?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In this meta-analysis, we examined the quantitative relation between meat consumption or avoidance, depression, and anxiety. In June 2020, we searched five online databases for primary studies examining differences in depression and anxiety between meat abstainers and meat consumers that offered a clear (dichotomous) distinction between these groups. Twenty studies met the selection criteria representing 171,802 participants with 157,778 meat consumers and 13,259 meat abstainers. We calculated the magnitude of the effect between meat consumers and meat abstainers with bias correction (Hedges’s g effect size) where higher and positive scores reflect better outcomes for meat consumers. Meat consumption was associated with lower depression (Hedges’s g = 0.216, 95% CI [0.14 to 0.30], p < .001) and lower anxiety (g = 0.17, 95% CI [0.03 to 0.31], p = .02) compared to meat abstention. Compared to vegans, meat consumers experienced both lower depression (g = 0.26, 95% CI [0.01 to 0.51], p = .041) and anxiety (g = 0.15, 95% CI [-0.40 to 0.69], p = .598). Sex did not modify these relations. Study quality explained 58% and 76% of between-studies heterogeneity in depression and anxiety, respectively. The analysis also showed that the more rigorous the study, the more positive and consistent the relation between meat consumption and better mental health. The current body of evidence precludes causal and temporal inferences.

Many have unskillfully written upon the preservation of health; particularly by attributing too much to the choice, and too little to the quality of meats.

Francis Bacon

Introduction

In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that mental illness was the leading cause of disability worldwide (World Health Organization Citation2017). They estimated that over 300 million people suffer from depression and over 260 million people suffer from anxiety (Friedrich Citation2017; Kessler et al. Citation2005). These estimates reflect a substantial increase in the number of people living with mental disorders over the past two decades (Vos et al. Citation2015; World Health Organization Citation2017). Given that dietary intake is considered a major contributor to mental health, it is important to provide rigorous quantitative evidence on diet—mental health relations to inform both public policy and clinical practice.

In parallel with increments in mental disorders, vegetarianism and veganism (i.e., avoidance of meat or all animal products, respectively) have become more popular and prevalent worldwide. The drivers of these corresponding trends are varied and include ethical, environmental, and animal rights-related reasons, (Kerschke-Risch Citation2015; Kerschke-Risch Citation2016; Rosenfeld Citation2019; Whorton Citation1994) as well as attempts to treat or ameliorate mental illnesses via dietary restrictions. As a result, the question of whether meat consumption or avoidance is associated with better mental health has become a controversial issue in public health and nutrition science (Jacka et al. Citation2012; Mofrad et al. Citation2021; Zeraatkar et al. Citation2019).

To date, the research has been equivocal and our recent systematic review summarized these findings (Dobersek et al., Citation2020). Briefly, we found that the majority of studies showed that meat abstainers (vegetarians and vegans) had substantially higher rates or risk of depression, anxiety, and/or self-harm (e.g., suicide) (Baines, Powers, and Brown Citation2007; Hibbeln et al. Citation2018; Matta et al. Citation2018; Michalak, Zhang, and Jacobi Citation2012). Additionally, these groups were more likely to be prescribed medication for mental-health issues (Baines, Powers, and Brown Citation2007). However, some studies suggested the opposite conclusion (Beezhold et al. Citation2015; Beezhold, Johnston, and Daigle Citation2010), and the findings regarding other less clearly defined concepts (e.g., mood states, affective well-being, stress perception, quality of life) were less obvious (Beezhold et al. Citation2015; Beezhold and Johnston Citation2012; Beezhold, Johnston, and Daigle Citation2010; Boldt et al. Citation2018; Pfeiler and Egloff Citation2018; Wirnitzer et al., 2018).

Our analysis showed that these contradictory findings were engendered by numerous factors (Dobersek et al., Citation2020). These included the inconsistent categorization of vegans and vegetarians, poor operationalization of psychological outcomes, biased recruitment and sampling strategies (Beezhold and Johnston Citation2012; Beezhold, Johnston, and Daigle Citation2010; Lindeman Citation2002; Perry et al. Citation2001; Timko, Hormes, and Chubski Citation2012), invalid dietary assessment protocols (e.g., food frequency questionnaires, FFQs) (Archer, Pavela, and Lavie Citation2015; Archer, Hand, and Blair Citation2013; Archer, Lavie, and Hill Citation2018a; Archer, Marlow, and Lavie Citation2018b, Citation2018c), and statistical and communication errors (e.g., failure to correct for multiple comparisons, inappropriate use of causal language). In summary, study rigor and quality appeared to be the greatest generator of inconsistent findings (Dobersek et al., Citation2020).

While our systematic review (Dobersek et al. Citation2020) provided rigorous evidence suggesting that meat consumers had lower rates or prevalence of mental health issues, we did not examine the strength of this relation. Therefore, the purpose of this meta-analytic review was twofold. First, to provide a comprehensive assessment of the quantitative relation between meat consumption or avoidance and mental health, and second, to examine the effect of study quality on this relationship. To avoid inconsistent definitions of meat abstention, we captured only studies that offered a clear dichotomy between individuals who reported consuming meat (i.e., omnivores) and those who reported to be meat abstainers (i.e., vegans, vegetarians). Our focus was limited to the two most prevalent mental-health outcomes worldwide: depression and anxiety.

Methods

Search strategy

The search strategy was adopted from our previous systematic review (Dobersek et al. Citation2020) and updated to include all papers published through June 18th, 2020. Five online databases (i.e., PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, Medline with full text, and Cochrane Library) were searched using a broad set of keywords for primary research examining depression and anxiety in meat consumers and meat abstainers. Supplemental File 1 provides details of the search terms and strategy. Two teams of two persons independently conducted the searches and imported them into reference-managing software (EndNote X9, Citation2019). After excluding duplicate articles, both teams independently identified potentially relevant articles by screening their titles and abstracts. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were then assessed by both teams and the lead investigator (UD) working independently. Reference lists from previous reviews and research papers were also examined. The teams and lead investigator then met to arrive at a consensus on the inclusion/exclusion criteria for each paper (e.g., depression/anxiety, strict definitions of dietary intake, etc.). Disputes were adjudicated by discussion, with the final decision made by the lead investigator. Consensus was obtained for all included articles.

Study inclusion criteria

The studies were included if 1) they were written in English, 2) the authors provided a clear distinction between participants who reported eating meat (i.e., meat consumers; e.g., omnivores) and those who avoided meat consumption (i.e., meat abstainers; e.g., vegans, vegetarians), 3) they included depression and/or anxiety as psychological outcomes, and 4) they provided enough statistical information to calculate the effect sizes (ESs). No design, geographical, cultural, or time-period (publication-date) restrictions were set.

