Abstract

Drawing on social integration and support literature, this study evaluates whether having in-prison friendships reduces incarcerated women’s perceptions of stress and buffers the additional stress associated with violent prison victimization. Using network and survey data from a sample of 104 incarcerated women in a Pennsylvanian prison unit, results indicate that experiencing violent victimization in prison substantially increases incarcerated women’s perceptions of stress while having greater in-prison friendship ties is associated with lower perceptions of prison stress. In addition, larger in-prison friendship networks substantially reduce the stress associated with women’s in-prison victimization, making friendships a vital resource for victimized women.

When it comes to psychological well-being, incarcerated persons are uniquely disadvantaged before, during, and after incarceration (Travis et al., Citation2014). A critical factor shaping incarcerated persons’ mental health during incarceration is the extreme stress they experience resulting from prison deprivations, including interpersonal violence, the loss of autonomy, and the severance of ties to outside friends and family (Haney, Citation2006; Kreager & Kruttschnitt, Citation2018; Sykes, Citation1958; Travis et al., Citation2014). Problems related to mental health and psychological well-being among the incarcerated are not shared equally, with imprisoned women experiencing significantly worse mental health before, during, and after incarceration compared to incarcerated men (Binswanger et al., Citation2010; Douglas et al., Citation2009; Gartner & Kruttschnitt, Citation2004; Lindquist & Lindquist, Citation1997; Owen, Citation1998; Owen et al., Citation2017).

Similar to gender differences in the prevalence of mental health challenges, perceptions of stress associated with incarceration are typically greater for incarcerated women than incarcerated men (Fedock, Citation2017; Kelman et al., Citation2022; Lindquist & Lindquist, Citation1997; Owen, Citation1998). In part, this results from incarcerated women’s experiences of greater drug dependency, trauma, abuse, and diagnosed mental health issues, as well as women’s heightened concern about their children’s well-being during their incarceration (Bloom et al., Citation2005; Owen, Citation1998; Owen et al., Citation2017). Once incarcerated, women also experience less sleep, more depression, and higher rates of self-harm behavior than men, which exacerbates an already unhealthy and extremely stressful prison environment (Bloom et al., Citation2005; Messina & Grella, Citation2006, Plugge et al., Citation2008; Sered & Norton-Hawk, Citation2013; Wooldredge & Steiner, Citation2016).

A particularly salient source of stress in prison is the fear of being victimized by others while incarcerated (Kelman et al., Citation2022). In addition, experiencing violent victimization in prison likely amplifies stress by further reducing an incarcerated person’s fragile sense of control and security (McEwen, Citation2005), increasing both acute (immediate) and chronic (long-lasting) stress (Hochstetler et al., Citation2004; Porter, Citation2019). Although men’s prisons are generally more violent than women’s (Kreager & Kruttschnitt, Citation2018; Kruttschnitt & Gartner, Citation2003; Owen, Citation1998; Trammell, Citation2009), incarcerated women remain at considerable risk of being victimized by others (Blitz et al., Citation2008; Kelman et al., Citation2022; Wolff et al., Citation2007; Wulf-Ludden, Citation2013). Despite the veritable stress likely to result after experiencing violent victimization in prison, relatively little is known about women’s experiences of violent victimization during incarceration or about factors that may increase or reduce the harmful effects of victimization on women’s experience of stress.

While victimization is likely to amplify incarcerated women’s stress, social support, integration, and companionship are routinely identified as factors that can reduce feelings of stress and improve mental health outcomes for the incarcerated (Berkman et al., Citation2000; Kelman et al., Citation2022; Listwan et al., Citation2010; Patel et al., Citation2022; Seeman et al., Citation2002). Indeed, Haynie et al. (Citation2018) documented a positive association between incarcerated men’s social connections to other men in the unit and the men’s self-reported lower levels of depressive symptoms (Haynie et al., Citation2018). Thus, findings by Haynie et al. (Citation2018) suggest that more extensive prison networks protect incarcerated men’s mental health. Moreover, social support can be particularly protective in buffering the experience of traumatic events, such as victimization (Kelman et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2014; Wilks, Citation2008). While research has examined the role of social support in reducing stress post-victimization through a qualitative lens (Chen et al., Citation2014; Ricciardelli, Citation2014), work is needed to investigate this association within the prison, leveraging a quantitative network approach and focusing on women.

The current study thus builds upon prior research by centering on the experiences of incarcerated women and investigating the relationship between prison victimization, friendship networks, and stress. In addition, we pay particular attention to whether the number of social ties to other women in prison moderates the heightened stress associated with in-prison victimization. Using novel network and survey data collected in a Pennsylvanian woman’s prison unit, we conduct ordinal logistic regression to address the following research questions: (1) Are friendship ties with other incarcerated women associated with lower perceptions of stress among incarcerated women? (2) Does experiencing violent victimization within prison elevate incarcerated women’s stress perceptions? and (3) Does having more extensive friendship networks moderate the association between in-prison victimizations and perceptions of stress among incarcerated women?

BACKGROUND

Fleury-Steiner and Wooldredge (Citation2020) note that most prison-victimization research focuses on incarcerated men, with much less attention directed toward the experiences of incarcerated women. Though often overlooked, incarcerated women also engage in violent offenses against one another while imprisoned (Blackburn & Trulson, Citation2010). Indeed, surveying five adult prisons in a Midwestern state, Wulf-Ludden (Citation2013) finds that the chance of physical victimization in prison for men and women was 50% and 30%, respectively. Other studies suggest the magnitude of victimization experienced by incarcerated women is even greater than the 30% noted by Wulf-Ludden (Citation2013), with some research suggesting that the prevalence of in-prison violent victimization is quite similar for men and women in prison (Wolff & Shi, Citation2011; Wooldredge & Steiner, Citation2016). Altogether, these studies reveal that imprisoned women experience considerable rates of prison victimization.

Within the male prison context, victimization positively correlates with higher stress, anxiety, and depression (Porter, Citation2019; Wooldredge, Citation1998) and often results in post-traumatic stress disorders (Hochstetler et al., Citation2004). Evidence also suggests that deleterious psychological effects of victimization persist even after release from prison (Listwan et al., Citation2010; Schnittker et al., Citation2012). Thus, it is unsurprising that both incarcerated men and women report fear of prison victimization as a significant concern (Porter, Citation2019), with those victimized reporting substantially reduced feelings of safety and security (Wolff & Shi, Citation2009). Further, experiencing violent victimization while incarcerated makes adapting to prison especially difficult for women, who are much more likely to have experienced violent victimization before prison (Steiner & Wooldredge, Citation2009). Given that the prison environment already functions as a harbinger of chronic stressors, the additional acute and post-traumatic stress experiences caused by in-prison victimization are likely to compound the effects of the day-to-day chronic stressors encountered in the prison environment (McEwen, Citation2005). Thus, it is unsurprising that victimized women are more likely to perceive the prison environment as hostile, dangerous, and unpredictable, all of which likely increase perceptions of stress while incarcerated (Owen et al., Citation2017).

