ABSTRACT

The accessibility of legal support for private family matters has been devastated by decades of reform. At the time of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, legal advice supposedly remained available to support those in family mediation via the ‘Help with Family Mediation’ scheme. However, initial evidence suggests that lawyers rarely engage in the scheme because of a lack of financial incentives. Statistics on Help with Family Mediation are released every financial quarter, but have not been properly scrutinised in academic commentary or public policy. This article outlines findings from the first quantitative study on Help with Family Mediation. The study confirms that the scheme remains largely unavailable and has declined in use since 2016. It reveals that the scheme has dealt with a higher proportion of finance-related disputes over time, with more cases also resulting in a financial benefit. Statistical analysis then confirms a relationship between the type of dispute and whether an agreement is reached in mediation. The article concludes by highlighting the implications of these findings beyond their relevance to lawyers. Altogether, the study demonstrates a need for further research on family justice professionals, as well as family justice data, more widely.

Introduction

April 2023 marked a decade since the implementation of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO). By removing legal aid for the majority of private family matters in court and retaining funding for cases heard in family mediation, LASPO had a profound impact on contemporary family justice. The push for private ordering and individual responsibility that underpinned the reforms, both masked in a rhetoric of autonomy, had been unfolding for some time, paving the way for a family law system premised on individualised rather than adjudicatory justice (Diduck Citation2016, p. 145, Barlow et al. Citation2017, p. 67). This trajectory is only likely to continue well into the 2020s, with recent proposals to make family mediation compulsory for most private family cases being published by the Ministry of Justice (Citation2023c).

A major concern with the promotion of out-of-court family dispute resolution, particularly mediation, is the lack of legal oversight. Family mediators are bound to act as facilitative neutrals. The concept of mediator neutrality is inherent to the role of the mediator, and prohibits her from intervening. Mediator neutrality also operates as a form of quality assurance in the sense that the concept determines whether a mediator’s actions were justified (Rifkin et al. Citation1991, p. 153). The mediator profession is consequently confined to assisting discussions and providing information, with more evaluative support being provided by the parties’ respective lawyers (Walker et al. Citation1994, p. 135). While lawyers are said to provide a crucial form of scrutiny over mediated settlements, the accessibility of traditional legal assistance has been eroded by the LASPO reforms. As a result, there is now a noticeable ‘advice gap’ for those unable to afford legal advice (Barlow et al. Citation2017, p. 82).

Help with Family Mediation (HwFM) supposedly addresses this gap for legal aid recipients. Introduced in 2013, the scheme enables those who receive legal aid for family mediation to receive additional funding for legal advice in support of their mediation sessions. Solicitors can also be paid to write a consent order for financial or property matters under the scheme. While the premise behind HwFM certainly holds potential, the scheme’s effectiveness is heavily questioned. The Family Mediation Task Force (Citation2014, para 54) reported that only 30 claims for HwFM were made in the first year of the scheme, despite up to 16,000 individuals qualifying for assistance. Some academic commentary has mentioned HwFM in the years after LASPO (Hitchings and Miles Citation2016, pp. 177–178, Barlow et al. Citation2017, p. 159), though a proper examination of the scheme has yet to take place. This raises an important question: have HwFM numbers improved over time? As attention shifts to the second decade of LASPO and how to improve family justice going forward, the different mechanisms underpinning these reforms must be revisited.

This article investigates the operation of HwFM since its inception in 2013. It does so by outlining findings from the first quantitative study on published HwFM statistics. Despite the dataset’s limitations, this study provides an original and important snapshot of the English and Welsh family law landscape after LASPO. It is also one of few small-scale quantitative studies on the family justice system, potentially serving as a basis for further data-driven research (Jay et al. Citation2017, p. 62, Broadhurst et al. Citation2021, p. 250).

The article first sets out family mediation’s position after LASPO and identifies a growing concern that mediators cannot adequately cater to an increasingly complex client base with little access to lawyers. Section two examines the HwFM scheme and the reasons behind its low use, with particular reference to the lack of monetary incentives for lawyers. Section three then outlines the study’s methods. General findings are discussed in section four, covering the use of solicitor-provided HwFM over time, the types of cases heard under the scheme, and the recorded outcomes for those cases. As expected, the study reveals that solicitor-provided HwFM remains incredibly inaccessible ten years after LASPO’s enactment. It also identifies a shift in the types of cases and outcomes being assisted through HwFM, with more financial cases and financial outcomes being recorded over time. In light of this discovery, section five comprises a statistical analysis, confirming that financial disputes under the scheme are more likely to result in a financial or non-financial benefit. The final section highlights the implications of the study and identifies a growing need for further work on family justice professionals – beyond lawyers – as well as more robust family justice data and quantitative research.

Family mediation after LASPO

Since 2013, legal aid for family mediation has been provided in three ways (Ministry of Justice Citation2019, para 606). First, a party can receive funding for an initial Mediation, Information and Assessment Meeting (MIAM). Second, legal aid is available for family mediation sessions. Finally, legal aid recipients may receive additional support through HwFM. This third element will be detailed in section two. Prior to that investigation, it is important to consider the position of legal aid family mediation after LASPO and the broader apprehensions surrounding the decline of traditional legal advice.

Despite a predicted extra 10,000 mediation cases each year, the number of MIAMs and family mediation starts under legal aid dropped drastically in the year after LASPO’s enactment (Ministry of Justice and Legal Aid Agency Citation2014, para 10). The number of MIAMs fell 56% points from 30,665 to 13,390, and mediation starts dropped 38% points from 13,609 to 8,438 (Ministry of Justice Citation2023a, tables 7.1–7.2). Figures continued to decrease, reaching a low of 11,577 MIAMs and 7,320 mediation starts in 2022–23. Family mediation intake for privately funded matters was also predicted to have declined as fewer individuals were being referred to the process (Bloch et al. Citation2014, pp. 12–13). Despite decades of policy support, family mediation has struggled to catch the public’s attention.

The decline in mediation numbers is attributed to the withdrawal of lawyers from the family justice system. Parties were traditionally referred to family mediation after being screened by their lawyer. Some parties self-referred into mediation, although this decision was usually informed by a previous meeting with a solicitor (Walker et al. Citation1994, p. 30). By comparison, a survey of divorcing or separating couples from 1996 to 2011 found that just over half of the sample obtained legal advice (Barlow et al. Citation2017, p. 71). With solicitors no longer the first port of call for many family law disputants after LASPO, referrals to family mediation have plummeted (Bloch et al. Citation2014, pp. 12–13). In the recent Fair Shares project, 44% of divorcees said they did not receive support from a lawyer or legal service company (Hitchings et al. Citation2023, p. 105).Footnote1 At the same time, mediators are increasingly taking on cases that would have traditionally been deemed unsuitable for family mediation, mainly due to a lack of realistic alternatives in the post-LASPO climate (Barlow and Hunter Citation2020, p. 15, Blakey Citation2020, pp. 57–58).

