Abstract

This field study set out to test whether consumers’ history of making decisions in a particular choice context moderated the effectiveness of a nudge intervention to reduce meat consumption. In a Danish hospital canteen that served both staff members and visitors, a combination of nudges (Chef’s recommendation sticker + prominent positioning) was implemented to promote vegetarian sandwiches. The sales of these sandwiches increased from 16.45% during the baseline period to 25.16% during the nudge intervention period. Most notably, this increase was caused by the visitors, who had weak location-bound preferences. Hospital staff members (who had strong location-bound preferences) were unaffected by the nudge in their choice. This is an important finding because the two consumer groups did not differ on their person-bound preferences for meat. It seems that behaviour change is best predicted by location-bound preferences, whereas the behaviour itself is best predicted by person-bound preferences. These findings can help organizations in estimating whether a nudge intervention has enough potential for behaviour change, or whether more directive policies are required.

Recent meta-analyses indicate that nudge interventions such as placing healthy food items at eye-level, making the desirable choice the default in registration systems, and informing users about local behavioural norms have a small to medium effect on peoplés decisions (e.g., Arno & Thomas, Citation2016; Jachimowicz et al., Citation2019; Hummel & Maedche, Citation2019; Mertens et al., Citation2022). Nudges are changes in the choice architecture that facilitate a particular desirable choice by making use of decision makers’ intuitive decision making strategies, for example by tapping into certain heuristics or relying on affordances principles (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008). In the last decade, an increasing number of policy makers have implemented nudge interventions with great enthusiasm, often to discover that using a copy and paste approach is no guarantee for changing behaviour (cf. Osman et al., Citation2020). Frustration about this so-called “simple behaviour change tool” (cf. De Ridder et al., Citation2020) has sparked a call for a heterogeneity revolution in behavioural insights research (Bryan et al., Citation2021; Szaszi et al., Citation2022). This call encourages researchers to look beyond main effects of nudge interventions and specify important moderating characteristics of the target population and the choice environment. In this article, we respond to this call and build on previous nudge research that considers a priori preferences as important moderators of successful nudge interventions (De Ridder et al., Citation2020; Osman et al., Citation2020; Venema, Citation2020; Szaszi et al., Citation2018). We distinguish between preferences that people carry with them across choice contexts (i.e., person-bound preferences) and preferences that are the result of previous interactions in a specific choice context (i.e., location-bound preferences) and investigate their potential moderating role in nudging vegetarian choices.

A priori preferences refer to the preferences that people can have before they enter the environment where they make their decision. These can consist of intentions (e.g., working at a stand-up desk; Venema et al., Citation2018), attitudes (e.g., enjoying the taste of cola; Venema et al., Citation2019), physical needs (e.g., feeling hungry; Otterbring, Citation2019), values (e.g., caring about protecting nature; Gatersleben et al., Citation2014), and habits (e.g., washing hands; Diefenbacher et al., Citation2020). Mapping a priori preferences of target audiences allows for an estimation of the number of consistent choosers (cf. Goldin, Citation2015) in that particular choice setting—and thereby indirectly provides an estimation of the effect size of nudge interventions. Consistent choosers have a strong a priori preference for a particular choice option and are consequently less affected by choice architectural obstacles towards this option. For example, Bronchetti et al. (Citation2013) found that a default nudge that allocated tax refunds into a savings account was ineffective for citizens who had beforehand made plans to spend this money. Similarly, a study in which 2,300 supermarket customers across 28 stores were surveyed, showed that customers who had an ‘aisle-routine’ were 24% less likely to make unplanned purchases (Inman et al., Citation2009). De Wijk et al. (Citation2016) argued that their repositioning nudge in a supermarket to promote whole wheat bread was ineffective, because customers simply went looking for their usual brand when they could not find it in the expected place. Estimating what proportion of the target population is unlikely to be nudged is particularly relevant when considering which policy tool should be used in order to change behaviour. If a considerable part of the target audience has strong preferences for the undesirable choice, more directive policies (e.g. prohibitions, economic rewards, or taxes) might be necessary to achieve the desired shift in behaviour.

