Abstract

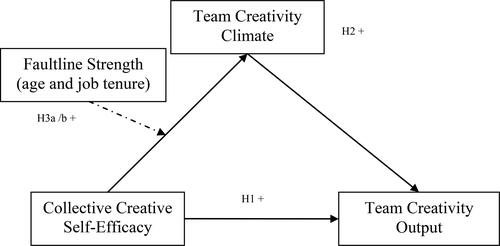

In this article, we examine how collective creative self-efficacy (CCSE) of a team can act as a competency indicator for team creativity output (TCO) in knowledge-intensive SMEs. As a team’s creative efficacy shape the collective mental model about its social context, team climate of creativity is considered as a mediator in the relationship between CCSE and TCO. Through faultline-strength analysis, we investigate how team members’ compositional attributes (age and job tenure) moderate the relationship between CCSE and team climate. A High sub-group separation (age and job tenure attributes) of team members is beneficial in a high CCSE team, whereas a homogeneity in age and tenure is desirable when a team’s CCSE is low. Our results show group faultline-strength can significantly strengthen or dampen the existing team climate and team creativity output within SMEs, thus creating a strong basis for firm owners or managers to align teams for improved team output. Moreover, HRs in such firms can design interventions to measure and enhance teams’collective creative self-efficacy of a team that serve two purposes—a) act as a competency indicator that guides a team to become self-directed, and, b) strengthen the team creativity climate for producing creative deliverables.

1. Introduction

Though Talent Management (TM) research has grown exponentially in the last decade (McDonnell et al., Citation2017), few talent-related issues remain a concern to TM practitioners. Apart from the “right skill” availability issue, sourcing and talent retention pose a threat to the growth of organizations (Vaiman et al., Citation2017). Research indicates that such challenges are persistent because of the high context-sensitive nature of TM. To date, researchers have ignored the impact of contextual factors on TM practices and the role of different actors in the process (Gallardo-Gallardo et al., Citation2020). TM issues vary significantly depending on the nature of organizations. It becomes salient in the resource-constrained environment of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In an emerging market context, factors such as rapid internationalization (Zhu et al.,Citation2006), quick prototyping and development of innovative products and processes (Wong et al., Citation2005), knowledge spill-over effects by multi-national enterprises (MNEs) (Acs & Varga, Citation2005) have contributed to high productivity gains in few SMEs. The presence of a “casual” culture drives most SMEs to adopt an inclusive approach towards TM and teamwork (Festing et al., Citation2013; Valverde et al., Citation2013). However, SMEs across the globe have recognized factors such as talent attraction, motivation and development as few TM challenges (Deshpande & Golhar, Citation1994). The problem is acute in knowledge-intensive SMEs that are often characterized by a high number of problem-solving incidents, high dependency on individuals and their networks and loyalty (Nunes et al., Citation2006). In this paper we have considered a workgroup’s creativity output as one of the proxies of group talent in SMEs because of the following reasons.

India ranks low in the global innovation index (81 out of 141 countries), which in a way reflects low innovation capabilities and potential of Indian firms and SMEs in particular (Dutta et al., Citation2018). Further, issues related to low innovation capabilities are also relevant to other emerging nations. According to Morgan Stanley Capital International Emerging Market Index, twenty-six developing countries are considered emerging nations (MSCI, Citation2020). Out of these 26 emerging nations, 9 emerging economies (Argentina, Colombia, Peru, Egypt, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Pakistan) score low (bottom half out of 131 nations) in the 2020 global innovation index. (WIPO, Citation2020). China (Rank 14), Korea (Rank 10) and Czech Republic (Rank 24) are the only emerging nations that are in the top 25%.

There is a dearth of human resource planning in SMEs that indicates a lack of managerial competence in identifying and retaining talent in these firms (CII , Citation2019). This is true for other emerging nations that are performing well in the innovation index. For instance, Bai et al. (Citation2017) has observed a lack of HR planning in Chinese SMEs due to their reluctance in providing employee training.

Indian government plans to redefine the SME sector based on their turnover. Knowledge-intensive SMEs would be provided additional incentives to invest in technological investments and wealth creation through creativity and innovation (Banerjee, Citation2020).

In emerging markets, as knowledge-intensive SMEs face a constant competitive threat from foreign MNEs and SMEs, capability building on creativity and innovation is the best alternative strategy for gaining competitive advantage (Zhu et al., Citation2006). According to Lanvin and Monteiro (Citation2020) BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) have ranked low in global talent index. Moreover, Indians are collectivistic on the surface but are competitive from deep-within with a low team-friendly attitude (Inamdar, Citation2016). Such employee attitudes can act as a deterrent towards team creativity. As SMEs’ success factor is teamwork, identifying a relevant group-level competency indicator for team-level creative output may navigate such duality of mindsets. An inclusive approach towards TM can help in the development of a few group-level interventions (Fernandez-Araoz et al., Citation2017) for the identification and allocation of team-level resources.

For years academicians and practitioners have neglected the potential and development of “key groups” or cohorts of employees (Becker & Huselid, Citation2006). In MNEs, talent groups are generally identified based on job-levels or positions; however, the scenario has changed in SME settings. Due to a preferred egalitarian culture and a need to maintain a high employee morale, MNEs’ formal and exclusive approach towards TM would not fit in SMEs (Krishnan & Scullion, Citation2017). As compared to MNEs, the systematic identification of key positions, development of competency maps and talent pool creation are few difficult propositions for SMEs (Krishnan & Scullion, Citation2017). Therefore, a much holistic approach of identifying “key groups” or rather “talent groups” is a desirable strategy for SMEs to manage talent.

According to a recent talent management review article (Gallardo-Gallardo et al., 2020), talent management literature has highly ignored the micro-level (individual) and meso-level (group-level) constructs while measuring the dependent constructs (Sparrow, Citation2019). Most of TM research has focused on a narrow, generic and a profit-driven macro (organizational) perspective (Collings et al., Citation2011) where a context-relevant micro-level analysis is absent. A strong emphasis on macro-level (organizational-level/sector-level) TM perspective may have contributed to the lack of theory development in this field (Collings & Mellahi, Citation2009). To advance the knowledge in the area of talent management, researchers may seek support from psychology literature (Dries, Citation2013). Moreover, recent conceptualization of talent as “strengths” stemmed from positive psychology literature where an individual’s character strengths are treated as “potentials for excellence” (Biswas-Diener et al., Citation2011).

Research suggests that “self-efficacy” of individuals may serve as a critical indicator of “talent” and “potential” (Rhodes, Citation2012). In a similar vein, creative self-efficacy (CSE) of an employee is his/her beliefs or perceptions about producing creative outcomes (Waterwall et al., Citation2017). To understand the exact nature of the relationship between CSE and creativity, researchers must recognize the interplay between CSE and team context (Richter et al., Citation2012). However, one cannot assert that individual-level self-efficacy and collective self-efficacy are homologous (Chen & Bliese, Citation2002) as there may be a spill-over of the individual-level findings to the team-level (Rousseau & House, Citation1994). Therefore, determining cognitive group-level competency predictors for team-level creative output(s) should reflect the shared beliefs or perceptions of individual group members. With due consideration of the firm-level dynamics of SMEs, the authors have considered it worthwhile to evaluate “collective CSE” as a group-level competency indicator of team creativity output.

Research indicates that team creativity climate is as an essential intervening variable stringing diverse team composition, team processes and team creative output (e.g. Dong et al., Citation2017). From a knowledge acquisition and dissemination perspective, creativity climate drives team innovation and creativity (Ghosh & Tripathi, Citation2021). Understanding such cultural and behavioural enablers/inhibitors are the topmost priorities of a knowledge-intensive SME (Nunes et al., Citation2006).