Evidence suggests that mediators are taking on a more active role in light of this rising heterogeneity (Maclean and Eekelaar Citation2016, pp. 123–125, Hitchings and Miles Citation2016, pp. 183–185, Blakey Citation2020, pp. 71–73). These actions are often described in the mediation literature as ‘evaluative’, meaning the mediator evaluates the issues in a dispute and even directs the outcome in extreme instances (Riskin Citation1996, pp. 23–24). However, mediator evaluation is regularly criticised on two grounds. First, family mediators are supposedly bound by the sacrosanct concept of mediator neutrality. An action deemed too interventionist or evaluative is therefore seen as an unjustifiably radical departure from the mediator’s traditional role. Second, even if family mediators were allowed to be more evaluative, doubts exist as to whether mediators can, and should, provide a service analogous to legal advice. While the number of lawyer mediators has increased over the last few decades (Blakey Citation2023, p. 144), the legal training required to obtain accredited family mediator status in England and Wales is minimal.Footnote2 These issues give rise to further concerns around the limited regulation of family mediation, a service that currently sits outside the scope of the Legal Services Act 2007.

The use of lawyers is subsequently regarded as crucial to ensuring the shadow of the law over mediated negotiations (Mnookin and Kornhauser Citation1979). Hitchings and Miles (Citation2016, p. 176) recognise that the shadow of the law is particularly important in a discretionary family law system for post-separation arrangements where parties struggle to understand their legal entitlements without professional support. Unfortunately, the shadow of the law has lost much of its strength following LASPO and the subsequent withdrawal of lawyer support. In the words of Hunter et al. (Citation2017, p. 244): ‘access to law has been diminished, if not entirely negated’. This sentiment is particularly true for those who privately pay for mediation and can no longer access affordable support through a solicitor. However, the picture is even more complex for legal aid recipients with access to legal support through HwFM.

The help with family mediation scheme

HwFM is a form of ‘Legal Help’ under legal aid, introduced by the Civil Legal Aid (Procedure) Regulations 2012.Footnote3 Regulation 8 provides the following definition:

Help with family mediation means the provision of any of the following civil legal services, in relation to a family dispute—

civil legal services provided in relation to family mediation; or

civil legal services provided in relation to the issuing of proceedings to obtain a consent order following the settlement of the dispute following family mediation.’

HwFM therefore comprises two services. First, HwFM includes services ‘in relation to family mediation’. This includes the use of legal advice, as well as the Specialist Telephone Advice Service (explained in section three). Second, HwFM covers the drafting or issuing of a consent order when an agreement has been reached in mediation. The Ministry of Justice (Citation2019, para 607) summarises these two activities in their post-implementation review of LASPO:

‘Regulations under LASPO created a new form of service called “help with family mediation” where eligible clients participating in family mediation are entitled to legal advice to support the mediation process. It also supports the drafting and issuing of proceedings to obtain a court order where financial or property matters are resolved through mediation’.

The Civil Legal Aid (Remuneration) Regulations 2013 outlines the respective fees for each HwFM service.Footnote4 Service providers receive £150 for providing advice on any mediated matter. Hitchings and Miles (Citation2016, p. 177) note that this payment was based on an analysis of previous legal aid data concerning the standard amount of time a lawyer would spend assisting mediation. By contrast, mediators receive different levels of pay for legal aid work depending on the type of dispute.Footnote5 HwFM providers can also receive £200 for drafting or issuing a consent order. However, this reimbursement is only available when dealing with financial or property matters. At present, similar funding is not available for child-related disputes.

These low monetary incentives are cited as the main reason behind HwFM’s low uptake in the early to mid-2010s. The Family Mediation Task Force (Citation2014, para 56) initially reported that very few solicitors were taking work under the scheme because the rates were ‘too low’.Footnote6 The group subsequently proposed to increase the fixed fee for drafting a consent order from £200 to £300 (Family Mediation Task Force Citation2014, para 58). However, this proposal was rejected by the Ministry of Justice. Simon Hughes (Citation2014, p. 3), the Minister of State for Justice and Civil Liberties from 2013 to 2015, acknowledged that lawyers had called for increased payments under HwFM, but argued that there was no ‘sufficient compelling evidence that making such changes would increase the take-up of mediation’. Hitchings and Miles (Citation2016, p. 179) connect Hughes’ reasoning to a neoliberal agenda, one which values legal reform in terms of whether it improves mediation intake rather than the quality of mediated outcomes. Hughes (Citation2014, p. 3) was more positive about the Family Mediation Task Force’s (Citation2014, para 61) proposal to waive the need for solicitors to assess a party’s eligibility for legal aid if it had already been confirmed by a mediator. Nonetheless, it is unclear if this reform was ever implemented due to an absence of published information on HwFM. What remains certain is that, without improvement, the fees under HwFM will continue to be a ‘strong disincentive’ for lawyers (Barlow et al. Citation2017, p. 159). This limitation has been acknowledged more recently, with the Ministry of Justice (Citation2019, para 616) admitting there was ‘a lack of incentive’ for lawyers to engage with HwFM.

It therefore appears that access to the law through a lawyer also diminished for legal aid recipients after LASPO. However, ten years have passed since HwFM was first introduced. No further research on the scheme has been published in this decade. Yet in order to determine whether a service truly maintains or hinders access to justice, the relevant data must be properly analysed (Byrom Citation2019, p. 2). Despite its potential value, HwFM remains understudied. The evidence base surrounding HwFM is, ultimately, limited and incomplete.

Further work into HwFM is also needed where policy papers have presented contradictory or incomplete information on the scheme. In the post-implementation review of LASPO, the Ministry of Justice (Citation2019, para 682) reported that HwFM was initially expected to cost £8 m per year. However, the scheme only cost £15,000 ‘in the year immediately after LASPO’, rising to £73,000 in 2015–16. These findings contradict an earlier paper by the Family Mediation Task Force (Citation2014, para 54), which claimed that only £6,000 in legal aid expenditure had been spent on the scheme. The reason for these different figures is unclear, though it may be linked to a lack of data when HwFM was first introduced.Footnote7 Unfortunately, the post-implementation review of LASPO provides no further information on HwFM. One paragraph directs readers towards a figure to show that ‘the actual cost [of HwFM] has been much lower’ than expected, though the referenced table only covers MIAMs and mediation statistics (Ministry of Justice Citation2019, p. 159). Policymakers appear to have forgotten about HwFM – a possible foreshadowing of the scheme’s trajectory.

