Abstract

This paper adds a novel perspective to employee voice literature by thematically analysing 36 in-depth interviews of surgeons and anaesthesiologists, who work together but in the context of a blurred hierarchy. We found that these two professions effectively leveraged expertise in speaking up on safety concerns relating to their own speciality, when speaking to each other, irrespective of hierarchy. Further, as interdependent roles make cross speciality voice vital for patient safety, they also spoke up on occasions to negotiate risk and safety concerns across speciality. However, power struggles and protection of speciality authority predisposed each professional group to undervaluing the contribution of the other and often attributing self-interest and opportunistic motives to those speaking up. This led to each group resisting influence making silence a commonplace on cross speciality safety concerns. These contexts present an intriguing environment for voice behaviour which requires research and management attention.

Introduction

A central theme in the literature on employee voice is how power differences as a result of hierarchy undermine psychological safety and efficacy for voice (e.g. Huang et al., Citation2023; Li et al., Citation2023; Morrison et al., Citation2015; Wilkinson et al., Citation2020). Highlighting this, Pfrombeck et al. (Citation2022, p. 2) comment that ‘given that speaking up is impactful in so many different ways, why do employees often hesitate to express their concerns or needs? We propose an answer to this conundrum can be found in a single word: Hierarchy.’ For instance, while having expertise enhances being listened to (Bonaccio & Dalal, Citation2006; Whiting et al., Citation2012), power holders tend to discount advice, including those of experts when this threatens their position (Fast et al., Citation2014; Tost et al., Citation2012). In healthcare, formal power often suppresses expertise and the voice of lower ranks and frontline professionals (Kobayashi et al., Citation2006; Peadon et al., Citation2020). Surgeons having power over other physicians and physicians having power over nurses engender silence on patient safety (Currie et al., Citation2015; Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006; Wilkinson et al., Citation2015). Thus, clear power differentiation within and across professional groups can undermine voice.

We argue that experts in blurred hierarchies characterised by interdependent and dynamic work environments present a unique context to voice. For instance, the authority between surgeons and physician anaesthetists (anaesthesiologists) remains unclear in the context of highly interdependent work (Cooper, Citation2018; Helmreich & Merritt, Citation2019). Although surgeons sometimes claim informal power, the two groups have no formal professional or organisational hierarchy (Bryan & Kolarzyck, Citation2020; Cooper, Citation2018) and are often seen as co-captains (Bryan & Kolarzyck, Citation2020). So, while there is a clear hierarchy within each profession this is not apparent between the professional groups.

Research has shown that dynamic and interdependent work environments mitigate the lack of perspective taking among experts (Atkins et al., Citation2002; Gonzalez, Citation2005; Gonzalez et al., Citation2003). Similarly, cross functional teams that allow dynamic shifts of power based on expertise enhance cooperation and team outcomes (Aime et al., Citation2014; Tarakci et al., Citation2016). Cross-sector problem-solving groups operating without clear power structures can enhance collaboration and voice relative to traditional hierarchies (Daymond & Rooney, Citation2018). This is consistent with the Conflict Theories of Power argument that power balance and equality mitigate power struggles and promote cooperation and team outcomes (e.g. Eisenhardt & Bourgeois, Citation1988; Greer & van Kleef, Citation2010). Following this, we propose that the ability to express voice, contest, and negotiate divergent ideas in a more cooperative and receptive manner might be enhanced among expert groups in a blurred hierarchy.

Alternatively, as the Functional Theories of Power suggest the lack of clear power differentiation generates power struggles and lack of coordination (Halevy et al., Citation2011; Keltner et al., Citation2003; Tiedens & Fragale, Citation2003), a blurred hierarchy might also engender a lack of perspective taking and silence. Cognitive entrenchment and inflexibility in knowledge domain tend to hinder experts from appreciating others viewpoint (Dane, Citation2010; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Although dynamic work environments can mitigate the lack of perspective taking, this is dependent on whether experts focus attention on their own speciality or are open to that of others (Dane, Citation2010; James, Citation1890). As experts resist each other and withhold information in the context of competition (Quiamzade & Mugny, Citation2009; Toma et al., Citation2013), the lack of perspective taking and silence might be reinforced in a blurred hierarchy where power might be contested. As Hirschman’s seminal exit, voice, and loyalty framework shows that voice is a means of people asserting their interests and dissatisfaction (Hirschman, Citation1970), the conceptualisation of voice as prosocial in much of the Organisational Behaviour literature has therefore been criticised as ignoring self-interest voice (e.g. Lin et al., Citation2020; Pfrombeck et al., Citation2022). We therefore argue that potential power struggles among experts might engender self-interest voice and voice targets attributing self-interested motives rather than prosocial motives to those voicing. This study, therefore, aims to explore voice and silence among professional groups working across specialities in a dynamic interdependent environment characterised by a blurred hierarchy. We focus on how experts speak up on their own speciality and across speciality.

We contribute knowledge on the nature of voice and silence among experts in dynamic work environments. Linking power struggles to voice, we also show how the co-existence of prosocial and self-interest motives engender attributions and affect receptivity. Finally, we contribute to conflicting theorisation on power distribution and organisational outcomes (e.g. Greer & van Kleef, Citation2010; Halevy et al., Citation2011).

Theoretical framework and literature review

Theoretical perspectives

The Conflict Theories of Power is rooted in the notion that humans are created equally (Rousseau, Citation2008) making power differences undesirable and illegitimate (Plato, Citation1998). As inequality naturally generates competition and power struggles, equality or power balance is considered to mitigate this and promote cooperation and harmony for better organisational outcomes (Greer et al., Citation2011; Greer et al., Citation2017; Greer & van Kleef, Citation2010). Consistent with this, the extant voice literature has shown that power differences, especially in hierarchies undermine voice (e.g. Morrison, Citation2014; Morrison & Milliken, Citation2000; Pfrombeck et al., Citation2022). Moreover, while the Functional Theories of Power often ascribe competence and knowledge to superiors (e.g. Van Vugt et al., Citation2008), the Conflict Theories of Power favour a more dynamic alignment between power and knowledge based on the notion that superiors are not necessarily the most knowledgeable or competent people (Cheng et al., Citation2013).

With the Functional Theories of Power, clear power differentiation is essential for better functioning of teams and organisations as this enhances clarity, stability and coordination which mitigate competition and power struggles (Halevy et al., Citation2011; Keltner et al., Citation2003; Tiedens & Fragale, Citation2003). This is based on the notion that humans have an unconscious preference for hierarchy (Tiedens & Fragale, Citation2003) and power being a legitimate tool for securing social order, organisational stability and effectiveness (Arendt, Citation1970). Less stable and mutable power contexts therefore engender power struggles and conflicts which harm team and organisational outcomes (Halevy et al., Citation2011; Keltner et al., Citation2003; Tiedens & Fragale, Citation2003). Moreover, the Functional Theories of Power align clear differentiation of competencies and expertise to better team outcomes and assume that superiors are the most knowledgeable and competent (e.g. Van Vugt et al., Citation2008). While the Conflict Theories of Power favour dynamic alignment between power and competencies, it is consistent with the Functional Theories of Power in seeing that differentiation of power based on expertise or competencies can mitigate conflicts and enhance team outcomes (e.g. Greer et al., Citation2017; Tarakci et al., Citation2016). These theories provide potential insight into voice between surgeons and anaesthesiologists, who have differentiated expertise but work in a blurred hierarchy. While this might promote cooperation and voice from the perspective of the Conflict Theories of Power, it might engender power struggles and undermine voice from the perspective of the Functional Theories of Power.

