Abstract

Research has demonstrated an unwillingness among travelers to reduce their holiday flying. Recently, however, a movement with people avoiding and problematizing flying has emerged in Sweden and spread internationally. This paper explores how the rising problematization of flying changes the meanings of holiday air travel in a carbon-constrained world. Using travel magazines and digital media sources, we trace changing discourses (overarching ideas and traditions shaping social practices) of holiday air travel in Sweden from 1950–2019. The paper identifies the emergence of a new discourse (Staying on the ground) and shows how it works through moralization (flying is ethically wrong) and persuasion (emphasizing alternatives) to challenge dominant meanings of holiday air travel as desirable and necessary. While Staying on the ground is far from a dominant discourse, there are signs that it has begun to destabilize contemporary cultures of aeromobility. The Staying on the ground discourse exemplifies how meanings attached to ingrained high-carbon practices, and the policies that sustain them, are currently being contested and rearticulated. Acknowledging that low-carbon transformations are fundamentally forms of social and cultural change, the paper illustrates why practices of carbon lock-in are so entrenched, but also how they might be resisted and open up for change.

Introduction

During the last decades, the availability and affordability of holiday air travel have changed considerably. In the early days of commercial aviation, flying was an expensive luxury only a small and wealthy group of people could afford. Package tours made holiday air travel more affordable in the 1950s and 1960s (Kaiserfeld, Citation2010), but flying abroad was still viewed as a luxury, and people saved money for years to afford what was often “promised to be the trip of a lifetime” (Kaiserfeld, Citation2015, p. 188). With the boom of low-cost carriers at the end of the twentieth century, high-income countries saw more hypermobile travel patterns as a growing group of leisure travelers began to fly more frequently, often over great distances and for short periods of time (Gössling et al., Citation2009).

The tourism industry bases a large share of its business model on air travel, which roughly accounts for 50% of tourism transport emissions (World Tourism Organization & International Transport Forum, Citation2019). Since 2000, global passenger air transport activity has more than doubled, and emissions have risen 50% (IEA, Citation2020). Before the coronavirus pandemic, international air traffic was expected to triple between 2015 and 2045 (ICAO, Citation2019). While the pandemic has resulted in a temporary drop in emissions from aviation and tourism, decreased emissions are not likely to be sustained unless the growth trajectories of these sectors are reconsidered (Gössling, Citation2020; Hall et al., Citation2020).

Most air travel is for leisure and holiday purposes, with business flying only constituting a small share of global aviation (Dobruszkes et al., Citation2019). In Sweden, for instance, 80% of the emissions from residents’ air travel are caused by leisure travel and 20% by business travel (Kamb & Larsson, Citation2018). The emissions from air travel are caused by a small minority of people – generally high income and with carbon-intensive lifestyles (Chancel & Piketty, Citation2015; Ivanova & Wood, Citation2020). Gössling and Humpe (Citation2020) estimate that only 11% of the world population flew in 2018, and that 1% of the global population likely are responsible for more than half of aviation emissions. Despite this skewed distribution, air travel is often presented as a social norm (Gössling et al., Citation2019), with social and mass media depicting hypermobility as glamorous (Cohen & Gössling, Citation2015).

Changes in tourism transport behavior can help reduce the climate impact from aviation (Kamb et al., Citation2021). Such changes can either be voluntary, for instance if individuals deliberately limit their holiday flights (Büchs, Citation2017), or achieved through policy interventions targeting consumer behavior, such as taxation or climate labelling (Larsson et al., Citation2020). To motivate travelers to fly less, researchers have highlighted the need for attitude change (e.g. Cocolas et al., Citation2020; Morten et al., Citation2018). However, even groups with pro-environmental attitudes have appeared to be unwilling to reduce their flying (Davison et al., Citation2014; Kroesen, Citation2013). The unwillingness to reduce flying is especially significant in holiday contexts (Barr et al., Citation2010), as desires to explore the world have become part of people’s personal identities (Becken, Citation2007). Moreover, current travel and tourism structures, including societal expectations, policies, and the travel options available, often encourage air travel even for trips that could be taken with other modes of transport (Dickinson et al., Citation2010). While many flights indeed are excessive and avoidable (Kamb et al., Citation2021), the necessity of individual trips is seldom considered (Gössling et al., Citation2019).

It was recognized at least 15 years ago that the air travel industry has constructed a discourse of aviation as too important for society to be restricted (Gössling & Peeters, Citation2007). A discourse can be understood as the overarching ideas and traditions through which a certain phenomenon or practice (e.g. flying) is made sense of and governed (Hajer, Citation2006). The discourse of aviation as too important to be restricted constructs flying as normal, desirable, and beneficial. This normalization of flying downplays the associated environmental impacts (Gössling & Peeters, Citation2007), legitimizes hypermobile lifestyles (Becken, Citation2007), and maintains high-carbon transport behaviors (Cohen & Gössling, Citation2015; Hanna et al., Citation2016). The dominant public discourse on air travel thus sustains, reinforces, and embodies carbon-intensive lifestyles, driving what has been described as “binge mobility” (Urry, Citation2011, p. 74), and a behavioral addiction to flying (Cohen et al., Citation2011).

As a response to the unsustainability of air travel, academics, journalists, and civil society are increasingly problematizing flying. Lately, researchers have discussed the need to fly less to meet climate goals (e.g. Cohen & Kantenbacher, Citation2020; Gössling, Citation2020; Gössling et al., Citation2019; Wynes & Nicholas, Citation2017), especially considering the lack of effective policies (Larsson et al., Citation2019) and viable technological solutions (Peeters et al., Citation2016) to reduce climate pollution from aviation. Mainstream media has also contributed to the discussion about flying less for climate reasons. Moreover, a social movement with people pledging to stay on the ground because of climate concern has recently emerged in Sweden (Jacobson et al., Citation2020; Mkono, Citation2020), and spread internationally (Becken et al., Citation2021). With more and more people voluntarily eliminating or drastically reducing their flying because of climate change (Wormbs & Wolrath Söderberg, Citation2021), how are discourses of holiday air travel being rearticulated and transformed, and with what implications for the future of travel and visions of the good life under climate change? It is particularly important to understand the context and impacts of the emergence of alternative discourses to examine their potential in changing the current aeromobility regime, where one recent study in Switzerland suggests advocates of air travel reductions might impact travel patterns if they succeed in promoting their views and discourses (Kreil, Citation2021).

Drawing on the case of Sweden – the country where the movement to reduce flying emerged – we trace the discursive development of holiday air travel from 1950 to 2019, exploring the discourses that have been dominant in shaping holiday travel practices during this time, and the ways in which these are increasingly contested. The aim is to understand how the rising problematization of flying affects the meanings attached to holiday air travel, and possibly overturns unsustainable travel norms. Through this historical account, we add to current research an understanding for the cultural and discursive embeddedness of holiday travel practices, and how these have come to include new meanings for new groups over time. We are thus able to situate the transformation of unsustainable travel norms as a form of cultural change, rather than just a change in attitudes. As such, the article advances knowledge on the often overlooked role of norms and discourses in facilitating climate action and achieving the broader sustainability transformation in practice.

