Abstract

Burgess et al. (Citation2016) emphasized the importance of parental support in youth sports as they provide financial, informational, and emotional support to the youth-athlete. Parents also play a “significant role in shaping youth sport experiences” (Sheridan et al., Citation2014, p. 198). Research around parental support has been conducted in sports such as tennis, gymnastics, and football. The aim of the present study was to examine the parents’ perspective of parental support in female youth golf, exploring how they support their female youth golfers, and if the support changes through their child’s development. Twenty-two semi structured interviews were conducted with parents (14 fathers, 10 mothers) of high-performance female golfers in the specializing or investment stages of Côté’s (Citation1999) DMSP. Participants were recruited from six countries (England, Ireland, Scotland, New Zealand, Australia, Canada). Using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012) six higher order themes were identified, namely, parental support: emotional, practical, technical, financial, organizational, and reflective support. The results align with the grounded theory of parental support (Burke et al., Citation2023a) providing an insight into the parents’ perspective of providing support aligning with informational, emotional, and instrumental support of the theory. Furthermore, the current research presented novel findings regarding reflective support that parents provide. Findings highlighted that parental support changed depending on temporal differences (place in the golf season) and their daughter’s development. The present research reinforces the need to provide support programs for parents based on their needs, rather than programs designed from a governing body or coaches perspective.

Lay summary

Parents perspective of parental support and associated temporal changes were explored in female youth golf. Six themes of support were identified: emotional, practical, technical, financial, organizational, and reflective support. Changes in parental support were dependent on their daughter’s development (level of maturity or level of play) and the time of year differences.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Sport psychologists can build upon the current findings when assisting the development of youth athletes, by involving the parent in managing emotions for their child-athlete but also providing some help for how parents may manage their own emotions to avoid having a negative impact on their youth athlete.

Findings can be applied by practitioners, governing bodies, and sporting organizations to develop and implement suitable assistance for parents based on the needs of parents and to assist with the changes in support that occur when supporting their youth athlete.

Introduction

Parental support has previously been defined as the youth athlete’s perception of their parents’ “behavior aimed at facilitating his or her involvement and participation in sport” (Leff & Hoyle, Citation1995, p. 190). Knight (Citation2019) suggested parental support, contributing factors of involvement, and strategies to encourage positive parental involvement, are the three key strands gaining current researcher attention. Parental support in youth sport represents providing essential financial, informational, and emotional support to their child-athlete (Burgess et al., Citation2016; Burke et al., Citation2023a; Rees & Hardy, Citation2000). Burke et al. (Citation2023a) developed a grounded theory of parental support constructed around the core category of ‘individual parental support preferences’ underpinned by instrumental, informational, emotional, and autonomy support (see Burke et al., Citation2023a for full review). As such, parents play a “significant role in shaping youth sport experiences” (Sheridan et al., Citation2014, p. 198). In contrast to positive support roles, media attention often focuses on the negative behaviors and involvement of parents in sport (Burke et al., Citation2023b; Knight, Citation2019). Dangi and Witt (Citation2018) highlighted how pressure and criticism from parents to overachieve can diminish the desire to continue for youth athletes. As a result of this added pressure, youth athletes can develop higher levels of anxiety, lower motivation, and fear of failure, that may eventually lead to sport dropout (Dangi & Witt, Citation2018). More recently, Burke et al. (Citation2023b) highlighted the athlete’s perspective of unsupportive behaviors from parents which included pressurizing behaviors, emotional ill-treatment, and in some cases physical ill-treatment (see Burke et al., Citation2023b for full review). Therefore, it is important for parents to understand and recognize the appropriate support needs at the different stages of participation.

Côté’s (Citation1999) 'developmental model of sport participation’ (DMSP) explores the psychosocial and physical factors affecting the participation of youths in sport and the role parents can play within these stages. The model incorporates three stages of development based on age range, sampling (aged 6–12), specializing (aged 13–15), and investment years (aged 16 and above). Ericsson et al. (Citation1993) suggest during the specializing and investment years, the activities youth athletes invest their time in do not immediately show results and hard work is required to improve and compete at a higher level. More recently, Côté and Vierimaa (Citation2014) revised the DMSP, highlighting it should be acknowledged that there are different “pathways” children (and their parents) pursue, based on the sport-related goals (recreation or elite performance), that can lead them to stray from the prescribed age windows outlined in the original model. Côté (Citation1999) highlighted the importance of the role of significant others, including parents, peers, and coaches, and the impact they can have on continuing youth participation in sport across the different ages and stages to promote positive youth development.

Woodcock et al. (Citation2011) indicated that parents perceived that they offered positive support for their child athletes by helping them to understand their performances. However, parents were unclear about the timing of this support, particularly if their child athlete had a poor performance. This can be challenging for parents and may lead youth athletes to assume that this support is in fact criticism if not provided at the correct time. It is important to consider the timing of support during the different stages of Côté’s (Citation1999) model as well as the maturation of the youth athlete in order to ensure they do not perceive intended support as unsupportive criticism. Providing parental support can be complex, the timing of support must consider the development stage of the athlete (i.e., specializing or investment stage), in addition to the context of the situation (i.e., before, during or after competition) (Burke et al., Citation2023b; Elliott & Drummond, Citation2017). Woodcock et al. (Citation2011) emphasized that parents felt it was their responsibility to support their child in maintaining perspective, and manage other commitments such as other sports, work, or school. However, Lauer et al. (Citation2010) argued that parents behaviors begin to change as athletes became more competitive, conflicts arise with mounting pressure to perform well from controlling and pushy behaviors displayed by parents. These findings highlighted that parents’ behaviors began to negatively impact the athlete as they developed through stages and resulted in parents becoming less involved.

