Psychological Inquiry has been at the forefront of advancing theory in psychology since it emerged in 1990. Under the leadership of past editors, the journal has played a pivotal role in shaping our understanding of key topics such as self-regulation, affective science, altruism, mindfulness, evolutionary psychology, basic needs, emotional intelligence, narrative psychology, and the intersection of health and religion. As the incoming editor, my goal is to build upon this foundation and maintain the journal’s high standard of excellence while also ushering in a new era of theoretical innovation and transparency. In this editorial, I aim to provide insight into the inner workings of Psychological Inquiry and highlight our commitment to promoting equity and diversity in the field.

The Origins

In the 1980s, Lawrence Pervin had an idea to start a new theory-oriented journal. In many ways, Pervin was ahead of his time. Unsatisfied with the limited opportunity of journals in psychology to exchange ideas, and possible biases that emerge through censorship of ideas, the core idea driving Psychological Inquiry has been to advance psychological knowledge through an open debate with one’s peers. Pervin’s original idea was to provide a platform for diverse branches of psychological science, similar to the open peer commentary platform that emerged for cognitive scientists, philosophers of mind, and neuroscientists in Behavioral and Brain Sciences a decade earlier. The chief reason to move away from a traditional anonymous peer review for a theory-oriented journal is quite simple: beyond logical consistency and narrative style, ideas and theories are notoriously hard to evaluate. When is a “theory” a real theory? How can one distinguish between inter-related concepts? When should one give up or update a given theory? These are complex questions, with ideological biases and cultural Zeitgeist often favoring those that conform to one’s beliefs over those that don’t.

The standard format in psychological journals continues to rely on reviews from a handful (often just two or three) anonymous experts. Consequently, there is a good chance that some ideas never see the light of day. Ideas and theories that luckily survive such a review process convey a sense of consensus that may not be warranted. Finally, despite many social psychological benefits of providing anonymous feedback, this process also introduces intellectual inefficiencies: In the process of appeasing reviewers, one may spend a great deal of time looking for a way to accommodate the odd comment from “Reviewer 2.” Moreover, when feedback from one’s peers remain hidden, many intellectually-stimulating commentaries are lost to the public eye. These points of critique of the business-as-usual publication model in psychology have become central to many contemporary debates in the Open Science movement (e.g., Engzell & Rohrer, Citation2021; Gross & Bergstrom, Citation2021; Nosek & Bar-Anan, Citation2012; Open Science Collaboration, Citation2015; Vazire, Citation2018). They also continue to motivate the open peer review mission of Psychological Inquiry—one of the first journals implementing an open peer review approach in psychological sciences.

Top Hits and Themes Over Time

The first issues of the journal included target articles on topics that continue to be debated in psychology, including replicability as a criterion for appraising and amending theories (Meehl, Citation1990), fundamentals of stress management (Lazarus, Citation1990), and the role of intentionality for consciousness (Lewis, Citation1990). Pervin handed over the reins to Constantine Sedikides and Roy Baumeister several years later, who in turn passed the torch to Leonard Martin and Ralph Erber. Under their leadership, the journal made a strategic shift toward advancing theories in social and personality psychology. Due to their stewardship, within a decade the journal had become a widely recognized name in the field of psychological science. More recent editors Ronni Janoff-Bulman and William Cunningham have continued to uphold this legacy of excellence by publishing cross-disciplinary theories and fostering a community of scholarly inquiry.

In its three decades of publication, Psychological Inquiry has consistently pushed the boundaries of psychological theory. From its early days, the journal has featured book review essays from leading cognitive, social, and personality psychologists, such as the widely debated “The Person and the Situation” by Ross and Nisbett (Citation1991, also see their rejoinder to commentaries in 1992). Additionally, the journal has devoted entire issues to exploring specific themes, including motivated cognition, religion and psychology, the wisdom of social psychology, political psychology, and intuition. Under the leadership of Martin & Erber, Psychological Inquiry also produced a special issue on “Modern Classics in Social Psychology” (Citation2003), in which several scholars nominated transformative ideas and theories that have shaped the field.

