Abstract

Objective

Moving overseas to study can be exciting, however many international students find this transition stressful. Therefore, empirically supported strategies to assist with managing stress and supporting well-being are needed. Motivated music listening is an effective stress management strategy, and is linked with international student well-being. Tuned In is a group program designed to increase emotion awareness and regulation using motivated music listening.

Methods and measures

We evaluated a 4-session online version of Tuned In for motivated music use, emotion regulation, and well-being in international students. The study used a 2 (Treatment; Waitlist) x 3 (timepoints: pre = T1; +4 weeks = T2; +8 weeks = T3) randomised controlled cross-over design. Treatment participants (n = 23) completed Tuned In between T1 and T2, Waitlist participants (n = 27) completed Tuned In between T2 and T3.

Results

Between T1 and T2, motivated music use increased in Treatment participants but not for the Waitlist. Treatment participants were also more confident in maintaining happiness and in having healthy ways of managing emotions at T2. All participants enjoyed Tuned In.

Conclusions

Tuned In, a group-based music listening program, even when delivered online, provides benefits for international students. With student well-being at risk as they begin university, enjoyable programs that help develop skills for students’ academic journey should be a priority.

Introduction

International student adjustment

Moving overseas to study at university can be a challenging transition (Mesidor & Sly, Citation2016). While most students adapt well to their new environment when they move overseas to study, an Australian study found that approximately one third of international students experience low well-being, and feel stressed and disconnected from others. A further 7% of students adjusted in a ‘distressed and risk-taking’ manner, showing increased drug and alcohol use, and self-harm (Russell et al., Citation2010). In the same study, undergraduate students, and those for whom English was a second language, were most likely to show negative patterns of adjustment, which may be linked with issues that particularly affect international students such as homesickness, depression, anxiety, general stress, and loneliness (Mesidor & Sly, Citation2016; Russell et al., Citation2010; Sawir et al., Citation2008).

Emotional awareness and regulation may also have implications for student adjustment and stress. Higher emotional intelligence in students has been linked with higher GPA, and less academic procrastination (Hen & Goroshit, Citation2014), and emotion regulation may predict positive adjustment to studying overseas (Yoo et al., Citation2006). More broadly, emotion dysregulation predicts increases in anxiety and other mental health issues in adolescents (McLaughlin et al., Citation2011). Together, these findings emphasise the importance of emotional awareness and regulation in adjustment for international students.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated distress for international students (Firang, Citation2020; Nguyen & Balakrishnan, Citation2020; Nurunnabi et al., Citation2020). A high proportion of students in Australia experienced low well-being during the pandemic (Dodd et al., Citation2021), and international student well-being and psychological distress were significantly worse after the pandemic began (Dingle et al., Citation2022). While this distress may often be subclinical—meaning no formal diagnosis or treatment are necessary—strategies to help students manage their stress and support well-being are needed. One widely used strategy is motivated music listening—that is, music listening motivated by an emotional goal, rather than mere background music (Groarke et al., Citation2020; Linnemann et al., Citation2015; Saarikallio, Citation2011). Music listening has received attention as a practical tool to assist university students to cope with stress and improve well-being, even in the context of a global pandemic (Cabedo-Mas et al., Citation2021; Granot et al., 2021; Krause et al., Citation2021; Vidas et al., Citation2021a).

Music, emotion, and well-being

A scoping review of 63 studies of music activities, health and well-being revealed that emotional effects (such as stress management) are a mechanism by which several music activities impact health and well-being (Dingle et al., Citation2021). Of these music activities, music listening can induce a wide variety of emotional responses (Juslin, Citation2013b), and it has been suggested that emotions are inherent to experiences of music (Peretz, Citation2010). Individuals may both perceive and feel emotions in music (Evans & Schubert, Citation2008; Gabrielsson, Citation2002; Juslin, Citation2013a). Interestingly, individuals differ on how strongly they experience emotional responses to music (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, Citation2007; Juslin & Laukka, Citation2004). Emotional reasons for listening to music—for example, modifying emotions and immersing in emotions—are often reported as the primary motives for listening to music (Juslin & Laukka, Citation2004; Papinczak et al., Citation2015; Randall & Rickard, Citation2017), alongside reasons such as social connection, to relieve boredom, for entertainment, and to reduce loneliness (Groarke & Hogan, Citation2016; Kotsopoulou & Hallam, Citation2010; Papinczak et al., Citation2015; Tarrant et al., Citation2000).

While the emotional aspect of music is evident in much research on Western populations, it is important to note that emotional responses to music are both universal and culturally learned (Egermann et al., Citation2015; Laukka et al., Citation2013). For example, culturally learned preferences for arousal in music differ across people in Western-European, East-Asian, and Latin American countries (Vidas et al., Citation2021b). In contrast, similarities across cultures are demonstrated in the functions of music, where across several cultures, it is typically the emotional, self-regulation, and stress-management functions of music listening that are considered to be the most important (Boer et al., Citation2012; Boer & Fischer, Citation2011; Juslin et al., Citation2016; Schäfer et al., Citation2013).

A great deal of past research has found that music listening is effective in managing stress and other emotions (Randall et al., Citation2014; Saarikallio, Citation2011; Saarikallio & Erkkilä, Citation2007; Thayer et al., Citation1994). Research with both domestic and international students has shown that music listening is an effective stress management strategy, and for international students specifically, rating music listening as a more effective coping strategy is associated with greater well-being (Vidas et al., Citation2022). Indeed, international students actively use music streaming to manage their emotional responses (Wadley et al., Citation2019). Due to the considerable evidence for the emotional impact of music, the application of music as an emotion regulation tool has been examined, albeit with mixed results.

Music can be used by young people to satisfy mood goals (Saarikallio & Erkkilä, Citation2007), but higher and lower well-being are both possible outcomes of music listening, with the emotion regulation strategies used being crucial to achieving a positive outcome (Chin & Rickard, Citation2014; Miranda & Claes, Citation2009). The intention or motivation of the music listening may be key here, as music can be both a source of emotional strength or something that reinforces negative emotional states (McFerran, Citation2019; Saarikallio et al., Citation2015). International undergraduate university students in Australia are predominantly young adults, aged around 20–21 years old (Vidas et al., Citation2022). As such, training in healthy, motivated music listening strategies may assist these young people in using music in a way that leads to positive emotions, rather than unhealthy ways, to mitigate potential mental health issues (Dingle & Fay, Citation2017; Saarikallio et al., Citation2015).

