Abstract

The purpose of this study was to develop, implement, and evaluate a support program for parents of male youth academy footballers. Drawing on an action research methodology, underpinned by an interpretivist philosophical approach, this study comprised two action research cycles conducted over a 3-year period. The first action research cycle was the development, delivery, and evaluation of a six-session parent support program, along with three cultural changes. Following evaluation and reflection, the parent support program was modified to comprise a “Being a Football Parent” booklet, a 90-minute support session, and three further cultural changes. Overall, the results highlight the benefits of providing support to parents within youth academy football through a variety of modes and particularly targeting actions at the culture in which parents are situated. This study also demonstrates the value of using action research and having a practitioner-researcher embedded within organizations to facilitate such change. However, there were several challenges when implementing this parent support program and frustrations when creating change within the culture. Guidance for future parent support programs and further research are detailed. Lay summary: Two parent-support programs, comprising parent workshops and/or booklet alongside culture changes, were implemented and evaluated within a youth football academy. The program of support was positively received by parents and seen as beneficial. However, several challenges were encountered, particularly with implementing the cultural changes.

Parent support programs will be enhanced through providing parents with information alongside targeted cultural changes.

Creating an environment that encourages parents to support each other enhances the effectiveness of workshops.

Topics covered within sessions should be directed toward helping parents to manage their demands, build effective relationships with coaches, help parents to understand and meet their sons’ before, during, and after match needs, be aware of and learn to manage their emotions during a match, and adapt their support to their sons’ development

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

ParentsFootnote1 are a vital part of youth sport, no more so than within maleFootnote2 academy football, where players often dedicate their childhood from eight to 18 years to football. Despite their dedication, the success rate of academy players becoming professional footballers is 0.012% (Calvin, Citation2018). Nevertheless, even with this very small success rate, young people who are chosen to be part of a football academy commit to daily training sessions, as well as weekly matches throughout the season. The demands and commitments that arise because of their involvement in academy football can be substantial both for players (Champ et al., Citation2020; Clarke et al., Citation2018; Mills et al., Citation2012) and their parents (Harwood et al., Citation2010). In addition, parents also experience their own demands and sacrifices (Clarke & Harwood, Citation2014). For instance, several studies have found that when supporting their child in sport, parents experience a plethora of stressors and challenges relating to competitive, organizational, and developmental concerns (e.g., Elliott et al., Citation2018; Harwood & Knight, Citation2009; Harwood et al., Citation2019; Lienhart et al., 2019) and supporting children involved in sport can have some negative influences on parents’ mental health (Sutcliffe et al., Citation2021).

While they attempt to manage these stressors and challenges, parents must execute various tasks and actions within their children’s sporting lives ranging from providing emotional and tangible support, to developing relationships with others and displaying emotional control on the sidelines (Harwood & Knight, Citation2015; Holt & Dunn, Citation2004). The extent to which parents “appropriately” carry out these tasks can influence whether children achieve their sporting potential, have a positive psychosocial experience, and experience positive developmental outcomes (Harwood & Knight, Citation2015). Given their influence, providing parents with knowledge, guidance, and support to optimize their involvement in their children’s sporting lives is important (Knight, Citation2019).

Recognizing the importance of parents accessing support and guidance, in recent years several parent education programs have been developed and evaluated within the scientific literature (see Burke et al., Citation2021 for review). These parent education programs have included, among others, in-person programs delivered to gymnastics (Richards & Winter, Citation2013) and tennis parents in the UK (Thrower et al., Citation2017) as well as soccer parents in the US (Vincent & Christensen, Citation2015) and Canada (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020). Further, a combined in-person education session and a guide has been delivered to US soccer parents (Dorsch et al., Citation2017), and online programs delivered to tennis parents in the UK (Thrower et al., Citation2019) and hockey parents in Canada (Tamminen et al., Citation2020). Taken together, these programs have demonstrated that parent education programs can be beneficial for enhancing parents’ knowledge, perceived parenting competence, relationships with others, and their interactions with their children (Burke et al., Citation2021).

However, there are several limitations within the current parent-education evidence base. First, there has been little consideration of parents’ specific support needs within these programs (Knight, Citation2019). That is, many programs have been based on the scientific evidence regarding positive parental involvement (e.g., Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020; Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Tamminen et al., Citation2020), but, except for the work by Thrower et al. (Citation2017, Citation2019), they have not been explicitly tailored to parents’ experiences or support requirements within a particular sporting context. To maximize the benefit of programs to parents, and subsequently children, ensuring parents receive the information, guidance, and support that is most pertinent to them is necessary.

Secondly, to-date, programs have been broadly positioned as education programs that are designed to teach or inform parents how to better support their children or develop skills to display more desirable behaviors in relation to their children’s sport. However, this approach often emphasizes that parents are the problem (Pankhurst & Collins, Citation2013) and the demands experienced by parents are often disregarded. Simply teaching parents how to change their behavior may be ineffective in the face of such demands. Rather, adopting an approach which recognizes parents as valuable members of their children’s broader support team (e.g., Harwood et al., Citation2019) and seeks to provide parents with support rather than education, may empower parents to reflect upon and subsequently change their own behavior.

Finally, the education approach, which focuses on “changing or improving” parents does not take into consideration the impact organizational culture may have on parents’ involvement and their experiences (Knight, Citation2019; Knight & Newport, Citation2020). In the simplest terms, culture is the overarching “way we do things around here” (Cruickshank et al., Citation2013, p. 323) or a set of shared assumptions that define appropriate behavior for various situations (Henriksen et al., Citation2017). Thus, culture includes the behaviors that people display, the relationships they have with each other, organizational policies, the structure of the organization, as well as the conflicts and harmony within the group. When children enter sport or transition between clubs, parents are socialized into the specific organizational culture of that setting, relying on accepted norms and expectations to guide their behavior (Clarke & Harwood, Citation2014; Dorsch et al., Citation2009). As a result of this socialization process, parents may play the part of the “athlete parent” as expected by the organizational culture (McMahon & Penney, Citation2015). Consequently, when seeking to provide support to parents, understanding how organizational culture is impacting their behaviors and support needs, as well as addressing issues within the organizational culture that may affect parents’ involvement, is needed.

Recognizing the benefits of parent support programs, while also acknowledging the limitations of existing ones, the aim of the current study was to develop, implement, and evaluate a program of support for parents of male academy footballers. To address this aim, a two-cycle action research study was carried out within a category one football academy in the UK. Within the UK, football academies were set up to recruit young males from eight years of age, with the aim of supporting development to enable those with sufficient skill to become professional football players. The system is divided into four categories, with category one being the highest. Category one academies typically have the highest number of players and access to better quality and more training facilities, more resources (i.e., staff), more financial income and support from their associated football club, better quality coaching, better education provision for players, and a higher level of welfare provision (including sport science, psychology, and nutrition; Premier League, Citation2023).

