IMPACT

This article highlights the importance of those conducting evaluations, whether policy-makers or evaluators, being explicit about the purpose and use of an evaluation. Evaluation designs will affect the nature of the findings and these, in turn, can feed back into the policy process. The inherent political nature of evaluations highlights the need for the full publication of evaluation results. The public, policy-makers and other stakeholders can then have some degree of confidence in the legitimacy of the findings.

ABSTRACT

The article considers the evaluation of commodified services and the commodification of evaluations. The former distinguishes between evaluating a decision on whether to commodify a service and evaluations of commodified services. The latter explores the implications of commodifying evaluations using Weiss’ models of research use. Six themes are identified: how well the models reflect policy-making and evaluation practice; the role assigned to politics in policy evaluations; the importance of agenda setting and power in determining who and what gets evaluated; the legitimacy of the evaluations; the degree of accountability of the evaluator; and the nature of the evaluation output.

Introduction

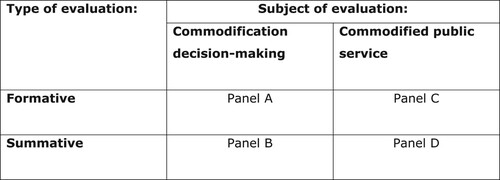

This article explores the inter-relationship between commodification and evaluation. In considering the evaluation of commodification, the article uses a two-by-two matrix distinguishing between evaluating the decision-making process on whether a service should be commodified and evaluating a service that has already been commodified, and between formative or process evaluations and summative or impact evaluations. In examining the commodification of evaluation, Carol Weiss’ (Citation1979; Citation1999) models of research use provide a framework to explore how evaluative research findings are used by policy-makers.

The aims of this article reflect the interests and research careers of the authors. We have been active in the policy evaluation market as suppliers of evaluation services while working for higher education institutions. This does not mean that we are simply advocates of the ‘marketization’ of government policy evaluations.

Following an outline of the concepts of evaluation and commodification, this article discusses the decision-making process on whether or not to commodify a service. It then discusses the commodification of evaluation—focusing on contracting out of evaluation work. The final section presents our conclusions.

Policy evaluation and commodifying evaluation

The UK Treasury (HM Treasury, Citation2020, p. 5) defines policy and programme evaluation as follows:

Evaluation is a systematic assessment of the design, implementation and outcomes of an intervention. It involves understanding how an intervention is being, or has been, implemented and what effects it has, for whom and why. It identifies what can be improved and estimates its overall impacts and cost-effectiveness.

Governments may evaluate a policy ‘in-house’ using officials, or contract out (aspects of) the evaluation to independent organizations. Where evaluation work is contracted out, especially if competitive tenders have been sought, the evaluation has been commodified. Governments have created a market, an exchange value for the evaluation of public services and goods. Even if the evaluation work is commissioned by single tender, past interventions by government have created and developed (domestic and international) markets for the evaluation of government policies and programmes.

For external providers of public policy evaluations, government contracts can be an important source of revenue. Government does not have a monopoly of national policy evaluations, there are other funders, but government does have a dominant position, especially for larger-scale, multi-method and multi-disciplinary evaluations where significant funding is required. Other sponsors (for instance the Joseph Rowntree Foundation) can provide critical and valuable policy evaluations, but evaluators funded in this way may not secure access to official administrative datasets or to officials. It is government’s access to finance, data, officials and service users that gives it a dominant position in the UK policy evaluation environment.

The scope of the analysis presented below, to render it feasible, is constrained by the operational definitions of state and commodification adopted. While recognizing that there is an extensive and rich literature on commodification, for the purposes of this article ‘in-house’ or ‘state’ refers to when civil servants or local government officials conduct an evaluation; and ‘commodification’ to when it is contracted out to an independent, third party (Spicker, Citation2023, provides a broader discussion of commodification). The analysis consequently excludes, for example evaluative studies funded independently by research councils, the Cochrane Collaboration, think tanks and others on the basis that the article’s focus is on government action to socially construct a market in public policy evaluations.

It is recognized that specific examples of policy evaluations may not easily fit this dichotomy. Policy evaluation may be partly commodified with some aspects conducted in-house and others commissioned. Governance arrangements may also make it difficult to determine if an evaluation has been commodified. For instance the Department for Transport established in January 2009 a wholly-owned company (a non-departmental public body), High Speed 2 (HS2) Ltd, to evaluate the case for high-speed rail services between London, Manchester and Leeds via Birmingham. The ex-ante appraisal, in the form of a cost-benefit analysis, was initially published in 2011 and has been periodically updated. Although these appraisals are commissioned by the Department for Transport, in what sense are they commodified? HS2 Ltd is not as independent of the department as say a university transport research centre. In practice, evaluations may be characterized by their degree of commodification.