Despite the prevalence of victimization among female prison populations, most research examining the impact of prison victimization on mental health has focused exclusively on incarcerated men (Hochstetler et al., Citation2004; Porter, Citation2019; Wooldredge, Citation1998). Furthermore, articles investigating the intersection of mental health and victimization experiences often use data that were collected after respondents were released from prison, which may not accurately capture in-prison experiences (Hochstetler et al., Citation2004; Listwan et al., Citation2010; Porter, Citation2019; Schnittker et al., Citation2012).Footnote1 Last, although literature suggests victimization is a common stressor in prison, most studies investigating the psychological impacts of in-prison victimization focus on mental health outcomes more broadly, seldom measuring stress as the outcome variable. This is a significant omission, as stress can be a precursor, mediator, and amplifier of many other mental health outcomes observed in prior studies (Haynie et al., Citation2018; McEwen, Citation2012; Seeman, Citation1997; Seplaki et al., Citation2006). Overall, previous work suggests that women victimized in prison will have higher stress levels than their non-victimized peers.

SOCIAL SUPPORT AND STRESS

Within general stress and social-support literature, having a more extensive social network provides access to social support, integration, and other beneficial resources that both reduce and buffer experiences of stress (Berkman et al., Citation2000; Lindorff, Citation2000; Listwan et al., Citation2010; Pearlin et al., Citation1981; Seeman et al., Citation2002).Footnote2 For instance, research finds that social support can minimize subsequent depression after a stressful event (Wang et al., Citation2014) and increase resiliency to stressful experiences (Wilks, Citation2008). In contrast, social isolation can amplify the detrimental effects of other stressors (Kamarck et al., Citation1990; Steptoe, Citation2000; Yang et al., Citation2013). In short, while the absence of social ties can contribute to stress, having access to a more extensive social network can reduce stress and even buffer against other stress-producing experiences, such as in-prison victimization.

Social networks primarily reduce stress by making available informational, emotional, appraisal (advice), and instrumental forms of social support (Berkman et al., Citation2000; Cohen, Citation2004). Thus, having more extensive support networks within prisons likely offer women more social outlets to (1) process events and daily life, (2) combat the separation and isolation from outside family, especially from children, and (3) provide support, advice, information, and other resources that can help make the incarceration experience less stressful. Indeed, the extant literature on the nature of incarcerated women’s relationships supports the importance placed on social connections with others. Separated from their families, women’s prisons’ social organization emphasizes building and maintaining social ties with other incarcerated women (Collica, Citation2010; Huggins et al., Citation2006; Pollock, Citation2002; Severance, Citation2005; Wulf-Ludden, Citation2013). Further, social relationships and support in prison are more critical for women than men because women are more adversely impacted by the severance of their ties with outside family, especially children (Jiang & Winfree, Citation2006).Footnote3 Consistent with this idea, prison research has found social support positively associated with incarcerated women’s well-being but not men’s (Asberg & Renk, Citation2014; Hart, Citation1995). Therefore, incarcerated women with more social ties to other women in prison are more likely to have access to emotional support and other resources to draw upon, possibly reducing perceptions of stress experienced while incarcerated.

Despite the importance of having close connections with other women in prison, a robust support system in prison can be challenging to attain. Within prisons, trusting others can be incredibly difficult, making forming and maintaining relationships in prison particularly hard (Liebling & Arnold, Citation2012; Propper, Citation1982; Young & Haynie, Citation2022). Gossip, petty disputes, and verbal abuse are common in women’s prisons, functioning as barriers to building trusting relationships (Greer, Citation2000; Jones, Citation1993; Trammell, Citation2009). In some cases, having more friendship ties with others is viewed as burdensome, because the drama of other women in prison can be exhausting and, in these cases, serve as a source of stress (Greer, Citation2000). Thus, the stress stemming from interacting with other women in prison may amplify stress for some incarcerated women and can result in avoiding social interaction altogether (Kruttschnitt et al., Citation2000; Trammell, Citation2009). Thus, while social supports typically protect women’s mental health, it is important also to consider that not all incarcerated women have access to close connections with others in prison. Moreover, having greater social ties to other incarcerated women may foster more conflict and stress than support in certain circumstances.

PRISON VICTIMIZATION, SOCIAL SUPPORT, AND STRESS

Decades of health research emphasize the importance of social support for attenuating stressful life events and increasing stress resiliency (Cohen, Citation2004; Lindorff, Citation2000; Seeman et al., Citation2002; Thoits, Citation1995; Wang et al., Citation2014; Wilks, Citation2008). Though not in the prison context, Flaspohler et al. (Citation2009) found that peer support buffered the impact of school victimization on students’ quality of life, emphasizing the value of social support after traumatic victimization. Importantly, stress is often compounded when a particularly stressful event, such as victimization, is added to an already high-stress burden (McEwen, Citation2005). Given that incarcerated women suffer great deprivations associated with imprisonment that function as salient stressors (Blevins et al., Citation2010; Douglas et al., Citation2009; Sykes, Citation1958; Zamble & Porporino, Citation1990), the additional stress of victimization likely significantly adds to their stress load. Thus, the higher stress levels of women victimized in prison may make social support and friendship ties particularly salient for mental well-being. Therefore, having more extensive social networks within prison may be especially useful for women who have experienced violent victimization within the prison. In addition, access to more extensive social networks may offer increased protection against future victimization and provide information and advice that can be used to reduce incarcerated women’s risks of future victimization. Thus, the additional resources and help provided by larger social networks may help reduce the stress that victimized women experience.

CURRENT STUDY

In sum, though prior research suggests that social ties to other incarcerated women may reduce perceptions of stress and offer particular benefits to women experiencing in-prison victimization, research has yet to empirically evaluate these associations using network data and quantitative analyses. The current study is designed to expand upon prior research by filling this gap and examining the associations between friendship networks, experiences of violent victimization, and stress perceptions occurring during incarceration among a sample of women in a prison unit in PA. Taking previous work into account, we hypothesize the following:

H1: Incarcerated women with more extensive friendship networks will experience lower stress levels than women with smaller friendship networks.

Serving as a stressor above and beyond the deprivations of prison, in-prison victimization is likely to increase the stress level experienced by incarcerated women, leading us to hypothesize:

H2: Women in prison who have experienced violent victimization during incarceration will report higher levels of stress than non-victimized imprisoned women.

