged areas in Sydney and Melbourne typically met more minimum requirements and performed better on more individual design attributes than those in advantaged neighbourhoods in the same cities. However, the pattern was different in Perth, where apartments in advantaged areas performed better across most implementation scores and individual design attributes when compared with buildings in relatively disadvantaged areas. While there appears to be some socioeconomic patterning in apartment design within Perth (i.e. comparing buildings in low, mid and high disadvantage neighbourhoods in the same city), it is important to contextualise this against the differences in building scores between cities. Specifically, buildings in more disadvantaged areas in Sydney scored highest on total implementation (i.e. 60%), followed by buildings in disadvantaged areas in Perth (i.e. 54%), and those in disadvantaged areas in Melbourne rated lowest (i.e. 44%). To summarise, there was some socioeconomic patterning of “design” in Perth, but most implementation scores (whether they be in areas of low, mid or high disadvantage) exceeded those in Melbourne, where there was less evidence of within-city socioeconomic patterning.

The between-city differences for buildings in more socioeconomically disadvantaged areas – with Sydney scoring highest followed by Perth and then Melbourne – is consistent with a recent study that benchmarked the uptake of minimum design requirements in these cities (Foster et al. Citation2022a). In part, the observed differences can be attributed to the policies that were in operation when the buildings were developed. Buildings in each city were approved and built under different policy environments, with Sydney being the only city where the sampled buildings were developed under a comprehensive policy (i.e. SEPP65), whereas Perth and Melbourne buildings in our sample pre-dated detailed design legislation in both states (i.e. SPP7.3 and BADS). While Perth had some minimum standards governing solar access, privacy, and space under the previous policy (i.e. State Planning Policy 3.1, Residential Design) which likely accounts for the better performance against some design objectives, Melbourne had only limited discretionary guidance for buildings ≥5 storeys and few quantifiable requirements for those <5 storeys (Foster et al. Citation2020). The implementation scores support the notion that the legislation of detailed design policies with minimum standards had a protective impact on apartments in general (Foster et al. Citation2022a), and this extended to those in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

The maturity of the apartment market in each city could also contribute to the between-city differences. While all Australian cities have experienced a boom in apartment construction, the proportion of residents living in apartments in WA is much lower than in NSW and Victoria (i.e. WA 6%; NSW 22%; VIC 12%) (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2022a, Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2022b). Perth is a sprawling low-density city with a population that is more reticent about apartment living (Department of Housing Citation2013), and the apartment market has lagged Australia’s larger state capitals (Shoory Citation2016). To convince would-be buyers that apartments are an attractive alternative to lower density housing options, developers may have consciously developed apartments and buildings with superior amenity, whilst also drawing from the successful template provided by SEPP65 (Foster et al. Citation2022a). Indeed, prior to the introduction of SPP7.3 in WA, some local councils used SEPP65 when assessing development applications and as inspiration for local design policies (e.g. City of Vincent’s Built Form Policy) (Foster et al. Citation2022a).

While the dynamics of the Perth apartment market appeared to elevate the design quality of apartments above those in Melbourne, local market conditions may also contribute to the within-city differences. Perth was the only city with any apparent patterning of apartment design by area disadvantage, with buildings in more advantaged areas implementing more of the measured requirements. Developers had no obligation to adhere to most minimum design requirements measured in this study as buildings were developed under the previous, comparatively limited planning policy; yet its plausible they would intentionally deliver a better product in more advantaged neighbourhoods where apartments could sell at a higher price point than in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods where profit margins can be lower (Mould Citation2011). The higher design quality provided in more advantaged areas also aligned with the industry need to persuade homebuyers that apartments were an appealing housing alternative. While the socioeconomic gradient identified in Perth is concerning, the recent policy intervention (i.e. legislation of SPP7.3 in 2019) should minimise these observed inequalities by raising the (minimum) design quality of future apartments in more disadvantaged areas.

