Abstract

This article investigates the relationship between a marginalised community of essential workers and dominant models of participation. I focus on Agri-Care, The Royals, and Alien Species, projects created in collaboration between Eastern European seasonal agricultural workers in Jersey and the artist Alicja Rogalska, and analyse them through a productive confrontation with theories of participation. I begin by juxtaposing Jacques Rancière’s ideas of aesthetic regime as interpreted by Claire Bishop, to Rogalska’s sculpting workshops conducted with Jersey Royal potato pickers. I argue that Rogalska shifts the aesthetic experience from audiences onto participants, repositioning ‘unskilled’, manual labour as craft, and uncovering seasonal workers as craftspeople, holding expertise. As a result, Rogalska disassembles the idea of low-skilled labour. The article then confronts Miwon Kwon’s ideas of a disobedient community with Rogalska’s making of a community, ostensibly coherent and ‘compliant’ but subverting the fleeting group of temporary workers into a permanent precariat, the backbone of the local economy. The participatory process and its subsequent introduction into the local archives, I argue, impose a different relation between permanent and temporary locals of Jersey, with the latter now embedded into local institutions. I end by considering why these participatory projects seem incompatible with theories on participation and suggest this incompatibility stems from the arts’ preoccupation with virtuosic labour. The concept of artists as the ultimate precarious workers of late-capitalism, I argue, excludes the communities at the extreme of late capitalist exploitation from artistic attention and the scope of art subsidy, depoliticising art practice in the process.

Hundreds of bodies stand squashed, slowly nudging towards a big glass door. The group is not uniform: there are men and women, young people and old, piercings, tattoos, slouchy track pants, and long linen skirts. Almost all bodies carry backpacks; one disappears behind taped-up laundry bags. Most faces are hidden behind masks, creating anonymity, a mass of people where a multitude of individuals may have been. There is a sense of stress and rush, of warm damp air penetrating through the masks, heightening the discomfort.

Closer to the glass door, a queue has formed, but how it moves is not clear. Some stand far apart, others gather in clusters, pushing forward. The entrance to the building is guarded by a different figure, someone who appears to be in charge. Dressed in a white protective suit, eyes hidden behind wide plastic goggles, they hold an instrument, pointing it menacingly at the person just outside the door. The device hovers millimetres above the forehead, suspenseful. This is where the photo is exhausted, the limits of documentation reached too soon. This is where lived experience fills in the gaps: one long beep, then the person is let in, and the thermometer pointed at the next body in line. Another image reveals a glimpse from the other side of the door, the caption clunky but revealing: ‘Romanian seasonal workers traveling to Britain, wait in line for check in on two London bound flights, in Bucharest, Romania’.Footnote1 The date is 8 May 2020.

In this essay, I follow these seasonal workers, and others like them, to their workplaces. I discuss projects created in collaboration between artist Alicja Rogalska and temporary agricultural workers in Jersey and consider how these projects disassemble the idea of low-skilled labour, how they position temporary migrants as a permanent part of the local community, and what they reveal about the relationship between participatory projects and marginalised communities. To do this, I put Rogalska’s work in a productive conflict with different theories of participation: those locating its political potential in the aesthetic experience (represented here by Claire Bishop), those finding its activist agency in the process of community formation (exemplified by Miwon Kwon), and those emphasising the relationship between labour and participation (including Bojana Kunst and drawing on Paolo Virno). My aim is to articulate ways in which dominant modes of participation are designed to hide communities at the extreme end of capitalist marginalisation from view. This, I argue, indicates that the mainstream approaches to participation, which are now central to subsidy, are in fact tools of art’s depoliticization.

Two key terms I employ – ‘Eastern European’ and ‘low-skilled’ – both have UK-specific meanings. ‘Eastern European’ refers to a heterogeneous group of immigrants from former Eastern Bloc, Yugoslavian, and Soviet republics, many of them now European Union (EU) citizens; the group is ascribed a uniform, marginalising identity, constructed when the historically imagined characteristics of Eastern Europe are attributed to immigrants.Footnote2 This is an identity rehearsed by the media, which has imagined Eastern Europeans as lacking morals,Footnote3 abusing the welfare system,Footnote4 undercutting salaries,Footnote5 and engaging in activities such as swan-eating.Footnote6 ‘Low-skilled’ refers to a category of work invented through policy in relation to ‘level of education, income, sector of work or a combination of the three’;Footnote7 in the UK, these regulatory choices were connoted to migration, with the aim to ‘frame those who become low-skilled migrants as undesirable’.Footnote8 In qualitative research on public perceptions of low-skilled work, Alexandra Bulat finds the results of this policy in practice: ‘British interviewees drew attention to how “Eastern European” almost becomes a euphemism for “low-skilled” in local narratives’, while Eastern Europeans ‘personally experienced this association, often after disclosing their nationality to British people’.Footnote9 In Brexit Britain, being Eastern European means being untrained, uneducated, unethical, unable to speak good English, and earning very little.

The Beauty of a Potato: Aesthetics of Participation

The case study at the centre of this article is the collaboration between Alicja Rogalska and the seasonal agricultural workers in Jersey, many of whom, like the artist, are Polish. The project evolved between October 2017 and November 2019; Rogalska travelled to Jersey for several short residencies and kept in touch with local collaborators in between. Three pieces were created as a result. The Royals, a short film, documents the clay workshops Rogalska conducted with the participants; Agri-Care consists of a bronze potato sculpture () awarded to the best migrant employer in Jersey and a list of criteria for awarding the prize, authored by the agricultural workers; Alien Species: Jersey Migrant Worker Archive is a collection of images and videos created by the workers, capturing their day-to-day.Footnote10 In November 2019, all three projects were presented at an exhibition titled Invisible Hands at the Berni Gallery in Jersey.Footnote11

Rogalska’s practice is research-led and interdisciplinary, spanning performances, videos, and installations frequently made through community collaborations: in the past, she has made work on legal fictions with immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers who trained as lawyers,Footnote12 and explored citizenship with ‘the erased’, a group stripped of Slovenian citizenship during the breakup of Yugoslavia.Footnote13 She has exhibited internationally including at Manifesta 14 (2022), Kunsthalle Bratislava (2021), and Kunsthalle Wien (2021); previously based in London, she recently relocated to Berlin, where she was the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin fellow in 2020–2021. Rogalska was invited to Jersey by The Morning Boat, a residency programme, which focused on site-specific work for ‘public spaces and every-day working environments, in collaboration with local communities’;Footnote14 the thematic focus was on agriculture, finance, and tourism, as the three main strands of the local economy.

