ABSTRACT

Images of improperly-discarded waste offer a case for examining the broader politics of “pristine nature.” As a global visual register in which the environment is depicted without human impact, an historicization of pristine nature reveals how it was enregistered through the Romantic and Transcendental movements as well as colonial ideologies of the wilderness. Informed by fieldwork in Oman and 300 Instagram posts collected between 2021–23, “untouched nature” and the “self-in-nature” are identified as two genres of pristine nature. Yet their citation in Oman spurs a question: does history always implicate a contemporary sign? The identification of a third genre, “anti-litter,” pursues this question by investigating what happens when the camera is turned upon trash. Despite the association of anti-litter with sustainability, the genre was similarly enregistered through a complicated history. Its citation in Oman, however, demonstrates that actors wield genres in response to sociocultural and political-economic context, suggesting the grounds from which a semiotics of sustainability might emerge.

Introduction

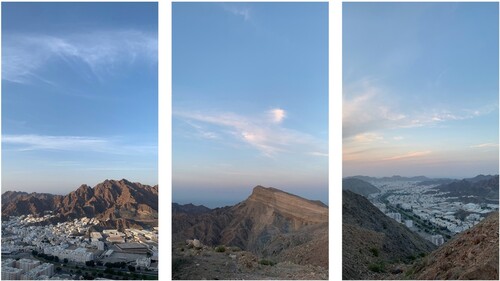

One afternoon in March 2023, I met up with a group of hikers on the outskirts of Muscat, the capital city of Oman. Guiding us on the easy, end-of-the-workday hike was Jamal, 24, co-owner of an adventure tourism company that he and a group of friends launched during the COVID-19 pandemic. About a dozen of us hikers followed Jamal on a path between rugged mountains hugging the Arabian Peninsula coast, until we came to a picnic area overlooking a valley of bright white buildings. Along with other hikers, I reached for my phone to take a photo, with the notion of capturing something for my Instagram. As we stood framing the view on our phone screens, Jamal turned suddenly and said, exasperated, “The trash is ruining the picture!”

At our feet and all around the overlook were clusters of rubbish: plastic bottles, empty bags, crumpled foil, and other discards of picnickers. This was not an unusual encounter at popular picnic areas in Oman, and without dwelling on the matter we continued hiking toward other, less trash-filled viewpoints. Only after I had sat down alone that evening to write up my notes did I come back to Jamal’s remark. Then, looking over my own photos from the hike, I found that – without thinking about it – at the picnic overlook I had carefully composed frames which hid any sign of the rubbish littering the ground (). I posted them.

Why does litter threaten to “ruin” a picture? Answering this seemingly simple question can tell us a great deal about the representation of nature, or the more-than-human environment, and especially about how imagery is used to promote environmental sustainability. The portrayal of nature in an idealized, trash-less state – a landscape genre I will refer to as “pristine” nature – extends far beyond the pictures taken by hikers. From corporate advertising campaigns to nature documentaries, the environment is routinely depicted without human impact: no trash, but also no urbanization, no biodiversity loss, and no carbon dioxide saturating the atmosphere. Yet more than its circulation as a kind of widely recognizable, everyday imagery associated with the environment and its discursive representation, pristine nature is actively produced in such spaces as social media – even when doing so requires, consciously or otherwise, a careful pointing of one’s camera away from trash.

Both pristine nature and trash can be located within a broader corpus of environmental discourses, or ways that people talk about, think about, conceptualize, and represent the more-than-human world. While research on environmental discourses is expansive, this article is focused upon visual representation, following semiotic approaches that understand images as signifiers discursively constructed by an individual actor’s choices as well as sociocultural ideologies (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2021). Hansen and Machin (Citation2013, 155) argue that “the public vocabulary on the environment is to a large extent a visual vocabulary,” through which the environment is depicted according to three categories: a resource to be used, a residence of the pristine, and a fragile space in need of protection. This article takes up these latter two categories, seeking to historicize and define the semiotics of “pristine nature” and to evaluate the signification of pristine nature in environmental “protection,” or sustainability efforts. To do so, I focus on the circulation of pristine nature in social media, and also another, perhaps unexpected genre: one in which trash ruins the picture.

This article turns first to Oman, the place where I went hiking with Jamal and where I have been spending time digitally and in-person since 2022. As the first section shows, Oman is particularly instructive for understanding the globalized dynamics of pristine nature, as this regime has become locally prominent only recently and through a process far removed from its historical, that is to say, European origins. I then discuss two genres of pristine nature that circulate within Oman’s digitally networked public, revealing that for two hundred years pristine nature has been constructed through an avoidance or omission of disruptive signs. From this I turn to the case of how, amongst the surfeit of pristine nature imagery, social media users in Oman also post pictures of trash, which rather than ruining the picture calls attention to unsustainable practices and makes a plea for more environmentally-conscientious behavior. Yet depictions of trash have a complicated history, too. Through investigating a final example from Oman-based social media, this paper asks two questions: Does history always implicate a contemporary sign? And if not pristine nature, what are a semiotics of sustainability?

Seeing the landscape: Oman before nature tourism

Visual representations of the landscape are well understood as a discursive form of representing a society in relation to the land and/or environment (Cosgrove Citation1998). Pristine nature is signified through a separation of “natural” landscapes from people, informed by a largely Euro-American ideology premised upon a dichotomous separation of humans from the ostensibly non-human, or what can be shorthanded as the nature/society binary (Castree Citation2013). Ideologically and politically structured “ways of seeing” (Berger Citation2008) the landscape are framed through epistemological imperatives and biases, and in globalized art, media, and commerce are most readily associated with a visual tradition that first emerged in northern Italy and the Low Countries in Europe. The visual representation of the land as seen from a single eye, with distances typically divided into a fore-, middle-, and background, emphasized ocular ways of perceiving the world and became a key tableau through which modernity would take shape (Osborne Citation2000).

If Western ways of seeing are perhaps the most prominent through which landscape is today represented, it should not be forgotten that they are but one of many ways through which land and environment have been sensed. In tracing the history of landscape in the Classical Arabic-Muslim world, Latiri (Citation2001) shows that landscape was represented not visually as in the European tradition, but through written literature and especially poetry. She outlines five general modes: as sites which might be reasonably developed for agriculture, paradisiacal gardens, pastoral land under cultivation, picturesque appreciation of historical sites, and panoramas gazed at from a great vantage. Taken together, Classical Arabic-Muslim culture possessed “a terminology of landscape, an art of gardens, [and] poetical texts depicting various landscapes,” which differed substantially from what developed in Western Europe (Latiri Citation2001, 16).