The research questions of the paper are: (1) What are the dominant discourses of holiday air travel in Sweden? (2) How have the meanings attached to holiday air travel shifted and been problematized across these discourses? In the following, we first review the literature on problematization and discourse analysis. The empirical material consists of a sample of archival and digital media sources from travel magazines, airlines, travel agencies, and newspapers, which we analyze by employing Maarten Hajer’s (Citation1995, Citation2006) argumentative discourse analysis. We identify three discourses – Aspirational luxury, Hypermobility, and Staying on the ground – and analyze their storylines and meanings. The findings show that Staying on the ground problematizes meanings of holiday air travel as desirable and necessary for people and society, thus contesting and to some extent rearticulating previously dominant discourses surrounding travel and tourism. We discuss the broader implications of Staying on the ground for the future of travel and visions of living well in a carbon-constrained world.

Theorizing the problematization of flying

Sweden has been the epicenter of problematizing flying, with a rising public and political debate about the climate impacts from air travel. Beginning in late 2016, a number of journalists, celebrities, and academics declared in Swedish media that they would abandon or drastically reduce their flying because of climate concern (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation2017; Ernman, Citation2016; Hadley-Kamptz, Citation2018; Liljestrand, Citation2018). By the end of 2017, the hashtag #JagStannarPåMarken (#IStayOnTheGround) began to circulate in social media. At about the same time, the new word flygskam (flight shame) became widely discussed internationally in both traditional and social media outlets (Becken et al., Citation2021), possibly increasing the social pressure on people to limit their flying (Light & Brown, Citation2021). In April 2018, the Swedish government introduced a passenger aviation tax. A few months later, an organization running Flight Free campaigns was initiated under the name We Stay on the Ground.

This recent history in Sweden demonstrates how the discourse of aviation as too important to be restricted (Gössling & Peeters, Citation2007) is being called into question, and thus, how flying is being problematized. We adopt a Foucault-influenced understanding of problematizations as ways of constructing and representing problems in governmental practices (Bacchi, Citation2015). Government is understood in broad terms as any attempt at directing or shaping human behavior, including through governing authorities and agencies, forms of knowledge, techniques of government, and the governing of the self (Dean, Citation2010). In this view, government is a “problematizing activity” (Rose & Miller, Citation1992, p. 181) in the sense that issues must be constructed as problematic in order to be governed.

Problematizations – and the subjects and objects produced by them – are shaped and maintained through discourse (Bacchi, Citation2015). There are many different approaches to discourse analysis, but a fundamental assumption is that language shapes how things in the world are understood, and thus how problems are acted upon in relation to those understandings (Dryzek, Citation1997). In political processes, for instance, discourses encapsulate arguments and ideas based on which actors construct specific problem representations (Fischer & Gottweis, Citation2013). Depending on how something is represented as a problem, different ways of addressing the issue appear as possible and desirable (Bacchi, Citation2015). In this way, discourses shape the understanding of events and problems, including what causes them and what needs to be done to address them (Hajer, Citation1995), thus influencing policy action and policy change (Schmidt, Citation2011).

In this article, we use discourse analysis to understand how aviation is constructed as a problem in public discourse. Past research has found that dominant discourses sustain unsustainable travel habits. For instance, everyday climate discourses discourage individuals to engage in sustainable tourism (Hanna et al., Citation2016), air travel industry discourses construct individual behavior change as irrelevant (Gössling & Peeters, Citation2007), technology discourses presents unrealizable promises about sustainable aviation (Peeters et al., Citation2016), and both tourists and frequent business flyers often conceive hypermobility as part of their identity (Becken, Citation2007; Cohen et al., Citation2018). We add to this body of research a focus on the potential of emerging discourses in challenging and possibly transforming the current growth-oriented paradigm in aviation. This is in line with Cohen and Gössling's (Citation2015, p. 1662) attempt to “intervene in dominant discourses that represent hypermobility as glamorous.”

To make sense of the recent problematization of flying, we employ Maarten Hajer’s (Citation1995, Citation2006) argumentative discourse analysis which is situated within the Foucauldian tradition. This approach is suitable for the present study since it provides tools for identifying how meanings are constructed and transformed through discursive interactions. Hajer (Citation2006) defines discourse as “an ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categories through which meaning is given to social and physical phenomena, and which is produced and reproduced through an identifiable set of practices” (Hajer, Citation2006, p. 67). Discourse, in this view, produces specific meanings and identities and thus constructs particular realities. There are usually overlapping and competing discourses conceptualizing the same phenomenon in different ways, but their degree of dominance and influence varies. A dominant discourse is one where central actors draw on a certain discourse to define a problem, and that discourse also enters institutional arrangements (Hajer, Citation2006). Alternative discourses may challenge this dominance as other actors seek support for their definition of the issue. Discursive dominance, thus, is defined and redefined through an argumentative struggle in which actors try to position other actors according to their view and conceptualization (Hajer, Citation1995).

In the context of holiday air travel, discourse can be understood as a particular tradition of thinking about and experiencing travel and tourism practices, through which certain ways of traveling (including norms, behaviors, policies, etc.) are constructed as rational and normal. The intangible elements of discourse shape how people think and act, thereby producing particular identities or ways of being, such the hypermobile traveler (Gössling et al., Citation2009) or “carbon-conscious citizens” (Paterson & Stripple, Citation2010, p. 345). The discourses and meanings surrounding these identities make specific mobile practices (e.g. flying, train traveling) possible and desirable (Cresswell, Citation2010), thus guiding people’s choices about how, why, and where to travel.

Materials and methods

Sample

Our data consist of a sample of written and visual material on holiday air travel, collected from Swedish travel magazines, airline and travel agency archives, and newspapers. We excluded sources explicitly and solely focused on business travel, but included sources that advanced the understanding for the shifting discourse on aeromobility in general, without distinguishing the purpose of travel. Our sample is not exhaustive, but representative of the discourses that have been dominant in shaping meanings of holiday air travel from 1950s onwards. Drawing on the work of Gillian Rose (Citation2016), we looked for a diversity of sources (e.g. images, advertisements, news articles, and personal stories) involved in the discursive construction of holiday air travel, and selected pieces that demonstrated recurring and changing ideas, arguments, and traditions.

Our sample includes both print and digital sources. For print sources, we selected two important Swedish travel magazines from the Lund University Library archive. We choose to look at travel magazines because they illustrate key ideas around traveling and are involved in the production of travel discourse. The first, Vart skall jag resa (Where shall I travel?) was one of the main travel magazines in Sweden during its publication between 1933 and 1961, and was chosen because it provides an overview of the early days of holiday air travel (we read issues from 1950 forward). The second magazine in our sample, Vagabond, was first published in 1987 and was chosen since it is currently the largest travel magazine in Sweden with 147 000 readers in 2019 (Orvesto, Citation2020). We focused specifically on written texts and collected excerpts articulating central ideas about holiday air travel (e.g. views on what is considered normal and/or desirable).