Importantly, there is no one type of music that can be used in a healthy rather than unhealthy way—music that helps people to cope can encompass a variety of emotions (Vidas et al., Citation2021a). Music choice therefore may be important for young people to support a sense of agency (Saarikallio et al., Citation2020), portray an image to the outside world (North et al., Citation2000), and provide a sense of identity (Hense et al., Citation2014; Peck & Grealey, Citation2020). This personal choice and preference in music is notable, as participant-selected music has been shown to be more effective at evoking emotional responses than experimenter-selected music (Weth et al., Citation2015). Similarly, self-selected music may be more effective for regulating negative emotions, such as anxiety, compared with experimenter-selected music (Chan et al., Citation2011; Groarke et al., Citation2020; Groarke & Hogan, Citation2019). Together, this research suggests that a program that explicitly teaches students how to use motivated or targeted personalised music listening to regulate their emotions may be uniquely suited to improve emotion regulation skills and well-being in international students.

The Tuned In program

The Tuned In program was designed to teach young people emotional awareness, labelling, and regulation, using music listening as a means of evoking emotions during sessions (Dingle et al., Citation2016; Dingle & Fay, Citation2017). Tuned In was developed by the last author, a registered clinical psychologist, drawing from clinical experience about the limits of cognitive behaviour therapy strategies to address adolescent emotion regulation difficulties, as well as music psychology and emotion research to inform the intervention for those targets. There was an early pilot with five patients in a hospital adolescent mental health unit (Fay, Citation2011), and with adolescents in the community and secondary school (Dingle et al., Citation2016). When adapted for a controlled trial with first year students, content was condensed down to 4 × 90 minute sessions (Dingle & Fay, Citation2017). Feedback from participants in these studies led to further refinement of the program. For the current 4 × 75 minutes version of the program, we consulted with a small group of international university students recruited via word-of-mouth about the content of the sessions, presenting the manuals and asking for feedback on updated scenarios involving international students that illustrated different emotions in sessions.

Tuned In is a group-based program which focuses on the circumplex model of emotion (Russell, Citation1980), encouraging participants to select music that might influence the valence (from pleasant to unpleasant) and arousal (from high to low energy) of the listener, according to their desired emotional state. For example, participants might consider a scenario designed to evoke a particular emotion (e.g. anxiety), then reflect on a song they could use to influence their valence and arousal and discuss how or why the song might influence their affect in the group. As well as emotive scenarios, the program uses drawn imagery (Holmes & Mathews, Citation2010), body sensation activities (Nummenmaa et al., Citation2014), and lyric analysis (Ko, Citation2014) to provide additional vehicles for evoking emotional responses. In early sessions, songs and music are pre-selected and provided in the program’s manual to teach the use of the circumplex model; however, in later sessions, participants are encouraged to select music to share with the group for specific emotional purposes. The content of the 4-session Tuned In program used in the current study focused on academic emotions, and was adapted from a previous version (Dingle & Fay, Citation2017)—see , and the Open Science Framework (OSF) for the student manualFootnote1 (Dingle et al., Citation2020).

Table 1. Content of Tuned In sessions, with examples of group activities.

The Tuned In program has been trialled with young people in a range of circumstances, including at-risk adolescents, high-school students, and university students. Adolescents who completed an in-person eight session version of the program reported improved emotion awareness, identification, and regulation (Dingle et al., Citation2016). Similarly, university students (aged 18–25) who completed a four session version of the program experienced greater improvement in emotional awareness, labelling, and emotion regulation, compared with control participants (Dingle & Fay, Citation2017). Ratings of engagement and reported likelihood of using the strategies learned in the program have been consistently high (Dingle et al., Citation2016; Dingle & Fay, Citation2017).

The current study

Building on previous research, we investigated the efficacy of a pilot of the Tuned In program with first-year international university students adjusting to studying in Australia. This program was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing the opportunity to adapt and trial the Tuned In International Students program using online groups via Zoom. While research has shown that manualised psychological interventions can improve mental health during COVID-19 (Gorbeña et al., Citation2022), whether Tuned In would remain effective online was unclear, given the evidence that online groups may be inferior to in person groups (Draper & Dingle, Citation2021). The present study employed a randomised controlled cross-over design, with an intervention group (Treatment) and a waitlist control group (Waitlist) assessed at three time-points. Two key hypotheses were examined.Footnote2

First, we examined how participants’ music use might change over time, hypothesising that after Tuned In, the Treatment group’s motivated music use and ratings of the effectiveness of music as a coping strategy would increase. Due to the crossover design, this was assessed between the pre- and post-program phase for each group, thus by T3, the Waitlist group would show similar improvements. Secondly, it was hypothesised that the Treatment group (but not the Waitlist) would improve on key variables between T1 and T2: emotional awareness and confidence, emotional regulation, well-being, and mental health symptoms. Again, by T3, the waitlist group should show similar benefits of Tuned In on these variables.

Method

Participants

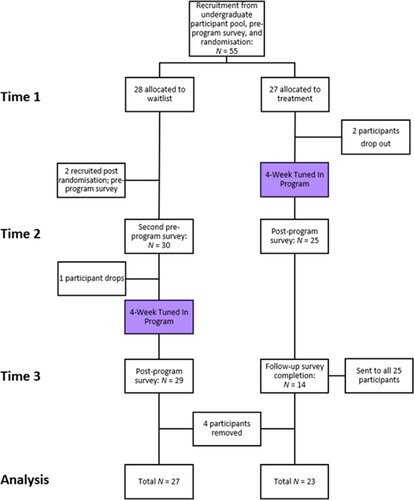

Initially, 55 undergraduate international students were recruited for the project across three semesters. The study was advertised for first-year international students in their first year of study at the University of Queensland, who self-determined their eligibility for the program. Tuned In was advertised on an online portal, listing studies for first-year psychology students to receive course credit. This was supported by flyers posted on noticeboards around campus when learning resumed in person. Students participated either for course credit, or for payment. shows the CONSORT flow chart of participants throughout the trial. At T1, all participants received a pre-program survey, and were subsequently randomised into the Treatment and Waitlist groups. At T2, after the Treatment group had completed Tuned In, the second survey was administered (a post-program survey for the Treatment group, a mid-semester check-in for the Waitlist). At T3, after the Waitlist group completed Tuned In, a third survey was administered (a follow-up survey for Treatment participants, measuring program sustainability, or a post-program survey for Waitlisted participants).

