Abstract

This article revisits a suite of Worimi objects in the British Museum whose collection is attributed to Sir Edward Parry, Australian Agricultural Company commissioner from 1830–1834, and brings into view the oft-overlooked diaries and letters of his wife, Lady Isabella Parry. By foregrounding Lady Parry as the primary distributor of material, I shed light on her circulation of objects from Port Stephens to her family estate in Cheshire. Finding herself isolated in an unfamiliar environment, Parry wrote letters and assembled collections in an attempt to exert control over her surroundings and reassert connections to England. While Parry never achieved a sense of belonging within the colony, her material legacy illustrates the importance of collecting and gift-giving to imperial women’s identity formation. Her archive speaks to the value ascribed to colonial material culture within British families, generating knowledge about some of the many Aboriginal objects housed in museums throughout Britain.

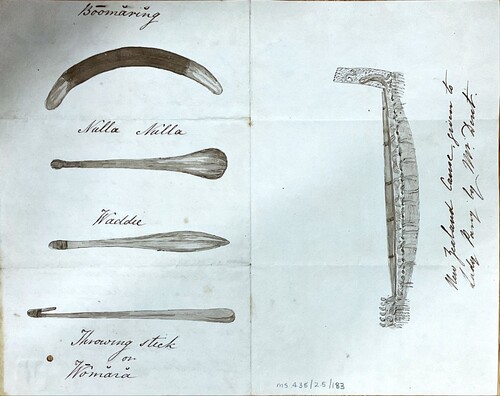

In early February 1831, almost one year after her arrival in New South Wales, Lady Isabella Parry prepared to send a parcel from her new residence at Tahlee House, near the Carrington Australian Agricultural Company settlement in Port Stephens, to her family’s Alderley Park estate in Cheshire. It comprised a custom-built box guarding a ‘New Zealand canoe’, and inside the canoe she had carefully placed birds, insects and ‘some things belonging to our Natives, of which I have made sketches with their different names’, she reported in a letter to her mother.Footnote1 These included multiple Worimi fishhooks, spears, clubs, boomerangs, and a shield. Anticipating her family’s reaction to receiving the material, she noted: ‘I think you will be rather amused at the queer collection of articles, some of which certainly are scarcely worth sending, except that in England anything from New South Wales acquires value’.Footnote2

Such a statement held true nearly a century later when some of these objects were donated to the British Museum.Footnote3 In 1926, Frederick Parry, the grandson of Lady Isabella and Sir Edward Parry, offered up his family’s sprawling collection to the national institution. He wrote to a British Museum curator that he had ‘labelled as many [items] as I could’, and it was Edward – without mention of Isabella – who was credited as their collector.Footnote4 While neither Edward nor Isabella make reference in their personal papers to the circumstances in which they acquired Worimi objects, it was Lady Parry who eagerly distributed them to her extended familial network, with her writings punctuated by a constant attention to the circulation of letters and packages between Port Stephens and England. Though Frederick never knew his grandmother, as she died in 1839 during childbirth aged just thirty-seven, he unknowingly echoed her by referring to the collection as a ‘very miscellaneous jumble of curios’, confessing he was ‘so glad that the greater part … has been found worthy of a place in the Museum’.Footnote5

This article revisits this material, taking up a recent call for scholars ‘to consider the meanings ascribed to Australian Indigenous objects within British families’ across the colonial period.Footnote6 I build on a growing field of materially rich cultural inquiry to examine why, and under what circumstances, Worimi and other material culture that was acquired from the colonies travelled, and in turn provide insight into Lady Isabella Parry and her oft-overlooked diaries and letters.Footnote7 While it is difficult to establish Parry’s agency in the collecting process, her writings are replete with curiosity about the natural and material world she encountered, and reveal how keenly interested imperial women could be in describing, packaging, and circulating objects to familial networks in England.Footnote8

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Lady Parry’s writings generate little insight into the significance of Worimi objects to Worimi lives and culture within Port Stephens. The collection she dispersed instead provides an entry point into her experiences in the Hunter region and help to illuminate the exchange dynamics that facilitated cross-cultural encounters. Objects such as those amassed by early settlers are today spread throughout Britain and Europe and have become disconnected from documentary records that reveal the circumstances in which they were exchanged and came to accumulate value. This article reconnects extant material with Lady Parry’s archive, and in doing so, demonstrates that the circulation of objects and writings that accompanied them formed a significant part of imperial women’s identity formation.

For Lady Parry, packaging and distributing material to send to her family became a means to escape her surroundings and reassert connections to the sorely missed social world of England. Isabella found herself isolated in the unfamiliar environment of Port Stephens, a condition exacerbated by a lack of female companionship and society of an equivalent class. Raising newborn children away from domestic support, her diaries reveal that she faced feelings of insecurity, moral anguish, and limited mobility as she attempted to navigate her new role as a mother and Company wife. While she threw herself into constructing a domestic sanctuary at Tahlee House, the Carrington settlement and its environs resisted many efforts at self-fashioning. The process of writing letters and assembling collections during her four years in the colony thus became a way to project a sense of control in the midst of her discomfort, while simultaneously reinforcing ties to British familial networks.

Isabella Parry in family and archival memory

In recent decades, scholars within the ‘new imperial history’ have persuasively articulated the extent to which the British Empire operated and indeed facilitated a sprawling web of interconnected individuals, objects, and ideas.Footnote9 A prime concern of this historiography has been to break down the interpretive divide between the imperial centre and the colonial periphery. Such ideas have found productive ground in studies of material culture, with Elizabeth Edwards and others recognising that ‘colonialism was profoundly material and colonised and imperial centres were critically linked by a traffic in objects’.Footnote10 This spatial concern with the mobility of objects and biographies has contributed to elucidating the myriad forces underpinning colonial-era museum collections and the people responsible for assembling them.Footnote11