Whilst research around parental support has been conducted in individual sports such as tennis (Knight et al., Citation2011), and gymnastics (Burgess et al., Citation2016), there is a lack of research exploring parental support in golf, specifically in female youth athletes. Furthermore, there is a need to explore parents’ perspectives of positive support through the specializing and investment stages of Côté’s (Citation1999) “developmental model of sports participation.” The R&A, the leading body within the world of golf, governs 143 countries worldwide for the sport of golf, with the Ladies Golf Union merging with the R&A in 2017. Research conducted by Fry and Hall (Citation2018) on behalf of the R&A highlighted the role parents play in golf as vitally important, and more crucial than many other sports. Golf differs from other individual sports as the interaction between parents and their child can become intense with some tournaments lasting from three to five days. Tournaments allow for continued interaction between athlete and parent with a lot of idle time spent together. Research focused on the retention of female golf athletes highlighted a correlation with positive parental emotional support (Williams et al., Citation2013). Conversely, Cohn (Citation1990) discovered parental pressure to be a significant factor in burnout and drop out of youth golf athletes. Williams et al. (Citation2013) reinforced these findings, reporting that overinvolvement or no interaction reported by female golfers who no longer participate, was a source of stress. However, little is known about the parent’s perspective and support role needs of parents within golf. Family golf participation, including women’s and girls’ involvement in particular, has been identified as an opportunity for significant growth (Fry & Hall, Citation2018). Globally, Syngenta (Citation2014) revealed that women on average represent just 24% of the overall golf participation. Subsequently, the “Women in Golf Charter” was established along with the #FOREeveryone campaign in 2018. The aim of the charter and campaign is to increase participation of women and girls and allow them to flourish and maximize their potential in golf. Therefore, the rationale for selecting parents of female golfers is directly linked to the R&A “Women in Golf Charter” (2018), reflective of their aim to improve parental support and engagement for the increased participation of female golfers.

Results involving the child-athlete highlighted that parents and athletes had differing views in relation to parental support (Clarke & Harwood, Citation2014). Although there is a plethora of literature exploring parental support in youth sports, Holt and Knight (Citation2014) highlighted the need for a deeper understanding of parenting in sport by developing an understanding of the parent’s experiences. Furthermore, Dorsch et al. (Citation2019) argued a need for “listening to parents voices” when considering the impact of parental support on youth athletes development, in addition to the impact this has on both parent and athlete. Based on the current literature and research recommendations, the research aims for the current investigation were to (1) explore how parents support their female youth golfers; and (2) explore how the support from parents of female youth golfers changes through their child’s development.

Method

Research design and philosophical position

The current study adopted a pragmatic philosophical position. Morgan (Citation2014) highlights that a pragmatic approach suggests individuals’ knowledge is socially constructed and reliant on individual interactions and experiences. Furthermore, Creswell and Creswell (Citation2018) highlight that the emphasis is placed on the research question when conducting research from a pragmatic perspective. In line with the pragmatic approach, the current study utilized the research questions to develop the research design by selecting qualitative research methods. The current study employed a qualitative individual interview approach which focuses on the ways in which people interpret and make sense of their experiences, and allows for a greater understanding of the experiences, motivations, and beliefs of the participants involved (Hastie & Hay, Citation2012). Within the current investigation, individual interviews were carried out in a semi-structured manner as they provide rich insight into parents’ perspectives of supporting their female youth golfer.

Participants

The participants involved in this study were purposefully sampled as parents of female youth golfers in the specializing and investment years (aged 13–17 years). The selection criteria for parents included their child’s sport (golf), gender (female), level of play (part of a national high-performance team or national development pathway) and their development stage (specializing or investment). 24 parents (n = 14 fathers, n = 10 mothers) from England (n = 7), Ireland (n = 7), Scotland (n = 3), Canada (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 2), and Australia (n = 2) volunteered as these countries’ golfing governing bodies had participated in earlier research studies exploring parental support in competitive youth golf (Burke et al., Citation2023a, Citation2023b). The above selection criteria based on their child-athlete, is in line with Côté’s (Citation1999) model as parents support role needs are greater in the second two stages with athletes becoming more competitive and invested in a particular sport. Whilst participants were recruited from six countries, one parent originated from Korea (residing in New Zealand), and another from Argentina (residing in Canada).

Procedure

Once institutional ethical approval was granted, High-Performance Directors from National Governing Bodies (NGBs) were contacted via email with the description of the research study. The recruitment from these specific countries provided a significant opportunity to extend the current body of literature beyond the United Kingdom and North America (Gould et al., Citation2008). NGBs were asked to identify parents with female youth golfers in either the specializing or investment years of development (aged 13–18 years old). Parents who volunteered and met the sampling criteria were then recruited for the study. The NGB liaised with the participants directly via email and provided them with the participant information sheet and consent form. Once participants had highlighted their interest in the study, their details were then passed to the researcher to allow for scheduling of the online interview. Prior to the collection of any data, participants had to complete and return the consent form, which was mandatory, however participants were advised that they could also withdraw if they wish at any point during the study.

Data collection

Interviews were carried out online using Microsoft Teams. A private individual meeting link was sent to each participant so that only invited participants could join the interview. Twenty-two online interviews were conducted with parents of female youth golfers. Two interviews included both mother and father of the female golfer as both felt they played an equal part in providing support for their daughter. The interviews were led by the primary researcher and ranged from 45 minutes to 114 minutes (M = 72 min). Foundations for the interview guide were drawn from the current literature on youth sport parenting (Clarke & Harwood, Citation2014; Knight et al., Citation2011) and questions were aligned with the research aims of the current study. A pilot interview was conducted to test the interview guide, with no amendments made, the pilot interview data was included in the overall results and analysis. Following the completion of data collection, interviews were transcribed verbatim, which yielded 416 transcript pages of single-spaced text.

Data analysis

Pragmatists postulate that the human experience is an everchanging process whereby beliefs are interpreted to choose actions for the current conditions, based on their consequences (Morgan, Citation2014). This approach aligns with the pragmatic perspective where the objectives of the current study guided the choice of the research approach and methods used for analysis (i.e., exploring parents’ perceptions of parental support and the changes in parental support). Thematic data analysis was adopted to present data in a consistent manner and be thoughtfully analyzed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). The primary researcher followed the six-phase approach set out by Braun and Clarke (Citation2012) to present the findings logically and to ensure data produced was credible and consistent (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). First, the primary researcher familiarized themselves with the data by transcribing, reading, and re-reading the interview transcripts, taking note of potential concepts. Second, initial codes were produced which “identify and provide a label for a feature of the data that is potentially relevant to the research question” (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012, p. 61). The third phase known as “searching for themes” involved reviewing the coding from the previous phase and identifying similarities to create an overarching theme (e.g., lower order themes of positive body language and positive encouragement were merged under “just being there” within emotional support). In phase four and five, themes were reviewed by the research team, defined, and given a name to ensure they are related but are not repetitive and clearly address the research questions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). For example, the research team differentiated practical and organizational support by defining organizational support as the “planning” aspects of support and the practical support as the tasks required after planning such as being the taxi driver and videoing. Finally, data extracts were then selected which clearly reflect the essence of the themes and provided a logical and meaningful analysis of the data. Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2012) guidelines for thematic analysis assisted the researchers with regard to rigor by following the step-by-step process to enhance the quality of the research.