Participants who did not complete the T2 survey were removed from analysis, and those who had lived in Australia for more than 5 years were also removed. This left data from 50 international students (41 females, 9 males; no students selected ‘other/prefer not to say’), aged between 17 and 32 years old (Mage = 20.7). Demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in . The students had lived in Australia for 1.31 years on average, although two participants had not yet arrived in Australia due to COVID-19 travel restrictions. Students were predominantly of East Asian ethnicity—59.2% were South-East Asian and 18.4% were North-East Asian.

Table 2. Summary of demographic variables.

An a priori power analysis using an effect size from previous research (Dingle & Fay, Citation2017) suggested that power of .95 would be achieved for a repeated measures ANOVA testing three time points with a sample size of 52 participants. Due to concerns about missing data at T3, we elected to employ mixed-effects models rather than ANOVAs.

Materials

The Tuned In program has manuals for facilitators and participants, and was delivered in small groups of 5–10 participants, with two facilitators. The Tuned In program in this study comprised four online 75-minute sessions at weekly intervals and was adjusted specifically for international students. Groups were facilitated by the first author and provisionally registered psychologists, who received training and weekly supervision related to the program from the last author, the program developer and registered clinical psychologist.

Participants completed surveys at three time-points. Surveys were linked with a unique participant code and were anonymous. Demographics were measured at T1, while program evaluation questions were presented following students’ completion of the program. The following variables were assessed at all three time-points.

Music measures

Motivated music use

Motivations for music use were assessed with 30 items from module 4 of the MUSEBAQ (Music Use and Background Questionnaire) (Chin et al., Citation2018). Items were drawn from the musical transcendence, emotional regulation, social, musical identity and expression, and cognitive regulation sub-scales. Ratings of agreement were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; e.g. ‘Music helps me understand who I am’, ‘I use music to get through difficult times’. For the current sample, internal consistency was excellent across the three time-points, αs = .92T1; .92T2; .91T3.

MARS

Trait-like emotional sensitivity to music was assessed with the Music Affective Response Scale (MARS; Dingle et al., in prep). The scale consists of 15 items assessing positive (e.g. ‘music makes me feel happy’, ‘when I hear music I want to get up and dance’) and negative (e.g. ‘music makes me feel anxious and disturbed’, ‘I usually switch the music off when I enter a room or a car’) responses to music. Previous samples have shown good internal consistency for the MARS-Positive (α = .85) and MARS-Negative (α = .77) subscales (Dingle et al., in prep; Lewis, Citation2015). Ratings of agreement were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The current sample also showed good internal consistency for the positive subscale, αs = .85T1; .85T2; .83T3, but internal consistency was poorer for the negative subscale, αs = .57T1; .77T2; .86T3.

Effectiveness of music listening

Participants rated how often they found a list of 13 strategies for managing stress effective. This list was adapted from Thayer et al. (Citation1994), and included items such as listening to music, exercise, and rest, nap, or sleep. Ratings of agreement were measured on a 6-point scale, where those who did not use the strategy rated the item as ‘never used’, while effectiveness was measured on the remaining 5-points (from none of the time to all of the time). Only the response to music listening was included in the present study.

Musical sophistication

To describe musical experience, participants responded to a single-item measure of their musicianship—’which title best describes you’—on a scale from 1 = non-musician to 6 = professional musician, from the Ollen Musical Sophistication Index (Ollen, Citation2006; Zhang & Schubert, Citation2019). In addition, participants were asked if they currently play an instrument or sing in a choir, and if they usually listen to music in their native language. This was measured only at T1 along with participant demographics to characterise the sample.

Emotion variables

Emotion statements

An 8 item measure used in previous work (Dingle & Fay, Citation2017) assessed emotion awareness, ability to name emotions, having a range of healthy ways to manage emotions and confidence in managing specific emotions (i.e. stress related to university, anxiety, anger, sadness, and enhancing/maintaining happiness). Ratings of agreement were measured on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = never true to 7 = always true. Each item was examined separately.

Difficulties in emotion regulation

The brief version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) was used to measure emotion regulation. The 16-item version consists of items such as ‘When I’m upset, my emotions feel overwhelming’. The scale has previously shown high internal consistency (α = .92), and has shown high correlations with other measures of emotion regulation and related constructs (Bjureberg et al., Citation2016). For the current sample, internal consistency was excellent, αs = .94T1; .95T2; .96T3.

Well-being and mental health

The Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) was used to evaluate mental well-being. Items are positively worded, e.g. ‘I’ve been feeling useful’, and ratings of frequency were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time. Participants respond based on their experience over the past 2 weeks. Scores were summed to produce a total score in the range of 7 to 35, with higher scores representing higher subjective well-being. Published norms from a UK sample of 16–24 year olds showed the average for this age-group to be 23.57 (SD = 3.61) (Ng Fat et al., Citation2017). Internal consistency was good, αs = .84T1; .84T2; .87T3.

The PsyCheck is a 20 item mental health screening tool measuring symptoms of psychological distress (Jenner et al., Citation2013). Participants answered yes or no in response to list of symptoms they may have had in the past 30 days, e.g. ‘Do you feel unhappy?’ (αs = .82T1; .86T2; .86T3). Cut-off scores ranging from five to eight symptoms are considered a positive screen whereby further assessment and intervention is warranted (Jenner et al., Citation2013).

Program evaluation

Questions evaluating the program were presented in the post-program survey. Students answered six dichotomous questions (yes/no), assessing their thoughts on: whether they found the program enjoyable, whether it helped them manage emotions, if they would recommend the program to a friend, if they felt they could have their say/share music in the group, if they were achieving better grades and procrastinating less due to strategies learned in the program. Students were also asked what they enjoyed about the program, how the program could be improved, effectiveness of the online delivery, and for specific feedback about facilitators and observers.

