abstract

This focus piece examines the gendered impacts of climate change, using the Lake Chad Basin as a focal point. The Basin intersects four sovereign states (Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon and Chad) impacting close to 10 million people. Historically a beacon of biodiversity, the Basin has undergone significant transformations due to climatic shifts, directly affecting the local communities who are dependent on its resources. The narrative highlights women’s unique vulnerabilities and central roles within these communities, emphasising the necessity of a gender-centric approach to climate resilience and policy-making. Drawing on the insights and lived experiences of local women, a comprehensive roadmap of interventions is proposed. These include investing in water-saving technologies, providing alternative livelihood training, ensuring access to health services, and creating platforms for economic participation and advocacy. The importance of cross-border collaboration and robust monitoring systems is also underscored.

By intertwining localised experiences with broader policy recommendations, this work aims to establish a replicable template for addressing gendered vulnerabilities in climate-affected regions globally. In doing so, it champions a paradigm shift towards more inclusive, just, and effective climate action, ensuring that the unique needs and roles of women are at the forefront of our collective efforts towards a sustainable future.

Introduction

Climate change remains one of the most formidable challenges of our time, reshaping ecosystems and communities on a global scale. Although universally significant, its impacts manifest unevenly, intensifying pre-existing vulnerabilities (Ehiane & Moyo Citation2022). At the forefront of this global crisis is the Lake Chad Basin, a region grappling with stark ecological alterations and the subsequent societal ripple effects (Pham-Duc et al. Citation2020). Yet, as profound as these changes are, discussions surrounding them often only superficially concern an essential nuance: the gendered dimensions of displacement.

Historically, plans and policies on climate-induced displacement have adopted a generalised approach, that broadly addresses affected populations without delving into specific demographics. However, this broad generalisation obscures the vulnerabilities and challenges faced by women. Given their traditional roles in agriculture, fishing, and household responsibilities, combined with entrenched patriarchal norms, women in the Lake Chad Basin find themselves uniquely and disproportionately affected (Adaji & Oyibo Citation2019; Akinwumi & Oyinlola Citation2019).

Through its distinctively gender-centric lens, this focus piece ventures to illuminate these overshadowed gendered perspectives, placing women's experiences at the heart of the climate displacement dialogue. By intertwining socio-ecological analysis with gender dynamics, this research not only contributes to climate literature, but also pioneers a path of fresh, critical insights on gendered vulnerabilities inherent to climate crises. Thus, beyond identifying the challenges of climate-induced displacement on women, gender-responsive policy recommendations that resonate with the Basin's complexities are proposed. This focus piece highlights Lake Chad Basin's environmental shifts and further considers the deeper societal reverberations, particularly the plight of its most vulnerable — the women facing displacement.

Historical overview and environmental changes

Once one of the largest freshwater lakes in Africa, Lake Chad has played a pivotal role in the ecological economic, and socio-cultural dynamics of the region (Fougou & Lemoalle Citation2022). Historically, the lake has been a source of livelihood, a nexus for trade, and a focal point of cultural significance for the communities that surround it (Nilsson et al. Citation2016). Archaeological records and historical accounts indicate that the lake has witnessed significant fluctuations in its size over millennia, influenced by both climatic shifts and human interventions (Ifabiyi Citation2013). Its vast expanse in earlier eras was not just a geographical wonder, but also a testament to its resilience and capacity to support burgeoning civilisations. The lake's bounty, teeming with fish and surrounded by lush vegetation, offered sustenance to these ancient inhabitants, paving the way for sedentary agricultural communities (Adaji & Oyibo Citation2019; Akinwumi & Oyinlola Citation2019). As these settlements evolved, Lake Chad became a hub of trade and connectivity. Its waters facilitated transportation, while its strategic location bridged the trans-Saharan trade routes, connecting North Africa to sub-Saharan Africa (Zieba et al. Citation2017). Goods such as ivory, gold, and slaves from the south were exchanged for salt, dates, and other commodities from the north (Melchisedek Citation2024) and (Good Citation1972). This bustling trade fostered cultural exchanges, with the lake region becoming a melting pot of traditions, languages, and religions.

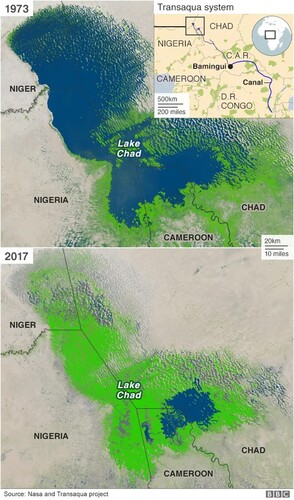

Historical chronicles and paleo-environmental studies indicate that Lake Chad's size has fluctuated significantly over the centuries (Hansen Citation2017). These natural oscillations were influenced by climatic cycles, with the lake expanding during wet phases and contracting during drier periods (NASA Earth Observatory Citation2017). However, the latter half of the 20th century witnessed unprecedented changes in the lake's dynamics. Starting from the 1960s, satellite imagery and scientific observations have documented a drastic reduction in the lake's surface area (Hansen Citation2017; NASA Earth Observatory Citation2017). Several factors contribute to this trend, with climate change playing a major role. Reduced rainfall in the region, increased evaporation rates due to rising temperatures, and unsustainable agricultural practices have collectively accelerated the shrinking of the lake (Hansen Citation2017; NASA Earth Observatory Citation2017).