Methods: analysing the HwFM data

The aim of the study was to investigate the use of lawyers under HwFM. It furthermore sought to understand which factors, if any, contributed to a certain outcome being recorded for cases under lawyer-provided HwFM. The study’s findings primarily relate to legal aid family mediation, though remain valuable in understanding the accessibility and use of lawyer support in private family matters more widely.

The Ministry of Justice (Citation2023b) publishes legal aid statistics every quarter. These datasets, including the one analysed for this study, are publicly available. Interested persons will usually track the use of legal aid through written bulletins or published tables. These publications include information on legal aid MIAMs and legal aid family mediations, both in terms of uptake and cost. The number of mediations resulting in full or partial agreement is also logged. However, neither the bulletin nor the tables cover the HwFM scheme.

The HwFM data analysed in this study was sourced from the Ministry of Justice’s ‘detailed civil data’ spreadsheet.Footnote8 All datasets covered in this spreadsheet list the financial year, financial quarter and scheme of a group of cases.Footnote9 The statistics on HwFM can be viewed more easily through a visualisation tool published by the Ministry of Justice and Legal Aid Agency (Citation2023).Footnote10 Through the tool, users can view the number of HwFM cases each year, as well as the overall cost of the scheme. Users can also look at the use of HwFM according to its provider, as discussed below. It is hoped that this webpage will encourage further scrutiny of the various legal aid schemes, including HwFM. Nonetheless, this article remains a crucial contribution to the literature as it is the first publication to scrutinise the HwFM data. The study also builds on its general findings through a statistical analysis which could not be performed by looking at the visualisation tool alone.

The January to March 2023 data file was selected for analysis as it includes data for all financial quarters from 2013–14 to 2022–23, covering ten years of HwFM. 549 rows of data were listed under HwFM. However, these rows do not represent individual cases. Rather, cases are grouped under the spreadsheet according to several variables: financial year (FIN_YR), financial quarter (FIN_QTR), provider (SUB_CAT3), dispute outcome (SUB_CAT4) and dispute type (CODE_2).Footnote11 The number of cases is recorded under a separate variable (or column), labelled VOL. The combined cost of those cases is then listed under the TOTAL variable.Footnote12 An example of how HwFM cases are logged in the spreadsheet is provided in Appendix 1.

In terms of data selection, 1,876 individual cases were logged under HwFM. Three HwFM providers were listed under the SUB_CAT3 variable: Not for Profit (n = 4), Specialist Telephone Advice Service (n = 280), and Solicitor (n = 1,592). Only four cases, all logged in 2014–15 or 2015–16, were assisted by Not for Profit organisations. Given the small sample size, as well as the risk of identification for these legal aid users and their HwFM providers, these cases were excluded from the sample. Turning to the next HwFM provider, the Specialist Telephone Advice Service is a helpline for legal aid recipients. After an initial meeting, users are forwarded to ‘specialist providers’ (GOV.UK Citation2023b). Specialist providers then perform two tasks. First, specialist providers can assess the scope and eligibility of a claim, in effect determining whether an individual can receive funded support. Second, specialist providers can advise on a number of legal areas, including family law. The Specialist Telephone Advice Service carries out both tasks under HwFM, though the provision of advice is rare. Within the dataset, 241 entries concerned the scope and eligibility of a case, whereas 39 involved advice. As the purpose of this study was to understand the availability of legal advice and support through lawyers under the HwFM scheme, the cases supported by the Specialist Telephone Advice Service were also excluded from the sample. The selected sample for the study was therefore 1,592 cases, all of which were logged under the ‘Solicitor’ provider.

Turning to analysis, the HwFM data was first re-entered in Excel so that each row represented an individual case.Footnote13 The data was then analysed via SPSS. General findings, covered in section four, were uncovered through descriptive statistics. After performing various cross-tabulations, statistical analysis was conducted through chi-square tests and a logistic regression model.Footnote14 Unfortunately, the small number of variables under the dataset meant that the statistical analysis was considerably limited in terms of what could be deducted. This shortcoming will be revisited when considering the implications of the study.

Findings: HwFM ten years on

The study considered the use of solicitor-provided HwFM since the scheme’s inception in April 2013. It also examined the types of cases supported by solicitors obtaining funding through HwFM, as well as the outcomes of these disputes. These inquiries will be considered in order.

Overall use of solicitor-provided HwFM

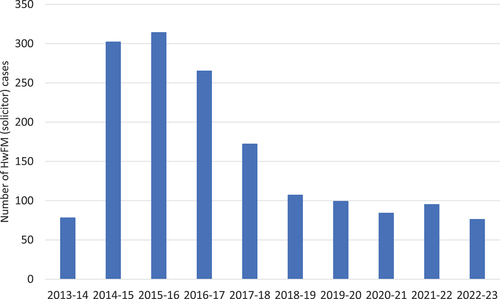

As mentioned in section three, there were 1,592 HwFM cases from 2013–14 to 2022–23 where a solicitor advised a party or supported the drafting or issuing of a consent order. 78 solicitor-provided cases were logged in 2013–14. While this number is low, it was an improvement from the 30 claims originally cited by the Family Mediation Task Force (Citation2014, para 54). The number of cases increased to 302 in 2014–15 and 314 in 2015–16, though numbers declined thereafter (). Recent statistics showed that there were 76 solicitor-provided HwFM cases in 2022–23, two fewer than when the scheme began in 2013–14. As a whole, solicitor-provided HwFM cases were equally distributed among the four financial quarters, with percentages ranging from 23.1 to 26.8%.

By comparison, there were 75,769 legal aid family mediation starts in the same ten-year period (Ministry of Justice Citation2023a, table 7.2). It therefore appears that only 2.1% of legal aid family mediation starts from 2013–14 to 2022–23 involved solicitor-provided HwFM (). This number is surprisingly low, especially when it is recognised that family mediation uptake is generally considered to be poor. The proportion of mediation starts involving solicitor-provided HwFM has even decreased over time, dropping from percentages ranging between 3.5 to 3.7% between 2014–15 to 2016–17 to a mere 1.0% by 2022–23.

Table 1. Number of family mediation starts and HwFM (solicitor-provided) cases under legal aid.

HwFM figures can also be compared to the total number of solicitor-supported private family matters receiving legal aid under Legal Help (). Including HwFM numbers, there were 193,502 logged cases from 2013–14 to 2022–23. By comparison, there were 1,592 solicitor-provided HwFM cases in the same period. HwFM, therefore, has not even accounted for one percent of solicitors’ Legal Help work for private family matters since LASPO’s implementation.

Table 2. Number of private family matters receiving legal help through a solicitor and HwFM (solicitor-provided) cases under legal aid.

