ABSTRACT

Much research has focused on consumer adoption of online grocery shopping (OGS), with less attention paid to consumers’ decision-making styles (CDMS) in OGS. Prior research in other retail domains suggests that CDMS is an effective way to identify relevant consumer segments, thereby enabling retailers to differentiate their service offering and marketing efforts to different target groups. This study aims to segment online grocery shoppers based on CDMS by conducting a survey and cluster analysis with Finnish online grocery shoppers (n = 426). The study identifies three segments; Quality-oriented, Price-oriented, and Novelty-oriented. The segments were further specified by comparing their demographics, shopping characteristics and OGS behavior. The results indicate that the Novelty-oriented are the most active and loyal group of online shoppers, who offer potential for a variety of online grocers. They are the youngest, busiest, and most likely to work a full-time job and have children. The other two clusters also have clear profiles which grocers are wise to tailor their offering to. Overall, the results show that using CDMS for segmentation is a reasonable way to better understand characteristics and behaviors of online grocery shoppers, thereby helping retailers to target them more effectively.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated online grocery shopping (OGS) worldwide and the growth prospects are still promising, although we may see a temporary dip or more modest growth rates as the pandemic subsides (Brüggemann & Olbrich, Citation2022; East, Citation2022). As OGS has been a way to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic (Fuentes et al., Citation2022; Tyrväinen & Karjaluoto, Citation2022), holding on to customers who turned to online shopping because of the pandemic may be hard. According to Brüggemann and Olbrich (Citation2022) online grocers may have also failed to convince all consumers about the advantages of OGS during the pandemic, which may slow down the growth. Other constraints seem to be related to consumers’ perceived risks such as unpleasant surprises with delivered products and the quality of perishable foods (Frank & Peschel, Citation2020; Gruntkowski & Martinez, Citation2022; Stenius & Eriksson, Citation2023) and that many consumers simply enjoy the in-store experience and conventional service interactions (East, Citation2022; Van Droogenbroeck & Van Hove, Citation2021). Over the long term the OGS market is, nevertheless, expected to grow substantially (East, Citation2022; McKinsey, Citation2023). The challenge for retailers is profitability as the operating margins are narrow while the required capital expenditure into logistics and systems development is substantial (McKinsey, Citation2022). Customer retention is therefore vitally important in a business that requires volume (Brüggemann & Olbrich, Citation2022; McKinsey, Citation2022). Subsequently, knowing the existing customer base and its preferences and characteristics is critical.

Customer segmentation is one effective way to achieve this as it enables retailers to differentiate their marketing efforts to different target groups (Boedeker, Citation1995; Rezaei, Citation2015; Sinkovics et al., Citation2010). Segments of grocery shoppers have been identified in prior research, and even within research into OGS some attempts have been made to detect different customer groups (e.g. Bauerová et al., Citation2023; Brand et al., Citation2020; Frank & Peschel, Citation2020; Harris et al., Citation2017; Hand et al., Citation2009). These studies, primarily based on theories of technology adoption and use, have identified diverse types of online grocery shoppers thereby showing that segmentation is relevant. The studies to date have, however, not explicitly considered consumers’ typical shopping orientations (such as decision-making styles), which is an important construct in consumer research (Büttner et al., Citation2014). Consumers’ decision-making styles (CDMS or CDM styles) have been successfully used in several prior studies in other retail domains, for instance, to understand young consumers’ apparel shopping behavior in general (e.g. Bakewell & Mitchell, Citation2003; Walsh et al., Citation2001) and online (e.g. Cowart & Goldsmith, Citation2007; Jain & Sharma, Citation2015; Thangavel et al., Citation2022), shopping for well-being (Maggioni et al., Citation2019), food-related products (Anić et al., Citation2014, Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2013), organic food products (Prakash et al., Citation2018) and cars and confectionary (Nayeem & Marie-IpSooching, Citation2022). Empirical evidence (e.g. Alavi et al., Citation2016) supports the notion that such decision-making styles are reflected in purchase behavior and satisfaction. Traditionally, CDMS have included eight different styles (Sproles & Kendall, Citation1986): Quality conscious, Brand conscious, Novelty conscious, Recreational/Hedonistic, Price conscious, Impulsive, Confused by Over-choice, and Habitual/Brand-loyal. Usually consumers have more than one style and their applicability depends on the product and context investigated (Nayeem & Marie-IpSooching, Citation2022). Grocery shoppers may also adopt a different shopping behavior when shopping online as opposed to in-store (Brüggemann & Olbrich, Citation2022). Therefore, a better understanding of online grocery shoppers’ decision-making styles is important.

This study contributes to research on OGS but also to theory on CDMS by using it to identify different clusters of online grocery shoppers based on their typical decision-making styles. As food shopping encompasses a variety of different preferences and motives (Anić et al., Citation2015), we expect to find several relevant segments. We then seek to further specify the segments by comparing them in socio-economic and grocery shopping characteristics, as well as their OGS behavior. The results have the potential to help online grocers to target their online customers more effectively.

The article is structured as follows. First, previous consumer segmentations in OGS and consumers’ decision-making styles are discussed. Next, the Finnish grocery market (where the study was conducted), data collection and the measures in the survey are described. Third, the cluster analysis and the profiling of the clusters is presented. Finally, the formed segments are discussed, conclusions drawn, and further research suggested.