Keeping in view that a “better-contextualized TM research” incorporates boundary conditions that increase the generalizability of the research findings (Teagarden et al., Citation2018), the present study examines the moderating role of age and job tenure in the CSE and team creativity climate relationship. Analysis of such effects can give insights into the boundary conditions underlying the creative process of diverse teams (Straube et al., Citation2018).

The following research questions were formulated to understand how CCSE as a team-level perceptual construct helps in identifying a group’s creative talent (perceived team’s creativity output as proxy) in SMEs and facilitate managers/owners in designing an effective team composition.

Can CCSE act as a group-level predictor of team creativity output?

How the climate of creativity influences CCSE and TCO relationship?

Under what conditions, a group faultline can be beneficial for a team’s creative performance?

Considering human psyche and their work environment preference, identifying and developing talent for creative performance is a challenging task. The current research has the potential to contribute to the limited literature on creative self-efficacy and team creativity in the talent management area. Applying the group’s faultline-strength analysis, the present article investigates how team members’ compositional attributes (age and job tenure) moderates the relationship between CCSE and team climate. A High sub-group separation (concerning age and job tenure attributes) of team members is beneficial in a high CCSE team, whereas a homogeneity in age and tenure is desirable when a team’s CCSE is low. As a team’s creative efficacy shape the collective mental model about immediate it’ssocial context, team climate of creativity is considered as a mediator in the relationship between CCSE and TCO. Our results show how group faultlines strength can significantly strengthen or dampen the existing team climate and team creativity output within SMEs, thus, creating a strong basis for firm owners or managers to align teams for improved team output.

The structure of the article is as follows: Section 2 highlights the issues of SMEs regarding talent management in the context of high-power distant countries like India. A multi-theoretical support has been provided to augment the hypothesis formed. Section 3 elaborates the research methodology adopted. The section encompasses the sample collection procedure, reliability and validity of the constructs, team-level aggregation of creative self-efficacy and perceived team creativity output, triangulation of manager’s score on criterion variable and merging with team-level score, common-method bias test and the process for faultline determination. Section 4 highlights the results of hypothesis tested using PLS-SEM. An elaborate discussion on the results is also provided. Section 5 encompasses concluding remarks along with theoretical and practical implications of this study. Section 6 addresses the limitations and future directions of the research.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses formulation

Emerging Indian market and the role of SMEs

The micro-small-medium enterprises (MSME) or in general SME sector contributes 29% to Indian GDP (CII , Citation2019). However, the Indian Government has always focused on building SMEs’ ecosystem with “an external-fit” perspective that dominates all its significant policies and initiatives. The policies highly ignore the necessity to develop SME’s internal capabilities to innovate products and services. Due to the acute resource limitations in an emerging market, SMEs are suggested to adopt a “knowledge based-view” to boost innovation (Filatotchev et al., Citation2009). Research indicates that SMEs can leverage their informal firm culture by creating a creative environment where new and novel ideas can embellish (Zenger & Lazzarini, Citation2004). Wealth creation by patenting or transference of knowledge on “proprietary assets” is a competitive advantage of knowledge-intensive SMEs operating in an emerging market. The adoption of such a strategy opens up avenues for their internationalization opportunities through collaboration.

Indian knowledge-driven industries with a highly diversified and qualified workforce often face criticisms for producing inferior quality products and services. Moreover, research suggests that one of the primary reasons for attrition in the Indian knowledge-intensive sector is less conducive work environment (Budhwar & Bhatnagar, Citation2007). Most of the Indian employees generally suffer from excessive “dependency proneness” (Sinha, Citation1970) and favour “family culture” (Hampden-Turner & Trompenaars, Citation2011) to prevail in the workplace, especially during uncertain times. Indian talent management issues emerge when such a work-psyche interacts with the western-influenced HR practices. In SMEs such conflicts are frequent. The western HR philosophy rests on KRAs that emphasize individual goals and achievements for a successful career progression (Latukha & Selivanovskikh, Citation2016), whereas in SMEs a more informal and a collective-orientation is preferred (Festing et al., Citation2013; Valverde et al., Citation2013). In an informal work environment, categorizing selected few as “stars” can dampen other employees’ morale and engender bitterness among peers (DeLong & Vijayaraghavan, Citation2003).

Theoretical foundation

Makram et al. (Citation2017) suggested that as TM has achieved a certain level of maturity, researchers must shift from understanding talent management practices to conceptualizing the practice of talent management, which is more of a “context-based strategic outlook” of TM. The first step of such transformation is to adopt a specific TM approach - inclusive or exclusive (Tansley, Citation2011). Digressing from the RBV perspective where the focus is to develop specific talented individual and create a “workforce differentiation”, the present article has focused on an inclusive TM approach that primarily emphasizes a group of employees to achieve “good” performance levels and satisfaction (Bothner et al., Citation2011).

From an I/O psychology perspective, to understand the “practice” of talent management, exploration of organizational ‘mindset’ much like the organizational culture is needed (e.g. Chuai et al., Citation2008). Therefore, adhering to the philosophy of an inclusive approach to talent management, the authors believe that perceptions of individuals within a sub-context (group) may help the researchers to analyse the contextualized TM paradigm where important interactions between individuals and their contexts may reveal useful insights. Aligning with the individual perspective, the theoretical basis of the article rests on social cognition theory (Bandura, Citation1986) which suggests that an individual’s cognition, behaviour and environmental context interact to determine his actions. The self-belief about one’s creative skills (creative self-efficacy) affects the person’s motivation to control the environment and accomplish creative goals (Guan & Huan, Citation2018).

From a team dynamics perspective, the article has deep connotations to social-exchange theory (Blau, Citation1986) which states that actors involve in the process of maintaining mutual relationships with others in expectation of receiving a reward (monetary or non-monetary). Based on the level of an individual’s creative self-efficacy, he/she may proactively seek knowledge acquisition from other team members and expect support, recognition and reward for performing creative tasks. In turn, such social exchanges which are task-focused enhance employees’ mastery experiences.

In the TM paradigm, principles of social cognition and social exchange theory have been observed in explaining employee’s psychological contract (e.g. Guest & Conway, Citation2002). We assume that a team member’s cognitive self-inducement (e.g. creative self-efficacy) helps to develop a psychological contract with his/her team, leading to a favourable or unfavourable team climate perception. Aligning with the concept of the interactionist model of creativity (Woodman & Schoenfeldt, Citation1990), we can summarise that the interaction between an individual’s creative efficacy and his/her team climate perceptions, jointly influence team creativity.

Based on HRM and inclusive TM literature, McDonnell and Collings (Citation2011) suggested a psychologically safe climate for an individual’s talent development. In turn, it benefits a group or an organization as a whole. Recent HRM literature has also called for finding significant factors responsible for a positive team climate and subsequent group effectiveness (Kim et al., Citation2020).

In reality, most teams are heterogenous in terms of demographic attributes leading to intragroup conflicts which dampen the psychological safe climate. From a team conflict management perspective, the article has applied the concept of team faultlines which are "hypothetical lines … may split a group into subgroups based on one or more attributes" (Lau & Murnighan, Citation1998). The authors have examined the boundary conditions of team faultline to understand how the shared perception of team climate of a creative self-efficacious team is formed.

Importance of self-efficacy at group-level

Team members who share quality task and social relationships with team mates experience high exchange of ideas and constructive feedback (Liden et al., Citation2000; Seers, Citation1989). However, what fundamental elements constitute such group’s work-related competence has not dealt with much rigour (Kauffeld, Citation2006). There is still a lack of identification of potency or competency indicators at group-level (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2014).

