Abstract

Conservation practice increasingly seeks to include community participation. This article reflects on such a collaborative process, through the case study of the community-driven conservation of a stage curtain painted in 1897 for the Mechanics Hall of Bullumwaal, a remote township in the state of Victoria (Australia). From fundraising efforts and navigating grant applications to managing the conservation project, the challenges faced by the local community in order to conserve their curtain and keep it in situ are examined in light of current heritage preservation policies and practices. Close collaboration with the conservators and flexibility with all preconceived plans resulted in a successful negotiated outcome that respected both community values and ethics of preservation. Social events are now planned to advertise the curtain’s presence and attract people to the township. The conservation treatment also triggered more research by local historians, expanding knowledge about the place and its people and opening the Bullumwaal community to new connections with other parts of Victoria. This case illustrates the importance of living cultural heritage within a community and conservation’s contribution to strengthen identity, social cohesion and sense of place through the preservation process.

Introduction

Community participation has been a prevalent concept in conservation in recent years. Moving away from a focus on materiality towards an emphasis on participatory practices of engagement (Bentshop et al. Citation2022), the profession now calls for conservators to consult and collaborate with the communities, particularly for objects from Indigenous and World Cultures, acquired through past colonial practices and considered as living cultural objects by their source communities (Sully Citation2007). This new focus also involves reflections around knowledge ownership and access to objects (Smith & Ngarimu Citation2021). These issues of living heritage, knowledge ownership and access are equally relevant to community-run museums or historical societies, and the recent years have seen conservators working for these institutions recognising communities’ authority on the meaning of the objects, and shifting to a practice sharing power and knowledge with non-professionals to enhance understanding of the collections and their conservation needs (Scott & O’Connell Citation2020, Sloggett & Middleton Citation2018, Lewincamp & Sloggett Citation2016).

However, living heritage understood here as heritage in use, is often not located within an institution such as a museum or historical collection. While a part of living heritage is of a religious or spiritual nature, located and cared for in places of worship, some secular objects embody local historical and social significance and carry meanings sustained and enhanced by the fact that they live within the community they belong to. This is the case of the Bullumwaal stage curtain presented here as a case study; commissioned during the second Gold Rush (1890s), when the township was flourishing, it has remained in the town’s Mechanics Hall since 1897, and been the backdrop of many community events, retaining its historical significance through time and the gradual fading of the town’s population. Its recent conservation in 2022, an entirely community-driven project, illustrates the impact of a ‘grassroots community-based preservation initiative’ (Avrami Citation2009) in adapting practice to maintain the continuity of status and use of a significant object anchored in the place’s identity.

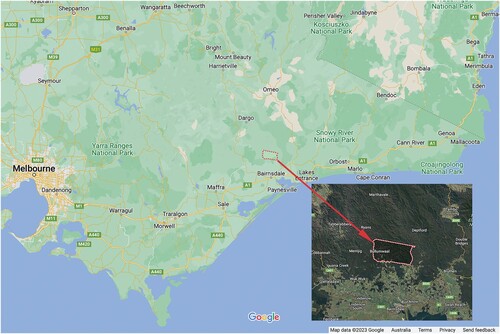

HISTORICAL CONTEXT Bullumwaal (East Gippsland, Victoria) is located along Boggy Creek, twenty-nine kilometres north of Bairnsdale (). The traditional owners are the Gunaikurnai people.

Following the discovery of gold in the creeks and local rivers in 1857, the Boggy Creek was extensively prospected and alluvial mining easily stripped sought after gold from the river. A small township named Allanvale, later Boggy Creek, grew up at the creek crossing. In 1868, there was a rush to Upper Boggy Creek where promising reefs were found. In 1870, this growing township was renamed Bullumwaal, an Aboriginal word thought to mean ‘two spears’, representing two nearby mountains, Mt Lookout and Mt Taylor. Almost deserted by the early 1880s, the Boggy Creek mines were reopened a few years later when the economic depression caused many unemployed to migrate to old goldfields (Victorian Places Citation2015).

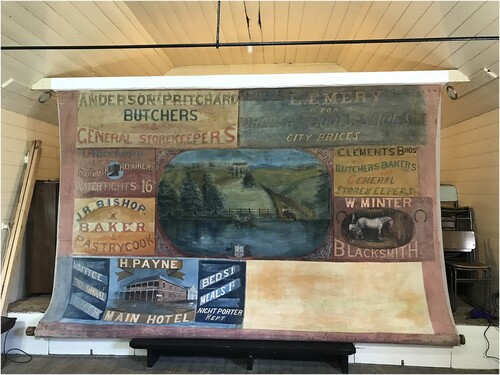

By the late 1880s and into the 1890s the community was flourishing, with the establishment of substantial quartz mines and several quartz processing batteries operating in and near the township. From 150 residents in 1890, the population swelled to 700 by 1896. The township was gazetted in 1898. Staggered over several kilometres, it then possessed a post office, telephone service, hotel, school, church, Mechanics’ Institute Hall, coffee palace, drapers, jeweller, grocer, other stores and a newspaper (Victorian Places Citation2015). With an increased population, social activities became an important part of the community and included cricket and football clubs, sports and picnic days, as well as music and drama clubs. Social dances and fundraising were popular activities, and it is believed that the Mechanics Hall’s stage curtain was created to support just such an event. The curtain, as attested by a date discovered during the conservation treatment, was made in 1897, the same year that the township changed its name from Boggy Creek to Bullumwaal, and may well have been linked to this event, as a ‘Monster Bizarre’ and fundraising event was documented in the Bairnsdale Advertiser in June 1897. The presence of an Australian coat of arms at the centre of the curtain with the motto ‘Advance Bulumwaal’ (another spelling of the town’s name) fits this hypothesis.