For digital sources, we collected images and advertisements from two leading travel operators, Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) and TUI. We searched their webpages and archives, including the SAS Museum’s archive of historical images, and selected sources that complemented the travel magazine material with new perspectives. To illustrate the recent problematization of flying, we also collected 16 news media articles published between 2016 and 2019, chosen because news media has been an important site for initiating and circulating new views on aviation as problematic. Some key news media sources were drawn from our previous knowledge about the topic. Additional sources were collected through key word searches1 relating to the recent debate about avoiding air travel because of climate change. We searched the online versions of the four largest Swedish newspapers (Aftonbladet, Expressen, Dagens Nyheter, and Svenska Dagbladet) – covering around 85% of the total digital news media circulation in Sweden (TU – Medier i Sverige, Citation2017) – using the media archive database Retriever.

Analytical approach

The analysis was guided by Hajer’s (Citation1995, Citation2006) argumentative discourse analysis. In a first reading of the material, we analyzed structuring ideas and representations of holiday air travel (e.g. as luxurious, glamorous, normal, contested), based on which we defined the dominant discourses. We then studied the effects of these discourses (in terms of the meanings produced) by analyzing the storylines tied to them. A storyline is a condensed statement used by different agents to summarize and give meaning to complex phenomena (Hajer, Citation1995, Citation2006). While discourse refers to the overarching norms and traditions through which a practice is understood, people tell stories to describe and make sense of that practice (Hajer, Citation2006). In other words, discourses construct specific meanings around phenomena; these meanings are disseminated and institutionalized through the use of storylines. For instance, some might use the storyline cultural exchange to highlight the societal benefits of air travel, while others use the storyline moral responsibility as a shorthand for arguing that people should fly less. In this way, people use different storylines to conceptualize the same phenomenon, thus constantly changing the meanings attached to it.

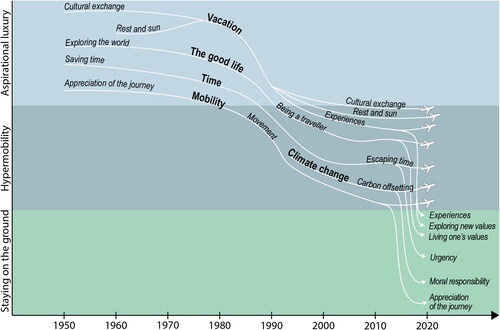

The analysis of storylines was performed using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo 12, following Nielsen’s (Citation2016) approach to conduct text analysis focused on interpreting how storylines appear as recurring arguments or perspectives in different types of material. In a first reading, we coded an initial draft of storylines by interpreting the core messages of statements and arguments (e.g. “flying is luxurious” or “the vacation begins in the airplane”). We then repeated the reading and refined the storylines to better reflect the observed discourse, including modifying, adding, removing, and merging storylines (e.g. “appreciation of the journey”). We coded data for each discourse separately and then compared codes across the discourses. Based on the initial set of codes, we identified five recurring themes, or basic topics that the storylines were about, which provided an analytical framework for tracing changing meanings across the discourses: vacation, the good life, time, mobility, and climate change. The theme of vacation centers around the desired purposes of holiday travel. The good life illustrates values and examples of living well through travel and beyond. Time is articulated in terms of travel time, how people choose to spend their leisure time, or in relation to climate change as something that needs to be addressed within a certain timeframe. Mobility relates to representations of movement and the role transportation plays in the holiday experience. Finally, climate change emerges as a theme after the 1990s, represented for instance as something that can be compensated for or that forces us to rethink travel norms.

Results

We identified three discourses of holiday air travel: Aspirational luxury, Hypermobility, and Staying on the ground. Aspirational luxury has its roots in the 1950s and constructs meanings of holiday air travel as desirable and glamorous. Hypermobility begun in the early 1990s with the emergence of new travel patterns of more frequent flying, illustrating how holiday air travel has shifted from luxurious to a more normalized practice. Staying on the ground emerged around 2016 and calls aviation into question, thus challenging previously established meanings of holiday air travel. These discourses are made up of storylines which evolve and compete over time () and through which specific meanings are attached to holiday air travel (). The meanings of holiday air travel change as storylines change; for example, the meaning of the activity of flying evolves from being an important part of the holiday experience in Aspirational luxury to merely a mode of transportation in Hypermobility.

Figure 1. The discursive development of holiday air travel in Sweden, 1950–2019. The three colored horizontal blocks represent the discourses we identified in media. The white lines with labels in bold represent our five analytical themes, and the labels in italics illustrate the storylines through which meaning is ascribed to holiday air travel within a particular discourse.

Aspirational luxury

Aspirational luxury dates from the rapid growth of commercial air travel in the 1950s and is dominant until the 1990s. As illustrated in , the purpose of vacation is articulated through the storylines cultural exchange and rest and sun. The first centers around the idea that holiday air travel is important for society, while the second focuses on the personal benefits of traveling. For instance, a former sales manager of Scandinavian Airlines says in a 1952 article: “Swedes who travel abroad for holiday become ambassadors for their own country” (Wickberg, Citation1952, p. 5), thus conveying the idea that holiday air travel holds societal importance. The personal benefits are emphasized through ideas about comfort, relaxation, and carefree traveling, expressed especially in relation to charter tour flights to sunny destinations. A warm and sunny climate is portrayed as a vital aspect of holiday travel, in order for people to experience “something stimulating and relaxing” and collect “spiritual vitamins” for the rest of the working year (Varför Väljer Man Sällskapsresor? Citation1958, p. 2). In this way, holiday air travel is portrayed not only as desirable and aspirational, but as a necessity to endure everyday life.

Meanings of the good life are articulated through the storyline exploring the world, presenting air travel to distant locations as “every man’s dream” (Pan Americans “turist”-nät, Citation1953, p. 21). This desire to see the world is articulated in an article with the title “To travel is to live richly,” describing Swedes as “travel-loving northerners” with aspirations to explore new destinations not only once, but “preferably many times.” In the same article, holiday air travel is described as “an important ingredient in the Swede’s increased living standard” (Att resa är att leva rikt, Citation1959, p. 25), conveying meanings of living well through travel.

Time is portrayed as a central aspect of holiday travel, with flying being highlighted as a means for traveling fast and far. This is expressed through the storyline saving time, emphasizing the importance of making “effective use” of every day of the holiday (Vintersportresor med flyg till österrikiska alperna, Citation1957, p. 26). Aviation is seen as a means for this, with air travel making it possible to reach faraway holiday destinations without “losing valuable vacation days” (Ressällskap med månen – Moon Liner, Citation1951, p. 23). In a 1951 article, a journalist writes: “The world shrinks! as an airline would say … In travel time” (Nielsen, Citation1951, p. 6). Another article describes how the “new era with fast air connections has seemingly shortened the distances” (Hedman, Citation1956, p. 30).

