Abstract

People participate in many different types of physical activity, both daily and across their life span, but research on human movement is often siloed by type (sport, exercise, active transportation, etc.). Models developed for understanding participation in specific types of physical activity remain useful in those contexts, but are insufficient for describing, explaining, or enhancing movement at the individual or societal level. Physical literacy has the potential to serve this purpose, but its current application does not fulfill its potential for holistic and inclusive promotion of movement. This paper therefore introduces a new framework for physical literacy, Four Domains for Development for All (4D4D4All). This framework highlights the interrelations among the physical, psychological, social, and creative aspects of movement, and emphasizes how development across all four domains can be supported through the interrelations of individuals and their contexts. In this paper, we introduce the 4D4D4All framework and present ideas for its application in research and practice. Specifically, this individualized, holistic, and inclusive approach to physical literacy is an alternative to models that emphasize the production of podium-driven athletes or focus on meeting physical activity guidelines, and is therefore better suited to facilitate the development of flourishing active people.

LAY SUMMARY

Current models of sport and physical activity participation do not adequately describe the developmental experiences of individuals moving in a variety of contexts. Our new physical literacy framework, Four Domains for Development for All (4D4D4All), enables all movement contexts to better support well-being through a focus on holistic individual development.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Practitioners in sport and physical activity settings should view their participants as whole people who engage in many types of active pursuits, both concurrently and across their life spans.

Experiences in movement contexts, including sport, should be intentionally designed to support development of physical literacy in ways that promote development across the physical, psychological, social, and creative domains.

Sport policy and physical activity promotion efforts should be based on holistic frameworks, like 4D4D4All, that recognize multiple pathways of participation and promote flourishing for all people, rather than focusing on international competitive success or standardized health metrics.

Movement is an important aspect of human life that takes place in a variety of ways within structured and unstructured settings (e.g., sport, exercise, performing arts, transportation, play). However, movement contexts are just some of the many interrelated contexts in which development takes place (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977), so research seeking to understand movement, and efforts to promote movement, should take a developmental and whole-person approach. Specifically, as emphasized in theories of human development, movement contexts do not simply impart benefits on their participants but rather participants and their movement contexts co-develop each other (Agans et al., Citation2013, Citation2016). The development of both individuals and communities is therefore predicated on the ways in which individuals and their movement contexts interrelate.

Unfortunately, the status quo is not reflective of mutually-beneficial relations between individuals and movement contexts. Many people elect not to engage in movement, as illustrated by declining levels of physical activity across the world (Rutter et al., Citation2019), and movement is often presented as a preventative health measure and a moral responsibility or moral imperative (Haskell et al., Citation2009) in public health campaigns whose rhetoric may be more harmful than helpful (Alexander & Coveney, Citation2013; Smith, Citation2016). Furthermore, many people have negative experiences in structured movement environments, such as physical education and sport, that can lead to negative valuation of movement and low self-efficacy (Ladwig et al., Citation2018; Säfvenbom et al., Citation2015; Simonton, Citation2021). Efforts to support increases in human movement should therefore focus on the processes (i.e., supporting positive or meaningful experiences; Agans et al., Citation2013; Beni et al., Citation2017) that could lead to flourishing through movement, not on simply making people be more active. VanderWeele (Citation2017) defines flourishing as a holistic approach to well-being, including physical and mental health, close social relationships, happiness and life satisfaction, character and virtue, and meaning and purpose in life. As such, an approach to movement that focuses on flourishing would seek to support people across diverse domains of functioning (i.e., promoting “a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good”; VanderWeele, Citation2017, p. 8149).

Many existing models of physical activity promotion, however, rely on utilitarian public health perspectives, positioning movement as a means to achieve physical health outcomes (e.g., the Transtheoretical Model, Prochaska & Velicer, Citation1997; Theory of Planned Behavior, Ajzen, Citation1991). These approaches medicalize movement in ways that may reduce its appeal (Dudley & Cairney, Citation2022; Smith, Citation2016). Meanwhile, models from sport research often serve organizations more concerned with developing high-performance athletes than developing flourishing active people (e.g., Long-Term Athlete Development, Balyi et al., Citation2013; Developmental Model of Sport Participation, Côté et al., Citation2007; Long-Term Development, Higgs et al., Citation2019), and applied sport psychology is often misconstrued as being relevant only for elite athletes (Association for Applied Sport Psychology, Citationn.d.; Sly et al., Citation2020). However, trying to promote elite performance and population-level physical activity at the same time may limit the ability of any intervention to do either well (Dowling et al., Citation2020), and both undervalue the importance of positive experiences (Agans et al., Citation2013) or meaningful experiences (Beni et al., Citation2017) in movement contexts. What is needed to support flourishing through movement is an approach that is individualized, holistic, and inclusive. Such an approach will be capable of acknowledging the role of unique person-context relations (Agans et al., Citation2016), attend to the development of the whole person (Stodden et al., Citation2021), recognize a given movement activity as just one of many interrelated contexts influencing development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977), welcome the full spectrum of abilities and interests (Dattilo, Citation2017; Jaarsma & Smith, Citation2018), and recognize the ways in which systemic inequities contribute to movement experiences (Camiré et al., Citation2021; Santos et al., Citation2022). Physical literacy has the potential to meet this need, if enacted through a framework that makes these aspects explicit.

Physical literacy

Physical literacy and health literacy are largely co-requisite for leading active healthy lives (Sorensen et al., 2012). Physical literacy is a multidimensional construct related to movement (Young et al., Citation2020) and has been described as a positive feedback process (Cairney et al., Citation2019, Jefferies et al., Citation2019) involving core elements common across all definitions (competence → confidence → motivation → active participation). This process explicitly takes place through the interrelations between a participant and their ecosystem of contexts (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977) by not only promoting physical activity but, ultimately, active participation in society. As such, physical literacy aims to equip people with the competencies and knowledge to participate across various movement settings (play, sport, recreation, performance arts, activities of daily living and vocation), across social contexts (different ages, different abilities, different cultures, etc.) and in different physical environments (land, air, water, ice and snow).

