Abstract

This qualitative evidence synthesis informs intervention development by systematically searching, evaluating and synthesizing qualitative studies on fatherhood in the context of heavy drinking and other substance use. We searched seven databases, grey literature and reference lists to identify eligible studies. Our international sample includes 156 fathers of different ages, cultural backgrounds and family living arrangements across 14 unique studies. The lead author applied thematic synthesis to develop the themes, in an ongoing dialogue with team members. Our understanding of fatherhood in the context of heavy drinking and other substance use is communicated through six themes. Fathers’ heavy drinking and other substance use can be understood as a method of emotional coping. Fathers’ substance use choices are intertwined with their social contexts from childhood to adulthood. Being a safe presence in children’s lives is a potentially overlooked aspect of fathers’ substance use interventions. In our qualitative evidence synthesis, we observed the pivotal role of supportive relationships in fathers’ substance use trajectories. We recommend co-produced intervention development that considers both fathers as individuals and as members of social networks. This is relevant across statutory, community and voluntary sector settings.

Introduction

Fathers’ engagement in family life has been linked to positive health outcomes for fathers, mothers, babies and children (Sarkadi et al., Citation2008; Pleck, Citation2012). However, child health and family intervention research often relies on mothers’ reporting (Mitchell et al., Citation2007; Davison et al., Citation2017). This lack of parallel focus on fathers limits understanding father-related influences on child and family health outcomes (Davison et al., Citation2017, Barker et al., Citation2017). Understanding the unique and cross-sectoral support needs of fathers is especially important with more marginalized groups, such as fathers who drink heavily and use other substances.

Register-based cohort studies suggests that fathers’ alcohol consumption has independent effects on children’s substance use (Jääskeläinen et al., Citation2016; Thor et al., Citation2022). Correlational evidence on fathers’ alcohol dependence suggests increased drinking negatively effects fathers’ own and mothers’ parenting (Su et al., Citation2018). Importantly, fathers’ and mothers’ alcohol and substance use impacts on various child outcomes already below dependent levels (McGovern et al., Citation2020). However, the quality of the father-child relationship has also been identified as a protective factor against adolescent substance use in a sample of young people at risk of maltreatment (Yoon et al., Citation2018).

Beyond statistics, qualitative literature discusses challenges that fathers’ and mothers’ substance use introduce to young people (Muir et al., Citation2022). Lived experiences of mothers have provided insights into the complex and multidimensional experience of substance use during pregnancy and parenting, and mother-specific stigmatization (Benoit et al., Citation2015). It is important to pay simultaneous attention to the voices of fathers who use substances, to understand how their experiences overlap with mothers as parents, and what are the unique characteristics of fatherhood in the context of substance use.

Most studies on parental substance use interventions focus on mothers (McGovern et al., Citation2021), and parenting interventions lack appreciation of fathers as coparents (Panter-Brick et al., Citation2014). Research evidence on psychosocial alcohol and drug interventions with fathers is limited, especially in relation to other co-occurring psychological and social vulnerability, such as unemployment or partner’s substance use (McGovern et al., Citation2021).

In child protection cultures, mothers have been historically considered as primary carers and responsible for child welfare, whereas engaging with fathers has been avoided (Scourfield, Citation2001, Citation2014). Early ethnography findings illustrate child protection practitioners’ constructions of men as ‘threat’, ‘no use’, ‘irrelevant’ or ‘absent’ (Scourfield, Citation2001). These ideas do not provide a holistic framework for understanding fathers and their relationships with other family members.

The assumption of mothers as the primary parents can also be observed in healthcare settings (Darwin et al., Citation2017; Dimova et al., Citation2022;; Kothari et al., Citation2019). During pregnancy, fathers are not routinely asked about their alcohol consumption patterns (Dimova et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, father roles often go unacknowledged in addiction services (Bell et al., Citation2020). with no identification of which men accessing services are fathers. Range of interventions, quality of person-centred care planning and co-ordination could be broadened by taking notice of fathering.

Recent qualitative longitudinal research in the United Kingdom (UK) has contributed towards an understanding of marginalized fathers’ lived experiences (Brandon et al., Citation2019; Ladlow & Neale, Citation2016; Philip et al., Citation2019, Citation2020), demonstrating how fathers themselves attach value to their family relationships across the life-course. These studies enrich and expand the qualitative evidence-base about fathers with multiple support needs. However, context is an essential consideration in intervention development (Skivington et al., Citation2021). Heavy drinking and/or substance use is a unique context to consider when seeking to support fathers’ health and their positive engagement in family life.

Our study explores the experience of fatherhood in the context of heavy drinking and other substance use. A qualitative evidence synthesis with this focus has not been published to date. We bring together qualitative evidence on fathers’ lived experiences of heavy drinking and other substance use, family relationships and meaningful recovery support. This in-depth understanding can inform complex intervention development across statutory and non-statutory health and social care settings.

Considering the impact of parental drinking and substance use at non-dependent levels (McGovern et al., Citation2020), we are interested in any pattern and volume of drinking and illicit substance use that introduces considerable risks to fathers’ health and potentially other people around them. This risk can be defined by fathers’ own concerns, child or partner report, or clinical diagnostic criteria, such as AUDIT score of 8 or above or a formal diagnosis of alcohol or substance use disorder. We will use the term ‘substance use’ throughout the rest of our paper in reference to fathers’ use of alcohol and illicit substances.

Methods

Our overarching project aim was to inform intervention development in alcohol and drug research, practice and policy, with a specific focus on the perspectives of fathers. We formulated three research questions to guide our search, study selection and analysis:

How do fathers experience their substance use?

How does fathers’ substance use affect their parenting and engagement in family life?

What have fathers found helpful in changing their substance use habits?

A qualitative evidence synthesis was carried out to systematically search, identify, evaluate, analyze and synthesize relevant qualitative data; aiming to develop an understanding that ‘goes beyond’ any of the included studies alone (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). The full protocol is accessible on PROSPERO (Salonen et al., Citation2021). As a qualitative enquiry, our analysis does not seek to present an objective ‘truth’ about fatherhood and addiction, but a systematically developed interpretation of existing available qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022).

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed utilizing the SPIDER acronym (Cooke et al., Citation2012) and search terms from key papers identified when developing the protocol. offers further insights into the terms we used to generate database-specific search strategies. We share our CINAHL search strategy as an example in Supplement 1. MEDLINE (OVID), CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycINFO (OVID), Social Science Database (Proquest), Sociology Collection (Proquest), International Bibliography of Social Sciences (Proquest) and Scopus were searched from inception to July 2022. No filters were applied for country, publication year or language. Grey literature was searched by including dissertations, book chapters and conference abstracts in database searches; searching key websites; and hand-searching reference lists in relevant publications.

Table 1. Search strategy development.

