Abstract

This qualitative study involved interviews with staff in a women’s prison to explore their suggestions about parenting education. Interviews were conducted to identify whether staff agreed with previous parenting education suggestions made by women experiencing incarceration and contribute to developing a parenting education program. Data were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis. Staff highlighted the importance of accommodating complex needs, cultural safety, trauma-informed, woman-centred and a strengths-based approach. This approach to program development will contribute to a parenting education program designed for women experiencing incarceration and may support program sustainability attributing to the involvement of the prison community in program design.

INTRODUCTION

The number of incarcerated women worldwide has increased nearly 60% since the year 2000 and at a much higher rate than men in prison, increasing by 22% over the same period. Nearly 7% of the worldwide prison population are women and girls which equates to greater than 740,000 experiencing incarceration (Fair & Walmsley, Citation2022, p. 2).

With the increasing worldwide rate of women in prison, attention to the gendered needs of women has become more apparent. The gendered needs of women experiencing incarceration has been described as the “triumvirate”, which includes three contributing factors, comprising of a history of victimization, the use of substances to self-medicate for the trauma of past victimization and mental illness, with a higher occurrence of self-harm for women compared to men (Bartels et al., Citation2020). Many of these women have cumulative disadvantage with experiences of multiple traumas, abuse, sexual abuse, domestic violence, poverty and childhood trauma (Carlton & Segrave, Citation2014; Enggist et al., Citation2014; Jewkes et al., Citation2019; Segrave & Carlton, Citation2011; Stathopoulos, 2012). Some of the effects of trauma can contribute to difficulty coping with daily stressors, forming healthy relationships, managing cognitive processes (memory, attention, thinking, emotional regulation) and can impact spiritual beliefs. Neuro-biological effects can manifest in hyper-vigilance, constant aroused state, withdrawal, and avoidance (SAMHSA (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration), Citation2014). Women born abroad may experience additional barriers which can lead to isolation, discrimination and exclusion (Watt et al., Citation2018). In Australia Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women are the fastest growing population of incarcerated people ([ABS],Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2019). These women represent 33% of the women in prison, in Australia (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare [AIHW], Citation2020, p. 4). These statistics represent the ongoing impacts of Australia’s colonial history and the forced removal of children from Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander families causing devastating effects (AIHW (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare),), Citation2018; Baldry, Citation2009; Baldry & McCausland, Citation2009; Tilton & Anderson, Citation2017).

A growing body of literature recognizes the importance of a gendered approach to programming for incarcerated women (Bartels et al., Citation2020; Bloom et al., Citation2004; Wright et al., Citation2012). The gendered approach takes into consideration the reality of women’s lives which can impact the choice of the environment, the staff, program development, content and material (Bloom et al., Citation2004). Evidence suggests that addressing the realities of the lives of incarcerated women through gender-responsive policy and practice is essential to improving outcomes for women (Bloom et al., Citation2004). Culture has also been recognized as important and needs to be considered in the development of programs (Brown & Bloom, Citation2009; Henson, Citation2020).

The majority of women in prison are mothers, a recent report recorded 54% of women in prison have responsibility for at least one child in the community (AIHW (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare), 2020, p. 10) and 85% of women have been pregnant at some stage in their life (AIHW (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare), Citation2019, p.72). Therefore, the majority of women in prison are a caregiver of children and their incarceration can have a traumatic and long-term effect on the child and themselves (WHO, 2014). Possibly the separation of mother and child is “the single greatest punishment of incarceration” for many women (Stone et al., Citation2017, p. 304). The love that a mother has for her child can be a powerful motivator for women in prison to work toward positive change (Kennedy et al., Citation2020).

A large proportion of women will leave prison and re-offend after a short period in the community (Russell & Baldry, Citation2020). Women often experience short or remand sentencing, consequently limiting access to rehabilitation programs and disrupting family stability (Baldry, Citation2010; Lloyd et al., Citation2015; Stathopoulos et al., Citation2012). Because of this high proportion of women serving short or remand sentences, there is limited time to engage in education (Russell & Baldry, Citation2020). It is important to develop programs specific to the needs of women experiencing incarceration and conducive to the prison environment (Abbott et al., Citation2018).

If women are provided with an opportunity to attend parenting education when their motivation is high, potentially women, their families and communities can experience positive changes (Eddy et al., Citation2022). Many parenting programs conducted with incarcerated women have demonstrated positive short-term impacts (Bell & Cornwell, Citation2015; Collica- Cox & Furst et al., 2018; Kamptner et al., Citation2017; Loper & Tuerk, Citation2011; Scudder et al., Citation2014; Simmons et al., Citation2012). Parenting programs evaluated with women in prison have demonstrated increased knowledge (Kennon et al., Citation2009; Urban & Burton, Citation2015; Wilson et al., Citation2010) and significant improvement in parenting attitude (Kennon et al., Citation2009; Miller et al., Citation2014; Perry Citation2009; Rossiter et al., Citation2015; Simmons et al., Citation2012; Wilson et al., Citation2010). Other studies have described better communication and relationships with their children after attending parenting education in a prison (Bell & Cornwell, Citation2015; Collica-Cox & Furst, Citation2018; Perry Citation2009).

Parenting programs previously implemented in a prison setting vary in content, theory and program length. Similarities in content include topics for example, relationships with the child and caregiver, communication, listening, child discipline, emotional regulation and child development (Lovell et al., Citation2020). However, a challenge when introducing parenting education in a prison setting is a lack of understanding about parenting education and insufficient encouragement by staff for women offenders to attend parenting programs (Newman et al., Citation2011; Schram & Morash, Citation2002). This lack of understanding could result from insufficient staff consultation during the development and implementation of prison programs.

This paper presents views of prison staff regarding the parenting education needs of women in prison. The prison staff interviews reported here are part of a research project to develop a parenting program for women experiencing incarceration. The project utilized a community-based theoretical model (Badiee et al., Citation2012). Community is defined as a “unit of identity” and can comprise multiple communities (Israel et al., Citation2005). In the current project, the “community” included women experiencing incarceration with varied cultural backgrounds including Aboriginal women, prison staff and key members of the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander community. Prior to project commencement women in the prison acknowledged the need for a parenting education program for women in prison separated from their children. The community was engaged in developing the program, which started by listening to the voices of women experiencing incarceration (Lovell et al., Citation2020). It was important to understand the different needs of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women (in press). Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander parenting practices vary across Australia and within communities, however, the core strengths are applicable to current parenting and can be incorporated into parenting education (Geia, Citation2012; Kruske et al., Citation2012; Malin et al., Citation1996; Penman, Citation2006).