On a representational level, The Royals and Agri-Care revolve around the product at the centre of participants’ lives, Jersey Royal potatoes.Footnote15 The potato has been grown on the island for over 140 years and, due to local weather and soil, can be harvested between March and July.Footnote16 It is also grown on coastal slopes, rather than in flat fields; as a result, much of the farming is still done manually, on land inaccessible to mechanical equipment.Footnote17 The amount of manual labour required to mass produce potatoes in such conditions has meant a long tradition of seasonal agricultural workers in Jersey. As I elaborate later in the article, for over two decades, this workforce has been predominantly Eastern European.Footnote18

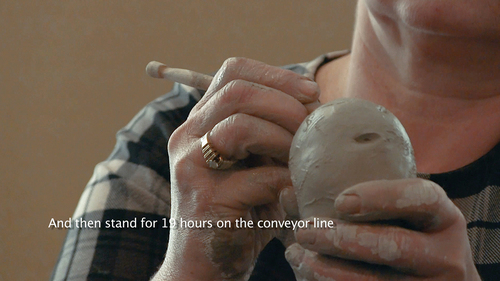

Rogalska’s collaboration with the migrant workers is not, however, grounded in the overt exploration of these facts and is instead narrowly focused on the small, brown, kidney-shaped potato itself. In workshops, collaborators sculpted replicas of the potato from clay, using techniques of tactile memory rather than a model. The Royals consists entirely of close-ups that follow this creative process; only hands and sculptures-in-the making are ever shown (). Visually, the work is focused on the colours, movements, and textures that shape the participants’ everyday. The muddy brown of the clay invokes the muddy soil outside; the close-ups of hands sculpting recall the gestures and movements of farming, in part because many of the clay potatoes look convincing; even the sound of clay being manipulated brings to mind the sound of damp ground moving under boots. What is being centred is the personalised, human- rather than machine-produced nature of the two potatoes, the produce and the sculpture. The aesthetic choices and processes, from the tactility of sculpting to the close-ups of the film, turn the Jersey Royals from a bog-standard food item into a hand-crafted object made by specialists, food grown through skills and knowledge.

If this project was described in theoretical terms, it would be a prime example of what Claire Bishop called ‘the social turn’ in visual artsFootnote19 – a shift towards practices ‘in which people constitute the central artistic medium and material in the manner of theatre and performance’,Footnote20 which ‘overturn the traditional relationship between the art object, the artist, and the audience’.Footnote21 Bishop was not a fan of how these works emphasise the process of collaboration over the artistic product: she argued that this emphasis turns art from an aesthetical into an ethical practice, in which all community work is seen as ethically sound and socially engaged and aesthetics is relegated to the realm of reactionary elitism.Footnote22 In opposition to this view and drawing on the work of Jacques Rancière, Bishop argued that aesthetics is not a formal category but ‘a specific mode of experience, including the very linguistic and theoretical domain in which thought about art takes place’.Footnote23 Aesthetics is relational and experiential and includes the ‘questioning of how the world is organised, and therefore the possibility of changing or redistributing that same world’.Footnote24 De-commissioning aesthetics is therefore decommissioning the experience of art and the only location of politics facilitated by art. This idea of aesthetics as relational and political also appears in theatre research: Adam Alston argued that participation in immersive performance induces introspection, ‘as attention is turned toward an experience that is produced within the body and constituted by the audience as art in dynamic relation to an immersive environment’.Footnote25 Meanwhile, Gareth White suggests leaving politics aside, not to ignore it but to ‘identify […] formal characteristics and […] media [of participatory theatre] in a way that is at least in one sense prior to the discussion of politics’.Footnote26 All three researchers centre the relationship between the participatory project and audiences, the specifically artistic experience facilitated by the piece, understood as the locus of the aesthetic and the location of political potential.

If aesthetics is not confined to representation but expanded to an artistically engendered experience, then Rogalska uses participation to create a personalised aesthetic experience for both her collaborators and external audiences. This is an experience of turning what is regarded as unskilled manual labour into a delicate craft that requires the expertise of an individual artist and not the mere body and strength of a faceless mass of seasonal workers. In The Royals, the aesthetic experience of individualisation and skill-elevation is manifested for external audiences through the attention brought to each craftsperson and their hands. The film never shows any faces or other body parts and yet reveals much about both the group and the individuals who make it. Age becomes a distinguishing feature, inscribed on the skin through lines, dryness, or smoothness; gender occasionally reveals itself. As the camera moves from one pair of hands to another, different images of the group are conjured up: young women appear to be in the majority, then middle-aged women, and then a congregation of middle-aged men appears as if dispersed through the space. One sculptor has long, perfectly shaped, pointed nails, each painted a different, elaborate, multicoloured pattern (). As she sculpts, the time devoted to the intricate design comes into view as does the effort it must take to maintain it. A wedding ring appears in the shot, and with it questions of families separated (); in the background, a pair of hands fumbles uncomfortably with the clay as if slightly disgusted. A man is creating a perfectly symmetrical sculpture; next to him, a woman is working on a calloused potato full of bumps, full of details. Someone is seen manipulating the clay like dough, in rough but rhythmic movements; someone else adds delicate details to the potato with a sharp, pen-like tool, stopping to check as they work. There are earnest laughs and sarcastic laughs, confident, and timid voices.

