ABSTRACT

Stakeholders emphasise that accounting graduates need excellent teamwork skills. Group work activities, included in the academic programme to develop teamwork skills, often lead to ‘free-riding’ by some students and disillusionment on the part of diligent students. Diligent students often prefer to work alone and could lack teamwork skills as a result. The aim of this study was to evaluate how course design can facilitate the development of teamwork skills for diligent students with negative perceptions on group work. Detailed perception data on how a certain group work activity affected diligent students’ teamwork skills were collected via in-depth interviews. Themes identified through thematic analysis were compared to existing literature to construct recommendations on structuring group work activities for diligent students. The recommendations indicate that a challenging assignment conducted by a small group of students, selected on some form of commonality, over a substantial period, with limited lecturer instructions, incorporating both online and in-person components, without formal peer assessment, is best suited to foster the trust that is essential in teamwork and leads to open communication and ultimately collaboration. Educators could employ these recommendations when designing group work activities, especially when they note negative perceptions regarding group work in diligent students.

Introduction

As a result of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the accountancy profession is rapidly changing – with technology increasingly being integrated into everyday business activities, accountants perform fewer number-related tasks and more people-based tasks. These recent changes have increased the importance of accounting graduates being able to work in teams (De Bruyn, Citation2023; Dolce et al., Citation2020; Tan & Laswad, Citation2018; Tsiligiris & Bowyer, Citation2021; Vanhove et al., Citation2023). To develop teamwork skills, most accounting programmes include group work activities, which could stimulate creativity, foster learning and increase comprehension of technical content as well (Barkley et al., Citation2005; Burke, Citation2011). However, the main problem related to group work activities is ‘free-riding’ or ‘social loafing’, where some team members do not adequately contribute to the group, which could lead to frustration and disillusionment on the part of especially diligent students (Davies, Citation2009; Freeman & Greenacre, Citation2011; Gammie & Matson, Citation2007). Diligent students can be defined as competent, motivated, and conscientious students (Davies, Citation2009; Freeman & Greenacre, Citation2011; Gammie & Matson, Citation2007), who typically attempt to achieve high marks in academic tasks (Lee et al., Citation2017). Such diligent students might resort to rather delivering group tasks by themselves to ensure the achievement of top marks (Brown & McIlroy, Citation2011; Burke, Citation2011), struggle to develop teamwork skills (Lee et al., Citation2017) and perceive group work activities negatively (Healy et al., Citation2018). The aim of this study was to evaluate how course design can facilitate the development of teamwork skills for diligent students with negative perceptions on group work.

This study views teamwork as an essential component of cooperative, collaborative learning and employs a social constructivist lens (Edmond & Tiggeman, Citation2009; Healy et al., Citation2018; Lancaster & Strand, Citation2001). It is argued that previous group work experiences will affect how students approach subsequent group work activities and also the resultant teamwork skills developed (Hillyard et al., Citation2010). Owing possibly to previous negative experiences of group work or their own high-standards, diligent students often prefer to rather work alone than in a team (Barr et al., Citation2005; Brown & McIlroy, Citation2011). However, it is equally important for diligent students to develop the ability to compromise and work in a team (Lee et al., Citation2017), as it is to curb social loafing in a team. Indeed, it may be argued that teamwork is a threshold skill for an accounting student, but one often not attained by diligent students who receive high grades on their solo-authored work which could mask lower achievement relating to teamwork skills. While much research exists on managing free-riding and social loafing (Barac et al., Citation2021; Davies, Citation2009; Delaney et al., Citation2013; Edmond & Tiggeman, Citation2009; Freeman & Greenacre, Citation2011), very little work has been done focusing on the opposite angle – namely, the development of teamwork skills in hardworking and high-performing students, who often prefer to work alone (Lee et al., Citation2017). This study focuses on the aforementioned gap in accounting education literature.

Diligent students were interviewed to gather detailed data on how a certain group work activity affected their teamwork skills. The themes identified through thematic analysis were then compared to previous literature to develop recommendations on designing group work activities that improve diligent accounting students’ teamwork skills. The recommendations indicate that the trust, communication and collaboration required for teamwork are best developed when the group work has both online and in-person components, the task is challenging with limited lecturer instructions, the group work occurs over a longer period and the team consists of a small number of students but with some mutual interest. Informal peer assessment and self-assessment were encouraged, but participants believed that summative peer assessment would decrease trust in the team.

Contribution

This study adds to the current debate on how best to develop teamwork skills in academic programmes. It focuses on a previously under-researched topic, namely diligent students who have been disillusioned by previous group work activities, owing to free-riding and their own desire for control, and thus often prefer to work on their own. This study identified crucial elements in the design of group work activities that facilitate the perceived development of teamwork skills in this group of students. Educators who seek to integrate more group work activities in their modules and programmes could employ the recommendations to ensure that they structure group activities optimally for diligent students. Moreover, these recommendations could be employed when educators note that diligent students have negative perceptions about group work activities. The study also focused on identifying the qualitative aspects (trust, communication and collaboration) which led to diligent students experiencing real teamwork, rather than purely group work, and contributes to the ongoing debate on peer assessment in group work.

The paper is organised in the following order. First, the research context is provided, followed by the literature review and research methodology. Then the findings from the interviews are discussed and compared to existing literature related to the findings. Finally, conclusions and recommendations are provided.

Research context

The setting for the research was a large residential university in South Africa. To become chartered accountants, students need to complete both an undergraduate and a postgraduate degree in accounting. Students who perform well at undergraduate level (achieve an average of 70%, or higher, for their final year subjects) can choose to add a voluntary research module to their postgraduate studies, which then makes their postgraduate qualification an Honours degree instead of a postgraduate diploma. This study focused on the postgraduate research module, as the students registering for this module were deemed to be diligent students (having achieved high marks during their undergraduate studies and motivated enough to register for a voluntary module) – and thus suitable for the research purposes. In 2021, when the research was executed, the module was delivered fully online owing to COVID restrictions, although it is usually delivered using a blended mode of delivery.

The research module is a 30-credit module, which translates to 300 notional hours for students. The overall module outcomes stated that, after the completion of the module, students should be able to adopt a structured (and ethical) approach to solve a research problem; apply critical thinking skills to solve a research problem and formulate a coherent argument to substantiate a point of view; conduct research independently and in a group setting as part of a team; identify, demarcate and grasp the exact details of a specific research problem in order to focus on the problem statement; identify and interrogate information that is relevant to the research problem; apply integrated thinking and problem-solving skills in the field of accountancy; manage, and respond to, constructive feedback by a supervisor in a professional manner; distinguish between facts and opinions when substantiating a point of view; and communicate research findings in a professionally written document and during an oral presentation.

