ABSTRACT

Situated within an important nexus for many human–animal relationships is the profession of veterinary nursing, a profession in which burnout is an increasing problem, affecting wellbeing and retention and, consequently, animal welfare. Self-care strategies can reduce the effects of burnout in the short term. However, organizational interventions are required to achieve long term change. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of burnout in veterinary nurses and identify organizational risk factors, in accordance with the Areas of Worklife model, that must be addressed to reduce burnout in this population. Seven databases and Google Scholar were searched using terms related to “burnout” and “veterinary nurses.” Primary empirical studies published in English that examined organizational factors related to burnout in veterinary nurses were eligible for inclusion. Article screening and selection was completed by two reviewers and quality assessment was carried out using two validated quality assessment tools. Twelve articles were identified: nine cross-sectional surveys and three mixed-methods studies. Available data were insufficient to accurately determine burnout prevalence, but it appears that veterinary nurses are at moderate to high risk of developing burnout. Organizational risk factors for burnout in veterinary nurses were identified in all six Areas of Worklife domains (Workload, Control, Reward, Community, Fairness, and Values). Common risk factors include high workload, low control and autonomy, underutilization, low remuneration, co-worker incivility, inequitable treatment, poor work–life balance, and exposure to animal suffering, euthanasia, and death. Recommended management strategies include increased opportunities for skill utilization and development, workload and task adjustments, and increased schedule control. However, the extent to which these strategies are effective in individuals and practicable for organizations remains poorly understood. Future research should address how these risk factors impact individuals and organizations to better inform organizational intervention strategies.

Burnout is an individual response to chronic workplace stress (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981). Historically, burnout has been reported as a syndrome occurring in caregiving occupations (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981); however, it is now recognized as a more widespread problem across other occupational groups (Maslach & Leiter, Citation2016). Despite increasing recognition, burnout was not officially recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) until 2019, when it defined it as a “syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” (WHO, Citation2023, p. 1). The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) notes that burnout is specifically a work-related issue (WHO, Citation2023). It is of interest to anthrozoologists because recent research in the veterinary industry shows that burnout is increasing across all veterinary team roles (Zak, Citation2020, Citation2021).

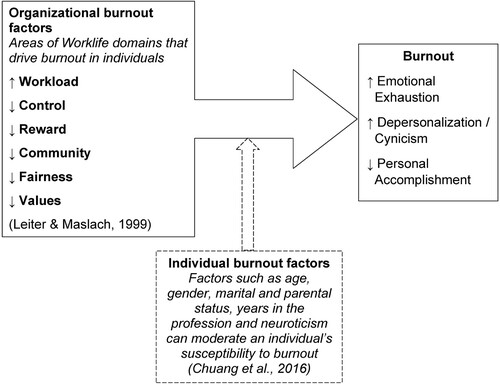

Burnout was first identified by American psychologist Herbert Freudenberger in 1974, when he described feelings of exhaustion and fatigue among staff (Freudenberger, Citation1974). Maslach and Jackson (Citation1981) further refined these characteristics into three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and reduced personal accomplishment (PA). EE describes a reduction in emotional resources to the point of feeling depleted. DP embodies feelings of cynicism, negativity, and detachment toward others in the work context, and in fact is referred to as Cynicism (Cy) in recent conceptualizations of the model. PA represents feelings of ineptitude and dissatisfaction with one’s own professional achievements (Maslach et al., Citation2023; Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981). A number of alternate burnout models have since been developed to both define and measure burnout. These include the Jobs Demands-Resources model (JD-R), which focuses on inadequate organizational resources as contributors to burnout (Demerouti et al., Citation2001), and the Areas of Worklife model (AoW), which provides a framework for understanding relationships between organizational factors and burnout (Leiter & Maslach, Citation1999).

The consequences of burnout are wide-reaching. It has been associated with a number of health impacts, including reduced immune function (Cui et al., Citation2021), memory deficits (Sandström et al., Citation2005), cardiovascular disease (Toker et al., Citation2012), poor sleep quality (Vela-Bueno et al., Citation2008), and alcohol abuse (Oreskovich et al., Citation2015). Suicidal ideation and depression have also been strongly associated with burnout; however, the direction of causality between them is as yet unknown (Andela, Citation2021; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2019; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Williams et al., Citation2020). Links between suicidal ideation and burnout are of particular concern here, considering the high reported rates of suicide in veterinarians (Rodrigues da Silva et al., Citation2023) and veterinary nurses (Witte et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, increased burnout has been associated with a decreased willingness to seek help, making early identification and intervention more critical (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2019).

Burnout consequences extend beyond the individual to the patient, team, and organization. An increase in self-reported medical errors occurs in veterinary technicians and nurses suffering from burnout (Hayes et al., Citation2020), and burnout in human nurses is linked with increased turnover (Kelly et al., Citation2021), reduced productivity (Dyrbye et al., Citation2019; Leitão et al., Citation2021), increased absenteeism, and increased presenteeism (Demerouti et al., Citation2009). This, in turn, is linked to poor patient outcomes (Rainbow, Citation2019). These outcomes also carry an economic toll for the business owing to costs associated with sick pay and staffing cover, reduced productivity, clinical errors, and turnover costs, including recruitment and training. The combined cost of lost revenue due to burnout of veterinarians and veterinary technicians is estimated at 3.89% of the industry’s total value (Neill et al., Citation2022). Considering these negative outcomes, interventions preventing the development of burnout are vital.

Burnout is often discussed alongside, and sometimes interchangeably with, compassion fatigue, as they both lead to feelings of emotional exhaustion linked to occupational stress (Lloyd & Campion, Citation2017). However, it is important to differentiate between the two as their causes, and therefore therapeutic interventions or management strategies, differ (Scotney et al., Citation2019). Compassion fatigue occurs as a result of exposure to patient suffering or trauma and leads to a reduced capacity to care. It typically arises following repeated exposure but can result from an individual event (Cavanagh et al., Citation2020). In simple terms, burnout is an organizational hazard related to the workplace, whereas compassion fatigue is an occupational hazard related to the work itself (Slatten et al., Citation2011). Consensus on the definitions of and the relationship between burnout and compassion fatigue is lacking, with some authors proposing compassion fatigue is the end result of burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Stamm, Citation2010), while others define them as two distinct and separate responses to chronic workplace stress (burnout) or secondary traumatic stress (compassion fatigue) (Figley, Citation2002). Regardless of the correlational or causal relationship between them, agreement exists that burnout and compassion fatigue are both experienced by individuals exposed to challenging workplace demands (Stamm, Citation2010; Valent, Citation2002), something which veterinary-team members are at a high risk of experiencing (Foote, Citation2023).

The veterinary team typically comprises staff with various levels of training, knowledge, and skills (RCVS, Citation2022a). Veterinary nurses, an umbrella term used here to also refer to veterinary technicians and veterinary technologists, complete a minimum of two years training depending on the country and level of qualification. Veterinary nurses assist veterinarians in the provision of direct patient care. Typical responsibilities include delivery of medical treatment; provision of surgical assistance and anesthesia; support and education of clients; and performance of medical imaging and laboratory testing to facilitate diagnosis (AVA, Citation2020; NAVTA, Citation2023; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Citation2022).

