Abstract

Objective

Receiving a diagnosis of premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) can be an emotional and distressing experience for women. The aim of this meta-synthesis was to examine women’s experiences of POI both before and after diagnosis to provide new understandings of those experiences.

Design

A systematic review of ten studies examining women’s experiences of POI.

Results

Using thematic synthesis, three analytical themes were identified, demonstrating the complexity of experiences of women diagnosed with POI: ‘What is happening to me?’, ‘Who am I?’ and ‘Who can help me?’. Women experience profound changes and losses associated with their identity that they must adjust to. Women also experience an incongruence between their identity as a young woman and that of a menopausal woman. Difficulty was also experienced accessing support pre-and post-diagnosis of POI, which could hinder coping with and adjustment to the diagnosis.

Conclusion

Women require adequate access to support following diagnosis of POI. Further training should be provided to health care professionals not only on POI but including the importance of psychological support for women with POI and the resources available to provide the much needed emotional and social support.

Introduction

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is menopause that occurs before the age of 40 years old. Other terms such as premature ovarian failure (POF), premature menopause (PM), or early menopause (EM) are synonymous and often used interchangeably with POI in the literature, however, the preferred term is POI (Torrealday et al., Citation2017).This is in contrast to natural menopause (NM), which can occur around the ages of 45–54 (Nosek et al., Citation2012). POI can be spontaneous or medically induced (MI), such as by chemotherapy (Shuster et al., Citation2010). It is a long-term incurable condition that causes infertility, infrequent menstruation, menopausal symptoms, oestrogen deficiency, and other general health concerns (Rudnicka et al., Citation2018; Sterling & Nelson, Citation2011). Symptoms of POI can include hot flushes, night sweats, mood changes, memory problems, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and low libido (Hamoda & British Menopause Society and Women’s Health Concern, Citation2017; Nelson, Citation2009). The risk of POI is approximately 1–3%, however, it is also related with familiar occurrence in about 15% of cases, suggesting a genetic aetiological background (Franić-Ivanišević et al., Citation2016).

Women report difficulty in receiving a timely diagnosis of POI and targeted treatment, and POI is still underdiagnosed and undertreated (Newson & Lewis, Citation2018). It is not uncommon for a diagnosis to be delayed due to a combination of interactions with healthcare professionals (HCPs) and the emotional toll of seeking a diagnosis (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Newson & Lewis, Citation2018). Often, HCPs lack confidence or understanding of POI, perceiving the woman experiencing POI symptoms to be too young to be going through the menopause (Newson & Lewis, Citation2018; Singer, Citation2012).

Receiving a diagnosis of POI can be an emotional and distressing experience, with women reporting higher negative feelings such as despair, anxiety, isolation, and depression, as well a negative impact on self-image and confidence (Li et al., Citation2020). This distress can be further intensified when the cause of POI cannot be identified (Singer, Citation2012). As POI can affect fertility, there can be additional distress. Women who are unable to conceive, can face a disruption in their pursuit of a life goal to have children, and many women find it difficult to accept their loss of fertility (Davis et al., Citation2010; Fraison et al., Citation2019; Wallach & Menning, Citation1980). Overall, POI can be viewed as a life-altering diagnosis that affects all aspects of a woman’s life: physical, emotional, and spiritual (Sterling & Nelson, Citation2011).

Many women with POI report experiencing severe emotional distress at the point of diagnosis and indicate wanting more guidance on how to cope with POI and to be able to access supportive counselling. However, psychological support provided to women can be lacking (Groff et al., Citation2005; Kanj et al., Citation2018; Newson & Lewis, Citation2018). The European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) recommends that treatment for POI should incorporate also psychological support (Webber et al., Citation2016). Similarly, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends referring women with POI to HCPs who have the relevant experience to help them manage all aspects of physical and psychosocial health related to their condition (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2015). In the United Kingdom (UK) few clinics have the resources to address such best practice and in particular psychological care (Richardson et al., Citation2018).

To date, recent systematic reviews (SRs) have focused on health-related quality-of-life (HrQoL) in women with POI (Li et al., Citation2020; McDonald et al., Citation2022). These reviews have highlighted that that POI can have significant implications for HrQoL (McDonald et al., Citation2022), and that overall HrQoL in women with POI is lower than in individuals with normal ovarian functioning (Li et al., Citation2020). However, Li et al. (Citation2020) excluded qualitative literature in their review, and several relevant, high-quality qualitative studies into women’s experiences of POI have been published and could provide a more in-depth understanding that may be missed within quantitative studies. By focusing on HRQoL, rather than an in-depth interpretation of women’s experiences of POI, relevant qualitative studies on POI (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Orshan et al., Citation2001), as well as unpublished dissertations (Lockley, Citation2012) have been missed from McDonald et al. (Citation2022) review.

Therefore, this SR will aim to address these limitations by answering the following question: ‘What are the experiences of women diagnosed with POI?’.

Methodology

Literature search

The review was registered on the international prospective register of SRs (PROSPERO; ID number CRD42021298065). Searches for studies that investigated women’s experiences of POI were undertaken between December 2021 and July 2022. Five electronic databases were searched: APA PsychInfo, CINAHL Complete, Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE and SCOPUS. Grey literature was found by searching Ethos and Open Access Thesis and Dissertations (OATD). Reference lists of relevant papers were also checked.

The SPIDER framework was used to identify studies for inclusion in the review. Three key concepts structured the search: women, experiences, and premature ovarian insufficiency, and were searched for within the titles, abstracts, keywords, and the main text of the study to increase the likelihood of identifying relevant research. An overview of the search terms is provided in supplementary file 1.