Quality criteria

The research team implemented criteria based on the specific research objectives and the methodological approach (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). The worthiness of the topic was demonstrated by the lack of substantial research exploring parental support within youth golf as previously discussed in the introduction. To promote reflexivity, the primary researcher kept detailed notes regarding thoughts and reflections on the research activities. Furthermore, the research team served as “critical friends” (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018) by providing regular critical feedback throughout the data collection and analysis process to help identify and develop themes and encourage continuous reflection. For example, the primary researcher collated the data analysis and presented it to the research team. The whole research team then critically discussed in detail each lower order theme looking at specific examples to ensure overarching themes were presented logically while adhering to Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2012) guidelines for analysis.

Results

The present findings are categorized into two sections. The first reports the support provided by parents of female youth golfers’, and second discusses the changes in support.

Types of parental support

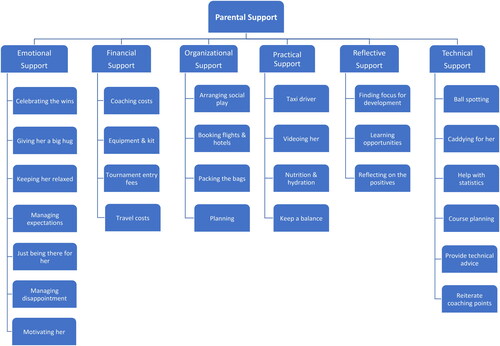

When providing support to their child-athlete, six types of support were identified (1) emotional support, (2) financial support, (3) organizational support, (4) practical support, (5) reflective support, and (6) technical support. Within each high-order theme, were lower-order themes providing additional detail of how they specifically supported their child-athlete within each type of support ().

Emotional support

Emotional support was identified as just being there for her, celebrating the wins, helping her to manage expectations and disappointments, and motivating her. Parent 7 commented that “emotionally it’s kind of building an environment where they feel safe and secure so they can compete to the best of their ability.” Similarly, Parent 16 described providing this emotional support as “I’m her punching bag if she needs a punching bag. I’m her sunshine if she needs some rays of sunshine.” Parents highlighted the importance of celebrating the wins, as Parent 24 commented, “when the good times come, you have to enjoy them. Because in high level sport, there’s going to be a lot more downs than there are ups.” Furthermore Parent 6 described: “I’d give her a hug anyway. And that hug might be saying a well done or it might be just a hug that, you know, is just as she needs a hug because she’s feeling like she’s crying inside.” The emotional support of giving their daughter a hug was non-negotiable regardless of the outcome of their daughters’ performance. Similarly, just being there for her was highlighted to be a type of emotional support that parents felt was an important aspect. As Parent 16 described, “Just being able to listen is massive for them when they’re playing a tournament. Not that you need to say anything, just to let them vent, is very good support for them I think.”

Just being there for her was categorized into two further sub-themes (1) positive body language, and (2) positive encouragement. Parent 4 highlighted the importance of providing positive body language particularly at golf tournaments: “When they’re competing, you shouldn’t really have any contact with them, that’s the rules and you’ve got to try and get it across somehow. Just whether it’s facial expressions.” Furthermore, Parent 7 discussed how critical positive encouragement is both before and after a round: “It’s just trying to pick out the good things that they did or that happened, or a bit of bad luck and just trying to pick them back up again.” This was evident during tournaments when parents tried to provide positive encouragement in between rounds.

Emotional support also involved helping their daughter manage her expectations as Parent 2 discussed: “She always expects to go and shoot the lights out, but there are a hundred different reasons why that won’t always happen. And managing that before she goes out is often a good thing then if she exceeds it.” Furthermore, Parent 17 also described the difficulty with golf that “by definition you are very rarely satisfied with your result, even if you’re sitting in first place one or two strokes ahead. You’ll remember that you could have probably done two strokes better or something like that.” Parents also discussed the importance of helping their daughter manage disappointment. Parent 9 stated, “you’re sort of trying to read the situation like if she’s ready to burst into tears, there’s no point me turning around saying, well, that was terrible. She knows it was terrible. That’s why she’s about to burst into tears.” Giving their daughter space was also discussed by parents. Parent 1 commented, “you’ve got to learn to give her space to reflect and sort this out in their own mind before you sort of jump in and start getting involved in this discussion.”

Parents also discussed if they felt they could not fix the problem themselves, they looked to provide alternative practical solutions. Parent 1 discussed: “I looked at Red to Blue really to see if I could give her some tools to manage her emotions.” When parents were unable to provide technical support, they looked for alternative solutions, as Parent 6 explained:

“I don’t know what to say, so all I could do was suggest that after we’d finished the practice round, we went and found a driving range because there was no range there to practice that. What I can do is look up somewhere locally to go find a driving range that we can then go to.”

Parents stressed the importance of fun regardless of age or level of play. Parent 21 commented, “the biggest thing has to be fun. The biggest thing, I don’t care about others, it’s the biggest thing.” At tournaments parents were consistent with their messaging around the place of fun and enjoyment. As Parent 7 described:

“Allowing them to just have a bit of fun when they go to the competitions because they don’t have a lot of fun in the elite athlete environment. They don’t have a lot of fun at school, they’ve got to study, then they’ve got to run off and train. So, it is difficult. It’s quite nice for them just to be with their friends and I think it’s that emotional support really is the most important thing.”

“Normally we make a weekend of it, you know, go to a nice hotel. So, she gets the balance. She gets the downtime It’s not all about the golf. It’s all about the experience. And at her age, it’s about the enjoyment of it.”