For policy makers, it is often impractical or unfeasible to administer questionnaires to assess their target audiences’ attitudes and intentions. Therefore, we sought to test whether it would be sufficient to account for peoplés decision-making history in a particular choice context. Online and lab-based nudge studies are excellent settings to test moderating effects of a priori preferences that people “bring” with them into different choice contexts (i.e. person-bound preferences), but they miss one important element: location-bound preferences. When people frequently make decisions in the same environment they are likely to develop habits.

Habits have proven to be relatively resilient against traditional intervention techniques that aim to inform and persuade people to change their behaviour (Verplanken & Wood, Citation2006). One important consequence of an established habit is that non-habitual options will receive less consideration. First, when previous choices have been found satisfactory there is less motivation to explore the environment for alternatives. Second, habits have been shown to govern unconscious attention to the environment, prioritizing stimuli in the environment that enable the execution of habitual behaviour (Anderson et al., Citation2021; Jiang, Citation2018). A nudge intervention that relies on attention to the choice context might thus have to compete with established habits for the decision-makers’ attention. In one recent field study it was shown that green footsteps leading to a salad bar (i.e., a salience nudge) were not effective in promoting healthy food choices among the majority of regular customers, but showed promising results among interns and guests (Bauer et al., Citation2021). This finding suggests that regular customers might have location-bound preferences.

Inspired by the work of Bauer and colleagues, the current study set out to test the effectiveness of a nudge intervention for different customer types in a hospital café that is used by patients, visitors, and hospital staff. We hypothesized that a nudge intervention will be less likely to influence decisions of frequent customers (i.e. hospital staff) compared to new customers (i.e. patients and visitors). Specifically, we hypothesized that this would be caused by location-bound preferences, rather than person-bound preferences. Location-bound preferences were operationalized by how often customers bought the same food-items when they were at this particular café. Person-bound preferences exert influence across choice settings, but can still be habitual in the mental schema of “when buying a sandwich” (e.g., Phillips & Mullan, Citation2022). We therefore chose to operationalize person-bound preferences as the habit of selecting a meat sandwich when buying a sandwich. To our knowledge, the current study is the first that assesses both person-bound and location-bound a priori preferences as moderators of a nudge intervention.

Study context

The hospital where this research took place aims to reduce their carbon footprint in all areas of their organization. The cafés are transitioning from an abundance of meat options to more plant-based or vegetarian options. After receiving customer complaints about a previous attempt to reduce the meat-portion sizes, the café asked for our help in promoting their vegetarian options instead. Our nudge intervention focused on promoting vegetarian sandwiches, as sandwiches were the most popular food item in the café.

Previous studies that employed nudges to reduce meat consumption have shown promising results. One study in Swedish university canteens showed that making the vegetarian dishes on the menu more salient increased sales with 6% (Kurz, Citation2018). We are aware of two studies that measured person-bound preferences (e.g., attitudes and past behaviour in other settings) as moderators for the effectiveness of a nudge aiming to reduce meat consumption. Venema et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that participants who felt conflicted about their general meat consumption were more susceptible to a social-norm nudge to reject meat products in an online supermarket. Another online study that accounted for participants’ meat consumption in the previous week, found that a ‘Chef’s Recommendation’ nudge was particularly effectively for infrequent vegetarian eaters (Bacon & Krpan, Citation2018). Inspired by these studies we designed a salient Chef’s recommendation sticker for the vegetarian sandwich bags (see ). We opted for this nudge as it combines a powerful visual salience effect (Feldman et al., Citation2011; Kurz, Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2016), and an expertise social influence effect (Bacon & Krpan, Citation2018; Yang & Mattila, Citation2020).

We first conducted a pilot study with customers in the hospital café to 1) test the assumption that staff members indeed had stronger location-bound preferences for particular food items in the café than visitors (i.e., patients and their guests) and 2) to test whether the sticker made the vegetarian sandwiches look more appetizing. Institutional review boards are not mandatory in Denmark, but both the pilot study and the main study were conducted in full accordance with the Ethical Guidelines of the declaration of Helsinki. All data is available upon request from the first author, TV.

Pilot study

Methods

Participants, procedure and design

During two days, 125 customers (60% women) were invited to take part in a 4-minute customer satisfaction study. The sample consisted of 33.6% staff members and 66.4% visitors. Besides some demographics, we measured their location-bound preferences and person-bound preferences regarding meat sandwiches. An experimental between-subjects design was used to test whether the chef’s recommendation sticker would influence the attractiveness of the vegetarian sandwich and would influence a decision in a hypothetical scenario (see Supplementary Materials for a full description of procedure and measures).