In the T3 survey completed by participants in the Treatment condition (4 weeks after completing the program), participants were asked four questions about whether they felt they continued to use strategies learned in Tuned In and whether their relationship with music had changed since completing the program. These questions were accompanied by free entry text boxes for further elaboration on each answer.

Procedure

Students participated in the semester-long pilot program for Tuned In across three semesters, from February of 2020 to January of 2021. Four groups took place in semester 1, and two groups each in the second and third semesters. In the first semester, Tuned In was initially advertised as an in-person program, but due to COVID-19 social-distancing restrictions, it was moved online before commencement of the program. The program was advertised as running entirely online in the second and third semesters of recruitment. Participants received course credit or a $20 per hour payment for participation. The measures and procedure were approved by the University of Queensland Low and Negligible Risk Ethics Committee, #2019002846, with consent included in the beginning of the first survey.

Results

Descriptives

shows scores at T1 for motivated music use, affective response to music, emotion awareness, difficulties in emotion regulation, effectiveness of music for coping, well-being, and psychological distress. No differences were found at T1 between Treatment and Waitlist groups on any variable, ps ≥ .071. Supplementary Table 1 shows a full breakdown of the main variables, both between the two groups, across the three time-points.

Table 3. Summary of key variables at Time 1.

Differences between semesters

Of the variables assessed, there were few differences between the semesters (semester 1—February to June 2020; semester 2—July to November 2020; summer semester—November 2020 to February 2021). A series of one-way ANOVAs revealed differences only for difficulties in emotion regulation, F(2, 47) = 3.46, p = .040, η2p = .128, such that participants had greater difficulty with emotion regulation in semester 1 (M = 44.5) compared with semester 3 (M = 33.5), p = .014; there were no differences for semester 2 (M = 37.6), ps ≥ .167.

Mixed effects models

We conducted a series of mixed effects models, examining the impacts of Tuned In. After completing the program, we expected participants to show increases in motivated music use, endorsement of music as an effective coping strategy, emotion awareness, and well-being. We also expected to see decreases in difficulties in emotion regulation, and psychological distress. Time (T1, T2, T3), Group (Treatment, Waitlist), and the Time × Group interaction were fixed effects. Individual participant was included as a random intercept. Where significant effects were found, planned comparisons with Bonferroni corrections were used. For main effects related to Time, there were three comparisons, meaning the corrected alpha level was α = .05/3 = .017. For the interactions, there were seven comparisons, between and within groups at each time-point (i.e. Treatment vs Waitlist at T1, T2, and T3; Treatment at T1-T2, T2-T3; Waitlist at T1-T2; T2-T3), meaning the corrected alpha level was α = .05/7, α = .007).

Music measures

Motivated music use

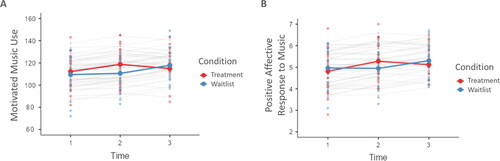

The model predicting motivated music use showed that Tuned In was promising for increasing motivated music use over the course of the program (Akaike information criterion [AIC] = 1077.32, R2M = .06, R2C = .77). The main effect of time was significant, F(2, 88) = 6.86, p = .002, and follow-up tests revealed that motivated music use increased overall from T1 to T2, p = .009, and T1 to T3, p < .001, but not between T2 and T3, p = .264. The interaction between condition and time was also significant, F(2, 88) =5.99, p = .004. Planned comparisons revealed that between T1 and T2, the Treatment group’s motivated music use increased, p = .003, while this did not change for the Waitlist group, p = .568. Similarly, between T2 and T3, the Waitlist group showed increased motivated music use, p < .001, while there was no change for the Treatment group, p = .149. Treatment and Waitlist groups were similar at T1, p = .508, T2, p = .052, and T3, p = .506. See . In total, 75.6% of variance was accounted for by differences between individuals.

Positive affective response to music

The model predicting MARS-Positive scores showed that Tuned In increased positive affective response to music (AIC = 272.85, R2M = .05, R2C = .78). Change over time was significant, F(2, 87.5) = 7.07, p = .001, and follow-up tests revealed that positive affective response to music improved overall from T1 to T2, p = .007, and T1 to T3, p < .001, but not between T2 and T3, p = .289. In addition, the interaction between condition and time was also significant, F(2, 87.5) = 5.71, p = .005. Between T1 and T2, the Treatment group showed increased positive affective response to music, p < .001, the Waitlist group showed no change, p = .894. Similarly, between T2 and T3, while the Waitlist group exhibited increased positive affective response to music, p = .002, the Treatment group did not, p = .274. Treatment and waitlist groups were similar at T1, p = .532, T2, p = .171, and T3, p = .464. See . In total, 76.4% of variance was accounted for by differences between individuals.

Negative affective response to music

The model predicting MARS-Negative scores revealed no significant effects over time or between groups (AIC = 378.15, R2M = .05, R2C = .60; ps ≥ .136), likely due to a floor effect.

Effectiveness of music as a coping strategy

Similarly, there were no significant effects the model predicting perceived effectiveness of music as a coping strategy (AIC = 304.84, R2M = .02, R2C = .61; ps ≥ .086), likely due to a ceiling effect.

Emotion variables

Confidence in managing enhancing or maintaining happiness

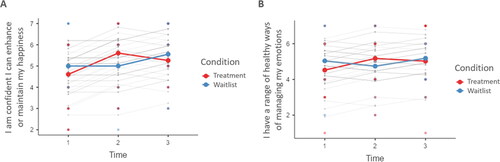

The model predicting confidence in enhancing or maintaining happiness showed that Tuned In improved this aspect of emotion, (AIC = 421.16, R2M = .08, R2C = .62). See . The main effect of time was significant, F(2, 89.2) = 7.61, p < .001, with confidence improving overall from T1 to T2, p = .002, and T1 to T3, p < .001. Furthermore, the interaction between condition and time was also significant, specifically for the Treatment group, F(2, 89.2) = 5.88, p = .004. As expected, between T1 and T2, the Treatment group improved, p < .001, while the Waitlist group did not, p = 1. However, between T2 and T3, the Waitlist group showed only marginal improvements, with a non-significant change with corrected follow-up tests, p = .011. The Treatment group also showed no change between T2 and T3, p = .214. Finally, Treatment and Waitlist groups were similar at T1, p = .260, T2, p = .081, and T3, p = .437.