By the turn of the 21st century, Lake Chad had lost over 90% of its surface area compared to its mid-20th century size. These environmental changes have ripple effects (Hansen Citation2017; NASA Earth Observatory Citation2017; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Citation2018). As the lake recedes, its aquatic ecosystems are disrupted, fish stocks depleted, and the once-fertile lands around the lake become barren, leading to reduced agricultural yields (UNEP Citation2018). Furthermore, the shrinking lake has amplified competition for resources, exacerbating tensions and conflicts among local communities and various armed groups who exploit the basin’s instability (Ehiane & Moyo Citation2022).

While there have been fluctuations and partial recoveries in the ensuing years, the overall trend is a significant diminishment of the lake’s hydrology as a result of prolonged droughts and human activity such as unregulated fishing, encroachment of wetlands and unsustainable water extraction (Pham-Duc et al. Citation2020). Upstream dam constructions, such as the Maga Dam in Cameroon and the Tiga Dam in Nigeria, have reduced water inflows into Lake Chad (Anders Jägerskog Citation2002). Designed for various purposes, including irrigation and hydroelectric power generation, these dams intercept and store water that would naturally replenish the lake (Anders Jägerskog Citation2002; Pham-Duc et al. Citation2020). The reduced inflow, combined with other factors such as over-extraction for agriculture and climate change-induced evaporation, has exacerbated the shrinkage of Lake Chad over the years, and has also influenced its depth, salinity, and overall water quality (Anders Jägerskog Citation2002; Pham-Duc et al. Citation2020).

With the changing physical characteristics of the lake, there has been a noticeable impact on its biodiversity. Fish species, once abundant, have shown declining numbers, with some even facing the threat of local extinction (Coe & Foley Citation2001). The reduction in lake size has also led to changes in bird migration patterns and a decline in some aquatic plant species, altering the once rich and diverse ecosystem (Olowoyeye & Kanwar Citation2023). Furthermore, the wetlands surrounding Lake Chad have undergone significant degradation (Olowoyeye & Kanwar Citation2023). This is particularly concerning since wetlands play a crucial role in water purification, groundwater recharge, and providing habitat for numerous species. These areas, once teeming with reeds, sedges, and grasses, have witnessed a reduction due to decreased water levels and human activities like agriculture and settlement expansion (Olowoyeye & Kanwar Citation2023; Coe & Foley Citation2001).

While the immediate consequences for biodiversity are evident and alarming, the long-term predictions based on climate models paint an even more concerning picture. Recent climate models provide a grim forecast for Lake Chad. Predictions suggest that if current trends continue, the lake may transform into a fraction of its former self or (in worst-case scenarios) disappear entirely within the century (Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb; Tower Citation2021). The region is expected to witness more frequent and prolonged droughts, further reducing the lake's capacity to recharge (Ehiane & Moyo Citation2022). However, there are also more optimistic models, suggesting the possibility of periods of rejuvenation if global climate change mitigation efforts bear fruit and local sustainable practices are adopted (Griffin Citation2020).

The possible futures of Lake Chad underscore the urgency of addressing both global climatic changes and regional conservation efforts. For the local communities, especially the women who are deeply intertwined with the lake's health, the stakes have never been higher. Given the intricate relationship between Lake Chad's environmental trajectory and the fate of its communities, it is critical to recognise the nuanced implications it holds for different demographic groups, especially women. As the lake's future remains uncertain, so too does the destiny of countless women who are central pillars of their communities. This brings us to an examination of the traditional roles women occupy within the Lake Chad Basin.

Traditional gender roles and livelihoods in the Lake Chad Basin

Central to Lake Chad Basin's community fabric, women have consistently anchored their families and societies amid the shifts and turns of environmental challenges. Understanding traditional gender roles, particularly those of women, is fundamental to comprehending the magnitude of the impact of environmental changes on their lives. Gender plays a profound role in delineating these livelihood strategies, shaping the daily rhythms of life in this ecologically vibrant yet vulnerable region. With climate change amplifying existing challenges, it becomes imperative to understand the traditional gender roles and how they intersect with livelihoods.

Pre-climate change setting of women's roles

Traditionally and currently, women in the Lake Chad Basin have always been the backbone of their families and communities. Engaged primarily in agriculture, fishing, and domestic responsibilities, they are custodians of both tangible assets (like crops and livestock) and intangible ones like local knowledge and traditions (Chama & Oyibo Citation2019). Women are responsible for household chores, including fetching water, preparing meals, caring for children, and ensuring the wellbeing of family members (Pepper, Brunelin & Renk Citation2017; Chama & Oyibo Citation2019). These tasks not only consume substantial time and energy but also require adeptness in resource management, given the region's inherent constraints. Moreover, many women are directly involved in farming activities, from sowing to harvesting (Adaji & Oyibo Citation2019; Akinwumi & Oyinlola Citation2019). They specialise in the cultivation of certain crops and often manage kitchen gardens, ensuring food security for their families. In communities located close to the lake, women play a crucial role in artisanal fishing (UN News Citation2023; Akinwumi & Oyinlola Citation2019). While men primarily handle the catch, women are responsible for processing, preserving, and selling fish, making them key stakeholders in the local economy (Chama & Oyibo Citation2019; Adaji & Oyibo Citation2019). The contribution of women to agriculture and fishing not only bolsters family income, but also acts as an economic safety net during times of crisis, such as crop failures or market fluctuations (Suleiman & Oyibo Citation2019; Pepper et al. Citation2017).