Veterinary-team members are at high risk of burnout (Moore et al., Citation2014; Soni et al., Citation2015; Zak, Citation2020, Citation2021), with veterinarians and veterinary students typically the focus of research (Brscic et al., Citation2021). More recently, research showed that burnout is also prevalent among veterinary nurses (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Kogan et al., Citation2020; NAVTA, Citation2022; Thompson et al., Citation2022) and that they may be at equal or greater risk of burnout than veterinarians (Volk et al., Citation2022; Zak, Citation2021). The average career length of veterinary nurses is between five and seven years (Chadderdon et al., Citation2014), with burnout being one of the top two reasons for veterinary nurses leaving the profession (NAVTA, Citation2022). A survey of veterinary nurses in the United Kingdom in 2019 found that only 50% would choose veterinary nursing again if they had to restart their career (Robinson et al., Citation2019). Attrition was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic due to increased demand for, and impacted delivery of, veterinary services — compounding existing workload and moral distress within the profession (Quain et al., Citation2021). Identifying and addressing the causal factors of burnout, therefore, could play a key role in addressing this increasing problem.

Burnout stems from a combination of organizational factors (related to the work environment) and individual factors (specific to the affected individual) (Edú-Valsania et al., Citation2022). It is primarily the result of chronic exposure to negative organizational factors; however, individual factors can moderate their impact by amplifying or reducing their effect on the individual (Edú-Valsania et al., Citation2022). Self-care and adaptive coping strategies can help individuals to mitigate the effects of burnout in the short term (Awa et al., Citation2010; Bartram & Gardner, Citation2008; Lloyd & Campion, Citation2017); however, addressing the causes at the organizational source is a more effective long-term strategy (Leiter & Maslach, Citation2022). The need for a shared response to burnout rather than the responsibility lying solely with the affected individual has, therefore, been widely supported to achieve more positive and longer-lasting change (Awa et al., Citation2010; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Jones-Bitton et al., Citation2023; Montgomery et al., Citation2019; Neill et al., Citation2022). Commitment to improving the mental health and wellbeing of veterinary-team members has been made by veterinary representative bodies internationally (AVA, Citation2021; RCVS, Citation2018); and is a legal obligation for employers in some countries (Australian Government, Citation2022).

The Areas of Worklife (AoW) model was developed to further define and capture the organizational factors that lead to burnout. Related risk factors were grouped into six domains to enable a better understanding of their effect on individuals and the implications for interventions. The authors propose that chronic mismatches in the employee–employer relationship across these six domains (Workload, Control, Reward, Community, Fairness, and Values) can lead to burnout (Leiter & Maslach, Citation1999). The relationships between these domains, individual burnout factors, and burnout are illustrated in . Leiter and Maslach (Citation1999) subsequently developed a tool to measure the extent to which each domain contributes to an individual’s burnout. The AoW model has been extensively used in research into healthcare worker burnout and was used to structure the remainder of this study. provides further detail on the six AoW domains.

Figure 1. Organizational factors drive burnout whereas individual factors can moderate susceptibility to burnout.

Table 1. Organizational themes outlined in Leiter and Maslach’s (Citation1999) six Areas of Worklife (AoW).

Organizational predictors of burnout in human nursing have been identified in the Workload, Control, Values, and Community domains of the AoW model (Dall’Ora et al., Citation2020), with similar findings in veterinary-team members (with the addition of the Reward domain; Ashton-James & McNeilage, Citation2022; Moore et al., Citation2014; Paul et al., Citation2023; Pizzolon et al., Citation2019; Rohlf et al., Citation2022). The extent to which these AoW domains contribute to burnout in veterinary nurses is not yet known and cannot be assumed to replicate those of human nurses or other veterinary-team members owing to differences in job demands and expectations. The aim of this study was to systematically review the existing data on burnout in veterinary nurses to determine the prevalence and identify the organizational risk factors specific to this population, in accordance with the AoW model. The results will inform the areas that veterinary-practice managers must address to deal with burnout from an organizational perspective, thereby potentially improving outcomes for veterinary nurses and, consequently, for animal welfare and the human–animal relationship they promote and sustain.

Methods

Ethics Statement

The ethics committee at La Trobe University confirmed that this study did not require ethics approval as no human or animal data were collected. The analysis was conducted on previously published data.

Search Strategy

A systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 checklist (Page et al., Citation2021). Search terms related to the research aims were combined using Boolean operators as follows: “veterinary” OR “animal care” AND “burnout” OR “burn out” OR “emotional exhaustion” OR “cynicism” OR “depersonalization” OR “personal accomplishment” OR “occupational stress.” Wildcard characters were used to search both US and UK spellings. Where available, inclusion of related terms was also selected as part of the database search process, extending the search to include terms such as “job stress” and “work stress” in addition to “occupational stress.” The initial database search was conducted by one reviewer (AC) on 13th February 2023 using the following databases: Web of Science, MEDLINE (via OVID), PsycINFO (via OVID), Embase, CAB Abstracts, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (PQDT), and EBSCO Open Dissertations. An error in the indexing of one of the databases was later identified when a relevant study was found through a backward snowballing search of references from other studies, which had not appeared in the original search (Wohlin et al., Citation2022). Communication with the database publisher confirmed a content loading issue resulting in some missing abstracts from one indexed journal. A further search using the same search terms was therefore conducted by the same reviewer (AC) using Google Scholar on 16th May 2023. Records for inclusion were limited to the first 200 results, as recommended by Haddaway et al. (Citation2015), which included the missing study but no further studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

Eligibility Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used to determine eligibility for this review: (1) studies could be qualitative or quantitative and must have been empirical research published in peer-reviewed journals or as a dissertation or thesis; (2) studies must have been written in English with no publication date limitations; (3) studies must have examined organizational factors related to burnout in veterinary nurses. Studies were excluded if they: (1) were systematic reviews, meta-analyses, narrative reports, conference proceedings, editorials, or letters; (2) focused only on veterinarians, veterinary students, or veterinary-team members collectively and did not analyze veterinary nurse data separately; (3) examined only individual factors related to burnout; (4) examined the outcomes of burnout and not contributory factors; (5) were a thesis or dissertation that had been superseded by a peer-reviewed publication of the same work.

Selection and Appraisal of Documents

Title and abstract screening were completed independently by two reviewers (AC and AM) to determine whether the identified studies met the eligibility criteria. Full text review of articles that met the criteria or could not conclusively be excluded based on the title and abstract alone was then completed independently by the same two reviewers. Covidence systematic review software (Covidence, Citation2023) was used to facilitate blinded screening and appraisal of studies. Conflicts at each stage were resolved through discussion by the two reviewers.

Quality Assessment

Two critical appraisal tools were used to assess the quality of the studies and the risk of bias (Li et al., Citation2019). The 20-item Appraisal Tool for Cross-sectional Studies (AXIS) (Downes et al., Citation2016) was used to assess cross-sectional studies. The 10-item Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for qualitative research (Lockwood et al., Citation2015) was used in combination with the AXIS tool to assess the qualitative aspects of any mixed-methods studies. The results were then combined, where applicable, to provide an overall score of methodological quality, which was rated using the following scale, which was developed in a similar systematic review (Li et al., Citation2019): weak (< 50%), fair (50–69%), good (70–79%) and very good (80–100%). Methodological quality assessment of the selected studies was conducted independently by two authors (AC and AM), and conflicts were resolved through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer (VR) where required.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer (AC) and summarized in relation to two outcome aims. Outcome one: burnout prevalence data included a description of the instrument used, the level of burnout in the population, and the prevalence where available. Outcome two: organizational risk factors for burnout were grouped in accordance with the six AoW domains (Leiter & Maslach, Citation1999). Comparison with data in these six domains from other studies was then performed.