Prison staff, as part of the community, took part in interviews following on from interviews with women in prison. Interviewing the women first enabled researchers to establish if the staff had similar, or opposing, views to the views and suggestions made by the women. During interviews, staff had the opportunity to contribute their ideas and establish a vested interest in the development of a parenting education program. Staff interviews were conducted to determine if the staff agreed with the women’s suggestions. The purpose of the interview was not to make changes to suggestions that women had made but to recognize barriers in the prison environment that may need to be addressed to support the women. It was also important to collaborate with various prison staff members to gain insight and knowledge from their experience of working with women in a prison setting. Durlak and DuPre (Citation2008) state that community collaboration should not be underestimated in the process of developing and implementing a successful and sustainable program.

The current research study provides insight into the views of prison staff regarding the parenting education needs of women. It addresses the views and suggestions of staff working in a women’s prison:

To identify whether the staff agreed with the parenting education needs and suggestions made by women experiencing incarceration

To contribute to the development of a parenting education program for women experiencing incarceration who are separated from their children

To contribute to program sustainability with the involvement of the prison community.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Location

The study took place in an Australian women’s prison that employs approximately 200 staff working for the Department for Correctional Services (DCS) and Prison Health Services. Staff from both sectors were interviewed. The DCS employs a General Manager for the site, security officers, managerial and support staff, psychologists and social and emotional support services.

Participants

All prison staff who had direct contact with the women in the prison were invited via an email sent from an administrator in the prison to participate in an interview. A poster advertising the research was circulated on an internal communication system. To participate, the staff were asked to make contact via email with BL or the administrator. This recruitment method facilitated voluntary participation and reduced the risk of coercion from direct line managers. Participants were eligible if they worked on-site at the prison and had knowledge or an interest in parenting education which was determined by the participants. Five participants were previously known to BL through initial stages of project collaboration. Limited participant data was collected to maintain anonymity.

This study involved fifteen interviews with participants who were required to work onsite at the women’s prison. Nine staff worked in prison health and consisted of health and managerial staff. The health staff had worked at the prison between seven months and twelve years. The six staff members from the DCS comprised managerial staff and front-line workers, including officers, psychologists and social workers. These staff had worked at the prison between six months and thirteen years. Most participants interviewed were female and no participants withdrew from the research.

Data collection

A naturalist approach aimed for the researchers to understand the experiences of staff working with women experiencing incarceration (Given, Citation2008). The naturalist approach features the understanding that individuals are experts in their life experiences (Carl & Ravitch, Citation2018). At the time of the interviews, COVID-19 was not in the community, however, entry into the prison was restricted. It was planned that data would be collected via focus group interviews. However, because of the subsequent COVID-19 restrictions the researchers were unable to enter the prison and therefore data were collected via semi-structured telephone interviews, and one participant requested a face-to-face interview in the community. The participants were sent information electronically about the study and a verbal explanation prior to the interview. Participants agreed and written consent was obtained. Interviews were conducted by (BL) and audio-recorded with participant consent. This researcher identifies as a Caucasian female, middle-class and an outsider to the prison setting, who brought experience caring for women as a health professional. She holds beliefs that with opportunity and support, women experiencing incarceration can recover.

Most staff interviewed (n = 12) were located at the prison during telephone interviews and situated in a private room. Three participants were not located at the prison during the interview. One staff member was working from home, one opted to take part after work hours and another took part in a face-to-face interview outside of work hours, in a private space. Interviews were conducted at convenient times to encourage information sharing (Burke & Miller, Citation2001). Telephone interviews can be effective in collecting rich data, encourage free flowing conversations and enable participants to speak with honesty and a level of anonymity (Given, Citation2008).

The interviews lasted an average time of approximately sixty minutes. Interviews began with questions such as: Do you think a parenting program would be beneficial for women? What type of content would you like to see included? What do you see as the challenges? The questions were followed by presenting suggestions the women experiencing incarceration had made in previous interviews, to establish whether the staff agreed with the women (Lovell et al., Citation2022). Prior to this study, focus group interviews were conducted with 31 women in prison, including 13 Aboriginal women and 5 women born overseas. The women were asked about their parenting education needs to co-design a parenting education program specifically for their needs. Data were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). During interviews, the staff were given an opportunity to elaborate and share what they felt was relevant. Researchers agreed the fifteen interviews had achieved an in-depth understanding (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021) of staff suggestions about the educational needs of the women in prison. A summary of the interview transcript was emailed to participants to increase the credibility of the interpretation by enabling participants to refute or confirm the accuracy of interpretation of the data (Candela, Citation2019). Only one participant made minor adjustments to ensure the reader knew the statements were not a generalization toward all women.

Data analysis

The data were transcribed verbatim by BL, shortly after conducting the interviews. Data were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2014, Citation2022). To align with naturalistic inquiry, the data were analyzed inductively to identify meaning within the data and uncover new ideas or information that could contribute to the development of a parenting education program (Armstrong, Citation2010). Deductive coding was also applied using a trauma-informed framework to understand staff awareness of the trauma-informed approach and identify ways to incorporate the approach into the program (see ). Deductive coding was also used to establish whether the staff agreed with the needs women had discussed in earlier interviews. Data analysis was guided by six phases (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2014). The transcripts were read multiple times and useful aspects of the interviews were highlighted, as well as words relating to trauma and the trauma-informed approach using the principles listed in . The trauma-informed principles take into consideration: safety; trustworthiness; peer support; collaboration; empowerment, voice and choice; and cultural, historical and gender issues. Each transcript was summarized by (BL). Some initial ideas and thoughts were noted during the process. Transcripts were uploaded to NVivo 12.6.0 software to support coding considerable amounts of data. Data summaries were composed by (BL) and read by (MS). Raw data was coded by BL and AB independently to enable detailed discussion of the data and establish themes. Codes included both semantic (self-care, guilt) and latent codes (woman-centred, strengths-based) using a relativist perspective. BL and AB had similar codes and interpretation of the data and met to discuss and finalize the themes. Some codes were deleted or merged during the coding process when transcripts were re-read. Similar codes were grouped together to establish themes. Themes were defined, named, re-named and re-ordered. The transcripts were re-read after themes were developed to ensure staff had been represented accurately.

