ABSTRACT

Early career academics (ECAs) constitute a significant part of the teaching responsibilities in higher education. However, ECAs, especially those employed on sessional or fixed-term contracts are particularly impacted by a lack of sustainable professional development. This article presents findings from collaborative reflection by a small group of ECAs. They explored their experiences in learning to use pedagogical action research in their own teaching facilitated by an academic developer. This collaborative autoethnographic study collected data from verbal and written reflections by all four authors, including field notes, journals, email exchanges, and group meeting recordings. A grounded approach was used to facilitate the data collection and analysis processes. The data analysis process was also guided by inductive thematic analysis. Authors’ reflections included the action research experience, and their respective teaching and teacher’s identities. These findings show that pedagogical action research was effective in helping the authors understand ourselves better as teachers which fostered our teaching practice. The collaborative reflection environment also created a stronger and supportive environment for teaching, increasing teachers’ professional confidence and a sense of belonging, which was extremely beneficial during the prolonged lockdowns.

Introduction – early career academics in higher education

An early career researcher is usually defined as someone within five years of conferral of a PhD for research funding purposes (e.g. The Australian Research Council Citation2015); however, in the broader reality of academia, the perception of early career is more varied and less linear due to uneven opportunities for career development and progression (Briscoe-Palmer and Mattocks Citation2021). The early stage of an academic career can present a lot of challenges (Gale Citation2011; Hollywood et al. Citation2020; Sims et al. Citation2023; Stratford, Watson, and Paull Citation2023), usually related to the widespread use of casual or fixed-term employment, which leads to limited – and often unfunded – research time. In addition, low pay, lack of job security, heavy teaching loads, and restricted access to resources are also significant factors affecting early career academics (ECAs) (Bosanquet et al. Citation2017; Crimmins Citation2016). Teaching is one of the main career pathways into academia, and often a prerequisite of career advancement. However, most teaching positions in universities in Western higher education contexts are offered as sessional or adjunct contracts (Baik, Naylor, and Corrin Citation2018; Crimmins Citation2016). This leaves early career researchers without access to sustained professional development in teaching (Begum & Saini, Citation2019). From a systematic perspective, it is important to note that the current economic and industrial conditions in many Western countries in which tertiary education takes place are highly casualised (Leathwood and Read Citation2022). While this project cannot address the structural problems within the industry, we note that one major impact of insecure and precarious employment is increased teacher vulnerability and loss of confidence (Knights and Clarke Citation2014), the impacts of which are compounded during early career (Loveday Citation2018). Here, we note the critical spirit of action research methods and its ‘emancipatory potential’ to address different forms of structural inequality (Gibbs et al., Citation2017). We argue action research can empower ECAs and offer a support base to mitigate the impact of precarious employment on their teaching.

The current professional development of tertiary teaching is largely disaggregated by nature (Hallett and Gabb Citation2021). In the authors’ own context of practice, a large Arts faculty at a major university in Australia, professional development of commencing teaching staff is limited and lacks continuity. In terms of formal professional learning, the University has an annual, fee-based tertiary teaching graduate certificate programme. The programme has limited spaces and, because it is not free, it is not compulsory. Thus, the percentage of ECAs who take up this programme is small. There is a six-hour induction programme for commencing tutors. This one-off induction is the only faculty-wide teaching-focused programme. Although each School of the Faculty has an education and student committee, the members of the committee are usually mid-to-senior academics. Several professional development programmes have recently emerged in specific schools within the Faculty to assist and support ECAs in teaching; however, these are in their initial stages and their longevity is uncertain.

Pedagogical action research, as defined by Norton (Citation2019) is the process of ‘using a reflective lens through which to look at some pedagogical issue or problem and methodically working out a series of steps to take action to deal with that issue’ (1) is gaining more recognition in the higher education sector in recent years. Often used in various forms, pedagogical action research is considered an effective practice-informed research method especially in the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) (Gibbs et al. Citation2017; Harvey and Jones Citation2021). Action research is a research methodology in which practitioners engage in systematic reflection on their own practices (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2014). This research approach provides immediate and informed action for practitioner researchers to bring about improvement in practice, which offers opportunities for professional learning (Norton Citation2019). There is also an increase in the use of pedagogical action research and other similar forms of reflective practice as a professional development strategy by academic developers (Arnold Citation2015; Arnold and Norton Citation2021). However, even though action research is used in varied forms and for various purposes, these strategies are not implemented in a systematic or institutionalised manner (Norton Citation2019). Early career academics, especially those on sessional or causal contracts, often miss out on the institutional professional development opportunities available to permanently employed staff. Also, systematic or sustainable pedagogical research opportunities are scarce for this group.

The Collaborative Pedagogical Action Research (CPAR) group was developed in February 2021, to provide a professional learning opportunity for ECAs. The CPAR provided a set of workshops seeking to develop skills in systematic reflective teaching practice, specifically through an action research circle. The CPAR was coordinated by a teaching specialist whose role was academic development. Participating researchers on a causal contract were reimbursed for their participation in the CPAR.