Financial support

Financial support was provided by parents throughout the year to support their daughters’ golf. This support included coaching costs, equipment and kit, tournament entry fees, and travel costs. Parent 6 encapsulated financial support as “everything comes back to the bank of mum and dad.” Parent 11 discussed “I pay for pretty much everything. She’s my whole social life plus most of my finances go to my daughter if I’ve been honest.”

Parent 2 discussed the financial support needed within golf when spending money on equipment as “Daughter 2 went through another growth spurt and, clubs are thousands of pounds each time, because they’re so good. They need to be custom fit.” Some financial aspects of support may not seem like a lot of money, but the build-up equates to larger sums across the year as Parent 19 discussed coaching costs, “if it’s a good coach it’s going to cost more. Now interesting enough, coaching may not be the most expensive, but it’s the most repetitive part. It’s the one that we have to pay every month.”

Furthermore, parents voiced their concerns with the sum of money they spend each year on golf, ensuring it doesn’t impact their daughter as a result as Parent 16 stated “you have to be very careful about how you stipulate and try not to talk about the monetary side because that’s something that sits in the back of their heads when they’re playing if they’re not playing well.”

Organizational support

Organizational support was cited by parents as pre-planning their daughters golf such as arranging social play for her, packing the bags, booking of flights and hotels, planning training, the schedule and planning themselves around their daughters’ golf to ensure they were available for her. Parent 2 explained:

“It’s become part of my routine as well. Now it just takes time. And so, I try and build that into my own schedule of what things I need to do. And so, I will always try and make time for her.”

Planning the schedule was a critical aspect of parental support, with Parent 6 commenting “managing her schedule so that she’s still completing and fulfilling her academic responsibilities with school because she’s studying for A levels whilst fitting in the required amount of training each week.” Parents also cited how they felt it was important to include their daughter in the planning process. Parent 20 explained:

“We sit together from a schedule perspective, looking at what’s in the future. It is kind of, I try to involve her as much as possible. Otherwise, you just take control completely. And then they’ve got parties or, you know, even at the age of 14 and 15, they’ve got events, friends, parties coming up. So, we have to work around those kinds of things because if I booked everything in advance she’d be pretty upset if she missed out on one of her best friend’s 14th birthday parties.”

“We look at the composition of the field because we don’t want to, this is going to sound a bit snobby. We don’t want her playing in events that are probably a little bit below her competitive level. Because that starts to look bad on her record when it comes to important selections and stuff. So, we’ve always included her.”

Practical support

Parents referred to practical support as being the taxi driver for their daughter, videoing her to show to her or her coaches afterwards, ensuring she was properly hydrated, and eating well for tournaments. Parents discussed how critical it was to help their daughter keep a balance as a teenage girl. Parent 10 emphasized the importance of socializing:

“I know her well enough to know when she needs a bit of time out. I know she needs to go out with pals, and I know that’s important. And I said to her the other week, you need to take some time to go out with some of your pals and get away from Golf because what I don’t want to do is sicken her to the point where it becomes too much for her.”

“I'll make sure that she’s got enough liquids, I'll make sure that she has food. I'll spend a lot more time thinking about what she’s eating and what time she goes to bed. So, I just sort of try and get her ready for performance basically.”

“This summer we did eight or nine weeks back-to-back just on the road. We weren’t even necessarily coming back home. We were just washing clothes on the way. I was driving to Scotland, like eight-hour stints to compete, then eight hours back again like seven hours somewhere else” (Parent 7)

“She’ll hop in the car at three thirty to four in the morning. We’ll travel for three and a half hours. We’ll get to our cafe, she’ll have breakfast and she’ll see the coach at seven thirty am. Most golf events where we have to go to, we will leave at two or three in the morning.”

Reflective support

Reflective support involved parents supporting their daughter engaging in self-reflection. Whilst some aspects could be considered as emotional support by reflecting on the positives, there were other sub-themes of reflective support which could be considered as technical, practical, or even organizational support. For example, helping their daughter find focus for development and discovering learning opportunities. Therefore, it was important to highlight reflective support as a standalone component of support. All three sub-themes of reflective support involved parents helping their daughter through the reflection process by asking open questions and encouraging her to think and understand the process of reflection. Parent 2 described how they supported their daughter in helping her to critically think of each sessions purpose:

“Before she starts practicing, we will say, okay, right, 'What do you want to get out tonight then? What are we going to work on? Or what’s the goal for this evening? What are we going to try and improve? Which areas are we working on?”

Debriefing post-tournament enabled parents to assist their daughter reflect on their performance, explore learning opportunities, and identify what could be improved going forward. Parent 1 discussed the challenges in reflective supporting, stating:

“What went well, what didn’t go so well, and if it didn’t go so well, what are your thoughts? What can you do it to improve? So, it doesn’t happen next time, basically. So, try and promote some self-reflection without being, well, that shot was crap, and this shot was crap. You need to do a short game, you need to do that. You need to do this. And sometimes I can be a bit like that because you’re so emotionally involved in it. You know I'll say to her, why did you get so bloody angry on hole 14? Do you know what happened? And that’ll upset her. And so, I think it’s a really, really fine balance between being objective and being involved.”

“We might have a little chat when we’re in the car because in the car, as you know, you don’t have to look at each other. Sometimes it’s easier if we’re not having a face-to-face conversation, I can just try with a question. And if she’s in the mood to talk about it, she’ll answer. And if not, then I know that straight away.”

“I would ask her, where do you think you went wrong? To try and break it down and go, do you know what to do next time? You know what you work on and go away and do it. It depends on what she’s done. I mean, you can’t give a generic answer because each scenario has got to be different. But you try and just kind of break it down for and make her, see where she could have maybe done something better.”

“The first thing we always do after, after every tournament is talk about the shot of the day or come up with our top five. We just talk about positives even if it’s been a mixed round of when she’s come off a bit fed up, but she’s not played to her best. We’ll always talk about the best shots. We don’t, we very rarely talk about anything at that point on the journey home.”

Technical support

Parents discussed the range of technical support they provide their daughter. This included ball spotting, caddying for her when allowed, helping her to input statistics for her coach or the NGB, and assisting with course planning by taking notes and researching new courses.