Study selection, quality appraisal and data extraction

Qualitative studies and mixed methods studies with relevant qualitative data were included. The population of interest were fathers with current or previous experience of substance use. ‘Father’ was defined broadly, including biological and non-biological fathers and father figures, and with any residential status with children and mothers. Studies were excluded if they focused on experiences of men who are not fathers, did not address substance use or focused solely on the viewpoints of mothers, children and young people and/or professionals. Two reviewers independently screened each title and abstract. Differences in decisions were either discussed and settled between the two reviewers or referred to another team member for a third deciding opinion.

Each paper was appraised with Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (Citation2018) qualitative checklist by two researchers independently, followed by discussion on any differences in decisions. The CASP checklist presents 10 questions about study design, findings and transferability of results. Decisions whether each study met each quality criteria were recorded on a spreadsheet. Quality assessment outcomes were not considered a reason to exclude any studies but to guide analysis. Demographic details of each included study were recorded. Quotes and researcher interpretations were analyzed.

Data analysis

We applied thematic synthesis; a three-stage process of line-by-line coding, descriptive theme development and generating analytical themes (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). The lead author carried out these stages in ongoing dialogue with other team members. The lead author has practiced as an occupational therapist in psychiatric inpatient services for working age men. The data was therefore analyzed by a researcher whose non-pharmacological training has guided her to view people’s health and wellbeing as an outcome of the interactions between their personal attributes and their physical, social, cultural and institutional environments (Kielhofner, Citation2008). Her practice has centrally involved listening to men’s and father’s life stories in the North East of England. These complex and multilayered stories have often featured substance use.

The lead author first immersed herself in the data by repeated readings and reflective note-keeping. Original themes were extracted from the studies to gain a broad overview of themes across the sample and to reflect on the connections between the data and relevant theories. Line-by-line coding was completed using NVivo 12. The lead author allowed time for an iterative coding process where codes were re-organized, renamed and deleted when required (Saldana, Citation2021). Throughout coding and theme development, the lead author recorded reflections on an electronic diary.

During descriptive theme development (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008), the lead author visualized the interconnections between categorized codes on Microsoft Whiteboard. These initial categories were first tested by allocating each theme a column in a Microsoft Word table and adding corresponding data extracts to each column. This facilitated an understanding on how the data was mapping across the descriptive themes. Once it was established the descriptive themes offered a meaningful and effective way to group and further analyze the data, all extracted data was coded accordingly in NVivo.

The descriptive themes were Living through the battles of addiction, Becoming and being a father and The young boy and the world as he knew it. Each category was further grouped into Personal, Relational and Contextual dimensions. The lead author then copied and pasted extracted data from NVivo-coded data to the Microsoft Word table, matching each extract to the dimension it resonated with most. demonstrates how each included study contributes towards the descriptive themes.

Table 2. Each study’s contribution to descriptive themes.

Our approach to the concept of ‘becoming a father’ is two-fold. Firstly, in many papers fathers spoke retrospectively about becoming a father when their children were born. Moreover, fathers related to their parental and family roles differently across longer periods of time; becoming a father was not a singular event but a living process of ‘doing, being and becoming’ (Hitch et al., Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Wilcock, Citation2002).

Analytical themes (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008) were developed by further cycles of coding, guided by the research questions. The focus was now on interpretation and telling a coherent story (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). This stage of thematic synthesis was carried out in dialogue between the lead author and two experts by experience (EbEs) from a community project that worked towards systemic change to support people experiencing multiple disadvantage, e.g. addiction, mental health problems, imprisonment and homelessness. The lead author and an EbE reviewed the descriptive themes and read through a sample of coded data, each data extract on its individual paper slip on a table, organized to represent the descriptive themes. Together, they reflected on the storylines that connected different data extracts. The lead author continued the second cycle coding independently, guided by these reflections. Another EbE, who is a father, reviewed the analytical themes and the first script of the write-up together with the lead author. This provided assurance of authenticity and respectful phrasing of the findings.

Results

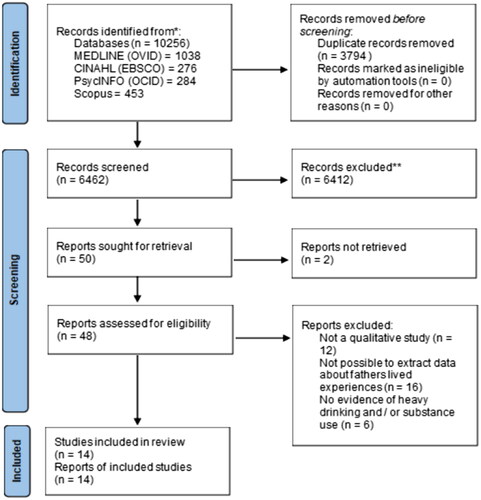

As demonstrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (), initial searches identified 10 256 records. These were exported to EndNote where they were de-duplicated. The remaining 6480 records were exported to Rayyan software for final de-duplication. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 6462 records were screened. 50 papers were identified for full-paper screening, and 48 retrieved. The final sample of eligible studies consisted of 14 peer-reviewed papers.

Sample of fathers across the included papers and quality appraisal

The 14 included peer-reviewed papers provide a sample of 156 fathers, aged 16–64. The papers were published 2003–2020, with 10 papers published between 2017 and 2020. The secondary data sample includes qualitative findings from three continents and seven countries: USA (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Raynor et al., Citation2017; Recto & Lesser, Citation2020; Sieger & Haswell, Citation2020; Stover et al., Citation2017, Citation2018), Northern Uganda (Mehus et al., Citation2021), Norway (Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013), Kenya (Patel et al., Citation2020), Italy (Caponnetto et al., Citation2020), Canada (Lessard et al., Citation2021), the UK (Ahuja et al., Citation2003; Schinkel, Citation2019) and Germany (Dyba et al., Citation2019).

Six papers discuss fathers’ experiences only (Caponnetto et al., Citation2020; Mehus et al., Citation2021; Recto & Lesser, Citation2020; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013; Stover et al., Citation2017, Citation2018), and the rest of the papers include fathers and mothers (Dyba et al., Citation2019; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Raynor et al., Citation2017; Schinkel, Citation2019; Sieger & Haswell, Citation2020); or fathers, mothers and adolescents (Ahuja et al., Citation2003; Lessard et al., Citation2021; Patel et al., Citation2020). Three studies used mixed methods (Ahuja et al., Citation2003; Stover et al., Citation2017, Citation2018), and the rest of the papers represent a range of qualitative methodologies and methods (). Fathers’ substance use profiles and residential status with their children varied across the included studies. We have summarised key demographic details about the total sample of fathers in .

Table 3. Included studies.

Table 4. Fathers across the included studies.

Not all papers explicitly focus on substance use (Lessard et al., Citation2021; Recto & Lesser, Citation2020; Schinkel, Citation2019). Two papers report on ‘parents’ without identifying gender (Dyba et al., Citation2019; Raynor et al., Citation2017). While we were extracting data from these papers, we sought confirming evidence of the parent’s gender and substance use history, e.g. a quoted research participant referring to themselves as a father or talking specifically about their substance use. Where we could not deduct the original informants’ gender and substance use status, we did not extract data.

