Abstract

This paper develops an understanding of the complex interplay of perspectives implicit in the multifaceted practice of Cultural Materials Conservation, as it pertains to individuals, larger organisational structures, and contemporary social contexts. The research takes the form of a six-week online qualitative group interview, which captures a range of opinions and attitudes from a cross-sectional group of conservation practitioners. The data is presented as a complete de-anonymised interview transcript, available as a supplementary material, which describes the experiences and perspectives of individual practitioners, their day-to-day challenges, and the decision-making processes conservators face in their practice. A central argument in this paper is the value of the concepts of humanness and reflexivity in twenty-first-century conservation thinking. Reflecting on the role of individual practitioners as custodians of cultural heritage, with the view on what it means to be a conservator in practice today, is a valuable contribution that can shed light on the conservation decision-making and evolving practice that is focused on sensitivity and fluid responsiveness to cultural changes, personal values, and diverse relationships involved in the conservation of cultural heritage.

Introduction

Conservation practitioners perform a wide array of activities focused on preserving, safeguarding, and activating cultural heritage objects, through which they encounter various ethical and practical challenges, while undertaking and documenting interventions on cultural heritage objects. These activities are performed for numerous reasons, and for a variety of stakeholders, often ‘balancing the interests of diverse actors with uncertain trade-offs between multiple priorities’ (Pienkowski et al. Citation2023, p. 3). Conservation practitioners have historically argued that their decision-making processes are impartial, objective and self-contained, driven by the material needs of the objects they work on, rather than ‘for reasons which are derived from a subject’s views or preferences’ (Muñoz Viñas Citation2005, p. 27). This approach undervalues the significant role that conservators, whether in or outside of the museum, play as active participants in the complex networks of agency that contribute to the enhancement of cultural heritage. According to Byrne et al.:

The museum, the people who staff and run them, the objects and the various individuals and processes which led to them being there, those who visit them and those who encounter the objects within them in various media are all a part of networks of agency. (Byrne et al. Citation2011, p. 4)

This paper presents qualitative research demonstrating that the day-to-day experience of performing conservation is anything but neutral; it is often subjective, relational and at times bound within the emotional experiences of the practitioner. The research, undertaken in the form of semi-structured interviews with six conservation professionals, is presented as a complete transcript to accompany the online article as supplementary material (Sherring et al. Citation2023) Case studies and examples discussed therein illustrate that individual perspectives, values, institutional priorities, and the lived experiences of conservators contribute to decision-making and addresses the assumption of neutrality in conservation decision making (Pearlstein Citation2017, p. 435). The themes addressed in the paper were wholly formed in response to the undulation and progression of concepts that emerged during the interviews. The availability of the complete transcript also offers a perspective for recognising the significance of personal reflection in conservation practice.

By examining the research findings, the author highlights an opening for conservators to embrace their responsibilities as custodians of cultural heritage with humility, openness, and a heightened awareness of the positive influence they can exert as active participants within networks of cultural agency. This paper presents an opportunity to reflect on our role as custodians of cultural heritage through a practice-based lens that views conservation as an act of living, where ‘to live, every being must put out a line, and in life these lines tangle with one another’ (Ingold Citation2015, p. 2).

Positioning subjective judgement in conservation practice

Historically, conservators have been reluctant to acknowledge their active role in determining the trajectory and ongoing significance of cultural material heritage (Wain & Sherring Citation2020). Reflecting the scientific origins of the discipline, ‘subjective experiences and emotions have been overlooked in the practice of scientific research’ (Groth Citation2015, p. 1), as they have been thought to interfere with expert or objective logic (Damasio Citation1999, p. 39). While the field of conservation has moved increasingly towards a more holistic and inclusive approach that considers the current global socio-ecological context in relation to practice, the role of the conservator is presented as that of the impartial scientist (Harman Citation2016) or during times of crisis, the ‘emergency responder’ (Smith Citation2020, p. 424–425). Both identities are reactive rather than proactive and do not accurately reflect the expertise, experience, and personal values that conservators bring to their work, shaping the choices they make.

Moreover, the evolving landscape of the twenty-first century has brought forth new challenges for cultural heritage professionals to adapt to changing social, environmental, political, and technological contexts. These societal shifts are seen in the industry’s guiding documentation, for example in the AICCM Strategic Plan 2020–2025, which acknowledges that ‘culture is inextricably linked to human identity and identify where unconscious assumptions and bias affect our practice’ (Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Material Citation2020). This statement challenges the discipline’s historic frame of reference that maintains that conservation is a practice based on scientific principles and empirical evidence with ‘the emphasis on the material [having] a profound effect on the shaping of conservation’ (Pye & Sully Citation2007, p. 19) and highlights the importance of self-awareness and ongoing reflection in addressing the subjective aspects of decision-making in conservation. With the shift away from the myth of materially objective decision-making, the values of conservators begin to find a place in discipline ideology. In truth, conservators have their own set of values and ethical considerations that influence their decision-making process. These values can be shaped by their professional training, cultural background, underlying belief systems, as well as professional and personal experiences. These values can introduce a subjective aspect that both consciously and unconsciously influence decisions made in the workplace about the level of intervention, the choice of materials and techniques, the desired outcome of the conservation treatment and the potential broader effects on society and creator communities.