With the goal of professional learning for early careers academics, this study set out to answer the following question: What can ECAs, as teachers, learn from a collaborative action research project?

Conceptual frameworks – action research as a form of reflective teaching practice

Reflective teaching, as Brookfield (Citation2017) defines is ‘the sustained and intentional process of identifying and checking the accuracy and validity of our teaching assumptions as teachers’ (4). This definition calls for a systematic process that continues through a teacher’s career. According to Ashwin et al. (Citation2020), reflective teaching is a cyclical process prompted by dissatisfaction, which requires dialogue and can lead to changes in our teaching practice. One of the commonly used reflective practices in teaching in action research takes a cyclical or spiral form in which the teacher identifies a ‘problem’ or ‘pain point’, acts on changes, observes the changes and reflects on future teaching practice (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2014).

Reflective practice, and more specifically action research, not only offers opportunities for teachers to develop their skill set, but it also fosters a community of expertise. The current body of research in tertiary education offers little insight into what early career researchers reflect on in their teaching through action research in the classroom. This collaborative autoethnographic study investigated how a reflective pedagogical action research group supported the development of teaching and learning strategies among a group of four ECAs. Pedagogical action research is an effective method to provide immediate and evidence-based feedback (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2014) and feedforward (Gibbs et al. Citation2017) to teaching practice. Action research in higher education is valuable but underused and under-researched as an approach to staff development and student learning (Gibbs et al. Citation2017). By using the group research methodology applied for this intervention, the project also offered a space for collegial networking and community building, a critical necessity in encouraging teachers to stay in the profession (Kelchtermans Citation2017). The dialogic nature of the research group also fostered narrative anecdotes, a key element of professional knowledge-building for teachers across disciplines (Doecke, Brown, and Loughran Citation2000).

Self-reflection is key to learning from experience (Boyd and Fales Citation1983) and can create a systematic inquiry into one’s practice, working to reveal the identity and knowledge of the practitioners themselves (Hamilton, Smith, and Worthington Citation2008; Lassonde, Galman, and Kosnik Citation2009). Simply put, reflective teaching helps teachers to understand who they are as a teacher, what they believe in, what they value and what teaching methods they are comfortable using. Action research is a noted approach to reflective practice in educational contexts. It is ‘often sparked by a dilemma in one’s professional practice just as individual transformation can begin with a disorienting dilemma’ (Christie et al. Citation2015, 16).

Action research is arguably the most accessible professional development approach available to higher education teaching practitioners: it is flexible, local and it provides immediate evidence-based feedback to practice (Gibbs et al. Citation2017). For many teachers, the main benefit of action research is its participativeness. The researcher is at the same time the practitioner and participant which allows immediate evidence-based feedback from research to practice (Burns Citation2005).

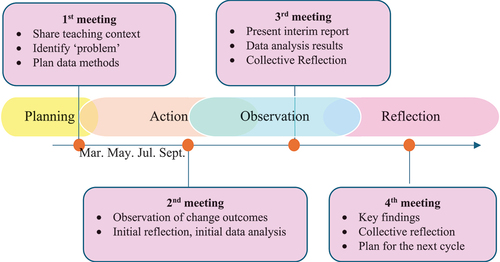

Many variations of action research steps are used in different contexts of teacher reflection. After careful selection, this study adopted Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon (Citation2014)’s four-step model (see ).

Figure 1. The action research spiral (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2014, 19).

We found this spiral model a good fit for the context of our teaching practice as its succinct four-step spiral would be achievable for the participating. In this study, the authors conducted and reflected on their action research projects making use of the Kemmis et al.’s (Citation2014) spiral. During the process of conducting our respective projects, we worked together at all four stages of the spiral. The four steps also helped with planning team progress meetings throughout the research process which will be discussed in more detail in the methodology section.

Methodological framework: collaborative autoethnography

We employed a collaborative autoethnography framework for the current study. We consider that critical reflection is best practiced as a collective endeavour, as the full value of reflection occurs when involving others (Brookfield Citation2017). Autoethnography is an emerging qualitative research method for reflective practice and has been recently adopted by teachers in the higher education sector (e.g. Dutton Citation2021; Nachatar Singh and Chowdhury Citation2021; Scott et al. Citation2022). In autoethnography, methods of self-reporting are often used to develop a reflective practice approach that can nurture individual research interest and knowledge (Hains-Wesson and Young Citation2017). The narrative inquiry in autoethnography is useful to systematically examine teaching practice, deepening the researcher’s understanding of their teaching practice and revealing the researcher’s professional identity (Hamilton, Smith, and Worthington Citation2008). In addition, autoethnography tries to understand personal experiences as they are embedded within a pedagogical culture (Hamilton, Smith, and Worthington Citation2008). We considered this approach was useful for us as a way to explore our practice in an academic culture that is changing and that has a mismatch between the increasing weighting on teaching and learning and the disadvantaged status of ECAs.