There are strengths and limitations to note about the quality of the included papers. All papers except for one (Schinkel, Citation2019), state the purpose of research clearly. Qualitative methodology is appropriate in all included studies, either in a qualitative or a mixed methods design. Overall, the data collection methods address the research issues in the included papers. However, the coherence between research question and methods was inconclusive in three papers (Dyba et al., Citation2019; Raynor et al., Citation2017; Stover et al., Citation2018). This was due to limited reporting on the methods (Stover et al., Citation2018) or lack of justification for the methods, e.g. only telephone interviews (Raynor et al., Citation2017) and structured instead of semi-structured or open interviews (Dyba et al., Citation2019).

Only two papers demonstrate researcher reflexivity (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Mehus et al., Citation2021); and six papers do not discuss ethics comprehensively (Ahuja et al., Citation2003; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Lessard et al., Citation2021; Mehus et al., Citation2021; Schinkel, Citation2019; Stover et al., Citation2018). Discussion on the researcher’s position would have been especially important in the two mixed methods studies about an intervention the researchers had developed themselves (Stover et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). The overall methodological quality was inconclusive across various quality criteria in two papers (Dyba et al., Citation2019; Stover et al., Citation2018).

Final themes

We now explore our six final themes: Being a father does not mix well with alcohol and drugs; Active use of substances: Disconnecting from being a Dad; Self-medicating to cope with the realities of life as a boy and as a father; Children matter, whether the father is absent or present; Helpful change is about relationships and community; and Striving under pressure is the only constant. The themes incorporate personal, interpersonal and contextual perspectives that overlap and interact simultaneously in the fathers’ everyday experiences. In Discussion, we will consider how the story told through our themes can inform intervention development efforts.

Being a father does not mix well with alcohol and drugs

Across geographies, fathers identified providing and protecting as essential aspects of fatherhood (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Mehus et al., Citation2021; Patel et al., Citation2020; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013; Stover et al., Citation2017). ‘Geir’, Norwegian father in a sample of 30–49-year-old co-habiting or married fathers described this: ‘I try to take care of my family. Make sure that there is food in the refrigerator and that my family is safe. These are my instincts now.’ (Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013). Failing to provide was an acknowledged fear (Stover et al., Citation2017); fathers strived to provide for the family financially (Mehus et al., Citation2021; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010) and identified the provider role as a key motivator to reduce drinking (Patel et al., Citation2020). A father in Kenya spoke of his experiences in third person: ‘He will not be able to pay for education and he will not have energy to go and dig. His energy goes down as he continues to drink.’ (Mehus et al., Citation2021).

Involved fatherhood appeared to conflict with other roles and choices, such as being a young man and wishing to party (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010); or staying with others to drink after work (Patel et al., Citation2020). Being a father required prioritizing wellbeing in the family over the father’s own immediate interests. An American 42-year-old father in frequent contact with all his four children reflected on his experiences of becoming a father at 18: ‘I felt like I was missing something. I was angry at myself because I put myself in that situation. It was hard. It was definitely not an easy thing to be a parent at 18 years old.’ (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010).

Many fathers appeared to consider substance use and parenting as incompatible (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Lessard et al., Citation2021; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013), as illustrated by a Norwegian father: ‘At that time I thought I was doing well. I thought I saw my kids even if I used drugs. Thought I was a good dad. But in hindsight: My God, you’re not. You’re in your own cloud. You think you manage, but you don’t.’ (Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013). These understandings developed as fathers tried to combine childcare and substance use. In hindsight, they did not consider the substance-using versions of themselves trustworthy and responsible parents. Father living in Canada with experience of co-occurring intimate partner violence and substance use described this: ‘It’s clear that I’m not there for my children when I’m in my head. And when I’m drinking, we all know that […] [there is] less compassion, less empathy, less …’ (Lessard et al., Citation2021).

Active use of substances: disconnecting from being a Dad

‘Dependence has alienated me, it is destructive, with a word it destroys relationships’ (Caponnetto et al., Citation2020), summarised a 43-year-old father residing in a therapeutic community in Italy. Intoxication introduced vulnerability to fathers’ lives, including experiencing physical violence and rough sleeping (Patel et al., Citation2020) and financial loss to the fathers and their families (Ahuja et al., Citation2003; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Patel et al., Citation2020). Obtaining alcohol and/or substances became the fathers’ key priority (Caponnetto et al., Citation2020; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Lessard et al., Citation2021; Mehus et al., Citation2021; Patel et al., Citation2020; Recto & Lesser, Citation2020). They disconnected from their roles in the family and wider community, including their roles as fathers.

Fathers’ relationships with children and mothers were disrupted when the fathers were actively drinking or using substances (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Lessard et al., Citation2021; Mehus et al., Citation2021; Schinkel, Citation2019; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013), as a quote from Norwegian father, ‘Johan’, illustrates: ‘I was mentally blank. I continued recklessly without remorse. And yeah, regret was just a word. I served sentence after sentence in prison.’ (Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013). Some fathers had lost all contact with their children and were not expecting changes (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Schinkel, Citation2019). Fathers excluded others from their lives and were excluded from family and community activities because of their substance use (Ahuja et al., Citation2003; Caponnetto et al., Citation2020; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Patel et al., Citation2020; Schinkel, Citation2019). A quote from a Sikh father living in England’s West Midlands depicts this pattern of mutual exclusion at family level: ‘My family ignore me when I drink and just try and keep to themselves. I prefer this because I like to be left alone when I drink.’ (Ahuja et al., Citation2003).

Some fathers engaged in physical abuse towards their spouses when intoxicated (Ahuja et al., Citation2003; Lessard et al., Citation2021; Patel et al., Citation2020) and many noticed their parenting to be harsher and more inconsistent during active periods of drinking and/or using substances (Dyba et al., Citation2019; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Mehus et al., Citation2021; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013). A 36-year-old father in Germany with one child at home talked about changes in their parenting in relation to guilt and metamphetamine use: ‘Sure, through the past, it’s always such a thing with consequences. Through your guilty conscience, you will give them a pass on some things.’ (Dyba et al., Citation2019). Fathers who were drinking at dependent levels minimized and denied problems, as well as blamed family members of their responses to drinking (Ahuja et al., Citation2003). Many fathers expressed acknowledgement of responsibility for their own behavior and impact on family relationships (Lessard et al., Citation2021; Mehus et al., Citation2021; Recto & Lesser, Citation2020), as described by a father residing in Canada talking about co-occurrence of substance use and intimate partner violence:’Of course they hear us shouting at each other. For sure, they’re fed up with it. And wasn’t I stupid to consult them as if they were psychologists. I was stupid to try and get them on my side.’ (Lessard et al., Citation2021).