Notably, these ways of seeing landscape did not include pristine nature, a formation that cohered beginning in late-eighteenth century Europe (see following section). Yet neither was the more-than-human environment perceived in the Arabic-Muslim world as a threatening or even abhorrent realm. While mountains in Western cultures were typically regarded as ugly and inhospitable before the rise of late-eighteenth century Romantic aesthetics (Nicolson Citation1997), for Arabic speakers mountains were more often understood as places of refuge; among other passages, the Qur'an 16:81 (Citation2010, p. 277) states that God “has given you shade from what He has created, and places of shelter in the mountains.” Such places of shelter can be found throughout the rugged mountains of the Arabian Peninsula, where myriad villages were founded in canyons or on plateaus that could only be reached by a difficult hike with a mule, or even by scrambling up an exposed cliff that would have most contemporary rock climbers demanding a rope.

The Sultanate of Oman is home to many such villages, with its geography composed of mountain peaks exceeding 3000 m and countless steep-sided valleys. It is a particularly instructive context for understanding the visual representation of nature. In contrast to parts of the world such as Western Europe or North America, where recreational activities in the non-human environment have been established practices in some form since the nineteenth century, hiking and adventure sports only started to become broadly popular among locals in the past decade. As confirmed through numerous interviews with tour operators, guides, and newcomers to the outdoors, the visibility of these activities on social media in the mid-2010s and then the border closures due to COVID-19 lead to an unprecedented expansion of domestic nature tourism (see Smith, forthcoming). This growth has been further mobilized by both entrepreneurial investment and the Omani government, which has described tourism as a key pillar in its transition to an economy that is not reliant upon fossil fuels (Implementation Citation2022). Like other Gulf countries, Oman is governed by an absolute monarchy with power transferred through family lineages, and is home to about five million people. While the majority are Arab Omani citizens, about 40% of the population are “expats”: the local term for non-permanent residents who, as in other Gulf countries, make up a vast plurality of the workforce and mostly carry passports from Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.

This is not to say that no one in Oman interacted with nature prior to the past ten or so years. To the contrary, the more-than-human world was deeply interwoven with the lives of most Omanis prior to the country’s post-1970s industrialization. Communities from the mountains to the plains were shaped around agriculture and animal husbandry, and were characterized by deep ties of kinship with non-humans and the land that Alhinai and Milstein (Citation2019, 1079) describe as a “spiritual mutualist worldview” differing markedly from the nature/society dualism of globalized Western discourses. Today, although mutualism is being supplanted by dualism (ibid), these ties remain strong among Omanis living in rural and urban environments alike, as many city-dwellers travel often to visit extended family networks in the villages from which they hail, even if they have lived several generations in the city.

Even more frequent than village visits, however, are picnics: a group of family or friends will drive to an outdoor location and park their car, next to the highway or after kilometers of intrepid off-roading, laying blankets upon the ground and for hours sharing food and coffee. Some picnickers use the occasion to engage in the sorts of activities that have become more popular in recent years. Othman, a recent university graduate who lives near the city of Nizwa, told me that he first went hiking as a child while out on a picnic – but, he said, “we didn’t call it hiking back then.” As this article shows in part, the circulation of images and discourses via social media played a key role in the transformation of ways of seeing nature in Oman, in tandem with the growth of tourism.

Data, analysis, and fieldwork in Oman

The arguments advanced in this article were developed through an ongoing project examining the influence of social media and tourism on perceptions of nature in Oman,Footnote1 with the generous collaboration of many people who live there (some of whom have kindly shared their Instagram posts for this article). I began digital fieldwork in December 2021, when I opened an Instagram account declaring my position as a researcher and began interacting with users in Oman. While digital fieldwork is ongoing and I currently follow more than 700 users based in the country, I have spent four months in Oman over the course of five trips between March 2022 – February 2024. During this time, I have recorded dozens of interviews with Omani citizens, residents, and tourists, with many interactions facilitated by my conversational level of spoken Arabic. While this material affirms my conclusions, limited space precludes its discussion (rather see Smith, forthcoming), and the primary data for this article is instead a sample of 300 Instagram posts.

Between December 2021 – December 2023, I used the account I created for this project to collect 505 Instagram posts made by users who live in or were visiting Oman. I took screenshots of posts related to nature tourism, made by hikers, “adventurers,” sightseers, and picnickers. My research design initially did not focus on trash and the semiotics of pristine nature, but instead this topic arose through the anthropological tradition of inductive analysis, as these categories were made salient over the course of long-term observation and recursive coding (Lecompte and Schensul Citation2013) as well as by interviewees, who urged their importance. From my initial set of posts, I selected 300 that depicted “nature” and trash in nature, choosing posts by users who live in Oman. From this set, three categories were generated: “untouched nature,” in which the environment is shown without human impact (31 posts); the “self-in-nature,” in which a lone figure is immersed in the environment (79 posts); and “anti-litter,” in which improperly-discarded rubbish is shown in the environment (64 posts). The traits of each category, or “genre,” are discussed below.

“Pristine nature”: tourism and the global circulation of a visual register

While concepts of nature vary, “pristine” nature is rooted in a value for an environment allegedly unadulterated by humans, a formation epistemically grounded within Western discourses of paradise (Deckard Citation2009) and a Romantic/Transcendental affinity for the wilderness (Nash Citation2001). While the writings of numerous explorers, travelers, poets, and theorists substantially contributed to the discursive shaping of pristine nature, this article is primarily concerned with its visual representation, beginning with the understanding that publicly-displayed images are always ideologically implicated and are formed through individuals drawing upon a repertoire of known signifiers within a given context (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2021). In analyzing the semiotic configuration of an image, attention must be focused upon the genealogy of its “canon of use,” or the ideological collocation of multimodal resources that recurrently communicate a coherent set of ideas (Ledin and Machin Citation2018, 22). Pristine nature is composed of one such canon, the signification of which is among the most prominent ways in which nature is visually depicted; as Hansen and Machin (Citation2013, 161) write, next to the representations of nature as a resource to be exploited or to be protected, the most common depiction is “a romantic and romanticized view of nature as sublime, pristine, the home of authenticity.”