Table 1. Principles of a trauma-informed approach (SAMHSA (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration),), 2014).

RESULTS

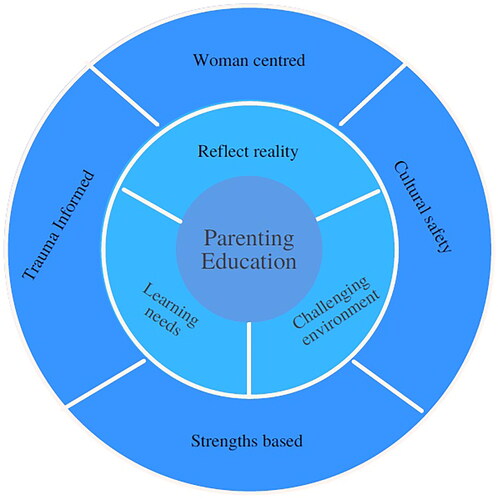

During data analysis four themes were established: (1) ‘Reflecting reality, whilst maintaining a strengths-based approach to education – a delicate balance’, (2) ‘The underpinnings of a prison parenting education program’, (3) ‘Working to support the engagement and learning needs of women experiencing incarceration’, (4) ‘Striving for sustainability – working within a challenging environment’. visually represents the themes and the underpinning frameworks for program development.

Reflecting Reality, Whilst Maintaining a Strengths-Based Approach to Education – a Delicate Balance (Theme 1)

The staff all confirmed that women would benefit from a parenting education program and highlighted some complexities women might face as a mother living in prison. Staff expressed the importance of including information relevant to the women, to reflect the complexity of their lives. During interviews some staff realized how many aspects of the women’s lives impact parenting, “I think it’s a balance too, on how do you paint that picture of the reality, of parenting, and still be able to hold on to them and keep them, do you know what I mean?” (Participant 4). The staff recognized the difficulty of accommodating all the complex needs.

In the interviews, the women experiencing incarceration discussed the need for information about Child Protection and although the staff agreed that having some information about Child Protection would be helpful, they knew that it could trigger difficult emotions. “I think they would recognize it in a story perhaps, even if they can’t recognize it in their own life, but it might be too close to home for some of them” (Participant 6). Child Protection applies to many of the women. However, the staff were aware this information should be delivered using a strengths-based approach. The staff commented about the possibility of eliciting shame with certain topics, “shame can be such a barrier to them authentically engaging in treatment or programs or rehabilitation” (Participant 10).

A number of staff discussed how children were affected by their mother’s incarceration and the feelings children might experience. This point was similar to findings from interviews with the women who were aware their children were suffering and wanted guidance to support their needs and identified anger as a common emotion. The women experienced stressful situations with their children, which would be difficult from a distance. One staff member provided an example of a difficult situation, “fifteen-year-old girl keeps staying away for the night and she’ll [Grandmother] ring her daughter in prison and say “I can’t find her, she’s missing” and so mum’s stressing. Oh yeah, it’s so complex” (Participant 3). The availability of parenting education could provide women with a place to seek support and guidance. This guidance could include a discussion of topics such as how to cope with a child who is running away from home or other complex situations that may present.

The women in the prison discussed having their photograph taken and sending it to their children, so their children could see they were healthy and safe. Most staff agreed with including this activity, nevertheless, some staff wondered why women would want to send a photograph of themselves. Other staff worried it would not be allowed and one staff member thought it might be quite upsetting for some children.

There are other kids that would get that photo and scream and rip it up and be very angry and potentially see it as a sign that mum, that all mum cares about is herself and so it is very complex, very individual. (Participant 10)

The staff highlighted the need to adopt an empathetic woman-centred approach and provide women with options to make decisions, for example, to decide who they send the photograph to, or to keep the photograph. Although for most women it was important to connect with their children, several staff discussed that some children would no longer want contact with their mother.

Most staff agreed that women needed to develop skills to look after themselves before they could care for their children, which was identified by the women. The staff agreed women needed to heal and develop skills to cope with life and parenting, “It’s about healing yourself and repair yourself, before you can reach out to somebody else and that’s really good that they recognize that” (Participant 7). Staff highlighted that substance use is a problem for many women and needed to be addressed to enable them to parent their children after release.

When there’s a lot of drug abuse involved, they aren’t even aware of the fact that they are a danger to their children, or their children are in danger because they have been neglected because you know addiction is addiction and it’s overwhelming and it’s their first love really and when they get in the grip of it. (Participant 8)

Despite the concerns about drug addiction, staff suggested that reference to drugs should be limited to basic information, as the focus should be on parenting. The women interviewed had suggested learning skills to give them alternative strategies to turn to rather than self-medicating with drugs.

The staff were concerned about the impact of family violence and ensuring the women understood the potential consequences for their children, even if their children had not experienced physical violence. One staff member reiterated what some women might say about the impact of family violence on their children,

‘Nobody ever hurt the kids’, but the kids are sitting there watching it – almost building that empathetic attunement with the child, rather than seeing them as umm, I guess, an entity that doesn’t have desires and feelings and grief and all that kind of stuff. Which are all very big topics [laugh]. (Participant 10)

Therefore, it was suggested that women may benefit from learning about the effect of family violence on children and the importance of protecting children from physical, sexual, emotional, and verbal abuse.

Several staff discussed that guilt can be a problem for the women who expressed their experiences with guilt. One staff member described how guilt can be used in a positive way: “Guilt actually being a really good thing, in terms of motivating change, motivating self-development, and I guess pushing us to do things better” (Participant 10). Viewing guilt as an indicator of the need to change could be a helpful concept for women to understand and support them in dealing with intense feelings and avoid the cycle of shame. Viewing guilt positively aligns with the strengths-based foundation of a trauma-informed approach.

Some staff recognized the need to include basic information or life skills in a parenting program as they recognized the impact that poor parenting in childhood can have on the next generation.

I just want to say, smacking your kids in the head, that is not okay, so it is actually not okay to smack your kid in the head. It’s not okay to leave needles around the house, so some prisoners, it is actually that basic, but the other prisoners have such amazing insight. (Participant 10)

The staff discussed the lack of positive role models in the lives of the women and life skills they may have missed during their own childhood. For example, “They had to look after their selves and help tidy it up, and an officer had just given her a mop and a bucket, and she didn’t know what to do with it” (Participant 7). These examples highlight the basic level of information that some women may require. This information would need to be provided using a strengths-based approach rather than focusing on the problems.