Theory and literature review

Segmenting online grocery shoppers – prior research

Some prior attempts to segment online grocery shoppers have been made. Using consumer adoption of innovation as a theoretical lens, Frank and Peschel (Citation2020) identified three segments of online grocery shoppers in Denmark: Price-oriented, Time optimizers and Cautious shoppers. For the Price-oriented shoppers price in particular but also product range and fast, reliable deliveries were important. Time optimizers valued time saving and the freedom to shop whenever they want to, while Cautious shoppers appreciated personal service and being able to trust the retailer. Very small differences, if any, were found in the demographics. Based on their study, Frank and Peschel (Citation2020) argue that customers differ relevantly in terms of the perceived benefits (saving money, saving time, desire for personal service) and retailers should take account of this. In a similar fashion, Harris et al. (Citation2017) used advantages and disadvantages to cluster online and in-store grocery shoppers. Brand et al. (Citation2020) used thirty attitudinal items, aligned with the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and technology acceptance model (TAM), and a cluster analysis to identify five segments of grocery shoppers in a study in the UK. Two of them were frequent or relatively frequent online shoppers: the so-called Intensive urbanities and Online omnivores. Intensive urbanites reside in Greater London with children, and they shop a lot, both online and offline. They are typically busy finding it challenging to plan, younger, overrepresented by men, highly educated, and they earn much more than the standard shopper. Online omnivores are found across the country; they are somewhat older with a medium income, not overly busy and therefore able to plan their shopping. They embrace the instrumental benefits of online shopping and prefer it to in-store shopping. Also, in the UK, Hand et al. (Citation2009) argued for situational factors as a basis for segmenting online grocery shoppers. Their study could identify two “situational” clusters of OGS adopters, namely those with health related and those with family-related reasons. Discontinuing OGS, in turn, related more to poor online service or preference to shop in-store. The authors argue that when the underlying situational reason no longer applies, the person might stop shopping online. Using TAM as a theoretical lens, Bauerová et al. (Citation2023) identified five online shopper segments in the Czech Republic. Unlike Frank and Peschel (Citation2020), who found no demographic differences, all segments were dominated by a certain demographic, either men or women in a certain age bracket. Quality-Oriented Shoppers were primarily young men (25–34 years) who were comfortable shopping online and focused on quality. Movable Eco-Sympathizers, the most active online shopper, were typically women in the age bracket 35–44 years. They value the quality of food, access to organic food and other special product categories. Another segment, also dominated by women in the same age bracket, the Influential Utilitarians, are not very loyal, but they appreciate the convenience with OGS and ability to plan their shopping. Loyal Traditionalists are typically men in the age group 45–54 with higher income, who are loyal to their current retailer, whereas Satisfied Conditional Loyalists are typically women in the same age bracket, also loyal but able to switch if their needs are not met. To conclude, beyond demographics, differences were found in preference for quality, convenience, and loyalty. Seitz et al. (Citation2017) investigated select demographic groups among German online grocery shoppers and suggest that working mothers, young professionals, and silver surfers (retired) benefit more from OGS than other groups.

These prior studies suggest that differences in perceived benefits and lifestyle-related situational and other factors, such as belonging to a certain demographic, are reasonable ways to group grocery shoppers. The findings are, however, quite mixed, and it is reasonable to say that segmentation of online grocery shoppers is under-investigated. There are more aspects to OGS that might relevantly cluster shoppers, such as typical decision-making styles, which have been used in other retail areas, including grocery shopping.

Consumer decision-making styles

Decision-making styles have been conceptualized in very different ways in research. Some approaches focus on the cognitive and regulatory processes involved in decision-making and subsequent choice (Dewberry et al., Citation2013), whereas others emphasize the habitual trait-like nature by which an individual confronts a decision situation (Driver, Citation1979; Scott & Bruce, Citation1995), distinguishing for instance between typically rational or typically intuitive decision makers (Scott & Bruce, Citation1995). Karimi et al. (Citation2015), who investigated online shopping behavior, suggest that a decision-making style can be defined as an individual’s tendency to either maximize or satisfy (or satisfice) a decision. Maximizers seek out alternatives, take their time evaluating them, and look for the best possible options, whereas satisfiers strive for “good enough”, settle for fewer options and invest less time and effort (Chowdhury et al., Citation2009; Karimi et al., Citation2015, Citation2018). Somewhat similarly, Mittal (Citation2017) identified distinct decision-making styles based on differences in consumers’ characteristic and willingness to spend effort in information processing.

This study applies the approach by Sproles and Kendall (Citation1986, p. 268) who define consumer decision-making style (CDMS) as “a mental orientation characterizing a consumer’s approach to making consumer choices.” Similarly, to some other approaches (Karimi et al., Citation2015; Scott & Bruce, Citation1995), there is an element of trait-like preferences, but unlike the other approaches, CDMS also emphasizes shopping motives. Such motives are context-dependent and vary by shopping occasion (Maggioni et al., Citation2019). The eight styles, also referred to as consumer styles inventory (CSI), are presented and explained in .

Table 1. Consumers decision-making styles, CDMS (based on Sproles and Kendall (Citation1986)).

Bakewell and Mitchell (Citation2003) argue that the CDMS by Sproles and Kendall (Citation1986) offer a robust methodology to measure shopper orientations and behavior. Their eight decision styles have been successfully applied to many retail areas in prior studies [see for a summary] including a food-related shopping context (Anić et al., Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2013), and proven to relevantly explain shopping behavior. Therefore, the approach by Sproles and Kendall (Citation1986) with a ready consumer styles inventory was deemed appropriate for this study.

Table 2. Previous segmentation studies based on CDM styles.

Two prior studies have used and developed the inventory to suit food shopping, but not in the online context. Anić et al. (Citation2015) used the original CDM styles but modified them to suit consumers’ food-related shopping styles in Croatia. Using K-means clustering they identified three segments; Economic, Novelty-driven and Recreational consumers. Economic consumers search for the lowest prices and make less impulsive purchases, while Novelty-driven consumers are the most impulsive and confused by over-choice. Recreational consumers again shop for the fun of it and are quality conscious. Thomas et al. (Citation2013) also used the 30 items from the CDM styles by Sproles and Kendall (Citation1986) but they added other dimensions (13 items) used in food-related studies, one being local brand consciousness to study shoppers in the US. Using hierarchical clustering technique and Wards method they detected four shopper segments; Diverse consumers, Value-Loyal consumers, Emotional consumers and High-conscious consumers. The Diverse segment was a mixed bunch with no dominant CDM style whereas the Value-Loyal consumers, similar to Anić et al. (Citation2015) economic consumers, look for the best prices and value for money. Emotional consumers, similar to Anić et al. (Citation2015) novelty-driven segment, were impulsive and confused by over-choice, whereas High-conscious consumers score high on several styles, but especially on high-quality. The evidence is limited, but these studies show that CDMS can be used to segment food shoppers.

Segmenting online grocery shoppers using CDMS

As suggested by the preceding review, prior research on customer segmentation in OGS is quite limited, and it is difficult to draw conclusions based on the mixed findings. They do, however, evidence of diversity in online grocery shoppers, and support the notion that segmentation makes sense. Clustering solutions always depend on the sample and the choice of clustering variables (Mittal, Citation2017). The mixed findings reflect this, but they are also likely to reflect differences between markets/countries, and a reality that is under-investigated and therefore poorly understood. As no research, to our best knowledge, has used consumers’ CDMS to segment online grocery shoppers, an approach that has successfully been used in other retail areas, this study aims to do so. Socio-economic, grocery shopping characteristics and OGS behavior will also be investigated to further specify and define the segments. As suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2010), it is important to complement the profiles of different clusters with variables that are not included in the initial cluster analysis. More specifically this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

RQ1:

What segments of online grocery shoppers (if any) can be detected based on CDMS?

