ABSTRACT

In this paper, we dwell amongst what was agitated from enacting Neimanis' (2012) hydrofeminism in an ‘aqueous-body–writing–reading’ experiment that unfolded in discrete but entangled locations (London and Cape Town) to actively disrupt and reformulate ideas about what it is to do scholarly work. We consider how we might dislodge anthropocentric ways of knowing, being and doing through our swimming–writing–reading. Aligned with emergent hydrofeminist scholarship, our unruly writing experiment has – over 7 months of alternating seasons on two continents – involved exchanging, diffracting and curating words that e/merge together. The multiple, interwoven stories told in this paper are a direct challenge to what and how knowledge gets produced, by whom, where and for what purposes. Working with wit(h)nessing; contact zones; and radical openness, our speculative, enmeshed, multispecies praxis offers glimpses into the possibilities that exist in porous spaces to generate knowledge differently in the spirit of hopeful renewal.

Emergence of an anti-extractivist Praxis

In this paper, we tell stories: the story of how this piece came about; stories of the intraconnectionsFootnote1 between swimming–writing–readingFootnote2; stories of hopes for renewal from the depths of the Anthropocene and what this might mean for feminist scholarship and the field of gender and education. To tell these stories, we share glimpses into our praxis that are attempts to make more tangible the ways that feminist swimming–writing–reading differs from other forms of knowledge production. Central to our project has been a commitment to articulate sensibilities that are core to our experiment with different ways of doing and being ‘an academic’. This has been a strange, vulnerable, joyous and at times exhilarating journey that has shifted and mutated how we encounter politics, ethics, ontology and epistemology through everyday, often quotidian watery encounters. This emergent praxis has demanded generosity, curiosity, delight and wonder in an openness to indeterminacy, and care-full engagement with that which we share, dwell upon and grapple with as we embrace the (non)sense of life in late capitalism.

A snatched one

A clipped one

A bootleg

[…]

[…]

[…]

Silverlimbed

I rise.

Polished by the last light. Flash of back and cheek.

I rise and run back into time from

The snatched one

The clipped one

The bootleg

Still playing

(from Swims by Burnett Citation2019)

Ours is a deliberately anti-extractivist praxis that tries to get away from the mastery of authoritative interpretations to a more receptive approach that is not in pursuit of what can be plundered, gained, accomplished or capitalized upon. Our aqueous–writing–reading dwells upon and within a reciprocal becoming-with that does not shy away from the complexities of colonial heritages or the logics of neoliberal individualism. Entangling global North, (the Ladies Pond in Hampstead Heath, England) with global South (tidal pools and oceanic depths around Cape Town, South Africa) our hydrofeminist praxis, shaped in and across these contexts, contributes to rethinking gender and education. It is by taking watery lives, watery selves and watery practices to the heart of our seriously playful (Haraway Citation2008; Citation2016) research praxis that we attempt to disrupt and displace neoliberal imperatives that determine what educational research should be. Our hydrofeminist scholarship is a form of activism that refuses to be contained and confined to the ivory towers of knowledge production. Instead, it articulates the significance of embodied, messy, everyday, watery encounters that open up generative possibilities for reimagining what scholarly practices might be, how they get produced and the difference they make. Our experimental and indeterminate project entails that which we could not predict but that somehow found us – this has demanded that we explore with both bravery and vulnerability. We consider our praxis with the un/known to be a feminist act of wit(h)nessing.

Wit(h)nessing

Wit(h)nessing is only possible if one is feeling part of the world. Louise Boscacci (Citation2018, 343) describes wit(h)nessing as: ‘A bodily encounter with shared earth others – kin, commensal, prey predator – is always an encounter-exchange if we think with the concept and mattering of wit(h)nessing’ [emphasis in the original]. She refers to the visual artist, psychoanalyst and affect theorist Ettinger (Citation2005), who invented the neologism wit(h)nessing to give expression to the process of co-poiesis or co-becoming, where there is no independent subject ‘I’ or object ‘non-I’ which pre-exist relationships.

As becoming-wit(h)nesses in our praxis of terraqueous reading–swimming–writing, we are never disinterested and impartial observers. Rather, our praxis is a performative ethology of learning to risk affecting and being affected (Snaza Citation2019) and, as Haraway (Citation2016) notes, being for some worlds rather than for others. Such praxis involves considering what must be taken into account, what can be excluded or neglected and being unsettled by our recurrent attunement to the hauntologyFootnote3 (Derrida Citation1994) of our implicatedness in past and present violences of ecological damage through colonialism, marked by the privileges of whiteness (Ferdinand Citation2022; Ghosh Citation2021; Wilson Citation2019).

Our immersive reading–writing–watery–wit(h)nessing practices require attentive attunement, what Haraway (Citation2016) and Despret (Citation2004) refer to as an attentive politeness – noting what matters and is meaningful for multispecies ways of being on the current damaged planet. Acknowledging both temporal and spatial diffraction – where spectres of past beings and doings impact on the geopolitics of continents on which we now reside, enables the cultivation of an ability to respond by looking back and forward in the thick now of entangled past, present and futures (Barad Citation2012). Such response-ability calls for an openness to both standing (or swimming) as witness and actively bearing witness or giving testimony to the significant presence of earthly, oceanic or watery others (van Dooren and Rose Citation2016). Our praxis involves sharing and responding to each other’s presence in the thickness of encounters in a Google.doc – poems, photographs, thoughts from swims and readings shared – to bring into proximity a flavour of the traces of our wit(h)nessing encounters in our local watery worlds:

Wit(h)nessing a heron swoop to snatch a duckling from an orderly line of siblings, throwing it to the back of his throat as he soars into the sky;

Wi(t)nessing the ‘infestation’ of blue green algae as the water temperature rises;

Wit(h)nessing a group of virile drakes in pursuit of a lone hen;

Wit(h)nessing a new nylon rope barrier installed to protect the crumbling bank from swimmers’ limbs;

Wit(h)nessing the metallic odour of H2O ripe with HRT, e-coli, viruses and chlorophyll;

Wit(h)nessing the cacophony of parakeets atop the trees; an ‘invasive species’ in need of ‘control’;

Wit(h)nessing bodily transformations through on-going sympoiesis;

Wit(h)nessing balls of human hair blocking the drains;

Wit(h)nessing the string of hay-filled plastic bottles to protect a nest;

Wit(h)nessing multiple modes of existence and ways of co-becoming in the world;

Wit(h)nessing featherduster worms retracting in response to human bodies swimming too close;

Wit(h)nessing baboon mothers with babes clinging to stomachs foraging in rubbish bins;

Wit(h)nessing multiple hermaphrodite sea hares coupling with their spaghetti-like eggs spattered in tight clumps amongst the green and brown algae;

Wit(h)nessing the moon cycles and their effects on the ocean, the tides, the weather;

Wit(h)nessing golden shimmers skittering crossing seascapes through sunrises and sunsets;

Wit(h)nessing the forgotten neoprene boots lining the changing room wall;

Wit(h)nessing the same glossy crow swoop up to his perch in a high oak tree;

Wit(h)nessing ecological possibility arising from, sustained within, webs of enabling relationships shaped by loss and hope.

Wit(h)nessing in the contact zone

Contact zone, a concept developed by postcolonial scholar Mary Pratt (Citation2008, 8), is generative for our hydrofeminist praxis as it draws attention to spaces where ‘cultures, meet, clash and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out in many parts of the world today’. Haraway (Citation2008, 102) extends contact zone to spaces and practices in which humans interact with non-human others: ‘subjects are constituted in and by their relations to each other (…) it treats the relations … in terms of copresence, interaction, interlocking understandings and practices’. For Haraway, the process of knowledge production and inquiry is inseparable from the environment in which the process occurs, which includes the specific non-humans who are either present or whose lives are at stake in the knowledge-making process. Wilson (Citation2019) proposes contact zones can draw attention to waterscapes where different forms of knowledge, technology, people, elements and non-human life grapple with each other in conditions of uneven power. Inspired by this, we mobilize contact zone as a critical tool of analysis in our multispecies scholarship to raise questions about practices of knowledge-making and uneven structures of power in our postcolonial contexts.

This thing that we do: surface skittering

Kenwood Ladies Pond, in North London, England (51°33′47″N 0°09′25″W) has long been the subject of feminist writing and storytelling (see edited collection by Moggach Citation2019). A deep dive into the Kenwood Ladies Pond Association archivesFootnote4 reveals it to be a curious place that over time has persisted in being full of contradictions, complexities, uncomfortable histories, tales of both inclusion and exclusion. As a women-only space, it has a special status; revered as a sanctuary, a safe space where photography is prohibited; a political site of both feminist unities and divisions (Kertudo Citation2018). The current and ongoing debate about trans-inclusivity rumbles on and poses important questions about hospitality and belonging (Smith Citation2019). Archival searches and contemporary literature on and about the pond indicate that prevailing discourses framing life at this waterscape are inherently anthropocentric ().

The main debates centre around which (human) bodies are welcome, which (human) bodies fit, which (human) bodies are tolerated. Transphobia is not the only criticism waged against some pond goers; the overwhelming and persistent white, middle-classness associated with the pond is noted (Cosslett Citation2020; Kertudo Citation2018). There are also debates about the encroachment of capitalism as the pond has become increasingly commercialized and regulated where once it was free of charge and generally, more carefree. Nostalgic tales of hedonism and seclusion, nakedness and rebellion are not uncommon (see The Observer Citation2019). As ‘wild swimming’ has grown in popularity, the pond has become ever busier; the summer months require online pre-booking and a one-in-one-out queuing system that can sometimes last hours. Winter is a different story altogether – it is not unusual to be a lone human body in this icy body of water ().

Figure 2. Photo credit: The Financial Times, Citation2019.

The ‘Ladies’ Pond as the name proclaims, ‘belongs’ to human women. Other (non-human) bodies that constitute the pond community typically appear in literature, media and idle chatter as a biophilic backdrop; an ethnographic context where human city dwellers can reconnect with ‘nature’ and reap the health benefits of cold, open water swimming in a tree lined waterscape. The Ladies pond is known for its convivial sociability, the team of (once exclusively volunteer) lifeguards both regulate and host; maintain and police the space. Lunar events, solstices and equinoxes are all celebrated with floral decoration from the immediate hedgerows ().

An attunement with ‘nature’ is inferred by the generally rustic approach taken at the pond, although signs regulate human behaviour in the interests of environmental preservation. We are advised not to feed the ducks; to keep sandwiches tightly packaged to prevent the resident blind fox from helping himself; to refrain from using sunscreen and keeping a distance from the lily pads to preserve the quality of the water and the wellbeing of pond life. Whilst ponders are encouraged to be responsible, careful and respectful the space is ultimately ‘owned’ by The Corporation of London; a fee is charged and rules enforced.