Within most Western cultural formations, value for and representation of nature and the so-called “natural” landscape can be traced to the pastoral tradition. Inaugurated by Ancient Greek poets who rhapsodized simpler times in which people lived harmoniously with the environment, the pastoral sentimentalized rural communities and economies (Williams Citation1973), and in the Renaissance-era turn to secular art it informed a value for scenes of agrarian life. In the development of landscape painting in the Low Countries and Italy, visions of the environment without the impact of human alteration were rare, excepting those which depicted Biblical wildernesses of terror and temptation. Following Burke's (Citation1958) theorization of the sublime, however, the prospect of nature without human cultivation became a site for metaphysical experience and therefore visual artistic representation. Kant further developed the sublime as an aesthetic response to an encounter with nature that escapes the boundaries of the imagination, which, he theorized, stimulated both a reflexive appreciation for the self and for the environment which gave it rise (Brady Citation2003). The sublime began to inform philosophy, aesthetics, and art in the same period in which modern tourism emerged out of the aristocratic Grand Tour. While a minority of Grand Tourists began to interpret the Alps as a sublime landscape, it was in the sublime’s transmutation into picturesque tourism that the “natural” landscape become a typified object of visual consumption (cf. Urry Citation1992).

While the semiotics of pristine nature coalesced in Western Europe during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, its visual representation today can be encountered around the world in contexts ranging from digital platforms to emplacements in the physical semiotic landscape (Kosatica Citation2024). This process of global circulation began with the historical “enregisterment” (Agha Citation2006) of pristine nature, through which the centuries-long interface of art, tourism, and (later) nation-building led to the ideological investment of its semiotic canon of use with sociocultural value. As a semiotic register, pristine nature is collated within visual genres; to extend Bakhtin’s (Citation2014, 75) formulation, these genres are interdiscursive “types” (Silverstein Citation2005, 9) of image comprised of select signs within a shared canon of use and which are dialogically embedded within the long history of pristine nature’s representation. Genres are sustained through “semiotic chain[s]” of linked discourse events (Agha Citation2006, 205), as participants draw upon a semiotic canon to “cite” a prior event while attempting to reflexively position the new event as unique (Nakassis Citation2013, 54). Such citation of enregistered signs within long-running semiotic chains is shaped by political-economic context (Smith, Järlehed, and Jaworski Citation2023).

While the citation of pristine nature is indeed global, the context with which this article is concerned is social media – and specifically Instagram, the platform that in Oman is the most popular for engaging nature. As spaces in which publics congregate and become interlinked, or “networked” (boyd Citation2010, 39), the infrastructure of social media platforms give shape to affordances that enable and constrain the kinds of actions which a user can undertake (Bucher and Helmond Citation2017). Instagram affords for the posting of still images and videos, called “Reels,” which are elaborated by captions and soundtracks and may be dialogically affiliated with platformed discourses through hashtags (Zappavigna and Martin Citation2018) as well as physical places through the feature of geotagging. Further to this, the dialogical interplay of Instagram’s infrastructure – in which users are exposed not just to others’ posts, but to whether the users one follows “likes” a post or even shares it via the Stories feature – facilitates the citational uptake of genres encountered on the platform. In other words, previously-seen images of a genre serve to “mediate” users’ representational practices (Thurlow and Jaworski Citation2014, 470), who, in their own Instagram posts, cite not just the semiotic register but the enactments of its form which they themselves have encountered on the platform. To better understand the circulation of pristine nature, however, we might now turn to its best-represented genres, while questioning to what extent contemporary citations “carry” that genre’s “history with it” (Bauman and Briggs Citation1990, 75).

“Untouched nature”

The first genre of pristine nature in my sample, comprising 31 posts, is “untouched nature”: an image of the non-human environment in which human presence or impact is not (easily) identifiable. In a Reel by photographer Ahmed Al Nairi (@aa5.5d; (a)), a timelapse captures clouds drifting over the craggy flanks of Jebel Aswad after sunset. The dramatic view, accessible only via a challenging and little-known hike, recalls the sublime yet is firmly grounded in Oman with a soundtrack of a plucked oud. A second example comes from photographer and adventure guide Abdullah Alhadidi (@qdo_; (b)), whose post features a stream rushing over a cleft into a pool of deep emerald water in one of Oman’s many canyons, or wadis. In the expertly composed photograph, only a wayward torso on the left side of the frame can disrupt the vision of nature-without-humans for the most scrutinizing viewer. Yet this easily-missed detail discloses a key feature of untouched nature: that its semiosis is carefully constructed to elide human impact.

Figure 2. (2a, left) Ahmed Al Nairi's (@aa5.5d) Reel captures moving clouds above Jebel Aswad in Oman. (2b, middle) Abdullah Alhadidi's (@qdo_) Instagram post of a wadi, or canyon, in Oman. (2c, right) Chris Burkard's (@chrisburkard) Instagram post of a canyon in the United States.

Alhadidi’s photograph in Oman cites a globalized genre, which is further represented by photographer and influencer Chris Burkard (@chrisburkard; (c)) who, with 3.3 million Instagram followers, is broadly indicative of the genre’s citation of enregistered values for authenticity and metaphysical experience. Captioning his photograph of a canyon at sunset, Burkard writes: “How long was this land completely undisturbed before a human happened upon the sight?” With the possible exception of a steep trail that cuts down to the high embankment in the bottom right of the frame, the landscape unfolds seemingly without human intervention. The separation of humans from nature recalled in Burkard’s post is in fact a relatively recent object of visual interest. Where the sublime was prefigured by a human encounter with nature, and the picturesque gravitated toward representations of the rural working classes or human-built architectural ruins, “untouched nature” only became enfranchised in art in the middle of the nineteenth century, and largely under the influence of North American Transcendentalism.