Self-medicating to cope with the realities of life as a boy and as a father

There often seemed to be a pain to numb or a burden to ease at the origin of substance use (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Caponnetto et al., Citation2020; Patel et al., Citation2020; Schinkel, Citation2019; Recto & Lesser, Citation2020; Raynor et al., Citation2017). A father in the USA talked about his experiences of growing up in a volatile environment: ‘I was raised in an alcoholic family and the drunker my dad got, the meaner my mom got’ (Raynor et al., Citation2017); and a young Hispanic father taking part in a community fatherhood programme in the USA described how substance use helped him to cope with emotions stemming from traumatic experiences: ‘It’s hard for me to tell people my problems, what’s wrong with me. I keep it all inside, and I take it out on myself by doin’ drugs.’ (Recto & Lesser, Citation2020). Whether the fathers’ pain was rooted in traumatic childhood experiences or long hours of physically straining work, substance use appeared to offer a sense of relief, enjoyment or invincibility, as discussed by a 48-year-old father in the US largely absent from his only son’s life:‘That was all I had—the money, the power, and coke. I was the ‘‘King of the Hill.’ (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010).

As young boys, some of the fathers had started to sell drugs to support the family; and many recalled emotionally absent and/or physically abusive home environments (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010, Recto & Lesser, Citation2020; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013). A Norwegian father, ‘Lars’, reflected on the influence of the childhood environment: ‘It is hard not to fall back on the father figure that I do not want to be’ (Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013) A 43-year-old father in the US with frequent contact with his three children talked about his experiences of growing up in a home where parents used substances and engaged in physical abuse: ‘Even before they put their hands on me I was already crying. I did a lot of that. When I was growing up I had nobody to ask for help.’ (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010). Fathers with these kinds of childhood experiences described having learned to avoid painful emotions by using substances. Their substance use was partly maintained through physical cravings and established habits. However, the onset of their substance use appeared to be about seeking ways to cope with unmet emotional needs.

In the Kenyan and Northern Ugandan contexts (Mehus et al., Citation2021; Patel et al., Citation2020) fathers identified drinking as the best available strategy to cope with daily stressors from work and family life. Although many fathers wanted to reduce or stop drinking, it appeared they had limited meaningful options for going to alcohol dens where their social networks were situated. A father in Kenya who was cohabiting with his partner and children addressed the relationship between being in the alcohol den and drinking heavily: ‘Once I have gone [to the alcohol den], I will not be able to control the amount of alcohol consumption; I will definitely overdo it’ (Patel et al., Citation2020).

Children matter, whether the father is absent or present

Fathers who had contact with their children seemed to cherish and value these relationships (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Stover et al., Citation2017; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013), as illustrated by a 34-year-old father in the US in frequent contact with all his three children: ‘I do tell my kids that I love them all the time. I don’t just use that word, but I mean that word, because I really do love them with all my heart.’ (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010). This joy was overshadowed by the guilt after exposing children to substance use implications. Fathers also expressed worry over new relapses and becoming absent from their children’s lives. A father in a residential substance use programme in the US described his challenges: ‘— the trust thing and letting them know in their hearts that they’re secure because I've been to prison twice and now treatment. My biggest fear is staying out…[I'm] making sure I don’t come back to places like this so I don’t leave them again’ (Stover et al., Citation2017) They acknowledged the importance of developing trust at the children’s pace (Stover et al., Citation2017; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013; Raynor et al., Citation2017; Lessard et al., Citation2021).

Many fathers emphasized the importance of openly discussing their substance use with children (Stover et al., Citation2017; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Raynor et al., Citation2017). Overall, fathers expressed hopes for their children to have a bright future (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Mehus et al., Citation2021; Raynor et al., Citation2017; Stover et al., Citation2017, Citation2018).

Fathers who were absent and physically removed from their children’s lives did not appear to be absent emotionally (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Schinkel, Citation2019; Caponnetto et al., Citation2020). They grieved for the lost opportunities to be with their children and talked about a sense of failure. A father of three in his mid-30s who was interviewed in prison talked about his children being taken into care: ‘It’s took a long time to be able to speak about it, it’s really horrible. It makes you feel like a total failure as a person erm, to no’ have your own kids, to no’ bring up your own kids. It’s a horrible thing.’ (Schinkel, Citation2019). Many fathers were simultaneously involved and absent, as they had become father figures to stepchildren and family members’ children after losing contact with their biological children; or were in contact with some of their children and not with others.

Helpful change is about relationships and community

Fathers’ descriptions of positive change included identification of coping strategies and acceptance of support. A father of one child, in his mid-30s, was interviewed in a Scottish prison and described how his partner’s pregnancy had led him to change his drinking and substance use patterns: ‘I have tae get ma act together here, I want tae be a dad. I sobered up, I stopped drinking. I was still smoking a bit ae hash at night but never touched the drink, and I tried tae get ma head together.’ (Schinkel, Citation2019). There was an acceptance of relapses and gradual gains as part of recovery, albeit reluctant and cautious in some fathers’ accounts (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Patel et al., Citation2020; Sieger & Haswell, Citation2020; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013).

Fathers who had experienced absence, neglect and abuse in their relationships with their own substance-using fathers reported a desire to parent differently (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010; Raynor et al., Citation2017; Recto & Lesser, Citation2020; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013; Caponnetto et al., Citation2020). For some fathers, this motivation turned into a lived commitment that helped them to break cycles of substance use, physical violence and emotional distance.

Being present in children’s lives and providing for the family were key sources of motivation (Patel et al., Citation2020; Raynor et al., Citation2017; Schinkel, Citation2019; Stover et al., Citation2017; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010). A child’s birth was a tangible turning point in some fathers’ stories. A Norwegian father had experienced his first encounter with his firstborn as transformational: ‘When Erik held the baby for the first time, he described it ‘…as if the world on the outside ceased to exist. It was just me and the baby.’ (Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013); a father in the USA connected his firstborn’s birth and his decision to pursue change: ‘when my oldest boy was first born, that’s really was the reason I actually quit drinking cause I was raised in an alcoholic family’ (Raynor et al., Citation2017).

Some fathers had accessed therapy that took their family relationships into consideration; they appeared to value this approach to treatment (Stover et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). Fathers in residential substance use treatment in the US described their therapy experiences: ‘The most important part that stood out to me the most was the emotion coaching — from where I come from, showing emotion is a sensitive side that’s not tolerable.’ (Stover et al., Citation2017); ‘Working with (therapist) really helped me learn how to communicate with my wife and be soft-spoken when I need to’ (Stover et al., Citation2018). In other fathers’ stories, unhelpful counselling and support were characterized by a sole focus on the father as a service user, isolated from their everyday lives and relationships (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010).

Striving under pressure is the only constant

Fathers who had experienced abuse and neglect as children had grown up in pressurized environments characterized by unpredictability and threat of violence (Sieger & Haswell, Citation2020; Recto & Lesser, Citation2020; Knis-Matthews, Citation2010). Substance use appeared to be a part of everyday family life in these homes, and a social norm the fathers had grown to conform to.

Peer pressure to drink alcohol in social situations was identified as a perpetuating factor by some fathers (Ahuja et al., Citation2003; Patel et al., Citation2020), as described by a Sikh father residing with his family in England’s West Midlands: ‘When I attend weddings I see myself in other drunkard men. Everyone urges you to drink until you are finished…’ (Ahuja et al., Citation2003). Fathers in Northern Uganda reported that other men often persuaded or tricked them into drinking when they were trying to reduce or stop alcohol use.