Parents discussed the difference between providing technical advice themselves, and reiterating coaching points provided by their coach depending on their own level of technical knowledge. Parent 2 explained, “I would always go to the one-to-one sessions that she had. I'd remember everything. And then when she goes and practices, I repeat what they’ve said, and I’d try not to put my own ideas in.” Parent 9 highlighted that they can provide some technical advice through support from the coach:

“Coach 9 has taught me a lot about how to look at certain tendencies that Daughter 9 has regarding her golf swing. So be looking out for certain things going on and when this is happening, this is what’s going on. So, I've got very good at understanding her tendencies with her golf swing.”

“I just say one thing to her about something that her body was doing to try and just get her to stop thinking about everything being wrong and just to focus on one little thing that maybe was completely irrelevant, but it is almost like a diffuse or a distraction.”

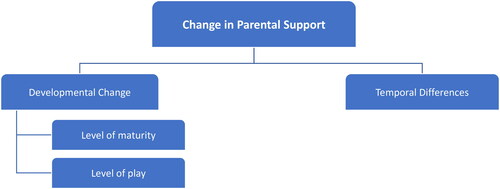

Changes in parental support

Parents discussed the developmental changes in their support based on two themes (maturity and level of competition) and how these influenced the support they were providing. Analysis also identified differences in parental support as a consequence of where their daughter was in their competitive or off-season training ().

Developmental change

Developmental changes were identified as a consequence of where their daughter was in their competition or off-season. Specifically, parents identified increases in their support of their daughter as a consequence of increases in competition play. Second, developmental changes and maturity levels impacted the type and amount of support provided by parents. Specifically, parents commented as their daughter matured, and began to take more responsibility for their golf, parents were able to reduce some types of support (i.e., organizational, practical, technical). However, parents collectively cited that financial, practical, and organizational support dramatically increased with their daughters’ level of play. Parent 1 highlighted:

“We got her some lessons and I think as she’s progressed and the level of support that we’ve put in has changed as well. We’ve put in better coaches we’ve bought better golf clubs. We’ve entered a wider range of competitions and national events rather than local events.”

“When she was younger, she was maybe 10, 11. There would be a lot more asking me what I thought. Now she absolutely does not want to know what I think. She just wants me to pass the club. She’ll bounce things off me and we’ll talk about wind or other factors. But she doesn’t want me to suggest anything because she knows her own game much better than I do now.”

“If they have a bad tournament, you know, there’s still some emotional support required to just say, you know, well look, you didn’t score as well as you would’ve liked, but you did this well. And you did that well. And you know, the next one you just build on those things that went well for you this time” (Parent 11).

“You might want to do all this yourself, but you can’t. You accept that you can’t and that you’re willing to accept this support, it’s always going to be a battle. So there’s an education process, once she gets to 17, 18, then she’s driving her own car hopefully and going to practice herself, then she’ll take more ownership. But I think at the moment I've got to find ways of supporting her through this transitional period in her development.”

Temporal differences

Changes in parental support were also related to temporal differences, specifically whether their daughter was in tournament or off-season. Parent 2 summarized:

“I'm equally as committed whether she’s playing in a national competition or whether she’s just training in a gym session in the house or practicing her putting. I think there’s no difference from me in the commitment that I give to her.”

“I do help her more in the off-season than I would during the season. I try and take a step away and let her do her thing during the season. We’re trying to learn in the offseason so that when she comes to the season, she can go and do her stuff. So, I would probably be actually more involved in the off-season.”

When discussing reflective support, Parent 4 emphasized the different approach that is needed depending on the time of year:

“You have to tailor what you say so that it’s not going to put them right off for the next round of golf. I think at training, I'm not saying you can be a bit more critical, critical is not the word I’m looking for, but a wee bit more honest at training but, I think it’s definitely different.”

Finally, emotional support appeared to intensify dramatically during the season as parents highlighted that limited emotional support was needed during the off-season. Parent 3 highlighted “emotional support is very different because, in training, she doesn’t need any emotional support unless it’s really cold. Then I have to keep saying, but you have to be tough that’s the only way to succeed.” However, when it came to tournaments, parents needed to increase the level of emotional support they were providing by just being there, always giving her a big hug at tournaments, and helping their daughter to manage her expectations and disappointments. Additionally, Parent 11 discussed:

“I would say the off-season is really relaxed from an emotional perspective. You’re kind of in a lower gear. Then in the tournament season, you’re in a pretty high gear… and from that perspective, I think [you need] be pretty supportive.”

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine the parents’ perspective of how they support their daughter in her golf, exploring the changes in their support depending on temporal or developmental differences. Results revealed that parents provided six types of support including emotional, financial, organizational, practical, reflective, and technical support. Findings complement previous research exploring parental support in youth sport from different perspectives. However, the present study strengthens the current literature by providing novel findings (e.g. reflective and technical support) which further advance the parenting literature in sport. Research previously conducted by Burgess et al. (Citation2016) highlighted that parents provide essential financial, informational, and emotional support to their child-athlete. Similarly, Garst et al. (Citation2020) argued the role of the parent was to provide logistical and financial support. Furthermore, Rees and Hardy (Citation2000) highlighted the dimensions of support as emotional, esteem, informational, and tangible support which align to the grounded theory of support developed by Burke et al. (Citation2023a).

The present study extends the grounded theory of parental support conducted by Burke et al. (Citation2023a) by providing a new insight from the parents perspective, and how the support changes depending on temporal or developmental changes. Burke et al. (Citation2023a) developed a grounded theory with key categories of support from the athlete perspective which included informational, instrumental, emotional, and autonomy support. Furthermore, additional types of support include technical and reflective support which provide a unique perspective of the parents perception of parental support within youth sport. Parents discussed providing technical support for their daughter which provides a unique perspective and extends beyond the informational support in previous literature (e.g., Burke et al., Citation2023a; Rees & Hardy, Citation2000). Due to the substantial discussions that occur around the technical aspects of the sport of golf, and how parents provide this type of support, this provides a novel insight into technical support. Parents differentiated between providing technical advice and reiterating coaching points depending on their own level of knowledge within golf. Research conducted by Furusa et al. (Citation2021) suggested that parents felt their knowledge and experience of the sport could be seen as both a barrier and a facilitator to their child-athlete depending on the level of knowledge they could provide. However, the findings of this study extend beyond the research of Furusa et al. (Citation2021) by discussing the parents perspective showing that in some cases parents did attempt to provide technical advice which they had either researched for themselves or transferred from other sporting knowledge. Whilst parents felt they were being supportive in this case, previous literature highlights that from the athlete’s perspective this could be conceived as unsupportive behavior. Specifically, Burke et al. (Citation2023b) reported that unsolicited interference was cited as unsupportive behavior from the athletes when their parents persisted to provide technical support that was unwanted.

