ABSTRACT

An online survey of 261 Queensland legal practitioners working in sole, micro, small or medium-sized law firms provides valuable insights into their capability to successfully navigate disruption like that experienced during COVID-19. Our results indicated that respondent lawyers demonstrated progressiveness, openness and willingness to engage with innovative approaches, including technology, to build greater capacity within their firms. However, the results from the research identified several overlapping challenges faced by respondents that reduced their capability to adapt to disruption, including being time-poor and difficulty obtaining impartial and trustworthy information and training about emerging forms of disruption.

I. Introduction

In February 2021, the Queensland Law Society (“QLS”) commissioned the University of Southern Queensland and the University of Queensland to investigate the capability of sole, micro, small and medium law firms (“SMSM”) in Queensland, Australia, to meet disruption. This study measured and evaluated SMSM law firms’ ability to navigate sources of potential disruption, including COVID-19, technology and intergenerational change.

The research predominately consisted of an online survey, although some interviews were conducted with practitioners. The online survey was run from December 2021 until October 2022.Footnote1 There were 484 survey respondents, consisting of 207 fully complete and 277 partially complete responses. To the authors’ best knowledge, this is the first time there has been a dedicated study of SMSM law firms’ capability to deal with disruption. Previous studies investigating the effects of disruption in the legal profession include large law firms (Law Society of New South Wales Citation2017; Parker et al. Citation2010; Sako et al. Citation2021; Waye et al. Citation2018). Given the sizeable differences in terms of turnover and available capital for innovation between large and SMSM firms, we hope that focusing on SMSM firms may contribute to a greater understanding of how these firms plan for and manage disruption.

The research team focused on two research questions. First, to measure the self-reported use of technology and practitioners’ perceptions regarding its use within and outside SMSM law firms, as it related to disruption. Second, to identify what is required to improve a firm’s preparedness for disruption. The results gained could then be used to better prepare SMSM law firms in Queensland to build the capability to navigate current and future disruption.

This article proceeds as follows. Part II defines disruption in the legal profession and introduces a taxonomy of disruption. In exploring these four sources of disruption, we review the literature that relates to each. Part III discusses the research methodology and the limitations of our study. Part IV presents the key findings of our study, including respondents’ perception of disruption in the legal profession, their capability to adapt to disruption and factors affecting adaptation. Part V explores the significance of these findings in the context of the legal profession, and Part VI concludes the article.

II. Disruption in the legal profession

Disruption in the legal profession is difficult to define as any definition must include both endogenous and exogenous factors. Rather than an all-encompassing definition, some scholars have focussed on specific forms of disruption. Christensen (Citation1997; Christensen et al. Citation2015) refers to “disruptive innovation” to describe the phenomena where lean market entrants unseat established market players. On the other hand, Pistone and Horn (Citation2016) consider disruption of traditional legal services as most likely coming from market entrants targeting underserved markets, like nonconsumers of legal services, which have been ignored by the embedded incumbents as peripheral to their market. Webley et al. (Citation2019) describe LawTech, “the adaptation and adaption of digital technologies to legal practice”, as a disruptive force within the legal profession and legal services delivery.

We propose to bring these definitions together and expand upon them further to include disruption caused by global pandemics, bushfires and floods. For the purposes of our study, disruption is any force, threat or opportunity that could adversely affect the continuity of a SMSM law firm. Based on the literature and our findings, four types of disruption are most notable: disaster-related disruption, technological disruption, demographic disruption and regulatory disruption.

Disaster-related disruption

Unsurprisingly, given the timing of the study, was the disruption caused by the global pandemic COVID–19. COVID-19 was identified as a key factor driving innovation and the use of legal technology in the UK in a very large online survey of 900 Solicitors Regulation Authority-regulated firms (Sako et al. Citation2021). According to these findings 51 per cent of respondents increased their use of technology to better manange or process work, to interact with clients (48 per cent) and attract new clients (26 per cent) (Sako et al. Citation2021, p. 5). In addition, in February to April 2022, the east coast of Australia was impacted by a series of flood disasters that affected South East Queensland and the Wide Bay-Burnett region. In such events, disruption occurs as physical access to law firm files and resources is restricted or lost entirely.

Technological disruption

The second source of disruption is that caused by rapid technological innovation in legal practice or society generally. This includes generalist technologies that have facilitated new ways of working, including working from home (Thornton Citation2021, p. 254, 255), outsourcing and the commoditisation of legal work, and more specific technologies that include legal analytics, technology-assisted review and other LawTechFootnote2 tools (Caserta Citation2022, p. 325; Webb Citation2022, pp. 516–17, 519–20).

The profession has embraced online legal research, such that it is now standard practice and failing to use free, searchable databases may (arguably) constitute negligence.Footnote3 However, some platforms powered by machine learning (a form of artificial intelligence or AI) are already commercially available to better analyse and classify contractual clauses faster and more accurately than humans (Caserta Citation2022, p. 319; Hunter Citation2020, pp. 1213–21; Thornton Citation2021, p. 254). Large law firms have been actively producing technological innovation within their practices for some time. For example, the multinational law firm Allen & Overy has integrated “Harvey”, an artificial intelligence platform built using Open AI models, into their legal work (as reported by Hearsay Citation2023). LexisNexis, a global provider of legal information (among other things), has recently announced an AI-powered legal information platform that will be available to subscribers.

While our study does not report on the use of free generative AI platforms, it is likely that these are having a disruptive impact on practice. While these may assist in a more equitable legal practice environment, it is crucial for law societies and regulators to consider the ethical implications of the use of this technology now and in the future. Bayamlıoğlu and Leenes (Citation2018) have suggested that this requires the development of appropriate regulations around the use of AI in legal practice now rather than amending inadequate regulatory framework afterwards. The regulatory environment for LawTech was beyond the scope of our research but remains an important aspect of responding to disruption.

Despite all the attention given to AI, Hunter (Citation2020, p. 1201) claims that platform technologies will have the biggest impact on the evolution of the legal profession (see also Caserta Citation2022, p. 319; Sam and Pearson Citation2019). Platform technologies in law will integrate back-office technologies (for example, communication with the client), flexible workforces (contracted lawyers working virtually), and rating systems into one cohesive platform, not unlike what Uber has done for ride-sharing (Hunter Citation2020, p. 1211; Thornton Citation2021, pp. 249–50). The potential impact of platform technologies on the legal profession resonates with members of the Singapore Ministry of Law, who reported in 2018 that the rise of “tech giants” was likely to most impact Singapore’s legal profession during the studies timescale (eighty-three per cent of respondents in Ministry of Law Singapore Citation2020, p. 6).

The rise of “tech giants” and technology platforms in law poses a threat to SMSM law firms, who may be unable to adopt due to the costs involved (Waye et al. Citation2018) or compete against these technologies. This may result in a widening gap between large and SMSM firms, making access to a lawyer more expensive as competition decreases.