A Boolean search strategy was used, using the following search terms: premature ovarian insufficiency OR premature ovarian failure OR premature menopause OR early menopause AND women* OR woman* AND experience* OR perception* OR view* OR opinion*.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

An overview of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in supplementary file 2. Studies were included if they were original qualitative or mixed methods studies (with qualitative extractable data), published in the English language, and focused on the experiences of women with POI. No age restriction was placed on participants. The year of publication was restricted from 2000 to ensure that the search strategy captured as many recent relevant articles as possible. Screening of the study titles and abstracts against inclusion and exclusion criteria was completed by the main author and the co-author. Relevant studies were retained, and the full text of each study independently screened by both authors. Any differences were managed through discussion between the two authors focusing on the aims of this review.

Classification of studies

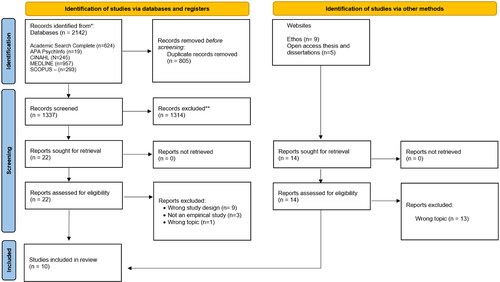

Study selection was recorded on a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Moher et al., Citation2009) (). In total, 2142 articles and 14 dissertations were identified. After eliminating 805 duplicates, the remaining 1337 titles and abstracts were screened, excluding a further 1314. The remaining 22 articles were read in full; ten of these met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Quality assessment checks

The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) was used to appraise the methodological quality of the included studies (CASP, Citation2022). To enhance reliability, the co-author independently appraised the included studies using the same framework. Inter-rater reliability was established using Kappa coefficients (Fleiss & Cohen, Citation1973). The overall kappa score was .82 with the resulting coefficients ranging from .63 to 1 for individual studies.

Characteristics of included studies

The author(s), date of publication, country, aim(s), sampling method, sampling characteristics, data collection, data analysis, and main findings were extracted from the original articles (). A detailed description of the characteristics of studies included in this review can be found in supplementary file 3. Not every study included the age of participants (Boughton, Citation2002; Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009). For the remaining studies, the age of participants ranged from 19 to 61.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity is an integral part of quality research and considers how the positioning of the researchers to the research process influences the collection of data and the subsequent analysis (Mays & Pope, Citation2002). JH is a Trainee Clinical Psychologist and MM is a Chartered Psychologist, both hold a keen interest in Clinical Health Psychology and the complex interplay between physical and mental health. At the time of the review, JH was undertaking an elective placement within a Clinical Health Psychology Service, with a focus on women’s health, at a public general hospital in the West Midlands, UK. Throughout the research process we reflected on our positioning, and any potential biases or assumptions.

Analytic review strategy

Thematic synthesis (TS) was used to integrate the findings from the studies (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). TS provides a set of established methods and techniques for the identification and development of analytical themes in primary research data to generate new interpretative constructs, explanations, or hypotheses that ‘go beyond’ the primary studies (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). TS involves three stages of analysis: stage 1 involves line-by-line coding of the findings of each primary study to develop a bank of codes; stage 2 involves the development of ‘descriptive themes’; stage 3 involves the development of ‘analytical themes’ (see supplementary files 4-6 for screenshots and examples from each stage).

Line-by-line coding was conducted by JH, and the codebook reviewed by MM who independently coded a randomly selected included study. The codes were compared and discrepancies between coders were resolved by discussion. The most salient codes were identified and aggregated into similar concepts, creating new ones when necessary to create a set of descriptive themes which remained close to the original findings of the included studies (Thomas & Harden, 2008). Analytical themes were created by comparing each descriptive theme against the aim of this review (Thomas & Harden, 2008). Conceptual links amongst the descriptive themes were identified by JH using a mind-mapping approach to develop an initial analytical framework. To ensure that the themes captured the relevant issues and encourage a more reflexive analysis of the data, researcher triangulation was used. MM independently reviewed the preliminary themes. Subsequently, a discussion between JH and MM took place during which both authors agreed on the revised themes.

Results

From the analysis, three main themes were identified: ‘What is happening to me?’, ‘Who am I now?’ and ‘Who can help me?’, each with associated subthemes. A summary of each paper’s contribution to the themes is shown in , and how descriptive themes were aggregated into analytical themes are shown in . Additional quotes are provided in supplementary file 7.

Table 2. Main themes, subthemes, and paper contribution.

Table 3. Summary of analytical themes and sub-themes with corresponding descriptive themes used to construct each analytical theme.

‘What is happening to me?’

This main theme describes how women tried to make sense of the symptoms they were experiencing prior to receiving a diagnosis of POI, the emotional response to receiving a diagnosis and how they tried to make sense of this. Two subthemes are discussed: Making sense of the symptoms and Making sense of the diagnosis.

Making sense of the symptoms

Physical symptoms ranged from irregular menstrual cycles, hot flushes, and tiredness to the cognitive or emotional symptoms such as mood swings or changes to their memory. Symptoms could be disruptive and affect day to day life with some women describing it as ‘hell’ (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008, p. 568) and feeling like ‘a werewolf with Alzheimer’s in a full moon!’ (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008, p. 568). However, some women were not able to describe their symptoms, and vagueness to their symptoms could add to the confusion and uncertainty about what they were experiencing (Boughton, Citation2002; Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008).