Like Perth, the buildings sampled in Melbourne were the product of a lax policy environment, however there was no within-city socioeconomic patterning, with buildings in more disadvantaged areas often scoring better than those in advantaged neighbourhoods. Again, this can be partly explained by the state of the Melbourne apartment market and demand for housing. Our study focused on buildings developed between 2006 and 2016, which coincided with a period of intense apartment construction and buyer interest (CAN Citation2015, Shoory Citation2016). Developers were attracted to Melbourne by land prices that were more affordable than Sydney and a “generous planning system” (CAN Citation2015), while the increased cost of detached houses in Melbourne made apartments a comparatively affordable alternative, driving both local and offshore demand (CAN Citation2015, Shoory Citation2016). This thriving apartment market had implications for the housing that was developed, as it negated the need to deliver a high level of amenity to ensure the apartments sold. Indeed, interviews with industry stakeholders in Melbourne and Sydney found that developers prioritised apartment amenity when the market was weak to help drive sales, whereas there was less emphasis on amenity when the market flourished (Easthope et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, both buyers and renters could be drawn to advantaged areas by the promise of greater neighbourhood liveability, including walkability, quality public open space, social infrastructure, and public transport (Giles-Corti et al. Citation2022b). Residents’ willingness to compromise on dwelling design to live in a neighbourhood with superior liveability (Department of Housing Citation2013) could also contribute to the quality of apartments as sales may be driven by neighbourhood, rather than apartment, amenity.

Our interpretation of the results has focused on the patterns in the composite implementation scores and rankings; however, it should be noted that there were few statistically significant differences. Key differences were between communal space implementation in Perth, with buildings in mid socioeconomic areas scoring worse than those in disadvantaged areas (p = 0.035), and in Melbourne, with buildings in advantaged areas scoring better than those in disadvantaged areas (p = 0.055). While only borderline significant, this latter result from Melbourne is worth highlighting as the buildings in the most disadvantaged areas implemented, on average, just 25% of the communal space requirements. This was the lowest implementation score identified – across all cities and areas (although the circulation space score for Melbourne buildings in disadvantaged areas was only marginally higher). Communal space implementation included the amount and dimensions of the space, size of the hardscaped area, presence of significant trees, passive surveillance, and area location (i.e. ground floor versus podium or rooftop). Notably, the provision of communal areas that meet more policy requirements has been associated with increased use by building residents (Kleeman et al. Citation2023b). This underscores that the lack of a communal space, or provision of a space that falls short of the policy requirements, has real consequences for the building residents, as the use of communal areas has been linked to increased social contact between neighbours (Kleeman et al. Citation2023a). Indeed, Larcombe et al. (Citation2019) stress that residents in more disadvantaged areas benefit the most from exposure to nature in their immediate living environments, given the ameliorating effects of nature on psychological stress in a population that is disproportionately affected by mental health problems (Larcombe et al. Citation2019). The provision of high-quality outdoor communal areas in apartment buildings could therefore serve as an important conduit between lower income apartment residents and the benefits of natural environments.

This study has several strengths, including its multi-city study design, buildings drawn from neighbourhoods with different levels of socioeconomic disadvantage, and comprehensive measurement of design requirements drawn from Australian state policies. Measures included the implementation of minimum requirements at the building-level, and selected apartment-level design measures that could help identify any inequalities because of their greater variability. However, there are also limitations relating to sample size, sampling strategy, and scoring system. First, there were possible statistical and inferential consequences of conducting regression analysis on a relatively small sample of buildings (∼n = 172), and this issue was especially acute when the buildings were stratified by city (n = 3) and area-disadvantage categories (n = 3) within-city (). Small sample sizes can translate to low statistical power and an increased risk of a Type II Error. Substantively, this could equate to incorrectly accepting the null hypothesis of no difference between advantaged and disadvantaged areas in building-level policy implementation when in fact differences might have been evident with a larger sample. Second, the selection criteria excluded buildings with less than three storeys or 40 apartments, meaning the patterns identified in this study (or lack thereof) may not be generalisable to smaller complexes. However, our sample of buildings, where most are characterised as medium rise (i.e. 4–8 storeys), reflects the height of much of the current apartment development in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2020b). During the data collection, we validated the plans and elevations that were used to measure the apartment buildings against other sources (e.g. strata plans, site visits, real-estate websites) to ensure the “as-built” development was faithful to the “as-designed” building. If the building layout differed from the approved plans, it was excluded from the study. Thus, our findings are specific to buildings that closely resembled the approved plans, meaning any inferences drawn from the study relate to the development application approval processes, rather than the latter construction phases. Indeed, we cannot discount the possibility that – for buildings where there is a mismatch between the “as-designed” and “as-built” buildings – the changes introduced during construction reduced design quality and, potentially, introduced area-level inequalities.