Local businesses from Bairnsdale and Bullumwaal appear on the stage curtain, around a central landscape and include F Raymond, Bootmaker; J R Bishop, Baker; H Payne of the Main Hotel, Bairnsdale; Clements Bros, General Storekeepers; and W Minter, Blacksmith. The artist signature on the curtain is F Winters. The names of Anderson & Pritchard Butchers; L Emery, Drapery were also revealed during conservation treatment, when the top batten masking the words was dismounted.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Bullumwaal's mining industry began to decline, which reflected on the town. After a short revival in the 1920s, which saw the local social life resuming and the church and school reopened, almost all mining ceased with the coming of World War II. (Victorian Places Citation2015). The buildings were gradually dismantled and today the Mechanics Hall is the only surviving public building in Bullumwaal.

The stage curtain, still in its original place, had been deteriorating but in the last twenty years fading increased significantly and tears had become more obvious (Fleischer Citation2023; Hocking Citation2023); there is evidence of ‘repair’ of a torn upper edge by moving the wooden batten further down in the composition, resulting in masking the top of the panels (see ). These different types of damage threaten the integrity of this unique cultural heritage, one of the only examples left in Victoria.

Figure 2. (a) Detail of tear on the lower right corner. (b) Detail of top left corner with fading and stains. (c) Detail of upper left part with extensive fading, and letters masked by wooden batten. (d) Curtain unrolled before conservation treatment, note extensive fading on both sides, images S Cotte and S Vardy.

The curtain has been an icon of the community for many years and is spoken about with pride (‘It’s not something that anybody else has … I want it there for my kids and grandkids’ Fleischer Citation2023). The Bullumwaal Mechanics Hall Committee of Management (hereafter described as ‘Hall Committee’) have been passionate about it for a long time and care deeply about preserving it, as it holds special significance for the people of Bullumwaal and the broader local community.

History of fundraising

The curtain always had a significant status in the community and was never removed, even as the town dwindled in numbers and the hall was much less used. Perhaps one of the reasons the curtain has maintained this level of respect and remained in the hall is due to the efforts of a local couple, Lionel Palling and his wife Lil (d. 2017) who were on the committee for approximately 60 years (circa 1950–2009) and can be credited for keeping it alive. The Pallings, very active in the community, were very passionate about history; L Palling remembers the curtain being a backdrop to dances and school events. This passion has been passed down to the subsequent committees and is at the origin of the fundraising efforts that started around 2000.

Numerous iterations of the committee have searched various avenues to apply for funding, but there has always been a caveat: funding may be granted if the curtain was removed from the hall and stored in an institution (Fleischer Citation2023; Hocking Citation2023). However, this did not align with the wish of the community, and the committee remained ‘very very strong’ in their desire to maintain the curtain in its original location (Hocking Citation2023). For 125 years, the curtain has hung in the one building that still remains, and witnessed the boom and bust of Bullumwaal, from a crowded town of 700 to a small community of 30 people. Although the Hall Committee has changed as some ageing residents have moved on to be closer to facilities, and new residents have joined the tight-knit community, all of them have respect and pride for the curtain.

Local residents Phil Large, then Nadine Fleischer joined the committee in 2003 and 2013 respectively, and realised the significance of the curtain and the need for its preservation. Their fundraising efforts were still met with disappointing results ‘it was a single item and wasn’t part of a collection; therefore, it didn’t qualify for a lot of grants’ (Fleischer Citation2023).

In 2013 Nadine Fleischer contacted conservator Sabine Cotte who assisted in developing a significance assessment which comprehensively documented the condition of the curtain and outlined a treatment proposal. This significance assessment was used to support—unsuccessfully—a Community Heritage Grant applicationFootnote1 and other local grant applications submitted by the committee. In 2020, the Hall Committee joined forces with the East Gippsland Historical Society (EGHS), who submitted another Community Heritage Grant application on behalf of the Bullumwaal Hall Committee but still without success.

Members of the East Gippsland Historical Society connected with Heritage Victoria’s Bushfire Recovery team, when they spoke at an event hosted in Bairnsdale by Heritage Network East Gippsland (HNEG) in early 2021. Members from EGHS were able to make contact with Jo Lyngcoln of Heritage Victoria (HV) and an invitation was extended to the Heritage Network to come and view the curtain so the Hall Committee and EGHS could seek advice and discuss options on how to move forward on grant-seeking to conserve the curtain. On 29 April 2021, a visit was arranged to view the curtain in the Bullumwaal Mechanics Hall. Those who attended were Helen Kiddell, Senior Heritage Officer (HV, Bushfire Recovery), Jenny Dickens, Heritage Officer (HV, Materials Conservation) and Jo Lyngcoln, Manager HV-Bushfire Recovery, as well as Tracey West, Land and Built Environment officer in Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP).Footnote2 Also attending was Helen Martin, a local historian and former Heritage Council member, the Bullumwaal Hall Committee members, as well as representatives of EGHS who provided historical information and a tour of the local area.