Self-reflection in academic literature on conservation

In academic and research contexts, some scholars have been leading a shift towards the inclusion of self-reflection within conservation values and philosophical approaches (Muñoz Viñaz Citation2005; Clavir Citation1998; Smith Citation2006; Richmond & Braker Citation2009; Wain Citation2011; Scott Citation2015). These contributions include proposing alternative frameworks to ethical codes of practice (Ashley-Smith Citation2017; Wharton Citation2018; Sweetnam & Henderson Citation2022; Van de Vall Citation2009; Wain & Sherring Citation2020) and examples of conservation approaches that demand more people-centred practices (Clavir Citation2002; Wharton Citation2008; Sloggett Citation2009; Henderson & Nakamoto Citation2016; Bloomfield Citation2023; Owczarek Citation2023). Fekrsanati and Marçal attribute the predominance of ‘collaboration within the framework of social and cultural’ (Fekrsanati & Marçal Citation2022, p. 129) activities to occur in the fields surrounding the conservation of objects from indigenous cultures and contemporary art, stating that:

Both Fields acknowledge conservation’s role in shaping objects and their stories and conservators’ role as co-producers of those objects and their materialities [sic]. (Fekrsanati & Marçal Citation2022, p. 129)

A small fragment of the literature directly focuses on the need to apply self-reflection in conservation practice, including contributions that evaluate a conservator’s own perspectives and decision-making in relation to cognitive psychology (Marçal, Macedo & Pereira Citation2014), taste and subjective decision-making (Wei Citation2022). Equally, Jonathan Ashley-Smith (Citation2000) and Jane Henderson (Citation2018) recognise that dealing with uncertainty in their daily practice poses a significant challenge for many conservation professionals.

In recent times, conservation scholars have highlighted the significance of subjectivity as a vital element in research by turning to social science for qualitative research methodologies including affirmative ethics (Marcal & Gordon Citation2023), and autoethnography (Stigter Citation2016, Henderson, Lingle & Parkes Citation2023), where ‘personal experience (auto) is used as a lens to describe and systematically analyse (graphy) understanding of cultural experience (ethno)’ (Ellis, Adams & Bochner Citation2010, p. 1), but also promote positive actions and values in ethical decision-making that focuses on the betterment of individuals and society. These approaches, commonly termed as reflexivity (Finlay Citation2002) involve the capacity to examine one’s own emotions, responses, and motivations, and comprehending how they shape one's actions or thoughts in a given situation. Reflexivity involves more than merely being self-aware of one's performance; it entails a thorough examination of our own perceptions and ‘make them more widely available for scrutiny’ (Henderson, Lingle & Parkes Citation2023, p. 2).

Towards subjectivity in conservation practice

Subjectivity plays a vital role in the decision-making process, as conservators rely on their expertise, experience, and personal values to make choices that uphold the ethical principles of conservation while considering the diverse perspectives of stakeholders. A lack of impartiality or neutrality is often viewed unfavourably in scholarly conservation publications, self-awareness and honest critical reflection is a daily requirement of the practicing conservator, who must constantly consider ‘how the object affects their actions while at the same time considering how their actions affect the object’ (Stigter Citation2016, p. 227). Ethical considerations and decision-making are essential components of the conservation field, where the expertise and personal values of the conservator contribute to subjective judgments in determining when and how to intervene in the conservation process (Henderson & Nakamoto Citation2016). As noted by Laurajane Smith:

Heritage management, conservation, preservation and restoration are not just objective technical procedures, they are themselves part of the subjective heritage performance in which meaning is re/created and maintained. (Smith Citation2006, p. 88)

Humanising conservation: language for a most human practice

Professional and academic recognition of how personal beliefs, biases and sociocultural perspectives influence conservation practice invites us to consider how this awareness can lead to more thoughtful and ethical decision-making. Since all values are inherently human, it is proposed that humanness, an intentionally fraught term, may be used to guide richer understandings of the complexities of conservation decision-making. The concept of the word humanness, as it is used in this paper, acknowledges multi-faceted attributes and behaviours that make up an understanding of what it means to be human (Taylor Citation1989), including an understanding of how human actions impact both sentient and non-sentient things (Haraway Citation2008), materials and the environment (Ingold Citation2015).

‘Humanness’ relates to the conservator by virtue of their existence as a sentient being with individual perspectives, values, subjectivities and lived experience, while also professionally engaging in acts which shape the cultural and social significance that other entities attribute to cultural heritage. This is itself intrinsically linked with, and made meaningful by, their humanity. Humanness is not proposed as a normative value for conservators, rather in the tradition of thinkers such as Haraway, the term is offered as a prompt to ‘stay with the trouble’ (Haraway Citation2016, p. 1) of what it means to practise with more-than-human networks of organic and synthetic materials, as well as diverse communities and stakeholders. As Haraway explains:

Staying with the trouble does not require such a relationship to times called the future. In fact, staying with the trouble requires learning to be truly present, not as a vanishing pivot between awful or Edenic [sic] pasts and apocalyptic or salvific futures, but as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings. (Haraway Citation2016, p. 1)

Methodology

In addition to offering original reflections on the question of humanness for contemporary conservators, this paper presents a networked research methodology that aims to integrate multiple agentic human perspectives across layered media platform encounters. Qualitative insights were gleaned through reflective thematic analysis of the data collected, which does not seek to offer a single definitive interpretation of the material. Rather, it seeks to present one story, among other possible stories that may be told from a collectively authored transcript (Braun & Clarke Citation2006; Sherring et al. Citation2023). In doing so, the paper provides a model for how the complex interplay of perspectives in conservation practice need not be minimised but recognised as an integral part of our professional roles.

Roundtable interview as research

In celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the professional organisation for conservators in Australia, The Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material (AICCM), the AICCM Bulletin Editorial Committee sought contributions for a special volume of the journal exploring topics related to self, systems and society (Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Material Citation2022). Rather than explore each of these concepts as a discrete entity, this research sought to understand the interdependent relationship between the notions of each theme and their mutual influence over one another, traversing the interconnectedness and relationality of conservation practice.

This qualitative primary research was developed through a semi-structured, in-depth focus group interview (roundtable), conducted online over eight weeks with six online participants. It aimed to capture a range of opinions and attitudes from a cross-sectional group of conservation practitioners on topics that relate to the practice of conservation today, such as the International Council of Museums (ICOM) New Definition of ‘Museum’ (International Council of Museums Citation2022), the continued relevance of ethical codes of practice, conservation education and training, community and stakeholder engagement and the future of the profession in Australia. The author employed a qualitative research methodological approach, which supports the generation of new form of knowledge through social practice (Denzin & Lincoln Citation2017). This method demonstrates that:

an interview is a meeting that combines methodological features with the attitudes of involved people … and utilises communication habits and experiences from both sides of the conservation—the interviewer and interviewee. (Latkowski Citation2021, p. 202)

Participants

This research method was deployed to collect differentiated data, while establishing criteria to ensure that diverse interviewee representation. Participants were selected based on some of the following parameters:

Participants have a connection with the Australian conservation sector through either education and/or professional experience.