Though self-efficacy has been considered as a dimension of competency (Boyatzis, Citation1982), it is rarely explored within the talent management paradigm. A few prominent research across countries have suggested that efficacy beliefs should be analysed at team-level considering collective efficacy about their team’s competence (e.g. Moritz & Watson, Citation1998; Zaccaro et al., Citation1995). It was observed that self-efficacy and collective self-efficacy are not isomorphic and share only a moderate correlation (Jex & Bliese, Citation1999).

Collective creative self-efficacy and team creativity output

Employees having higher creative self-efficacies tend to set higher creative goals for themselves (Gong et al., Citation2009). However, as creativity is moderated by contextual factors, a dialectical thinking style of a team leader (Han & Bai, Citation2020) or team members helps to channelise an individual’s or a team’s effort towards creativity.

Team composition variables that vary across team members are of high interest to group researchers. Such variables provide a context where team beliefs and processes emerge (Barrick et al., Citation1998). Concerning the contextual perspective of TM in SMEs, employee perceptions and beliefs act as deep-level (not readily detected) team composition variables and can play a significant role in a team’s creative performance.

A team context encompasses social and task-related interactions and shared experiences (Ghosh et al., Citation2019; Zaccaro et al., Citation1995). Team members’ behaviours, attitude and opinions are mutually influenced through team member interactions that may turn a group into several disintegrated units or integrate it into a unified system (Bergius, Citation1976). When there is a homogeneity of team member’s beliefs on creative skills, lack of competence of one member can be compensated by others without compromising the creative output of the team (Tripathi & Ghosh, Citation2020). Collective creative self-efficacy (CCSE) represents a team’s shared creative efficacy beliefs that encompass the team’s social and task-relevant context. Team-level research has found that collective efficacy positively affects team performance (e.g. Gully et al., Citation2002). As creative self-efficacy depends on social-contextual factors (Christensen-Salem et al., Citation2020), we argue that CCSE of a team has different effects on team creativity output depending on organizational structure, values, goals and motivation. As SMEs are quite different from MNEs in the above parameters, it is worthy of investigating the CCSE and team creativity output relationship in such firms. Moreover, considering the paradoxical mindset of Indians (situation led collectivistic or individualistic behaviour) and their dependency-prone work attitude (Sinha, Citation2014), investigation of a group’s collective orientation effects on its creativity output may provide useful insights in the development of a group-level competency indicator for team creativity.

H1: Collective creative self-efficacy of a team is positively related to the team creativity output

Collective creative self-efficacy, team creativity climate and team creativity output

Researchers have established the importance of people-orientation (individualistic or collectivistic) in the CSE-creativity link (Shin et al., Citation2012). As China is a collectivistic country, a weak relationship was found between individual CSE and creativity. It was observed that the strength of CSE increases when people-orientation shifts from a collectivistic mindset to an individualistic one. India has both collectivistic and individualistic traits (Hofstede, Citation2001) and therefore, it will be interesting to examine the effect of CCSE on team creativity output and the role played by the nature of immediate work context. In knowledge-intensive firms, dynamic capability building embeds in its culture of openness and experimentation where team-based structure and their collective-orientation play a significant role (Chiva & Alegre, Citation2009). The social and emotional processes that are involved in the collective beliefs of team members about their immediate work environment result in an emergent motivational state (e.g. psychological empowerment) that drives creativity. Team climate for creativity creates a competitive yet co-operative attitude among peers that facilitate generation of fresh ideas and novel methods for successful task accomplishment (Gisbert-Lopez et al., Citation2014). The presence of creativity climate encompasses higher-level organizational capabilities such as inclusive leadership, team learning, shared vision, and customer responsiveness that help building dynamic team capabilities (Oltra & Vivas-Lopez, Citation2013). Building a creativity climate for innovation can be the best strategy for resource-constrained knowledge SMEs (Zenger & Lazzarini, Citation2004).

Recent research suggests that the quality of social and task-related interactions and shared experiences influence the psychological empowerment among individuals (Ghosh et al., Citation2019). High psychologically empowered and creative self-efficacious team members perceive high team creative output. It indicates that team climate of creativity act as a group-level mechanism to consolidate the views and perspectives of team members and directs them towards an intended goal (Tripathi & Ghosh, Citation2020). We posit that CCSE influences the shared perception of team creativity climate, which in turn affects team creativity output. Therefore, to test the same, the following hypothesis has been framed.

H2: Team creativity climate mediates the positive effect of CCSE on team creativity output

Collective creative self-efficacy and team climate of creativity: the role of faultlines

Team composition based on team-member characteristics crucially determine the effectiveness of team learning. Group members may have multiple characteristics or dimensions on which they differ simultaneously and give birth to group faultlines (Lau & Murnighan, Citation1998). Faultlines are hypothetical dividing lines potentially splitting a team into two or more subgroups based on team members’ demographical and/or attitudinal/despositional variables. The more correlated team member characteristics are (e.g. men above 40 years), stronger is the faultline (e.g. gender and age) resulting in homogenous subgroups formation (Lau & Murnighan, Citation2005; Pelled et al., Citation1999). This partition between distinct subgroups within a group can trigger different team dynamics (Bezrukova et al., Citation2009). Faultlines affect team processes and outcomes (Lau & Murnighan, Citation1998) and studies have proved that they have detrimental effects on group performance (Meyer & Schermuly, Citation2012; Sawyer et al., Citation2006).

It has been observed that when new managers entered an existing group, age and group tenure differences with existing members created a faultline that affected group dynamics (Hutzschenreuter & Horstkotte, Citation2013). A group may consist of members with high creative self-efficacies, but when faultlines based on factors such as age, gender, tenure and education-level come into play, the team may suffer from lack of informational elaboration (Homan et al., Citation2007). An identified talented group may suffer from unobservable faultline effects that result in a premature cognitive closure of team members (Salazar et al., Citation2012). Few team members based on age and experience similarity can form small sub-groups and may demonstrate non-cooperation and reluctance towards sharing unique task-related information to others. However, few studies have revealed the positive and negative effects of faultlines based on demographic (e.g. age, gender and ethnicity) and task-related (job/organizational tenure and educational background) faultlines. Bio-demographic faultlines hinders team performance (e.g. Hutzschenreuter & Horstkotte, Citation2013) whereas task-related faultlines (Tierney & Farmer, Citation2002) strengthens team’s performance.

A team’s CCSE represents shared beliefs pertaining to creative self-efficacy of the team as a unit (van Knippenberg et al., Citation2010). We posit that in case of high CCSE, senior employees in the team will act as role models to the junior employees (w.r.t age and tenure). In this context, junior employees perceive a nurturant-task style of guidance (Sinha, Citation1984) and seniors experience different, fresh perspectives from high creative self-efficacious juniors. Such a work-execution model creates a strong shared mental model of team creativity climate. However, in low CCSE scenario, the salience of group membership based on creative self-efficacy beliefs would be attenuated in the presence of high faultline strength. The team may suffer from lack of informational elaboration where subgroup(s) based on age and experience similarity can show non-cooperation and may withhold task-relevant unique information. When a team has low CCSE, subgroups based on age and experience can further dampen team creativity climate.

H3a: Faultline strength (age and job tenure) positively moderates the relationship between CCSE and shared team climate of a team such that the relationship is weak in case of low faultline strength and strong in case of high faultline strength.

As discussed earlier, CCSE is assumed to have a positively relation with team creativity output. As per our conceptual model (), the strength of the positive effect of collective beliefs on TCO via TCC is dependent on the faultline strength. However, as we have hypothesized that faultline strength moderates CCSE and TCC relationship, the mediating effect of TCC will also be influenced. We argue that under a high faultline strength scenario, the mediating effect of TCC will strengthen and weaken under a low faultline strength condition. To test the salience of the moderated mediation effect on CCSE and TCO relationship, the following hypothesis has been formed.