Results

Search Results

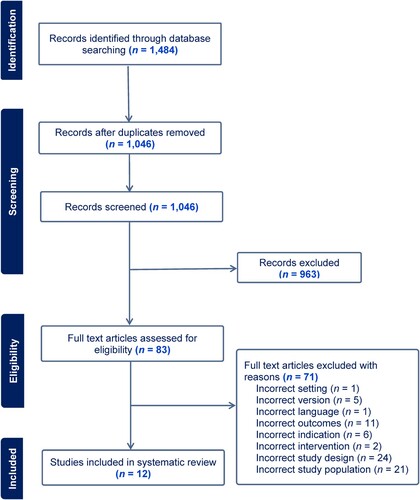

The results of the literature search are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram in . Duplicate removal included five studies where a subsequent correction or erratum had been included as a separate paper. Screening yielded 12 studies for data extraction: nine cross-sectional surveys and three mixed-methods studies published between 2011 and 2023.

Quality Assessment

The quality and risk of bias assessment of all studies is detailed in . There was a high level of agreement in the scoring between the two reviewers. Overall study quality was fair for one study, good for seven studies, and very good for four studies. All studies were of suitable quality to include in the review.

Table 2. Quality assessment results of studies included in the systematic review (n = 12), using Appraisal Tool for Cross-sectional Studies (AXIS) and the 10-item Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for qualitative research.

Study Characteristics

Of the final 12 articles, eight focused exclusively on veterinary nurses (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2022; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Smith, Citation2016), whilst the remaining four articles included veterinary nurses as part of a larger population including veterinarians (Varela & Correia, Citation2023; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019) and all veterinary-team personnel (Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023; Irwin et al., Citation2022b). The studies represented veterinary nurses across multiple continents, with four studies sampling in the US and/or Canada (Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2022; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019), three in Australia or New Zealand (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016), three in Europe and the UK (Irwin et al., Citation2022b; Smith, Citation2016; Varela & Correia, Citation2023), and two with an internationally sourced cohort (Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023; Kogan et al., Citation2020). Data were collected from a cross section of clinical settings, including ten studies examining all clinical settings (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Irwin et al., Citation2022b; Johnson, Citation2022; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Smith, Citation2016; Varela & Correia, Citation2023; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019), one examining referral teaching hospitals (Hayes et al., Citation2020), and one examining emergency veterinary practice settings (Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023). Study characteristics are presented in .

Table 3. Selected characteristics of included studies.

Burnout Measurements

Due to variance in the selected studies’ aims, there was heterogeneity in both the instruments used to determine burnout prevalence and the outcomes reported (). Across the 12 selected studies, seven instruments were used, with the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) being the most common. Measurement of burnout in the sample populations was reported in two of the 12 studies and varied from 53% to 58.3% (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Kogan et al., Citation2020), with stress as a measurement of burnout reported at 73% (Foster & Maples, Citation2014) and the risk of burnout measured at 92.8% (Smith, Citation2016). Burnout rates in the sample populations were not reported in the remaining eight studies.

Organizational Risk Factors for Burnout

Risk factors from each of the studies were grouped according to the six AoW domains (Leiter & Maslach, Citation1999).

Workload

Of the 12 studies, eight identified Workload as a risk factor for burnout in veterinary nurses (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023; Johnson, Citation2022; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Varela & Correia, Citation2023). The remaining four studies either did not review workload at all (Irwin et al., Citation2022b; Smith, Citation2016) or indirectly assessed it in terms of individual control over workload (Kogan et al., Citation2020) or the impact of workload on coworker strain (Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Workload was ranked as having the strongest association with burnout in five of the studies (Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Varela & Correia, Citation2023), and it was strongly linked to all three burnout dimensions (EE, DP, and PA) (Hayes et al., Citation2020) and was positively related to high job demands and low job resources (Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016). Potential contributors to workload stress were an inability to provide quality patient care (due to high patient loads) and insufficient support during sudden busy periods (Hayes et al., Citation2020). Shift length was found to be associated with EE and PA (Hayes et al., Citation2020), whilst the number of shifts per week and overnight shifts were also linked with higher levels of burnout (Johnson, Citation2022).

Control

Control was related to burnout in six of the 12 studies (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Control over shift length was a significant predictor for EE and Cy (Kogan et al., Citation2020), with overtime also being linked to EE. The inability to effect positive change was related to burnout in two studies (Hayes et al., Citation2020; Kogan et al., Citation2020), alongside a lack of involvement in decision making. Job control also had a significant association with burnout (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017), with qualitative data identifying ambiguity around patient treatments and expected duties, in addition to uncertainty around future employment, as key stressors (Foster & Maples, Citation2014). Finally, a lack of autonomy and control over work tasks as well as authority and discretionary power in client discussions were elucidated as workplace stressors (Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019).

Reward

Six of the 12 studies reported an association between Reward and burnout (Hayes et al., Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2022; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Varela & Correia, Citation2023; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Poor remuneration or benefits, including lack of paid sick leave or pay progression relative to experience, was positively linked to burnout in four studies (Hayes et al., Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2022; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Varela & Correia, Citation2023). Hayes et al. (Citation2020) found that this related to the EE dimension of burnout only; however, Kogan et al. (Citation2020) found that high financial reward was associated with reduced Professional Efficacy (PE) in their study participants, which measures the same burnout aspects as PA. Opportunities for skill and knowledge development were found to be a negative predictor of burnout in four studies (Hayes et al., Citation2020; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019), together with opportunities to use existing skills and knowledge (Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Both of these factors were strongly linked to all three dimensions of burnout (EE, Cy, and PE) (Kogan et al., Citation2020). The perception of doing meaningful work and a sense of professional identification were both negatively correlated with burnout (Varela & Correia, Citation2023); however, a lack of recognition and appreciation by management was positively correlated (Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016).

Community

Community was identified as a risk factor for burnout in eight of the 12 studies (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Irwin et al., Citation2022b; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Client contact (Black et al., Citation2011; Irwin et al., Citation2022b; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019) and poor coworker relationships (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019) were the key areas. Increased client contact was found to be a positive predictor for burnout in Black et al.’s (Citation2011) study, which was supported by Irwin et al.’s (Citation2022b) finding that client incivility was associated with a greater source of stress than coworker and senior colleague incivility (Irwin et al., Citation2022b). In contrast, Wallace and Buchanan (Citation2019) found that coworker strain was reported more frequently than client strain in veterinary nurses, and Smith (Citation2016) found that client interaction was linked with increased secondary traumatic stress but not burnout.