Through our aqueous–reading–writing methodology, we have become more alert to multispecies relationalities, contradictions and conundrums as they persistently surface. Taking up this hydrofeminist praxis has activated an attunement to that which would have hitherto either gone unnoticed or fleetingly admired – now the most mundane sightings demand sustained attention and further excavation. Haraway’s (Citation2016) invitation to ‘stay with the trouble’ that comes from sympoiesis hails us daily. Our praxis, as it is registered within the expansive wordy pool of the Google.doc, offers tracings and mappings of the non-innocence of nature and the urgent need to trouble human/non-human relationalities. Reading (and re-reading) various works by Neimanis, Haraway, Bird Rose, Plumwood, Despret, Tsing and many others shifted how we encountered contact zones. We came to note and plug into the playfulness of birds, species specific idiosyncrasies that would have gone unregistered, the non-and-more-than-human hospitality extended to our pink fleshy bodies as we went visiting. The anti-extractivist approach to reading manifested as a different mode of encounter in the water, and afterwards in our writing. The ongoingness of our praxis makes it a way of life that folds back on itself and resurfaces when we least expect it ().

As van Dooren (Citation2016) stresses, multispecies communities require the cultivation of critical skills and observational capacities to make sense of others’ lives and actions that are often formed from risky connections, from which community unavoidably arises. The presence of humans in this watery community is complex; although declared the preserve of human ‘ladies’ the pond is in fact a multispecies ecology made up of thousands of creatures. Our praxis has underlined the imperative (inspired by van Dooren and Rose Citation2016) to ask – is it possible to inhabit space, to constitute community, otherwise? We must engage in persistent questioning – to test and to play in pursuit of (the always non-innocent) work of experimenting – with what else might be possible. Numerous entries within our shared writing space reveal the rich potential for SlowFootnote5 reading (Cixious Citation1991; Boulous Walker Citation2016; Bozalek Citation2017; Stengers Citation2018) to alter what happens in the water and what then resurfaces in writing and further thought. The ongoingness of taking seriously the non-human/human relationalities that unfold within watery communities have much to offer feminist modes of being and doing academia differently.

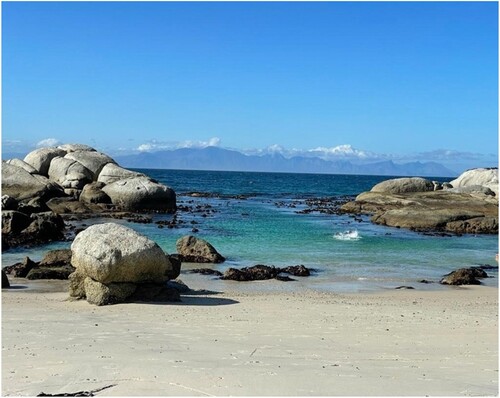

This thing that we do: deep dives

The Cape Town tidal pools and beaches have a haunted colonial and apartheid history. Windmill beach (S34°12.06’ E018°27.40’), a Marine Protected Area, where Viv swims and freedives, was the first Boer prisoner of war camp established in February 1900 called Belle Vue, where Afrikaans men were held hostage by British soldiers. These prisoners were initially held on ships in Simonstown and then moved to the Belle Vue camp above the bay, where a golf course has now been established, and where local residents walk their dogs in the early mornings and late afternoons. In 1901, there was a shark attack on one of the prisoners who died from the bites on his limbs. During the apartheid era, this beach was one of those reserved for people of colour ( and ).

Figure 5. Windmill Beach, 1900.

Note: https://www.angloboerwar.com/forum/prisoners-of-war/8942-cape-town-prisons#gallery-8.

The bay has a sandy base 8 metres deep and is popular for scuba and freediving and for teaching these activities. The adjacent bay, Boulders, was designated a Whites Only beach under the apartheid government, restricting people of colour from entering it, but is now a paying beach, run by the Table Mountain National Parks Board in Cape Town, which now excludes humans on a classed rather than a racialized basis. Boulders is a sheltered beach, protected from the wind by large granite boulders, which are 540 million years old (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boulders_Beach) – hence the name Boulders – and home to many terraqueous species such as the now endangered, African penguins. African penguins are also called ‘jackass penguins’ because of their distinctive donkey-braying call, which resounds around the environs. They are unafraid of human settlers and build nests in the nearby scrub-like other animals, they ‘compose with everything around them be it wind, water, other organisms or motions of plants’ as Vinciane Despret notes in her online video ‘Phonocene: Bird-singing in a multispecies world’ (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = U90M8rhQI6c&autoplay = 1&rel = 0&showinfo = 0) ().

The large rocks also provide shelter for invertebrate animals such as colourful nudibranches or sea slugs, cuttlefish and octopuses and their predators such as the pajama shark, as well as myriad other fish species ().

Although the area is protected, there are still strong surges and swells, which have to be assessed before diving into the ocean. The strong south easterly wind which brings the swells subsides somewhat in the winter months.

This part of the coastline is also home to the kelp forest or the Great African Sea Forest – which has become known and made popular through the Netflix film ‘My Octopus Teacher’ (https://www.imdb.com/title/tt12888462/). The holdfast of the kelp where it attaches itself to rocks is the holding place for so much life and small creatures. The roots are just there for anchoring – not for self-nourishment so becomes a rendering capable of many others ().