We considered autoethnography as an appropriate approach to our research intent. Firstly, this method brings out the researcher’s voice (Hains-Wesson and Young Citation2017), and thus can be empowering as it provides the framework for a systematic and non-judgemental analysis of our teaching practices. In addition, as LaBoskey (Citation2004) argues, the validity of this method is based in the development of trust between participants and requires ongoing interaction. During the course of this study, through regular Zoom meetings and emails, we developed a space of trust and support and were able to reflect on our practice through trusting that our reflections could be safely received and would benefit our projects and personal learning as a teacher.

The collaborative nature of autoethnography is beneficial on several dimensions. The cognitive benefit of collaborative autoethnography (CAE) has been extensively reported. It allows for deeper reflection through exchanges of perspectives, amplification of voices and establishing of collective understandings (Adamson and Muller Citation2018; Arnold and Norton Citation2021; Bowers et al. Citation2022; Chang, Ngunjiri, and Hernandez Citation2012). More studies have recently discovered the social-emotional values of CAE. It helps to develop a sense of community that is often intended to be a safe and respectful space for participants with similar interests and experiences seek support beyond professional matters (de Villiers Scheepers et al. Citation2023; Scott et al. Citation2022). These benefits were fully utilised in the CPAR group. The four authors worked with each other throughout the whole research process, from identifying research questions, designing research instruments, data collection and analysis, presenting findings and reflecting on our teaching during the action research and teaching practices in general. More importantly, the authors found support and resilience from CPAR through the meetings.

The participant researchers

All four researchers were considered ECAs at a large Faculty of a major university in Australia. Three academics were disciplinary academics in screen studies; media and communication; and creative writing and one was a teaching and learning specialist based at the Faculty staff development unit. Among the four ECAs, two had recently completed their doctoral studies, one had recently returned to academia, and one was completing her PhD. Three academics were employed on a fixed-term contract (12 months) and one on a semester-to-semester basis. As the teaching specialist’s role was coordinating the research progress of the group, there were three action research projects by the three disciplinary academics.

The collaborative pedagogical action research (CPAR) group

The Collaborative Pedagogical Action Research (CPAR) group conducted individual action research projects in their own classrooms with the introduction of Kemmis et al, (Citation2014) action research framework. Three action research projects were conducted. Participating ECAs conducted action research projects in their own classrooms with an overarching theme of student engagement. Participants collaborated throughout the whole research process, from framing research questions, to identifying data collection instruments, to reflecting on changes brought by the research.

The CPAR group commenced in the first semester of 2021. Recruitment for participating projects was advertised on the Faculty’s newsletter as part of the Faculty’s teaching and learning initiatives and with a grant from the Faculty’s early career academic committee.

The group met for four times aligned with Kemmis et al.’s (Citation2014) four stages of the classroom action research cycle. More detail of each meeting is outlined in below.

As shown in , the group met for four times throughout 2021, aligning with Kemmis et al.’s (Citation2014) four-step action research cycle: planning, action, observation and reflection. Rather than clearly distinct stages, the four steps were nested with each neighbouring stage. At the planning meeting, some action had already commenced. While action was carrying on, observation and reflection were also occurring. provides a brief overview of the subject context of each action research study.

Table 1. The three action research projects.

As summarised in , all three action research projects investigated student engagement in the researchers’ respective classrooms. Below is a summary of the pain point, action, and changes of each action research study (see ).

Table 2. Project actions and changes.

Laura’s pain point was student motivation and students’ learning approaches. While her subject maintained a high level of enjoyment from students, there was a notable gap between their enjoyment of the class and their willingness to undertake core self-directed learning activities, such as completing required readings. She had previously noted that many students appeared to be undertaking the required readings with the idea that there was a ‘correct’ way to do so, and this self-imposed metric of success was demotivating students from attempting coursework. She settled on using play-based methodology as a way of destigmatising required readings. Play-based methodology has been shown to increase a student’s intrinsic motivation to study (Kapp Citation2012) with the hope that increased motivation would draw students away from a superficial or ‘surface’ approach to their coursework, as described by Entwhistle (Citation2001, 596). In the next cycle, Laura would seek insights from students to identify activities for deeper engagement with the materials.

Laura used play-based activities, such as roleplaying and drawing, in an attempt to increase the student’s intrinsic motivation to undertake self-directed study. Each week, she introduced a short play-based activity that centred on content from their required readings, and recorded student’s ability to respond to direct questions on the readings afterwards in order to measure the efficacy of this intervention. Laura also kept a field journal to capture additional qualitative data and assessed the changes from student survey responses as well as her field journals. Although student survey data showed no change in the completion or depth of engagement with required readings homework, she did observe an increase in participation and a more connected, supportive classroom.