The commodification and evaluation literatures devote little attention to the commissioning of policy evaluations (Dahler-Larson, Citation2006, p. 148). Indeed, the UK Treasury’s evaluation manual gives it just half a page and elsewhere makes only passing references to the commissioning of evaluations by officials (HM Treasury, Citation2020, p. 74). Nonetheless, it has been discussed by some scholars. Dahler-Larson (Citation2006, pp. 148–149), for instance, provides a succinct overview of the pros and cons of tendering evaluations. The effects of commodification in specific policy areas has also been considered. For instance Gray (Citation2007, p. 211) briefly argues commodification undermines cultural policy by requiring the emergence of new instrumental evaluation criteria (alongside other adverse effects accompanying the commodification of public policy) so that policy-makers can demonstrate that their policies generate a ‘public benefit’. Segerholm (Citation2003) provides a case study of the 2003 national evaluation commissioned by the National Agency of Education in Sweden, where a new focus on ‘process studies’ was seen as influencing the structure and practice of the learning process for pupils. Evaluation had become a tool of governance, with professional evaluators losing their autonomy. Commodification has also been explored in what might be considered related fields. For example personal data, where Bottis and Bouchagiar (Citation2018) discuss the commodification of big data; Sevignani (Citation2013) the commodification of privacy on the internet; and, similarly, Crain (Citation2018) the commodification of data brokers (such as Experian). What distinguishes this article is the examination of the commodification of policy evaluations against different ideal types of how evaluation findings might be used in the policy process.

Evidence-based policy-making and evaluation in the UK

Contemporary evaluation of public programmes is often seen as a component of rational evidence-based policy-making, which Pollitt (Citation1993) traced to the election of the Labour government (1964–1970) in the UK, citing the 1968 Fulton Committee Report recommendation of policy planning units in central government departments to replace the ‘amateurishness of senior civil servants’ (Pollitt, Citation1993, p. 354). The application of business philosophy and techniques introduced during the Conservative government (1970–1974) was embedded with the development of New Public Management (NPM) following the election of another Conservative government in 1979. During the 1980s, government departments emphasised the 3 ‘Es’ of economy, efficiency and effectiveness—and value-for-money (VFM). The National Audit Office (NAO) was created in 1983 with considerable statutory powers of investigation on whether government is providing VFM in achieving intended policy outcomes (Roberts & Pollitt, Citation1994), although in practice the central focus was on efficiency and economy with less attention paid to the effectiveness of policies (Pollitt, Citation1993).

The Labour party’s 1997 manifesto stated that ‘What counts is what works’ and, during its first term (1997–2001), the Labour government introduced a raft of large-scale social programmes, including the New Deals, Sure Start and the Education Maintenance Allowance, many of which were subject to independent evaluation (Wells, Citation2007). The Labour government piloted many of its social policies and evaluation became more embedded in the policy-making process (Walker, Citation2001; Wells, Citation2007). However, in its 2013 report, the NAO concluded that:

The government spends significant resources on evaluating the impact and cost–effectiveness of its spending programmes and other activities. Coverage of evaluation evidence is incomplete, and the rationale for what the government evaluates is unclear. Evaluations are often not robust enough to reliably identify the impact, and the government fails to use effectively the learning from these evaluations to improve impact and cost-effectiveness (NAO, Citation2013, p. 10).

While individual departments have undertaken initiatives to improve evaluation, the use of evaluation continues to be variable and inconsistent, and government has been slow to address the known barriers to improvement. As a result government cannot have confidence its spending in many policy areas is making a difference (NAO, Citation2021, p. 10).

The UK ‘evaluation industry’ includes academics, think tanks, accountancy/audit/management consultancy firms and market research companies. Depending upon the scale and nature of the policy evaluation, actors may sub-contract work to other market players, or form consortiums. On occasions international actors (for example Abt Associates, MDRC, Mathematica, or the Urban Institute from the USA) may lead or join UK teams conducting policy evaluations. The market also includes capacity within the civil service to undertake policy evaluations, as well as a range of governmental and parliamentary bodies (such as the NAO, various ombudsmen and parliamentary select committees).

The decision to privatize or contract out a public service is usually highly controversial. The contested nature of commodification of public services is unsurprising given that it inevitably has distributional consequences—there will be winners and losers arising from the decision. These consequences mean that any such decision is political in nature. The next part of this article explores how the decision-making process on whether or not to commodify a service is, or could be, evaluated.

Evaluation of commodification

In considering the evaluation of commodification, a frame of reference is required. Our framework has two aspects. First, it distinguishes the subject of evaluation into the decision-making process on whether or not to commodify a service, and the evaluation of the commodified service itself. Second, it distinguishes between formative or process evaluations and summative or impact evaluations. These distinctions result in the two-by-two matrix in .

Formative evaluations explore how, for whom and why a policy works. The sorts of questions addressed include: Does practice match policy design? Does a programme reach its target population? What are the resource inputs and consequences? Summative evaluations consider to what extent the goals of a policy are fulfilled, with a focus on policy outcomes, as opposed to outputs, for example on patients’ health post-policy intervention rather than the number of patients treated. Depending upon the design, the evaluation may include a cost-effectiveness or cost-benefit analysis. A key feature of summative evaluations is the counterfactual: what would happen if the policy was not introduced. Estimating the counterfactual, so that it can be compared with policy outcomes, is one of the most difficult challenges in summative evaluations.

Evaluation of decisions to commodify a service (Panels A and B): Evaluations of the decision-making process on whether or not to commodify a public service focus on events before a service is privatized or contracted out. They may also cover post-decision events where analysts are interested in how implications of the commodified service feed back to the policy-making process. The evaluations are likely to be conducted after the decision has been taken, rather than contemporaneously. They will be based on people’s recollections of events and published and unpublished documents. Assessments of decision-making on the commodification of public services can take different forms, including appraisals, government policy impact statements, reviews and inquiries. They can be conducted by a range of actors and organizations, such as Select Committees and government commissioned independent inquiries. Published findings can include recommendations for improving policy and practice.