Worth mentioning is that women's labour was synchronous with nature's cycles. The rainy season saw them aiding in sowing crops, while dry periods led them towards the lake for fishing, or into forests for gathering firewood and medicinal herbs (Adaji & Oyibo Citation2019; Akinwumi & Oyinlola Citation2019). These roles highlighted their intimate connection with the environment. Apart from farming and fishing, women were skilled artisans, making handcrafted goods like pottery, textiles, and ornaments (Suleiman & Oyibo Citation2019). These crafts were not just an expression of cultural identity, but also provided additional economic avenues. The local markets often resonated with the vibrant chatter of women, both as sellers and buyers, reflecting their active participation in regional trade (Okpara, Stringer & Dougill Citation2016; Pepper et al. Citation2017).

While women's roles in agriculture and fishing were undeniably critical, they often faced societal constraints rooted in patriarchal norms. Land ownership primarily rested with men, making women dependent on male family members for access to farming plots (Baskin Citation2022; Sanusi Citation2018). Despite being primary contributors to food production, they were not always accorded equal status in decision-making, both at family and community levels. Their rights to land ownership were limited, and they had lesser access to formal credit systems or market networks (Baskin Citation2022; Sanusi Citation2018). This dichotomy between their significant roles and systemic challenges set the stage for the complexities they would face in the wake of climate change.

Direct consequences of environmental shifts on livelihoods

The entrenched gender disparities and societal constraints that marginalise women in agriculture and fisheries were dramatically exacerbated when the Lake Chad Basin began to undergo significant environmental shifts, which have far-reaching implications that transcend mere ecological concerns. These changes significantly influence the lives and livelihoods of its inhabitants, particularly women. A salient consequence is the profound impact on agriculture due to reduced water levels. First, the decline in water availability hampers irrigation, leading to compromised crop health and yield (Fu et al. Citation2023; Soboyejo, Sakinat & Bankole Citation2021). The situation is exacerbated by erratic rainfall patterns, which, coupled with a diminished water storage capacity, increase the frequency of drought-like conditions, escalating the risk of crop failure (Okpara, Stringer & Dougill Citation2016; Fu et al. Citation2023; Soboyejo et al. Citation2021). Additionally, the receding waterline often leaves behind soils that are either overly saline or arid, making them unsuitable for cultivation. Such soils are deficient in essential nutrients, further hindering healthy plant growth (Evans & Mohieldeen Citation2002; Griffin Citation2020).

Compounding these agricultural challenges is the increased labour burden placed on women due to water scarcity. Traditionally tasked with water-fetching responsibilities, women now find themselves journeying longer distances to secure this vital resource (Nilsson et al. Citation2016; Adaji & Oyibo Citation2019). This additional labour not only consumes a significant portion of their day but also imposes physical and psychological strains and exposes them to higher risks such as violence and sexual abuse (Adaji & Oyibo Citation2019; Akinwumi & Oyinlola Citation2019). Consequently, the time and energy that could be otherwise invested in farming is diverted, further underscoring the intertwined nature of environmental changes and gender roles in the Basin.

Building on the agricultural challenges posed by the lake's changing environment, another pressing issue emerges: the dwindling fish stocks of Lake Chad (Akinwumi & Oyinlola Citation2019). The receding waters equate to less available habitat for fish, precipitating a decline in fish populations and, by extension, reduced catches (Akinwumi & Oyinlola Citation2019). This is especially consequential for women, who have traditionally been at the forefront of fish processing and selling; their primary income source is now under dire threat.

Moreover, these environmental transformations have not just reduced the fish numbers but have also altered the very composition of species within the lake. Changes in water levels and quality can catalyse the replacement of native fish species with invasive ones (Okeke-Ogbuafor et al. Citation2023; UNEP Citation2018). These new fish might not hold the same economic or cultural value, reshaping both the economic landscape and local traditions. These challenges are further compounded by heightened competition among the fishing community. As the fish stocks decline, local fishermen and fisherwomen find themselves in intensified contests for the remaining catch (Okeke-Ogbuafor et al. Citation2023; UNEP Citation2018; Griffin Citation2020). This could inadvertently lead to overfishing, deepening the crisis and underscoring the intricate balance of ecological and societal elements in the basin.

With the cascading effects of reduced agriculture and fish stocks, it becomes necessary to diversify and adapt livelihood strategies. As traditional means of sustenance wane, there is a visible shift towards alternative income streams (Evans & Mohieldeen Citation2002). For instance, women, bearing the weight of these environmental challenges are embarking on new ventures such as handicrafts, pottery, or small-scale trading (Evans & Mohieldeen Citation2002). These endeavours, while novel and promising, might not be adequate to offset the economic losses suffered due to the decline in primary sectors like agriculture and fishing.

The journey of transition is not without its hurdles. Women, who are already navigating through societal expectations and limitations, frequently encounter obstacles when trying to access essential resources, be it markets, capital, or even skill-enhancing training for their new pursuits (World Food Programme Citation2016). However, adversity often breeds innovation. There are heartening tales of women banding together, forming collectives to consolidate resources, disseminate knowledge, and carve a path into broader markets (UN Women Citation2021). While these narratives might represent a fraction of the overall picture, they show the potential that resides in community collaboration and women's tenacity.

In drawing these observations together, it is evident that the environmental metamorphosis of the Lake Chad Basin not only manifests in ecological terms but reflects through the very socio-economic fabric of the society, as will be shown in subsequent sections.

Broader social and societal implications

The ripple effect of these environmental shifts in the Lake Chad Basin transcend the immediate economic scope, permeating the very core of societal structures and norms (Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb; Climate Diplomacy Citation2017). This impact, deeply rooted in the intertwining of ecology and community, is reshaping not just professions, but the broader societal canvas. The Lake Chad Basin has always been a testament to coexistence, a place where various communities intermingle and share resources and cultures (Griffin Citation2020; Climate Diplomacy Citation2017). Yet, the environmental trials of the present are stressing these age-old harmonies. With diminishing resources, the societal scaffolding, cemented over generations, finds itself at a precarious juncture. Competition intensifies, erstwhile allies view each other with suspicion, and tensions simmer beneath the surface (Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb; Griffin Citation2020; Climate Diplomacy Citation2017).