Surgeon-anaesthesiologist power relationship in perspective

Surgeons and physician anaesthetists (anaesthesiologists) are interdependent surgical specialities (Bryan & Kolarzyck, Citation2020; Helmreich & Merritt, Citation2019). Surgeons generally determine surgical needs and plan this with anaesthesiologists (Helmreich & Merritt, Citation2019). Anaesthesiologists key roles include; recording and monitoring vital patient signs; sleep, signs of shock and pain, estimate blood loss and timely progress of surgery (Scarlet & Dreesen, Citation2020).

Both specialities are involved in coordinating patient management, including determining appropriate anaesthesia and prompting each other during surgical procedures of signs that might require action (Henderson, Citation1932). Surgery existed long before anaesthesia; during this era, surgeons were responsible for managing procedures where surgery was painful, highly risky and undertaken only as a last resort (Ahmad & Tariq, Citation2017). The anaesthesia profession began with apprentices who were handpicked by surgeons in an era where surgeons had full control of surgery (Bryan & Kolarzyck, Citation2020). This relationship changed when anaesthesia became an autonomous speciality (Bryan & Kolarzyck, Citation2020) although this history means surgeons sometimes claim to be in charge. Henceforth, although healthcare hierarchy subject nurses, including nurse anaesthetists, to doctors’ authority, the authority between surgeons and anaesthesiologists remains unclear (Helmreich & Merritt, Citation2019).

Power, expertise and voice and silence: focus on blurred hierarchy

Consistent with the undesirable effect of power inequality and imbalance on team and organisational outcomes (Greer et al., Citation2011; Greer et al., Citation2017; Greer & van Kleef, Citation2010), the detrimental effect of power differences in hierarchy on voice has been well-rehearsed (Morrison & Milliken, Citation2000; Morrison et al., Citation2015; Pfrombeck et al., Citation2022). In healthcare, professional hierarchies classify individuals and groups by varying status and power, which hinders upward knowledge sharing and voice (Currie et al., Citation2015; Kobayashi et al., Citation2006; Peadon et al., Citation2020). Research has shown that silence is more likely when there is a clearer power differentiation (Kobayashi et al., Citation2006; Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006; Peadon et al., Citation2020).

On the other hand, the Conflict Theories of Power associate team and organisational benefits with power balance and equality (Greer et al., Citation2011; Greer et al., Citation2017; Greer & van Kleef, Citation2010; Woolley et al., Citation2010). Shared power and leadership is deemed beneficial in contemporary organisations with flatter power structures (Wang et al., Citation2014) and equality in structural power enhances turn-taking in conversation and greater participation in decision-making, which boosts work outcomes (Patel & Cooper, Citation2014; Woolley et al., Citation2010). Relative to entrenched upward silence among doctors (Kobayashi et al., Citation2006; Peadon et al., Citation2020) and doctors’ authority undermining nurses’ voice even in core nursing practices (Malloy et al., Citation2009; Reed, Citation2016), differentiated expertise in a blurred hierarchy might promote voice. As surgeons and anaesthesiologists formally share a parallel group hierarchy, each might speak up on their own speciality to senior ranks across speciality. Beyond the tendencies of such voice being valued based on expertise, this context might strengthen experts’ authority in enabling effective and constructive negotiation of different perspectives towards better work outcomes, such as patient safety.

Moreover, we know that the lack of perspective taking among experts is mitigated in dynamic work environments (Atkins et al., Citation2002; Gonzalez, Citation2005; Gonzalez et al., Citation2003), such as firefighting (Klein, Citation2017). As experts adapt (Gonzalez et al., Citation2003) and question their own expertise in dynamic work environments (Farjoun, Citation2010), this can allow other voices to be heard. While acknowledging that knowledge and competence ascription to superiors in hierarchy (e.g. Van Vugt et al., Citation2008) tend to hinder legitimacy for upward knowledge sharing and voice (Currie et al., Citation2015; Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006), we propose that this might be different among experts in a blurred hierarchy. As the Conflict Theories of Power propose that power balance and equality decreases positional threat to power and enhance cooperation (Eisenhardt & Bourgeois, Citation1988; Greer et al., Citation2011; Greer & van Kleef, Citation2010), the willingness to utilise other’s expertise towards collective goals (Deutsch et al., Citation2011) might be enhanced in such context. The standard cognitive entrenchment, and inflexibility in one’s knowledge domain, which prevents experts from taking perspectives and incorporating ideas from others (Dane, Citation2010; Zhang et al., Citation2022) might therefore be mitigated to enhance voice.

However, based on the Functional Theories of Power argument that mutable and lack of clear power differentiations engender power struggles and lack of coordination (e.g. Halevy et al., Citation2011; Tiedens & Fragale, Citation2003), a sense of competition in the context of blurred hierarchy might hinder cooperation and voice. There is evidence of voice withholding in the context of power struggles (e.g. Maner & Mead, Citation2010) and experts often fail to take other perspectives and withhold information in the context of competition (Quiamzade & Mugny, Citation2009; Toma et al., Citation2013). As perspective taking is hindered when attention is focused on one’s own expertise (Dane, Citation2010; Hargadon, Citation2006; James, Citation1890), this can reinforce the lack of perspective taking among experts (Dane, Citation2010; Zhang et al., Citation2022) and discourage voice across speciality.

Similarly, competing professional values can trigger competition and incline experts to focus on their own speciality. As surgeons are proactive in addressing patients’ immediate problems while anaesthesiologists take a more precautionary approach (e.g. Cooper, Citation2018), each group might focus on issues from their own specialities thereby undermining cooperation. Henceforth, while experts may speak up in their own specialities, lack of perspective taking might hinder voice and listening to voice by others across specialities quite apart from hierarchy. As high status medical professionals are not motivated to share knowledge with peers outside their specialities (Currie et al., Citation2015), colleagues may choose silence towards same ranks across speciality safety. Further, experts may not feel obliged to take helpful suggestions or instruction from senior colleagues across speciality. In such context, we propose that typical upward silence such as that of residents towards specialists and consultants (Kobayashi et al., Citation2006; Peadon et al., Citation2020) might be accentuated across specialities.