Study exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they 1) were written in a non-English language, 2) did not assess depression or anxiety, 3) did not provide (or we were unable to acquire) information needed to calculate ESs, and 4) examined meat consumption as a continuous or multi-level variable. This latter focus was necessary for the following reasons. The use of self-reported (memory-based) dietary assessments (FFQ) induces nonquantifiable measurement error due to intentional and/or non-intentional misreporting and the invalidity of pseudo-quantification (assigning nutrient and caloric values to memories of consumed foods and beverages) (Archer, Lavie, and Hill Citation2018a; Archer, Marlow, and Lavie Citation2018b; Archer, Pavela, and Lavie Citation2015). This nonquantifiable error precludes examining meat consumption as a continuous variable. Therefore, by examining meat consumption as a dichotomous (yes/no) variable, we potentially eliminated the nonquantifiable error and the error propagated via pseudo-quantification.

provides the detailed description of inclusion/exclusion criteria according to a Population, Exposure/Intervention/Comparison, Outcomes, and Study Design (PE/I/COS) framework (Brown et al. Citation2006; Huang, Lin, and Demner-Fushman Citation2006).

Table 1. Detailed description of selection criteria according to the PE/I/COS Framework (Brown et al. Citation2006; Huang, Lin, and Demner-Fushman Citation2006).

Data extraction

Qualitative and quantitative data extraction were performed independently by both teams and overseen by the lead investigator. The information extracted from each study included overall design, participant characteristics (e.g., population, sample size, age), assessment methods for depression, anxiety, and diet, the definitions of meat consumers/abstainers, time of dietary assessment/diet adoption, factors adjusted for in the analyses, key findings, and relevant data to calculate the ESs (e.g., means, standard deviations, proportions, standard errors, p-values). The reviewers were not blinded and had full access to paper details (e.g., authors, affiliations, and journals) during data extraction and compilation. The extraction tables were examined for accuracy and completeness by the lead investigator. Once compiled, information from the selected studies was transferred to a ‘Summary Table’ ().

Table 2. A summary of extracted participant and study characteristics included in the meta-analysis in alphabetical order.

Study quality and risk of bias assessment

Each study included in our meta-analysis was assessed for methodologic rigor via quantitative analyses of the study quality. An outside investigator – an expert in obesity, nutrition, and epidemiological science – and the lead investigator worked independently while employing a 100-point scale of predetermined criteria that was developed for our previously published systematic review (Dobersek et al., Citation2020).

Specifically, each study was evaluated for design, sampling and recruitment, specification and analysis of outcome, and interpretation and communication of results (please see Supplemental File 2). For the interpretation purpose, the studies were categorized as high quality (scores 90–100), moderate quality (scores 60–89), moderate-to-low quality (scores 40–59), low quality (scores 20–39), and very low quality (scores 0–19).

The statistical method of estimation of effect sizes and analyses

The statistical techniques to compute the ESs were adopted from Borenstein and colleagues (Borenstein et al. Citation2011; Borenstein, Rothstein, and Cohen Citation2005). We calculated the magnitude of the effect (i.e., effect size) from the d family: ESs or standardized mean differences between meat consumers and meat abstainers on depression and anxiety. Specifically, for study i we computed

where

is the mean score on depression or anxiety for meat abstainers,

is the analogous mean for meat consumers, and

is the weighted pooled standard deviation across the two groups. Because both outcomes have negative valences, higher scores reflect more negative outcomes; negative di values thus reflect poorer outcomes for meat consumers and more favorable outcomes for meat abstainers. Conversely, positive di values reflect better outcomes for meat consumers. If means and standard deviations were not available, we used other statistics (e.g., standard errors, p or t values, proportions) and transformed the data into the d effect size using the appropriate formulas, or used the available data published with the articles, or contacted the authors for the relevant information. If the same type of outcome (e.g., anxiety) was assessed multiple times via different measures in the same study (e.g., DASS-A and POMS-A, SPAS and STAI), we calculated the simple average of the effect sizes and adjusted the variance using the formula below to address the problem of non-independent information (Gleser and Olkin Citation2009):

where viis the variance of di and

Additionally, given that Cohen’s d tends to overestimate the effects, we used Hedges’s g effect size (i.e., a quantitative measure of the magnitude between meat abstainers and meat consumers) with bias correction (Hedges Citation1981; Hedges and Olkin Citation1985). All ESs were interpreted according to Cohen’s rules of thumb, with an ES of 0.20 indicating a small effect, 0.50 a medium effect, and > 0.80 a large effect (Cohen Citation1988). Confidence intervals (CIs) were all computed at the 95% level.

We performed a test of heterogeneity using the Cochran’s Q statistic (Hedges and Olkin Citation1985) to inform us about variation in ESs, and used the I2 statistic to examine what proportion of the observed variance reflected differences in true ESs rather than sampling error (Higgins and Thompson Citation2002; Huedo-Medina et al. Citation2006). Given that studies included in our meta-analysis were gathered from the published literature and are potentially based on multiple populations, we used a random-effects model as the pooling method (Borenstein Citation2019; Borenstein et al. Citation2011; Higgins and Thompson Citation2004). Publication bias was assessed by inspection of the funnel plot, Egger linear regression test, and Begg rank correlation test (Begg and Mazumdar Citation1994; Egger et al. Citation1997). To provide a graphical overview of the ESs for each study, we constructed forest plots.

We examined the differences between meat abstainers or vegans and meat consumers on depression and anxiety separately. To estimate potential differences between the groups, we conducted a subgroup analysis by sex. Additionally, a univariate meta-regression using the restricted maximum likelihood estimator (Dempster, Rubin, and Tsutakawa Citation1981) for between-studies variation with the Knapp-Hartung adjustment (Hartung and Knapp Citation2001) was used to explore potential sources of heterogeneity using a study quality as covariate (Higgins and Thompson Citation2004). Finally, we performed a cumulative meta-analysis to examine the impact of individual studies on the results. Studies were added sequentially to a random-effects model using the continuous study quality score (ordered from highest to the lowest quality). All ESs and analyses were calculated and performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis program Version 3.0. (Borenstein, Rothstein, and Cohen Citation2005). A p-value less than .05 was considered significant for all tests.