During the research module, students were required to complete a research project on an accounting-related topic. While half of the marks in the module were awarded for individual work, the other half of the marks were awarded for group work. Assuming that half of the notional hours are spent on group work, the group work equated to a total of 150 h during the year. The 19 students registered for the module in 2021 were divided into five groups (3 or 4 students per group), based on their interest in the topics provided. As indicated by Bayne et al. (Citation2022), students attended a workshop on relational skills at the start of the academic year, to prepare them for the group work, and were familiarised with the online collaboration tool (MS Teams). The following collaborative group activities were included in the module: making decisions about the research topic, drafting the research proposal, delegating research tasks to individual team members, writing the final research report, and presenting the research in an oral presentation.

From informal discussions with students, two major points were noted: Many of the students came into the module with pre-existing negative perceptions about group work in the academic programme (owing to previous exposure to free-riding, which often resulted in them doing most of the work for a group project by themselves); and most of the students reported very positive experiences of the group work in the research module as well as accompanying perceived increases in their teamwork skills. This led to the researchers employing the research module as a case study to determine how the design of the group work activities effected this change in perception and the perceived development of teamwork skills.

Literature review

The literature review, firstly, broadly examines the importance of non-technical skills in accounting education. Secondly, it focuses more specifically on teamwork skills. Teamwork skills are defined, the development of teamwork skills through group work activities in the accounting curriculum is substantiated, possible reasons for diligent students’ negative perceptions relating to group work are explored and, finally, the main findings of previous research on the appropriate structuring of group work activities are summarised.

The importance of non-technical skills in accounting education

Employers increasingly require accounting graduates to have non-technical skills (Howcroft, Citation2017; Mhlongo, Citation2020; Tan & Laswad, Citation2018; Tempone et al., Citation2012), including teamwork, communication, leadership, critical thinking, emotional intelligence and self-management skills (De Bruyn, Citation2023; Howcroft, Citation2017; Tsiligiris & Bowyer, Citation2021; Vanhove et al., Citation2023). Such skills increase graduates’ chances of finding employment and is associated with career success (Vanhove et al., Citation2023). Many prior studies found that employers are concerned about the employment readiness of accounting graduates, owing to their lack of non-technical skills (Dolce et al., Citation2020; Jackling & De Lange, Citation2009; Oosthuizen et al., Citation2021; Succi & Canovi, Citation2020). It is therefore clear that future employers have specific requirements for accounting graduates: they need to be technically competent and also have excellent non-technical skills.

Professional accounting bodies also indicate that accounting graduates must be employment-ready, by having both discipline-specific (technical) skills and non-technical skills (De Villiers, Citation2010; Helliar, Citation2013; Howcroft, Citation2017; Oosthuizen et al., Citation2021). For example, the International Accounting Education Standards Board, in collaboration with the International Federation of Accountants, revised their professional skills requirements regarding interpersonal and communication skills (which include teamwork, collaboration and communication) to an intermediate level – which is the same level required for technical abilities (International Education Standard Citation3, Citation2019). In Australia and New Zealand, the Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand (CA ANZ) also emphasised the importance of teamwork skills, in various technical and non-technical areas, in their latest competency framework (CA ANZ, Citation2023). The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) include soft skills, such as teamwork and communication skills, as part of their professional development plan (ICAEW, Citation2020). In South Africa, the South African Institute for Chartered Accountants (SAICA) foregrounded the development of non-technical skills (labelled ‘enabling competencies’) in the accounting curriculum through the issuance of the CA2021 competency framework (CA2021 CF) (SAICA, Citation2021). The enabling competencies included in the CA2021 CF are business, decision-making, relational and digital acumen (SAICA, Citation2021).

The increased focus on non-technical skills, by both employers and professional bodies, thus places pressure on educators to develop these skills in students during the academic programme (De Bruyn, Citation2023; Howcroft, Citation2017; Tsiligiris & Bowyer, Citation2021). Academics need to include non-technical skills in their module outcomes, learning activities, and assessments. The problem now faced by accounting educators is finding the time, and adapting their teaching styles, to develop non-technical skills in an already full technical curriculum (De Bruyn, Citation2023; Low et al., Citation2013; Paisey & Paisey, Citation2007). As pointed out by Wye and Lim (Citation2009), the technical skills taught at some universities do not facilitate the development of the non-technical skills required by employers, creating a mismatch between what employers desire and what graduates deliver.

Teamwork skills in accounting education

A team is described by Katzenbach and Smith (Citation1999, p. 45) as ‘a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable’. Teamwork enables the products delivered by a team to constitute more than the simple sum of the individual contributions of team members, as all team members are committed to the team goal and contribute their complementary skills to delivering the final product (Bryant & Albring, Citation2006; De Bruyn, Citation2023). In this way, teamwork differs from basic group work (which merely constitutes the ‘simple sum of individual contributions’ in a group work exercise) owing to the presence of synergy benefits. Basic group work further focuses more on the individual’s roles, tasks and responsibilities, as a group member is only accountable for their own actions, while in teamwork there is individual and mutual accountability. Moreover, teamwork emphasises the collective success of the team over individual success or failure (Katzenbach & Smith, Citation1999). The CA2021 CF (SAICA, Citation2021) confirms these teamwork elements by requiring that the following teamwork skills be developed in students during South African academic programmes: being a trustworthy and resourceful team member; openly sharing knowledge; compromising and collaborating to achieve the team goals; delegating tasks; managing conflict situations; sharing responsibility for the group task; and valuing individual contributions to the team.

It has become essential to develop students’ teamwork skills as part of the accounting curriculum since such skills are important for the accountant of the future (Bayne et al., Citation2022; De Bruyn, Citation2023; Dolce et al., Citation2020; Tan & Laswad, Citation2018; Tsiligiris & Bowyer, Citation2021). Previous research has indicated that group work activities such as case studies, projects, essays, simulations and oral presentations (also termed cooperative learning) should be included in the accounting curriculum to develop teamwork skills (Bayne et al., Citation2022; Tsiligiris & Bowyer, Citation2021; Viviers, Citation2016), although most accounting educators are not trained in designing such activities (Clinton & Kohlmeyer, Citation2005). Effective group work activities, which lead to the development of teamwork skills, should emphasise the development of relational acumen and teamwork skills (inputs into the process) as much as the technical outputs produced by the group work (Riebe et al., Citation2016). In addition to developing students’ teamwork skills, group work activities can stimulate creativity, enhance problem-solving skills and facilitate a deeper understanding of technical content (Burke, Citation2011). Students’ emotional intelligence can grow through group work as they become more self-aware regarding their own interpersonal strengths and weaknesses, and learn to work together with other people with different personalities (Bayne et al., Citation2022). Moreover, group work activities assign responsibility to each student – turning an activity from a passive to an active one (Bourner et al., Citation2001).