Measurements and materials

Demographics

Besides age and gender, visit frequency was measured — first time (1), 1-2 times before (2), 3-5 times before (3), I come here often (4), and I come here daily (5). Multiple dietary preferences could be selected (i.e., Gluten-free, Vegetarian, Vegan, Halal, other…). Customers indicated their role in the hospital café (i.e., staff, patient, visitor, or other). Since we were interested in differentiating between regular and non-regular customers, customer role was recoded into staff vs. visitor.

Location-bound preferences

To measure location-bound preferences, participants were asked how often they buy the same thing(s) when they visit the café. Answer options were never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), mostly (4), and always (5). This question was not displayed to participants who had indicated that this was their first visit.

Person-bound preference

Person-bound preference for meat sandwiches was measured with three items that were selected from the Self-report Habit Index to represent the different subscales (Verplanken & Orbell, Citation2003). Participants indicated their agreement (1= disagree to 5 = agree) in response to the following statement: “When buying a sandwich, choosing one with meat in it is something that…I do often” [freq], “…is typically me” [identity], and “…I do without thinking about it” [automaticity]. A higher score indicates a stronger habitual meat sandwich preference. Cronbach’s alpha was .75.

Results

Staff vs. visitors

As expected, hospital staff (Mdn = 4) had a significantly higher visit frequency than visitors, Mdn = 3, U = 1238, z =-2.74, p = .006, r = −.25. Moreover, in support of our hypothesis, the hospital staff had a stronger location-bound preference (M = 3.29, SD = 1.04) than the visitors, M = 2.88, SD = 0.93, t (95) = 2.02, p = .047, d = 0.419. The customer groups did not differ on habitual meat sandwich preference, t (94) = 0.28, p = .978. In fact, both the hospital staff (M = 3.62, SD = 1.25) and the visitors (M = 3.61, SD = 1.16) had a strong person-bound preference for meat sandwiches.

Effect of chef’s recommendation sticker

The Chef’s recommendation sticker did not change the appetizing score of the vegetarian sandwich, p = .675. Nor did it influence participants’ hypothetical choice, p = .404. See supplementary materials for details.

Discussion

The pilot study corroborated our main hypothesis: that staff members had stronger location-bound preferences than visitors. On average, both staff members and visitors had a strong person-bound preference for meat sandwiches. The pilot study also showed that the chef’s recommendation sticker by itself was not enough to influence attractiveness nor (hypothetical) choice of the vegetarian sandwich.

The field study

Based on the pilot study findings, we decided to employ a combination of four nudges during the intervention period to stimulate the consumption of vegetarian sandwiches. Moreover, a meta-analysis indicated that combined nudges typically have a larger effect compared to single nudge interventions (Cadarion & Chandon, Citation2020). Besides the salient Chef’s recommendation stickers on the bags, one vegetarian sandwich was displayed on a plate at eye-level with the content clearly visible. This plate was accompanied by a sign that read “Kokken anbefaler” and a brief description of the café’s sustainability goals, similar to a dish-of-the-day nudge (e.g., Saulais et al., Citation2019). The word “vegetarian” was not used — just the name of the ingredients (e.g., grilled vegetables with pesto). Third, all vegetarian sandwiches were placed in first line-of-sight from the typical customer flow direction (Bucher et al., Citation2016). Fourth, the labels on vegetarian sandwiches were slightly more colourful and the bags were closed more aesthetically than meat sandwiches (see ).

Method

Study design

In this field study we collected both objective sales data and survey data to test our hypotheses. The study was conducted on weekdays between the 10th of May until the 23rd of June in 2021. During the whole study period, the café agreed to keep the ratio vegetarian to meat sandwiches constant at 1:3. The first 14 days served as a baseline measurement of the number of vegetarian and meat sandwiches sold to customers (split for staff and visitors). The nudge intervention was implemented June 1st. We collected survey data during the last two days of the intervention period. The main aim of the survey data was to test whether location-bound and person-bound preferences were related to attention to the nudge, specifically the Chef’s recommendation sticker.