Method

Methodology and philosophical underpinnings

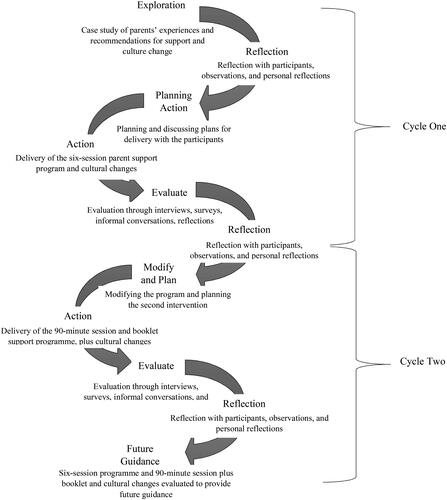

Action research was selected for this study. Action research is carried out in a cycle comprising an ongoing process of observations, reflections, actions, evaluations, and modifications, followed by changes to move in a new direction (Koshy et al., Citation2011; McNiff & Whitehead, Citation2011). Action research is used by practitioners to evaluate their action to identify whether they had an impact and if it has benefited those for whom it was intended (McNiff & Whitehead, Citation2011). The overall purpose is to create new practices through carrying out and reflecting on action (McNiff & Whitehead, Citation2006).

Action research was chosen for this study as it provided the opportunity to implement and evaluate a support program as a sport and exercise psychology practitioner, while also creating new research evidence. Action research is undertaken by practitioners who regard themselves as researchers (McNiff & Whitehead, Citation2006). Research that is carried out by practitioners is considered as living research, where the story of practice and learnings could create theories and knowledge that was relatable to practical application (Reason & Bradbury, Citation2008). This aligned with the lead researcher’s practitioner-researcher approach to produce research to inform practice and carryout practice to inform research. Action research also aligned with the ontological (relativist) and epistemological (constructionist) underpinnings of the research team.

Researcher positionality

The lead researcher (who delivered and evaluated the support program) is a white woman, educated with an undergraduate and postgraduate degree in sport and exercise psychology. At the time of starting the first action research cycle, she was a trainee sport and exercise psychologist and was not a parent. She also had with little football experience, having come from an equestrian and athletics sporting background. As such, when she entered the youth male football academy, she was naïve to football culture, the ways of football academies, the experiences of parents, and some of the nuances of family life in the region. Nevertheless, it presented an opportunity for her to immerse herself in the football parent experience, with limited prior knowledge or assumptions.

Over the course of the study, the lead researcher became a parent for the first time (having a daughter at the end of the second action phase) and by the completion of the study had achieved accreditation as a sport and exercise psychologist and was pregnant with her second child. Becoming a parent, albeit not one whose child was playing football, provided first-hand insight into the bond that exists between parents and children and the overwhelming emotions parents can experience in relation to their children. It also enhanced her understanding of the logistical and practical constraints parents experience. As such, the ways in which she engaged with parents shifted to more of a knowing insider. Moreover, it enhanced her desire for the intervention to work and increased disappointment when challenges were encountered, particularly related to the lack of engagement from parents.

The second and third authors are both white English academics. The second author is a woman, with extensive experience in the fields of youth sport parenting and qualitative research. She was not a parent at the start of this study, but had spent considerable time working with parents, coaches, clubs, and organizations to provide support to parents as a researcher and sport psychology consultant. The third author is a man, with experience as a sport science researcher and practitioner, much within elite football. Both authors became parents during this study, which, like the first author, stimulated their desire for the intervention to “work” and thus encouraged substantial problem solving to try and overcome some of the challenges associated with the intervention. However, it also facilitated consideration of the various reasons why parents may not be engaging.

Action research cycle implementation

Prior to starting this study, a relationship between the football academy and second author, had been established. Specifically, the academy manager had indicated that he, other staff, and players were encountering several challenges that they perceived to arise from inappropriate involvement of parents and as such he was keen to improve how parents were involved at the academy. Additionally, there was a desire to increase the overall sport psychology provision within the academy. Knowing the background of the second author it was suggested that a bespoke parent support program could be created specifically for the academy and be delivered by a sport psychologist alongside broader work with players. Subsequently, funding for the research project was sought by the second author. Ethical approval was also obtained at this point.

To develop this program, the lead author was embedded as a practitioner-researcher within the football academy for three years delivering parent support and sport psychology support to players, coaches, and support staff (with a period of 9 months maternity leave after the second year). Specifically, she was responsible for developing, implementing, and evaluating an evidence-based parent education program (as is detailed in the current study), but was also embedded in the academy as a sport psychologist (in training) to deliver 1–1 and group support to players and coaches. In her role as a practitioner-researcher, she drew upon the practitioner-researcher model developed by Shapiro (Citation1967).

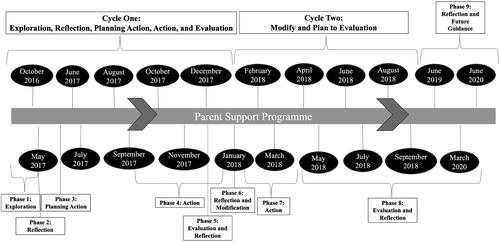

Over the three years, two extended action research cycles were implemented. The action-research cycles for this research were adapted based upon O’Leary’s (Citation2017) multiple cycles of action-research. In the simplest terms, this model suggests that the first phase is to carry out observations. Specifically, the researcher uses a variety of data collection methods within a particular case to gain an understanding of participants’ behaviors and experiences in their natural setting. The second phase comprises reflection on these experiences to guide the subsequent change process. The third phase involves planning the anticipated action. During this phase the researcher answers critical questions and makes choices about the action phase, such as what their research question is and how they will go about carrying out the action. The fourth phase is then to carry out the action and afterwards reflect collaboratively with the participants to observe and identify transformations, plus recognize improvements for future action (Reason & Bradbury, Citation2008). While this model was followed throughout the study, given the need to ensure experiential knowledge from parents, coaches, and practitioners underpinned the planning of action (Koshy et al., Citation2011; McNiff & Whitehead, Citation2006), the observation phase of the first cycle was considerably extended (see ).

Action research cycle 1

Phase one—exploration

A case study of the youth football parent experience was conducted and a series of recommendations for providing support were co-created over a period of eight months. This has been published (Newport et al., Citation2021) and thus, the focus of the current paper is from the reflection phase of action cycle one to the end of cycle two.