Parents discussed the importance of providing practical support for their daughter by ensuring she had the correct nutrition and hydration to perform at her best. This complements research conducted by Furusa et al. (Citation2021) in field hockey, football, golf, gymnastics, swimming, and tennis. Findings highlighted children perceived their parents to be positively supporting them by providing the appropriate nutrition to perform when it came to tournaments and matches. The current study therefore strengthens the previous literature by providing the parents perspective of practical support in line with the perceptions of youth athletes. This highlights the overlap in perceptions of parental support from both the perspective of the child-athlete and the parent. Parents emphasized the critical organizational support they provide for their daughter by arranging social play to ensure their daughter had fun whilst playing at a highly competitive level, planning, booking, and organizing travel. The sub-category of planning involved parents pre-planning training, planning the schedule, and even planning themselves around their daughters’ golf to ensure they were available whenever she needed them. Interestingly, Furusa et al. (Citation2021) highlighted that parents felt their own work commitment and schedules could be viewed as both a barrier and a facilitator to the level of support they provide. However, it should be noted that a unique perspective within the current study highlighted parents awareness of providing opportunities as parents emphasized that they did not want to be the reason for their daughter missing any opportunities, so they ensured ample planning was in place whether it was themselves or other family or friends who could step in to assist on the off chance they were not able to. Hurtel and Lacassagne (Citation2011) suggested that when providing organizational and practical support for their children, parents described it as a ‘familial project’ as parents worked together to find solutions to providing the best support possible. Additionally, Garst et al. (Citation2020) highlighted that parents were known as the ‘credit card or the taxi’ for their youth athlete, clearly linking with the results of the current study as parents provide critical financial and practical support.

Findings from the current study complement the existing literature surrounding the importance of parents providing emotional support for their child-athlete (Burke et al., Citation2023a, Citation2023b; Rees & Hardy, Citation2000; Teques et al., Citation2018). Contradictory to the research of Wolfenden and Holt (Citation2005) which suggested parents emotional support tended to focus more on poor performances, the results from the current study expand the previous body of literature by incorporating managing disappointments while also celebrating the wins as emotional support. A novel finding within the present study highlighted the importance of athletes having fun regardless of their level of play. This provides a new perspective on the meaning of ‘fun’ within competitive youth sport. Elliott et al. (Citation2018) previously suggested that fun changes as an athlete progresses through the different stages of development to higher level competitive sport. However, the current study emphasized the need to still have fun as an aspect of parents providing emotional support through motivating their daughter with fun and alternative ways of play. When describing the ways in which parents supported their daughter emotionally during her golf, a highly cited form of emotional support was just being there for her and giving her a big hug similar to the research of Rees and Hardy (Citation2000). Comparably, Teques et al. (Citation2018) suggested parents emotional support was centered around providing praise and encouragement during side-line behaviors. The findings of the current study echo the importance of just being there for her, specifically in the setting of golf. Therefore, results showed displaying positive body language and providing positive encouragement where possible, were critical elements to emotionally supporting their daughter. Furthermore, the results reiterate Knight and Holt’s (Citation2014) research by providing a climate of emotional understanding by helping their daughter to manage disappointments, manage expectations, and just being there for her to ensure she felt emotionally supported and understood in all contexts whether they win or lose.

A novel finding of the current research highlighted the niche support type defined as reflective support. Parents articulated reflective support to be a pertinent category of support, with further sub-themes including reflecting on the positives, finding focus for development, and learning opportunities. Parents described this type of support as helping their daughter to reflect for themselves by asking open ended questions and allowing their daughter to reach conclusions for themselves with their help. Whilst current literature highlights some aspects of reflective support, these have previously been interlinked between other types of support (Woodcock et al., Citation2011; Furusa et al., Citation2021). However due to the repetitive identification of reflective support across interviews, the current study elevates reflective support to a critical standalone type of parental support. Elliott and Drummond (Citation2017) highlighted the importance of what happens after a game, suggesting parental involvement in debriefing their youth athlete may either enhance or undermine the youth athletes experience. For example, Burke et al. (Citation2023b) highlighted athletes’ preference for providing strategic support through post-competition feedback. Athletes in the specializing stage described how they would run through each hole with their parents and discuss what went wrong, however as the athlete progressed to the investment stage, they began to take more control of the post-competition feedback. Although there are similarities in the way in which parents provide this support, the strategic support tended to center around competition rather than training and competition. Furthermore, strategic support only aligns with the sub-theme of learning opportunities and therefore the reflective support provided by parents expands beyond strategic support.

Similarly, aspects of emotional support directly link to the sub-theme of focusing on the positives within reflective support. For example, Knight et al. (Citation2016) highlighted how parents encouraged positive perspective taking particularly after a poor performance. However, from the perspective of the athlete, if this was timed incorrectly, it could lead to further frustration and anger for the athlete. It is important for parents to understand the complexity and risks of providing this type of reflective support for their youth athlete and should be based on the athletes individual preferences (Burke et al., Citation2023a; Elliott & Drummond, Citation2017). Furthermore, Rees and Hardy (Citation2000) have suggested informational support includes help with performance concerns, loss of confidence, and interpersonal problems by putting things into perspective. Similarly, research conducted by Woodcock et al. (Citation2011) highlighted how parents perceived they offered support by helping their child-athlete to understand their performances. However, again they were unsure about the correct timing of providing this feedback. The current results go beyond the timing of providing this type of support by assisting their daughter in critically thinking about her own performance rather than jumping in and providing what could be viewed as criticism if delivered at an inappropriate time. Furthermore, McCann et al.’s (Citation2022) research displayed how parents provided feedback and evaluation to help their child-athlete overcome disappointment by providing praise. However, their support appeared to focus on providing direct feedback and praise rather than open-ended questions to help the athlete reflect for themselves. Therefore, whilst some aspects of reflective support relate to the current literature, the findings expand this by providing a broader spectrum of reflective support throughout training and competition by finding focus for development, focusing on the positives, and learning opportunities by actively engaging with their daughter to assist them in concluding rather than providing the answers for them.