The visit was well received and generated many conversations between the different entities, the result being that in August 2021 the Hall Committee was elated to receive a grant of $20,000 from DELWP’s Land and Built Environment to conserve the curtain, under their own Bushfire Recovery Program. Although it wasn’t exactly bushfire ‘recovery’, this can be considered as ‘preventive’ lateral thinking from DELWP, since the curtain was evacuated in 2019 and given the increased frequency of bushfires due to climate change, it will most likely be evacuated again in the future.

The Hall Committee was able to engage conservators Sabine Cotte and Sherryn Vardy and arrangements were made to undertake the curtain conservation in March 2022. Members of the Bullumwaal community, the Hall Committee and EGHS assisted the conservators throughout the project, by providing volunteer labour, equipment, and homemade refreshments to help achieve the project, which was completed in two intensive weeks.

Community, heritage and policies

The Bullumwaal community

Today the community of residents in Bullumwaal is very small, around 30 people including children. Most families work in town (Bairnsdale) which is where the children now go to school, but commute every day. The shifting demographics are linked to historic, economic and social circumstances; however, some of the previous residents are still very much part of the community. The Hall Committee has 9 members, 4 currently living in Bullumwaal and 5 living outside the township, showing that the significance of the curtain resonates well beyond the township itself. The community is very tight-knit (’we really help each other when we need to’ says Nadine Fleischer) and this was felt by the conservators throughout the whole project.

While most traces of the previous buildings have disappeared, their materials having been reused or sold, and the two mines (Beehive and Sons of Freedom) are currently not visited, residents are still passionate about the history of the town and have many small objects, photos and memorabilia from that time, that give tangible presence to the past. The now-conserved curtain is the jewel of this past and a source of pride for the community. In addition, there is still a strong interest in alluvial gold mining, with casual gold diggers regularly coming to town on the weekend and trying their luck in the creek and the forest. This consolidates the ‘living tradition’ character of the town’s cultural heritage.

Heritage preservation policies

While in theory stakeholders’ participation is encouraged during conservation processes, it remains the case that the framework of economic assistance—through state or federal grants mainly—operates within a certain idea of what heritage is, and how best to care for it. Within this framework, the expertise is located with the institution and heritage professionals—what Laurajane Smith has defined as ‘authorised heritage discourse’ (Smith Citation2006). In this discourse, heritage is material, monumental, aesthetically pleasing and contributes to group identity, all criteria that apply well to the Bullumwaal curtain. Indeed, the community is deeply attached to the curtain, because ‘it shows the life of the people who lived here back in the day, it gives us the opportunity to find out more about them, what they did when they lived here and how they were part of their community’ (Fleischer Citation2023). The local heritage structure is also in compliance with this framework; Heritage Network East Gippsland (HNEG), established in 1996 to represent historical societies and family history groups across the region, includes EGHS as a member. DELWP is also the overseeing body for the Mechanics Hall. Through these cross links, it seems that the curtain was known to people in Heritage Victoria since around 1990 (Hocking Citation2023). HV did not have an official record of the curtain, but staff in the Bushfire Recovery team had noted it was included in the 2005 East Gippsland Shire Council Heritage Gaps StudyFootnote3 as being potentially of state significance, before it was mentioned at the HNEG meeting. Janette Hodgson, DELWP’s Historic Places Officer in the Lands Department also had a file on the hall, with a few lines of information, which she shared with the Bushfire Recovery Heritage Program prior to their visit to Bullumwaal in 2021. The undated record card notes that the hall ‘features a curtain which is particularly prized, because it is painted with advertisements for various nineteenth century businesses of Bullumwaal and Bairnsdale’ (Historic Places, Citationn.d.).

However, the difficulties encountered by the Bullumwaal Hall Committee to secure funding for the curtain’s conservation show that things are not so easy when the community and/or the heritage object do not fit the pre-existing assumptions of heritage preservation frameworks and when their desires do not coincide with the supposedly universal heritage values contained in these frameworks (Waterton & Smith Citation2010). In ‘authorised heritage discourse’, the expertise and the decision-making power belong to heritage professionals, the community being consulted instead of driving the process. The paperwork reflects this mind set. Grant applications are not easy to complete for communities not well versed in cultural heritage language and practices, which can be discouraging; Nadine Fleischer remembered the first time she completed a grant application as something ‘way above my head … it was like jumping in a shark’s pool’ (Fleischer Citation2023). The very small size of the community might be detrimental to grant success from the institution’s perspective, but it is also a factor of social cohesion around the curtain:

being such a small community, it is really important for us … I kind of don’t want Bullumwaal to be forgotten. It had a pretty good history in the past, we are just building on that. (Fleischer Citation2023)

In placing the location of the curtain in the hall as a pre-condition for its conservation, the community asserts their ownership of their cultural heritage, and that rural societies can and indeed want to care for their cultural material. The committee holds these views very firmly, against the centralised claims of state institutions, even if it meant repeated rebukes of their funding efforts for its conservation. As mentioned previously, institutions contacted by the Hall Committee before 2013 (such as Museum Victoria and Bairnsdale Museum) could only finance conservation if the curtain was donated to them; feedback from grant applications was that the curtain’s ownership was unclear and public access to the Hall not guaranteed. It took some ‘out of the box’ thinking from one of DELWP departments to allocate funding for the curtain’s preservation, under a program that did not at first glance seem the most adequate for this object. The Hall Committee’s position and its consequences during two decades brings into question whether it was their strategy or the heritage framework that was inadequate. The following sections will discuss this jointly run project done with the community, not only for the community, as often occurs in heritage practice (Smith & Waterton 2010).