Demographic disruption

The Australian legal profession is undergoing a social change, including the changing values of younger lawyers and an aging legal profession (Melville et al. Citation2021). The majority (52.13 per cent) of practitioners in Queensland are now female and aged between 25 and 29 years old (Legal Services Commission Citation2022, p. 7). Younger lawyers are focusing on work/life balance and life beyond work more than previous generations (Caserta Citation2022, p. 328; Jones and Regan Citation2022, p. 17; Thomson Reuters Institute Citation2021, p. 8; Thornton Citation2021, p. 250). This includes more men taking a greater role in raising children, meaning more men and women are juggling their employee and familial responsibilities (Thomson Reuters Institute Citation2021, p. 8; Thornton Citation2021, p. 252). According to a Thomson Reuters study, which provided a snapshot of the Australian legal profession in 2020, a difference in attitudes toward work may explain why lawyers aged 40–60 are willing to work 10 per cent more hours than their younger counterparts (Thomson Reuters Institute Citation2021, p. 8).

Changing attitudes towards work and the long hours demanded by some law firms may be contributing to a concerning attrition rate (Thomson Reuters Institute Citation2021, p. 8; Thornton Citation2021, p. 248) between graduate and senior associate levels in the profession, raising succession issues and creating fierce competition among firms looking for senior staff. In the USA, competition for practitioners with five years of post-admission experience is so fierce that some commentators have called for a fundamental re-think of how they approach talent management in law firms of any size (Jones and Regan Citation2022, p. 16). Rather than offering a “path to partnership”, the key to attracting and retaining young lawyers appears to be offering exceptional training and a range of unique experiences that will serve them in their next professional capacity, whether as a lawyer or in some other role. Firms are encouraged to ensure their lawyers feel valued, appreciated, and given opportunities for personal growth (Jones and Regan Citation2022, p. 20).

While there are no comparable studies of Australian work attitudes in the legal profession, a national survey of solicitors indicates that there has been strong growth in the corporate legal (in-house) and government legal sectors for the last 9 years, which might indicate movement within the sector on the basis of lifestyle choices (URBIS Citation2021, pp. 24–25). Our study did not report particular attrition of junior staff but reflected a concern about the personal impact of overwork and information overload. These were some of the biggest internal threats.

Regulatory disruption

Finally, regulatory disruption will facilitate greater competition in the provision of legal advice, or alter the definition of legal advice such that new market entrants can service the heterogenous needs of the modern legal services market (Hunter Citation2020, p. 1222; see also Webb Citation2022). Dan Hunter (Citation2020, p. 1225) is concerned about the inaction (to date) by the legal profession to new market entrants providing legal services unconstrained by the ethical and professional considerations that apply to lawyers.

This is not the first time the legal profession has faced regulatory disruption. In the 1990s, the Australian legal profession was pushed to establish a national market for legal services (Jones et al. Citation2017, p. 152; Law Council of Australia Citation1994, p. 1). To advance competitiveness in a changing legal market, the Australian legal profession came together in 1994 to develop a “Blueprint for the Structure of the Legal Profession: A National Market for Legal Services” (Jones et al. Citation2017, pp. 148–9; Law Council of Australia Citation1994). The fulfilment of the Blueprint took over 10 years (with many jurisdictional variations). However, statutory amendments across Australia introduced alternative business structures for operating a legal practice, which arguably helped law firms remain competitive (see generally Jones et al. Citation2017, p. 154; Matheson and Favorite Citation2001, p. 580).

In 2007, the Legal Profession Act 2007 (Qld) was amended to allow legal practices to incorporate as a company (“ILP”) or multidisciplinary partnerships (“MDP”).Footnote4 The relevance of introducing these business structures to this study is that the statutory framework underpinning these changes requires principals or directors of an ILP or MDP to implement and maintain “appropriate management systems” (“AMS”), also referred to as “the 10 criteria” (Legal Profession Act Citation2007, p. ss 117(3), 147(2)).Footnote5 If AMS are implemented properly, they embody principles of effective business management that will help firms navigate the challenges of disruption (Parker et al. Citation2010). For example, a “strengths-weaknesses-opportunities-threats” or SWOT analysis may help principals identify and mitigate potential disruptions to their business caused by the loss of key staff (Fortney Citation2014; Queensland Law Society Citation2023), a common gap identified in this research. The regulatory requirement to maintain AMS provides an often overlooked mechanism through which firms can better manage the challenges caused by various disruptions.

III. Research methodology

The survey was administered online to collect a large dataset from participants across Queensland. Survey participants were self-selecting. The survey instrument included more than 80 questions designed to obtain comprehensive feedback necessary to draw meaningful conclusions. Not all questions were presented to all respondents. For example, if a respondent responded negatively to a question, no further questions were presented on this topic. The survey also offered specific questions or answers based on whether the respondent identified as an employee or employer. Most questions allowed respondents to provide additional qualitative data if they chose. Where appropriate, this would be coded into quantitative form. For example, the question on locations of practice contained many references to suburbs, which were manually coded within the categories provided. A set of qualifying questions on the first page of the survey was designed so that only lawyers with a Queensland practising certificate or principal practising certificate in a SMSM law firm completed the survey.

The survey instrument adopted a phenomenological methodology for exploratory investigations to see the world through the respondent’s eyes (Given Citation2008, p. 761). For example, the survey identified perceived barriers, impacts of external and internal threats, and respondent beliefs about the capacity to meet such barriers and threats. The survey questions were based on a literature review and the exploratory analysis of a dataset collected by the QLS during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote6

The survey was pilot tested to ensure clarity, reliability and validity. The pilot showed that the survey took between 35 and 40 min to complete. While the survey length presented challenges to collecting complete responses, the results demonstrate the value of the depth of its coverage. Anticipating that a lengthy survey might lead to high attrition rates, measures were taken to improve the participant experience. For example, questions were presented so respondents could easily select from options rather than manually enter data for common responses.

The survey was extensively promoted through more than 18 legal profession organisations, across digital platforms, including Google, across radio and print media and through legal education institutions to seek participation from across the profession.

The survey results were analysed using a multi-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative methods to gather comprehensive data and insights into SMSM law firms’ capability to deal with disruption in Queensland. The research design aimed to provide a holistic understanding of law firm capabilities under investigation by utilising the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies.

Quantitative analysis was performed using Rstudio (v 2023.06.0 + 421) (R Core Team Citation2023). The survey dataset includes respondents whose “last page” of the survey was equal to or greater than page two, which was the first substantive page of the survey. This excluded respondents who only engaged with the survey superficially to avoid skewing the results. This so-called “tidy” dataset had 261 respondents comprising 47 who abandoned the survey on page two, seven who abandoned the survey on page three, and 207 who completed the entire survey.

Limitations

The study does not purport to be fully representative of the SMSM Qld firms, as described further in the results section below. Where participants are drawn from only an aspect of the profession, their experiences and perspectives cannot be said to entirely represent this sector. Specifically, the authors acknowledge that the results might provide a more positive attitude towards disaster-related, technological, demographic and regulatory disruptions and how they are managed within a firm, as many respondents are principals of firms. Similarly, the format of an online survey might also skew the results in favour of those who are confident with technology. It is also acknowledged that specific issues facing employee lawyers in Queensland SMS firms might not have been identified where there was a small number of those participants.