Results

Literature search and characteristics of included studies

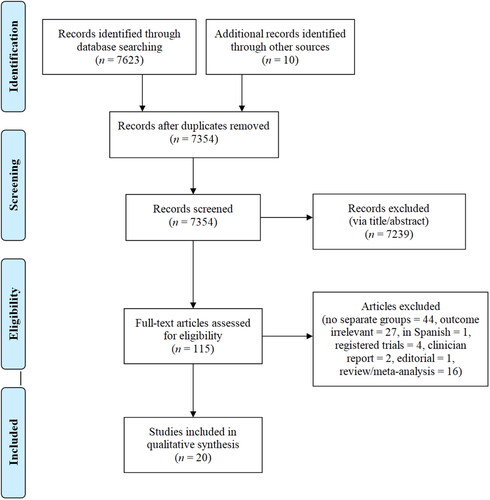

Our initial search resulted in 7623 potentially relevant articles. After removing duplicates, we screened titles and abstracts of 7354 papers for inclusion/exclusion criteria. This resulted in 115 full-text articles which were read fully and critically assessed. This qualitative screening resulted in 20 papers published from 2001 to April 2020 that met our inclusion/exclusion criteria. These included 17 cross-sectional, 2 mixed cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, and 1 RCT. The total sample included 171,802 participants (93,257 females and 77,410 males) with 157,778 meat consumers and 13,259 meat abstainers. Three studies included only females (Baines, Powers, and Brown Citation2007; Lindeman Citation2002; Stokes, Gordon, and DiVasta Citation2011) and one study included only males (Hibbeln et al. Citation2018). Eight studies included samples from the U.S. or North America (Beezhold et al. Citation2015; Beezhold and Johnston Citation2012; Beezhold, Johnston, and Daigle Citation2010; Forestell and Nezlek Citation2018; Jin et al. Citation2021; Perry et al. Citation2001; Stokes, Gordon, and DiVasta Citation2011; Timko, Hormes, and Chubski Citation2012), eleven were from non-U.S. countries (e.g., Europe, Asia, and Oceania) (Baines, Powers, and Brown Citation2007; Baş, Karabudak, and Kiziltan Citation2005; Goh et al. Citation2019; Hessler-Kaufmann et al. Citation2020; Hibbeln et al. Citation2018; Kapoor et al. Citation2017; Lindeman Citation2002; Matta et al. Citation2018; Michalak, Zhang, and Jacobi Citation2012; Paslakis et al. Citation2020; Velten et al. Citation2018), and one study included samples from multinational-cohorts (Lavallee et al. Citation2019). The sample sizes ranged from 38 to 90,380 participants between 11 and 105 years of age.

To assess mental health, one study used diagnostic interviews (Michalak, Zhang, and Jacobi Citation2012) and one used doctors’ diagnoses and prescription medications (Baines, Powers, and Brown Citation2007). The rest used self-reported questionnaires (e.g., DASS, POMS, SPAS, STAI, etc.) (Baş, Karabudak, and Kiziltan Citation2005; Beezhold et al. Citation2015; Beezhold and Johnston Citation2012; Beezhold, Johnston, and Daigle Citation2010; Forestell and Nezlek Citation2018; Goh et al. Citation2019; Hessler-Kaufmann et al. Citation2020; Hibbeln et al. Citation2018; Jin et al. Citation2021; Kapoor et al. Citation2017; Lavallee et al. Citation2019; Lindeman Citation2002; Matta et al. Citation2018; Paslakis et al. Citation2020; Perry et al. Citation2001; Stokes, Gordon, and DiVasta Citation2011; Timko, Hormes, and Chubski Citation2012; Velten et al. Citation2018). The studies used a variety of self-reported FFQs to assess dietary intake. reports details on participants and study characteristics. As per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) (Moher et al. Citation2009), results from each stage of the search are displayed in .

Methodologic quality analysis

The studies ranged from very low (7.5) to high quality (100) with a mean score of 52.5. For interpretation purposes, they were placed in five categories based on their methodologic quality score: 3 had very low quality (Beezhold et al. Citation2015; Beezhold and Johnston Citation2012; Stokes, Gordon, and DiVasta Citation2011), 5 had low quality (Beezhold, Johnston, and Daigle Citation2010; Goh et al. Citation2019; Hessler-Kaufmann et al. Citation2020; Jin et al. Citation2021; Lindeman Citation2002), 3 had moderate-to-low quality (Forestell and Nezlek Citation2018; Lavallee et al. Citation2019; Perry et al. Citation2001), 6 had moderate quality (Baş, Karabudak, and Kiziltan Citation2005; Hibbeln et al. Citation2018; Kapoor et al. Citation2017; Paslakis et al. Citation2020; Timko, Hormes, and Chubski Citation2012; Velten et al. Citation2018), and 3 had high quality (Baines, Powers, and Brown Citation2007; Matta et al. Citation2018; Michalak, Zhang, and Jacobi Citation2012). Inter-rater correlations between reviewers were very high (ICC = .979; 95% CI: .948-.992, p < .001). Several issues contributed to variation in study quality. Specifically, most studies used cross-sectional designs (n = 19), subjective and/or self-reported dietary (n = 19) and psychological assessment methods (n = 19), biased recruitment (n = 6), non-representative sampling (n = 11), and overinterpretated results (n = 9). For details regarding limitations, please see and our systematic review for a discussion on these issues (Dobersek et al., Citation2020).

Table 3. Major limitations and the number of studies associated with each.