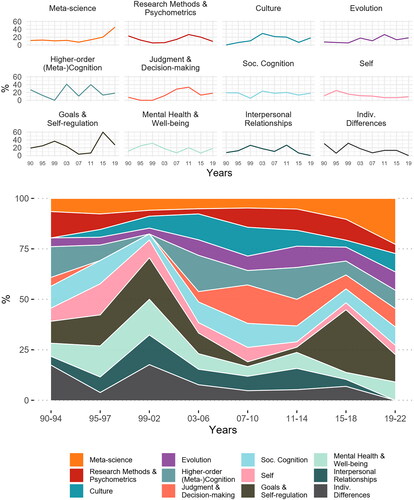

What are the common themes featured over time? To address this question, I examined keywords, titles, and abstracts of the target articles, first determining common topics and subsequently calculating relative weight of twelve most frequently mentioned topics over time. shows themes which have dominated the discourse so far. Constant features are the topics of motivation (incl. needs and goals) and self-control, cognitive processes and their meta-cognitive regulation, mental health and well-being, individual differences and social cognition, as well as theoretical issues concerning research methods in psychology. Dominance of some themes reflects the Zeitgeist. The topic of meta-science—present in the journal since the first issue—become especially prominent in the last decade of Open Science movement. On the other hand, the topic of mental health and well-being was pronounced around the time of the discussions about well-being and the subsequent emergence of the Positive Psychology field in late 1990s-early 2000s. In the new millennium, cultural diversity and related societal issues became salient, with the trend continuing to this day. Further, judgment and decision-making made a big entry in the last 15 years, possibly due the Nobel Prize in economics to Kahneman in 2002, and greater focus on behavioral economics thereafter.

Figure 1. Top 12 themes featured in target articles in Psychological Inquiry over time. Individual trajectories (percentage across issues in a given time period) on the top; percentage-adjusted area chart on the bottom. Themes identified via categorization of keywords, titles, and abstracts. In the first step, we identified twenty most common topics; other topics not featured in the graph are: Emotion, Affect and Cognition, Meaning-making & Narratives, Groups & Identity, Personality Structure & Development, Stress & Coping, Stereotypes & Prejudice, Human Development, and Political (ordered based on frequency). For ease of interpretation, articles are binned into eight temporal groups reflecting four-years each.

Toward Greater Equity and Diversity of Submissions

The original idea behind Psychological Inquiry—a dialogue through open peer exchange about contentious ideas and theories—remains as important today as it was over three decades ago. Interdisciplinary research is on the rise (Van Noorden, Citation2015). Therefore, concepts and theories have an opportunity to be enriched by perspectives coming from different fields of studies. At the same time, intellectual silos and cultural echo-chambers remain—while more scholars today work in interdisciplinary teams of specialists than before (“Why Interdisciplinary Research Matters,” 2015), focus on specialization can also produce intellectual silos within one’s discipline. Such silos are often not conducive to the cumulative advancement of science. Scientific silos may be especially damaging for psychology (Cacioppo, Citation2007), where theoretical approaches touch on many neighboring disciplines, from anthropology and economics, to biology, linguistics, and neuroscience, to philosophy and education, to sociology and political science, to health studies, and so on (Boyack, Klavans, & Börner, Citation2005). Scholars connecting closer to one of the neighboring fields may diverge in their grand theories, favor methodological paradigms others may find peculiar or simply be unfamiliar with, and develop their own jargon, all contributing to confusion about the concepts, methods, and evaluation of the results. How can we combat such disciplinary isolationism? An idea pursued by Psychological Inquiry since its inception has been to provide scholars with an opportunity for a civil discussion and debate of diverse ideas, and promoting a dialogue to clarify misunderstandings about theories, methods, or interpretation of core results.

Notably, diversity of ideas is unlikely to emerge without reckoning with the possible blind spots and biases in our field. Though scholars have pointed out lack of diversity in participants in psychological studies (and thus models for human behavior) throughout twentieth century (e.g., Sears, Citation1986), only in the last decade the issue of limited diversity in studied participants came to the forefront of discussions about how to improve generalizability of our theories and phenomena. As Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan (Citation2010) pointed out, for most psychological studies in the twentieth century, the modal participant in psychological research has been a white college student at an elite American college. A decade since their influential paper on how nine out of ten participants in psychological research came from Western, English-Speaking, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) countries, the issue with lack of sampling diversity remains (e.g., Cheon, Melani, & Hong, Citation2020; Hruschka, Medin, Rogoff, & Henrich, Citation2018). Platforms of online crowdworkers (e.g., Amazon Mechanical Turk or Prolific Academic) taking part in surveys and experiments for modest remuneration have helped to expand psychological research beyond college students, but also introduced structural inequalities and new limitations: such crowdworking platforms are less available in the Global South, with a few exceptions rely on higher English language proficiency, and restrict the scope of studied phenomena to those that can be administered online.

