Abstract

We used a two-phased mixed methods study with an explanatory sequential design to understand how frequently paramedics attend patients who, on paramedic assessment with the Gold Standards Framework Proactive Identification Guidance, are end-of-life and have advance care planning. We subsequently explored paramedic views on paramedic screening of patients to assess if they are end-of-life and onward referral to their General Practitioner for advance care planning. Paramedics screened and recorded 14.9% of patients as end-of-life and 44.3% of these patients were assessed to have no advance care plan in place. When paramedics screened patients and they did have an advance care plan in place, 36.8% had only a Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Paramedics found using the Gold Standards Framework Proactive Identification Guidance to screen patients for end-of-life status useful and straightforward and considered themselves well-placed to complete this task. Future research is required to address the practicalities of implementing a paramedic screening and referral tool for end-of-life care that results in the intended outcome of supporting effective advance care planning.

Background

There is a growing need for end-of-life (EOL) care. The UK population is expected to reach 73 million by 2041, and the population is ageing with 20.7% expected to be aged over 65 years by 2027; an increase from 18.2% in 2017. Annual deaths are expected to rise by 25% by 2040, with increases in deaths due to dementia, cancer and multimorbidity.Citation1

There are inequalities in access to EOL care. For example, patients dying from non-malignant diseases such as chronic obstructive airway disease are less likely to have access to EOL care than patients with cancer.Citation2 Advance care planning is a ‘voluntary process of person-centred discussion between an individual and their care providers about their preferences and priorities for their future care, while they have the mental capacity for meaningful conversation about these’.Citation3 An Advance Care Plan (ACP) can be, amongst other things, an Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment, or a much more detailed statement of wishes and preferences such as a Treatment Escalation Plan or Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment.Citation4 An ACP should tailor care to an individual’s wishes, support them to die in their place of choice and allow better preparation and fewer crisis hospital admissions via the Emergency Medical (ambulance) Services (EMS).Citation5 The lack of ACPs among EOL patients may be related to time pressures on General Practitioners (GPs), difficulties for GPs in prognosticating for patients with non-malignant conditionsCitation6 and/or to patients not consulting with their GP.Citation7 The role of EMS in the proactive identification of patients who may be approaching EOL has yet to be developed.Citation8,Citation9 Previous research indicates that paramedics are well-placed to identify patients who would benefit from an ACP and refer them to their GP practice for review.Citation7 A referral from a paramedic could flag a patient to the GP practice and initiate a telephone consultation or home visit by a member of the practice staff, such as a practitioner or care coordinator who can begin the ACP process.

This research investigated the potential to enhance the role of UK paramedics in the promotion and uptake of advance care planning. The primary aim was to understand how frequently paramedics attend patients who, on paramedic assessment with the Gold Standards Framework Proactive Identification Guidance (GSFPIG),Citation10 are thought to be in their last year of life and had an ACP in place. The GSFPIGCitation10 is an established and evidence-based screening tool, used in many settings, to identify patients nearing EOL. The GSFPIG is made up of three steps for the clinician: asking themselves if they would be surprised if a patient were to die in the next year; checking the patient against a list of general indicators of decline; assessing the patient against specific clinical indicators. Additional aims were to explore paramedic perspectives on the usability and acceptability of the GSFPIG in identifying EOL patients, and the potential for paramedic referral of EOL patients to their GP for advance care planning.

Methods

We used a mixed methods phenomenological study with an explanatory sequential design. The rationale for this design was that we aimed to collect quantitative data where paramedics screened the patients they attended, assessing end-of-life status and the presence of ACP (Phase A) so that we could establish the current situation regarding paramedic attendance to EOL patients and ACP presence in this patient group. We then aimed to explore paramedic experiences and the findings of Phase A alongside paramedic views on expanding their role in screening for EOL status and referring to General Practice for an ACP where indicated (Phase B).

Phase A – Procedure and data analysis

Paramedics from one UK EMS provider organisation (NHS ambulance trust) in the South West of England were invited via professional networks, internal communications and social media to express an interest in participating in the study during July 2022. The participating ambulance service covers an area of 20 000 square miles and serves a resident population of 5.5 million people.Citation11 Paramedics who expressed an interest in participation were then provided with further information about the study and invited to consent to participate. During August and September 2022 participants were trained by LP (Academic GP specialist in palliative care), KK (Academic Paramedic), and CL (Emergency Care Researcher) on using the GSFPIG for identifying patients in their last year of life and study processes. Participants were then asked to use the GSFPIG to screen every patient they attended who was aged 65 and over and assess the patient to determine if they were likely to be in their last year of life. Participants were asked to record the patient’s EOL status in the electronic patient clinical record (ePCR) and where the patient was determined to be EOL, also record the presence and type of ACP in place. Data was recorded in the palliative care section of the ePCR for ease of reporting.