Main findings

Depression and anxiety of meat abstainers and meat consumers

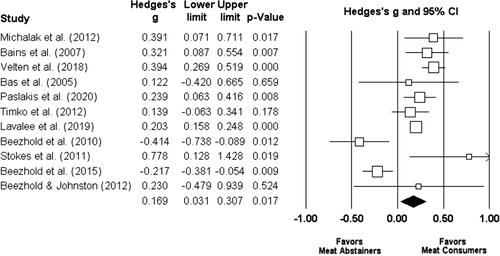

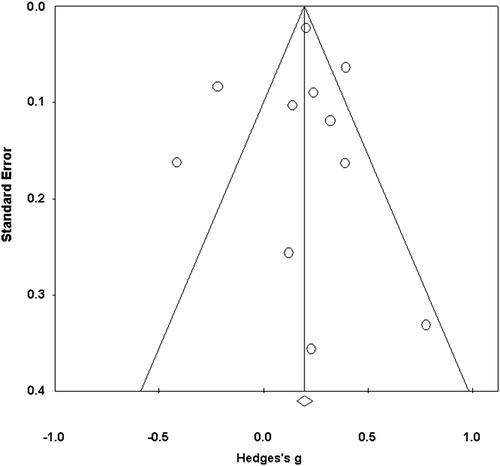

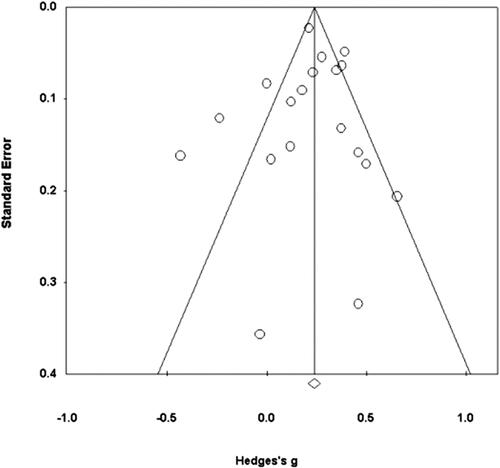

The analysis of 19 studies of depression showed a small but significant effect where meat abstainers had higher levels of depression than meat consumers (g = 0.216, 95% CI [0.14, 0.30], p < .001; 95% prediction interval [-0.09, 0.52]). shows the forest plot for the bias-corrected Hedges’s g values and their associated 95% CIs. Heterogeneity was significant and considerable [Q(18) = 74.01, p < .001; I2 = 75.68] and the funnel plot (), Egger’s linear-regression test (intercept = −0.31, t(17) = 0.41, 95% CI [-1.93, 1.31], p = .362), and Begg’s test (Kendall’s tau = −.094, p = .288) suggested no evidence of asymmetry of effects.

Figure 2. Forest plot for Hedges’s g and its associated 95% confidence interval (CI) for differences in depression between meat abstainers and meat consumers. Studies are arranged from high to low quality score.

Figure 3. Funnel plot of standard error and Hedges’s g for differences in depression between meat abstainers and meat consumers.

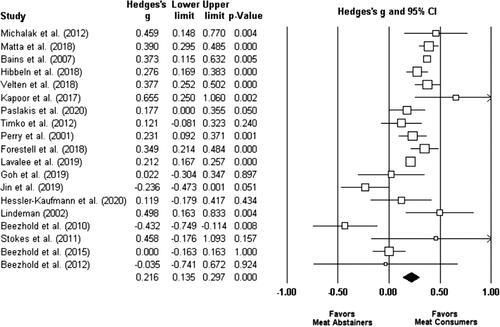

The analysis of 11 studies of anxiety showed a small significant effect where meat abstainers had higher levels of anxiety than meat consumers (g = 0.17, 95% CI [0.03, 0.31], p = .02; 95% prediction interval [-0.28, 0.62]). shows the forest plot for each bias-corrected Hedges’s g and its associated 95% CIs. Heterogeneity was again significant [Q(10) = 54.58, p < .001; I2 = 81.50] and the funnel plot (), Egger’s linear-regression test (intercept = − 0.28, t(9) = 0.26, 95% CI [-2.64, 2.08], p = .40), and Begg’s test (Kendall’s tau < .01, p = .50) suggested no evidence of publication bias.

Depression and anxiety of vegans and meat consumers

The analysis of 5 studies showed a small significant effect where vegans had higher depression levels than meat consumers (g = 0.26, 95% CI [0.01, 0.51], p = .041; 95% prediction interval [-0.62, 1.15]). Heterogeneity was significant [Q(4) = 17.02, p = .002, I2 = 76.50], and Egger’s linear regression test (intercept = 3.60, t(3) = 1.08, 95% CI [-6.97, 14.16], p = .18), and Begg’s test (Kendall’s tau = 0.30, p = .23) suggested no evidence of publication bias.

Our analysis of 3 studies showed a small non-significant effect between vegans and meat consumers on anxiety (g = 0.15, 95% CI [-0.40, 0.69], p = .598; 95% prediction interval [-6.64, 6.92]). Heterogeneity was again significant [Q(2) = 25.80, p < .01, I2 = 92.25], and Egger’s linear-regression test (intercept = 7.93, t(1) = 1.22, 95% CI [-74.72, 90.57], p = .219) and Begg’s test (Kendall’s tau < 0.001, p = .50) showed no evidence of publication bias. However, the small size of this set of studies makes generalization difficult.

Sex differences in contrasts of meat abstainers/vegan versus meat consumers on depression and anxiety

Sex did not modify the sizes of the differences between meat abstainers and meat consumers on depression, F(1, 22) = 1.34, p = .25, or anxiety, F(1, 11) = 0.77, p = .38. Also, no sex differences were detected in the comparisons of vegans versus meat consumers on depression, F(1, 6) = 0.62, p = .431, or anxiety, F(1, 2) = 0.80, p = .372.

Meta-regression and cumulative meta-analyses

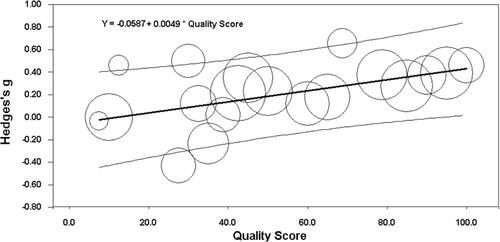

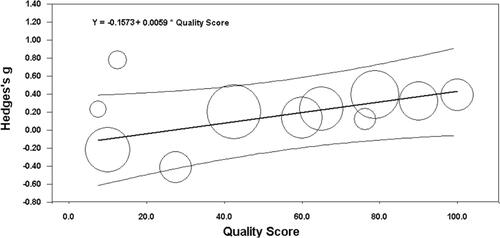

A random-effects univariate meta-regression analysis of 19 studies of depression showed that study quality (as a continuous variable) had a significant positive role in between-study heterogeneity, F(1, 17) = 8.46, beta coefficient = 0.005, p = .01, R2 = 0.58 (I2 = 61.88%, Q(17) = 44.59, p < .001). Similarly, a random-effects univariate meta-regression of 11 studies of anxiety suggested that study quality also had a significant positive impact on between-study heterogeneity, F(1, 9) = 6.68, beta coefficient = 0.006, p = .03, R2 = 0.76 (I2 = 67.17, Q(9) = 27.37, p = .001). In both cases significant residual variation was unexplained, per high I2 values. Please see and for the bubble plots for the relations between study quality, depression, and anxiety.

Figure 6. Bubble plot showing a regression line and prediction interval for study quality on depression between meat consumers and meat abstainers. Bubble size reflects within-study variance.

Figure 7. Bubble plot showing a regression line and prediction interval for study quality on anxiety between meat consumers and meat abstainers. Bubble size reflects within-study variance.