Moreover, as power struggles are often represented as being about ensuring desirable decisions (De Wit et al., Citation2012; Greer et al., Citation2011), active voice within speciality can easily be disguised or perceived by targets as self-interested and a threat rather than an opportunity for improvement. The central role of perceived legitimacy of expertise and competencies in accepting influence in dynamic teams (Aime et al., Citation2014; Tarakci et al., Citation2016) might therefore be eroded in this context. As noted earlier the conceptualisation of voice as prosocial in much management literature such as organisational behaviour has been criticised as limiting (Pfrombeck et al., Citation2022). For instance, self-interest voice may be framed as prosocial (Rucker et al., Citation2018) and power holders’ inclination to protect their power can lead them to attribute self-interest motives to others (Maner & Mead, Citation2010; Urbach & Fay, Citation2018). Hence, while managers value prosocial voice and resist egoistic voice (Urbach & Fay, Citation2018; Whiting et al., Citation2012), these are not easily disentangled. Perceiving voice as self-interested, especially in the context of scarce resources and power insecurity can activate sensitivity to threat and undermine receptivity (Pfrombeck et al., Citation2022; Urbach & Fay, Citation2018).

Overall, we propose that experts operating in a dynamic work environment with blurred hierarchy present a unique context for voice. As little is known about the topic, we adopt an inductive qualitative approach to better understand the phenomenon.

Methods

Research context

This study is conducted in surgical departments in two teaching hospitals in a West African country (anonymised as Hospitals HA and HB). These departments have between 4 to 10 specialised units. The hospitals have separate departments for surgery (headed by a surgeon) and anaesthesia (headed by anaesthesiologists). This unclear power structure reflects the wider surgeon-anaesthesiologist relationship in most healthcare contexts around the world (Cooper, Citation2018; Helmreich & Merritt, Citation2019).

Research design and data collection

From a social constructivist philosophical perspective (Saldana, Citation2011), this study adopted an inductive qualitative approach using semi-structured interviews to explore the complex social phenomenon (Denzin, Citation2008) surrounding power and voice. Purposive sampling was adopted to ensure the inclusion of diverse ranks (consultants, specialists, and residents) across surgical teams. Overall, thirty-six (36) participants were sampled from 2 hospitals based on hospital size (HA − 22, Hospital HB −14). As surgeons outnumber anaesthesiologists by more than two-thirds, 24 surgeons and 12 anaesthesiologists were sampled. Across the two hospitals, the sample comprised 10 consultants, 13 specialists, and 13 residents. Details on participants is presented in .

Table 1. Interview participants.

Interviews were conducted in two phases; the first phase was a face-to-face interview, which was a part of a larger study. Following an indication of insufficient data on the subject of this paper, a second phase of Zoom interviews was conducted. After a total of 36 interviews, no new insight was generated from additional interviews indicating data saturation (Sandelowski, Citation2000). All interviews were conducted in English and lasted between 40 to 70 min. Participants’ consent was obtained for the interviews and recordings. Interview questions were adapted from Schwappach and Gehring (Citation2014). Key questions asked include - How comfortable are you expressing voice on patient safety concerns to colleagues and superiors? Are there specific instances where you were concerned about patient safety and were able to speak up or unable to speak up on these? Interview questions were slighly modified (Spradley, Citation1979) to address emerging issues, including exploring specific instances of voice and silence to understand the circumstances and conditions surrounding these. This allowed participants to relate to and share their socially constructed experiences in their daily work. Thick descriptions of professional and organisational context (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) in relation to responses aided appropriate interpretation of the data.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, read and reflected upon to enhance data familiarity, generate discoveries and insight into events in a chronological storyline (Langley, Citation1999), such as those relating to power struggles, the lack of a clear hierarchy and speciality knowledge in relation to voice and silence. Interview transcripts were then uploaded into NVivo 12, where the first author did an open coding by breaking down direct words of participants into common issues, ideas and events. Next, interrelations among each set of categories were closely examined through an inductive and iterative approach in a series of back-and-forth movements between the data and literature to revise categories and patterns (e.g. Ritchie et al., Citation2014) to generate second-order and third-order codes (themes). Although the extant literature provided a general guiding framework to analysis, themes were inductively generated from the data. The second author checked for accuracy and consistency by independently coding 10 random interview transcripts. Minor differences were discussed and resolved. Themes are supported with slightly edited quotes for the flow of language and anonymised with professional labels.

Two participants from the interview (one surgeon and one anaesthesiologist read the findings and in addition 3 others (a surgeon and 2 anaesthesiologists) who were not involved in the research also read and commented on it as a reflection of their experience. The ethics committees of the study hospitals approved the research.

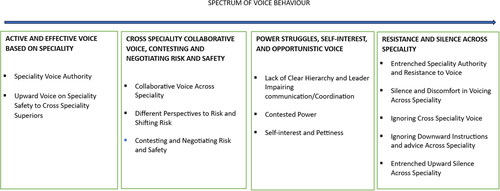

Findings

The four themes are - Active and Effective Voice based on Speciality; Cross Speciality Collaborative Voice, Contesting and Negotiating Safety and Risk; Power Struggles, Self-Interest, and Opportunistic Voice; Resistance and Silence Across Speciality. As illustrated in a thematic map in below, the findings span a spectrum from active voice within speciality to resistance to voice and silence across speciality.

Active and effective voice based on speciality

Responses show that surgeons and anaesthesiologists are prepared to use challenging voice relating to patient safety concerns from the perspective of their own speciality to the other profession. Surgeons decide which patients require surgery and which procedures to use and are vocal on surgical needs. Surgeons also generally determine what is an emergency although anaesthesiologists may contest this. Residents and specialist surgeons are often prepared to justify surgical needs even when consultant anaesthesiologists disagree. It was reported that a specialist anaesthesiologist tried to stop a senior resident surgeon from supervising a more junior doctor in undertaking laparoscopic appendicectomy outside normal operating hours at midnight. However, the surgeon resisted and prevailed on the grounds that the procedure was a surgical emergency.

On surgical issues that is my field as a surgeon, I am not restrained from speaking up. (Specialist-2-Surgeon-HA)

While surgeons put patients on a surgical list, anaesthesiologists review patients’ overall fitness and the availability of essential resources for procedures. On this issue, anaesthesiologists do speak up. The participants noted that although there is often consensus on the need for surgery, unavailability of resources and patients not being medically fit, sometimes lead to anaesthesiologists requesting delays to procedures. While this is not an issue in cases where both professions see it as an emergency it can be a source of friction in elective cases and when anaesthesiologists perceive that non-emergencies are presented by surgeons as emergencies. While surgeons are inclined to dominate decision-making (Little, Citation2002; Oborn & Dawson, Citation2010), it was reported that anaesthesiologists’ strongly challenge any attempts by surgeons to circumvent and skip safety protocols. Anaesthesiologists insist on their protocols for patient preparations and the availability of what they regard as essential resources, such as blood and intensive care facilities.