Lauren focused on increasing student participation in the blended classroom during the pandemic. Her research goal was to improve student participation rates by focusing on how offshore students used their cameras over Zoom and observing the number of students who spoke in discussion activities. Her initial observation was that camera use was much higher in a blended class, where students were both on campus and offshore, than in online-only mode. She also observed that students spoke more in small-group settings, as well as in blended classroom environments (as opposed to Zoom online tutorials). As a result of this observation, Lauren sought to explore the factors that motivate students to use their camera and to speak in class, while also reflecting on how she was impacted by their participation, or lack thereof.

Lauren took several actions to achieve the research goal. She conducted a survey to find out student perspectives on teacher presence in the classroom and on Zoom. She then counted the number of times when students had their camera on and off and contrasted this with the number of students who spoke during group and whole-class discussion activities. She was also able to hire a teaching assistant with funds made available to support teaching during the pandemic, who became an additional presence during Zoom tutorials, which became a part of her reflection on how camera use impacted her own feeling of presence.

She found that students tended to turn their camera on during small-group, break-out room activities and most would turn their camera off during tutor-led discussion or whole-class activities. Interestingly, she found that students would turn on their cameras more frequently during student-led discussion – whether it was whole-class or small-group activities. In this sense, students seemed to be more motivated by their peers than by the teacher. The presence of the teaching assistant also brought significant changes to her teaching experience, and she found having another teacher, whose camera was always switched ‘on’, increased her own sense of well-being and improved classroom dynamics. These changes will be discussed in more detail in the findings section. Lauren considered two changes in her subject for the next cycle: to hear from the students on camera use, and to include activities that specifically allow cameras off.

Paige’s pain point was the sensitivity of racial identity among her creative writing students in the classroom. Her concern was that some students’ self-identity could cause inequity in peer work in the class. Paige conducted semi-structured individual interviews with students in both her classes and developed peer review activities on writing sessions for students to reflect on their self-identity to increase awareness of equity.

Paige’s teaching arrangement was changed while participating in CPAR, so she had to adjust her research significantly. She had a different group of students following the transition to online delivery. As a result, she was no longer able to follow through the whole action research cycle with the original group. She adjusted her research plan to implement the actions on the new group and observed the changes from students’ written work. Her key findings were students, especially who were normally more quiet or ‘shy’ in a face-to-face classroom, were more actively engaged in their written feedback to peers in the online environment. As this was a relatively small group, Paige planned to run the cycle with another group to confirm the findings.

Data collection and analysis

The data collection and analysis process was informed by Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory (CGT). Built on the classic grounded theory by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967), in which theories are generated and grounded through data, CGT (Charmaz Citation2000) focuses on the co-construction of knowledge and meaning by the researcher and participant. This approach was deemed suitable for this study for several reasons. As emerging academics, we were relatively new to pedagogical research.

Throughout this project, we kept an open mind, recoding any observation and reflection that emerged from the action research. In group meetings, we shared experiences and reflections that emerged in our teaching and life. The constructivist grounded approach allowed such a continuous data collection process. The reflexive and subjective nature of constructivist grounded approach (Charmaz and Belgrave Citation2012) also played an important role in our gradual exploration and development of our teaching identities.

Data consist of reflections of all four ECAs. Reflections were generated from several forms: four group meetings and post-meeting reflective writings; site journals, and action research reflection on individual projects. Informed by CGT, an inductive thematic analysis (King Citation2004; Miles and Huberman Citation1994) was used to categorise and interpret themes from both written and verbal reflections, carried out in three stages: identifying initial categories, organising sub-categories and synthesising themes and concepts. Cross-analysis were also carried out between the four researchers.

It should be noted that the group of four participants is very small and therefore the research work is more likely to serve as a case study. It is at the reader’s discretion to apply the approach in their own context.

Findings

Inevitably, we spent a lot of our group meeting time reflecting on our respective action research project. We identified three salient findings in our reflections: the importance of developing and maintaining an identity as a teacher (and our employment status); the impact of the research project on our confidence, and the value of peer support.

Our identity and positionality as researchers and teachers

Although all ECAs, our reflections revealed academic and personal diversity in relation to research and teaching. Reflections revealed our identities as a disciplinary researcher wishing to connect more meaningfully with educational research, as an educational researcher wishing to connect with disciplinary academics, and as teachers wishing to connect with students.

One of our researchers, Laura Henderson, shared her experience in which tertiary teacher training in Australia is often surprisingly separated from the development of research on teaching, despite the majority of teachers also being trained in research. She noted how this disjuncture creates a distance between developing pedagogy as praxis:

I came to this group having recently finished working as a research assistant for a project on sustainable pedagogy and student well-being. During my time in that role, I became increasingly interested in contributing to education research in tertiary settings, but I was unsure how or where to begin.