Four studies (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012) discussed how women tried to make sense of these symptoms and what was happening to them, by drawing on their own knowledge to try and find an explanation. Some women considered the role of stress and life stressors as a possible cause to their menstrual irregularities (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012). For some, the possibility of pregnancy seemed to fit with the irregular menstrual symptoms (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008).

Three studies (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009; Lockley, Citation2012) discussed how women did not consider the menopause due to their age as they were ‘just too young’ (Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009, p. 19) and ‘had associated it with an older age group’ (Lockley, Citation2012, pp. 75–76). In some cases, women put the causes of their symptoms to other health conditions, such as cancer (Lockley, Citation2012).

Making sense of the diagnosis

All studies described the emotional responses to the diagnosis and how women tried to make sense of their diagnosis. The diagnosis was described as a devastating (Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009; Lockley, Citation2012) and a traumatic experience (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Lockley, Citation2012; Orshan et al., Citation2001; Singer, Citation2012). Receiving the diagnosis caused distress, with women expressing feelings of ‘loss, grief, depression’ (Orshan et al., Citation2001, p. 205). Some women also contemplated suicide due to the diagnosis, although this was only identified in one study (Orshan et al., Citation2001).

The diagnosis of POI could be confusing for women, as they did not associate their age with the menopause (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012). Some women also expressed denial (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020). However, for others, a diagnosis provided a sense of relief, as they could now begin ‘piecing together’ the symptoms (Lockley, Citation2012, p. 75). For women who could not describe what they were experiencing, a diagnosis could prove that their symptoms were ‘not all in my head’ (Lockley, Citation2012, p. 84) and that ‘they were not going mad’ (Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009, p. 19).

Some women attempted to make sense of their diagnosis by reflecting on early lifestyle choices. For example, Karen wondered ‘Was it because I smoked a few years ago? Was it because my mother smoked when she was pregnant?’ (Lockley, Citation2012, p. 83). Another woman thought POI was due to ‘[her] erratic use of the contraception pill or excessive alcohol use’ (Singer, Citation2012, p. 103). In other cases, women considered the role of significant events or traumas in their lives as the cause of POI that included bereavement or childhood sexual abuse (Singer, Citation2012). For many women, the cause of POI remained unknown which often ‘impeded their adjustment’ to POI (Singer, Citation2012, p. 103).

For some women, POI was expected due to procedures such as chemotherapy and/or radiation (Boughton, Citation2002; Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009; Johnston-Ataata, Flore & Kokanović, Citation2020; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Singer, Citation2012). Women in this situation therefore ‘had a bit of time to deal with it’ (Johnston-Ataata, Flore & Kokanović, Citation2020, p. 251), though the emotional response to this was still of distress. However, in some cases, women who underwent medical treatment were not informed that it would lead to POI (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020).

Women trying to make sense of and understand their diagnosis, found information tailored to older women going through a NM and many were left unsure about its relevance to them (Lockley, Citation2012, p. 82). It could also be difficult to understand what was happening to them when women often ‘had no knowledge of anyone who had had the same diagnosis’ (Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009, p. 21) and women they knew going through the menopause were older than them. Thus, trying to make sense of the diagnosis could be an isolating, lonely, and confusing experience (Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009).

‘Who am I now?’

This main theme highlights how POI changed a woman’s perceived sense of self and her identity, including how they thought others and society perceived them. Within this theme, two subthemes are discussed: To myself and To others.

To myself

All studies described how a woman’s perceived sense of self and identity changed following diagnosis of POI. Perceptions about the menopause had been influenced by observations of mothers or older female family members and was associated as ‘something that happened to older women’ (Lockley, Citation2012, p. 76). Seven studies (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Orshan et al., Citation2001; Singer, Citation2012) referred to POI making women feel older than they were, and there was an incongruence felt between a woman’s chronological age and her biological age which could be hard to make sense of (Boughton, Citation2002; Moukhah et al., Citation2021).

Femininity and appearance were important, and women were concerned with premature aging and the impact POI was having on their body, appearance, and attractiveness (Lockley, Citation2012; Orshan et al., Citation2001).These changes ‘posed a threat to their identity as a “young” woman’ (Lockley, Citation2012, p. 89) and made their body feel older. Women described that they ‘had become heavier’ (Golezar et al., Citation2020, p. 4), were experiencing hair loss (Boughton, Citation2002; Lockley, Citation2012) and changes to their skin, such as wrinkling or dryness (Lockley, Citation2012), leaving some women feeling aged (Golezar et al., Citation2020), and ‘no longer beautiful’ (Moukhah et al., Citation2021; p. 5).

Where fertility was a significant feature of a woman’s identity and her femininity, there could be a painful shift away from their desired identity of becoming a mother, to grieving for a family that they may never have (Boughton, Citation2002; Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Golezar et al., Citation2020; Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Orshan et al., Citation2001; Singer, Citation2012). This could affect a woman’s mental wellbeing and the loss of fertility could make women feel inferior, leading them to compare themselves against ‘normal’ women (Golezar et al., Citation2020)

There was a sense of loss and a need to redefine or reconstruct their pathway in life and to ‘find another sort of identity, not being a mother’ (Boughton, Citation2002, p. 429) which was experienced by women with spontaneous or MI POI. And yet this adjustment could be difficult and fraught with emotion (Boughton, Citation2002). For women who already had children, it was confirmation that a certain period of her life had ended prematurely, and similarly associated with grief, pain, and difficulty in accepting this change and their womanhood ending (Boughton, Citation2002, p. 429).