However, group work does not automatically facilitate the development of teamwork skills (Bryant & Albring, Citation2006; De Bruyn, Citation2023; Opdecam & Everaert, Citation2018), owing to problems like ‘copy-and-paste’ efforts, free-riding and other social issues (Davies, Citation2009; Freeman & Greenacre, Citation2011; Gammie & Matson, Citation2007). Brown and McIlroy (Citation2011) reviewed several papers dealing with students’ perceptions about group work activities and concluded that, rather than learning to value group collaboration through group work, students can often attach a negative learning experience (such as being frustrated and experiencing higher stress levels) to group work activities. Healy et al. (Citation2018) studied students’ undergraduate group work experiences in activities such as case studies, group projects and group exercises. Students described the group work as frustrating and time-consuming (Healy et al., Citation2018). Healy et al. (Citation2018) further found that high-achieving students generally held a more negative view of group work than the average student, as they considered the products produced by group work to be of a lower standard than what they could produce individually and were concerned about free-riders. These problems emphasise the importance of structuring group work activities appropriately to engage students and truly develop their teamwork skills (Bayne et al., Citation2022).

Johnson and Johnson (Citation2009) assert that group work is successful when positive social interdependence is achieved in the group, i.e. ‘when the outcomes of individuals are [positively] affected by their own and others’ actions’. Bayne et al. (Citation2022) drafted best practice recommendations for group work activities that are assessed and proposed that: groups be randomly allocated (although lecturer-selection might also be appropriate); students should be prepared for group work through a workshop or lecture on teamwork and instructions regarding the online collaboration tools to be employed; assignments should require interdependence and collaboration, without allowing students to merely divide the work between themselves; continuous teambuilding should take place, with the availability of lecturer guidance; and teamwork should be explicitly assessed, for example using peer assessment. Additional literature on the structuring of group work activities will be discussed in depth when presenting the findings of the present study.

Research methodology

The aim of this study was to evaluate how course design can facilitate the development of teamwork skills for diligent students with negative perceptions on group work. Most prior studies on teamwork have utilised quantitative methodologies (Riebe et al., Citation2016), and thus it was decided to follow a qualitative approach to collect detailed data relating to students’ perceptions of the group work activities and teamwork skills development in the research module. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews (Bayne et al., Citation2022; Oosthuizen et al., Citation2021) and then analysed thematically. The findings from the analysed data were employed to draft recommendations on the structuring of group work activities, which were compared to findings from prior research. The research was approved by Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University (project number 23663). More details regarding the development of the interview guide, data collection and data analysis are provided below.

Development of the interview guide

The interview guide was developed to reach the research aim and employed the CA2021 CF’s definition of teamwork skills. Students were first asked a closed-ended question relating to their perceptions about their teamwork skills – to ease the participants into the interview. Participants were then asked to share their views on perceived teamwork skills development during the group work activities in the module through several open-ended questions (Bayne et al., Citation2022). The following questions were included in the interview guide (the CA2021 CF definition of teamwork skills was provided to participants prior to the interview):

Q1: Please rate yourself (between 0% and 100%) on the teamwork skills in the CA2021 CF before and after the group work in the research module.

Q2: Please tell me more about your experiences as a group member during the research module.

Q3: Which teamwork skills do you think you improved in the most, and why?

Q4: Thinking back on the group work during the research module: which aspects facilitated the development of teamwork skills, and why?

Q5: Thinking back on the group work during the research module: what could be improved to make it easier/improve the development of teamwork skills?

Recruiting of participants and data collection

After the module had been completed (and all students had received their results), all 19 students registered for the module in 2021 were invited to participate in the research. A total of eight students volunteered and completed an electronic form giving informed consent (these eight students are hereafter referred to as participants). Semi-structured one-on-one online interviews were conducted (Bayne et al., Citation2022) with the eight participants, with one of the researchers acting as interviewer. The interviewer was also the module coordinator for the module, but it was not believed that this would have made the participants reticent to share their views as they had already received their results (Bayne et al., Citation2022) and were soon graduating from university. The researchers believed the module coordinator best suited to conduct the interviews owing to her in depth understanding of the module. The interviews lasted between 20 and 40 min each, and gathered detailed data relating to participants’ views on the development of teamwork skills.

Although more participants would have been desirable, no additional students volunteered to participate in the research, and no students outside the 19 registered for the module had in depth knowledge about the group work activities employed. However, data saturation was evident during the latter interviews as no new information or ideas were noted and participants kept providing similar answers for specific questions (Saunders et al., Citation2018). Moreover, very few contradictory views were noted during the interviews. The 19 students had been divided into one of five groups for the module, and the eight participants represented four of the five groups, also showing that further interviews were not likely to uncover contradictory views. The contribution of the study lies in the detailed nature of the data collected rather than the number of participants.

Data analysis

The interviews were voice recorded, with permission of the participants, and transcribed. The qualitative data from the open-ended questions (Q2 – Q5) were analysed thematically (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) to identify themes relating to teamwork skills. Course design recommendations for group work activities, to engage diligent students with existing negative perceptions on group work, were also developed, and then compared to existing literature. As the course design recommendations for engaging diligent students in group work activities were generated in a small class setting (approximately 20 students), a separate section focuses on evaluating the appropriateness of the recommendations proposed by this study for large class settings, by specifically referring to participants’ views of group work in large class settings (based on their undergraduate studies) as well as existing literature.

Findings

The findings, firstly, focus on participants’ perceptions on group work activities prior to the research module. Secondly, the perceived development of teamwork skills as a result of the module is explained. Thirdly, the course design elements which facilitated the perceived development of teamwork skills are explained, culminating in the recommendations for designing group work activities which engage diligent students with existing negative perceptions on group work. Finally, the process through which the course design elements facilitated the perceived development of teamwork are discussed.