Phase two—reflection

This phase comprised a process of personal reflection by the lead author as well as engagement in collaborative reflection with parents, coaches, support staff, and the research team regarding the parent support recommendations produced during the exploration phase. Reflections were carried out through informal conversations, focus groups, research group meetings, and a research feedback meeting with coaches. Having developed an initial understanding of parents’ experiences and avenues through which to provide support, this reflection process focused on creating action through a parent support program. Reflections were carried out within the lead researcher’s reflexive diary, drawing on Gibbs (Citation1988) reflective cycle.

Phase three—planning action

The football off-season and pre-season were spent planning the support that could be provided to parents. This planning occurred as a research team and in collaboration with parents, coaches, and support staff. Plans were influenced by the findings of phase one and two and previous studies (e.g., Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Thrower et al., Citation2017).

Phase four—action

Support sessions for parents and cultural changes were implemented over a period of two months. The program comprised six support sessions for parents aligned to the postulates of sport parenting expertise (Harwood & Knight, Citation2015), which were delivered by the lead author, plus three cultural changes which are detailed in the results (see ). Specifically, through phases one and two, it had become apparent that the organizational culture was one which tolerated parents but did not embrace them. As a result, it was perceived that a full support program would require an emphasis on changing this culture to a more parent positive environment.

Over the course of this action, approximately 130 parents (based on the assumption that each player was represented by one parent) were invited to take part in the parent support sessions. Fifty-two parents attended at least one session and ten attended all six. On average, sessions were attended by 16 parents. All parents were exposed to the culture changes.

Phase five—evaluation and reflection

The evaluation and reflection phase was used to identify elements within the program that were successful and unsuccessful, and what improvements were needed. This evaluation considered the delivery style (discussion-based sessions) and mode, content, engagement, and apparent outcome and impact on parents and the culture (Koshy et al., Citation2011). The evaluation began as soon as the action started and continued for two months after its completion. Evaluation occurred through observations, informal conversations, researcher reflections, parent reflections, survey data, and interviews.

Specifically, the lead author carried out 980 h of observations of the coaches, support staff, and the broader academy environment. She observed multi-disciplinary meetings, evening and weekend training sessions, pre-match team talks, away trips, match analysis, and informal social occasions such as mealtimes. Through informal conversations, she gained insights from parents, players, coaches, and support staff, regarding how they believed the action should be delivered and their reflections on the delivery of the action. The lead author also completed reflections following each support session. Specifically, she documented an outline of the discussions that occurred within the sessions, feedback from parents, information relating to the content of the sessions, observations of parents’ engagement, and details of any organizational cultural changes that have occurred. Changes for subsequent sessions were noted.

Through their attendance at the support sessions, all 52 parents contributed to the evaluation by sharing their thoughts and reflections during sessions. Additionally, all academy parents (whether they had attended sessions or not) were invited to share their reflections on the program (comprising the sessions and cultural changes) through an online survey. A total of 37 parents completed the survey, which included 23 parents who attended at least one session and 14 who did not. Eight participants (three mothers and five fathers) also took part in interviews pre and post the parent support sessions. The interviews ranged in length from 22 min to 200 min pre-support sessions (M = 60 min, SD = 58 min) and from 20 min to 72 min post-support sessions (M = 41 min, SD = 19 min). All evaluation data was combined and analyzed following the recommendations of Miles et al. (Citation2014).

The first stage of analysis was to organize the transcripts, collect the online reflective survey data, and organize the reflexive diary notes, observations, and fieldnotes. Next, the lead author spent substantial time immersed within the data, reading and re-reading transcripts and notes to gain an understanding of the experiences of parents within youth academy football and the impact of the program. Subsequently, based upon the questions asked within the interviews and the structure of the online reflective survey data, deductive categories were created to aid the organization of the data and explore where change occurred. These categories were: “overall benefit,” “content evaluation,” and “improvements needed.” Subsequently, raw data were allocated within the pre-defined categories.

The fourth stage of analysis was to develop inductive codes. This process was guided by Miles and colleagues’ (2014) effects matrix to illustrate the change that occurred because of the parent support sessions and the parent supportive culture. The development of effects matrix provided a visual representation of any change that occurred following the program and provided conceptual clarity through a structured approach. The fifth stage of analysis was the interpretation and refinement of data by collapsing and compressing categories into a reduced number of codes. For example, three codes were refined from “Different perspective,” “Reflection and discuss with other parents,” and “Helping others,” to “Opportunity for reflection on own and others’ behavior.” The sixth stage was to revisit the raw data and check the interpretation provided an appropriate representation of the raw data. Finally, the data were written up.

Action research cycle two

Phase six—reflection and modification

As soon as the evaluation from action cycle one was completed, phase six (the first phase of action cycle two) began. This was a further process of collaborative reflection using Gibbs (Citation1988) reflective cycle to identify areas for improvement within the program. The planning of action for the second cycle then began. Specifically, in a change from cycle one, planning the delivery for the second action cycle included designing and printing a booklet that would be delivered alongside a condensed parent support session and further cultural changes.

Phase seven and eight—action and evaluation

This revised parent support program included a support session, supported by a booklet, and three cultural changes (detailed below). In total, 21 parents took part in the support session (three of whom had previously attended the six-session program). Again, evaluation started from the delivery of the support session until three months following the delivery. Having encountered issues recruiting parents for interviews in cycle one and learning that it put parents off the program, these were removed in cycle two. Rather, parents were only asked to share feedback immediately after the session with the lead author and then through a survey. Despite numerous reminders, only six parents (three female and three male) completed the survey. This data was supplemented with 800 h of observations, informal conversations with parents, coaches, and support staff, fieldnotes and the lead authors reflections reflexive diary. Data were again analyzed in line with the guidance of Miles et al. (Citation2014).

Phase nine: reflection and future guidance

After completion of the second parent support program, the lead author remained embedded in the academy engaging with parents, coaches, and players, carrying out observations, and fieldwork in the form of sport psychology support to parents, coaches, and players. This period allowed for continued observation and reflection on the ongoing cultural changes, as well as an opportunity to develop ideas and recommendations for future programs.

Methodological rigour

This study was carried out in accordance with the 12 criteria specified by Evans et al. (Citation2000) for action research studies. Evans and colleagues criteria ranged from the commitment to a real-life problem and seeking to create change, through to engagement with participants, a systematic approach, and including participants in the process. An overview of the steps taken to align with these criteria are provided as supplementary materials. In addition, due to the lead author being embedded within the organization as a practitioner-researcher, she was able to gain substantial insider perspectives regarding the organizational culture and related changes, which substantially enhanced the quality of the study.