Furthermore, given prior works’ identification of social support as particularly protective for those with higher stress burdens, we expect that incarcerated women with larger friendship networks will be less vulnerable to the stress-inducing aspect of prison victimization. Thus, we further hypothesize:

H3: Having access to larger friendship networks will be especially beneficial for women experiencing in-prison victimization and help reduce the stress-inducing effects of exposure to prison victimization.

DATA AND METHODS

Sample

To evaluate our hypotheses, we leverage unique data from the Woman’s Prison Inmate Networks Study (See Kreager et al., Citation2017 for more details regarding data collection). These data were designed to explore the informal social networks within a woman’s prison unit in Pennsylvania. Data were collected in 2017 from a “good behavior” unit in a minimum-security women’s prison. Women were eligible to be on this unit if their sentences were at least 3 years long and no prison rule infractions appeared on their record for at least 12 months before they transitioned to the unit, regardless of the offense’s severity or the remaining sentence’s length. At the time of the data collection, there were 131 women housed in this unit who were incarcerated for a variety of crimes and who had varying sentence lengths, including women with the most serious offenses and those sentenced to life in prison. Of these 131 women in the unit, 104 participated in the study, resulting in a 79% response rate and allowing near-complete network data to be collected for women housed in this unit.

Data were primarily collected via in-person interviews within the prison, consisting of closed and open-ended questions. In addition, all unit residents who participated in the study were asked to identify from a roster the individuals residing in their unit that they “got along with,” allowing friendship networks to be measured.Footnote4 Supporting background information on the respondents came from prison admission records, including respondent age, offense type committed, time spent in a Pennsylvania state prison, and highest education level attained. Of the 104 women represented in our data, nearly all consistently responded to the survey and roster questions. Therefore, the only variable with a missing case was education. In this case, the missing value was imputed based on the median years of education reported for the rest of the sample.

Measures

Perceptions of Stress

In the survey, stress was defined as feeling tense, restless, nervous, anxious, or unable to sleep at night due to troubled thoughts. Based on this definition, women were asked whether they currently experienced stress “never” or “rarely” (1),Footnote5 “sometimes” (2), or “most of the time” (3). These responses were compiled to create a scale (1-3) indicating whether a respondent experienced low, mid-level, or high stress, with greater stress levels scoring higher on the scale. We chose to retain the ordinal nature of this measure and apply ordinal regression for our multivariable analyses.

Victimization in Prison

Respondents were asked to disclose their violent victimization experiences while incarcerated. To measure violent victimization, respondents were asked if anyone punched, grabbed, slapped, or choked them during their current prison stay. Based on women’s responses, we created a binary measure of violent prison victimization, with 1 indicating the respondent had experienced at least one incident of in-prison victimization (0 = no victimization exposure) during their current prison stay.Footnote6

Measuring Friendship Networks

Research investigating the relationship between social support and stress typically measures social ties via respondents’ identification of other individuals they perceive as friends (i.e., in network terms, these are identified as “sent” ties). These reported friendships may or may not be reciprocated by the receiver of the nomination. Thus, an alternative way of measuring friendship networks is identifying friendship ties based on the friendship nominations the respondent received from other residents in the unit (i.e., referred to as “received” ties). Often, received ties are more appropriate when the focus is on status or popularity (i.e., the more friendship ties a respondent receives from others in the network, the greater their popularity in the network). Yet, studies addressing the role of social support on mental health after victimization do not differentiate between the two forms of social ties (Chen et al., Citation2014). Because we have few preconceived notions of whether sent or received ties matter more or less for our predicted hypotheses, we measure and consider both types of friendship ties in the following analyses, allowing us to evaluate whether the association between friendship ties and perceptions of stress differ based on how social ties were measured.

To capture perceived friendship ties (i.e., sent ties), participants in the study were asked to identify all other women in their unit they “got along with” from a unit roster. These identified friendship ties were compiled into a binary network matrix, with 1 indicating that a tie has been sent to another woman in the unit and 0 indicating no relationship between pairs of women. The measure, the number of sent friendship ties, was created by summing the number of women in the unit respondents indicated getting along with. Likewise, the number of received ties reflects the number of women in the unit who nominated the respondent as someone they got along with. These were then summed, reflecting the number of times other women identified the respondent as a friend. Both sent and received tie variables were positively skewed, reflecting a small number of women who reported having very large friendship networks or were nominated as friends by many unit residents. However, the supplementary analysis found that results remain consistent with and without transformations to account for skew. Thus, the variables were left as originally coded.

Control Variables

Our analysis included several control variables that prior research has linked to experiences of victimization or perceptions of stress. It is well known that most incarcerated women have histories characterized by abuse, trauma, and victimization experiences (Wolff et al., Citation2010). Prior literature also notes that experiences of victimization before age 18 and victimization as an adult before incarceration are associated with incarcerated women’s mental and physical health during incarceration (Messina & Grella, Citation2006; Wolff et al., Citation2010). Consequently, to better isolate the effect of experiences of in-prison victimization on current perceptions of stress, we incorporate two control variables: childhood victimization experiences and pre-incarceration victimization. Childhood victimization was measured using a binary indicator. Respondents were coded 1 if they reported having experienced sexual victimization, physical victimization, or both before age 18 (respondents not experiencing any form of childhood victimization = 0). The variable pre-incarceration victimization was measured by asking respondents if they had experienced any form of violent or sexual victimization within 12 months before their incarceration (1 = yes, 0 = no).

We also include several demographic and background characteristics as controls. Age refers to the respondent’s age in years at the time of the survey. Most of our sample is White; therefore, non-White denotes racial minority status. Non-White consists primarily of Black women but includes some Hispanic and Asian-identifying women. Years in prison captures respondents’ time in a Pennsylvania state prison during their current sentence. Education reflects respondents’ years of education.Footnote7

Analytic Strategy

We begin our analyses with descriptive statistics revealing the average stress level reported by the incarcerated women, the number of friendship ties with other unit residents (measured based on both sent and received ties), and the proportion of women victimized in prison. Following the discussion of our sample attributes, we examine descriptive statistics separately by women’s prison victimization status. Doing so provides preliminary evidence of some differences between women victimized in prison compared to those not experiencing within-prison victimization.

We present four nested ordinal logistic regression models to evaluate our three hypotheses. Model 1 allows us to assess the role of friendship ties on incarcerated women’s stress levels before adding prison victimization status. Model 2 adds the measure of in-prison victimization to Model 1. Given the importance of prior victimization in victimization literature, Model 3 adds controls for prior childhood and adult victimization status to ensure that the association between in-prison victimization and stress remains robust. Finally, Model 4 adds the interaction between friendship ties and in-prison victimization, allowing us to evaluate whether having larger friendship networks diminishes the negative association between prison victimization and stress.