Objective sales data

The pilot study confirmed that location-based preferences were stronger in hospital staff. In order to connect location-based a priori preferences to actual purchases, a ‘customer type’ button was installed in the cash register system. For each transaction, café clerks first had to press the staff or visitor button, before entering the purchased food items. The café personnel were briefed about the button and confirmed that they could easily recognize staff members by their uniforms or employee badges.

Survey

Procedure

All customers who bought something at the café were asked to participate in the survey study. The survey was administered in Qualtrics on mobile phones and laptops. After participants gave informed consent, they answered the same demographic questions as in the pilot study and indicated whether they had also taken part in the previous survey. They then proceeded to a logo-recognition task. Next, participants were asked if they had bought a sandwich and whether their sandwich had the chef’s recommendation sticker on it (i.e., whether they had bought a vegetarian sandwich). Thereafter, we measured their location-bound and person-bound preferences. Finally, participants gave their opinion about the café’s ambition to make the food more climate friendly by promoting vegetarian choices, and were prompted to leave any additional comments or feedback. Participants were thanked for their time and received a voucher for a hot beverage.

Participants

One-hundred and eighty-six participants (62.9% women) participated in the exit survey. Their average age was 43.32 (SD = 14.11). Nearly half of the sample consisted of hospital staff (n = 89, 47.8%). For 33 participants it was their first visit (17.7%). Three participants had also participated in the pilot study. Ten participants adhered to a vegetarian or vegan diet (5.38%). The majority (78.5%) had no dietary preferences.

Measurements and materials

Logo recognition task

We used a recognition task to assess whether customers had noticed the chef’s recommendation sticker, as increased salience is presumed to be an important part of the working mechanism (Wilson et al., Citation2016; Bacon & Krpan, Citation2018). To avoid social desirable answers the sticker was “hidden” among six other logos (see ). The position of the logos on the screen was randomized. Participants were asked to select all the images that they had seen while in the café. Besides the logo of the café and the chef’s recommendation sticker, none of the other logos were actually present in the café. Participants could also indicate that they had seen none of the logos.

The other survey questions were the same as in the pilot study. The person-bound preference as operationalized with the three SRHI-items had high internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha = .78.

Results

Nudge effect on sales

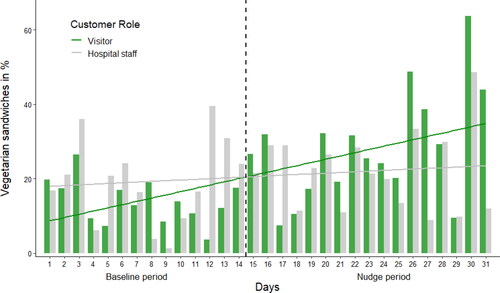

During the entire study period (baseline + intervention period) a total of 24,816 products were bought in the café, 51.16% was made by visitors and the rest by hospital staff. shows the percentage of sold vegetarian sandwiches per day for both customer types. The percentage of sold vegetarian sandwiches increased from 16.48% at baseline to 25.19% during the intervention period. In support of our hypothesis, this increase seems to be caused by a change in behaviours from the visitors (i.e., customers with weaker location-bound preferences). For the visitors the sales of vegetarian sandwiches increased from 13.94% to 28.24%, whereas for the staff members the sales remained relatively stable (from 19.02% in the baseline period to 22.15% during the intervention period). A chi-square test on the amount of vegetarian options showed significant difference between the two conditions and customer roles, χ2 = 21.99, p <.001. Because the degree of dependency across the observations is unknown, but most likely different for staff and visitors, the statistical inference tests need to be interpreted with caution.

Survey data

Location-bound preferences

A Mann-Whitney U test showed that staff members had a significantly higher café visit frequency compared to visitors, p < .001; this is in support of our assumption. With regard to location-bound preferences, the hospital staff (M = 3.44, SD = 0.69) had a significantly stronger location-bound preference than visitors, M = 2.86, SD = 0.78, t (151) = 4.79, p <.001, Cohen’s d = 0.78. This replicates the pilot study findings and supports the use of customer role as a proxy for location-bound preferences in the sales data.

Person-bound preferences

Both the hospital staff (M = 3.36, SD = 1.22) and the visitors (M = 3.58, SD = 1.26) had a strong habitual preference for meat sandwiches, but the difference between the groups was not significant (p = .222).