Community-led conservation When finally securing funding, the Hall Committee embraced its responsibility to conserve the curtain by stating their expectations, but also by establishing a respectful dialogue with the conservators and the funding body, where each type of expertise was acknowledged but decisions were discussed in shared capacity and weighted against the community’s broader project for the curtain and the hall. Indeed, the conservation process itself, done in situ, created another opportunity to fulfil the social role of the hall and its curtain; the conservators used the hall to give a public talk on the curtain treatment (at the time near completion) to the broader community, including past members of the committee who now live outside the township, amongst them a very happy Lionel Palling.

While the committee is unapologetic about their authority over the curtain (‘it was important that we understood the process as a whole, and had control of it’) (Fleischer Citation2023), they are also very conscious of their responsibility to facilitate access to the hall and the curtain, saying ‘we are the custodians, we are not the owners, we are just looking after it’ (Fleischer Citation2023). The committee is planning to hold future events regularly (within their capabilities), preferring to invite people to visit remote places rather than relocating their cultural heritage in cities at the expense of its local significance.

Who is the community?

In many instances of community participation in heritage conservation, the question arises of how representative the chosen consultants are (Henderson & Nakamoto Citation2016; Johnson et al. Citation2005), since community is a very fluid and heterogeneous concept (Waterton & Smith Citation2010). These questions mainly recognise power relationships and differences of opinion within the community, and how they could impact on its expectations for cultural heritage and its role.

In the case of Bullumwaal, the risk is significantly reduced for two reasons: first, the roles are reversed as it is the community who consulted the conservators, and who has done their due diligence on the choice of professionals, since both are Professional Members of the Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Materials (PMAICCM) and therefore abide by AICCM Codes of Ethics and best professional practice.

Secondly, the very small size of the Bullumwaal’s township population compared with the size of the Hall Committee greatly reduces the risk of the committee not reflecting the wishes of the community. Furthermore, the intricate network of family relationships within the community ensures that its members participate in the conservation project if their skills are needed, regardless of their status or membership of the Hall Committee. While power hierarchies may be different in the community and in the curtain project, leaders collaborated with their time and skills towards a common goal, and conservators were hired as consultants and skilled practitioners. The project grew to include other members of the broader local community such as the EGHS, recognising their expertise, knowledge and the weight they can carry in the fundraising efforts. The hall and its contents, particularly the curtain, are the Hall Committee’s reason for being, alongside the remains of the goldmines and the scattered traces of occupation of the township in its heyday. Managing this conservation project successfully provides recognition to the Hall Committee and consolidates its status in the local associative network, enabling it to plan future actions and developments in relation to the curtain.

Community agency

Central to this project is the recognition of the community’s ownership of the curtain conservation process, including decision-making, maintenance and evacuation measures if necessary. It took the ‘spontaneous’ evacuation of the curtain by a concerned member of the community in the Black Summer fires (2019–2020), which highlighted both its importance to the community and the necessity of a well-structured disaster plan approved by the Committee, to start drafting such a plan in a professional manner. To this aim, the Committee joined forces with the EGHS and Bairnsdale Museum, and the plan now outlines when and how such an evacuation will take place, who is in charge of which part and what are the backup options, ensuring the safety of the curtain, including its safe handling and that it can be located at all times (Hocking Citation2023). Evacuation procedures will be triggered when evacuation recommendations for people are issued by local Country Fire Authorities, which shows that the curtain is very much considered as a member of the community; it will be temporarily housed in Bairnsdale Museum in a fireproof location.

Similarly, the conservation process, initiated by the committee, and supported by DELWP, followed a very participative framework, orchestrated by Heritage Victoria during several online meetings including HV, committee members, and conservators. With a common goal—conserving the curtain—and many different fields of expertise and priorities, the meetings provided the structure needed to develop a treatment and maintenance proposal that included active participation from all contributors.

Since the outset, we had realised that the conservation of the curtain required more than our expertise as paintings conservators. The hanging system and the roll-down system with pulleys needed either repair or replacing, and modifications were also required as preventive conservation measures to better support the curtain when unrolled, all things beyond our expertise. Given the dimensions of the curtain (4.3 × 2.6 before conservation) it was also felt that it would be easier to work on site. We took some inspiration from the work of the American association ‘Curtain without borders’ in Vermont, USA, (Curtains without borders Citation2023) who requests in-kind help from local towns and volunteers and appeals for local volunteer expertise, as well as help with material logistics—enough tables of equal height to form an island on which we could unroll the curtain, enough blankets for padding this island, lamps and tools, and volunteers to help dismounting and remounting. While the Committee may have thought initially that the entire treatment including repairing the hanging system was to be done by the conservators, it fully embraced its role in the process of developing treatment.

Pooling expertise and negotiating values

Community participation in a shared capacity is often difficult to realise in conservation processes. Marçal and Fekrsanati note that ‘when conservation is considered a material-bound operation, communities providing meaning to the objects being conserved tend to be absent’ (Fekrsanati & Marçal Citation2022, p. 130). Henderson and Nakamoto (Citation2016) further argue that community members are often excluded from micro and macro decisions that directly affect their relation to the cultural object, such as the level of cleaning, the extent and type of in-painting or the general presentation of the conserved work.