Meanings of mobility are expressed through the storyline appreciation of the journey, presenting air travel as an important part of the holiday experience. As seen in a SAS advertisement from the 1950s (), the airplane trip is depicted as comfortable, luxurious, and exciting. In the advert, a traveler is being served breakfast in bed on the airport runway from what appears to be an in-flight chef, while being gently looked after by two ground attendants. The traveler’s shiny, seemingly polished shoes are carefully placed on a red pillow in front of the bed. The advert is focused on the experience of the traveler, with the airplane only visible in the background of the image. Notably, airplane travel is presented as more than just a means for getting to the vacation site; it is an exclusive vacation in itself. Similar depictions are also found in travel magazine stories about the flight experience. One traveler describes flying as a “complete sensation” of “whizzing forward in a world that seems completely unreal” (Mårtensson, Citation1959, p. 16), thus portraying the activity of flying as luxurious and fantastical. Another traveler metaphorically describes the sounds of the airplane engines as a “lullaby for peace and relaxation” and ponders the value of the journey: “Think about it – what is it, that is most appealing – the destination or the journey itself? If you are a traveler in the true sense of the word, then you must at least answer: both equally!” (Willners, Citation1951, p. 12).

Figure 2. Visual representation of the discourse of Aspirational luxury, illustrating the storyline appreciation of the journey. Advertisement from SAS for their new service of breakfast in bed in the 1950s. Photo: © SAS/The SAS Museum Oslo airport Norway. Reproduced by permission of The SAS Museum.

Hypermobility

The Hypermobility discourse begins with increasingly cheap and accessible air travel in the 1990s and continues today. As illustrated in , the purpose of vacation is articulated through three partly conflicting storylines, designed to attract different groups of travelers. Two of them, cultural exchange and rest and sun are continuations from Aspirational luxury, while the experiences storyline emerges in Hypermobility. This new storyline represents a focus on activity-based travel, such as visiting sports or cultural events and city tours. It differs from or even rejects the storyline of rest and sun by changing the conceptualization of vacation and attracting a different group of people. For instance, a 1996 article describes the rise of activity-based travel as a growing desire among travelers to experience something different, rather than being part of a large group (Ekblad, Citation1996, p. 9). Or as explained in another article: “nowadays we do not just want to lie in a sunbed, we want to do something active during our vacation” (Bestelid, Citation2017, p. 3). At the same time, the desire for carefree relaxation through rest and sun persists and sometimes outweighs the search for new experiences or cultural exchanges, as illustrated in this description of a vacation in Tenerife:

We experience no new cultures, no dizzying adventures, we do not meet any exciting new people. […] We only bring home with us the tan and the pre-written postcards that we never got the stamps for. But we have felt obscenely good, and what is left of the Swedish winter feels easier to endure. (Nyreröd, Citation1995, p. 7).

The routinization of holiday air travel is further highlighted through the storyline being a traveler, which portrays traveling as a key aspect of the good life. This storyline turns holiday air travel into an internalized part of people’s identities and lives, and demonstrates how flying (for some groups) has become a taken-for-granted mode of transportation for holiday travel. For instance, one of the magazine articles we read uses the expression “once a traveler, always a traveler” (Wallén, Citation2017, p. 92), indicating that traveling is a lifestyle rather than just an occasional event. Another article describes how traveling gives rise to long-lasting feelings, experiences, and memories “of a kind that can hardly be obtained in any other way,” and that for a traveler, “the journey never ends” (Löfström, Citation1992, p. 23). Traveling is further portrayed as a status marker, with one article claiming: “[t]o travel is worth just as much as a high-paying job, in terms of how other people rate your status” (Wallén, Citation2017, p. 92), thus constructing meanings of holiday air travel as a highly valuable part of life.

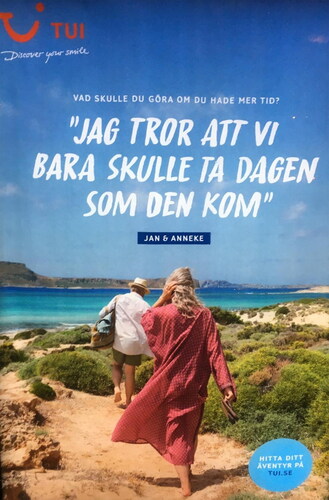

The storyline escaping time presents holiday air travel as a means for letting go of time for a while. This is expressed in an article arguing that when traveling, “time cannot be counted in days or weeks but in moments of presence” (Sjöström, Citation2004, p. 26). TUI, one of Sweden’s largest tour operators, provides another example in their marketing campaign from 2019, asking people what they would do if they had more time. The advertisement above () demonstrates one of the answers, with the text “I think we would just take the day as it comes” written in large letters over a clear blue sky. In the photo, a couple walks barefoot in sand towards a turquoise sea. The imagery is simple, depicting a typical sun, sea, and sand holiday and conveying a feeling of freedom and calm. Notably, TUI’s marketing links the expression of “taking the day as it comes” to getting away from home, indicating that holiday air travel is a necessity or at least a means for disconnecting from the rigid pressures of everyday life.

Figure 3. Visual representation of the Hypermobility discourse, emphasizing the storyline escaping time. The heading reads “What would you do if you had more time?” with the answer “I think we would just take the day as it comes,” implying that air travel to exotic destinations offers a freedom from the workaday time pressures at home. Image: © TUI Sverige, 2019. Reproduced by permission of TUI, Sverige.

In terms of mobility, the storyline movement articulates a shift of the meaning of the activity of flying from luxury experience to merely a mode of transportation. This shift is illustrated in a travel magazine article stating that while flying used to be “a luxury for the few,” the “deadly competition” within the aviation industry has made flying cheap, thus removing its status as “glamorous” and “stylish” and turning it into “one means of transport among others” (Andersson & Lindblom, Citation2001, p. 11). By describing air travel as universal and something that “many can afford” (Andersson & Lindblom, Citation2001, p. 11), flying is presented as a normal and self-evident part of middle-class Swedish life.

The impacts from aviation on climate change are increasingly recognized during the 2000s, illustrated through the emergence of a storyline about carbon offsetting. This is incorporated into the Hypermobility discourse to avoid reducing air travel, by promoting offsets which claim to balance or erase the climate impact, so that people can continue traveling in good conscience. A 2008 article highlights an airline initiative of getting more passengers to compensate their emissions by selling carbon offsets directly in the airplane cabin. The text begins with the question “Coffee, tea, or a climate compensation?” (Janson, Citation2008, p. 28), indicating that carbon credits are offered like any other in-flight product. While the article mentions the growing debate about the climate impact from aviation, flying as such is not at all problematized. TUI provides another example in their 2019 commercial about “positive tourism:”

Today, your holiday with us contributes to a better world. The goal is for it to also contribute to a better climate. […] That is why we are now starting to compensate for all travel with our own flights […] so that you can choose an alternative that is relaxing, comfortable, and climate compensated. (TUI Sverige, Citation2019).

By claiming that the trip is doing good for the world and not just for selfish enjoyment, TUI aims to ensure that their customers can continue traveling with a clean conscience.

Staying on the ground

Staying on the ground begins in 2016 with a growing recognition of the climate impact from aviation. The discourse problematizes previously dominant meanings of holiday air travel as desirable and necessary (see ), and rearticulates alternative storylines and meanings. The desired purpose of vacation is expressed through two interrelated storylines: experiences and exploring new values. These storylines shift focus from tropical holiday destinations to more familiar surroundings and highlight the possibility of achieving the same or similar experiences closer to home. This is illustrated in the news media article “Relieve your climate anxiety – discover exotic Sweden,” which lists a number of Swedish holiday experiences ranging from fishing for oysters in Grebbestad to wine tasting in Skåne and going on moose safari in Småland, concluding that “it is actually possible to travel climate-smart without sacrificing the experience” (Alexandersson, Citation2018). This in turn demonstrates a continuation from Hypermobility in terms of one of the purposes with holiday travel (experiences), but a rearticulation in terms of the means for achieving that purpose (exploring new values).