Perceptions on group work activities prior to the research module

One participant echoed what the general sentiment of most of the participants was: ‘I've never enjoyed a group project at university until this one [the research module]’. Not having a good teamwork experience prior to this research module was the result of participants being grouped, at undergraduate level, with students who were not as conscientious as they were. As such, the participants felt that they ended up doing most of the work, taking the lead or even re-doing the work of their fellow team members (because the work failed to meet their expectations or standards). As one participant stated, showing their frustration with free-riders as was also mentioned by Healy et al. (Citation2018):

[In the] past with group projects I've taken up most of the responsibility myself, especially in university. Because working with other people you just get put in groups and I feel like I've taken like 90% of the responsibility of getting the work done and getting everyone else to work and making sure everyone else does their work.

Doran et al. (Citation2011) reported that students found it difficult to manage the group work, and often merely subdivided the tasks unless lecturer instructions necessitated them to do otherwise. Similarly, almost all participants referred to their undergraduate group projects as an independent endeavour, where each member simply did their part, and the different parts were merely combined (copied and pasted) to form the group project, as evidenced by this quote: ‘Undergrad was more like let's say A does that piece, B does that piece and C does that piece, and you just put it together’. Another participant noted that, in undergraduate, ‘[e]verybody just copies and pastes everything together with almost no editing’ – providing evidence of a lack of synergy in students’ undergraduate group work activities. This confirmed the fact that there is a difference between group work and actual teamwork. Teamwork requires synergy among team members, which means that the final product is more than a mere amalgamation of several students’ work, as students need to employ complementary skills to improve the final product (Bryant & Albring, Citation2006). Bayne et al. (Citation2022) emphasise that group work activities should be designed to facilitate discussion and collaboration. Poor design of the group work activities in students’ undergraduate studies could have contributed to the lack of synergy reported, which accentuates the need for the present study.

It is clear from the participants’ similar experiences at undergraduate level that they did not experience teamwork, but rather simple group work. As stated by one of the participants: ‘When you have trust in a team [group], you can develop teamwork’. The participants’ undergraduate experiences in group work therefore did not enable them to reach the standard of teamwork required in the CA2021 CF (SAICA, Citation2021), which encompassed: being a trustworthy and resourceful team member; openly sharing knowledge; compromising and collaborating to achieve the team goals; delegating tasks; managing conflict situations; sharing responsibility for the group task; and valuing individual contributions to the team.

Teamwork skills perceived to be developed during the module

Participants were asked to rate their teamwork skills (based on the CA2021 CF definition) before and after the research project, using a scale of 0% to 100% developed. The average participant rating was 62% before the group work in the module, and 85% afterwards. The average perceived improvement of 23% was deemed substantial and indicated that the group work activities were, on average, seen to be effective in developing participants’ teamwork skills. This supported the use of this intervention as a case study for evaluating how course design can facilitate the development of teamwork skills for diligent students with negative perceptions on group work, and then providing recommendations in this regard.

When participants were asked in which of the SAICA teamwork skills categories they perceived the most improvement during the research module, seven of the eight participants (88%) highlighted their ability to trust their team members as their biggest growth point. As one participant stated: ‘I could wholeheartedly trust [my group members]’. This was the result of having confidence in their team members’ scholarly capabilities and the members being equally conscientious. Six of the eight participants (75%) further noted that they could more easily delegate tasks and share responsibilities for the group task – which stands in stark contrast to their response to undergraduate group projects where the participants ‘didn’t really give the other team members a chance’. Most of participants also said that they valued their team members’ individual contributions. Valuing others’ contributions does not always come naturally to diligent students, who often believe a group product to be inferior to that which they could have produced on their own (Healy et al., Citation2018). Thus, the participants’ comments provide evidence of growth in their teamwork skills and of their changing views on the value of group work.

Managing conflict did not feature in the participants’ comments, since they seemed to value each other’s opinions and contributions and enjoyed mutual respect during the research module. Consequently, few or no disagreements had to be managed. This is aligned to a quote from Opdecam and Everaert (Citation2018, p. 227) which stated: ‘By involving only highly motivated students in a cooperative learning setting, teams have fewer problems not getting along with each other, since the setting was a well-informed choice’. The students who complete the research module all do so voluntarily and are therefore seen as highly motivated. As noted by one participant: ‘I was working with people that had the same mindset and the same drive as I had, and that was such a positive experience’.

Which course design elements facilitated the development of teamwork skills?

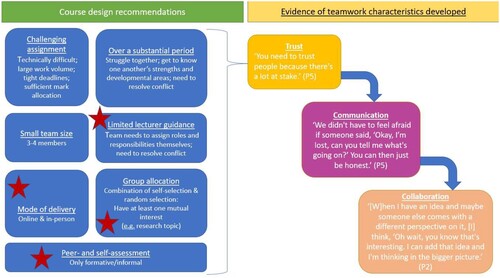

The participants highlighted several course design elements which facilitated their perceived development of teamwork skills. Based on these elements, the left-hand side of presents the recommendations for designing group work activities when negative perceptions relating to group work are noted in diligent students. Those recommendations that are novel (or partially disagree with existing research) are emphasised by a star. The course design elements are now discussed individually.

Figure 1. Group work design recommendations for diligent students, and its interaction with the development of teamwork skills.

Challenging assignment

The degree of technical difficulty of the assigned research topics was perceived ‘to be challenging enough’ to facilitate the development of teamwork skills. Participants felt that they would not have succeeded on their own and reported that group work needs to have a challenging assignment ‘[o]therwise, you wouldn’t need your team members’. This finding agreed with a best practice recommended by Bayne et al. (Citation2022) that assignments should be designed to require interdependence and collaboration, otherwise students would merely divide the work between themselves. Davies (Citation2009) also emphasised that group work tasks should be stimulating and complex. The amount of work and tight deadlines also facilitated teamwork (rather than mere group work), as pointed out by a participant who stated:

This research task is something like we've never done before. This level of sophistication, technical research and knowledge caused us to have to rely on each other to get through this. You learn from each other since this is something you have not seen or done before – you had to work as a team to get through it.

Over a substantial period

Another aspect of the course design that increased teamwork was the length of the project. This project required continuous and regular interaction between team members for almost eight months, which differed from the shorter group interactions typical in undergraduate studies. ‘In undergrad, most of the projects we did always was like a last-minute thing’, a participant admitted, which would not have allowed teamwork skills to develop optimally. Marks et al. (Citation2001) confirmed that teams that work together over longer periods of time are more likely to develop team cohesion. Davies (Citation2009) emphasised that allowing groups to work together over prolonged periods will reduce free-riding, and will foster open communication between group members (leading to a focus on the groups’ output rather than individuals’ output). As team members work together over time, they become familiar with each person’s individual working style, and roles and responsibilities usually become clear (Schmutz et al., Citation2019), which is not possible if the group work only occurs over a short period.