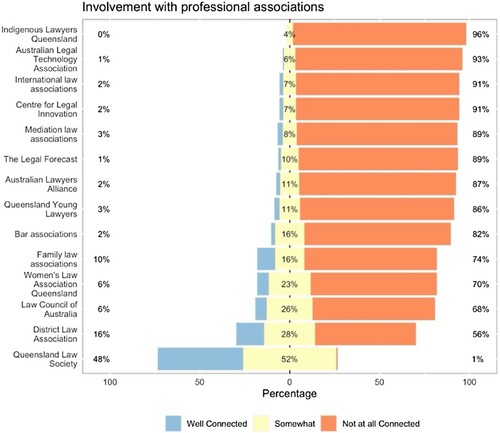

It is acknowledged that there was a strong connection between the respondents and the professional body, the Queensland Law Society (“QLS”). 99 per cent of respondents reported being “somewhat” or “well connected” with the QLS. The QLS had 11,728 “full” members for 2021–2022, but there were 14,637 practising certificates issued for the same period (Queensland Law Society Citation2022, p. 28). The QLSs membership, although extensive (over 90 per cent for private practice), does not include all holders of a practising certificate. Survey questions that asked for reflection on the role of the QLS in providing information or training might, therefore, be unrepresentative of all practising lawyers in Queensland.

Another limitation of this study is that it is only a snapshot in time. This makes it difficult to identify the best approaches and practices employed by Queensland SMSM law firms to navigate disruption successfully. There have been important technological disrupters – such as the free availability of AI Chat GPT – since the data was collected. Determining which approaches and practices are most successful in navigating new disruptions requires additional studies to see how firms have performed over time, controlling for any changes in approaches and practices.

IV. Results

Demographic variables

An analysis using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (“KS”) test was performed to assess the similarity of the geographical locations of the survey respondents against the Legal Services Commission Queensland data (“LSC”)Footnote7 for the entire Queensland legal profession. The null hypothesis (H0) was that the two datasets follow the same distribution. The KS test statistic was D = 0.5, and the p-value was p = 0.3571, to a significance level of α = 0.05. The low p-value result indicates a significant difference between the distributions of the two datasets. Most notably, respondents from Greater Brisbane and rural towns were over-represented in our survey (as a proportion) compared to the Queensland legal profession (see ).Footnote8 The low proportion of survey respondents from the Brisbane CBD is likely due to the high number of large law firms operating in this area, which were beyond the scope of this study.

Table 1. Geographical distribution of all Queensland lawyers and survey respondents.

The average age of survey respondents was older than the profession generally. The survey mode was 36–45 years old (n = 49 respondents), closely followed by 46–55 years old (n = 48 respondents). The modal age for the Queensland profession is 25–29 years old (n = 2489 practitioners). Nationally, the mean age of solicitors is 42 years (URBIS Citation2021). The survey, therefore, more accurately represents the perceptions and attitudes of older practitioners than the Queensland profession generally.

We conducted a Chi-Square Goodness of Fit test to see if the proportions of female and male respondents in our survey were significantly different from the population (see ). The Chi-Square statistic was χ2 = 0.018382, with 1 degree of freedom, and a p-value of p = 0.8922. Since the p-value (0.8922) is greater than the common alpha level of 0.05, we can conclude that there is no significant difference between the observed and expected proportions of men and women in our survey. That is, the distribution of men and women in your survey is consistent with the population proportions.

Table 2. Gender distribution of all Queensland lawyers and survey respondents.

Most respondents (64 per cent, n = 167) were employers, specifically managing principals and principals of their firms, rather than employees (36 per cent, n = 94) at their firms. Most employees were fairly new to their current firm (33.8 per cent of employee respondents had been with their existing firm for 0–1 years, n = 21). Most employee respondents had less than five years post-admission experience (“PAE”) (53.2 per cent, n = 33). Most employer respondents had 10–30 years PAE (65.7 per cent, n = 92) and had been working at their current firm for 10–20 years (25.2 per cent, n = 35). However, there was also a large number of employers who had only been with their current firm for 1–3 years (21.6 per cent, n = 30).

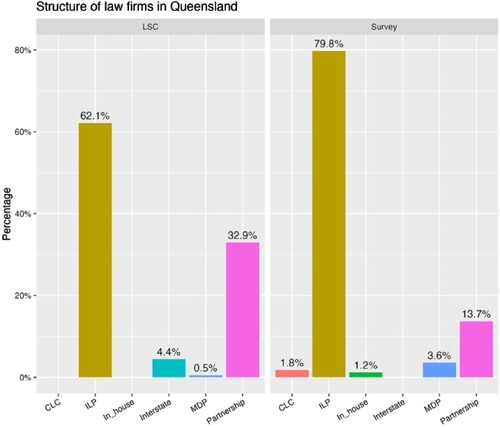

The majority (79.8 per cent, n = 134) of respondents were working in an incorporated legal practice (“ILP”) ( below), which is higher than the Queensland legal profession. According to LSC data, 62.1 per cent (n = 1651) of law firms are ILPs. The number of respondents working in a partnership were underrepresented in our survey, with only 13.7 per cent (n = 23) of respondents from a firm structured as a partnership. The rate of partnerships in the Queensland legal profession is more than double this result (32.9%, n = 875) but will include large law firms that are beyond the scope of this study.

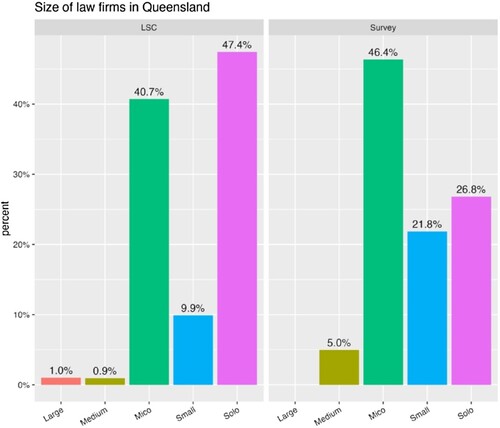

Finally, almost half (121 or 46.4 per cent) of respondents worked in micro firms, defined as 2–5 practising certificates within the firm ( below). This is slightly higher than the proportion of micro firms recorded in the LSC dataset, at 40.7 per cent (or 1082 micro firms in Queensland). Small firms were also overrepresented in our survey at 21.8 per cent (or 57 respondents), compared to 9.9 per cent (or 263 firms) in Queensland. A significant difference exists between the number of respondents from sole practitioner firms in our survey (70 respondents or 26.8 per cent) compared to 47.4 per cent (or 1260 sole practitioners) in the LSC dataset.

In summary, apart from gender, our survey sample was not representative of the population of Queensland lawyers working in SMSM law firms. Older practitioners and those practising in Greater Brisbane and rural locations were overrepresented despite promotion to law associations targeting younger practitioners. Similarly, practitioners from small, micro and medium firms were overrepresented, while sole practitioners were underrepresented in our survey. Therefore, our findings cannot be said to accurately represent the Queensland legal profession or be extrapolated to the Queensland legal profession as a whole, despite extensive efforts to promote the research.