Two related blind points that researchers pay insufficient attention to concern the situated nature of psychological phenomena in cultural (e.g., Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991; Shweder, Citation1991), and historical contexts (Gergen, Citation1978; Muthukrishna, Henrich, & Slingerland, Citation2021; Varnum & Grossmann, Citation2021; Vygotsky, Citation1978). For many psychological scientists like myself, it appears self-evident that most psychological phenomena are constrained through culturally- and ecologically-mediated beliefs, habits, patterns of socialization and practices. And whenever culture changes, changes in the inner workings of phenomena often follow suit. Yet beyond lip-service to the importance of considering theoretical implications of these insights, much of our field appears more fascinated by phenomena that claim universality rather than cultural or temporal specificity. We often take phenomena that may be unique to a specific context (often the United States) and present their inner workings as psychological universals. And if we do entertain the idea of cultural context, it is as often as a “moderator” of phenomena—i.e., a variable that is theorized to be separate from the phenomenon one aims to explore rather than as part of the system it is embedded in (see Barrett, Citation2022, for an example why this approach may be misleading). Finally, consider discussions about topics such as social class and inequality, polarization, education, or mental health: A “WEIRD” account of a given psychological phenomenon often emerges as a dominant one, the one to compare other accounts against. As a result, non-WEIRD scholars have a harder time presenting equally valuable insights concerning different inner working of a given phenomenon in their cultural context.

These observations about limited diversity in our field have implications for the advancement of theory in psychology. If the model of human behavior is based on an American college student or an online crowdworker, theories resulting from such model are unlikely to be generalizable to human psychology writ large. Furthermore, such decontextualized theories are unlikely to stand the test of time. Moreover, they are unlikely to produce causal models that accurately predict human behavior outside of the confines of some specific laboratories at American universities. Indeed, reliance on existing psychological theories did not provide much advantage for accuracy of predictions (Hofman et al., Citation2021) in the Forecasting Collaborative—a big team science initiative of 120 scientific teams providing estimates of societal change in well-being, sentiment on social media, political trends, or racial and gender bias during the first year of COVID-19 pandemic in the US (Grossmann et al., Citation2023).

How to foster diversity in psychological theory? One step to address this question includes actively seeking out and amplifying voices and perspectives that may have historically been underrepresented. This includes but is not limited to diversity due to geography, language, region, ideology, race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, or gender. Another step involves considering whether the themes and topics covered in Psychological Inquiry reflect a diverse range of perspectives and ideas, particularly those that may originate outside of North America. And yet another step involves being mindful of status-related inequalities that may limit representation in the field. These include disparities in institutional prestige, academic rank, or structural inequalities that exist in society. By acknowledging and actively working to address these issues, we can create a more inclusive and equitable psychological community.

Because Psychological Inquiry strives to cover four topics (each in their own target issue) per year, issues of diversity and equity in representation of covered topics appear especially pressing. Below, I will discuss several innovations my Editorial Team will introduce to help democratize the submission process, with a goal to move the needle toward greater fairness, while also keeping an eye for capturing opinions from scholars of different career stage and from different parts of the globe.

Updates on Editorial Practices

My primary objective as the incoming editor is to continue to publish the kinds of exciting, discussion-worthy articles that have made the journal a success in the past. I will also continue to rely on some of the same editorial criteria in making decisions about submissions: Is the issue touching on a subject worth discussing? Are there different positions on the proposed topic scholars in psychological science don’t agree on? Does the target article present a topic of broad interest beyond a narrow sub-discipline in psychology?

At the same time, as outlined above, in the time of disciplinary isolationism and on-going discussions about transparency, equity, and diversity in perspectives, my editorial team will introduce a set of changes. First, I hope to widen the interdisciplinary scope of the journal. The journal is well positioned in personality and social psychology, but it appears not to be much on the radar of scholars from clinical psychology, developmental psychology, as well as quantitative psychology. This observation stands in contrast to the early days of the journal, when Psychological Inquiry included papers from Paul Meehl, Robert Lazarus, and other luminaries in these fields. Surely, scholars in clinical, developmental or quantitative psychology today do not see eye to eye on everything and there are topics worth discussing in an open-peer review format, beyond narrow disciplinary hallways! In short, I am very much looking forward to submissions of proposals for target articles from scholars who do not necessarily self-identify as social or personality psychologists.

Second, instead of mostly relying on the invitation-only mechanism for selecting target articles, as done in the past and by some other eminent theoretical outlets, I hope to expand the number of target articles based on submitted proposals—a process that started with my predecessor Wil Cunningham. And I especially welcome submissions from scholars representing non-WEIRD regions. Third, I have developed a proposal submission form that introduces greater systematicity and comparability of different proposals. Fourth, I introduce a novel multi-step review process, while keeping an eye on minimizing delays in the publication process. I elaborate on the latter two innovations below.