Among the earliest visualizations of nature without human intervention is the sunset scene in Frederic Edwin Church’s Twilight in the Wilderness (1860; ).Footnote2 The title of Church’s painting provides a clue to the ideological underpinnings of this shift, with the valorization of “wilderness” – land where, according to its discursive formation, humans are but a fleeting presence. In the European colonization of the Americas, the wilderness was first perceived as a condition which must be dominated, but under the influence of the Romantic sublime and, later, the Transcendentalists, it became a site for a spiritual encounter with nature or a means of shaping one’s moral and physical fiber through the trials of the frontier. Yet as Cronon (Citation1996, 8) argues in his well-known essay, wilderness is a “cultural invention”: its encounter in the Americas was formed first through the European-introduced pandemic diseases and subsequent genocidal conquests, which killed approximately 90% of the continent’s indigenous inhabitants (Denevan Citation1992), and later by the policies of forced relocation which further de-peopled the land that became designated as national parks (Taylor Citation2016). While human absence could always be imagined in paintings, in photographs the production of “untouched nature” has from the beginning incurred pointing the camera away from the evidence of human impact, establishing a semiotic blueprint for what became the international environmental conservation movement (DeLuca and Demo Citation2000). Untouched nature comprises a backdrop for the next, more common genre, which is likewise steeped in a complex politics.

Figure 3. Frederic Church, Twilight in the Wilderness, oil on canvas, 1860, Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twilight_in_the_Wilderness#/media/File:Twilight_in_the_Wilderness_by_Frederic_Edwin_Church_(3).jpg

The “self-in-nature”

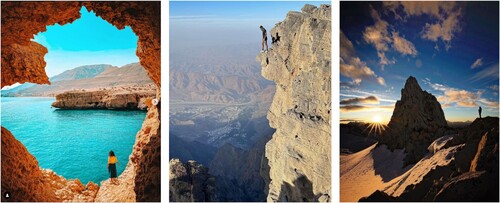

The most represented genre in my sample, with 79 posts, features a single person who does not face the camera but is immersed within “untouched nature.” In a striking example, journalist Rumpa Mitra (@rumpa_mitra) stands framed by the mouth of a limestone cave, gazing out upon the azure waters of the Gulf coast ((a)). With her back to the camera, the audience is invited to share in the direction of her gaze and vivifying encounter with nature undisturbed by the picturesque rumor of a village on the far shore. Another indicative citation comes from Qasim Al Naabi (@qasim_.s; (b)), who fearlessly stands at the precipice of a cliff high up in the Eastern Hajar Mountains as the tangibility of mortal danger – if not for Qasim, then for his audience – vividly invokes the sublime. These compositions are readily recognized as a citation of the widely-recurring “promontory witness” motif, in which a typically lone human figure gazes outward upon a metaphysically resonant landscape (Smith Citation2021). Self-in-nature compositions are not only more common in Oman-based social media but globally, such as in a post by photographer and mountaineer Jimmy Chin (@jimmychin; 3.5 m followers) featuring a single figure standing upon a ridgeline promontory at sunrise ((c)).

Figure 4. (4a, left) Rumpa Mitra (@rumpamitra) gazes out upon the coastline of Oman. (4b, middle) Qasim Al Naabi (@qasim_.s) looks down from the top of Jebel Aswad, Oman. (4c, right) Jimmy Chin's (@jimmychin) Instagram post in British Columbia.

The origins of the self-in-nature reach much deeper than the untouched, and from its earliest instantiation was rooted in expressions of power and (national) identity (Mitchell Citation2002). Depictions of human figures or structures emplaced within a (semi-)natural landscape germinated predominantly in the Low Countries, articulating a pastoral poetics and national pride in scenes of cultivated land during the so-called Dutch “Golden Era,” a form which Jacob van Ruisdael’s Wheat Fields (1670) epitomizes ((a)). In the reification of nature with sublime philosophy and the Romantic movement, however, human figures ventured out into “untouched” landscapes, such as in Johann Heinrich Wüest’s Der Rhonegletscher (1775) where a small party in the Alps is dwarfed by a staggering field of ice that threatens to engulf them – if not physically, then sensorially ((b)). Such minute human figures or traces of settlement have throughout the tradition of European landscape art served as “witness figures,” performing a symbolic “capturing or laying claim” to the land being depicted (Bordo Citation2002, 297) – and accordingly, to the metaphysical meanings to which the land gives rise.

Figure 5. (5a, left) Jacob van Ruisdael, Wheat Fields, oil on canvas, 1665–1670, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wheat_Fields_(Ruisdael)#/media/File:Wheat_Fields_MET_DP145911.jpg. (5b, right) Johann Heinrich Wüest, The Rhône Glacier, oil on canvas, 1775, Kuntshaus Zurich, Zurich, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Heinrich_W%C3%BCest#/media/File:Der_Rhonegletscher_-_Johann_Heinrich_W%C3%BCest_(Kunsthaus_Z%C3%BCrich).jpg

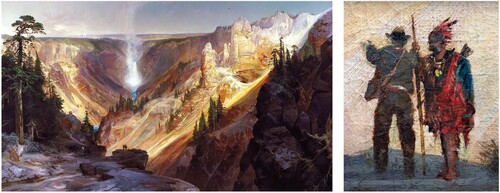

Such exercise of power is perhaps best articulated in Thomas Moran’s The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (1872; (a)), produced following sketches the painter made while accompanying an 1871 United States government federal survey of the American “frontier”: those western territories from which indigenous peoples were being brutally extirpated to make way for Euro-American settlers. At more than two meters long and wide, the grand painting was purchased by the US government and is widely recognized as mobilizing support for Yellowstone National Park’s 1872 creation; today, it still hangs in the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. A careful inspection of the witness figures standing at a promontory atop a boulder reveals one of the American surveyors in apparent consultation with a colorful figure whose head is crowned in red feathers ((b)). In a scene of “anti-conquest” (Pratt Citation1992), the settler is seen in peaceful cooperation with a Native American, the physical embodiment of the “wilderness” myth who genially brokers the United States’ westward expansion. Moran’s, and indeed America’s gaze constructs a national identity empowered through its control of pristine nature, capturing yet simultaneously erasing the indigenous history which preceded the state.

Figure 6. (6a, left) Thomas Moran, The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, oil on canvas, 1872, National Statuary Hall, United States Capitol, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Grand_Canyon_of_the_Yellowstone_(1872)#/media/File:Thomas_Moran_-_Grand_Canyon_of_the_Yellowstone.jpg. (6b, right) Detail of the two figures standing at the promontory in Moran’s Grand Canyon.