Where Eastern European seasonal workers are usually depicted as a mass, as in the photo caption from the start of this article, the aesthetic experience of crafting achieves individualisation, turning a homogenised mass into a multitude of individual Eastern European craftspeople holding the fame of the Jersey Royals in their skilled hands. In a promotional film by the Jersey Royal Company, all wide shots of sloping fields and sunny horizons, the soil is populated by an anonymised, indistinguishable workforce.Footnote27 The Royals inverts this visual language until the anonymous workforce displaces the central focus from the produce to the individual Eastern European craftsperson. Individualisation and de-homogenisation are imprinted not just on the workers, but also on the idea of Eastern Europeans. Rather than arguing that Eastern Europeans are not low-skilled, this project dismantles the very idea of low-skilled work, turning the seasonal workers from a movable, untrained workforce, into a skilled community of craftspeople, manipulating the ground.

Rogalska’s focus on craftsmanship also acts as a challenge to the common ideas about agricultural work, in a manner that speaks directly to a wider artistic community. Jen Harvie positions craftsmanship as a technique against neoliberal impositions:

Craftsmanship offers the positive values of quality workmanship, concern with quality over quantity, self-respect and satisfaction for the worker and a healthy integration of thinking and making, where good ideas are worked out and refined in their material realization. All of these qualities point to craftsmanship’s demands as time-consuming and, often, difficult. It relies on the trained practice that leads to dependable skill rather than unreliable ‘sudden inspiration’ […]. It prioritizes not efficiency and productivity but, simply, quality.Footnote28

Harvie is speaking about art production rather than manual labour. The way craftsmanship is employed in the Jersey projects, however, allows for an explicit connection to be made between discourses on neoliberalised art and the realities of seasonal agricultural workers. I return to this connection later in the article.

Here, I want to note that conceiving low-skilled work as craft puts Rogalska’s work in conflict with Bishop. The clay potatoes made by Rogalska’s collaborators were left in custom-made honesty boxes, similar to those used by farmers to sell real produce, silently inserting the project into the local economy; the archive material generated through the project remains on the island; The Royals is not publicly available, even if it is occasionally exhibited. The aesthetic experience is reserved for the locals, primarily the collaborators themselves, not the white cube community quietly implicit in Bishop’s writing, transformed through detached observation rather than participation, acting as the privileged recipients of art’s political potential. Rogalska’s work decentralises aesthetics as a gallery-based experience, uncovering Bishop’s disinterest in other communities entangled in participatory projects and raising the question of whether the institutions which share Bishop’s view on aesthetics as politics harbour the same disaffection.

Now You See Me: Temporary Migrants as Locals

The question of who participatory projects are for is a major point of theoretical discussions. Bishop’s criticism of relational aesthetics – a ‘set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context’Footnote29 – included a strong scepticism of their inclusivity. When another critic described Rirkrit Tiravanija’s 1996 piece Untitled (Tomorrow is another day) as a space of refuge, Bishop questioned what might have happened if the gallery ‘had been invaded [sic] by those seeking genuine “asylum”’.Footnote30

The aesthetic regime favoured antagonistic practices, frequently exemplified by Santiago Sierra, Spanish performance and installation artist and a central figure of virtually all deliberations of participation. Sierra’s work is ostensibly a critique of capitalist oppressions from within major galleries and exhibitions, including PS1, Kunst-Werke, or the Venice Biennale. Into these spaces of privilege, his works bring ‘people who were willing to undertake banal or humiliating tasks for the minimum wage’.Footnote31 In Bishop’s interpretation, pieces such as 8 People Paid to Remain inside Cardboard Boxes (1999) make ‘the economic context into one of his primary materials’.Footnote32 The artist’s methods, however, remain outside of the scope of any ethical questioning even if his ‘moulding of “collaboration” into a hiring relationship’Footnote33 rests on the subjugation of marginalised groups, such as undocumented immigrants and wage workers. The white cube community is understood to be unlike the people contracted by Sierra. They are not asylum seekers inside cardboard boxes like in the piece mentioned above,Footnote34 or any of Sierra’s other collaborators: the Iraqi immigrants smothered into polyurethane foam sculpturesFootnote35 or addicts given heroin in exchange for having their heads shaved.Footnote36 In Bishop’s thinking and writing, the participants are ignored, framed either as passive recipients of good artistic intentions or the powerless victims of economic systems exposed by the artist.

This negligence is not characteristic of all theoretical thinking on participation. On the other side of the spectrum to Bishop, researchers put communities at the centre of curatorial considerations. Here, it is aesthetics that is pushed to the side and the relationship between artists, institutions, and communities that is seen as both the location of politics and the main site of political fragility. Within this strand of thinking, researchers emphasise the distribution of authorship and creative agency, the long-term impact of projects, curatorial meddling, or the length and depth of the artists’ relationship to participants. Grant Kester, for example, warned against artists ‘who position themselves as the vehicle for an unmediated expressivity on the part of a given community’ in order to build their cultural, economic and social capital;Footnote37 in response, artist Martha Fleming argued it was the ‘professional-managerial class’ in galleries that was responsible for co-opting both the long-standing work and the politics practised by artists and participants.Footnote38 Miwon Kwon stands at the greatest conceptual distance from Bishop’s ideas. Whereas Bishop discusses participants as artistic material, Kwon argued that the very construction of a community gathered around the project, the process of community-formation, is the central issue of participation and the locus of its politics.Footnote39