A hauntological, colonial and current entanglement of these contact zones where we swim and dive in the United Kingdom and South Africa is the unchecked extraction, expropriation, killing and destruction of aqueous animals of the ocean and its littoral zones (the so-called harvesting of whales, seals and seabirds and their eggs and excrement which was sent back to the colonies, particularly Britain). As Adrienne van Eeden-Wharton (Citation2020, A/W15) notes in her thesis Salt-water-bodies: From an atlas of loss:

‘from the 16th century onwards, the islands in Saldanha Bay and Dassen Island became the sites of the mass ‘harvesting’ (read: slaughter) of Cape Fur Seals, African Penguins and other seabirds.

Intermittent guano collection on the islands between the mid-17th to mid-19th centuries, escalated dramatically with the “guano rush” under British rule from the 1840s to early 20th century. … guano harvests were derived primarily from the deposits of Cape Cormorants and Cape Gannets, but included that of African Penguins and other cormorant species.

Sporadic whaling along this section of the coast by Dutch (and later British) settler-colonists, was followed in the late 18th century by an upsurge in unregulated commercial whaling with the arrival of large pelagic whaling ships from the United States, Britain and France’.

The omnicide which coincided with land dispossession, coercive labour practices which forced people off their land, making them dependent on settler-colonialists and the militarization and industrialization are all intertwined with the contact zones where we swim. The imperialist and local seismic surveys by companies such as Shell for oil and gas along the coastlines are forms of current conquests and further extraction and destruction of sea life. These harsh realities surface as spectres, leaking into the midst of the renewal and repair that we seek. We recognize the myriad ways which we have benefited and continue to benefit from the colonial extractivist project, and how disturbingly, in unseen ways, this enables the privilege to do this thing that we do.

Emergence of an interwoven anti-methodology

Like van Dooren and Rose (Citation2016), whose writing and thinking practices have developed through research encounters that involve sustained working together, we consider our locally situated swimming–writing–reading as contributions to the entanglement of feminism and post philosophies – particularly on what they might have to offer for the activation or enactment of alternative educational feminist imaginaries. For example, we consider how we might dislodge Anthropocentric ways of knowing, being and doing through our swimming–writing–reading. Aligned with emergent hydrofeminist scholarship (e.g. Neimanis Citation2012; Shefer & Bozalek Citation2022) our unruly writing experiment has – over 7 months, of alternating seasons on two continents – involved exchanging, diffracting and curating words that e/merge together (Skeet Citation2022). To date we have amassed 21, 417 words; spanning 116 pages; beginning with a poem; the pages are peppered with 113 photos captured above, below and around the water’s surface; hyperlinks to recorded lectures pop out here and there; reading recommended and shared (12 books; 3 theses; 32 articles); further poetry (our own and others); marginalia commentary that probably amounts to thousands and thousands more exchanged words; a film screeningFootnote6; a Netflix box seriesFootnote7; Attenborough documentariesFootnote8, and more besides …

Sharing frustrations and elations; inconveniences and despair

ebb-ing and flow-ing

sparking, flickering, provoking …

This ebb-ing and flow-ing inside a Google.doc, enlivened with Zoom meetings (where time zones were often misjudged); WhatsApp exchanges that couldn’t wait for the Google.doc; and Facebook posts; amounts to Slow processes (in terms of depth and quality rather than speed, see Bozalek Citation2021), but also sometimes stammering processes of exchange that have enabled us to become other sorts of academics, to curate spaces that are (almost) resistant to the neoliberal imperative for speed, mastery and efficiency. Permitting ourselves to get lost and be at sea in the processes, to pursue lines of enquiry without the burden of discovery; to swim amongst, within, beneath, through bodies of knowledge and speculation. The gifting exchanges in spaces (virtual, digital, porous, temporary, vulnerable spaces) might be thought of as an expanse of water capable of holding us. A reliance upon these floating, permeable, vast and unknowable bodies underline the fragility, temporal incongruence and dynamism of our indeterminate, shifting, emergent experiment.

At times we wondered at its enormity, the slippery mercurial quality of our shared wordy pool threatened to drown us. Not wishing to impose structure, order, meaning to what was taking shape we enthusiastically persisted with the ebb-ing and the flow-ing. It became a space and place characterized by generosity and trust, curiosity and care.

Visiting the Google.doc in anticipation of the gift of a new entry, perhaps with fresh images:

ducks, hauntings, octopus, conference, sunrise, memories, seafoam,

warm coffee, effluent, friendships, HRT patch,

drs appointments, cormorant, graffiti, covid,

sewage protests, coastal map; seahare,

beach huts, yoga, penguins, insomnia,

and, and and …

Poems sprang forth in surprising ways.

A few entries surfaced with bullet points, subheadings - where neoliberal demands for structure, knowability, desire for a clear output asserted pressure -

mercifully rare, quickly becoming obscured by

Marginalia

Hyperlinks

away from the pursuit of certainty to

myths, folklore,

more expansive ways to grapple with what we encountered through our swimming.