Target Article Proposal: Consider the Issue You Aim to Debate

This proposal form aims to structurally guide the authors of prospective proposals, asking them to consider if the issue is indeed of broad interest to psychological science writ large, whether it is sufficiently controversial (i.e., if there are distinct, conflicting positions on a given topic) to merit publication in Psychological Inquiry rather than a different theoretical outlet, and whether the topic is sufficiently distinct from recent coverage in our or similar journals. Critically, the proposal form is structured in a way that requires authors to think about the whole target issue rather than their paper in isolation: Who are possible candidate commentary writers who will disagree with your position? Are prospective commentary writers chiefly coming from a handful of English-speaking countries in the Global North? What about their gender, and status distribution?

In the proposal form, authors will also be required to suggest at least six (and no more than twelve) possible commentary writers, while simultaneously considering their geographic, gender-, and status-related diversity. We will prioritize proposals that touch on complex, controversial topics worth a civil debate, and aim for greater diversity in possible commentaries. Through these changes, I hope to keep some of the systemic biases in our discipline at bay. Further, I hope the reflection on the questions in the proposal form will help guide prospective authors when figuring out if their idea is best suited for Psychological Inquiry or rather other outlets publishing state-of-the-art programs of research. Finally, as you may realize by now, this process aims to help us work together with the prospective authors on creating a target article worth discussing in the broad psychological science community. Because of the multi-step review process below, I encourage prospective authors to develop their ideas incrementally, receiving feedback on proposals from the editorial team. Talking to the previous editors, it appears that submitting fully developed manuscripts at the proposal stage (often written for other outlets) is less likely to produce impactful articles.

Under the Hood: The Multi-Step Review Process

Because of the reliance on proposals to help select debate-worthy ideas, as well as the open-peer review format of the journal, the updated editorial process diverges from what is expected in some other psychological journals. Specifically, we employ an efficient multi-step review process:

In the first step, proposals for target issues are evaluated by at least three reviewers, who provide expert perspective on the general idea and its fit for the key goals of the journal. This is the stage at which we reject most proposals.

In the second step, selected proposals are invited to write a full manuscript, working together with the editorial team to ensure clarity of arguments and their effective presentation. The full proposal will be sent out for one more round of review. Notably, this review step is chiefly aiming to ensure narrative clarity and fairness in presentation of different theoretical approaches—the goal is to avoid misunderstandings while maintaining ethical principles Psychological Inquiry subscribes to. Even if the reviewer personally disagrees with the position taken by the authors, the paper may be accepted for further open-peer review debate in the next stage.

In the third step, we invite up to 12 commentaries on the accepted articles, with commentary writers selected by the editorial team based on their expertise, as well as equity and diversity considerations outlined above. In selecting commentary writers, we balance nominations in the accepted proposal with external perspectives suggested by editorial board members. This step generates a range of open peer review perspectives—each having a potential to be an influential part of the debate in its own right. A brief note about these commentaries—they provide a unique platform for scholars to express their expert opinions and perspectives. In fact, I consider them to be just as important as the target articles themselves. As a commentary writer, you will have the opportunity to delve deeper into the topic at hand and offer your unique insights and analysis. In the past, we have seen many commentaries become some of the most widely read and impactful articles in the journal.

In the final step, the original authors write a response to the commentaries, aiming to further clarify and refine their theoretical argument(s), while identifying points of convergence and divergence from their peers. The rejoinder article is an essential component of the open peer review process in Psychological Inquiry. It provides the opportunity for authors of target articles to address the comments and critiques raised by the commentary authors and to further refine their ideas. In an ideal scenario, the writer of the target article may change their mind about certain aspects of their work or gain a deeper understanding of the topic as a result of the feedback received. This evolution of thought is not only valuable for the author but also for the readers, as it allows us all to see ideas develop over time. Furthermore, it is also an opportunity to see how the scientific process works, from the original idea to the sometimes heated and critical discussion, to the eventual refinement of the idea. In this way, the open peer review format offers a transparent and comprehensive examination of the research, ultimately leading to a more mature understanding of concepts, phenomena, and theories in our field.

Incremental stages in this structuring review process aim to increase efficiency (e.g., initially reviews are focusing on short proposals rather than lengthy manuscripts; final manuscripts are not aiming to satisfy all positions in the field) while maintaining quality. Most importantly, while maintaining a civil form of a candid debate, this review process will enable authors to present their perspective with minimal censorship by gatekeepers.