RESULTS

Sample Descriptives

presents the descriptive statistics for our sample. Overall, incarcerated women in our sample averaged 1.76 on the stress scale that ranged from 1–3, indicating the average respondent reported experiencing low- or mid-level stress. Furthermore, about 28% of the women reported being violently victimized while incarcerated, similar to previous estimates of female victimization in prisons.Footnote8 On average, women identified 12 other women in their unit as someone they get along with (perceived or sent ties). However, this average masks considerable variation, with some women reporting no connections to others (2%) and others reporting getting along with almost two-thirds of the unit residents (SD = 13.17). On average, respondents received two fewer friendship nominations than they sent, with incarcerated women nominated as friends by almost 10 other women on the unit (SD = 5.2), with a range of 1–25 received nominations. Thus, while some women reported having no connections to others in the unit, every incarcerated woman was nominated as a friend by at least one other woman in the unit, with women perceiving more friendships than they received.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, incarcerated women unit 1 (N = 104).

The average age of women in the unit is 47, with women having spent an average of 10 years in prison.Footnote9 Approximately 40% of the sample identifies as non-White. On average, women completed 12 years of school, suggesting most women in our sample completed high school (or earned a diploma while incarcerated). Consistent with prior research, more than half of the women in our sample had experienced at least one instance of violent or sexual victimization before age 18 (55% of the sample), with 56% reporting experiencing adult victimization in the year preceding imprisonment.

presents descriptive statistics by victimization status and reveals substantial differences in incarcerated women’s perceptions of stress based on their victimization status. The average stress level for women victimized during their current prison stay was 2.25, significantly higher than the stress level of 1.58 reported by non-victims (p < .001). Focusing on each category of stress, about 18% of victimized women reported experiencing low stress, compared to 49% of the non-victimized women (p < .01). Consistent with our expectations, 43% of victimized women report “almost always experiencing stress” compared to only 7% of the non-victimized women reporting the highest level of stress. The percentage of women reporting mid-level stress did not significantly differ across victimization status. These descriptive results show that victimized women experienced substantially higher perceptions of stress while incarcerated than their non-victimized peers.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, by incarcerated women’s victimization status (N = 104).

Focusing on friendship ties, victimized women report having more friendships in their unit, on average nominating five more peers than non-victimized women. Although our analyses are not designed to establish causal associations, these differences in reports of friendship ties by victimization status suggest that victims may intentionally or subconsciously seek out more social connections, possibly to form allies and protect against revictimization. In contrast, when we focus on the number of other women in the unit that nominate the respondent as a friend (received ties), we find no significant difference in the number of times other women identify victimized or non-victimized women as friends.

also reveals that victimization experiences before incarceration are significantly higher for respondents who report being victimized while incarcerated. That is, victims of violence during incarceration were far more likely to have also been victimized as an adult before prison (79% compared to 47% of those not victimized in prison; p < .01). Similarly, victimized women report significantly higher experiences of childhood victimization, with 71% of women victimized in prison experiencing childhood victimization compared to 47% of non-victims (p < .05). We see no significant difference by victimized status for our other control variables.

Multivariable Results

We turn to our multivariable ordinal regression analyses presented in to evaluate our hypotheses. Consistent with our first hypothesis, Model 1 demonstrates that receiving more friendships ties is associated with 23% lower odds of being in a higher stress category, suggesting that larger friendship networks operate to reduce incarcerated women’s perceptions of stress (p < .01). On the other hand, perceiving more friendship with other women in their unit (i.e., sent ties) is not significantly associated with women’s stress levels. These findings suggest that receiving more friendship nominations is more important for shaping stress levels than incarcerated women’s perceptions of their friendship ties, offering mixed support for hypothesis 1.

Table 3. Ordinal logistic regression of stress levels, incarcerated women.

In terms of control variables, Model 1 indicates that age is associated with lower levels of perceived stress, with every additional year in age reducing the odds of being in a higher stress category by 4.8% (p < .05), suggesting older women may have more developed coping techniques for reducing some of the pains of imprisonment. However, when controlling for age, the number of years incarcerated increases perceptions of stress such that each additional year of being in prison is associated with greater odds of being in a higher stress category (increases by almost 1.06 times per year; p <.05), suggesting older women’s diminished stress is not diven by experience stemming from longer prison tenure. Similarly, each additional year of education is associated with a 37% increase in odds of being in a higher stress category. Among other variables, racial identity is unrelated to women’s perceptions of stress.

With the addition of in-prison victimization in Model 2, the estimation for received friendship ties remains robust, continuing to operate to reduce women’s perceptions of stress (p < .01), while the number of sent ties (i.e., perceived friendships) remains non-significantly associated with incarcerated women’s stress levels. Model 2 also reveals that women who were victimized while incarcerated were 6.71 times more likely to be in a higher stress category than women who did not experience prison victimization (p < .01). Thus, the results are consistent with our second hypothesis that women experiencing violent victimization in prison are more likely to report perceiving higher levels of stress than non-victimized women. Findings for age and prison tenure on stress level remain robust to the addition of in-prison victimization to the model. However, education is no longer significantly associated with stress once in-prison victimization is included.

Next, we incorporate our measures of pre-prison victimization experiences into Model 3 by adding indicators of whether respondents experienced childhood or prior adult victimization. We do so to ensure that earlier victimization experiences are not accounting for the association between prison victimization and stress. Model 3 demonstrates that controlling for victimization experienced before incarceration does not diminish the positive association observed for in-prison victimization and perceptions of stress. Including these controls does very little to alter the size or significance of other coefficients in the model. For example, the odds ratio associated with in-prison victimization decreases minimally once we account for experiences of prior victimization, suggesting previous victimization does not account for the stress-inducing effect of experiencing in-prison victimization.

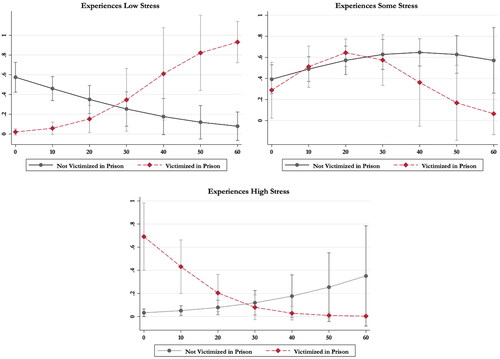

Adding the interaction effect between in-prison victimization and social ties in Model 4 allows us to evaluate whether reporting more friendship ties diminishes some of the positive association between in-prison victimization and stress levels observed in Model 3 (hypothesis 3). To do so, we estimate the predicted stress level probabilities by prison victimization status. As expected, non-victims reported a higher probability of reporting low stress (over 40%) than women who experienced in-prison victimization (less than 20%). Overall, there is little notable difference between the probability of reporting average amounts for victims and non-victims. However, women who experienced prison victimization were approximately five times as likely to report being in the highest stress category compared to non-victims, illustrating the vastly heightened stress experienced by victims of prison violence.