Physical literacy focuses more on the meaning and value of movement rather than the accumulation of time and intensity of activity (Whitehead, Citation2001), making it a useful means of promoting holistic flourishing (VanderWeele, Citation2017) through movement (cf. Cairney et al., Citation2019). In this regard, the physical literacy process has been expanded to integrate self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2012), enjoyment, and connectedness, all supporting the positive internal valuation of movement (Houser & Kriellaars, Citation2023). Indeed, there has been an evolution of the physical literacy construct from the early Canadian consensus statement (Tremblay et al., Citation2018) to the 2023 physical literacy consensus statement for England (Sport England, Citationn.d.) which highlights the importance of “our relationship with movement” through social, psychological (cognitive and affective) and physical domains. England’s recent consensus statement is wholly consistent with the various feedback arms identified in the physical literacy process (Houser & Kriellaars, Citation2023) and the generation of positive movement experiences through construction of positive challenges (Jeffries, Citation2020). For instance, being able to identify slippery or icy surfaces and avoiding negative outcomes by modifying walking behavior accordingly would require a cognitive “hazard detection” component, an ice walking physical competence, and the confidence to move on ice to experience the joy of such movement. Lacking competence and confidence to move on ice would have potential negative impacts in the social domain for community engagement during the winter. Ultimately, through development of physical literacy, people can develop a healthy risk perspective, which would entail a risk-neutral, balanced view of potential positive or negative outcomes that can arise in all physical and socio-cultural contexts based upon participants, observers, and community viewpoints for all temporal considerations from immediate to multi-generational.

The overall goal of physical literacy is the development of competencies and knowledge that lead to active participation in society with adequate safety. Although physical literacy can be the antecedent to becoming physically active, this activity is based upon intrinsic valuation of movement rather than instrumental valuations (meeting guidelines to avoid non-communicable disease). Based on this understanding of physical literacy, it is clear that physical literacy is (or should be) an individualized, holistic, and inclusive process (Dudley & Cairney, Citation2022). In fact, the Canadian consensus statement on physical literacy (Tremblay et al., Citation2018) includes five core principles that directly align with this vision. Specifically, the consensus statement indicates that physical literacy: 1) is an inclusive concept accessible to all; 2) represents a unique journey for each individual; 3) can be cultivated and enjoyed through a range of experiences in different environments and contexts; 4) needs to be valued and nurtured throughout life; and 5) contributes to the development of the whole person (Tremblay et al., Citation2018). In sum, physical literacy could serve as a unifying model for the promotion of healthy movement, but current applications of this model tend to rely on the traditional systems and therefore do not fulfill its potential for promotion of movement for all people (Dudley & Cairney, Citation2022; Edwards et al., Citation2017). A new framework for understanding and utilizing physical literacy must not only be individualized, holistic, and inclusive, but must also be used in this way in research and practice.

The 4D4D4All framework

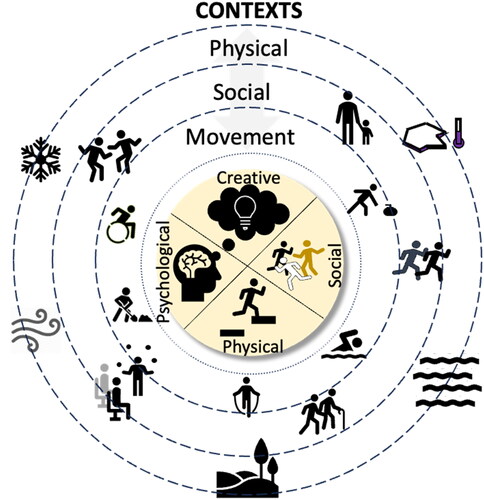

We propose a new framework to guide the application of physical literacy: Four Domains for Development for All (4D4D4All). This framework is centered on the individual and the ways in which experiences in movement contexts cumulatively contribute to development, highlighting the interrelation of the physical, psychological, social, and creative aspects of movement (see ). It also explicitly requires attention to the movement context itself and the ways in which the interrelations between participants and contexts contribute to the development of both the individual and their movement contexts. Although we recognize the context-specific utility of existing public health and sport performance models of physical activity, we argue that the adoption of the 4D4D4All framework for physical literacy in research, practice, and policy is more likely to both facilitate flourishing for individuals and support population health and social equity. As noted above, physical literacy is a process that is inherently individualized (Cairney et al., Citation2019, Jefferies et al., Citation2019), and should be understood in a holistic and inclusive way (Tremblay et al., Citation2018). However, contrary to recommendations, in practice it can be reduced to a strategy for increasing physical competence or physical activity to achieve benchmarks for public health and/or competitive performance (Edwards et al., Citation2017), rather than empowering skill-building that supports agentic engagement in movement across life (Gleddie & Morgan, Citation2021). We therefore propose the 4D4D4All framework to operationalize the application of physical literacy in ways that are consonant with its theoretical foundations. This framework is designed to guide researchers, practitioners, and policy makers through the diverse ways in which physical literacy can be enacted, and the variety of outcomes it can foster.

Figure 1. The four domains (creative, social, physical, and psychological) are situated in interrelated movement (play, sport, recreation, performance arts, activities of daily living, vocation), social (ages, abilities, cultures) and physical (snow, air, land, water, ice) contexts. The dotted line represents the notion of construction of positive challenges suitable for the contexts.

Specifically, 4D4D4All refers to four interrelated domains in which competencies can be developed: physical, psychological, social, and creative, and suggests that the integration of these domains can help to facilitate positive development through movement for all people. These domains differ somewhat from the four elements of physical literacy presented in the Canadian consensus statement (Tremblay et al., Citation2018) and elsewhere (e.g., Gleddie & Morgan, Citation2021): motivation and confidence (affective), physical competence (physical), knowledge and understanding (cognitive), and engagement in physical activity for life (behavioral). In the 4D4D4All framework, we view the behavioral element, active participation in society, as an outcome of the physical literacy process, and expand the physical domain to include not only physical competence but also other components of movement. We also group affective and cognitive aspects of movement into the psychological domain along with other psychological aspects of movement experiences. We then add the social domain (in alignment with the 2023 physical literacy consensus statement for England; Sport England, Citationn.d.) to highlight the importance of the social competencies and the social context, including facilitators and barriers to positive movement experiences. Finally, our addition of the creativity domain acknowledges the diverse ways in which individuals can engage with movement and the potential for micro- and macro-level innovation within movement contexts. As illustrated in the framework (see ), individual development within these four domains can be facilitated by supportive movement and social contexts, with each person creating and navigating a unique journey.