Early on we questioned whether what we were actually doing was indeed ‘swimming’. Dictionary definitions of swimming stress that it is an individual or team racing sport that requires the use of the entire body to move through the water. It is a low-impact activity with mental and bodily health benefits – it builds endurance, muscle strength and cardiovascular fitness. It is also good for weight-loss and fighting the ‘menopausal middle’ as endless algorithms never cease to remind us on social media. Our interest in doing what we do in the water does not align with such definitions, rather our watery praxis privileges bodily sensation, lightness, becoming-with watery feltness, smoothness, unpredictability, sighting spectacles, attuning to happenings, participating in world-making, relating to non-human/more-than-human others, entering into other-worldliness. These qualities are not only present when ‘doing what we do in the water’, rather informed by feminist posthumanism they leak into our academic and everyday lives. Affective encounters, capacities to become deeply immersed in the moment; corporeal encounters shaped by feltness occur both in and out of the water. ‘This thing that we do’ reaches far beyond an individualistic, Anthropocentric concern for human well-ness towards fusing connections and dwelling within and upon multispecies relationalities (Bird Rose, Despret Citation2022). Doing ‘what we do in water’ is felt as an immediate afterglow, which then morphs into an afterlife that comes from becoming-with waterscapes. We notice changes in body temperature, thoughts that ignite further thoughts, injuries, bites, stings, sticky residues (mud, kelp, salt, algae) – that seep into pores, sinews, tissues and bones – just as our watery bodies leach into the watery expanses leaving behind hair, hormones, skin, our DNA. This sympoiesis (Haraway Citation2016) generates an afterlife that settles to the dark, murky depths of the pond and the scummy surface of the ocean, bubbles up in dreams and imaginings, diffracts through readings and writings and ultimately finds ways into our aqueous-writing-reading methodology.

We also wonder if ‘writing’ was actually what we were doing. Bringing ‘what we do in water’ together with reading, in pursuit of writing an academic article, belies the capaciousness, the intricacies and complexities of these interwoven pursuits. Cixous (Citation1991) in her essay ‘Coming to Writing’ explains the intimate bond between reading and writing; she characterizes her writing as reliant upon attentive reading; a writing by ‘[s]he who looks with the look that recognizes, that studies, respects, doesn’t take, doesn’t claw, but attentively, with gentle relentlessness, contemplates and reads, caresses, bathes, makes the other gleam’ (Cixous Citation1991: 51). For Cixous we come to writing, when the capacities to read in this contemplative form are developed, which involves time, an unhurried approach, an attentive gaze and the curiosity to look back. As she asserts (op cit):

writing is deep in my body, further down, behind thought. Thought comes in front of it and it closes like a door. Whoever wants to write must be able to reach this lightening region that takes your breath away, where you instantaneously feel at sea and where the moorings are severed with the already-written, the already-known.

Our aqueous praxis makes apparent that swimming, or this thing we do in water, is enabled because of the reading that shapes our thoughts and heightens our sensitivity to the waterscapes of which we become a part, and the processual writing we do afterwards to think-with what seeps through our hydrological praxis. We invite playfulness into our readings, our watery encounters and our approach to writing. This involves conscious interventions into our habitual modes of being and doing, which we variously termed: disrupting habits of observation; experimenting with small differences; skittering on the surface and taking deep dives – into literature, into waterscapes and into writing – all of which came to characterize an emergent methodology. This involves challenging ourselves to embrace playful encounters, swimming with eyes shut, in reverse, weaving a path through life buoys, refusing to privilege optical wit(h)nessing; letting go of a sense of mastery and control to allow for processes of becoming-with waterscapes to be encountered in contact zones (Haraway Citation2008). We push ourselves to refuse reading watery encounters through Anthropocentric lenses. This spills over and becomes absorbed in our approach to both reading and writing. In the spirit of Cixous’ approach to reading, we embrace overruling the pretence of mastering things and knowing things in particular ways. Her approach circumvents the mastery of institutional reading structured by neoliberal, masculinist imperatives – to know at all costs. Instead reading, as an entangled affective practice moves us closer to moments of a love of wisdom and philosophy as a way of life (Boulous Walker Citation2016).

The Hundreds

As the ebb and flow of writing became more expansive, more excessive, an intervention was required. Inspired by Lauren Berlant and Kathleen Stewart’s The Hundreds we recognized a need to allow the words that were rapidly amassing to take on other shapes, to undertake different work. In The Hundreds, Berlant and Stewart (Citation2019) speculate on writing, affect, politics and the processes of world-making. They experiment with exchanging written pieces of one hundred words, no more. Berlant and Stewart (Citation2019) proclaim that this word constraint in writing amplifies the resonance of things within atmospheres and accentuates rhythms of encounter. They describe it as a training in absorption, attention and framing. This challenge of writing matter poems as 100-word exchanges aligns with the ambitions we had for our project, which is committed to playful experimentation, stripping down to the bare essence to heighten the feltness of aqueous encounters in various contact zones: our attempt to keep the event open. At first our entries are bloated and extravagant with words, but with care and patience they become sharper, leaner, more vivid. Berlant and Stewart (Citation2019) debate the potential for such experiments to convey encounters in contact zones – dwelling upon the specificity and locatedness – as well as attending to worldly connections and relationalities. They also assert that such a writing experiment is a means of being inconvenient to each other; as both authors are navigating worlding as existential territory that insists upon keeping one’s wits about them.

Our one hundreds are often in excess of the word constraint.

Our one hundreds often lack finesse.

Our one hundreds urge us to think with other one hundreds: swims, dives, laps, years, false starts, pages, poems, Zooms, anxieties.

Our one hundreds sometimes work in reverse.

Our one hundreds were open to being cut up.

Our one hundreds were not always only ours.