H3b: The mediating effect of TCC is moderated positively by age-tenure faultline strength of a team

3. Research method

Sample and data collection procedure

A stratified purposive sampling of knowledge-intensive SMEs was done based on authors’ convenience and city preferences. Twenty-four organizations were randomly selected from four different metropolitan cities. Out of 24 firms surveyed during 2018–2019, 9 firms belonged to small-firm category and the rest were mid-sized organizations. Our sample excluded micro-level firms (<20 employees) and had considered only small (>20 but <100 employees) and mid-sized firms (>100 and <500 employees). The data sample caters to both service and product firms spanning across IT and IT-enabled services, R&D, advertising, electronic gadgets manufacturing and KPOs. All the employees surveyed possessed unique skillsets and work knowledge or information that are valuable for the team’s output. Our firm-level categorization was based on the firm’s employee size as it is highly correlated with the degree of HR orientation in the firm.

Work-groups from each organization were randomly selected and teams with <3 members were excluded from the sample. Voluntary participation in the survey was sought from team members and the manager/leader of the team. The first data sample 1 (N1 = 303) consisted of responses from team members (junior and middle-level employees) of all the teams surveyed (in total there were 73 teams). The second data sample 2 comprised team leader’s/manger’s responses (N2 = 73) about their team’s creativity output. The average age of the employees in sample 1 was 29.2 years (SD = 6.2 years), and the average work-experience was 5.27 years (SD = 4.9 years). The average age of the team managers (sample 2) was 36.28 years (SD = 7.18 years) and the average work experience was 11.97 years (SD = 6.27 years).

Common-method bias test

The extent of method variance (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) was tested using Harman’s single-factor test on sample 1. The first largest factor accounted less than 50% variance indicates less likelihood of CMB presence. Moreover, the inter-correlation between the variables was less than 0.9 (Bagozzi et al., Citation1991) and VIF < 3.3 (Kock, Citation2015) for each construct confirms the minimal impact of CMB.

Self-reports are a source of common method bias that inflates the covariation between predictor and criterion. This phenomenon has been observed widely when the criterion is individual creativity or team creativity or output (Hülsheger et al., Citation2009). This inflation might be attributed to, for example, the respondents’ tendency to maintain consistency in their responses, socially desirable responding, and leniency biases towards creativity performance (c.f. Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

By using two different data sources (team members and team managers) for measuring the dependent variable (team creativity output), we attempted to reduce the self-reported bias and social desirability effect to the extent possible and achieve a realistic measure of team creativity output (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012).

Measures

Creative self-efficacy

A three-item scale, developed by Tierney and Farmer (Citation2002), was used to measure creative self-efficacy. The coefficient alpha value of the construct was .86.

Team climate

The 14-item short version of the original Team Climate Inventory (Anderson & West, Citation1994). This version was developed by Kivimaki and Elovainio (Citation1999) and has shown acceptable psychometric quality where the α coefficients ranged between .79 and .86 (Kivimaki & Elovainio, Citation1999). Factor Analysis of the items was carried out which yielded 3 factors and the coefficient alpha values of those factors were .92 (Team Unity and Support for Innovation), .86 (Vision), .84 (Task Orientation).

Team creativity output

The items for this scale were adopted from Hanke (Citation2006). The original items were adopted from Ford and Gioia (Citation2000). The items were developed to specifically tap into both novelty and usefulness dimensions. According to Hanke (Citation2006), the scale worked remarkably well and validated the fact that creativity output is a two-factor construct. The coefficient alpha values of the dimensions were .82 (Novelty) and .82 (Usefulness).

To control the confounding effects on team creativity output, additional relevant variables viz., team size (Woodman et al., Citation1993) and organization size(DeGraff & Lawrence, Citation2002) were included in the analysis.

Aggregation to team level

Using within-group agreement (rWG(j)) technique (Bliese, Citation2000), we tested that individual scores on CSE can be aggregated to measure collective creative self-efficacy (CCSE) of the group (F = 3.09, p < .001; average rWG(j) = .87; ICC(1) = .34; ICC(2) = 0.68). Similarly, team climate perceptual scores (TCL) of individual employees were aggregated at group level to reflect the shared mental model of the group (F = 4.90, p < .001; average rwg = .77; ICC(1) = .48; ICC(2) = 0.80). Individual perception of their team creativity output is aggregated to team-level to reflect the shared perception of creativity output (F = 2.8, p < .001; average rwg = .66; ICC(1) = .30; ICC(2) = 0.64; Bliese, Citation2000).

To achieve a realistic measurement of team creativity output, the average of aggregated group score and team manager score was done. However, before merging the two samples (sample 1—aggregated group score on creativity output (n1 = 73) and sample-2 manager’s score on group’s creativity output (n2 = 73)), we ensure that there is a significant positive correlation between two creativity output ratings and no significant difference exists in the perceptions of creativity output on each of its dimensions viz., novelty and usefulness (ANOVA result for usefulness: F = 2.2, df = 1, n.s; novelty: F = .02, n.s).

Faultline strength determination

Faultline analysis strength based on creative self-efficacy and tenure in the organization was calculated using asw.cluster package (version 2.10) in statistical software R (version 3.1.2). Using a wrapper function faultlines() in the package, faultline strengths of group’s faultline is calculated based on agglomerative and partitioning clustering algorithms as suggested by Meyer and Glenz (Citation2013).

4. Results and discussion

Convergent and discriminant validity

SEM-based PLS was used for testing the hypotheses. Here, the concern is more with identifying potential relationships than the magnitude of those relationships, and thus PLS-SEM is preferred to CB-SEM for path estimation. Moreover, PLS-SEM has been used extensively in research across disciplines and found to be useful for estimating models that have multi-dimensional constructs (Marcoulides et al., Citation2009) and the outcome variable is reflective (Lowry & Gaskin, Citation2014). Research indicates that there is no difference in model estimate parameters between PLS-SEM and CB-SEM when the sample size is low (<300).

shows the item reliability where all item loadings are more than 0.7 with an exception of one item COU4. Cronbach-alphas, Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values indicate that the constructs have sufficient reliability and convergent validity. As Fornell-Larcker criterion for discriminant validity biases the test in presence of high factor loadings, heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio is used (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The ratio is the average of item correlations across constructs relative to the (geometric) mean of the average correlations for the items measuring the same construct. depicts the discriminant validity between the constructs at the individual and group level. A lower score less than 0.85 is suggested to demonstrate discriminant validity among the constructs (Henseler et al., Citation2015). Therefore, from the results, it is clear that the constructs did not suffer from low discriminant validity issue at individual and group-level.

Table 1. Overall reliability of the constructs and factor loadings of indicators.

Table 2. Measurement model evaluation (discriminant validity using Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio).

Hypotheses testing

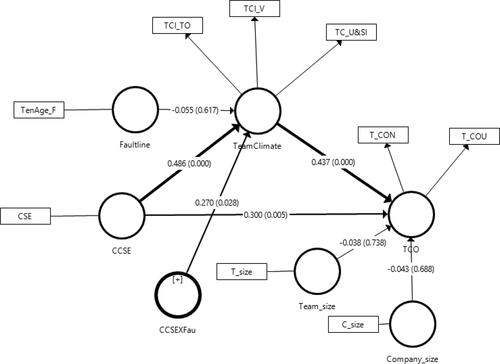

After the measurement model is validated, hypotheses were tested assessing the path co-efficients in the structural model (refer to ). The significance of the path coefficients is tested through bootstrapping technique.