Sometimes we look way ahead, anticipate problems before they arise. And we say because of this let’s take this and that precaution, such as holding on procedures. This brings about a lot of conflict with surgeons (Consultant-10-Anaesthesiologist-HA)

The anaesthesiologists are the policemen. In most cases because of the power that they have, they dictate a lot. So, if you have a planned surgery and the anaesthesiologist thinks it is a bad case, in the end, it is the anaesthesiologist who decides whether to put the patient to sleep or not. (Resident-2-Surgeon-HB)

Similar issues also occur during surgical procedures. A consultant anaesthesiologist described an impasse with two professor surgeons during a severe bleeding case where an unborn baby was prematurely separated from the placenta. As reported, the bleeding had got to a point where blood clot factors were depleted, and bleeding was difficult to control. He notes that although a safe practice is to give such patients a ‘clotting factor’ to enhance blood clots, the surgeons instructed him to anaesthetise the patient for further procedures, which he refused to do.

So, I said NO, until they ensure the blood will clot, I am not going to anaesthetise the patient. So, I delayed them knowing that if this is not done, they will cut the patient to continue bleeding in the ward and they will say they have finished their work. They finally brought some of the clotting factors and we had a successful surgery. (Consultant-3-Anaesthesiologist-HA)

Surgeons generally find working with nurse anaesthetists easier.

Even though physician anaesthesiologists may be more skilled, it is easier to work with and communicate with nurse anaesthetists as there is that sense of seeing you as the superior. (Specialist-12-Surgeon-HB)

Hey! It is very easy for us to express concerns to surgeons – we can stop them unlike nurse anaesthetists who could be bullied. (Consultant-8-Anaesthesiologist-HB)

In addition, anaesthesiologists directly challenged senior surgeons or used senior anaesthesiologist colleagues to provide support for their voice against surgeons.

It is easier for me to speak up to consultants in another speciality insisting that this is best for patient safety. Because I would have definitely discussed the issue with my own superior, who will back me. (Resident-8-Anaesthesiologist-HB)

A Resident Anaesthesiologist described how a consultant surgeon classified what they regarded as a non-emergency case as an emergency and ignored a ‘Doppler ultrasound’ test which the anaesthesiologist thought was imperative for a Deep vein Thrombosis (DVT) patient. The Resident quickly located the senior anaesthesiologists who intervened to cancel the procedure and demanded the test be done. The sense of equality as professional groups aids speaking up based on expertise. Surgeons confirm.

If you push them (anaesthesiologists) to do certain things they report to their bosses, who always support them. (Specialist-10-Surgeon-HA)

Cross speciality collaborative voice, contesting and negotiating safety and risk

The dynamic and interdependent nature of surgery gives rise to routine cross speciality communication such as prompting each other on safety indicators. Although anaesthesiologists decide anaesthesia needs, surgeons also are involved. For example, if a procedure is straightforward, surgeons may propose a regional rather than general anaesthesia. Surgeons also ask for adjustments in anaesthesia based on surgical needs and request this depending on patient responses. Anaesthesiologists also report worrying patient vitals to surgeons, such as bleeding and may ask that this be addressed. They may also request additional blood or demand procedures to be shortened or concluded due to safety reasons. Our findings show that surgeons engage anaesthesiologists on core anaesthesia issues to a large degree as most surgical practices are directly dependent on anaesthesia. However, anaesthesiologists rarely intervene on core surgical issues unless these have severe implications for safety.

If the anaesthesiologist observes that the patient has lost a certain amount of blood, he will prompt the surgeon –your patient has lost so and so amount of blood in such a time. So, find the source or work faster. (Specialist-6-Surgeon-HA)

In my observation, surgeons are fairly comfortable in giving suggestions on the mode of anaesthesia. (Resident-9-Anaesthesiologist-HB)

In my experience we [Anaesthesiologists] do not go into the surgical issues as to what they are doing or cutting surgically, incision or those. (Specialist-4-Anaesthesiologist-HA)

Meanwhile, consistent with differing professional values participants indicate that the hallmark and core value of safety in anaesthesia often conflict with surgeons’ proactiveness in addressing patients’ immediate problems. Anaesthesiologists describe their work as highly delicate, where there is only a small margin of error. This informs a precautionary approach, which can lead to clashes with surgeons.

We are trained to be very circumspect. But the surgical side is a bit more outgoing. By their training, they are given more room to do a bit more. So sometimes I will be here and see less experienced surgeons doing or trying to do a case that is above them. (Consultant-3-Anaesthesiologist-HA)

Most surgeons have the desire to quickly resolve whatever problem the patient has through surgery. Usually, anaesthetists are those who want to err on the side of caution. (Resident-12-Surgeon-HB)

Anaesthesiologists note that sometimes while patients’ physiology and the lack of essential resources, such as blood and intensive care facilities, indicate to them that immediate surgery is unsafe, surgeons sometimes contest this. Consistent with how resource constraints motivate compromises on ideal care practices in Low-Middle-Income-Countries (LMIC) (e.g. Mawuena & Mannion, Citation2022), it was reported that surgeons justify the risks to undertaking procedures when intensive care space and facilities are not available by highlighting the risks of patients’ condition deteriorating without immediate surgery. This can displace risks to anaesthesia. For instance, as anaesthesiologists support patients’ recovery including in intensive care after procedures, what surgeons might consider non-essential may be considered vital in anaesthesia.

They (anaesthesiologists) can sometimes be very inconsiderate. Why am I saying this? Because, if the patient is rushed in as emergency, they don’t check all those things, but we often have successful surgeries. But under elective cases they become too petty. (Specialist-13-Surgeon-HB)

I have heard surgeons say we anaesthesiologists pamper patients and that they will be fine anyway without intensive care facilities such as ventilators and anaesthesia support after surgery. (Senior-Resident-12-Anaesthesiologist-HA)

As resource constraints make best practices hard to implement amidst differing perspectives to risk, this leads to dialogue regarding patient safety. For instance, based on patients’ conditions, and expected blood losses, anaesthesiologists may refuse to start some procedures. At other times, if it is considered that patients may not require intensive care or are not likely to lose much blood, anaesthesiologists may agree to start procedures and administer drugs to manage bleeding while arrangements for additional blood are being made.

Depending on the case; there are some surgeries that you cannot afford to start without blood. There are others that anaesthesia can give medication to manage the blood loss while you wait for the blood. (Specialist-9-Anaesthesiologists-HB)

While procedures can be unpredictable, anaesthesiologists say that surgeons often tell them what they think they want to hear such as the procedure is very straightforward so they can proceed with their cases. But in practice, these claims do not always materialise and there was a chilling account given of team members running around in search of blood in the middle of a procedure to keep a patient alive. Again, anaesthesiologists note that while some surgeons are fast and can manage precarious situations this is not true for all surgeons. So, judgements of past experiences are important in negotiations where experienced and trusted surgeons are given better chances to navigate risk.