Comparison of sales and survey data

The sales data showed that during the two survey days 483 sandwiches were sold (of which 196 were vegetarian sandwiches). Eighty participants in the exit survey had bought a sandwich, of which 23 vegetarian. shows the distribution across customer role, indicating that visitors who bought a meat-sandwich were over-represented in the survey data. A binary logistic regression was conducted with meat vs. vegetarian sandwich as dependent variable, and customer role and person-bound preference as predictors. The regression showed that person-bound preference was a significant predictor of sandwich choice, b = .42, W = 4.45, Exp(B) = 1.53, 95% CI [1.030, 2.256], p = .035. Customer role did not significantly predict sandwich choice, p = .673. This means that while location-bound preferences moderated behaviour change due to the nudge, the choice within the nudge period was best predicted by person-bound preferences.

Table 1. Survey data on sandwich choice compared to sales data during last two intervention days.

Attention

We hypothesized that customers with strong location-bound preferences would be less likely to notice a salience nudge. A binary logistic regression was run with location-bound and person-bound preferences as predictors of attention for the chef’s recommendation sticker. Contrary to our hypothesis, location-bound preferences were not a significant predictor of attention, b = −.03, W = 0.01, Exp(B) = 1.03, 95% CI [0.626, 1.689], p = .911. On the other hand, participants with weak person-bound preferences for meat sandwiches were more likely to have noticed the sticker, b = −.31, W = 4.18, Exp(B) = 0.73, 95% CI [0.543, 0.987], p = .041.

From the 186 participants in the survey 44 (23.7%) had seen the chef’s recommendation sticker. In comparison, 47 participants (25.3%) had noticed the cafés logo. Eighty participants (43%) indicated to have seen none of the logos. A chi-square test showed that hospital staff were significantly more likely than visitors to have noticed the sticker, χ2 = 5.76, p = .028. We did not find support for the hypothesis that people with strong location-bound preferences were less likely to notice a salience nudge. Instead, the data showed that when people have strong person-bound a priori preferences for the alternative choice option they were less likely to notice the nudge.

Acceptance

When asked what customers thought about the café’s goal to make their food more climate friendly by promoting vegetarian choices, the majority thought it was a (very) good idea (61.3%). 28% were neutral or had no opinion about it, and a minority thought it was a (very) bad idea (10.8%). A regression with both customer role and person-bound preferences showed that customers with stronger person-bound preference for meat sandwiches were significantly more likely to disapprove of nudging vegetarian food, B = −.253, t = −3.54, 95% CI [-0.394, −0.112], p <.001. Customer role did not make a difference, p = .504.

General discussion

This study set out to investigate whether the effectiveness of a nudge intervention would be moderated by the target groups’ decision-making history in that specific choice context, i.e., location-bound a priori preferences. The combination of nudges, including prominent positioning and a Chef’s recommendation sticker, successfully increased the overall sale of vegetarian sandwiches with 52.85% compared to a baseline. In line with our hypotheses and previous research (e.g. Bauer et al., Citation2021) the findings showed that the distinction between regular and newer customers provides a fruitful indication of potential effectiveness of nudge interventions. Moreover, in the absence of membership cards or other means of recording the target group’s decision-making history, customer role (staff vs. visitor) was a suitable proxy for location-bound preferences. The percentage of sold vegetarian sandwiches remained stable around 20% for regular customers (i.e., hospital staff), whereas it doubled for the newer customers (i.e., patients and visitors). Findings from both the pilot study and the exit survey show support for the idea that this is indeed due to location-bound preferences.

We also found that the strength of person-bound a priori preferences was the best predictor for both the hypothetical and actual choice. In this study, we focused primarily on measuring person-bound preference for the alternative to the nudged choice (i.e., meat sandwiches), because we suspected that this customer segment is most likely to demonstrate reactance and this would negatively affect the business of the café. Knowing how large this group is can be a consideration when deciding between different types of behaviour-change policies. In line with findings in the nudge literature (e.g., Reynolds et al., Citation2019; Hagmann et al., Citation2018; Venema et al., Citation2018) customers with strong person-bound preferences for meat sandwiches were more likely to disapprove of the nudge intervention that promoted vegetarian choices. However, in this particular target population relatively few were strongly against the idea of nudging vegetarian food for climate purposes.