The staff discussed the traumatic childhood that many women experience and the impact this may have on their judgment of healthy parenting. “Like maybe they were abused as a child, or not loved or locked in the room or things like that you know, and you need to clarify that, that is not the right parenting” (Participant 15). The staff discussed the need for simple explanations to make it clear what was and was not acceptable when parenting.

The Underpinnings of a Prison Parenting Education Program (Theme 2)

Several staff had ideas and thoughts about the foundation of a parenting program and discussed what would be important to underpin the program. These ideas were about a trauma-informed approach, the concept of not being the ‘perfect mother’, attachment, addressing cultural safety and a strengths-based approach. Most staff agreed that the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women should be offered their own group and their cultural needs should be incorporated into the program. “It would have to be culture sensitive to the Aboriginal women as well, and to do an Aboriginal parenting program you would have to involve the Aunts and the Aboriginal people as well” (Participant 3). The staff acknowledged the importance of involving Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples in the development of a parenting program as they recognized that Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women may have specific cultural needs and parenting styles. Previous parenting programs conducted in the prison had not reflected the culture of participants and focused on young children. One staff member commented, “It was footage from an American website or something like that and it was really, it didn’t really resonate really well with the women, but I guess as far as content goes it was also really young child related” (Participant 12). Lack of cultural relevance, as well as a focus on young children in previous parenting programs, was an issue affecting participation and program sustainability.

Some staff recognized that women may have issues with attachment and relationships and require support to understand attachment. The staff were aware that a facilitator would need to be mindful not to shame or trigger the women whilst separated from their children, which makes forming and continuing attachment with children a challenge. “They haven’t had that nurturing and that attachment and bonding and normal, what you can call “normal” childhood and having that parenting program, it’s sort of, it’s helping them to be able to break the cycle” (Participant 3).

One staff member mentioned that Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) might be beneficial to include in a parenting education program: “It would be ideally trauma-informed, DBT-informed parenting skills program – that’s how I see it” (Participant 14). This staff member suggested the importance of a trauma-informed approach, recognizing that most women in the prison had experienced trauma. Some staff suggested the concept of not needing to be the ‘perfect mum’. This concept could help the women deal with guilt and not be overwhelmed by aiming for perfection. However, one staff member recognized the importance of making sure the women understand what an acceptable level of ‘good enough’ parenting is: “Their version is, "I only went on a meth bender three times this week and my child only had to clean up my vomit twice” umm …” (Participant 10). Without adequate explanation, the ‘good enough’ mother could be interpreted the wrong way, especially for those who have not been exposed to role modeling of acceptable parenting. Staff highlighted challenges faced by mothers experiencing incarceration and many conveyed an understanding of the trauma experienced. Staff were supportive of the development of a parenting program and agreed a program would benefit many women.

Working to Support the Engagement and Learning Needs of Women Experiencing Incarceration (Theme 3)

Potential challenges with engagement in the learning environment were discussed. The staff discussed ways to engage and support women from their experiences of working with women. Several staff considered the need to accommodate women with difficulty concentrating. The staff acknowledged that many women have accessed and experienced a low level of education and could have literacy challenges, which would need to be considered throughout the program.

Some staff gave an insight into how they tried to show understanding and build trust with women in the past. One staff member described how she tried to get a woman to see that she could have made a similar mistake when she was growing up:

Actually normalizing that yeah, it’s a pretty f***ing hard job to be a parent and removing some of that stuff of ‘us’ versus ‘them’, kind of thing and talking to prisoners – ahh actually when I was a teenager, I did some pretty stupid things and it just so happens that I had the resources to get my life back on track and not happened to be intoxicated and drive a car and kill someone and stayed at a party and went on a bender and that kind of stuff. (Participant 10)

The staff commented about the importance of an appropriately trained facilitator who understands the needs of women experiencing incarceration. One staff member stated, “someone really well skilled to be able to … identify the nuances and complexities” (Participant 5). Another staff member discussed feedback provided by the women after attending a parenting program previously conducted in the prison, “Some of their feedback was that it was run by women who didn’t have babies and didn’t understand what it was like to have kids and no real concept of what it meant to be a mum in prison” (Participant 12). This highlights the need for understanding the realities of the lives of these women.

One staff member discussed the importance of listening and learning from the women and focusing on the individual needs of the women,

“You read that out of a bloody textbook didn’t you miss, I’ll tell you how it really is” and it’s like. I’m so sorry, please tell me, yes you are correct, please tell me, teach me and having that openness. (Participant 3)

The women need people who understand and support them in a way that reflects the reality of their lives, a woman-centred approach. Facilitators need to listen with an open mind and promote unconditional regard that recovery is possible. During interviews a male staff member suggested having a male facilitator who could role model positive behavior and provide a father’s viewpoint but thought it would not be appropriate for a male to facilitate a whole program for women.

A few staff discussed the importance of keeping boundaries within the group to ensure the group remains focused on the topic.

Keep it very much about the group and the topic and not individual cases and what happened to them and how bad that was or and you know like, and it was someone’s fault and that kind of thing, so like you can have discussions but with some firm boundaries. (Participant 1)

One staff member thought it would be a good idea to have an enrollment form to gauge how the women might feel about participating with women who have differing levels of access to their children. Other staff thought it would be appropriate to have women with differing levels of child contact in the same group. Some staff acknowledged the difficulty of getting women to attend a program. “When we run programs generally the high functioning people attend programs. The low functioning ones don’t attend so how do we and they are probably the ones that need it more than the other people” (Participant 12). Staff explained that when women are mandated to attend, they can exhibit problematic behavior that changes the group dynamic and affects the women who genuinely want to engage. However, if a program is voluntary, women may choose not to attend and therefore may miss the opportunity.

Striving for Sustainability – Working within a Challenging Environment (Theme 4)

During interviews prison staff described some challenges that may affect implementation and program sustainability. The staff contributed ideas of how these challenges may be overcome in a system where many barriers exist. Several staff agreed that offering a parenting program would be an opportunity to educate women serving a short sentence. One staff member described the throughput of women and the impact this has on programming engagement.