Small team size

What also seemed to have aided the effective teamwork was the size of the teams – all groups consisted of only three or four members. Groups were thus small enough to meet with ease and communicate and delegate tasks effectively, as was also confirmed by Hoegl (Citation2005). Moreover, the small group size necessitated all members to pull their weight. As indicated by one participant: ‘The size really helped. [W]hen the groups are too big, there's always those people that just don't do anything and you don't even notice they aren't doing anything [be]cause there's so many other people’. Smaller teams thus allow greater effort by all team members (reducing the chance of certain members not participating); hence, a better utilisation of all team members’ potential and improved teamwork (Hoegl, Citation2005). Davies (Citation2009) confirmed that smaller groups reduce the risk of free-riding.

Limited lecturer guidance

Berry (Citation2007) stated that having to work with each other without lecturer input, forces students to improve their interpersonal skills, including communication and interdependence. In line with Berry (Citation2007), participants in this study felt that the limited lecturer instructions on how the group work should be organised, increased the necessity for teamwork, as roles and responsibilities had to be negotiated by themselves. Students in the present study were provided only with high-level guidance (information on the research topic and the deliverables, i.e. what outputs should be produced), with the bulk of the detailed decision-making (such as assigning roles and responsibilities, time- and self-management, communication and conflict management) left mostly up to the group. Participants contrasted the limited lecturer guidance in the research module with their undergraduate experiences, by stating:

We did some teamwork and projects in undergrad, but it was more, I'd say, cookie cutter frameworks that we just followed. The instructions were pretty clear and the lecturers always gave very – like a solid framework for divid[ing] the work this way or we suggest this method of dividing it.

Mode of delivery

Whether group work occurs online, in-person or using a blended approach could affect student perceptions thereof and the perceived level of teamwork skills developed. A recent study by Rezaei (Citation2017) indicated the benefits of online collaboration, where online discussions are time-independent and allows for ‘many-to-many’ interactive communication, facilitating group work. However, Donelan and Kear (Citation2023) indicated that online group work could lead to low and uneven participation by students, a lack of clarity and poor relationships. Friedman et al. (Citation2009) also found that online collaboration led to more off-topic discussions, slower response times and more socially inappropriate behaviours (for example, leaving an online room without providing an explanation). Other research on the relative superiority of online versus in-person group work was not conclusive (Smith et al., Citation2011) and in some cases seemed to yield a very similar results in terms of teamwork development (Goñi et al., Citation2020).

In this study, all group work occurred online owing to COVID-19 restrictions. Some participants highlighted the effectiveness of online collaboration, stating for example: ‘We could meet in a lot more time frames during the day, which helped a lot in such a busy year where we don't have to be confined to just the time, we were all on campus’. Some participants also noted that one could easily get distracted in online group work, and that it is harder to build a relationship in the online environment, however the online collaborative tools (such as MS Teams) assisted students to work together effectively and efficiently during the project. Therefore, it is concluded that a blended approach to group work would optimally facilitate the development of teamwork skills.

Group allocation

Literature suggests that there are different ways of group formation, including self-selected groups (where students assign themselves to a group), lecturer-determined groups (based on, for example, students’ gender, language, prior grades, learning styles or personality profiles) and randomly selected groups (Ballantine & Larres, Citation2007; Bayne et al., Citation2022; Chapman et al., Citation2006; Edmond & Tiggeman, Citation2009). Students in self-selected groups communicated better, were more enthusiastic and confident in other team members’ abilities, could resolve conflict and ask for help easily, were less likely to do others’ work, but struggled more with time management (Chapman et al., Citation2006). Moreover, student self-selection ‘does not guarantee the heterogeneity and diversity of perspectives within a group’ (Ballantine & Larres, Citation2007) which is important to truly develop teamwork skills.

Berry (Citation2007) argues that randomly selected groups simulate teams in the workplace. Doran et al. (Citation2011) and Bayne et al. (Citation2022) also advise using this method to allocate students to groups. Random groups also have better time management (Chapman et al., Citation2006). However, one of the participants in the present study mentioned, in relation to undergraduate group work, that when you ‘are put with people online that you don’t know, it's really hard’. Participants in the present study mentioned that group work in the research module was easier because all team members were conscientious and academically strong students. It makes students ‘want to work harder, when [they]'re surrounded by people that also wanted to work hard’. Thus, having team members who share for example the same work ethic seemed to have aided the development of teamwork skills.

In the present study, groups were assigned based on students’ interest in the available research topics. Students ranked the available topics from most preferred to least preferred and were then assigned based on these preferences. Students all received one of their preferred topics (one of their top three topics), which made them excited to contribute to the group work activities. The allocation method employed in this module was therefore a combination of self-selection (in terms of the topic) and random selection (as no further criteria were applied to form the groups). This method of group formation partially agrees with prior research (Bayne et al., Citation2022), but also highlights that the functioning of random groups can be improved if one mutual interest is present (for example, interest in a certain research topic).

Peer assessment and self-assessment

Student self-assessment has been suggested as a valuable tool to assess the development of teamwork skills in the curriculum, while peer assessment could also be employed (Barac et al., Citation2021; Boud & Falchikov, Citation2007; Delaney et al., Citation2013; King & King, Citation2021). However, Delaney et al. (Citation2013) found that accounting students disliked a system where their marks for technical components were adjusted based on a peer assessment of their teamwork contribution. Although peer assessment is not always perceived by students to be accurate, valid or fair (Barac et al., Citation2021; Opdecam & Everaert, Citation2018), it could reduce free-riding (Bayne et al., Citation2022; Sridharan et al., Citation2018), be employed to allocate marks for group activities to individual students (Bayne et al., Citation2022) and increase student engagement (Adesina et al., Citation2023). Therefore, the existing literature does not fully agree on the value of peer assessment and how it should be implemented, especially with diligent students in mind.

As the research module did not include a peer assessment process, the participants were asked whether they thought it would be a good idea if the group project included a process whereby group members could rate one another on their teamwork skills shown during the project (and this rating would then be included as a part of their mark). Only one participant thought it could be a good idea, whereas all other participants felt that it would break the trust bond that had been formed and that one would then not want to be open and vulnerable (to ask questions or state your weaknesses) owing to being afraid of being rated poorly on these weak points. As noted by one participant:

If I tell you at the start you are going to rate the other people around you – would you build trust or live in fear? Then you might fear or think I’m not allowed to say I'm struggling with this because they are going to rate me poorly, so maybe that will not help to build trust.