It is not uncommon to hear feedback from colleagues that reading Psychological Inquiry is both enjoyable and thought-provoking. My goal as the editor is to make sure that more and more people share this sentiment. To achieve this, we need the continued participation of our esteemed authors and reviewers in submitting their best theoretical ideas and providing insightful commentary on the work of their peers. Together, we can use the platform of Psychological Inquiry to engage in robust and nuanced discussions on complex and often polarized issues, fostering growth and development in our field. Publishing your work in Psychological Inquiry guarantees that it will be read and discussed by leading experts in your field, and is likely to be widely cited. I look forward to working with you to bring the most innovative and impactful ideas to the pages of our journal. So, I invite you to submit your proposals and ideas, and be a part of this exciting journey.

References

- Barrett, L. F. (2022). Context reconsidered: Complex signal ensembles, relational meaning, and population thinking in psychological science. The American Psychologist, 77(8), 894–920. doi:10.1037/amp0001054

- Boyack, K. W., Klavans, R., & Börner, K. (2005). Mapping the backbone of science. Scientometrics, 64(3), 351–374. doi:10.1007/s11192-005-0255-6

- Cacioppo, J. T. (2007, September 1). Psychology is a hub science. APS Observer. Presidential Column. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/psychology-is-a-hub-science/.

- Cheon, B. K., Melani, I., & Hong, Y. (2020). How USA-centric is psychology? An archival study of implicit assumptions of generalizability of findings to human nature based on origins of study samples. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(7), 928–937. doi:10.1177/1948550620927269

- Engzell, P., & Rohrer, J. M. (2021). Improving social science: Lessons from the open science movement. PS: Political Science & Politics, 54(2), 297–300. doi:10.1017/S1049096520000967

- Gergen, K. J. (1978). Experimentation in social psychology: A reappraisal. European Journal of Social Psychology, 8(4), 507–527. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420080407

- Gross, K., & Bergstrom, C. T. (2021). Why ex post peer review encourages high-risk research while ex ante review discourages it. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(51), e2111615118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2111615118

- Grossmann, I., Rotella, A. M., Hutcherson, C., Sharpinskyi, C., Varnum, M. E. W., Achter, S., … Wilkening, T. (2023). Insights into accuracy of social scientists’ forecasts of societal change. Nature Human Behaviour. doi:10.1038/s41562-022-01517-1

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83.

- Hofman, J. M., Watts, D. J., Athey, S., Garip, F., Griffiths, T. L., Kleinberg, J., … Yarkoni, T. (2021). Integrating explanation and prediction in computational social science. Nature, 595(7866), 181–188. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03659-0

- Hruschka, D. J., Medin, D. L., Rogoff, B., & Henrich, J. (2018). Pressing questions in the study of psychological and behavioral diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(45), 11366–11368. doi:10.1073/pnas.1814733115

- Lazarus, R. S. (1990). Theory-based stress measurement. Psychological Inquiry, 1(1), 3–13. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0101_1

- Lewis, M. (1990). The development of intentionality and the role of consciousness. Psychological Inquiry, 1(3), 230–247. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0103_13

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

- Martin, L. L., & Erber, R. (2003). INTRODUCTION: “Classic Contributions to Social Psychology: Now and Then”. Psychological Inquiry, 14(3), 191–192. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2003.9682877

- Meehl, P. E. (1990). Appraising and amending theories: The strategy of Lakatosian defense and two principles that warrant it. Psychological Inquiry, 1(2), 108–141. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0102_1

- Muthukrishna, M., Henrich, J., & Slingerland, E. (2021). Psychology as a historical science. Annual review of Psychology, 72(1), 717–749. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-082820-111436

- Nosek, B. A., & Bar-Anan, Y. (2012). Scientific Utopia: I. Opening scientific communication. Psychological Inquiry, 23(3), 217–243. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2012.692215

- Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716–aac4716. doi:10.1126/science.aac4716

- Ross, L. D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1991). The person and the situation: Perspectives of social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Ross, L. D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1992). Perspectives on personality and social psychology: Books waiting to be written. Psychological Inquiry, 3(1), 99–102. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0301_25

- Sears, D. O. (1986). College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow data base on social psychology’s view of human nature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(3), 515–530. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.3.515

- Shweder, R. A. (1991). Thinking through cultures: Expeditions in cultural psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Van Noorden, R. (2015). Interdisciplinary research by the numbers. Nature, 525(7569), 306–307. doi:10.1038/525306a

- Varnum, M. E. W., & Grossmann, I. (2021). The psychology of cultural change: Introduction to the special issue. The American Psychologist, 76(6), 833–837. doi:10.1037/amp0000898

- Vazire, S. (2018). Implications of the credibility revolution for productivity, creativity, and progress. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 13(4), 411–417. doi:10.1177/1745691617751884

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (C. Michael, Ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Why interdisciplinary research matters (2015). Nature, 525(7569), 305–305. doi:10.1038/525305a