Abstract

Background

Stress is associated with obesity through several mechanisms, including coping methods used in stressful situations. However, long-term prospective studies investigating stress-induced eating and drinking in parallel and their relationships with weight are scarce.

Purpose

We examined the prevalence of stress-induced eating and drinking and their associations with body mass index (BMI) among women and men during a 30-year follow-up, as well as BMI trajectories from early adulthood to middle age.

Methods

Participants of a Finnish cohort study were followed by questionnaires at the ages of 22 (N = 1656), 32 (N = 1471), 42 (N = 1334), and 52 (N = 1160). Their coping methods were evaluated by asking how common it was for them to act in certain ways when they encountered stressful situations. We used linear regression analysis to examine the associations between coping methods and BMI, and latent growth models to analyze the BMI trajectories.

Results

The prevalence of stress-induced eating was higher among women than men throughout the follow-up, whereas stress-induced drinking was more common among men at 22 and 32 years of age. Stress-induced eating was associated with higher BMI at all ages among women, and from the age of 32 among men. Eating as a persistent coping method over the life course was associated with a higher and faster growth rate of BMI trajectories. Stress-induced drinking was associated with higher BMI in middle age, and with a faster growth of BMI among men.

Conclusions

Effective, appropriate stress management may be one essential factor in preventing weight gain in the adult population.

Introduction

Today, people in Western countries live in society that is highly obesogenic and highly stressful, both conditions that substantially increase the world’s disease burden. Although obesity may lead to stress due to mechanisms such as the high stigmatization of obesity in Western countries (Major et al., Citation2012; Schvey et al., Citation2014), considerable evidence also shows that increased stress may lead to weight gain (Block et al., Citation2009; Wardle et al., Citation2011). Stress may exert its influence on weight through different kinds of cognitive, behavioral, physiological, and hormonal mechanisms, including the coping methods people use to deal with everyday stress (Tomiyama, Citation2019). Therefore, it has been suggested that stress is one of the many factors contributing to the obesity of the population, making knowledge of the coping methods that people use in stressful situations, especially those involving eating and drinking, essential for preventing obesity.

Theoretically, stress arises in the interaction between an individual and the environment when the person appraises that the demands of the environment exceed his or her resources and endanger his or her well-being (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). It has been suggested that stress should be considered as part of a wider topic, the emotions: while the term stress usually refers to negative affective reactions, the term emotion refers to both positive and negative affective states (Gross, Citation2014; Lazarus, Citation1993). Both food and alcohol may have stress-relieving effects, at least in the short-term, and can therefore be used to cope with stress (Adam & Epel, Citation2007; Sher & Grekin, Citation2007). Coping refers to the cognitive and behavioral efforts made in situations perceived as stressful, and it can be divided into problem-focused and emotion-focused coping (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), the latter referring to the regulation of the emotional response to the situation. Using eating, drinking, smoking, or drugs to regulate one’s emotional responses is one of the 67 items on Lazarus and Folkman’s Ways of coping scale. Eating and drinking also appear in Gross’ process model of emotion regulation (Gross, Citation2014), which postulates that alcohol, drugs and food may be used to modify emotional experience late in the emotional regulation process, in the response modulation phase, after the emotional responses have already occurred.

The literature on emotional eating, i.e. the susceptibility to eating in response to negative emotions (Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1957) is extensive. Stress-induced eating is one part of this phenomenon. While severe stress often leads to decreased appetite, moderate stress and negative emotions can result in increased appetite and eating, as found in several meta-analyses (Cardi et al., Citation2015; Evers et al., Citation2018; Hill et al., Citation2022) as well as in theoretical and empirical studies (Adam & Epel, Citation2007; Macht, Citation2008; Richardson et al., Citation2015). Specifically, stress has been found to be associated with an increased consumption of unhealthy foods and decreased consumption of healthy foods (Hill et al., Citation2022). The association between negative emotions and eating has been observed to be stronger in certain groups, such as restrained and binge eaters (Cardi et al., Citation2015). The prevalence of emotional eating among women tends to be higher than that among men (De Lauzon et al., Citation2004; Konttinen et al., Citation2010; Lluch et al., Citation2000), which raises the question of whether men, who generally consume more alcohol than women (World Health Organization, Citation2019), would be more likely to use alcohol than food to relieve stress.