While I had been teaching for many years and researching within my scholarly field, I felt disconnected from education research and was uncertain about how to design a meaningful project. The action research reflexive pedagogy group offered an accessible entry point for education research that was incredibly helpful in overcoming these barriers. Critically, this experience offered a framework for how to create quantifiable metrics for teaching outcomes beyond assessment scores and student evaluation.

For Mei Li, this journey was one to connect pedagogy with discipline, in theory, in practice and in person. Mei joined the Faculty from an education background as a teaching and learning specialist. This was a valuable opportunity for her to learn about the classroom culture and practice from the colleagues in this group, which she considered extremely beneficial for her role. She has felt more confident in her support role:

When working with disciplinary academics, I could feel like an outsider —sometimes isolated - because I often speak from a teacher’s perspective. I look at things very ‘teaching and learning’ oriented while my colleagues tend to be more content focused. Having joined the Faculty very recently, it can be challenging for me to connect straight away with the subject. Now I feel I am more in sync with everybody in this group because we are actually thinking about the same thing regardless of disciplinary backgrounds. Now we are all on the same page of ‘teaching and learning’ as to how to enhance our teaching and learning.

For Paige, her identity as teacher was related to her professional career outside of academia as a creative writer and her former career as a hospitality professional. In this way, Paige connects with educational research as a means of both improving her ability to teach writing and as a lifelong student of creative writing practice itself:

When I first started out, I was so excited to be a teacher. I was just coming from the hospitality industry, and I felt teaching was the career that I wanted to do for so long. I’m also a writer and my best teaching comes out of that shared identity that I have with the students of being a writer. The less I could perform that identity as a teacher, and the more I could perform my identity as a writer I found I was able to then connect with the students and give some Illusion of being equals, as writers. I really believe that, and I was more confident in my writing than in my teaching so that I was also able to give them that generosity. Minimizing the distinction between student and teacher really changed that dynamics. Even in the language I would use to address them, using words like writers instead of students. That changed the tone, because what my students are trying to get out of me, is how do I become a creative writer and how do I become a fiction writer. So that was my way of being a better teacher - letting go of my identity as a teacher altogether.

Within this finding, we realised our employment status can have an impact on our sense of belonging, professional confidence, and emotional well-being. In one of the reflective meetings, Laura considered the ways in which precarious employment frequently leads her to overcommit during the semester. Without secure employment, many tertiary educators will take on as many teaching hours as they are able, which naturally impacts our capacity to reflect on our pedagogy and further develop our praxis. As she noted:

I feel like you don’t necessarily appreciate at the time that you’re developing a bigger body of knowledge…unless you’re doing this sort of reflective work. You just sort of keep going…surviving semester to semester.

At the commencement of this project, Laura had recently moved from casual contracts to a 2-year, fixed-term position, and noted that this difference had significantly increased her ability and motivation to contribute new research into higher education:

From our discussions throughout the year, it was clear that the stress comes from overwork and overcommitment, which can hamper a teachers’ ability to reflect on their work, and as such insecure employment fails to provide sustainable professional development.

For Paige Clark, the casual nature of her work proved to be a hinderance to her ability to develop her teaching practice when she had to prioritise performing her job duties above all else:

The answer to this question directly relates to my ability to participate in the research conducted here. During my time working on this project, I had an extended illness that lasted the duration of an entire semester. As a casual teacher, I was not able to access any sick leave and had to continue to teach. This affected my ability to engage with my teaching practice in the depth that I wanted to and even my participation in the action research itself. This to me shows that despite ECAs best intentions to connect and engage with and improve their pedagogical practices, without the security of ongoing work, it’s easy, and often necessary, for this intention to become a secondary concern.

Peer support for the teacher

The group particularly identified the benefit of peer support through the action research journey. The benefits were on multiple levels and dimensions: conceptual learning of teaching and learning, fostering a sense of community and social-emotional support through the upheaval of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For Laura, one of the core values of the research group was in having the benefit of additional perspectives and in fostering a sense of community between group participants. As she wrote in reflection:

This was particularly useful in points where it seemed that my experiment was failing: group members were quick to point out that there were notable successes as well, which ultimately led my research to a more nuanced conclusion regarding its efficacy and suitable applications.

Laura also noted that having scheduled quarterly meetings on pedagogy had significantly helped her develop a better vocabulary to discuss teaching practice. She noted that it had affirmed a sense of value in her practice and had been an important form of professional development.

For Paige, as a first-year teacher, the peer support was invaluable and often the only chance she got to discuss her teaching practice besides with her subject coordinators:

Going into teaching for the first time, I had very little instruction beyond the excellent support from my subject coordinators. I completed an online module about tutoring at the University, but besides that was left to my own devices. Being able to connect with more-experienced teachers to discuss our practice was validating and encouraging. Not only did I get ideas because of their responses to my experiences, but I learnt from their projects and their insight into their own teaching experiences. Having the time to connect – especially during a global pandemic that is inherently isolating – kept me from becoming completely unmoored within the large network of university casuals.