RQ2:

Are there differences between the segments in a) demographic and household characteristics, b) grocery shopping characteristics, and c) OGS behavior?

Method

The context: the Finnish grocery market

The overall grocery market in Finland was worth €21.6 billion in 2022 (PTY, Citation2023), dominated by the S chain (47% market share) and the K chain (35.2% market share), and followed by Lidl (9.8% market share) as the third largest chain (PTY, Citation2023). At 2.7% of the total grocery sales (€0.586 billion) in 2022 (NielsenIQ, Citation2023), the Finnish online grocery market is still quite small compared, for example, to the leading European market, the UK; where the share of OGS was 12% in 2021 in the food-at-home market (McKinsey, Citation2022). The main concern about the development and profitability of OGS in Finland is that it is a sparsely populated country, which makes cost-effective last-mile delivery challenging. However, 30% of the respondents in a large-scale and representative Finnish survey, conducted in the fall of 2022, reported that they had shopped for groceries online at some point during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 58% related positively to OGS (Karjaluoto, Citation2023). Similarly, another survey conducted in 2020 suggested that 26% of Finns had made grocery purchases online during the preceding year (Postnord, Citation2020), suggesting that the market is evolving. A more recent survey by Statistics Finland (Citation2022) suggests that 14% of adult Finns have bought groceries online in the past 3 months, slightly lower than the other Nordic countries (Sweden and Denmark 18%, Norway 17%, Iceland n.a.) but higher than the EU average of 10% (Eurostat, Citation2023).

The dominant in-store grocery retailers, the K and the S chains, are also the main providers of OGS, even if a broad range of other online alternatives have entered the market. Meal-kit services such as Ruokaboksi and Feelia, and online surplus retailers such as Fiksuruoka and Matsmart have increased in number and popularity, and pure online grocery retailers such as Kauppahalli24 are also on the market (Statista, Citation2023a). Furthermore, quick commerce companies such as Wolt and Foodora are growing and active in the larger cities.

The click-and-collect services are the most popular in some European OGS markets such as France and Belgium, while in the UK and the Netherlands home deliveries are the most popular (Van Droogenbroeck & Van Hove, Citation2020). In Finland the mix is quite even, as both the K chain and S chain provide both options.

To conclude, the Finnish online grocery market is still small but evolving. It is dominated by the two largest grocery chains, but there are new entrants as well. Thus, it is a market which is “catching up,” as opposed to leading, like most other European markets (McKinsey, Citation2022).

Data collection

The data was collected by surveying a consumer panel provided by a Finnish marketing research company Suomen OnlineTutkimus in April 2023. Of the total surveyed sample (n=828), those who reported that their household had purchased groceries online during the past three months, the criterion for being included in online grocery shoppers, were selected for this study (n=426). The same selection criteria of online shoppers are used by Statistics Finland (Citation2022) in their consumer surveys. The sample was collected from all major areas in Finland and with a relatively even distribution between male and female respondents (48.8% male/50.9% female/0.2% other), and an age distribution that corresponds to that of online shoppers in Finland. A nationwide survey by Statistics Finland (Citation2022) shows that there is an almost equal distribution among gender (male 13% and female 15% buy groceries online) and that the younger cohorts are more frequently buying online. The age distribution in the sample was as follows: 18–40 years 44.1%; 41–60 years 36.2%; 60+ years 19.7%. A one-sample chi-square test was run to compare how well the sample compares to Statistics Finland’s sample across gender. The results confirm similar gender profile (χ2 (df = 1) = 1.130, p = .288). Due to missing values for some cohorts and slightly different grouping in the public Statistics Finland sample we could not test for age. Nevertheless, the sample can be considered representative of the relevant population in the country. summarizes the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 3. CDMS items.

Table 4. Cluster comparison of the CDMS variables (n=426 online shoppers).

Table 5. Demographic and household characteristics for the clusters (% distribution). Bolded numbers are the contrasts.

Measures

The survey was divided into different sections, and not all questions were used for this study. The CDMS items presented in formed one section in the questionnaire. They are based on Sproles and Kendall (Citation1986) eight original styles and the adapted version by Anić et al. (Citation2014) for food-related CDMS. The additional style, local food consciousness, is based on Thomas et al. (Citation2013) local brand consciousness, which was included in their food-related CDMS study. Local food consumption is one of the fastest growing consumer food trends, but still sparsely investigated (Kim & Huang, Citation2021), and was thus included as an additional style. Importantly, in this survey the respondents were encouraged to answer on behalf of their whole household when applicable. All questions were therefore modified and instead of “I,” “we” or “in our household” was used. For single-households we emphasized that the use of “we” was merely a reminder for all respondents to answer on behalf of their household. The items were translated into Finnish with care and back-translated into English to check their accuracy.

Two variables of grocery shopping characteristics were measured “Time-effort constraints in grocery shopping” and “Responsibility for grocery shopping.” These are presented in . Time-effort constraints have commonly been used to explain differences in grocery shopping behavior (e.g. Buckley et al., Citation2007; Davies & Madran, Citation1997; Thomas et al., Citation2013), and were thus included. Time-effort constraints in grocery shopping were measured using four items: We do not like spending much time shopping for food (Buckley et al., Citation2007); We try to do our food shopping with as little hassle as possible (Boedeker, Citation1995); We are always looking to save time, and We are always in a rush (Davies & Madran, Citation1997). Responsibility for grocery shopping was included to understand if grocery shopping is a shared family matter or not, and if this can explain differences between the segments.

Table 6. Grocery shopping characteristics for the clusters. Bolded numbers are the contrasts.

Three variables measuring OGS behavior were used “OGS of total grocery purchases”, “Frequency of OGS per month” and “Loyalty to OGS”. These are presented in . By measuring these types of variables, we can better understand the behavioral outcomes of different types of consumer segments (Mittal, Citation2017; Shen et al., Citation2022). OGS % of total grocery purchases was measured from 1–100% with four groups (0–24%, 25–49%, 50% − 74%, 75% − 100%) but two groups “<25%” and “25–100%” were formed as most respondents buy less than half of their groceries online, and small cells restricts a reliable chi-square test. The frequency of OGS per month was asked with a numerical open question. Loyalty to OGS again was measured with four items; We try to use online grocery store, whenever there is a need to get groceries; When we need to buy groceries, buying them online is the first option; To us the best way to buy groceries is to buy them online; I believe that online is our favorite way of buying groceries (based on Gremler (Citation1995), and Zeithaml et al. (Citation1996) in Srinivasan et al. (Citation2002) but modified to apply to OGS in general).