Results from the current study related to the changes in support, resonate with Knight et al.’s (Citation2016) research which sought to gain the athlete’s perspective of support. Similarly, their results showed that athletes also highlighted the change in parental support roles depending on the context such as at home, at training or at competitions. Furthermore, Knight et al. (Citation2011) also examined the difference in the level of support provided before, during, and after competition. The current study emphasized that parents felt the level of commitment was unwavering depending on the time of year context, but that each type of support varied in the level that was provided. For example, parents described how they provided consistent support all year round, such as financial support was constant, but higher levels of financial support were necessary when it came to tournaments and traveling.

Previous research examining parental support across different development stages relying on retrospective experiences, has been questioned surrounding the issue of recall (Lauer et al., Citation2010). Therefore, more recently research has focused on examining participants currently in the development stages to minimize recall concerns (Burke et al., Citation2023a, Citation2023b). As a result, the current study emulated this approach which is representative of individual support experiences and changes in parental support. However, it should be noted that the results highlighted a change in parental support due to developmental changes which incorporated their daughters’ level of play, and their maturity level, and secondly temporal differences. Although parents emphasized how they provided all types of support no matter the development of their daughter, the level of each type of support changed as their daughter matured in her golf. For example, organizational, practical, and technical support tended to decrease as their daughter’s maturity level increased. This decrease in the level of support allowed for the transition from parental direction and support to adult ownership from the athlete. However, parents noted that they had some difficulty transitioning their support and learning to take the step back which aligns to previous research by Harwood and Knight (Citation2015) whereby parents adapting their involvement to support their child-athletes development was critical. These findings further align with previous research suggesting that parental involvement is greater in the early years of sport with parents heavily investing their time and finances in their child-athlete and their sport (Wylleman & Lavallee, Citation2004).

Hurtel and Lacassagne (Citation2011) stated parents in the early years of sport considered emotional support to be of higher importance than the logistical and financial support they provided. However, the present study highlights the constant need for emotional support throughout the youth athletes’ development, fluctuating depending on the context and timing throughout the year. Parents discussed how their emotional support evolved whereby in some types of emotional support it decreased, while others increased depending on the situation. For example, the cheerleading role had decreased slightly as their daughter did not constantly need the reassurance that she was doing well. However, they did feel they needed to increase the level of emotional support in conjunction with reflective support when it came to managing disappointments by focusing on the positives and finding learning opportunities to carry forward. These overall findings provide an advancement of theoretical knowledge resonating with the grounded theory of support (Burke et al., Citation2023a), by providing the parents perspective and the need for evolving support depending on influential factors and the context (i.e., developmental, and temporal changes). Furthermore, the changes in support reported within the present thesis strengthen the argument that athletes progress through development stages at different times (Côté & Vierimaa, Citation2014). As a result, the support provided by parents changed with their youth athletes level of maturity or level of competitive play, rather than the specific stages within the DMSP (Côté & Vierimaa, Citation2014).

Furthermore, a novel finding from the present study was that whilst a family network supported the female golfer, the majority of support came from one parent who was more involved in their golf, particularly during tournament season, and tended to be the father more often than not. Contrastingly, the findings from Lev et al. (Citation2020) suggested that fathers tended to provide more logistical support and mothers provided emotional support. However, the novelty of girls’ golf highlights that in many cases the fathers are more involved in supporting their daughter, which includes attending tournaments and traveling away and as a result they provide most of the emotional support. Therefore, parents suggested they could benefit from more information and understanding of how to deal with a teenage girl.

Applied implications

Findings from the current research revealed the different types of support parents provide for their female youth golfer, and the ways in which their support changes. These findings provide valuable information for sport psychologists, golfing national governing bodies, coaches, and parents in terms providing an insight into the level and detail of support that parents provide for their female youth golfer. There appears to be a disconnect between what parents and coaches or national governing bodies perceive parental support to be as previous education programs designed from the NGBs perspective highlights what parents should or shouldn’t do rather than the explicit needs identified from the parents perspective (Dorsch et al., Citation2019). Therefore, there should be a better understanding between parents, coaches, and the NGB in terms of the role that parents play in supporting their female youth golfer. Sport psychologists can build upon the current findings when assisting the development of youth athletes, by involving the parent in managing emotions for their child-athlete but also providing some help for how parents may manage their own emotions to avoid having a negative impact on their child-athlete. Finally, coaches can gain a critical insight from the findings from the parents’ perspective of support and how they can create open communication between parent, coach, and athlete when offering some support with scheduling and what to expect as their daughter progresses in her golfing career.

Limitations and future research directions

Alongside the unique findings presented, results from the current study resonate with much of the previous research in the field from different sports such as tennis, soccer, and more recently golf. As a result, the current results add to the growing body of literature with many similarities and some new novel findings. However, some limitations from the current study warrant further discussion. Previous research has shown the supportive and unsupportive behaviors of parents from the perspective of the athlete (Burke et al., Citation2023b). The current study failed to consider the perspective of the child-athlete as previous literature has highlighted the differing views between parents and their child-athlete (Kanters et al., Citation2008). As a result, some parents cited ways in which they positively support their daughter, however in some cases their child-athlete may portray this as unsupportive depending on the context (Burke et al., Citation2023b).