The interaction between victimization status and the number of perceived friendship ties is significant (p < .001), and a likelihood ratio test finds that adding the interaction term improves model fit. To aid with interpreting the interaction, we compute predicted probabilities of respondents falling into each of the three stress levels across the number of residents they “get along with” on their unit by victimization status (illustrated in ). Examining the predicted probabilities for respondents in the low-stress category (i.e., among women that reported “never” or “rarely” being stressed) in reveals that non-victimized women with few friends were more than five times more likely to report low stress levels than victimized women with few friends. However, among non-victimized women, the probability of being in the low-stress category declines as perceived ties to other women increase. This trend is substantially different for victimized women. Although victimized women with few friendship ties have much lower odds of being in the low-stress category (compared to similarly situated non-victimized women), their probability of being in the low-stress category dramatically increases as the number of friendship ties increases. Thus, victimized women reporting greater social connections to other incarcerated women are likelier to fall into the lower stress category than victimized women with fewer friends.

When focusing on the medium or average stress category (feeling stressed sometimes), shows that incarcerated women have a high probability of falling into this category, regardless of victimization status. Recalling the descriptive statistics, 43% of our sample reported feeling stressed some of the time. Given the highly stressful prison context, it is unsurprising that women report feeling stressed “sometimes.” Though a curvilinear effect appears to be present, the confidence intervals overlap, suggesting no significant difference in the likelihood of falling into this average stress category dependent on friendship ties.

Last, examining the association between victimization status and number of perceived friendship ties for women reporting the highest stress category (women reporting feeling stressed “most of the time”), illustrates that women who were not victimized in prison have a notably low probability of reporting feeling stressed “most of the time” (at most, the likelihood is 20%), an effect consistent until respondents report 30 or more friendship ties. In contrast, women experiencing in-prison victimization have a 70% chance of reporting high stress when they report having only one friend. However, the probability of reporting high stress notably tapers off with each additional reported friendship tie. For example, victimized women who reported having 20 friends they get along with were no more likely to report high stress than non-victimized women. Furthermore, victimized women with more than 20 friends have a lower probability of reporting high stress than similarly situated non-victimized women. This difference increases as friendship ties continue to increase beyond 20 friends. These results highlight the salient role of reporting more expansive friendship networks for incarcerated women who experience in-prison violent victimizations (hypothesis 3).

For these women, the more extensive their social network, the less likely they are to report higher stress levels (and the more likely they are to report lower stress). In contrast, victimized women without social connections to other unit residents were most likely to report the highest stress levels.

Thus, while larger perceived friendship networks are very beneficial for women experiencing in-prison victimization as anticipated (and consistent with hypothesis 3), larger perceived friendship networks appear less critical for reducing perceptions of stress among non-victimized women. Given that tangible and emotional support should be more closely linked to received friendship nominations, supplementary analysis also considered whether received friendship nominations buffered the stress associated with victimization. Surprisingly, the number of received friendship ties did little to moderate the effect of victimization status on perceptions of stress, in contrast to the role of reported or perceived friendship ties. This suggests that women’s perceptions of having more friendship ties are more important for alleviating the stress associated with victimization status than the actual number of other women who nominate the respondent as a friend. Altogether these results suggest that being identified as a friend by more unit residents (i.e., received ties) reduces the perception of stress among the overall unit population, while perceiving access to larger friendship networks (i.e., sent ties) is most important for reducing perceptions of stress among women who have been violently victimized during their current prison stay. When considering the heightened fear of revictimization among victims, these results suggest that perceiving larger friendship networks functions to more effectively reduce the stress of previously victimized women, perhaps by raising feelings of safety and security.

DISCUSSION

While social support, integration, and social networks have been theoretically linked to stress reduction among incarcerated women, research has yet to explore this association empirically. Furthermore, although a large body of research points to in-prison victimization as a particularly negative environmental aspect of prison time, little research has examined the extent to which experiences of in-prison victimization is associated with experiences of stress, especially among women. Finally, research has yet to empirically determine whether in-prison friendship ties can reduce some of the elevated stress experienced by victimized women.

Using unique data from a Pennsylvania women’s minimum-security prison, our study is the first to examine the association between in-prison friendship ties, prison victimization, and perceptions of stress among incarcerated women. Thus, our study is designed to answer three research questions: (1) Are friendship ties with other women in prison associated with lower perceptions of stress among incarcerated women? (2) Does experiencing violent victimization within prison elevate incarcerated women’s stress perceptions? and (3) Does having larger friendship networks moderate the association between in-prison victimizations and perceptions of stress among incarcerated women?

In line with our first hypothesis, women who received more friendship nominations from other unit residents experienced lower stress levels than women who received fewer friendship ties, indicating women benefit by being viewed as someone other women in their unit get along well with. Thus, likability appears to be an important factor in reducing stress perceptions while incarcerated. In contrast, respondents’ reports of the number of other women they get along well with were not significantly associated with lower perceived stress. When considering why received ties matter more for stress reduction than sent ties, likability and respect may be important tools that women can leverage to gain additional prison resources to help alleviate the pains of imprisonment and thus reduce perceptions of stress (Blevins et al., Citation2010; Douglas et al., Citation2009; Sykes, Citation1958; Zamble & Porporino, Citation1990). On the other hand, while an incarcerated woman may perceive other unit residents as friends, if the other residents do not reciprocate these friendship nominations, these perceived ties are less likely to result in tangible resources or benefits available to reduce perceptions of stress.

Turning to our focus on violent victimization experiences in prison, our findings were consistent with hypothesis 2, which predicted that victimized women would report greater perceptions of stress compared to their non-victimized counterparts. In addition, our results indicated that the higher stress reported by incarcerated victims persists net of controls, including pre-incarceration victimization exposure, with women victimized in prison far more likely to report experiencing the highest stress category (i.e., feeling stressed “most of the time”), compared to their non-victim peers. As expected and consistent with prior research on male prisoners (Hochstetler et al., Citation2004; Listwan et al., Citation2010; Wooldredge, Citation1998), in-prison victimization is a highly salient stressor for incarcerated women.

Last, we considered whether larger friendship networks would alleviate some of the elevated stress experienced by victimized women by introducing an interaction between friendship ties and victimization status in our statistical models. Consistent with hypothesis 3, victimized women who perceived having access to larger friendship networks experienced much lower stress levels than victims perceiving fewer friendships. Indeed, reporting larger friendship networks within the prison unit reduced elevated stress experienced by victimized women, essentially lowering perceptions of stress such that they become similar to or lower than reports of stress from their non-victimized peers. We argue that the additional stress burden and fear for safety held by victimized women make perceptions of friendship ties more salient for feelings of safety and protection against future victimization than received friendship ties. Likewise, feeling isolated from other unit residents, regardless of whether or not other incarcerated women nominate them as friends, is likely to be particularly stress inducing, especially among those experiencing violent victimization (Wooldredge, Citation1998).