Due to the relaxing effects of alcohol, stress may also have the effect of increasing alcohol use among some people. Cox and Klinger’s Motivational Model of Alcohol Use (Cox & Klinger, Citation1988) identified the regulation of internal states (including the experience of stress) and the achievement of social outcomes two motives that guide alcohol use. Several more recent studies have also confirmed the connection between higher levels of stress and heavier alcohol use (Cooper et al., Citation2016; Park et al., Citation2004; Temmen & Crockett, Citation2020). The results regarding gender differences in stress-induced alcohol use are less clear than those related to stress-induced eating. According to some studies, men more often report using alcohol to deal with stress than women (Corbin et al., Citation2013; Dawson et al., Citation2005; Wang et al., Citation2009). However, a study by Patrick et al. (Patrick et al., Citation2011) found that women used alcohol to avoid problems more often than men.

The tendency to use food or alcohol to cope with stress can affect weight. Several cross-sectional studies have shown that emotional eating is associated with higher body mass index (BMI) (Konttinen et al., Citation2010; Péneau et al., Citation2013; Van Strien et al., Citation2009), and some longitudinal studies have linked it to a rise in BMI (Benard et al., Citation2018; Koenders & van Strien, Citation2011; van Strien et al., Citation2016), the association appearing to be similar in different age groups (Konttinen et al., Citation2019). These results are in line with evidence that emotional eating often leads to an increased intake of energy-dense foods in particular (Macht, Citation2008; Oliver et al., Citation2000). The effects of stress-induced alcohol use on BMI have rarely been studied. However, alcohol use in general seems to have a complex relationship with BMI: moderate drinking appears to be unrelated to BMI, whereas drinking large amounts of alcohol seems to be associated with obesity [for a review, see: 37, 38]. The association between heavier alcohol use and BMI often appears to be stronger among men than women (French et al., Citation2010; Sayon-Orea et al., Citation2011) and may also vary with age: Alcácera et al. found an association between heavier alcohol use and BMI among older participants (aged over 39), but not among younger participants (Alcacéra et al., Citation2008).

Laitinen et. al investigated the association between BMI and stress-induced eating and drinking among 38-year-old Finns, and found that stress-induced eating and drinking were related to higher BMI, especially among women (Laitinen et al., Citation2002). However, in their study, stress-related eating and drinking were combined into the same variable, which prevented comparisons of the two coping methods.

In this study, we examined stress-induced eating and drinking among women and men of a Finnish prospective cohort at four different ages (22, 32, 42 and 52 years). Examining these two coping-methods in parallel, and their associations with BMI and its trajectories in the same cohort over 30 years of follow-up provided a new viewpoint in the study of stress and weight. Our three research questions were as follows:

How common are stress-induced eating and drinking among women and men at different ages, and are men more inclined to use alcohol and women to use food to regulate stress?

Are stress-induced eating and drinking related to BMI among women and men at different ages?

Do stress-induced eating and drinking during adulthood affect BMI trajectories from young adulthood to middle age and are there gender differences?

Based on the literature presented above, we assumed that stress-induced eating would be more common among women. We also assumed that stress-induced eating would be associated with higher BMI both cross-sectionally and in the long term among both women and men. In the case of stress-induced drinking, however, the literature does not enable us to make specific hypotheses.

Methods

Participants

The study was a part of the Stress, Development and Mental Health (TAM) project (Berg et al., Citation2021). Its population included all Finnish-speaking ninth-grade pupils (N = 2269) who attended comprehensive school in 1983 in Tampere, in southern Finland. In 1983, 2194 pupils (response rate: 96.7%), with a mean age of 15.9 (SD 0.3 years), completed a questionnaire at school. The 1983 baseline (N = 2194) participants were followed up by postal questionnaires at the of ages 22 (N = 1656, 75.5%), 32 (N = 1471, 67.0%), 42 (N = 1334, 60.8%) and 52 (N = 1160, 52.9%). In the present study we only used data on participants who took part in at least one of the follow-ups between the ages of 22 and 52 (N = 1955).

Measures

Stress-induced eating and drinking

The questions measuring stress-induced eating and drinking were part of the section that measured coping with stressful situations. The respondents were asked to recall any recent unspecified adversities that they had encountered and to assess how common it was for them (on a five-point scale from never to very often) to act in certain ways in these situations. The statement measuring stress-induced eating was I comfort myself by eating treats. Stress-induced drinking was measured by a statement I go out for a few beers in the 22- and 32-year follow-up surveys, but was modified to I go out for a few beers or have a couple of drinks in the 42- and 52-year follow-up surveys, to better cover different types of alcohol consumption.