As points out, collective creative self-efficacy (CCSE) has a direct significant effect on team creativity output (TCO) (β = .30, BCa [.09,.48], p < .01). Therefore, hypothesis 1 is supported.

Table 3. Structural path coefficients.

Indirect effect (path a X b in ) of CCSE on TCO through team climate is found to be significant (β = .22, BCa [.10,.37], p < .01). As the direct effect (CCSE-TCO) is also significant, we conclude the positive partial mediation effect of team climate on TCO. Hypothesis 2 is thus supported.

The blindfolding algorithm in PLS-SEM was executed to get the Stone-Geisser’s Q2 value. It is an indicator of the predictive relevance of the exogeneous constructs on endogenous variables. The larger the values from 0 and <1, better is the predictive relevance. The Q2 values in cross-validated redundancies for our endogenous constructs are as follows: Team creativity output (TCO) = 0.20 (moderately high); Team Climate = 0.27 (moderately high).

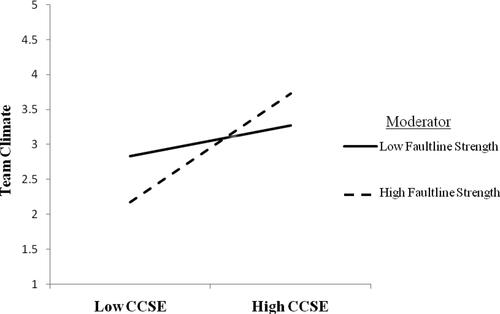

We tested the moderation effects of faultline strength using PLS-SEM and also through Process Macro by adopting product-interaction approach (Aiken et al., Citation1991). In PLS-SEM, the interaction term (CCSE X Faultline) is found to have significant effect on team climate (TCL) (β = .30, BCa [.12, 2.5], p < .01). Executing Process Macro, which uses OLS regression to test moderation, yielded significant result for the interaction term (unstandardized β = 1.46, BCa [.44, 2.49]). Refer for the interaction diagram. Therefore, faultline strength moderates the CCSE-TCL relationship.

The general path-analytic framework (Edwards & Lambert, Citation2007) was applied to test the conditional indirect effects of CCSE at various values of faultline strengths (high and low). depicts that the indirect effect of CCSE is significant only at high faultline strength (High: b = .52, p < .01) indicating that the mediating effect of TCC is stronger when faultline strength is higher. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 b is partially supported.

Table 4. Moderated-mediation effects.

PLS-SEM GOF index is calculated for endogenous constructs (TCO = 0.51 and team climate = 0.55) as per the guidelines provided by Akter et al. (Citation2011). As GoF > 0.36, it indicates that our model is well fitted.

Discussion

The support of hypothesis 1 proves that CCSE acts as an indicator of a group’s creative talent. However, its effect on team’s creativity output is largely mediated by team creativity climate. Marginally high variances on team creativity output by CCSE was observed through the climate dimensions viz., Team Unity and Support for Innovation (indirect effect = .25, p < .01) and Team Vision (indirect effect = .23, p < .05). Therefore, support of Hypothesis 2 indicates that the group-level competency effect is context-sensitive. High CCSE helps a team in the pursuit of a challenging vision or a goal where team’s unity and support for creativity facilitate taking calculated risks—an important pre-requisite for bringing novelty in products and services (Amabile et al., Citation1996; Ekvall & Ryhammar, Citation1999). Previous research has found a strong positive relation between participative safety climate and team creativity (Amabile et al., Citation1996) where high participative safety increases a team member’s likelihood of proposing an unusual or risky idea without invoking any negative affect of other members.

Recent research by Damperat et al. (Citation2016) stated that individual creative self-efficacy has no impact on the perceived originality of a product concept. On the other hand, collective creative self-efficacy (CCSE) significantly influences the perceived originality of the proposed product concept. This finding is aligned with our research where collective creative self-efficacy significantly predicts the team’s creative outcome. Moreover, CCSE forms a shared positive (negative) perception of team creativity climate which facilitates (or hinders) the perception of overall team creative output. One of the advantages of using CCSE as a team talent management indicator is that it drives building creative self-efficacy of individuals as well (Damperat et al., Citation2016).

The faultline examination in the model has improved our understanding of the “diversity paradox” emerging from the “double-edged sword” perspective of workforce diversity. Existing diversity research has yet to decipher the right team composition where cohesion and informational advantage co-exists in a heterogenous team (Srikanth et al., Citation2016). The present study has relevance to the HR talent management practices as our analysis revealed that heterogeneity in age and experience (job-tenure) is preferred in a team where CCSE is high. However, in a low CCSE scenario, team climate perceptions would be further dampened in the presence of age and experience differences in team members.

5. Conclusion and implications

As “talent” is viewed differently across business disciplines, HRs approach the challenges of TM from different mental models. To understand TM holistically, Boudreau (Citation2013) has suggested more research on SMMs (shared mental models) of various teams across business disciplines. Such an approach may act as a theoretical basis for retooling and reframing HR decisions across organizations.

In knowledge-intensive SMEs, teamwork plays a critical role in their success. However, due to the resource-constrained characteristic of SMEs, talent management practices need a holistic approach in identifying “key groups” or “talent groups. In contrast to the conventional view of individual-focused competency, the present article proposes collective creative self-efficacy as a cognitive group-level competency indicator for SMEs. With a significantly high talent crunch and an increase in employee turnover in Indian knowledge-driven industries, HR managers are challenged to identify and retain talent in their organizations. Moreover, an improper task or group allocation lowers the self-confidence and perception of a learner (Kak et al., Citation2001). The present article has tried to address such issues by identifying collective creative self-efficacy as a measure to improve team climate and increase team creativity output. The collective self-efficacy factor has been found to influence a team’s willingness to create conditions (team creativity climate) for creative performances.

The article has also encapsulated both cognitive and demographic factors of individuals working in Indian SMEs to determine effective team composition. In an emerging market, innovation is the key to competitive advantage. The rapid employee turnover creates instability in the workforce composition of SMEs (Stokes et al., Citation2016) resulting in a poor team-level output. Under such a situation, team members’ low morale creates a barrier in knowledge creation and unique information sharing within teams. The present article has reinforced that in an emerging market, making a strong creativity climate for innovation is the best strategy for knowledge-intensive SMEs. Team composition based on creative self-efficacy can help SMEs to build a shared mental model of a positive creativity climate.

Traditional talent management practices have focused only on selected identified talents for their development and growth, and thereby, unintentionally create a climate of exclusion for others (Gelens et al., Citation2013). When working as a team, hand-picked talents may face cooperation issues from others because of perceived competency threats (e.g. Guillaume et al., Citation2014). Therefore, the identification of group-level talent factors enables HRs to develop group-level skill development interventions and curtail the ill-consequences of the Pygmallion effect. In the Indian work context, where individual employees are keen to demonstrate their achievements and accomplishments over team needs (Times of India, Citation2015), group-level talent identification and work allocation may be beneficial.

From a global talent management perspective, capability building in developing “proprietary assets” lies in the production of creative products and services which can open avenues for internationalization of knowledge-intensive SMEs. The action of investing in high technological equipment/software for creative output can be supplemented by knowledge acquisition and dissemination through team learning. As SMEs nature of work demands team competence, managers can develop self-directed teams where creative self-efficacy is one of the bases of such team formation.