Ideas about the good life are articulated in Staying on the ground through the storyline living one’s values. This storyline highlights the importance of securing a good life for everyone, including future generations. For example, an opinion piece written by a group of researchers, artists, and athletes contrasts a safe climate with the selfish enjoyment of airplane trips: “Is it okay to deny future generations a stable climate and ecosystems, for the short-term gain of air travel? No, not for us” (Anderson et al., Citation2017). The climate activist Greta Thunberg’s journey across the Atlantic by sailboat also exemplifies the storyline. In an interview with Dagens Nyheter, Greta explains the decision to look for alternative travel options in simple terms: “Since I do not fly, I have to cross the Atlantic in some other way” (Urisman Otto, Citation2019), suggesting a lifestyle shaped by values with air travel not even being an option. Moreover, the sailing journey has given rise to a phenomenon described in Swedish media as “Greta-hitchhiking,” referring to a growing interest among people to get a lift across the sea (Kerpner, Citation2019) and demonstrating how Staying on the ground is gaining influence through particular key events.

A fourth storyline about urgency is drawn upon to emphasize that time is fast running out for emissions to be reduced to the extent needed to meet climate goals. In the previously mentioned opinion piece by Anderson et al. (Citation2017), the authors use the example of a carbon budget to make the claim that the time to reduce emissions is “extremely scarce and shrinking.” With little or no room for air travel in a sustainable carbon budget, and no time to wait for future technologies or policies, they pledge to eliminate their flying because of concern for the climate: “We want to take responsibility for our invisible, destructive junk. And we start with a simple but effective step. We opt out of flying. In the acute climate crisis” (Anderson et al., Citation2017). By highlighting the importance of taking immediate and far-reaching action towards climate goals, the storyline of urgency illustrates how meanings of time are transformed from being considered as something merely personal to something shared in common.

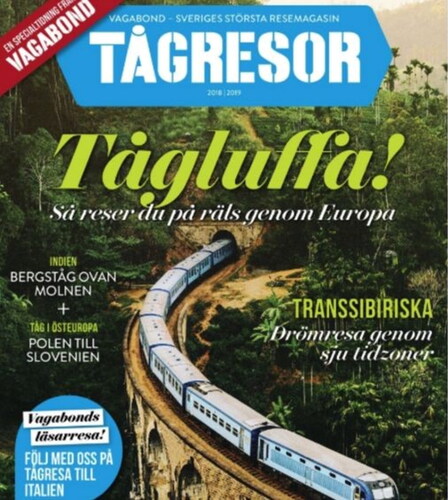

Meanings of mobility are expressed through a revival of the storyline appreciation of the journey. The previous focus on the flight experience is however rearticulated into a focus on train travel as a more sustainable alternative. Concern for the climate plays a key role in this storyline, but it also centers around a notion of slowing down the pace of life. This dual focus is articulated in Vagabond’s 2018 special issue about train travel (), with the chief editor writing that while climate change has made people look for more sustainable travel alternatives,

Figure 4. Visual representation of the discourse of Staying on the ground, through the storyline appreciation of the journey. The heading reads “Interrailing! This is how you travel on rails through Europe.” Image: © Vagabond, 2018. Reproduced by permission of Vagabond.

it is not just about the environment. In the interest in trains, one can discern a longing for a slower way of traveling and living. To let things take their time (Brändström, Citation2018, p. 7).

The longer travel time compared to flying is motivated by highlighting trains not just as a mode of transportation, but as a slower and less stressful way of traveling. Similar to how flying was described in the 1950s, train travel is depicted as an exciting and soothing experience: “traveling by train gives […] a sense of adventure and relaxation at the same time” (Brändström, Citation2019, p. 11).

The importance for individuals to take action for reducing climate change is articulated through a storyline about moral responsibility. This storyline centers around three arguments: caring for others and the future, doing the right thing, and collective responsibility to achieve climate goals. In one of the first personal stories published on the topic in Swedish news media, famous opera singer Malena Ernman (who is also Greta Thunberg’s mother) writes about her decision to stop flying. The article is a call for collective action and care for the climate and future generations, saying that “it is up to us […] to secure the future for everyone” (Ernman, Citation2016). This notion of collectivity is echoed by the co-founder of the organization We Stay on the Ground, writing in Dagens Nyheter that avoiding flying is not only about reducing personal emissions; it also shows others that “change is both necessary and possible” (Rosén, Citation2019). The journalist Jens Liljestrand gives another example in a piece highlighting the ethical concerns of flying to places already affected by climate change: “I am tired of […] taking selfies with a dying world as a background. It is a lifestyle beyond all idiocy. It is the most expensive suicide in world history” (Liljestrand, Citation2018). Another journalist describes the decision to quit flying as a painful sacrifice but that is simply the right thing to do considering the climate (Hadley-Kamptz, Citation2018). These examples show how air travel is being problematized in Staying on the ground by highlighting the moral responsibility of those elite enough to fly to rethink their behavior and contribute to climate goals.

Table 1. Changing meanings of holiday air travel. The analytical themes are listed in the top row, with vacation, the good life, time, and mobility being present throughout and climate change emerging in Hypermobility. The three discourses are listed in the first column, followed by the storylines they are made up of (in italics) and a summary of the meanings they construct under each theme.

Discussion and Conclusions

We have analyzed the development of holiday air travel in Sweden from 1950 to 2019, exploring the discourses that have been dominant in shaping holiday travel practices during this time, and the ways in which these are increasingly contested. From our analysis of historical and contemporary texts, we identified three discourses. The two dominant discourses, Aspirational luxury (1950–1990s) and Hypermobility (1990s–present), both represent holiday air travel as a desirable and necessary part of life and society. Some meanings continue between these two discourses, such as the idea of traveling to the sun for resting from everyday life, while new meanings for new groups of (frequent) travelers also emerge (e.g. traveling as a lifestyle). The latest discourse, Staying on the ground (2016–present), on the other hand, has turned holiday air travel into something problematic that needs to be fixed. As a response to the urgency of taking climate action, and the importance of living one’s values and taking moral responsibility for high-carbon practices, flying is problematized while alternative ways of travel are valorized. In this way, Staying on the ground shapes people into questioning, and in some cases ultimately changing, their travel behavior.