Prior research has also suggested using formative feedback (Barac et al., Citation2021; Sridharan et al., Citation2018). Participants agreed and stated that fellow team members should not rate one another per se, but rather give feedback on team members’ strengths and weaknesses in terms of teamwork and enabling future growth opportunities for each team member.

How did the course design elements facilitate the development of teamwork skills?

Some themes (trust, communication and collaboration) were identified from participant comments, which emphasised the qualitative factors that need to be present in group work activities, for such activities to truly develop students’ teamwork skills (). Specifically, the course design elements facilitated the development of trust between team members, which led to open communication and finally collaboration between the members – allowing the group to function as a team. This process is visualised in and explained next.

Table 1. Themes and sub-themes relating to teamwork skills development.

Trust

Appropriate course design created the need and opportunity for trust in the team. The participants felt that their team members were reliable and they valued each other’s input, which ultimately led to respect for each other. As one participant stated: ‘I definitely valued their contributions a lot more because I could trust them and rely on them to put in the work’. Similar to Tseng and Yeh (Citation2013), participants considered individual accountability, commitment toward quality work and team cohesion as important factors for building trust in the group.

Communication

There was also constant open communication on matters such as work delegation (what needs to be done and by when). Team members volunteered to do certain sections and there was willing participation from all members. There was even open communication about members’ own strengths and weaknesses, where they were being vulnerable with their fellow team members. Many teams assigned responsibilities based on their team members strengths, to ensure the best results possible. As one participant noted: ‘We focused on each of our specific strengths – on the areas which we might know the most of or have the most background knowledge on, e.g. who is better at writing’. Participants specifically noted that they communicated frequently and without feeling inhibited. With adequate communication, there seemed to be limited misunderstandings as minimal conflict was experienced.

Collaboration

There was also a strong sense of collaboration where ideas were openly shared and where team members could freely ask questions if they were unsure, help each other, and experience no judgement from other team members. As one participant noted:

We all had a different viewpoint on a certain topic, but it wasn't like I’m right and you’re wrong. In the end, if you could call it ‘conflict’, you create a better output because now you've debated, and you thought about it. So even that conflict can then produce a more quality product.

Team members sometimes reviewed each other’s work (‘We'd do our separate parts in our own time and then we'd … go through line by line [and] comment on it’) and were open to receive constructive feedback as they were open to learn from each other as equals. Also noted was a willingness to compromise and a strong sense of respect for each other, which probably decreased conflict within the teams.

Engaging diligent students in group work in large class settings

This study provided useful insights into what diligent students value in group work activities. During the interviews, participants emphasised the process through which the course design elements facilitated the development of teamwork skills, namely that the course design created trust, which led to open communication and later collaboration (). As this study gathered diligent students’ perceptions in a small class setting, the course design recommendations would be especially pertinent to small class settings. It would, however, be useful to consider whether and how the recommendations generated by this study could be applied in large class settings. During their undergraduate studies, the participants formed part of large class groups – as is the norm for many accounting students. Reflecting on their undergraduate experiences, participants identified that they struggled to trust their group members during undergraduate group work (‘I didn't share my responsibilities [and] I wouldn't necessarily trust my group’). As trust was identified as the primary activator for the development of teamwork skills (as shown in and ), it is important, in both small and large class settings, to structure group work in a way that facilitates trust between group members.

In this study, trust was facilitated by the course design elements set out in . Moreover, in line with Schmutz et al. (Citation2019), many participants emphasised that trust, communication and collaboration came about when they realised that group members had complementary skills (). One participant, speaking about their group members in undergraduate projects, stated that distrust was a result of not ‘know[ing] the[ir] competencies or … what they are capable of’. During their undergraduate studies, the participants often felt they, themselves, were ‘the most reliable person that [they] know’. Not being aware of the skills of other group members, and the assumption that they were the most reliable team member, may have hindered diligent students from exhibiting and developing teamwork skills during undergraduate group work.

In large class groups, diligent and high-achieving students need to realise the necessity of developing their own teamwork skills (i.e. that group work is not only about the technical outcome of the project, but also about skills development). To help diligent students respect, and ultimately trust, their group members, they should become familiar with their team members (Tseng & Yeh, Citation2013) to enable them to identify the strengths of others in the group (Schmutz et al., Citation2019). This could be achieved by scaffolding the project – by including multiple steps or activities in a way that foregrounds the different skills of group members or by having the group work occur over a substantial period (Christensen et al., Citation2019). Students could also be upskilled regarding different behavioural profiles, learning styles or team roles (using, for example, the DISC profile, Myers–Briggs Type Indicator, Kolb’s Learning Style Index, or Belbin’s team roles) to better prepare them for engaging in group work (Aranzabal et al., Citation2022; Missingham & Matthews, Citation2014; Steenkamp & Goosen, Citation2023). Activating their emotional intelligence (De Bruyn, Citation2023; Steenkamp & Goosen, Citation2023) will help diligent and high-achieving students to realise that all group members have strengths to contribute to the group, even if those skills differ from their own. This will establish trust and ultimately communication and collaboration.

In , the course design recommendations identified by this study are reiterated and their appropriateness for usage in large classes are practically evaluated by considering existing literature and interview data (specifically, participants’ reflections regarding their undergraduate studies where large class groups were the norm). Possible adjustments for large class settings, identified from literature and participants’ responses, are also provided in .

Table 2. Applicability of course design recommendations in large class settings.

Conclusion

Employers and professional accounting bodies are increasingly emphasising the importance of accounting graduates having non-technical competencies, such as teamwork skills. Accounting educators realise the importance of developing students’ teamwork skills and thus include more group work activities in the academic programme, but students (including diligent students) often develop negative perceptions relating to group work owing to free-riding by other students. As such, diligent students might not develop the necessary teamwork skills, as they merely do the group work by themselves. The aim of this study was to evaluate how course design can facilitate the development of teamwork skills for diligent students with negative perceptions on group work.

Diligent postgraduate accounting students registered for a research module, which included substantial group work activities, were interviewed. It is important to realise that group work does not automatically develop teamwork skills, as noted by multiple participants in relation to their undergraduate experiences of group work. However, all participants reported an improvement in their teamwork skills because of the group work in the research module. The biggest growth areas were in trusting their team members, in developing mutual respect and valuing each other’s opinions, and in being able to delegate and share responsibilities.