In her study, Kwon asserts the standardised approach to community formation prescribes a political outcome, while also contributing to the essentialisation of groups. The ‘unquestioned presumption’ behind community projects, argues Kwon, is that participants share a ‘set of common concerns or backgrounds’ for which they are ‘collectively oppressed by the dominant culture’; the art projects meanwhile serve ‘to address if not challenge this oppression’.Footnote40 Kwon is suspicious of this approach both for how it assumes the existence of ‘fully formed’ communities ‘awaiting engagement from the outside’Footnote41 and for its potential for political amelioration, softening rather than addressing ‘the legitimate dissatisfaction that many community groups feel in regard to the uneven distribution of existing cultural and economic resources’.Footnote42 Instead of presuming the existence of ready-made marginalised but quiet communities, Kwon argues artists should (re)define or (re)establish communities through their work. A community gathered around or for community arts should be:

a provisional group, produced as a function of specific circumstances instigated by an artist and/or a cultural institution, aware of the effects of these circumstances on the very conditions of the interaction, performing its own coming together and coming apart as a necessarily incomplete modeling or working-out of a collective social process. Here, a coherent representation of the group’s identity is always out of grasp. And the very status of the ‘other’ inevitably remains unsettled.Footnote43

Formed by and through the project, Kwon’s community is disobedient: it disagrees with the idea of community art as a force for community good but its work within community art makes this disagreement productive. This suggestion is not without its issues. It might be argued, for example, that it is mostly cultural workers who have the awareness of community art mechanisms required for this kind of participation; the political agency Kwon describes, moreover, frequently accompanies economic and cultural privilege. The idea, however, is of importance for how it unravels any analysis of participation. Before questioning how power, agency, social, and cultural capital are distributed through participation, any such analysis should begin by untangling the process of community formation.

Rogalska’s approach to community formation seems to fit into the reactionary patterns identified by Kwon. There is ‘the isolation of a single point of commonality to define a community’Footnote44 – Rogalska’s participants are identified through their occupation, then narrowed down by nationality, to ensure commonality with the artist. This process, as Kwon predicts, is engineered by art and community institutions: The Morning Boat put visiting artists in touch with ‘local experts, industry representatives and potential collaborators’ and Rogalska’s welcome committee included representatives of The Jersey Royal Company and the local Polish Cultural Centre.Footnote45

This reading, however, only stands if the essentialising label of Polish seasonal workers, implied by the project partners, is accepted. Instead, I argue that summoned together via occupation and nationality, this group reveals itself to be defined primarily by its temporality and ephemerality: the same group can never be brought together again, and workers change not just from year to year, but from one week to another.

This ephemerality is grounded in the migratory patterns of seasonal work and its implications: Rogalska’s collaborators are a community of low-paid, expendable workers with diminished rights. Temporary migration programmes (TMPs), which import seasonal workers via limited and short-term visas, have traditionally been a way for receiving countries to ‘meet labour market demands whilst appeasing electoral concerns over permanent settlement’.Footnote46 The sending countries, meanwhile, use TMPs to amplify the local economy through remittances. For migrants partaking in this economic exchange, however, TMPs generally come with a ‘lack of rights […] in particular the lack of right/route to permanency and citizenship’ and even a slipping towards ‘[i]rregularity as a status’.Footnote47 Recent investigations of working conditions across the European farming sector found repeated examples of hourly wages reduced below legal minimums, unhealthy living conditions, as well as instances of bonded labour and worker exploitation, a situation one EU agricultural trade unionist ascribed to the fact that ‘animals have a better lobby than migrant workers’.Footnote48 The community constituted by Rogalska’s projects are not Polish seasonal workers, but the migrant precariat: they are defined by a lack of rights imparted on them through their migrancy.

The TMP-enabled migrant precariat in the UK has been predominantly Eastern European for several decades. The Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS) started as a student-focused initiative, but gradually shapeshifted into a programme that brought in seasonal Eastern European workers to meet the profit margins of the sector. Between 2007, when Romania and Bulgaria joined the European Union, and 1 January 2014, when citizens of these countries stopped needing UK work permits, the scheme was focused on this A2 workforce to the point where the ‘planned closure of the SAWS in December 2013 […] coincide[d] with transitional controls lapsing for A2 citizens’.Footnote49 Once enough EU seasonal workers stopped needing visas the scheme closed, but arguably continued to be facilitated through EU membership: in 2016, ‘98% of the seasonal workforce [in the UK] were migrants from elsewhere in the EU’.Footnote50 The new post-Brexit seasonal worker visa might shift the demographic makeup of migrant workers,Footnote51 but, as the example from the start of this article indicates, Eastern Europeans remain the first port of call for temporary agricultural vacancies.

This discrepancy, between the externally claimed community essentialisation (Polish seasonal workers) and the internally recognised and publicly practised community identifier (Eastern European migrant precariat), emerges through Rogalska’s work as a point of local conflict that needs to be addressed. Rogalska returned to these projects for almost 2 years, staying in touch with original collaborators and establishing new relationships; the length of this engagement reflects attempts to embed an ephemeral, temporary community into the permanent structures of the island. Alien Species: Jersey Migrant Worker Archive, a physical collection of objects and documents donated and created by the workers, was exhibited as part of Invisible Hands and then deposited in the Jersey Photographic Archive. The plan was to keep the archive open to both the public and to donations from new waves of seasonal workers, a decision which turned the collection into a manifestation of the island’s ongoing relationship to temporary workers. Similarly, the criteria for Agri-Care, the award for best employer, act as an annual barometer of the workers’ position. In 2018, The Morning Boat planned to introduce Agri-Care to the Jersey Farming Conference ‘inviting local employers […] to consider the working conditions of migrant workers and rise to the challenge of becoming the first Agri-Care winner’.Footnote52 Instead, the presentation was removed from the programme after organisers claimed it would have been ‘counter productive [sic] to the aims of the project’.Footnote53 Making the history of temporary migrants a matter of transparent public record and creating a mechanism for improving their future, Alien Species and Agri-Care reject the memory-lapses that erase the individuals essentialised into seasonal workers. Eastern Europeans cease being a replaceable resource, replenished by and for the local economy: they belong to the island, whose permanent community is responsible for their mistreatment.