By exploring the links between social networks, stress, and victimization in a woman’s prison unit, this study contributes to the growing body of research emphasizing the urgent need for prison studies to focus on the lived experiences of incarcerated women. In particular, our findings regarding the extent of violent victimization occurring during women’s incarceration indicate that this is a highly salient source of stress among women who experience it. Although less violent than in male prisons, our results indicate that violence remains pervasive in female prisons (Blackburn & Trulson, Citation2010; Kruttschnitt & Gartner, Citation2003; Owen, Citation1998). Moreover, because of the extensive history of abuse, trauma, and victimization women experience before incarceration, the continuation of violent victimization in prison likely reduces the effectiveness of any treatment or rehabilitation processes encountered during incarceration (Kelman et al., Citation2022; Owen et al., Citation2017; Wolff & Shi, Citation2011). Furthermore, although our study was limited to a focus on physically violent victimization, prior studies emphasize the high prevalence of verbal aggression and disputes among incarcerated women (Trammell, Citation2009; Wooldredge & Steiner, Citation2016; Wulf-Ludden, Citation2013). Thus, future research is needed to determine how exposure to relational violence shapes women’s incarceration experiences and consider other prison-related factors that result in either heightened or reduced stress.

Of course, one must acknowledge and consider study limitations when discussing the generalization and implications of our findings. First, although our sample size is small, with 104 women housed in a prison unit, it has sufficient power to detect significant effects in our multivariable ordinal regression models. Second, our sample is constrained to include incarcerated women housed in a “good behavior” unit in a specific prison in PA. As a result, our findings may not be generalizable to states with other prisoner demographics or other prisons within the state. In addition, because data collection focused on incarcerated women housed in a good-behavior unit, where respondents were selected to reside in the unit based on their willingness to follow institution rules and staff direction in the year preceding their move to the unit, findings may not apply to women in more secure, general-population units where there is both less incentive to avoid conflict and fewer opportunities to create supportive relationships with other unit residents.

Indeed, being in a good-behavior unit where women have greater privilege and opportunities to interact with one another will shape the interpersonal dynamics and relationships the women have, likely reducing the frequency of victimization compared to women’s experiences in the general prison population. Likewise, women in a good-behavior unit are, by design, on average older than women in the general population, because a requirement of being in the unit is having a sentence of at least 3 years, without citations for inappropriate behavior during the 12 months before entering the unit. As a result of these parameters, the unit is more likely to have women with longer sentences, including lifers, which raises the average age of women in our sample. Of note, while our sample of women experienced levels of violent prison victimization consistent with the low end of national estimates, other studies estimate more frequent violent-victimization experiences among incarcerated women (Wolff & Shi, Citation2011; Wooldredge & Steiner, Citation2016). Therefore, our findings regarding the association between experiences of prison violent victimization and perceptions of stress may be more conservative than what might be estimated among a sample of the general prison population where violent victimization is likely more prevalent.

These limitations are necessary compromises, considering the strengths of our study. Data within prisons are challenging to obtain due to their restricted nature, the increased human-subject demands, and increased scrutiny from prison gatekeepers, making data collection within prisons rare and invaluable. Having social network data, surveys, and administrative data for a unit of incarcerated women in a medium-security prison provides unprecedented insight into this often-invisible population (Belknap, Citation2001). Moreover, our near-complete network sample (with 104 of 131 unit residents participating in the study) makes these data optimal for measuring and assessing women’s social networks during incarceration. Given the highly stressful context of prisons and the connection of stress to numerous adverse health outcomes, it is extremely valuable to identify aspects of prison life that contribute to the stress-inducing climate of prisons.

Our study points to several areas that prison administrators could focus on that would reduce the stress experienced by incarcerated women. Prison administrators may consider implementing additional incentives and opportunities to reside in good-behavior units, where positive and supportive peer relationships are more readily available and easier to maintain than is possible in a general population unit—at a minimum, offering additional in-prison programming that includes greater opportunities for peer support and group-related programming designed to encourage the formation of healthy, supportive relationships, which may reduce victimization and reduce some of the stress encountered while incarcerated.

For instance, in her study of peer support groups in women’s New York prisons, Collica (Citation2010) found that fostering women’s groups emphasizing “leadership, support, and guidance” created lasting supportive bonds between participants that helped them cope with the pains of imprisonment. Groups like this would allow women to build the support needed to process victimization and trauma and reduce fear of future victimization. In a similar line, when considering the prevalence of verbal aggression escalating to violent victimization in women’s prisons resulting in reduced trust in peers (Greer, Citation2000; Trammell, Citation2009), group training oriented toward interpersonal skills training and nonviolent communication may not only improve women’s ability to make and maintain friendships but may also reduce the odds of being violently victimized. Considering the salient stress of victimization, mental health counseling and treatment should further be prioritized for women who experienced this type of trauma while incarcerated.

Beyond programming, alterations to how the prison facility is organized and administered may also encourage the formation of social bonds and reduce the fear of victimization. Kruttschnitt et al. (Citation2000), for instance, studied how the prison environment can impact the interconnectivity of residents. Importantly, having a more open, community-oriented layout of prison facilities with appealing outdoor areas is more conducive to friendship formation. Further, Kruttschnitt et al. (Citation2000) found that older prisons with more established prison culture, longer-term residents, and more trained staff also had more dense social networks. Turning to fear of victimization, a comprehensive meta-analysis of prison victimization finds that prison characteristics can also raise the risk of victimization, including larger prison populations and prisons with linear architectural designs (Steiner et al., Citation2017). Thus, emphasizing podular layouts with common open-air areas may make previously victimized women feel safer and reduce the risk of future victimization (Kruttschnitt et al., Citation2000; Steiner et al., Citation2017). Taken together, these improvements not only have the potential to improve the health and well-being of incarcerated women in the short term but may also place women in a healthier state where rehabilitation is more likely to occur increasing the likelihood of successful community reentry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Nicolo Pinchak, David Melamed, Michael Vuolo, Ryan King, and Cynthia Colen at The Ohio State University for their invaluable feedback.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used in this study is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37514.v2.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 When social-network data are collected after a network is dispersed, the data will be less complete due to forgetfulness (Brewer, Citation2000). Supporting this, Hammer (Citation1984) finds respondents are notably more likely to forget those they have not interacted with in the past week, implying social-network samples collected post-prison will suffer from forgotten ties.

2 Berkman et al. (Citation2000) define social support as the availability of “emotional, instrumental, appraisal, and informational” aid from others.