Lawyers’ perception of disruption in the legal profession

Our research revealed that respondents generally feel well equipped to handle future changes in the legal profession, with 141 respondents or 68.7 per cent agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement “I am equipped to deal with future changes in my area of practice”. Similarly, most respondents reported that their firms coped well with the upheaval caused by COVID-19. One hundred and sixty-three respondents (83.5 per cent) reported agreement or strong agreement with the statement that their “law practice has coped well with the changed conditions since March 2020”. Potentially indicating that the disruption caused by COVID-19 is not a common cause of lawyers exiting the profession, 60.5 per cent (or 120 respondents) reported that they were not “considering a change in my legal career in the future”.

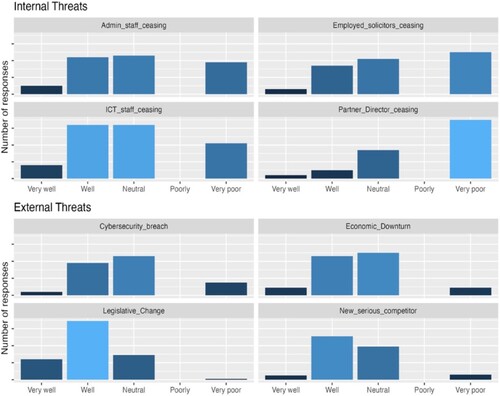

Respondents were asked to rate their ability to deal with various internal and external threats in their practice as a quantifiable indicator of their ability to deal with disruption. The external threats related to cybersecurity, economic downturn, legislative change, and a new serious competitor. The internal threats related to the sudden loss of various staff, including a partner or director, legal and administrative staff. Interestingly, the data revealed respondents felt more confident in responding to external threats than internal threats. Specifically, 47.1 per cent of responses (n = 306) indicated they could deal “very well” or “well” with one or more external threats, while only 20.7 per cent of responses (n = 124) claimed the same for internal threats. These results are mirrored at the other end of the scale, with 20.3 per cent of responses (n = 132) reporting an inability to deal with one or more external threats (i.e. “poor” or “very poor”), compared to 56.6 per cent (n = 338) of responses were categorised “poor” or “very poor” for internal threats.

The ability to deal with internal and external threats was filtered by respondents’ status as an employer (including sole practitioners). shows that employers felt more confident dealing with external threats, such as a new serious competitor or an economic downturn, than an internal threat, such as losing a partner/director.

An ordinal logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the relationship between the type of threat (internal vs external) and the ordinal rating scale (“Very poor”, “Poor”, “Neutral”, “Well”, and “Very well”). The coefficient for internal threats was statistically significant (p < 0.05), suggesting a small effect on the odds of receiving a higher rating. However, the magnitude of the coefficient was extremely small (3.057e-15), indicating limited practical significance. Thresholds between rating categories were also statistically significant, illustrating the boundaries where transitions between adjacent rating levels occur. These results imply that while the type of threat may have a statistical impact on the rating, its practical relevance may be minimal in the real world.

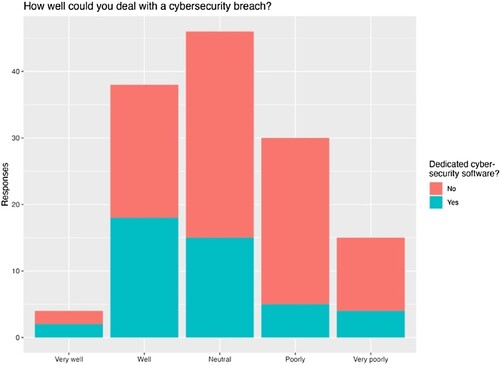

Employers’ ability to deal with a cybersecurity attack “well” was intriguing. To better understand this result, all respondents’ answers to the cybersecurity attack question were compared against the question asking whether the firm uses dedicated cybersecurity software (see ). The theory was that cybersecurity software might boost respondents’ confidence in dealing with a cybersecurity attack. Fisher's Exact Test was employed to evaluate this relationship due to the low number of respondents (less than five) in the “very well” and “very poorly” (those with cybersecurity software only) categories. The results of the analysis yielded a p-value of 0.08661. This result indicates that there was not a statistically significant association between employers’ level of confidence and the use of dedicated cybersecurity software (p = 0.08661) at the conventional alpha level of 0.05. The fact that the p-value does approach the commonly used threshold for statistical significance (p < 0.05) does, however, suggest that significant findings might emerge with a larger sample size or different categorisations.

Lawyers’ capability to adapt to disruption

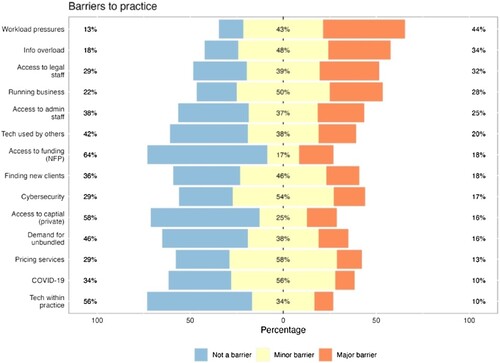

To assess firms’ capability to respond to disruption, fourteen potential barriers were identified (based on the literature review and QLS call dataset) (see Hart Citation2017) and respondents were asked to rate each as either a major barrier, minor barrier or not a barrier to practice. These barriers are either a direct source of disruption, such as cybersecurity threats, technology used by others and COVID-19, or impact a firm’s capability to deal with disruption, such as access to capital, workload pressures and the administrative requirements of running a business.

(below) shows that the most common “major barriers” had nothing to do with technological or disaster-related disruptions. Rather, the “major barriers” to practice were those that drain human capital, namely, workload pressures (44 per cent, n = 87), information overload (34 per cent, n = 63), access to legal staff (32 per cent, n = 40) and tasks associated with operating a business (28 per cent, n = 37). The use of technology by “others”, including courts and other law firms, was a minor barrier (38 per cent, n = 70). More common “minor barriers” include pricing of legal services (58 per cent, n = 108), cybersecurity (54 per cent, n = 68) and COVID-19 (56 per cent, n = 108). The challenge of pricing legal services and COVID-19 were the two barriers with the highest response rate (n = 108), meaning many respondents wanted to report that both are minor barriers to their delivery of legal services.

While technology within the firm was not considered a barrier, 62 per cent of responses (n = 252) identified data security, financial cost and difficulties in evaluating new technology as a concern when selecting, investing in and using new technologies in their law practice. This is evident in the high proportion of respondents (40 per cent or n = 163) who reported concerns about evaluating new technologies and data security within their firm.