Lady Parry lends herself well to these theoretical dynamics. Born Isabella Louisa Stanley in 1801, she was raised in an extended family of collectors and explorers. Her father John Stanley was an early British navigator of Iceland and a friend to Joseph Banks.Footnote12 Her cousin, Owen Stanley, was a Royal Navy officer who collected hundreds of artefacts while conducting a voyage in the HMS Rattlesnake from 1846, and his father, the Bishop Edward Stanley, was president of the Linnean Society for over a decade from 1837.Footnote13 Her niece Alice Stanley became wife to Augustus Pitt Rivers, the British Army officer whose collection of over 20,000 ethnographic objects formed the basis of a museum at the University of Oxford.Footnote14

Material culture and natural history specimens performed a range of functions within the Stanleys’ social network, and objects and gift-giving were bound up in affective relations of gender and patronage. This was evidenced when Isabella, at the age of twenty-six, married esteemed Arctic explorer Edward Parry. In a testament to the colonial collecting culture the Parrys were to be engaged in, they received a racoon skin as a wedding gift from Edward’s colleague – and later Governor of Tasmania – John Franklin that was proudly displayed above their London fireplace.Footnote15 Three years later, the couple sailed to New South Wales where Edward took up the role of Commissioner of the Australian Agricultural Company. Isabella’s marriage to Edward consolidated the culture of naval collecting in which she had been raised, and she travelled to the colony with established ideas about the curiosities she would find and send back to her connections in England.

While Lady Parry features passingly in accounts of her husband, the Stanleys’ published correspondence focuses on the years following her death and, as a result, she does not emerge as a prominent figure in her family’s public memory.Footnote16 Where Isabella does appear in subsequent writings, she is represented as youthful and pious in accordance with idealised conceptions of nineteenth-century femininity. Ann Parry’s biography of her ancestor Edward writes that he was ‘captivated by [Isabella’s] joyous spirit … her youthful face framed in short ringlets’.Footnote17 Much to the dismay of her mother, the matriarch Maria Stanley, Isabella adopted her husband’s evangelical faith. The couple brought eighty bibles with them to New South Wales, with Edward establishing the Company’s first church while Isabella founded a school for the local children. These activities have made Lady Parry a figure of interest to Australian religious historians and earned her a memorial in Stroud, commending her as ‘Earnest In Personal Piety, And … All Duties Of Domestic Life’.Footnote18 Similar interpretations have been mirrored in the press. A 1941 article depicts Isabella alongside Edward and a child (though she had four by the time they departed Port Stephens), waving to settlers and an Aboriginal man as they return to England. Here, she is remembered as exemplary of ‘pioneer women’ who left ‘lovely English homes … to blaze new trails in a distant unknown land’.Footnote19

Despite some community and scholarly interest within Australia regarding the Parrys’ time in the colony, Isabella Parry’s personal papers have been largely overlooked. Comprising four diaries and close to five hundred pages of letters, a great deal of this corpus relates to Lady Parry’s time in New South Wales. Like many of the writings penned by elite, imperially mobile women, she provides insight into the Empire and its domestic practices.Footnote20 Her archival presence is nevertheless tethered to her husband’s career and held at the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge, an environment Penny Russell describes as ‘quintessentially masculine’.Footnote21 Moreover, her personal papers have never been published and are largely inaccessible to researchers outside the United Kingdom.Footnote22 This article works to redress this imbalance by taking Isabella Parry’s rarely considered Australian diaries and letters, and the material and collecting histories they illuminate, as its evidentiary base.

Women’s worlds and company life, 1830–1834

When Lady Parry reached Port Stephens in May 1830, she wrote to her sister Louisa that ‘I certainly ought to be well and happy here, for we have everything almost that we could wish for’.Footnote23 She had arrived in the colony heavily pregnant six months prior and immediately entered confinement following the voyage. Her first two children had died in England before their first birthdays, and after ill health, she gave premature birth to twins at Government House in Sydney under the care of Eliza Darling, wife of Governor Ralph Darling.Footnote24 After Lady Parry and the infants recovered and relocated to Port Stephens, she remained close with Sydney women including Eliza, and later Eliza’s sister-in-law, Sophia Dumaresq.

The Parrys were immediately at ease with the upper echelons of colonial society. Angela Woollacott has identified an ‘intimacy and pervasiveness’ of imperially mobile settler families such as the Darlings and Dumaresqs of New South Wales.Footnote25 Isabella and Edward became interlinked with these networks and indeed had already been acquainted with the Dumaresqs in Britain. All shared attitudes regarding gender roles, the natural world, and hierarchies of class and race. Lady Parry found companionship with her fellow imperial women and each couple belonged to what Stuart Robertson calls the colony’s ‘ruling dominant minority’ of evangelicals.Footnote26 When the Darlings left Australia in 1831, Lady Parry lamented that they had become ‘like part of our family’.Footnote27

During the 1820s and 1830s, there were mounting tensions between an evangelical belief in ‘moral colonialism’ that sought to ‘protect’ Aboriginal people from introduced vice, and burgeoning settler concerns with advancing a productive and self-sufficient economy.Footnote28 Shaped by both discourses, the Australian Agricultural Company was founded in 1824 by an Act of British Parliament and granted one million acres in New South Wales for the cultivation of pastoral land. The harbour around Port Stephens was chosen by the Company’s first manager, Robert Dawson, as its initial permanent establishment, and was named Carrington, an anglicised version of the Worimi word Carabeen. Five hundred free settlers arrived with Dawson to serve as the Company’s workforce, which soon grew as it employed convict labour. Damaris Bairstow observes that in its isolation, Carrington constituted ‘a new colony, settled by Englishmen with no colonial experience’.Footnote29 While the Worimi were not initially conceived to be central to Company industry, the executive soon found cooperation to be an effective policy, reporting they could ‘with good treatment of the natives, be materially aided by their assistance, [and, through labour, the Worimi] may also gradually be led into a state of civilisation and knowledge’.Footnote30 The executive acknowledged it was ‘impossible to avoid noticing the valuable and unexpected assistance … derived from them [the Worimi]’ as the settlement developed, with Dawson reflecting that they ‘had become almost necessary to the families in carrying water, collecting and chopping firewood, and supplying them with fish’.Footnote31