Table 7. Online grocery shopping (OGS) behavior. Bolded numbers are the contrasts.

Last in the survey, demographic and household characteristics were asked. These variables are presented in . The annual household income was recoded into three groups: “€0–30.000” “€30.001–60.000” and “€60.000+,” representing low, medium, and high income. For households with children a dichotomous variable was used: “no children” and “children under 18 years at home.” The gender category “Other” was left out in further analysis due to very few observations. For the same reason, the occupation the category “Parental leave” was omitted from the final analysis. Remote work was measured on the scale 1–7 (1= never and 7=all the time). This variable was included as remote working has become more common and it may affect grocery shopping practices in a household.

Preliminary analyses

Cronbach’s α for the CDMS variables are found in . For each of the three styles: Quality consciousness, Recreational/Hedonistic and Habitual/Brand loyal one item was omitted to increase the internal consistency of the composite score (>.70). The omitted items are shown as strikethrough in . The α for Brand consciousness at 0.67 could not be improved by deleting items. However, 0.67 was deemed adequate based on α-levels used in previous food-related CDMS studies (Anić et al., Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2013). All items were measured on a Likert-type scale from 1 (=completely disagree) to 7 (=completely agree). All CDMS variables were sufficiently normally distributed, except for Novelty consciousness. Therefore, non-parametric tests were conducted additionally for this variable. The composite scores of the nine CDMS variables were used in the cluster analysis. See for descriptive statistics.

The items for Time-effort constraints and Loyalty to OGS were also measured on a Likert-type scale from 1 (=completely disagree) to 7 (=completely agree). Cronbach’s α at .75 for Time-effort constraints and .86 for Loyalty to OGS suggested good internal consistency. These two variables were normally distributed, and thus ANOVA were conducted for the composite scores.

Results

The clusters identified

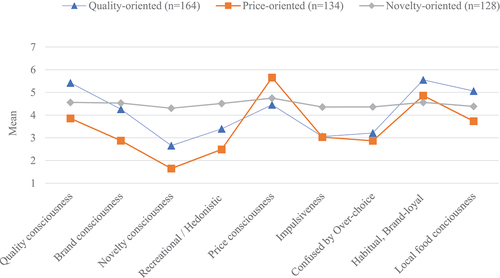

Both hierarchical and k-means (nonhierarchical) clustering methods have been used in previous studies to identify clusters based on CDMS in a food-related context (Anić et al., Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2013). Both are accepted and efficient clustering methods for data based on Likert-type scales (Hair et al., Citation2010). To respond to RQ1 (what segments based on CDMS can be detected?) a hierarchical cluster analysis with Ward’s method was run in IBM SPSS™ 29. As there was no basis for a specific number of clusters, required by k-means clustering, we chose to run the hierarchical procedure with cluster solutions from 2 to 5. This was deemed reasonable as most cluster solutions based on CDMS have generated between 2 and 5 clusters (see .). A three-cluster solution based on the hierarchical cluster analysis was considered best, as it showed good overall fit, quite even cluster sizes, and the best interpretable differences between the clusters, in accordance with Hair et al. (Citation2010), who suggests that the different solutions and their overall fit should be evaluated based on cluster sizes, the dendrogram, significance of clustering variable differences, the interpretability of the clusters and the stability of the cluster solution. A k-means analysis was also run with three clusters to verify and confirm the solution. The two solutions were similar, but the hierarchical solution made more sense when interpreting the cluster differences. See for a graphical presentation of the mean values for the detected clusters.

Figure 1. Mean values for CDMS variables for the three clusters. Scale from 1 (=completely disagree) to 7 (=completely agree).

The ANOVA (see ) suggests significant differences (p<.001) between the clusters for all CDMS variables. Kruskall-Wallis test performed for Novelty consciousness (as it deviated substantially from normal distribution) was also statistically significant (χ2 = 219.3, p<.001). Post-hoc tests further establish that significant differences exist between all three clusters for most of the variables. A further discriminant analysis based on group sizes established that 86.4% of the observations retained their cluster membership, indicating fairly good stability of the cluster solution.

The clusters were defined and named based on the plotted mean scores in and statistics in :

Cluster 1 “Quality-oriented shoppers” (38.5%) are characterized by the highest mean scores for quality consciousness, brand-loyalty, and local food consciousness.

Cluster 2 “Price-oriented shoppers” (31.5%) are characterized by the highest mean score for price consciousness and a very low mean score for novelty consciousness. It should be noted that all three clusters are quite price conscious.

Cluster 3 “Novelty-oriented shoppers” (30.0%) have moderately high mean scores for all styles while no specific style dominates. They have, however, the highest mean scores for novelty consciousness, recreational, impulsiveness, and confused by over-choice, and the gap to the other groups is especially large for novelty consciousness.

Cluster profiles

Next, to respond to RQ2, the clusters were profiled according to demographics and household characteristics, grocery shopping characteristics, and OGS behavior. For demographics and household variables Crosstabulation and Pearson χ2 scores and a Kruskall-Wallis test were used (see .). The clusters differ from each other significantly in all variables, except for education and remote work, albeit the effect sizes are quite small (Cohen, Citation1988), Cramer’s V values are between .14 and .20. The share of male respondents (60.2% vs 48.8% expected value) was highest among the Novelty-oriented, while that of female respondents (60.4% vs 50.9%) was highest among the Price-oriented. The share of younger respondents (18–40 years) was highest among the Novelty-oriented (57.0% vs 48.8%) whereas the share of older respondents (40+ years) was highest among the Quality-oriented (43.3% vs 36.2%; 24.4% vs 19.7%). The share of those with a full-time job was highest among Novelty-oriented (62.1% vs 50.0%), while the share of unemployed and retired was highest among Price-oriented (18.3% vs 11.6%; 27.5% vs 22.0%). The share of respondents in medium-income (€30.000–60.000) and higher-income categories (€60.000+) was highest among the Quality-oriented (37.1% vs 35.0%; 35.6% vs 26.5%), whereas the Price-oriented were more often than the others in the lowest income category (52.1% vs 38.5%). They typically had no children as opposed to the Novelty-oriented, of whom 37.5% (29.1% expected value) had children. The cluster with the highest share of respondents is bolded in for each row.