It is important to note that competence in each of these domains can be developed and expressed in all types of movement contexts. Movement contexts can be understood as microsystem elements within Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1977) ecological systems model; programs, activities, and the associated interrelations among individuals. However, movement contexts are also influenced by factors within the mesosystem (e.g., points of contact between a school basketball program and a travel team), the exosystem (e.g., media coverage of basketball players, league policies, etc.), the macrosystem (e.g., cultural ideas about the value of basketball), and the chronosystem (e.g., the role of basketball in the current moment in historical time and the life of the individual). The 4D4D4All framework thus has important implications for change in microsystem contexts, mesosystem operations, and exosystem and macrosystem policies and approaches. However, Bronfenbrenner’s later work (e.g., Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006) outlining the Process, Person, Context, Time (PPCT) bioecological model may be even more useful. Specifically, 4D4D4All suggests using movement experiences to develop competencies across the four domains (process) in order for individuals (person) to achieve goals that are personally meaningful to them (e.g., see Beni et al., Citation2017) within diverse movement contexts (context) across the life span (time). As such, rather than assuming universal goals of physical health, skill, or competitive success, 4D4D4All expands the concept of performance to include competence and confidence across all four domains. This framework also highlights the need to individualize the metrics for performance and success to create positive challenges (Jefferies, Citation2020) that inform unique, inclusive journeys for each individual and ultimately enable both communities and individuals to flourish. 4D4D4All thus enables physical literacy to be implemented in a way that considers diverse expressions of all people, taking into account physical, psychological, and socio-cultural characteristics and competencies of each individual and creatively adapting the context to support flourishing (as defined by VanderWeele, Citation2017).

Furthermore, the 4D4D4All framework emphasizes that, even though human movement is the process supporting development, the physical domain is not superior to the other three; advancement/progression in all four domains can occur through movement. provides examples of the types of competencies that can be developed within each domain and the ways in which movement contexts may support this development. The table also illustrates how supporting development in each domain can facilitate individualized, holistic, and inclusive development for all, thereby supporting flourishing people and communities. The following section expands on the information in by providing a brief overview of the four domains. Importantly, although we present key considerations for each domain separately, these domains should be understood as part of an interrelated system involving the other domains. This system functions differently for each participant in a given movement context and across the various movement contexts and social contexts in which each participant engages.

Table 1. Examples of components included in each of the four domains of the 4D4D4All framework, including illustrative examples across levels of the ecological system.

The four domains

The physical domain of the 4D4D4All model encompasses all physical development from movement experiences. Physical competencies enable physical activity which, with consistent participation, elicits a number of positive adaptations important for physical health and well-being (Cairney et al., Citation2019) and the maintenance of independence in older age (Jones et al., Citation2018). However, fitness and health are not necessarily the end-goals, but may be facilitators to support flourishing. For example, movement experiences may be used to connect with or attune to physical bodily sensations for the sake of self-connection (Klussman et al., Citation2022) and to develop a healthy risk perspective (Wyver et al., Citation2010). An important goal may be to gain a sense of safety in the body in movement contexts. These physical goals, along with others, reduce the emphasis on physical esthetic and performance goals and prioritize factors necessary for overall well-being, such as personal expression, identity, meaning-making (Chappell et al., Citation2021), self-esteem and self-connection (Gleddie & Morgan, Citation2021), which can support individuals to be able to make agentic decisions toward a meaningful life.

The psychological domain encompasses all mental processes including both cognition and affect, as well as overall mental health and well-being. Physical activity can improve mental health (Lubans et al., Citation2016; Pressman et al., Citation2009) and reduce symptoms of mental illness (Dale et al., Citation2019). Movement can be used as a source of fun, relaxation, self-connection, or contentment to enhance positive affect and life satisfaction at any age (e.g., Agans et al., Citation2013; Beni et al., Citation2017; Klussman et al., Citation2022; Pressman et al., Citation2009). Positive challenges can support the development of, for example, problem solving, decision making, and resilience (Jefferies, Citation2020). Competitive athletes may be at increased risk of mental health problems, overtraining, and over-identifying as an athlete (Schinke et al., Citation2018), and incorporating movement exercises with positive psychosocial goals may support overall wellbeing. These examples, along with the components already included in the physical literacy cycle (self-efficacy, confidence, and motivation) can enhance the value of movement experiences (Cairney et al., Citation2019; Dudley et al., Citation2017) and support flourishing.

Social development through movement experiences includes the development of interpersonal skills and prosocial behaviors, as well as identity, resilience, and agency within society. For example, participation in movement contexts has the potential to support connectedness, cooperation, relationships, social interactions, social self-concept, empathy, and other social skills (Jones et al., Citation2018; Shima et al., Citation2021; Zimmer et al., Citation2023). Unstructured (or self-structured) physical activities can support self-organization and collaboration (Säfvenbom et al., Citation2018), and movement experiences can also be constructed to support the development of prosocial behaviors, where interacting and moving cooperatively with people with diverse demographics and characteristics can promote more inclusive feelings (Camiré et al., Citation2021; Santos et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, the social domain also is affected by social structures that may facilitate or obstruct participation and inclusion. Movement opportunities should be available and accessible to all, including ensuring that individuals are able to navigate the necessary resources (Dattilo, Citation2017). Creating environments that foster social support from peers can promote ongoing active participation (e.g., Zimmer et al., Citation2023). The 4D4D4All framework recognizes that each individual has a unique journey, dictated in part by their social circumstances. Thoughtful construction of movement challenges that respect and celebrate diverse individual factors, and design of accessible and appropriate movement contexts, can help make sure that all people in a community can feel a sense of belonging in movement.