Participants represented a diverse range of material specialisations.

Each participant has gained experience in broader cultural sector roles, outside of conservation.

Participants are at emerging, mid-career or established career stages.

Participants obtained educational qualifications at different programs.

Participants have taught into different conservation programs.

Participants are living/working in different geographical locations.

Participants included conservation professionals Melanie Barrett, Heather Bleechmore, Tharron Bloomfield, Carolyn McLennan, Chris Redman and Michelle Stoddart. Ethics approval was obtained from all participants, along with express permission from participants to de-anonymise data and publish the full interview transcript as supplementary material in view of providing a richer understanding of the research participants’ perspectives, experiences, and voices. Moreover, it aids in illustrating how an awareness of one's own subjective perspectives, biases, and values can be viewed as a core component of the practice of conservation. Providing access to the complete transcript allows readers to gain insights into the nuances, emotions, and subtleties that may not be fully captured in a summary or analysis of the primary research.

Interview format

The interview questions were provided to the participants one week in advance via email to allow for time to consider and reflect on the topics being discussed. The interview was conducted by interviewer, Asti Sherring and moderator Isabelle Waters, who provided general time keeping and prompts to participants, as a roundtable discussion via Zoom video conferencing application on 4 September 2022 at 5:30 pm Australian Eastern Standard Time. The interview was recorded on the land of the traditional custodians, Dharawal People in New South Wales. The initial zoom interview ran for 1.5 h across geographical locations, including Aotearoa New Zealand, Singapore, Australia and the United Kingdom. The interview was audio recorded and transcribed in Otter.ai application. The discussion was copy edited by the interviewer, moderator and participants to enable better clarity and flow in written form, and reviewed by participants for accuracy and completeness to ensure that the final transcript captured the participants intentions (Sherring et al. Citation2023).

The original intention for the capture and dissemination of this research was to reflect a democratic process that respected the perspectives, personal expression, and time of all participants, including the interviewer (Johnston Citation2006). The qualitative research methodology of researcher as participant was applied to the interviewer to allow for the roles of practitioner and researcher to merge (Phillips & Zavros Citation2012; Balsiger & Lambelet Citation2014). As a participant researcher, the interviewer collected data through handwritten notes that documented comments, quotes, examples, and questions during the interview.

Following the initial synchronous roundtable meeting, these notes formed a basis for development of further interview questions and prompts that were disseminated to participants via a shared cloud-based document, which could be edited by any of the participants. Alongside these notes, the initial conversation transcript was uploaded as a shared Google document, creating a common editorial space where participants could expand upon thoughts, add examples, and carry on conversations. The interviewer, moderators and participants all had opportunities to remove and add material utilising the process of interviewee transcript review (ITR), ‘as a form of respondent validation’ (Rowlands Citation2021, p. 1), enabling collective agency and participant confidence in the process. All participants reviewed, edited and approved the transcript prior to publication.

As a participant researcher, the interviewer took responsibility for final copy-edits of the interview transcript, including minor grammatical changes and the addition of sub-headings. The pursuant discussion in this paper above on reflexivity and humanness, is solely the work of the author, who is responsible for the introduction, conclusions and further analysis of the final transcript and topics discussed in the paper.

Identifying humanness in the interview transcript

In reading the full interview transcript, a theme which is consistently evident is that conservation decision-making is an inherently human process, drawing deeply on personal views and experiences. In following the flow of dialogue, it can be seen that conservators are influenced by dialogue with other conservators, conversations which are informed, but not led by the corpus of literature and ethical codes such as Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Material, ‘Code of ethics and code of practice’ (Citation2002). This provides a narrative to the positioning of historic conservation literature, which tends to depict the conservator as an impartial, objective science-based expert who mediates their relationships first and foremost with material objects (Clavir Citation1998, Citation2002). The organic development of ideas often found within contemporary art and indigenous cultural care conservation practice can at times be seen to be at odds with the implication of objectivity found in the traditional literature, that posits there is an ideal conservation stance—and that anything other than this could impact or harm the future of material cultural heritage (Fekrsanati & Marçal Citation2022, p. 129).

The resulting contributions show a range of perspectives on the humanness of conservation practice—that is to say, the complex embeddedness of conservator's perspectives is influenced not only by the objects themselves, but also the way that they relate to varied cultural and ecological networks and broader societal and environmental contexts. As Haroway elucidates:

It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories. (Haraway Citation2016, p. 12)

Overall, the reflections underscored the deeply personal and interconnected aspects of conservation practice where participants shared personal accounts that highlighted the importance of recognising their own human stories as integral to their value systems, which have influenced their practice. They conveyed a sense of appreciation for the human experiences, relationships, and values that shape the work of conservators and enrich the field. The contributions recognised that conservators are not merely technical experts, or dedicated stewards of cultural material heritage, but play an important role in transmitting culture.

Many of the themes discussed during the interview are not necessarily new and have been discussed formally and informally across the field for some time, such as at AICCM National Conference 2019 ‘Making Conservation’ and more recently at the IIC conference ‘Conservation and Change: Response, Adaption and Leadership’. However, the difference evident in the way these themes play out in roundtable discussion or in the published sources demonstrate that, as Bloomfield notes during the interview, the topics addressed in this paper are not just fit for ‘break room conversations’ but have a place in scholarly literature.

Evolving values and ethical codes of practice

The establishment of an Australian professional body in 1973 was influenced by practicing societies like the International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (IIC) in London (AICCM Citation2010). As a part of the legitimisation of field, the Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Material developed the industry-specific framework, ‘Code of ethics and code of practice’ in 2002 (AICCM Citation2002), which conservation practitioners in Australia are expected to abide by to maintain their individual and collective professional standing.