Panel A: Process evaluations cover the perspectives of relevant politicians and officials, and potential service providers, public service staff and users. Studies of public awareness, preferences and likely service usage could also be conducted. Such evaluations can identify the social, economic and political milieu of the decision-making process, the key actors involved, the factors influencing the (internal) debates on commodification and the actual criteria used to make the decision. See, for instance, the study of commissioning health services by Sheaff et al. (Citation2023). The policy ‘logic’ of how and why commodification will result in its alleged benefits can be presented.

Decisions on privatization and contracting out can be highly controversial. Evaluating the politics of the process may reveal the extent to which ideology rather than, say, robust research evidence influenced decision-making. Analysts could identify who policy-makers identified as the potential winners and losers of any subsequent public service commodification.

The criteria for assessing the commodification decision process will be influenced by the sponsor of the evaluation. Possible criteria include the degree of transparency and public involvement, was VFM demonstrated, timeliness of the final decision, degree of political and/or public support and so on. The choice of criteria to be used is, itself, not a neutral decision as it will serve to highlight good and poor consequences for certain actors. For example the Department for Transport’s unsuccessful attempt to award the InterCity West Coast rail franchise in 2012 led to two official independent reports: the Laidlaw Inquiry (Laidlaw, Citation2012) and the Brown Review (Department for Transport, Citation2013). Both included extensive criticisms of the department’s decision-making structures and processes; in part, they are process evaluations of the then rail franchising arrangements. The Laidlaw Inquiry focused narrowly on aspects of the failed procurement process; it is complemented by the Brown Review that identified wider institutional shortcomings in rail franchise governance. The reports are supportive of the franchise model but include numerous recommendations for improvement.

Panel B: Summative evaluations of commodification decisions may take a variety of forms, including cost analyses, cost-effectiveness studies and comprehensive cost-benefit analyses (Boardman & Vining, Citation2017, Table 5.1). These summative evaluations may be published and used by policy-makers to justify the commodification of a service. One approach is to investigate the impacts of trends on the likely realization of a desired policy objective or outcome. Adverse impacts, in the form of barriers or obstacles to achieving the objective or outcome, can lead to policy recommendations. For instance the Hooper Reviews (Hooper et al., Citation2008; Hooper, Citation2010) explored the challenges to maintaining a universal postal service. The reviews found that the Royal Mail’s share of the postal market was declining, the pace of modernizations was too slow, the regulatory framework was ‘not fit for purpose’ and its pension deficit was growing. A key recommendation was the need to introduce private capital to the postal service. This helped justify the Coalition government’s privatization of Royal Mail commencing in October 2013. However, a VFM report by the NAO the following year considered that the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills had taken an overly cautious approach to the flotation including pricing the shares substantially below the level at which they started trading—causing considerable losses to the taxpayer (NAO, Citation2014).

The Hooper Reviews did not include a version of cost-benefit analysis, but examples can be found across a range of policy areas, for example transport (such as the initial and numerous updates to the economic case for building High Speed 2) and health (where cost-utility analysis can be used to compare the costs and effects of alternative interventions and help determine whether the NHS or individuals have to pay for treatments).

While these analyses may be presented by policy-makers as objective, and technical assessments, they are not. They involve making (sometimes heroic) assumptions about future events and behaviours; and while they can incorporate the best available data, this may be out-of-date and/or of poor quality. Whose benefits and costs are to be included in any summative evaluation is a value judgement that has political consequences. Savings to the taxpayer/Treasury are often highlighted, while critics of a decision may argue that spillover effects and intangible benefits have been omitted or given insufficient weight and prominence in an analysis. The method of evaluation used will influence the decision taken. For example the rationale of cost-benefit analyses is typically to maximize economic efficiency. Although they can incorporate a distributional analysis, they tend not to seek to maximize social justice—which could give a different result to a conventional cost-benefit analysis.

Evaluations of commodified services (Panels C and D): There are many examples of evaluations of commodified public services. Sponsors of Panel C and D evaluations will have agendas: evaluation questions that evaluation designs seek to answer. In practice, both formative (Panel C) and summative (Panel D) evaluations tend to address the question of ‘what works?’

An example of a formative evaluation (Panel C) is Duffy et al. (Citation2010), commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions, to provide early feedback following the national roll-out of the Accessing Jobcentre Plus Customer Services model, which had expanded the use of telephony and web-based services to reduce rising levels of footfall in local benefit offices. The evaluation included observational studies and in-depth face-to-face staff interviews in the selected Jobcentre Plus local offices; telephone interviews with staff in the associated Benefit Delivery Centres; and a focus group with the National Jobcentre Plus Customer Representative Group Forum. The report made several recommendations, specifically to the approach of staff, and associated staff guidance to the identification of vulnerable customers.

Summative evaluations (Panel D) include numerous studies of welfare-to-work programmes. For example Melville et al. (Citation2018) carried out an early-stage impact assessment of the Working Well pilot programme: a two-year pilot operating in Greater Manchester with the aim of helping long-term claimants with health conditions into work. The evaluation investigated whether the programme is more effective at helping people move off benefits and into work compared to the existing Jobcentre Plus support. The evaluation found no statistically significant impact from the pilot programme on the amount of time spent off out-of-work benefits. However, the authors noted that their ‘mixed results’ were not unexpected given the distance of participants from the labour market and the early point of assessment of a programme designed to address deep-rooted barriers to employment.