In European family social care contexts, fathers identified a pressure of being a man in a service designed for women, often delivered by women, as described by a Norwegian father, ‘Roger’: ‘You have got one bad hand with no chance to change or renew any of the cards. The other player(s) [referring to the mother and the child protection services] can change their cards indefinitely. You’re stuck with your bad hand’ (Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013). Some fathers worked with addiction service practitioners who advised them against talking about their families and parental roles (Knis-Matthews, Citation2010). All these experiences introduce pressures from low expectations on fathers as parents.

It appears sometimes fathers set themselves the highest pressure to achieve permanent changes in their substance use. Especially in the US and European contexts, fathers appeared to have an unforgiving self-conviction to get things right (Stover et al., Citation2017; Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013). This stemmed from wanting to be an involved father to children and present in everyday family life, as described by a father in substance use treatment in the US: ‘My biggest challenge is doing the right thing all the time.’ (Stover et al., Citation2017). Periods of not using substances were characterized by a sense of no room for errors. A Norwegian father ‘Erik’ illustrated this: ‘This is my last chance. If I don’t succeed [as a father], I’m done. This is not the time to pretend and be superficial. You have to work hard every single second. I cannot afford to fail.’ (Söderström & Skårderud, Citation2013).

Discussion

In our analysis, we considered fathers’ substance use as dynamic interaction of personal, relational and contextual perspectives. We acknowledged the multiple aspects of fathers’ identities—they are simultaneously e.g. parents, partners and ex-partners, family members, community members and health and social care service users. We now continue to consider how our study findings can inform intervention development and multiagency practice with fathers.

Fathers’ lived experiences of substance use

Substance use had first been a coping strategy for many fathers; it offered a temporary relief from various sources of distress from traumatic childhood experiences to work-related physical and mental strain. Furthermore, fathers belonged to social networks that encouraged substance use. During continued substance use, fathers disconnected from family and community life and their parental roles. Individual factors, interpersonal relationships and the broader cultural and structural contexts are intertwined in fathers’ substance use experiences. Both social determinants of health and individual biopsychological considerations need to be incorporated to understand vulnerability to addiction (Amaro et al., Citation2021).

Previous qualitative findings on adverse childhood experiences and later substance use as a parent has mainly quoted mothers (Wangensteen et al., Citation2020). Our synthesized findings add fathers’ voices to this qualitative evidence-base on intergenerational substance use. Robust adaptation of trauma-informed care (Oral et al., Citation2016) can serve fathers who use substances.

Our synthesis offers examples of persistent male peer pressure towards fathers to maintain substance use. We therefore suggest it is relevant and necessary to consider substance-using fathers’ gendered experiences as substance-using men. Men of different ages and backgrounds in West of Scotland (O’Brien et al., Citation2009) have identified a connection between peer acceptance and adhering to masculinity ideals, such as heavy drinking. On the other hand, research in South Africa suggests some men might view substance use as an accessible way of enriching life (Fast et al., Citation2020). Indeed, men’s health and masculinities are increasingly recognized as complex concepts, not to be viewed in isolation from other social determinants of health (Crawshaw & Smith, Citation2009; Hankivsky, Citation2012; Lohan, Citation2007; Schofield et al., Citation2000).

Interventions should apply frameworks that allow discussion about fathers’ gendered experiences of substance use. As discussed above, it is important to acknowledge gender as one aspect of a broader context. To avoid blanket approaches to practice, interventions should include listening to each father’s story and co-constructing a shared understanding about their substance use.

Fathers’ engagement in family life in the context of substance use

Fathers in our sample identified an incompatibility between responsible fathering and substance use. They perceived their substance use to result in inconsistent and inattentive parenting and increased domestic abuse between parents. Notably, the only included study where fathers were actively drinking at dependent levels during data gathering (Ahuja et al., Citation2003) is the only one in our sample where fathers’ accounts had a focus on justifying their drinking and minimizing family members’ concerns and needs. The more sobered voices of fathers from other papers bring forward reflections with complexity and nuance. At one end of the continuum is the disconnection from being a responsible father during substance use. At the other end, fathers are striving to reduce or stop substance use to be consistent sources of stability and protection.

Movement towards more joined up working between sectors, such as Integrated Care Systems in the UK (Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), Citation2021), encourages providers to focus on people’s health and wellbeing in their communities, scoping beyond organizational targets (King’s Fund, Citation2021). Moving away from siloed practice is of importance to substance use services overall. Long waiting times and segregated services act as barriers to support (Gilchrist et al., Citation2014; Gilburt et al., Citation2015), causing challenges to any person who seeks access to services.

The shift towards integration is particularly important with groups who have holistic support needs across a range of services, such as fathers who use substances. They might access support across a variety of settings e.g. specialist drug and alcohol services, primary care, children and family social care, forensic settings, community and inpatient mental health services and community organizations outside statutory care provision. Effective collaboration across these agencies is essential to provide coherent and consistent support to father’s engagement in family life.

Our findings illustrate how becoming a father sometimes provided a reason to change substance use patterns. Similarly, young men in Scotland have described how starting a family helped them to move towards a ‘safe’ form of masculinity after release from prison (Ward et al., Citation2017). While striving to integrate services, it is worthwhile to pay attention to the therapeutic potential of becoming a father and being involved in family life. This might support various involved services to adapt a broader focus on the relational worlds of substance-using fathers.

Fathers accessing support can experience deep guilt and shame about their substance use and parenting (Arenas and Greif, Citation2000; Greif et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, these fathers can have internalized expectations to hide their vulnerability (Greif, Citation2009; Robertson et al., Citation2018). It is essential that treatment environments give fathers an explicit permission to talk about insecurities while developing their relationship skills (Arenas and Greif, Citation2000; Greif, Citation2009). It is also paramount that practitioners are attuned to the potentially unexpressed emotional pain of fathers who are absent from their children’s lives.

Supporting change in fathers’ substance use

In our findings, fathers valued maintaining and re-building relationships with their children and families and having access to fathering-focused counselling. Across services, fathers are to be approached with professional curiosity and invited to share their life stories (Philip et al., Citation2020; Brandon et al., Citation2019).

Some fathers’ experienced an apparent burden of low expectations from professionals considering their potential as parents. Simultaneously, substance use treatment providers have been criticized for recovery ideas that translate into unrealistically high expectations (Neale et al., Citation2015; Gilburt et al., Citation2015). Fathers navigating both addiction services and family social care might then need to make sense of a combination care plans and assessments, that both set a high standard of success and assume failure.

Fathers experiencing addiction and broader multiple disadvantage have described feeling excluded in family health and social care settings that are tailored for women (Robertson et al., Citation2018; Darwin et al., Citation2017). Low numbers of referrals and multiple service co-ordination demands are a challenge for father-focused parenting interventions, even though the peer support they enable can be valued by fathers (Scourfield et al., Citation2016).