There were significant differences between the clusters in grocery shopping characteristics, in both responsibility for shopping, which was a family matter for the Novelty-oriented more often than for the others, and time-effort constraints, which was a more common concern among that Novelty-oriented than among the others (See .). Time-effort constraints in grocery shopping was analyzed using ANOVA with a post-hoc test. The effect sizes are quite small (Cohen, Citation1988), with Cramer’s V at .17, and η2 at .027.

There were also significant differences between the clusters in OGS behavior in all three variables (See .). The Novelty-oriented were more frequent and more loyal online shoppers than the other clusters, and the share of online of their total grocery purchases was highest. OGS frequency was analyzed using median values and Kruskall-Wallis test with a post-hoc test as the frequency score was non-normally distributed. Loyalty to OGS was analyzed using ANOVA with a pos-hoc test. The effect sizes in the crosstabulation test (Cramer’s V = .16) and Kruskall-Wallis test (η2 = .037) and ANOVA (η2 = .143), indicate small to large effects (Cohen, Citation1988). The large effect size was in Loyalty to OGS.

Based on the analyses the following characterizations were made:

Cluster 1 “Quality-oriented shoppers” are slightly overrepresented in the older age groups (40+ years) and have the highest annual household income. Regarding grocery shopping characteristics and OGS behavior, they do not stand out for any of the variables.

Cluster 2 “Price-oriented shoppers” are slightly overrepresented by women, unemployed and retired, and persons living in a single household with a relatively low annual household income. They seem to be more sporadic and least loyal online shoppers as they have the lowest OGS frequency online and they are slightly overrepresented in the category OGS less than 25% of total groceries.

Cluster 3 “Novelty-oriented shoppers” are the most loyal online shoppers. They are slightly overrepresented by male respondents, younger consumers (18-40 years) and those working full-time. They are also more likely to have children and share the shopping responsibility among household members. Furthermore, they are the most time-effort constrained (albeit not significantly more than the Price-oriented), have the highest OGS frequency, and the highest share of online grocery purchases.

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of this study was to identify segments of online grocery shoppers based on CDM styles and profile them according to demographic and household characteristics, grocery shopping characteristics and online grocery shopping behavior. Three segments of quite equal sizes were identified: “Quality-oriented,” “Price-oriented” and “Novelty-oriented” online shoppers.

“Quality-oriented shoppers” are similar to segments identified in previous studies, such as Bauerová et al. (Citation2023) who also identified a segment they referred to as Quality-oriented, with high-quality expectations. Previous segmentation studies based on the CDM styles (e.g. Akturan et al., Citation2011; Bakewell & Mitchell, Citation2003), have also detected a segment Quality-seekers, who usually shop systematically and carefully for food products (Thomas et al., Citation2013). In this study the Quality-oriented consumers not only seek high quality, but they are also loyal to select food product brands and appreciate locally produced food more than the other segments. They are slightly older consumers with the highest annual household income, indicating significant purchasing power. This segment of consumers could be interested in customized product offering in OGS, an offering that takes account of their orientation to product quality and brands (Brand et al., Citation2020). Presently they are not very active online or loyal to OGS, but it would make sense for the online grocers to target this segment as it can afford to pay premium for services that it values. Marketing communication that highlights the quality aspect, relevant product brands in combination with local food promotions could generate more interest in OGS among these customers.

“Price-oriented shoppers” have been identified in previous studies both within OGS and CDMS studies of in-store grocery shopping. For example, Frank and Peschel (Citation2020) identified Price-oriented online grocery shoppers in Denmark while Anić et al. (Citation2015) detected a similar segment and labeled it Economic-seeking grocery shoppers in Croatia. In the present study the majority of these shoppers are women and persons living in a single household, with a relatively low annual household income. They only shop online approximately once a month (median) and 70% of them buy less than 25% of their total groceries online, least of the three groups. They are the least loyal to OGS suggesting that they use online channels sporadically to search for bargains. Based on this, it seems reasonable to assume that these consumers are especially attracted to online grocers that provide attractive deals. For example, online surplus retailers in Finland (e.g. Fiksuruoka, Matsmart) that provide discounted prices on surplus food-related products are those who should target this segment. They have an established market position on the Finnish online grocery market (Statista, Citation2023a). Also, for other discounters (such as Lidl, should they go online in Finland, and Tokmanni) this segment ought to be interesting. Communicating bargains from standard food-related product categories (they have little interest in novel or trendy products) and notifying of low delivery prices could be a reasonable strategy for online grocers to attract this segment. It is, however, noteworthy that all three segments are quite price conscious.

“Novelty-oriented shoppers” in this study are similar to Thomas et al. (Citation2013) segment Diverse consumers, who do not have a specific dominant decision-making style. They are, however, more novelty conscious, recreation-oriented, impulsive, and confused by over-choice than the other two segments, suggesting a curiosity to try out new things. This segment is similar to the Novelty-driven segment by Anić et al. (Citation2015), which was characterized as those with the highest interest in trendy food products, the most impulsive and most confused by over-choice. There are also more of the younger (18–40 years) shoppers in this segment, and a larger share of those who work full-time and have children. Grocery shopping is also more likely to be a shared family matter for this segment than for the others. This suggests that a large share of busy, younger families in their most active years are in this group. The results further indicate that they appreciate quality and that they can afford (on par with the sample average for household income) a more impulsive shopping style. Trying out trendy products suggests that they seek out enjoyment in food-related chores. The segment Intensive urbanites by Brand et al. (Citation2020) has a similar profile to Novelty-oriented shoppers in the sense that they, too, are younger consumers, time-pressured, have children and are looking for convenient ways to plan their grocery shopping. Overall, this segment scores reasonably high on all CDM styles compared to the other two groups.

Furthermore, they have the highest online grocery shopping frequency, the highest share of grocery purchases online, and they are the most loyal online shoppers. To target these consumers, the full profile, including the demographics, should be considered. Some likely reasons for this group to buy groceries online is because it saves them time and effort, there is often a family to cater for, and they can afford it. Avoiding the discomfort of in-store shopping is often considered important by experienced online grocery shoppers (Stenius & Eriksson, Citation2023). Therefore, any services that help facilitate the weekly meal planning and order placement is likely to be appreciated and potentially induce greater interest in OGS with this segment. At the same time this somewhat impulsive group is also the most likely to appreciate instant deliveries from, for example, quick commerce companies with more limited product assortment (such as Wolt market and Foodora market in Finland) to save time and effort, and to accommodate for more ad hoc elements in meal planning. Notably, this segment more than the others appreciates trendy and novel foods and therefore these should be actively offered to this segment, such as new foods. Convenient additional services such as cooking instructions/videos could be valued by this segment. Due to the diversity in CDM styles and the profile presented, this segment is the natural lowest hanging fruit for online grocers, the easiest target group, but it is also attractive to a variety of other online service providers. Furthermore, this group has the highest loyalty to OGS, and is therefore a very important group for online grocers to keep happy.