The risk of applying ethical frameworks is that over time they become unquestionable universal guidelines, are consequently slow to address new problems or adapt to changing times and are not always applicable to individual contexts (Gfeller Citation2017, p. 758). As explained by Stoddart during the interview, there is a level of individualism gained throughout one’s professional career and personal journey that can be applied to the interpretation and application of the codes whereby:

the Codes of Ethics are relevant to help us question our decisions; to see if we can justify our recommendations. Do I feel like I'm making a change that's not for the better? Will it impact others? Am I just keeping up my skills, rather than for the betterment of the object? The codes give us criteria to work through to inform our decision making.

The conservator’s role in Contact Zones

During the roundtable, the conservators’ active participation in spaces related to ‘collection, recollection, and display’, commonly referred to as museums, was a prominent topic of conservation (Clifford Citation1997, p. 217). The concept of the Museum as a contact zone was presented by James Clifford in his 1997 paper, Museums as Contact Zones, who applied the term from leading scholar Mary Louise Pratt. Pratt originally defined the contact zone as,

the space of colonial encounters, the space in which peoples geographically and historically separated come into contact with each other and establish ongoing relations, usually involving conditions or coercion, radical inequality and intractable conflict. (Pratt Citation1992, p. 6)

The discussion also highlighted the important voice of the conservator in the positioning of the museum as a ‘democratising inclusive, and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures’ (International Council of Museums Citation2022). Participants generally appreciated the aspirational nature of the definition, with varying levels of practical implementation. During the interview, Redman expressed that it aligns with the goals which every institution should be working towards, while interviewee Barrett argued that considering diversity and the museum’s role to serve society, the inherent political nature of the museum world might allow dominant power structures to determine ‘who is included?’.

Agency and the privilege of contact

During a discussion with the interview participants, the topic of access to material objects inevitably arises. During the interview, Redman speaks to a personal ‘conundrum’ faced by conservators to facilitate the open display of objects as a part of exhibition-related decisions, noting that the want to be seen as an ‘active participant in the exhibition process’ often conflicts with traditional tenets of conservation to keep ‘objects safe and not put them in harm's way’. Interviewee Stoddart reflects that working as a book and paper conservator has helped to foster more ‘relaxed’ notions around use and wear ‘because it's a book, people are going to read it’. For Redman, these strict ethical mandates conflict with some of the practical aspects of conservation treatment, noting that,

every time I access an audio-visual or digital object it is essentially touching it. A visitor may come in and physically touch an object which is not allowed, but as a conservator I am able to run it through a machine, which is also putting wear on the object. Of course, I do this for a purpose; to extract information off and make it this content accessible in a new form, but I am also aware that this intervention is potentially damaging the original object even more.

as a Māori conservator, I've seen a lot of handling of materials and objects by communities. And I'll be honest, sometimes it's rough as guts. So, you know, it would be dishonest for me to say that I'm like, yeah, go for it. In theory, I'm all for Indigenous cultural care, but it would be dishonest to say that as a conservator I don't find it challenging to watch it.

Accounting for time in conservation

During the discussion participants observed that all decisions made for material heritage are precariously linked to the concept of time; with the conservator’s past actions and future decisions inextricably balanced with evolving value systems and a shifting understanding of authenticity. During the interview, Barrett provided an example that required complex conservation decision making to enable the exhibition of a time-based media artwork. The decision to shorten the lifespan of the object’s physical componentry to allow for a more authentic presentation of the object is a deliberate action to create a ‘dynamic archival intersection where [the] past, present, and future interpenetrate’ (Hölling Citation2017b, p. 100) and influence each other. This choice requires new paradigms of conservation thinking and a re-valuation of what authentic representation means when considering past, present and future trajectories of cultural heritage.

Social media as a platform to promote dialogues around cultural heritage

As well as providing a platform to engage with wider societal issues and cultural moments, examples of social media were discussed, which demonstrated the potential for use as a powerful communication tool to promote dialogues around cultural heritage. The importance of social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram was highlighted, namely in calling out ICOM for its somewhat arbitrary condemnation of some uses of functional heritage objects as others were promoted. In the examples discussed, it was broadly recognised that the pop musician Lizzo’s playing of United States president James Madison’s crystal flute, dated 1813 and is part of the Library of Congress’ collection of 1,800 was broadly endorsed by the conservation community while reality TV star Kim Kardashian’s wearing of a Marilyn Monroe dress to the Met Ball in 2022 was generally snubbed.

In the Lizzo example, Carla Hayden, who is the first black, female Librarian of Congress invited Lizzo to ‘play a couple’ of flutes in Library’s collection via Twitter as seen in .

Figure 1. Screenshot of Carla Hayden X [Formally Twitter] post 24 September 2022. Image captured 23 June 2023 by Asti Sherring.

![Figure 1. Screenshot of Carla Hayden X [Formally Twitter] post 24 September 2022. Image captured 23 June 2023 by Asti Sherring.](/cms/asset/c563e740-3c40-48fb-b4f9-273f9908aded/ybac_a_2312755_f0001_oc.jpg)

In the online clip released after the performance Lizzo says the flute ‘is crystal, it's like playing out of a wine glass’ (Lizzo Citation2022). This first-person account, as well as all the documentation captured on video, audio, text and shared around the world via social media as seen in , captures the liveliness of this object in this moment and is archived in a form that adds to the Library of Congress’s material knowledge and cultural significance of this object.

Figure 2. Screenshot of Lizzobeeating Instagram page 28 September 2022. Captured 23 June 2023 by Asti Sherring.

Significantly, the top comment from Instagram user inappropraitepatti in response to Lizzo’s Instagram post in notes ‘the karmic justice of you playing a slave owners flute while thousands cheer on your amazing gifts … . Priceless’ underscores the potential positive social impact of performing historic instruments to address or confront historical injustices.