Creativity is a multidimensional construct that can be supported through a wide range of elements, including physical factors such as movement and available objects or spaces, psychological factors such as openness and risk perspective, and social factors such as trust and vulnerability (Richard et al., Citation2021). Creativity has been considered a personal enabler that supports development and success, and creative movement has been shown to particularly benefit well-being (Chappell et al., Citation2021; Fullagar, Citation2019) and to support people to adapt to life changes across the life span (Restrepo et al., Citation2019). Creativity is also associated with physical competency (Torrents Martín et al., Citation2015), and is more often examined within unstructured movement experiences, such as play, or less-structured activities, such as parkour, skateboarding (O’Loughlin, Citation2012) and performing arts (Chappell et al., Citation2021; Torrents Martín et al., Citation2015). In traditional sports with defined rules for engagement, creativity is essential to develop decision-making skills that allow the player to get out of difficult situations or make unexpected plays (Fardilha & Allen, Citation2020). Currently, not all contexts are designed to support the development of creativity, and changing a movement context to better incorporate creativity can be difficult (Rasmussen et al., Citation2022). We nevertheless view creativity as equal with the other three domains in its importance for enabling movement experiences to support holistic well-being and flourishing for participants. By supporting the development of creativity, movement contexts become resistant to controlling and/or coercive rhetorics and pedagogies that are commonly applied in physical activity contexts (Alexander & Coveney, Citation2013).

In sum, although movement in general, and the development of physical literacy in particular, has the potential to support flourishing, positive outcomes are not automatically derived. Instead, individual outcomes arise from the interrelations between the individual and their movement contexts (e.g., Agans et al., Citation2013, Citation2016; Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006) across all four of these domains, as depicted in and . This approach contrasts with more population-based models of sport and physical activity promotion (e.g., Balyi et al., Citation2013) by emphasizing the value of individuals creating their own unique pathways (Whitehead, Citation2001) and pursuing personal goals within the four domains, rather than only focusing on physical competencies and achievements. Instead of asking the question “how can we make these participants better athletes?” or “how can we enable these people to meet physical activity guidelines?” we ask, “how can this movement experience support each individual to progress toward fulfilling their unique potential in life?”. This reframing requires a holistic, integrated knowledge of the interrelations among all four domains within and across contexts (as shown in ), rather than a hyperfocus on the physical domain, and recognition of movement contexts as part of a larger ecological system (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977). This includes mesosystem relations among different microsystems where movement takes place and the ways in which developmental processes unfold for different people in different contexts across time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006). This reframing also highlights the fact that sport and other movement activities do not inherently provide good experiences and positive developmental outcomes for all participants (e.g., Agans et al., Citation2013; Battaglia et al., Citation2022), but that they can do so when designed and implemented thoughtfully. Applying the 4D4D4All framework can therefore enable research, programs, and policies to better meet the unique needs of individual participants and support their flourishing in a holistic and inclusive way.

Application of 4D4D4All

Positive movement experiences rely on the ways in which individuals perceive and engage with their movement contexts (Agans et al., Citation2013). Participants are influenced by both intentional and unintentional program features (Kirk, Citation1992), so movement contexts should be intentionally designed and regularly evaluated to best support flourishing (e.g., Gleddie & Morgan, Citation2021). Of note, this intentionality must take place across all levels of the ecological system (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977), including attention to macrosystem barriers such as ableism (e.g., Pushkarenko et al., Citation2023), exosystem and macrosystem barriers such as social exclusion (e.g., Spaaij et al., Citation2014), and the impact of chronosystem changes (e.g., historical events such as the Covid-19 pandemic). Applying the 4D4D4All framework can inform the creation and modification of spaces and programs, as well as the training of people to create such spaces and deliver such programs, where everyone can belong, develop, and flourish through movement.

Currently, many people do not identify as competent movers and may in fact avoid organized movement environments based on negative past experiences with shame, embarrassment, or bullying (e.g., Agans et al., Citation2013; Ladwig et al., Citation2018). Similarly, people’s engagement in movement can be influenced by more temporary factors such as illnesses, injury, scholastic demands, boredom, financial resources, and major life challenges such as moving, marriage, parenting, etc. (Dėdelė et al., Citation2022). The 4D4D4ALL framework acknowledges that a person’s participation in movement will likely involve multiple movement contexts in each phase of life, as well as exits, reentries, and new entries into movement contexts over time (e.g., Li et al., Citation2009). Program leaders and practitioners must therefore consider that individual participants will enter with their own physical, psychological, social, and creative profiles, including those marked by inactivity and differences in ability (e.g., Dattilo, Citation2017; Jaarsma & Smith, Citation2018; Marcus et al., Citation2000), and they must acknowledge cultural differences in movement and individual goals for participation (e.g., Camiré et al., Citation2021; Krane & Waldron, Citation2021; Muriwai et al., Citation2022). A person’s ability to participate in movement at any level of performance, and their interest in doing so, is affected by factors related to all four domains, including physical abilities (Dattilo, Citation2017), self-perceptions (Farmer et al., Citation2017), structural barriers (Hardcastle et al., Citation2018), and cultural values and norms (Ahmad et al., Citation2020; Davis & Phillips-Fein, Citation2018). All need to be considered in order to intentionally design contexts to support physical literacy and engagement in movement that facilitates flourishing. Such movement contexts must adapt to meet each individual at their starting point and support them to develop holistically from there. Doing so will require the provision of diverse affordancesFootnote1 for movement and adequate safety to enable opportunities for positive risk-taking without limiting an individual’s potential with surplus safety (Wyver et al., Citation2010), the latter of which pushes instead toward avoidance behaviors or constrained (“safe”) movements that fail to elicit the potential for joy that such experiences bring (Caillois, Citation1958).

Therefore, one way to support 4D4D4All in movement contexts is through the construction of positive challenges informed by programming or environmental design to engage the physical literacy cycle (Jefferies, Citation2020). Positive challenges are created by promoting goals with an appropriate level of challenge for each individual, which means they require effort and learning but are, in fact, achievable (Jefferies, Citation2020). Traditional systems of physical education, exercise, coaching generally focus on predetermined physical goals based on averages and standards and do not sufficiently support the development of all participants (e.g., Dudley & Cairney, Citation2022; Säfvenbom et al., Citation2015). Environments equipped with a variety of affordances can better support flourishing through individual development across the four domains by enabling the construction of positive challenges tailored to different goals and levels of ability. Designing movement contexts to include positive challenges and be intentionally accessible and welcoming to all can also further expand the landscape of affordances for participants. It is therefore important for the context to balance accessibility (enabling participation by a broad range of participants) and challenge (ensuring that there is an appropriate level of physical, psychological, social, and/or creative challenge for all individuals; Jefferies, Citation2020). Resources to facilitate movement should be available and accessible to all (Dattilo, Citation2017; Jaarsma & Smith, Citation2018), and accessibility should be considered across all four domains to facilitate meaningful (Beni et al., Citation2017) and positive movement experiences (Agans et al., Citation2013) for both people who are currently active and those who are not. All communities should enable people to access a variety of movement experiences at an appropriate level of challenge to contribute to flourishing.