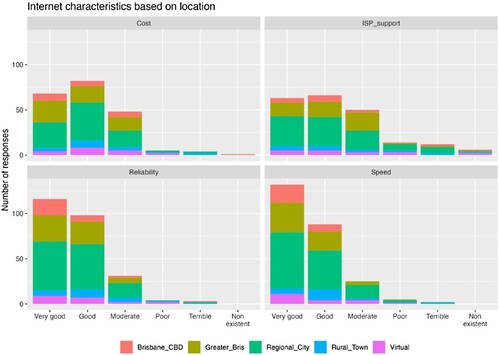

Internet speed, cost, and reliability were not issues of concern for most respondents (), including those located in regional or rural locations. An investigation into the relationship between location of practice and the rating given to the Internet’s characteristics was conducted using ordinal logistic regression to assess how location (the independent or “predictor” variable) might influence respondents’ ratings (the dependent or “outcome” variable). The regression results suggest that the relationship between location and perceived value is not statistically significant. The model coefficients for locations outside “Brisbane_CBD” (the reference category) were positive but small (e.g. the coefficient for “Greater_Bris” was 0.1006), and the associated standard errors were large (e.g. SE = 0.7166 for “Greater_Bris”), resulting in t-values (e.g. t = 0.1403 for “Greater_Bris”) that do not indicate statistical significance. Moreover, the ordinal logistic regression model's fit to the data, as reflected in the Residual Deviance (169.591) and AIC (183.591), does not demonstrate a strong predictive power. Finally, the dataset contained 26 observations with missing values, which may affect the robustness and generalisability of the results. So, based on our data, there is no strong evidence of a relationship between the geographical location of a firm and how respondents rated the characteristics of their Internet, which suggests that the “tyranny of distance” may have been overcome with respect to access to the Internet.

Improved access to the Internet has not necessarily translated to improved efficiencies and productivity within SMSM law firms in our study. A high percentage of respondents’ computer use was spent on administrative tasks, such as scheduling appointments (81 per cent reported “all the time” or n = 198) and email (95 per cent “all the time” or n = 235).

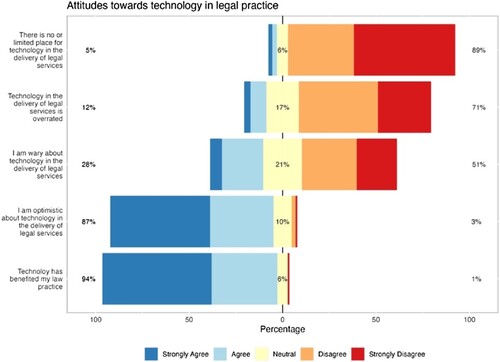

Our survey found that most practitioners had a relatively progressive attitude towards technology coupled with a degree of wariness. Respondents were asked questions regarding their attitudes towards technology in legal practice. As seen in below, 94 per cent of responses (n = 221) acknowledged the positive benefits technology has had on their practice, with 89 per cent (n = 211) rejecting the view that there is “no or little place for technology in the delivery of legal services”. Eighty-seven per cent of responses (n = 206) reported feeling “optimistic about the use of technology in the delivery of legal services”. However, 49 per cent of responses (n = 116) felt wary or neutral about the use of technology in law.

Factors affecting lawyers’ adaptation

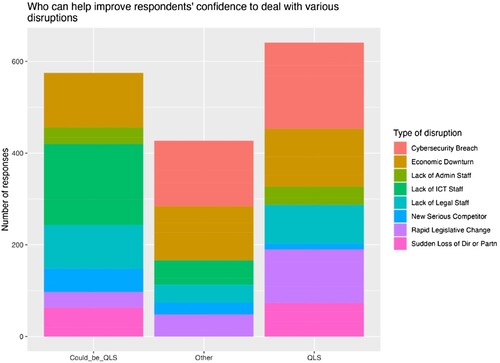

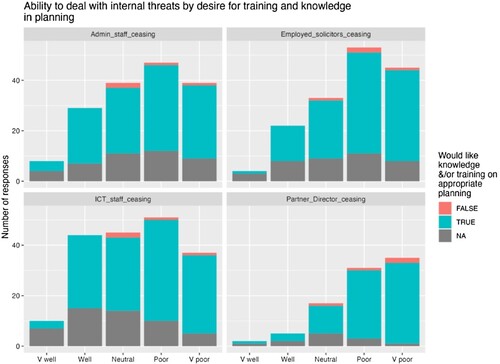

Many Queensland SMSM law firms are already employing one key approach to navigating disruption successfully: alternative business structures. Over 79 per cent (n = 134) of firms reported in our study were incorporated legal practices (“ILPs”). Another key variable affecting lawyers’ ability to deal with disruption is access to information and training. When asked what respondents needed to increase their confidence in dealing with specific disruptive events, respondents generally selected one or more options related to training or increased knowledge or guidance in the relevant field. In fact, a statistically significant relationship (Fisher's Exact Test yielded a p-value of 0.03759)Footnote9 exists between employer respondents desire for more information and training about effective business planning and their ability to deal with the internal threats at the conventional alpha level of 0.05 (see below). in the Appendix details all the support respondents felt would help them better deal with the following disruptions.

Figure 8. Respondents’ ability to deal with internal threats by their desire for training and knowledge to better deal with the internal threats.

When respondents were asked “what would help increase [their] confidence in dealing with” various disruptions, those answers that specifically named their law society, the QLS, rated higher than other potential options, including those that did not name a training provider (see ). This suggests that many respondents trust the information and training from their law society and look to their law society to provide the knowledge and skills to better manage disruption, especially in areas that are unique to the legal profession, such as cybersecurity and rapid legislative change. However, this relationship was not statistically significant based on an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The ANOVA result showed there were no statistically significant differences (F(2, 41) = 0.5, p = 0.61) in the mean values of the total number of responses (“n”) across the different sources of assistance (e.g. “QLS”, “Could_be_QLS” and “Other”). Nevertheless, we would argue that the results in do suggest a preference for the QLS to help improve their confidence in dealing with various disruptions, but not to a statistically significant level.

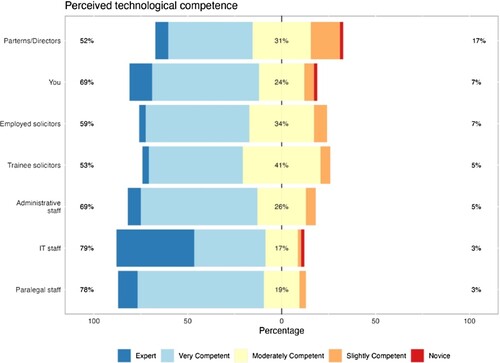

Another factor affecting practitioners’ ability to respond to disruption is the technology competency of others in the firm. This is especially relevant in the 74 per cent (n = 187) of firms that use practice management software (“PMS”). The fact that all PMS used by respondents were cloud-based (or had a cloud-based option) may explain why 91 per cent (n = 174) of these practitioners did not have any trouble accessing their files during the lockdowns and work-from-home directives during COVID-19.Footnote10 As one may expect, given these findings, many respondents rated their technological competency highly. Specifically, 69 per cent of respondents (n = 40) rated their technological competency as “expert” or “very competent”. However, other staff within respondents’ firms were generally rated lower, with the exception of IT staff. As per below, 34 per cent of respondents (n = 20) rated employed lawyers (<5 yrs PAE) as “moderately competent” with technology. Similarly, 41 per cent of respondents (n = 24) rated trainee lawyers as only “moderately competent” with technology. Based on these findings, a factor affecting firms’ adaptation and adoption of new technologies (as one source of potential disruption) is possibly the technology competency of staff.

A final factor affecting lawyers’ adaptability is their connection with professional associations. The link between adaptability and connection with professional associations is based on the previous finding (discussed above) that practitioners want information and training from trustworthy and independent sources to help them adapt to current and future disruptions. Law societies and other professional associations are well-placed to provide such information; however, the practitioner must be engaged with these associations in the first place.