We’ve got at any given time 40–45% on remand and about 50% of women are serving sentences of 30 days or less and 80% of them are serving sentencing of 6 months or less. So again, it’s that kind of movement through the system that makes it really hard. (Participant 14)

One challenge is that women who are serving short periods of time in custody (remand or sentenced) make up a large proportion of the women and this small window of opportunity requires consideration. The impact of short sentencing was identified by the women interviewed previously and staff discussed that women are regularly moved within the prison. This movement restricts the continuation of participation in a program because the women in differing security levels cannot interact. Several staff suggested that individual modules within a program might be beneficial to accommodate the movement of women and their short sentences. One staff member suggested continuation of education even if women had been released from prison. Having the ability to complete parenting education in the community or return to the prison after release would support women serving short sentences to continue their engagement with education and create continuity of support and collaboration between the community and prison.

In the past, the prison has relied on community organizations to facilitate parenting education. This reliance meant the content of parenting education was not specific to the prison context and one problem was continued funding to sustain programs ‘We are still very much relying on external providers which mean we kind of have very little control over what is delivered and the consistency of delivery’ (Participant 14).

Some staff commented on the attitude of officers who conveyed a punitive way of thinking. This punitive approach was sometimes reflected in removing time for the mother and child to connect, due to a behavioral infraction. During one interview, a staff member showed an awareness of the trauma such actions may cause a woman and her child/ren and the need for officers to have alternative ways to manage challenging behavior. ‘It’s not just the prisoner that suffers from those kinds of punitive approaches, you know, supporting officers to understand that.’ (Participant 10). This staff member was aware of the impact this punitive approach may have on the children and thought it was unfair the child had to suffer because the mother had made a mistake and was promoting a trauma-informed, family-centred approach.

A few staff could not empathize with women about missing their child’s birthday, for example. The staff had witnessed that many women were released into the community and their return to prison, multiple times. ‘It’s like well, why did you do what you’ve just done anyway? If you hadn’t have done anyway, if you hadn’t of done what you did, you wouldn’t be here’ (Participant 9). This viewpoint oversimplifies the challenges women face after release and lacks understanding of the intersectionality of their journeys that often lead to a return to prison. This attitude could limit the support that some staff can provide for women when they are experiencing distress, particularly whilst missing special moments in the lives of their child/ren and family. This attitude also shows the need for staff to understand the link between a woman’s psychosocial history and her criminal behavior.

A few staff mentioned the lack of opportunity for empowerment within the prison system, ‘The system is really good at removing choices, removing the ability to be whoever they are, not empowering them to do much – so umm can we fix that?’ (Participant 12). One principle of a trauma-informed approach is empowerment. Attending a parenting program could provide women with some opportunities where they could experience empowerment by making decisions, reflecting on their strengths, and planning for the future. Many staff agreed the prison was not the right environment to delve deeply into resolving trauma and suggested a strengths-based approach that acknowledges the trauma that women have experienced and provides support to take steps toward a positive future.

I think often they can recognise that they don’t want to repeat what happened to them, but they don’t know how to materialise it. So, I think that will be what the program will be about, building the resilience in them because we can’t undo the sadness, but we can just acknowledge it and try and give them the skills to move forward with that sadness. (Participant 1)

If they touch on sensitive things the girls will get very upset and they are in a prison environment so that is one thing to be aware of, and if it brings up past trauma, it’s not a good environment to have a breakdown. (Participant 15)

Several staff members identified the importance of avoiding re-traumatizing the women, which aligns with a trauma-informed approach. Sustainability is a key component of successful programming and was noted by the staff as a problem in the past. Identifying the challenges within the system collaboratively could help plan for a sustainable program in the future.

DISCUSSION

This study contributes to the limited evidence exploring the views and experiences of prison staff concerning women’s parenting education needs whilst incarcerated. This study confirmed that prison staff were supportive of implementing a parenting education program in the prison. Staff mostly agreed with suggestions the women had made about topics for inclusion in a parenting education program, identifying some of the potential challenges that would need to be addressed. Some staff viewed the women as self-centered for wanting to send a photo of themselves to their children or learn about self-care. Most staff acknowledged the need for women to care for their health and wellbeing to enable them to care for their children. Some staff suggested the focus should remain on parenting and other topics should be a smaller component, such as domestic violence, substance abuse and self-care, which the women had identified as requiring support to address. Nevertheless, the literature points to the need for parenting education to be multimodal, incorporating other needs and parenting (Armstrong et al., Citation2017). Most staff highlighted the importance of a strengths-based, trauma-informed approach where the intersectionality of the women is accommodated.

Interviewing the staff in the prison was important to contribute to the development of a parenting program. It is envisaged that gaining contribution from the staff promoted vested interest and may contribute to sustainability of the program. Nevertheless, staff turnover is a challenge, as many of the staff interviewed have now moved roles or organizations. Allocating a program champion could assist in the maintenance and sustainability of the program (Durlak & DuPre, Citation2008). Sustainability will also require building community capacity and shared goals, and for the community to recognize positive outcomes from the intervention (Hacker et al., Citation2012).

Implications for Program Design

During interviews the staff outlined challenges women may experience in a learning environment and offered insight into ways to effectively communicate and establish trust and rapport. Staff agreed that a craft activity would be positive to incorporate in a parenting program. An earlier study reporting on interviews conducted with facilitators of prison parenting education found that craft activities were beneficial for participants, giving them time to discuss parenting in a relaxed way whilst providing an opportunity for praise, group cohesion and a sense of satisfaction (Fowler et al., Citation2018).

One staff member highlighted the concept of the ‘good enough’ mother, which was presented by Winnicott in the 1950s. The concept of not being a perfect parent is still valid today (Othman et al., Citation2022). However, providing clear guidance about what this means in practical terms would need to be addressed for women who have not experienced a nurturing childhood. An underpinning message – that parents do not need to be perfect – can reduce feelings of guilt and negative emotion and present as a strengths-based approach.

Most staff interviewed were aware of the impact of trauma on the women and understood the importance of building trusting relationships. However, some staff were unable to consistently apply a trauma-informed understanding, as their responses showed a lack of empathy for women returning to prison multiple times, some unable to empathize with the women missing their children. This undercurrent of punitive values shows the need to be selective about the staff who facilitate programs and may indicate a need for further staff training. Many staff responses showed an understanding about the trauma history or challenging childhoods the women experienced and acknowledged that the prison environment was not the right place to delve deeply into trauma. Elements of a trauma-informed approach were discussed by the staff, including the importance of a strengths-based approach, addressing cultural differences, empowering women, and creating a safe learning environment with a non-judgmental approach.