Marçal and Fekrsanati draw on American philosopher Nancy Fraser’s notion of parity of participation, defined as ‘a social arrangement that permits all adult members of society to interact as peers’ and argue that it is especially relevant for decision making in conservation, where community engagement and collaboration are regularly advocated but where a lot of existing practices in effect consolidate existing knowledge systems and related power relationships. Social sciences, ethnography and oral history in particular, can also enlighten us on the notions of reciprocity and accountability and how conservation professionals, artists and communities can benefit from shared and respectful practice (Layman Citation2010, Newing Citation2011, Stigter Citation2016, Cotte, Tse & Inglis Citation2016).

In the case of the Bullumwaal curtain, the need for conservation was agreed upon in principle by all participants. The community had long identified that its physical condition precluded regular use; the conservators’ Preservation Needs Assessment highlighted the structural and surface issues, and DELWP described it as ‘a very rare and significant survivor of a tradition of painted Mechanics Institute Curtains which is evocative of a specific time and place and warrants preservation’ (Heritage Victoria Citation2021).

However, the essential questions on why do we conserve, for whom and how, and who does what, required discussion and negotiated agreement. The cultural value of the curtain was recognised but is still a contested field, since at the present time the curtain is not included on the Victorian Heritage Register. The request of inclusion is in progress, piloted by EGHS. Although there is a significant backlog of demands due to an explosion of requests during the pandemic, which considerably slows the process, the discussions between EGHS and HV show that the registration is not certain, because it is unclear that this curtain is of interest to all of Victoria, and that public access is not guaranteed (Hocking Citation2023). The Bullumwaal Mechanics Hall Stage Curtain Audit Sheet (Heritage Victoria Citation2021) mentions ‘Comparative analysis of Bullumwaal Curtain with other stage curtains in the state and in the context of a folk-art or vernacular tradition will help to determine whether the curtain is of State-level significance’. It does recognise however that ‘heritage recognition would deliver positive emotional benefits for the community who are already very proud of the curtain and may increase tourist visitation to the area. It would also increase the ability of the committee to attract funding for the curtain’. This illustrates well how cultural heritage objects embody a group’s self-knowledge and cultural continuity, while also being resources for outreach activities and developments that foster an enhanced cultural identity (Salomon & Peters Citation2009).

Providing funding directly to the Committee effectively placed them in a position of power in the decision-making process. The meetings, moderated by Heritage Victoria, adopted a different governance model, setting the expertise, requests and tasks of the different participants equally, according to their skills and their role. Each group then devised their proposal according to the other groups’ requests, although some of them were not pursued, such as the suggestion by Heritage Victoria to have a storage box custom-made, satisfying criteria of safety, portability, protection from fire, theft and climate regulation. The committee decided against this method of storage for the time being, acknowledging nevertheless that the topic was worth discussing and would have been otherwise overlooked; it may be the topic of other grant applications in the future (Fleischer Citation2023).

Changing the hanging system

The Bullumwaal committee held several meetings to discuss the hanging system and reported their decision not to repair the existing one, but to devise a new one, more secure, easier to implement and most importantly much easier to dismount in the event of an evacuation. Tapping on the local members’ extensive network of skills and relationships, notably in the local trailer manufacturing company, Kennedy Trailers, it involved replacement of existing parts (wooden batten, pulley) with a modern aluminium batten and wing nuts, which allows dismounting the curtain from the ceiling in a few minutes. The system includes two steel rings attached to the hall’s ceiling joist to support the rod when the curtain is rolled; the rings are attached with hinges to allow unrolling and quick dismounting. Finally, other rings are attached to the stage (with hinges to allow folding when not in use) to support the curtain lower rod when unrolled. This accommodated the conservators’ recommendation to support the heavy curtain rod to avoid tearing of the fabric, and was further modified to include a covering veil protecting the curtain from light when unrolled and from abrasions in the process of rolling .

Relining of the curtain

The conservators shifted their initial proposal of minimal structural intervention to full relining, in order to accommodate for the community’s desire of regular unrolling for use. This meant extensive research for a suitable material and technique fitting the requirements of durability, flexibility, aesthetic and possibility of working on site. Toxicity, feasibility and availability of materials were also important criteria; for example, it was not feasible outside a conservation lab to maintain a 12 m2 painted piece of heavy cotton in tension on a frame for cold lining; similarly, solvent-based relining techniques had to be ruled out as there are no ventilation features in the hall. The drying times were also a factor, since the time frame was limited; weight after relining was another factor. We eventually settled for a relatively light weight linen canvas, fortunately woven in 310 cm width, that allowed lining without seams. The lining was done with a synthetic resin (Beva® 371 film, reactivated with heat using simple irons). After relining, the surface was dry cleaned with brushes and locally with scalpel blades (on stains). The abrasions and small losses were toned down using diluted acrylic paints, allowing much better reading of the vignettes.