That a service has been commodified appears to be accepted as a given; evaluation questions focus on effectiveness and efficiency. This focus implies that a rigorous comparison of public verses private provision tends not to be made. In some cases, the scale of commodification means there is no public provision to make such a comparison. Even when public provision operates alongside private sector provisions (as in, say, a pilot scheme), comparisons may not be made, especially if the evaluations are government funded as the studies could re-open debates about the merits of the original commodification decision. In these circumstances whether the adage ‘private sector good, public sector bad!’ is backed by robust evidence may not be addressed.

Evaluations are driven by the questions to be addressed. Different evaluation sponsors might pose different questions. The issue is then who can afford to pay for evaluations. Summative evaluations in particular can be very expensive to conduct. Who conducts these evaluations will reflect access to funding and, in practice, it can be expected that evaluation questions that get asked and addressed are those that reflect the interests and preferences of those with access to resources and power. What is evaluated and how will reflect existing social and economic inequalities. Outside of UK central and local government, (the institutions responsible for commodifying a service), few bodies have the resources or ability to gain access to necessary data on providers and users to enable comprehensive evaluations to be undertaken. The most disadvantaged, without the aid of an interested third party (such as a charity), will be unable to get their questions about a commodified service answered. Chau and Yu (Citation2023) highlight how the gendered consequences of commodified services may be neglected.

Even a ‘white knight’ funder will have their own agenda and the extent to which vulnerable groups are allowed to be involved in the evaluation design is likely to be conditional. Nonetheless, partial evaluations, especially formative studies, have been successfully conducted by non-governmental bodies. See, for example the use of six NHS trust case studies by Exworthy et al. (Citation2023) to explore the impact of pursuing commercial income on the Trusts’ entrepreneurial activities. The ‘winners’ are those governmental and non-governmental bodies and the wider public to the extent that studies inform wider public debates.

Commodification of evaluation

Shadish et al. (Citation1991; as cited in Stevenson & Thomas, Citation2006, p. 201) identified five major categories of evaluation theory: social programming, knowledge, value, use and evaluation practice. We follow the ‘use’ approach in this article, because commodification involves creating a market and an exchange value for something and the notion of it having a ‘use’ is key. The utilization (or use) of evaluation is a multi-dimensional and complex phenomenon (Shulha & Cousins, Citation1997, p. 196). That evaluators seek to produce evaluations that are usable by, and of value to, their clients is to be expected. Although the extent to which evaluations subsequently influence policy and practice is possibly less than, at least, some evaluators would hope (Stahler, Citation1995, pp. 130–131).

There are several theories and models of evaluation utilization, for example Catan (Citation2002), Shulha and Cousins (Citation1997), Vedung (Citation2012), Walter et al. (Citation2004). To take into account variation in how (commodified) evaluation evidence is used in policy-making, Weiss’ seven models of research utilization in public policy are deployed and adapted to focus on evaluative research rather than research more generally (Weiss, Citation1979). While Weiss (Citation1998) does consider the use of evaluation by policy-makers, she does not make the distinction between commodified and non-commodified evaluations. Nonetheless, Weiss’ models are pertinent because she acknowledges the importance of the political context to the use of evaluative research in the decision-making process and that evaluation findings compete against other issues advanced by a plurality of interest groups and stakeholders for salience when policy issues are considered (Shulha & Cousins, Citation1997, p. 197). Weiss’ models can also be used analytically, to explore how evidence is deployed in policy-making (see, for instance, Young et al. (Citation2002) modified Weiss framework), in contrast to some other more normative approaches that seek to encourage a preferred type and form of interaction between evaluator and sponsor. Her models allow the implications of whether or not evaluations are commodified to be explored.

Weiss’ seven models are:

Knowledge-driven model—a linear model where knowledge leads policy development and taking the form: Basic research → Applied research → Development → Application. A possible example is the French and UK governments’ support for the development of a commercial supersonic aircraft, the Concord(e), following scientific advances at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough (Young et al., Citation2002, p. 216). While this model does comply with a naïve model of evidence-based policy-making, scientific research findings tend not to be as robust or uncontested as the model requires.

Problem-solving model—a linear model where social problems instigate policy and taking the form: Problem → Decision to tackle → Identify information missing → Research conducted → Gap plugged → Policy solution. Evaluative research provides the evidence used to assess the extent to which a policy problem has been, or will be, solved. However, it depicts evaluative research as an empirical means to a set policy goal and, as such, is a form of naïve empiricism, ignoring the role of theory or a theory of change in policy design. A policy will also tend to address multiple problems and its evaluation is likely to reveal varying degrees of success in tackling the relevant problems. Giving rise to the issue of which, and whose, is the underlying problem to be solved and evaluated (Vedung, Citation2012, p. 392).

Interactive model—A non-linear model entailing potential complex interactions and consultations with a range of actors (or stakeholders) who form policy communities. ‘The archetype is the academic or think tank policy analysts whose grasp and understanding of a policy problem enable them to propose new solutions’ (Young et al., Citation2002, p. 217); for example the role of the Centre for Social Justice in the introduction of Universal Credit in the UK. The competing vested interests of different groups of actors implies that evaluative research designs, objectives and outputs will be contested. In particular findings are used selectively to support group positions and arguments in policy development. Alternatively, if using a pluralistic evaluation design that reveals stakeholders’ varying views and experiences this model might build a political consensus across groups. This model encourages an incremental approach to policy-making with marginal moves taken towards the iterative evaluation and refinement of policies.