Offering peer support and providing services in fathers’ local communities should be considered in intervention development and evaluation. Promising examples of such approaches have been published. Fathers in North West England experiencing substance use and broader multiple disadvantage co-produced a peer support group that fathers, mothers and children found beneficial for father well-being and family relationships (Robertson et al., Citation2018). Fathers in Kenya have welcomed peer-father counsellors in an alcohol and depression intervention (Giusto et al., Citation2021). In line with current guidance on co-production (NIHR, Citation2022), we recommend intervention development and evaluation to be carried out in purposeful collaboration with fathers who have lived expertise of substance use. Mothers and other co-parents, life partners, carers, children and practitioners are key stakeholders in this work.

Father-specific and father-inclusive interventions

We recognise some of our findings apply with other groups alongside fathers. For example, children can motivate parental health choices, regardless of the parent’s gender. We further appreciate that the approaches we have mentioned, e.g. trauma-informed practices, compassionate listening and co-produced peer support, can serve various populations and groups. Substance-using fathers should have equal access to these forms of support.

Context of interventions warrants considerations that are more specific to fathers. Our findings and other research literature suggest feminised health and social care environments are not inviting to fathers (Robertson et al., Citation2018). Simple changes, such as including pictures of fathers and mothers in posters, have had a positive impact on fathers’ sense of inclusion in prenatal care settings (Albuja et al., Citation2019). Adapting environments might need to go further than this to offer comprehensive support to fathers who use substances, including service provision outside traditional health and social care settings and exploring how to offer fathers meaningful leisure spaces that do not encourage substance use. This is especially important for fathers living in precarious situations with few genuine opportunities to change their circumstances (Fast et al., Citation2020).

Theoretical underpinnings and conceptual meanings require careful attention when developing father-inclusive and father-specific interventions. Programme theories and outcomes are challenging to articulate when the whole broadly applied concept of substance use ‘recovery’ lacks a unified definition (White, Citation2007).

The social-ecological model of addiction (Adams, Citation2008), that focuses on reintegration to societal or family relationships is a potentially helpful framework. The social paradigm of ‘people-in-relationships’ and the individual paradigm of ‘people-as-particles’ can ideally complement each other to bring both approaches’ unique strengths together (Adams, Citation2008; Selbekk et al., Citation2015). Fagan and Kaufman (Citation2015) have suggested utilizing attachment theory, family systems theory and risk-resilience theory to measure fatherhood program outcomes, similarly bringing together father-focused and family-wide considerations.

Importantly, both father-specific and broader father-inclusive interventions can bring about positive health and wellbeing outcomes for fathers and people in their lives. Making sense of the intergenerational and community-level outcomes of these interventions is a worthy challenge for future substance use research and intervention development.

Strengths and limitations of our study

Fathers are under-served by alcohol and drug intervention research (McGovern et al., Citation2021; Dimova et al., Citation2022), and not routinely acknowledged as fathers in addiction services (Bell et al., Citation2020). Our synthesis contributes to a growing body of evidence of fathers engaging in research when researchers express interest in their experiences and are willing to tailor research approaches to enable their participation (Philip et al., Citation2020; Philip et al., Citation2019; Brandon et al., Citation2019; Davison et al., Citation2017; Ladlow & Neale, Citation2016; Robertson et al., Citation2018). With a diverse sample of fathers across age groups, substance use profiles and geographies, our qualitative evidence synthesis is well-placed to inform intervention development in a variety of statutory and non-statutory health and social care settings. Simultaneously, there are some limitations to acknowledge.

Our team is distanced from the original data due to the secondary data analysis design. With limited reflexivity reporting in the original papers, we cannot hypothesize how the researchers’ experiences and worldviews contributed to the analyses. Most of the included papers are situated in Western societies. Consequently, our recommendations might be more authentic and transferable to Western contexts.

In most of the included studies, participating fathers were recruited through community and residential programs; they might have been a more accessible group than fathers outside treatments. Similar differences in working with fathers in institutional settings and local communities have been observed in parenting interventions with incarcerated young fathers (Buston, Citation2018). Furthermore, fathers’ ability and willingness to share their sensitive experiences in-depth potentially reflects their overall readiness to explore their choices critically. Our synthesis findings then translate best to situations where a father is seeking support to change or actively participating in treatment. Our insights are more limited when it comes to fathers who are not ready to explore or change their substance use.

Our research team brings together experts by lived experience, population health scientists, mental health researchers, social work expertise and three allied health professional disciplines; this plurality is a strength. However, our project involved experts by lived experience from analysis to dissemination, instead of ‘from inception’ (Fleming & Noyes 2021). Ideally, the study would have had experts by lived expertise in the team from the protocol development onwards. We have sought to identify the best opportunities for meaningful involvement and have reimbursed the involvement of experts by experience according to NIHR payment guidance for researchers (NIHR, Citation2022).

With these limitations, our qualitative evidence synthesis serves as a valuable foundation for further research and intervention development for practitioners, researchers and strategic decision-makers. We summarize our key findings and recommendations in the next concluding paragraphs.

Conclusions

We have systematically searched, critiqued and synthesized qualitative findings about fathers’ experiences of substance use, its perceived influences on family life and potential enablers of health-promoting change. Through our six themes, we have described being and becoming a father in the context of substance use as a multifaceted experience where personal, relational and contextual factors interact across the father’s life-course development.

We have recommended acknowledging fathers’ gendered experiences of substance use as an aspect of their complex and nuanced life stories. We recommend fathers to be routinely included in interventions that are applicable to broader substance-using populations and marginalized parents. We suggest specific attention is paid to intervention contexts in father-focused intervention development. This includes adapting traditional care environments to welcome fathers, offering fathers support in their local communities and developing venues that endorse meaningful leisure for fathers without endorsing substance use. Intervention development should purposefully include peer support approaches. Research should be carried out as a co-production with fathers who have experience of substance use. Theoretical underpinnings in intervention development will ideally combine individual and social-ecological paradigms. Similarly, we suggest intervention outcomes should consider fathers, children and young people, partners, families and wider social networks.

Supplement_1_CINAHL_search_strategy.docx

Download MS Word (14.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, P. J. (2008). Fragmented Intimacy. Addiction in the social world. Springer.

- Ahuja, A., Orford, J., & Copello, A. (2003). Understanding how families cope with alcohol problems in the UK West Midlands Sikh Community. Contemporary Drug Problems, 30(4), 839–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/009145090303000406

- Albuja, A. F., Sanchez, D. T., Lee, S. J., Lee, J. Y., & Yadava, S. (2019). The effect of paternal cues in prenatal care settings on men’s involvement intentions. PLoS ONE, 14(5), e0216454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216454

- Amaro, H., Sanchez, M., Bautista, T., & Cox, R. (2021). Social vulnerabilities for substance use: Stressors, socially toxic environments, and discrimination and racism. Neuropharmacology, 188, 108518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108518

- Arenas, M. L. & Greif, G. L. (2000). Issues of fatherhood and recovery for VA substance abuse patients. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 32(3), 339–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2000.10400458

- Barker, B., Iles, J. E., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2017). Fathers, fathering and child psychopathology. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.015

- Bell, L., Herring, R., & Annand, F. (2020). Fathers and substance misuse: A literature review. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 20(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-06-2020-0037

- Benoit, C., Magnus, S., Phillips, R., Marcellus, L., & Charbonneau, S. (2015). Complicating the dominant morality discourse: Mothers and fathers’ constructions of substance use during pregnancy and early parenthood. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0206-7

- Brandon, M., Philip, G., & Clifton, J. (2019). Men as fathers in child protection. Australian Social Work, 72(4), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2019.1627469

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis. A practical guide. SAGE.