Furthermore, although the physical domain is just one of the four domains in which movement can support positive development, the body is the primary environment through which individuals experience movement (e.g., Agans et al., Citation2013). Hence, movement contexts should support the participant to feel confident and comfortable in their body, and contexts should be intentionally designed for a variety of bodies to interact and flourish within them. Movement contexts should also provide adequate safety in all four domains. For example, a physically “risky” movement experience (e.g., risky play; Sandseter, Citation2009) can build not only technical skill, but also confidence, self-efficacy, decision-making skills, and healthy risk perspective (Jefferies, Citation2020; Sandseter, Citation2009). However, participants need access to the space, equipment, and adequate physical safety measures to enable them to explore new movements, as well as adequate psychological and social safety to feel comfortable to create and express movements that could potentially fail (Richard et al., Citation2021). This approach aligns with the expansion of applied sport psychology to consider factors such as organizational culture (Sly et al., Citation2020), and also applies to the promotion of positive and meaningful experiences in recreational or physical education contexts (e.g., Agans et al., Citation2013; Beni et al., Citation2017).

The 4D4D4All framework also diverges from a personal responsibility perspective on physical activity, and instead acknowledges that movement is facilitated (or hindered) by a system of interrelated factors including local infrastructure, national policies, and overarching paradigms (Rutter et al., Citation2019). To thoroughly apply 4D4D4All, widespread changes in physical activity promotion efforts (cf. Alexander & Coveney, Citation2013; Smith, Citation2016) will be needed, to better align with physical literacy (Dudley & Cairney, Citation2022). Design considerations specific to the context and community being served will also be needed to create inclusive and accessible contexts that enable all participants to flourish (Camiré et al., Citation2021; Santos et al., Citation2022). presents some examples of how the 4D4D4All approach is already reflected in practice.

Table 2. Successful implementation of physical literacy enriched programming or design are provided in the illustrative examples below. The primary characteristics outlined in the 4D4DALL framework are addressed in each example including considerations for each of the four domains, as well as an inclusive developmental pathway for a wide range of abilities.

The 4D4D4All framework is applicable across individuals’ engagement, disengagement, and re-engagement in movement experiences, allowing for a cyclical process of engagement and disengagement from particular movement contexts. “Push” and “pull” factors exist across all domains in the 4D4D4All framework, with individuals seeking movement contexts that support their needs at a given point in time (aligning with self-determination theory; Deci & Ryan, Citation2012) and provide challenges appropriate to their competencies in each domain (Jefferies, Citation2020). In particular, to engage in a new movement experience, an individual must be aware that a context exists, find it at least somewhat approachable and interesting, and perceive themselves to have the ability and opportunity to participate (Camiré et al., Citation2021; Santos et al., Citation2022). However, sustained participation in the same movement context is rare; people engage in different types of movement at different points in their life (e.g., Liechty et al., Citation2012). Disengagement can be related to negative movement experiences pushing them out, or a person may be drawn to new activities that inspire them to re-prioritize their time and discontinue prior activities (Agans et al., Citation2013; Battaglia et al., Citation2022; Li et al., Citation2009; Liechty et al., Citation2012). However, when people disengage from movement experiences, they retain some of what they gained (whether positive, neutral, or negative) and these competencies, confidence, motivation, creativity, etc. may carry forward to other movement experiences (e.g., Agans et al., Citation2013; Ferrara et al., Citation2021). Of note, competence transfer is not only limited to movement experiences, but may also occur between other life contexts as well (Pierce et al., Citation2017). As such, although people may disengage from a particular activity, achieving positive movement experiences through the construction of positive challenges nevertheless provides opportunities to flourish. By reducing the focus on sport performance or achieving standard levels of physical activity and instead promoting movement for its intrinsic value (Smith, Citation2016) movement contexts can become more inclusive, enabling each person to pursue their own developmental and movement goals including engaging, disengaging, and reengaging as appropriate.

Finally, application of the 4D4D4All framework in research and its connection to other theoretical approaches is also important. For example, the 4D4D4All framework could be applied in relation to research on social and emotional learning, which focuses on the development of emotion regulation and goal pursuit skills, identity, and social skills such as empathy and responsible decision-making (Payton et al., Citation2000). The 4D4D4All framework could also be applied in relation to practice-based models such as the UNESCO Quality Physical Education guidelines (McLennan & Thompson, Citation2015), the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2023), including reducing inequality and improving health and well-being, and the related Inner Development Goals (Inner Development Goals, Citation2023), including self-awareness, critical thinking, empathy, communication skills, and creativity. In addition, as previously noted, physical literacy is often utilized in a way that highlights the physical domain (Dudley & Cairney, Citation2022; Edwards et al., Citation2017) although it is actually more holistic in its theoretical conceptualization (Gleddie & Morgan, Citation2021; Tremblay et al., Citation2018; Whitehead, Citation2010). Better consideration of the ability of movement contexts to contribute to flourishing across the life span, as outlined in the 4D4D4All framework, is needed to provide a more individualized, holistic, and inclusive understanding of movement experiences. For example, one of the underlying premises of the 4D4D4All framework is the recognition that virtually all humans regularly experience movement across multiple contexts (e.g., in performing arts, Davis & Phillips-Fein, Citation2018; Kriellaars et al., Citation2019; active transportation, Wanner et al., Citation2012; physically active leisure-time pursuits, Säfvenbom et al., Citation2018; vocational physical activity, Tigbe et al., Citation2011; sport, Côté et al., Citation2007; Higgs et al., Citation2019). The 4D4D4All framework emphasizes that individual development may be influenced by experiences in each context, and that experiences in one context may contribute to experiences in another. This individualized approach accordingly requires the integration of concepts such as the daily diversity of movement and migration between movement contexts (i.e., new entries, exits, and reentries over the life course; Li et al., Citation2009). The 4D4D4All framework also reminds researchers and practitioners to consider physical literacy more holistically and inclusively (e.g., Pushkarenko et al., Citation2023), focusing on more than physical activity behavior or talent development. Compared to research and practice drawing on siloed models from public health or sport, utilizing this framework will better facilitate the development of flourishing active people.