The course design elements which led to the perceived development of teamwork skills were identified and, based on this, recommendations were developed for designing group work activities when negative student perceptions are noted in diligent students. A blended approach to group work (utilising both online and in-person elements) was advised. Moreover, a challenging assignment conducted by a small group of students, selected based on some form of commonality (for example, interest in a research topic), over a substantial period, with limited lecturer instructions, is best suited to foster the trust that is essential in teamwork and leads to open communication and ultimately collaboration. In this context, participants believed that peer assessment should only be done informally and for formative purposes, although this recommendation might not hold true in all contexts, modules and year groups. As the recommendations were designed with diligent students in mind, some recommendations are novel or contradict existing literature. These novel or contradictory recommendations are:

Explicitly applying a blended mode of delivery for the group work, by including both online collaborative tools and in-person activities;

Limiting lecturer guidance, whereby students are required to assign roles and responsibilities themselves, as well as manage conflict;

Allowing for a combination of self-selection and random selection of group members; and

Not prescribing summative peer assessments as this would lead to distrust and an unwillingness to be vulnerable and learn from one another.

While prior research relating to group work has mostly focused on managing free-riding and social loafing, this study addressed an under-researched area, namely engaging diligent students with existing negative perceptions on group work in the academic programme. The study adds to the ongoing debate on optimally structuring group work in accounting programmes, and specifically provides additional perspectives relating to group selection and peer assessments. The study also emphasised the qualitative factors, such as trust, communication and collaboration, that provide evidence of group work activities that truly develop students’ teamwork skills. A limitation of the study is the small number of participants interviewed and the fact that it was only conducted at a single university. Moreover, the recommendations and findings of the study are limited to diligent students and might not be applicable to all types of students, or all contexts. Future studies could evaluate the effectiveness of other group work activities at other universities, and specifically consider the effect of different types of group work activities on students of varying academic strength and levels of conscientiousness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adesina, O. O., Adesina, O. A., Adelopo, I., & Afrifa, G. A. (2023). Managing group work: The impact of peer assessment on student engagement. Accounting Education, 32(1), 90–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2022.2034023

- Aranzabal, A., Epelde, E., & Artetxe, M. (2022). Team formation on the basis of Belbin’s roles to enhance students’ performance in project-based learning. Education for Chemical Engineers, 38(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ece.2021.09.001

- Ballantine, J., & Larres, P. M. (2007). Final year accounting undergraduates’ attitudes to group assessment and the role of learning logs. Accounting Education, 16(2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639280701234419

- Barac, K., Kirstein, M., & Kunz, R. (2021). Using peer review to develop professional competencies: An Ubuntu perspective. Accounting Education, 30(6), 551–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2021.1942089

- Barkley, E. F., Cross, K. P., & Major, C. H. (2005). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Barr, T. E., Dixon, A. L., & Gassenheimer, J. B. (2005). Exploring the “lone wolf” phenomenon in student teams. Journal of Marketing Education, 27(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475304273459

- Bayne, L., Birt, J., Hancock, P., Schonfeldt, N., & Agrawal, P. (2022). Best practices for group assessment tasks. Journal of Accounting Education, 59(1), 100770–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2022.100770

- Berry, E. (2007). Group work and assessment - benefit or burden? The The Law Teacher, 41(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069400.2007.9959723

- Boud, D., & Falchikov, N. (2007). Rethinking assessment in higher education learning for the longer term. Routledge.

- Bourner, J., Hughes, M., & Bourner, T. (2001). First-year undergraduate experiences of group project work. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 26(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930020022264

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, C. A., & McIlroy, K. (2011). Group work in healthcare students’ education: What do we think we are doing? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(6), 687–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2010.483275

- Bryant, S. M., & Albring, S. M. (2006). Effective team building: Gardens for accounting educators. Issues in Accounting Education, 21(3), 241–265. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace.2006.21.3.241

- Burke, A. (2011). Group work: How to use groups effectively. The Journal of Effective Teaching, 11(2), 87–95.

- Chapman, K. J., Meuter, M., Toy, D., & Wright, L. (2006). Can’t we pick our own groups? The influence of group selection method on group dynamics and outcomes. Journal of Management Education, 30(4), 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562905284872

- Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand (CA ANZ). (2023). CA capability Model booklet. https://www.charteredaccountantsanz.com/learning-and-events/learning/capability-model

- Christensen, J., Harrison, J. L., Hollindale, J., & Wood, K. (2019). Implementing team-based learning (TBL) in accounting courses. Accounting Education, 28(2), 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2018.1535986

- Clinton, B. D., & Kohlmeyer, J. M. (2005). The effects of group quizzes on performance and motivation to learn: Two experiments in cooperative learning. Journal of Accounting Education, 23(2), 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2005.06.001

- Davies, W. (2009). Groupwork as a form of assessment: Common problems and recommended solutions. Higher Education, 58(4), 563–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9216-y

- De Bruyn, M. (2023). Emotional intelligence capabilities that can improve the non-technical skills of accounting students. Accounting Education, 32(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2022.2032221

- De Villiers, R. (2010). The incorporation of soft skills into accounting curricula: Preparing accounting graduates for their unpredictable futures. Meditari Accountancy Research, 18(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/10222529201000007

- Delaney, D. A., Fletcher, M., Cameron, C., & Bodle, K. (2013). Online self and peer assessment of teamwork in accounting education. Accounting Research Journal, 26(3), 222–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-04-2012-0029

- Dolce, V., Emanuel, F., Cisi, M., & Ghislieri, C. (2020). The soft skills of accounting graduates: Perceptions versus expectations. Accounting Education, 29(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2019.1697937

- Donelan, H., & Kear, K. (2023). Online group projects in higher education: persistent challenges and implications for practice. Journal of Computing in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-023-09360-7

- Doran, J., Healy, M., McCutcheon, M., & O’Callaghan, S. (2011). Adapting case-based teaching to large class settings: An action research approach. Accounting Education, 20(3), 245–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2011.583742

- Edmond, T., & Tiggeman, T. (2009). Accounting experiences in collaborative teaching. American Journal of Business Education, 2(7), 97–100.