Having a range of healthy ways of managing emotions

The model predicting having a range of healthy ways to manage emotions indicated that Tuned In improved this aspect of emotion in participants (AIC = 418.37, R2M = .04, R2C = .66). See . Neither of the main effects were significant, ps > .149. The interaction between condition and time, however, was significant, F(2, 88.1) = 5.06, p = .008. Between T1 and T2, the Treatment group had more confidence in having healthy ways of managing their emotions, p = .004, while the Waitlist group did not, p = .150. Between T2 and T3, the Waitlist group showed a similar trend and marginally improved after Tuned In, although this was non-significant p = .032. The Treatment group also showed no change between T2 and T3, p = .574. Treatment and Waitlist groups were similar at T1, p = .151, T2, p = .227, and T3, p = .676.

Confidence in managing emotions

The model predicting confidence in managing anxiety, (AIC = 455.42, R2M = .05, R2C = .59), showed no significant main effect of group, p = .732; however, there was a main effect of time, F(2,89.8) = 7.25, p < .001, with an increase between T1 and T2 (p = .015) and T1 and T3 (p < .001), although not between T2 and T3 (p = .143). The interaction was non-significant, F(2, 89.8) = 7.25, p = .863. No significant main effects or interactions were found in the models for other emotion variables: awareness of strong emotions (AIC = 410.80, R2M = .04, R2C = .50), naming feelings (AIC = 405.60, R2M = .06, R2C = .45), confidence in managing stress (AIC = 455.85, R2M = .01, R2C = .48), managing anger (AIC = 441.55, R2M = .02, R2C = .64), or managing sadness (AIC = 443.63, R2M = .05, R2C = .37).

Difficulties in emotion regulation

The model predicting difficulties in emotion regulation revealed no significant effects over time or between groups, (AIC = 1057.73, R2M < .01, R2C = .79).

Well-being and mental health

Finally, the models predicting well-being (AIC = 732.43, R2M = .03, R2C = .60) and psychological distress (AIC = 767.88, R2M = .03, R2C = .70) revealed no significant effects over time or between groups.

Program evaluation

Evaluation of Tuned In at post program was incredibly positive. Every participant found the program enjoyable, and 98% of participants would recommend this program to a friend. In terms of skills discussed in Tuned In, all participants found the program helpful for managing emotions, 56% felt they were achieving better grades due to using the strategies learned in the program, and 72% felt they were procrastinating less often due to the strategies learned in the program. In addition, every participant felt they could have their say in the group and share their music. Despite initial concerns about online delivery, 92% of students felt the program was delivered effectively on Zoom. In the follow-up survey, completed by just the treatment group, 85.7% (12/14) of students felt that they were still using the strategies learned 4 weeks later. Half of these students also felt that their relationship with music changed since completing Tuned In, with some elaborating in a free text box, that they appreciated music more, listened to music more, or had their own playlists now.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the efficacy of the Tuned In program with first-year international students adjusting to studying in Australia. We employed a randomised controlled crossover design, with a Treatment group and a Waitlist control group tested at three time-points.

Music use

Tuned In led to increases in motivated music listening and positive affective response to music. While these results indicate that Tuned In impacts how students engage in music listening, whether this is beneficial or for well-being remains unclear. Previous research has found that engaging with music to regulate emotions may assist in fulfilling mood goals (Saarikallio & Erkkilä, Citation2007), and help reduce depressive symptoms (Chan et al., Citation2011). Higher and lower well-being are both possible outcomes of music listening, with the emotion regulation strategies used being crucial to achieving a positive outcome (Chin & Rickard, Citation2014; Miranda & Claes, Citation2009), and music can be both a source of emotional strength or something that reinforces negative emotional states (McFerran, Citation2019; Saarikallio et al., Citation2015). In addition, previous research with international students has identified that for these students, endorsing music as a more effective coping strategy is associated with greater well-being (Vidas et al., Citation2022). In contrast to previous work linking music listening and well-being, we found no well-being changes—positive or negative—resulting from Tuned In.

There was no change in negative affective response to music and perceived effectiveness of music as a coping strategy. This lack of change may be due to a ceiling effect in effectiveness of music, and a floor effect in the negative response to music. Scores indicated that participants often found music listening an effective way to manage stress, and they tended towards being drawn to and enjoying music, consistent with previous research showing that music listening is common, enjoyable, and beneficial for young people (Papinczak et al., Citation2015; Vidas et al., Citation2021a).

Emotion, well-being and mental health

Secondly, it was hypothesised that compared to the Waitlist, Treatment participants would improve on emotional awareness, emotional regulation, well-being, and mental health symptoms after the program. We found several positive changes in emotion variables: confidence in managing anxiety increased over time (although not between groups), confidence in enhancing or maintaining happiness increased, as did the range of healthy ways students had for managing emotions. While Tuned In targeted several emotion variables, including difficulties in emotion regulation, it is interesting that these aspects of emotion were the only ones that changed. This may be due to a recency effect, as happiness was the emotion targeted in the final session.

Emotional awareness has previously been shown to be useful for well-being. Studies have shown that individuals who are adept at identifying their emotions engage in active, planned coping, with clarity of emotions associated with positive well-being (Gohm & Clore, Citation2002). Those with better emotional awareness engage in more adaptive behaviours when experiencing negative emotional states (Roberton et al., Citation2012). However, there is some evidence that naming emotions may negatively impact emotion regulation (at least via reappraisal and acceptance), although this may only be problematic for specifically naming emotions, rather than general emotional awareness (Nook et al., Citation2021). Emotion regulation and recognition has been linked to intercultural adjustment, thus programs targeting these may be helpful for first-year international students (Yoo et al., Citation2006). Although the present study did not find increases in well-being associated with Tuned In, nor large changes in the difficulties in emotion regulation scale, the fact that confidence in managing specific emotions increased suggests that a targeted program of this nature may begin to tap into these benefits.