3 One reason social support may be especially important for incarcerated women is that female prisoners often have less experience and more difficulty developing and utilizing healthy coping strategies compared to the non-incarcerated population (Blevins et al., Citation2010; Douglas et al., Citation2009; Zamble & Porporino, Citation1990).

4 Incarcerated women were asked about those women on the unit they “got along with” rather than directly asking them to identify their friends. This was done purposely because prior research suggests that many incarcerated persons view the term “friendship” very critically and, when directly asked about their friendships, would immediately say that people in prison do not have friendships but rather acquaintances they get along with (Greer, Citation2000; Severance, Citation2005). Upon further prodding, they would describe their acquaintances with very similar terms used to describe friendships.

5 The responses for the “never” category did not contain any women who were victimized in prison. Therefore, the “never” and “rarely” categories were collapsed into one “low stress” category to attain satisfactory cell counts.

6 We also have measures for sexual victimization, but only two women in our sample experienced this form of victimization. Therefore, we focus our analysis exclusively on violent victimization.

7 In supplementary analyses, we evaluated whether our results were robust to alternative controls, including whether the respondent was serving a life sentence, had children, relationship status, drug offence status, and religiosity. Inclusion of these additional controls did not significantly improve model fit or change the findings presented here. Thus, we omitted these additional controls from final models.

8 It is worth noting all cases of recorded victimizations were perpetrated by another incarcerated woman; no respondents reported abuse from a corrections officer.

9 Women in a good-behavior unit are on average, older than women in the general population. This is because a requirement of being in the unit is having a sentence of at least 3 years, without citations for inappropriate behavior during the 12 months prior to entering the unit. As a result of these parameters, the unit is more likely to have women with longer sentences, including lifers, which raises the average age of women in our sample.

REFERENCES

- Asberg, K., & Renk, K. (2014). Perceived stress, external locus of control, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment among female inmates with or without a history of sexual abuse. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(1), 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X12461477

- Belknap, J. (2001). The invisible woman: Gender, crime and justice. Wadsworth Press.

- Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., & Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 51(6), 843–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4

- Binswanger, I. A., Merrill, J. O., Krueger, P. M., White, M. C., Booth, R. E., & Elmore, J. G. (2010). Gender differences in chronic medical, psychiatric, and substance-dependence disorders among jail inmates. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 476–482. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.149591

- Blackburn, A. G., & Trulson, C. R. (2010). Sugar and spice and everything nice? Exploring institutional misconduct among serious and violent female delinquents. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(6), 1132–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.09.001

- Blevins, K. R., Listwan, S. J., Cullen, F. T., & Jonson, C. L. (2010). A general strain theory of prison violence and misconduct: An integrated model of inmate behavior. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 26(2), 148–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986209359369

- Blitz, C. L., Wolff, N., & Shi, J. (2008). Physical victimization in prison: The role of mental illness. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 31(5), 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.08.005

- Bloom, B., Owen, B., & Covington, S. (2005). Gender-responsive strategies for women offenders. National Institution of Corrections. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Brewer, D. D. (2000). Forgetting in the recall-based elicitation of person and social networks. Social Networks, 22(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8733(99)00017-9

- Chen, Y., Lai, Y., & Lin, C. (2014). The impact of prison adjustment among women offenders: A Taiwanese perspective. The Prison Journal, 94(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885513512083

- Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health. The American Psychologist, 59(8), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676

- Collica, K. (2010). Surviving incarceration: Two prison-based peer programs build communities of support for female offenders. Deviant Behavior, 31(4), 314–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639620903004812

- Douglas, N., Plugge, E., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2009). The impact of imprisonment on health: What do women prisoners say? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63(9), 749–754. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.080713

- Fedock, G. (2017). Women’s psychological adjustment to prison: A review for future social work directions. Social Work Research, 41(1), 31–42.

- Flaspohler, P. D., Elfstrom, J. L., Vanderzee, K. L., Sink, H. E., & Birchmeier, Z. (2009). Stand by me: The effects of peer and teacher support in mitigating the impact of bullying on quality of life. Psychology in the Schools, 46(7), 636–649. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20404

- Fleury-Steiner, B., & Wooldredge, J. (2020). Understanding and reducing prison violence: An integrated social control-opportunity perspective. Routledge.

- Gartner, R., & Kruttschnitt, C. (2004). A brief history of doing time: The California institution for women in the 1960s and the 1990s. Law & Society Review, 38(2), 267–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0023-9216.2004.03802009.x

- Greer, K. R. (2000). The changing nature of interpersonal relationships in a women’s prison. The Prison Journal, 80(4), 442–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885500080004009

- Hammer, M. (1984). Explorations into the meaning of social network interview data. Social Networks, 6(4), 341–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(84)90008-X

- Haney, C. (2006). Reforming punishment: Psychological limits to the pains of imprisonment. American Psychological Association Books.

- Hart, C. B. (1995). Gender differences in social support among inmates. Women & Criminal Justice, 6(2), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1300/J012v06n02_04

- Haynie, D. L., Whichard, C., Kreager, D. K., Schaefer, D. R., & Wakefield, S. (2018). Social networks and health in a prison unit. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(3), 318–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146518790935

- Hochstetler, A., Murphy, D. S., & Simons, R. L. (2004). Damaged goods: Exploring predictors of distress in prison inmates. Crime & Delinquency, 50(3), 436–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128703257198

- Huggins, D. W., Capeheart, L., & Newman, E. (2006). Deviants or scapegoats: An examination of pseudofamily groups and dyads in two Texas prisons. The Prison Journal, 86(1), 114–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885505284702

- Jiang, S., & Winfree, L. (2006). Social support, gender, and inmate adjustment to prison life: Insights from a national sample. The Prison Journal, 86(1), 32–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885505283876

- Jones, R. S. (1993). Coping with separation: Adaptive responses of women prisoners. Women & Criminal Justice, 5(1), 71–97. https://doi.org/10.1300/J012v05n01_04

- Kamarck, T. W., Manuck, S. B., & Jennings, J. R. (1990). Social support reduces cardiovascular reactivity to psychological challenge: A laboratory model. Psychosomatic Medicine, 52(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199001000-00004

- Kelman, J., Gribble, R., Harvey, J., Palmer, L., & MacManus, D. (2022). How does a history of trauma affect the experience of imprisonment for individuals in women’s prisons: A qualitative exploration. Women & Criminal Justice, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2022.2071376

- Kreager, D. A., & Kruttschnitt, C. (2018). Inmate society in the era of mass incarceration. Annual Review of Criminology, 1, 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092513

- Kreager, D. A., Young, J. T. N., Haynie, D. L., Bouchard, M., Schaefer, D. R., & Zajac, G. (2017). Where ‘old heads’ prevail: Inmate hierarchy in a men’s prison unit. American Sociological Review, 82(4), 685–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417710462