This radical archivist gesture and the intervention made in the hierarchies of the agricultural industry, however, come at the price of another conflict with major theories or participation. Kwon asks for a hyper-aware heterogeneous community that rejects institutional essentialisations; Rogalska’s work reveals how working through these labels can be politically productive because while art institutions do not necessarily create these essentialising identities they can choose whether to perpetuate them or call them out. Rogalska’s collaborators are a disobedient and heterogeneous community, but these qualities become evident to outsiders because of the participation, rather than being constructed prior to or invented for the participatory project. A compulsory pre-determined disobedience, such as the one suggested by Kwon, would disallow Rogalska’s collaborators, whose disobedience is not externally legible, from artistic participation, removing their marginalisation from institutional view or responsibility.

Artist as a Seasonal Agricultural Worker

The misalignment I have articulated so far, between theories of participation on the one hand and Rogalska’s practice of participation on the other, is more than a point of academic curiosity: as Grant Kester has noted, there has been a ‘growing interdependence between art practice and the academy, and the institutionalisation of “theory” itself’.Footnote54 The way participation is theorised has become the way it is institutionalised, the theory having ‘achieved a near canonical authority in the art world’.Footnote55 If some participatory projects do not fit into the theoretical canon, they, together with the artists and communities involved, will not be welcomed into art institutions. This is particularly important because community engaged practice is now the mainstream of public art funding. Let’s Create, Arts Council England’s 2020–2030 strategy, is focused on community engagement and two out of three sector-wide goals, which all funded organisations must work towards, imply an almost complete shift towards collaborative projects: organisations are asked to engage with ‘Creative People’, who ‘develop and express creativity throughout their life’, and ‘Cultural Communities’, which ‘thrive through a collaborative approach to culture’.Footnote56 In this last section, I deconstruct the conflict between institutional frameworks of participation and Rogalska’s projects in Jersey. I argue that the exclusion of communities that occupy the extreme end of precarity from the interest and reach of art subsidy is not accidental but a by-product of a system built to depoliticise art practice through specific modes of participation.

That this exclusion comes into view from Jersey is perhaps due to the island’s own in-betweenness. Jersey is a self-governing dependency of the UK; it was never part of the EU, but adopted some freedoms of movement, particularly of goods.Footnote57 The island governs migration contained to its territory: as successive UK governments have promised to both increase and decrease quotas for the new seasonal worker visa, Jersey instituted a self-serving post-Brexit immigration system, which effectively prevents long-term settlement, while incentivising precarious seasonal work.Footnote58 Jersey’s art subsidy is separate from the UK’s arts councils and comparatively small: the top annual subsidy of £50,000 per financial year is funded through the Channel Islands Lottery.Footnote59 Other art funders reflect the specificities of the island’s tax haven economy: The Morning Boat was in part supported by the One Foundation, initiated by the CEO of a wealth management company.Footnote60 Jersey is also located off the coast of Normandy; its traditional language, Jèrriais, is closely related to French. On the island of Jersey, the economic dependence on a precarious migrant workforce, the historic relationship to the rest of Europe, and art’s entanglement with neoliberal capitalism all interact in a space small enough to force them into full view.

In the shade of the mainland, the feature that distinguishes Rogalska’s work from mainstream approaches to participation also becomes visible: the Jersey projects do not centre the artist or their labour. The relationship between artistic labour and participation, itself a form of labour, has been central to theoretical debates outlined above and discussed by critics including Jen Harvie, Shannon Jackson, and Helen Molesworth.Footnote61 Harvie is amongst a group of writers who assert that participation ‘can draw attention to exploitative labour trends and other ethical implications arising from delegation’.Footnote62 Sierra’s work, she argues, ‘highlights […] how those who are most economically deprived are most constrained in the “choices” they make about their work’.Footnote63 This replication of harmful labour practices is frequently defended through a conceptual detachment of art practice from the ‘real’ world. Sierra, Bishop claims, only ‘draws attention to the economic systems through which his works are realised’ rather than partaking in them.Footnote64

This ethical hoop-jumping is possible because the artists are not just being bad employers: they are deprivileged workers themselves. The idea that artists trade ostensible job satisfaction and real cultural capital for economic precarity is analysed by Bishop and expanded by others, including Harvie and Bojana Kunst;Footnote65 even Kwon, who argued that mainstream community arts rest ‘on an idealistic assumption that artistic labor is itself a special form of unalienated labor’ allowed this assumption to remain unquestioned, an inbuilt part of the institutional framework. The policy push towards participation, Bishop claims, aimed to create a different generation of workers, ‘increasingly required to assume the individualisation associated with creativity: to be entrepreneurial, embrace risk, look after their own self-interest, perform their own brands, and be willing to self-exploit’.Footnote66 Harvie calls this kind of artist an artepreneur,Footnote67 but Bishop ventures further, suggesting that creative workers are a model against which the ultimate workers of late capitalism are created, an idea that was developed in detail by Bojana Kunst. ‘The artist’, claims Kunst, ‘has become a prototype of the contemporary flexible and precarious worker because the artist’s work is connected to the production of life itself – in other words with the production of subjectivity’.Footnote68 As ‘autonomy, self-realization, creativity and the disappearance of the difference between work time and private time’ move from artistic into all other forms of work,Footnote69 artists increasingly make work about work: ‘visibility of work’ becomes a central theme and this fundamentally shifts the relationship with audiences, who are invited to become actively involved participants.Footnote70 Participation therefore reflects (on) the artist’s position, at the bottom of the contemporary labour market. This argument, that artists exemplify precarity, also works to absolve them of political responsibility. From Kunst’s standpoint, exploitation by the artist becomes difficult to prove: the artist is the ultimately exploited worker.