Workplace social support, including practical and emotional support from coworkers as well as assistance and feedback from supervisors, was significantly associated with burnout (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017). Conflict with veterinarians was identified as having the third highest association with burnout, behind workload and dealing with death and dying (Foster & Maples, Citation2014). Being blamed by veterinarians for client wait times, patient deaths, and client’s inability to pay bills, as well as veterinarians who yelled, cursed, and threw instruments at veterinary nurses were identified as sources of stress (Foster & Maples, Citation2014). Coworker strain was reported as relating to veterinarians more frequently than veterinary nurses or support staff (Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Negative coworker relationships were associated with all three burnout dimensions, the strongest being with the PA dimension (Hayes et al., Citation2020). Lack of veterinarian respect and trust were identified as risk factors for burnout (Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019); however, whilst respect from veterinarians was negatively associated with EE and Cy, respect from other veterinary technicians was positively associated with EE (Kogan et al., Citation2020). In contrast, senior colleague incivility was a significant predictor of job satisfaction, but not burnout (Irwin et al., Citation2022b). Finally, a lack of positive feedback and management appreciation was positively associated with stress (Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019).

Fairness

Three of the 12 studies linked Fairness to burnout (Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023; Varela & Correia, Citation2023; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Holowaychuk and Lamb (Citation2023) found that, of the six AoW domains, Fairness had the second strongest association with burnout among veterinary technicians. This was based on questions around the consistency of resource allocation and how equitable rules were within the workplace (Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023). A sense of justice and being treated fairly was found to be a protector for EE (Varela & Correia, Citation2023). Wallace and Buchanan (Citation2019) identified an imbalance in access to resources such as authority, autonomy, and discretionary power due to the lower status of veterinary nurses compared with veterinarians. The authors also found that the lower status of veterinary nurses led to a fear of losing their job if they reported concerns with veterinarians.

Values

Of the 12 studies, Values were identified in eight as a burnout risk factor (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2022; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Smith, Citation2016; Varela & Correia, Citation2023). The most common factor associated with values-driven burnout was dealing with euthanasia or patient death (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2022), which was linked to the EE and DP dimensions of burnout (Hayes et al., Citation2020). Death and dying had the second highest association with stress, behind workload, in one study (Foster & Maples, Citation2014). Interestingly, Deacon and Brough (Citation2017) found that euthanasia of healthy patients was not linked to burnout; only euthanasia of patients with a poor prognosis was. Smith (Citation2016) also found no significant correlation between euthanasia and burnout. Patient suffering was positively correlated with burnout in two studies (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Foster & Maples, Citation2014), and ethical conflict around undertaking patient care that the participant disagreed with was also associated with burnout (Hayes et al., Citation2020). Empathy for both people and animals was found to be correlated with exhaustion but not disengagement (Varela & Correia, Citation2023). Finally, having low levels of work-to-family enrichment was linked with both EE and Cy, where work-to-family enrichment was defined as the impact of positive work experiences on an individual’s personal life (Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016). This was supported by Smith (Citation2016), who also reported a link between work–life balance and burnout.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to examine the prevalence of, and organizational risk factors for, burnout in veterinary nurses to provide guidance for organizational decision makers and identify knowledge gaps. Only 12 studies were identified in the search, which is low compared with similar studies on human nurses (Dall’Ora et al., Citation2020). The selected studies ranged from fair to very good quality, although most were limited in their ability to examine causal relationships due to their cross-sectional design. In addition, the data collected may not provide a true reflection of the broader veterinary nurse profession due to methodological limitations identified in the quality analysis. Sample size justification was only reported in the methodology of three of the 12 studies. Most studies utilized convenience sampling, resulting in the risk of selection bias where eligible participants may not have had the opportunity to contribute (Downes et al., Citation2016). A fully representative sample was only achieved in one study through direct contact with all eligible individuals in a small defined population. Furthermore, internal inconsistencies, or missing data with no explanation, were identified in three of the studies. Where burnout risk factors were identified, there was largely consensus between the studies. However, not all studies explored all six domains from the AoW model, thus the frequency of issues raised may not reflect the true extent to which they contribute to burnout.

Prevalence

High levels of existing burnout were reported in over half of the respondents in one study (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017); however, due to the small sample size and geographical restriction of the sample to one Australian state, it is not possible to extrapolate from these data to determine prevalence across veterinary nurses more broadly. Similarly, whilst 58.3% of respondents were reported as scoring above the burnout threshold in another study (Kogan et al., Citation2020), the instrument used to measure burnout in participants states that cut-off scores are arbitrary and cannot be used to reliably determine a definitive cut off point for the presence of burnout (Maslach et al., Citation2023).

Prevalence rates hold value in their capacity to provide a clear measure of how widespread the issue of burnout is in any cohort. However, the challenges in obtaining a representative sample of veterinary nurses on an international scale in the included studies make this very difficult. Furthermore, the measurements presented in the studies should be interpreted with caution, owing to the use of arbitrary cut-off points and inconsistencies between instruments and burnout definitions (Demerouti et al., Citation2021; Maslach et al., Citation2023). Of the 12 included studies, 10 different burnout instruments, versions, or subscales were used to measure burnout. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that the extent of burnout reported is a true reflection of existing burnout rates; rather, it may be due to variance between the different measurement methods. Accurate prevalence data for burnout in veterinary nurses are therefore currently lacking, although there is consensus that burnout risk is high.

Leiter and Maslach (Citation2016) recommend that, rather than using a single cut-off score, burnout profiling based on three burnout dimensions (EE, DP/Cy, and PA) should be used. In their proposed framework, burnout is measured along a continuum, with engagement and burnout as the two endpoints. Burnout represents high scores in all three burnout dimensions, whereas engagement denotes low scores in all three. Three further profiles exist between these end points – ineffective (low PA), overextended (high EE), and disengaged (high DP/Cy) – reflecting different patterns of burnout (Leiter & Maslach, Citation2016). To this end, the selected studies found “burnout” (Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023; Kogan et al., Citation2020) and “overextended” (Hayes et al., Citation2020; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016) profiles were the most frequent profiles reported among veterinary nurses.

Risk Factors for Burnout in Veterinary Nurses

Workload

EE features heavily in both the burnout and overextended profiles and has been strongly linked to Workload (Maslach & Leiter, Citation2008). Workload was found to be a key burnout risk factor in the selected studies, adding further support to representation of the overextended profile among veterinary nurses. However, a positive relationship was also reported between job demands and work engagement in veterinary nurses (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017), suggesting a more complex, multi-factorial relationship between Workload and burnout. Workload presents both quantitative pressures, where the volume of work exceeds an individual’s capacity, and qualitative pressures, where the type of work is the source of concern (Maslach & Leiter, Citation2008). Qualitative pressures can be further divided into job hindrances and job challenges, depending on whether they prevent individuals from working effectively and sustainably, leading to distress, or promote skill development and boost job satisfaction, leading to eustress (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017). Therefore, it is not simply a matter of being tired from excess work, but a combination of few development opportunities, poor utilization of existing skills, and minimal opportunities to rest and restore between busy periods (Maslach & Leiter, Citation2008). Job resources have been found to buffer the negative effects of workload (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007; Jimenez & Dunkl, Citation2017). In their profile development, Leiter and Maslach (Citation2016) measured resources as the sum of the remaining five AoW domains, suggesting positive scores in them will help moderate high Workload demands.