So, my boss will ask me who is the surgeon doing the case? I mention, he says – NO, we need the blood before we start. But other times, you mention another surgeon’s name and he say this guy is fast or has done it a number of times, so we can start while arrangements for blood are being made. (Resident-8-Anaesthesiologists-HB)

If I have just qualified as a surgeon, an experienced anaesthesiologist will not give me the same chance as he will give my boss who has many years of experience. You are new and may not be able to manage the situation as your boss who has seen it all and done it all. (Resident-13-Surgeon-HA)

Power struggles, self-interest, and opportunistic voice

It further emerged that patient care is infused with power struggles, which influences voice. Although there is hierarchy within both specialities, participants agree that there is no clear organisational or professional hierarchy between surgeons and anaesthesiologists. Sharing a parallel group hierarchy, they describe themselves as equals. This is common in large medical facilities compared to small facilities where nurse anaesthetists are hierarchically classified under surgeons.

There is always almost a power undertone. In some institutions anaesthesia is part of surgery but in big institutions like this, anaesthesia is a department on their own. So, surgery is a department on its own with its own hierarchy and anaesthesia is a department on its own with its own hierarchy. So, we are two parallel departments working together. (Specialist-2-Surgeon-HA)

Consistent with this, participants indicated that they did not see a clear hierarchy between the two specialities. While anaesthesiologists’ taking charge is evident during patient preparations, this switches to surgeons once patients are anaesthetised in the theatre. However, it becomes tricky as to who is in charge and directs communication when a consultant surgeon and consultant anaesthesiologist are both in the theatre. This issue becomes more sensitive when highly ranked and relatively low ranked colleagues work together, such as a consultant anaesthesiologist and a specialist or resident surgeon.

In my experience, there are trivial issues, who is superior in theatre? That is the battle, who is the big man in theatre, is it the anaesthesiologist, is it the surgeon? As far as this is not settled in a team sometimes communication even doesn’t take place at all. (Specialists-9-(Anaesthesiologist-HB)

In the operating room, everyone feels he is the boss. The anaesthesiologist feels he is the boss, and you cannot dictate to him in his field - you cannot push them around. A lot of our bosses they pull ranks. (Resident-13-Surgeon-HA)

Meanwhile, surgeons were often perceived as appropriating informal power as ‘the boss’ and attempt to unduly control patient decision-making. Surgeons see their work of cutting into the body to get rid of problems as the fundamental role of surgery thereby perceiving anaesthesiologists as helpers. Consistent with surgeons’ perceived dominating behaviour (Little, Citation2002; Oborn & Dawson, Citation2010), they are said to exercise authority including attempting to control anaesthesia and making decisions on safety protocols. Again, many surgeons are used to working with nurse anaesthetists, who they are used to instructing but this is much harder if working with anaesthesiologists.

Well, surgery involves a lot…cutting and pulling in solving patients’ problems. Even though the anaesthesiologist has power, this cannot solve patients’ problems but just to ensure safety and manage pain. (Specialist-12-Surgeon-HB)

Surgeons have a mindset that anaesthesiologists are their ‘children’ and must be under them. So, they instruct you to put the patient to sleep for them to have their way. So, we always fight. (Consultant-3- Anaesthesiologists-HA)

Surgeons by their training and in other hospitals, act as bosses and they command everybody as they wish. So, when they move to a bigger facility and meets an anaesthesiologist who start questioning some of their practices, then they say – look! I am the surgeon you cannot question me! (Consultant-10-Anaesthesiologist-HA)

At the same time, surgeons can perceive anaesthesiologists’ actions and voice as about leveraging self-interested opportunities. It is alleged that anaesthesiologists who are not happy with surgeons’ informal lead role or perceived ‘bossy’ posture exercise voice by exaggerating patients’ safety requirements and resource constraints as impediments. One surgeon describes how anaesthesiologists delayed a procedure based on infection concerns as the water was not flowing but went ahead to cancel it even after the water supply was restored.

Ego comes in. Your colleague is a specialist whose input you cannot do without. So, because you assume you are the leader, he can use his power against you. When it comes to surgery, there will be a thousand and one reasons why you cannot do it. (Consultant-4-Surgeon-HA)

Often, we understand anaesthesiologists concerns because we surgeons are not daft, we have done some physiology and know basic safety. But there is a point where everything is in the interest of patients, and we work together but there is a point where anaesthesiologists are being ridiculous. (Specialist-1-Surgeon-HA)

Anaesthesiologists’ own self reflecting comments suggest that this cannot be discounted:

Anaesthesiologists can be petty when maybe they have overworked, tired and finding flimsy excuses to postpone a case or if they have a feud with a surgeon. (Senior-Resident-12-Anaesthesiologist-HA)

Meanwhile looking at the overall responses, it is clear that some perceived pettiness, self-interest, and opportunistic voice are essentially part of negotiating safety and risk barriers. This is evident in an account about a surgeon who wanted to perform appendicectomy for a patient with throat cancer at night. The anaesthesiologist checked the airways for obvious obstructions, but needed an imaging device to verify this, which was not available. Given night surgery was limited to emergencies and the patient was stable, the anaesthesiologist requested the procedure be postponed to the next day so that the team could have full support in the event of any complications. The surgeon resisted this, forcing the team to agree to use a spinal anaesthesia to mitigate potential risk. However, upon examining a previous full-blood count result of the patient, the anaesthesiologists deemed this to be too low and demanded a new test thereby postponing the operation. The interviewee commented that although the initial blood test result was not ideal, the real reason for demanding a new test was to push the case to the next day. According to the interviewee, the displeased surgeon obtained a new and acceptable test result later that night forcing the procedure to go ahead. So, while there may be a self-interest component to this, it is also about tactics to prevent a surgeon from doing what they regarded as an unsafe procedure. However, as a self-interest agenda can also be disguised as a prosocial behaviour, especially in the context of power struggle (De Wit et al., Citation2012; Greer et al., Citation2011) targets may perceive such voice as self-interested and opportunistic thereby undermining receptivity.

Resistance and silence across speciality

Cross speciality collaborations are often hindered as participants note that it is generally difficult and uncomfortable to make suggestions to those who are experts in their own fields and who can show scant interest in outside ideas. Reflective of medical socialisation (Freidson, Citation1988), each speciality perceives the other as having little to contribute to their speciality. This becomes more challenging when safety concerns are embedded within each speciality. It creates unique challenge for speaking up as surgeons and anaesthesiologists consider themselves equals.

If it comes to anaesthesia, it is a different ‘ball game’ altogether because that is a different speciality, and they look at others as knowing nothing about what they do. And it is a problem in medicine. (Resident-3-Surgeon-HA)

It is a big issue, voice across fields that are not necessarily the surgeons’ field – you can ask but you may not have the courage to speak or ask. (Consultant-1-Surgeon-HA)

The feeling of I am the expert, I know what I want to do is there and it a stumbling block to saying certain things or accepting suggestions. (Specialist-7-Anaesthesiologist-HB)

While some level of cross speciality voice takes place toward lower ranks and among same rank superiors, this is described as uncomfortable. A consultant surgeon-1-HA echoes:

I have had very senior colleagues in my rank across speciality doing some things that are not safe and I am stuck. I immediately see where the problem is, but it has not occurred to the person. So, I ask what are you doing? look at that place again. The minute he identifies it, I am out of there. I am not going to offer any more suggestion.