Evangelism and the pursuit of economic productivity continued to be twin aims of the Company under Edward Parry’s commissionership. Dawson’s management was short lived, and he was dismissed from the role without notice after two years, facing criticism for selecting poor-quality land and encouraging ‘disgusting familiarity’ between settlers and the Worimi.Footnote32 Parry was thus a high-profile new appointment, and was tasked with consolidating Stroud and Gloucester as the Company’s inland pastoral establishments.Footnote33 Lady Parry was to remain in Carrington, living at Tahlee House one mile from the settlement, and tending to the religious and educational life of the Company people. She wrote to her mother regarding their authoritative new positions, stating: ‘We have … in many respects superior advantages to what we could have as a Master and Mistress of an English Country place, everyone here is so completely under Edward’s control’.Footnote34 She reflected later to her sister in law Caroline that,

everybody agrees with us, in feeling that we are the most enviable people here, and our situation better and more comfortable than that of anyone else. [We have] none of the disheartening anxiety of the poor settlers, or thankless troubles and vexations of the government people. In a manner we are quite independent and have every comfort and advantage.Footnote35

Oh! It is a miserable place and one can never feel happy and cheerful whilst living among such people. I have felt it very much today, being all alone and I could not help often wishing to be back in England again and amongst Christian friends.Footnote38

Exchanges with, and representations of, the Worimi

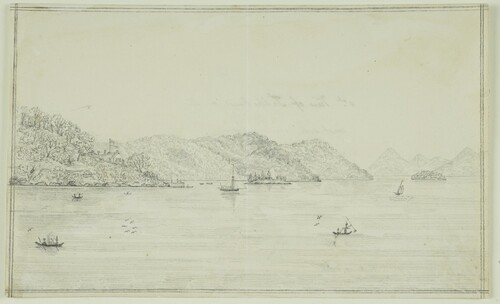

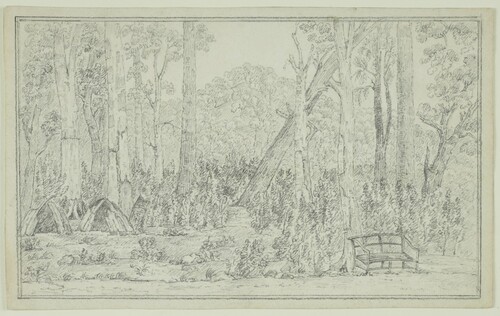

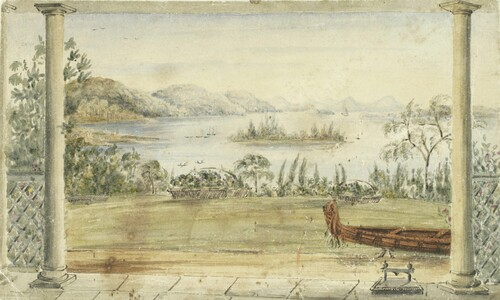

Lady Parry’s letters to England take on a more descriptive quality, no doubt seeking to satiate her family’s curiosity about the colony and its inhabitants.Footnote39 While she makes only occasional reference to the Worimi in her diaries, her correspondence frequently references ‘the Blackfellows’ in vignettes that emphasise material and social difference. In an early letter to Louisa, Lady Parry admitted that ‘I have not made acquaintance with many of them, as they are very shy of me’ and ‘the women especially … run and hide themselves if they see me coming or if I go near their huts’.Footnote40 She nevertheless remained keenly interested in Aboriginal women’s presence within Port Stephens, producing sketches she posted to Alderley that dotted Worimi fisherwomen in canoes across the bay (see ) and illustrated their bark huts (see ).Footnote41 Isabella had her own row boat that she would take onto the harbour, and told Louisa that women were ‘the principal fishers and are made to do all the hard work and also continually have their heads broken by their husbands who behave most cruelly to both the women and the children’.Footnote42 This observation reflects tropes about Aboriginal male violence and indolence that were well-rehearsed across colonial media, and indeed many of her remarks about the Worimi are consistent with prevailing and often contradictory settler colonial discourses about Worimi and other First Nations people.Footnote43 She wrote that while there was ‘scarcely any hope of civilising them’, the Worimi are nevertheless ‘very superior to most in the colony and are a fine race of people’.Footnote44

Figure 1. ‘View of Tahlee House on the west side, coming from Sawyer’s Point’, Isabella Louisa Parry, 28 August 1832, Scott Polar Research Institute, Y: 77/4/3. Images reproduced with the permission of the Scot Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge.

Figure 2. ‘View on top of the Hill at the back of Tahlee, near Prospect Place’, Isabella Louisa Parry, c.1830–1834, Scott Polar Research Institute, Y: 77/4/8. Images reproduced with the permission of the Scot Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge.

Parry was especially captivated by the relationship between Worimi women and children, and soon found material culture to be a valuable medium through which to forge relations. In a rarely documented instance of women-directed exchange, Parry leveraged her new role as a mother when telling Louisa that:

The other day one of the Gins came up with a little pickaninny and begged me to give a cap or frock like my pickaninnys, and I wish you could have seen the little black thing jump about with delight when I gave it a small white shirt.Footnote45

Little Black Hannah went very regularly [to school] as long as her clothes lasted, but when her little jacket which Crowther [the Parrys nurse] had made before we left was worn out, she would not go, being ashamed of her native dress amongst the other children’.Footnote48

References to Worimi language and material culture also punctuate Lady Parry’s letters, demonstrating the circulating nature of exchange at the Carrington settlement. Parry readily amassed a collection of local words to frame her experiences in Port Stephens, adopting the gendered term ‘gin’ to refer to Aboriginal women and ‘pickaninny’ to describe Worimi children as well as her own.Footnote50 The nickname Parry gave her daughter Isabella was also taken from the Worimi language, telling her mother she is generally known as ‘Myttie … (the black name for little)’.Footnote51 Parry often references Worimi material culture as props in an aestheticised social scene, telling Lady Stanley:

The little bark canoes look very picturesque … I wish very much that I could take the likeness or paint groups of figures, yesterday on the flat at Carabeen, there was a most picturesque group of blacks, sitting round a fire, with their spears and waddies.Footnote52