The Jersey projects fit into the mould of work about work; here, however, it is the labour of Rogalska’s collaborators rather than the artist that is the point of investigation. In The Royals, images of participants sculpting clay are overlaid with conversations about the working conditions in Jersey. 19-hour shifts at the conveyor belt are measured against the work conducted outside, almost inevitably in cold and windy conditions; one worker describes rain so persistent it breaks through several raincoats per day.Footnote71 At the end of the shift, it is back to inadequate living quarters: barracks that overheat in the summer or repurposed, freezing-cold hotels, broken windows, and ubiquitous mould. The imprint of this labour on the body is also given space: there are stories of severe back pain, involuntary hand movements, and daily morning rituals of waking up and lying motionless, waiting for feeling to return to limbs. There is no sick pay for the first 6 months and no holiday pay at all; the group laughs when asked if they are unionised and their wish list – which would later form the basis for Agri-Care – includes kind bosses and a £10 hourly wage. A collective cold-headed clarity about the circumstances that facilitate this mistreatment is also present: one participant mentions that a reduction in prospective applicants since the EU referendum may improve working conditions, a theory he explains in terms of supply and demand. Another one thinks it would help if those in charge took to the fields for half a day; maybe then they would stop shouting ‘szybciej!’ – Polish for ‘faster!’ - at the workers (‘it’s the only word they learned’, he adds).

Rogalska came to Jersey for a series of short residencies; The Morning Boat call-out offered a fee of up to £2,000, travel expenses, and accommodation, for a total of four weeks of work.Footnote72 Even if the residency format exemplifies the precarity discussed by Kunst, enforcing instability and short-term migration in exchange for temporary lodgings and basic pay, it is difficult to imagine how reflections on artistic labour could logically co-exist alongside stories of jobs that come with one-word orders to speed up. This inevitable absence of artistic labour in the Jersey projects also helps uncover how they differ from mainstream ideas of participation. In Sierra’s work, labour exploitation is replicated, and the politics dislocated from the everyday of contracted participants to the spaces of biennials and exhibition openings; even when it is not visible, the artist’s labour is endlessly discussed for its ethics and politics. Rogalska, by contrast, thematises worker exploitation and moves to the terrain of her collaborators, the literal and symbolic sites of politics which enable this exploitation. She also removes herself from view, appearing only as a background presence in The Royals, where she is occasionally heard asking questions; she almost completely disappears in Agri-Care, which articulates workers’ demands and so positions Rogalska’s collaborators as authors. The centring of workers and their labour, and the disinterest in artistic labour, distinguish Rogalska’s methodology and explain why it is possible to refer to the three pieces discussed here as the ‘Jersey projects’: in centring workers rather than her own work with them, the artist shares the ownership and authorship of the pieces.

The focus on artistic labour, which Rogalska sidelines, is not coincidental: it can be traced to theoretical thinking on contemporary labour upon which the theorisation of participation was built. Kunst’s ideas are anchored in Paolo Virno’s research on virtuosic labour, a form of wage labour, which is not, at the same time, productive labor’.Footnote73 Attributed to waiters, butlers, singers, and actors alike, for Virno, virtuosic labour is paradigmatic of post-Fodism: all work becomes virtuosic once ‘the virtuoso begins to punch a time card’ with the invention of what he refers to as ‘culture industry’.Footnote74 Defined by its lack of a tangible product, virtuosic labour also ‘requires the presence of others’,Footnote75 two traits it shares with political action. ‘One could say that every political action is virtuosic’, argued Virno: ‘[e]very political action, in fact, shares with virtuosity a sense of contingency, the absence of a “finished product”, the immediate and unavoidable presence of others’.Footnote76

The import of these traits into contemporary labour is what spells a depoliticization of work as ‘[p]olitics […] becomes a productive force’ and part of a workers’ ‘toolbox’.Footnote77 When artists make work about their work, therefore, they are shining a light on this process and attempting its re-politicisation. To do otherwise, Hito Steyerl argued, is to ignore the arts as a site of political struggle:

If politics is thought of as the Other, happening somewhere else, always belonging to disenfranchised communities in whose name no one can speak, we end up missing what makes art intrinsically political nowadays: its function as a place for labor, conflict, and … fun – a site of condensation of the contradictions of capital and of extremely entertaining and sometimes devastating misunderstandings between the global and the local.Footnote78

The Jersey projects reveal a fault in this logic: rather than being ubiquitous, entry into virtuosic labour is a form of privilege perpetuated on the back of marginalised groups tasked with work which, while not virtuosic, is still essential. When Rogalska’s collaborators are working in the field, they are participating in non-virtuosic agricultural labour; it is only when they join a participatory project and make clay potatoes destined to be taken outside the market via honesty boxes rather than added to it as an object of ‘value’ that they can become part of the privileged contemporary virtuosic labour force. When they centre the artist and their labour, mainstream modes of participation help hide the exploitation happening outside of virtuosity from view: rather than re-politicising, they are in fact at risk of depoliticising art practice.

The widespread precarisation, the ‘dominant neoliberal instrument of governance’, does not mean there is such a thing as a homogenous precariat, argued Isabell Lorey: rather than a ‘common identity’, the precarious have ‘common experiences’.Footnote79 Assuming a common identity flattens and erases this heterogeneity and risks denying ‘the mostly migrant “others” […] their own capacity for political action’.Footnote80 Lorey argues for a political constituting of the precarious in which the ‘fundamental aspect is not the common, and thus not the consensus, but rather the conflict’;Footnote81 the difference among the precariat fuels productive political activism. This is a theory that in current models of participation cannot be tested: they fail to consider, capture, or engender work, such as the one created by Rogalska, which directly addresses the heterogeneity of the precarious. When artists are framed as not only economically vulnerable and conceptually exploited by capitalism, but also the model of late-capitalist struggle, an alibi for political fecklessness is handed over to the artistic community. Work about artistic work flourishes; when public funding shrinks, artists’ work conditions worsen, but their artistic material expands and more work about work is created, rewarding professional survival with cultural capital and public attention while ensuring a depoliticization of art. The invisibility of an Eastern European migrant precariat within artistic production is not the result of an attention deficit but evidence of the system working.