Results

In the following sections each phase of the action research cycles is described detailing pertinent findings, with a particular emphasis on the evaluation of each action.Footnote3

Phase 2—reflection

Drawing on the results of phase 1 (Newport et al., Citation2021) , overall, it was recognized that parents’ experience is challenging and complex. As such, it was perceived that parents would benefit from support sessions tailored to the individual phases of their journey and that are flexible to allow for the demands they experience. Further it was clear the support program should also comprise a series of cultural changes within the environment to create a parent supportive culture.

Phase 3—planning action

Based on the reflections in phase two, as well as preexisting literature, a support program, “Being a Football Parent,” which comprise six parent support sessions combined with the implementation of a series of targeted cultural changes, was planned. The support sessions aimed to cover the six-postulates identified by Harwood and Knight (Citation2015) as the key competencies for optimal sport parenting and aligned with findings from the exploration phase of this research (Newport et al., Citation2021). The six sessions were: Tackling the football parenting game (managing organizational demands and providing tangible support), Communicating with the team (enhancing their relationship with the coaches and other parents), Being a football parent (adopting an autonomy supportive parenting style), Supporting your child (providing support to their son and how this evolved), The ups and downs of matches (the emotions of matches and how to manage them), and Bumps in the road (future challenges and considering how parents may manage them) (see ).

Table 1. Content of the parent support sessions.

Recognizing that parents at different stages have different experiences, each session was delivered multiple times targeted at different ages groups (U9/10, U11/12, U13/14, U15/16). This enabled content to be adapted and aligned with their specific needs. For example, for U9 and 10 parent sessions focused on transitioning into the academy, whereas the same session with U15/16 parents focused on scholarship decisions, supporting their son to be more independent, and their sons’ current education demands.

The parent supportive culture focused on the creation of an environment that considered parents as a key part of youth football development and an organizational culture that respected and valued parents. The cultural changes were planned to occur through the lead author being embedded within the football academy environment, actively challenging individuals within the academy regarding their approach to parents, role modeling positive behavior toward parents, and supporting the development of more effective parent-coach relationships. Specific changes that were targeted included, facilitating easier access to the parents’ lounge, providing parents with access to refreshments, the distribution of schedules earlier, and more notice of schedule changes being provided. In addition, coaches were encouraged to consult parents on changes to training schedules, actively seek feedback from parents, introduce a parents’ voice forum, and use videos within player performance reviews to provide parents with greater insight in their children’s development.

Phase 4—action: implementing the “being a football parent” support program

The parent support sessions were advertised to parents through an email one month prior to delivery starting, followed by a reminder a week before each session. They were also advertised through word of mouth during informal conversations with parents.

Support session delivery

The support sessions were delivered over an 8-week period (a change from the planned six weeks due to unavoidable clashes with academy commitments). Sessions were delivered in football academy classrooms, at the same time as training sessions, with a light buffet of refreshments provided. The sessions were delivered in an interactive and supportive manner to create an environment where parents felt welcomed, respected, and a valued part of the organizational culture.

Implementing cultural changes

The focus on cultural changes began two months prior to the support sessions and continued until the end of the sessions. The implementation of these were carried out using the Three Perspective Approach (Martin, Citation2002). The Three Perspective Approach considered the complexities of the academy culture, provided guidance on how the cultural changes could be made, and highlighted where there may be conflict and resistance to change. For instance, the different age groups and departments within the academy created subcultures, while the varying backgrounds of the coaches and support staff created individual identities. These subcultures and identities created further complexities and impacted coaches’ engagement with the cultural changes.

Phase 5—evaluation of the “being a football parent” support program

Overall, the parents who attended the sessions and were impacted by the cultural changes indicated that they benefited from and enjoyed them. One parent wrote on the online survey that, “I thought the course was very good and informative.” Another parent added that the sessions provided, “an opportunity to understand the academy environment.” Nevertheless, there were some challenges identified relating to the desired cultural changes, as well as attendance and scheduling issues. The specific benefits and challenges associated with the overall program are provided in .

Table 2. Overall program evaluation.

Perceptions of support session topics

From the interviews, survey, informal conversations, and the lead author’s reflexive diary it appeared that parents engaged well with the chosen content. One parent said, “the course content was very informative and very well presented.” One under-14 mother also said, “all topics were really helpful.” However, some issues with the topics were also identified. For example, it was noted in the lead author’s reflexive diary, “today it was challenging to get parents to engage in the topic as they were preoccupied by their frustrations with the academy communication.” provides an overview of participants’ views of the topics.

Table 3. Perceptions of support session topics.

Positioning, delivery, and structure of support sessions

Prior to delivering the sessions, substantial consideration was given to how the sessions were structured and delivered to attract parents and encourage their engagement. The method of delivery and structure of the sessions appeared to be particularly important for parents. Specific feedback pertaining to positioning, delivery, and structure of sessions is provided in .

Table 4. Positioning, delivery, and structure of support sessions.

Evaluation of cultural changes

Overall, implementation of the cultural changes, demonstrated through specific actions, had varying success. The evaluation of the cultural changes aligned with attempts to create a more welcoming and inclusive environment for parents, increasing respect for parents created through enhanced relationships, and valuing parents’ role within their son’s development (see ).

Table 5. Evaluation of cultural changes.

Future recommendations

Following the delivery of the program, parents were asked to indicate improvements that could be made to the program. Parents detailed several recommendations, which are detailed in .

Table 6. Recommendations for future programs.

Phase 6: reflection and modification

Overall, evaluation of the initial program indicated that the parents benefited from the support program. Despite these benefits, caution was used when making conclusions regarding the efficacy of the program due to the number of parents attending the sessions, as well as the limited number of parents who engaged in the formal evaluation process. Issues with parents attending such programs is not unique to this intervention (see e.g., Thrower et al., Citation2017; Vincent & Christensen, Citation2015). Nevertheless, it was deemed that an alternative method of delivery was needed going forwards. Additionally, several challenges were encountered regarding creating a more parent supportive culture. Such challenges were anticipated because culture change takes considerable time. However, it was clear a continued focus upon cultural changes was needed to enhance the program.

Phase 7: planning and action: developing a revised parent support program

Based on the evaluation of the previous action, a revised program was developed. This comprised the delivery of a 90-minute support session, a “Being a Football Parent” booklet, and further cultural changes. The inclusion of an in-person support session was deemed appropriate because the initial program evaluation showed that parents found the opportunity to engage with their parent peers and interact with the lead researcher useful. The decision to reduce the number of sessions and include a booklet, was made in an attempt to increase attendance numbers by reducing time demands on parents. The topics included in the support session and the booklet were the same as those delivered in the first intervention. Although not all the topics were perceived to be as beneficial as others within the initial intervention, given that the overall content of the sessions was found to be useful, the decision was made to retain these.