Our cumulative meta-analysis of depression demonstrated that moderate to high quality studies (Timko, Hormes, and Chubski Citation2012 though Michalak, Zhang, and Jacobi Citation2012 in Supplemental File 3, Figure 8) showed greater differences whereas moderate-low to very low-quality studies (Perry et al. Citation2001 through Beezhold and Johnston 2012) showed smaller differences between meat consumers and abstainers. A similar pattern was observed for anxiety, where studies of moderate to high quality (Timko, Hormes, and Chubski Citation2012 through Michalak, Zhang, and Jacobi Citation2012) demonstrated greater effect and studies with moderate-low to very low quality (Lavallee et al. Citation2019 through Beezhold and Johnston 2012) showed a smaller effect between meat consumers and meat abstainers (Supplemental File 3, Figure 9).

Descriptive analyses between effect sizes and study quality

To depict the relations between study quality and effect size, we created two figures (please see Supplemental File 4). It is important to note that for both depression and anxiety, all the higher quality studies favored meat consumers, whereas the relation was equivocal in the lower quality studies. Additionally, high quality studies included greater number of participants and were more homogenous compared to other studies. For details, please see Supplemental File 4.

Discussion

This meta-analysis extends the findings of our prior systematic review (Dobersek et al. Citation2020) by presenting a quantitative evaluation of the relation between meat consumption/abstention and mental health. It included 171,802 participants aged 11 to 105 years, from varied geographic regions, including Europe, Asia, North America, and Oceania. The findings show a significant association between meat consumption/abstention and depression and anxiety. Specifically, individuals who consumed meat had lower average depression and anxiety levels than meat abstainers. We also showed that vegans experienced greater levels of depression than meat consumers. Sex did not modify these relations. Study quality explained a significant proportion of between-studies heterogeneity and a cumulative meta-analysis confirmed these findings. Specifically, the higher the study quality, the more positive the benefit of meat consumption.

Our results may explain the equivocal nature of prior research. In contrast to our clear findings (both past (Dobersek et al. Citation2020 and present), other systematic reviews and meta-analytic results were inconsistent or contradictory. These equivocal results suggested that vegetarians, and in some cases vegans had lower levels of depression or anxiety (Askari et al. Citation2020; Iguacel et al. Citation2020; Lai et al. Citation2014; Li et al. Citation2017; Liu et al. Citation2016; Nucci et al. Citation2020; Zhang et al. Citation2017). As detailed in our systematic review (Dobersek et al. Citation2020), numerous factors explain these inconsistent conclusions. Briefly, most prior studies employed invalid or unreliable assessment protocols to measure exposures and outcomes (i.e., diet and mental health, respectively). For example, it is well established that dietary recalls and FFQs produce physiologically implausible and non-falsifiable (pseudo-scientific) data (Archer, Pavela, and Lavie Citation2015; Archer, Hand, and Blair Citation2013; Archer, Lavie, and Hill Citation2018a; Archer, Marlow, and Lavie Citation2018b, Citation2018c). Thus, the disparity between self-reported and actual dietary intake may render definitive conclusions impossible when analyzing meat consumption as a continuous rather than dichotomous variable (Archer, Pavela, and Lavie Citation2015; Archer, Hand, and Blair Citation2013; Archer, Lavie, and Hill Citation2018a; Archer, Marlow, and Lavie Citation2018b, Citation2018c).

With respect to mental health, the most rigorous research relied on physician-diagnosed disorders using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (Michalak, Zhang, and Jacobi Citation2012) (APA Citation2013) rather than self-reported (subjective) assessments with untested validity. The use of tools with questionable validity can lead to ambiguous findings and limited cross-study analyses.

Another major design error was the use of biased and selective sampling strategies. Several of the included studies recruited samples from vegan and vegetarian websites, social-networking groups, communities, and restaurants. We surmise this may have substantially biased data collection and may skew self-reported variables and findings if participants with a high degree of emotional or ideological commitment to their dietary behaviors intentionally or unconsciously misreport. An antecedent of this error may be a form of confirmation bias in which the flawed sampling confirms the investigators’ ideology or expectations rather than providing dispassionate data and results.

Finally, statistical and communication errors were ubiquitous. These included the failure to correct for multiple comparisons and the inappropriate use of causal language which can lead to invalid results, interpretations, and conclusions. In summary, given that these errors are widespread in the literature, valid conclusions from previous reviews that failed to examine study quality are not possible.

In the present meta-analysis, these errors taken together are related to significant between-studies variation in effect sizes. Study quality explained 58% and 76% of between-studies heterogeneity in the differences in depression and anxiety, respectively. Furthermore, our analyses (see Figures 2, 4, 6, 7, 10, and 11) demonstrated that higher quality studies showed a more positive and consistent relation between meat consumption and mental health. Higher quality studies had much larger sample sizes.

Finally, limited reporting of participant characteristics prevented an examination of several covariates (e.g., BMI, age of diet adoption/length of diet, clinical history, socioeconomic status, culture) that could potentially contribute to between-studies heterogeneity.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

This meta-analysis had several strengths. First, our a priori decision to select only studies that provided a clear dichotomy between meat consumers and meat abstainers allowed for a clear and rigorous assessment. While myriad studies have examined vegetarianism along a continuum, these were excluded because the lack of a clear distinction between groups rendered inferences equivocal. This distinction is necessary because self-reported (memory-based) dietary assessments (FFQ) should not be used for quantitative analyses because of their invalidity. Any study that attempts to use FFQs as continuous variables are invalid due to nonquantifiable measurement error (Archer, Lavie, and Hill Citation2018a; Archer, Marlow, and Lavie Citation2018b; Archer, Pavela, and Lavie Citation2015).

Second, we limited our psychological outcomes to the most prevalent and debilitative disorders: depression and anxiety. This allowed a focused yet rigorous analysis and ameliorated the effects of poorly operationalized psychological phenomena such as disordered eating, dietary restraint, orthorexia, and neuroticism. This exclusion helps to avoid potential misclassification and concomitant pathologizing of those who simply wish to avoid specific foods or food groups (e.g., vegans). Finally, with over 170,000 participants from several geographic regions, our meta-analysis allowed for more generalizable and definitive conclusions.

Limitations

Our meta-analysis also had limitations. First, we excluded non-English-language studies. This potentially biased our results in favor of ‘Western’ norms which include meat consumption. For example, we excluded papers published in languages other than English (e.g., Japanese, Hindi). Thus, we may have omitted studies from geographic regions that follow predominantly vegetarian or plant-based dietary patterns.