For Mei, creating and maintaining this group started as a leadership challenge but ended as a supportive community of practice:

As this was the first time I had ever led a team of academics on a research project of a new methodology that I had just learned, I was not sure if I had the right knowledge and experience to make the project a success. However, it turned out my concerns and worries unfounded. All the other three academics were experienced researchers, so they required minimal research support from me. In addition, they joined the group with a well-identified question or pain point already, the discussion of each step caught on very quickly. The discussions we had each time we met up were very much straight into sharing of teaching and the project. Everyone was onboard. We shared a lot of interest and understanding in each other’s work. Towards the middle of the project, I was no longer worried about leading the project, as the project was leading itself. The meetings became highlights of the project during the lockdowns.

In summary, what we learned from the from the action research project has been summarised in three categories, our identity as teachers including employment status, our learning from the action research project, and the importance of peer support. This was also a summary of our teaching life in 2021 during the COVID-19, the transition to online teaching, taking to us as participants and sites of studies, and appreciating the support from each other.

Participation increasing our confidence and sense of belonging, leading to the potential for wider systematic change

Participation occupies a central place in action research (Burns Citation2005). The researcher is not positioned at an objective distance to their research problem or ‘pain point’ but also a participant within the research process. Action researchers adopt a view of the world as made ‘not of things but of relationships which we co-author’ (Reason & Bradbury, Citation2001, 9) and work to create a community of inquiry via the action-reflection cycle. We note here the positive improvements that our participation in the programme had. In particular, participation and the community of inquiry gave us the support base to create more flexible approach.

For example, during Laura’s study, it became apparent that although student engagement with coursework was not significantly improving as a result of play-based learning, her field journal revealed additional benefits not initially foreseen in the study design (such as increased student participation, students expressing positive affect and becoming more likely to support each other during class time). Consequently, activities were adapted but not entirely removed from the curricula. She noted that the actions she undertook felt linked to her participation in the community of inquiry, and the action research methodology (or more specifically, the methodology’s flexibility) allowed her to recalibrate the experiment to maximise the benefits she was seeing in the classroom without entirely undermining the study. As she mentioned in one of the reflective meetings:

I feel a lot more comfortable talking to people in the teaching and learning community about what I do. Where previously I felt … [un]able to put into words what my teaching practice was or… understanding that I had a clear methodology. In a research-oriented approach, you put your flag in the sand on your own practice and … assert its legitimacy and validity as teaching pedagogy.

The changes in Lauren’s classroom were not just about the students, but also about her well-being as a teacher. Here, she found that the attendance of a teaching assistant could shape her action research and view of herself as a teacher:

During the lockdown of semester 2, 2021, I received funding for a teaching assistant, who was tasked with monitoring the Zoom chat and visiting student break-out groups to encourage and initiate participation and exchange.

It help me realise that my confidence and ability was dependent on a need to ‘see’ faces and received expressive feedback that indicated I was being heard. The effect of the presence of the teaching assistant was palpable and, because she always had her camera on, I noticed that I felt much more confident and relaxed. The dialogue I had was infinitely better than any other class I had in my whole career. It just was amazing to have her there ‘cause she would think of things like I just hadn’t crossed my mind in the moment or whatever and it just made everything so much richer.

Building on this realisation through discussions in the action research group, Lauren felt more able to continue teaching into the future in situations without a teaching assistant, as she was more aware of her need for recognition and more confident in situations where students were less engaged or not visible on Zoom.

Paige’s initial goal was to create a more inclusive workshop, and she found that when she was more engaged and responsive as a teacher, that fostered student engagement. Despite the difficulties of initiating a new model, the action research project encouraged her to continue:

It still made me feel like a more structured workshop that had inclusivity as a focus. It worked in not only being a safer space, but also providing a better format for helpful feedback to students. At times when I became frustrated and felt like the new model was more work to initiate and to action, I remembered the research we were doing as part of this project and continued. This became integral in the second half of the year when I had health problems. Without the connection, and responsibility, to the action research project, I might not have engaged with my pedological ambitions; I’m so glad that I did.

The increase in confidence can be regarded as offering the initial steps in a process of addressing systematic inequality in teaching employment from the ‘middle out’ (Hodgson, May, and Marks‐Maran Citation2008) where positive change does not emerge only from ‘top down’ or grassroots movements approaches, but also from within the capacity and mindset of existing employees in the middle. Confidence and belief in capacity, as a result of peer-led groups – rather than individuals – can lead to ‘the development of tools’, like action research, that can create emerging frameworks for reducing ‘skepticism and likely resistance’ (Hodgson, May, and Marks‐Maran Citation2008, 537) to the idea of systematic change itself. In this respect, while we do not suggest that this small group would directly lead to systematic change and a reduction in over-use of precariously employed teaching staff, we do argue that it is a step in the direction of positive change.