The response scales were dichotomized so that the options never and seldom meant that the specific coping style was not used and often and very often meant that the coping style was used. The middle option I can’t say was coded as a missing response. The proportion of I can’t say answers varied between 5.8% and 8.9% among women and between 7.7% and 10.4% among men in the case of stress-induced eating; and between 2.3% and 6.2% among women and between 5.7% and 9.5% among men in the case of stress-induced drinking. For longitudinal analysis, an aggregate coping variable based on the follow-ups was constructed for both stress-induced eating and stress-induced drinking, indicating the number of follow-ups (0–4) in which the respondent had reported using the coping-style (provided that at least two valid responses had been given).

BMI

BMI was calculated by dividing self-reported weight (kg) by the square of self-reported height (m). For women (N = 34) who reported being pregnant at the time of follow-up, BMI was coded as missing.

Control variables

In the analyses, we controlled for education, measured as a dichotomous variable (graduated/not graduated from high school) for 22-year-olds and as a dichotomous variable (vocational degree or less/college level or higher) from the age of 32 to 52, as well as marital status (married or cohabiting/neither married nor cohabiting). Previous studies have shown both lower education (Berg et al., Citation2021; Pampel et al., Citation2010) and being married or cohabiting (Teachman, Citation2016) to be associated with higher BMI.

For longitudinal analyses, an aggregate control variable was constructed for both education and marital status. The aggregate variable for education indicated whether a participant had reported having ‘college-level or higher’ education in any of the follow-ups at the ages of 32, 42 or 52 (yes/no). The aggregate control variable for marital status measured whether a participant had reported being ‘married or cohabiting’ in most of the follow-ups in which she/he had participated (yes/no).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 27.0. The distributions of the categorical variables were presented as percentages, and for the continuous variables we calculated the means and standard deviations. Gender differences in the categorical variables were tested by the chi-square test and in the continuous variables by one-way ANOVA. The main analyses were performed separately on women and men.

The associations between dichotomous coping methods and BMI were examined using linear regression analysis. Unadjusted and adjusted models (the latter being adjusted by education and marital status) were run at every age phase for both coping methods. We also calculated the regression coefficients’ 95% confidence intervals. Gender differences in the effects of the coping methods on BMI were analyzed using gender x coping method interaction terms in the total sample analyses. The associations between BMI and coping methods were also calculated using one-way ANOVA (see Appendix Table A), showing BMI means, standard deviations, and effect sizes.

We used latent growth models (LGM) to determine the longitudinal associations between coping styles and BMI. Latent growth modelling can be used in longitudinal analysis to examine changes in variables over time, predictors of change, and the differences in trajectories between groups, by modelling the growth curve by means of latent variables (Preacher et al., Citation2008). Regarding model fit, a quadratic model outperformed the model with only a linear latent growth factor. The model fit statistics for the quadratic model were Chi-Square = 2.84, df = 4, p = 0.5846, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.002, RMSEA < 0.001. In the model, one residual term (residual variance at the age of 52) was fixed at zero. In the growth curve analyses, time was centered at the mid-point of the follow-up, when participants were aged 37, thus positioning the latent intercept factors of the curves at this age. BMI trajectories were then predicted by the aggregate coping variable that indicated the number of times the respondent had reported having the specific coping style at follow-up (0–4). The gender differences in the effects of coping styles on the latent factors of the BMI trajectories were tested using the Chi-square test on a model in which the specific regression coefficient was constrained to be equal between the genders and a model in which it was freely estimated for women and men.

Results

Women had higher levels of stress-induced eating than men at every age (). For example, at the age of 22, 47.9% of women reported stress-induced eating, when the corresponding percentage for men was 15.3%. Men had more stress-induced drinking than women at the measurement points when they were 22 and 32, but at the later age phases, gender differences were no longer statistically significant. Among men, stress-induced drinking was a more common coping style than stress-induced eating, throughout the follow-up. For example, at the age of 22, 28.6% of men reported having stress-induced drinking and 18.8% stress-induced eating. In women, the situation was the opposite: the percentages at the age of 22 were 15.3% and 47.9%, respectively. Mean BMI increased steadily with age, exceeding the limit of overweight among men at the age of 32 and among women at 42. Just over two-thirds of the women and half of the men had college-level education or higher at the 32, 42 or 52-year follow-ups, and the majority of both women and men were married or cohabiting in most of the follow-ups.