Second, while our search was clearly defined and comprehensive, our inclusion criteria excluded many publications that provided data on this topic (e.g., see (Anderson et al. Citation2019; Barthels, Meyer, and Pietrowsky Citation2018; Burkert et al. Citation2014; Cooper, Wise, and Mann Citation1985; Jacka et al. Citation2012; Larsson et al. Citation2002; Li et al. Citation2019; Northstone, Joinson, and Emmett Citation2018)). Specifically, these papers were excluded because they examined constructs other than depression or anxiety (e.g., orthorexia, restrained eating behavior) or assessed meat consumption as a continuous rather than dichotomous variable. As previously stated, self-reported dietary status and FFQs lead to nonquantifiable measurement error. Nevertheless, we think that our rigorous and highly focused meta-analysis has the potential to provide stronger evidence for the medical, research, and lay communities.

Third, despite the high confidence we place in our finding that meat abstention is linked to a greater prevalence of psychological disorders, study designs precluded inferences of temporality and causality. Specifically, only two of the included studies (Lavallee et al. Citation2019; Velten et al. Citation2018) provided information on temporality. Therefore, we were unable to conclusively examine this effect. Given that there are many reasons why people abstain from meat (e.g., ethical, environmental, animal rights-related reasons), this empirical question has not been adequately addressed. However, our previous systematic review (Dobersek et al. Citation2020) showed conflicting evidence on the temporal relations between meat abstention and depression and anxiety. Also, conclusions on causality require evidence from rigorous RCTs. Since only one low-quality RCT met our inclusion criteria (Beezhold and Johnston Citation2012), no conclusions regarding causality are supported.

Finally, the results of our meta-analysis are only as valid as the data collected in the included primary studies. Given that most studies used FFQs and self-reported questionnaires, participants may have been misclassified. Merely reporting that one avoids meat is not the equivalent of actual meat abstention (Archer, Pavela, and Lavie Citation2015; Archer, Hand, and Blair Citation2013; Archer, Lavie, and Hill Citation2018a; Archer, Marlow, and Lavie Citation2018b, Citation2018c). In fact, self-defined vegetarians and meat abstainers may consume meat (Haddad and Tanzman Citation2003).

Recommendations for future directions

Future investigators should avoid the most common flaws exhibited in the included studies. First, investigators must acknowledge and address the effects of both researcher and participant biases (e.g., confirmation bias, cognitive dissonance, observer-expectancy effects/reactivity) when employing highly selective or biased samples. Individuals who are highly invested in their dietary behaviors may be predisposed to intentional and non-intentional misreporting.

Second, the use of physician-diagnosed disorders based on criteria from the DSM-V (APA Citation2013; Michalak, Zhang, and Jacobi Citation2012) is preferable to self-reported symptoms, and assists in producing more definitive results. Additionally, the severe limitations and pseudo-scientific nature of self-reported dietary data and FFQs (Archer, Pavela, and Lavie Citation2015; Archer, Hand, and Blair Citation2013; Archer, Lavie, and Hill Citation2018a; Archer, Marlow, and Lavie Citation2018b, Citation2018c) could be overcome in part with point-of-purchase (barcode) data (Ng and Popkin Citation2012). However, while these data may be less biased, they are not necessarily an accurate proxy for actual dietary consumption.

Third, the use of more rigorous study designs (e.g., RCTs) is desirable over mere observational investigations. However, it would be extremely difficult to conduct a randomized study of diets with a long enough duration to impact fundamental affective outcomes such as anxiety and depression. Furthermore, detailed participant information regarding behavioral and health-related histories and current lifestyles is essential to valid interpretation and conclusions. Finally, studies should provide complete statistical information that allow for the calculations of effect sizes. More complete reporting would enable meta-analysts to extract both effect measures and study characteristics thus allowing for exploration of potentially important but unanswered questions (e.g., how is time of diet adoption related to mental health?).

Conclusion

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to extend our previous systematic review (Dobersek et al. Citation2020) and provide quantitative evidence to inform clinicians, policy-makers, and future research. Our results show that meat abstention (vegetarianism or veganism) is clearly associated with poorer mental health, specifically higher levels of both depression and anxiety. Our cumulative analyses suggest that the more rigorous the study, the stronger the relation between meat abstention and mental illness. However, the current body of evidence preludes temporal and causal inferences, and none should be inferred.

Conceptualization: UD; Methodology: all authors; Formal analysis and investigation: all authors; Writing-original draft preparation: UD; Writing-review and editing: all authors; Funding acquisition: UD; Supervision: UD,

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (330.7 KB)Disclosure statement

UD, SA, JA, and GW have previously received funding from the Beef Checkoff, through the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

Data availability

Data are available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, E. C., J. Wormwood, L. F. Barrett, and K. S. Quigley. 2019. Vegetarians’ and omnivores’ affective and physiological responses to images of food. Food Quality and Preference 71:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.06.008.

- APA, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Archer, E., C. J. Lavie, and J. O. Hill. 2018a. The failure to measure dietary intake engendered a fictional discourse on diet-disease relations. Frontiers in Nutrition 5:105. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00105.

- Archer, E., M. L. Marlow, and C. J. Lavie. 2018b. Controversy and debate: Memory-Based Methods Paper 1: The fatal flaws of food frequency questionnaires and other memory-based dietary assessment methods. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 104:113–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.08.003.

- Archer, E., G. A. Hand, and S. N. Blair. 2013. Validity of US nutritional surveillance: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey caloric energy intake data, 1971–2010. PLoS One 8 (10):e76632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076632.

- Archer, E., G. Pavela, and C. J. Lavie. 2015. The inadmissibility of what we eat in America and NHANES dietary data in nutrition and obesity research and the scientific formulation of national dietary guidelines. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 90 (7):911–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.009.

- Askari, M., E. Daneshzad, M. Darooghegi Mofrad, N. Bellissimo, K. Suitor, and L. Azadbakht. 2020. Vegetarian diet and the risk of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 4:1–11.

- Archer, E., M. L. Marlow, and C. J. Lavie. 2018c. Controversy and debate: Memory based methods paper 3: Nutrition’s ‘Black Swans’: Our reply. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 104:130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.07.013.

- Baines, S., J. Powers, and W. J. Brown. 2007. How does the health and well-being of young Australian vegetarian and semi-vegetarian women compare with non-vegetarians?Public Health Nutrition 10 (5):436–42. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007217938.

- Barthels, F., F. Meyer, and R. Pietrowsky. 2018. Orthorexic and restrained eating behaviour in vegans, vegetarians, and individuals on a diet. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 23 (2):159–66. doi: 10.1007/s40519-018-0479-0.