To others

All but two studies (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020) considered how women felt they were perceived by others. Boughton (Citation2002) highlighted the negative labels that society placed on menopausal women, such as being ‘the grandmotherly type’ or being ‘older’, ‘obsolete’, ‘sexually unattractive’ and ‘unproductive’. Consequently, women with POI were acutely aware of being labelled similarly (Boughton, Citation2002). This therefore influenced whether they disclosed their diagnosis to others (Orshan et al., Citation2001) and additionally some women were concerned about their ‘menopausal status’ being disclosed (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008, p. 427). Women hid the diagnosis due to fear of stigma, shame and how society viewed menopausal women (Boughton, Citation2002; Golezar et al., Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Singer, Citation2012).

The decision to hide the diagnosis from others could also be influenced by cultural factors (Golezar et al., Citation2020; Singer, Citation2012) possibly for fear of shame or the impact of POI on one’s reputation in their community, particularly where the maternal role and childbearing is important to a woman’s identity, and her standing within her family’s culture and that of wider society; ‘For the first 10 years as a young Indian girl I was told not to tell: ‘If anyone in the community found out it would not be good’. I just wanted to be a normal teenager’ (Singer, Citation2012, p. 104).

Four studies highlighted the perceived value society places fertility upon a woman’s femininity and her role within society (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Johnston-Ataata, Flore & Kokanović, Citation2020; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Orshan et al., Citation2001; Singer, Citation2012). Some women reported being concerned about how POI could be perceived by current or prospective partners where fertility was concerned (Golezar et al., Citation2020; Singer, Citation2012). In some cases, women did not feel able to disclose that they had POI to their current partners, particularly if starting a family had been part of their intended future (Singer, Citation2012). Disclosing fertility difficulties due to POI could also be detrimental in pursuing future relationships, particularly if prospective partners placed an importance on having children. It seemed that a woman’s value could be heavily determined by her ability to have children (Moukhah et al., Citation2021).

Women could find themselves in ‘no woman’s land’ (Lockley, Citation2012, p. 96) following diagnosis as they tried to navigate which social group of women they belonged to, how these different groups would perceive them, and which group would accept them. For example, women with POI sought out older women going through the menopause when it came to seeking support over symptoms such as hot flushes (Johnston-Ataata, Flore & Kokanović, Citation2020; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012). However, in some cases, older menopausal women did not perceive women with POI as their equals when it came to the menopause experience, leaving women with POI feeling rejected (Lockley, Citation2012). It also became difficult to relate to other women their own age and feel part of that social group (Lockley, Citation2012).

‘Who can help me?’

This main theme is concerned with how and from who women sought support to help make sense of the symptoms, or to help them cope with the diagnosis. Two subthemes are discussed: Personal and Professional.

Personal

Six studies discussed who in their personal lives women sought support from (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Golezar et al., Citation2020; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Orshan et al., Citation2001). Overall, women described being accepted and having support from family members and partners in relation to POI (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Orshan et al., Citation2001). Female members of the family, for example mothers, sisters, or aunts provided the emotional support with adjustment to POI as it was more relatable, compared to male relatives who provided more practical support (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Singer, Citation2012). The previous theme highlighted concerns regarding how women felt they could be perceived by their partners. However, some women highlighted that their partners or husbands supported them to adapt to and cope with POI, facilitated hope and even encouragement to persevere with the treatment women received for POI (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012; Moukhah et al., Citation2021): ‘I am most supported by my husband. If he did not help me, I wouldn’t be able to control the situation and control myself. He encourages me to continue my treatment’ (Moukhah et al., Citation2021, p. 6).

Family members did not always know how to support women with POI as ‘they didn’t really know how to go about it’ (Orshan et al., Citation2001, p. 206) or did not necessarily understand the impact POI had on them (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020). Women struggled to access support from friends as they either did not understand the impact of POI or did not have other friends diagnosed with it (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012). One woman reported that friends expressed a ‘lack of interest in her experience of POI’ (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020, p. 18). Additionally, not all women perceived the support of friends and/or family as particularly helpful, especially when sharing feelings about the symptoms and infertility with people who were not experiencing the same struggles (Orshan et al., Citation2001).

Professional

All but one study (Boughton, Citation2002) considered the professional support women sought for POI. Support from HCPs was mixed, with women reporting negative experiences pre-and post-diagnosis of POI (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, & Kokanović, Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Orshan et al., Citation2001; Singer, Citation2012), with some women reporting feeling let down and not being supported by HCPs when they sought help. Women were left feeling delegitimised as they described having their symptoms dismissed by their clinician (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009; Orshan et al., Citation2001), with ‘many women being told they were just too young for menopause’ (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008, p. 570) leaving them ‘with a sense that they were “going insane”’ (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008, p. 570) .

A lack of compassion from their HCPs in the delivery of their diagnosis was voiced by women in six studies (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008; Johnston-Ataata, Flore & Kokanović, Citation2020; Lockley, Citation2012; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Orshan et al., Citation2001; Singer, Citation2012). Some women reported being made to ‘feel like a diagnosis’ (Singer, Citation2012, p. 205) or having their diagnosis delivered in an insensitive manner; ‘Donna vividly recalls the gynaecologist saying, “I’m 95% sure it is menopause and you have as much chance of having another baby as winning Saturday night Tattslotto”’ (Boughton & Halliday, Citation2008, p. 569). Positive interactions with HCPs, such as delivering the diagnosis sensitively, giving women the opportunity to ask questions, giving sufficient information and offering a follow-up appointment were only identified in two studies (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, & Kokanović, Citation2020; Singer, Citation2012).