Research and managerial implications

To both researchers and managers within OGS, the proposed cluster solution offers an additional way of looking at online grocery shoppers. In many countries the COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed the landscape of OGS, and the clusters based on CDM styles provide another way to profile online grocery shoppers compared to previous segmentation studies in OGS. A key contribution of this study is that it shows that CDM styles can be used to segment online grocery shoppers, as the clusters identified showed fairly good overall fit, interpretability, and stability. Therefore, this study has extended CDMS research to include the context of OGS. The segments were also profiled based on demographics, grocery shopping characteristics, and OGS behavior, which further defined them and relevantly explained their differences.

For online grocers, at least on the Finnish market, the clusters offer a means to design and sharpen marketing messages and service concepts to suit the different profiles. The online service is already a part of these consumers’ grocery shopping activities, and sustaining and enhancing their commitment and loyalty to OGS is critically important. Marketing communication could be designed to better suit the specific target segment and combine for this segment attractive offers or relevant item/meal suggestions, as briefly discussed for each segment earlier. For example, designing online communication (social media campaigns, paid advertising, e-mail-marketing, etc.) and targeting the specific segment, e.g. the Novelty-oriented by using these real Finnish campaign slogans “Ruokaboksi [Finnish meal-kit service] is an everyday hero” and “Rescue from busy everyday life” could be effective, especially in combination with meal suggestions/offers on some relevant novelties. The Quality-oriented shoppers could again be attracted by targeted online campaigns that combine slogans such as “Local and better” with pre-selected item suggestions, and/or meal suggestions that are likely to appeal to them.

The results could also be interpreted, tentatively, using another theoretical lens presented earlier. Karimi et al. (Citation2015) suggested that online decision-making styles essentially fall into two categories: maximizing and satisfying. It is not unreasonable to suggest that the Quality-oriented shoppers more likely use the principle of maximizing in their decision making, taking time, and perusing various options to maximize the quality of their product choices. The Novelty-oriented segment seems to operate with the principle of satisficing, appreciating quality and reasonable prices, but also shopping more impulsively and trying out novel products. Their lifestyle may dictate some of this: many work full-time, have children, and because of the many obligations are pressed with time but still seek to have an exciting life. The Price-oriented seem to operate more opportunely, but it seems that they first and foremost seek to maximize value for money, either out of preference or necessity. Such interpretations should at this stage be made cautiously but future research could benefit from attempts to complement the much-used approach by Sproles and Kendall (Citation1986), which emphasizes steady or habitual consumer preferences related to product characteristics or shopping, with those that emphasize other aspects of individual decision-making.

Limitations and future research

Survey research has some inherent limitations, one being self-reports of attitudes and behavior, which may be subject to biases and inaccuracy, risk of recall errors etc (Bryman, Citation2012; Krosnick, Citation1999, Citation2018). and another being measurement at a single time point (Rindfleisch et al., Citation2008; Spector, Citation2019). Question wording and order may affect how the participants respond, calling for caution when results are interpreted (Bryman, Citation2012; Krosnick, Citation1999, Citation2018). The content of some of the items in the nine CDM styles could in fact be reassessed. The ones used in this study have been used and found suitable in previous research on CDMS within a food-related context (Anić et al., Citation2014, Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2013). In this study, some of the styles had low Cronbach’s α, which were rectified by excluding items. Furthermore, the concept of quality could better distinguish between extrinsic and intrinsic quality attributes. A critical review of the items to develop the CDMS instrument to better suit a food-related shopping context would be justified.

Some of the effect sizes were quite low in the profiling phase of the clustering. However, the full picture of the profiling (e.g. contrasts within variable categories) revealed a much clearer pattern of logical differences between the groups, which lent further support for the interpretations. In future studies shopping behavior could be explored with other variables. The focus here was on OGS share of total grocery shopping, OGS frequency and loyalty to OGS. Intentions to shop for certain products online, customer satisfaction online, preferences for online service offerings, and the degree of routinization of OGS could, for example, be used. Then linear regression analysis with CDMS as independent variables could be more appropriate.

All three segments are interesting to target from an online grocer perspective. However, as the analysis suggests that many different decision-making styles are present among the Novelty-oriented, there may be segments within this segment that future research is wise to explore and understand better. Segmentation based on lifestyles could perhaps capture further nuances in this group better. Furthermore, non-adopters of OGS could be included in future segmentation studies to better understand similarities and differences in customer orientations among adopters and non-adopters. Targeting CDMS of non-adopters could be a way for online grocers to recruit new customers.

Generalizing beyond the specific market (Finland) should be done with caution, but perhaps less so with the other Nordic countries. In addition to their historical and cultural ties, they share many characteristics relevant for grocery retail, such as market concentration to a few large retailers, population density (or scarcity) and its concentration around capital areas, and typically larger stores, combined with similar age structure, high average income level, high standard of living (Einarsson, Citation2008), high technological savviness (Statista, Citation2023b), and quite high consumer adoption of OGS relative to EU average (Eurostat, Citation2023; Ytreberg et al., Citation2023). When the demographic and market characteristics are different, they may well be reflected in consumer shopping preferences, along with national culture (Hallikainen & Laukkanen, Citation2018) and values (Hansen, Citation2008), as evidenced in empirical research. We therefore encourage researchers to replicate a cluster analysis with CDMS items in other OGS markets.

Another aspect to consider in studies into OGS is the way we ask about shopping. Typically, the items are worded in singular (e.g. “In general, I usually try to buy food products with the best overall quality”) whereas grocery shopping is oftentimes a family matter. There may be cultural differences, for example, women may still have a dominant role in purchasing groceries (also online) in many countries (Van Droogenbroeck & Van Hove, Citation2020; Van Hove, Citation2022a). However, in our study 57% of the non-single households considered grocery shopping to be a shared responsibility. The equal distribution of women and men in our sample further suggests that in this market both genders shop for groceries online. It may be more of a shared family matter when groceries are bought online from home and the order may be modified over several days. In this study we opted to ask the respondents explicitly to answer on behalf of their household and modified the measures to accommodate this. We suggest that other researchers consider this aspect of grocery shopping. The matter of household activity and responsibility in OGS has also been recently discussed by Van Hove (Citation2022b).