The role of a parenting education facilitator would require an understanding of the trauma women often experience, and the application of a trauma-informed approach to education. Discussing parenting can be triggering for any parent but particularly for women who are separated from their children. This situation creates a delicate balance between providing information relevant to the complexity of their lives, in a way that does not re-traumatize the women. Where possible, the program would need to center on the women’s strengths, include cultural safety and align with a trauma-informed, gendered approach as suggested by Bartels et al. (Citation2020) and Kezelman and Stavropoulos (Citation2020). The focus of parenting education would not include wrongdoings of the past, but how to move forward in a positive direction. For an organization to be trauma-informed, the culture of all work practices and environments need to reflect a trauma-informed approach (Jewkes et al., Citation2019). To achieve a trauma-informed organization it would be helpful to align with a rehabilitation model, rather than a punitive approach (Wright et al., Citation2012). The success of a trauma-informed approach in a prison environment is controversial as certain aspects of the system directly oppose this approach (Jewkes et al., Citation2019). However, with the rising rate of women experiencing incarceration (Walmsley, Citation2016), change is needed.

The staff agreed that Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women would benefit from having a designated group, facilitated by an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander woman. The presence of another Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander woman during education can have a significant impact on creating feelings of safety, confidence and reducing shame for Aboriginal peoples (Innovative Research Universities, Citation2011). The Australian Law Reform Council (ALRC) recommend Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples are involved in the development and facilitation of programs (ALRC (Australian Law Reform Commission),), Citation2018). It is important that the ALRC recommendations are transferred into practice to support Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women, who are now one of the fastest growing groups experiencing incarceration (ABS (Australia Bureau of Statistics),), 2019). It is also important to aim for parenting education that is culturally appropriate and safe for participants and is included as part of an evaluation. In the past, attending to cultural differences has been highlighted as a missing component of prison parenting education and evaluation (Brown & Bloom, Citation2009; Fowler et al., Citation2018; Henson, Citation2020).

Implementation

The interviews highlight the importance of having a skilled facilitator to conduct parenting education in a prison setting, although staff were unsure who would be suitable and available for the role. Facilitators would need in-depth knowledge about current best practices for parenting. Parenting education programs conducted in prison settings in the past have mostly reported a co-facilitation model, with several programs employing psychologists for the role (Kamptner et al., Citation2017; Kennon et al., Citation2009; Miller et al., Citation2014; Scudder et al., Citation2014). One study reported co-facilitation with a psychologist and a woman experiencing incarceration, trained for the facilitation role (Loper & Tuerk, Citation2011). A facilitation role for women residing in prison may have many benefits and for sustainability of a program, and ongoing funding can be an issue which was highlighted as a potential problem in this study. The staff communicated the importance of having a facilitator who could relate to the women in prison and understand their complex needs. The facilitator would need to have the ability to quickly build trust and rapport, to engage with the women and encourage continued attendance. Many factors can influence attendance and having a facilitator who acts as a role model and support person could have a significant impact on the women.

Program attrition has been reported as a problem in previous studies where prison parenting education has undergone evaluation and requires careful planning to retain participants (Loper & Tuerk, Citation2011; Miller et al., Citation2014; Perry, Citation2009). Program attrition can be affected by transfers within prison and women being released from prison due to short or remand sentencing (Miller et al., Citation2014). A previously published study suggested individual modules could provide women with short sentences exposure to some education and provide a re-cap of information from the previous session to assist those who miss a session (Miller et al., Citation2014). Similar suggestions were made by the staff interviewed in this study. A connection with a community organization, where women can seek similar services in the community, may be more beneficial and has been identified as helpful in previous studies (Frye & Dawe, Citation2008; Shortt et al., Citation2014). An earlier study reported that a useful resource was the creation of written parenting information using simple language to supplement parenting education and address the needs of incarcerated parents (Miller et al., Citation2014).

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

A strength of this study were the in-depth, honest, conversational style interviews which enabled the prison staff to share their knowledge and experience working with women in prison and participate in the design of the parenting program. A cross section of staff from corrections and health were included in the study. Limitations of the study were that staff not interested in parenting education for women in prison were not captured. Presented are the views from a sample of staff from one prison, in Australia who were mostly women. The limited participant data collected in order to maintain anonymity may reduce the transferability of the findings to other settings.

The views of the staff and women reflect the need to provide the women with a chance to learn more about parenting as well as how to support their children in positive ways. Sustainability and acceptance of a parenting education program may be increased through engaging the community with program development (Israel et al., Citation2005). However, bringing together the criminal justice system and parenting education may be problematic due to their conflicting foundations. As parenting education moves away from control and punishment toward teaching and understanding, in time it is possible the prison system could move in the same direction, founded on a trauma-informed approach. The staff in this study showed a willingness to move toward a trauma-informed approach for parenting programs, as many of the staff recognized the impact trauma has on the women and the benefit of supporting women to connect with their children and family.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval was granted from the University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (Application ID: 204060) and Central Adelaide Local Health Network Human Research Ethics Committee (Application ID: 13320). Approval was also gained from the Department for Correctional Services Research and Evaluation Management Committee.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. The views expressed therein are those of the authors and not necessarily the Department for Correctional Services in South Australia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the Department for Correctional Services and South Australian Prison Health. This research would not have been possible without the opportunity to hear their views and experiences. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Department for Correctional Services in South Australia.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Identifiable material was removed from the data collected however, it is possible that indirectly identifiable information could be gathered from the raw data and therefore data sets will not be shared.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Abbott, P., Lloyd, J. E., Joshi, C., Malera‐Bandjalan, K., Baldry, E., McEntyre, E., Sherwood, J., Reath, J., Indig, D., & Harris, M. F. (2018). Do programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people leaving prison meet their health and social support needs? The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 26(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12396

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). (2018). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Stolen Generations and descendants: Numbers, demographic characteristics and selected outcomes. Cat. No. IHW 195. AIHW. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/stolen-generations-descendants/contents/table-of-contents