- Kruttschnitt, C., Gartner, R., & Miller, A. (2000). Doing her own time? women’s responses to prison in the context of the old and the new penology*. Criminology, 38(3), 681–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2000.tb00903.x

- Kruttschnitt, C., & Gartner, R. (2003). Women’s imprisonment. Crime and Justice, 30, 1–81. https://doi.org/10.1086/652228

- Liebling, A., & Arnold, H. (2012). Social relationships between prisoners in a maximum security prison: Violence, faith, and the declining nature of trust. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(5), 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2012.06.003

- Lindorff, M. (2000). Is it better to perceive than receive? Social support, stress and strain for managers. Psychology, Health &, 5(3), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/713690199

- Lindquist, C. H., & Lindquist, M. C. A. (1997). Gender differences in distress: Mental health consequences of environmental stress among jail inmates. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 15(4), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0798(199723/09)15:4<503::AID-BSL281>3.0.CO;2-H

- Listwan, S. J., Colvin, M., Hanley, D., & Flannery, D. (2010). Victimization, social support, and psychological well-being. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(10), 1140–1159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854810376338

- McEwen, B. S. (2005). Stressed or stressed out: What is the difference? Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 30(5), 315–318.

- McEwen, B. S. (2012). Brain on stress: How the social environment gets under the skin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(Suppl 2), 17180–17185. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1121254109

- Messina, N., & Grella, C. (2006). Childhood trauma and women’s health outcomes in a California prison population. American Journal of Public Health, 96(10), 1842–1848. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.082016

- Owen, B. (1998). Struggle and survival in a women’s prison. State of New York University Press.

- Owen, B., Wells, J., & Polluck, J. (2017). In search of safety: Confronting inequality in women’s imprisonment. University of California Press.

- Patel, M., Ryan, A., & Herrera, S. (2022). Exploring friendship experiences among incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women: A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. Women & Criminal Justice, 32(4), 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2021.1885569

- Pearlin, L. I., Menaghan, E. G., Lieberman, M. A., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22(4), 337–356. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136676

- Plugge, E., Douglas, N., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2008). Imprisoned women’s concepts of health and illness: The implications for policy on patient and public involvement in healthcare. Journal of Public Health Policy, 29(4), 424–439. https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2008.32

- Pollock, J. M. (2002). Women, crime, and prison. Wadsworth.

- Porter, L. C. (2019). Being ‘on point’: Exploring the stress-related experiences of incarceration. Society and Mental Health, 9(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869318771439

- Propper, A. (1982). Make-believe families and homosexuality among imprisoned girls. Criminology, 20(1), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1982.tb00452.x

- Ricciardelli, R. (2014). Coping strategies: Investigating how male prisoners manage the threat of victimization in federal prisons. The Prison Journal, 94(4), 411–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885514548001

- Schnittker, J., Massoglia, M., & Uggen, C. (2012). Out and down: Incarceration and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(4), 448–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146512453928

- Seeman, T. E. (1997). Price of adaptation–allostatic load and its health consequences. MacArthur studies of successful aging. Archives of Internal Medicine, 157(19), 2259–2268. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1997.00440400111013

- Seeman, T. E., Singer, B. H., Ryff, C. H., Love, G. D., & Levy-Storms, L. (2002). Social relationships, gender, and allostatic load across two age cohorts. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(3), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200205000-00004

- Seplaki, C. L., Goldman, N., Weinstein, M., & Lin, Y. (2006). Measurement of cumulative physiological dysregulation in an older population. Demography, 43(1), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.0009

- Sered, S., & Norton-Hawk, M. (2013). Criminalized women and the healthcare system: The case for continuity of services. Journal of Correctional Health Care : The Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 19(3), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345813486323

- Severance, T. A. (2005). You know who you can go to’: Cooperation and exchange between incarcerated women. The Prison Journal, 85(3), 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885505279522

- Steiner, B., & Wooldredge, J. (2009). Individual and environmental effects on assaults and nonviolent rule breaking by women in prison. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 46(4), 437–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427809341936

- Steiner, B., Ellison, J. M., Butler, H. D., & Cain, C. M. (2017). The impact of inmate and prison characteristics on prisoner victimization. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015588503

- Steptoe, A. (2000). Stress, social support and cardiovascular activity over the working day. International Journal of Psychophysiology : Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 37(3), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00109-4

- Sykes, G. (1958). The society of captives: A study of maximum-security prisons. Princeton University Press.

- Thoits, P. A. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53–79. Extra issue: Forty years of medical sociology: The state of the art and directions for the future. https://doi.org/10.2307/2626957

- Trammell, R. (2009). Relational violence in women’s prison: How women describe interpersonal violence and gender. Women & Criminal Justice, 19(4), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974450903224246

- Travis, J., Western, B., & Redburn, S. (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences. National Institute of Justice.

- Wang, X., Cai, L., Qian, J., & Peng, J. (2014). Social support moderates stress effects on depression. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-8-41

- Wilks, S. E. (2008). Resilience amid academic stress: The moderating impact of social support among social work students. Advances in Social Work, 9(2), 106–125. https://doi.org/10.18060/51

- Wolff, N., & Shi, J. (2009). Victimization and feelings of safety among male and female inmates with behavioral health problems. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 20(sup1), S56–S77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940802710330

- Wolff, N., & Shi, J. (2011). Patterns of victimization and feelings of safety inside prison: The experience of male and female inmates. Crime & Delinquency, 57(1), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128708321370

- Wolff, N., Blitz, C., Shi, J., Siegel, J., & Bachman, R. (2007). Physical violence inside prison: Rates of victimization. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(5), 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854806296830

- Wolff, N., Vazquez, R., Frueh, B. C., Shi, J., Schumann, B., & Gerardi, D. (2010). Traumatic event exposure and behavioral health disorders among incarcerated females self-referred to treatment. Psychological Injury and Law, 3(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-010-9077-9

- Wooldredge, J. D. (1998). Inmate lifestyles and opportunities for victimization. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 35(4), 480–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427898035004006

- Wooldredge, J., & Steiner, B. (2016). Assessing the need for gender-specific explanations of prisoner victimization. Justice Quarterly, 33(2), 209–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2014.897364

- Wulf-Ludden, T. (2013). Interpersonal relationships among inmates and prison violence. Journal of Crime and Justice, 36(1), 116–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2012.755467

- Yang, C., McClintock, M. K., Kozloski, M., & Li, T. (2013). Social isolation and adult mortality: The role of chronic inflammation and sex differences. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54(2), 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146513485244

- Young, J. T. N., & Haynie, D. L. (2022). Trusting the untrustworthy: The social organization of trust among incarcerated women. Justice Quarterly, 39(3), 553–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2020.1807588

- Zamble, E., & Porporino, F. (1990). Coping, imprisonment, and rehabilitation: Some data and their implications. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854890017001005