Conclusion

The aim of the present research was to explore parents’ perspective of the types of support they provide, and the changes in their support depending on several factors. The results further complement the grounded theory of parental support in youth golf developed by Burke et al. (Citation2023a) providing an insight into the parents’ perspective and how the different types of support align with the grounded theory. The current research presented some novel findings regarding reflective support that parents provide. The current findings also reinforced the need to provide support programs for parents based on their needs, rather than programs designed from a governing body or coaches perspective of parental support. Providing parents with assistance will allow for a better support network for their child-athlete and enhance their opportunities of excelling in their sport.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, vol. 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- Burgess, N. S., Knight, C. J., & Mellalieu, S. D. (2016). Parental stress and coping in elite youth gymnastics: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health, 8(3), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2015.1134633

- Burke, S., Sharp, L., Woods, D., & Paradis, K. F. (2023a). Advancing a grounded theory of parental support in competitive girls’ golf. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 66, 102400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102400

- Burke, S., Sharp, L., Woods, D., & Paradis, K. F. (2023b). Athletes’ perceptions of unsupportive parental behaviours in competitive female youth golf. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 35(6), 960–982. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2023.2166155

- Clarke, N. J., & Harwood, C. G. (2014). Parenting experiences in elite youth football: A phenomenological study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(5), 528–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.05.004

- Cohn, P. (1990). An exploratory study on sources of stress and athlete burnout in youth golf. The Sport Psychologist, 4(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.4.2.95

- Côté, J. (1999). The influence of the family in the development of talent in sport. The Sport Psychologist, 13(4), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.13.4.395

- Côté, J., & Vierimaa, M. (2014). The developmental model of sport participation: 15 years after its first conceptualization. Science & Sports, 29, S63–S69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2014.08.133

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. (2018). Research design (pp. 155–179). SAGE.

- Dangi, T. B., & Witt, P. A. (2018). Why children/youth drop out of sports. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 36(3), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.18666/JPRA-2018-V36-I3-8618

- Dorsch, T. E., Vierimaa, M., & Plucinik, J. M. (2019). A citation network analysis of research on parent − child interactions in youth sport. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 8(2), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000140

- Elliott, S. K., & Drummond, M. J. (2017). Parents in youth sport: What happens after the game? Sport, Education and Society, 22(3), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1036233

- Elliott, S., Drummond, M. J. N., & Knight, C. (2018). The experiences of being a talented youth athlete: Lessons for parents. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30(4), 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1382019

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

- Fry, J., Hall, P. (2018). Overview of Existing Research. Women’s, Girls’ and Family Participation in Golf: An (pp. 1–56). Preston. https://www.cgigolf.org/club-support/women-in-golf-charter/

- Furusa, M. G., Knight, C. J., & Hill, D. M. (2021). Parental involvement and children’s enjoyment in sport. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(6), 936–954. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1803393

- Garst, B. A., Gagnon, R. J., & Stone, G. A. (2020). “The credit card or the taxi": A qualitative investigation of parent involvement in indoor competition climbing. Leisure Sciences, 42(5–6), 589–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2019.1646172

- Gould, D., Lauer, L., Rolo, C., Jannes, C., & Pennisi, N. (2008). The role of parents in tennis success: Focus group interviews with youth coaches. The Sport Psychologist, 22(1), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.22.1.18

- Harwood, C. G., & Knight, C. J. (2015). Parenting in youth sport: A position paper on parenting expertise. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.03.001

- Hastie, P., & Hay, P. (2012). Qualitative approaches. In K. Armour, & D. Macdonald (Eds.), Research methods in physical education and youth sport. Routledge.

- Holt, N. L., & Knight, C. J. (2014). Parenting in youth sport: From research to practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203798553

- Hurtel, V., & Lacassagne, M. (2011). Parents’ perceptions of their involvement in their child’s sport activity: A propositional analysis of discourse. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 30(4), 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X11416206

- Kanters, M. A., Bocarro, J., & Casper, J. (2008). Supported or pressured? An examination of agreement among parents and children on parent’s role in youth sports. Journal of Sport Behavior, 31(1), 64–80.

- Knight, C. J., & Holt, N. L. (2014). Parenting in youth tennis: Understanding and enhancing children’s experiences. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(2), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.010

- Knight, C. (2019). Revealing findings in youth sport parenting research. Kinesiology Review, 8(3), 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2019-0023

- Knight, C. J., Little, G. C. D., Harwood, C. G., & Goodger, K. (2016). Parental involvement in elite junior slalom canoeing. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(2), 234–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2015.1111273

- Knight, C. J., Neely, K. C., & Holt, N. L. (2011). Parental behaviors in team sports: How do female athletes want parents to behave? Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2010.525589

- Lauer, L., Gould, D., Roman, N., & Pierce, M. (2010). Parental behaviors that affect junior tennis player development. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(6), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.06.008

- Leff, S. S., & Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Young athletes’ perceptions of parental support and pressure. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537149

- Lev, A., Bichman, A., Moyal, A., Brenner, S., Fass, N., & Been, E. (2020). No cutting corners: The effect of parental involvement on youth basketball players in Israel. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 607000. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.607000

- McCann, B., McCarthy, P. J., Cooper, K., Forbes-McKay, K., & Keegan, R. J. (2022). A retrospective investigation of the perceived influence of coaches, parents and peers on talented football players’ motivation during development. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(6), 1227–1250. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.1963013

- Morgan, D. L. (2014). Pragmatism as a paradigm for mixed methods research. Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods (pp. 25–44). SAGE.

- Rees, T., & Hardy, L. (2000). An investigation of the social support experiences of high-level sports performers. The Sport Psychologist, 14(4), 327–347. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.14.4.327

- Sheridan, D., Coffee, P., & Lavallee, D. (2014). A systematic review of social support in youth sport. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(1), 198–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2014.931999

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: From process to product. Routledge.

- Syngenta. (2014). The opportunity to grow golf: Female participation.

- Teques, P., Calmeiro, L., Martins, H., Duarte, D., & Holt, N. L. (2018). Mediating effects of parents’ coping strategies on the relationship between parents’ emotional intelligence and sideline verbal behaviors in youth soccer. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 40(3), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2017-0318

- Williams, N., Whipp, P. R., Jackson, B., & Dimmock, J. A. (2013). Relatedness support and the retention of young female golfers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 25(4), 412–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2012.749311

- Wolfenden, L. E., & Holt, N. L. (2005). Talent development in elite junior tennis: Perceptions of players, parents, and coaches. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 17(2), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200590932416

- Woodcock, C., Holland, M. J. G., Duda, J. L., & Cumming, J. (2011). Psychological qualities of elite adolescent rugby players: Parents, coaches, and sport administration staff perceptions and supporting roles. The Sport Psychologist, 25(4), 411–443. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.25.4.411

- Wylleman, P., & Lavallee, D. (2004). A developmental perspective on transitions faced by athletes. In M. R. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 507–527). Fitness Information Technology.