From the theoretical lens of problematization, Staying on the ground can be understood as a new form of low-carbon subjectivity, often publicly articulated, molding travelers into what Paterson and Stripple (Citation2010, p. 345) refer to as “carbon-conscious citizens” governing their own emissions. Our analysis highlights two parallel rationalities through which Staying on the ground works to problematize flying: moralization and persuasion. In terms of moralization, flight-free change agents present the avoidance of air travel as an ethical imperative and highlight meanings of collective wellbeing for people and climate (through the storylines living one’s values, urgency, and moral responsibility). This confirms previous studies indicating that people voluntarily deciding to eliminate or radically reduce their flying tend to feel a moral obligation to contribute to climate goals (Büchs, Citation2017; Jacobson et al., Citation2020; Wormbs & Wolrath Söderberg, Citation2021). Staying on the ground also works through persuasion to present the avoidance of air travel as something positive for the individual (through the storylines exploring new values, experiences, and appreciation of the journey). This demonstrates a potential of Staying on the ground to rearticulate older meanings of holiday air travel into new forms (e.g. searching for similar holiday experiences without the use of airplanes). It also resonates with previous research highlighting that the availability of alternative modes of transportation is important for individuals to limit their flying (Kamb et al., Citation2021; Wormbs & Wolrath Söderberg, Citation2021).

What does Staying on the ground mean for the future of travel and visions of living well in a carbon-constrained world? We have shown that Staying on the ground has begun to contest dominant discourses of holiday air travel. This contestation might influence social and cultural change regarding travel behaviors, as it exemplifies a rearticulation of the meanings attached to high-carbon practices. Notably, alternative ways of living and travel are gaining attention in the public debate, with some people choosing to deliberately limit their flying, either individually or as part of a collective effort. In Sweden, there are indications that a cultural shift in air travel behaviors is already underway, with 14% declaring in a recent survey that they had avoided air travel in 2019 because of climate change (Persson, Citation2020). Staying on the ground is also growing outside of Sweden, with international media writing about the phenomenon and civil society initiatives aimed at reducing air travel spreading globally. For instance, the Flight Free 2021 campaign run by the Swedish organization We Stay on the Ground has so far received registrations from 57 countries (Vi håller oss på jorden, Citation2021). Moreover, previous research confirms that flygskam (flight shame) has become a global phenomenon after spreading widely on Twitter (Becken et al., Citation2021). Thus, it seems that Staying on the ground is having real – if still limited – impact on travel behaviors and norms, in and beyond Sweden, which might also precede policy and industry change (Gössling & Lyle, Citation2021). For this impact to become more widespread, the potential of Staying on the ground to connect with established storylines and rearticulate older meanings into new low-carbon forms is likely critical.

From the perspective of discourse domination (Hajer, Citation2006), Staying on the ground is not yet dominant since it has not been broadly entrenched in travel institutions, such as travel policies or holiday traditions. However, travel and tourism actors are increasingly reacting to the emerging discourse, which indicates a growing impact. The Dutch airline KLM, for instance, urged their travelers to “fly responsibly” and explore other travel options in a 2019 campaign. Sweden’s largest travel magazine Vagabond has published an annual special issue on train travel since 2018. While these actors acknowledge the shifting discourse and, to some extent, incorporate it to their business, other actors actively contest Staying on the ground by presenting counterarguments about the benefits of air travel. The travel agency TUI, for instance, has reacted to the discussion about flight shame, saying that they “do not believe in shame,” but rather “in the power of traveling and meeting others” (TUI Sverige, Citation2019). Similarly, the former director of the International Air Transport Association has criticized initiatives to reduce flights as threatening the social benefits of aviation and undermining the sector’s climate efforts, saying that “we are already helping people to fly sustainably” (IATA, Citation2019). These examples show how actors with a vested interest in continuing with business as usual often take measures to counteract change, thus reinforcing existing institutional lock-in (Seto et al., Citation2016). That Staying on the ground is being recognized, however, whether in terms of support or resistance, indicates that the discourse is growing in influence and increases the pressure on industry actors to become more sustainable. Thus, we predict that examples of travel and tourism agents incorporating or contesting Staying on the ground are likely to become more common.

Our results suggest that Staying on the ground has begun to destabilize contemporary cultures of aeromobility. This has theoretical, policy, and practical implications. Theoretically, the paper advances knowledge on the critical role of discourses in sustaining until now, and possibly soon overturning, unsustainable travel norms. This should be paid more attention in tourism research on flying in order to enable deeper understanding for the cultural context within which travel choices are made, and the challenges and possibilities that exist for transitioning to more sustainable forms of traveling. In terms of policy implications, the paper illustrates a growing public demand for reducing air travel according to climate goals. This can guide policy makers in designing effective transition policies, including policies aimed at achieving social norm change, for example through carbon labels on air tickets and governmental communication (Gössling & Lyle, Citation2021). Thirdly, reducing flying and switching to other forms of traveling has practical implications for local economies and employment. The travel and tourism sector should prepare for changing norms regarding the necessity and desirability of air travel, and take actions that support both absolute emissions reductions and a transition to green and secure jobs.

While we are confident that the material we have collected is representative of and illustrates the discourses and storylines that have been particularly important in shaping meanings of holiday air travel in Sweden from the 1950s onwards, we acknowledge limitations in generalizing our results. Doing discourse analysis implies a close engagement with the material, and thus a selectivity in terms of the quantity of data (Rose, Citation2016). Hence, this study does not necessarily demonstrate every single way in which holiday air travel has been articulated during the studied period. It also misses how air travel has become imperative for practices of daily life beyond holidaying, such as business travel, visiting family and friends, and celebrations (e.g. birthdays, weddings). While business travel is not a dominant reason for flying (Dobruszkes et al., Citation2019), business travelers constitute a hypermobile elite (Cohen & Gössling, Citation2015) that might have impacted the Hypermobility discourse in ways not covered by this study. In terms of special events such as visiting loved ones and celebrations, these are not commonly represented in holiday-focused travel magazines, and thus not included in the scope of this study, but we recognize they constitute an increasingly important motive for flying (Randles & Mander, Citation2009).

For future research, there is a need to further investigate the spread and influence of Staying on the ground, also in the light of Covid-19 potentially accelerating a change in travel norms. How is the pandemic affecting discourses and practices of aeromobility, both regarding leisure and business flying? To what extent is Staying on the ground finding resonance in public and institutional domains, within and beyond Sweden? What actors and segments of society promote Staying on the ground, and what strategies do they employ? It would be particularly interesting to explore young activists’ involvement in the movement to reduce flying, as a Swedish survey has shown that younger generations consider changing travel habits, including flying less, the most important climate action for individuals (Naturskyddsföreningen, Citation2019). Another important question is to examine the potential of Staying on the ground to influence the most frequent flyers. With research suggesting that merely 1% of the world population likely is responsible for more than 50% of the emissions from air travel (Gössling & Humpe, Citation2020), more knowledge about these dynamics is needed for understanding the potential of Staying on the ground to shape wider public perceptions in support of decisive climate policy from governments and business.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Stefan Gössling for feedback on an early draft of this paper, to Santiago Gorostiza for helpful advice on archival research, and to Emma Li Johansson (Lilustrations: http://www.emmalijohansson.com/illustrations/) for illustrating the discursive development of holiday air travel in . Thanks also to the editorial team and three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We used a combination of the following Swedish search terms: undvika* flyg*, avstå* flyg*, välj* bort flyg*, flygfritt, flygskam (English translation: avoid flying, refrain from flying, opt out of flying, flight free, flight shame). This resulted in 366 articles. After reading the titles and short descriptions, 87 articles were selected for further analysis. We read these in full and selected 12 articles that advanced arguments challenging the dominant public discourse on aviation. We complemented these with four articles from our previous knowledge on the topic, which gave us a sample of 16 articles in total.