Table 1. Distributions of study variables.

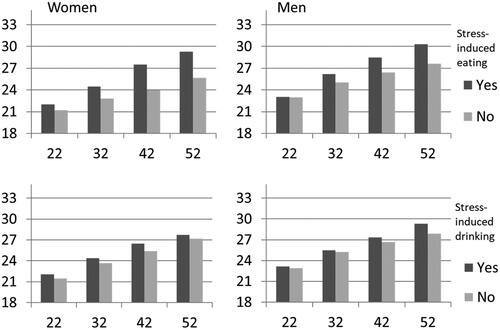

shows the results of the unadjusted and adjusted linear regression models predicting BMI by stress-induced eating and drinking. The occurrence of stress-induced eating was associated with higher BMI at every age phase among women. Among men, stress-induced eating was associated with higher BMI from the age of 32, but the association among 22-year-olds was not statistically significant. The interaction term between gender and stress-induced eating was statistically significant at the ages of 22 and 32 in the adjusted models, suggesting that the associations between stress-induced eating and BMI were stronger among women up to the age phase of 32. Stress-induced drinking, in turn, was associated with higher BMI among women at the age of 42 and among men at 52, in both the unadjusted and adjusted models. Stress-induced drinking was also associated with BMI among 22-year-old women in the unadjusted model, but this association disappeared after the model was adjusted for education and marital status. (). illustrates the BMI means by stress-induced eating and drinking. Among women aged 42 and 52, the mean difference in BMI was up to three units among those who had and those who did not have stress-induced eating (; Appendix Table A).

Figure 1. BMI means by use of stress-induced eating and drinking among women and men at different ages.

Table 2. BMI at ages 22, 32, 42 and 52 by stress-induced eating and stress-induced drinking among women and men. Linear Regression.

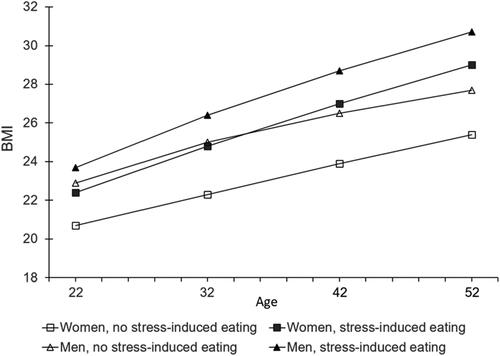

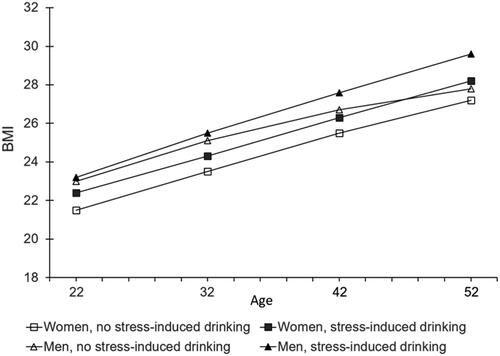

shows the results of the latent growth models of coping styles predicting BMI trajectories. The continuous aggregate variable for stress-induced eating had a positive and significant effect on both the intercept and slope factors of BMI among both women and men, meaning that the growth curve for BMI went on a higher level and grew faster according to the number of follow-ups at which the respondent had reported having stress-induced eating during the research period (). In the case of stress-induced drinking, the aggregate coping variable had a positive effect on the BMI slope factor in men, meaning that men experienced a greater increase in BMI according to the number of follow-ups at which the respondent had reported having stress-related drinking. For women, we found no significant longitudinal associations between stress-induced drinking and BMI growth curves. and illustrate the BMI growth curves for women and men with and without the coping method during the life course.

Figure 2. BMI trajectories predicted by number of follow-ups (0–4) in which stress-induced eating was reported. No stress-induced eating = stress-induced eating reported in none of the follow-ups; stress-induced eating = stress-induced eating reported in three of the follow-ups.