We scored buildings based on their implementation of 96 policy-derived minimum requirements, drawn from three state policies, rather than examining buildings in each city for their implementation of the policy requirements specific to that state. This was because the overarching aim was to compare design quality by area disadvantage, and the quantitative uptake of minimum design requirements was adopted as a proxy for design quality. However, only the Sydney buildings were developed under an operational policy (i.e. SEPP65 and the ADG), whereas the Perth and Melbourne buildings pre-dated the new policies in their respective states. While Sydney buildings in disadvantaged areas could be expected to score higher than buildings in the disadvantaged areas of Perth and Melbourne (i.e. in the between or inter-city comparison), previous research demonstrates considerable variability in apartment design, with buildings often meeting minimum requirements (and therefore achieving a base level of design quality) in the absence of any policy direction (Foster et al. Citation2022a). Indeed, the minimum requirements are arguably attributes that should be implemented in buildings, regardless of whether they are specified in policy or not. Furthermore, a key focus of this study was the within or intra-city comparison where buildings were developed and approved under the same policy conditions, or lack thereof.

Other limitations relate to the scoring system, whereby buildings were allocated a point if each requirement was implemented as per the policy standard (notwithstanding some graded points for requirements that lacked a threshold or had less stringent wording). However, this approach lacked nuance, as buildings that fell marginally short of the thresholds would not receive a point (e.g. 100% of apartments needed to meet the minimum size standards for the building to receive a point). It should also be noted that the new generation of Australian apartment design policies are performance based, and therefore the policy objectives could be achieved through design innovation rather than meeting minimum standards. While a qualitative assessment of the building plans was outside the scope of the study, we acknowledge that we have applied a quantitative lens to a complex process. Finally, while our study provides a unique perspective on design equity in private market contemporary apartments, and results may not be generalisable to other cities outside of Australia, our approach and methodology provide a template for comparing design quality and/or evaluating similar policies in other jurisdictions. Indeed, future research could examine the design of apartments in cities with greater neighbourhood disparities to benchmark any deficiencies in apartment design and, if necessary, provide evidence to advocate for changes to planning policies and building approval processes that can address substandard design.

5. Conclusion

Australia’s recent apartment construction boom and the quality of the resulting apartments has the potential to inequitably impact low-income populations who are more likely to live in apartments and experience poorer health. We examined the implementation of policy-derived requirements as indicators of design quality and tested for within and between-city differences by neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage. The results were generally positive, but with come caveats. There were few differences in design quality between apartments in low, mid and high disadvantage areas in Sydney and Melbourne, but buildings in the more advantaged areas of Perth delivered a higher level of design quality. Exceptions to this pattern were the very low levels of implementation of communal open space and circulation space requirements observed in buildings in the relatively disadvantaged areas of Melbourne. When comparing buildings in disadvantaged areas between the three cities, Sydney’s buildings in the most disadvantaged areas had the highest policy implementation, followed by Perth, then Melbourne.

Our findings suggest the presence (or absence) of detailed policy instruments interacts with local apartment market conditions to impact design quality. While SEPP65 appears to have protected buildings in Sydney, including at the lower end of the market, the recent policy interventions in WA and Victoria should help reduce the observed inequalities in Perth and contribute to an increase in the uptake of minimum standards in new apartments across all neighbourhoods in Melbourne, where implementation was generally lower. However, these policies differ markedly in the level of direction provided. While SPP7.3 in WA provides detailed design metrics for all the design objectives examined in this study, and essentially replicates SEPP65, questions remain as to whether BADS is sufficiently comprehensive to elevate design quality in Victoria, as the policy contains about half the quantifiable requirements included in the other state policies (Foster et al. Citation2022a). Future iterations of the Victorian policy could benefit from the inclusion of additional requirements to help redress the observed design inequalities between the cities, and specifically target the objectives where buildings from Melbourne’s disadvantaged areas performed worst (i.e. communal and circulation spaces).