In contrast, an example that drew heavy criticism from some conservation experts and sparked an international conversation on the ethics of use was Kim Kardashian attending the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute Benefit gala in Marilyn Monroe’s iconic Jean Louis gown that she wore in 1962 to sing Happy Birthday to President John F. Kennedy ().

Figure 3. Screenshot of Los Angeles Times X [Formally Twitter] post 5 May 2022. Captured 1 December 2023 by Asti Sherring.

![Figure 3. Screenshot of Los Angeles Times X [Formally Twitter] post 5 May 2022. Captured 1 December 2023 by Asti Sherring.](/cms/asset/0e5d175a-ec25-47d1-8be4-b2301b7e6fd7/ybac_a_2312755_f0003_oc.jpg)

After the event, ICOM released a statement condemning Kardashian’s choice to wear Monroe’s dress, saying,

Historic garments should not be worn by anybody, public or private figures … As museum professionals, we strongly recommend all museums to avoid lending historic garments to be worn, as they are artefacts of the material culture of its time, and they must be kept preserved for future generations. (Abrams Citation2022, np)

In response to the above ICOM statement authored by Abrams (Citation2022), Māori curator and Director, Audience and Insights at Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Puawai Cairns claimed that this statement ignorantly overlooks the value of use and living connection with First Nations cultural heritage objects:

conservation is increasingly about becoming the bridge to enable that to happen, not the block … Good Ol’ ICOM. Only thinking of its own Eurocentric cultural bubble. Again. (Council of Australasian Museum Directors Citation2022)

we’re living in an increasingly political and polarised age and so I would argue that it is the mandate of a twenty-first century conservator to take an active role in recalibrating the balance of power … The flip side being the perceived safety in passivity no longer exists once we engage in the conversation.

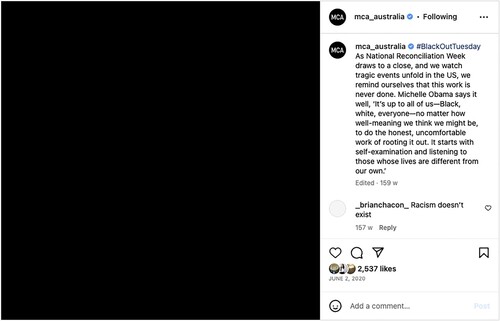

Contesting practices around First Nations cultural heritage

A strong theme present throughout the discussion is the role of conservator to actively contest and reshape existing knowledge structures around First Nations collections. Participants felt strongly that there was agency in the role of the conservator to re-negotiate past ‘asymmetrical power relationships’ (Clifford Citation1997, p. 194), which do not sit within the contemporary notions of what ‘care’ means. As stated by Bleechmore during the interview:

In Australia, we're going through a period of change … There's a lot of change politically and socially, and here in the room, we are all aware of the talks about the need to decolonise our practices as well as our collections … The role of a conservator [now] is to build bridges between artists/creators and the institution; we are often at the forefront of having those discussions about how materials are going to be handled. I think we're in a process of change; that those future bridges are being thought about and the process of navigating conversations between communities, collection, and conservation staff are being discussed and actioned.

Figure 4. Screenshot of Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney Instagram page on 2nd June 2020. Captured 23 June 2023 by Asti Sherring.

The basic right for First Nation’s people to have access to ‘one’s own material culture’ (Bloomfield Citation2023, p. 57) is still a subject of contention and debate, however participants agreed that what can be gained in relinquishing control and opening up dialogue with an object’s source community far outweighs the perceived ‘risks’ to the collection. During the interview, McLennan describes the role of the conservator in this area as one that can ‘necessitate change, with repatriation of works and the creation of space for authority and ownership by First Nations knowledge holders and elders’. As interviewee Bleechmore phrases it, ‘[conservation] is a practice that really does focus on people, community, and connection as central to preservation’.

Conclusions drawn from the roundtable discussion point to a future state of conservation practice that can align with and advocate for indigenous ways of knowing and actively participate in the disestablishment of boundaries to cultural heritage that do nothing more than perpetuate colonial narratives (Althaus Citation2020).

Looking to the future

The concluding remarks in the roundtable centred on the role of the conservator in managing cultural heritage through a period of global transformation. Some participants see the value system of the conservation practitioner as interconnected with self-identify and our ability to form relationships. Bloomfield challenges the notion that conservators are distinct from our individual communities of belonging, instead seeing conservation knowledge as being inextricably linked to our cultural values. Bleechmore suggests that the essence of conservation practice lies in its capacity to establish connections with creator communities by advocating for conservation and facilitating a mutual exchange of knowledge between industry professionals and the communities they serve. For McLennan, the experience of conservation is intimately connected to a profound comprehension of deep time and the shared histories embedded within cultural heritage objects and the communities that conservators serve.

The remaining participants raised concerns around the relevance of conservation in the twenty-first century. Barrett feels that future decision-making around cultural heritage is nothing without ‘participation and access’ to collections, highlighting the importance of the AICCM strategic vision and leadership to facilitate these important conversations across the wider sector. Redman proposes that one solution for conservation is take more of a visible presence in the Museum, signalling the need for conservation to be more inclusive with its public engagement activities. Stoddart envisions the future of conservation as one that can no longer hide behind a bench, instead engaging with policy at the highest levels and influencing development beyond cultural heritage.

What it means for a conservator to stay with the trouble

The conservation profession in Australia has been described as having ‘a tradition of thoughtful, collaborative and innovative work that has continuously sought to improve techniques, explore new developments and respond to changes in heritage and the wider world’ (Sloggett & Wain Citation2020, p. 1). In following the flow of the roundtable discussion, however, it can be seen that practitioners do not believe that the guiding documents, codes of ethics or general literature currently reflect the ontological connection between conservation practice and the global context which provides its cultural milieu.