Figure 3. BMI trajectories predicted by the number of follow-ups (0–4) in which stress-induced drinking was reported. No stress-induced drinking = stress-induced drinking was reported in none of the follow-ups; stress-induced drinking = stress-induced drinking was reported in three of the follow-ups.

Table 3. Latent growth factors of BMI trajectories (age 22–52) predicted by number of follow-ups (0–4) in which stress-induced eating or drinking was reported in Latent Growth Models.

Discussion

The present study examined the prevalence of two coping methods, stress-induced eating and drinking, among women and men, the associations of these coping methods with BMI at different ages and with the development of BMI during the life course. In the case of stress-induced eating, the results were in line with our hypotheses. Stress-induced eating was more common among women than men from early adulthood to middle age, and was related to higher and more rapidly growing BMI among both women and men over the life course. Stress-induced drinking, in turn, was more common among men than women up to the age of 32, after which the gender difference diminished. Stress-induced alcohol use was associated with higher BMI at certain ages, and among men with a faster growth of BMI over the life course.

Among women, eating was a common coping method, with 41–55% of them reporting stress-induced eating throughout the follow-up. The fact that women are more engaged in emotional eating than men is also widely reported in the previous literature (Konttinen et al., Citation2010; Lluch et al., Citation2000; De Lauzon et al., Citation2004), and our study found the gender difference to be stable throughout adulthood. The reasons why women are more vulnerable to emotional eating are not completely clear, but one reason could be women’s higher engagement in dieting (Wardle et al., Citation2011), which has been shown to easily lead to emotional eating when encountering stress, mainly due to the loss of feelings of hunger and satiety (Evers et al., Citation2018; Van Strien, Citation2018; Herman & Polivy, Citation1984). The gender difference in self-reported emotional eating could also be explained by cultural and measurement-related factors: emotional eating has traditionally been considered a female issue (Nguyen-Rodriguez et al., Citation2009), in which case men may have under-reported it, especially when the formulation of the question measuring stress-induced eating (I comfort myself by eating treats) may have had connotations generally held as feminine. In line with the previous literature, the association between stress-induced eating and higher BMI was evident among both women and men (Konttinen et al., Citation2010; Péneau et al., Citation2013; Koenders & van Strien, Citation2011; van Strien et al., Citation2016; Benard et al., Citation2018; Frayn & Knäuper, Citation2018), which is a logical result also in the light of the fact that stress-induced eating tends to focus on unhealthy and energy-dense foods (Hill et al., Citation2022). The only exceptions were 22-year-old men, among whom the association was not statistically significant. There was also an interaction between stress-induced eating and gender at the ages of 22 and 32, indicating that in young adulthood, stress-induced eating is more strongly associated with BMI among women than men. This could be related to women’s lower metabolic rate and greater ability to store fat (Power & Schulkin, Citation2008), possibly making the effects of stress-induced eating on BMI appear earlier in women. More importantly, our study showed that stress-induced eating as a long-term coping method is associated with a faster growth of BMI, indicating that embracing stress-induced eating as a persistent coping method may be a risk factor for accelerating weight gain. This effect was evident among both women and men.

The results regarding stress-induced drinking were more complex than those regarding stress-induced eating. Stress-induced drinking was quite uncommon among women, especially compared to stress-induced eating. For men, the situation was the opposite, as men seemed to be more inclined to use alcohol than food to relieve stress during the life course. Interestingly, young men reported more stress-induced drinking than women up to the age of 32, after which the difference disappeared. This might be due to the social gender roles in parenting: it has been shown that the effect of parenthood on alcohol use is stronger among women than men (Christie-Mizell & Peralta, Citation2009; Windle & Windle, Citation2018). Moreover, the results may reflect the societal change in recent decades where the gender differences in alcohol use have generally narrowed (Erol & Karpyak, Citation2015; Grucza et al., Citation2018). As for the associations between stress-induced drinking and BMI, the association was only significant in middle age: among women at the age of 42 and men at the age of 52. This is in line with a Spanish study by Alcacéra et al. which found that alcohol use in general was associated with BMI in middle age, but not among young adults (Alcacéra et al., Citation2008). The long-term effects of stress-induced drinking on weight gain were seen among men but not women: the more often the men reported stress-induced drinking, the faster was the growth of their BMI. The effect occurring only among men might be explained by the fact that men typically drink higher doses of alcohol than women (World Health Organization, Citation2019), as the amount of alcohol consumed has been assessed to be a particularly relevant factor in explaining the effects of alcohol use on weight gain (Traversy & Chaput, Citation2015; Sayon-Orea et al., Citation2011), and that in Finland men tend to drink beer (Härkönen et al., Citation2017) which is an energy-rich drink (Yeomans, Citation2010).