Perhaps nowhere are the confluences of nature and nation-state more evident today than in tourism, where the “natural” environment has become steadily more central to destination branding and advertised activities (e.g., Wilson Citation2022). With tourism a key pillar in the post-oil economic plans of most Gulf countries, the citation of the self-in-nature occurs in a context where it is to the state’s advantage for local nature to meet globalized ideals. The self-in-nature genre, in which no human imprint upon the landscape is readily discernible but for a single figure (often occupying a promontory position), is indeed articulated within a broader genre of tourism photography that strives for depopulated scenes (Urry and Larsen Citation2011, 175) and frequently guides nature tourism gazes (Fälton Citation2024). As the number of tourists has grown exponentially in the past few decades (and COVID-19 only briefly interrupting international travel), at popular sites this is often only achievable through a careful pointing of the camera away from other tourists. Much as with other semiotic enunciations of elite or privileged access to sought-after space in tourism photography, constructing the “silence of nature” (Thurlow and Jaworski Citation2010, 196) both reaffirms the enregistered value of pristine nature and symbolically associates that value with the user whose post successfully cites one of its genres in a moment of “contact” (cf. Lamb Citation2021).

Locating the problematics of the self-in-nature in contemporary Instagram posts, however, is not so easy as saying that all citations are implicated in historical processes of erasure or nation-building. As with untouched nature, the enregistered value of the self-in-nature is the grounds through which the genre circulates globally, just as readily suggesting a decontextualization of the form as it does a reprisal of history. Contexts such as Oman are very distantly removed from North American settler-colonialism, and nature tourism a very new practice among citizens and residents. At least in the case of residents, articulations of the nation-state can be complicated since – as in other Gulf countries – residency does not provide a pathway to citizenship. If American power and hegemony supported the global enregisterment of pristine nature, might not its citation in Oman represent a postcolonial appropriation, a meaningful “bracketing” (Nakassis Citation2013, 57) through which the politics of the “original” genre are – in an inversion of the form’s semiotic logic – actually erased? Or is it instead impossible for pristine nature to escape the context of its enregisterment? To begin to answer these questions, we can now turn to pristine nature’s seeming opposite.

Anti-litter: trash and the globalized semiotics of sustainability

Amidst all the careful positioning of camera frames to articulate a semiotics of pristine nature, the presence of 64 posts in my sample that are “ruined” by trash demands attention. In one iteration, a widely-reposted Reel by Haitham Al Shaaibi (@haitham_sur) shows a beach covered in plastic rubbish in a post styled as a public service announcement about the dangers of litter for local wildlife ((a)). Alternatively, users feature themselves cleaning up, such as one scuba diver who holds aloft a bag of rubbish collected during a clean-up off the coast ((b)). Others demonstrate proper wasting practices, as Faisal Al-Hooti (@faisal_alh00ti) does in a Stories video during a long-distance bike ride of himself throwing an empty can into a designated receptacle ((c)). Anti-litter posts in Oman are broadly intended to inspire conscientious behavior in a region where litter remains at the forefront of concerns for the environment. Such deliberate manifestation of litter on social media platforms commonly associated with visualizations of beauty and glamor comprises a genre of its own, and one which likewise circulates globally; to take one example, in an arresting shot citing the #followmeto trend of mid-2010s Instagram travel imagery, the aggregator @indiapictures encourages viewers to “FOLLOW ME TO THE CITY OF PLASTIC” ().

Figure 7. (7a, left) A still image from Haitham Al Shaaibi’s Instagram Reel in Oman. (7b, middle) An Instagram post from a clean-up dive off the coast of Oman, user’s identity redacted. (7c, right) Faisal Al-Hooti’s (@faisal_alh00ti) Instagram Stories post of a cleanup practices during a bike trip in Oman and the United Arab Emirates.

Pictures of litter are startling. In surprising or even shocking viewers, such images demand that attention is paid to what is most often ignored or made invisible (Alexander and O’Hare Citation2020; Thurlow, Pellanda, and Wohlgemuth Citation2022). While performing environmentally-sound wasting practices on social media is a form of identity work (cf. Thurlow Citation2022), no less is it a strategic move aimed at bringing about social change; as Hawkins (Citation2006, 14) writes, attending to the brute reality of global waste and its pollution of the environment shifts normative relations, and can inaugurate “different habits.” In centralizing human “problems” with the environment (cf. Hansen Citation2018), the anti-litter genre is one form of environmental discourse, and can be located within broader sustainability discourses urging social and structural transformations.

Although it is notoriously slippery to define, in environmental terms “sustainability” is generally understood as the assurance that “global life-support systems” can be indefinitely maintained (Goodland Citation1995, 6). While concepts of sustainability in Western discourses can be traced back to the medieval era if not to the ancient Greeks (Grove Citation1995), in its current incarnation sustainability became identified with broader agendas of environmental conservation in a 1987 communique issued by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (commonly known as the Brundtland Report), which called for development to proceed in such a way that the needs of “future generations” would not be compromised (Dresner Citation2008). As sustainability has increasingly become a global political and consumer watchword, however, the semiotic resources mobilized for its representation tend to be more closely aligned with pristine nature than with the anti-litter genre.

As consumers became more aware of environmental issues throughout the twentieth century, corporate use of nature-related representations dramatically expanded (Howlett and Raglon Citation1992). In advertising products, using nature-inspired imagery is known to convince customers that a company is ecologically sound (Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015), even as the apparent indexing of sustainability oftentimes does not correlate to the actual environmental practices undertaken by the companies in question (Milanesi, Kyrdoda, and Runfola Citation2022). Such “greenwashing” extends far beyond corporate advertising, however. Even the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – perhaps the most widely-recognized emblems of global sustainability efforts – are represented through imagery that distorts sustainability’s meaning. Through the proliferation of “natural” symbolic imagery, diagrams, and colorful infographics, the SDGs are shown to reify vague aims into actionable policies while obscuring neoliberal capitalism as a fundamental driver of unsustainability (Machin and Liu Citation2023).

The entanglement of pristine nature with greenwashing – that is, pro-environmental messaging that serves to mask systemic unsustainability – can be traced at least as far back as 1971, to what is perhaps the Ur-moment of “ruining” the picture with trash. On the second annual Earth Day, an honorary and legally non-binding day declared after a decade of campaigning by the environmental movement, a now-infamous television ad was aired (). It begins with an apparently Native American man wearing braids and an eagle feather rowing a canoe through a “pristine” forest, only to emerge into an industrial landscape of shipping ports and smokestacks. As he pulls his canoe ashore, we viewers see that the landscape is littered in trash. The man walks until he comes to a busy road where, as he waits to cross, a passing driver throws a bag of half-eaten food which splatters at the man’s feet. The man looks up, the camera zooms into his face, and we see a single tear falling down his cheek. A voiceover then declares: “People start pollution. People can stop it.”