While Tuned In did not improve well-being or psychological distress per se, there were no drops in these factors across the semester. Previous research suggests that between the beginning and end of semester, student well-being declines, presumably due to the increased pressure and deadlines (Hagemeier et al., Citation2020; Preoteasa et al., Citation2016). The consistency in well-being across time is therefore notable given the short dose and online nature of Tuned In, and the fact that students completed this program during a global pandemic. Future research with a control group who does not complete Tuned In during a semester may provide further clarity on whether this program is effective at preventing decreased well-being during periods of high academic stress.

Limitations and future directions

The present version of Tuned In had several important differences from previous versions to consider. Consistent with the present study, previous versions of Tuned In have shown promise for improving aspects of emotion awareness and confidence in finding a range of ways to manage emotions. Earlier studies with longer, in-person sessions also found improvements in emotion regulation, awareness, and identification (Dingle et al., Citation2016; Dingle & Fay, Citation2017). All versions of Tuned In, including the present study (for which 100% of participants found the program enjoyable), have been well-received by young people. One key difference to consider with the present version of Tuned In was the short dose. Not only was the program delivered online, but participants spent 75 minutes in online sessions once per week for four weeks. Future versions of Tuned In could expand to a longer, eight-session option, to assess whether shorter sessions might result in greater benefits to well-being and psychological distress. Additionally, while these results show promise, the Treatment group did not show sustained improvements between T2 and T3, suggesting that the facilitation of the program encouraged change, and longer-term impacts on intentional music listening might require a longer version of the program.

The context of COVID-19 also likely impacted the results, as much as they impacted the distribution of the program. Recent survey studies have reported that students undertaking their first year of university in 2020 were more likely to report that they were coping poorly with study than those in their first year of study in 2019, and first years in 2020 also reported more procrastination. In addition, psychological distress and loneliness was higher in 2020, and well-being lower (Dingle et al., Citation2022). While 92% of students felt that the program was delivered effectively on Zoom, as evidence suggests that online music activity groups are ‘not the same’ as in person music activity groups (Draper & Dingle, Citation2021), the inability to meet in person may have attenuated potential benefits from the program.

Finally, Tuned In targeted several emotion variables, and those that increased were confidence in enhancing or maintaining happiness, and having a range of healthy ways for managing emotions. However, the last session of the program intentionally focused on finding the enjoyment and maintaining happiness to ensure students were not left in a negative emotional state. This may have influenced these results, due to a recency effect.

In summary, while the pilot Tuned In International program differed somewhat from previous versions, every student felt that they could have their say and share their music in the group. This choice in music listening may be key to the benefits of music listening. Self-selected music may be more effective for regulating negative emotions, such as anxiety, compared with experimenter-selected music (Groarke et al., Citation2020; Groarke & Hogan, Citation2019; Howlin & Rooney, Citation2021). Indeed, the greater emotional diversity in the responses to self-selected versus experimenter-selected music (Weth et al., Citation2015) highlights the importance of participant choice of music in applied research on the benefits of music listening, such as in the present program.

Conclusions

Tuned In showed expected improvements in motivated music use, confidence in maintaining happiness, and increasing healthy ways of managing emotions. While there were no increases in well-being, this may be related to the small dose—previous versions of the program have been either longer or completed in-person. All participants found the program enjoyable and helpful for managing emotions. Taken together, this suggests that this program was successful in achieving targeted benefits for emotion, and future versions of the program might consider additional ways to sustain engagement and increase broader benefits.

Tuned In is a promising program for international first year students. Results for the Tuned In International program indicate that a group-based music listening program, even when run online, may provide benefits to new international students. With these students’ well-being at risk as they adjust to university, enjoyable programs that provide students with new skills for their academic journey should be a priority.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (49.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DV, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The full facilitators manual is available on request from the third author, [email protected] . A shortened version of the student manual is available on OSF: https://osf.io/v9m8c/ . A summary of a typical session can be found in the supplementary materials.

2 Please see OSF for pre-registration: https://osf.io/fyt37/?view_only=b483d3d50c1a4e2084db271d19e95369 . Additional pre-registered hypotheses were outside the scope of the current paper – information regarding these hypotheses can be found in the supplementary materials.

References

- Bjureberg, J., Ljótsson, B., Tull, M. T., Hedman, E., Sahlin, H., Lundh, G., Bjärehed, J., Dilillo, D., Messman-Moore, T., Hellner, C., & Gratz, K. L. (2016). Development and validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: The DERS-16. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(2), 284–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9514-x.Development

- Boer, D., & Fischer, R. (2011). Towards a holistic model of functions of music listening across cultures: A culturally decentred qualitative approach. Psychology of Music, 40(2), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735610381885

- Boer, D., Fischer, R., Tekman, H. G., Abubakar, A., Njenga, J., & Zenger, M. (2012). Young people’s topography of musical functions: Personal, social and cultural experiences with music across genders and six societies. International Journal of Psychology, 47(5), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.656128

- Cabedo-Mas, A., Arriaga-Sanz, C., & Moliner-Miravet, L. (2021). Uses and perceptions of music in times of COVID-19: A Spanish population survey. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(January), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606180

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2007). Personality and music: Can traits explain how people use music in everyday life? British Journal of Psychology (London, England : 1953), 98(Pt 2), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712606X111177

- Chan, M. F., Wong, Z. Y., & Thayala, N. V. (2011). The effectiveness of music listening in reducing depressive symptoms in adults: A systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 19(6), 332–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2011.08.003

- Chin, T., & Rickard, N. S. (2014). Emotion regulation strategy mediates both positive and negative relationships between music uses and well-being. Psychology of Music, 42(5), 692–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735613489916

- Chin, T.-C. T., Coutinho, E., Scherer, K. R., & Rickard, N. S. (2018). MUSEBAQ: A modular tool for music research to assess musicianship, musical capacity, music preferences, and motivations for music use. Music Perception, 35(3), 376–399. https://doi.org/10.1525/MP.2018.35.3.376

- Dingle, G. A., & Fay, C. (2017). Tuned in: The effectiveness for young adults of a group emotion regulation program using music listening. Psychology of Music, 45(4), 513–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735616668586

- Dingle, G. A., Han, R., & Carlyle, M. (2022). Loneliness, belonging, and mental health in Australian university students pre- and post-COVID-19. Behaviour Change, 39(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2022.6

- Dingle, G. A., Harris, R., & Vidas, D. (2020). The tuned in international students program: Using music listening to improve academic performance.