Simultaneously, the act of sharing these anecdotes in letters to her family serves to affirm ties to England and illuminates Parry’s attempt to dispel her sense of isolation. The majority of her references to the Worimi are peppered by quips that imagine how her family would react to such encounters, writing variations of: ‘I often think how amused and astonished you would be if you could see some of the things, which now we take scarcely any notice of’ and ‘what horror and astonishment would be excited if any of our black friends were to be seen walking about in Alderley wood with their spears and waddies’.Footnote53 David Gerber writes of immigrant letters that they ‘are not principally about documenting the world, but instead about reconfiguring a personal relationship rendered vulnerable by long-distance, long-term separation’.Footnote54 This is clear in the case of Isabella Parry, as her continual evocation of her family and former home works to establish a boundary between herself and her life in Port Stephens. As is so often the case, her writings about the Worimi reveal more about her social preoccupations, cultural assumptions, and anxieties than they do about Aboriginal lives in the region.

Cultures of collecting

Assembling packages from Port Stephens to send to England was a further means for Lady Parry to project a sense of ownership over her environment and reinforce belonging with distant familial networks. The Stanley and Parry families came from a collecting culture laden with expectations about New South Wales and the value of its natural history and material culture.Footnote55 Australia’s presence was felt in the library at Alderley Park long before the Parrys arrived in the colony, and Isabella referred to the Stanleys’ first-edition copy of David Collins’ An Account of the English Colony in NSW to relate to her experiences and enable her family to do the same.Footnote56 She told Louisa, for example, that ‘we had a Corrobery [sic] of the Natives belonging to this place, which is an exhibition of their dances as described and drawn in Collins’ book and which drawings are very good’.Footnote57 This passage illuminates Nicholas Thomas’ assertion that ‘colonialism has always … been a cultural process’ and reveals the popular exploration narratives from which Parry framed her experiences.Footnote58

Parry enacted colonial cultural processes that merged intellectual and social purposes for collecting in the first parcel she sent to Alderley. She is apologetic regarding its contents, telling her mother: ‘I wish we had some more things … but there are not so many interesting articles particular to the Country which will do to send’.Footnote59 The box nevertheless contained numerous birds and insects, and several Aboriginal objects. While she does not mention how the objects came into her hands, her possessive statement that they were from some of ‘our natives’ suggests they are Worimi. As Edward spent considerable time on expeditions to inland settlements employing Aboriginal guides, it is also possible the objects were acquired through his relationships. Isabella told her sisters on multiple occasions, however, that ‘the black fellows constantly bring things for you to buy’, and they could have purchased a whole menagerie if desired. She wrote of some of the parcel’s contents that the ‘fishhooks and nets are curious and will have an interest in the Australian Shelf of the Cabinet in the Passage’, indicating that Alderley House already boasted a display of material from New South Wales.Footnote60

To accompany the package, Parry sketched and labelled some of the objects to highlight different qualities and emphases in pronunciation (see ).Footnote61 As was common in colonial visual representations of Aboriginal material culture, Worimi objects are rendered into neat typologies that further project Parry’s authority over her environment. The sketch conforms to the conventions of colonial collecting guides and satisfies the Linnean ‘comparative philological approach to ethnology’ popular in scientific collecting circles.Footnote62 Like her descriptions of material encounters with the Worimi, Lady Parry’s account of the purpose and function of the objects en route to Alderley further relies on the ‘genealogies of European representation’ that constructed imperial knowledge about Aboriginal people.Footnote63 These cultural assumptions can be seen in the blurb she wrote on the back of the sketch:

The boomerang is an instrument of amusement … though sometimes turned into a weapon of War … The Waddie and Nulla Nulla are instruments of War and are often used upon the heads of their Gins. And a stunning blow upon the Cobera (head) is the first act of making love [emphasis in original].Footnote64

Figure 3. Sketch by Isabella Louisa Parry in ‘Letter to Lady Maria Stanley’, 1 February 1831, Scott Polar Research Institute MS.435/25/183. Images reproduced with the permission of the Scot Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge.

Parry eagerly awaited news of her family receiving the package, noting in her diary that she often looked out for the Company’s cutter that brought news from England. She followed up in a letter to her mother, and reflected similar sentiments to her sisters, that ‘I long to hear about the opening of the Canoe and whether you think it and the various native instruments were worth the expense of the carriage’.Footnote67 Assembling this parcel for her family, like many letters and subsequent packages, served an important affective role for Parry as she sought to project a sense of control over her colonial experiences. This guise of ownership and belonging was converted into the act of giving and was an attempt to reinforce her ties to distant social networks. Lady Parry’s anxiety in awaiting news of the package’s arrival reveals that this transaction was no simple antidote to her discomfort, and indeed could not grant the reassurance she desired. She appealed to her sister after two years in the colony to continue sending a steady stream of correspondence to Port Stephens, as: ‘I don’t find that my interest and pleasure in receiving letters from my own dear people at home is in any degree lessened’. Rather, ‘the script of the handwriting of every one of those whom I so dearly love … brings the same feeling of peculiar delight’.Footnote68

Domestic connections and exhibiting the home

Lady Parry’s collecting activities were also tied to her attempts to establish a feeling of domestic belonging in Port Stephens and served as a conduit binding her new home at Tahlee House with family at Alderley Park.Footnote69 As recent scholarship has articulated, the English country house was ‘a key means of sustaining a shared familial identity over time’, and Alderley had been the centre of the Stanley family for over three hundred years.Footnote70 Isabella was born there, and married Edward at the family’s parish church.Footnote71 The mansion encompassed sixty rooms and was constantly evoked in Lady Parry’s writings. She modelled many of her collecting endeavours on what she believed would suit the home’s interior, recalling of the New Zealand canoe that ‘we thought it so much too curious and beautiful to keep in Port Stephens’.Footnote72 Isabella and Edward had bought the article from Thomas Dent, a merchant who imported tea to the Company and oversaw an opium trading house in China.Footnote73 They also received ‘a set of New Zealand and Tahitian things’ from William Yate, a Church Missionary Society missionary who visited Carrington in 1832. Parry immediately packaged these materials to send to her mother, telling her: ‘Among them is a cloth for the library table at Alderley which will … look very handsome and be a curiosity’.Footnote74