It has been fifty years now since the AICCM was formed to help guide the conservation profession and, now that a generation of practitioners have been trained in its core philosophies, it may be time to let the conservation profession guide the AICCM. Following roundtable discussions on the state of the profession makes it clear that the ‘moments of intimacy’ which characterise the conservator-object relationship of ‘knowing the physicality of an artwork like few people do’ (Marcal & Gordon Citation2023, p. 10) is an outcome of every interaction that a conservator experiences with, and around, the cultural context which makes those objects meaningful. Conservators are experts in knowing things about the objects that they care for, but to know oneself in relation to cultural heritage involves a recognition that conservation is a practice that exists within an interconnected and complex universe.

While a humanness approach can be criticised for being utopian or overly optimistic, it strength is that it encourages us to ask critical questions about our place in the world, our relationship to those around us, and the future of the planet. A humanist value system promotes an outward-looking practice that not only ‘places more emphasis on the dynamic, complex interplay of heritage and societal values as activated by a wide variety of actors, interest groups, and institutions’ (Avrami & Mason Citation2019), but also can inspire discussions of what it means to be a conservator charged with the care of humanities cultural heritage.

By embracing our humanness, we can foster a more inclusive and responsive approach to conservation—one that honours the past while embracing the dynamic complexities of the present and future. The role of the conservator in the twenty-first century has enormous potential not only to contribute to humanity’s understanding of the past, but also to enrich its future. There is the potential to drive audience engagement through innovative community projects, to develop new employment opportunities and to advocate for more sustainable practices. There is room, also, for loftier ideas both in and outside of the museum space, to foster new relationships outside of the cultural sector, to be willing to act with, and for, others in pursuit of ending oppression and decolonising museum spaces, or to take an active role in the protection of our natural world for generations to come.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (44 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to sincerely thank interview participants Melanie Barrett, Heather Bleechmore, Tharron Bloomfield, Carolyn McLennan, Chris Redman and Michelle Stoddart for their enthusiasm and engagement with this research and for their significant contributions to the content of this paper. I would like to thank Isabelle Waters, for her work as interview moderator and early editorial contributions. I would also like to thank Daniel Bornstein and Denise Thwaites for their perspectives and contributions around the development of the methodology and topics of humanness and reflexivity. Lastly, thank you to Nicole Tse, Alison Wain, Stacey Chapman and the anonymous reviewers for their generous and constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10344233.2024.2312755.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Asti Sherring

Asti Sherring is the Manager, Changeable and Digital Collections at the National Museum of Australia. Asti previously held the position of Senior Time-based Art Conservator at The Art Gallery of New South Wales. She has also worked at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, University of Newcastle Special Collections Library, National Archives of Australia and Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. Asti is currently undertaking doctorate research at Canberra University.

References

- Abrams, A 2022, ‘Kim Kardashian’s met gala dress angered conservators so much that the International Council of Museums had to make a statement’, Artnet News, 12 May, viewed 2 September 2022, <https://news.artnet.com/art-world/kim-kardashian-marilyn-monroe-dress-2113907#:~:text = Kim%20Kardashian%20attends%20The%202022,guidelines%20on%20handling%20historic%20garments>.

- Althaus C 2020, ‘Different paradigms of evidence and knowledge: recognising, honouring and celebrating indigenous ways of knowing and being’, Australian Journal of Public Administration, vol. 79, pp. 187–207, DOI: 10.1111/1467-8500.12400.

- Ashley-Smith J 2000, ‘Developing professional uncertainty’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 14–17.

- Ashley-Smith J 2017, ‘A role for bespoke codes of ethics’, in J Bridgland (ed.), ICOM committee for conservation, 18th triennial conference, 4–8 September 2017 Copenhagen, International Council of Museums, Paris, viewed 28 July 2023, <https://openheritagescienceblog.files. wordpress.com/2017/09/1901_4_ ashleysmith_icomcc_2017.pdf>.

- Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Material 2002, ‘Code of ethics and code of practice’, AICCM, viewed 6 January 2023, <https://aiccm.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CODE-OF-ETHICS-AND-CODE-OF-PRACTICE-Australian-Institute-for-Conservation-of-Cultural-Material.pdf>.

- Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Material 2010, ‘AICCM history’, AICCM, viewed 12 June 2023, <https://aiccm.org.au/about/aiccm-history/>.

- Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Material 2020, ‘AICCM strategic plan 2020–2025’, AICCM, viewed 1 January 2023, <https://aiccm.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/AICCM-Strategic-Plan-2020-2025.pdf>.

- Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Material 2022, ‘The AICCM 50th anniversary volume: call for papers: cultural materials conservation: self, systems and society’, AICCM, viewed 12 June 2023, <https://aiccm.org.au/publications/aiccm-bulletin/>.

- Avrami, E, Mason, R, Macdonald, S & Myers, D 2019, Values in Heritage Management: Emerging Approaches and Research Directions, Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles.

- Balsiger P & Lambelet A 2014, ‘Participant observation’, in D Porta (ed.), Methodological practices in social movement research, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 144–172.

- Bloomfield T 2023, ‘Considering the impacts of colonization trauma when exhibiting indigenous cultures in museums’, in N Owczarek (ed.), Prioritizing people in ethical decision-making and caring for cultural heritage collections, Routledge, Oxon, pp. 55–64.

- Braun V & Clarke V 2006, ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 3, pp. 77–101, DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Byrne S, Clarke A, Harrison R & Torrence R 2011, ‘Networks, agents and objects: frameworks for unpacking museum collections’, in S Byrne, A Clarke, R Harrison & R Torrence (eds.), Unpacking the collection: networks of material and social agency in the museum, Springer, New York, pp. 3–26.

- Castriota, B 2021, ‘Instantiation, actualization, and absence: The continuation and safeguarding of Katie Paterson’s Future Library (2014–2114)’, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, vol. 60, no. 2-3, pp. 145–160. DOI: 10.1080/01971360.2021.1977058.

- Clavir M 1998, ‘The social and historic construction of professional values in conservation’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 1–8, DOI: 10.1080/00393630.1998.12068815.

- Clavir M 2002, Preserving what is valued: museums, conservation, and first nations, UBC Museum of Anthropology Research Publication, UBC Press, Vancouver, BC.