Thus, the key finding from the study was that HwFM intake was much lower than hoped in the ten years after LASPO’s enactment. While these figures were somewhat of an improvement compared to more pessimistic assessments in the past, the use of solicitor-provided HwFM remained sparse when considered against general legal aid numbers. Regrettably, HwFM has failed as a scheme. Unless drastic measures are taken to improve its accessibility, HwFM shows little to no promise going forward.

The types of cases supported by solicitors through HwFM

Three types of cases supported by solicitor-provided HwFM cases are listed under the CODE_2 variable:

FMEF (Finance)

FMEC (Children)

FMEA (All issues)

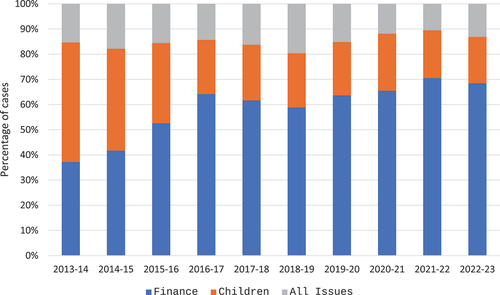

These values reflect the standard categorisation of disputes heard in family mediation. Looking at solicitor-provided HwFM, over half (n = 896) of cases involved financial disputes, a quarter (n = 449) children-related disputes, and 15% (n = 247) all issues. provides a breakdown of dispute type by year.

Table 3. Number of solicitor-provided HwFM cases by dispute type and year.

The profile of cases accessing solicitor-provided HwFM has shifted over time, as visualised in . When the scheme began in 2013–14, 47.4% (n = 37) of solicitor-provided HwFM related to children’s matters. 37.2% involved a financial matter (n = 29), and 15.4% (n = 12) all issues. Financial matters became the most common type of dispute from 2014–15, accounting for over half of solicitor-provided HwFM from 2015–16. The proportion of financial matters reached a high of 70.5% (n = 67) in 2021–22, the same year that cases concerning all issues fell to a low of 10.5% (n = 10). The proportion of child-related cases in the scheme saw the largest decline, dropping every year except for 2016–17 and 2020–21. In 2022–23, 68.4% (n = 52) of solicitors’ work concerned financial matters, 18.4% (n = 14) children’s matters, and 13.2% (n = 10) all issues.

The prevalence of financial disputes within the dataset could stem from the fact that solicitors only receive payment for drafting or issuing a consent order that relates to a financial (or property) matter. It may be that most cases logged under solicitor-provided HwFM concern the drafting or issuing of consent orders, rather than the provision of advice. Unfortunately, this hypothesis cannot be confirmed as the Ministry of Justice does not release data on the type of HwFM work carried out by solicitors. However, a comparison of HwFM figures and legal aid family mediation starts reveals that the HwFM scheme is disproportionately used in financial disputes. According to the Ministry of Justice and Legal Aid Agency’s (Citation2023) visualisation tool, there were 75,769 mediation starts from 2013–14 to 2022–23. Two-thirds (n = 50,752) of those cases involved a child-related dispute, and over a tenth (n = 10,323) involved a financial matter. These proportions are a significant juxtaposition to the HwFM scheme where over half of all solicitor-provided cases concerned financial matters. If HwFM deals with a higher proportion of financial matters compared to legal aid mediation in general, this may mean that a large amount of the scheme is funding the drafting or issuing of consent orders. Unfortunately, this hypothesis cannot be confirmed without further data.

Recorded outcomes for solicitor-provided HwFM

Five outcomes for solicitor-provided HwFM cases are listed under the SUB_CAT4 (dispute outcome) variableFootnote15:

Financial benefit;

Non-financial benefit;

No recorded benefit;

Outcome not known or client ceased to give instruction;

Proceeded under other civil funding.

27.4% (n = 436) of all solicitor-provided HwFM cases received a financial benefit (). 31.6% (n = 503) were listed under non-financial benefit, and 28.0% (n = 445) as no recorded benefit. A minority of cases had an unknown outcome (n = 169) or proceeded under other civil funding (n = 39).

Table 4. Recorded outcomes of all solicitor-provided HwFM from 2013 to 2023.

Where the profile of cases under solicitor-provided HwFM had changed over time, it was no surprise that their outcomes had also shifted (). For the first three years of HwFM, the largest proportion of solicitor-provided cases obtained a non-financial benefit. The second most common outcome over this period was no recorded benefit. To provide an example, 36.4% (n = 110) of cases in 2014–15 obtained a non-financial benefit. 28.5% (n = 86) of cases resulted in no recorded benefit. Yet in 2018–19, financial benefits made up the second largest proportion of cases at 31.8% (n = 34), with no recorded benefits dropping to 21.5% (n = 23). Financial benefits became the most common outcome in the dataset from 2019–20, reaching 35.7% (n = 30) in 2020–21. In the same year, the proportion of non-financial benefits dropped to 22.6% (n = 19).

Table 5. Recorded outcomes of solicitor-provided HwFM by year.

This pattern became even more pronounced in 2022–23, with the largest proportion of solicitor-provided HwFM cases – nearly half – receiving a financial benefit (n = 37). Just under a tenth (n = 7) cases received a non-financial benefit, whereas two-tenths (n = 16) had no recorded benefit. The reason behind the sharp rise in the proportion of financial benefits is unclear, prompting a need to revisit the dataset once new legal aid statistics are published.

Interestingly, only the first and second recorded outcomes – financial benefit and non-financial benefit – indicate that a full or partial settlement was reached in family mediation. Benefits can therefore be grouped into two categories: recorded (financial or non-financial) benefit, and no recorded benefit. From 2013–14 to 2022–23, 939 cases resulted in a financial or non-financial benefit. This figure suggests a settlement rate of about three-fifths for solicitor-provided HwFM, though some cases with no listed benefit may have reached a settlement in additional mediation sessions funded outside the legal aid scheme. The lowest record of financial or non-financial benefits was in 2013–14 (n = 41; 52.6%), though the number and proportion of cases obtaining these outcomes increased (n = 174; 57.6%) the following financial year. The amount of financial or non-financial benefits peaked at 68.2% (n = 73) in 2018–19. However, this figure fell to 60.6% (n = 60) in 2019–20 and did not recover, dropping to 57.9% (n = 44) in 2022–23.

Statistical analysis: what factors are likely to lead to a recorded benefit?

A noteworthy trend in the data was that whilst the proportion of solicitor-provided HwFM cases resulting in a financial or non-financial benefit was relatively stable, these disputes increasingly involved financial matters over time. It was subsequently hypothesised that different factors, particularly dispute type, influenced whether a financial or non-financial benefit was obtained. Statistical analysis was conducted to explore this assumption.