Political model—Policy is pre-determined and there is no role for new evidence. There is only a limited role for rigorous and robust evaluative research and studies are conducted to achieve political goals (Stahler, Citation1995, p. 131). Indeed, the establishment of robust evaluations may even be ‘resisted’ by policy-makers and practitioners. Politicians use evaluation studies to justify and legitimize their policies.

Tactical model—For policy-making purposes, evaluative research findings are not relevant. Evaluations are essentially symbolic and conducted to show that something is being done, for example to deflect criticism or delay taking a decision (Stahler, Citation1995, p. 131).

Enlightenment model—Evaluative research helps shape ways in which policy-makers and public think about social issues. The main contribution of evaluative research to policy-making is the impact on the underpinning theoretical and conceptual base of studies. Alongside the ‘tangible’ findings of evaluations, there is an ‘intangible’ better understanding of theoretical and conceptual issues that over time ‘percolate’ through the policy-making community to improve the quality of decision making. Evaluative research can alter how policy-makers and public perceive policy problems and their solution.

Research as part of the intellectual enterprise of society—Sees policy evaluation as embedded in wider society, as much of a social construct as policy itself and the social sciences (see Dahler-Larson, Citation2006). ‘Like policy, social science research responds to the currents of thought, the fads and fancies, of the period. Social science and policy interact, influencing each other and being influenced by the larger fashions of social thought (Weiss, Citation1979, p. 430). Social science research may contribute to the ‘reconceptualization’ of social issues by policy-makers and so influence policy agendas and subsequently the allocation of funding for evaluative research of policy.

The analysis seeks to identify the consequences for in-house and commodified policy evaluations of the seven utilization models. The implications of the models for the commodification of policy evaluations overlap, thus, to avoid repetition if each model was discussed in turn, a number of themes that cross more than one model are identified. These themes are:

How well the models reflect policy-making and evaluation practice, or how ‘grounded’ are the models.

The role assigned to politics in policy evaluations.

Agenda setting and power.

The perceived legitimacy of the evaluations.

The degree of accountability of the evaluator.

The nature of the evaluation output.

Grounded

Two of the models are highly idealized and abstract representations of how policy is made: the knowledge-driven and problem-solving models. They depict a rational, apolitical, technocratic view of policy-making where evaluations provide objective evidence on the success or otherwise of policies—an ‘instrumental use’ of evaluations (Weiss, Citation1998). Both models chime with NPM, with evaluators sine qua non as experts providing the necessary evidence to help judge the value of policies. Such models are not grounded in how policies are made in practice, nor how policy evaluations are used in practice.

In the knowledge-driven model, policy evaluative research conducted in-house by the state builds upon scientific research produced by officials, but in the commodified variant these tasks are conducted outwith government. The in-house version of this model is unrealistic because the state does not have the capacity nor the expertise to undertake the science or the evaluative research required. In the problem-solving model, in-house evaluations require officials to accept politicians’ policy gaols, but policies typically share multiple goals and there may be internal policy and political tensions over given goals and their relative priority and this conflict undermines the model, as it makes judging the performance of a policy problematic. When policy evaluation is commodified in the problem-solving model, the independent evaluator is required to accept set policy goals. From a societal point of view, this may mean that some policies are not subject to rigorous and independent evaluative research, because governments (for whatever reason) choose not to commission relevant policy evaluations; and non-governmental sources of funding may not be available for evaluators to enable studies of policies and their goals. Of course, policy-makers can also choose that in-house staff should not evaluate certain policies.

To the extent that the knowledge-driven and problem-solving models require judgements on a policy to be made against set policy goals, then both—whether or not commodified—risk evaluations missing the impacts of unintended policy consequences. Evaluations risk excluding evidence on unanticipated effects and neither model in its commodified or in-house forms guards against this possibility.

However, these two models may have some heuristic value in highlighting the risks, and pros and cons, of commodifying evaluations. Although idealized, these two models provide prima facie support that whether policy evaluations are commodified or not is important, notably that there are capacity constraints on what officials can do in practice.

The other models are more ‘grounded’ in everyday practice, but retain a degree of abstraction. In particular, the in-house version of the enlightenment model includes a degree of benign abstractedness that possibly renders it impractical. This is because the enlightenment model does not actually require the underlying values or goals of the study to match those of the policy-makers. If they do not, it is difficult to see why policy-makers would sponsor the conduct of an evaluation at odds with their set goals. In addition, the need for timely evaluation findings in policy-making may mean there is not the resource (including time) to undertake such studies.

Politics

To the extent that evaluation evidence is used selectively by policy-makers (a ‘symbolic use’ of evaluation (Weiss, Citation1998)), then ideological and political positions are used to interpret, and make use of, evaluation findings (Nutley et al., Citation2007, p. 15; Shulha & Cousins, Citation1997, p. 203). In practice (and contrary to the problem-solving and knowledge-driven models), evaluations are not used according to a conventional rational model of policy-making. Such a model:

… assumes that if Government commissions [evaluative] research to its own specification, the business of extracting messages will be unproblematic, and the research will by definition be both useful and used. However, it is clear that Government’s use of research is a more mixed and patchy story, ranging from earnest and honest use of research findings in decision making and policy development, through to selective quotation to back decisions reached by other means, and, upon occasion, distortion and even suppression of research findings which run counter to decisions taken for entirely other reasons. The assumptions about what it is to commission research at the Centre are echoed at the periphery, in Local Authorities, Health Authorities and the larger voluntary organizations (Catan, Citation2002, p. 2).