- Clifford J 1997, Routes: travel and translation in the late 20th century, Harvard University Press, New York.

- Coskun M 2018, ‘Beyond safeguarding measures, or a tale of strange bedfellows’, in N Akagawa & L Smith (eds.), Safeguarding intangible heritage: practices and politics, Routledge, London, pp. 218–231, DOI: 10.4324/9780429507137-14.

- Council of Australasian Museum Directors 2022, ‘ICOM apology prompted by Māori curator 26 May’, viewed 2 September 2022, <https://camd.org.au/icom-apology-prompted-by-maori-curator/>.

- Damasio A 1999, The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness, Harcourt Brace, New York.

- Denzin NK & Lincoln YS 2017, The Sage handbook of qualitative research, 5th edn, Sage Publishing, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Ellis C, Adams T & Bochner A 2010, ‘Autoethnography: an overview’, Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 273–290, <http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101108>.

- Fekrsanati F & Marçal H 2022, ‘Affirming change in participatory practices of cultural conservation’, in C Rausch, R Benschop, E Sitzia & V van Saaze (eds.), Participatory practices in art and cultural heritage. Studies in art, heritage, law and the market, vol. 5, Springer, Cham, pp. 127–141, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-05694-9_10.

- Finlay L 2002, ‘Negotiating the swamp: the opportunity and challenge of reflexivity in research practice’, Qualitative Research, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 209–230, DOI: 10.1177/146879410200200205.

- Gfeller A 2017, ‘The authenticity of heritage: global norm-making at the crossroads of cultures’, The American Historical Review, vol. 122, no. 3, pp. 758–791.

- Gosden C, Larson F & Petch A 2007, Knowing things: exploring the collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum, 1884–1945, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Groth C 2015, ‘Emotions in risk assessment and decision making processes during craft practice’, Journal of Research Practice, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 1–17.

- Haraway D 2008, When species meet, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- Haraway D 2016, Staying with the trouble: making Kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press, Durham, NC.

- Harman G 2016, Immaterialism, Polity Press, Malden, MA.

- Henderson J 2018, ‘Managing uncertainty for preservation conservation’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 108–112, DOI: 10.1080/00393630.2018.1479936.

- Henderson J, Lingle A & Parkes P 2023, ‘Reflexive autoethnography’: subjectivity, emotion and multiple perspectives in conservation decision making’, in J Bridgland (ed.), ICOM-Committee for conservation 20th triennial conference preprints working towards a sustainable past., Valencia, 18–22 September 2023, International Council of Museums, Paris, pp. 1–9.

- Henderson J & Nakamoto T 2016, ‘Dialogue in conservation decision-making’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 67–78, DOI: 10.1080/00393630.2016.1183106.

- Hölling H 2017a, ‘Lost to museums? Changing media, their worlds, and performance’, Museum History Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 97–111, DOI: 10.1080/19369816.2017.1257873.

- Hölling H 2017b, ‘The technique of conservation: on realms of theory and cultures of practice’, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 87–96, DOI: 10.1080/19455224.2017.1322114.

- Hölling H 2017c, Paik’s virtual archive: time, change and materiality in media art, Oakland University of California Press, Los Angeles.

- Ingold T 2015, The life of lines, Routledge, London.

- International Council of Museums 2022, ‘ICOM approves a new museum definition’, ICOM website, 24 August, viewed 28 July 2023, <https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-approves-a-new-museum-definition/>.

- Johnston M 2006, ‘The lamp and the mirror: action research and self-studies in the social studies’, in KC Burton (ed.), Research methods in social studies education: contemporary issues and perspectives, Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, NC, pp. 57–83.

- Latkowski M 2021, ‘Remote qualitative interviews. A contributions towards the analysis of remediation’, Journal of Education Culture and Society, no. 1, pp. 202–211.

- Laurenson P 2008, ‘Authenticity, change and loss in the conservation of time-based media installations’, in J Schachter & S Brockmann (eds.), (Im) permanence: cultures in/out of time, Center for the Arts in Society, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, pp. 150–164.

- Lizzo 2022, ‘Nobody has ever heard the crystal flute before 28 September’, Twitter Post, viewed on 10 October 2022, <https://twitter.com/lizzo/status/1575003731640274944?ref_src = twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1575003731640274944%7Ctwgr%5Ed34d2a4cf53c88b97354369fb9e4f2dadd750c2d%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url = https%3A%2F%2Fwww.npr.org%2F2022%2F09%2F28%2F1125564856%2Flizzo-james-madison-crystal-flute-concert>.

- Marçal H & Gordon R 2023, ‘Affirming future(s): towards a posthumanist conservation in practice’, in C Daigle & M Hayler (eds.), Posthumanism in practice, Bloomsbury Academic, London, pp. 165–178.

- Marçal H, Macedo R & Pereira A 2014, ‘The inevitable subjective nature of conservation: psychological insights on the process of decision-making’, in J Bridgland (ed.), ICOM committee for conservation 17th triennial conference preprints, Melbourne, 15–19 September 2014, International Council of Museums, Paris, art. 1904, 8 pp.

- Muñoz Viñas S 2005, Contemporary theory of conservation, Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford.

- Murphy C 2020, ‘Physical object or variable, flexible, ephemeral and reproducible: the management and care of contemporary art collections in 2020’, AICCM Bulletin, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 45–51, DOI: 10.1080/10344233.2020.1788880.

- Murphy C & Treacy A 2018, ‘Drawings you can walk on – Mike Parr and the 20th Biennale of Sydney 2016’, AICCM Bulletin, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 76–85, DOI: 10.1080/10344233.2018.1507504.

- Museums are not Neutral 2017, ‘Homepage: museums are not neutral’, viewed 6 January 2023, <https://www.museumsarenotneutral.com/>.

- Owczarek N 2023, Prioritizing people in ethical decision-making and caring for cultural heritage collections, Routledge, Oxon.

- Pearlstein E 2017, ‘Conserving ourselves: embedding significance into conservation decision-making in graduate education’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 62, no. 8, pp. 435–444, DOI: 10.1080/00393630.2016.1210843.