- Dingle, G. A., Hodges, J., & Kunde, A. (2016). Tuned in emotion regulation program using music listening: Effectiveness for adolescents in educational settings. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(JUN), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00859

- Dingle, G. A., Sharman, L. S., Bauer, Z., Beckman, E., Broughton, M., Bunzli, E., Davidson, R., Draper, G., Fairley, S., Farrell, C., Flynn, L. M., Gomersall, S., Hong, M., Larwood, J., Lee, C., Lee, J., Nitschinsk, L., Peluso, N., Reedman, S. E., … Wright, O. R. L. (2021). How do music activities affect health and well-being? A scoping review of studies examining psychosocial mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(September), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713818

- Dingle, G. A., Short, A. D. L., Sharman, L. S., Parker, S. L., & Williams, E. (2022). The Music Affective Response Scale (MARS): A brief self-report measure of trait emotional sensitivity to music.

- Dodd, R. H., Dadaczynski, K., Okan, O., McCaffery, K. J., & Pickles, K. (2021). Psychological wellbeing and academic experience of university students in Australia during covid-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030866

- Draper, G., & Dingle, G. A. (2021). “It’s not the same”: A comparison of the psychological needs satisfied by musical group activities in face to face and virtual modes. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(June). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646292

- Egermann, H., Fernando, N., Chuen, L., & McAdams, S. (2015). Music induces universal emotion-related psychophysiological responses: Comparing Canadian listeners to Congolese Pygmies. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(January), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01341

- Evans, P., & Schubert, E. (2008). Relationships between expressed and felt emotions in music. Musicae Scientiae, 12(1), 75–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/102986490801200105

- Fay, C. (2011). Description and pilot evaluation of tuned in: A music-based emotion regulation intervention for young people [Professional Doctorate]. School of Psychology, The University of Queensland.

- Firang, D. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on international students in Canada. International Social Work, 63(6), 820–824. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820940030

- Gabrielsson, A. (2002). Emotion perceived and emotion felt: Same or different? Musicae Scientiae, Special Issue, 123–147. https://ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsswe&AN=edsswe.oai.DiVA.org.uu.43599&site=eds-live&scope=site

- Gohm, C. L., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well-being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition and Emotion, 16(4), 495–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930143000374

- Gorbeña, S., Gómez, I., Govillard, L., Sarrionandia, S., Macía, P., Penas, P., & Iraurgi, I. (2022). The effects of an intervention to improve mental health during the COVID-19 quarantine: Comparison with a COVID control group, and a pre-COVID intervention group. Psychology & Health, 37(2), 173–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.1936520

- Granot, R., Spitz, D. H., Cherki, B. R., Loui, P., Timmers, R., Schaefer, R. S., Vuoskoski, J. K., Cárdenas-Soler, R. N., Soares-Quadros, J. F., Li, S., Lega, C., La Rocca, S., Martínez, I. C., Tanco, M., Marchiano, M., Martínez-Castilla, P., Pérez-Acosta, G., Martínez-Ezquerro, J. D., Gutiérrez-Blasco, I. M., … Israel, S. (2021). “Help! I need somebody”: Music as a global resource for obtaining wellbeing goals in times of crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(April), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648013

- Groarke, J. M., Groarke, A. M., Hogan, M. J., Costello, L., & Lynch, D. (2020). Does listening to music regulate negative affect in a stressful situation? examining the effects of self-selected and researcher-selected music using both silent and active controls. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 12(2), 288–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12185

- Groarke, J. M., & Hogan, M. J. (2016). Enhancing wellbeing: An emerging model of the adaptive functions of music listening. Psychology of Music, 44(4), 769–791. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735615591844

- Groarke, J. M., & Hogan, M. J. (2019). Listening to self-chosen music regulates induced negative affect for both younger and older adults. PLoS One, 14(6), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218017

- Hagemeier, N. E., Carlson, T. S., Roberts, C. L., & Thomas, M. (2020). A longitudinal analysis of first professional year pharmacy student well-being. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(7), 978–984. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7735

- Hen, M., & Goroshit, M. (2014). Academic procrastination, emotional intelligence, academic self-efficacy, and GPA: A comparison between students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47(2), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219412439325

- Hense, C., McFerran, K. S., & McGorry, P. (2014). Constructing a grounded theory of young people’s recovery of musical identity in mental illness. Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(5), 594–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.10.010

- Holmes, E. A., & Mathews, A. (2010). Mental imagery in emotion and emotional disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.001

- Howlin, C., & Rooney, B. (2021). Cognitive agency in music interventions: Increased perceived control of music predicts increased pain tolerance. European Journal of Pain (London, England), 25(8), 1712–1722. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1780

- Jenner, L., Cameron, J., Lee, N. K., & Nielsen, S. (2013). Test-retest reliability of PsyCheck: A mental health screening tool for substance use treatment clients. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 6(4), 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/ADD-03-2013-0008

- Juslin, P. N. (2013a). From everyday emotions to aesthetic emotions: Towards a unified theory of musical emotions. Physics of Life Reviews, 10(3), 235–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2013.05.008

- Juslin, P. N. (2013b). What does music express? Basic emotions and beyond. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(SEP), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00596

- Juslin, P. N., Barradas, G. T., Ovsiannikow, M., Limmo, J., & Thompson, W. F. (2016). Prevalence of emotions, mechanisms, and motives in music listening: A comparison of individualist and collectivist cultures. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 26(4), 293–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000161

- Juslin, P. N., & Laukka, P. (2004). Expression, perception, and induction of musical emotions: A review and a questionnaire study of everyday listening. Journal of New Music Research, 33(3), 217–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/0929821042000317813

- Ko, D. (2014). Lyric analysis of popular and original music with adolescents. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 27(4), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2014.949518

- Kotsopoulou, A., & Hallam, S. (2010). The perceived impact of playing music while studying: Age and cultural differences. Educational Studies, 36(4), 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690903424774

- Krause, A. E., Dimmock, J., Rebar, A. L., & Jackson, B. (2021). Music listening predicted improved life satisfaction in university students during early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(January), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.631033

- Laukka, P., Eerola, T., Thingujam, N. S., Yamasaki, T., & Beller, G. (2013). Universal and culture-specific factors in the recognition and performance of musical affect expressions. Emotion, 13(3), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031388

- Lewis, J. (2015). An examination of individual music listening factors in the evaluation of the music eScape app [Unpublished Masters Thesis]. The University of Queensland.