Australia has been late to adopt wide-scale apartment living, yet recent construction trends (Shoory Citation2016) and plans to accelerate apartment development to address housing shortages and affordability (Department of Premier and Cabinet Citation2023) suggest further change is imminent. This echoes the urban housing transition that numerous international countries have undergone or are currently experiencing (Seo Citation2016, Shin et al. Citation2023). Yet relatively few international jurisdictions have detailed apartment design policies to help deliver minimum levels of design quality, and assessments of their on-the-ground implementation in new apartment developments are rare. Our findings, together with recent research (Foster et al. Citation2022a, Foster et al. Citation2022b, Hooper et al. Citation2023), emphasise the importance of implementing a comprehensive aspirational design policy to deliver well-designed apartment housing that protects residents’ health, particularly in settings where housing demand is high. For international jurisdictions with existing design governance, it is vital to evaluate the implementation of requirements to assess whether policy objectives are being realised as intended and identify any socioeconomic disparities in implementation or systemic barriers that impede good design.

Ethics Approval

RMIT University Design and Social Context College Human Ethics Advisory Network (Sub-committee of the RMIT Human Research Ethics Committee) (CHEAN B 21146-10/17); The University of Western Australia Human Ethics Research Committee (RA/4/1/8735).

Supplementary Tables.docx

Download MS Word (45.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Study collaborators providing in-kind support include the Department of Planning Lands and Heritage (WA), Office of the Government Architect (WA), Planning Institute of Australia (PIA), Development WA and Heart Foundation. The assistance of apartment residents, resident associations, architects, developers and local government in the study is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request from the first author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allouf, D., Martel, A., and March, A., 2020. Discretion versus prescription: assessing the spatial impact of design regulations in apartments in Australia. Environment and planning B: urban analytics and city science, 47, 1260–1278.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020b. Telling storeys - apartment building heights. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013. Technical paper socioeconomic indexes for areas (SEIFA) 2011. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016. 2071.0 – census of population and housing: reflecting Australia – stories from the census – apartment living. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020a. Building activity, Australia 8752.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022a. Snapshot of New South Wales. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022b. Snapshot of Victoria. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022. Health across socioeconomic groups. Canberra: AIHW.

- Bentley, R., and Baker, E., 2022. Placing a housing lens on neighbourhood disadvantage, socioeconomic position and mortality. The lancet public health, 7, e396–e397.

- Braubach, M., Savelsberg, J., and WORLD Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2009. Social inequalities and their influence on housing risk factors and health: a data report based on the WHO LARES database / by matthias braubach and jonas salvesberg. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- CAN, 2015. Property insights: Australia’s apartment boom reaches record high. Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

- Cheng, L. 2016. Victoria’s draft apartment standards released. Architecture AU [Online]. [Accessed 23/08/2022].

- City of Vancouver, 2020. Housing design and technical uuidelines. City of Vancouver: Community Services, Vancouver

- City of Melbourne, 2013. Understanding the quality of housing design. Melbourne: City of Melbourne.

- Clare, K., and Clare, L. 2014. Improving the quality of housing. Architecture AU [Online].

- Daniel, L., Baker, E., and Williamson, T., 2019. Cold housing in mild-climate countries: a study of indoor environmental quality and comfort preferences in homes, Adelaide, Australia. Building and environment, 151, 207–218.

- Department of Housing, 2013. The housing we’d choose: a study for Perth and Peel. Perth: Department of Housing, Department of Planning.

- Department of Housing Planning and Local Government, 2018. Sustainable urban housing: design standards for new apartments. In: Department of housing planning and local government. Ireland: Government of Ireland.

- Department of Premier and Cabinet, 2023. Victoria’s housing statement: the decade ahead 2024-2034. In: Department of premier and cabinet. Melbourne: State of Victoria.

- Easthope, H., et al. 2020. Improving outcomes for apartment residents and neighbourhoods. AHURI Final Report No. 329. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- Easthope, H., et al. 2023. Delivering sustainable apartment housing: new build and retrofit. AHURI Final Report No. 400. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- Easthope, H., Troy, L., and Crommelin, L. 2017. Equitable density: report 1 the building scale. Shelter brief 61. Sydney: City Futures Research Centre, UNSW.

- EUROSTAT. 2021. Housing statistics. Housing in Europe. European Union.

- Foster, S., et al., 2019. High life study protocol: a cross-sectional investigation of the influence of apartment building design policy on resident health and well-being. BMJ open, 9, e029220.

- Foster, S., et al., 2020. The high life: a policy audit of apartment design guidelines and their potential to promote residents’ health and wellbeing. Cities, 96, 102420.

- Foster, S., et al., 2022a. An evaluation of the policy and practice of designing and implementing healthy apartment design standards in three Australian cities. Building and environment, 207, 108493.