I have observed something with my bosses, they try to say it nicely but not putting it upfront as if teaching the surgeon. (Resident-8-Anaesthesiologist-HB)

He was shouting and I said no. I called his boss and put the phone to his ear – talk to your boss. And the boss told him not to touch the placenta. I was able to do that because we were at the same level. (Specialist-3-Anaesthesiologists-HA)

We also found that experts easily ignore input from non-expert senior ranks. Participants note that by virtue of experience, superiors, especially consultants are positioned to offer helpful advice across speciality under difficult circumstances. However, speciality authority and ego often prevent accepting such advice. Sometimes, subordinates might be unwilling to adjust plans discussed with their own superiors although this might be in the interest of safety. It was reported that a specialist surgeon who was struggling with laparoscopic (a procedure using imaging) declined a consultant anaesthesiologist’s suggestion to open up the patient. The observer noted that while the consultant’s advice was based on how challenging laparoscopic can be for less experienced surgeons, this was not heeded leading to an unsuccessful procedure and complications necessitating a second corrective procedure. While some participants linked ignoring advice to personality, the observer felt the surgeon would have accepted this advice from a consultant surgeon. While acknowledging the usefulness of non-experts’ advice, experts do not feel obliged to accept these.

Advice by consultant anaesthesiologists may be helpful to a resident surgeon. But even then, the resident surgeon will not feel the consultant is in a position to give him a lecture or tell him what to do. (Resident-12-Surgeon-HB)

Downwards from maybe a consultant to a specialist is quite easier but it is easily ignored. (Specialist-2-Surgeon-HA)

Within speciality it is easy to correct subordinates. But this can be difficult across speciality. (Specialist-3-Anaesthesiologists-HA)

Participants note that speaking up across speciality is daring, and extremely difficult as expert superiors rarely take input from subordinates. They note that communication is structured and takes place at the level of equivalent ranks such as specialist to specialist and consultant to consultant. Subordinates, especially residents were clear that they do not cut cross these lines to make suggestions to consultants and specialists. Cross speciality observations are normally relayed to respective speciality superiors to possibly engage similar rank colleagues. Although subordinates may not have the requisite knowledge for voice across speciality, speciality authority reinforces hierarchical power barring such upward voice.

If a safety issue has to do with someone senior across speciality you just keep quiet and watch and hope nothing bad [harm] happens. (Resident-9-Anaesthesiologist-HB)

If you are a Resident Surgeon, you are even ‘a nobody’ to talk to a superior Anaesthesiologist in the first place. If you do, you either get a shouting or a talking down to. So, you just keep quiet. (Senior-Resident-4-Surgeon-HB)

I hardly see any junior colleague making surgical intervention when you are not done reading anaesthesia. (Resident-5-Anaesthesiologists-HA)

Discussion and theoretical implications

Research highlighting the detrimental effect of power differences in hierarchy on voice (e.g. Milliken et al., Citation2003; Morrison et al., Citation2015; Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006; Pfrombeck et al., Citation2022) and expertise (Fast et al., Citation2014; Tost et al., Citation2012) has given little attention to voice among experts in a dynamic work environment and where there is no clear hierarchy.

Exploring the subject in the context of the surgeon-anaesthesiologist relationship, we found support for both the Functional Theories of Power and Conflict Theories of Power. In support of the Conflict Theories of Power, we found that a blurred hierarchy enables experts to effectively leverage expertise in challenging perceived harmful practices in their respective specialities. Contrary to commonplace silence in the medical hierarchy, including doctors’ control of core nursing practices (e.g. Kobayashi et al., Citation2006; Malloy et al., Citation2009; Peadon et al., Citation2020; Reed, Citation2016) surgeons and anaesthesiologists, including their subordinates leveraged expertise to speak up on their speciality safety concerns to senior ranks across specialities. This curtailed surgeons’ inclination to take unilateral decisions. As surgeons are more inclined to risk-taking while anaesthesiologists are precautionary, safety and risk are actively contested and negotiated through voice. Similarly, while silence on unsafe care is often legitimised in the context of resource constraints (e.g. Mawuena & Mannion, Citation2022), this was actively negotiated by both specialities through speaking up for patient care.

However, in support of the Functional Theories of Power (Halevy et al., Citation2011; Keltner et al., Citation2003; Tiedens & Fragale, Citation2003), we found that expertise in blurred hierarchies also generates power struggles which undermine cooperation and valuing experts’ inputs. Each speciality attributes to the other self-interest motives where rivalries are leveraged as opportunities for voice that are not always in patients’ and the teams’ interests. Relative to opportunistic silence (Knoll & Van Dick, Citation2013), we describe this as opportunistic voice. High power distance values in Africa (Hofstede et al., Citation2010) might reinforce power and status conflicts. However, this finding generally contradicts the theorisation by the Conflict Theories of Power that highlight equality and power balance as good for work outcomes (Greer et al., Citation2011; Greer & van Kleef, Citation2010). It further questions similar research that says dynamic work environments enable experts to develop cooperation and positive synergy (e.g. Aime et al., Citation2014; Gonzalez, Citation2005; Klein, Citation2017; Tarakci et al., Citation2016).

Providing insight on recent questioning of the conceptualisation of employee voice as prosocial (Lin et al., Citation2020; Pfrombeck et al., Citation2022; Urbach & Fay, Citation2018), we show that self-interest and prosocial voice might co-exist, especially in blurred and contested hierarchies. As power struggles are often disguised and portrayed as desirable actions (e.g. De Wit et al., Citation2012; Greer et al., Citation2011), voicers in such context may disguise self-interest or opportunistic voice as prosocial. Likewise, targets may misconstrue prosocial voice as self-interested, opportunistic, or even a threat thereby hindering receptivity. For instance, we found that although perceived self-interest and opportunistic voices are sometimes intrinsically part of negotiating risk, perceived self-interest motives often restricted receptivity. As healthcare professionals who are primarily considered to speak up for patients may yet engage in self-interest and opportunistic voice, the real motives for employee voice may not be easily disentangled. We therefore prompt a cautious interpretation of prosocial voice. Similarly, as scarcity of resources tends to incline targets to perceiving voice as a threat rather than an opportunity (Pfrombeck et al., Citation2022), anaesthesiologists who voiced for patient safety based on what surgeons saw as an idealised Western medical textbook rather than taking into account the LMIC context faced push back.

Finally, as voice across speciality is often resisted, same ranked superiors are often silent on safety concerns outside their specialities and experts easily ignored helpful voice from superior ranks across speciality. We show that silence can be problematic among senior ranks across specialities. This reinforced the prevalent upward silence in the medical hierarchy (Kobayashi et al., Citation2006; Peadon et al., Citation2020) where it is very difficult to exercise upward voice across speciality.