According to Gross’ process model of emotion regulation, food and alcohol can be used as coping methods in stressful situations at the end of the emotion regulation process, to regulate the emotional response that has already arisen (Gross, Citation2014). Several studies have supported the idea of the effects of stress or negative emotions on increased eating (Hill et al., Citation2022; Evers et al., Citation2018; Cardi et al., Citation2015) and drinking (Cooper et al., Citation2016; Temmen & Crockett, Citation2020; Park et al., Citation2004). The regulation of stress by eating and drinking was reported in our study throughout the life course among both women and men, and our study supports the idea that using stress-induced eating and drinking as coping mechanisms could be one of the many factors explaining the complex effects of stress on the development of obesity. Previously, Laitinen et al. found stress-induced eating and drinking, measured as a composite variable, to be associated with higher BMI (Laitinen et al., Citation2002). Our more detailed analysis, however, suggests that stress-induced eating affects BMI in a more consistent way than stress-induced drinking. Therefore, it is more appropriate to consider these coping methods as separate constructs, although studying them in parallel seems especially important when examining gender differences. The topic has been rarely studied to date, and it is important that our results will be further replicated in future studies.

Our data and study design offered several strengths for this research. The study was based on prospective longitudinal data with a relatively good response rate at each follow-up. Assessing stress-induced eating and drinking as parallel coping methods, as well as examining their associations with BMI and the gender differences in these phenomena over a 30-year follow-up offered a new perspective for research on coping with stress. Furthermore, cross-sectional and longitudinal examination of the associations between stress-induced eating and drinking and BMI provided novel insights into the effects of coping with stress on weight and its development. However, the study also had some limitations. The complex behavioral patterns of using food and alcohol in the regulation of negative emotions were assessed with self-reported single-item measures. Also, the statement measuring stress-induced drinking was modified into a different form from the age 42 follow-up onwards to better reflect different types of alcohol consumption. In general, assessing both coping methods by using several items at each follow-up would have strengthen our research. It is also noteworthy that there is an ongoing academic discussion on the ability of self-report scales to assess stress- or emotion-induced eating with mixed evidence from different experimental studies (for more details, see e.g. 60–62). However, at the same time, the use of brief self-report measures enabled us to assess stress-induced eating and drinking several times over the three-decade study period among a large number of participants. Another limitation is related to BMI as a measurement tool: BMI does not take into account individual differences such as muscle mass. These different limitations are thus important to keep in mind when interpreting our results.

The results of our study, conducted in the general population, suggest that the use of eating and drinking to regulate stress occurs throughout adulthood and that the adoption of these coping methods, especially stress-induced eating, seem to be associated with weight and, importantly, with higher weight gain over the life course. The effects of stress-induced eating and drinking on BMI appear to be long-term, cumulative processes, indicating the importance of trying to influence these processes at an early stage. Our results, therefore, could provide potentially fruitful viewpoints for the development of tailored interventions to prevent obesity. Effective and appropriate stress management may be an essential factor in preventing weight gain in the adult population.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tampere University Hospital and the Institutional review board of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Ethics approval was obtained for each data collection phase of the study project. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants were informed of the content and purpose of the study.

Disclosure statement

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behaviour, 91(4), 449–458.

- Alcacéra, M. A., Marques-Lopes, I., Fajo-Pascual, M., Foncillas, J. P., Carmona-Torre, F., & Martinez-Gonzalez, M. A. (2008). Alcoholic beverage preference and dietary pattern in Spanish university graduates: The SUN cohort study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 62(10), 1178–1186. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602833

- Benard, M., Bellisle, F., Etile, F., Reach, G., Kesse-Guyot, E., Hercberg, S., & Péneau, S. (2018). Impulsivity and consideration of future consequences as moderators of the association between emotional eating and body weight status. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15(1), 81–84.