- Baş, M., E. Karabudak, and G. Kiziltan. 2005. Vegetarianism and eating disorders: Association between eating attitudes and other psychological factors among Turkish adolescents. Appetite 44 (3):309–15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.02.002.

- Beezhold, B. L., and C. S. Johnston. 2012. Restriction of meat, fish, and poultry in omnivores improves mood: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Nutrition Journal 11:9.

- Beezhold, B. L., C. S. Johnston, and D. R. Daigle. 2010. Vegetarian diets are associated with healthy mood states: A cross-sectional study in seventh day adventist adults. Nutrition Journal 9 (1):7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-26.

- Beezhold, B., C. Radnitz, A. Rinne, and J. DiMatteo. 2015. Vegans report less stress and anxiety than omnivores. Nutritional Neuroscience 18 (7):289–96. doi: 10.1179/1476830514Y.0000000164.

- Begg, C. B., and M. Mazumdar. 1994. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50 (4):1088–101. doi: 10.2307/2533446.

- Boldt, P., B. Knechtle, P. Nikolaidis, C. Lechleitner, G. Wirnitzer, C. Leitzmann, T. Rosemann, and K. Wirnitzer. 2018. Quality of life of female and male vegetarian and vegan endurance runners compared to omnivores - results from the NURMI study (step 2). Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 15 (1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12970-018-0237-8.

- Borenstein, M. 2019. Common mistakes in meta-analysis and how to avoid them, 388. New Jersey: Biostat. Inc..

- Borenstein, M., H. Rothstein, and J. Cohen. 2005. Comprehensive meta-analysis program and manual. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Biostat.

- Borenstein, M., L. V. Hedges, J. P. T. Higgins, and H. R. Rothstein. 2011. Introduction to meta-analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Brown, P., K. Brunnhuber, K. Chalkidou, I. Chalmers, M. Clarke, M. Fenton, C. Forbes, J. Glanville, N. J. Hicks, J. Moody, et al. 2006. How to formulate research recommendations. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 333 (7572):804–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38987.492014.94.

- Burkert, N. T., W. Freidl, F. Großschädel, J. Muckenhuber, W. J. Stronegger, and É. Rásky. 2014. Nutrition and health: Different forms of diet and their relationship with various health parameters among Austrian adults. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 126 (3-4):113–8. doi: 10.1007/s00508-013-0483-3.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates. Inc.

- Cooper, C. K., T. N. Wise, and L. S. Mann. 1985. Psychological and cognitive characteristics of vegetarians. Psychosomatics 26 (6):521–7. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(85)72832-0.

- Dempster, A. P., D. B. Rubin, and R. K. Tsutakawa. 1981. Estimation in covariance components models. Journal of the American Statistical Association 76 (374):341–53. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1981.10477653.

- Dobersek, U., G. Wy, J. Adkins, S. Altmeyer, K. Krout, C. J. Lavie, and E. Archer. 2020. Meat and mental health: A systematic review of meat abstention and depression, anxiety, and related phenomena. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 61 (4):622–35. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1741505.

- Egger, M., G. D. Smith, M. Schneider, and C. Minder. 1997. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 315 (7109):629–34.

- EndNote X9 2019. Clarivate Analytics. Philadelphia, PA.

- Forestell, C. A., and J. B. Nezlek. 2018. Vegetarianism, depression, and the five factor model of personality. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 57 (3):246–59.

- Friedrich, M. J. 2017. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the worlddepression leading cause of disability globally global health. Jama 317 (15):1517. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3826.

- Gleser, L. J., and I. Olkin. 2009. Stochastically dependent effect sizes. In The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis, eds. H. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, and J. C. Valentine, 357–76. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Goh, C. M. J., E. Abdin, A. Jeyagurunathan, S. Shafie, R. Sambasivam, Y. J. Zhang, J. A. Vaingankar, S. A. Chong, and M. Subramaniam. 2019. Exploring Singapore’s consumption of local fish, vegetables and fruits, meat and problematic alcohol use as risk factors of depression and subsyndromal depression in older adults. BMC Geriatrics 19 (1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1178-z.

- Haddad, E. H., and J. S. Tanzman. 2003. What do vegetarians in the United States eat?The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 78 (3 Suppl):626S–632S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.626S.

- Hartung, J., and G. Knapp. 2001. On tests of the overall treatment effect in meta-analysis with normally distributed responses . Statistics in Medicine 20 (12):1771–1782. doi: 10.1002/sim.791.

- Hedges, L. V. 1981. Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. Journal of Educational Statistics 6 (2):107–128. doi: 10.2307/1164588.

- Hedges, L. V., and I. Olkin. 1985. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Hessler-Kaufmann, J. B., A. Meule, C. Holzapfel, B. Brandl, M. Greetfeld, T. Skurk, S. Schlegl, H. Hauner, and U. Voderholzer. 2020. Orthorexic tendencies moderate the relationship between semi-vegetarianism and depressive symptoms. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity:1–6.

- Hibbeln, J. R., K. Northstone, J. Evans, and J. Golding. 2018. Vegetarian diets and depressive symptoms among men. Journal of Affective Disorders 225:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.051.

- Higgins, J. P., and S. G. Thompson. 2002. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine 21 (11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186.

- Higgins, J. P., and S. G. Thompson. 2004. Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Statistics in Medicine 23 (11):1663–1682. doi: 10.1002/sim.1752.

- Huang, X., J. Lin, and D. Demner-Fushman. 2006. Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions. AMIA annual symposium proceedings, 359.

- Huedo-Medina, T. B., J. Sánchez-Meca, F. Marín-Martínez, and J. Botella. 2006. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index?Psychological Methods 11 (2):193–206. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193.

- Iguacel, I., I. Huybrechts, L. A. Moreno, and N. Michels. 2020. Vegetarianism and veganism compared with mental health and cognitive outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition Reviews 79 (4):361–381.

- Jacka, F. N., J. A. Pasco, L. J. Williams, N. Mann, A. Hodge, L. Brazionis, and M. Berk. 2012. Red meat consumption and mood and anxiety disorders. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 81 (3):196–198. doi: 10.1159/000334910.

- Jin, Y., N. R. Kandula, A. M. Kanaya, and S. A. Talegawkar. 2021. Vegetarian diet is inversely associated with prevalence of depression in middle-older aged South Asians in the United States. Ethnicity & Health 26 (4):504–8. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2019.1606166.

- Kapoor, A., M. Baig, S. A. Tunio, A. S. Memon, and H. Karmani. 2017. Neuropsychiatric and neurological problems among vitamin B12 deficient young vegetarians. Neurosciences 22 (3):228–232. doi: 10.17712/nsj.2017.3.20160445.