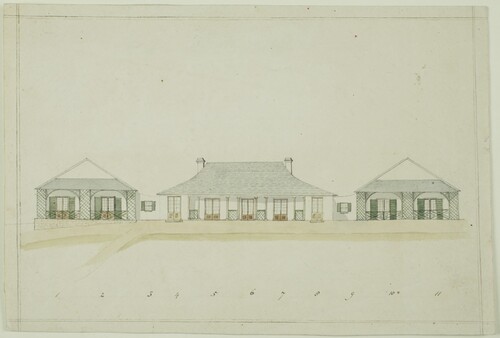

These cultural influences were multidirectional, and with Alderley as her model, Parry threw herself into the construction of a domestic sanctuary at Tahlee House. Considered the traditional domain of women, shaping a home in the colony was a primary means through which female settlers were expected to assert a sense of belonging in unfamiliar landscapes.Footnote75 Parry sketched her mother images of their residence, showing ‘what the house is like, better than any description’ (see ).Footnote76 These included scenes of Port Stephens, complete with a New Zealand canoe and children’s toys in the foreground, and Worimi canoes sharing the waters with settler vessels in the distance (see ).Footnote77 As Joan Kerr has observed of colonial women’s image making, ‘family … on the other side of the world kept [this art] as proof that the cultural values of “home” were being inscribed on a new country’.Footnote78 For Parry, producing these images were also a way to project ownership over the space and illustrate the boundaries of her social world – including family, valued artefacts, and the distant presence of the Worimi. The canoe she illustrated was a smaller version of the one sent to Alderley and had also been given to the Parrys by Mr Dent. Isabella told her mother that ‘the children have appropriated it for their amusement, and it has to perform many a voyage to England! They very often beg me to come in with them to “go” to England to fetch toys and dolls’.Footnote79 Even for the infant Parry children who had been born in the colony, England occupied a singular place in their imagination and was tied to understandings of familial gift giving.

Figure 4. ‘Front elevation of Tahlee House’, Isabella Louisa Parry, 31 January 1831, Scott Polar Research Institute, Y:77/4/1. Images reproduced with the permission of the Scot Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge.

Figure 5. ‘Tahlee House, Port Stephen, birthplace of Lucy and Charles Parry’, Isabella Louisa Parry, c.1830–1834, Scott Polar Research Institute, Y: 77/4/14. Images reproduced with the permission of the Scot Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge.

Tending to the garden at Tahlee House was another way Parry attempted to exert control over her environment and maintain familial connections, regularly sending natural history specimens in packages to Alderley, and receiving English seeds in return.Footnote80 She told Louisa in her first letter from Port Stephens that ‘You may imagine how very often I long for you when busy gardening’.Footnote81 In her study of the relationship between gardens and Australian settler womanhood, Katie Holmes has articulated how gardening can be considered akin to letter writing and ‘individual acts of biography’.Footnote82 Indeed, gardens and their growth could be seen to reflect one’s inner world, and Parry’s natural history collecting can be thought of in this way. She formed contacts with the Botanical Garden in Sydney and acquired seeds and plant cuttings from around Carrington, sending specimens to her sister and mother, and allowing them to plant pieces of herself at Alderley. For Parry, the garden came to provide respite for her and her children, protecting them from moral anxieties brought by proximity to the Company settlement. Parry again showed her adoption of colonial vocabulary – spanning India as well as Australia – when writing that the garden and ‘Verandah [are] delightful for the Picanninies to play in, as they can be turned loose in it, without danger’.Footnote83

After leaving Tahlee to visit the inland settlement of Stroud, Parry told her mother that ‘This is not a country that I like to leave home for long, as one never can feel sure that all will continue quiet and without alarm, when surrounded by such characters’.Footnote84 Parry admitted to Louisa that unless their neighbours ‘very much changed, we are not likely to become too much attached to it, so as to wish to remain here’. She wrote, ‘it is indeed to be lamented that the moral world should be so bad when the natural world is so beautiful’.Footnote85 While Tahlee had become a refuge for Lady Parry whose fears were tied to her sense of responsibility as a wife and new mother, establishing a ‘home’ unmarred by anxieties of the outside world proved unattainable.Footnote86 The garden and surrounding environs could also not be easily manipulated. While finding the native flora remarkable, Parry saw the bush as exemplifying unfamiliarity. She told Louisa that while the trees are ‘a much prettier green than I expected and indeed look like English deciduous trees’, the similarities vanished the closer she came, as the ‘long straggling white barked naked looking gum trees shew [sic] they are foreigners’.Footnote87 Parry also found the English seeds she received from her family could not take root in the garden, lamenting to her mother that ‘English seeds are very difficult to rear, they … often come up, but then whither [sic] away’.Footnote88 Existing on the boundary zones of the Company settlement, Tahlee could not be the haven of moral protection Parry sought, and instead became a mirror to her ambivalence.

Conclusion

The final package Parry sent to Alderley Park demonstrates the extent of her domestic network and the way objects enabled her to remain linked to community in England. While she prefaced to her mother that ‘I have filled the box with everything I could procure and hope each person will make allowance for the trifling quality’, it included emu eggs, numerous native birds and reptiles, Māori artefacts and a range of Aboriginal objects including woven nets, a bark shawl, clubs, and a boomerang. At Lady Parry’s request, Edward penned a careful inventory of the parcel’s contents, to which she added annotations signalling to whom each object was gifted.Footnote89 The names on this list range from members of the Stanley and Parry families to friends and acquaintances. Here, in Parry’s final year at Port Stephens, assembling and distributing packages of material culture continued to serve as a conduit to her sorely missed social world.