- Foster, S., et al., 2022b. Grand designs for design policy: associations between apartment policy standards, perceptions of good design and mental wellbeing. SSM – population health, 20, 101301.

- Giles-Corti, B., et al., 2022a. What next? expanding our view of city planning and global health, and implementing and monitoring evidence-informed policy. Lancet glob health, 10, e919–e926.

- Giles-Corti, B., et al., 2022b. Spatial and socioeconomic inequities in liveability in Australia’s 21 largest cities: does city size matter? Health & place, 78, 102899.

- Hooper, P., et al., 2022. Measuring the high life: a method for assessing apartment design policy implementation. Methodsx, 9, 101810.

- Hooper, P., et al., 2023. The architecture of mental health: identifying the combination of apartment building design requirements for positive mental health outcomes. The lancet regional health – western pacific, 37, 1–15.

- Howden-Chapman, P., et al., 2012. Health, well-being and housing. In: S. J. Smith, ed. International encyclopedia of housing and home. San Diego: Elsevier, 344–354.

- Kearns, A., 2003. Living in and leaving poor neighbourhood conditions in England. Housing studies, 18, 827–851.

- Kelly, J., Weildmann, B., and Walsh, M., 2011. The housing we’d choose. Melbourne: Grattan Institute.

- Kleeman, A., et al., 2022. A new Australian dream? exploring associations between apartment design attributes and housing satisfaction in three Australian cities. Cities, 131, 104043.

- Kleeman, A., et al., 2023a. The impact of the design and quality of communal areas in apartment buildings on residents’ neighbouring and loneliness. Cities, 133, 104126.

- Kleeman, A., et al., 2023b. Research note: associations between the implementation of communal open space design guidelines and residents’ use of these spaces in apartment developments. Landscape and urban planning, 230, 104613.

- Ladybug Tools, 2021. Food4Rhino – apps for rhino and grasshopper. Ladybug Tools.

- Larcombe, D.-L., et al., 2019. High-rise apartments and urban mental health – historical and contemporary views. Challenges, 10, 1–15.

- Mayor of London, 2020. Housing design quality and standards: supplementary planning guidance. Module C pre-consultation draft. London: Mayor of London.

- Moore, T., et al., 2015. Improving design outcomes in the built environment through design review panels and design guidelines. State of Australian cities conference, Gold Coast, Australia.

- Mould, P., 2011. A review of the first 9 years of the NSW state environmental planning policy No. 65 (SEPP 65). Architecture Australia, 100, 49–49.

- NEARMAP, 2021. Nearmap high fidelity aerial imagery. Sydney: Nearmap.

- Nethercote, M., and Horne, R., 2016. Ordinary vertical urbanisms: city apartments and the everyday geographies of high-rise families. Environment and planning A, 48, 1581–1598.

- Poruschi, L., and Ambrey, C.L., 2018. Densification, what does it mean for fuel poverty and energy justice? An empirical analysis. Energy policy, 117, 208–217.

- Seo, J.-K., 2016. Housing policy and urban sustainable development: evaluating the process of high-rise apartment development in Korea. Urban policy and research, 34, 330–342.

- Shergold, P., and Weir, B., 2018. Building confidence: improving the effectiveness of compliance and enforcement systems for the building and construction industry across Australia. Canberra: Australian Department of Industry Science Energy and Resources.

- Shin, Y., Kwon, Y., and Seo, D., 2023. Rethinking developmental state intervention in the housing supply of a transitional economy: evidence from Hanoi, Vietnam. Land Use policy, 132, 106795.

- Shoory, M. 2016. The growth of apartment construction in Australia. Bulletin. Reserve Bank of Australia.

- Stata Corporation, 2016. Stata statistical software release 14.1. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation.

- The State of Victoria Department of Environment Land Water & Planning, 2021. Apartment design guidelines for Victoria: environment land water and planning & office of the Victorian government architect. Melbourne: State of Victoria.

- WA Planning Commission, 2019. Design review guide. Department of planning lands and heritage. Perth: WA Planning Commission.

- World Health Organization, 2018. WHO housing and health guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Yang, H., Oldfield, P., and Easthope, H., 2022. Influences on apartment design: a history of the spatial layout of apartment buildings in Sydney and implications for the future. Buildings, 12, 628.