The cultural heartbeats of the Basin, be it fishing festivals or agricultural rituals, are finding it increasingly hard to withstand the environmental onslaught (Taub Citation2017). These are the very essence of the region's identity, and their disruption or potential loss is a tear in the cultural fabric, leading many to grapple with a sense of identity erosion (Taub Citation2017; Usigbe Citation2019). While environment-induced challenges are universal, their impacts are not evenly distributed. Inequalities, often lying dormant or subtly present, become magnified (Okeke-Ogbuafor et al. Citation2023; Boko et al. Citation2007; Tower Citation2021). Those equipped with resources adapt, while vulnerable demographics, including women and the aged, find the struggle intensified and insurmountable (Taub Citation2017; Okeke-Ogbuafor et al. Citation2023). Such widening chasms can sow seeds of resentment, potentially destabilising community equilibrium.

Furthermore, as many turn away from traditional professions, the region's social structures undergo change (Tower Citation2021; Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb). New ventures can either be a ladder of upward mobility or, if unsuccessful, a slide into further vulnerability. These shifts, while economically driven, realign social dynamics and hierarchies. Central to any community's resilience is trust. Yet in these trying times trust finds itself on shaky ground. The Basin, with its legacy of community sharing, now faces resource hoarding and mistrust, potentially weakening the bonds that have historically been its strength (Usigbe Citation2019; Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb; Tower Citation2021).

Adding another layer to this intricate puzzle is the mental health of the community members. The pressures (ecological, economic, societal) give rise to a plethora of mental health challenges (Usigbe Citation2019; Tower Citation2021). The daily struggles, compounded by anxieties of an uncertain future, make mental wellbeing a pressing concern (Usigbe Citation2019; Stanke et al. Citation2013). The Lake Chad Basin's narrative is a chronicle of a society in flux, where the repercussions of environmental changes resonate through every societal layer (Usigbe Citation2019; Stanke et al. Citation2013). Tackling the Basin's challenges necessitates a holistic lens, that acknowledges and addresses both the evident and the nuanced.

Building on the mounting pressures of resource scarcity and resultant societal tensions, another consequential facet emerges: human mobility (Tower Citation2021; Zieba, Yengoh & Tom Citation2017). The evolving challenges within the Lake Chad Basin not only test the resilience of its inhabitants but push many to reevaluate their ties to their ancestral lands. Migration, once a choice or seasonal pattern, now increasingly becomes a compelling necessity (Tower Citation2021; Zieba et al. Citation2017). As resources dwindle and confrontations intensify, a significant portion of the Basin's populace feels the strain, prompting them to seek pastures new (Tower Citation2021; Zieba et al. Citation2017). The migration patterns exhibit a marked shift from rural settings towards urban landscapes. People driven by hope and desperation flock to cities, envisaging a life less tethered to the impulses of the environment. But this urban charm brings with it a fresh set of challenges: burgeoning city populations strain urban infrastructure, sometimes replicating the resource scarcity they sought to escape (Tower Citation2021; Zieba et al. Citation2017).

Moreover, given the Lake Chad Basin's unique geographic positioning, criss-crossing several international boundaries, many migrations are not just inter-regional but transnational (Lamarche Citation2023; Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb). While offering hope for a fresh start, these cross-border movements are fraught with geopolitical intricacies, potentially complicating regional dynamics. However, the motivations driving these migrations are not purely environmental or economic. The push factors are a complex web, intertwining the tangible (like resource scarcity or conflicts), with the intangible (like aspirations for socio-economic upliftment, a yearning to escape local hostilities, or simply the quest for a more secure future for their children) (Lamarche Citation2023; Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb). These intertwined motivations, driven by the evolving environmental and societal landscapes of the Lake Chad Basin, underscore the multi-dimensional nature of the challenges at hand.

Implications for women’s rights, safety, health and societal status

The shifts in human mobility underlined by the migration patterns bring to the fore another dimension of the crisis: the impact on women, who, due to entrenched societal structures, find themselves at an intersection of environmental and social vulnerabilities. Migration unveils a host of challenges that disproportionately affect women (Hunter, Luna & Norton Citation2015; Kofman & Raghuram Citation2015). The treacherous routes they often traverse heighten their susceptibility to manifold dangers (Sassen Citation2014; Kofman & Raghuram Citation2015). Women, notably those journeying without the protective umbrella of family or male companions, grapple with threats of exploitation, trafficking, and physical harm (Sassen Citation2014; Kofman & Raghuram Citation2015). The very act of migration inadvertently ruptures the social safety nets women have traditionally relied upon (Boucher Citation2016). Relocating often means severing ties with familiar community networks, leaving them exposed in unfamiliar terrain.

Yet migration is not just a tale of vulnerabilities; it also alters societal support. The shift can potentially emancipate women from age-old roles, opening new platforms of opportunities (Sassen Citation2014; Kofman & Raghuram Citation2015; Hunter, Luna & Norton Citation2015); however, it can thrust upon them the mantle of being primary earners in alien urban environments, a role fraught with its own challenges (Boucher Citation2016; Sassen Citation2014; Kofman & Raghuram Citation2015). But perhaps most concerning is the erosion of women's rights amid the tumult. As the environment reshapes societal dynamics, there is an observable sidelining of women's rights. As traditional livelihoods are disrupted, women often find it challenging to secure alternative sources of income (Boucher Citation2016). With fewer economic opportunities, their rights to economic independence and decision-making in households might diminish, placing them in positions of financial dependency (Boucher Citation2016; Kofman & Raghuram Citation2015). Moreover, in many communities around the Basin land ownership is a crucial determinant of socio-economic status (Oruonye Citation2009). However, as families migrate or lands become inhospitable, women — who already face systemic barriers to land ownership — might see their claims to property further diluted.