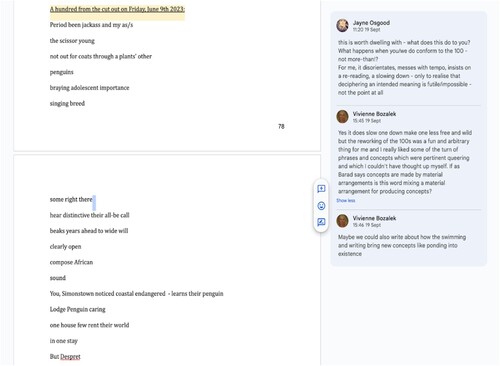

The figure below offers a partial glimpse at the messy, interwoven play of our aqueous–writing–reading praxis. The marginalia is as vital to the project as the hundreds and what they agitate. Allowing the process of cutting up (https://www.languageisavirus.com/cutupmachine.php) was a direct challenge to our human exceptionalism. The non-sense verses, such as the one below, that were generated from permitting ourselves to play with words (or words to play with us), with particular constraints and desires in mind, forced us into places of deep contemplation at material arrangements that are active in producing new concepts ().

Time spent in this creative milieu demands both deep immersion and surface skittering – which provides some sort of logic to frame our storytelling. Our slow curation of an aqueous-body–writing–reading affords a vital place for us to gift, to play, to provoke. Yet the feltness of neoliberal forces that insist that something concrete must come from our collaboration (i.e. a journal paper) at times suffocates, intervenes and steals both time and joy. We come to appreciate our inconvenient hydrofeminist praxis as refusal (Ahmed Citation2021; Berlant Citation2011; Campt Citation2017; Simpson Citation2017; Tuck and Yang Citation2014); by steeping ourselves in a different sort of academic doing that neither looks, feels, tastes, nor smells like business-as-usual we glide towards ways of resisting instrumentalist information extraction and mining. Immersing ourselves as bodies of water, in bodies of water in places shaped by colonial extractivism, disrupts tropes about ‘nature’ as a resource for humans; and ‘wild swimming’ as the key to wellness and mental stability. Feminist posthumanism and multispecies cosmologies invite more complex and confederate ways to reimagine our human place within the world. Generosity and hospitality (Despret Citation2016; van Dooren Citation2016) insist that we are part of the world (in all its messy complexity) rather than separate from it.

Radical openness

Our reading–swimming–writing is informed by a radical openness to enlivening explorations of thinking-with the intensities of terraqueous encounters, sometimes making us feel at sea, vertiginous in the lively indeterminism of the process. Our encounters with each other in the Zoom room and the Google.doc, with the readings we share with each other and our watery encounters, moving with human and non-human others in the swirls and eddies, rendering and being rendered capable, re-iteratively co-constitute us anew. Our experimental praxis provokes a thinking otherwise, unsettling old assumptions and at times bringing forth the as-yet-unthought through imaginative leaps. A welcome respite from the extractivist authoritative patriocolonial demands of contemporary academia.

Our extended period of reading–swimming–writing together/apart over 7 months has also developed patience for waiting, allowing time and space for trust to develop, pausing and hesitating, an acceptance of incompleteness, open-endedness and doubting, the time to re-turn to watery spaces, re-write and re-read, creating new habits in the interstices (Gibbs Citation2023) of the bustle and turmoil of academic and life demands.

Late August, the Ladies Pond, London

Back to familiar waters

Wearing a slightly darker skin

Peppered with mosquito bites

Plunge into silky familiarity

Gliding

Spectating

A gull floats by

Peering

Accusingly

To the left

A dozen ducks

Assumed female at first glance

Boisterous play

Flapping

Quacking

Posturing

On closer inspection

Teenage boys

Sparring

Colourful feathers detectable

The spared skittering ducklings of Spring

Have grown

This gull no longer a threat

The gull continues to glide alongside

Then darts to the bank

Emerges – crayfish in beak

A species thought to be an urban myth

Wit(h)nessed up close

I am taken back to Carol

The giant dead carp

Floating

Frightening

Alarming

Is this really the ladies pond?

‘Our’ pond?

Whose pond?

Community reliant upon

Webs of multispecies conviviality

(122 words, 5 emojis)

Reading and writing are ethical practices, as we are powerfully reminded by Deborah Bird Rose and Karen Barad, who do not only write about ethics, but who enact it in their scholarly praxis (Barad Citation2012; van Dooren and Chrulew Citation2022). Ethics is contextual, situated and relational, rather than residing in the mind of bounded finite human individuals who have already constituted identities. As we are co-constituted through multispecies encounters, our practice involves a curiosity and attunement to the strangeness of dynamic indeterminacy and that which exceeds, unsettles and troubles the anaesthesia of late and rampant cannibalizing capitalism (Fraser Citation2022), and its military–industrial complex. In this context, the urgency of cultivating a capacity for responsiveness to significant otherness in watery spaces and a sensibility of non-innocence to racialized coloniality and its role in ecocide and omnicide becomes foregrounded. Our reading–writing–swimming encounters alert us to the entanglement of seemingly separated and bounded geographical and historical watery spaces and times, and the ephemeral ongoingness of the racialized colonial project. And yet, within the context of such discomforting hauntologies, the hydrofeminist praxis remains a generous, generative, spontaneous, unruly, dynamic, playful engagement.