References

- Alexandersson, J. (2018, October 8). Lindra din klimatångest – upptäck exotiska Sverige. Aftonbladet. https://www.aftonbladet.se/resa/a/rLRxne/lindra-din-klimatangest–upptack-exotiska-sverige

- Anderson, K., Andersson, H., Ernman, M., Ferry, B., Hedberg, M., Lindberg, S., Landgren, J., & Sundström, S. (2017, June 2). Åtta forskare, artister och idrottare:” I den akuta klimatkrisen väljer vi nu bort flyget”. Dagens Nyheter. https://www.dn.se/debatt/i-den-akuta-klimatkrisen-valjer-vi-nu-bort-flyget/

- Andersson, P. J., & Lindblom, B. (2001). Flyget blir bara billigare. Vagabond, 1, 81.

- Att resa är att leva rikt. (1959). Vart Skall Jag Resa?, Vinternummer, 42.

- Bacchi, C. (2015). The turn to problematization: Political implications of contrasting interpretive and poststructural adaptations. Open Journal of Political Science, 05(01), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2015.51001

- Barr, S., Shaw, G., Coles, T., & Prillwitz, J. (2010). “A holiday is a holiday”: Practicing sustainability, home and away. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(3), 474–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.08.007

- Becken, S. (2007). Tourists’ perception of international air travel’s impact on the global climate and potential climate change policies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(4), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost710.0

- Becken, S., Friedl, H., Stantic, B., Connolly, R. M., & Chen, J. (2021). Climate crisis and flying: Social media analysis traces the rise of “flightshame”. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(9), 1450–1469. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1851699

- Bestelid, T. (2017). Nytt år, nya resor. Vagabond, 1, 96.

- Brändström, F. (2018). Tid för tåg. Vagabond, Tågspecial, 98.

- Brändström, F. (2019). Resan börjar från stunden man kliver ombord. Vagabond, Tågspecial, 92.

- Büchs, M. (2017). The role of values for voluntary reductions of holiday air travel. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(2), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1195838

- Chancel, L., & Piketty, T. (2015). Carbon and inequality: From Kyoto to Paris (p. 50). Paris School of Economics

- Cocolas, N., Walters, G., Ruhanen, L., & Higham, J. (2020). Air travel attitude functions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(2), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1671851

- Cohen, S. A., & Gössling, S. (2015). A darker side of hypermobility. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 47(8), 166–1679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15597124

- Cohen, S. A., Hanna, P., & Gössling, S. (2018). The dark side of business travel: A media comments analysis. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 61, 406–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.01.004

- Cohen, S. A., Higham, J. E. S., & Cavaliere, C. T. (2011). Binge flying: Behavioural addiction and climate change. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 1070–1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.01.013

- Cohen, S. A., & Kantenbacher, J. (2020). Flying less: Personal health and environmental co-benefits. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(2), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1585442

- Cresswell, T. (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1068/d11407

- Davison, L., Littleford, C., & Ryley, T. (2014). Air travel attitudes and behaviours: The development of environment-based segments. Journal of Air Transport Management, 36, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2013.12.007

- Dean, M. (2010). Governmentality: Power and rule in modern society. Sage.

- Dickinson, J. E., Robbins, D., & Lumsdon, L. (2010). Holiday travel discourses and climate change. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(3), 482–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.01.006

- Dobruszkes, F., Ramos-Pérez, D., & Decroly, J.-M. (2019). Reasons for flying. In F. Dobruszkes & A. Graham (Eds.), Air transport: A tourism perspective (pp. 23–39). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812857-2.00003-8

- Dryzek, J. S. (1997). The politics of the earth: Environmental discourses. Oxford University Press.

- Ekblad, C. (1996). Svenskar vill ha kultur och äventyr på resan. Vagabond, 10, 89.

- Ernman, M. (2016, December 18). Jorden behöver en överdos av godhet nu. Expressen. https://www.expressen.se/kultur/jorden-behover-en-overdos-av-godhet-nu/

- Fischer, F., & Gottweis, H. (2013). The argumentative turn in public policy revisited: Twenty years later. Critical Policy Studies, 7(4), 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2013.851164

- Gössling, S. (2020). Risks, resilience, and pathways to sustainable aviation: A COVID-19 perspective. Journal of Air Transport Management, 89, 101933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101933

- Gössling, S., Ceron, J.-P., Dubois, G., & Hall, M. C. (2009). Hypermobile travellers. In S. Gössling & P. Upham (Eds.), Climate change and aviation: Issues, challenges and solutions (pp. 131–150). Earthscan.

- Gössling, S., Hanna, P., Higham, J., Cohen, S., & Hopkins, D. (2019). Can we fly less? Evaluating the “necessity” of air travel. Journal of Air Transport Management, 81, 101722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2019.101722

- Gössling, S., & Humpe, A. (2020). The global scale, distribution and growth of aviation: Implications for climate change. Global Environmental Change, 65, 102194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102194

- Gössling, S., & Lyle, C. (2021). Transition policies for climatically sustainable aviation. Transport Reviews, 41(5), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1938284

- Gössling, S., & Peeters, P. (2007). “It does not harm the environment!” An analysis of industry discourses on tourism, air travel and the environment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(4), 402–417. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost672.0

- Hadley-Kamptz, I. (2018, January 16). Jag ser deras resor och min avund vet inga gränser. Expressen. https://www.expressen.se/kultur/isobel-hadley-kamptz/jag-ser-deras-resor-och-min-avund-vet-inga-granser/

- Hajer, M. A. (1995). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process. Oxford University Press.

- Hajer, M. A. (2006). Doing discourse analysis: Coalitions, practices, meaning. In M. van den Brink & T. Metze (Eds.), Words matter in policy and planning. Discourse theory and method in the social sciences (pp. 65–74). Netherlands Geographical Studies.

- Hall, C. M., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2020). Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 577–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759131

- Hanna, P., Scarles, C., Cohen, S., & Adams, M. (2016). Everyday climate discourses and sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(12), 1624–1640. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1136636

- Hedman, F. (1956). Vintersemester på varma breddgrader. Vart Skall Jag Resa?, Vinternummer, 42.

- IATA. (2019, September 3). Remarks of Alexandre de Juniac at Wings of Change Americas 2019, Chicago. IATA. https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/speeches/2019-09-03-01/

- ICAO. (2019). Global Environmental Trends – Present – Present and future aircraft noise and emissions (No. A40-WP/54). ICAO. https://www.icao.int/Meetings/A40/Documents/WP/wp_054_en.pdf

- IEA. (2020). Aviation. IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/aviation-2

- Ivanova, D., & Wood, R. (2020). The unequal distribution of household carbon footprints in Europe and its link to sustainability. Global Sustainability, 3, e18. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.12

- Jacobson, L., Åkerman, J., Giusti, M., & Bhowmik, A. K. (2020). Tipping to staying on the ground: Internalized knowledge of climate change crucial for transformed air travel behavior. Sustainability, 12(5), 1994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051994

- Janson, B. (2008). Klimatkompensation säljs direkt i kabinen. Vagabond, 1, 98.