The booklet structure comprised a very brief explanation of each topic, followed by an activity to encourage discussion or reflection and one take home message. The booklet was designed to offer parents a self-paced curriculum (Dorsch et al., Citation2017), with the recognition that each parent is an expert on their own experience and their child. The booklet was A5 size and contained 100-200 words per page. In combination with the booklet and support session, targeted actions to enhance the culture of the academy continued. From the evaluation and reflection phase (phase 5), it was decided that the cultural changes should focus on providing parents with a voice, increasing the number of meetings with parents to create more open communication, and introducing a parent open evening.

Phase 8: evaluation

Overall, parents said that they, “found it good” and the booklet was “a supportive tool” that was “very well set out.” Similarly, the lead author recorded within her reflexive diary that the parents appeared to benefit from the support session as, “the parents were able to speak freely and ask about any concerns, they could talk to other parents, and understand the experience a bit more.” Parents detailed, and the lead author observed, that the support session and booklet was useful because they helped parents to apply previous learning and increase their knowledge, while also being able to reflect on their current journey. Additionally, it was found to provide “some useful info on who to contact and the process ahead,” plus it “made me feel part of the experience” and “all information given to us is useful and helps us make better decisions/understand things.”

Furthermore, the cultural changes also had a positive impact on parents’ experience within the academy. For example, through the online survey one parent simply stated, “thank you as a club for your support.” Another parent, during an informal conversation, recognized the value in changing the season dates for the academy to fall in line with the school holidays, allowing them to have a summer holiday away from school and the academy, “I'm glad that the boys and us parents have had a longer summer break this year.” Further details on the overall program evaluation are provided in .

Session and booklet evaluation

Overall, parents indicated that the booklet and the session was useful in helping them to develop as parents for a variety of reasons. However, they also reported some frustrations and issues (see ).

Table 7. Overall evaluation of the second program.

Evaluation of cultural changes

During this program, the focus was on introducing parent feedback meetings, obtaining end of season parent feedback, and introducing coach-led parent information evenings and open training sessions. The improved communication between academy staff and parents helped parents to keep up-to-date with the changes that were occurring within the academy and manage their organizational demands. The cultural changes were perceived to increase how welcomed, respected, and valued parents felt. Overall, the changes appeared to help parents and support them to enjoy their experience at the football academy. Particularly, the culture changes demonstrated that the delivery of the parent support program helped parents beyond those who engaged with the booklet and support session. However, some challenges were again encountered when attempting to make these changes (see ).

Table 8. Session and Booklet Evaluation.

Table 9. Evaluation of cultural changes.

Phase 9: reflections—challenges and suggestions for improvements

To further improve the parent support program, parents were asked through a survey and informal conversations to provide feedback regarding how the program could be enhanced to further meet their needs and benefit other parents. Alongside the recommendations from parents, the research team also identified several suggestions for improvement. These are noted throughout the discussion section below.

Reflections and discussion

The current study provides insights into the process of developing, implementing, and evaluating two action research cycles, with the aim of providing support to parents of youth academy footballers. Overall, the results demonstrate numerous benefits associated with the implementation of parent support programs, particularly when they combine an informational component with cultural changes. As the first program which has attempted to do this, the results also provide highlight some of the challenges with such an approach. Further, the results shed light on the variety of modes through which information and support can be provided and the types of content that may be useful to share with parents. Moreover, the current study demonstrates the benefit of utilizing an action research approach and having a researcher-practitioner embedded within an organization to facilitate change. However, consistent with previous literature, the paper also highlights the challenges of engaging parents and the difficulties of obtaining evaluation data (Burke et al., Citation2021).

Reflecting on these two action cycles there are several findings that should be considered when seeking to support parents in the future. First, delivering support to parents within academy football is challenging and complex. Consistent with previous literature (Burke et al., Citation2021), parents’ attendance was low in both actions, despite relationships being built, the program being embedded within an academy, and adaptations being made to make it as convenient as possible. This low attendance is potentially the result of parents experiencing too many demands within their role as an academy football parent (Harwood et al., Citation2010), combined with the demands of everyday family life and/or work commitments (Harwood et al., Citation2019). Consequently, working with parents from the outset to create a program that works for them in terms of mode of delivery, day of delivery, timings is required to maximize attendance (Dorsch et al., Citation2019; Kwon et al., Citation2020; Thrower et al., Citation2019).

Moreover, further consideration of appropriate theories, such as those related to behavior change and enhancing intrinsic motivation, may be beneficial to increase attendance. For instance, as proposed within self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017), by providing the opportunity for parents to satisfy their basic psychological needs during sessions, they may perceive their action to attend sessions as more internalized and self-determined resulting in increased engagement. There are several means through which the parents’ basic needs could be met. For instance, competence could be increased by creating more opportunity for parents to feel successful as a parent. Autonomy could be created by parents being more involved in the development of the parent support program and consequently feel they are in control of the support to which they are exposed. Finally, parents enjoyed being able to share experiences so making it clear that this is a feature of the program when advertising it may increase attractiveness.

However, it’s also important to recognize that the low levels of engagement might simply be reaffirming that there cannot be a “one size fits all approach” to parent support (Dorsch et al., Citation2021, p.549) and that different modalities may be favored by different parents. As such, focusing on cultural changes that will influence all parents is a valuable alternative focus. Within this study, there were some successful cultural changes which impacted the overall environment and consequently all parents’ experiences. For instance, parents having access to selected training sessions, having access to facilities during training, and being invited to information meetings with coaches all helped to create a more welcoming environment for parents—whether they attended the parent support sessions or not. However, gaining buy-in from the coaching staff was challenging. As such, to move this work forwards, ensuring practitioners are embedded within environments for extended periods of time is necessary. Moreover, gaining support for initiatives from the key influencers (e.g., managers, head of coaching) is needed to help to enforce cultural changes.

It should be noted that on completion of the two action research cycles, the program was transitioned to the club, specifically the head of coaching and the academy manager. Feedback from this program was shared with these individuals (in addition to that which had been shared throughout the process) and the specific materials and recommendations for future programs were shared. Unfortunately, not long after this, the academy manager changed, and some of the coaching staff left. Consequently, the program lost momentum, and, to our knowledge, there are no longer specific sessions delivered to parents as part of a program. However, the second author continues to be involved in the academy and it is apparent that organizational cultural approach to parents, which began to shift during this program, has continued and parents are more welcome within the environment. Specifically, a parents’ forum was set up and parents are invited to more training sessions. Furthermore, some of the coaching staff who were present during the delivery of this program have continued to host more regular meetings with parents and encourage others to do so as well.