Data were collected for 3 months from 15th August 2022 to 13th November 2022. The participating EMS clinical informatics team designed a bespoke anonymised data report that reported patients aged 65 and over and the paramedic documented EOL screening information and ACP information. This report was run weekly for the duration of the data collection period and included the data points outlined in .

Table 1 Characteristics of paramedic participants

From these data, the following percentages with 95% confidence intervals were calculated:

The percentage of patients attended by paramedics who were thought to be EOL.

The percentage of EOL patients attended by paramedics who had an ACP in place, and the type of ACP.

Phase B – Procedure and data analysis

Following the analysis of Phase A data, all participants were invited to complete a virtual semi-structured interview between October and November 2022. Interviews were conducted by KK and CL using a pre-defined interview schedule (supplemental material 1). Interviews were video and audio recorded using Microsoft Teams and transcribed verbatim by a university-approved transcriber. Interview analysis followed the framework method described by Gale and colleaguesCitation12 and was completed in seven stages by KK and CL: (1) Transcription, (2) Familiarisation with the interview, (3) Coding, (4) Developing an analytical framework, (5) Applying the analytical framework, (6) Charting data into the framework matrix, (7) Interpreting the data.

Results

Phase A

Thirty-five paramedics consented to participate in Phase A. Participating paramedics attended 1637 eligible patients during the 3-month data collection period. Of these patients 244/1637 (14.9%) (95% CI: 13.2%, 16.7%) were recorded as EOL; 119/1637 (7.3%) had unclear documentation to categorise EOL status; in 1071/1637 (65.4%) paramedics did not record EOL status because they forgot, were constrained by time, or the patient was clearly not EOL and not assessed formally using the GSFPIG. Where patients were screened with the GSFPIG as being EOL 125/244 (51.2%) (95% CI: 44.8%, 57.7%) had an ACP in place; 108/244 = 44.3% (95% CI: 37.9%, 50.7%) had no ACP in place and for 4.5% ACP status was unknown.

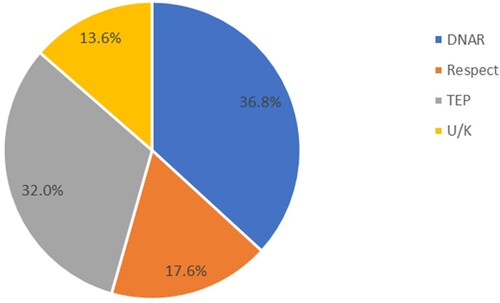

Of the 125 patients who were EOL with an ACP in place, 36.8% had a ‘Do Not Attempt Resuscitation Order’ (DNAR), 32.0% a Treatment Escalation Plan (TEP), 17.6% a Respect Plan and 13.6% an unknown type of ACP ().

Figure 1 Advance care planning breakdown by type where patient was screened as the end of life by the paramedic and advance care planning was in place. Note: Do No Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNAR), Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment process (ReSPECT), Treatment Escalation Plan (TEP), Unknown (U/K).

Phase B

All ten paramedics who volunteered to be interviewed and who had availability during the data collection period were interviewed. The characteristics of the participants are detailed in .

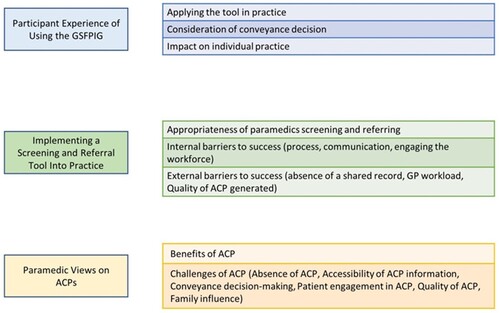

Three main themes were identified: Participant experience of using the GSFPIG; implementing a screening and referral tool into practice; and paramedic views on ACPs. Each theme had additional sub-themes ().

Quotes are presented in and referred to under each theme.

Table 2 Interview quotes

Theme 1: Participant experience of using the GSFPIG

Applying the tool in practice

The majority of the paramedics thought the GSFPIG was easy to use in practice and flowed well (1a), with one saying that they found it complicated initially, but quickly got used to it (1b). Paramedics described the ease of using the ‘surprise question’ and the General Indicators of Decline where the answer to the ‘surprise question’ was uncertain (1c).

Consideration of conveyance decision

Paramedics described being less likely to consider screening patients if they were being conveyed to hospital, as they expected that someone from the hospital team would complete this type of screening and advance care planning subsequently (1d).

Impact on individual practice

Paramedics described being more proactive in assessing a patient’s EOL and ACP status as a result of the research and had more of an understanding of the importance of early intervention in the last year of life (1e).