Women felt that HCPs lacked knowledge about POI and the treatments available, such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009). However, if there was a family history of breast cancer, or previous diagnosis of cancer, or MI POI due to chemotherapy, the treatment options were limited (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović, et al. Citation2020). Many women expressed dissatisfaction about the information they were given to support them to make an informed decision regarding treatment, or sometimes being given their medication and sent away with no further information and having to conduct their own research (Singer, Citation2012). Medication, however, was helpful for some women as it put things ‘back into alignment’ (Lockley, Citation2012, p. 92) and helped with the physical symptoms of POI.

The need to access psychological support was highlighted in three studies (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović, et al. Citation2020; Orshan et al., Citation2001; Singer, Citation2012). Women described feelings of grief for the ‘woman [one] might have been, the loss of the children [one] would have had’ (Singer, Citation2012, p. 105). Psychological support was not always considered or offered by HCPs, was not always available or affordable, or was not tailored towards POI, limiting the scope of psychological support for women (Singer, Citation2012). Women who were able to access psychological support were sometimes dissatisfied and felt that it was not tailored to the emotional impact of POI (Singer, Citation2012).

Support groups allowed women to connect with other ‘fellows in fate’ (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020, p. 10) and many women described searching for such groups (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović, et al. Citation2020; Singer, Citation2012). Support groups allowed women to confide in others, gain validation of their experiences and obtain practical information from other women diagnosed with POI. However, POI support groups could be difficult to come by, with women having to look elsewhere for support (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

This review addressed the question, ‘What are the experiences of women diagnosed with POI?’. Thematic synthesis identified three main themes.

‘What is happening to me?’

Women experienced a range of physical and emotional symptoms, such as hot flushes and irregular menstrual cycles, and changes to memory and mood which are consistent with existing literature (Li et al., Citation2020; McDonald et al., Citation2022). However, this review provides further context into the ways women sought to make sense of what was happening to them (such as using their own knowledge or reflecting on previous life choices) that were not explored in existing SRs (Li et al., Citation2020; McDonald et al., Citation2022).

Women expressed feelings of loss, grief, distress, and depression following diagnosis particularly in the context of lost fertility. The emotional responses are like those reported by Li et al. (Citation2020). However, this view goes further to explore why women were experiencing these emotions and adding further context not discussed by the authors. McDonald et al. (Citation2022) referred to emotional responses, however, no further descriptions of these were given.

Women reaching the age for NM, can make the link between the physical symptoms and changes they are experiencing to the menopause as it is often expected and perceived as a normal part of ageing (Ballard et al., Citation2001). However, in this review, women diagnosed with POI could not necessarily make that connection as they perceived themselves as too young to be menopausal. An exception to this were women who had MI POI and were forewarned that this would be a consequence of the treatment (Johnston-Ataata, Flore, & Kokanović, Citation2020). This review extends our understanding of the different ways women tried to make sense of POI, particularly when there is no known cause and when menopause is not a consideration due to age.

‘Who am I now?’

Menopause was associated with being older, and women with POI found it difficult to comprehend going through the menopause at a younger age, findings that were not highlighted in existing POI SRs (Li et al., Citation2020; McDonald et al., Citation2022) and contrast with existing menopause literature, where women going through NM report being expectant of this (Ballard et al., Citation2009; Hoga et al., Citation2015; Ilankoon et al., Citation2021). Women also described the physical changes to their body due to POI, and the impact upon a woman’s confidence in her appearance. These findings are similar to McDonald et al. (Citation2022) who made reference to a changing body image, such as feeling older, and less confident or feminine. However, the incongruence between biological and chronological age were also not discussed by the authors.

This review further highlighted how fertility was perceived as a significant feature of a woman’s identity and role within society, and fertility difficulties could cause a shift away from the often-desired identity of becoming a mother. Women described a loss of this identity and feeling inferior compared to other women. They also described the additional impact of POI related fertility difficulties on current or prospective relationships, and how women may be perceived by prospective partners and/or wider society. These were not findings discussed by Li et al. (Citation2020) and McDonald et al. (Citation2022). Existing research has found that menopause can be negatively experienced in cultures or communities in which fertility status is highly valued and thus its loss and therefore childbearing ability can significantly affect a woman’s identity (Khademi & Cooke, Citation2003). This review further adds to this understanding of the importance of fertility status and the perception of POI across different cultures, by including studies conducted in both Western and Middle Eastern countries.

Existing research on NM have identified the narrative of women becoming part of a social group when they start to go through the menopause (Edwards et al., Citation2021). However, in this review, women struggled to define which social group there were part of, which has not been discussed in existing reviews (Li et al., Citation2020; McDonald et al., Citation2022). The current review broadens our understanding of how women with POI perceive themselves and their identity following diagnosis with POI, and how society and others may also perceive them.

‘Who can help me?’

Family and partners/husbands provided support to women as they came to terms with the diagnosis and this finding supports the importance of familial support documented in menopause literature, though this was limited to NM (Wong et al., Citation2018; Yazdkhasti et al., Citation2015). Women also discussed difficulties accessing support from people close to them, especially if they did not understand the ramifications of POI, which is consistent with existing literature where menopausal women encountered negative familial interactions, though again this was limited to NM (Dillaway, Citation2008).