Conclusion

The models currently used to examine participation in sport and physical activity do not adequately support understanding of the developmental experiences of individual people moving in a wide variety of contexts. While models that map normative pathways for participants from the perspective of sport (Balyi et al., Citation2013; Côté et al., Citation2007; Higgs et al., Citation2019) or physical activity (Ajzen, Citation1991; Prochaska & Velicer, Citation1997) may be useful for some purposes, they cannot be widely applied across all types of movement contexts. Physical literacy provides what should be a holistic approach, but in practice is often applied with an overemphasis on the physical aspects of movement experiences (Dudley & Cairney, Citation2022). A new approach is therefore needed to enable understanding and promotion of the development of active, flourishing people.

In this paper we proposed the 4D4D4All framework for physical literacy, which centers the individual and their experiences across the breadth of different movement contexts and across life. This framework includes four domains of functioning: physical, psychological, social, and creative, and posits that development in each of these domains occurs integratively and cumulatively across all the movement contexts in which the individual engages. The 4D4D4All framework encourages an individualized (moving away from nomothetic, population-based models of sport or exercise), holistic (accounting for all four domains, and acknowledging the person as more than just a participant), and inclusive (applying to all people, regardless of ability, and including those currently not involved in physical activity) approach to promoting flourishing through movement. The ability of the 4D4D4All framework for physical literacy to be used to foster positive development lies in its conscious integration of all four domains into every movement experience and across all contexts, such that each experience caters to the whole person. Applying 4D4D4All therefore requires the intentional design of movement environments and experiences to support the flourishing of all people. Practitioners and scientists need to consider all four domains in relation to both the characteristics of the person and their multiple movement contexts across the life course (Li et al., Citation2009), as well as how all these factors interrelate, to support positive development (Agans et al., Citation2013, Citation2016). Mobilization of this approach in research and practice is therefore an important step toward realizing social equity in communities through movement contexts that foster positive development for all.

Authors’ contributions

JPA, MIS, and DK conceptualized and drafted the manuscript, JC contributed critical insight and assisted with manuscript revision.

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Informed consent

Not applicable

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Not applicable

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Affordances are properties of environments that enable opportunities for interaction, dependent upon individual capabilities and perceptions (Gibson, Citation1982). Importantly, however, affordances are not derived only from objective properties of the context in which an individual is situated, but experienced relative to the individual’s perceptions of those properties (Gibson, Citation1982).

References

- Agans, J. P., Ettekal, A. V., Erickson, K., & Lerner, R. M. (2016). Positive youth development through sport: A relational developmental systems approach. In N. Holt (Ed.), Positive youth development through sport (pp. 34–44). Routledge.

- Agans, J. P., Säfvenbom, R., Davis, J. L., Bowers, E. P., & Lerner, R. M. (2013). Positive movement experiences: Approaching the study of athletic participation, exercise, and leisure activity through relational developmental systems theory and the concept of embodiment. In R. M. Lerner & J. B. Benson (Eds.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 45, pp. 261–286). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-397946-9.00010-5

- Ahmad, N., Thorpe, H., Richards, J., & Marfell, A. (2020). Building cultural diversity in sport: A critical dialogue with Muslim women and sports facilitators. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12(4), 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1827006

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alexander, S. A., & Coveney, J. (2013). A critical discourse analysis of Canadian and Australian public health recommendations promoting physical activity to children. Health Sociology Review, 22(4), 353–364. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2013.22.4.353

- Association for Applied Sport Psychology (n.d). About Sport & Performance Psychology. https://appliedsportpsych.org/about-the-association-for-applied-sport-psychology/about-sport-and-performance-psychology/

- Battaglia, A., Kerr, G., & Tamminen, K. (2022). A grounded theory of the influences affecting youth sport experiences and withdrawal patterns. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(4), 780–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.1872732

- Balyi, I., Way, R., Higgs, C. (2013). Long-Term Athlete Development. Human Kinetics. https://www.human-kinetics.co.uk/9780736092180/long-term-athlete-development

- Beni, S., Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2017). Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest, 69(3), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.) & R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). Wiley.

- Cairney, J., Dudley, D., Kwan, M., Bulten, R., & Kriellaars, D. (2019). Physical literacy, physical activity and health: Toward an evidence-informed conceptual model. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 49(3), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01063-3

- Caillois, R. (1958). Les jeux et les hommes [Games and men]. Gallimard.

- Camiré, M., Newman, T. J., Bean, C., & Strachan, L. (2021). Reimagining positive youth development and life skills in sport through a social justice lens. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(6), 1058–1076. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.1958954

- Chappell, K., Redding, E., Crickmay, U., Stancliffe, R., Jobbins, V., & Smith, S. (2021). The aesthetic, artistic and creative contributions of dance for health and wellbeing across the lifecourse: A systematic review. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 16(1), 1950891. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2021.1950891

- Côté, J., Baker, J., & Abernethy, B. (2007). Practice and play in the development of sport expertise. In Handbook of Sport Psychology. (pp. 184–202)John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Dale, L. P., Vanderloo, L., Moore, S., & Faulkner, G. (2019). Physical activity and depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in children and youth: An umbrella systematic review. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 16, 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2018.12.001

- Dattilo, J. (2017). Inclusive leisure services (4th ed.). Sagamore-Venture.

- Davis, C. U., & Phillips-Fein, J. (2018). Tendus and tenancy: Black dancers and the white landscape of dance education. In A. M. Kraehe, R. Gaztambide-Fernández, & B. S. Carpenter II (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of race and the arts in education (pp. 571–584). Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65256-6_33

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. In Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 416–436). Sage Publications Ltd.