In many situations, location-bound and person-bound preferences will be highly similar and will both provide a good estimation of the number of inconsistent choosers (Goldin, Citation2015). For one-off decisions person-bound preferences will provide the best estimation of the number of consistent choosers, but as the findings from this study show, location-bound preferences are imperative for repeated decisions in the same choice architecture. Naturally, location-bound preferences can be formed overtime when person-bound preferences are acted upon in a new context (Verplanken & Orbell, Citation2022); in which case they are equally good estimators of potential nudge effect size. Future research is necessary to further define what location-bound preferences are beyond this first conceptualization, for example how different locations can become clustered in the same mental schema (e.g., different locations of the same supermarket). The Situated Cognition Perspective seems a fruitful avenue for further elaboration (e.g., Best & Papies, Citation2017). A better theoretical understanding of location-bound preferences would then be able to advice on how much of a choice environment needs to be altered in order to disrupt location-bound preferences.

The distinction between person-bound and location-bound preferences is valuable as the window for a deviation from intentions and attitudes (i.e. person-bound a priori preferences) might be opened in new choice contexts, if the intentions and attitudes are not solid (Carden & Wood, Citation2018). Typically, people are able to cope well with inconsistencies between their behaviours and intentions if they can attribute their choice to external factors (e.g., “I don’t normally drink on weekdays, but now we have cause for celebration”; e.g., Taylor et al., Citation2014). In the context of this study it seems that while customers preferred a sandwich with meat, this preference was overruled when the choice architecture suggested a better alternative (e.g., the chefs’ recommendation; see also Bacon & Krpan, Citation2018).

Despite the promising findings, some limitations need to be addressed. First, it should be noted that the staff members and visitors differed on other factors than location-based preferences alone; the hospital staff were on average younger and it might be presumed that they have higher health literacy. Older generations in Denmark, which were strongly represented in our visitor sample, might be less familiar with vegetarian alternatives such as falafel or beetroot burgers. These demographics might explain the initial baseline results where staff members were more likely to buy a vegetarian sandwich compared to the visitors. Previous research demonstrated that favourable social norms predict trying-out novel foods (Jensen & Lieberoth, Citation2019). This could explain why the chef’s recommendation sticker and sign helped to “nudge” the visitor population towards these vegetarian alternatives.

Another limitation is that it is difficult to tease apart which element of the nudge intervention was the “active ingredient”, as we used a combination of different nudges. The “hail-shot” approach has been used frequently in nudge research where the main goal is behaviour change, rather than uncovering the precise working mechanism (e.g. Velema et al., Citation2018). The findings in the current study suggest that the chef’s recommendation sticker alone is an insufficient ingredient; and that positioning and a sign that explained the meaning of the sticker were necessary components. We did not find support for the idea that customers with strong location-bound preferences would be less likely to notice the sticker, instead person-bound preferences turned out to be a reasonable predictor of attention to this element of the nudge intervention.

The findings from this initial study suggest that nudge interventions would yield larger effects in choice environments in which the target audience does not have a history of making decisions. This explanation fits with meta-analytic findings showing that defaults options tend to have larger effect sizes, because the choices for which the defaults are employed are typically on-off decisions (e.g., Mertens et al., Citation2022). Future research could investigate whether nudges work better for example at hotel buffets than at canteen buffets. Nudges at train stations (e.g., Kroese et al., Citation2016) might be more effective in weekends than during weekdays, because commuters are more likely to have location-bound preferences. Similarly, freshmen in college might be more likely to be influenced by nudges in their campus than senior students, etc. If the target audience includes a large proportion of recurrent users with strong location-based preferences (consistent choosers), then nudge effects can be expected to be small (Goldin, Citation2015). Here, a nudge approach might need to be abandoned in favour of incentive-based interventions (e.g., discounts) or prohibition policies (e.g., Meat-less Mondays).