Our survey asked respondents how connected/engaged they were with 14 professional associations related to the legal profession in Queensland. As previously noted, 99 per cent of our survey respondents reported being “somewhat” or “well connected” with the QLS ( below). It is noteworthy, however, that respondents’ engagement with professional organisations was largely confined to the QLS. Combining all “well-connected” and “somewhat” connected responses (n = 462), this was dwarfed by all the “not at all connected” responses (n = 1512) across all associations. Clearly, very few respondents are involved with more than one professional association.

V. Discussion

Our study aimed to assess SMSM Queensland practitioners’ use and perceptions of technology in the legal profession and how firms could become more prepared for disruption. Our findings refute the stereotype that lawyers and law firms (especially those in rural locations) are technology laggards (see, for example, Shankar and Forbes Technology Council Citation2021). This is consistent with previous research, with Waye et al. (Citation2018, p. 233) finding that “Australian law firms are not bastions of resistance to change or myopically wedded to tradition”. Our survey respondents demonstrated a similar progressiveness and willingness to be innovative, including through the use of technology.

Our research found that, in general, Queensland SMSM law firms consider themselves relatively well-placed to handle future disruptions to their practice. Most practices coped well during COVID-19, and respondents felt confident about dealing with future disruptions. This is, however, based on respondents’ own self-assessment, which may be subject to self-serving bias (see Blackwood et al. Citation2003, p. 1076).Footnote11 The potential for this bias to influence respondents’ answers may be higher given that the research was funded by their professional body, the QLS. As many respondents were more senior and may have been QLS members for decades, there may have been a reluctance to share the extent of the challenges they faced through COVID and other disruptions.

It is further acknowledged that the data collected in this project pre-dated the release of free, easily accessible generative AI (e.g. Chat-GPT 3) and subsequent versions that are impacting legal practice. Further research would be needed to ascertain what impact this cheap and accessible technology has and will have on SMSM law firms. It is likely that this technology is being incorporated into practice, as illustrated by our respondents’ positive attitudes towards the use of technology in legal practice. However, there remained a degree of wariness regarding the use of technology in delivering legal services, which may only increase with new technologies on offer.

The wariness reported by respondents may be due to the legal and ethical duties imposed on lawyers, which are technology agnostic. It may be that as practitioners understand how the technology works and its limitations, the unease may reduce or dissolve entirely. Some of this learning may come from disciplinary hearings, not unlike the one recently heard in the USA involving a senior practitioner who filed submissions with the court that were drafted by ChatGPT and included fictional citations (Carrick and Kesteven Citation2023). In the subsequent judgment, the court did not admonish the use of ChatGPT but rather the lack of oversight and review by the lawyer before filing (Carrick and Kesteven Citation2023). Such decisions will help practitioners and the legal fraternity to understand how new technologies, like ChatGPT, can be safely and responsibly adopted into their practice.

A significant and unexpected finding was that many respondents reported feeling more confident addressing external threats, over which they have little control, than internal threats. For example, the loss of a partner/director is within a firm’s ability to manage through succession planning, staffing and continuity of practice. Although a principal has more control over the internal environment, they felt less confident handling it than external threats they have less control over. This finding suggests that employers may have an inverse perception regarding their capability to plan for and manage disruptive events. Lawyers perceive external sources of disruption as something within their control, while internal sources of disruption are discounted or ignored. This indicates scope for practitioners to engage in greater business and succession planning to ensure that the sudden loss of staff can be managed effectively to minimise disruption. For ILPs (and multidisciplinary practices (“MDPs”)), it is the statutory requirement to implement and maintain appropriate management systems (“AMS”), which can assist in successfully navigating this and other forms of disruption (Legal Profession Act 2007 (Qld) s 117(3)) through a risk-based regulatory approach.

Three key barriers to practice were identified as affecting practitioners’ or firms’ ability to address the challenges posed by disruption. These were workload pressures, information overload and tasks associated with operating a business. Although presented as distinct barriers, they overlap and have the potential to compound. As previously reported, our study found that eighty-one per cent of respondents (n = 198) use their computer to schedule appointments “all of the time”. But scheduling and rescheduling meetings is time-consuming and takes lawyers away from advising clients, which creates workload pressures. Especially when various platforms now exist that largely automate the process of scheduling (and rescheduling) appointments for online, face-to-face or telephone appointments, including sending reminders and follow-up messages for a comparatively small monthly fee. For busy practitioners, it is often a lack of awareness of such services and the lack of time to properly vet such platforms that reduce the time available for planning and capacity-building activities, including managing future disruptions.

Nevertheless, these are not the traditional barriers to practice that one may expect. In Waye et al.’s (Citation2018, p. 232) study of innovation in the Australian legal profession, the “very significant” and “critical” barriers to innovation concerned the high cost of innovation projects, the regulation of the legal profession and access to skilled staff. These barriers are similar to those identified in the 2021 report for the Solicitors Regulation Authority in the UK (Sako et al. Citation2021). According to Sako et al. (Citation2021, p. 4), a lack of financial capital, a lack of staff with appropriate expertise, and regulatory uncertainty were the most significant barriers to legal technology and innovation. Legal (or regulatory) barriers and market factors have been identified as barriers in the Amercian legal service market (Sheppard Citation2015, p. 1813, 1824, 1906). In a qualitative study with 53 practitioners from different parts of the world, Michalakopoulou et al. (Citation2023) identified six barriers to innovation, including political implications and organisation transitions (e.g. Brexit); human factors and culture; client and market considerations; legal processes; education; and technology itself. In earlier studies, speed, reliability or cost of the internet were barriers to practice, especially for practitioners located in rural areas (Senate Legal and Constitutional References Committee Citation2004, p. ch 6; but see Wallace Citation2008, p. 9 noting the improvements to the Internet infrastructure; Hart Citation2011, p. 262, Citation2014, p. 48, Citation2017, p. 10; Law Council of Australia Citation2017, pp. 20–22).

Although access to funding (both private and not-for-profit) and access to legal and administrative staff were presented as potential barriers in our study, they were rated as either “not a barrier” or a “minor barrier” which contradicts some of the previous research on this topic. Further research is necessary to confirm if the barriers we identified for SMSM law firms remain different to those identified in other studies. It may be that as Queensland is a relatively small market compared to the national (Waye et al. Citation2018) or UK (Sako et al. Citation2021) markets that local economic and social factors insulated our survey respondents from the barriers others have identified as most exigent.

Another interesting finding in our study was the perceived competence with which respondents felt they could deal with a cybersecurity attack. Further research is required to understand this result properly. Respondents did rate themselves highly for technological competency, so it is possible they possess the necessary technical skills. However, given the challenges that well-resourced companies (notably Optus, Medibank etc.) and cybersecurity professionals have in managing cybersecurity threats, this finding may indicate a degree of hubris or overconfidence among respondents. This may indicate a significant vulnerability among SMSM law firms in Queensland, especially given the increased risk of cybersecurity crime reported by the UK Law Society of England and Wales post-COVID-19 (Law Society of England and Wales Citation2020; Ministry of Law Singapore Citation2020, p. 11; Mitigo Citation2022).