Control

Job control has a moderating effect over workload (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Kogan et al., Citation2020), which supports Leiter and Maslach’s (Citation2016) assumption. In particular, control over the work schedule is important in reducing stress in veterinary nurses (Kogan et al., Citation2020). This aligns with research in other shift-work professions, where long shifts, night shifts, irregular schedules, and mandatory overtime, are all related to burnout (Jamal, Citation2004; Peterson et al., Citation2019), with control over work schedule a strong predictor of work–life balance and burnout (Keeton et al., Citation2007). Other job control measures, such as the inability to effect change, lack of involvement in decision making, and lack of autonomy over tasks, are also associated with burnout in veterinary nurses (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Organizational empowerment moderates burnout in human nurses (Galletta et al., Citation2016). Proposed strategies to increase autonomy and control in the human nursing role include collaborative rather than hierarchical team relationships, encouraging increased responsibility through further training, and inclusion in decision making and organizational goal development (Galletta et al., Citation2016). These findings and management strategies intersect with other AoW domains also identified in Leiter and Maslach’s (Citation2009) research on burnout in human nursing, where Control was predictive of Fairness, Reward, and Community. Therefore, strategies to increase perceived levels of control among veterinary nurses should also moderate risk factors in these three AoW domains.

Reward

Reward can be classified as financial, social, or institutional; as such, it includes opportunities to gain intrinsic satisfaction from the job (Maslach & Leiter, Citation2008). A lack of opportunities to use existing skills and knowledge, as well as develop new skills, was identified as a key risk factor for all three dimensions of burnout in veterinary nurses (Hayes et al., Citation2020; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Recent studies confirm that veterinary nurses are not performing tasks that they are trained for, with only 57–60% of these tasks being delegated to veterinary nurses, despite support for appropriate utilization from veterinarians and practice managers (Brown, Citation2022; Harvey & Cameron, Citation2019). The feeling of adding value to the workplace (Kogan et al., Citation2020) and performing meaningful work (Varela & Correia, Citation2023) are negatively associated with burnout in veterinary nurses, which aligns with findings in veterinarians that meaningful work has a positive effect on wellbeing (Wallace, Citation2019). The impact of increased utilization of veterinary nurses’ skills and knowledge, therefore, may potentially contribute to burnout reduction (Wallace, Citation2019). Remuneration is also linked to burnout in both the EE and PA dimensions (Hayes et al., Citation2020; Kogan et al., Citation2020). This finding is similar to other studies that suggest an increase in financial hardship, associated with low pay, may contribute to EE, and that a lack of value or recognition can lead to feelings of inefficacy (Maslach & Leiter, Citation2008). High Reward has the strongest link to increased PA in veterinary nurses (Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023), which identifies a clear focus for interventions in veterinary nurses scoring low in this dimension.

Community

Community influence on veterinary nurse burnout was divided into three areas: clients, coworkers, and supervisory or management relationships. There is disagreement among the studies about whether client or coworker incivility is a greater risk factor (Irwin et al., Citation2022b; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019); however, both are significantly associated with all three burnout dimensions. Workplace incivility is defined as ambiguous in its intentions to harm the victim, compared with the intentional harm associated with bullying and lateral violence (Bambi et al., Citation2018). Bullying is a serious issue affecting veterinary nurses, predominantly perpetrated by senior team members (Mind Matters and VN Futures, Citation2021). This aligns with the findings of the included studies, which reported that veterinarians are the main source of coworker incivility in the workplace (Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Irwin et al., Citation2022b; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). However, these studies primarily focused on measuring incivility between workplace status groups and therefore may not include detailed data on intra-group incivility. Furthermore, intention to harm, or lack thereof, was not explored. Social support and respect are protective factors for burnout, having a positive effect on engagement and reducing burnout levels (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Kogan et al., Citation2020; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). They also moderate the relationship between burnout and risk factors in both the Control and Workload domains in the AoW model, suggesting that a respectful and supportive workplace may enable veterinary nurses to better cope with the negative aspects of these two domains (Black et al., Citation2011). However, support in response to the suffering and death of patients is linked to an increase in stress and burnout (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017). This reverse buffering effect has also been reported in mental health nurses, due to an increased focus on negative outcomes (Jenkins & Elliott, Citation2004). Debriefing sessions structured with a constructive outlook are recommended to mitigate this effect (Jenkins & Elliott, Citation2004). Such sessions encourage staff to discuss their concerns about a situation but prevent amplification of negative appraisal beyond the specific issue. Instead, a constructive approach, focused on unburdening the specific stressor, minimizes the extension of negative feelings into the wider work environment (Jenkins & Elliott, Citation2004).

Fairness

The perceived low status of veterinary nurses was found to influence fairness through a lack of autonomy, fewer resources and power, and inequitable application of rules (Varela & Correia, Citation2023; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). Fairness was the second highest AoW domain associated with burnout in veterinary nurses, behind Workload (Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023). Organizational justice, or the perception of fairness in the workplace, is linked with a reduction in burnout (Vaamonde et al., Citation2018). It can be broken down into four categories: (1) distributive justice: fairness of organizational outcomes such as pay and progression opportunities, (2) procedural justice: fair application of organizational processes and policies, (3) interpersonal justice: fair and respectful treatment of employees, (4) informational justice: equitable access to information (Vaamonde et al., Citation2018). Examples of distributive, procedural, and interpersonal injustices were all identified in the included studies, resulting in fear of co-worker interactions and job losses if such issues were raised with managers, and increased burnout in the emotional dimension (Varela & Correia, Citation2023; Wallace & Buchanan, Citation2019). In human nurses, these same three justice categories are linked with both exhaustion and disengagement and are protective for burnout (Correia & Almeida, Citation2020).

Values

Value congruence refers to the alignment of values between an individual and the organization in which they work (Dunning et al., Citation2021). This includes direct conflict with organizational values or a perception that congruent values are not being upheld; mismatch of personal or professional values with groups, team members, or supervisors; decisions made by clients that go against values of the individual; or internal values conflict, for example when an individual is required to choose between overtime and personal commitments (Dunning et al., Citation2021; Vets, Citation2023). Links to value incongruence were identified through veterinary nurses’ experiences of poor work–life balance (Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Smith, Citation2016), requests to provide treatments or care they disagreed with (Hayes et al., Citation2020), and exposure to euthanasia, death, and suffering (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2022). There was a lack of consensus in the selected studies about the link between euthanasia and burnout, which mirrors findings in other research (Bennett & Rohlf, Citation2005; Reeve et al., Citation2005). Differing responses to euthanasia have been theorized to stem from variation between individuals' personal values and experiences. For example, perspectives regarding euthanasia of healthy animals differ between those who believe it is acceptable for the purpose of population management and those who disagree (Reeve et al., Citation2005). Others who are routinely exposed to euthanasia of animals may experience stress inoculation – the development of resilience to the emotional impacts of euthanasia resulting from regular exposure (Bennett & Rohlf, Citation2005). Furthermore, organizational differences, such as the level and source of support, have been reported to influence the extent of response to euthanasia (Bennett & Rohlf, Citation2005). Work–life balance presents a unique values challenge in the veterinary and healthcare sectors owing to the loyalty felt to patients and coworkers, as well as to families (Mullen, Citation2015). Positive role models within the organization as well as support and self-reflection have been recommended in human nursing to address this issue (Mullen, Citation2015).