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2019). The health of Australia’s prisoners, 2018. Cat.no. PHE 246. AIHW. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/2e92f007-453d-48a1-9c6b-4c9531cf0371/aihw-phe-246.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2020). The health and welfare of women in Australia’s prisons. Cat.no. PHE 281. AIHW. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/32d3a8dc-eb84-4a3b-90dc-79a1aba0efc6/aihw-phe-281.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- ALRC (Australian Law Reform Commission) (2018). Pathways to justice: Inquiry into the incarceration rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Commonwealth of Australia. Final Report No. 13. ALRC. https://www.alrc.gov.au/publication/pathways-to-justice-inquiry-into-the-incarceration-rate-of-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples-alrc-report-133/

- Armstrong, J. (2010). Naturalistic inquiry. In J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of research design. (pp. 881–885). Thousand Oaks: Sage Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412961288

- Armstrong, E., Eggins, E., Reid, N., Harnett, P., & Dawe, S. (2017). Parenting interventions for incarcerated parents to improve parenting knowledge and skills, parent well-being, and quality of the parent–child relationship: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14(3), 279–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-017-9290-6

- ABS (Australia Bureau of Statistics) (2019). Prisoners in Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/prisoners-australia/2019

- Badiee, M., Wang, S. C., & Creswell, J. W. (2012). Designing community-based mixed methods research. In D. K. Nagata, L. Kohn-Wood & L. A. Suzuki (Eds.), Qualitative strategies for ethnocultural research. (pp. 41–59). Washington, USA: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13742-003

- Baldry, E. (2009). Home safely: Aboriginal women post-prison and their children. Indigenous Law Bulletin, 7(15), 14–17.

- Baldry, E. (2010). Women in transition: From prison to…. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 22(2), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2010.12035885

- Baldry, E., & McCausland, R. (2009). Mother seeking safe home: Aboriginal women post-release. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 21(2), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2009.12035846

- Bartels, L., Easteal, P., & Westgate, R. (2020). Understanding women’s imprisonment in Australia. Women & Criminal Justice, 30(3), 204–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2019.1657550

- Bell, L., & Cornwell, C. (2015). Evaluation of a family wellness course for persons in prison. Journal of Correctional Education (1974), 66(1), 45–57.

- Bloom, B., Owen, B., & Covington, S. (2004). Women offenders and the gendered effects of public policy. Review of Policy Research, 21(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2004.00056.x

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept. For thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can "thematic analysis" offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 26152–26152. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: a practical guide. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, M., & Bloom, B. (2009). Reentry and renegotiating motherhood: Maternal identity and success on parole. Crime & Delinquency, 55(2), 313–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128708330627

- Burke, L., & Miller, M. (2001). Phone interviewing as a means of data collection: Lessons learned and practical recommendations. Forum, Qualitative Social Research, 2(2), 1–8.

- Candela, A. G. (2019). Exploring the function of member checking. The Qualitative Report, 24(3), 619–628. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3726

- Carl, N., & Ravitch, S. (2018). Naturalistic inquiry. In B. Frey. (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation. (pp. 1134–1137). Thousand Oaks California. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506326139

- Carlton, B., & Segrave, M. (2014). They died of a broken heart’: Connecting women’s experiences of trauma and criminalisation to survival and death post-imprisonment. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 53(3), 270–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12066

- Collica-Cox, K., & Furst, G. (2018). Implementing sucessful jail-based programming for women: A case study of planning, parenting, prison and pups – Waiting to “Let the dogs in”. Journal of Prison Education and Reentry, 5(2), 101–119. https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jper/vol5/iss2/4/

- Collica-Cox, K., & Furst, G. (2019). Parenting from a county jail: Parenting from beyond the bars. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(7), 593–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1565877

- Durlak, J., & DuPre, E. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

- Eddy, J. M., Martinez, J. C. R., Burraston, B. O., Herrera, D., & Newton, R. M. (2022). A randomized controlled trial of a parent management training program for incarcerated parents: Post-release outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084605

- Enggist, S., Møller, L., Galea, G., Udesen, C. (2014). Prisons and health. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/128603

- Fair, H., Walmsley, R. (2022). World female imprisonment list (5th ed.). Women and girls in penal institutions, including pre-trial and detainees/remans prisoners. World Prison Brief Issue. https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_female_imprisonment_list_5th_edition.pdf

- Fowler, C., Dawson, A., Rossiter, C., Jackson, D., Power, T., & Roche, M. (2018). When parenting does not “come naturally”: Providers’ perspectives on parenting education for incarcerated mothers and fathers. Studies in Continuing Education, 40(1), 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2017.1396449

- Frye, S., & Dawe, S. (2008). Interventions for women prisoners and their children in the post-release period. Clinical Psychologist,12(3), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284200802516522

- Geia, L. K. (2012). [First steps, making footprints:Intergenerational Palm Island families’ Indigenous stories (narratives) of childrearing practice strengths]. [PhD thesis]. James Cook University.]. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/25465/

- Given, L. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry. In L. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. (pp. 548–550). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.n280

- Hacker, K., Tendulkar, S. A., Rideout, C., Bhuiya, N., Trinh-Shevrin, C., Savage, C. P., Grullon, M., Strelnick, H., Leung, C., & DiGirolamo, A. M. (2012). Community capacity building and sustainability: Outcomes of community-based participatory research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 6(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2012.0048

- Henson, A. (2020). Meet them where they are: The importance of contextual relevance in prison-based parenting programs. The Prison Journal, 100(4), 468–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885520939294

- Innovative Research Universities (2011). Indigenous voices teaching us better. http://indigenousvoices.cdu.edu.au/support.html

- Israel, B. A., Eng, E., Schulz, A. J., & Parker, E. A. (2005). Methods in community-based participatory research for health. (1st ed.) Wiley.

- Jewkes, Y., Jordan, M., Wright, S., & Bendelow, G. (2019). Designing “healthy” prisons for women: Incorporating trauma-informed care and practice (TICP) into prison planning and design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203818

- Kamptner, N. L., Teyber, F. H., Rockwood, N. J., & Drzewiecki, D. (2017). Evaluating the efficacy of an attachment-informed psychotherapeutic program for incarcerated parents. Journal of Prison Education and Reentry, 4(2), 62–81. https://doi.org/10.15845/jper.v4i2.1058

- Kennedy, S. C., Mennicke, A. M., & Allen, C. (2020). ‘I took care of my kids’: Mothering while incarcerated. Health & Justice, 8(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-020-00109-3

- Kennon, S. S., Mackintosh, V. H., & Myers, B. J. (2009). Parenting education for incarcerated mothers. Journal of Correctional Education, 60(1), 10–30.