The objective of the statistical analysis was to understand the influence of various variables on whether a financial or non-financial benefit was received. For this reason, a dummy variable (OUTCOME_NUM_BENEFIT) was created. The values ‘0’ and ‘1’ represented cases ending in no recorded benefit and a recorded benefit respectively. As mentioned towards the end of section 4.3, 939 cases resulted in a recorded benefit. This number comprises both financial and non-financial benefits. 653 cases did not result in a recorded benefit, including disputes where the outcome was unknown or it proceeded under other civil funding.

Independent variables can be added to a statistical model in order to understand their individual effects on a dependent variable. However, as cautioned in section three, very few variables were listed in the HwFM dataset. Three variables could be tested to see if they had a relationship with dispute outcome: dispute type; financial year; and financial quarter. Multicollinearity between the three variables was tested (). VIF values ranged between 1.003 and 1.021, demonstrating very minor correlation. All three variables were subsequently considered for the regression model.

Table 6. Multicollinearity results.

Dispute type was an obvious variable to investigate as the proportion of financial disputes logged under solicitor-provided HwFM had increased over time. and are cross-tabulations: the former compares dispute type and dispute outcome, whereas the latter compares dispute type and grouped dispute outcome. reveals that financial matters made up the largest proportion of all listed outcomes under solicitor-provided HwFM, with the exception of ‘Proceeded under other civil funding’.Footnote16 This tendency may be attributed to the fact that over half of solicitor-provided HwFM cases involved financial matters. However, shows that nearly two-thirds (n = 602) of cases with a recorded benefit involved a financial matter. The proportion of recorded benefits – whether that was financial or non-financial – being awarded to all issues and children’s matters was substantially lower: 14.0% (n = 131) and 21.9% (n = 206) respectively. This pattern alluded to a strong correlation between financial disputes and recorded outcomes within the data.

Table 7. Cross-tabulation of dispute type and dispute outcome.

Table 8. Cross-tabulation of dispute type and grouped dispute outcomes.

A chi-square test was performed to test the relationship between dispute type (CODE_2) and whether a financial or non-financial benefit was obtained (OUTCOME_NUMBER_BENEFIT). Based on the results (χ2 (df = 2, n = 1592) = 60.405; p < 0.001), there was a statistically significant relationship between the dispute type and whether a financial or non-financial benefit was received. A statistically significant relationship meant that the correlation between dispute type and recorded outcomes was unlikely to be down to chance; rather, it was highly probable that the former variable impacted the latter.

Chi-square tests were also run to determine if the financial year (FIN_YR) and financial quarter (FIN_QTR) variables should be included in the regression model. The results showed that there was no statistically significant relationship between financial year and recorded outcomes (χ2 (df = 9, n = 1592) = 6.281; p < 0.711). There was also no statistically significant relationship between financial quarter and recorded outcomes (χ2 (df = 3, n = 1592) = 1.542; p < 0.673). Both variables were consequently excluded from the model.

Thus, a simple logistic regression was run to test the relationship between dispute type and the recorded outcome. Child-related issues were selected as the reference category. The results of the regression model therefore demonstrated the difference in odds of a recorded benefit (financial or non-financial) being obtained when comparing financial or all issues disputes to children’s matters.Footnote17

The null model – with no predictors – correctly predicted 59.0% of cases. The predictive power of the statistical model, with dispute type as its predictor, was 2.3% points higher at 61.3%. Despite the increase in predictive power being very minor, the statistical model was a statistically significant improvement on the null model (p < 0.001). The independent variable had a significant effect on the dependent variable, though the statistical model only explained 5% of variance in the dispute outcome (R2 = 0.050). Thus, the model only captured a tiny fraction of the factors that influenced whether a benefit was obtained through solicitor-provided HwFM.

The results of the logistic regression model are reported in . The output shows that the odds of a recorded benefit for financial disputes were 141.5% higher than the odds for children disputes (Exp(B) = 2.415).Footnote18 The odds of a recorded benefit for all issues matters were 33.2% higher than the odds for children disputes (Exp(B) = 1.332). However, only the coefficient for financial disputes was statistically significant (p < 0.001). p = 0.71 for all issues matters, indicating that the odd ratio was not statistically significant.

Table 9. Coefficients for dispute type.

Discussion

The HwFM legal aid scheme had the potential to ensure access to legal advice for a large group of disputants who would otherwise struggle to afford legal support. However, this study shows that the use of solicitor-provided HwFM remains incredibly low a decade after the scheme began. Case numbers rose in 2014–15 and 2015–16, though this momentum was short-lived. With the exception of 2021–22, solicitor-provided HwFM numbers have fallen each year since 2016–17. The most recent statistics from 2022–23 suggest that the HwFM scheme has reverted back to its original uptake, with only 76 cases being logged that financial year. This is the primary finding from the study: HwFM is used by a minority of legal aid recipients, and is unlikely to see any improvement in relation to intake without broader changes to the provision of legal support.

The analysis also revealed a shift in the types of cases and outcomes under HwFM. Solicitor-provided HwFM is now mainly used for financial disputes, despite the fact that the majority of family mediation starts through legal aid concern children’s matters. Solicitor-supported HwFM has obtained relatively stable settlement rates, though the outcomes of those cases have increasingly involved financial benefits over time. A statistical analysis confirms a relationship between dispute type and the type of benefit recorded. Notwithstanding the lack of guidance on how to interpret the dataset, this means that financial disputes are statistically more likely to result in a full or partial agreement through mediation under HwFM. All issues disputes were also more likely than child-related matters to result in a recorded outcome, though this correlation was not statistically significant.

More broadly, this development confirms the importance of legal advice when dealing with financial matters, particularly when compared to children’s matters (and perhaps even disputes comprising both types of issues).Footnote19 In the Fair Shares project, Hitchings et al. (Citation2023, pp. 309–312) identified a correlation between the provision of legal advice and particular outcomes upon divorce. This relationship was particularly noticeable for female divorcees, who upon receiving legal advice were more likely to receive the family home, obtain more equity following the sale of that home, or receive ongoing financial support from their ex-partner. The present study does not generate any data on the utility of the scheme to disputants according to gender. Nor does it indicate whether mediated agreements supplemented by legal advice are more likely to involve a split of the matrimonial assets. Nonetheless, it confirms an association between legal advice and the likelihood of an agreement being reached in financial disputes.

The findings of this study have implications for the ongoing discussions around the post-LASPO landscape. Regrettably, it confirms that legal advice has become massively inaccessible for legal aid recipients in family mediation. The failures of the HwFM scheme, moreover, shed light on the broader issue of diminishing access to traditional legal support and advice within the contemporary family justice system. Hitchings et al. (Citation2023, p. 367) summarise the problem: ‘many of those whom the law is intended to address are ignorant of the guidance and principles that it lays down because they experience barriers to accessing reliable advice and assistance about it’. It is imperative that further steps are taken to enhance the accessibility and availability, as well as the affordability, of legal services.