Implications for Practice and Future Research

This review highlights that organizational risk factors for burnout in veterinary nurses exist in all six domains of the AoW model. Most commonly, risk factors are reported in the Workload, Control, Reward, Community, and Values domains and include high workload, low control and autonomy, underutilization, low remuneration, coworker incivility, inequitable treatment, poor work–life balance, and exposure to suffering, euthanasia, and death. Recommendations for organizational change include better utilization of existing skills and knowledge, as well as providing opportunities for further development (Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020), reducing workload and ensuring work tasks present positive challenges (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Hayes et al., Citation2020), greater control over shift pattern and length to promote work–family balance (Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023; Kogan et al., Citation2020), and training of managers in positive interpersonal relationships and identification of signs of burnout (Black et al., Citation2011; Deacon & Brough, Citation2017; Hayes et al., Citation2020). Recommendations for facilitating a socially positive work environment include holding regular team meetings, provision of positive feedback, promoting a culture of respect and acknowledging good performance (Black et al., Citation2011; Hayes et al., Citation2020; Holowaychuk & Lamb, Citation2023; Kimber & Gardner, Citation2016; Kogan et al., Citation2020). Finally, improving client interactions was supported through development of industry-wide education programs and organizational systems to reduce the impact of client incivility (Foster & Maples, Citation2014; Irwin et al., Citation2022b).

Whilst this list provides a good baseline for areas of improvement, further research is required to identify barriers that organizations face in implementing changes without compromising patient care. Addressing excess workload, for example, is currently stymied by workforce shortages and a tough economic climate, making it harder to recruit additional staff (RCVS, Citation2022b). Similarly, underutilization of veterinary nurses may be driven by a lack of trust in their skills or a lack of clarity around who is accountable in the event of an error (Brown, Citation2022). Increased utilization without addressing these concerns may result in the burden of stress being transferred to veterinarians. Whilst alternate solutions to these issues may be feasible, such as recruitment of more economical junior staff to delegate less complex nursing tasks to reduce workload, and reassurance of senior staff to allay concerns over competence and accountability, they are more likely to succeed if the relevant barriers are also addressed.

In addition, where problems cannot be addressed directly, this research highlights that there may be other resources that can be leveraged to moderate the effects. For example, Control has a moderating effect over Workload, particularly schedule control. Where the volume of work cannot be reduced, collaborating with individuals to provide some sense of control over their schedule may help to manage the workload impact in the short term until a more satisfactory solution can be found. Similarly, social support and respect have a moderating effect on high workload and low control. Where barriers exist that prevent these from being addressed, focusing on developing a culture of support and respect between all members of the team may help offset the negative effects.

Finally, it is important to understand that burnout cannot be addressed through a single, universal approach and that risk factors, both from an organizational and individual perspective, will influence the presence of, and responses to, workplace stressors (Leiter & Maslach, Citation2016). More detailed information on how these risk factors impact individuals and how individual factors act to amplify or reduce this impact is needed so that protective factors can be leveraged and burnout reduction strategies tailored most effectively to support individuals at risk. This is of particular importance in veterinary nurses who are subject to the psychosocial effects of human–animal relationships (Beetz et al., Citation2012) in addition to the negative wellbeing impacts associated with compassionate nursing-care roles (McClelland et al., Citation2018).

This review highlights the lack of qualitative data on how organizational risk factors impact veterinary nurses. Further research exploring veterinary nurse perspectives on the contributory factors to burnout is needed to broaden awareness and understanding of the issues and support the development and implementation of focused interventions at an earlier stage.

Limitations

There are several limitations that should be noted in our systematic review. As the primary focus of this review was to explore risk factors for burnout in veterinary nurses, studies examining burnout in veterinary teams that did not disaggregate data for veterinary nurses were excluded. This may have resulted in the loss of data that would have provided greater insight; however, it would not have been specific to veterinary nurses and therefore the exclusion was justified. Furthermore, due to an indexing error in one of the databases, a study was missed in the original search. Whilst steps were taken to address this, we cannot be sure that other studies have not been missed as a result of this issue.

Conclusion

Veterinary nurses are at high risk of burnout, at least partially because of the nature of the work they do, at an important area of interface between humans and animals. Risk factors have been identified in all six AoW domains; however, limited studies exist that focus on veterinary nurses. In the existing literature, inconsistencies between burnout measurement tools used and organizational risk factors measured means that the extent to which different risk factors contribute to burnout in veterinary nurses has yet to be reliably identified. This review highlights the need for further research to better understand organizational risk factors and protectors for burnout in veterinary nurses and how they impact individuals. This will inform the development of realistic interventions to reduce the negative impacts of burnout on individuals, patients, teams, and organizations.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andela, M. (2021). Work-related stressors and suicidal ideation: The mediating role of burnout. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 36(2), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2021.1897605

- Ashton-James, C. E., & McNeilage, A. G. (2022). A mixed methods investigation of stress and wellbeing factors contributing to burnout and job satisfaction in a specialist small animal hospital. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 9, 942778. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2022.942778

- Australian Government. (2022, September 15). PCBUs. https://www.comcare.gov.au/roles/pcbu

- AVA. (2020). Veterinary nursing. Australian Veterinary Association. https://www.ava.com.au/policy-advocacy/policies/accreditation-and-employment-of-veterinarians/veterinary-nursing

- AVA. (2021). Safeguarding and improving the mental health of the veterinary team. Australian Veterinary Association. https://www.ava.com.au/policy-advocacy/policies/professional-practices-for-veterinarians/safeguarding-and-improving-the-mental-health-of-the-veterinary-team/

- Awa, W. L., Plaumann, M., & Walter, U. (2010). Burnout prevention: A review of intervention programs. Patient Education and Counseling, 78(2), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.008

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bambi, S., Foà, C., De Felippis, C., Lucchini, A., Guazzini, A., & Rasero, L. (2018). Workplace incivility, lateral violence and bullying among nurses. A review about their prevalence and related factors. Acta Biomedica, 89(6-S), 51–79. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v89i6-S.7461

- Bartram, D., & Gardner, D. (2008). Coping with stress. In Practice, 30(4), 228–231. https://doi.org/10.1136/inpract.30.4.228

- Bartram, D. J., Yadegarfar, G., & Baldwin, D. S. (2009). A cross-sectional study of mental health and well-being and their associations in the UK veterinary profession. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(12), 1075–1085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0030-8

- Beetz, A., Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Julius, H., & Kotrschal, K. (2012). Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human–animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00234

- Bennett, P., & Rohlf, V. (2005). Perpetration-induced traumatic stress in persons who euthanize nonhuman animals in surgeries, animal shelters, and laboratories. Society & Animals, 13(3), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568530054927753

- Black, A. F., Winefield, H. R., & Chur-Hansen, A. (2011). Occupational stress in veterinary nurses: Roles of the work environment and own companion animal. Anthrozoös, 24(2), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303711X12998632257503

- Boyar, S., Carr, J., Mosley, D., & Carson, C. (2007). The development and validation of scores on perceived work and family demand scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 67(1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164406288173

- Brown, F. (2022, June 20–22). New Zealand veterinary practice staff utilisation [Paper presentation]. New Zealand veterinary association conference, Hamilton, New Zealand. https://www.sciquest.org.nz/browse/publications/article/169914

- Brscic, M., Contiero, B., Schianchi, A., & Marogna, C. (2021). Challenging suicide, burnout, and depression among veterinary practitioners and students: Text mining and topics modelling analysis of the scientific literature. BMC Veterinary Research, 17(1), 294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-021-03000-x