In addition, the stress of dwindling resources, coupled with forced migrations, can amplify pressures on women to limit family size or undergo unwanted reproductive procedures (Hennebry, Williams & Walton-Roberts Citation2016). Access to reproductive healthcare and education might also decline in areas of displacement (Hennebry et al. Citation2016). To forge a path forward, a comprehensive understanding of these gender dynamics is pivotal. Only by recognising and addressing these intertwined challenges can holistic solutions be devised that not only mitigate environmental threats but also empower women, ensuring their health, dignity, and rights are safeguarded in these trying times of climate adaptation.

In this respect, education and empowerment could help fortify women’s resilience. Education can be the cornerstone, equipping women with the skills and knowledge to navigate environmental and societal challenges more effectively. Furthermore, education can help challenge and reshape societal norms, enabling women to transcend traditional roles and assert their rights. With education, women can diversify their skill sets, allowing them to adapt to changing environmental scenarios and reducing their vulnerabilities. Empowered and educated women can assume leadership roles within communities, championing innovative solutions and promoting gender-inclusive decision-making.

In addition to the layered vulnerabilities and gender dynamics in the Lake Chad Basin, it is pivotal to consider women's health and wellbeing amid the ecological crisis. When climate change is considered against societal norms and gender biases, the resultant challenges are not only intensified but also diversified. For women these challenges are further compounded by societal expectations and traditional roles, creating a spectrum of health-related concerns that span from physical wellbeing to reproductive rights (Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb; Okpara, Stringer & Dougill Citation2016; Gordon & Jay Citation2018).

To add to this, women, traditionally placed last in the order of feeding in many households, are particularly vulnerable to nutritional deficits. In times of resource scarcity they may find themselves having to forgo meals, leading to malnutrition and associated health complications (Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb; Gordon & Jay Citation2018). Furthermore, climate change brings with it a host of diseases, especially those that are water-borne, or vector-borne. Given their interaction with water sources and outdoor roles, women are at an increased risk of exposure to ailments. With the weight of ensuring household sustenance amid dwindling resources, women often bear immense stress which, coupled with witnessing the rapid environmental changes around them, can precipitate mental health challenges including anxiety and depression (Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb; Okpara et al. Citation2016; Csevár Citation2021). In regions where resource scarcity translates into conflict, women are exposed to potentially traumatic events (Frimpong Citation2020a,Citationb; Okpara et al. Citation2016; Csevár Citation2021). Whether it is witnessing acts of violence or facing displacement, the emotional and psychological scars run deep.

The changing environment, with its resultant mobility and resource scarcity, often disrupts women's access to essential reproductive health services. This can lead to a myriad of complications, from unplanned pregnancies to heightened maternal mortality rates (Gordon & Jay Citation2018; Hennebry et al. Citation2016; Kofman, & Raghuram Citation2015). Economic uncertainties stemming from the environmental crisis might increase early marriages, subjecting young girls to early pregnancies and their associated risks (Gordon & Jay Citation2018; Hennebry et al. Citation2016; Kofman, & Raghuram Citation2015). Resource-driven conflicts or migrations can expose women to heightened risks of sexual violence and exploitation (Gordon & Jay Citation2018; Hennebry et al. Citation2016). Such experiences leave lasting marks on their physical and psychological wellbeing.

In addressing these challenges, it is evident that the environmental crisis in the Lake Chad Basin extends far beyond mere ecological degradation. For the region's women it is a crisis that touches every facet of their lives, from their daily routines to their most intimate experiences. Addressing this requires solutions that are as multifaceted as the challenges themselves. This means coming up with solutions rooted in community understanding, cultural sensitivity, and an unwavering commitment to uplifting and empowering women.

A path forward: Gender-responsive climate policy recommendations

Climate change has long moved past the phase of mere acknowledgment — it is now a question of effective response and mitigation. Yet while various policy measures have been undertaken globally, their adequacy, especially from a gender perspective, remains questionable. It is thus imperative to move towards more gender-responsive climate policy actions. By recognising the differential impacts and challenges faced by women, and understanding the broader societal implications of these challenges, we can craft policies that are not only responsive but also sustainable in the long term.

Several global climate initiatives, including the landmark Paris Agreement, have emphasised the need for adaptation and resilience-building. However, while these overarching guidelines capture the essence of action needed, they often fall short in integrating adequate gender nuances. As Schalatek (Citation2022) notes, the “Paris Agreement mandates gender-responsive adaptation and capacity-building efforts”. However, regardless of this obligation, progress on gender action plans has been slow. As of 2020, less than half of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s 15 constituted bodies had demonstrated any progress towards integrating a gender perspective in their processes and plans (Schalatek Citation2022). Most climate-related policies have been designed with a general perspective, aiming to address the larger populace. The lack of specificity often renders these policies ineffective in addressing the unique challenges women face, especially in vulnerable regions like the Lake Chad Basin. For instance, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) under the Kyoto Protocol aimed at encouraging sustainable development and emission reductions, largely overlooks the distinct needs and roles of women in affected communities (Kafayat & Audu Citation2015; Subbarao & Lloyd Citation2011). Women in regions like the Lake Chad Basin, who are predominantly involved in agriculture and water collection, bear the brunt of climate change impacts but had limited access to the benefits of CDM projects due to existing social and economic inequalities (Kafayat & Audu Citation2015; Subbarao & Lloyd Citation2011).