- Dėdelė, A., Chebotarova, Y., & Miškinytė, A. (2022). Motivations and barriers towards optimal physical activity level: A community-based assessment of 28 EU countries. Preventive Medicine, 164, 107336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107336

- Dowling, M., Mills, J., & Stodter, A. (2020). Problematizing the adoption and implementation of Long-Term Athlete Development “models”: A Foucauldian-inspired analysis of the Long-Term Athlete Development framework. Journal of Athlete Development and Experience, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.25035/jade.02.03.03

- Dudley, D., & Cairney, J. (2022). How the lack of content validity in the Canadian assessment of physical literacy is undermining quality physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 1(aop), 1–8.

- Dudley, D., Cairney, J., Wainwright, N., Kriellaars, D., & Mitchell, D. (2017). Critical considerations for physical literacy policy in public health, recreation, sport, and education agencies. Quest, 69(4), 436–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1268967

- Edwards, L. C., Bryant, A. S., Keegan, R. J., Morgan, K., & Jones, A. M. (2017). Definitions, foundations and associations of physical literacy: a systematic review. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 47(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0560-7

- Fardilha, F. D. S., & Allen, J. B. (2020). Defining, assessing, and developing creativity in sport: A systematic narrative review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 104–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2019.1616315

- Farmer, O., Belton, S., & O’Brien, W. (2017). The relationship between actual fundamental motor skill proficiency, perceived motor skill confidence and competence, and physical activity in 8–12-year-old Irish female youth. Sports, 5(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports5040074

- Ferrara, P. M. M., Zakrajsek, R. A., Eckenrod, M. R., Beaumont, C. T., & Strohacker, K. (2021). Exploring former NCAA Division I college athletes’ experiences with post-sport physical activity: A qualitative approach. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 35(2), 244–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.1996482

- Fullagar, S. (2019). A physical cultural studies perspective on physical (in)activity and health inequalities: The biopolitics of body practices and embodied movement. Revista Tempos e Espaços em Educação, 12(28), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.20952/revtee.v12i28.10161

- Gibson, E. J. (1982). The concept of affordances in development: The renascence of functionalism. In W. A. Collins (Ed.), The concept of development: The Minnesota symposia on child psychology (Vol. 15, pp. 55–81). Psychology Press.

- Gleddie, D. L., & Morgan, A. (2021). Physical literacy praxis: A theoretical framework for transformative physical education. Prospects, 50(1-2), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09481-2

- Hardcastle, S. J., Maxwell-Smith, C., Kamarova, S., Lamb, S., Millar, L., & Cohen, P. A. (2018). Factors influencing non-participation in an exercise program and attitudes towards physical activity amongst cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(4), 1289–1295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3952-9

- Haskell, W. L., Blair, S. N., & Hill, J. O. (2009). Physical activity: Health outcomes and importance for public health policy. Preventive Medicine, 49(4), 280–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.05.002

- Higgs, C., Way, R., Harber, V., Jurbala, P., & Balyi, I. (2019). Long-term development in sport and physical activity 3.0. Sport for Life Society.

- Houser, N., & Kriellaars, D. (2023). Where was this when I was in Physical Education?” Physical literacy enriched pedagogy in a quality physical education context. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1185680. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1185680

- Inner Development Goals. (2023). Inner development goals: Transformational skills for sustainable development. https://www.innerdevelopmentgoals.org/

- Jaarsma, E. A., & Smith, B. (2018). Promoting physical activity for disabled people who are ready to become physically active: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 37, 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.08.010

- Jefferies, P. (2020). Physical literacy and resilience: The role of positive challenges. Sciences & Bonheur, 5, 11–26.

- Jefferies, P., Ungar, M., Aubertin, P., & Kriellaars, D. (2019). Physical literacy and resilience in children and youth. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 346. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00346

- Jones, G. R., Stathokostas, L., Young, B. W., Wister, A. V., Chau, S., Clark, P., Duggan, M., Mitchell, D., & Nordland, P. (2018). Development of a physical literacy model for older adults–a consensus process by the collaborative working group on physical literacy for older Canadians. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0687-x

- Klussman, K., Curtin, N., Langer, J., & Nichols, A. L. (2022). The importance of awareness, acceptance, and alignment with the self: A framework for understanding self-connection. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 18(1), 120–131. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.3707

- Krane, V., & Waldron, J. J. (2021). A renewed call to queer sport psychology. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 33(5), 469–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1764665

- Kirk, D. (1992). Physical education, discourse, and ideology: Bringing the hidden curriculum into view. Quest, 44(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.1992.10484040

- Kriellaars, D. J., Cairney, J., Bortoleto, M. A. C., Kiez, T. K. M., Dudley, D., & Aubertin, P. (2019). The impact of circus arts instruction in physical education on the physical literacy of children in grades 4 and 5. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 38(2), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2018-0269

- Ladwig, M. A., Vazou, S., & Ekkekakis, P. (2018). My best memory is when I was done with it”: PE memories are associated with adult sedentary behavior. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine, 3(16), 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1249/TJX.0000000000000067

- Li, K.-K., Cardinal, B. J., & Settersten, R. A. (2009). A life-course perspective on physical activity promotion: Applications and implications. Quest, 61(3), 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2009.10483620

- Liechty, T., Yarnal, C., & Kerstetter, D. (2012). I want to do everything!’: Leisure innovation among retirement-age women. Leisure Studies, 31(4), 389–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.573571

- Lubans, D. R., Richards, J., Hillman, C., Faulkner, G., Beauchamp, M., Nilsson, M., Kelly, P., Smith, J., Raine, L., & Biddle, S. J. H. (2016). Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics, 138(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1642

- Marcus, B. H., Forsyth, L. H., Stone, E. J., Dubbert, P. M., McKenzie, T. L., Dunn, A. L., & Blair, S. N. (2000). Physical activity behavior change: Issues in adoption and maintenance. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 19(1S), 32–41. Suppl), https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.32

- McLennan, N., & Thompson, J. (2015). Quality physical education (QPE): Guidelines for policy makers. Unesco Publishing.

- Muriwai, E., Manuela, S., Cartwright, C., & Rowe, L. (2022). Māori exercise professionals: Using indigenous knowledge to connect the space between performance and wellbeing. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 35(1), 83–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2075982

- O’Loughlin, A. (2012). A door for creativity – Art and competition in parkour. Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, 3(2), 192–198.