- Berg, N., Kiviruusu, O., Grundström, J., Huurre, T., & Marttunen, M. (2021). Stress, development and mental health study, the follow-up study of Finnish TAM cohort from adolescence to midlife: Cohort profile. BMJ Open, 11(12), e046654.

- Block, J. P., He, Y., Zaslavsky, A. M., Ding, L., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2009). Psychosocial stress and change in weight among US adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp104

- Cardi, V., Leppanen, J., & Treasure, J. (2015). The effects of negative and positive mood induction on eating behaviour: A meta-analysis of laboratory studies in the healthy population and eating and weight disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 57, 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.08.011

- Christie-Mizell, C. A., & Peralta, R. L. (2009). The gender gap in alcohol consumption during late adolescence and young adulthood: gendered attitudes and adult roles. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(4), 410–426.

- Cooper, M. L., Kuntsche, E., Levitt, A., Barber, L. L., & Wolf, S. (2016). Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco.

- Corbin, W. R., Farmer, N. M., & Nolen-Hoekesma, S. (2013). Relations among stress, coping strategies, coping motives, alcohol consumption and related problems: A mediated moderation model. Addictive Behaviors. 38(4), 1912–1919.

- Cox, W. M., & Klinger, E. (1988). A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(2), 168.

- Dawson, D. A., Grant, B. F., & Ruan, W. J. (2005). The association between stress and drinking: Modifying effects of gender and vulnerability. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 40(5), 453–460.

- De Lauzon, B., Romon, M., Deschamps, V., et al. (2004). The Fleurbaix Laventie Ville Sante (FLVS) study group: The three-factor eating questionnaire-R18 is able to distinguish among different eating patterns in a general population. Journal of Nutrition. 2380(134), 2004–2372.

- Erol, A., & Karpyak, V. M. (2015). Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 156, 1–13.

- Evers, C., Dingemans, A., Junghans, A. F., & Boevé, A. (2018). Feeling bad or feeling good, does emotion affect your consumption of food? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 92, 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.028

- Frayn, M., & Knäuper, B. (2018). Emotional eating and weight in adults: A review. Current Psychology, 37(4), 924–933.

- French, M. T., Norton, E. C., Fang, H., & Maclean, J. C. (2010). Alcohol consumption and body weight. Health Economics, 19(7), 814–832.

- Gross, J. J. (2014). Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations.

- Grucza, R. A., Sher, K. J., Kerr, W. C., et al. (2018). Trends in adult alcohol use and binge drinking in the early 21st-century United States: A meta-analysis of 6 National Survey Series. Alcoholism: clinical and Experimental Research, 42(10), 1939–1950.

- Härkönen, J., Savonen, J., Virtala, E., & Mäkelä, P. (2017). Suomalaisten alkoholinkäyttötavat 1968–2016: Juomatapatutkimusten tuloksia.

- Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (1984). A boundary model for the regulation of eating. Research publications – Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease, 62, 141–156.

- Hill, D., Conner, M., Clancy, F., Moss, R., Wilding, S., Bristow, M., & O’Connor, D. B. (2022). Stress and eating behaviours in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 16(2), 280–304.

- Kaplan, H. I., & Kaplan, H. S. (1957). The psychosomatic concept of obesity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease.

- Koenders, P. G., & van Strien, T. (2011). Emotional eating, rather than lifestyle behavior, drives weight gain in a prospective study in 1562 employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53(11), 1287–1293.

- Konttinen, H., Männistö, S., Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S., Silventoinen, K., & Haukkala, A. (2010). Emotional eating, depressive symptoms and self-reported food consumption. A population-based study. Appetite, 54(3), 473–479.

- Konttinen, H., Silventoinen, K., Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S., Männistö, S., & Haukkala, A. (2010). Emotional eating and physical activity self-efficacy as pathways in the association between depressive symptoms and adiposity indicators. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 92(5), 1031–1039. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.29732

- Konttinen, H., Van Strien, T., Männistö, S., Jousilahti, P., & Haukkala, A. (2019). Depression, emotional eating and long-term weight changes: A population-based prospective study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 16(1), 1–11.

- Laitinen, J., Ek, E., & Sovio, U. (2002). Stress-related eating and drinking behavior and body mass index and predictors of this behavior. Preventive Medicine, 34(1), 29–39.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1993). From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology, 44, 1–21.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company.