Theme 2: Implementing a screening and referral tool into practice

Appropriateness of paramedics screening and referring

Participants considered that paramedics are very well-placed to screen and refer patients for an ACP because they: attend to many people who have ‘slipped through the net’, visit patients in their own homes, and spend a considerable amount of time with a patient (2a, 2b).

Internal barriers to successful implementation – Process; communication; engaging the workforce

Paramedics felt that the GSFPIG should be built into the ePCR and that the initial training on the tool would be beneficial (2c, 2d). However, some participants described how once paramedics are trained in an area, it can lose prominence as the training focus shifts to other topics (2e). Participants also suggested that prompts would be useful to support the use of the screening tool (2f), along with some training on sensitive conversations. (2g, 2h).

Participants commented that they are under pressure to manage patients quickly so they can proceed to another emergency call, and this could be a barrier to screening and referral (2i). One paramedic indicated that they preferred to refer to a GP via telephone rather than email, but recognised this is not always feasible (2j).

External barriers to successful implementation – Absence of a shared record; GP workload; quality of ACP generated

Participants indicated that an absence of a shared patient record where paramedics can access ACP information, or a patient’s recent medical history, meant that paramedics are often working in isolation (2k). Paramedics were concerned about increasing the workload of GPs (2l, 2m). One participant, recognising the work pressures of GPs, recommended that other practice staff might be better placed to manage the referrals and ACP workload (2n).

Theme 3: Paramedic views on ACPs

Benefits of ACPs

Participants expressed positive views about ACPs, indicating that they support paramedics to make appropriate conveyance decisions (3a). Participants also suggested that an ACP supports managing patient and family expectations and understanding (3b).

Challenges of ACPs – Absence of ACP; accessibility of ACP information; conveyance decision-making; patient engagement in ACP; quality of ACP; family influence

Participants commented that many patients in the last year of life either do not have an ACP or do not have one put in place at an early stage in their last year of life (3c, 3d, 3e). Paramedics do not have access to a patient’s shared ACP record which is problematic as an ACP may be inaccessible to the paramedic (3f). Participants expressed that often there is not enough detail on ACPs to fully support conveyance decision-making (3g). One participant indicated that patient engagement and understanding in the process of ACP is important, so they know they have an ACP, what it says and where it is (3h). Another participant recognised the barrier of time concerning GP participation in ACP conversations (3i). Participants expressed that there is variation in the quality of ACPs generated and this is problematic for paramedics to work with (3j, 3k). Participants also indicated that some of the wording is vague and unhelpful, for example, ‘treatable problems’ (3l). In addition, ACPs need to be updated to reflect a person’s changes in wishes as they get closer to the last days of life (3m). Paramedics discussed the importance and the challenges around involving family members in the ACP discussion and the importance of doing this early in the last year of life so that there is understanding and consensus before any crisis occurs (3n, 3o).

Discussion

The findings of this study show that paramedics screened and recorded 14.9% of patients they attended aged 65 years and over as being in their last year of life. Of these patients, 44.3% were assessed to have no ACP in place. Where paramedics screened patients and they did have an ACP in place, 36.8% had no ACP more extensive than a DNAR. Paramedics described finding the presence of an ACP useful to support treatment and conveyance decisions and to guide an associated discussion. Paramedics found using the GSFPIG to screen patients for EOL status useful and straightforward and considered themselves well-placed to complete this task. Participants suggested the integration of an EOL screening tool with existing technology and prompts to aid paramedics’ use of a screening and referral tool for an ACP. Some participants expressed concern regarding the potential increased workload on GP services to instigate advance care planning in patients referred via EMS. One participant suggested that other staff at the GP practice could initiate advance care planning, thus avoiding additional burden on the GP. Alongside this study, we have completed research with GPs to understand their views on a paramedic screening and referral process to support advance care planning in patients presenting to the ambulance service who are in their last year of life (manuscript in preparation).

The results from this study support findings from a recent survey with UK paramedics by Eaton-Williams et al.Citation13 and suggest that paramedics regularly attend to patients in their last year of life who have not been recognised as such. Eaton-Williams et al.Citation13 also indicated that paramedics already make referrals for EOL care provision, but there is no formal process for doing so, and many paramedics were unaware of the GSFPIG. A strength of our research is that our data was collected prospectively, and paramedics recorded the data contemporaneously during the prehospital phase of care, thereby avoiding recall bias. Eaton-Williams et al.Citation13 identified facilitators for making referrals which included training in EOL assessment and establishing accessible and responsive referral pathways. Our research builds on this by establishing that with training, paramedics are able and willing to use the GSFPIG to screen patients for EOL status and to use this tool to refer patients to primary care for advance care planning discussions.

Our study indicates the potential for paramedics to identify and refer patients to General Practice who are in their last year of life and who may benefit from an ACP. Whilst the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee UK EMS Guidelines include aspects of the GSFPIG and the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool,Citation14 these are not tools that paramedics commonly have experience using. Our study indicates a requirement for paramedics to receive training and education in screening for EOL, and sensitive communication with patients, their carers and relatives.