In the interactive model, bi-partisanship can mean that commodified evaluations are not seen by non-governmental actors in the policy process as independent and legitimate sources of evidence (see below), because governments set the evaluations’ objectives and overall design. In a pluralist democracy there is a risk that contracted out evaluations are seen by at least some stakeholders as ‘tainted’ as in-house evaluations. This risk arises because: ‘Evaluation is inescapably a political activity in that it is closely tied to the idea of change and to the exercising of power and control’ (Segerholm, Citation2003, p. 1).

However, other stakeholders may adopt a different perspective and accept the independence and rigour of commodified policy evaluations.

In the tactical model, evaluations may also be commissioned for symbolic purposes—they are conducted so governments are seen as doing something. However, such evaluations may be under-resourced (Stahler, Citation1995, p. 132) and/or findings not used to inform policy and this will limit their usefulness to policy-makers and practitioners as potential lessons cannot be learnt.

Legitimacy

Evaluators secure legitimacy and high levels of trust by being perceived as professional. This in turn requires that they are seen to have a degree of autonomy or independence in conducting evaluations. This source of legitimacy applies to officials and contactors conducting evaluations (Weiss, Citation1998). Some of the models—problem-solving, interactive and political—challenge the idea that the evaluators are ‘independent’ of policy-makers.

Legitimacy can be undermined for state-conducted policy evaluations where officials have to accept stated policy goals (problem-solving model) or due to organizational structures where policy-makers and evaluators work in the same department (interactive model) and as a result evaluators may encounter difficulties in ‘speaking truth to power’.

Commodified evaluations may lead to ‘sponsor capture’ whereby firms highly reliant on government evaluation contracts ‘make subtle trade-offs in objectivity’ for ongoing business reasons (Davies et al., Citation2006, p. 174). In practice, this risk is likely to be low, because of the high reputational, and subsequent financial, losses that would follow from not being seen as an independent and legitimate evaluator. However, commodified evaluations risk not being seen as legitimate when government determines which policies are or are not to be evaluated (political model). As agenda setting is a significant part of policy-making, this issue is discussed further below.

Alternatively, in the interactive model where contractors are seen by stakeholders as independent, the resulting perceived legitimacy of the evaluation may help consensus building on policy.

Agenda setting and power

As already mentioned, UK governments have a dominant position in the policy evaluation market. As Dahler-Larson (Citation2006, p. 148) states: ‘There is no guarantee, however, that important areas of life in society which need evaluation are actually evaluated’. Having a dominant position means that government has a significant say in which policies are evaluated internally by officials, externally by independent evaluators, or not at all. This gives them the power to set policy evaluation agendas and their decisions on evaluations will reflect political party priorities (Davies et al., Citation2006, p. 173). It is the dominant role of government funding in the UK evaluation industry that risks minimising the comprehensive and systematic assessment of a wider range of public policies.

Moreover, once practitioners know what is being evaluated and the metrics being used, this may affect their behaviour:

The choice of measures (or in qualitative evaluations, the focus of study) can influence program operations. That is a way that evaluation is used. And not only the measures but also the design of evaluation itself … (Weiss, Citation1998, p. 26)

With the possible exception of the commodified variant of the enlightenment and ‘intellectual enterprise’ models, the concern that government can set policy evaluation agendas is a feature of all of the models, whether or not evaluation is commodified. Both these models challenge the rationale for commodifying evaluations. With these models, evaluations can empower communities and users of public services and explore the wider social context to social issues. The evaluations can challenge power relationships and hence ‘the dominant policy discourses’ and are ‘divorced’ from the concerns of commissioners of policy and practice evaluations (see, for instance, Spence and Wood (Citation2011) discussion on youth work). Providing possible (political) reasons as to why some policy-makers may not wish to commodify an evaluation under these two models.

Accountability

Officials conducting policy evaluations are accountable via line managers, ultimately to politicians. This is an idealized notion of accountability, as officials can, for instance, use a variety of tactics to resist policies. But to whom are contracted evaluators accountable? Evaluation tenders will specify contractors’ responsibilities with regards to budgets, outputs and timescales, which help to address moral hazard risks, but there is no direct, only indirect, democratic accountability for work undertaken.

This relative lack of accountability for commodification appears to cut across all the models. However, if policy evaluations are transparent, especially if reports of commodified policy evaluations are published, then there is an opportunity for them to be utilized by stakeholders with an interest in a given policy. This applies notably to the interactive, political, tactical and enlightenment models.

Nature of the output

Except for the enlightenment and ‘intellectual enterprise’ models, evaluation outputs are considered to be fairly self-contained and the scope for wider learning (by policy-makers and evaluators) is limited. The enlightenment model allows for the possibility of some form of ‘lesson learning’ because an evaluation (whether or not commodified) can have ‘intangible’ outcomes (a ‘conceptual use’ of evaluations: see Weiss, Citation1998). A policy-maker and/or evaluator could, for example, gain an appreciation of a new approach or theory, or experience of a new evaluation method or tool, that they could subsequently adopt for a different policy or even policy domain. It was suggested above that operationalizing the enlightenment model in its state form was problematic. While the sociological foundations of the ‘intellectual enterprise’ model suggests that notwithstanding the scope for wider learning, any opportunity will be shaped and influenced by wider societal trends and factors.

Conclusions

With the evaluation of commodification, the decision to commodify a public service will be political and can be controversial. The setting of the evaluation agenda—what and who is included in the study—is determined by the policy-maker. It follows that the aims, objectives and questions asked are political in nature. This applies to evaluations of the decision-making process and of the commodified service. Evaluation designs will influence the scope, type and nature of the evidence gathered, which in turn (depending upon how the evaluation results are used in the policy process) can influence the substance of policy decisions.