Figure 9. Still images from the 1971 television ad run by Keep America Beautiful. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j7OHG7tHrNM

The so-called “Crying Indian” ad achieved one of the highest viewer recognition rates in the history of American television, making billions of “household impressions” (Dunaway Citation2015, 79). The ad was funded by Keep America Beautiful (KAB), a political action committee founded in 1953 not by a confederation of environmental interests, but by bottle and can manufacturers as well as corporations like Coca-Cola who were invested in the development of disposable packaging for consumer products. These companies discovered that, rather than the longstanding system of returning empty containers for reuse at a bottling center, they could make a higher profit if consumers just threw their glass bottles or cans away; the only problem was that consumers tended to throw disposable containers in the surrounding environment, leading to legal efforts to restrict their production. KAB was tasked with forestalling such efforts to restrict the production of disposable containers, creating messaging that lay the blame for pollution not with industry and its reliance upon disposable containers, but with consumers who neglected to put their bottles in the bin (Rogers Citation2006).

The 1971 Earth Day ad represented a nascent template for greenwashing, in which pristine nature would (among its other meanings) come to index sustainability. The ad’s “crying” character played by a nonindigenous actor cited the 1960s countercultural interest in Native Americans, who in a renewal of Romantic/Transcendental sentiment were seen as being closer to “nature” and to stand in opposition to the toxic fruits of modernity – metonymized, in the ad, by the machinery of commerce and by trash. Wearing moccasins and paddling a canoe, the supposed Native American in the ad is little changed from the premodern figure imagined by Thomas Moran in The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone ((b)), at home in and indeed one with the “wilderness.” The imaginaries of the American environmental movement were thus enlisted in the ongoing campaign to convince consumers that their actions were responsible for pollution, establishing pristine nature as the obverse of trash.

Parallel to the semiotics of pristine nature, the anti-litter messaging of KAB was also a form of obfuscation: in turning the camera upon trash, attention was diverted from industry’s role in perpetuating pollution, sowing the notion that the environment could be protected if only consumers would behave themselves. Today, this dynamic remains in play, as global corporations continue efforts to disrupt the growing awareness that waste is a structural rather than an individual issue; such do we now find “recycle me” written on bottles and cans of Coca-Cola, even as the corporation produces more than 100 billion plastic bottles per year (Laville Citation2019). The anti-litter genre may indeed be culpable in perpetuating the narrative that “people cause pollution” rather than corporations, part of a broader lexicon of visual genres which “favor individual responses to environmental problems rather than those that call for major structural changes in terms of the way in which we organize our societies and the resource greedy nature of capitalism” (Hansen and Machin Citation2013, 157).

Yet anti-litter has a practical impact that cannot be dismissed, especially where littering remains an endemic issue – which tend to be places where recycling is not possible, and where the most accessible means of obtaining potable water is via plastic bottles. Oman is one such place, where the citational practices of local Instagram users show that semiotic genres can escape the context of their enregisterment.

“#KeepOmanBeautiful”: nature and the semiotics of sustainability

The semiotic entanglement of pristine nature and sustainability messaging is engaged in tour guide and blogger Ali Mohammedi’s Instagram Reel, which addresses the issue of seasonal litter in the southern Omani governorate of Dhofar (). The Reel begins with a self-in-nature composition of Ali himself gazing at a waterfall falling in multiple cascades over mossy rocks, before the scene cuts to a pan of the pool of deep aquamarine water and the tree-shaded cirque in which it nestles – a brief vision of untouched nature. Over the sound of rushing water, Ali’s voice then intercedes: “Beautiful, isn’t it? But look … ” The camera pans downward to reveal that, despite the apparently untouched scene before him, Ali is actually standing on rocks strewn with plastic bottles and wrappers. “Pretty, pretty please,” reads text that overlays the shots of litter, “#KeepOmanBeautiful [a]nd take your rubbish with you!”

In transitioning from the genres of the self-in-nature to untouched nature before invoking anti-litter, Ali’s Reel points to what is obscured in images of pristine nature. The Reel, he suggests, can be situated within the “Instagram vs. Reality” trend, but rather than pointing to the unmanicured experience of offline tourism, the trend highlights destructive impacts on the environment (private communication, 2023) – which, too often, take place offscreen. Instead, the Reel calls into question the certitude of pristine nature, almost as if to ask whether all images on Instagram were taken with the photographer angling the camera upwards away from trash. The question of whether the citation of anti-litter serves to mask systemic unsustainability is answered by the social and political-economic circumstances in which it is invoked: in a region where tourism is increasing, and plastic bottles and other disposable packaging are an inescapable feature of everyday life, the message of Don’t litter addresses an immediate environmental issue. What is more, in Oman and other Gulf countries, using social media to mount a structural critique is complicated if not dangerous; the oil-producing Gulf benefits economically from the production of plastic, and criticism of the government is prohibited. The leveraging of pristine nature can thus be seen as a sound political negotiation, in addition to a mechanism for raising awareness.

Of course, the citation of anti-litter and pristine nature may be read with skepticism. One may ask whether the anti-litter genre does not in fact further inscribe the unrealistic ideals of pristine nature; a trash-less view is, as the semiotic genealogy traced in previous sections indicates, most often moulded in the shape of pristine nature. In terms of broader campaigns for sustainability, pristine nature is largely irrelevant, if not even a hindrance. Images of untouched landscapes hide not only humans, but also the Anthropocenic character of landscapes: increasingly, blue skies are saturated with carbon dioxide, rushing water diluted with microplastics, and droughts entrenched by rising temperatures. The problematics of capturing climate change and biodiversity loss in images is, perhaps, not just a question for social media users but one for semioticians more broadly. We can describe the semiotics of pristine nature, but these are not a semiotics of the Anthropocene.

However, a semiotics which grapples with structural unsustainability and the accelerating impacts of climate change seems likely to emerge somewhere along the confluence of everyday bids for change and social media. Users of platforms like Instagram and TikTok (among others) creatively engage environmental issues through visual signs, making meaning by citing enregistered genres in recombined and emergent forms. Such citations do not reference the earliest enregistered forms – that is, the colonial and corporate aesthetics of pristine nature and anti-litter. Rather, these recombined citations may be considered diffuse, a discourse act in which the “original” source of enregisterment is neither explicit nor intentional (Smith, Järlehed, and Jaworski Citation2023, 28). As a sign’s semiotic chain lengthens over the years and across the globe, individual acts of citation are just as – if not more – beholden more to the circumstances of context than to the history of enregisterment. In this sense, a semiotics of sustainability may repurpose pristine nature even as new signs and genres take shape.