- Pierce, S., Gould, D., & Camiré, M. (2017). Definition and model of life skills transfer. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 186–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1199727

- Pressman, S. D., Matthews, K. A., Cohen, S., Martire, L. M., Scheier, M., Baum, A., & Schulz, R. (2009). Association of enjoyable leisure activities with psychological and physical well-being. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(7), 725–732. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ad7978

- Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP, 12(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

- Pushkarenko, K., Howse, E., & Gosse, N. (2023). Individuals experiencing disability and the ableist physical literacy narrative: critical considerations and recommendations for practice. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1171290. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1171290

- Rasmussen, L. J. T., Glăveanu, V. P., & Østergaard, L. D. (2022). The principles are good, but they need to be integrated in the right way”: Experimenting with creativity in elite youth soccer. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(2), 294–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1778135

- Restrepo, K., Arias-Castro, C., & López-Fernández, V. (2019). A theoretical review of creativity based on age. Psychologist Papers, 40(2), 125–132.

- Richard, V., Holder, D., & Cairney, J. (2021). Creativity in motion: Examining the creative potential system and enriched movement activities as a way to ignite it. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 690710. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.690710

- Rutter, H., Cavill, N., Bauman, A., & Bull, F. (2019). Systems approaches to global and national physical activity plans. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 97(2), 162–165. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.220533

- Säfvenbom, R., Haugen, T., & Bulie, M. (2015). Attitudes toward and motivation for PE. Who collects the benefits of the subject? Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(6), 629–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2014.892063

- Säfvenbom, R., Wheaton, B., & Agans, J. P. (2018). How can you enjoy sports if you are under control by others?’ Self-organized lifestyle sports and youth development. Sport in Society, 21(12), 1990–2009. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1472242

- Sandseter, E. B. H. (2009). Children’s expressions of exhilaration and fear in risky play. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 10(2), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2009.10.2.92

- Santos, F., Newman, T. J., Aytur, S., & Farias, C. (2022). Aligning physical literacy with critical positive youth development and student-centered pedagogy: Implications for today’s youth. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 845827. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.845827

- Schinke, R. J., Stambulova, N. B., Si, G., & Moore, Z. (2018). International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(6), 622–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1295557

- Shima, T., Tai, K., Nakao, H., Shimofure, T., Arai, Y., Kiyama, K., & Onizawa, Y. (2021). Association between self-reported empathy and sport experience in young adults. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 21(1), 66–72.

- Simonton, K. L. (2021). Testing a model of personal attributes and emotions regarding physical activity and sedentary behaviour. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 19(5), 848–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1739112

- Sly, D., Mellalieu, S. D., & Wagstaff, C. R. (2020). It’s psychology Jim, but not as we know it!”: The changing face of applied sport psychology. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 9(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000163

- Smith, A. (2016). Exercise is recreation not medicine. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 5(2), 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.03.002

- Sørensen, K., Van den Broucke, S., Fullam, J., Doyle, G., Pelikan, J., Slonska, Z., & Brand, H, & (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European (2012). Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80

- Spaaij, R., Magee, J., & Jeanes, R. (2014). Sport and social exclusion in global society. Routledge.

- Sport England. (n.d). Our physical literacy consensus statement for England. Retrieved from https://www.sportengland.org/funds-and-campaigns/children-and-young-people?section=physical_literacy

- Stodden, D., Lakes, K. D., Côté, J., Aadland, E., Brian, A., Draper, C. E., Ekkekakis, P., Fumagalli, G., Laukkanen, A., Mavilidi, M. F., Mazzoli, E., Neville, R. D., Niemistö, D., Rudd, J., Sääkslahti, A., Schmidt, M., Tomporowski, P. D., Tortella, P., Vazou, S., & Pesce, C. (2021). Exploration: An overarching focus for holistic development. Brazilian Journal of Motor Behavior, 15(5), 301–320. https://doi.org/10.20338/bjmb.v15i5.254

- Tigbe, W. W., Lean, M. E. J., & Granat, M. H. (2011). A physically active occupation does not result in compensatory inactivity during out-of-work hours. Preventive Medicine, 53(1-2), 48–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.04.018

- Torrents Martín, C., Ric, Á., & Hristovski, R. (2015). Creativity and emergence of specific dance movements using instructional constraints. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038706

- Tremblay, M. S., Costas-Bradstreet, C., Barnes, J. D., Bartlett, B., Dampier, D., Lalonde, C., Leidl, R., Longmuir, P., McKee, M., Patton, R., Way, R., & Yessis, J. (2018). Canada’s physical literacy consensus statement: process and outcome. BMC Public Health, 18(Suppl 2), 1034. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5903-x

- United Nations (2023). The 17 goals. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- VanderWeele, T. J. (2017). On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(31), 8148–8156. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702996114

- Wanner, M., Götschi, T., Martin-Diener, E., Kahlmeier, S., & Martin, B. W. (2012). Active transport, physical activity, and body weight in adults: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(5), 493–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.030

- Whitehead, M. (2001). The concept of physical literacy. European Journal of Physical Education, 6(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/1740898010060205

- Whitehead, M. (2010). Physical literacy throughout the lifecourse. Routledge.

- Payton, J. W., Wardlaw, D. M., Graczyk, P. A., Bloodworth, M. R., Tompsett, C. J., & Weissberg, R. P. (2000). Social and emotional learning: A framework for promoting mental health and reducing risk behavior in children and youth. The Journal of School Health, 70(5), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06468.x

- Wyver, S., Tranter, P., Naughton, G., Little, H., Sandseter, E. B. H., & Bundy, A. (2010). Ten ways to restrict children’s freedom to play: The problem of surplus safety. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 11(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2010.11.3.263

- Young, L., O’Connor, J., & Alfrey, L. (2020). Physical literacy: A concept analysis. Sport, Education and Society, 25(8), 946–959. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1677586

- Zimmer, C., McDonough, M. H., Hewson, J., Toohey, A. M., Din, C., Crocker, P. R., & Bennett, E. V. (2023). Social support among older adults in group physical activity programs. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 35(4), 658–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2055223