Women described negative interactions with HCPs both pre and post diagnosis of POI. Such interactions are consistent in both POI and NM literature, with women describing dissatisfaction, feeling dismissed by their clinician and perceiving them to be lacking in knowledge of POI and treatment options (de Salis et al., Citation2018; Groff et al., Citation2005; McDonald et al., Citation2022). Existing literature has identified that when women have POI, HCPs do not often have a discussion with them regarding a plan of management for the emotional and mental health aspects of POI, and few are referred to sources of emotional support such as a psychologist or support group (Groff et al., Citation2005; Mohamad Ishak et al., Citation2021). This is consistent with the findings of the current review. In lieu of psychological support, women expressed seeking out others with POI for support. Previous NM literature have highlighted the importance of menopausal peers, and the role these peers can play in providing information and sharing experiences (Hoga et al., Citation2015; Refaei et al., Citation2022). Interestingly, the importance of such support was not identified in existing POI reviews (Li et al., Citation2020; McDonald et al., Citation2022), and the current review furthers our understanding of the importance of both psychological and social support for women diagnosed with POI.

Limitations

While the participants of included studies were all women diagnosed with POI, six studies included women with MI POI and women with spontaneous POI, and these may have introduced some differences in experiences (Boughton, Citation2002; Halliday & Boughton, Citation2009; Johnston-Ataata, Flore & Kokanović, Citation2020; Johnston-Ataata, Flore, Kokanović et al., Citation2020; Moukhah et al., Citation2021; Singer, Citation2012). For example, having more time to come to terms with their diagnosis as they were expecting this from the treatment. There may have been differing impacts of POI between women with MI and spontaneous POI that was not apparent in the findings, but the possibility should be considered.

The data analysed is largely limited to studies conducted in Australia (k = 6), therefore it is uncertain whether the current findings are transferable to other countries. Furthermore, all but two studies (Golezar et al., Citation2020; Moukhah et al., Citation2021) in this review were conducted in Westernised countries, with the remaining two conducted in Iran. Thus, caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings of this review which are weighted towards Western perspectives and may not be transferable to other countries.

Clinical implications

Whilst clinical practice guidelines have highlighted the need for women with POI to receive psychological support (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2015; Webber et al., Citation2016), studies have shown that psychological support as part of the multidisciplinary care for POI can be lacking (Davis et al., Citation2010; Kanj et al., Citation2018). The psychological and emotional support needs around POI are of significant importance, and yet under-estimated or not considered by HCPs (Sterling & Nelson, Citation2011). This may be due to HCPs lack of awareness of and experience in POI, and what provision of support is available (Newson & Lewis, Citation2018). Training should be provided to HCPs to raise awareness of POI and the resources that are available to these women. Additionally, further training should be provided to highlight the importance of psychological support for women diagnosed with POI and giving them adequate space and time to discuss POI-related concerns. Allowing for this space, could also provide opportunities for clinicians to further educate women about POI, particularly when a diagnosis is unexpected.

POI is attributed to many types of losses and change for a woman, such as her identity and fertility, as well as physical changes to the body (Davis et al., Citation2010). Such experiences could benefit from psychological support. Third-wave talking therapies, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Hayes et al., Citation2013) and Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) (Gilbert, Citation2010), may be useful therapeutic models to support women with POI, by helping them build on the psychological resources they possess, such as their flexibility in setting goals and their desire to define a purpose in their life (Davis et al., Citation2010; Sterling & Nelson, Citation2011). Both ACT and CFT have been trialled in women experiencing menopause with promising results (Dolatabadi et al., Citation2019; Monfaredi et al., Citation2022) and thus could be considered for POI.

POI can be an isolating experience, particularly if women do not know anyone else living with the condition. Research has highlighted the benefits of support groups in terms of QoL and symptom management for women who are going or have gone through the menopause, which can improve (Sehhatie Shafaie et al., Citation2014; Yazdkhasti et al., Citation2012). Where available, such support groups could be promoted more widely by HCPs as an additional option for further psychological or social support for women diagnosed with POI.

Future research

Women with POI are at increased risk of psychological distress, and yet there are a limited number of studies evaluating the impact of psychological interventions on the mental wellbeing of patients with POI (Rahman & Panay, Citation2021). Further research examining the effectiveness of different psychological interventions, such as ACT or CFT, is necessary to ensure that women are receiving psychological care that considers the impact of POI.

Although the review described the processes in which women coped with POI following a diagnosis, distress and adjustment to POI may change over time. Longitudinal research on how women adjusted to the diagnosis could help further our understanding of the support needed and provided to women with POI.

Finally, research should also consider accessing diverse participant samples to improve the representation of a range of views and experiences and consider the role factors such as culture may have in seeking support for POI and how it is managed and perceived. Menopause literature has identified that cultural influences affect how women perceive and manage their menopausal symptoms (Hall et al., Citation2007). Therefore, cultural perceptions of POI may vary, and warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

This review explored women’s experiences of POI. Three main themes were identified, suggesting that the experiences of women with POI is complex, particularly when the diagnosis is unexpected. Finding or accessing support can be challenging both pre-and post-diagnosis of POI, with some women experiencing negative encounters with HCPs. The findings highlighted that women experience profound changes and losses that they must adjust to, such as a change in fertility, body and appearance, identity, and perceived role in society. It further highlights the importance of appropriate psychological and social support for women with POI.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (721.3 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials. The authors report there are no competing interests to declare

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ballard, K. D., Elston, M. A., & Gabe, J. (2009). Private and public ageing in the UK: The transition through the menopause. Current Sociology, 57(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392108099166