Theoretical implications

Considering the amount of research conducted in the area of Talent Management, little focus has been paid to theory development (Collings & Mellahi, Citation2009). The present article is one of the recent attempts that addresses group-level competency identification as a basis for talent management. Most of the past literature on group competence has focused on communication (Barge & Hirokawa, Citation1989), teaching and evaluation (Neff et al., Citation2019) and initiatives (Jones & Voorhees, Citation2002) among others. None of such studies to the best of our knowledge had a clear focus on creative talent management or its impact on team’s creative output. Second, our article contributes to the emerging field of collective self-efficacy in the domain of psychology and group behaviour (Hong et al., Citation2019; Nijs et al., Citation2019). The article extends the concept of psychological contract theory to explain the implicit bond between team members formed from the perception of collective creative self-efficacy—a cognitive group-level talent indicator. The team climate perception is just a manifestation of that implicit exchange relationship. Lastly, we adopted SMM (shared mental model) view towards talent development as suggested by Boudreau (2013). This can act as a theoretical basis for retooling and reframing HR decisions across organizations. It is when groups’ competency levels are identified, their needs and preferences can be tailored for reward, development and learning practices (Cheese et al., Citation2007).

HR implications

The modern HRs are concerned about managing teams’ creative performance in recent years (Ardito & Petruzzelli, Citation2017). The competencies of most teams in organizations are different and diverse. The assessment of creative self-efficacy on these competencies at the individual-level might be useful in the development of those teams. Moreover, collective creative self-efficacy is a more generalized self-efficacy measure to measure success of teams. In alignment with the findings by Park et al. (Citation2021), we agree that through specialized trainings on creative thinking, HRs can induce self-confidence in group members that results in innovative team performance. Moreover, to sustain such a team performance, CCSE can act as an enabler to positive team climate, especially to psychological safety of members during this pandemic crisis. Lastly, team composition for such creative group performance has to be well determined. In addition to the findings by Park et al. (Citation2021) which suggest that “high CSE may hamper potential interactions among team members”, we suggest that performance can be impeded in a team with high CCSE and a low faultline strength because of competency threats from same age and job tenured peers. Therefore, from a talent management perspective, our finding on faultlines can act as an important reference to the HRs in forming teams. We suggest that a “potential talent” may not be assigned to a team where members have low collective creative self-efficacy beliefs and share a high separation on age and work experience.

From an international HRM perspective, organizations need to identify certain stable and dynamic individual competencies (e.g. personality, self-efficacy etc.) of individuals who can reap the benefit of cross-cultural talent development initiatives (Tarique & Schuler, Citation2010). The model presented in the article would provide a foundation for the SMEs in the emerging economies to consider the individual as well as collective dispositional characteristics as indicators of internationalization readiness.

According to Kauffeld (Citation2006), team climate (team unity and support for innovation) shares the strongest correlation with competence in knowledge-driven firms. Therefore, HR practitioners can design interventions to measure and enhance collective creative self-efficacy of a team that will serve two purposes: a) serve as a competency indicator for making the team a self-directed one, and, b) strengthen the team creativity climate for producing creative deliverables. SME owners or managers have sufficient incentive to retain talent by focusing on team’s collective creative self-efficacy as it not only improves team creativity but also reduces employee turnover. Adoption of such a strategy in SMEs (especially, Indian SMEs) where creativity output is poor (Dutta et al., Citation2018), would help in developing collaborative working models for increasing internationalization opportunities in emerging markets.

6. Limitations and future research

Our article has several key limitations which can serve as opportunities for future research.

This study has been limited to only one country- India. As a result, the findings may be limited to a certain set of emerging markets where both collectivistic and individualistic employee goals exist. For instance, our results may corroborate with countries such as BRICs where the workplace climate is considered to be similar, especially in the SME work-context. The findings may differ in a pure collectivistic or individualistic cultural setting. It is to be noted that our findings are consistent with the knowledge-intensive small and medium firms. The validity of the findings can be tested in different business sectors and other emerging markets for greater generalizability.

As there are many more categories of industries (with different characteristics) and quite a few knowledge-intensive SMEs in India, a larger sample size is always desirable. It would be interesting to observe and categorize findings based on manufacturing and service firms in emerging markets. As noted by Pertuz et al. (Citation2020), service providers (SMEs) in emerging markets related to telecommunications, media and IT generally emphasize “resource mobilization” approach (e.g. Tidd & Thuriaux-Alemán, Citation2016) in their innovation-oriented talent practices. Further research can focus on such an approach to identify TM practices that are effective indicators to organizational, relational, and innovative outputs. TM practices must provide mechanisms through which resources are allocated in tasks, teams or projects that are aligned with innovation and firm’s strategy. A few important areas in SMEs that can be explored are project management, organizational creativity and knowledge management practices.

The present model did not control for industry-specific contextual factors that may have an impact on team climate, such as, long working hours in IT industry and the deadline-meet pressures. Such factors may be valid for other sectors such as the healthcare and hospitality where service delivery expectations are both unique and high.

Supplemental Material

Download PNG Image (42.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [GN], upon reasonable request.

References

- Acs Z. J., & Varga, A. (2005). Entrepreneurship, agglomerations, and technological change. Small Business Economics, 24 (3), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-1998-4

- Ardito, L., & Petruzzelli, A. M. (2017). Breadth of external knowledge sourcing and product innovation: The moderating role of strategic human resource practices. European Management Journal, 35(2), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2017.01.005

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

- Akter, S., D’Ambra, J., & Ray, P. (2011). An evaluation of PLS based complex models: The roles of power analysis, predictive relevance and GoF index [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings of the 17th Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS2011) (pp. 1–7). Association for Information Systems.

- Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154–1184.

- Anderson, N., & West, M. A. (1994). Team climate inventory: Manual and user’s guide. ASE.

- Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421–458. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393203

- Bai, Y., Yuan, J., & Pan, J. (2017). Why SMEs in emerging economies are reluctant to provide employee training: Evidence from China. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 35(6), 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242616682360

- Banerjee. (2020). Redefining SMEs will give the sector a boost. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/redefining-msmes-will-give-the-sector-a-boost/article30505802.ece

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social-cognitive view. Prentice-Hall.

- Barge, J. K., & Hirokawa, R. Y. (1989). Toward a communication competency model of group leadership. Small Group Behavior, 20(2), 167–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649648902000203

- Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., Neubert, M. J., & Mount, M. K. (1998). Relating member ability and personality to work-team processes and team effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.377

- Becker, B. E., & Huselid, M. A. (2006). Strategic human resources management: Where do we go from here? Journal of Management, 32(6), 898–925. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306293668

- Bergius, R. (1976). Social psychology [Sozialpsychologie]. Hofmann and Campe.

- Bezrukova, K., Jehn, K. A., Zanutto, E. L., & Thatcher, S. M. (2009). Do workgroup faultlines help or hurt? A moderated model of faultlines, team identification, and group performance. Organization Science, 20(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0379

- Biswas-Diener, R., Kashdan, T. B., & Minhas, G. (2011). A dynamic approach to psychological strength development and intervention. The Journal of PositivePsychology, 6, 106–118.

- Blau, P. (1986). Exchange and power in social life. Routledge.

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K.K. Klein & S. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

- Bothner, M., Podolny, J. M., & Smith, E. (2011). Organizing contests for status: The Matthew effect versus the Mark effect. Management Science, 57(3), 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1100.1281

- Boudreau, J. W. (2013). Appreciating and ‘retooling’ diversity in talent management conceptual models: A commentary on “The psychology of talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 286–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.08.001

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1982). The competent manager: A model for effective performance. John Wiley & Sons.

- Budhwar, P. S., & Bhatnagar, J. (2007). Talent management strategy of employee engagement in Indian ITES employees: Key to retention. Employee Relations, 29(6), 640–663.