Coda

Hundreds of bodies stand squashed, slowly nudging towards a big glass door. The date is 8 May 2020. The first wave of the pandemic is in full swing and the national borders have been (re)imposed, but Eastern European seasonal workers find themselves in socially non-distanced queues, flying across the continent to save Western European asparagus, strawberries, and potatoes from rotting.Footnote82 The list of privileges afforded to virtuosic workers now extends to COVID safety protocols. Just a few months after the photo from the start of this article was taken, in the summer of 2020, Leicester remained locked down as the rest of England opened. A COVID-outbreak in the local meat factory had expanded into the city: the precarity of the temporary migrant class had escaped its enclosure.

Notes on Contributor

Bojana Janković is an artist, researcher, and migrant. Her PhD research at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama investigates how Eastern European performance practices become a site of resistance to migrant marginalisation. Her performances, installations, and texts have appeared in the UK, Serbia, and internationally, including at Tate Modern (London), and Center for Art on Migration Politics (Copenhagen).

Notes

1. Ghirda Vadim, Virus Outbreak Romania, May 8, 2020, photo taken May 8, 2020, http://www.apimages.com/metadata/Index/Virus-Outbreak-Romania-Britain-Seasonal-Workers/a2b1175e1f6f4b38af02184dc25cc517/7/0 (accessed November 4, 2022).

2. See for example, Larry Wolff, Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000); Maria Todorova, Imagining the Balkans (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

3. Alexander Boot, ‘To Eastern Europeans, Legal Is Anything They Can Get Away With, Mail Online, February 21, 2012, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-2089527/To-Eastern-Europeans-legal-away-with.html (accessed November 4, 2022).

4. Giles Sheldrick, ‘Benefits Britain Here We Come! Fears as Migrant Flood Begins’, Express, January 1, 2014, https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/451409/Benefits-Britain-here-we-come-Fears-as-migrant-flood-begins (accessed November 4, 2022).

5. James Slack, ‘Eastern European Migrants Filling Low-Skill Jobs Forcing down British Pay’, Mail Online, May 20, 2015, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3088541/Three-four-migrants-Eastern-Europe-filling-low-skill-jobs-roles-fruit-picking-evidence-mounts-cheap-labour-forcing-British-workers-pay.html. (accessed November 4, 2022).

6. Andrew Malone, ‘Slaughter of the Swans: As the Carcasses Pile up and Crude Camps Are Built on River Banks, Residents Are Too Frightened to Visit the Park in Peterborough’, Mail Online, March 26, 2010, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1261044/Slaughter-swans-As-carcasses-pile-crude-camps-built-river-banks-residents-frightened-visit-park-Peterborough.html (accessed November 4, 2022).

7. Alexandra Bulat, ‘“High-Skilled Good, Low-Skilled Bad?” British, Polish and Romanian Attitudes Towards Low-Skilled EU Migration’, National Institute Economic Review 248, no. 1 (2019): 49–57 (50).

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid., 54.

10. The Morning Boat, ‘Agri-Care’, 2017, https://morningboat.com/portfolio/agri-care/ (accessed November 4, 2022); The Morning Boat, ‘Alien Species; Jersey Migrant Worker Archive’, 2017, https://morningboat.com/portfolio/jersey-migrant-worker-archive/ (accessed November 4, 2022).

11. Elodie Redoulès, ‘Gallery: View Life through a Migrant’s Eyes…’, Bailiwick Express Jersey, 2019, https://www.bailiwickexpress.com/jsy/news/island-life-seen-perspective-migrant-workers/ (accessed November 4, 2022).

12. Artsadmin, ‘So-Called Law: Screening & Research Sharing’, 2017, https://www.artsadmin.co.uk/events/4002 (accessed November 4, 2022).

13. MGLC, ‘Alicja Rogalska: Citizens of Nowhere, Artist Talk’, 2019, https://www.mglc-lj.si/eng/exhibitions_and_events/alicja_rogalska_citizens_of_nowhere_artist_talk/102 (accessed November 4, 2022).

14. The programme opened with a two year focus on agriculture and fisheries; no new projects have been developed since 2019.

15. The Royals is not publicly available, but the artist shared a copy of the film with me. Alien Species: Jersey Migrant Worker Archive remains on Jersey and was not available to me; I discuss its ideas later in the essay.

16. Jersey Royal Company, ‘About Us’, https://jerseyroyals.co.uk/about-us/ (accessed July 2, 2020).

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Claire Bishop, ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents’, Artform (February 2006): 178–83.

20. Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London; New York: Verso Books, 2012), 2.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid., 19.

23. Ibid., 29.

24. Ibid., 27.

25. Adam Alston, Beyond Immersive Theatre: Aesthetics, Politics and Productive Participation (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 9. Original italics.

26. Gareth White, Audience Participation in Theatre: Aesthetics of the Invitation (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 14.

27. Jersey Royal Company, ‘Jersey Royal Company Video from Produce Investments Videos on Vimeo’, https://player.vimeo.com/video/206030121 (accessed June 30, 2020).

28. Jen Harvie, Fair Play: Art, Performance and Neoliberalism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 97.

29. Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods (Dijon: Presses du réel, 2009), 51.

30. Claire Bishop, ‘Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics’, October 110 (2006): 51–79 (68).

31. Bishop, Artificial Hells, 222.

32. Ibid., 223.

33. Shannon Jackson, Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics (New York: Routledge, 2011), 68.

34. Santiago Sierra, ‘Workers Who Cannot Be Paid, Remunerated to Remain Inside Cardboard Boxes’, https://www.santiago-sierra.com/20009_1024.php (accessed December 12, 2022).