Concluding reflection

Looking back at our group project which ran through the whole year of 2021 with the writing process that continued to 2022, a lot has changed in our work respectively, which continues to demonstrate the uncertainty of career progress of ECAs. These changes have been different among the four of us and that again shows the heterogenous nature of ECA life, as our reflections indicated.

Although it may be too early to conclude on the sustainability of this pedagogical action research project as an approach to teacher professional development, each of us in this group have had an experiential learning process of providing immediate evidence-based feedback to our teaching. In this aspect, this approach could be self-sustained by the individual researchers. Although our original intentions to start this project was self-improvement of our teaching practice. As we contributed on with the project and understood the transformative learning it brought to each of us, we considered that colleagues at our Faculty or even the broader community might benefit from our experience by adapting the programme into their local contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamson, J., and T. Muller. 2018. “Joint Autoethnography of Teacher Experience in the Academy: Exploring Methods for Collaborative Inquiry.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 41 (2): 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2017.1279139.

- Arnold, L. 2015. “Action Research for Higher Education Practitioners: A Practical Guide.” https://lydiaarnold.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/action-research-introductory-resource.pdf.

- Arnold, L., and L. Norton. 2021. “Problematising Pedagogical Action Research in Formal Teaching Courses and Academic Development: A Collaborative Autoethnography.” Educational Action Research 29 (2): 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2020.1746373.

- Ashwin, P., D. Boud, S. Calkins, K. Coate, F. Hallett, G. Light, K. Luckett, J. McArthur, I. MacLaren, and M. McLean. 2020. Reflective Teaching in Higher Education. Bloomsbury Academic.

- The Australian Research Council. 2015. Eligibility and Career Interruptions Statement. Australian Research Council. https://www.arc.gov.au/policies-strategies/policy/eligibility-and-career-interruptions-statement.

- Baik, C., R. Naylor, and L. Corrin. 2018. “Developing a Framework for University-Wide Improvement in the Training and Support of ‘Casual’ Academics.” Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management 40 (4): 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1479948.

- Begum, N., and R. Saini. 2019. “Decolonising the Curriculum.” Political Studies Review 17 (2): 196–201.

- Bosanquet, A., A. Mailey, K. E. Matthews, and J. M. Lodge. 2017. “Redefining ‘Early career’ in Academia: A Collective Narrative Approach.” Higher Education Research & Development 36 (5): 890–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1263934.

- Bowers, S., Y. -L. Chen, Y. Clifton, M. Gamez, H. H. Giffin, M. S. Johnson, L. Lohman, and L. Pastryk. 2022. “Reflective Design in Action: A Collaborative Autoethnography of Faculty Learning Design.” Tech Trends 66 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00679-5.

- Boyd, E. M., and A. W. Fales. 1983. “Reflective Learning: Key to Learning from Experience.” Journal of Humanistic Psychology 23 (2): 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167883232011.

- Briscoe-Palmer, S., and K. Mattocks. 2021. “Career Development and Progression of Early Career Academics in Political Science: A Gendered Perspective.” Political Studies Review 19 (1): 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929920925664.

- Brookfield, S. D. 2017. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Burns, A. 2005. “Action Research: An Evolving Paradigm?” Language Teaching 38 (2): 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261444805002661.

- Chang, H., F. Ngunjiri, and K. -A. C. Hernandez. 2012. Collaborative Autoethnography. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Charmaz, K. 2000. “Grounded Theory: Objectivist and Constructivist Methods.” Handbook of Qualitative Research 2 (1): 509–535.

- Charmaz, K., and L. Belgrave. 2012. “Qualitative Interviewing and Grounded Theory Analysis.” The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft 2:347–365.

- Christie, M., M. Carey, A. Robertson, and P. Grainger. 2015. “Putting Transformative Learning Theory into Practice.” Australian Journal of Adult Learning 55 (1): 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1821635.

- Crimmins, G. 2016. “The Spaces and Places That Women Casual Academics (Often Fail To) Inhabit.” Higher Education Research & Development 35 (1): 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1121211.

- de Villiers Scheepers, M., P. Williams, V. Schaffer, A. Grace, C. Walling, J. Campton, K. Hands, D. Fisher, H. Banks, and J. Loth. 2023. “Creating Spaces of Well-Being in Academia to Mitigate Academic Burnout: A Collaborative Auto-Ethnography.” Qualitative Research Journal 23 (5): 569–587. https://doi.org/10.1108/qrj-04-2023-0065.

- Doecke, B., J. Brown, and J. Loughran. 2000. “Teacher Talk: The Role of Story and Anecdote in Constructing Professional Knowledge for Beginning Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 16 (3): 335–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0742-051x(99)00065-7.

- Dutton, J. 2021. “Autonomy and Community in Learning Languages Online: A Critical Autoethnography of Teaching and Learning in COVID-19 Confinement During 2020. Frontiers in Education.” Frontiers in Education 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.647817.