This highlights the potential value that law societies can offer their membership or the role that LawTech consultants can play in helping firms to better manage disruption. Specifically, providing independent information from a trusted source (i.e. law society or advisor) could greatly assist time-poor practitioners in adopting new technology (like dedicated cybersecurity software) to overcome disruption or build greater capacity within their firm. Impartiality is crucial. Practitioners want to learn about new tools from someone who is not trying to “sell” them a licence. The conflict of interest in the sales process necessitates a detailed analysis and review, for which most respondents do not have the time. While there is no substitute for such a review, our data suggest that practitioners would appreciate the guidance and tools to know what they should be most concerned about. Assuming law societies or other professional bodies raise awareness about current or future disruptions, our findings suggest that practitioner members would be receptive to targeted and actionable information.

VI. Conclusion

The Queensland legal profession is experiencing changes to its operating environment. The Legal Profession Act 2007 (Qld), which regulates the profession and determines who can offer legal services, was previously amended to enhance the profession's ability to handle increased competition, ensure consistency, and facilitate lawyer mobility. This is evidence of the profession’s track record of adapting to change while upholding ethical standards and protecting consumer interests. However, the rate and nature of disruption is changing. The challenge posed by COVID-19 to businesses, including law firms, was unprecedented in modern times. Advances in technology, and LawTech specifically, promise to disrupt the practice of law in a way not entirely dissimilar from the effect Uber had on the taxi industry.

This study has found that most lawyers working in small firms are innovative or want to innovate but generally lack the time to plan and prepare for the future. A key finding of this study is that practitioners want impartial information from trustworthy stakeholders. This creates a much-needed value proposition for law societies and other professional associations, who can access expertise and resources through their committees to support training and planning activities. Many respondents would benefit from educational sessions about the latest technological developments relevant to legal practice and training to help avoid common mistakes in selecting new platforms. This can include more advanced aspects of LawTech, such as predictive analytics and how to appropriately use increasingly available generative AI possibilities, but also include non-legal specific technologies, such as automating the scheduling of appointments and other administrative tasks. Industry stakeholders, such as law societies and other law associations, can also apply their expertise to scan the environment for emerging sources of disruption and then communicate approaches and practices to deal with such threats to its membership.

Time is the most precious resource for practitioners in SMSM law firms. This study has revealed that technology can either help give time back to a lawyer if technology is used effectively (capacity building) or can steal time, making it harder to engage in strategic planning. However, there is an awareness, at least within the leadership of such firms, that technology and a willingness to adapt are the way of the future.

This work was commissioned and funded by the Queensland Law Society under the Research Project on Queensland Law Firms’ Capability to Meet Disruption (Reference ID: QLS2020R.1).

Acknowledgment

I want to acknowledge the anonymous reviewer whose helpful comments and suggestions improved the quality of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All survey data collected were non-identifiable. With the interviewee’s permission, the results from some of the interviews were published as short op-ed style articles in the QLS Proctor publication, in part to encourage the completion of the survey. The research was carried out in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council Standards. Ethics approval was granted for the Project: Ethics Approval # H21REA121P1 (23 April 2021). The application was made through the University of Southern Queensland and The University of Queensland’s Ethics Committees.

2 According to the Law Society of England and Wales, “LawTech” is the group of “technologies that aim to support, supplement or replace traditional methods for delivering legal services, or that improve the way the justice system operates”: see https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/campaigns/lawtech/guides/introduction-to-lawtech.

3 This overlaps with lawyers’ ethical duty of competence articulated in r 4.1.3 in the Australian Solicitors Conduct Rules (2012).

4 See Legal Profession Act 2006 (ACT); Legal Profession Act 2004 (NSW), superseded by Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Act 2014 (NSW); Legal Profession Act 2006 (NT); Legal Practitioners (Miscellaneous) Amendment Act 2013 (SA); Legal Profession Act 2007 (Tas); Legal Profession Act 2004 (Vic), superseded by Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Act 2014 (Vic); Legal Profession Act 2008 (WA).

5 Appropriate management systems include competent work practices to avoid negligence; effective, timely and courteous communication; timely delivery, review and follow-up of legal services to avoid delay; acceptable processes for liens and file transfers; shared understanding and appropriate documentation of retainer, covering costs disclosure, billing practices and termination of retainer; timely identification and resolution of conflicts of interests; records management; compliance with regulatory authorities such as the Legal Services Commissioner, the Queensland Law Society, courts and costs assessors; supervision of the practice and staff; and avoiding failure to account for trust monies

6 The QLS call dataset consisted of the typed notes from QLS employees telephone calls made to QLS members during the pandemic. A thematic and semantic analysis of the QLS call dataset was useful in designing survey questions.

7 The LSC is an independent statutory body, which has the power to regulate the legal profession.

8 Greater Brisbane included Ipswich and Brisbane suburbs. “Regional city” was defined as having populations over 23,000 and included: Gold Coast, Townsville, Cairns, Rockhampton, Toowoomba, Gladstone, Mackay, Bundaberg, Warwick and Mount Isa. “Rural towns” was defined as populations less than 23,000 and included: Mareeba, Innisfail, Dalby, Atherton, Biloela, Emerald, Goondiwindi, Kingaroy and Roma.

9 Fisher’s Exact Test was employed due to the low number of observations in the “very well” (zero) and “well” (one) categories for respondents who did not want training on business planning. Such low frequencies in this dataset invalidate the assumptions underlying the chi-squared test.

10 Access to files was rated “very well” or “well”. Those who rated their access to files during COVID-19 as “average” to “very poor” were 8.4 per cent (n = 16) of responses.

11 Thanks to the anonymous reviewer for highlighting this.

References

- Bayamlıoğlu, E. & Leenes, R. (2018) The “rule of law” implications of data-driven decision-making: a techno-regulatory perspective, Law, innovation and technology, 10(2), pp. 295–313. doi:10.1080/17579961.2018.1527475.

- Blackwood, N. J., Bentall, R. P., ffytche, D. H., Simmons, A., Murray, R. M. & Howard, R. J. (2003) Self-responsibility and the self-serving bias: an fMRI investigation of causal attributions, NeuroImage, 20(2), pp. 1076–1085. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00331-8.

- Carrick, D. & Kesteven, S. (2023) “Use with caution”: how ChatGPT landed this US lawyer and his firm in hot water, ABC News, 24 June. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-06-24/us-lawyer-uses-chatgpt-to-research-case-with-embarrassing-result/102490068, accessed 26 June 2023.

- Caserta, S. (2022) The sociology of the legal profession in the digital age, International Journal of the Legal Profession, 29(3), pp. 319–334. doi:10.1080/09695958.2021.1920417.

- Christensen, C. M. (1997) The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail (Boston, MA, Harvard Business School Press (The management of innovation and change series).

- Christensen, C. M., Raynor, M. E. & McDonald, R. (2015) What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review, 1 December. Available at: https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation, accessed 16 March 2023.

- Fortney, S. (2014) The role of ethics audits in improving management systems and practices: an empirical examination of management-based regulation of law firms, St. Mary’s Journal on Legal Malpractice and Ethics, 4(1), pp. 112–148.