Sequencing the interventions

The Committee’s decision to change the hanging system was accepted by all, in view of its benefits and versatility, as was the conservators’ suggestion of a covering veil, an addition to the original elements. Its realisation was shared between the conservation team (providing the material—spunbonded polyethylene Tyvek—and the specifications/dimensions, which depended on uncovering the top of the composition) and Jacque Hocking from EGHS (doing the sewing within a few days). Given that certain actions could only happen when some other actions were completed (rod being prepared so the curtain could be reattached to it; veil dimension known when top batten was dismounted and top edge unfolded; veil to be sewn so it could be sandwiched in the top batten system), and that the conservators’ presence was limited in time, all actors in the conservation process needed to work within a short timeframe to allow the others to proceed. The calendar of intervention was established tightly, so we could rehang the curtain and its veil on the day before last (see and ), in order to assess the overall aspect and refine in-painting and glazing accordingly (see and ). Everyone respected their commitment, giving extra hours after work to pick up and clean the curtain rod, sewing the veil, fabricating and testing the hanging system. Less urgent elements (covering sleeve for the rolled curtain, supports attached to the stage) were completed at a later time.

Figure 4. Peter van Diesen, Sabine Cotte, Nadine Fleischer, Phil Large and Kevin Fleischer installing the hanging system, image S Vardy

Figure 5. Peter van Diesen, Phil Large and Kevin Fleischer unrolling the curtain protected by its veil. Note the upper rings pivoted to the sides to allow unrolling, image S Cotte.

Table 1. Timeline of the Bullumwaal curtain conservation project.

Table 2. Timeline of the treatment with the tasks of each participant outlined in different colours.

Importance of volunteers

The role of the community’s volunteers in the whole process cannot be underestimated; Bullumwaal’s residents, most of them not part of the Hall Committee, provided essential parts of the work (devising, fabricating and installing the hanging system; fabricating and installing additional elements for prevention of damage) according to their skills (including in project management), and coordinated the process. This was probably easier because the community is so small (Fleischer Citation2023) but involved more time given by each volunteer, which arguably enhanced their agency and ownership of the conservation process, as well as reinforced community cohesion.

Clavir (Citation2020) reflects that the social dimension of conservation is still part of the practice of a minority of conservators, which is particularly true for collections hosted in institutions. Being outside the institutions, although previously detrimental to this community for their fundraising efforts, proved in the end an advantage for the curtain conservation project as it facilitated an inclusive process of decision-making. Essential questions of authority, legitimacy and expertise were solved by not questioning each other’s expertise, but by asserting points deemed important to each party, the rationale behind them and how best it would benefit the object and the community at large.

Decision sharing during treatment

Sharing decisions happened before treatment, but also during the process of conservation itself, continuously negotiating values and considering the outcomes of minor decisions that have a big visual impact on the final appearance of the curtain, such as leaving the lining fabric visible on both sides, or the colour of cotton ribbon covering the staples along the lower rod. These decisions, apparently small, add up with other decisions such as the new hanging system and eventually change the material integrity of the curtain; this was nevertheless considered as being ethical practice, since it integrated the use value of the curtain, gave visibility to the long sought-after conservation treatment and therefore added another layer to the curtain’s life story within the Bullumwaal community.

The success of the project is largely due to the positive attitude of the participants ‘working as a team for problem solving’ (Fleischer Citation2023) and the skilful moderation of Heritage Victoria. The conservators exerted some influence on decision-making by sharing their goals and suggesting achievable changes in the hall set up and the curtain’s presentation (curtains on windows, door’s automatic closing system, protective veil and hooks for supporting the wooden rod); as they could see benefit from their perspective, these changes were accepted and technically solved by the committee, using their own skills and networks in devising the hanging system and planning improvements to the hall. Similarly, our initial objective for minimal intervention that seemed to better fit our conservation ethics was modified to accommodate the committee’s goal to use the curtain more often, adjusting our practice to the community’s desired outcome; this time the technical problems were ours.

The conservators recognised the committee’s authority in the final appearance of the curtain: once it was hung, we worked for the last day with committee members who provided input about visually enhancing some parts that were still not legible enough for them, until the result met their expectations. As Nadine Fleischer puts it, ‘we wanted it to look a little bit nicer, have it stable, but not looking brand new, keeping the integrity of what it is now’ (Fleischer Citation2023).

This shared decision-making allowed us to achieve a negotiated outcome that respected both community values and our ethics of preservation, while ensuring that future care by the community is possible .

Accountability and reciprocity throughout the project

Notions of accountability and reciprocity are important for an effective collaboration. The conservation process took place in a ‘collaboration zone’ that ‘provided opportunities for potent interactions’ (Lewincamp & Sloggett Citation2016). For example, prior to treatment, the conservators had to itemise and justify their quote on several occasions, mainly because of the committee’s concern in case of unexpected difficulty during treatment. The committee required a plan B, (hiring more people after the first week, to fit in the overall time frame), to ensure that the community would not be left with an unfinished curtain once the budget had dried up. This effectively shifted focus from the authorised expert discourse to a community council management’s discourse, and arguably honed all participants’ communication skills. As conservators, adopting a reflexive practice helped us to better integrate social dialogue into our professional experience, and to better understand issues surrounding the preservation of living heritage and the variety of values embodied by the cultural objects, which we had already experienced in different settings (Cotte Citation2013, Citation2011).

Reciprocity meant giving back to the community not only by delivering conservation work but also by communicating this work to the broader local community. The conservation talk in the hall was very well attended and well received, with some previous committee members extremely moved to see their curtain finally receiving the care it deserved. For us it was a very rewarding moment, showing the social value of conservation and how it can ‘provide a vital means of community-building by reinforcing shared histories, cultivating collective identities and fostering a sense of place’ (Avrami Citation2009, p 180).