The dialectics of anti-litter and pristine nature in Oman, then, may represent one of countless sources from which a semiotics of sustainability is germinating. Responding to an issue deemed urgent by the local community, and operating within unique political-economic constraints, users are creatively appropriating global genres in a context where sociocultural relations with the environment are undergoing rapid change largely due to social media and the rise of nature tourism. Even as global ways of seeing nature become established, the appropriation of anti-litter might represent something else – exemplified, perhaps, by the vignette at this article’s introduction (). Where I saw a “natural” view from the perspective of a tourist and unconsciously reproduced a vision of “untouched” nature, many people living in Oman do not point the camera away from trash. Instead, they seek to “keep” their home beautiful, exposing unsustainable practices and urging a responsibility to the land from which they – unlike tourists – will not walk away.

Conclusion

Trash “ruins” a picture by disrupting a semiotic regime of “pristine nature,” serving as a metonym of human impact upon an environment that is imagined to otherwise exist in an “untouched” state. Informed by fieldwork in Oman, this article traces the history and contemporary citation of pristine nature in two genres, “untouched nature” and the “self-in-nature,” before considering how these genres are in dialogue with “anti-litter,” a third genre in which improperly-discarded waste is depicted in a tactical plea for environmentally-conscientious behavior. Next to highlighting the constructedness of these genres, this study of the semiotics of pristine nature might encourage a recognition of its artistic, if not fictional attributes. While reflecting and perhaps even perpetuating nature/society dualism, social media posts nonetheless celebrate a relationship with the more-than-human world, which more and more people around the world are developing through nature tourism.

By contrast, the application of pristine nature in advertising or in sustainability claims ought to inspire doubt, if it does not outright reveal ulterior motives of distracting from unsustainable systems and processes. While both anti-litter and pristine nature are regularly collocated with depictions of sustainability, historical genealogies indicate that the process through which each genre was enregistered was mobilized by colonial hierarchies in the conquest of land and by corporations in the interest of securing acceptance for unsustainable systems of disposability, and in institutional contexts this history is immanent. When individual social media users cites these genres they do not necessarily re-inscribe ideologies of capture and extraction, although this history should underscore the importance of citational context. Such do social media users in Oman tackle littering through a semiotics of diffuse citation, in which anti-litter posts emerge as effective tools for responding to an urgent environmental issue. Whether it be anti-litter or pristine nature, the enregistered signifiers of these genres are idiosyncratically adapted and repurposed through the citational practices of individuals and communities.

These semiotic regimes are not fixed, however. In revealing the contingency of signs, an historical perspective also encourages innovation – an urgent task for developing a semiotics of sustainability. If pristine nature occludes the extent of human impact upon the environment, and anti-litter focuses upon unsustainable acts by individuals, how can (un)sustainability be more rigorously visualized? What Peeples (Citation2011) describes as the “toxic sublime” is one genre that reveals pollution to be a structural issue, when sensorially overwhelming images of toxified landscapes forced viewers to reckon with the destructive impacts of human industry. Then there is “solarpunk” art and media, in which urbanized human societies are visually imagined to exist in utopian coexistence with nature. Yet if one does not make art or behold a toxic landscape, it is unclear how these genres may be made legible through citational practices in such spaces as social media. Future research would do well to focus on the development of visual genres that grapple with structural unsustainability and climate change, whether by appropriating established semiotic regimes or by evolving new canons of use.

Acknowledgements

I am immensely grateful to everyone in Oman who have so generously shared their time and insights with me, with special thanks to Abdullah Alhadidi, Faisal Al Hooti, Qasim Al Naabi, Ahmed Al Nairi, Haitham Al Shaaibi, Rumpa Mitra, Ali Mohammedi, and the scuba diver for kindly contributing their photos and Reels. This article also benefited from the excellent feedback of my colleagues at Tilburg’s Department of Culture Studies, in addition to Maida Kosatica and colleagues at the University of Duisburg-Essen. All errors and inaccuracies are my own.

Notes

1 This project was approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Committee at KU Leuven, file #G-2021-4251-R2(MAR), and the Research Ethics and Data Management Committee at Tilburg University, file #REDC2023.60.

2 Caspar David Friedrich’s Riesengebirge (1830-35) notably predates Church’s Twilight.

References

- Agha, Asif. 2006. Language and Social Relations. Vol. 24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Alexander, Catherine, and Patrick O’Hare. 2020. “Waste and Its Disguises: Technologies of (Un) Knowing.” Ethnos, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2020.1796734.

- Alhinai, Maryam, and Tema Milstein. 2019. “From Kin to Commodity: Ecocultural Relations in Transition in Oman.” Local Environment 24 (12): 1078–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1672635.

- Bakhtin, M. M. 2014. “The Problem of Speech Genres.” In The Discourse Reader, edited by Adam Jaworski and Nikolas Coupland, 73–82. London: Routledge. Original edition, 1986.

- Bauman, Richard, and Charles Briggs. 1990. “Poetics and Performances as Critical Perspectives on Language and Social Life.” Annual Review of Anthropology 19 (1): 59–88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2155959.

- Berger, John. 2008. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books. Original edition, 1972.

- Bordo, Jonathan. 2002. “Picture and Witness at the Site of the Wilderness.” In Landscape and Power, edited by W. J. T. Mitchell, 291–315. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

- boyd, danah. 2010. “Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics, and Implications.” In A Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network sites, edited by Zizi Papacharissi, 47–66. New York: Routledge.

- Brady, Emily. 2003. Aesthetics of the Natural Environment. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Bucher, Taina, and Anne Helmond. 2017. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, edited by Jean Burgess, Thomas Poell, and Alice Marwick, 233–253. London and New York: SAGE.

- Burke, Edmund. (1757) 1958. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Castree, Noel. 2013. Making Sense of Nature. London: Routledge.

- Cosgrove, Denis E. 1998. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Cronon, William. 1996. “The Trouble with Wilderness: or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Environmental History 1 (1): 7–28.