Another example can be seen in the REDD + (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) programme, designed to combat deforestation and promote forest conservation (Chomba et al. Citation2016; Löw Citation2020; Larson et al. Citation2016). Despite its good intentions, the programme often failed to adequately consider the rights and knowledge of indigenous women, who play a crucial role in forest management and conservation (Chomba et al. Citation2016; Löw Citation2020; Larson et al. Citation2016). In many instances the benefits of REDD + were not equitably distributed, with women having limited access to financial incentives and decision-making platforms (Chomba et al. Citation2016; Löw Citation2020; Larson et al. Citation2016).

These examples highlight the gap in integrating gender nuances into climate-related policies, resulting in initiatives that not only fall short of addressing the unique challenges women face but also miss the opportunity to leverage women’s knowledge and participation in climate action. Addressing these oversights requires a more inclusive approach in policy design and implementation, ensuring that the voices of women, particularly those in vulnerable regions, are heard and valued.

Strategies tailored for the Lake Chad Basin

Given the unique challenges in the Lake Chad Basin, gender-tailored strategies are essential. In this regard it would be necessary to adopt an integrative approach that combines scientific research, traditional knowledge, and women's lived experiences. Thus, to comprehensively provide a roadmap for interventions, one would need to leverage the knowledge and wisdom of local communities, particularly women, in crafting policies and interventions. In this light, to address Lake Chad’s problem, it would be prudent to:

Invest in water-saving technologies and practices, enabling more resilient agricultural practices amid changing water levels. Initiatives could include community-led water harvesting techniques, construction of decentralised water storage infrastructure, and the promotion of water-efficient farming practices. These projects should actively involve women, acknowledging their primary role in water collection and utilisation.

Given the dwindling fish stocks and changing agricultural patterns, it is essential to provide women with training for alternative livelihoods, ensuring they are not left economically vulnerable.

It must be ensured that women have access to health services, particularly reproductive health, with promotion of education about climate change and adaptation techniques specific to the region.

Create platforms and support systems that allow women to actively participate in the economic revitalisation of their communities. This might involve establishing women-centric cooperatives, providing microloans, or fostering market linkages.

Promote grassroots advocacy, where women from the Lake Chad Basin can voice their concerns and solutions at regional and international climate forums. Their narratives can provide a powerful impetus for gender-centric climate action.

Implement regular evaluation mechanisms, involving women at every stage, to ensure policies remain relevant, effective, and adaptive to the rapidly changing climate scenario.

Establish women's cooperatives that focus on sustainable agriculture, fish farming, and artisan crafts. These cooperatives can provide women with shared resources, collective bargaining power, and a platform for knowledge exchange. They can also serve as hubs for disseminating climate-resilient farming techniques and innovative adaptations.

Leverage the unique cultural and environmental heritage of the Lake Chad Basin to develop eco-cultural tourism. This includes encouraging and training local women to become tour guides, artisans, and hosts, turning the challenges of the environment into an opportunity, while preserving the local ecology and culture.

Develop infrastructure with a dual focus: resilience against the changing climate, and facilitation of women's roles. For instance, designing flood-resistant housing close to water sources reduces the drudgery and risk for women who fetch water. Similarly, constructing safe community spaces allows women to gather, share, and learn.

Use technology to bridge information gaps. This involves equipping local women with mobile devices preloaded with applications providing weather updates, agricultural advice, market prices, and health resources. Digital platforms can also offer remote learning opportunities and access to broader markets for their products.

Since the Lake Chad Basin spans multiple countries, it would be necessary to foster cross-border collaborative initiatives. These can range from shared water management projects to cross-border women entrepreneur networks, creating a sense of solidarity and shared purpose.

Ensure that all interventions are accompanied by robust monitoring and feedback systems. This makes it possible to regularly assess the effectiveness of strategies and make relevant changes based on real-time feedback from the women and the communities they serve.

By implementing and refining these strategies in the Lake Chad Basin, one can create a replicable template for addressing gendered vulnerabilities in other vulnerable regions around the world. Such a holistic approach, rooted in localised nuances and aimed at broader applicability, ensures that our fight against climate change remains both inclusive and adaptive.

Conclusion

The Lake Chad Basin with its interplay of environmental changes and human narratives exemplifies the profound implications of climate change on society. This focus piece discussed the Basin's evolving landscape, emphasising the central role of gender in understanding and addressing vulnerabilities. From a historical perspective, the Lake's transformations impact not only ecosystems but the very fabric of human life, most notably for women. These environmental shifts spiral into broader societal challenges, magnified by the adversities women face in society.

The gender-focused policy recommendations not only underscore strategic interventions but advocate for a more profound paradigm shift in how we could address climate change. The recommendations herein champion the need for inclusive, just, and effective strategies, recognising that understanding and acting on the gendered facets of climate change is essential for holistic solutions.

In sum, the narrative of the Lake Chad Basin reinforces the urgency to incorporate gender at the forefront of climate discourse. As we face the complexities of an evolving climate, the Basin's story serves as a reminder of the importance of inclusivity and equity in shaping a sustainable future for everyone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rufaro Emily Chikuruwo

RUFARO EMILY CHIKURUWO is an environmental law researcher. Her research delves into indigenous law, climate change policies, and the intersection of human rights and environmental protection. As a postdoctoral fellow at UNISA, she combines rigorous research with administrative prowess, producing influential publications and fostering academic collaborations. Her commitment to legal academia and environmental advocacy positions her as an emerging leading voice in global environmental law discourse. Email: [email protected]

References

- Adaji, EE & Oyibo, W 2019, ‘Women's participation in agricultural production in the Lake Chad Basin: Implications for food security’, Journal of Agricultural Extension, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1-14.