Practical implications

Firstly, as power can be functional to experts’ voice, we highlight the need to empower multidisciplinary healthcare professionals, such as nurses, to restrain commonplace abuse of power in hierarchy. Secondly, to manage perceived self-interest and inflexibility, we recommend reflective training (Klein, Citation2003; Klein, Citation2017) to promote constructive voice, mitigate cognitive entrenchment and overconfidence towards receptivity. Thirdly, as broadening attention to other expertise enhances perspective taking (Dane, Citation2010), developing cross speciality knowledge through training can enhance cooperation and voice. Fourth, stakeholders in LMICs should do more to mitigate resource constraints as this reinforces conflict and erodes trust for receptivity to voice. Fifth, improving shared leadership through more joint surgeon-anaesthesiologist patients’ assessments, establishing cross-speciality consensus and protocols on key conditions under which surgery can take place or not can promote transparency, constructive dialogue, and cooperation. Lastly, the detrimental role of hierarchy and the double-edged effect of blurred hierarchy on voice prompts re-thinking interdisciplinary structures in sensitive interdependent settings. Through transdisciplinary imaginations where work is designed beyond disciplines (Brown et al., Citation2010) surgery could consider creating transdisciplinary teams to blur disciplinary barriers which can enhance cooperation and voice.

Limitations and directions for future research

Firstly, interviews are subject to potential recollection biases. And as the subject is about voice and participation was voluntary, the willingness to participate and responses could also be influenced by the same issues we identified in the paper around self-interest and power struggles could influence accounts given. If ethical requirements permit, future studies could use video tapped recordings to add observation data to strengthen this. Secondly, while rich broader professional and organisational context strengthens contribution to theory, based on the study’s High Power-Distance and resource constraints context, we recommend a cautious interpretation of the findings in other contexts. As this study questions popular theorisation that perceives power differences in hierarchy as a source of silence, we call for more scholarly work on subtle power dynamics to enrich theory on power and voice. Research can examine nuanced forms of voice and silence across organisational units and teams with no clear hierarchy to advance knowledge on the drivers of prosocial and self-interest voice behaviour. Top executives who have power and are subject to power struggles (e.g. Greer et al., Citation2017) could be a viable group for such research. Again, as disentangling real motives for employee voice may be highly complex, this highlights recent calls (Wilkinson et al., Citation2020) to integrate employee voice across management disciplines. This has prospects of enriching knowledge and understanding of employee voice. Lastly, as the surgeon-anaesthesiologist’s power relation affects nurses’ teamwork (Cooper, Citation2018), how such power contexts influence broader teamwork and voice, such as among wider surgical teams can be explored.

Conclusion

We demonstrate how voice is enacted among expert groups in a blurred hierarchy where voice and silence co-exist in the context of power struggles and attributions of self-interest motives. While experts effectively speak up on their speciality and to an extent contest and negotiate patient safety through voice across speciality, power struggles and speciality authority generally resisted the influence of outsiders leading to silence across speciality. While power differences can be a trigger for silence, we call for research on how subtle power dynamics shape voice behaviour.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all participants for sharing their personal experiences on the topic. Thanks to our Anonymous Reviewers and the Guest Editor for their very constructive feedback to improve the paper. Thanks to Dr Katherine Gardiner, Miss Rita Mawusi Kwadzo and Dr David Wren for proofreading the paper. The first author (Emmanuel K. Mawuena) wishes to thank his PhD supervisors (Dr Jean Kellie and Dr Nicholas Snowden) for their contributions to his development as a researcher.

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Ethical requirement does not permit open sharing of data based on the sensitive and confidential nature of information involved.

References

- Ahmad, M., & Tariq, R. (2017). History and evolution of anesthesia education in United States. Journal of Anesthesia & Clinical Research, 08(06), 2. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6148.1000734

- Aime, F., Humphrey, S., DeRue, D. S., & Paul, J. B. (2014). The riddle of heterarchy: Power transitions in cross-functional teams. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 327–352. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0756

- Arendt, H. (1970). On violence. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Atkins, P. W., Wood, R. E., & Rutgers, P. J. (2002). The effects of feedback format on dynamic decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 88(2), 587–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00002-X

- Bonaccio, S., & Dalal, R. S. (2006). Advice taking and decision-making: An integrative literature review, and implications for the organizational sciences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(2), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.07.001

- Brown, V. A., Harris, J. A., & Russell, J. Y. (2010). Tackling wicked problems through the transdisciplinary imagination. Earthscan.

- Bryan, Y. F., & Kolarzyck, L. (2020). From ship captains to crew members in a history of relationships between anesthesiologists and surgeons. AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(4), 333–339.

- Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 103–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030398

- Cooper, J. B. (2018). Critical role of the surgeon–anesthesiologist relationship for patient safety. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 227(3), 382–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.006

- Currie, G., Burgess, N., & Hayton, J. C. (2015). HR practices and knowledge brokering by hybrid middle managers in hospital settings: The influence of professional hierarchy. Human Resource Management, 54(5), 793–812. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21709

- Dane, E. (2010). Reconsidering the trade-off between expertise and flexibility: A cognitive entrenchment perspective. Academy of Management Review, 35(4), 579–603. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2010.53502832

- Daymond, J., & Rooney, D. (2018). Voice in a supra-organisational and shared-power world: Challenges for voice in cross-sector collaboration. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(5), 772–804. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1244107

- De Wit, F. R., Greer, L. L., & Jehn, K. A. (2012). The paradox of intragroup conflict: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 360–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024844

- Denzin, N. K. (2008). Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. (Vol. 3). Sage.

- Deutsch, M., Coleman, P. T., & Marcus, E. C. (Eds.) (2011). The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice. (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Bourgeois, L. J. (1988). Politics of strategic decision making in high-velocity environments: Toward a midrange theory. Academy of Management Journal, 31(4), 737–770. https://doi.org/10.2307/256337

- Farjoun, M. (2010). Beyond dualism: Stability and change as a duality. Academy of Management Review, 35(2), 202–225. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2010.48463331

- Fast, N. J., Burris, E. R., & Bartel, C. A. (2014). Managing to stay in the dark: Managerial self-efficacy, ego defensiveness, and the aversion to employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 57(4), 1013–1034. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0393

- Freidson, E. (1988). Profession of medicine: A study of the sociology of applied knowledge. University of Chicago Press.

- Gonzalez, C. (2005). Decision support for real-time, dynamic decision-making tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 96(2), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.11.002

- Gonzalez, C., Lerch, J. F., & Lebiere, C. (2003). Instance-based learning in dynamic decision making. Cognitive Science, 27(4), 591–635. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog2704_2

- Greer, L. L., Caruso, H. M., & Jehn, K. A. (2011). The bigger they are, the harder they fall: Linking team power, team conflict, and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116(1), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.03.005

- Greer, L. L., Van Bunderen, L., & Yu, S. (2017). The dysfunctions of power in teams: A review and emergent conflict perspective. Research in Organizational Behavior, 37, 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2017.10.005

- Greer, L. L., & van Kleef, G. A. (2010). Equality versus differentiation: The effects of power dispersion on group interaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(6), 1032–1044. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020373

- Halevy, N., Chou, Y., & Galinsky, D. (2011). A functional model of hierarchy. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(1), 32–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386610380991

- Hargadon, A. (2006). Bridging old worlds and building new ones: Toward a microsociology of creativity. In L. Thompson & H.-S. Choi (Eds.), Creativity and innovation in organizational teams (pp. 199–216). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Helmreich, R. L., & Merritt, A. C. (2019). Culture at work in aviation and medicine: National, organizational and professional influences. Routledge.