Towards hopeful renewalsFootnote9

The hydrofeminist praxis recounted throughout this paper has agitated alternative possibilities to contemplate and dismantle human exceptionalism and so make visible other ways to become-with murky, deep, wet, multispecies contact zones. Taking the residues and reverberations of our reading for a swim has cultivated opportunities for fresh sensibilities to form. As Boulous Walker (Citation2016: XV) states:

by engaging slowly, carefully and locally with the complex works that we read, by resisting the lure of ‘institutional’ readings, ones that reduce thought to information extraction or mining, we refuse or, at the very least, frustrate the modern technological drive that pillages thinking as a productive resource. Reading slowly and rereading, returning time and time again to read anew, we return, similarly, to the things in the world anew. Our slow and very local readings resist the all too familiar tone of those technological or instrumental readings that no longer share a relation with thought. (our emphasis)

Hydrofeminism offers possibilities to enact scholarship as a political form of hope-full renewal. We sought to find ways to enact Nietzsche’s (Citation1881/Citation1982) mode of being ‘with doors left open, with delicate eyes and fingers’. Laying bare the intricate processes involved in this hydrofeminist experiment our hope was to gift the reader with propositions and provocations that might contribute towards new educational imaginaries of how knowledge can be generated otherwise. As Haraway (Citation2018, 102) reminds us: ‘generative, effective multi-species environmental justice must be as much about play, storytelling, and joy as about work, critique and pain. Storytelling is a thinking practice, not an embellishment to thinking’.

This experimental writing–reading–swimming praxis offers a key to reclaiming and reconfiguring scholarly processes, output and impact by prioritizing it as a mode of feminist activism committed to making visible alternative ways of generating knowledge. Or as Zournazi (Citation2002) writes about hope, we might think of our praxis as

a spirit of dialogue, where generosity and laughter break open a space to keep spontaneity and freedom alive – the joyful engagements possible with others. For in any conversation – individual or political, written, spoken or read – there needs to be the ability to hear, listen and give.

We align with van Dooren (Citation2016) who argues that hope is praxis, never a feeling or psychological state but rather a project, a labour, never vague optimism. The praxis storied throughout this paper similarly asserts hope as something that must be worked at and shared with others if we are to cultivate ways to flourish in the ruins of capitalism. Our speculative praxis emerged without choreography and it remains endlessly unfinished, forever unfurling and has left us with an ongoing project in hope.

Acknowledgements

As a (post)thought to one of the main purposes of this article (which is what and how knowledge gets produced, by whom, where, and for what purposes), Vivienne would like to acknowledge a number of South African scholars whom she has been intra-acting with in reading-writing-swimming groups and whose ideas percolated with ours as we wrote this paper. In alphabetical order they are the late Elmarie Costandius, who died tragically in a car accident in January 2024, for the workshops inspired by her ideas at Boulders beach which led to writings on swimming-settler-yearnings on Windmill beach; Barry Lewis for his love of the kelp forest and ideas about home and the holdfast; Aaniyah Martin for her loving attentiveness in swimming and diving with me and teaching me so much about the sea and its creatures; Nasreen Peer for her research on the holdfast; Joanne Peers for sharing her family experiences of apartheid and her diffractive images of the Boer War camp on Windmill beach; Nike Romano for her work with Bracha Ettinger's concept of wit(h)nessing; Tamara Shefer and Nike Romano for taking forward the notion of hydrofeminism from a Southern perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jayne Osgood

Professor Jayne Osgood is based at Middlesex University, UK and holds a Professor II post at Innlandet University of Applied Sciences, Norway.

Viv Bozalek

Professor Vivienne Bozalek is based at University of Western Cape, South Africa.

Both authors work with posthumanist and feminist new materialist praxis.

Notes

1 We use the word intraconnections rather than interconnections following Karen Barad’s (2007) neologism intra-action which connotes the ontological inseparability of phenomena, such as reading–swimming–writing, rather than their pre-existing status.

2 We present our aqueous praxis inconsistently and interchangeably as ‘swimming–reading–writing’, ‘writing–reading–swimming’, ‘reading–writing–swimming’, ‘aqueous-body–reading–writing’, etc. to convey the ongoing intraconnections and symbiotic relationalities between these strands of activity.

3 Hauntology is a neologism coined by the French philosopher Jacques Derrida as a play on the word ontology, which sounds like hauntology in French.

4 The KLPA archive, including press cuttings, articles, papers, photographs, artwork, audio–visual material and artefacts reflecting the history of women swimming on Hampstead Heath from 1903 to the present day, is housed by the Bishopsgate Institute as part of its collection of archives of Feminist and Women’s History.

5 Slow, capitalised refers to a growing body of feminist scholarship that concerns a radical departure from neoliberal, instituted modes. It is a practice that privileges care, depth of attention and permission to dwell – Slow does not relate to the pace at which scholarship is undertaken.

6 Water Rats, a documentary film about The Hampstead Ponds during lockdown: https://www.jillianedelstein.com/water-rats https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jPHT2fjRoQo

7 Penguin Town: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2X-1Ui3G48

8 BBC Blue Planet: https://www.bbcearth.com/shows/blue-planet

9 This ‘conclusion’ deliberately disrupts academic conventions that insist upon not bringing in the new, inserting quotes and references; and being in conversation with the ‘introduction’. Our approach to a non-conclusion is integral to our hydrofeminist praxis in its intention unsettle. The pace of this section is also intended to conjure a rush of aqueous movement felt as swell of hope.

References

- Ahmed, S. 2021. Complaint. London: Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. 2012. “Interview with Karen Barad.” In New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies, edited by R. Dolphijn, and I. van der Tuin, 48–70. MPublishing—University of Michigan Library: Ann Arbor.

- Berlant, L. 2011. Cruel Optimism. London: Duke University Press.

- Berlant, L., and K. Stewart. 2019. The Hundreds. London: Duke University Press.

- Boscacci, L. 2018. “Wit(h)nessing.” Environmental Humanities 10 (1): 343–347.