- Akinwumi, II & Oyinlola, MA 2019, ‘Women’s participation in fisheries in the Lake Chad Basin: Implications for food security’, Journal of Agricultural Extension, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 1-14.

- Baskin, C 2022, ‘Empowering women's land rights as a climate change mitigation strategy in Nigeria’, Northwestern Journal of Human Rights, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 217-246.

- Boko, M, Niang, I, Nyong, A, Vogel, C, Githeko, A, Medany, M, et al. 2007, ‘Africa. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability’, Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, https://archive.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg2/en/ch9.html, accessed 21 September 2023, pp. 433-467

- Boucher, A 2016, Gender, migration and the global race for talent. Gender, migration and the global race for talent, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

- Chama, MA & Oyibo, W 2019, ‘Women's participation in household decision-making in the Lake Chad Basin: Implications for sustainable development’, Journal of Agricultural Extension, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 1-14.

- Chomba, S, Kariuki, J, Lund, JF & Sinclair, F 2016, ‘Roots of inequity: How the implementation of REDD+ reinforces past injustices’, Land Use Policy, vol. 50, pp. 202-213.

- Climate Diplomacy 2017, Lake Chad-Tackling Climate-Fragility Risks, https://climate-diplomacy.org/magazine/conflict/lake-chad-tackling-climate-fragility-risks, accessed 27 September 2023.

- Coe, M & Foley, JA 2001, ‘Human and natural impacts on the water resources of the Lake Chad basin’, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmosheres, vol. 106, no. D4, pp. 3349-3356.

- Csevár, S 2021, ‘Voices in the Background: Environmental degradation and climate change as driving forces of violence against indigenous women’, Global Studies Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 1-11.

- Ehiane, S & Moyo, P 2022, 'Climate change, human insecurity and conflict dynamics in the Lake Chad Region', Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1-16.

- Evans, M & Mohieldeen, Y 2002, ‘Environmental change and livelihood strategies: The case of Lake Chad’, Geography, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 3-13.

- Fougou, HK & Lemoalle, J 2022, ‘Variability of Lake Chad’, in RM Tshimanga, GD Moukandi N'kaya & D Alsdorf (eds.), Congo Basin Hydrology, Climate, and Biogeochemistry: A Foundation for the Future, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, pp. 513-518.

- Frimpong, OB 2020a, Climate change and violent extremism in the Lake Chad Basin: key issues and way forward 2020, Wilson Center-Africa Program, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/climate-change-and-violent-extremism-lake-chad-basin-key-issues-and-way-forward, accessed 23 September 2023.

- Frimpong, OB 2020b, Climate change and fragility in the Lake Chad Basin, Wilson Center, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/climate-change-and-fragility-in-the-lake-chad-basin, accessed 23 September 2023.

- Fu, S, Zhou, Y, Lei, J & Zhou, N 2023, 'Changes in the spatiotemporal of net primary productivity in the conventional Lake Chad Basin between 2001 and 2020, based on CASA Model', Atmosphere, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 1-15.

- Good, CM 1972, ‘Salt, Trade, and Disease: Aspects of Development in Africa's Northern Great Lakes Region’ The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 5, no. 4, pp 543-586.

- Gordon, E & Jay, H 2018, ‘Adolescent girls in the Lake Chad Basin: Complex emergency and compound threats’, Monash Gender, Peace and Security, https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/1801946/Policy-brief-Lake-Chad-Basin.pdf, accessed 17 September 2023.

- Griffin, TE 2020, ‘Lake Chad: changing hydrography, violent extremism, and climate-conflict intersection’, Expeditions with MCUP, vol. 2020, no. 1, pp. 1-30.

- Hansen, K 2017, ‘The rise and fall of Africa’s Great Lake’, Earth Observatory https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/LakeChad, accessed 29 September 2023.

- Hennebry, J, Williams, K & Walton-Roberts, M 2016, ‘Women working worldwide: A situational analysis of women migrant workers’, UN Women, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2017/women-working-worldwide.pdf, accessed 29 September 2023, pp. 1-87.

- Hunter, LM, Luna, JK & Norton, RM 2015, 'Environmental dimensions of migration', Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 41, pp. 377-397.

- Ifabiyi, I 2013 ‘Recharging the Lake Chad: The hydropolitics of national security and regional integration in Africa’, African Research Review, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 196-216.

- Jägerskog, A 2002, ‘Water regimes – a way to institutionalise water co-operation in shared river basins’, in Selected papers of the International Conference, from conflict to co-operation in international water resources management: challenges and opportunities, UNESCO-IHE Delft, Netherlands, 20-22 November 2002, UNESCO Division of Water Sciences, Paris, pp. 209-217.

- Kafayat, A & Audu, A 2015, ‘A review on women, climate change and clean development mechanism’, Journal of Energy Technologies and Policy, vol. 5, no. 9, pp. 45-48.

- Kofman, E & Raghuram, P 2015, ‘Care, women and migration in the Global South’, in A Coles, L Gray & J Momsen (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Gender and Development, Routledge, New York.

- Lamarche, A 2023, ‘Climate-fuelled Violence and Displacement in the Lake Chad Basin: Focus on Chad and Cameroon’, Refugees International, https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports-briefs/climate-fueled-violence-and-displacement-in-the-lake-chad-basin-focus-on-chad-and-cameroon/, accessed 1 October 2023.