- Cappelli, P., & Keller, J. R. (2014). Talent management: Conceptual approaches and practical challenges. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 305–331. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091314

- Chen, G., & Bliese, P. D. (2002). The role of different levels of leadership in predicting self-and collective efficacy: Evidence for discontinuity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.549

- Cheese, P., Thomas, R. J., & Craig, E. (2007). The talent powered organization: Strategies for globalization, talent management and high performance. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Chiva, R., & Alegre, J. (2009). Organizational learning capability and job satisfaction: An empirical assessment in the ceramic tile industry. British Journal of Management, 20(3), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00586.x

- Christensen-Salem, A., Walumbwa, F. O., Hsu, C. I. C., Misati, E., Babalola, M. T., & Kim, K. (2020). Unmasking the creative self-efficacy–creative performance relationship: The roles of thriving at work, perceived work significance, and task interdependence. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1710721

- Chuai, X., Preece, D., & Iles, P. (2008). Is talent management just ‘old wine in new bottles’? Management Research Review, 31(12), 901–911.

- CII (2019). Making Indian MSMEs globally competitive. https://cii.in/Publications

- Collings, D. G., Scullion, H., & Vaiman, V. (2011). European perspectives on talent management. European Journal of International Management, 5(5), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2011.042173

- Collings, D. G., & Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.04.001

- Damperat, M., Jeannot, F., Jongmans, E., & Jolibert, A. (2016). Team creativity: Creative self-efficacy, creative collective efficacy and their determinants. Recherche et Applications en Marketing (English Edition), 31(3), 6–25.

- DeGraff, J., & Lawrence, K. A. (2002). Creativity at work: Developing the right practices to make innovation happen. (Vol. 28). John Wiley & Sons.

- DeLong, T. J., & Vijayaraghavan, V. (2003). Let’s hear it for B players. Harvard Business Review, 81(6), 96–102.

- Deshpande, S. P., & Golhar, D. Y. (1994). HRM Practices in Large and Small Manufacturing Firms: A Comparative Study. Journal of Small Business Management, 32, 49–56.

- Dong, Y., Bartol, K. M., Zhang, Z. X., & Li, C. (2017). Enhancing employee creativity via individual skill development and team knowledge sharing: Influences of dual-focused transformational leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(3), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2134

- Dries, N. (2013). The psychology of talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 272–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.001

- Dutta, S., Lanvin, B., & Wunsch-Vincent, S. (Eds). (2018). Global innovation index 2018: energizing the world with innovation. https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/gii-2018-report

- Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22.

- Ekvall, G., & Ryhammar, L. (1999). The creative climate: Its determinants and effects at a Swedish university. Creativity Research Journal, 12(4), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1204_8

- Fernandez-Araoz, C., Roscoe, A., & Aramaki, K. (2017). Turning potential into success: The missing link in leadership development. Harvard Business Review, 95(6), 86–93.

- Festing, M., Schäfer, L., & Scullion, H. (2013). Talent management in medium-sized German companies: An explorative study and agenda for future research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(9), 1872–1893. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.777538

- Filatotchev, I., Liu, X., Buck, T., & Wright, M. (2009). The export orientation and export performance of high-technology SMEs in emerging markets: The effects of knowledge transfer by returnee entrepreneurs. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(6), 1005–1021. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.105

- Ford, C. M., & Gioia, D. A. (2000). Factors influencing creativity in the domain of managerial decision making. Journal of Management, 26(4), 705–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600406

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Thunnissen, M., & Scullion, H. (2020). Talent management: Context matters. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(4), 457–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1642645

- Gelens, J., Dries, N., Hofmans, J., & Pepermans, R. (2013). The role of perceived organizational justice in shaping the outcomes of talent management: A research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.005

- Ghosh, V., Bharadwaja, M., Yadav, S., & Kabra, G. (2019). TMX and innovative behaviour: The role of psychological empowerment and creative self-efficacy. International Journal of Innovation Science, 11(3), 344–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-12-2018-0132

- Ghosh, V., & Tripathi, N. (2021). Perceived inclusion and team creativity climate: Examining the role of learning climate and task interdependency. Management Research Review, 44(6), 849–866. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-02-2020-0093

- Gisbert-Lopez, M. C., Verdu-Jover, A. J., & Gomez-Gras, J. M. (2014). The moderating effect of relationship conflict on the creative climate–innovation association: The case of traditional sectors in Spain. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(1), 47–67.

- Gong, Y., Huang, J. C., & Farh, J. L. (2009). Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.43670890

- Guillaume, Y. R. F., Dawson, J. F., Priola, V., Sacramento, C. A., Woods, S. A., Higson, H. E., Budhwar, P. S., & West, M. A. (2014). Managing diversity in organizations: An integrative model and agenda for future research. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(5), 783–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2013.805485

- Gully, S. M., Incalcaterra, K. A., Joshi, A., & Beaubien, J. M. (2002). A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: Interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 819–832. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.819

- Guan, X. H., & Huan, T. C. (2019). Talent management for the proactive behavior of tour guides. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(10), 4043–4061. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2018-0596

- Guest, D., & Conway, N. (2002). Communicating the psychological contract: An employer perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 12(2), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2002.tb00062.x

- Hampden-Turner, C., & Trompenaars, F. (2011). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding diversity in global business. Hachette.

- Han, G. H., & Bai, Y. (2020). Leaders can facilitate creativity: The moderating roles of leader dialectical thinking and LMX on employee creative self-efficacy and creativity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(5), 405–417. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-02-2019-0106

- Hanke, R. C. M. (2006). Team creativity: A process model [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Pennsylvania State University, PA.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage publications.

- Homan, A. C., Van Knippenberg, D., Van Kleef, G. A., & De Dreu, C. K. (2007). Bridging faultlines by valuing diversity: Diversity beliefs, information elaboration, and performance in diverse work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1189–1199. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1189

- Hong, J. C., Tai, K. H., & Ye, J. H. (2019). Playing a Chinese remote-associated game: The correlation among flow, self-efficacy, collective self-esteem and competitive anxiety. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(5), 2720–2735. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12721

- Hutzschenreuter, T., & Horstkotte, J. (2013). Performance effects of top management team demographic faultlines in the process of product diversification. Strategic Management Journal, 34(6), 704–726. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2035

- Hülsheger, U. R., Anderson, N., & Salgado, J. F. (2009). Team-level predictors of innovation at work: A comprehensive meta-analysis spanning three decades of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1128– 1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015978

- Inamdar. (2016). The impact of culture on innovation in Indian companies. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/impact-culture-innovation-indian-companies-rajiv-inamdar/

- Jex, S. M., & Bliese, P. D. (1999). Efficacy beliefs as a moderator of the impact of work-related stressors: A multilevel study. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(3), 349–361.

- Jones, E. A., & Voorhees, R. A. (2002). Defining and assessing learning: exploring competency-based initiatives. Report of the National Postsecondary Education Cooperative Working Group on Competency-Based Initiatives in Postsecondary Education.

- Kak, N., Burkhalter, B., & Cooper, M. A. (2001). Measuring the competence of healthcare providers. Operations Research Issue Paper, 2(1), 1–28.