Three months after Parry posted the final package, she confided to her diary that:

Daily more and more do I rejoice that our last year has arrived … I am afraid of this country and always feel as if there was something hanging over one of a fearful or trying nature. A feeling of anticipated evil … and it causes a constant weight on my spirits.Footnote90

Despite her best attempts to project a sense of ownership over her colonial experiences and construct a domestic sanctuary while in Port Stephens, Lady Parry’s diaries and letters reveal that the Company estate continued to impinge on her sense of safety and belonging. While enjoying moments of respite in the days spent raising her children in Tahlee House and gardens, she remained distant from any sense of community. The act of assembling and distributing letters and packages to her family quickly became a means through which she could exercise control over her surroundings. By converting this uneasy sense of ownership into the act of giving, Parry strove to remain attached to the familial networks of England, necessarily compartmentalising and distancing herself from social life at Port Stephens.

By returning to Worimi objects in the British Museum attributed to Edward Parry, this article has generated insight into Lady Isabella Parry and her life in the Hunter region. Through an analysis of her overlooked personal archive, I have illuminated the importance of material culture and gift-giving to imperial women’s identity formation. Parry’s writings and material legacy additionally speak to the value ascribed to objects within imperial families and contribute to building knowledge about extant Aboriginal artefacts that continue to be found across Britain and Europe. This article has also sought to show what museum records often eclipse – the role of women as distributors, if not direct collectors – of colonial-era material culture.

I gratefully acknowledge Professor Gaye Sculthorpe for assisting aspects of this research and facilitating my contact with collections.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 1 February 1831, MS438.25.82, Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, UK. All correspondence from Isabella Parry quoted in this article is from this archive unless otherwise indicated.

2 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 5 February 1831.

3 These objects are available to view on the British Museum’s online collections search and include four fishhooks (Oc1926,0313.16-19), three fishing spears (Oc1926,0313.34-36), and a shield (Oc1926,0313.37), most likely collected from the Worimi at Port Stephens.

4 Frederick Sydney Parry, Letter to Mr Braunholtz of the British Museum 11 February 1926, British Museum Correspondence 1926, British Museum Archives, UK.

5 Frederick Sydney Parry, Letter to Mr Braunholtz of the British Museum 14 February 1926.

6 Gaye Sculthorpe, Maria Nugent, and Howard Morphy, eds. Ancestors, Artefacts, Empire: Indigenous Australia in British and Irish Museums (London: British Museum Press, 2021), 18.

7 Academic work within this tradition includes: Philip Jones, Ochre and Rust: Artefacts and Encounters on Australian Frontiers (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2007); Sculthorpe, Nugent, and Morphy; Daniel Simpson, The Royal Navy in Indigenous Australia, 1795–1855: Maritime Encounters and British Museum Collections (Engham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020); Tiffany Shellam, Meeting the Waylo: Aboriginal Encounters in the Archipelago (Perth: UWA Press, 2020); Jason M. Gibson, Ceremony Men: Making Ethnography and the Return of the Strehlow Collection (Albany: SUNY Press, 2020).

8 These writings are held at the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge and labelled MS 438. A transcript of Isabella Parry’s diary can also be found at the University of Newcastle’s Special Collections Reading Room, titled Journal of Lady Isabella Louisa Parry, 1830–1834.

9 See, for example: Zoë Laidlaw, Colonial Connections, 1815–45: Patronage, the Information Revolution and Colonial Government (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005); David Lambert and Alan Lester, eds., Colonial Lives across the British Empire: Imperial Careering in the Long Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Desley Deacon, Penny Russell, and Angela Woollacott, eds., Transnational lives: biographies of global modernity, 1700-present (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

10 Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden, and Ruth B. Phillips, eds., Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums, and Material Culture (New York: Berg, 2006), 3.

11 For more on objects and biographies, see: Igor Kopytoff, ‘The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process’, in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); Chris Gosden and Yvonne Marshall, ‘The Cultural Biography of Objects’, World Archaeology 31, no. 2 (1999), 169–178; Kate Hill, ed., Museums and Biographies: Stories, Objects, Identities (Martlesham: Boydell & Brewer, 2012). Rosemary A. Joyce and Susan D. Gillespie, eds., Things in Motion: Object Itineraries in Anthropological Practice (Santa Fe: Santa Fe Press, 2015).

12 Erica Y. Hayes and Kacie L. Wills, ‘Sarah Sophia Banks’s Coin Collection: Female Networks of Exchange’, in Women and the Art and Science of Collecting in Eighteenth-Century Europe. The Histories of Material Culture and Collecting, 1700–1950, ed. Arlene Leis and Kacie L. Wills (Milton: Taylor and Francis, 2020).

13 For more on Owen Stanley, see Simpson. The Linnean Society of London was founded in 1788 and dedicated to the study of natural history. It excluded women from its membership until 1904. See: ‘List of the Officers of the Linnean Society, Past and Present’, Proceedings Linnean Society London 111, no. 1 (1899), 1–64; ‘Celebrating the First Women Fellows of the Linnean Society of London’, https://www.linnean.org/news/2018/03/20/20th-february-2018-celebrating-the-first-women-fellows-of-the-linnean-society-of-london (accessed 10 June 2021).

14 Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, ‘Alice Margaret Stanley (1828–1910), Wife of Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers’, Rethinking Pitt-Rivers: Analysing the Activities of a Nineteenth Century Collector, https://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/rpr/index.php/article-index/12-articles/342-alice-pitt-rivers.html (accessed 10 June 2021).

15 Annaliese Jacobs, ‘Arctic Circles: Circuits of Sociability, Intimacy, and Imperial Knowledge on Britain and North America, 1818–1828’, in Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony: Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim, ed. Penelope Edmonds and Amanda Nettelbeck (Cham: Springer 2018).

16 Nancy Mitford, ed., The Stanleys of Alderley: Their Letters between the Years 1851–1865 (London: H. Hamilton, 1968); Baroness Maria Josepha Stanley, The Ladies of Alderley: Being the Letters between Maria Josepha, Lady Stanley of Alderley and Her Daughter-in-Law Henrietta Maria Stanley during the Years 1841–1850, ed. Nancy Mitford (London: H. Hamilton, 1967).