In both programs detailed in this paper, parents benefited from the support sessions being provided face-to-face. Parents enjoyed being able to share their experiences, learn from other parents, reflect as a group, and gain support from other parents, which supports the findings of other sessions delivered to parents (Thrower et al., Citation2017; Vincent & Christensen, Citation2015). This support from engaging directly with other parents helped parents to normalize their experiences and develop more coping mechanisms, which has previously been identified as useful for parents given the demands experienced within youth sport (Burgess et al., Citation2016; Lienhart et al., Citation2020). Although the six support sessions in the first cycle provided multiple opportunities for parents to gain support from each other, the one-off support session within the second cycle seemed just as useful for facilitating group reflections and support among parents. Therefore, although parents enjoy engaging with each other and gaining support from one another, when their time is limited, reducing but not eliminating in-person support sessions is important.

When delivering in-person sessions, however, the program facilitator needed to have appropriate strategies to ensure that parents stayed on topic and that personal complaints did not derail conversations. Within this study, and previous studies (e.g., Vincent & Christensen, Citation2015), managing group dynamics was not always easy. But it is particularly important because parents may be put off attending future sessions if the discussions are not managed appropriately. One suggestion to manage group dynamics from group therapy is for the practitioner to create group-based decision-making guidelines to help practitioners know how far to allow discussions to deviate, while allowing flexibility within the discussion (Wendt & Gone, Citation2018). Drawing on this suggestion, prior to future delivery it may be useful to create such guidelines to facilitate meaningful discussions within the sessions. In addition, developing a process to ensure that parents’ personal issues are still voiced and heard by the academy is necessary to prevent further frustrations occurring.

The sessions and booklet within the two parent support programs covered the same six topics based upon Harwood and Knight (Citation2015) postulates of sport parenting expertise. However, parents’ engagement with these topics varied based on the specific content, their emotional response to the information, and how confident the facilitator felt delivering the content. The topics parents best engaged with were those that initiated a positive emotional response, potentially due to an association with positive memories, a general feeling of enjoyment, or providing clear strategies to help them. The positive emotional response that was elicited also appeared to enhance learning, likely due to an increased interest and excitement for the topics and subsequently motivation to learn (Rowe et al., Citation2015). For instance, the “Tackling the football parenting game” was found to be useful for parents to consider their coping mechanisms for managing demands, “The ups and downs of matches” reminded them of how much they enjoyed watching their son play football, and “Bumps in the Road” was a useful session for parents as they were able to hear about and plan for the journey ahead of them. Given these findings, when creating programs in the future it may be useful for parent support sessions to focus on topics that stimulate positive emotions or are clearly practically useful.

In contrast, “Communicating with the team” was not as well received and generated many negative reactions. Although progress was being made to enhance the communication between the academy and parents, this topic elicited feelings of anger and frustration due to parents perceiving substantial communication issues at the academy. Previous evidence has suggested that creating feelings of anger within a learning environment can enhance learning (Rowe & Fitness, Citation2018). However, in this situation, this was not the case. Rather, parents’ anger and frustration were a distraction from the learning outcomes of the topic and parents began simply offloading and sharing their frustrations. Consequently, it may be more useful for academies or youth sports clubs/organizations to target changes in communication directly, rather than it being addressed in sessions with parents.

Applied implications: suggestions for future parent programs and youth sport action research

The final part of action research is to provide recommendations for future actions. Based on the reflections from this study, numerous suggestions to optimize future parent programs are apparent. First, it is important that programs are provided at the start of the academy journey (either when players join at under-9 or later on if they join through a trial process) to maximize parents’ engagement from the outset. Second, ensuring sessions are delivered by a sport psychologist or sport scientist with an understanding of the parent experience and strategies to manage potentially emotive and challenging conversations is beneficial given the sensitive nature of some discussions. Moreover, sessions should focus on providing information and creating an environment that encourages parents to support each other. These sessions should be delivered in a discussion-based format that encourages reflection, is family-friendly, and includes refreshments to create a welcoming environment.

Third, the topics covered within sessions should be directed toward helping parents to manage their demands, build effective relationships with coaches, help parents to understand and meet their sons’ before, during, and after match needs, be aware of and learn to manage their emotions during a match, and adapt their support to their sons’ development. Parents found these topics useful and beneficial, but the content within the topics should be adapted appropriately to children’s and parents’ journey. Given time challenges associated with the longer program, but also the difficulties of condensing all the material into one session, a support program of three sessions may be most useful. This would enable parents to have in-depth discussion, something that was highly valued in the programs, without requiring an extensive commitment from parents.

Fourth, given the limited numbers of parents who attended sessions and the often-cited timing issues, it may be useful to supplement formal workshops with flexible drop-in sessions or short “catch-up” opportunities. Alternatively, given the desire for, and benefits associated with, in-person discussions, it may be useful evaluating the impact of a blended learning approach, whereby person support is combined with online information and activities. Moreover, using an online platform, especially if it can be accessed on a phone or tablet, means that information is always available.

Fifth, alongside the delivery of support sessions, clubs, academies, and organizations should seek to create a parent supportive culture. Although delivering this complete program of support (i.e., one that includes support sessions as well as targeting environmental/cultural changes) may seem onerous, this does not have to be the case. Academies and organizations can see great benefit from focusing on relatively simple changes that produce a more welcoming environment for parents. For instance, a space where parents can purchase refreshments and work may alleviate demands parents experience and make them feel like they want to spend time in the space. Such changes do not require considerable time or effort but may overcome frustrations that parents experience and subsequently lead to more positive parent-coach and parent-player interactions.

For researchers or practitioners seeking to integrate an action research approach or deliver a support program with other stakeholders within youth sport settings, there are also several recommendations. The first is to ensure that you have buy-in from the key individuals within the setting. These may not necessarily be those in the managerial positions but should be those who have the greatest influence over others in the setting. It may take some time to identify this person but will be beneficial in the long run. Once this person or persons is identified, ensuring they are kept informed regularly regarding the research and the ongoing impact is extremely valuable. Building this into the reflective process is useful.

Secondly, committing extensive time to the initial observation stage of the action research process is useful to gain a full picture of the required action. However, one must also recognize that rapid and unexpected changes and adaptations may be required throughout the program of work. Thus, being open to change and having a flexible approach is necessary. But that is not always easy, as the research program can be come all consuming as attempts to recognize, reflect upon, and continually change in response to participant needs occurs. Thus, taking care of oneself through this process is important. Utilizing a team to support reflections, stepping away from the program and identifying where things have worked, as well as where things have gone wrong, will help researchers to successfully navigate the inevitable ups and downs of such applied research.