Of course, subsequent discussion and reform can focus on increasing the provision of traditional legal advice via lawyers. The dataset cannot explain why HwFM is unsuccessful in both its reach and operation. However, the low payment for HwFM work remains a likely disincentive, coupled with the declining number of law firms that engage with legal aid work (Wong and Cain Citation2019, p. 5). Research suggests that family lawyers tend to view legal aid work as heavily bureaucratic (Russell Citation2019, p. 159). Coupled with the large amount of paperwork for minimal financial reward, a payment of £150 or £200 is unlikely to offset these challenges. A parallel issue arises in the privately funded sphere where many parties can only afford to pay reduced rates which, in many instances, will not cover the costs incurred by legal practitioners.

Attention should be paid to the increasing innovation of legal services. Instead of providing more services through legal aid, many law firms have had to redesign their practices after LASPO (A Citation2017, p. 208). A prime example is the use of ‘unbundled services’. Through unbundling, legal assistance is limited to a select few tasks in order to reduce costs (Maclean and Eekelaar Citation2019, p. 43). Unbundling therefore enables access to lawyer-led advice for those who cannot afford to pay for support throughout their entire dispute. In fact, HwFM could be considered an unbundled service as a lawyer only provides support in relation to advice or a consent order. The present study, therefore, confirms the value of unbundled advice for financial or property matters heard in mediation.

However, it is important to recognise that unbundling is a relatively novel idea. In a recent survey by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (Citation2023), only a quarter of 114 law firms provided unbundled services. Two-thirds of respondents had not even heard of ‘unbundling’. While some solicitors may welcome unbundling, much of the profession has mixed feelings about the development or resists its introduction altogether (Russell Citation2019, p. 167). In addition to this problem, the lack of a proper monetary incentive means that HwFM (or a similar system of set fees for privately funded cases) is unlikely to become an attractive or realistic option for the profession. Other problems may impact the success of HwFM, including disputants’ awareness of the scheme and how far mediators actually promote its use. Unfortunately, it may be too late to save this legal aid scheme.

Increasing the monetary payment is unlikely to generate effective change when fewer individuals are accessing lawyers across the family law system (Hitchings et al. Citation2023, p. 137). Instead, many individuals now opt for support from other various family justice practitioners. As Smith and Hitchings (Citation2023, p. 660) argue, the withdrawal of legal advice by lawyers is only a small snapshot of the current family law landscape. Family disputes are often resolved through the assistance of non-lawyer services, a number of which are unregulated and sit outside the scope of the Legal Services Act 2007. However, discussion on this diverse group remains sparse.

This prompts the important question: if fewer cases in family mediation, and the family law system more broadly, are receiving legal support through a lawyer, what impact does this have on other practitioners? The mediator is of particular interest here as she may be the only family law professional involved in a dispute, particularly when the parties do not seek a binding consent order. Coupled with the rise of financial disputes without traditional legal oversight, the pressure on mediators to respond to an increasingly diverse client base has intensified (Hitchings and Miles Citation2016, Blakey Citation2020). There is thus a pressing need to understand how various practitioners are responding to the knock-on effects of LASPO.

Despite its failings, the HwFM scheme provides a valuable lesson for the design of future mediation procedures. If the majority of parties to financial disputes are going to have to demonstrate a ‘reasonable attempt’ at mediation before even being allowed to access court (Ministry of Justice Citation2023c), the likelihood of mediation resulting in an agreement – especially one that has longevity – may increase with the provision of legal support. This provision could be unbundled. It could be provided by a lawyer, or perhaps a non-lawyer service. There may even be room for mediators to provide more evaluative support and do more to strengthen the shadow of the law in negotiations. Nonetheless, it is clear that improvements to the mediation process itself are also necessary. Family mediation remains an unattractive option for many separating couples, with only 17% of divorcees in the Fair Shares survey attempting the process (Hitchings et al. Citation2023, p. 120). Even if mediation results in settlement, a concerning number of arrangements do not work in the long term.Footnote20 While it could be assumed that legal support leads to more workable and appropriate arrangements in mediation, thorough and substantiated evidence is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Furthermore, the support provided by a family justice professional – whether that is a lawyer, a mediator or another practitioner – is one of many factors that impact the progression of a dispute. This argument is reinforced by the present study in which the logistic regression model only accounted for a tiny amount of variance in whether solicitor-provided HwFM cases received a recorded benefit. Batagol and Brown (Citation2011, p. 217) argue that three additional matters influence the shadow of the law within family mediation: the parties’ unwillingness to use court; uncertainty around the law; and ideas of morality and fault. Barlow et al. (Citation2014, p. 25) further identify a number of dynamics associated with successful mediation, including the level of trust between the parties, their negotiating power and emotional readiness. None of these factors are captured within the HwFM dataset, and remain an important focus for future research.

The shortcomings within the dataset lead to a final implication regarding data collection and recording. This study is a crucial contribution to the family justice literature as it is one of few small-scale quantitative projects conducted post-LASPO. However, it could not provide a complete picture of the HwFM scheme because the dataset includes little to no information about each case. For example, it is unknown if one or both parties in the same case had a lawyer and whether any of that assistance was paid for privately. It also cannot be determined what exact types of financial or non-financial benefits were received, and by whom. HwFM provides funding for two services – giving advice and drafting or issuing a consent order – yet it is unclear which service was accessed in each case. Furthermore, the way expenditure is logged in the dataset does not correspond to individual cases, rendering it difficult to scrutinise the use of public funds on HwFM. It is not only the limited data on HwFM that is problematic, but also the way that data is presented.

These limitations, unfortunately, speak to a larger problem around the availability and accessibility of justice data. Byrom (Citation2019, paras 1.2–1.3), the Director of Research at the Legal Education Foundation from 2015 to 2023, highlights the dearth of data on the English and Welsh justice system, as well as the difficulties in both locating and analysing such data. She calls for improvements to ‘the data architecture around justice system processes’ which would, in turn, lead to an enhanced understanding of those legal systems. At present, there is a lack of statistical data within the family justice literature, particularly when compared to other areas like healthcare (Jay et al. Citation2017, p. 64). This problem is compounded by an absence of family justice scholars who undertake, or more specifically have the skillset to undertake, quantitative research. Broadhurst et al. (Citation2017, p. 37) subsequently call for a ‘concerted national effort’ to improve quantitative research skills within the socio-legal community.