- Freeman, L., & Greenacre, L. (2011). An examination of socially destructive behaviors in group work. Journal of Marketing Education, 33(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475310389150

- Friedman, D., Karniel, Y., & Lavie-Dinur, A. (2009). Comparing group discussion in virtual and physical environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 18(4), 286–293. https://doi.org/10.1162/pres.18.4.286

- Gammie, E., & Matson, M. (2007). Group assessment at final degree level: An evaluation. Accounting Education, 16(2), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639280701234609

- Goñi, J., Cortázar, C., Alvares, D., Donoso, U., & Miranda, C. (2020). Is teamwork different online versus face-to-face? A case in Engineering Education. Sustainability, 12(24), 10444–10418. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410444

- Healy, M., Doran, J., & McCutcheon, M. (2018). Cooperative learning outcomes from cumulative experiences of group work: Differences in student perceptions. Accounting Education, 27(3), 286–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2018.1476893

- Helliar, C. (2013). The global challenge for accounting education. Accounting Education, 22(6), 510–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2013.847319

- Hillyard, C., Gillespie, D., & Littig, P. (2010). University students’ attitudes about learning in small groups after frequent participation. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787409355867

- Hoegl, M. (2005). Smaller teams – better teamwork: How to keep project teams small. Business Horizons, 48(3), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2004.10.013

- Howcroft, D. (2017). Graduates’ vocational skills for the management accountancy profession: Exploring the accounting education expectation-performance gap. Accounting Education, 26(5–6), 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2017.1361846

- Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW). (2020). ACA syllabus, skills development and technical knowledge grids. For Exams in 2022. https://www.icaew.com/-/media/corporate/files/learning-and-development/aca-syllabus/2022/2022-aca-syllabus-skills-and-technical-knowledge-grids-may-2020.ashx

- International Education Standard 3. (2019). Initial professional development – professional skills (revised). https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/IAESB-IES-3-Professional-skills.pdf

- Jackling, B., & De Lange, P. (2009). Do accounting graduates’ skills meet the expectations of employers? A matter of convergence or divergence. Accounting Education, 18(4–5), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639280902719341

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2009). An Educational Psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educational Researcher, 38(5), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09339057

- Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (1999). The wisdom of teams: Creating the high-performance organisation. HarperCollins Publishers.

- King, A. Z., & King, H. (2021). Developing team skills in accounting students: A complete curriculum. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 21(7), 116–146. https://doi.org/10.33423/jhetp.v21i7.4491

- Lancaster, K., & Strand, C. (2001). Using the team-learning model in a managerial accounting class: An experiment in cooperative learning. Issues in Accounting Education, 16(4), 549–567. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace.2001.16.4.549

- Lee, H., Kim, H., & Byun, H. (2017). Are high achievers successful in collaborative learning? An explorative study of college students’ learning approaches in team project-based learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(5), 418–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2015.1105754

- Low, M., Samkin, G., & Liu, C. (2013). Accounting education and the provision of soft skills: Implications of the recent NZICA CA academic requirement changes. E-Journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching, 7(1), 1–33.

- Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. E., & Zaccaro, S. J. (2001). A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Academic Management Review, 26(3), 356–376. https://doi.org/10.2307/259182

- Mhlongo, F. (2020). Pervasive skills and accounting graduates’ employment prospects: Are South African employers calling for pervasive skills when recruiting? Journal of Education, 80(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i80a03

- Missingham, D., & Matthews, R. (2014). A democratic and student-centred approach to facilitating teamwork learning among first-year engineering students: A learning and teaching case study. European Journal of Engineering Education, 39(4), 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2014.881321

- Oosthuizen, H., De Lange, P., Wilmshurst, T., & Beatson, N. (2021). Teamwork in the accounting curriculum: Stakeholder expectations, accounting students’ value proposition, and instructors’ guidance. Accounting Education, 30(2), 131–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2020.1858321

- Opdecam, E., & Everaert, P. (2018). Seven disagreements about cooperative learning. Accounting Education, 27(3), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2018.1477056

- Paisey, C., & Paisey, N. J. (2007). Balancing the vocational and academic dimensions of accounting education: The case for a core curriculum. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 59(1), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820601145705

- Rezaei, A. (2017). Features of successful group work in online and physical courses. The Journal of Effective Teaching, 17(3), 5–22.

- Riebe, L., Girardi, A., & Whitsed, C. (2016). A systematic literature review of teamwork pedagogy in higher education. Small Group Research,, 47(6), 619–664. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496416665221

- SAICA. (2021). Competency Framework 2021. https://www.saica.org.za/initiatives/competency-framework/ca2025

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Schmutz, J. B., Meier, L. L., & Manser, T. (2019). How effective is teamwork really? The relationship between teamwork and performance in healthcare teams: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 9(9), e028280–16. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028280

- Smith, G. G., Sorensen, C., Gump, A., Heindel, A. J., Caris, M., & Martinez, C. D. (2011). Overcoming student resistance to group work: Online versus face-to-face. The Internet and Higher Education, 14(2), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.09.005

- Sridharan, B., Muttakin, M. B., & Mihret, D. G. (2018). Students’ perceptions of peer assessment effectiveness: An explorative study. Accounting Education, 27(3), 259–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2018.1476894

- Steenkamp, G., & Goosen, R. (2023). Enhancing students’ relational acumen capacity through a reflective self-assessment workshop on behavioural styles. Accounting Education, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2023.2267519

- Succi, C., & Canovi, M. (2020). Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: Comparing students and employers’ perceptions. Studies in Higher Education, 45(9), 1834–1847. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420

- Tan, L. M., & Laswad, F. (2018). Professional skills required of accountants: What do job advertisements tell us? Accounting Education, 27(4), 403–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2018.1490189

- Tempone, I., Kavanagh, M., Segal, N., Hancock, P., Howieson, B., & Kent, J. (2012). Desirable generic attributes for accounting graduates into the twenty-first century. Accounting Research Journal, 25(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/10309611211244519

- Tseng, T. W., & Yeh, H. T. (2013). Team members’ perceptions of online teamwork learning experiences and building teamwork trust: A qualitative study. Computers & Education, 63, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.013

- Tsiligiris, V., & Bowyer, D. (2021). Exploring the impact of 4IR on skills and personal qualities for future accountants: A proposed conceptual framework for university accounting education. Accounting Education, 30(6), 621–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2021.1938616

- Vanhove, A., Opdecam, E., & Haerens, L. (2023). Fostering social skills in the Flemish secondary accounting education: Perceived challenges, opportunities, and future directions. Accounting Education. Early online. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2023.2208106

- Viviers, H. A. (2016). Taking stock of South African accounting students’ pervasive skills development: Are we making progress? South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(2), 242–263. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-2-645

- Wye, C.-K., & Lim, Y. M. (2009). Perception differential between employers and undergraduates on the importance of employability skills. International Education Studies, 2(1), 95–105.