A good two-ways exchange goes both ways, and once the treatment was advanced enough to spare two hours, we were honoured to receive a special tour of gold mining history in Bullumwaal by Phil Large, including the cemetery and miners’ houses remains in the bush, as well as a (bat–infested) disused goldmine, which gave us a much better idea of the township’s life at the time of the curtain’s creation. Moreover, at the end of the treatment, the committee requested that we signed our names on the curtain, an ethical dilemma for us. However, since it was the community’s wish to add this memory to the curtain, contributing to its biography, a compromise was found; the names and dates were engraved on the new top rings by a skilled community member.

Conclusion

Since treatment completion, the curtain generates a lot of interest (1500–2000 views) in Gippsland through the Facebook page of EGHS (Hocking Citation2023). An Open Day was held to celebrate it in March 2023, in order to publicise its presence and attract people from the region to the township. It included a display and photographs, as well as a Miners and Prospectors display, and the conservators’ talk about the treatment. The local state member was present, adding significance and some gravitas to the event. A particularly moving moment was when the grand- and great-grandchildren of W Minters Blacksmith, who had travelled from a distance for the Open Day, shared their pleasure to be able to read the panel (previously illegible) depicting their family’s business, and proudly posed in front of it. The conservators’ talk was well received and many expressed their interest in discovering the processes and skills involved in conservation treatments.

In the year since the treatment completion, some extra research by East Gippsland Family History Group Inc. and the East Gippsland Historical Society Inc., both members of HNEG, uncovered a lot of information on the artist (hitherto unknown) and many of the families running the businesses advertised on the curtain. As another example of two-ways exchange of knowledge, the research was published in a special issue of the groups’ newsletterFootnote4 for which the conservators contributed an extensive article relating the treatment of the curtain.

The new historical research notably sheds light on the itinerant nature of life at the time, many of these families having left Bullumwaal when the gold mines were closed and only few descendants still living in the region. This new knowledge, triggered by the conservation process, opens the Bullumwaal community to new connections with other parts of Victoria where these families have moved and created other businesses. For us as conservators, it perfectly illustrates how the value of cultural heritage resides in its ability to create new connections between people, and that preserving objects means essentially preserving this possibility of new life experiences (Henderson Citation2020). Each generation in Bullumwaal adding something to the curtain (material, such as the new hanging system, or immaterial such as new knowledge) perfectly defines it as living heritage linked to the place.

Future events are discussed, with other groups to come and have a tour of the town’s gold mining history. Because all committees and historic associations are run by volunteers, it takes time to organise events and make new contacts; however, the curtain’s stable condition and renewed legibility now allows for more access and planning of such visits. The Heritage Victoria registration application will also resume in 2023, trying to address the problems inherent with a small community in order to provide public access to the classified heritage, and expanding research to prove the curtain’s relevance to the whole of Victoria, one of the criteria for registration (Hocking Citation2023).

As we observed the cycle of events, starting from the community seeking conservation, the conservation process creating new knowledge, strengthening connections and delivering emotional well-being for the extended community, and the community building up on this to expand knowledge and experiences around the curtain, we were reminded of the meaning of our work, how ‘transformation comes from transforming and being transformed through conservation processes’ (Peters et al. Citation2020) and how conservation contributes to social sustainability by ‘building community and enhance social cohesions’ (Avrami Citation2009).

During her discussion with us for the writing of this paper, Nadine Fleischer reflected that ‘we worked together very well as a team, it was good to learn from you guys and good to see that you could learn some new things as well’ (Fleischer Citation2023). As the story of the curtain continues in the present, we acknowledge the privilege of being able to work together on this important object, forming relationships and seeing the multiple connections between the people and their past develop into the future, which in essence is the very purpose of conservation.

Materials

Beva® 371 film, (Berger Ethylene Vinyl Acetate), FILBEVA2-27, 685 mm × 6 m, Archival Survival, www.archivalsurvival.com.au

Libeco 804 Loom-State Linen (310 cm wide), Chapman & Bailey, https://chapmanbailey.com.au/art-materials/

DuPont™Tyvek®, FILTY 43-5, 1524mm × 5m, 43gsm, Archival Survival, www.archivalsurvival.com.au

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Bullumwaal community, particularly Kevin Fleischer, Di Fleischer, Phil Large, Peter van Diesen; Helen Kiddell, Jo Lyngcoln and Jenny Dickens (HV- DTP); Tracey West (DEECA); Debbie Squires (EGFHG) and all volunteers, for their work in preserving the curtain and researching its history for the local community.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sabine Cotte

Sabine Cotte holds conservation degrees from France, Italy and Australia. She has worked in the Himalayas for UNESCO, ICCROM and private NGOs, training local people in conservation and disaster recovery. She is an Honorary Fellow of the Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation, and a tutor in the Masters of Curatorship, University of Melbourne. Her book Mirka Mora, a life making art was published by Thames and Hudson Australia, in 2019.

Nadine Fleischer

Nadine Fleischer is a Bullumwaal resident and the treasurer of the Bullumwaal Mechanics Hall Committee of Management, Bullumwaal, Victoria. She has been instrumental in the fundraising efforts to conserve the stage curtain.

Jacqueline Hocking

Jacqueline Hocking is a local historian based in Bainsdale (East Gippsland), 30 km from Bullumwaal. She is the secretary of the East Gippsland Historical Society. She is currently writing a book about the history of Bullumwaal.