- Phillips J 2012, ‘Shifting equipment significance in time-based media artworks’, EMG Review, vol. 1, pp. 139–154.

- Phillips L & Zavros-Orr A 2012, ‘Researchers as participants, participants as researchers: ethics, epistemologies, and methods’, in W Midgley, P Danajer & M Baguley (eds.), The role of participants in education research: ethics, epistemologies, and methods, Routledge, New York, pp. 52–63.

- Pienkowski T, Kiik L, Catalano A, Hazenbosch M, Izquierdo-Tort S, Khanyari M, Kutty R, Martins C, Nash F, Saif O & Sandbrook C 2023, ‘Recognizing reflexivity among conservation practitioners’, Conservation Biology, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 1–12, DOI: 10.1111/cobi.14022.

- Pratt ML 1992, Imperial eyes: travel writing and transculturation, Routledge, London.

- Pye E & Sully D 2007, ‘Evolving challenges, developing skills’, The Conservator, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 19–37, DOI: 10.1080/01410096.2007.9995221.

- Richmond A & Bracker A 2009, Conservation: principles, dilemmas and uncomfortable truths, Butterworth Heinemann in Association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

- Rowlands J 2021, ‘Interviewee transcript review as a tool to improve data quality and participant confidence in sensitive research’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 20, pp. 1–11, DOI: 10.1177/16094069211066170.

- Scott M 2015, ‘Normal and extraordinary conservation knowledge: towards a post-normal theory of cultural materials conservation’, AICCM Bulletin, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 3–12, DOI: 10.1179/0313538115Y.0000000002.

- Sherring A, Bloomfield T, Barrett M, Stoddart M, McLennan C, Bleechmore H, Redman C & Waters I 2023, ‘Interview transcript of a semi-structured interview with six conservation professionals’, in Embracing humanness in cultural materials conservation: a roundtable discussion with conservation professionals on ethics, values and the future, Figshare Online Resource, DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.24708237.v2.

- Sherring A, Cruz M & Tse N 2021, ‘Exploring the outlands: a case-study on the conservation installation and artist interview of David Haines’ and Joyce Hinterding’s time-based art installation’, AICCM Bulletin, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 13–25, DOI: 10.1080/10344233.2021.1982540.

- Sherring A, Murphy C & Catt L 2018, ‘What is the object? Identifying and describing time-based artworks’, AICCM Bulletin, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 86–95, DOI: 10.1080/10344233.2018.1544341.

- Sloggett R 2009, ‘Expanding the conservation canon: assessing cross-cultural and interdisciplinary collaborations in conservation’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 170–183.

- Sloggett R & Wain A 2020, ‘Cultural materials conservation in Australia: critical reflections and key issues in the twenty-first century’, AICCM Bulletin, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 1–2, DOI: 10.1080/10344233.2020.1831826.

- Smith L 2006, Uses of heritage, Routledge, London.

- Smith J 2020, ‘Information in crisis: analysing the future roles of public libraries during and post-COVID-19’, Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 22–429, DOI: 10.1080/24750158.2020.1840719.

- Stigter S 2016, ‘Autoethnography as a new approach in conservation’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 227–232, DOI: 10.1080/00393630.2016.1183104.

- Sweetnam E & Henderson J 2022, ‘Disruptive conservation: challenging conservation orthodoxy’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 67, no. 1-2, pp. 63–71, DOI: 10.1080/00393630.2021.1947073.

- Taylor C 1989, Sources of the self: the making of the modern identity, Harvard University Press, New York.

- The Uluru Statement from the Heart 2022, ‘Website homepage: history is calling’, viewed 15 December 2022, <https://ulurustatement.org/>.

- The Value 2020, ‘#BlackOutTuesday: the art world posts black squares on social media to show support’, The Value, 3 June, viewed 7 October 2022, <https://en.thevalue.com/articles/blackouttuesday-george-floyd-art-industry-museum-auction-house>.

- Van de Vall R 2009, ‘Towards a theory and ethics for the conservation of contemporary art’, in Art D’Aujourd’Hui—Patrimoine de Demain Conservation et Restauration des Oeuvres Contemporaines, 13es journées d’études de la SFIIC, Institut National du Patrimoine, Paris, pp. 51–56, viewed 30 July 2023, <https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/en/ publications/towards-a-theory-and-ethics-for-the- conservation-of-contemporary->.

- Van de Vall R, Holling H, Scholte T & Stigter S 2011, ‘Reflections on a biographical approach to contemporary art conservation’, in J Bridgland (ed.), ICOM committee for conservation 16th triennial conference preprints, Lisbon, 19–23 September 2011, Critério, Almada, pp. 1–8.

- Van Saaze V 2009, ‘Doing artworks. An ethnographic account of the acquisition and conservation of no ghost just a shell’, Krisis, vol. 1, pp. 20–32, <http://www.krisis.eu/content/2009-1/2009-1-03-saaze.pdf>.

- Wain, A 2011, ‘Values and significance in conservation practice’, in Proceedings of the AICCM national conference, Canberra: 19–21 October 2011, viewed 19 December 2022, <https://aiccm.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/WAIN_NatConf2011.pdf>.

- Wain A & Sherring A 2020, ‘Changeability, variability, and malleability: sharing perspectives on the role of change in time-based art and utilitarian machinery conservation’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 66, no. 8, pp. 449–462, DOI: 10.1080/00393630.2020.1860672.

- Wei, W 2022, ‘Authenticity and originality, Objectivity and subjectivity in conservation decision-making – or is it just a matter of taste?’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 67, no. 1-2, pp. 15–20. DOI: 10.1080/00393630.2021.1940796.

- Wharton G 2008, ‘Dynamics of participatory conservation: the Kamehameha I sculpture project’, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 159–173, DOI: 10.1179/019713608804539592.

- Wharton G 2018, ‘Bespoke ethics and moral casuistry in the conservation of contemporary art’, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 58–70.