Positive steps towards a more robust justice data system and research agenda have taken place in recent years. For example, the Nuffield Foundation’s Justice Observatory (Citation2023) and ESRC-funded Data Research UK (Citation2023) both seek to increase the use of data in informing research and public policy. However, these organisations remain dependent on funding from external sources, a prospect that may become increasingly challenging in an era of cuts and fiscal uncertainty.Footnote21 In 2023, the government established a Senior Data Government Panel to issue guidance on the use of justice data (GOV.UK Citation2023a). The announcement explained that the panel ‘will support the development of data in the wider justice system’, though the specifics of its operation have yet to be unveiled. The drive for improved data on the (family) justice system is crucial to furthering access to justice in the post-LASPO landscape, and must remain a priority for both academics and policymakers in the future.

Conclusion

This article has provided a critical insight into the HwFM scheme during its first ten years of operation. Unfortunately, it confirmed concerns that the scheme was inaccessible to the majority of legal aid recipients using family mediation. Through examining the data on solicitor-provided HwFM, the study revealed a transformation in the types of cases and outcomes under the scheme. Increasing the fees available for lawyers could improve the availability of HwFM for all different types of disputes, not just financial issues, though whether such reform would be implemented is questioned. Even if this change were enacted, it could come too late as law firms have increasingly focussed on different types of unbundled work.

While the study primarily provides a snapshot of legal aid family mediation after LASPO, its implications extend beyond the practice of family lawyers. If solicitors are not even accessible for family mediation users through a government-funded scheme, perhaps it is time to rethink the value of family mediators and other non-lawyer professionals in the contemporary landscape. There is a need to move beyond a ‘lawyer-centric’ perspective of family justice to one that actually embraces and scrutinises an increasingly diverse body of family justice professionals, including McKenzie Friends and online divorce services (Smith and Hitchings Citation2023, p. 675). This is not to suggest that contemporary family justice should exclude lawyers, but rather recognise that they are one of many practitioners who offer support to disputants in the post-LASPO landscape.

Investigating this plethora of services is only possible through enhanced data and research. Interest in justice data has increased in recent years, and efforts must be made to sustain this focus. The first step towards achieving this goal is to improve the availability and accessibility of justice data. However, it is equally important to encourage and support researchers in using quantitative research methods. These developments have the potential to forge stronger linkages between research and policy, potentially bridging the gap for many disputants who are currently unable to access anything close to legal support.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor James Harrison, Dr Charlotte Bendall and the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments on this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. This sample comprised 2,415 individuals who had divorced within five years prior to mid-2022, meaning all divorces happened after LASPO.

2. The overarching regulatory body for family mediation, the Family Mediation Council (Citation2022, pp. 20–21), stipulates that family mediators must be able to provide ‘information about family law and its processes’, as well as prepare ‘financial settlements that are capable of legal implementation and accord with current legislation’.

3. SI 2012/3098. The service succeeded ‘Help with Mediation’ which was listed in legal aid statistics as a form of ‘Civil Representation’. Unfortunately, the difference between ‘Help with Mediation’ and ‘Help with Family Mediation’ is unclear due to a lack of published information on the former scheme.

4. SI 2013/422, schedule 1, part 1.

5. Under schedule 1, part 4, family mediators receive £168 for sole mediation and £230 for co-mediation if only one session took place. The fees differ once multiple sessions have taken place or a settlement is reached. For example, a sole mediator receives £462 for multiple sessions on children’s matters, £588 on property or finance, and £756 on all issues.

6. Another reason was a belief amongst solicitors that HwFM work counted towards the number of matters that they could start as a legal aid provider (Family Mediation Task Force Citation2014, para 56).

7. The Ministry of Justice’s more recent figures are in line with the dataset used for this study. The ‘detailed civil legal aid’ dataset, outlined in section three, reveals that £15,634.50 was spent on HwFM in 2013–14 and £72,773.96 in 2015–16. Both figures include cases supported through the Specialist Telephone Advice Service.

8. The dataset also includes statistics on Help with Mediation, the scheme before HwFM. 12 entries, representing 15 separate cases, are logged under Help with Mediation from 2013–14 to 2017–18. These cases have been excluded from the current study as it is unclear how Help with Mediation differs to HwFM.

9. There are two schemes under the detailed civil data spreadsheet: ‘Civil Representation’ and ‘Legal Help’. All HwFM cases are logged under the latter.

10. There are numerous visualisation tools on this webpage. The relevant tool, covering all criminal and civil legal aid statistics, is titled ‘Legal Aid Statistics’.

11. The values for dispute outcome and dispute type are outlined in sections 4.2 and 4.3.

12. This study did not investigate the costs of individual cases as the value under the TOTAL variable was not always divided equally amongst the relevant cases. Nonetheless, further research could investigate the cost of the scheme over time, and the types of cases where more money was spent.

13. This enabled statistical analysis to be conducted later on.

14. Some variables were recoded for this analysis, as mentioned in section 5.

15. Cases supported by the Specialist Telephone Advice Service can also result in a ‘Determination’.

16. Interestingly, two-thirds (n = 26) of cases that proceeded under other civil funding involved a child-related matter or all issues. This suggests that most cases which do not progress through HwFM yet remain eligible for legal aid involve a child-related dispute.

17. Because SPSS automatically makes the first value the reference category, the dispute type variable was recoded. CODE_2 was recoded as DISPUTE_TYPE_CHILDFIRST. Child issues were coded as ‘1’, finance issues as ‘2’ and all issues as ‘3’.

18. Odds are calculated by subtracting 1 from the Exp(B) result and multiplying that by 100. For example, 2.415–1 = 1.415 × 100 = 141.5.

19. It is important that future research and commentary also considers the shadow of the law in children’s matters. Prior research suggests that child-related matters in family mediation are less centred on legal rights and norms (Barlow et al. Citation2017, p. 188).

20. In Fair Shares, 66% of full settlements reached in mediation did not work out as the divorcee expected (Hitchings et al. Citation2023, p. 321).

21. Both the Family Justice Observatory and Administrative Data Research UK have secured additional funding until 2026.

References

- A, B., 2017. Rising to the Post-LASPO Challenge: How Should Mediation Respond? Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 39 (2), 203–222. doi:10.1080/09649069.2017.1306348.

- Barlow, A., et al., 2014. Mapping Paths to Family Justice: Briefing Paper and Report on Key Findings. Exeter: University of Exeter.

- Barlow, A., et al., 2017. Mapping Paths to Family Justice: Resolving Family Justice in Neoliberal Times. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barlow, A. and Hunter, R., 2020. Reconstruction of Family Mediation in a Post-Justice World. In: M. Roberts and M.F. Moscati, eds. Family Mediation: Contemporary Issues. London: Bloomsbury Professional, 11–32.

- Batagol, B. and Brown, T., 2011. Bargaining in the Shadow of the Law: The Case of Family Mediation. Annandale: Themis Press.

- Blakey, R., 2020. Cracking the Code: The Role of Mediators and Flexibility Post-LASPO. Child and Family Law Quarterly, 32 (1), 53–74.