- Given, L. M. (2008) The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (London, Sage Publications (Encyclopedia of qualitative research methods).

- Hart, C. (2011) Sustainable regional legal practice: the importance of alliances and the use of innovative information technology by legal practices in regional, rural and remote Queensland, Deakin Law Review, 16(1), pp. 225–263.

- Hart, C. (2014) The Prevalence and Nature of Sustainable Regional, Rural and Remote Legal Practice. PhD Thesis (University of Southern Queensland).

- Hart, C. (2017) “Better justice?” or “shambolic justice?”: governments’ use of information technology for access to law and justice, and the impact on regional and rural legal practitioners, International Journal of Rural Law and Policy, 1, pp. 1–21.

- Hearsay (2023) Magic circle firm rolls out “Gamechanger” ChatGPT-type platform, 7 March. Available at: https://www.hearsay.org.au/magic-circle-firm-rolls-out-gamechanger-chatgpt-type-platform/, accessed 16 March 2023.

- Hunter, D. (2020) The death of the legal profession and the future of law, University of New South Wales Law Journal, 43(4), pp. 1199–1225.

- Jones, J. W., Davis, A. E., Chester, S. & Hart, C. (2017) Reforming lawyer mobility—protecting turf or serving clients? The Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics, 30(1), pp. 125–193.

- Jones, J. W. & Regan, M. C. Jr (2022) Report on the State of the Legal Market: A Challenging Road to Recovery (Washington, Georgetown University Law Center on Ethics and the Legal Profession).

- Law Council of Australia (1994) Blueprint for the Structure of the Legal Profession: A National Market for Legal Services, Final Report (Hobart, LCA Law Practice Management Section).

- Law Council of Australia (2017) The Justice Project: RRR Australians. Consultation Paper. Available at: https://www.lawcouncil.asn.au/files/webpdf/Justice%20Project/Consultation%20Papers/RRR%20Australians.pdf.

- Law Society of England and Wales (2020) Written Evidence Submitted by the Law Society of England and Wales, United Kingdom Parliament. Available at: https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/17603/html/, accessed 3 July 2023.

- Law Society of New South Wales (2017) The Future of Law and Innovation in the Profession. Commission of Inquiry (Sydney, Law Society of New South Wales). Available at: https://www.lawsociety.com.au/sites/default/files/2018-03/1272952.pdf.

- Legal Profession Act (2007) Qld.

- Legal Services Commission (2022) Annual Report 2021–2022 (Queensland, Legal Services Commission).

- Matheson, J. H. & Favorite, P. D. (2001) Multidisciplinary practice and the future of the legal profession: considering a role for independent directors, Loyola University Chicago Law Journal, 32(3 (Spring)), p. 577.

- Melville, A., Caines, V. & Walker, M. (2021) The grey zone: the implications of the ageing legal profession in Australia, Legal Ethics, 24(2), pp. 141–170. doi:10.1080/1460728x.2022.2027118.

- Michalakopoulou, K., Bamford, D., Reid, I. & Nikitas, A. (2023) Barriers and opportunities to innovation for legal service firms: a thematic analysis-based contextualization, Production Planning & Control, 34(7), pp. 604–622. doi:10.1080/09537287.2021.1946329.

- Ministry of Law Singapore (2020) The Road to 2030: Legal Industry Technology & Innovation Roadmap Report, Final Report. Available at: https://www.mlaw.gov.sg/files/news/press-releases/2020/10/Minlaw_Tech_and_innovation_Roadmap_Report.pdf.

- Mitigo (2022) Why Your Cybersecurity Measures May No Longer be Enough, The Law Society. Available at: https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/topics/small-firms/cybersecurity-trends-for-small-firms-in-2021, accessed 14 July 2023.

- Parker, C., Gordon, T. & Mark, S. (2010) Regulating law firm ethics management: an empirical assessment of an innovation in regulation of the legal profession in New South Wales, Journal of Law and Society, 37(3), pp. 466–500.

- Pistone, M. R. & Horn, M. B. (2016) Disrupting Law School: How Disruptive Innovation will Revolutionize the Legal World, White Paper (Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation). Available at: https://www.christenseninstitute.org/publications/disrupting-law-school/.

- Queensland Law Society (2022) Annual Report 2021–22, Annual Report.

- Queensland Law Society (2023) Practice Management Course Handbook (Brisbane, Draft).

- R Core Team (2023) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria, R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Sako, M., Parnham, R., Armour, J., Rodgers, I. & Qian, M. (2021) Technology and Innovation in Legal Services, Final Report (Solicitors Regulation Authority, July 2021). Available at: https://www.sra.org.uk/sra/research-publications/technology-innovation-in-legal-services/.

- Sam, S. & Pearson, A. (2019) Community legal centres in the digital era: the use of digital technologies in Queensland Community Legal Centres, Law, Technology and Humans, 1(2019), pp. 64–79. doi:10.5204/lthj.v1i0.1305.

- Senate Legal and Constitutional References Committee (2004) Legal Aid and Access to Justice (Parliament of Australia). Available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Legal_and_Constitutional_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2002-04/legalaidjustice/report/contents.

- Shankar, A. & Forbes Technology Council (2021) The Pandemic Might be the Tech Disruptor The Legal Industry Needs, Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2021/02/08/the-pandemic-might-be-the-tech-disruptor-the-legal-industry-needs/, accessed 16 August 2023.

- Sheppard, B. (2015) Incomplete innovation and the premature disruption of legal services, Michigan State Law Review, 2015(5), pp. 1797–1910.

- Thomson Reuters Institute (2021) Stellar Performance: Skills and Progression Mid-Year Survey. Available at: https://insight.thomsonreuters.com.au/legal/resources/resource/2021-australia-state-of-the-legal-market-report.

- Thornton, M. (2021) Legal professionalism in a context of Uberisation, International Journal of the Legal Profession, 28(3), pp. 243–263. doi:10.1080/09695958.2021.1901715.

- URBIS (2021) 2020 national profile of solicitors (Sydney, Law Society of New South Wales).

- Wallace, A. (2008) “Virtual justice in the bush”: the use of court technology in remote and Regional Australia, Journal of Law, Information and Science, 19, pp. 1–21.

- Waye, V., Verreynne, M. & Knowler, J. (2018) Innovation in the Australian legal profession, International Journal of the Legal Profession, 25(2), pp. 213–242. doi:10.1080/09695958.2017.1359614.

- Webb, J. (2022) Legal technology: the great disruption? in: R.L. Abel, H. Sommerlad, O. Hammerslev & U. Schultz (Eds) Lawyers in 21st Century Socities: Vol 2 – Comparisons and Theories (Oxford, Hart Publishing), pp. 515–540.

- Webley, L., Flood, J., Webb, J., Bartlett, F., Galloway, K. & Tranter, K. (2019) The profession(s)’ engagements with LawTech: narratives and archetypes of future law, Law, Technology and Humans, 1(1), pp. 6–26. doi:10.5204/lthj.v1i0.1314.

Appendix

Table A1. Respondents' selections for the types of support they would need to feel more confident when handling the following disruptions.