- Larson, AM, Dokken, T, Duchelle, AE, Atmadja, S, Resosudarmo, IAP, Cronkleton, P, et al. 2016, ‘Gender gaps in REDD+: Women’s participation is not enough’, in CJP Colfer, BS Basnett & M Elias (eds), Gender and Forests, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, pp. 68-88.

- Löw, C 2020 ‘Gender and indigenous concepts of climate protection: A critical revision of REDD+ projects’, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 43, pp.91-98

- Melchisedek, C 2024, ‘Slavery in the Mandara Mountains and Lake Chad Basin’ in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. 2024.

- NASA Earth Observatory 2017, The Ups and Downs of Lake Chad, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/91291/the-ups-and-downs-of-lake-chad, accessed 28 September 2023.

- Nilsson, E, Hochrainer-Stigler, S, Mochizuki, J & Uvo, CB 2016, ‘Hydro-climatic variability and agricultural production on the shores of Lake Chad’, Environmental Development, vol. 20, pp. 15-30.

- Olowoyeye, OS & Kanwar, RS 2023, 'Water and food sustainability in the riparian countries of Lake Chad in Africa', Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 13, pp. 1-24.

- Okeke-Ogbuafor, N, Gray, T, Ani, K & Stead, S 2023, ‘Proposed solutions to the problems of the Lake Chad fisheries: Resilience lessons for Africa?’, Fishes, vol. 8, no. 64, pp. 1-10.

- Okpara, UT, Stringer, LC & Dougill, AJ 2016, ‘Lake drying and livelihood dynamics in Lake Chad: Unravelling the mechanisms, contexts and responses’, Ambio, vol. 45, no. 7, pp. 781-795.

- Oruonye, ED 2009, ‘Land and compensation issues in resettlement scheme: A case study of the Lake Chad resettlement scheme’, The Knowledge Review, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 16-22.

- Pepper, A, Brunelin, S & Renk, S 2017, ‘Assessing gender and markets in the Lake Chad Basin region’, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000022434/download/, accessed 12 October 2023.

- Pham-Duc, B, Sylvestre, F, Papa, F, Frappart, F, Bouchez, C & Crétaux, J.-F 2020, 'The Lake Chad hydrology under current climate change', Scientific Reports, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 5498-5508.

- Sanusi, SA 2018, Water governance from gender perspective: a review case of Lake Chad, unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Twente, The Netherlands, https://essay.utwente.nl/76634/1/Sanussi%2C%20S.A.%201765167%20_openbaar.pdf, accessed 12 October 2023.

- Sassen, S 2014, Expulsions: Brutality and complexity in the global economy, Harvard University Press, Havard.

- Schalatek, L 2022, Climate Finance Fundamentals 10: Gender and Climate Finance, https://us.boell.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/CFF10%20-%20Gender%20and%20CF_ENG%202021.pdf, accessed 22 October 2023.

- Soboyejo, LA, Sakinat, AM & Bankole, AO 2021, 'A DPSIR and SAF analysis of water insecurity in Lake Chad Basin, Central Africa', Proceedings of the International Association of Hydrological Sciences, vol. 384, pp. 313-318.

- Stanke, C, Kerac, M, Prudhomme, C, Medlock, J & Murray, V 2013, ‘Health effects of drought: A systematic review of the evidence’, PLoS Currents, vol. 5, no. 5. doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.7a2cee9e980f91ad7697b570bcc4b004

- Subbarao, S & Lloyd, B 2011, ‘Can the clean development mechanism (CDM) deliver?’, Energy Policy, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 1600-1611.

- Suleiman, AA & Oyibo, W 2019, ‘Women's participation in small-scale businesses in the Lake Chad Basin: Implications for poverty reduction’, Journal of Agricultural Extension, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 1-14.

- Taub, B 2017, 'Lake Chad: The world’s most complex humanitarian disaster', The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/12/04/lake-chad-the-worlds-most-complex-humanitarian-disaster, accessed 17 October 2023.

- Tower, A 2021, ‘Shrinking options: climate change, displacement and security in the Lake Chad Basin’, Climate Refugees, https://www.climate-refugees.org/reports/case-study-loss-and-damage, accessed 10 October 2023.

- United Nations Environment Programme 2018, The tale of a disappearing lake, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/tale-disappearing-lake, accessed 28 September 2023.

- UN News 2023, Fisherwomen of Lake Chad show optimism in face of multiple challenges, https://www.un.org/africarenewal/news/fisherwomen-lake-chad-show-optimism-face-multiple-challenges, accessed 1 October 2023.

- UN Women 2021, From victims to leaders: ending gender-based violence in the Lake Chad Basin, https://wrd.unwomen.org/explore/insights/victims-leaders-ending-gender-based-violence-lake-chad-basin, accessed 20 September 2023.

- Usigbe, L 2019, Drying Lake Chad Basin gives rise to crisis, https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2019-march-2020/drying-lake-chad-basin-gives-rise-crisis, accessed 12 October 2023.

- Vivekananda, J, Wall, M, Sylvestre, F & Nagarajan, C 2019, Shoring Up Stability. Addressing climate and fragility risks in the Lake Chad region, Adelphi, Berlin.

- World Food Programme 2016, Lake Chad Basin Desk Review: Socio-economic analysis of the Lake Chad Basin Region, with focus on regional environmental factors, armed conflict, gender and food security issues, file:///C:/Users/rufar/Downloads/wfp284135%20(1).pdf, accessed 4 October 2023.

- Zieba, FW, Yengoh, GT & Tom, A 2017, ‘Seasonal migration and settlement around Lake Chad: Strategies for control of resources in an increasingly drying lake’, Resources, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 1-17.