- Kezelman, C. A., Stavropoulos, P. (2020). Organisational guidelines for trauma informed service delivery. Blue Knot Foundation. National Centre of Excellence for Complex Trauma. https://www.blueknot.org.au/Resources/Publications/Practice-Guidelines/Organisational-Guidelines

- Kruske, S., Belton, S., Wardaguga, M., & Narjic, C. (2012). Growing up our way: The first year of life in remote Aboriginal Australia. Qualitative Health Research, 22(6), 777–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311432717

- Lloyd, J. E., Delaney-Thiele, D., Abbott, P., Baldry, E., McEntyre, E., Reath, J., Indig, D., Sherwood, J., & Harris, M. F. (2015). The role of primary health care services to better meet the needs of Aboriginal Australians transitioning from prison to the community. BMC Family Practice, 16(1), 86–86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0303-0

- Loper, A. B., & Tuerk, E. H. (2011). Improving the emotional adjustment and communication patterns of incarcerated mothers: Effectiveness of a prison parenting intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(1), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-010-9381-8

- Lovell, B., Brown, A., Esterman, A., & Steen, M. (2020). Learning from the outcomes of existing prison parenting education programs for women experiencing incarceration: a scoping review. The Journal of Prison Education and Reentry, 6(3), 294–311.

- Lovell, B. J., Steen, M. P., Brown, A. E., & Esterman, A. J. (2022). The voices of incarcerated women at the forefront of parenting program development: a trauma-informed approach to education. Health & Justice, 10(1), 21–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-022-00185-7

- Malin, M., Campbell, K., & Agius, L. (1996). Raising children in the Nunga Aboriginal way. Family Matters, (43), 43–47. https://aifs.gov.au/research/family-matters/no-43/raising-children-nunga-aboriginal-way

- Miller, A. L., Weston, L. E., Perryman, J., Horwitz, T., Franzen, S., & Cochran, S. (2014). Parenting while incarcerated: Tailoring the strengthening families program for use with jailed mothers. Children and Youth Services Review, 44, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.06.013

- Newman, C., Fowler, C., & Cashin, A. (2011). The development of a parenting program for incarcerated mothers in Australia: A review of prison-based parenting programs. Contemporary Nurse, 39(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2011.39.1.2

- Othman, S., Steen, M., Wepa, D., & McKellar, L. (. (2022). Examining the influence of self-compassion education and training upon parents and families when caring for their children: A systematic review. The Open Psychology Journal, 15(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2174/18743501-v15-e221020-2022-39

- Penman, R. A. (2006). The “growing up” of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children: A literature review. Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2006-11/apo-nid4397.pdf

- Perry, V. (2009). Evaluation of the mothering at a distance program, NSW Department of Corrective Services. https://correctiveservices.dcj.nsw.gov.au/download.html/documents/research-and-statistics/Evaluation-of-the-Mothering-at-a-Distance_Program.pdf

- Rossiter, C., Power, T., Fowler, C., Jackson, D., Hyslop, D., & Dawson, A. (2015). Mothering at a distance: What incarcerated mothers value about a parenting programme. Contemporary Nurse, 50(2-3), 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2015.1105108

- Russell, S., Baldry, E. (2020). The booming industry continued: Australian prisons. A 2020 update. https://www.cclj.unsw.edu.au/sites/cclj.unsw.edu.au/files/The%20Booming%20Industry%20continued%202020.pdf

- Schram, P. J., & Morash, M. (2002). Evaluation of a life skills program for women inmates in Michigan. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 34(4), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1300/J076v34n04_03

- Scudder, A. T., McNeil, C. B., Chengappa, K., & Costello, A. H. (2014). Evaluation of an existing parenting class within a women’s state correctional facility and a parenting class modeled from parent-child interaction therapy. Children and Youth Services Review, 46, 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.08.015

- Segrave, M., & Carlton, B. (2011). Women, trauma, criminalisation and imprisonment. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 22(2), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2010.12035887

- Shortt, J. W., Eddy, J. M., Sheeber, L., & Davis, B. (2014). Project home: A pilot evaluation of an emotion-focused intervention for mothers reuniting with children after prison. Psychological Services, 11(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034323

- Simmons, C. W., Noble, A., & Nieto, M. (2012). Friends outside’s positive parenting for incarcerated parents: An evaluation. Corrections Today, 74(6), 45.

- Stathopoulos, M., With Quadara, A., Fileborn, B., Clark, H. (2012). Addressing women’s victimisation histories in custodial settings (ACSSA Issues No. 13). Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, Australian Institute of Family Studies. https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/i13.pdf.

- Stone, U., Liddell, M., & Martinovic, M. (2017). Incarcerated mothers: Issues and barriers for regaining custody of children. The Prison Journal, 97(3), 296–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885517703957

- SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) (2014). SAMHSA’s concepts of trauma and guidance for a trauma informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

- Tilton, E., Anderson, P. (2017). Bringing them home 20 years on: An action plan for healing. https://healingfoundation.org.au/app/uploads/2017/05/Bringing-Them-Home-20-years-on-FINAL-SCREEN-1.pdf

- Urban, L., & Burton, B. (2015). Evaluating the turning points curriculum: A three-year study to assess parenting knowledge in a sample of incarcerated women. Journal of Correctional Education, 66(1), 58–74.

- Walmsley, R. (2016). World female imprisonment list. Institute of Criminal Policy Research and Birbeck. https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_female_prison_4th_edn_v4_web.pdf

- Watt, K., Hu, W., Magin, P., & Abbott, P. (2018). “Imagine if I'm not here, what they’re going to do?”: Health‐care access and culturally and linguistically diverse women in prison. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 21(6), 1159–1170. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12820

- Wilson, K., Gonzalez, P., Romero, T., Henry, K., & Cerbana, C. (2010). The effectiveness of parent education for incarcerated parents: An evaluation of parenting from prison. Journal of Correctional Education, 61(2), 114–132.

- Wright, E. M., Van Voorhis, P., Salisbury, E. J., & Bauman, A. (2012). Gender-responsive lessons learned and policy implications for women in prison: A review. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(12), 1612–1632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854812451088