- Bursch, B., Lloyd, J., Mogil, C., Wijesekera, K., Miotto, K., Wu, M., Wilkinson, R., Klomhaus, A., Iverson, A., & Lester, P. (2017). Adaptation and evaluation of military resilience skills training for pediatric residents. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 4. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120517741298

- Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Wayne, J. H., & Grzywacz, J. G. (2006). Measuring the positive side of the work–family interface: Development and validation of a work–family enrichment scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(1), 131–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.02.002

- Carré, A., Stefaniak, N., d'Ambrosio, F., Bensalah, L., & Besche-Richard, C. (2013). The Basic Empathy Scale in Adults (BES-A): Factor structure of a revised form. Psychological Assessment, 25(3), 679–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032297

- Cavanagh, N., Cockett, G., Heinrich, C., Doig, L., Fiest, K., Guichon, J. R., Page, S., Mitchell, I., & Doig, C. J. (2020). Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nursing Ethics, 27(3), 639–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019889400

- Chadderdon, L. M., Lloyd, J. W., & Pazak, H. E. (2014). New directions for veterinary technology. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 41(1), 96–101. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0713-102R

- Chuang, C. H., Tseng, P. C., Lin, C. Y., Lin, K. H., & Chen, Y. Y. (2016). Burnout in the intensive care unit professionals: A systematic review. Medicine, 95(50), e5629. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000005629

- Correia, I., & Almeida, A. E. (2020). Organizational justice, professional identification, empathy, and meaningful work during COVID-19 pandemic: Are they burnout protectors in physicians and nurses? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 566139. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566139

- Cortina, L., & Magley, V. (2009). Patterns and profiles of response to incivility in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(3), 272–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014934

- Covidence. (2023). Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. www.covidence.org

- Cui, J., Ren, Y.-H., Zhao, F.-J., Chen, Y., Huang, Y.-F., Yang, L., & You, X.-M. (2021). Cross-sectional study of the effects of job burnout on immune function in 105 female oncology nurses at a tertiary oncology hospital. Medical Science Monitor, 27, e929711. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.929711

- Dalbert, C. (1999). The world is more just for me than generally: About the personal belief in a just world scale's validity. Social Justice Research, 12(2), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022091609047

- Dalbert, C., Montada, L., & Schmitt, M. (1987). Glaube an eine gerechte welt als motiv: Validierungskorrelate zweier skalen [belief in a just world as a motive: Validation correlates of two scales]. Psychologische Beiträge, 29(4), 596–615.

- Dall’Ora, C., Ball, J., Reinius, M., & Griffiths, P. (2020). Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Human Resources for Health, 18(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9

- Deacon, R. E., & Brough, P. (2017). Veterinary nurses’ psychological well-being: The impact of patient suffering and death. Australian Journal of Psychology, 69(2), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12119

- Demerouti, E. (1999). Oldenburn Burnout Inventory. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01688-000

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Peeters, M. C. W., & Breevaart, K. (2021). New directions in burnout research. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(5), 686–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1979962

- Demerouti, E., Le Blanc, P. M., Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hox, J. (2009). Present but sick: A three-wave study on job demands, presenteeism and burnout. Career Development International, 14(1), 50–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430910933574

- Demerouti, E., Nachreiner, F., Baker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Downes, M. J., Brennan, M. L., Williams, H. C., & Dean, R. S. (2016). Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open, 6(12), e011458. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

- Dunning, A., Louch, G., Grange, A., Spilsbury, K., & Johnson, J. (2021). Exploring nurses’ experiences of value congruence and the perceived relationship with wellbeing and patient care and safety: A qualitative study. Journal of Research in Nursing, 26(1–2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120976172

- Dyrbye, L. N., Shanafelt, T. D., Johnson, P. O., Johnson, L. A., Satele, D., & West, C. P. (2019). A cross-sectional study exploring the relationship between burnout, absenteeism, and job performance among American nurses. BMC Nursing, 18(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0382-7

- Edú-Valsania, S., Laguía, A., & Moriano, J. A. (2022). Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031780

- European Social Survey. (2018). ESS Round 9 Source Questionnaire. University of London. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/round9/fieldwork/source/ESS9_source_questionnaires.pdf

- Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(11), 1433–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10090

- Fitzpatrick, O., Biesma, R., Conroy, R. M., & McGarvey, A. (2019). Prevalence and relationship between burnout and depression in our future doctors: A cross-sectional study in a cohort of preclinical and clinical medical students in Ireland. BMJ Open, 9(4), e023297. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023297

- Foote, A. (2023). Burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress in veterinary professionals. The Veterinary Nurse, 14(2), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.12968/vetn.2023.14.2.90

- Foster, S. M., & Maples, E. H. (2014). Occupational stress in veterinary support staff. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 41(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0713-103R

- Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. Journal of Social Issues, 30(1), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x

- Friedman, R. A., Tidd, S. T., Currall, S. C., & Tsai, J. C. (2000). What goes around comes around: The impact of personal conflict style on work content style on work conflict and stress. International Journal of Conflict Management, 11(1), 32–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022834

- Galletta, M., Portoghese, I., Ciuffi, M., Sancassiani, F., Aloja, E., & Campagna, M. (2016). Working and environmental factors on job burnout: A cross-sectional study among nurses. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 12, 132–141. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901612010132

- Gray-Toft, P., & Anderson, J. G. (1981). The Nursing Stress Scale: Development of an instrument. Journal of Behavioral Assessment, 3(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01321348

- Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., & Kirk, S. (2015). The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE, 10(9), e0138237. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371journal.pone.0138237&type=printable doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

- Harvey, L., & Cameron, K. (2019). Comparison of expectations between veterinarians and veterinary nurses in tasks and responsibilities in clinical practice. The Veterinary Nurse, 10(6), 327–331. https://doi.org/10.12968/vetn.2019.10.6.327

- Hayes, G. M., LaLonde-Paul, D. F., Perret, J. L., Steele, A., McConkey, M., Lane, W. G., Kopp, R. J., Stone, H. K., Miller, M., & Jones-Bitton, A. (2020). Investigation of burnout syndrome and job-related risk factors in veterinary technicians in specialty teaching hospitals: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care, 30(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/vec.12916

- Holowaychuk, M. K., & Lamb, K. E. (2023). Burnout symptoms and workplace satisfaction among veterinary emergency care providers. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care, 33(2), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/vec.13271

- Irwin, A., Hall, D., & Ellis, H. (2022a). Ruminating on rudeness: Exploring veterinarians’ experiences of client incivility. Veterinary Record, 190(4), e1078. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.1078

- Irwin, A., Silver-MacMahon, H., & Wilcke, S. (2022b). Consequences and coping: Investigating client, co-worker and senior colleague incivility within veterinary practice. Veterinary Record, 191(7), e2030. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.2030

- Jamal, M. (2004). Burnout, stress and health of employees on non-standard work schedules: A study of Canadian workers. Stress and Health, 20(3), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1012

- Jenkins, R., & Elliott, P. (2004). Stressors, burnout and social support: Nurses in acute mental health settings. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(6), 622–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03240.x

- Jimenez, P., & Dunkl, A. (2017). The buffering effect of workplace resources on the relationship between the areas of worklife and burnout. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00012