- Buston, K. (2018). Recruiting, retaining and engaging men in social interventions: Lessons for implementation focusing on a prison-based parenting intervention for young incarcerated fathers. Child Care in Practice : Northern Ireland Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Child Care Practice, 24(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2017.1420034

- Caponnetto, P., Triscari, C., & Maglia, M. (2020). Living fatherhood in adults addicted to substances: A qualitative study of fathers in psycho-rehabilitative drug addiction treatment for heroin and cocaine. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031051

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

- Crawshaw, P., & Smith, J. (2009). Men’s health: Practice, policy, research and theory. Critical Public Health, 19(3–4), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590903302071

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2018). Qualitative studies checklist. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Darwin, Z., Galdas, P., Hinchliff, S., Littlewood, E., McMillan, D., McGowan, L., & Gilbody, S. (2017). Fathers’ views and experiences of their own mental health during pregnancy and the first postnatal year: A qualitative interview study of men participating in the UK Born and Bred in Yorkshire (BaBY) cohort. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1229-4

- Davison, K. K., Charles, J. N., Khandpur, N., & Nelson, TJ. (2017). Fathers’ perceived reasons for their underrepresentation in child health research and strategies to increase their involvement. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(2), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2157-z

- Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) (2021). Integration and innovation: Working together to improve health and social care for all. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/working-together-to-improve-health-and-social-care-for-all

- Dimova, E. D., McGarry, J., McAloney-Kocaman, K., & Emslie, C. (2022). Exploring men’s alcohol consumption in the context of becoming a father: A scoping review. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 29(6), 643–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2021.1951669

- Dyba, J., Moesgen, D., Klein, M., & Leyendecker, B. (2019). Methamphetamine use in German families: Parental substance use, parent–child interaction and risks for children involved. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(4), 583–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2018.1528459

- Fagan, J., & Kaufman, R. (2015). Reflections on theory and outcome measures for fatherhood programs. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 96(2), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.2015.96.19

- Fast, D., Bukusi, D., & Moyer, E. (2020). The knife’s edge: Masculinities and precarity in East Africa. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 258(2020), 113097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113097

- Flemming, K., & Noyes, J. (2021). Qualitative evidence synthesis: Where are we at? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 160940692199327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406921993276

- Gilburt, H., Drummond, C., & Sinclair, J. (2015). Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: A qualitative study from the service users’ perspective. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 50(4), 444–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv027

- Gilchrist, G., Moskalewicz, J., Nutt, R., Love, J., Germeni, E., Valkova, I., Kantchelov, A., Stoykova, T., Bujalski, M., Poplas-Susic, T., & Baldacchino, A. (2014). Understanding access to drug and alcohol treatment services in Europe: A multi-country service users’ perspective. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 21(2), 120–130. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2013.848841

- Giusto, A., Johnson, S. L., Lovero, K. L., Wainberg, M. L., Rono, W., Ayuku, D., & Puffer, E. S. (2021). Building community-based helping practices by training peer-father counselors: A novel intervention to reduce drinking and depressive symptoms among fathers through an expanded masculinity lens. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 95(2021), 103291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103291

- Greif, G. L. (2009). One dozen considerations when working with men in substance abuse groups. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 41(4), 387–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2009.10399777

- Hankivsky, O. (2012). Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74(11), 1712–1720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.029

- Hitch, D., Pépin, G., & Stagnitti, K. (2014a). In the footsteps of wilcock, part one: The evolution of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2014.898114

- Hitch, D., Pépin, G., & Stagnitti, K. (2014b). In the footsteps of wilcock, part two: The interdependent nature of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2014.898115

- Jääskeläinen, M., Holmila, M., Notkola, I.-L., & Raitasalo, K. (2016). Mental disorders and harmful substance use in chidlren of substance abusing parents: A longitudinal register-based study on a complete birth cohort born in 1991. Drug and Alcohol Review, 35(6), 728–740. November 2016, https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12417

- Kielhofner, G. (2008). Model of human occupation: Theory and application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- King’s Fund (2021). Integrated care systems explained: Making sense of systems, places and neighbourhoods. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/integrated-care-systems-explained

- Knis-Matthews, L. (2010). The destructive path of addiction: Experiences of six parents who are substance dependent. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 26(3), 201–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2010.498728

- Kothari, A., Thayalan, K., Dulhunty, J., & Callaway, L. (2019). The forgotten father in obstetric medicine. Obstetric Medicine, 12(2), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753495X18823479

- Ladlow, L., & Neale, B. (2016). Risk, resource, redemption? The parenting and custodial experiences of young offender fathers. Social Policy and Society : A Journal of the Social Policy Association, 15(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746415000500

- Lessard, G., Lévesque, S., Lavergne, C., Dumont, A., Alvarez-Lizotte, P., Meunier, V., & Bisson, S. M. (2021). How adolescents, mothers, and fathers qualitatively describe their experiences of co-occurrent problems: Intimate partner violence, mental health, and substance use. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(23–24), NP12831–NP12854. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519900968

- Lohan, M. (2007). How might we understand men’s health better? Integrating explanations from critical studies on men and inequalities in health. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 65(3), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.020

- McGovern, R., Newham, J. J., Addison, M. T., Hickman, M., & Kaner, E. F. S. (2021). Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for reducing parental substance misuse. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3), CD012823. Accessed 18 July 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012823.pub2

- McGovern, R., Gilvarry, E., Addison, M., Alderson, H., Geijer-Simpson, E., Lingam, R., Smart, D., & Kaner, E. (2020). The association between adverse child health, psychological, educational and social outcomes, and nondependent parental substance: A rapid evidence assessment. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 21(3), 470–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018772850

- Mehus, C. J., Wieling, E., Thomas Oloya, O., Laura, A., & Ertl, V. (2021). The impact of alcohol misuse on fathering in Northern Uganda: An ethnographic study of fathers. Transcultural Psychiatry, 58(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461520943315

- Mitchell, S. J., See, H. M., Tarkow, A. K. H., Cabrera, N., McFadden, K. E., & Shannon, J. D. (2007). Conducting studies with fathers: Challenges and opportunities. Applied Developmental Science, 11(4), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888690701762159

- Muir, C., Adams, E. A., Evans, V., Geijer-Simpson, E., Kaner, E., Phillips, S. M., Salonen, D., Smart, D., Winstone, L., & McGovern, R. (2022). A systematic review of qualitative studies exploring lived experiences, perceived impact, and coping strategies of children and young people whose parents use substances. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 0(0), 152483802211342. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221134297