We also encourage future research to use concise labeling of segments as was done in this study to make it easier to compare studies and accumulate research findings.

Final conclusions

The study identified three segments of online grocery shoppers; Quality-oriented, Price-oriented and Novelty-oriented. In line with Brand et al. (Citation2020) who stated that “there is no such thing as an average grocery shopper” we suggest, based on our study, that “there is no average online grocery shopper.” Overall, the results show that using CDMS for segmentation is a reasonable way to better understand characteristics and behaviors of online grocery shoppers, thereby helping online grocers to target them more effectively. Nevertheless, this study also made several suggestions for further research, including development of the CDMS instrument and considering other related theoretical frameworks as interesting avenues for further OGS research.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines drawn up by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity for non-medical research involving human participants. As the data collection consisted of a traditional survey, involving no manipulation or deception, with voluntary responses from adult participants, no formal ethical review and approval were required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be provided upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akturan, U., Tezcan, N., & Vignolles, A. (2011). Segmenting young adults through their consumption styles: A cross‐cultural study. Young Consumers, 12(4), 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473611111185896

- Alavi, S. A., Rezaei, S., Valaei, N., & Wan Ismail, W. K. (2016). Examining shopping mall consumer decision-making styles, satisfaction and purchase intention. The International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research, 26(3), 272–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2015.1096808

- Anić, I.-D., Piri Rajh, S., & Rajh, E. (2014). Antecedents of food-related consumer decision-making styles. British Food Journal, 116(3), 431–450. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-10-2011-0250

- Anić, I.-D., Rajh, E., & Rajh, S. P. (2015). Exploring consumers’ food-related decision-making style groups and their shopping behaviour. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 28(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2015.1022390

- Anič, L.-D., Suleska, A. C., & Rajh, E. (2010). Decision making styles of young-adult consumers in the Republic of Macedonia. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 23(4), 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2010.11517436

- Bakewell, C., & Mitchell, V. (2003). Generation Y female consumer decision‐making styles. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 31(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550310461994

- Bauerová, R., Starzyczná, H., & Zapletalová, Š. (2023). Who are online grocery shoppers? E&M Economics and Management, 26(1), 186–205. https://doi.org/10.15240/tul/001/2023-1-011

- Boedeker, M. (1995). New‐type and traditional shoppers: A comparison of two major consumer groups. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 23(3), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590559510083966

- Brand, C., Schwanen, T., & Anable, J. (2020). ‘Online omnivores’ or ‘willing but struggling’? Identifying online grocery shopping behavior segments using attitude theory. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102195

- Brüggemann, P., & Olbrich, R. (2022). The impact of COVID‑19 pandemic restrictions on offline and online grocery shopping: New normal or old habits? Electronic Commerce Research, 23(4), 2051–2072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09658-1

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford university press.

- Buckley, M., Cowan, C., & McCarthy, M. (2007). The convenience food market in Great Britain: Convenience food lifestyle (CFL) segments. Appetite, 49(3), 600–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.03.226

- Büttner, O. B., Florack, A., & Göritz, A. S. (2014). Shopping orientation as a stable consumer disposition and its influence on consumers’ evaluations of retailer communication. European Journal of Marketing, 48(5/6), 1026–1045. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-04-2012-0210

- Chowdhury, T. G., Ratneshwar, S., & Mohanty, P. (2009). The time-harried shopper: Exploring the differences between maximizers and satisficers. Marketing Letters, 20(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-008-9063-0

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cowart, K. O., & Goldsmith, R. E. (2007). The influence of consumer decision-making styles on online apparel consumption by college students. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(6), 639–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00615.x

- Davies, G., & Madran, C. (1997). Time, food shopping and food preparation: Some attitudinal linkages. British Food Journal, 99(3), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070709710168914

- Dewberry, C., Juanchich, M., & Narendran, S. (2013). The latent structure of decision styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 566–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.002

- Driver, M. J. (1979). Individual decision making and creativity. In S. Kerr (Ed.), Organizational behavior (pp. 59–94). Grid Publishing.

- East, R. (2022). Online grocery sales after the pandemic. International Journal of Market Research, 64(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/14707853211055047

- Einarsson, A. (2008). The retail sector in the Nordic countries: A description of the differences, similarities, and uniqueness in the global market. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 15(6), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2007.11.002

- Eurostat. (2023). Internet purchases - goods or services (2020 onwards). Retrieved January 14, 2024, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ISOC_EC_IBGS__custom_9352753/default/table?lang=en

- Frank, D.-A., & Peschel, A. O. (2020). Sweetening the deal: The ingredients that drive consumer adoption of online grocery shopping. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 26(8), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2020.1829523

- Fuentes, C., Samsioe, E., & Östrup Backe, J. (2022). Online food shopping reinvented: Developing digitally enabled coping strategies in times of crisis. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 32(2), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2022.2047758

- Gremler, D. D. (1995). The Effect of Satisfaction, Switching Costs, and Interpersonal Bonds on Service Loyalty [ unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Arizona State University.

- Gruntkowski, L. M., & Martinez, L. F. (2022). Online grocery shopping in Germany: Assessing the impact of COVID-19. Journal of Theoretical & Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 17(3), 984–1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17030050

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Hallikainen, H., & Laukkanen, T. (2018). National culture and consumer trust in e-commerce. International Journal of Information Management, 38(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.07.002

- Hand, C., Riley, F. D., Harris, P., Singh, J., & Rettie, R. (2009). Online grocery shopping: The influence of situational factors. European Journal of Marketing, 43(9/10), 1205–1219. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560910976447

- Hansen, T. (2008). Consumer values, the theory of planned behaviour andonline grocery shopping. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(2), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00655.x

- Harris, P., Dall’olmo Riley, F., Riley, D., & Hand, C. (2017). Online and store patronage: A typology of grocery shoppers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 45(4), 419–445. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-06-2016-0103

- Jain, R., & Sharma, A. (2015). Attributes and decision-making styles of young adults in selecting footwear. Studies on Home and Community Science, 9(2–3), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/09737189.2015.11885434

- Karimi, S., Holland, C. P., & Papamichail, K. N. (2018). The impact of consumer archetypes on online purchase decision-making processes and outcomes: A behavioural process perspective. Journal of Business Research, 91, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.05.038

- Karimi, S., Papamichail, K. N., & Holland, C. P. (2015). The effect of prior knowledge and decision-making style on the online purchase decision-making process: A typology of consumer shopping behaviour. Decision Support Systems, 77, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2015.06.004

- Karjaluoto, H. (2023, February 2). Kuluttajat muutoksessa. Research report. Vähittäiskaupan tutkimussäätiö ja Kaupan Liitto.