- Kerschke-Risch, P. 2015. Vegan diet: Motives, approach and duration. Initial results of a quantitative sociological study. Ernahrungs Umschau 62:98–103.

- Kerschke-Risch, P. 2016. Vegans and omnivores: Differences in attitudes and preferences concerning food. Food Futures. 35: 415–63. doi: 10.3920/978-90-8686-834-6_63.

- Kessler, R. C., W. T. Chiu, O. Demler, K. R. Merikangas, and E. E. Walters. 2005. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62 (6):617–627.

- Lai, J. S., S. Hiles, A. Bisquera, A. J. Hure, M. McEvoy, and J. Attia. 2014. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 99 (1):181–197. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.069880.

- Larsson, C. L., K. S. Klock, A. N. Åstrøm, O. Haugejorden, and G. Johansson. 2002. Lifestyle-related characteristics of young low-meat consumers and omnivores in Sweden and Norway. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 31 (2):190–198. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00344-0.

- Lavallee, K., X. C. Zhang, J. Michalak, S. Schneider, and J. Margraf. 2019. Vegetarian diet and mental health: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses in culturally diverse samples. Journal of Affective Disorders 248:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.035.

- Li, X.-d., H.-j. Cao, S.-y. Xie, K.-c. Li, F.-b. Tao, L.-s. Yang, J.-q. Zhang, and Y.-s. Bao. 2019. Adhering to a vegetarian diet may create a greater risk of depressive symptoms in the elderly male Chinese population. Journal of Affective Disorders 243:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.033.

- Li, Y., M.-R. Lv, Y.-J. Wei, L. Sun, J.-X. Zhang, H.-G. Zhang, and B. Li. 2017. Dietary patterns and depression risk: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research 253:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.020.

- Lindeman, M. 2002. The state of mind of vegetarians: Psychological well-being or distress?Ecology of Food and Nutrition 41 (1):75–86. doi: 10.1080/03670240212533.

- Liu, X., Y. Yan, F. Li, and D. Zhang. 2016. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of depression: A meta-analysis. Nutrition 32 (3):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.09.009.

- Matta, J., S. Czernichow, E. Kesse-Guyot, N. Hoertel, F. Limosin, M. Goldberg, M. Zins, and C. Lemogne. 2018. Depressive symptoms and vegetarian diets: Results from the constances cohort. Nutrients 10 (11):1695. doi: 10.3390/nu10111695.

- Michalak, J., X. C. Zhang, and F. Jacobi. 2012. Vegetarian diet and mental disorders: Results from a representative community survey. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 9:67. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-67.

- Mofrad, M. D., H. Mozaffari, A. Sheikhi, B. Zamani, and L. Azadbakht. 2021. The association of red meat consumption and mental health in women: A cross-sectional study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 56:102588. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102588.

- Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, D. Altman, G. Antes, D. Atkins, V. Barbour, N. Barrowman, and J. A. Berlin. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. the PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine 7:889–96.

- Ng, S. W., and B. M. Popkin. 2012. Monitoring foods and nutrients sold and consumed in the United States: Dynamics and challenges. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 112 (1):41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.015.

- Northstone, K., C. Joinson, and P. Emmett. 2018. Dietary patterns and depressive symptoms in a UK cohort of men and women: A longitudinal study. Public Health Nutrition 21 (5):831–837. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017002324.

- Nucci, D., C. Fatigoni, A. Amerio, A. Odone, and V. Gianfredi. 2020. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (18):6686. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186686.

- Paslakis, G., C. Richardson, M. Nöhre, E. Brähler, C. Holzapfel, A. Hilbert, and M. de Zwaan. 2020. Prevalence and psychopathology of vegetarians and vegans - Results from a representative survey in Germany. Scientific Reports 10 (1):6840–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63910-y.

- Perry, C. L., M. T. Mcguire, D. Neumark-Sztainer, and M. Story. 2001. Characteristics of vegetarian adolescents in a multiethnic urban population. Journal of Adolescent Health 29 (6):406–416. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00258-0.

- Pfeiler, T. M., and B. Egloff. 2018. Examining the "Veggie" personality: Results from a representative German sample. Appetite 120:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.09.005.

- Rosenfeld, D. L. 2019. Why some choose the vegetarian option: Are all ethical motivations the same?Motivation and Emotion 43 (3):400–411. doi: 10.1007/s11031-018-9747-6.

- Stokes, N., C. M. Gordon, and A. DiVasta. 2011. 63. Vegetarian diets and mental health in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Adolescent Health 48 (2):S50–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.11.109.

- Timko, C. A., J. M. Hormes, and J. Chubski. 2012. Will the real vegetarian please stand up? An investigation of dietary restraint and eating disorder symptoms in vegetarians versus non-vegetarians. Appetite 58 (3):982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.005.

- Velten, J., A. Bieda, S. Scholten, A. Wannemüller, and J. Margraf. 2018. Lifestyle choices and mental health: A longitudinal survey with German and Chinese students. BMC Public Health 18 (1):632. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5526-2.

- Vos, T., R. M. Barber, B. Bell, A. Bertozzi-Villa, S. Biryukov, I. Bolliger, F. Charlson, A. Davis, L. Degenhardt, D. Dicker, et al. 2015. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 386 (9995):743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4.

- Whorton, J. C. 1994. Historical development of vegetarianism. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 59 (5 Suppl):1103S–1109S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.5.1103S.

- Wirnitzer, K., P. Boldt, C. Lechleitner, G. Wirnitzer, C. Leitzmann, T. Rosemann, and B. Knechtle. 2018. Health status of female and male vegetarian and vegan endurance runners compared to omnivores—Results from the NURMI study (Step 2). Nutrients 11 (1):29. doi: 10.3390/nu11010029.

- World Health Organization. 2017. Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates, 1–24. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Zeraatkar, D., B. C. Johnston, J. Bartoszko, K. Cheung, M. M. Bala, C. Valli, M. Rabassa, D. Sit, K. Milio, B. Sadeghirad, et al. 2019. Effect of lower versus higher red meat intake on cardiometabolic and cancer outcomes: A systematic review of randomized trials. Annals of Internal Medicine 171 (10):721–731. doi: 10.7326/M19-0622.

- Zhang, Y., Y. Yang, M-s Xie, X. Ding, H. Li, Z-c Liu, and S-f Peng. 2017. Is meat consumption associated with depression? A meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Psychiatry 17 (1):409. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1540-7.