- Lluch, A., Herbeth, B., Mejean, L., & Siest, G. (2000). Dietary intakes, eating style and overweight in the Stanislas Family Study. International Journal of Obesity, 24(11), 1493–1499.

- Macht, M. (2008). How emotions affect eating: A five-way model. Appetite, 50(1), 1–11.

- Major, B., Eliezer, D., & Rieck, H. (2012). The psychological weight of weight stigma. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(6), 651–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611434400

- Nguyen-Rodriguez, S. T., Unger, J. B., & Spruijt-Metz, D. (2009). Psychological determinants of emotional eating in adolescence. Eating Disorders, 17(3), 211–224.

- Oliver, G., Wardle, J., & Gibson, E. L. (2000). Stress and food choice: A laboratory study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(6), 853–865.

- Pampel, F. C., Krueger, P. M., & Denney, J. T. (2010). Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 349–370.

- Park, C. L., Armeli, S., & Tennen, H. (2004). The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 65(1), 126–135.

- Patrick, M. E., Schulenberg, J. E., O’malley, P. M., Johnston, L. D., & Bachman, J. G. (2011). Adolescents’ reported reasons for alcohol and marijuana use as predictors of substance use and problems in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(1), 106–116.

- Péneau, S., Menard, E., Mejean, C., Bellisle, F., & Hercberg, S. (2013). Sex and dieting modify the association between emotional eating and weight status. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 97(6), 1307–1313.

- Power, M. L., & Schulkin, J. (2008). Sex differences in fat storage, fat metabolism, and the health risks from obesity: Possible evolutionary origins. The British Journal of Nutrition, 99(5), 931–940. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114507853347

- Preacher, K. J., Wichman, A. L., MacCallum, R. C., & Briggs, N. E. (2008). Latent growth curve modeling. Sage.

- Richardson, A. S., Arsenault, J. E., Cates, S. C., & Muth, M. K. (2015). Perceived stress, unhealthy eating behaviors, and severe obesity in low-income women. Nutrition Journal, 14(1), 122.

- Sayon-Orea, C., Martinez-Gonzalez, M. A., & Bes-Rastrollo, M. (2011). Alcohol consumption and body weight: A systematic review. Nutrition Reviews, 69(8), 419–431.

- Schvey, N. A., Puhl, R. M., & Brownell, K. D. (2014). The stress of stigma: Exploring the effect of weight stigma on cortisol reactivity. Psychosomatic Medicine, 76(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000031

- Sher, K. J., & Grekin, E. R. (2007). Alcohol and affect regulation.

- Teachman, J. (2016). Body weight, marital status, and changes in marital status. Journal of Family Issues, 37(1), 74–96.

- Temmen, C. D., & Crockett, L. J. (2020). Relations of stress and drinking motives to young adult alcohol misuse: Variations by gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(4), 907–920.

- Tomiyama, A. J. (2019). Stress and obesity. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 703–718.

- Traversy, G., & Chaput, J. (2015). Alcohol consumption and obesity: An update. Current Obesity Reports, 4(1), 122–130.

- Van Strien, T. (2018). Causes of emotional eating and matched treatment of obesity. Current Diabetes Reports, 18(6), 35.

- Van Strien, T., Herman, C. P., & Verheijden, M. W. (2009). Eating style, overeating, and overweight in a representative Dutch sample. Does external eating play a role? Appetite, 52(2), 380–387.

- van Strien, T., Konttinen, H., Homberg, J. R., Engels, R. C., & Winkens, L. H. (2016). Emotional eating as a mediator between depression and weight gain. Appetite, 100, 216–224.

- Wang, J., Keown, L., Patten, S. B., et al. (2009). A population-based study on ways of dealing with daily stress: Comparisons among individuals with mental disorders, with long-term general medical conditions and healthy people. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(8), 666–674.

- Wardle, J., Chida, Y., Gibson, E. L., Whitaker, K. L., & Steptoe, A. (2011). Stress and adiposity: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 19(4), 771–778. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2010.241

- Windle, M., & Windle, R. C. (2018). Sex differences in peer selection and socialization for alcohol use from adolescence to young adulthood and the influence of marital and parental status. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(12), 2394–2402.

- World Health Organization. (2019). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization.

- Yeomans, M. R. (2010). Alcohol, appetite and energy balance: Is alcohol intake a risk factor for obesity?. Physiology & Behavior, 100(1), 82–89.