- Deckard, Sharae. 2009. Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden. New York: Routledge.

- DeLuca, Kevin Michael, and Anne Teresa Demo. 2000. “Imaging Nature: Watkins, Yosemite, and the Birth of Environmentalism.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 17 (3): 241–260.

- Denevan, William M. 1992. “The Pristine Myth: The Landscape of the Americas in 1492.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 82 (3): 369–385.

- Dresner, Simon. 2008. The Principles of Sustainability. 2nd ed. London: Earthscan. Original edition, 2002.

- Dunaway, Finis. 2015. Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fälton, Emelie. 2024. “The Romantic Tourist Gaze on Swedish National Parks: Tracing Ways of Seeing the Non-Human World Through Representations in Tourists’ Instagram Posts.” Tourism Recreation Research 49 (2): 235–238.

- Goodland, Robert. 1995. “The Concept of Environmental Sustainability.” Annual Review of Ecological Systems 26: 1–24.

- Grove, Richard H. 1995. Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hansen, Anders. 2018. Environment, Media and Communication. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Hansen, Anders, and David Machin. 2013. “Researching Visual Environmental Communication.” Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture 7 (2): 151–168.

- Hawkins, Gay. 2006. The Ethics of Waste: How We Relate to Rubbish. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Howlett, Michael, and Rebecca Raglon. 1992. “Constructing the Environmental Spectacle: Green Advertisements and the Greening of the Corporate Image, 1910–1990.” Environmental History Review 16 (4): 53–68.

- Implementation Support and Follow-up Unit. 2022. Vision Document. Muscat: Implementation Support and Follow-up Unit.

- Kosatica, Maida. 2024. “Semiotic Landscape in a Green Capital: The Political Economy of Sustainability and Environment.” Linguistic Landscape 10 (2): 136–165.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2021. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Lamb, Gavin. 2021. “Spectacular Sea Turtles: Circuits of a Wildlife Ecotourism Discourse in Hawai‘i.” Applied Linguistics Review 12 (1): 93–121.

- Latiri, Lamia. 2001. “The Meaning of Landscape in Classical Arabo-Muslim Culture.” Cybero: European Journal of Geography 196: 1–17.

- Laville, Sandra. 2019. “Coca-Cola Admits It Produces 3m Tonnes of Plastic Packaging a Year.” The Guardian, 14 March 2019. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/mar/14/coca-cola-admits-it-produces-3m-tonnes-of-plastic-packaging-a-year.

- Lecompte, Margaret D., and Jean J. Schensul. 2013. Analysis and Interpretation of Ethnographic Data: A Mixed Methods Approach. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

- Ledin, Per, and David Machin. 2018. Doing Visual Analysis: From Theory to Practice. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Machin, David, and Yueyue Liu. 2023. “How Tick List Sustainability Distracts from Actual Sustainable Action: The UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” Critical Discourse Studies 21 (2): 164–181.

- Milanesi, Matilde, Yuliia Kyrdoda, and Andrea Runfola. 2022. “How Do You Depict Sustainability? An Analysis of Images Posted on Instagram by Sustainable Fashion Companies.” Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 13 (2): 101–115.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 2002. “Imperial Landscape.” In Landscape and Power, edited by W. J. Thomas Mitchell, 5–34. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Nakassis, Constantine V. 2013. “Citation and Citationality.” Signs and Society 1 (1): 51–77.

- Nash, Roderick Frazier. 2001. Wilderness & the American Mind. New Haven: Yale University Press. Original edition, 1967.

- Nicolson, Marjorie Hope. 1997. Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Osborne, Peter D. 2000. Travelling Light: Photography, Travel and Visual Culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Parguel, Béatrice, Florence Benoit-Moreau, and Cristel Antonia Russell. 2015. “Can Evoking Nature in Advertising Mislead Consumers? The Power of ‘Executional Greenwashing’.” International Journal of Advertising 34 (1): 107–134.

- Peeples, Jennifer. 2011. “Toxic Sublime: Imaging Contaminated Landscapes.” Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture 5 (4): 373–392.

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge.

- The Qur’an. Translated by M. A. S. Abdel Haleem. 2010. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rogers, Heather. 2006. Gone Tomorrow: The Hidden Life of Garbage. New York, London: The New Press.

- Silverstein, Michael. 2005. “Axes of Evals: Token versus Type Interdiscursivity.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15 (1): 6–22.

- Smith, Sean P. 2021. “Landscapes for “Likes”: Capitalizing on Travel with Instagram.” Social Semiotics 31 (4): 604–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2019.1664579.

- Smith, Sean P., Johan Järlehed, and Adam Jaworski. 2023. “HOLLYWOOD: The Political Economy and Global Citation of an Emblematic Language Object.” Language in Society, 1–32, Online First.

- Taylor, Dorceta. 2016. The Rise of the American Conservation Movement. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Thurlow, Crispin. 2022. “Rubbish? Envisioning a Sociolinguistics of Waste.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 26 (3): 386–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12559.

- Thurlow, Crispin, and Adam Jaworski. 2010. “Silence is Golden: The ‘Anti-communicational’ Linguascaping of Super-Elite Mobility.” In Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space, edited by Adam Jaworski and Crispin Thurlow, 187–218. London: A&C Black.

- Thurlow, Crispin, and Adam Jaworski. 2014. “‘Two Hundred Ninety-Four’: Remediation and Multimodal Performance in Tourist Placemaking.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 18 (4): 459–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12090.

- Thurlow, Crispin, Alessandro Pellanda, and Laura Wohlgemuth. 2022. “The Discursive Chronotopes of Waste: Temporal Laminations and Linguistic Hauntings.” Language in Society 51 (5): 819–837. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404522000616.

- Urry, John. 1992. “The Tourist Gaze and the ‘Environment’.” Theory, Culture & Society 9 (3): 1–26.

- Urry, John, and Jonas Larsen. 2011. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Williams, Raymond. 1973. The Country and the City. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, Adam. 2022. “The Force of Nature: The Semiotic Foregrounding of Nature in Post- Lockdown Tourist Place Branding in Rural Alsace.” Sociolinguistic Studies 16 (4): 525–545.

- Zappavigna, Michele, and J. R. Martin. 2018. “#Communing Affiliation: Social Tagging as a Resource for Aligning Around Values in Social Media.” Discourse, Context & Media 22: 4–12.