When policies are to be evaluated, policy-makers can choose to have evaluations conducted in-house or contracted out. Using Weiss’ seven models of research use, six themes emerge from whether or not evaluations are commodified. These themes are: how well the models reflect policy-making and evaluation practice; the role assigned to politics in policy evaluations; the importance of agenda setting and power in determining who and what gets evaluated; the legitimacy of the evaluations; the degree of accountability of the evaluator; and the nature of the evaluation output.

The models can demonstrate some benefits to commodifying evaluations of policy interventions. They address capacity limitations within government to conduct large-scale evaluations. For policy-makers, commodified evaluations, via the independence of the contractor, may also have the merit of providing a degree of legitimacy in public, political and policy discourse. While acknowledging that the power balance between sponsors and evaluators can be unequal and the relationship between officials managing evaluation contracts and contractors can be close, complex and at times difficult.

Knowing that a policy is to be evaluated (in-house or externally) may also lead policy-makers to be more careful and rigorous in setting and designing a policy (Weiss, Citation1998, pp. 25–26). Nonetheless, as Weiss (Citation1999, p. 468) observes:

Evaluation has much to offer policy makers, but policy makers rarely base new policies directly on evaluation results. Partly this is because of the competing pressures of interests, ideologies, other information and institutional constraints. Partly it is because many policies take shape over time through the actions of many officials in many offices, each of which does its job without conscious reflection. Despite the seeming neglect of evaluation, scholars in many countries have found that evaluation has real consequences: it challenges old ideas, provides new perspectives and helps to re-order the policy agenda.

If the above are the ‘winners’, the ‘losers’ are harder to identify and do not vary by whether or not the evaluation is commodified. They may have lost anyhow if an evaluation is not conducted, or possibly the evaluation design or questions posed do not enable them to be ‘counted’ or ‘heard’. In either case, the public is a loser because any subsequent policy discourse is less informed than it could have been.

Where an evaluation of a commodified public service has been commissioned, the evaluators share a similar position to the service providers—both have a legal and financial contractual relationship with the government. We have experience of conducting contracted out evaluations of contracted out services. This did not create any conflicts of interest for us and we do not know of any actual cases where this relationship has influenced evaluators’ findings. However, it does imply a potential conflict of interest, with evaluators sharing a similar position to service providers with respect to the benefits of commodification. Given relatively low levels of trust in the UK government (ONS, Citation2022) and concerns about accountability mentioned above, the independence and legitimacy of commodified evaluations needs to be ensured. The UK Evaluation Society (Citation2018) has a robust set of good practice guidelines and perhaps contractual and institutional ways need to be found to embed their adoption in commodified evaluations.

The article suggests that evaluators within and outwith government need to establish, before a study commences, why an evaluation is being undertaken and policy-makers’ intentions on how the findings are to be used in the policy process. Evaluation findings need to be published in full so that all interested parties have access to the study. The article reinforces Rutter (Citation2012, p. 27) on the importance of having external ‘evidence institutions’ that are independent and creditable with reputations for producing robust findings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bruce Stafford

Bruce Stafford is Emeritus Professor of public policy at the School of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Nottingham, UK. He has extensive experience of leading and conducting commissioned evaluation and research studies for government, notably on social security, disability and employment policies.

Simon Roberts

Simon Roberts is Associate Professor of Public and Social Policy at the School of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Nottingham, UK. He has wide experience of leading UK and international research including several national evaluations for UK government on social security, disability and discrimination.

Pauline Jas

Pauline Jas is Associate Professor of Public Policy at the School of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Nottingham, UK. Pauline lectures on public administration, including procurement policies and practices, and researched the performance of local government in the UK.

References

- Boardman, A., & Vining, A. (2017). There are many (well, more than one) paths to Nirvana: The economic evaluation of social policies. In B. Greve (Ed.), Handbook of social policy evaluation (pp. 77–99). Edward Elgar.

- Bottis, M., & Bouchagiar, G. (2018). Personal data v. big data: challenges of commodification of personal data. Open Journal of Philosophy, 8(3), 206–215.

- Catan, L. (2002). Making research useful: experiments from the Economic and Social Research Council’s youth research programme. Youth & Policy, 76, 1–14.

- Chau, R. C. M., & Yu, S. W. K. (2023). Using a time conditions framework to explore the impact of government policies on the commodification of public goods and women’s defamilization risks. Public Money & Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2246756

- Crain, M. (2018). The limits of transparency: Data brokers and commodification. New Media & Society, 20(1), 88–104.

- Dahler-Larson, P. (2006). Evaluation after disenchantment? Five issues shaping the role of evaluation in society. In I. Shaw, J. Greene, & M. Mark (Eds.), The Sage handbook of evaluation (pp. 141–160). Sage.

- Davies, P., Newcomer, K., & Soydan, H. (2006). Government as structural context for evaluation. In I. Shaw, J. Greene, & M. Mark (Eds.), The Sage handbook of evaluation (pp. 164–183). Sage.

- Department for Transport. (2013). The Brown review of the rail franchising programme. Cm 8526. TSO.

- Duffy, D., Roberts, S., & Stafford, B. (2010). Accessing customer services in Jobcentre Plus: a qualitative study. DWP Research Report No. 651. CDS.