- Ballard, K. D., Kuh, D. J., & Wadsworth, M. E. J. (2001). The role of the menopause in women’s experiences of the ‘change of life. Sociology of Health & Illness, 23(4), 397–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00258

- Boughton, M. A. (2002). Premature menopause: multiple disruptions between the woman’s biological body experience and her lived body. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(5), 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02114.x

- Boughton, M., & Halliday, L. (2008). A challenge to the menopause stereotype: young Australian women’s reflections of ‘being diagnosed’ as menopausal. Health & Social Care in the Community, 16(6), 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00777.x

- CASP (2022). CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [online]. Retrieved October from https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- Davis, M., Ventura, J. L., Wieners, M., Covington, S. N., Vanderhoof, V. H., Ryan, M. E., Koziol, D. E., Popat, V. B., & Nelson, L. M. (2010). The psychosocial transition associated with spontaneous 46,XX primary ovarian insufficiency: Illness uncertainty, stigma, goal flexibility, and purpose in life as factors in emotional health. Fertility and Sterility, 93(7), 2321–2329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.122

- de Salis, I., Owen-Smith, A., Donovan, J. L., & Lawlor, D. A. (2018). Experiencing menopause in the UK: The interrelated narratives of normality, distress, and transformation. Journal of Women & Aging, 30(6), 520–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2018.1396783

- Dillaway, H. E. (2008). Why can’t you control this?" How women’s interactions with intimate partners define menopause and family. Journal of Women & Aging, 20(1-2), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1300/j074v20n01_05

- Dolatabadi, A., Jafari, F., & Zabihi, R. (2019). The effectiveness of group self-compassion focused therapy on flourishing in menopausal women.

- Edwards, A. L., Shaw, P. A., Halton, C. C., Bailey, S. C., Wolf, M. S., Andrews, E. N., & Cartwright, T. (2021). “It just makes me feel a little less alone”: A qualitative exploration of the podcast Menopause: Unmuted on women’s perceptions of menopause. Menopause, 28(12), 1374–1384. https://journals.lww.com/menopausejournal/Fulltext/2021/12000/_It_just_makes_me_feel_a_little_less_alone___a.9.aspx https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001855

- Fleiss, J. L., & Cohen, J. (1973). The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 33(3), 613–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447303300309

- Fraison, E., Crawford, G., Casper, G., Harris, V., & Ledger, W. (2019). Pregnancy following diagnosis of premature ovarian insufficiency: A systematic review. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 39(3), 467–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.04.019

- Franić-Ivanišević, M., Franić, D., Ivović, M., Tančić-Gajić, M., Marina, L., Barac, M., & Vujović, S. (2016). Genetic etiology of primary premature ovarian insufficiency. Acta Clinica Croatica, 55(4), 629–635. https://doi.org/10.20471/acc.2016.55.04.14

- Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Golezar, S., Keshavarz, Z., Ramezani Tehrani, F., & Ebadi, A. (2020). An exploration of factors affecting the quality of life of women with primary ovarian insufficiency: A qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1), 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01029-y

- Groff, A. A., Covington, S. N., Halverson, L. R., Fitzgerald, O. R., Vanderhoof, V., Calis, K., & Nelson, L. M. (2005). Assessing the emotional needs of women with spontaneous premature ovarian failure. Fertility and Sterility, 83(6), 1734–1741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.067

- Hall, L., Callister, L. C., Berry, J. A., & Matsumura, G. (2007). Meanings of menopause: Cultural influences on perception and management of menopause. Journal of Holistic Nursing: Official Journal of the American Holistic Nurses’ Association, 25(2), 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010107299432

- Halliday, L., & Boughton, M. (2009). Premature menopause: Exploring the experience through online communication. Nursing & Health Sciences, 11(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2008.00415.x

- Hamoda, H., & British Menopause Society and Women’s Health Concern (2017). The British Menopause Society and Women’s Health Concern recommendations on the management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Post Reproduct Health, 23(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053369117699358

- Hayes, S. C., Levin, M. E., Plumb-Vilardaga, J., Villatte, J. L., & Pistorello, J. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: Examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav Ther, 44(2), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.002

- Hoga, L., Rodolpho, J., Gonçalves, B., & Quirino, B. (2015). Women’s experience of menopause: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 13(8), 250–337. https://journals.lww.com/jbisrir/Fulltext/2015/13080/Women_s_experience_of_menopause__a_systematic.18.aspx

- Ilankoon, I. M. P. S., Samarasinghe, K., & Elgán, C. (2021). Menopause is a natural stage of aging: A qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health, 21(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01164-6

- Johnston-Ataata, K., Flore, J., & Kokanović, R. (2020). Women’s experiences of diagnosis and treatment of early menopause and premature ovarian insufficiency: A qualitative study. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 38(4-05), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1721463

- Johnston-Ataata, K., Flore, J., Kokanović, R., Hickey, M., Teede, H., Boyle, J. A., & Vincent, A. (2020). My relationships have changed because I’ve changed’: Biographical disruption, personal relationships and the formation of an early menopausal subjectivity. Sociology of Health and Illness, 42(7), 1516–1531. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13143

- Kanj, R. V., Ofei-Tenkorang, N. A., Altaye, M., & Gordon, C. M. (2018). Evaluation and management of primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 31(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2017.07.005

- Khademi, S., & Cooke, M. (2003). Comparing the attitudes of urban and rural Iranian women toward menopause. Maturitas, 46(2), 113–121.