- Johnson, C. E. H. (2022). The impact of compassion fatigue on anxiety and depression among veterinary nurses: A study on the moderating effect of compassion satisfaction [Doctoral dissertation]. Hood College. ProQuest One Academic. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2754495823?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Jones-Bitton, A., Gillis, D., Peterson, M., & McKee, H. (2023). Latent burnout profiles of veterinarians in Canada: Findings from a cross-sectional study. Veterinary Record, 192(2), e2281. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.2281

- Karasek, R., Brisson, C., Kawakami, N., Houtman, I., Bongers, P., & Amick, B. (1998). The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(4), 322–355. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.322

- Keeton, K., Johnson, T., & Hayward, R. (2007). Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work–life balance, and burnout. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 109(4), 949–955. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000258299.45979.37

- Kelly, L. A., Gee, P. M., & Butler, R. J. (2021). Impact of nurse burnout on organizational and position turnover. Nursing Outlook, 69(1), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.06.008

- Kimber, S., & Gardner, D. H. (2016). Relationships between workplace well-being, job demands and resources in a sample of veterinary nurses in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 64(4), 224–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2016.1164092

- Knudsen, H. K., Aaron Johnson, J., Martin, J. K., & Roman, P. M. (2003). Downsizing survival: The experience of work and organizational commitment. Sociological Inquiry, 73(2), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-682X.00056

- Kogan, L. R., Wallace, J. E., Schoenfeld-Tacher, R., Hellyer, P. W., & Richards, M. (2020). Veterinary technicians and occupational burnout. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 328. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00328

- Koltai, J., & Schieman, S. (2015). Job pressure and SES-contingent buffering: Resource reinforcement, substitution, or the stress of higher status? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 56(2), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146515584151

- Kristensen, T., Borritz, M., Villadsen, E., & Christensen, K. (2005). The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work and Stress, 19(3), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500297720

- Leitão, J., Pereira, D., & Gonçalves, Â. (2021). Quality of work life and contribution to productivity: Assessing the moderator effects of burnout syndrome. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2425. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/5/2425 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052425

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (1999). Six areas of worklife: A model of the organizational context of burnout. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 21(4), 472–489.

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2003). Areas of worklife: A structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In P. L. Perrewe & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Emotional and physiological processes and positive intervention strategies (Vol. 3, pp. 91–134). Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3555(03)03003-8

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2009). Nurse turnover: The mediating role of burnout. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(3), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01004.x

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2016). Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Research, 3(4), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2016.09.001

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2022). Pandemic imations for six areas of worklife. In M. P. Leiter & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Burnout while working: Lessons from pandemic and beyond (1st ed., pp. 21–37). Taylor & Francis.

- Li, C., Zhu, Y., Zhang, M., Gustafsson, H., & Chen, T. (2019). Mindfulness and athlete burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 449. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/3/449 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16030449

- Lloyd, C., & Campion, D. P. (2017). Occupational stress and the importance of self-care and resilience: Focus on veterinary nursing. Irish Veterinary Journal, 70(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13620-017-0108-7

- Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1097/xeb.0000000000000062

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. (1996). Leiter MP Maslach Burnout Inventory manual. California Consulting Psychological Press.

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., Leiter, M. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2023). Maslach Burnout Inventory. https://www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory-mbi#horizontalTab4

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

- McClelland, L. E., Gabriel, A. S., & DePuccio, M. J. (2018). Compassion practices, nurse well-being, and ambulatory patient experience ratings. Medical Care, 56(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000834

- Mind Matters and VN Futures. (2021). Report of the student veterinary nursing wellbeing discussion forum. Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. https://vetmindmatters.org/resources/report-of-the-student-veterinary-nursing-wellbeing-discussion-forum-2021/

- Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (2003). Education, social status, and health. Aldine Transaction. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=3v_jnQEACAAJ

- Montgomery, A., Panagopoulou, E., Esmail, A., Richards, T., & Maslach, C. (2019). Burnout in healthcare: The case for organisational change. BMJ, 366, l4774. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4774

- Moore, I. C., Coe, J. B., Adams, C. L., Conlon, P. D., & Sargeant, J. M. (2014). The role of veterinary team effectiveness in job satisfaction and burnout in companion animal veterinary clinics. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 245(5), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.245.5.513

- Mullen, K. (2015). Barriers to work–life balance for hospital nurses. Workplace Health & Safety, 63(3), 96–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079914565355

- NAVTA. (2022). NAVTA 2022 Demographic survey results. North Americal Veterinary Technicians Association. https://navta.net/news/navta-survey-reveals-veterinary-technician-pay-and-education-have-increased-but-burnout-debt-are-still-issues-2/

- NAVTA. (2023). What is the difference between a veterinarian, veterinary technologist, veterinary technician and veterinary assistant? North American Veterinary Technicians Association. https://navta.net/faqs/

- Neill, C. L., Hansen, C. R., & Salois, M. (2022). The economic cost of burnout in veterinary medicine. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 9, 814104. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389fvets.2022.814104 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.814104

- O'Driscoll, M., Brough, P., & Kalliath, T. (2004). Work/family conflict, psychological well-being, satisfaction and social support: A longitudinal study in New Zealand. Equal Opportunities International, 23(1/2), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610150410787846

- Oreskovich, M. R., Shanafelt, T., Dyrbye, L. N., Tan, L., Sotile, W., Satele, D., West, C. P., Sloan, J., & Boone, S. (2015). The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. The American Journal on Addictions, 24(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12173

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

- Paul, E. S. (2000). Empathy with animals and with humans: Are they linked? Anthrozoös, 13(4), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279300786999699

- Paul, N. K., Cosh, S. M., & Lykins, A. D. (2023). “A love–hate relationship with what I do”: Protecting the mental health of animal care workers. Anthrozoös, 36(3), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2023.2166712

- Pejtersen, J. H., Kristensen, T. S., Borg, V., & Bjorner, J. B. (2010). The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(3 Suppl), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494809349858

- Peterson, S. A., Wolkow, A. P., Lockley, S. W., O'Brien, C. S., Qadri, S., Sullivan, J. P., Czeisler, C. A., Rajaratnam, S. M. W., & Barger, L. K. (2019). Associations between shift work characteristics, shift work schedules, sleep and burnout in North American police officers: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 9(11), e030302. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030302

- Pizzolon, C. N., Coe, J. B., & Shaw, J. R. (2019). Evaluation of team effectiveness and personal empathy for associations with professional quality of life and job satisfaction in companion animal practice personnel. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 254(10), 1204–1217. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.254.10.1204

- Poncet, M. C., Toullic, P., Papazian, L., Kentish-Barnes, N., Timsit, J.-F., Pochard, F., Chevret, S., Schlemmer, B., & Azoulay, É. (2007). Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 175(7), 698–704. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC

- Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jans, L. (2013). A single-item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12006

- Quain, A., Mullan, S., McGreevy, P. D., & Ward, M. P. (2021). Frequency, stressfulness and type of ethically challenging situations encountered by veterinary team members during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 647108. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389fvets.2021.647108 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.647108

- Rainbow, J. G. (2019). Presenteeism: Nurse perceptions and consequences. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(7), 1530–1537. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12839

- RCVS. (2018). RCVS and AVMA join forces to tackle veterinary mental health issues. Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. https://www.rcvs.org.uk/news-and-views/news/rcvs-and-avma-join-forces-to-tackle-veterinary-mental-health/#statement