17 Ann Parry, Parry of the Arctic; the Life Story of Sir Edward Parry, 1790–1855 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1963).

18 ‘Isabella Louisa Parry, Cowper Street, St John the Evangelist Anglican Church, Stroud, 2425’, https://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/people/settlement/display/94103-isabella-louisa-parry (accessed 20 May 2021); Paul Struan Robertson, Proclaiming ‘Unsearchable Riches’: Newcastle and the Minority Evangelical Anglicans, 1788–1900, Monographs in Australian Christianity (Sydney: Gracewing, 1996); Andrew Kyrios, ‘How the Evangelical Convictions of Sir William Edward Parry Influenced His Running of the Australian Agricultural Company from 1829 to 1834’, Integrity: A Journal of Australian Church History 5 (2019), 1–10.

19 ‘Women in Australian History: An Early Lady-Bountiful’, The Australian Women’s Mirror, 2 July 1941, 29.

20 See, for example: Rebecca Earle, ed., Epistolary Selves: Letters and Letter-Writers, 1600–1945 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999); Felicity Berry, ‘“Home Allies”: Female Networks, Tensions, and Conflicted Loyalties in India and Van Diemen’s Land, 1826–1849’, Journal of World History 26, no. 4 (2015): 757–84; Penny Russell, ‘“Unhomely Moments”: Civilising Domestic Worlds in Colonial Australia’, The History of the Family 14, no. 4 (2009), 327–339; Penny Russell, ‘In Search of Woman’s Place: An Historical Survey of Gender and Space in Nineteenth-Century Australia’, Australasian Historical Archaeology 11 (1993), 28–32.

21 Penny Russell, ‘Wife Stories: Narrating Marriage and Self in the Life of Jane Franklin’, Victorian Studies 48, no. 1 (2005): 39.

22 An attempt was made to publish Isabella Parry’s diaries in 1983 by Percy Haslam but, following his death, the plan never eventuated. See John Maynard, ‘Awabakal Voices: The Life and Work of Percy Haslam’, Aboriginal History 37 (2013), 77–92.

23 Isabella Parry, Letter to Miss Louisa Stanley 13 May 1830.

24 Isabella Parry, Diary Entry October 1830.

25 Angela Woollacott, Settler Society in the Australian Colonies: Self-Government and Imperial Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 12–36.

26 Robertson, 2.

27 Isabella Parry, Letter to Harriet Alethea Scott (Nee Stanley) 25 October 1831.

28 Alan Lester, ‘British Settler Discourse and the Circuits of Empire’, History Workshop Journal 54 (2002), 24–48; Alan Lester, ‘Colonial Settlers and the Metropole: Racial Discourse in the Early 19th-century Cape Colony, Australia and New Zealand’, Landscape Research 27, no. 1 (2002), 39–49.

29 Damaris Bairstow, A Million Pounds, A Million Acres: The Pioneer Settlement of the Australian Agricultural Company (Sydney: D. Bairstow, 2003), 38.

30 Australian Agricultural Company, Annual Report Read at the Third Annual General Court of Proprietors, Held at the Office of the Company, No. 12, King’s Arms Yard, London, John Smith Esq., M.P., in the Chair., Mitchell Library 630.6/A (London, 1827). See also Lyndall Ryan, ‘The Australian Agricultural Company, the Van Diemen’s Land Company: Labour Relations with Aboriginal Landowners, 1824–1835’, in Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony: Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim, ed. Penelope Edmonds and Amanda Nettelbeck (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 32.

31 Robert Dawson, The Present State of Australia; A Description of the Country, Its Advantages and Prospects, with Reference to Emigration: And a Particular Account of the Manners, Customs and Conditions of its Aboriginal Inhabitants, 1830 (Alburgh: British Library Archival Facsimiles, 1987), 26.

32 James Macarthur, James M’Arthur’s Report to the Committee, Statement of the Services of Mr. Dawson as Chief Agent of the Australian Agricultural Company; with a Narrative of the Treatment He Has Experienced from the Late Committee at Sydney, and the Board of Directors in London, (1829), xv.

33 P.A. Pemberton, Pure Merinos and Others: The ‘Shipping Lists’ of the Australian Agricultural Company (Canberra: Australian National University Archive of Business and Labour, 1986); William Edward Parry, In the Service of the Company: Letters of Sir Edward Parry, Commissioner to the Australian Agricultural Company, vol. 2: June 1832–March 1834 (Canberra: ANU Press, 2004), xiv.

34 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Josepha Stanley 23 April 1830.

35 Isabella Parry, Letter to Caroline Bridget Martineau (Nee Parry) 25 August 1831.

36 Isabella Parry, Diary Entry 25 February 1831.

37 Isabella Parry, Diary Entry 28 February 1831.

38 Isabella Parry, Diary Entry 25 February 1831.

39 See, for example: Bruce Elliott, David Gerber, and Suzanne Sinke, eds., Letters across Borders: The Epistolary Practices of International Migrants (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006).

40 Isabella Parry, Letter to Miss Louisa Stanley 29 December 1830.

41 Isabella Parry, View on Top of the Hill at the Back of Tahlee, Near Prospect Place (c.1830–1834), Y: 77/4/8; Isabella Parry, View of Tahlee House on the West Side, Coming from Sawyer’s Point, 28 August 1832, Y: 77/4/3.

42 Isabella Parry, Letter to Miss Louisa Stanley 29 December 1830.

43 Shino Konishi, The Aboriginal Male in the Enlightenment World (London; Brookfield: Pickering & Chatto, 2012).

44 Isabella Parry, Letter to Caroline Bridget Martineau (Nee Parry) 10 June 1830.

45 Isabella Parry, Letter to Miss Louisa Stanley 29 December 1830.

46 McBryde, ‘“Barter … Immediately Commenced to the Satisfaction of Both Parties”: Cross-Cultural Exchange at Port Jackson, 1788–1828’ in The Archaeology of Difference: Negotiating Cross-Cultural Engagements in Oceania, ed. Anne Clarke and Robin Torrence (Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2000); Tiffany Shellam, Shaking Hands on the Fringe: Negotiating the Aboriginal World at King George’s Sound (Perth: UWA Press, 2009).