- Boulous Walker, M. 2016. Slow Philosophy: Reading Against the Institution. London: Bloomsbury.

- Bozalek, V. 2017. “Slow Scholarship in Writing Retreats: A Diffractive Methodology for Response-able Pedagogies.” South African Journal of Higher Education 31 (2): 40–57.

- Bozalek, V. 2021. “Slow Scholarship: Propositions for the Extended Curriculum Programme.” Education as Change 25. https://doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/904.

- Burnett, E. J. 2019. Swims. London: Penned in the Margins.

- Campt, T. M. 2017. Listening to Images. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Cixous, H. 1991. Coming to Writing and Other Essays. London: Harvard University Press.

- Cosslett, R. L. 2020. ‘Wild swimming'? We used to just call it swimming. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jan/29/swimming-wild-trend-social-media-cliche accessed 18 October 2023.

- Derrida, J. 1994. The Spectre of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, Trans. P. Kamuf. London: Routledge.

- Despret, V. 2004. “The Body we Care for: Figures of Anthropo-Zoo-Genesis.” Body and Society 10: 111–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X0404293

- Despret, V. 2016. What Would Animals Say if We Asked the Right Questions? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ettinger, B. 2005. “Copoesis.” iframework x Ephemera 5 (x): 703–713.

- Ferdinand, M. 2022. Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World. Translated by A.P. Smith. Polity.

- The Financial Times. 2019. At the Pond: Swimming at the Hampstead Ladies’ Pond - ‘pure joy’. https://www.ft.com/content/64fdba08-91ae-11e9-aea1-2b1d33ac3271 accessed 14 May 2023.

- Fraser, N. 2022. Cannibal Capitalism: How Our System Is Devouring Democracy, Care, and the Planet—and What We Can Do About It. London: Verso Books.

- Ghosh, A. 2021. The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Gibbs, A. 2023. “Writing in Between.” In New Perspectives on Academic Writing: The Thing That Wouldn’t Die, edited by B. Herzogenrath, 121–136. London and New York: Bloomsbury Press.

- Haraway, D. 2008. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Haraway, D. J. 2018. “Staying with the Trouble for Multispecies Environmental Justice.” Dialogues in Human Geography 8 (1): 102–105.

- Kertudo, F. 2018. “A Watery ‘We’? The Kenwood Ladies Pond, Hampstead Heath, London: A Visual (Auto)Ethnography.” (Thesis). Royal College of Art, London. Accessed: https://www.academia.edu/37509722/A_Watery_We_The_Kenwood_Ladies_Pond_Hampstead_Heath_London_A_Visual_Auto_Ethnography.

- Moggach, D. 2019. At the Pond: Swimming at the Hampstead Ladies’ Pond. London: Daunt Books.

- Neimanis, A. 2012. “Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water.” In Undutiful Daughters: Mobilizing Future Concepts, Bodies and Subjectivities in Feminist Thought and Practice, edited by H. Gunkel, C. Nigianni, and F. Söderbäck, 94–115. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nietzsche, R. 1881/1982. Daybreak. Translated by R. J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- The Observer. 2019. The Ladies’ Pond: three writers dive in https://www.theguardian.com/global/2019/jun/16/the-ladies-pond-deborah-moggach-so-mayer-and-margaret-drabble-dive-in accessed 21 April 2023.

- Pratt, M. L. 2008. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Rose, D. B. 2022. Shimmer.: Flying fox Exuberance in Worlds of Peril. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Shefer, T., and V. Bozalek. 2022. “Wild Swimming Methodologies for Decolonial Feminist Justice-to-Come Scholarship.” Feminist Review 130 (1): 26–43. http://doi.org/10.1177/01417789211069351.

- Simpson, L. B. 2017. As we Have Always Done. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Skeet, J. 2022. “Ecologies of the Classroom in an Existential Crisis: Félix Guattari’s Ecosophical Aesthetics and Teaching Poetry.” In Poetry and Sustainability in Education, edited by S. L. Kleppe, and A. Sorby, 211–230. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Smith, R. 2019. “Hampstead Heath pond enshrines trans women's right of access”. PinkNews | Latest lesbian, gay, bi and trans news | LGBTQ+ news. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- Snaza, N. 2019. “Ethologies of Education.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 20 (3): 261–271.

- Stengers, I. 2018. Another Science Is Possible. A Manifesto for Slow Science. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Tuck, E., and K. W. Yang. 2014. “Unbecoming Claims: Pedagogies of Refusal in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 20 (6): 811–818.

- van Dooren, T. 2016. The Wake of Crows: Living and Dying in Shared Worlds. New York: Columbia University Press.

- van Dooren, T., and M. Chrulew. 2022. “Worlds of Kin: An Introduction.” In Kin: Thinking with Deborah Bird Rose, edited by T. Van Dooren, and M. Chrulew, 1–15. Durham: Duke University Press.

- van Dooren, T., and D. B. Rose. 2016. “Lively Ethography: Storying Animist Worlds.” Environmental Humanties 8 (1): 77–94.

- van Eeden-Wharton, A. 2020. “Salt-Water-Bodies: From an Atlas of Loss.” (PhD dissertation). Stellenbosch University. http://hdl.handle.net/10019.1/108209.

- Wilson, H. F. 2019. “Contact Zones: Multispecies Scholarship Through Imperial Eyes.” ENE: Nature and Space 2 (4): 712–731.

- Zournazi, M. 2002. Hope: New Philosophies for Change. Pluto Press. http://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/84.