- Kim, S.-H., & Huang, R. (2021). Understanding local food consumption from an ideological perspective: Locavorism, authenticity, pride, and willingness to visit. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102330

- Krosnick, J. A. (1999). Survey research. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 537–567. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.537

- Krosnick, J. A. (2018). Questionnaire design. In D. L. Vannette & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of survey research (pp. 439–455). Springer.

- Maggioni, I., Sands, S., Kachouie, R., & Tsarenko, Y. (2019). Shopping for well-being: The role of consumer decision-making styles. Journal of Business Research, 105, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.040

- McKinsey. (2022, March 31). The state of grocery retail 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022, from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/state-of-grocery-europe-2022-navigating-the-market-headwinds

- McKinsey. (2023). The state of grocery retail 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2023, from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/state-of-grocery-europe

- Mittal, B. (2017). Facing the shelf: Four consumer decision-making styles. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 29(5), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2017.1318732

- Nayeem, T., & Marie-IpSooching, J. (2022). Revisiting Sproles and Kendall’s consumer styles inventory (CSI) in the 21st Century: A case of Australian consumers decision-making styles in the context of high and low-involvement purchases. Journal of International Business Research and Marketing, 7(2), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.18775/jibrm.1849-8558.2015.72.3001

- NielsenIQ. (2023, March 30). Grocery shop directory 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2023, from https://www.epressi.com/tiedotteet/kauppa/paivittaistavaramyymalarekisteri-2022.html

- Postnord. (2020). E-commerce in Europe 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.postnord.se/siteassets/pdf/rapporter/e-commerce-in-europe-2020.pdf

- Prakash, G., Singh, P. K., & Yadav, R. (2018). Application of consumer style inventory (CSI) to predict young Indian consumer’s intention to purchase organic food products. Food Quality and Preference, 68, 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.01.015

- PTY. (2023). Finnish grocery trade 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023, from https://www.pty.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Paivittaistavarakauppa-ry-2023_EN.pdf.

- Rezaei, S. (2015). Segmenting consumer decision-making styles (CDMS) toward marketing practice: A partial least squares (PLS) path modeling approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 22, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.09.001

- Rindfleisch, A., Malter, A. J., Ganesan, S., & Moorman, C. (2008). Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(3), 261–279. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.45.3.261

- Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1995). Decision-making style: The development and assessment of a new measure. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55(5), 818–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164495055005017

- Seitz, C., Pokrivčák, J., Tóth, M., & Plevný, M. (2017). Online grocery retailing in Germany: An explorative analysis. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 18(6), 1243–1263. https://doi.org/10.3846/16111699.2017.1410218

- Seo, S., & Moon, S. (2016). Decision-making styles of restaurant deal consumers who use social commerce. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(11), 2493–2513. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2015-0319

- Shen, H., Namdarpour, F., & Lin, J. (2022). Investigation of online grocery shopping and delivery preference before, during, and after COVID-19. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 14, 100580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2022.100580

- Sinkovics, R. R., ‘Mink’leelapanyalert, K., & Yamin, M. (2010). A comparative examination of consumer decision styles in Austria. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(11–12), 1021–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2010.508974

- Spector, P. E. (2019). Do not cross me: Optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8

- Sproles, G. B., & Kendall, E. L. (1986). A methodology for profiling consumers’ decision-making styles. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 20(2), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.1986.tb00382.x

- Srinivasan, S. S., Anderson, R., & Ponnavolu, K. (2002). Customer loyalty in e-commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Retailing, 78(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00065-3

- Statista. (2023a, June 6). Online grocery & beverage shopping by store brand in Finland as of March 2023 [graph]. Retrieved June 8, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1188038/online-grocery-shopping-by-store-brand-in-finland

- Statista. (2023b, March 17). Skill ranking of Nordic countries in technology in 2022 by B. Thormundsson. Retrieved January 18, 2024, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1370539/technology-skill-ranking-nordic-countries/#statisticContainer

- Statistics Finland. (2022). Use of information and communications technology by individuals 2022. Retrieved August 30, 2023, from https://stat.fi/en/publication/cku3yt0e0b8ld0b99wvwmsfis

- Stenius, M., & Eriksson, N. (2023). What beliefs underlie decisions to buy groceries online? International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(3), 922–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12874

- Thangavel, P., Pathak, P., & Chandra, B. (2022). Consumer decision-making style of Gen Z: A generational cohort analysis. Global Business Review, 23(3), 710–728. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150919880128

- Thomas, T. W., Gunden, C., & Gray, B. (2013). Consumer decision-making styles in food purchase. Agro Food Industry Hi Tech, 24(4), 27–30.

- Tyrväinen, O. P., & Karjaluoto, H. (2022). Online grocery shopping before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analytical review. Telematics and Informatics, 71, 101839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2022.101839

- Van Droogenbroeck, E., & Van Hove, L. (2020). Intra-household task allocation in online grocery shopping: Together alone. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 56, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102153

- Van Droogenbroeck, E., & Van Hove, L. (2021). Adoption and usage of E-Grocery shopping: A context-specific UTAUT2 Model. Sustainability, 13(8), 4144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084144

- Van Hove, L. (2022a). Consumer characteristics and e-grocery services: The primacy of the primary shopper. Electronic Commerce Research, 22(2), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09551-x

- Van Hove, L. (2022b). Survey-based measurement of the adoption of grocery delivery services: A commentary. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 176, 103798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2023.103798

- Walsh, G., Hennig-Thurau, T., Wayne-Mitchell, V., & Wideman, K.-P. (2001). Consumers’ decision-making style as a basis for market segmentation. Journal of Targeting Measurement & Analysis for Marketing, 10, 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740039

- Ytreberg, N. S., Alfnes, F., & Van Oort, B. (2023). Mapping of the digital climate nudges in Nordic online grocery stores. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 37, 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2023.02.018

- Zeithaml, V. A., Leonard, L. B., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299606000203