We do not know whether implementing a paramedic screening and referral process to initiate advance care planning will have the intended consequences of increasing advance care planning in patients presenting to EMS. Future research could usefully test a paramedic screening and referral process for patients who may benefit from an ACP to understand the circumstances in which a screening and referral process works to support advance care planning.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A strength of our study is that it collected prospective data in a challenging research environment. Paramedic participants were keen to participate in the study demonstrating the importance of this field of research to them. A weakness of the study is that the participating EMS and these participants may not be typical, affecting generalisability. During the study, participants were required to remember to record the EOL status of eligible patients in the palliative care section of the ePCR. In 1071/1637 (65.4%) of eligible patients, the participating paramedics did not record EOL status. Participants reported that this was due to the tendency to record when a patient was EOL rather than not EOL. Interview findings also highlighted that where patients were conveyed to the hospital the paramedic was less likely to screen the patient for EOL status as they felt this would be actioned by the receiving hospital. As a result, it is likely there is significant underreporting of patients who are EOL and attended by paramedics in this research.

An additional weakness is that our study did not plan to analyse the different demographic and provisional diagnoses of patients presenting to the EMS who were screened as being EOL, but who had no ACP. Future secondary analysis of this data might be useful to understand where inequalities lie in access to advance care planning and an understanding of underserved groups. Existing evidence indicates that there is poor access to EOL care for people living with non-malignant conditions, dementia and those with learning disabilities,Citation2 but we do not know from our study whether these were the types of patients presenting to the ambulance service.

Conclusion

Paramedics are well-placed to use an EOL screening tool to identify patients who are thought to be in their last year of life and refer them to their GP practice to support advance care planning. Participating paramedics screened and recorded 14.9% of patients as EOL and 44.3% of these patients were assessed to have no ACP in place. Future research is required to address the practicalities of implementing a paramedic screening and referral tool for end-of-life care that results in the intended outcome of supporting effective advance care planning across all patient groups.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Funding This work was supported by Bristol, North Somerset, South Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group Research Capability Funding under Grant [RCF 18/19-3KK].

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval Research approval was received from the Health Research Authority: 22/HRA/2307. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of the West of England, Bristol: HAS.22.06.121. Where relevant, informed consent was obtained.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of the participating paramedics from South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09699260.2024.2339077.

References

- The Academy of Medical Sciences. End of life and palliative care: the policy landscape; 2019 Feb. Available from: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/66568982.

- National Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership. Ambitions for palliative and end of life care: a national framework for local action 2021–2026; 2021 [cited 2023 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ambitions-for-palliative-and-end-of-life-care-2nd-edition.pdf.

- NHS England. Universal principles for advance care planning (ACP); 2022 [cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/universal-principles-for-advance-care-planning.pdf.

- The Gold Standards Framework. Gold standard framework – advance care planning; 2018 [cited 2020 May 6]. Available from: https://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/advance-care-planning.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Advance care planning | Quick guides to social care topics | Social care | NICE communities | About. NICE. [cited 2023 Mar 11]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/nice-communities/social-care/quick-guides/advance-care-planning.

- Pocock LV, Wye L, French LRM, Purdy S. Barriers to GPs identifying patients at the end-of-life and discussions about their care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract 2019;36(5):639–43. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmy135.

- Goodwin L, Proctor A, Kirby K, Black S, Pocock L, Richardson S, et al. Staff stakeholder views on the role of UK paramedics in advance care planning for patients in their last year of life. Prog Palliat Care 2021;29(2):76–83. doi:10.1080/09699260.2021.1872140.

- Long D. Paramedic delivery of community-based palliative care: an overlooked resource? Prog Palliat Care 2019;27(6):289–90. doi:10.1080/09699260.2019.1672414.

- Improvement Hub. The route to success in end of life care – achieving quality in ambulance services. [cited 2023 Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/publication/the-route-to-success-in-end-of-life-care-achieving-quality-in-ambulance-services/.

- Gold Standards Framework. Gold standard framework – proactive identification guidance (PIG); 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 7]. Available from: https://goldstandardsframework.org.uk/proactive-identification-guidance-pig.

- South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust. Welcome to SWASFT. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.swast.nhs.uk/welcome/about-us/welcome-to-south-western-ambulance-service-nhs-foundation-trust-swasft.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-117.

- Eaton-Williams P, Barrett J, Mortimer C, Williams J. A national survey of ambulance paramedics on the identification of patients with end of life care needs. Br Paramed J 2020;5:8–14. doi:10.29045/14784726.2020.12.5.3.8.

- Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee. Association of Ambulance Chief Executives. JRCALC end of life care; 2022 Sep.