Finally, clarity regarding the evaluation process, specifically, understanding the capacity of the organization to engage in evaluation is required. Within the current study, formal (i.e., interviews and surveys to explore the outcomes of the intervention) and informal evaluation (i.e., informal conversations with participants to understand engagement with the intervention) was embedded in the work as well as clear timelines and approaches to engaging in evaluation were stipulated from the outset. Moreover, as this program was set-up as a specific project, to be conducted by a particular individual, time was allocated to evaluation. However, it was apparent that the organization’s capacity to engage in formal evaluation of much of its ongoing work, as well as the expectation for such evaluation, was relatively limited. Not least because such evaluation was not typically viewed as part of the requirements of activities. To enhance and improve programs for their participants in the future, ensuring evaluation approaches, timelines, and responsibilities are highlighted from the outset is key.

Limitations and future research directions

This research was carried out in one academy and may not apply to all parents in other football academies or sport settings. There may be cultural variations, for example the extent of travel demands and ethnicity of the parents within a club. The family structures of participants are unknown and as such may not be representative of all family arrangements. Future research would benefit from exploring parent experiences within and beyond academy football across family structures and cultures.

The action research cycles were evaluated in relation to the impact on parents alone. Understanding whether parents transferred the information they learnt into their interactions with their sons would be useful. Additionally, understanding the impact of these programs on the wider family, particularly if it is positive, may provide more evidence to support the development and implementation of such programs. Thus, future research which includes siblings, partners, and grandparents in the evaluation might be useful. Additionally, this study did not explore the impact of the actions on the coaches and support staff. This is important when considering implementing cultural changes, because without an understanding of how these changes are influencing all those within the culture (see Dorsch et al., Citation2022), the overall effectiveness of such changes remains unknown.

Finally, formal evaluation/feedback from parents was rather limited. Future studies may benefit from using more explicit implementation tools (e.g., Intervention Mapping Protocol; Kok et al., Citation2004) and/or evaluation frameworks, such as Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick (Citation2016) Comprehensive Evaluation Model or the RE-AIM framework (see Bengtsson et al., in press; Thrower et al., Citation2023) to enhance the focus and efficacy of their evaluation. Using implementation and/or evaluation frameworks from the outset of interventions provides clear guidance and a structure to target evaluation efforts and hopefully enhance efficacy of programs. Moreover, embedding program evaluation within the typical day-to-day business of the setting (particularly their regular evaluation processes) may be useful – for instance during regular review processes or meetings.

Additionally, consideration should be given to the logistics of data collection to ensure that it is as easy as possible for parents to complete. For example, the informal conversations and observations worked well as data collection due to the limited impact on parents’ time and commitments. Linked to this, both the action research cycles were delivered and evaluated by the lead author. As a result, participants may have given socially desirable responses during the evaluation process, particularly the informal conversations.

Conclusion

The findings from two action research cycles have shown that it is beneficial for parents of academy football players to be provided with support sessions, take home resources, and cultural changes that create a parent supportive environment. Specifically, it highlights the benefit of focusing on supporting parents to optimize their involvement in their child’s sporting lives, rather than simply educating them on how they can be better. Nevertheless, they also highlight several areas for future consideration and improvement, including refining the program proposed through focusing future sessions on parents transitioning into the academy, developing an electronic form of the booklet, expanding cultural changes, and evaluating the impact of the program on players and coaches, as well as parents.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The term ‘parents’ is used to refer to all who fulfil a parental role, including guardians, carers, and step-parents.

2 Throughout this manuscript, we have referred to players by sex terms (i.e., male) rather than gender to align with the categorization within academy football. However, we recognize the difference between sex and gender and that gender is of great importance given the gendered norms within sport.

3 Given the qualitative nature of the data and consequently the potential for participants to be identified, the data is not openly available.

References

- Azimi, S., & Tamminen, K. A. (2020). Parental communication and reflective practice among youth sport parents. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2019.1705433

- Bengtsson, D., Stenling, A., Nygren, J., Ntoumanis, N., & Ivarsson, A. (in press). The effects of interpersonal development programmes with sport coaches and parents on youth athlete outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 70, 102558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102558

- Burgess, N. S., Knight, C. J., & Mellalieu, S. D. (2016). Parental stress and coping in elite youth gymnastics: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health, 8(3), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2015.1134633

- Burke, S., Sharp, L.-A., Woods, D., & Paradis, K. F. (2021). Enhancing parental support through parental-education programs in youth sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1992793

- Calvin, M. (2018, January 7). No hunger in paradise [documentary]. BT Sport. http://sport.bt.com/video/bt-sport-films-no-hunger-in-paradise-91364241852638

- Champ, F. M., Nesti, M. S., Ronkainen, N. J., Tod, D. A., & Littlewood, M. A. (2020). An exploration of the experiences of elite youth footballers: The impact of organizational culture. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32(2), 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1514429

- Clarke, N. J., Cushion, C. J., & Harwood, C. G. (2018). Players’ understanding of talent identification in early specialization youth football. Soccer & Society, 19(8), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2018.1432388

- Clarke, N. J., & Harwood, C. G. (2014). Parenting experiences in elite youth football: A phenomenological study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(5), 528–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.05.004

- Côté, J. (1999). The influence of the family in the development of talent in sport. The Sport Psychologist, 13(4), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.13.4.395

- Coté, J., Horton, S., MacDonald, D., & Wilkes, S. (2009). The benefits of sampling sports during childhood. Physical & Health Education Journal, 74(4), 6–11.

- Cruickshank, A., Collins, D., & Minten, S. (2013). Culture change in a professional sports team: Shaping environmental contexts and regulating power. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 8(2), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.8.2.319

- Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (2017). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. In Interpersonal development (pp. 161–170). Routledge.

- Dorsch, T. E., King, M. Q., Tulane, S., Osai, K. V., Dunn, C. R., & Carlsen, C. P. (2019). Parent education in youth sport: A community case study of parents, coaches, and administrators. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(4), 427–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1510438

- Dorsch, T. E., King, M. Q., Dunn, C. R., Osai, K. V., & Tulane, S. (2017). The impact of evidence-based parent education in organized youth sport: A pilot study. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 29(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2016.1194909

- Dorsch, T. E., Smith, A. L., & McDonough, M. H. (2009). Parents’ perceptions of child-to-parent socialization in organized youth sport. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 31(4), 444–468. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.31.4.444

- Dorsch, T. E., Smith, A. L., Blazo, J. A., Coakley, J., Côté, J., Wagstaff, C. R. D., Warner, S., & King, M. Q. (2022). Toward an integrated understanding of the youth sport system. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 93(1), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2020.1810847

- Dorsch, T. E., Wright, E., Eckardt, V. C., Elliott, S., Thrower, S. N., & Knight, C. J. (2021). A history of parental involvement in organized youth sport: A scoping review. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 10(4), 536–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000266

- Elliott, S., Drummond, M. J. N., & Knight, C. J. (2018). The experiences of being a talented youth athlete: Lessons for parents. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30(4), 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1382019

- Evans, L., Fleming, S., & Hardy, L. (2000). Situating action research: A response to Gilbourne. The Sport Psychologist, 14(3), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.14.3.296

- Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit.