- Kaiserfeld, T. (2010). From sightseeing to sunbathing: Changing traditions in Swedish package tours; from edification by bus to relaxation by airplane in the 1950s and 1960s. Journal of Tourism History, 2(3), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/1755182X.2010.523147

- Kaiserfeld, T. (2015). Exploring European travel: The Swedish package tour. In P. Lundin & T. Kaiserfeld (Eds.), The making of European consumption (pp. 178–199). Palgrave Macmillian.

- Kamb, A., & Larsson, J. (2018). Klimatpåverkan från svenska befolkningens flygresor 1990–2017 (p. 33).

- Kamb, A., Lundberg, E., Larsson, J., & Nilsson, J. (2021). Potentials for reducing climate impact from tourism transport behavior. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(8), 1365–1382. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1855436

- Kerpner, J. (2019, September 24). Allt fler Greta-liftar med segelbåt över haven. Aftonbladet. https://www.aftonbladet.se/nyheter/a/MRv12o/allt-fler-greta-liftar-med-segelbat-over-haven

- Kreil, A. S. (2021). Visual protest discourses on aviation and climate change. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 2(1), 100015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2021.100015

- Kroesen, M. (2013). Exploring people’s viewpoints on air travel and climate change: Understanding inconsistencies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(2), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.692686

- Larsson, J., Elofsson, A., Sterner, T., & Åkerman, J. (2019). International and national climate policies for aviation: A review. Climate Policy, 19(6), 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1562871

- Larsson, J., Matti, S., & Nässén, J. (2020). Public support for aviation policy measures in Sweden. Climate Policy, 20(10), 1305–1321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1759499

- Light, D., & Brown, L. (2021). Exploring bad faith in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 86, 103082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103082

- Liljestrand, J. (2018, January 13). Jag är trött på att visa mitt barn en döende värld. Expressen. https://www.expressen.se/kultur/jens-liljestrand/jag-ar-trott-pa-att-visa-mitt-barn-en-doende-varld/

- Löfström, T. (1992). Den resandes delaktighet. Vagabond, 6(3–4), 146.

- Mårtensson, S. (1959). Caravelle. Vart Skall Jag Resa?, Jubileumsnummer, 42.

- Mkono, M. (2020). Eco-anxiety and the flight shaming movement: Implications for tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures, 6(3), 223–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-10-2019-0093

- Morten, A., Gatersleben, B., & Jessop, D. C. (2018). Staying grounded? Applying the theory of planned behaviour to explore motivations to reduce air travel. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 55, 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.02.038

- Naturskyddsföreningen. (2019). Barn Och Unga Om Miljö. https://old.naturskyddsforeningen.se/sites/default/files/dokument-media/novusundersokning_unga_om_miljo.pdf

- Nielsen, S.-Å. (1951). Ensam – Eller i gott sällskap? En globetrotters syn på konsten att resa med behållning. Vart Skall Jag Resa? 20(Vårnummer), 29.

- Nielsen, T. D. (2016). From REDD + forests to green landscapes? Analyzing the emerging integrated landscape approach discourse in the UNFCCC. Forest Policy and Economics, 73, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2016.09.006

- Nyreröd, C. (1995). Semester. Vagabond, 1, 82.

- Orvesto. (2020). Räckviddsrapport Orvesto Konsument 2019 Helår. Orvesto. https://www.kantarsifo.se/sites/default/files/reports/documents/rackviddsrapport_orvesto_konsument_2019_helar.pdf

- Pan Americans “turist”-nät (1953). Vart Skall Jag Resa? 22(Sommarnummer), 29.

- Paterson, M., & Stripple, J. (2010). My space: Governing individuals’ carbon emissions. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(2), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1068/d4109

- Peeters, P., Higham, J., Kutzner, D., Cohen, S., & Gössling, S. (2016). Are technology myths stalling aviation climate policy? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 44, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2016.02.004

- Persson, S. (2020). Den svenska miljö- och klimatopinionen 2019. Gothenburg University.

- Randles, S., & Mander, S. (2009). Practices(s) and ratchet(s): A sociological examination of frequent flying. In S. Gössling & P. Upham (Eds.), Climate change and aviation: Issues, challenges and solutions (pp. 245–271). Earthscan.

- Ressällskap med månen – Moon Liner. (1951). Vart Skall Jag Resa?, Sommarnummer, 35.

- Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. Sage.

- Rose, N., & Miller, P. (1992). Political power beyond the state: Problematics of government. The British Journal of Sociology, 43(2), 173–205. https://doi.org/10.2307/591464

- Rosén, M. (2019, May 31). Avstå flyg viktigt för att rädda klimatet. Dagens Nyheter. https://www.dn.se/asikt/avsta-flyget-for-att-radda-klimatet/

- Schmidt, V. A. (2011). Speaking of change: Why discourse is key to the dynamics of policy transformation. Critical Policy Studies, 5(2), 106–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2011.576520

- Seto, K. C., Davis, S. J., Mitchell, R. B., Stokes, E. C., Unruh, G., & Ürge-Vorsatz, D. (2016). Carbon lock-in: Types, causes, and policy implications. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41(1), 425–452. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085934

- Sjöström, B. (2004). Förgängligheten möter på flyget. Vagabond, 1, 81.

- TU – Medier i Sverige. (2017). Braschfakta 2017 (juni). https://tu.se/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Mediefakta_sajten_2017_juni_16.pdf

- TUI Sverige. (2019, April 12). Nu tar vi nästa steg för positiv turism. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v_IW5ISQuzo

- Urisman Otto, A. (2019, December 6). Greta Thunberg tar sabbatsår – åker till Amerika. Dagens Nyheter. https://www.dn.se/nyheter/greta-thunberg-tar-sabbatsar-aker-till-amerika/

- Urry, J. (2011). Climate change and society. Polity Press.

- Varför väljer man sällskapsresor? (1958). Vart Skall Jag Resa? 28(Sommarnummer), 27.

- Vi håller oss på jorden. (2021). Flygfritt 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021, from https://vihallerosspajorden.se/?fbclid=IwAR3yHMZ6O71ckJThzYQC5Vj41vM6Lum4mDy3Fpv6G_up7OMZwxekmQuXr9E

- Vintersportresor med flyg till österrikiska alperna. (1957). Vart Skall Jag Resa?, Vinternummer, 38.

- Wallén, K. (2017). En gång resenär. Vagabond, 1, 96.

- Wickberg, A. (1952). Turistliv och Resliv. Vart Skall Jag Resa? 21(Sommarnummer), 31.

- Willners, B. (1951). Resan till vänligheten. Vart Skall Jag Resa? 20(Vårnummer), 29.

- World Tourism Organization & International Transport Forum. (2019). Transport-related CO2 emissions of the tourism sector – Modelling results. UNWTO. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284416660.

- Wormbs, N., & Wolrath Söderberg, M. (2021). Knowledge, fear, and conscience: Reasons to stop flying because of climate change. Urban Planning, 6(2), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v6i2.3974

- Wynes, S., & Nicholas, K. A. (2017). The climate mitigation gap: Education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environmental Research Letters, 12(7), 074024. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541