- Neale, J., Tompkins, C., Wheeler, C., Finch, E., Marsden, J., Mitcheson, L., Rose, D., Wykes, T., & Strang, J. (2015). “You’re all going to hate the word ‘recovery’ by the end of this”: Service users’ views of measuring addiction recovery. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 22(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2014.947564

- National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). 2022. Payment guidance for researchers and professionals. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/payment-guidance-for-researchers-and-professionals/27392

- O’Brien, R., Hunt, K., & Hart, G. (2009). ‘The average Scottish man has a cigarette hanging out of his mouth, lying there with a portion of chips’: Prospets for change in Scottish men’s constructions of masculinity and their health-related beliefs and behaviours. Critical Public Health, 19(3–4), 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590902939774

- Oral, R., Ramirez, M., Coohey, C., Nakada, S., Walz, A., Kuntz, A., Benoit, J., & Peek-Asa, C. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and trauma informed care: The future of health care. Pediatric Research, 79(1–2), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.197

- Panter-Brick, C., Burgess, A., Eggerman, M., McAllister, F., Pruett, K., & Leckman, J. F. (2014). Practitioner review: Engaging fathers – recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 55(11), 1187–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12280

- Patel, P., Kaiser, B. N., Meade, C. S., Giusto, A., Ayuku, D., & Puffer, E. (2020). (January 2020). Problematic alcohol use among fathers in Kenya: Poverty, people, and practices as barriers and facilitators to help acceptance. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 75, 102576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.10.003

- Philip, G., Clifton, J., & Brandon, M. (2019). The trouble with fathers: The impact of time and gendered thinking on working relationships between fathers and social workers in child protection practice in England. Journal of Family Issues, 40(16), 2288–2309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18792682

- Philip, G., Youansamouth, L., Bedston, S., Broadhurst, K., Hu, Y., Clifton, J., & Brandon, M. (2020). “I had no hope, I had no help at all”: Insights from a first study of fathers and recurrent care proceedings. Societies, 10(4), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10040089

- Pleck, J. H. (2012). Integrating father involvement in parenting research. Parenting, 12(2-3), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2012.683365

- Raynor, P. A., Pope, C., York, J., Smith, G., & Mueller, M. (2017). Exploring self-care and preferred supports for adult parents in recovery from substance use disorders: Qualitative findings from a feasibility study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(11), 956–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1370520

- Recto, P., & Lesser, J. (2020). The parenting experiences of hispanic adolescent fathers: A life course theory perspective. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 42(11), 918–926. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945920935593

- Robertson, S., Woodall, J., Henry, H., Hanna, E., Rowlands, S., Horrocks, J., Livesley, J., & Long, T. (2018). Evaluating a community-led project for improving fathers’ and children’s wellbeing in England. Health Promotion International, 33(3), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daw090

- Saldana, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE.

- Salonen, D., McGovern, R., Kaner, E., Sobo-Allen, L., Bourne, J., Adams, E., Muir, C., & Herlihy, J. (2021). Fathers’ lived experiences of heavy drinking and other substance use, how these habits affect on their engagement in family life, and enablers of health behaviour change. Qualitative evidence synthesis to identify and explore emerging narratives in applied health and social care research. PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021258493. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021258493

- Sarkadi, A., Kristiansson, R., Oberklaid, F., & Bremberg, S. (2008). Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992), 97(2), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00572.x

- Schinkel, M. (2019). Rethinking turning points: Trajectories of parenthood and desistance. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 5(3), 366–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-019-00121-8

- Schofield, T., Connell, R. W., Walker, L., Wood, J. F., & Butland, D. L. (2000). Understanding men’s health and illness: A gender-relations approach to policy, research, and practice. Journal of American College Health : J of ACH, 48(6), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480009596266

- Scourfield, J. (2001). Constructing men in child protection work. Men and Masculinities, 4(1), 70–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X01004001004

- Scourfield, J. (2014). Improving work with fathers to prevent child maltreatment: Fathers should be engaged as allies in child abuse and neglect prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(6), 974–981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.002

- Scourfield, J., Allely, C., Coffey, A., & Yates, P. (2016). Working with fathers of at-risk children: Insights from a qualitative process evaluation of an intensive group-based intervention. Children and Youth Services Review, 69, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.08.021

- Selbekk, A. S., Sagvaag, H., & Fauske, H. (2015). Addiction, families and treatment: A critical realist search for theories that can improve practice. Addiction Research & Theory, 23(3), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2014.954555

- Sieger, M. H. L., & Haswell, R. (2020). Family treatment court-involved parents’ perceptions of their substance use and parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(10), 2811–2823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01743-z

- Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., Boyd, K. A., Craig, N., French, D. P., McIntosh, E., Petticrew, M., Rycroft-Malone, J., White, M., & Moore, L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 374, n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

- Stover, C. S., Carlson, M., & Patel, S. (2017). Integrating intimate partner violence and parenting intervention into residential substance use disorder treatment for fathers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 81, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.013

- Stover, C. S., Carlson, M., Patel, S., & Manalich, R. (2018). Where’s dad? The importance of integrating fatherhood and parenting programming into substance use treatment for men. Child Abuse Review (Chichester, England : 1992), 27(4), 280–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2528

- Su, J., Kuo, S. I.-C., Aliev, F., Guy, M. C., Derlan, C. L., Edenberg, H. J., Nurnberger, J. I., Kramer, J. R., Bucholz, K. K., Salvatore, J. E., & Dick, D. M. (2018). Influence of parental alcohol dependence symptoms and parenting on adolescent risky drinking and conduct problems: A family systems perspective. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(9), 1783–1794. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13827

- Söderström, K., & Skårderud, F. (2013). The good, the bad, and the invisible father: A phenomenological study of fatherhood in men with substance use disorder. Fathering, 11(1), 31–51. https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.1101.31

- The King’s Fund (2021). Integrated care systems explained: Making sense of systems, places and neighbourhoods. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/integrated-care-systems-explained

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(45), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Thor, S., Hemmingsson, T., Danielsson, A.-K., & Landberg, J. (2022). Fathers’ alcohol consumption and risk of substance-related disorders in offspring. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 233(2022), 109354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109354

- Wangensteen, T., Halsa, A. & Bramness, J.G. (2020). Creating meaning to substance use problems: a qualitative study with patients in treatment and their children, Journal of Substance Use, 25(4), 382–386, https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2020.1715497

- Ward, M. R. M., Tarrant, A., Terry, G., Featherstone, B., Robb, M., & Ruxton, S. (2017). Doing gender locally: The importance of ‘place’ in understanding marginalised masculinities and young men’s transitions to ‘safe’ and successful futures. The Sociological Review, 65(4), 797–815. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026117725963

- White, W. L. (2007). Addiction recovery: Its definition and conceptual boundaries. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.015

- Wilcock, A. A. (2002). Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 46(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00174.x

- Yoon, S., Pei, F., Wang, X., Yoon, D., Lee, G., Shockley McCarthy, K., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2018). Vulnerability or resilience to early substance use among adolescents at risk: The roles of maltreatment and father involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86(December 2018), 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.09.020