- Linnemann, A., Ditzen, B., Strahler, J., Doerr, J. M., & Nater, U. M. (2015). Music listening as a means of stress reduction in daily life. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 60, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.06.008

- McFerran, K. (2019). Crystallizing the relationship between adolescents, music, and emotions. In K. McFerran, P. Derrington, & S. Saarikallio (Eds.), Handbook of music, adolescents, and wellbeing (1st ed., pp. 3–14). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198808992.003.0001

- McLaughlin, K. A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Mennin, D. S., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2011). Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: A prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(9), 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.003

- Mesidor, J. K., & Sly, K. F. (2016). Factors that contribute to the adjustment of international students. Journal of International Students, 6(1), 262–282.

- Miranda, D., & Claes, M. (2009). Music listening, coping, peer affiliation and depression in adolescence. Psychology of Music, 37(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735608097245

- Ng Fat, L., Scholes, S., Boniface, S., Mindell, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2017). Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh mental well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the Health Survey for England. Quality of Life Research, 26(5), 1129–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1454-8

- Nguyen, O. O. T. K., & Balakrishnan, V. D. (2020). International students in Australia–during and after COVID-19. Higher Education Research and Development, 39(7), 1372–1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1825346

- Nook, E. C., Satpute, A. B., & Ochsner, K. N. (2021). Emotion naming impedes both cognitive reappraisal and mindful acceptance strategies of emotion regulation. Affective Science, 2(2), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-021-00036-y

- North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & O’Neill, S. A. (2000). The importance of music to adolescents. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709900158083

- Nummenmaa, L., Glerean, E., Hari, R., & Hietanen, J. K. (2014). Bodily maps of emotions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(2), 646–651. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321664111

- Nurunnabi, M., Almusharraf, N., & Aldeghaither, D. (2020). Mental health and well-being during the covid-19 pandemic in higher education: Evidence from g20 countries. Journal of Public Health Research, 9(S1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2020.2010

- Ollen, J. E. (2006). A criterion-related validity test of selected indicators of musical sophistication using expert ratings.

- Papinczak, Z. E., Dingle, G. A., Stoyanov, S. R., Hides, L., & Zelenko, O. (2015). Young people’s uses of music for well-being. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(9), 1119–1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1020935

- Peck, L. S. L., & Grealey, P. (2020). Autobiographical significance of meaningful musical experiences: Reflections on youth and identity. Music & Science, 3, 205920432097422. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059204320974221

- Peretz, I. (2010). Towards a neurobiology of musical emotions. In P. N. Juslin & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Handbook of music and emotion (1st ed., pp. 99–126). Oxford University Press.

- Preoteasa, C. T., Axante, A., Cristea, A. D., & Preoteasa, E. (2016). The relationship between positive well-being and academic assessment: Results from a prospective study on dental students. Education Research International, 2016, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9024687

- Randall, W. M., & Rickard, N. S. (2017). Reasons for personal music listening: A mobile experience sampling study of emotional outcomes. Psychology of Music, 45(4), 479–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735616666939

- Randall, W. M., Rickard, N. S., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2014). Emotional outcomes of regulation strategies used during personal music listening: A mobile experience sampling study. Musicae Scientiae, 18(3), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864914536430

- Roberton, T., Daffern, M., & Bucks, R. S. (2012). Emotion regulation and aggression. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.09.006

- Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161–1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

- Russell, J., Rosenthal, D., & Thomson, G. (2010). The international student experience: Three styles of adaptation. Higher Education, 60(2), 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9297-7

- Saarikallio, S. (2011). Music as emotional self-regulation throughout adulthood. Psychology of Music, 39(3), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735610374894

- Saarikallio, S., & Erkkilä, J. (2007). The role of music in adolescents’ mood regulation. Psychology of Music, 35(1), 88–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735607068889

- Saarikallio, S., Gold, C., & McFerran, K. (2015). Development and validation of the Healthy-Unhealthy Music Scale. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 20(4), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12109

- Saarikallio, S., Randall, W. M., & Baltazar, M. (2020). Music listening for supporting adolescents’ sense of agency in daily life. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(January), 2911. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02911

- Sawir, E., Marginson, S., Deumert, A., Nyland, C., & Ramia, G. (2008). Loneliness and international students: An Australian study. Journal of Studies in International Education, 12(2), 148–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307299699

- Schäfer, T., Sedlmeier, P., Städtler, C., & Huron, D. (2013). The psychological functions of music listening. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(AUG) https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00511

- Tarrant, M., North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2000). English and American adolescents’ reasons for listening to music. Psychology of Music, 28(2), 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735600282005

- Thayer, R. E., Newman, J. R., & McClain, T. M. (1994). Self-regulation of mood: Strategies for changing a bad mood, raising energy, and reducing tension. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(5), 910–925. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.5.910

- Vidas, D., Larwood, J. L., Nelson, N. L., & Dingle, G. A. (2021). Music listening as a strategy for managing COVID-19 stress in first-year university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647065

- Vidas, D., McGovern, H. T., & Nitschinsk, L. (2021). Culture and ideal affect: Cultural dimensions predict Spotify listening patterns. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/95w2t

- Vidas, D., Nelson, N. L., & Dingle, G. A. (2022). Music listening as a coping resource in domestic and international university students. Psychology of Music, 50(6), 1816–1836. https://doi.org/10.1177/03057356211066964

- Wadley, G., Krause, A., Liang, J., Wang, Z., & Leong, T. W. (2019). Use of music streaming platforms for emotion regulation by international students. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1145/3369457.3369490

- Weth, K., Raab, M. H., & Carbon, C. C. (2015). Investigating emotional responses to self-selected sad music via self-report and automated facial analysis. Musicae Scientiae, 19(4), 412–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864915606796

- Yoo, S. H., Matsumoto, D., & LeRoux, J. A. (2006). The influence of emotion recognition and emotion regulation on intercultural adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(3), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.08.006

- Zhang, J. D., & Schubert, E. (2019). A single item measure for identifying musician and nonmusician categories based on measures of musical sophistication. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 36(5), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2019.36.5.457