- Kauffeld, S. (2006). Self-directed work groups and team competence. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X53237

- Kim, S., Lee, H., & Connerton, T. P. (2020). How psychological safety affects team performance: Mediating role of efficacy and learning behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1581. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01581

- Kivimaki, M., & Elovainio, M. (1999). A short version of the Team Climate Inventory: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72(2), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317999166644

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Krishnan, T. N., & Scullion, H. (2017). Talent management and dynamic view of talent in small and medium enterprises. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.10.003

- Lanvin, B., & Monteiro, F. (Eds.). (2020). The global talent competitiveness index 2020: Global talent in the age of artificial intelligence. ISEAD. https://www.insead.edu/sites/default/files/assets/dept/globalindices/docs/GTCI-2020-report.pdf

- Latukha, M., & Selivanovskikh, L. (2016). Talent management practices in IT companies from emerging markets: A comparative analysis of Russia, India, and China. Journal of East-West Business, 22(3), 168–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669868.2016.1179702

- Lau, D. C., & Murnighan, J. K. (1998). Demographic diversity and faultlines: The compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 325–340. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.533229

- Lau, D. C., & Murnighan, J. K. (2005). Interactions within groups and subgroups: The effects of demographic faultlines. Academy of Management Journal, 48(4), 645–659. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.17843943

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2000). An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 407–416.

- Lowry, P. B., & Gaskin, J. (2014). Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57(2), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2014.2312452

- Makram, H., Sparrow, P., & Greasley, K. (2017). How do strategic actors think about the value of talent management? Moving from talent practice to the practice of talent. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 4(4), 259–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-06-2017-0051

- Marcoulides, G. A., Chin, W. W., & Saunders, C. (2009). A critical look at partial least squares modeling. MIS Quarterly, 33(1), 171–175.

- McDonnell, A., & Collings, D. G. (2011). The identification and evaluation of talent in MNEs. In H. Scullion, & D. Collings (Eds.), Global talent management (pp. 72–89). Routledge.

- McDonnell, A., Collings, D. G., Mellahi, K., & Schuler, R. (2017). Talent management: A systematic review and future prospects. European Journal of International Management, 11(1), 86–128.

- Meyer, B., & Glenz, A. (2013). Team faultline measures: A computational comparison and a new approach to multiple subgroups. Organizational Research Methods, 16(3), 393–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428113484970

- Meyer, B., & Schermuly, C. C. (2012). When beliefs are not enough: Examining the interaction of diversity faultlines, task motivation, and diversity beliefs on team performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21(3), 456–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2011.560383

- Moritz, S. E., & Watson, C. B. (1998). Levels of analysis issues in group psychology: Using efficacy as an example of a multilevel model. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2(4), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.2.4.285

- MSCI. (2020). MSCI emerging markets index. Retrieved March 09, 2021, from https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/index/emerging-markets

- Neff, J., Holmes, S. M., Strong, S., Chin, G., De Avila, J., Dubal, S., … Lemay, E. (2019). The structural competency working group: Lessons from iterative, interdisciplinary development of a structural competency training module. In Structural competency in mental health and medicine (pp. 53–74). Springer.

- Nijs, T., Stark, T. H., & Verkuyten, M. (2019). Negative intergroup contact and radical right-wing voting: The moderating roles of personal and collective self-efficacy. Political Psychology, 40(5), 1057–1073. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12577

- Nunes, M. B., Annansingh, F., Eaglestone, B., & Wakefield, R. (2006). Knowledge management issues in knowledge-intensive SMEs. Journal of Documentation, 62(1), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410610642075

- Oltra, V., & Vivas-López, S. (2013). Boosting organizational learning through team-based talent management: What is the evidence from large Spanish firms? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(9), 1853–1871. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.777540

- Park, N. K., Jang, W., Thomas, E. L., & Smith, J. (2021). How to organize creative and innovative teams: Creative self-efficacy and innovative team performance. Creativity Research Journal, 33(2), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1842010

- Pelled, L. H., Eisenhardt, K. M., & Xin, K. R. (1999). Exploring the black box: An analysis of work group diversity, conflict and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667029

- Pertuz, V. P., Geizzelez, M. L., Pérez, A., & Vega, A. L. (2020). The relationship between organisational learning and innovation capabilities in medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, 22(2), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBIR.2020.107843

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

- Rhodes, C. (2012). Should leadership talent management in schools also include the management of self-belief? School Leadership & Management, 32(5), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2012.724671

- Richter, A. W., Hirst, G., Van Knippenberg, D., & Baer, M. (2012). Creative self-efficacy and individual creativity in team contexts: Cross-level interactions with team informational resources. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1282–1290.

- Rousseau, D. M., & House, R. J. (1994). Meso organizational behavior: Avoiding three fundamental biases. Journal of Organizational Behavior (1986-1998), 1, 13–30.

- Salazar, M. R., Lant, T. K., Fiore, S. M., & Salas, E. (2012). Facilitating innovation in diverse science teams through integrative capacity. Small Group Research, 43(5), 527–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496412453622

- Sawyer, J. E., Houlette, M. A., & Yeagley, E. L. (2006). Decision performance and diversity structure: Comparing faultlines in convergent, crosscut, and racially homogeneous groups. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.08.006

- Seers, A. (1989). Team-member exchange quality: A new construct for role-making research. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 43(1), 118–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(89)90060-5

- Shin, S. J., Kim, T. Y., Lee, J. Y., & Bian, L. (2012). Cognitive team diversity and individual team member creativity: A cross-level interaction. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0270

- Sinha, J. B. (1984). A model of effective leadership styles in India. International Studies of Management & Organization, 14(2-3), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1984.11656388

- Sinha, J. B. (2014). Psycho-social analysis of the Indian mindset. Springer India.

- Sinha, J. B. P. (1970). Development through behaviour modification (Vol. 5). Allied Publishers.

- Sparrow, P. (2019). A historical analysis of critiques in the talent management debate. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 22(3), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2019.05.001

- Stokes, P., Liu, Y., Smith, S., Leidner, S., Moore, N., & Rowland, C. (2016). Managing talent across advanced and emerging economies: HR issues and challenges in a Sino-German strategic collaboration. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(20), 2310–2338. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1074090

- Straube, J., Meinecke, A. L., Schneider, K., & Kauffeld, S. (2018). Effects of media compensation on team performance: The role of demographic faultlines. Small Group Research, 49(6), 684–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496418796281

- Srikanth, K., Harvey, S., & Peterson, R. (2016). A dynamic perspective on diverse teams: Moving from the dual-process model to a dynamic coordination-based model of diverse team performance. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 453–493. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1120973

- Tansley, C. (2011). What do we mean by the term “talent” in talent management? Industrial and Commercial Training, 43(5), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197851111145853

- Tarique, I., & Schuler, R. S. (2010). Global talent management: Literature review, integrative framework, and suggestions for further research. Journal of World Business, 45(2), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.09.019

- Teagarden, M. B., Von Glinow, M. A., & Mellahi, K. (2018). Contextualizing inter- national business research: Enhancing rigor and relevance. Journal of World Business, 53(3), 303–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.09.001

- Tidd, J., & Thuriaux-Alemán, B. (2016). Innovation management practices: Cross-sectorial adoption, variation, and effectiveness. R&D Management, 46(S3), 1024–1043. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12199

- Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137–1148.

- Times of India. (2015). Teamwork a handicap for most Indian executives. Retrieved September 11, 2018 from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/Teamwork-a-handicap-for-most-Indian-executives-Study/articleshow/48062827.cms

- Tripathi, N., & Ghosh, V. (2020). Deep-level diversity and workgroup creativity: The role of creativity climate. Indian Journal of Business Research, 12(4), 605–624

- Vaiman, V., Collings, D. G., & Scullion, H. (2017). Contextualising talent management. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 4(4), 294–297. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-12-2017-070

- Valverde, M., Scullion, H., & Ryan, G. (2013). Talent management in Spanish medium- sized organisations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(9), 1832–1852. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.777545

- van Knippenberg, D., Kooij-de Bode, H. J., & van Ginkel, W. P. (2010). The interactive effects of mood and trait negative affect in group decision making. Organization Science, 21(3), 731–744. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0461