Sherryn Vardy

Sherryn Vardy holds visual arts degrees from Monash University and a Master of Cultural Material Conservation from the University of Melbourne. With over 25 years' experience in the museum industry, she has held roles at regional galleries, National Exhibitions Touring Support (NETS) Victoria, Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) and Australian Museums and Galleries Association (AMaGA) Victoria. Sherryn currently operates a private conservation practice in Gippsland, Victoria.

Notes

1 CHG is funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts; National Library of Australia; the National Archives of Australia; the National Film and Sound Archive and the National Museum of Australia.

2 As per 1 January 2023, DELWP is the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA). Heritage Victoria is now part of the Department of Transport and Planning (DTP).

3 The East Gippsland Heritage Gaps Study was prepared in 2005 by Context Pty Ltd for East Gippsland Shire Council.

4 Black Sheep, February 2023, newsletter of East Gippsland Family History Group Inc. and the East Gippsland Historical Society Inc., accessible for subscribers. https://www.egfhg.org.au/blacksheep.htm

References

- Curtains without borders 2023, viewed 16 February 2023, https://www.curtainswithoutborders.org/

- Victorian Places 2015, a project by Monash University and the University of Queensland, viewed 15 February 2023, < https://www.victorianplaces.com.au/bullumwaal>.

- Avrami, E 2009, ‘Heritage, values and sustainability’ in A Richmond & A Bracker (eds), Conservation: principles, dilemmas and uncomfortable truths, Elsevier, London, pp. 177–183.

- Bentshop, R, Rausch, C, Van Saaze, V & Sitzia, E 2022, ‘Introduction’ in R Bentshop, C Rausch, V Van Saaze & E Sitzia (eds), Participatory practices in art and cultural heritage, learning through and from collaboration, Springer, Cham (CH), pp. 3–10.

- Clavir, M 2020, ‘Conservation and collaboration: a discussion’ in R Peters, ILF den Boer, JS Johnson, S Pancaldo (eds), Heritage conservation and social engagement, UCL Press, London, pp. 30–46.

- Cotte S 2011, ‘Conservation of thangkas: a review of the literature since the 1970s’, in Studies in Conservation, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 1–13.

- Cotte S 2013, ‘Reflections around the conservation of sacred thangkas’, in Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–12.

- Cotte S, Inglis A & Tse N 2016, ‘Artists’ interviews and their use in conservation: reflections on issues and practice’, in AICCM Bulletin, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 107–118.

- Fekrsanati, F & Marçal, H 2022, ‘Affirming change in participatory practices of cultural conservation’ in R Bentshop, C Rausch, V Van Saaze & E Sitzia (eds), Participatory practices in art and cultural heritage, learning through and from collaboration, Springer, Cham (CH), pp. 127–140.

- Fleischer, N 2023, Nadine Fleischer interviewed by authors, 7 February 2023.

- Henderson J 2020, ‘Beyond lifetimes: who do we exclude when we keep things for the future?’ Journal of the Institute of Conservation, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 195–212.

- Henderson J & Nakamoto T 2016, ‘Dialogue in conservation decision-making’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 61, no. sup. 2, pp. 67–78.

- Heritage Victoria 2021, Bullumwaal mechanics institute stage curtain, Bushfire Recovery audit sheet 29 April 2021, unpublished.

- Historic Places, n.d., Bullumwaal Hall record card, unpublished.

- Hocking, J 2023, Jacqueline Hocking interviewed by authors 2 February 2023.

- Johnson J, Heald S, McHugh K, Brown E & Kaminitz M 2005, ‘The practical aspects of consultation with communities’, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 203–215.

- Layman L 2010, ‘Ethical imperatives in oral history practice’, Studies in Western Australian History, vol. 26, pp. 130–150.

- Lewincamp S & Sloggett R 2016, ‘Connecting objects, communities and cultural knowledge’, AICCM Bulletin, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 3–13.

- Newing H 2011, Conducting research in conservation, a social science perspective, Routledge, London.

- Peters, R, den Boer, I, Johnson, J & Pancaldo, S (eds.) 2020, Heritage conservation and social engagement, UCL Press, London.

- Salomon, F & Peters, R 2009, ‘Governance and conservation of the Rapaz Khipu patrimony’ in H Silverman and D Fairchild Ruggles (eds), Intangible heritage embodied, Springer Verlag, Frankfur/New York, pp. 101–125.

- Scott M & O’Connell J 2020, ‘Sustainable conservation: linking conservation students and graduates with local communities to build a sustainable skills-based heritage preservation model in rural and regional Australia’, AICCM Bulletin, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 27–34.

- Sloggett R & Middleton J 2018, ‘‘For mutual benefit: cultural materials conservation and local government-a case study’, AICCM Bulletin, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 65–73.

- Smith, L 2006, The uses of heritage, Routledge, Abingdon and New York.

- Smith, C.A & Ngarimu, R 2021, ‘Artefact access: the gulf between theory and practice’, In TTranscending Boundaries: Integrated Approaches to Conservation, ICOM-CC 19th Triennial Conference preprints, Beijing 17-21 May 2021, J. Bridgland (Ed.), Paris, International Council of Museums.

- Stigter S 2016, ‘Auto-ethnography as a new approach in conservation’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 61, no. sup. 2, pp. 227–232.

- Sully D (ed.) 2007, Decolonizing conservation: caring for Maori meeting houses outside New Zealand, University College London Institute of Archaeology Publications and Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

- Waterton E & Smith L 2010, ‘The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, vol. 16, pp. 4–15.