- Entwistle, N., V. McCune, and P. Walker. 2001. “Conceptions, styles, and approaches within higher education: Analytical abstractions and everyday experience.” In Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles, edited by R. J. Sternberg and L. -f. Zhang, 103–136, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Gale, H. 2011. “The Reluctant Academic: Early-Career Academics in a Teaching-Orientated University.” International Journal for Academic Development 16 (3): 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2011.596705.

- Gibbs, P., P. Cartney, K. Wilkinson, J. Parkinson, S. Cunningham, C. James-Reynolds, T. Zoubir, V. Brown, P. Barter, and P. Sumner. 2017. “Literature Review on the Use of Action Research in Higher Education.” Educational Action Research 25 (1): 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1124046.

- Glaser, B., and A. Strauss. 1967. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Routledge.

- Hains-Wesson, R., and K. Young. 2017. “A Collaborative Autoethnography Study to Inform the Teaching of Reflective Practice in STEM.” Higher Education Research & Development 36 (2): 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1196653.

- Hallett, R., and R. Gabb 2021. Promoting Professional Learning for Academic Teaching Practice: Final Report. Learning and Teaching Repository. https://ltr.edu.au/resources/EX15-0169_Hallett_Report_2021.pdf.

- Hamilton, M. L., L. Smith, and K. Worthington. 2008. “Fitting the Methodology with the Research: An Exploration of Narrative, Self-Study and Auto-Ethnography.” Studying Teacher Education 4 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425960801976321.

- Harvey, M., and S. Jones. 2021. “Enabling Leadership Capacity for Higher Education Scholarship in Learning and Teaching (SOTL) Through Action Research.” Educational Action Research 29 (2): 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2020.1803941.

- Hodgson, D., S. May, and D. Marks‐Maran. 2008. “Promoting the Development of a Supportive Learning Environment Through Action Research from the ‘Middle out’.” Educational Action Research 16 (4): 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790802445718.

- Hollywood, A., D. McCarthy, C. Spencely, and N. Winstone. 2020. “‘Overwhelmed at first’: The Experience of Career Development in Early Career Academics.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 44 (7): 998–1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1636213.

- Kapp, K. M. 2012. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education. John Wiley & Sons.

- Kelchtermans, G. 2017. “‘Should I Stay or Should I go?’: Unpacking Teacher Attrition/Retention As an Educational Issue.” Teachers & Teaching 23 (8): 961–977. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2017.1379793.

- Kemmis, S., R. McTaggart, and R. Nixon. 2014. The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research. Springer.

- King, N. 2004. “Using Templates in the Thematic Analysis of Text.” In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research edited by, C. Cassell & G. Symon, Sage.

- Knights, D., and C. A. Clarke. 2014. “It’s a Bittersweet Symphony, This Life: Fragile Academic Selves and Insecure Identities at Work.” Organization Studies 35 (3): 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613508396.

- LaBoskey, V. K. 2004. “The Methodology of Self-Study and Its Theoretical Underpinnings.” In International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices, edited by J.J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V.K. LaBoskey, and T. Russell, 817–869. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6545-321.

- Lassonde, C. A., S. Galman, and C. M. Kosnik. 2009. Self-Study Research Methodologies for Teacher Educators. SensePublishers.

- Leathwood, C., and B. Read. 2022. “Short-Term, Short-Changed? A Temporal Perspective on the Implications of Academic Casualisation for Teaching in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 27 (6): 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1742681.

- Loveday, V. 2018. “The Neurotic Academic: Anxiety, Casualisation, and Governance in the Neoliberalising University.” Journal of Cultural Economy 11 (2): 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2018.1426032.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Sage Publications.

- Nachatar Singh, J. K., and H. A. Chowdhury. 2021. “Early-Career International academics’ Learning and Teaching Experiences During COVID-19 in Australia: A Collaborative Autoethnography.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 18 (5): 12. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.18.5.12.

- Norton, L. 2019. Action Research in Teaching and Learning: A Practical Guide to Conducting Pedagogical Research in Universities. 2nd ed. London & New York: Routledge.

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury. 2001. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Scott, J., J. Pryce, M. B. Fisher, N. B. Reinke, R. Singleton, A. Tsai, D. Li, et al. 2022. “HERDSA TATAL Tales: Reflecting on Academic Growth As a Community for Practice.” In Academic Voices, edited by U. G. Singh, C. S. Nair, C. Blewett, and T. Shea, 269–281. Chandos Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91185-6.00007-0.

- Sims, D., D. Nicholas, C. Tenopir, S. Allard, and A. Watkinson. 2023. “Pandemic Impact on Early Career Researchers in the United States.” SAGE Open 13 (3): 21582440231194394. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231194394.

- Stratford, E., P. Watson, and B. Paull. 2023. “What Impedes and Enables Flourishing Among Early Career Academics?” Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01115-8.