- Exworthy, M., Lunt, N., Tuck, P., & Mistry, R. (2023). From commodification to entrepreneurialism: how commercial income is transforming the English NHS. Public Money & Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2243775

- Gray, C. (2007). Commodification and instrumentality in cultural policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 13(2), 203–215.

- Henkel, M. (1991). The new evaluative state. Public Administration, 69(1), 121–136.

- HM Treasury. (2020). Magenta Book: Central government guidance on evaluation. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/879438/HMT_Magenta_Book.pdf.

- Hooper, R. (2010). Saving the Royal Mail’s universal postal service in the digital age: An update of the 2008 independent review of the postal services sector. Cm 7937. TSO.

- Hooper, R., Hutton, D., & Smith, I. (2008). Modernise or decline: Policies to maintain the universal postal service in the United Kingdom. An independent review of the UK postal services sector. Cm 7529. TSO.

- Laidlaw Inquiry. (2012). Report of the Laidlaw Inquiry: Inquiry into the lessons learned for the Department for Transport from the InterCity West Coast Competition. HC 809. TSO.

- Melville, D., Bivand, P., Quecedo, C., Vaid, L., & McCallum, A. (2018). Greater Manchester Working Well: Early impact assessment. Research Report No. 946. DWP.

- NAO. (2013). Evaluation in government. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/10331-001-Evaluation-in-government_NEW.pdf.

- NAO. (2014). The privatization of Royal Mail. HC 1182. Session 2013-14. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/The-privatisation-of-royal-mail.pdf.

- NAO. (2021). Evaluating government spending. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General. Session 2021-22. HC 860. https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/evaluating-government-spending/.

- Neave, G. (1988). On the cultivation of quality, efficiency and enterprise: an overview of recent trends in higher education in Western Europe, 1986-1988. European Journal of Education, 23(1-2), 7–23.

- Nutley, S., Walter, I., & Davies, H. (2007). Using evidence: How research can inform public services. Policy Press.

- ONS. (2022). Trust in government, UK: 2022. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/trustingovernmentuk/2022#:~:text=42%25%20of%20the%20population%20reported,and%20legal%20system%20(68%25).

- Pawson, R. (2005). Evidence-based policy: A realistic perspective. Sage.

- Pollitt, C. (1993). Occasional excursions: a brief history of policy evaluation in the UK. Parliamentary Affairs, 46(3).

- Roberts, S., & Pollitt, C. (1994). Audit or evaluation? A National Audit Office VFM study. Public Administration, 72, 527–549.

- Rutter, J. (2012). Evidence and evaluation in policy making: A problem of supply or demand? Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/evidence-and-evaluation-policy-making.

- Shadish, W., Cook, T. & Leviton, C. (1991). Foundations of program evaluation: Theories of practice. Sage.

- Segerholm, C. (2003). To govern in silence? An essay on the political in national evaluations of the public schools in Sweden. Studies in Educational Policy and Educational Philosophy, 2003(2). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108016522729.2003.11803867.

- Sevignani, S. (2013). The commodification of privacy on the internet. Science and Public Policy, 40(6), 733–739.

- Sheaff, R., Ellis-Paine, A., Exworthy, M., Hardwick, R., & Smith, C. (2023). Commodification and healthcare in the third sector in England: from gift to commodity—and back? Public Money & Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2244350

- Shulha, L., & Cousins, J. (1997). Evaluation Use: theory, research, and practice since 1986. Evaluation Practice, 18(3), 195–208.

- Spence, J., & Wood, J. (2011). Youth work and research: Editorial. Youth & Policy, 10, 1–17.

- Spicker, P. (2023). The effect of treating public services as commodities. Public Money & Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2240641

- Stahler, G. (1995). Improving the quality of evaluations of federal human services national demonstration programs. Evaluation and Program Planning, 18(2), 129–141.

- Stevenson, J., & Thomas, D. (2006). Intellectual Contexts. In I. Shaw, J. Greene, & M. Mark (Eds.), The Sage handbook of evaluation (pp. 200–224). Sage.

- UK Evaluation Society. (2018). Guidelines for good practice in evaluation. https://www.evaluation.org.uk/app/uploads/2019/04/UK-Evaluation-Society-Guidelines-for-Good-Practice-in-Evaluation.pdf.

- Vedung, E. (2012). Six models of evaluation. In E. Araral, S. Fritzen, M. Howlett, M. Ramesh, & X. Wu (Eds.), Routledge handbook of public policy (pp. 385–400). Routledge.

- Walker, R. (2001). Great expectations: can social science evaluate New Labour's policies? Evaluation, 7(3).

- Walter, I., Nutley, S., Percy-Smith, J., McNeish, D., & Frost, S. (2004). Improving the use of research in social care practice. Social Care Institute for Excellence.

- Weiss, C. (1979). The many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review, 39(5), 426–431.

- Weiss, C. (1998). Have we learned anything new about the use of evaluation? American Journal of Evaluation, 19(1), 21–33.

- Weiss, C. (1999). The interface between evaluation and public policy. Evaluation, 5(4), 468–486.

- Wells, P. (2007). New Labour and evidence based policy making: 1997-2007. People, Place & Policy Online: 1/1, pp. 22-29. https://extra.shu.ac.uk/ppp-online/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/new_labour_evidence_base_1997-2007.pdf.

- Young, K., Ashby, D., Boaz, A., & Grayson, L. (2002). Social science and the evidence-based policy movement. Social Policy & Society, 1(3), 215–224.