- Grolnick, W. S. (2002). The psychology of parental control: How well-meant parenting backfires. Psychology Press.

- Harwood, C. G., Drew, A., & Knight, C. J. (2010). Parental stressors in professional youth football academies: A qualitative investigation of specialising stage parents. Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, 2(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/19398440903510152

- Harwood, C. G., & Knight, C. J. (2009). Stress in youth sport: A developmental investigation of tennis parents. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(4), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.01.005

- Harwood, C. G., & Knight, C. J. (2015). Parenting in youth sport: A position paper on parenting expertise. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16(1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.03.001

- Harwood, C. G., Thrower, S. N., Slater, M. J., Didymus, F. F., & Frearson, L. (2019). Advancing our understanding of psychological stress and coping among parents in organized youth sport. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1600. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01600

- Henriksen, K., Storm, L. K., & Larsen, C. H. (2017). Organizational culture and influence on developing athletes. In Sport psychology for young athletes (pp. 216–227).

- Holt, N. L., & Dunn, J. G. H. (2004). Toward a grounded theory of the psychosocial competencies and environmental conditions associated with soccer success. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 16(3), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200490437949

- Holt, N. L., Tamminen, K. A., Black, D. E., Mandigo, J. L., & Fox, K. R. (2009). Youth sport parenting styles and practices. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 31(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.31.1.37

- Kay, T. (2000). Sporting excellence: A family affair? European Physical Education Review, 6(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X000062004

- Kirkpatrick, J. D., & Kirkpatrick, W. K. (2016). Four levels of training evaluation. ATD Press.

- Knight, C. J. (2019). Revealing findings in youth sport parenting research. Kinesiology Review, 8(3), 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2019-0023

- Knight, C. J., & Newport, R. A. (2020). The role of parents in developing elite soccer players. In J. G. Dixon, J. B. Barker, R. C. Thelwell, & I. Mitchell (Eds.), The psychology of soccer (pp. 119–132). Routledge.

- Kok, G., Schaalma, H., Ruiter, R. A., Van Empelen, P., & Brug, J. (2004). Intervention mapping: protocol for applying health psychology theory to prevention programmes. Journal of Health Psychology, 9(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105304038379

- Koshy, E., Koshy, V., & Waterman, H. (2011). Action research in healthcare. Sage.

- Kwon, J., Elliott, S., & Velardo, S. (2020). Exploring perceptions about the feasibility of educational video resources as a strategy to support parental involvement in youth soccer. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 50, 101730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101730

- Lally, P., & Kerr, G. (2008). The effects of athlete retirement on parents. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(1), 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200701788172

- Lienhart, N., Nicaise, V., Knight, C. J., & Guillet-Descas, E. (2020). Understanding parent stressors and coping experiences in elite sports contexts. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 9(3), 390–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000186

- Martin, J. (2002). Organizational culture: Mapping the terrain. Sage.

- McMahon, J. A., & Penney, D. (2015). Sporting parents on the pool deck: Living out a sporting culture? Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health, 7(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2014.901985

- McNiff, J., & Whitehead, J. (2006). All you need to know about action research: An introduction. Sage.

- McNiff, J., & Whitehead, J. (2011). All you need to know about action research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saladaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Mills, A., Butt, J., Maynard, I., & Harwood, C. (2012). Identifying factors perceived to influence the development of elite youth football academy players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(15), 1593–1604. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.710753

- Neely, K. C., McHugh, T. L. F., Dunn, J. G., & Holt, N. L. (2017). Athletes and parents coping with deselection in competitive youth sport: A communal coping perspective. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 30, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.01.004

- Newport, R. A., Knight, C. J., & Love, T. D. (2021). The youth football journey: Parents’ experiences and recommendations for support. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(6), 1006–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1833966

- O’Leary, Z. (2017). The essential guide to doing your research project (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Omli, J., & LaVoi, N. M. (2012). Emotional experiences of youth sport parents I: Anger. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 24(1), 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2011.578102

- Pankhurst, A., & Collins, D. (2013). Talent identification and development: The need for coherence between research, system, and process. Quest, 65(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2012.727374

- Premier League (2023). Long-term strategy designed to advance Premier League youth development [Webpage]. https://www.premierleague.com/youth/EPPP

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2008). The Sage handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Richards, K., & Winter, S. (2013). Key reflections from “on the ground”: Working with parents to create a task climate. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 4(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2012.733909

- Rowe, A. D., & Fitness, J. (2018). Understanding the role of negative emotions in adult learning and achievement: A social functional perspective. Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 8(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8020027

- Rowe, A. D., Fitness, J., & Wood, L. N. (2015). University student and lecturer perceptions of positive emotions in learning. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.847506

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

- Shapiro, M. B. (1967). Clinical psychology as an applied science. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 113(502), 1039–1042. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.113.502.1039

- Smoll, F. L., Cumming, S. P., & Smith, R. E. (2011). Enhancing coach-parent relationships in youth sports: Increasing harmony and minimizing hassle. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 6(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.6.1.13

- Sutcliffe, J. T., Kelly, P. J., & Vella, S. A. (2021). Youth sport participation and parental mental health. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 52, 101832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101832

- Tamminen, K. A., McEwen, C. E., Kerr, G., & Donnelly, P. (2020). Examining the impact of the respect in sport parent program on the psychosocial experiences of minor hockey athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(17), 2035–2045. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1767839

- Thrower, S. N., Harwood, C. G., & Spray, C. M. (2017). Educating and supporting tennis parents: An action research study. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 9(5), 600–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1341947

- Thrower, S. N., Harwood, C. G., & Spray, C. M. (2019). Educating and supporting tennis parents using web-based delivery methods: A novel online education program. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(3), 303–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1433250

- Thrower, S. N., Spray, C. M., & Harwood, C. G. (2023). Evaluating the “optimal competition parenting workshop” using the RE-AIM framework: A 4-year organizational-level intervention in British junior tennis. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 45(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2022-0080

- Vincent, A. P., & Christensen, D. A. (2015). Conversations with parents: A collaborative sport psychology program for parents in youth sport. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 6(2), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2015.1054535

- Wendt, D. C., & Gone, J. P. (2018). Complexities with group therapy facilitation in substance use disorder specialty treatment settings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 88(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.02.002