- Henderson, V. E. (1932). Relationship between anesthetist, surgeon and patient. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 11(1), 5???11. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-193201000-00002

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. (Vol. 25). Harvard University Press.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Revised and expanded. (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Huang, X., Wilkinson, A., & Barry, M. (2023). The role of contextual voice efficacy on employee voice and silence. Human Resource Management Journal, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12537

- James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology. (Vol. 2).

- Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110(2), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.265

- Klein, G. (2003). Intuition at work. Currency/Doubleday.

- Klein, G. A. (2017). Sources of power: How people make decisions. MIT Press.

- Knoll, M., & Van Dick, R. (2013). Do I hear the whistle…? A first attempt to measure four forms of employee silence and their correlates. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(2), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1308-4

- Kobayashi, H., Pian-Smith, M., Sato, M., Sawa, R., Takeshita, T., & Raemer, D. (2006). A cross-cultural survey of residents’ perceived barriers in questioning/challenging authority. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 15(4), 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.017368

- Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. The Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.2307/259349

- Li, S., Jia, R., Hu, W., Luo, J., & Sun, R. (2023). When and how does ambidextrous leadership influences voice? The roles of leader-subordinate gender similarity and employee emotional expression. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(7), 1390–1410. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1991433

- Lin, X., Lam, L. W., & Zhang, L. L. (2020). The curvilinear relationship between job satisfaction and employee voice: Speaking up for the organization and the self. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 37(2), 587–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9622-8

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. sage.

- Little, M. (2002). The fivefold root of an ethics of surgery. Bioethics, 16(3), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8519.00281

- Malloy, D. C., Hadjistavropoulos, T., McCarthy, E. F., Evans, R. J., Zakus, D. H., Park, I., Lee, Y., & Williams, J. (2009).) Culture and organizational climate: Nurses’ insights into their relationship with physicians. Nursing Ethics, 16(6), 719–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733009342636

- Maner, J. K., & Mead, N. L. (2010). The essential tension between leadership and power: When leaders sacrifice group goals for the sake of self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018559

- Mawuena, E. K., & Mannion, R. (2022). Implications of resource constraints and high workload on speaking up about threats to patient safety: A qualitative study of surgical teams in Ghana. BMJ Quality & Safety, 31(9), 662–669. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014287

- Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why [Article. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453–1476. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00387

- Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

- Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. The Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725. https://doi.org/10.2307/259200

- Morrison, E. W., See, K. E., & Pan, C. (2015). An approach-inhibition model of employee silence: The joint effects of personal sense of power and target openness [Article]. Personnel Psychology, 68(3), 547–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12087

- Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(7), 941–966. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.413

- Oborn, E., & Dawson, S. (2010). Learning across communities of practice: An examination of multidisciplinary work. British Journal of Management, 21(4), 843–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2009.00684.x

- Patel, P. C., & Cooper, D. (2014). Structural power equality between family and non-family TMT members and the performance of family firms. Academy of Management Journal, 57(6), 1624–1649. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0681

- Peadon, R., Hurley, J., & Hutchinson, M. (2020). Hierarchy and medical error: Speaking up when witnessing an error. Safety Science, 125, 104648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104648

- Pfrombeck, J., Levin, C., Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2022). The hierarchy of voice framework: The dynamic relationship between employee voice and social hierarchy. Research in Organizational Behavior, 42, 100179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2022.100179

- Plato. (1998). The republic. (ed. and trans. Waterfield, R.). Oxford University Press.

- Quiamzade, A., & Mugny, G. (2009). Social influence and threat in confrontations between competent peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(4), 652–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015822

- Reed, P. G. (2016). Epistemic authority in nursing practice vs. doctors’ orders. Nursing Science Quarterly, 29(3), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318416647356

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, M. C., & Ormston, R. (2014). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Rousseau, J.-J. (2008). The social contract and the first and second discourses. Yale University Press.

- Rucker, D. D., Galinsky, A. D., & Magee, J. C. (2018). The agentic–communal model of advantage and disadvantage: How inequality produces similarities in the psychology of power, social class, gender, and race. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 58, 71–125.

- Saldana, J. (2011). Fundamentals of qualitative research: Understanding qualitative research. Oxford University Press.

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G

- Scarlet, S., & Dreesen, E. B. (2020). Should anesthesiologists and surgeons take breaks during cases? AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(4), 312–318.

- Schwappach, D. L. B., & Gehring, K. (2014). Saying it without words’: A qualitative study of oncology staff’s experiences with speaking up about safety concerns. BMJ Open, 4(5), e004740. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004740

- Spradley, J. (1979). The ethnographic interview. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Tarakci, M., Greer, L. L., & Groenen, P. J. (2016). When does power disparity help or hurt group performance? The Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(3), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000056

- Tiedens, L. Z., & Fragale, A. R. (2003). Power moves: Complementarity in dominant and submissive nonverbal behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 558–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.558

- Toma, C., Vasiljevic, D., Oberlé, D., & Butera, F. (2013). Assigned experts with competitive goals withhold information in group decision making. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(1), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2012.02105.x

- Tost, L. P., Gino, F., & Larrick, R. P. (2012). Power, competitiveness, and advice taking: Why the powerful don’t listen. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.10.001

- Urbach, T., & Fay, D. (2018). When proactivity produces a power struggle: How supervisors’ power motivation affects their support for employees’ promotive voice. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(2), 280–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1435528

- Van Vugt, M., Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2008). Leadership, followership, and evolution: Some lessons from the past. The American Psychologist, 63(3), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.182

- Wang, D., Waldman, D. A., & Zhang, Z. (2014). A meta-analysis of shared leadership and team effectiveness. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034531

- Weiss, M., & Morrison, E. W. (2019). Speaking up and moving up: How voice can enhance employees’ social status. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2262

- Whiting, S. W., Maynes, T. D., Podsakoff, N. P., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2012). Effects of message, source, and context on evaluations of employee voice behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 159–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024871

- Wilkinson, A., Barry, M., & Morrison, E. (2020). Toward an integration of research on employee voice. Human Resource Management Review, 30(1), 100677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.12.001

- Wilkinson, A., Townsend, K., Graham, T., & Muurlink, O. (2015). Fatal consequences: An analysis of the failed employee voice system at the Bundaberg Hospital. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 53(3), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12061

- Woolley, A. W., Chabris, C. F., Pentland, A., Hashmi, N., & Malone, T. W. (2010). Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science, 330(6004), 686–688. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1193147

- Zhang, T., Harrington, K. B., & Sherf, E. N. (2022). The errors of experts: When expertise hinders effective provision and seeking of advice and feedback. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 91–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.06.011