47 Grace Karskens, ‘Red Coat, Blue Jacket, Black Skin: Aboriginal Men and Clothing in Early New South Wales’, Aboriginal History 35 (2011): 1–36.

48 Isabella Parry, Letter to Maria Margaret Stanley 4 November 1831.

49 Isabella Parry, Letter to Caroline Bridget Martineau (Nee Parry) 9 July 1831.

50 For more on gendered and colonial practices of naming, see: Liz Conor, Skin Deep: Settler Impressions of Aboriginal Women (Perth: UWA Publishing, 2016).

51 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Josepha Stanley 28 August 1830.

52 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Josepha Stanley 18 October 1830.

53 Ibid.; and Isabella Parry, Letter to Harriet Alethea Scott (Nee Stanley) 25 October 1831.

54 David Gerber, ‘Epistolary Masquerades: Acts of Deceiving and Withholding in Immigrant Letters’, in Elliott, Gerber, and Sinke, 43.

55 As Daniel Simpson observes, ‘Australia was a constant and inextricable feature of British imperial thinking and planning from the late eighteenth to the late nineteenth century’: Simpson, 2.

56 The National Museum of Australia now holds the Stanley family’s two-volume copy of ‘An Account of the English Colony in NSW: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country’. The bookplate lists Isabella’s father, Sir John Thomas Stanley, and ‘Alderley Park’. National Museum of Australia, David Collins ‘An Account of the English Colony in NSW’ (1798) Volume 1, First Edition 2004.0050.0001.001 (Canberra, Australia); National Museum of Australia, David Collins ‘An Account of the English Colony in NSW’ (1802) Volume 2, First Edition, 2004.0050.0001.002 (Canberra, Australia).

57 Isabella Parry, Letter to Miss Louisa Stanley 29 December 1831.

58 Nicholas Thomas, Colonialism’s Culture: Anthropology, Travel and Government (Oxford: Polity Press, 1994), 2.

59 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 1 February 1831.

60 Isabella Parry, Letter to Maria Margaret Stanley 1 January 1831.

61 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 1 February 1831.

62 Ronald Rainger, ‘Philanthropy and Science in the 1830’s: The British and Foreign Aborigines’ Protection Society’, Man (London) 15, no. 4 (1980): 703; Graeme Davison, ‘Exhibitions’, Australian Cultural History 2 (1982–83), 5–21; Kate Darian-Smith, ‘Introduction’, in Seize the Day: Exhibitions, Australia and the World, ed. Kate Darian-Smith (Melbourne: Monash University ePress, 2008).

63 Nicholas Thomas, Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991), 126.

64 Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 1 February 1831.

65 Shino Konishi, ‘“Wanton With Plenty” Questioning Ethno-historical Constructions of Sexual Savagery in Aboriginal Societies, 1788–1803’, Australian Historical Studies 39, no. 3 (2008), 356–372.

66 As Maria Nugent identifies, ‘the spread of objects [within museums] is selective, weighted much more in favour of men’s material culture than women’s, and with an obvious emphasis on martial activities’. Maria Nugent, ‘Travels with Bennelong: Collecting in Early Colonial Sydney’, in Sculthorpe, Nugent, and Morphy, 58.

67 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 23 January 1832.

68 Isabella Parry, Letter to Miss Louisa Stanley 9 July 1832.

69 As Antionette Burton has usefully articulated, ‘domesticity is a fundamentally networked phenomenon’. Antoinette Burton, ‘Toward Unsettling Histories of Domesticities’, American Historical Review 124, no. 4 (October 2019): 1332.

70 Kate Smith, ‘Warfield Park, Berkshire: Longing, Belonging and the British Country House’, in The East India Company at Home, 1757–1857, ed. Margot C. Finn and Kate Smith (London: UCL Press, 2018), 175–190.

71 ‘Marriage of Captain Parry’, Chester Chronicle, 26 October 1826.

72 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 1–5 February.

73 William Edward Parry, In the Service of the Company, vol. 2, 148.

74 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 25 June 1831.

75 Penny Russell, Savage or Civilised?: Manners in Colonial Australia (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2011), 29.

76 Isabella Parry, Front Elevation of Tahlee House, 31 January 1831; Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 10 March 1831.

77 Isabella Parry, Tahlee House, Port Stephen, Birthplace of Lucy and Charles Parry (c.1830–1834).

78 Joan Kerr, ‘Same but Different’, in Past Present: The National Women’s Art Anthology, ed. Joan Kerr and Jo Holder (Sydney: Craftsmen House, 1999), 16.

79 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 30 August 1832.

80 As Richard Neville has explained, colonial collectors rarely made distinctions between material culture and natural history. See: Richard Neville, A Rage for Curiosity: Visualising Australia 1788–1830 (Sydney: State Library of New South Wales Press, 1997). Economic botany was also bound up in similar scientific and social networks to ethnographic material culture. For more on economic botany, see: Caroline Cornish and Felix Driver, ‘“Specimens Distributed”: The Circulation of Objects from Kew’s Museum of Economic Botany, 1847–1914’, Journal of the History of Collections 32, no. 2 (2019), 327–340.

81 Isabella Parry, Letter to Miss Louisa Stanley 13 May 1830.

82 Katie Holmes, Between the Leaves: Stories of Australian Women, Writing and Gardens (Perth: UWA Publishing, 2011), 4.

83 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 10 March 1831.

84 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 17 March 1831.

85 Isabella Parry, Letter to Miss Louisa Stanley 10 September 1830.

86 Russell, ‘“Unhomely Moments”’, 327.

87 Isabella Parry, Letter to Miss Louisa Stanley 13 May 1831.

88 Isabella Parry, Letter to Lady Maria Stanley 8 March 1832.

89 Edward and Isabella Parry, Inventory of Things Sent in the Box by the City of Edinburgh, in Letter to Lady Maria Stanley Febuary 1833.

90 Isabella Parry, Diary Entry 28 May 1833.

91 Isabella Parry, Diary Entry 10 June 1833.