35. Santiago Sierra, ‘Polyurethane Sprayed on the Backs of Ten Workers’, https://www.santiago-sierra.com/200418_1024.php (accessed December 12, 2022).

36. Santiago Sierra, ‘10 Inch Line Shaved on the Heads of Two Junkies Who Received a Shot of Heroin as Payment’, https://www.santiago-sierra.com/200011_1024.php (accessed December 12, 2022).

37. Grant Kester quoted in Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 139.

38. Martha Fleming quoted in Ibid., 141.

39. Both Kester and Nicolas Bourriaud engaged in prolonged, public confrontations with Bishop, archived on the pages of Artforum and October. My argument here is that Bishop and Kwon represent two poles of the participation debate – even if other parts of that debate were more visible. For a summary of these debates, see David M. Bell, ‘The Politics of Participatory Art’, Political Studies Review 15, no. 1 (2017): 73–83.

40. Kwon, One Place after Another, 145.

41. Ibid., 146.

42. Ibid., 153.

43. Ibid., 154.

44. Ibid., 153.

45. The Morning Boat, ‘Introduction’, 2016, https://morningboat.com/about/ (accessed November 4, 2022).

46. Erica Consterdine and Sahizer Samuk, ‘Temporary Migration Programmes: The Cause or Antidote of Migrant Worker Exploitation in UK Agriculture’, Journal of International Migration and Integration 19, no. 4 (2018): 1005–1020 (1006).

47. Ibid., 1008.

48. Nils Klawitter, Steffen Lüdke, Hannes Schrader, and Stavros Malichudis, ‘The Systematic Exploitation of Harvest Workers in Europe’, Der Spiegel, July 22, 2020, https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/cheap-and-expendible-the-systematic-exploitation-of-harvest-workers-in-europe-a-b9237b95-f212-493d-b96f-e207b9ca82d9 (accessed November 4, 2022).

49. Consterdine and Samuk, ‘Temporary Migration Programmes’, 1010.

50. Ibid.

51. Ibid. Brexit has had a dramatic impact on the seasonal workforce. As early as 2017, the National Farmers’ Union reported facing 1500 unfilled vacancies; by the end of 2021, the lack of workers had led to massive food waste, as tonnes of produce remained unpicked. See, for example, UK Parliament, ‘Labour Shortages in the Food and Farming Sector’, https://committees.parliament.uk/work/1497/labour-shortages-in-the-food-and-farming-sector/publications/ (accessed January 6, 2022); and Joanna Partridge, ‘Farmers Warn of Threat to UK Food Security Due to Seasonal Worker Visa Cap’, Guardian, December 14, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/dec/14/farmers-warn-of-threat-to-uk-food-security-due-to-seasonal-worker-visa-cap (accessed January 6, 2022).

52. The Morning Boat, public post, Facebook, November 9, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/morningboat/photos/a.689701271212642/1052605961588836/ (accessed January 6, 2022).

53. Ibid.

54. Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 13.

55. Ibid. 65.

56. Arts Council England, Let’s Create: Strategy 2020-2030, (London: Arts Council England, 2020), 27.

57. Government of Jersey, ‘Jersey’s Relationship with the UK and EU’, http://www.gov.je:80/Government/Departments/JerseyWorld/pages/relationshipeuanduk.aspx (accessed July 8, 2020).

58. See, for example, ITV News, ‘Jersey Politicians Vote for Changes to the Island’s Migration Policy’, ITV News, March 3, 2021, https://www.itv.com/news/channel/2021-03-03/states-members-to-debate-draft-migration-policy (accessed November 4, 2022).

59. States of Government of Jersey, ‘Arts Grants and How to Apply’, http://www.gov.je:80/Leisure/ArtCreativity/pages/artsgrants.aspx (accessed December 12, 2022).

60. One Foundation, ‘About’, https://onefoundation.org.je/about/ (accessed July 7, 2020).

61. See, for example, Jackson, Social Works; Helen Anne Molesworth, M. Darsie Alexander, and Julia Bryan-Wilson, eds., Work Ethic (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003); Harvie, Fair Play.

62. Harvie, Fair Play, 40.

63. Ibid.

64. Bishop, Artificial Hells, 223. Emphasis in the original.

65. Bojana Kunst, Artist at Work, Proximity of Art and Capitalism (Alresford: Zero Books, 2015).

66. Bishop, Artificial Hells, 16.

67. Harvie, Fair Play, 62.

68. Kunst, Artist at Work, 137.

69. Ibid., 139.

70. Ibid., 143.

71. Alicja Rogalska, The Royals, 2018.

72. The Morning Boat, ‘International Call for Artists’, 2016, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://morningboat.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/THE-MORNING-BOAT-call-for-artists-1.pdf (accessed November 4, 2022).

73. Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life, trans. Isabella Bertoletti, James Cascaito, and Andrea Casson (Cambridge, Mass; London: Semiotext(e), 2003), 54.

74. Ibid., 56.

75. Ibid., 52.

76. Ibid., 52–53.

77. Ibid., 62.

78. Hito Steyerl, ‘Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy’, E-Flux, no. 21 (2010), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/21/67696/politics-of-art-contemporary-art-and-the-transition-to-post-democracy/ (accessed November 4, 2022).

79. Isabell Lorey, ‘Becoming Common: Precarization as Political Constituting’, E-Flux, no. 17 (2010), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/17/67385/becoming-common-precarization-as-political-constituting/ (accessed November 4, 2022).

80. Ibid.

81. Ibid.

82. Florence Schulz, ‘German Farms Need Nearly 300,000 Seasonal Workers’, euractiv.com, March 25, 2020, https://www.euractiv.com/section/agriculture-food/news/german-farms-need-nearly-300000-seasonal-workers/ (accessed November 4, 2022).