Conclusion

The current study adds to the trend of using customer data to estimate a priori preferences to predict the success of nudge interventions (see also Gonçalves et al., Citation2021). This study combined sales data with survey data in a field study to better understand the effectiveness of a nudge intervention in relation to the a priori preferences of the target audience. Researchers and policymakers can use these insights to consider whether their target audience are frequent decision-makers in the choice context in which they hope to see a behavioural change.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (176.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Thomas Ellegaard Tøfting, Anja Groth Odgaard, Karen Poulsen, Andreas Bruselius, Simon Lehm Frandsen and Camilla Goul for their help in the data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, B. A., Kim, H., Kim, A. J., Liao, M. R., Mrkonja, L., Clement, A., & Grégoire, L. (2021). The past, present, and future of selection history. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 130, 326–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.09.004

- Arno, A., & Thomas, S. (2016). The efficacy of nudge theory strategies in influencing adult dietary behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3272-x

- Bacon, L., & Krpan, D. (2018). ( Not) Eating for the environment: The impact of restaurant menu design on vegetarian food choice. Appetite, 125, 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.006

- Bauer, J. M., Bietz, S., Rauber, J., & Reisch, L. A. (2021). Nudging healthier food choices in a caféteria setting: A sequential multi-intervention field study. Appetite, 160, 105106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105106

- Best, M., & Papies, E. K. (2017). Right here, right now: Situated interventions to change consumer habits. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(3), 333–358. https://doi.org/10.1086/695443

- Bronchetti, E. T., Dee, T. S., Huffman, D. B., & Magenheim, E. (2013). When a nudge isn’t enough: Defaults and saving among low-income tax filers. National Tax Journal, 66(3), 609–634. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2013.3.04

- Bryan, C. J., Tipton, E., & Yeager, D. S. (2021). Behavioural science is unlikely to change the world without a heterogeneity revolution. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(8), 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01143-3

- Bucher, T., Collins, C., Rollo, M. E., McCaffrey, T. A., De Vlieger, N., Van der Bend, D., Truby, H., & Perez-Cueto, F. J. A. (2016). Nudging consumers towards healthier choices: a systematic review of positional influences on food choice. British Journal of Nutrition, 115(12), 2252–2263. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114516001653

- Cadario, R., & Chandon, P. (2020). Which healthy eating nudges work best? A meta-analysis of field experiments. Marketing Science, 39(3), 465-486. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2018.1128

- Carden, L., & Wood, W. (2018). Habit formation and change. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 20, 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.12.009

- De Ridder, D., Feitsma, J., van den Hoven, M., Kroese, F., Schillemans, T., Verweij, M., Venema, T. A. G., Vugts, A., & de Vet, E. (2020). Simple nudges are not so easy. Behavioural Public Policy, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.36

- de Wijk, R. A., Maaskant, A. J., Polet, I. A., Holthuysen, N. T., van Kleef, E., & Vingerhoeds, M. H. (2016). An in-store experiment on the effect of accessibility on sales of wholegrain and white bread in supermarkets. Plos One, 11(3), e0151915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151915

- Diefenbacher, S., Pfattheicher, S., & Keller, J. (2020). On the role of habit in self‐reported and observed hand hygiene behavior. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 12, 125– 143. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12176

- Feldman, C., Mahadevan, M., Su, H., Brusca, J., & Ruzsilla, J. (2011). Menu engineering: A strategy for seniors to select healthier meals. Perspectives in Public Health, 131(6), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913911419897

- Gatersleben, B., Murtagh, N., & Abrahamse, W. (2014). Values, identity and pro-environmental behaviour. Contemporary Social Science, 9(4), 374–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2012.682086

- Goldin, J. (2015). Which way to nudge: uncovering preferences in the behavioral age. Yale Law Journal, 125, 226–271. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2570930

- Gonçalves, D., Coelho, P., Martinez, L. F., & Monteiro, P. (2021). Nudging consumers toward healthier food choices: A field study on the effect of social norms. Sustainability, 13(4), 1660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041660

- Hagmann, D., Siegrist, M., & Hartmann, C. (2018). Taxes, labels, or nudges? Public acceptance of various interventions designed to reduce sugar intake. Food Policy, 79, 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.06.008

- Hummel, D., & Maedche, A. (2019). How effective is nudging? A quantitative review on the effect sizes and limits of empirical nudging studies. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 80, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2019.03.005

- Inman, J. J., Winer, R. S., & Ferraro, R. (2009). The interplay among category characteristics, customer characteristics, and customer activities on in-store decision making. Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.5.19

- Jachimowicz, J. M., Duncan, S., Weber, E. U., & Johnson, E. J. (2019). When and why defaults influence decisions: A meta-analysis of default effects. Behavioural Public Policy, 3(2), 159–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2018.43