- Li, X. T., Li, P. Y., Liu, Y., Yang, H. S., He, L. Y., Fang, Y. G., Liu, J., Liu, B. Y., & Chaplin, J. E. (2020). Health-related quality-of-life among patients with premature ovarian insufficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Quality of Life Research, 29(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02326-2

- Lockley, G. (2012). Premature menopause – The experiences of women and their partners [dissertation on the Internet]. https://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au/file/a8c47473-a967-41c5-a1bf-b5c353b70f1d/1/Geraldine%20S%20Lockley%20Thesis.pdf

- Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2002). Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320(7226), 50–52.

- McDonald, I. R., Welt, C. K., & Dwyer, A. A. (2022). Health-related quality of life in women with primary ovarian insufficiency: A scoping review of the literature and implications for targeted interventions. Human Reproduction, 37(12), 2817–2830. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deac200

- Mohamad Ishak, N. N., Jamani, N. A., Mohd Arifin, S. R., Abdul Hadi, A., & Abd Aziz, K. H. (2021). Exploring women’s perceptions and experiences of menopause among East Coast Malaysian women. Malaysian Family Physician, 16(1), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.51866/oa1098

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Monfaredi, Z., Malakouti, J., Farvareshi, M., & Mirghafourvand, M. (2022). Effect of acceptance and commitment therapy on mood, sleep quality and quality of life in menopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03768-8

- Moukhah, S., Ghorbani, B., Behboodi-Moghadam, Z., & Zafardoust, S. (2021). Perceptions and experiences of women with premature ovarian insufficiency about sexual health and reproductive health. BMC Womens Health, 21(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01197-5

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, N. (2015, December 2019). Menopause: diagnosis and management [Internet]. NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23

- Nelson L. M. (2009). Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. New Engl J Med, 360(6), 606–614. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp0808697

- Newson, L. R., & Lewis, R. (2018). Premature ovarian insufficiency: Why is it not being diagnosed enough in primary care? The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 68(667), 83. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X694661

- Nosek, M., Kennedy, H. P., & Gudmundsdottir, M. (2012). Distress during the menopause transition: A rich contextual analysis of midlife women’s narratives. SAGE Open, 2(3), 2158244012455178. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244012455178

- Orshan, S. A., Furniss, K. K., Forst, C., & Santoro, N. (2001). The lived experience of premature ovarian failure. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 30(2), 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01536.x

- Rahman, R., & Panay, N. (2021). Diagnosis and management of premature ovarian insufficiency. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 35(6), 101600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2021.101600

- Refaei, M., Mardanpour, S., Masoumi, S. Z., & Parsa, P. (2022). Women’s experiences in the transition to menopause: a qualitative research. BMC Women’s Health, 22(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01633-0

- Richardson, A., Haridass, S. A., Ward, E., Ayres, J., & Baskind, N. E. (2018). Investigation and treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency: A multi-disciplinary review of practice. 24(4), 155–162. (Publication Number 4).

- Rudnicka, E., Kruszewska, J., Klicka, K., Kowalczyk, J., Grymowicz, M., Skórska, J., Pięta, W., & Smolarczyk, R. (2018). Premature ovarian insufficiency – Aetiopathology, epidemiology, and diagnostic evaluation. Prz Menopauzalny, 17(3), 105–108. https://doi.org/10.5114/pm.2018.78550

- Sehhatie Shafaie, F., Mirghafourvand, M., & Jafari, M. (2014). Effect of education through support -group on early symptoms of menopause: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Caring Sciences, 3(4), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.5681/jcs.2014.027

- Shuster, L. T., Rhodes, D. J., Gostout, B. S., Grossardt, B. R., & Rocca, W. A. (2010). Premature menopause or early menopause: Long-term health consequences. Maturitas, 65(2), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.08.003

- Singer, D. (2012). ‘ It’s not supposed to be this way’: Psychological aspects of a premature menopause. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 12(2), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2011.648202

- Sterling, E. W., & Nelson, L. M. (2011). From victim to survivor to thriver: Helping women with primary ovarian insufficiency integrate recovery, self-management, and wellness. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 29(4), 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1280920

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol, 8, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-4

- Torrealday, S., Kodaman, P., & Pal, L. (2017). Premature ovarian insufficiency - An update on recent advances in understanding and management. F1000Res, 6, 2069. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11948.1

- van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. State University of New York Press, Albany.

- Wallach, E., & Menning, B. E. (1980). The emotional needs of infertile couples. Fertility and Sterility, 34(4), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(16)45031-4

- Webber, L., Davies, M., Anderson, R., Bartlett, J., Braat, D., Cartwright, B., Cifkova, R., de Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S., Hogervorst, E., Janse, F., Liao, L., Vlaisavljevic, V., Zillikens, C., & Vermeulen, N. (2016). ESHRE Guideline: Management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Human Reproduction, 31(5), 926–937. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew027

- Wong, E. L. Y., Huang, F., Cheung, A. W. L., & Wong, C. K. M. (2018). The impact of menopause on the sexual health of Chinese Cantonese women: A mixed methods study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(7), 1672–1684. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13568]https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13568

- Yazdkhasti, M., Keshavarz, M., Khoei, E. M., Hosseini, A., Esmaeilzadeh, S., Pebdani, M. A., & Jafarzadeh, H. (2012). The effect of support group method on quality of life in post-menopausal women. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 41(11), 78–84.

- Yazdkhasti, M., Simbar, M., & Abdi, F. (2015). Empowerment and coping strategies in menopause women: A review. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 17(3), e18944. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.18944