- Blakey, R., 2023. ‘Mediators Mediating themselves’: Tensions within the Family Mediator Profession. Legal Studies, 43 (1), 139–158. doi:10.1017/lst.2022.29.

- Bloch, A., et al., 2014. Mediation Information and Assessment Meetings (MIAMs) and Mediation in Private Family Law Disputes: Qualitative Research Findings. London: Ministry of Justice.

- Broadhurst, K., et al., 2017. Towards a Family Justice Observatory – a Scoping Study: Main Findings Report of the National Stakeholder Consultation [ online]. Lancaster: Lancaster University. Available from: http://wp.lancs.ac.uk/observatory-scoping-study/files/2017/08/National-Stakeholder-Consultation-Main-Findings-Report.pdf [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Broadhurst, K., et al., 2021. Scaling Up Research on Family Justice Using Large-Scale Administrative Data: An Invitation to the Socio-Legal Community. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 43 (3), 237–255. doi:10.1080/09649069.2021.1953856.

- Byrom, N., 2019. Digital Justice: HMCTS Data Strategy and Delivering Access to Justice. Guildford: Legal Education Foundation.

- Data Research UK, A., 2023. About ADR UK [ online]. Administrative Data Research UK. Available from: www.adruk.org/about-us/about-adr-uk [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Diduck, A., 2016. Autonomy and Family Justice. Child and Family Law Quarterly, 28 (2), 133–150.

- Family Mediation Council, 2022. FMC Manual of Professional Standards and Self-Regulatory Framework [online]. FMC. Available from: www.familymediationcouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/FMC-Manual-of-Professonal-Standards-Regulatory-Framework-v1.4.1-Updated-1-March-2022.pdf [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Family Mediation Task Force, 2014. Report of the Family Mediation Task Force. London: Ministry of Justice.

- GOV.UK, 2023a. Data Governance Panel Formed to Improve Use of Court and Tribunals Data [online]. GOV.UK. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/news/data-governance-panel-formed-to-improve-use-of-court-and-tribunals-data [accessed 4 January 2024].

- GOV.UK, 2023b. User Guide to Legal Aid Statistics in England and Wales [online]. GOV.UK. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/a-guide-to-legal-aid-statistics-in-england-and-wales/user-guide-to-legal-aid-statistics-in-england-and-wales [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Hitchings, E., et al., 2023. Fair Shares? Sorting Out Money and Property on Divorce. Bristol: University of Bristol.

- Hitchings, E. and Miles, J., 2016. Mediation, Financial Remedies, Information Provision and Legal Advice: The Post-LASPO Conundrum. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 38 (2), 175–195. doi:10.1080/09649069.2016.1156888.

- Hughes, S., 2014. Family Mediation Task Force Report [ online]. Ministry of Justice. Available from: www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/DOC017.PDF [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Hunter, R., et al. 2017. Access to What? LASPO and Mediation. In: A. Flynn and J. Hodgson, eds. Access to Justice and Legal Aid: Comparative Perspectives on Unmet Legal Need. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 239–254.

- Jay, M., et al., 2017. Who Cares for Children? Population Data for Family Justice Research [ online]. Lancaster: Lancaster University. Available from: http://wp.lancs.ac.uk/observatory-scoping-study/publications [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Justice Observatory, F., 2023. About [Online]. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. Available from: www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/about [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Maclean, M. and Eekelaar, J., 2016. Lawyers and Mediators: The Brave New World of Services for Separating Families. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- Maclean, M. and Eekelaar, J., 2019. After the Act: Access the Justice After LASPO. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- Ministry of Justice, 2019. Post-Implementation Review of Part 1 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO) CP 37.

- Ministry of Justice, 2023a. Legal Aid Statistics England and Wales Tables January to March 2023 [online]. GOV.UK. Available from: [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Ministry of Justice, 2023b. Legal Aid Statistics: January to March 2023 [online]. GOV.UK. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/legal-aid-statistics-january-to-march-2023 [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Ministry of Justice, 2023c. Supporting Earlier Resolution of Private Family Law Arrangements: A Consultation on Resolving Private Family Disputes Earlier Through Family Mediation CP 824.

- Ministry of Justice and Legal Aid Agency, 2014. Implementing Reforms to Civil Legal Aid. London: National Audit Office, HC 784.

- Ministry of Justice and Legal Aid Agency, 2023. Legal Aid Statistics [online]. GOV.UK. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/a-guide-to-legal-aid-statistics-in-england-and-wales/legal-aid-statistics-data-visualisation-tools [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Mnookin, R. and Kornhauser, L., 1979. Bargaining in the Shadow of the Law: The Case of Divorce. The Yale Law Journal, 88 (5), 950–997. doi:10.2307/795824.

- Rifkin, J., et al., 1991. Toward a New Discourse for Mediation: A Critique of Neutrality. Mediation Quarterly, 9 (2), 151–164. doi:10.1002/crq.3900090206.

- Riskin, L.L., 1996. Understanding Mediators’ Orientations, Strategies, and Techniques: A Grid for the Perplexed. Harvard Negotiation Law Review, 1, 7–51.

- Russell, P., 2019. Willingness to Innovate in Family Law Solicitor Practice in England and Wales: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 41 (2), 153–170. doi:10.1080/09649069.2019.1590900.

- Smith, L. and Hitchings, E., 2023. Where the Wild Things Are: The Challenges and Opportunities of the Unregulated Legal Services Landscape in Family Law. Legal Studies, 43 (4), 658–675. doi:10.1017/lst.2023.9.

- Solicitors Regulation Authority, 2023. Unbundled Services Pilot: Final Report [ online]. SRA. Available from: www.sra.org.uk/unbundled-services-pilot [accessed 4 January 2024].

- Walker, J., et al., 1994. Mediation: The Making and Remaking of Co-Operative Relationships: An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Comprehensive Mediation. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Relate Centre for Family Studies.

- Wong, S. and Cain, R., 2019. The Impact of Cuts in Legal Aid Funding of Private Family Law Cases. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 41 (1), 3–14. doi:10.1080/09649069.2019.1554784.

Appendix 1:

Example of the HwFM dataset

The following table provides an example of two rows in the HwFM dataset. The first row lists the relevant variables. Columns have been excluded where all HwFM cases were logged the same.

The second row concerns three cases (VOL = 3) supported by a solicitor, logged during the third financial quarter of 2015-16. All three cases concerned a child-related issue, resulted in a financial benefit and altogether cost £360 in legal aid expenditure.

By comparison, the third row concerns one (VOL = 1) solicitor-led case in the second financial quarter of 2018-19. The support provider was the Specialist Telephone Advice Service, who determined that the case was not eligible for legal aid on the basis of merits. The case concerned a financial dispute and cost £13.50.