- Jensen, N. H., & Lieberoth, A. (2019). We will eat disgusting foods together–Evidence of the normative basis of Western entomophagy-disgust from an insect tasting. Food Quality and Preference, 72, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.08.012

- Jiang, Y. V. (2018). Habitual versus goal-driven attention. Cortex, 102, 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2017.06.018

- Kroese, F. M., Marchiori, D. R., & De Ridder, D. T. (2016). Nudging healthy food choices: a field experiment at the train station. Journal of Public Health, 38(2), e133–e137. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv096

- Kurz, V. (2018). Nudging to reduce meat consumption: Immediate and persistent effects of an intervention at a university restaurant. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 90, 317–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2018.06.005

- Mertens, S., Herberz, M., Hahnel, U. J. J., & Brosch, T. (2022). The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioural domains. PNAS, 119, e2107346118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2107346118

- Osman, M., McLachlan, S., Fenton, N., Neil, M., Löfstedt, R., & Meder, B. (2020). Learning from behavioural changes that fail. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(12), 969–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.09.009

- Otterbring, T. (2019). Time orientation mediates the link between hunger and hedonic choices across domains. Food Research International, 120, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2019.02.032

- Phillips, A. L., & Mullan, B. A. (2022). Ramifications of behavioural complexity for habit conceptualization, promotion, and measurement. Health Psychology Review, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2022.2060849

- Reynolds, J. P., Archer, S., Pilling, M., Kenny, M., Hollands, G. J., & Marteau, T. M. (2019). Public acceptability of nudging and taxing to reduce consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and food: A population-based survey experiment. Social Science & Medicine, 236, 112395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112395

- Saulais, L., Massey, C., Perez-Cueto, F. J., Appleton, K. M., Dinnella, C., Monteleone, E., Depezay, L., Hartwell, H., & Giboreau, A. (2019). When are “Dish of the Day” nudges most effective to increase vegetable selection? Food Policy, 85, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2019.04.003

- Szaszi, B., Higney, A., Charlton, A., Gelman, A., Ziano, I., Aczel, B., Goldstein, D. G., Yeager, D. S., & Tipton, E. (2022). No reason to expect large and consistent effects of nudge interventions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(31), e2200732119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200732119

- Szaszi, B., Palinkas, A., Palfi, B., Szollosi, A., & Aczel, B. (2018). A systematic scoping review of the choice architecture movement: Toward understanding when and why nudges work. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 31(3), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2035

- Taylor, C., Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2014). ‘I deserve a treat!’: Justifications for indulgence undermine the translation of intentions into action. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53(3), 501–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12043

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

- Velema, E., Vyth, E. L., Hoekstra, T., & Steenhuis, I. H. (2018). Nudging and social marketing techniques encourage employees to make healthier food choices: a randomized controlled trial in 30 worksite cafeterias in The Netherlands. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 107(2), 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx045

- Venema, T. A. G. (2020). Preferences as boundary condition of nudge effectiveness: The potential of nudges under empirical investigation [Doctoral dissertation]. Utrecht University. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/390684

- Venema, T. A. G., Kroese, F. M., & De Ridder, D. T. D. (2018). I’m still standing: A longitudinal study on the effect of a default nudge. Psychology & Health, 33(5), 669–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1385786

- Venema, T. A. G., Kroese, F. M., De Vet, E., & De Ridder, D. T. D. (2019). The One that I Want: Strong personal preferences render the center-stage nudge redundant. Food Quality and Preference, 78, 103744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103744

- Verplanken, B., & Orbell, S. (2003). Reflections on past behavior: a self‐report index of habit strength 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(6), 1313–1330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01951.x

- Verplanken, B., & Orbell, S. (2022). Attitudes, habits and behavior change. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(73), 327–352. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-011744

- Verplanken, B., & Wood, W. (2006). Interventions to break and create consumer habits. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.25.1.90

- Wilson, A. L., Buckley, E., Buckley, J. D., & Bogomolova, S. (2016). Nudging healthier food and beverage choices through salience and priming. Evidence from a systematic review. Food Quality and Preference, 51, 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.02.009

- Yang, B., & Mattila, A. S. (2020). Chef recommended” or “most popular”? Cultural differences in customer preference for recommendation labels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 86, 102390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102390